Abstract

One of the early events in O2 chemoreception is inhibition of O2-sensitive K+ (KO2) channels. Characterization of the molecular composition of the native KO2 channels in chemosensitive cells is important to understand the mechanism(s) that couple O2 to the KO2 channels.

The rat phaeochromocytoma PC12 clonal cell line expresses an O2-sensitive voltage-dependent K+ channel similar to that recorded in other chemosensitive cells. Here we examine the possibility that the Kv1.2 α-subunit comprises the KO2 channel in PC12 cells.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments showed that the KO2 current in PC12 cells is inhibited by charybdotoxin, a blocker of Kv1.2 channels.

PC12 cells express the Kv1.2 α-subunit of K+ channels: Western blot analysis with affinity-purified anti-Kv1.2 antibody revealed a band at ≈80 kDa. Specificity of this antibody was established in Western blot and immunohystochemical studies. Anti-Kv1.2 antibody selectively blocked Kv1.2 current expressed in the Xenopus oocyte, but had no effect on Kv2.1 current.

Anti-Kv1.2 antibody dialysed through the patch pipette completely blocked the KO2 current, while the anti-Kv2.1 and irrelevant antibodies had no effect.

The O2 sensitivity of recombinant Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 channels was studied in Xenopus oocytes. Hypoxia inhibited the Kv1.2 current only.

These findings show that the KO2 channel in PC12 cells belongs to the Kv1 subfamily of K+ channels and that the Kv1.2 α-subunit is important in conferring O2 sensitivity to this channel.

The ability to sense and respond to reduced oxygen (O2) tension (hypoxia) is essential for the survival of mammalian cells. Specialized cells in the body (O2-sensitive or chemoreceptor cells) can quickly sense and respond to O2 deprivation. These O2-sensitive cells are present in a variety of tissues including the carotid body (a small organ located near the bifurcation of the common carotid artery), the pulmonary vasculature, and pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies (small organs distributed widely throughout the airway mucosa). Stimulation of these cells results in cardiovascular and pulmonary responses that optimize the delivery of O2 to vital organs, thereby preventing global or localized O2 deficits that can produce irreversible cellular damage (Weir & Archer, 1995; Lahiri, 1997). Despite their critical homeostatic role, the mechanisms by which O2-sensitive cells detect a change in O2 tension (PO2) and transduce this signal into the appropriate biological response remain unknown.

The presence of O2-sensitive K+ (KO2) channels has been shown in different chemosensitive cells (Lopez-Barneo, 1996). Inhibition of the KO2 channel activity is an important early event in the process of O2 chemoreception, which leads eventually to cell depolarization, Ca2+ influx, neurotransmitter release, muscle contraction, regulation of protein kinases, and alterations in gene expression (Czyzyk-Krzeska et al. 1992; Bunn & Poyton, 1996; Lopez-Barneo, 1996; Beitner-Johnson & Millhorn, 1998). Therefore, KO2 channels have been proposed as key elements in the detection of changes in O2 availability by chemosensitive cells.

Although KO2 channels in chemosensitive cells have been investigated extensively using electrophysiological techniques, there is relatively little information about their molecular identity. In most O2-sensitive cells the KO2 channels are voltage dependent: slow-inactivating voltage-dependent K+ (KV) channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, rabbit carotid body type I cells and pulmonary neuroepithelial body cells and Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa) in rat type I cells (Peers, 1990; Archer et al. 1996; Osipenko et al. 1997). However, in rat carotid body type I cells a background K+ current (Kleak) is also inhibited by hypoxia (Buckler, 1997). The rat phaeochromocytoma (PC12) cell line has been used as a model system for studying O2-chemosensory mechanisms (Czyzyk-Krzeska et al. 1994; Norris & Millhorn, 1995; Bright et al. 1996; Zhu et al. 1997; Taylor & Peers, 1998). Importantly, PC12 cells express a slow-inactivating voltage-dependent KO2 channel that is inhibited by hypoxia (Zhu et al. 1996; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Hence, this cell line provides a unique and useful model for combining electrophysiological studies with molecular biological experiments designed to clarify the molecular nature of voltage-dependent KO2 channels and basic O2-sensing mechanisms (Conforti et al. 1998).

Voltage-dependent K+ (KV) channels are complex hetero-oligomeric proteins formed by four α pore-forming subunits and auxiliary β-subunits (Jan & Jan, 1997). The genes that encode the KVα-subunits have been classified into at least six subfamilies: Shaker (Kv1.1–1.7), Shab (Kv2.1–2.2), Shaw (Kv3.1–3.4), Shal (Kv4.1–4.3), Kv5.1 and Kv6.1 (Pongs, 1992). In addition, a novel family of electrically silent KVα-subunits was recently identified (Patel et al. 1997). A K+ channel composed of a silent Shab-like α-subunit (Kv9.3) cloned from rat pulmonary artery and Kv2.1 has been proposed as a possible KO2 channel in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Patel et al. 1997). Others have suggested that pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells express different KO2 channels formed by either Kv2.1 or Kv1.5 α-subunits, which display different functional roles in the cellular response to hypoxia (Archer et al. 1998). In addition, other KV channel subtypes have been implicated in the cellular response to hypoxia in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and other O2-sensitive cell types (Vega-Saenz de Miera & Rudy, 1992; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997; Wang et al. 1997; Hulme et al. 1999; Perez-Garcia et al. 1999). Thus, the identity of the O2-sensitive K+ channels remains unclear.

The present study was undertaken to elucidate the molecular identity of the KO2 channel in PC12 cells. The current findings provide evidence that the O2-sensitive K+ channel present in PC12 cells belongs to the Kv1 subfamily of KV channels and that the Kv1.2 α-subunit is an important O2-sensitive component of this channel.

METHODS

PC12 clonal cell line

PC12 cells, obtained from American Type Culture Collection, were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's-Ham's F-12 medium (DMEM-F-12) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units ml−1 penicillin, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were maintained in an incubator in which the environment (21 % O2, 5 % CO2, remainder N2; 37°C) was strictly maintained. Cells used for electrophysiological experiments were dissociated with 0.25 % trypsin plus 1 mM EDTA and plated at low density (ca 100 000 ml−1) on glass coverslips and were used 1–3 days after plating.

Expression of KV channels in Xenopus oocytes

Xenopus oocytes were injected with cRNAs obtained as run-off transcripts of Kv1.2 (HBK5 cloned in pcDNA3 plasmid vector) and Kv2.1 cDNAs (DRK1 cloned in pBluescript-SK− plasmid vector). The double-stranded DNA templates were linearized and in vitro transcribed to cRNAs with mMessage mMachine kits (for T7 or SP6 promoter; from Ambion), according to the manufacture's protocol. After the transcription reaction was complete, the template DNA was degraded and cRNA was recovered by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The size of the in vitro transcription product, its quantity, and its quality were evaluated by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. The cRNAs were stored in RNase-free water at -80°C.

Stage IV-V oocytes were isolated as follows. Frogs were anaesthetized with 0.2 % tricaine methanesulphonate (MS 222). Clumps of oocytes were removed and washed in Ca2+-free ND-96 solution containing (mM): 82.5 NaCl, 2.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, and 5.0 Hepes; pH 7.5. After removal of the oocytes, the frogs were allowed to recover and returned to their tanks. Single oocytes were dissociated with 3 mg ml−1 type II collagenase in Ca2+-free ND-96 solution at 20°C. After digestion, the follicular layer was removed mechanically with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. cRNA (50 nl; 0.2 μg μl−1) was injected into the oocyte with a Drummond 510 microdispenser via a sterile glass pipette with a tip of 20–30 μm. After injection the oocytes were maintained in a solution of the following composition (mM): 96 NaCl, 2.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 Hepes, 2.5 sodium pyruvate, and 0.5 theophylline, with 100 units ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin; pH 7.5. Injected oocytes were stored in an incubator at 19°C and were used for electrophysiological experiments after 24 h. We followed the methods previously described by Stuhmer & Parekh (1995).

Electrophysiology

Details of our patch-clamp station and the whole-cell and single-channel methods were published previously (Zhu et al. 1996; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Experiments were performed using Axopatch 200A (for whole-cell and single-channel voltage-clamp) and Axoclamp 2A (for two-electrode voltage-clamp) amplifiers (Axon Instruments). The digitized signals were stored and analysed on a personal computer using pCLAMP 5.5.1 and 6.0.3 software (Axon Instruments). Experiments were conducted at room temperature (25°C).

Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments were performed according to standard procedures (Hamill et al. 1981). The composition of the external solution was (mM): 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 2.0 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, and 10 glucose; pH 7.4. The composition of the pipette solution was (mM): 140 potassium gluconate, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 3 ATP-sodium, and 10 Hepes; pH 7.2. ATP was included in the pipette solution to exclude the contribution of ATP-sensitive K+ channels and to compensate for reduced cellular energy metabolism during hypoxia. K+ currents were recorded by depolarizing voltage steps to +50 mV (800 ms duration) from a holding potential of -70 mV. Steady-state current amplitude was measured at the end of the test pulse. Current inhibition is reported as relative changes in current amplitude from the control (normoxia) values. For whole-cell experiments using antibodies, electrodes were dipped in an antibody-free solution and then back filled with the pipette solution containing the antibody of interest. Anti-Kv1.2 antibody was used at 0.03 μg ml−1. This concentration was calculated as required for a 1:1 interaction with the number of K+ channels in a single PC12 cell (calculated by dividing the single-channel conductance into the maximal KV conductance). Higher concentrations of anti-Kv1.2 antibody (0.3 μg ml−1) induced nearly complete inhibition of the K+ current. Anti-Kv2.1 antibody was used at 1:125 dilution. This concentration was previously used to block Kv2.1 channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Archer et al. 1998). Electrodes had a resistance of 1–3 MΩ, which permits dialysis of the antibody into the cell (Vassilev et al. 1988; Naciff et al. 1996).

Whole-cell current from injected Xenopus oocytes was recorded using the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique, as previously described (Stuhmer & Parekh, 1995). The composition of the external solution was (mM): 115 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, and 10 Hepes; pH 7.2 (Stuhmer et al. 1989). The two electrodes had a resistance of 1–2 MΩ and were filled with 3 mM KCl. Whole-cell leak and capacitative currents were subtracted using currents elicited by small hyperpolarizing pulses (P/4). Currents were digitized between 0.5 and 5 kHz after being filtered between 0.2 and 1 kHz. For experiments using anti-Kv1.2 antibody, oocytes were injected with 0.01 μg anti-Kv1.2 antibody (in 50 nl) 2 h before recording. This amount of anti-Kv1.2 antibody was calculated to result in an intracellular concentration similar to that obtained in PC12 cells, assuming a cell volume 106 times higher in oocytes compared to PC12 cells.

Single-channel (cell-attached) voltage-clamp experiments were performed in Xenopus oocytes from which the vitelline membrane had been manually removed after shrinkage in a hyperosmotic medium (mM): 200 potassium aspartate, 20 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 10 Hepes; pH 7.3. Microelectrodes with resistances of 3–5 MΩ were prepared, fire-polished, and coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning). The external solution composition was (mM): 140 KCl, 2.0 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, and 5 EGTA; pH 7.3. The pipette solution composition was (mM): 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 5 Hepes, and 1 EGTA; pH 7.3. Ensemble-averaged currents and open channel probability (NPo) were calculated using pCLAMP 6.0.3 software, as previously described (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Single-channel conductance was measured with ramp pulse depolarization from -60 mV (holding potential) to +50 mV (0.14 mV ms−1), as previously described (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997).

Exposure of cells to hypoxia

During electrophysiological experiments the effect of hypoxia was studied by switching from a perfusion medium bubbled with air (21 % O2) to a medium equilibrated with 10 % O2 (balanced N2) or 100 % N2 with 5 mM sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4; an O2 chelator). The corresponding mean O2 partial pressures (PO2) in the chamber, measured with an O2-sensitive electrode, were 150 mmHg (21 % O2), 80 mmHg (10 % O2) and 0 mmHg (N2+ Na2S2O4) (Zhu et al. 1996).

Western blotting

PC12 cell total lysate was prepared according to standard procedures. PC12 cells were harvested by resuspending them in lysis buffer containing (mM): 50 Hepes, 10 EDTA, 100 NaCl, and 1 PMSF with 1 % Triton X-100, 2 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin. After sonication and centrifugation, the protein content was measured using the Bio-Rad method. Aliquots of cell proteins (40 μg) were fractionated on 6 % SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Non-specific protein-binding sites were blocked by incubation in PBST (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1 % Tween-20) with 3 % non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were incubated with the first antibodies (1:200 dilution) overnight, at 4°C. After washing 3–4 times, the strips were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies at 1:2000 (DAKO, Denmark). Bands were visualized using Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Life Science Inc.) exposed to X-ray film. Prestained molecular mass standards were used to assess the apparent molecular mass.

Immunohistochemistry

PC12 cells were grown on slides for 3 days and fixed with 2 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized and blocked with PBS containing 0.2 % Triton X-100 and 10 % normal goat serum (NGS). Slides were incubated with anti-Kv1.2 antibody (2 μg ml−1 in 1 % NGS in PBS) overnight at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized with a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ICN/Cappel). The fluorescence background was assessed by applying the same protocol to cells that were incubated overnight in 1 % NGS in PBS.

Source and specificity of anti-Kv1.2 and anti-Kv2.1 antibodies

Affinity purified anti-Kv1.2 antibody (Alomone Labs) was prepared against the C-terminal part of the rat Kv1.2 protein, specifically amino acids 417–498 (Stuhmer et al. 1989). This sequence is specific for Kv1.2 except for 11 amino acids, which are similar to those of Kv1.1. The company specification indicates that there is no cross-reactivity with Kv1.1. Cross-reactivity with another member of the Kv1 subfamily, Kv1.3, was tested in Western blot experiments with Kv1.3 antigen, a glutathion-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein with the C-terminal 471–523 amino acids of the Kv1.3 protein. Anti-Kv1.3 antibody and its corresponding antigen were obtained from Alomone Labs. Specificity of anti-Kv1.2 antibody was also established in an immunohistochemical study using Kv1.2 antibody pre-incubated with a ten-fold molar excess of the antigen at room temperature for 1 h. The antigen for Kv1.2, a GST fusion protein containing the epitope against which the antibody was raised, was also obtained by Alomone Labs. The specific ability of anti-Kv1.2 antibody to block Kv1.2 current was established in Xenopus oocytes.

Polyclonal antibody against Kv2.1 was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology Incorporated. It is prepared against the C-terminal part of rat Kv2.1, amino acids 837–853 (Sharma et al. 1993).

Data analysis

All data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test (paired or unpaired); P < 0.05 was defined as significant.

Chemicals

Sodium dithionite and charybdotoxin were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co.

RESULTS

The KO2 channel in PC12 cells belongs to the Kv1 subfamily of KV channels

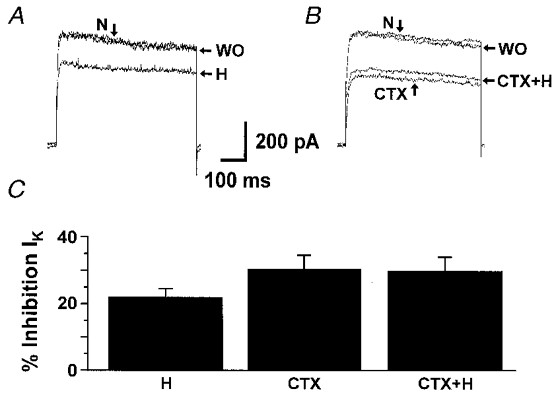

PC12 cells express a slow-inactivating KV current (IK) that is inhibited by hypoxia (Fig. 1A). Potassium currents recorded in a normoxic environment (N; 21 % O2) were inhibited by 22 ± 3 % (n = 6) by hypoxia (H = 10 % O2), as previously shown (Zhu et al. 1996). Charydbotoxin (CTX), a potent blocker of Kv1.2 and Kv1.3, was used to ascertain the molecular nature of the KO2 channel in PC12 cells (Grissmer et al. 1994; Russell et al. 1994). The effect of CTX on the K+ current and the hypoxic inhibition of the K+ current in the presence of CTX were studied in whole-cell configuration (Fig. 1B). Potassium currents recorded in a normoxic environment (N) were inhibited by 31 ± 6 % (n = 7) by CTX (20 nM). This amount of K+ current inhibition by CTX is not statistically different from that induced by hypoxia only. Subsequent exposure of these cells to hypoxia in the presence of CTX (CTX+H) did not induce further inhibition (n = 7). These responses were reversible upon returning to toxin-free normoxic conditions. These data show that CTX is able to inhibit O2-sensitive K+ channels, implying that the O2-sensitive K+ current in PC12 cells is carried by Shaker-type KV channels.

Figure 1. Sensitivity to charybdotoxin (CTX) of the KO2 current recorded in PC12 cells.

K+ currents (IK) were elicited by depolarizing voltage steps to +50 mV from a holding potential of -70 mV (every 5 s) in the whole-cell configuration. A, effect of hypoxia (H; 10 % O2) in absence of CTX. Control currents were recorded in normoxia (N; 21 % O2). WO indicates currents recorded after returning to normoxia. B, effect of hypoxia in the presence of CTX (20 nM). After steady-state inhibition of the K+ current by CTX was reached, cells were exposed to H in the presence of CTX. WO indicates currents recorded after returning to normoxia without CTX. C, mean K+ current inhibition by hypoxia alone (H, n = 6), CTX alone (n = 7) and hypoxia in the presence of CTX (CTX+H, n = 7).

Importance of the Kv1.2 α-subunit in the response to hypoxia in PC12 cells

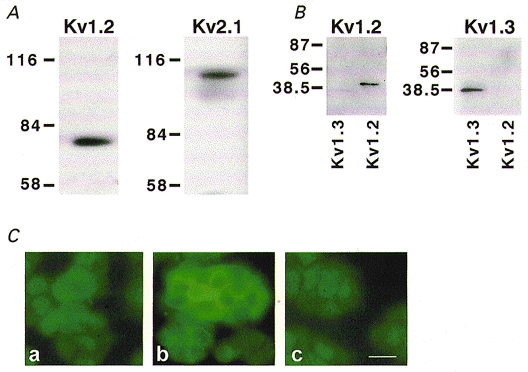

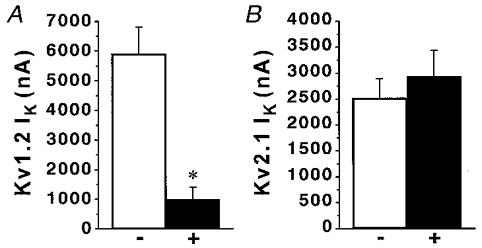

We showed previously that exposure of PC12 cells to prolonged hypoxia increased the expression of the Kv1.2 gene, which in turn correlated with an enhanced O2 sensitivity of the KV current (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). PC12 cells also express the Kv2.1 α-subunit which according to previous data is not O2 sensitive in these cells (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Expression of Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 α-proteins was determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis with an affinity-purified antibody against Kv1.2 revealed a single band of ∼80 kDa. Antibodies against Kv2.1 detected a single band of ∼110 kDa. A similar band has been previously identified as the Kv2.1 α-subunit in PC12 cells (Sharma et al. 1993). The specificity of anti-Kv2.1 antibody has been previously demonstrated (Archer et al. 1998). The specificity of Kv1.2 antibody was established by immunoblot and immunohistochemical analyses. Anti-Kv1.2 antibody recognizes a single band of the predicted molecular mass in PC12 cell total lysate (Fig. 2A). This antibody did not cross-react with Kv1.3, another member of the Kv1 subfamily of KV channels (Fig. 2B). Anti-Kv1.2 antibody recognized the Kv1.2 fusion protein, and did not cross-react with Kv1.3 antigen. The Kv1.3 antigen was recognized only by the anti-Kv1.3 antibody. The specificity of anti-Kv1.2 antibody was confirmed in immunohistochemical experiments. The intense, uniform labelling of the PC12 cell with anti-Kv1.2 antibody is shown in Fig. 2Cb. Background fluorescence in the absence of Kv1.2 antibody is shown in panel a. Comparable background fluorescence was observed when the anti-Kv1.2 antibody was pre-incubated with an excess of the matching Kv1.2 fusion protein (panel c), indicating the specificity of the antibody for Kv1.2. The ability of anti-Kv1.2 antibody to selectively block Kv1.2 channels was assessed in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 3). Recombinant Kv1.2 current amplitude was significantly decreased in oocytes injected with anti-Kv1.2 antibody. A significant Kv1.2 current inhibition ranging from 44 to 82 % was observed at different voltages (-10, 0, 20 and 50 mV) in a total of 13 oocytes. The same concentration of anti-Kv1.2 antibody did not reduce K+ current amplitude measured at 0 and 20 mV in oocytes expressing Kv2.1 channels (n = 14). Figure 3 compares the effect of anti-Kv1.2 antibody on the K+ current measured in oocytes expressing Kv1.2 channels with oocytes from the same batch expressing Kv2.1 channels.

Figure 2. Expression of the Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 α-subunits of K+ channels in PC12 cells and specificity of anti-Kv1.2 antibody.

A, Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 polypeptide expression in PC12 cell total lysate. Immunoblots of rat PC12 cell protein (40 μg) were incubated with affinity-purified anti-Kv1.2 or anti-Kv2.1 antibodies. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left in kilodaltons (kDa). B, immunoblots of GST-fusion proteins (50 ng) for Kv1.3 and Kv1.2 (indicated at the bottom of the blot) were incubated with anti-Kv1.2 antibody (left panel) or anti-Kv1.3 antibody (right panel). C, immunostaining of PC12 cells with anti-Kv1.2 antibody. Panel a, background staining of PC12 cells that were subjected to all steps in the staining protocol, except that the primary antibody was omitted. Panel b, labelling of PC12 cell membranes with anti-Kv1.2 antibody. Panel c, immunostaining of PC12 cell with anti-Kv1.2 antibody pre-incubated with the antigen against which the antibody is directed. The intensity of the fluorescent signal is comparable to the background fluorescence observed in panel a. Scale bar = 20 μm and applies to all panels in C.

Figure 3. Effect of anti-Kv1.2 antibody on recombinant Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 channels.

A, anti-Kv1.2 antibody blocks K+ current (IK) in oocytes expressing Kv1.2 channels. Kv1.2 currents were recorded in control oocytes (-, n = 6) and oocytes injected with anti-Kv1.2 antibody (0.01 μg in 50 nl) 2 h before recording (+, n = 4). * < 0.01 using Student's unpaired t test. B, lack of effect of anti-Kv1.2 antibody on K+ currents in oocytes expressing Kv2.1 channels. Kv2.1 currents were recorded in control oocytes (-, n = 5) and anti-Kv1.2-injected oocytes (+, n = 6). Ik were elicited with voltage steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to between -10 and 0 mV in two-electrode voltage-clamp experiments.

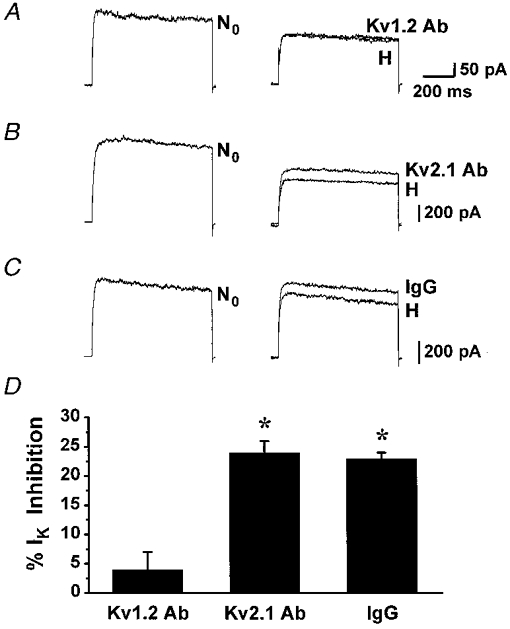

We next tested the hypothesis that the KO2 channel in PC12 cells is composed of Kv1.2 α-subunit(s) by comparing the efficiency of anti-Kv1.2 and anti-Kv2.1 antibodies in blocking the KO2 current. Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments were performed with anti-Kv1.2 or anti-Kv2.1 antibodies delivered to the cell by dialysis through the patch pipette. Figure 4 shows representative experiments performed in the presence (A) of anti-Kv1.2 antibody in the pipette. The left panel shows K+ currents recorded in normoxia upon breaking into the whole-cell configuration (N0). Within 8–10 min after breaking into the whole-cell configuration, dialysis of anti-Kv1.2 antibody (Kv1.2 Ab) through the patch pipette resulted in a 32 ± 6 % (n = 6) decrease in K+ current amplitude. Subsequent exposure to hypoxia (H, 10 % O2) did not inhibit the K+ current. The averaged inhibition of the K+ current by hypoxia in cells dialysed with antibody against Kv1.2 was 4 ± 3 % (n = 6; Fig. 4C). Identical experiments were performed with anti-Kv2.1 antibody in the patch pipette (Fig. 4B). Within 8–10 min after breaking into whole-cell configuration dialysis of anti-Kv2.1 antibody (Kv2.1 Ab) through the patch pipette resulted in a 39 ± 3 % (n = 3) decrease in K+ current amplitude. Subsequent exposure to hypoxia (H, 10 % O2) inhibited the K+ current by 24 ± 2 % (n = 3). This amount of inhibition is significantly different from that observed in cells dialysed with anti-Kv1.2 antibody (P < 0.01). Control experiments using an irrelevant antibody (rabbit anti-sheep IgG) in the pipette are shown in Fig. 4C. Ten minutes after breaking into the whole-cell configuration, no decrease in K+ current amplitude was observed, but application of hypoxia caused a reversible inhibition of the K+ current (26 ± 1 %, n = 3). This level of K+ current inhibition is not statistically different from the hypoxic inhibition in the presence of anti-Kv2.1 antibody and is also comparable to that induced by hypoxia in the absence of irrelevant antibody in the patch pipette (Fig. 1A; Zhu et al. 1996). These data suggest that the Kv1.2 α-subunit, but not Kv2.1, is critical in the response of PC12 cells to hypoxia.

Figure 4. Effect of hypoxia on the K+ current after selective block of the Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 channels by their corresponding specific antibodies.

K+ currents (IK) were elicited with voltage steps from a holding potential of -70 mV to +50 mV (every 5 s) in experiments performed in presence of anti-Kv1.2 antibody (A), anti-Kv2.1 antibody (B) or irrelevant antibody (C) in the pipette. The representative K+ current traces were recorded in normoxia (21 % O2) upon breaking into the whole-cell configuration (left panel, N0), in normoxia 8–10 min into the whole-cell configuration (right panel, labelled with the name of the antibody used in each experiment), and after exposure to hypoxia (10 % O2, H). D, mean current inhibition by hypoxia in the presence of each antibody. *P≤0.001.

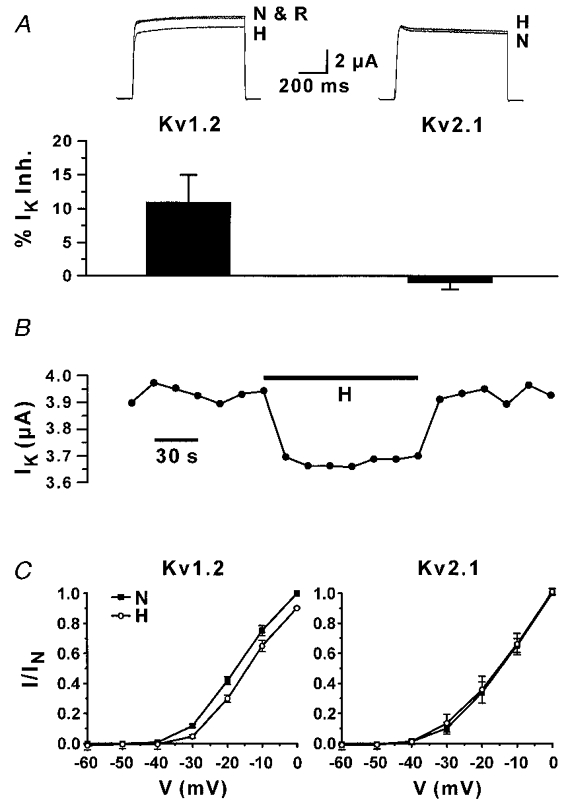

O2 sensitivity of Kv1.2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Because of the complex heteromeric structure of native K+ channels, we studied the Kv1.2 channel responses to changes in PO2 in the Xenopus oocytes. This expression system provides a means of expressing KV channels of known composition. The sensitivity of Kv1.2 channels to hypoxia was compared to that of Kv2.1 channels, which are also expressed in PC12 cells (Sharma et al. 1993; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Run-off transcripts of cRNA were prepared and microinjected into Xenopus oocytes. Control oocytes were injected with the same volume (50 nl) of water. Electrophysiological experiments were performed 1–2 days after injection. Application of depolarizing voltage steps elicited outward K+ currents only in oocytes injected with K+ channel cRNAs (data not shown). The effect of hypoxia on the expressed KV channels was studied by exposing the injected oocytes to an anoxic recording medium (100 % N2 and 5 mM sodium dithionite, N2S2O4, an O2 chelator; Fig. 5). Anoxia inhibited the K+ current carried by Kv1.2 channels by 11 ± 4 % (n = 8), and had no effect or slightly increased the K+ current carried by Kv2.1 channels (n = 8). The hypoxic inhibition of Kv1.2 current was reversed upon returning to normoxia (Fig. 5A and B). The time course of the hypoxic response of Kv1.2 channels is shown in Fig. 5B (representative of 4 separate experiments). Inhibition of the K+ current occurs at the onset of the anoxic medium and K+ current returns to control values upon re-introduction of the normoxic medium. The effect of anoxia on the current- voltage relationships for K+ current in Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 cRNA-injected oocytes is shown in Fig. 5C. The current- voltage (I–V) relationships were measured in normoxia (N), after 2 min exposure to anoxia (H) and 2 min after returning to the normoxic medium (R). For the sake of clarity, the I–V relationship after returning to normoxia is not shown in the figure. Anoxia induced inhibition of K+ current at each potential only in oocytes injected with Kv1.2 (n = 5). No response, or a slight irreversible increase in K+ current was observed in Kv2.1-injected oocytes (n = 3).

Figure 5. Oxygen sensitivity of Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 currents in Xenopus oocytes.

A, hypoxic inhibition of K+ currents (IK) in oocytes injected with Kv1.2 or Kv2.1 cRNAs. K+ currents were recorded in control conditions (N; 21 % O2), after 2 min exposure to anoxia (H), and after returning to normoxia (R) with the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. Currents were elicited with depolarizing voltage steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to 0 mV. The averaged data (n = 8) are shown in the bottom panel. B, time course of the effect of anoxia on the K+ current amplitude in Kv1.2-injected oocytes. Depolarizing voltage steps were applied every 15 s (same protocol as in A). Bar (H) corresponds to the time of perfusion with the anoxic medium. C, current-voltage relationship of Kv1.2 (left) and Kv2.1 (right) cRNA-injected oocytes. K+ currents were induced by depolarizing voltage steps from -60 to 0 mV (10 mV increments; holding potential 80 mV). Currents were measured in normoxia (21 % O2) and 2 min after exposure to anoxia (H). IN corresponds to the maximum IK measured in normoxia. Values are reported as mean ±s.e.m. (n = 5 for Kv1.2, n = 3 for Kv2.1).

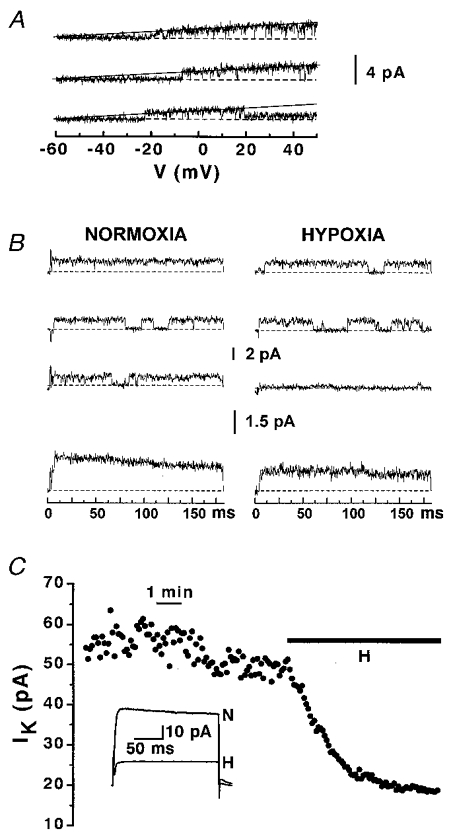

The single-channel properties of Kv1.2 channels and their response to hypoxia (10 % O2) were studied in the cell-attached configuration (Fig. 6). The single-channel I–V relationship for the Kv1.2 channels is shown in Fig. 6A. These channels have slope conductance of 18 pS (2.8 mM external K+ concentration), which is comparable to the conductance of the KO2 channel measured in PC12 cells (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Application of depolarizing voltage steps to +50 mV induced a slow-inactivating K+ current that was inhibited by hypoxia (n = 4). The effect of hypoxia on the activity of a slow-inactivating single channel of 2 pA unitary current is shown in Fig. 6B. In this experiment, exposure to hypoxia (10 % O2) induced a 33 % inhibition of the ensemble-averaged current amplitude and a 16 % reduction in NPo (unitary current amplitude was unchanged). When multiple Kv1.2 channels were present in a patch it was possible to record an outward K+ current that resembled a macroscopic K+ current (n = 3). The time course of the effect of hypoxia (10 % O2) on the Kv1.2 current amplitude in cell-attached patches is shown in Fig. 6C. Perfusion with hypoxic medium resulted in the immediate inhibition of the K+ current. The inhibition reached steady-state values after ca 2 min of exposure to hypoxia. Currents recorded in normoxia (N) and in hypoxia (H) after steady-state inhibition was reached are reported as an inset. The mean K+ current inhibition by hypoxia in cell-attached experiments was 65 ± 10 % (n = 7).

Figure 6. Response to hypoxia of Kv1.2 channels in Xenopus oocytes.

A, conductance of the Kv1.2 channels. The I–V curves were obtained with ramp pulse depolarization from a holding potential of -60 mV to +50 mV, 800 ms duration. Experiments were performed in high K+ bath solution and 2.8 mM K+ pipette solution. Dashed lines represent the zero current. The recordings were fitted with a straight line, which had a slope value of 18 pS. B, the top panels show representative traces recorded during step depolarizing pulses (from a holding potential of -60 mV to +50 mV) in normoxia and 2 min after exposure to hypoxia (10 % O2). Leak and capacitative currents were subtracted from the record. The upward current deflections from the zero line (dashed) correspond to the opening of the channel. The corresponding ensemble-averaged currents (from 100 consecutive traces) are shown in the bottom panels. C, time course of the hypoxic inhibition of K+ current recorded in a cell-attached patch containing multiple Kv1.2 channels. Bar indicates the time of perfusion with the hypoxic medium (10 % O2). K+ currents were induced by depolarizing voltage steps from a holding potential of -60 mV to +50 mV. The averaged currents from 100 consecutive traces recorded in normoxia (N) and after steady-state IK inhibition by hypoxia (H) are shown as an inset.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms by which O2-sensitive cells detect a change in O2 tension (PO2) and transduce this signal into the appropriate functional response remain unknown. However, it has become evident that O2-sensitive K+ (KO2) channels are key elements in the detection of changes in O2 availability by excitable O2-sensitive cells (Lopez-Barneo, 1996). Currently, neither the molecular composition of these important channels nor the mechanism(s) by which they respond to changes in PO2 are known. The observation that the hypoxic inhibition of KO2 channel activity occurs in excised patches from carotid body type I cells, PC12 cells and central neurons suggests it might occur via membrane-associated events (Ganfornina & Lopez-Barneo, 1992; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997; Haddad & Jiang, 1997). Various membrane-bound molecules have been proposed as the O2 sensor, including NADPH-oxidase, metal-binding proteins and the auxiliary β-subunit of KV channels (Acker, 1994; Haddad & Jiang, 1997; Gulbis et al. 1999). It has also been proposed that O2 could interact directly with the KO2 channel itself by modifying the redox state of amino acid residues in the pore-forming α-subunits and inducing a change in the channel molecular conformation (Ruppersberg et al. 1991; Lopez-Barneo, 1996). Thus, elucidation of the molecular nature of KO2 channels in different O2-sensitive cells is an important step towards understanding their role in O2 sensing. The current research provides evidence that the KO2 channel in the O2-sensitive PC12 clonal cell line is a KV channel composed of Kv1.2 α-subunit(s). To our knowledge, this is the first direct evidence of the O2 sensitivity of native Kv1.2 α-subunits of K+ channels.

We previously reported that the KO2 current in PC12 cells has slow-inactivating kinetics, is insensitive to Ca2+ and holding voltage, and is blocked by 5 mM externally applied TEA (Zhu et al. 1996). High doses of extracellular TEA are required for blockade of Kv1.2, 1.3 and 1.5 channels (Mathie et al. 1998). The current data confirm that the KO2 channel in PC12 cells belongs to the Kv1 subfamily of K+ channels. The KO2 current in PC12 cells is inhibited by charybdotoxin, a potent blocker of Kv1.2 and Kv1.3 and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channels. Although KCa channels are present in PC12 cells, we have shown previously that, under our experimental conditions, their contribution to the total outward current is negligible (Zhu et al. 1996). We have also shown that the KCa channels in PC12 cells are not inhibited by hypoxia (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997).

Additional evidence supports the conclusion that the KO2 channel in PC12 cells is formed by Kv1.2 α-subunit(s). We showed previously that the gene encoding the Kv1.2 α-subunit is selectively stimulated during prolonged exposure to hypoxia, and that the increased expression of the Kv1.2 α-subunit gene correlated with an enhanced response to hypoxia (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). On the other hand, the Kv2.1 α-subunit is also expressed in PC12 cells but its expression does not increase during prolonged hypoxia (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Here we showed that Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 α-proteins are expressed in PC12 cells. Western blot analysis with the antibody against Kv1.2 revealed a single band of ∼80 kDa. A band of similar size has been identified as a Kv1.2 α-subunit in Kv1.2 stably transfected cells and in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Barry et al. 1995; Archer et al. 1998). The specificity of the anti-Kv1.2 antibody was established by us in immunohistochemical and Western blot experiments. We have also established the feasibility of using the anti-Kv1.2 antibody to selectively block the K+ current carried by Kv1.2 channels. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that this antibody can be used as a selective blocker of its own channels. Therefore, we next tested the hypothesis that the KO2 channel in PC12 cells is composed of Kv1.2 α-subunit(s) by using antibodies against Kv1.2 as blockers of this channel and by comparing these results with similar experiments performed in the presence of anti-Kv2.1 antibody. We used the anti-Kv1.2 antibody (the same antibody that was used for Western blotting) that binds to the O2-sensitive α-subunit to block KO2 channel activity in PC12 cells. A similar approach has been used to establish the role of Kv2.1 in setting the resting potential of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Archer et al. 1998). In addition, the same approach was successfully used to modify ion channel activity in neuronal and skeletal muscle cells (Vassilev et al. 1988; Naciff et al. 1996). An irrelevant antibody, which was shown previously to have no effect on K+ and Ca2+ currents, was used as a negative control (Naciff et al. 1996). Dialysis of Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 antibodies through the patch pipette resulted in a decrease in K+ current, which occurred gradually and reached a maximum in 8–10 min. A similar time course was reported for the effect on K+ current of anti-annexin VI antibody delivered through the patch pipette (Naciff et al. 1996). Dialysis of PC12 cells with specific antibodies against the Kv1.2 α-subunit prevented the hypoxia-induced inhibition of voltage-activated K+ current. Cells that were dialysed with anti-Kv2.1 antibody maintained their response to hypoxia. This important finding suggests that a functional Kv1.2 α-subunit is necessary for the response of the KO2 channel to hypoxia and that the Kv2.1 channels are not O2 sensitive.

The O2 sensitivity of Kv1.2 was also confirmed in Xenopus oocytes. The O2 sensitivity of Kv1.2 was compared to that of Kv2.1, which has been proposed as a possible O2-sensitive K+ channel in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Patel et al. 1997; Archer et al. 1998). The Kv2.1 channel is also expressed in PC12 cells, although the current and previous data indicate that it does not mediate the O2-sensitive current in these cells (Sharma et al. 1993; Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). In Xenopus oocytes anoxia inhibited the K+ current carried by Kv1.2, and had no effect or even slightly increased the K+ current carried by Kv2.1. The hypoxic inhibition of Kv1.2 current was reversed upon returning to normoxia. Although a relatively small inhibition is induced by anoxia in intact oocytes injected with Kv1.2, the time course of the response highly correlates with the arrival of the anoxic medium to the perfusion chamber and the return of normoxic conditions. Moreover, the anoxic inhibition of the K+ current occurs over a whole range of potentials. The anoxia needed to inhibit the K+ current in intact oocytes was obtained with the use of the O2 chelator sodium dithionite, which is known to induce the formation of oxygen radicals (Archer et al. 1995). However, the inhibition of K+ current is most probably not due to the formation of oxygen radicals, since Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes have been shown to be insensitive to reactive oxygen species (Duprat et al. 1995). Furthermore, the activity of Kv1.2 channels in cell-attached experiments is inhibited by exposure to hypoxia obtained by saturating the perfusion medium with 10 % O2, without any sodium dithionite present. Single-channel experiments in oocytes injected with Kv1.2 cRNA showed that exposure to hypoxia (10 % O2; ∼80 mmHg PO2) induced an inhibition of Kv1.2 ensemble-averaged current, which was associated with a reduction in NPo and no change in unitary current amplitude. Detailed single-channel analysis was not possible because many patches contained a small conductance endogenous channel. The presence of endogenous delayed-rectifier K+ channels in Xenopus oocytes has been reported (Lu et al. 1990). The single-channel experiments were performed using the same K+ gradient used previously to study the KO2 channel in PC12 cells (Conforti & Millhorn, 1997). Thus, the Kv1.2 channel expressed in the oocyte had the same single-channel properties (conductance and inactivation kinetics) and displayed the same type of response to hypoxia as the KO2 channel in PC12 cells. The lower sensitivity of recombinant Kv1.2 current in Xenopus oocytes observed in the two-electrode voltage-clamp experiments might be due to the presence of the vitelline membrane, which is likely to constitute a barrier to O2 diffusion. It was previously reported that the follicular tissues surrounding the Xenopus oocytes (including the vitelline membrane) reduce the access of various compounds to the oocyte plasma membrane (Stuhmer & Parekh, 1995; Madeja et al. 1997). Moreover, Madeja et al. have shown that the vitelline membrane alone can be responsible for a substantial portion of this barrier effect. The current experiments using cell-attached patches of oocytes free of the vitelline membrane showed that hypoxia is able to induce a higher IK inhibition than in intact oocytes. Although this might support the fact that the vitelline membrane itself might interfere with the O2 sensitivity of the plasma membrane, the longer time course to reach steady-state inhibition induced by hypoxia in vitelline-free oocytes compared to intact oocytes and the irreversibility of the hypoxic effect suggests that other events might be activated during hypoxia in the absence of vitelline membrane, and that they eventually further inhibit the K+ current. If this were the case, an alternative explanation of the lower O2 sensitivity observed in oocytes compared to PC12 cells might reside in the different levels of expression of endogenous auxiliary subunits important in O2 sensing. We have recent evidence that PC12 cells express Kvβ2 and Kvβ3 subunits (data not shown). It was recently suggested that Kvβ2 (which is known to associate to Kv1.2 channels) might have an important role in O2 sensing (Gulbis et al. 1999). To our knowledge, the expression of these subunits in Xenopus oocytes has not been reported.

The experiments in Xenopus oocytes confirmed that the Kv1.2 channel is O2 sensitive. In contrast, Kv2.1 channels expressed in oocytes were not inhibited by hypoxia. Our results in Xenopus oocytes contrast with those obtained using different expression systems. In monkey kidney COS cells Kv2.1 and Kv2.1-Kv9.3 currents were inhibited by hypoxia, while the Kv1.2 current was not O2 sensitive (Patel et al. 1997). Recently, it has been shown that both Kv1.2 and Kv2.1 channels expressed in mouse L cells are inhibited by hypoxia (Hulme et al. 1999). The discrepancy between these expression systems might arise from the fact that they express different ‘O2 sensors’ or different signalling pathways. Although the nature of the O2 sensor remains obscure, it appears that the Xenopus oocytes behave in a manner similar to the O2-sensitive PC12 cells. In both these cell types (PC12 cells and oocytes) only Kv1.2 channels are O2 sensitive while Kv2.1 channels are not.

Relatively little is known about the subunits forming the O2-sensitive K+ channels in other chemosensitive cells. Most of the information available is derived from pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. These cells express voltage-dependent CTX-insensitive outwardly rectifying K+ channels inhibited by hypoxia (Patel et al. 1997; Archer et al. 1998). The Kv2.1 and Kv2.1-Kv9.3 subunits, present in pulmonary artery, have been proposed to form the KO2 channel in this tissue (Patel et al. 1997; Archer et al. 1998). These subunits expressed in COS cells give rise to 8 and 14.5 pS K+ channels (physiological K+), respectively, which are inhibited by hypoxia (Patel et al. 1997). The conductances of the Kv2.1 and Kv2.1-Kv9.3 channels contrast with the conductance of the KO2 channel in PC12 cells (20 pS). Archer et al. (1998) have proposed that pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells express two O2-sensitive K+ channels: Kv2.1, which might be important for initiating the hypoxia-induced depolarization, and Kv1.5, which might be important in the hypoxia-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+. Although the presence of these subunits in pulmonary artery and their role in cell excitability have been well established, there is no direct evidence (e.g. loss of O2 sensitivity upon selective blockade of these channels) that implicates them as O2-sensitive K+ channels. The different pharmacological profile of the KO2 channel recorded in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (insensitive to CTX) compared to that of the KO2 channels in PC12 cells does not exclude the possibility that the KO2 channel in pulmonary artery might also include one or more Kv1.2 α-subunits (Patel et al. 1997; Archer et al. 1998). For example, the Kv1.5-KO2 channel might be a heteromultimer formed by Kv1.5 and Kv1.2 α-subunits. In fact, it has been shown that a single CTX-insensitive Kv1.5 α-subunit can render the Kv1.2-Kv1.5 heteromeric channel insensitive to CTX (Russell et al. 1994). Recently, it has been shown that expression of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 α-subunits in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells is downregulated by chronic hypoxia (Wang et al. 1997). The downregulation of expression of these subunits correlates with the decreased O2 sensitivity of pulmonary artery in rats exposed to chronic hypoxia. The hypothesis that the Kv1.5-KO2 channel in pulmonary artery is indeed a heteromultimeric channel formed by Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 α-subunits, and that the Kv1.2 α-subunit is responsible for its O2 sensitivity is supported by recent findings showing that co-expression of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 α-subunits in mouse L cells give rise to O2-sensitive Kv1.2-Kv1.5 heteromeric channels, while homomeric Kv1.5 channels are not O2 sensitive (Hulme et al. 1999).

In the current study, we have presented direct evidence which indicates that the Kv1.2 α-subunit is an important component of native O2-sensitive K+ channels expressed in chemosensitive cells. The same α-subunit might also be an important component of native KO2 channels in other chemosensitive cells. Although the Kv1.2 α-subunit is expressed in many different tissues, it might play a special role in chemosensitive cells via a coupling with the O2 sensor. Alternatively, the Kv1.2 α-subunit might be coupled to an O2-sensitive signalling pathway activated only in chemosensitive cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr O. Pongs, Institut fur Neurale Signalverarbeitung, Hamburg, Germany for donating Kv1.2 cDNA and Dr R. H. Joho, Department of Neuroscience, University of Texas for donating Kv2.1 cDNA. We also thank Dr M. B. Genter for valuable suggestions about the immunostaining and Western blot experiments and Dr A. Shwartz for giving us access to the Xenopus oocyte facility in his laboratory. This work was supported by NIH grants HL33831 and HL59945 to D. E. Millhorn.

References

- Acker H. Cellular oxygen sensors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1994;718:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb55698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Hampl V, Nelson DP, Sidney E, Peterson DA, Weir EK. Dithionite increases radical formation and decreases vasoconstriction in the lung – Evidence that dithionate does not mimic alveolar hypoxia. Circulation Research. 1995;77:174–181. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Huang JMC, Reeve HL, Hampl V, Tolarova S, Michelakis E, Weir EK. Differential distribution of electrophysiologically distinct myocytes in conduit and resistance arteries determines their response to nitric oxide and hypoxia. Circulation Research. 1996;78:431–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Souil E, Dinh-Xuan AT, Schremmer B, Mercier J-C, El Yaagoubi A, Nguyen-Huu L, Reeve HL, Hampl V. Molecular identification of the role of voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv1.5 and 2.1 in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and control of resting membrane potential in rat pulmonary artery myocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:2319–2330. doi: 10.1172/JCI333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Trimmer JS, Merlie JP, Nerbonne JM. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits in adult rat heart – Relation to functional K+ channels? Circulation Research. 1995;77:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia induces phosphorylation of the cyclic AMP response element-binding protein by a novel signaling mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:19834–19839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright GR, Agani FH, Haque U, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Heterogeneity in cytosolic calcium responses to hypoxia in carotid body cells. Brain Research. 1996;706:297–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ. A novel oxygen-sensitive potassium current in rat carotid body type I cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:649–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn HF, Poyton RO. Oxygen-sensing and molecular adaptation to hypoxia. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:839–855. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Millhorn DE. Selective inhibition of a slow-inactivating voltage-dependent K+ channel in rat PC12 cells by hypoxia. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:293–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.293bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Zhu HW, Kobayashi S, Millhorn DE. Mechanisms of oxygen chemosensitivity in a model cell line system. In: Lopez-Barneo J, Weir EK, editors. Oxygen Regulation of Ion Channels and Gene Expression. New York: Futura Publishing Co; 1998. pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Bayliss DA, Lawson EE, Millhorn DE. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in carotid body by hypoxia. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;58:1538–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Furnari BA, Lawson EE, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia increases rate of transcription and stability of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:760–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat F, Guillemare E, Romey G, Fink M, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Susceptibility of cloned K+ channels to reactive oxygen species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:11796–11800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina MD, Lopez-Barneo J. Potassium channel types in arterial chemoreceptor cells and their selective modulation by oxygen. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;100:401–426. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DA, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, type Kv1.1, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;45:1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbis JM, Mann S, MacKinnon R. Structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel beta subunit. Cell. 1999;97:943–945. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad GG, Jing C. O2-sensing mechanisms in excitable cells: role of plasma membrane K+ channels. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recordings from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Coppock EA, Felipe A, Martens JR, Tamkun MM. Oxygen sensitivity of cloned voltage-gated K+ channels expressed in the pulmonary vasculature. Circulation Research. 1999;85:489–497. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN. Cloned potassium channels from eukaryotes and prokariotes. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1997;20:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S. Physiological responses: peripheral chemoreceptors and chemoreflexes. In: Crystal RG, West JB, Weibel ER, Barnes PJ, editors. The Lung Scientific Foundations. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott. Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 1747–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barneo J. Oxygen-sensing by ion channels and the regulation of cellular functions. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:435–440. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Montrose-Rafizadeh C, Hwang TC, Guggino WB. A delayed rectifier potassium current in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1990;57:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82632-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeja M, Musshoff U, Speckmann E-J. Follicular tissues reduce drug effects on ion channels in oocytes of Xenopus laevis. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;9:599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Wooltorton JRA, Watkins CS. Voltage-activated potassium channels in mammalian neurons and their block by novel pharmacological agents. General Pharmacology. 1998;30:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naciff JM, Behbehani MM, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR. Annexin VI modulates Ca2+ and K+ conductances of spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion neurons. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C2004–2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.6.C2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris ML, Millhorn D. Hypoxia induced protein binding to O2-responsive sequences on the tyrosine hydroxylase gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:23774–23779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipenko ON, Evans AM, Gurney AM. Regulation of the resting potential of rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes by a low threshold O2-sensitive potassium current. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honoré E. Kv2.1/Kv9.3, a novel ATP-dependent delayed-rectifier K+ channel in oxygen-sensitive pulmonary artery myocytes. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:6615–6625. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C. Hypoxic suppression of K+-currents in type I carotid body cells: Selective effect on the Ca2+-activated K+ current. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;119:253–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia MT, Lopez-Lopez JR, Gonzalez C. Kvbeta1.2 subunit coexpression in HEK293 cells confers O2 sensitivity to Kv4.2 but not to Shaker channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:897–907. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.6.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongs O. Molecular biology of voltage-dependent potassium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72:S69–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppersberg J, Stocker M, Pongs O, Heinemann S, Frank R, Koenen M. Regulation of fast inactivation of cloned mammalian IK(A) channels by cysteine oxidation. Nature. 1991;352:711–714. doi: 10.1038/352711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SN, Overturf KE, Horowitz B. Heterotetramer formation and charybdotoxin sensitivity of two K+ channels cloned from smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1729–1733. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, D'Arcangelo G, Kleinklaus A, Halegoua S, Trimmer JS. Nerve growth factor regulates the abundance and distribution of K+ channels in PC12 cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;123:1835–1843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W, Parekh AB. Electrophysiological recordings form Xenopus oocytes. In: Sackman B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel Recording. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W, Ruppersberg JP, Schroter KH, Sakmann B, Stocker M, Giese KP, Preschke A, Baumann A, Pongs O. Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO Journal. 1989;8:3235–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SC, Peers C. Hypoxia evokes cathecolamine secretion from rat phechromocytoma PC-12 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;248:13–17. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev PM, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Identification of an intracellular peptide segment involved in sodium channel inactivation. Science. 1988;241:1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Modulation of K+ channels by hydrogen peroxide. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;186:1681–1687. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Juhaszova M, Rubin LJ, Yuan X-J. Hypoxia inhibits gene expression of voltage-gated K+ channel a subunits in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100:2347–2353. doi: 10.1172/JCI119774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir EK, Archer SL. The mechanism of acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the tale of two channels. FASEB Journal. 1995;9:183–189. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WH, Conforti L, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Millhorn DE. Membrane depolarization in PC-12 cells during hypoxia is regulated by an O2-sensitive K+ current. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C658–665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WH, Conforti L, Millhorn DE. Expression of dopamine D2 receptor in PC-12 cells and regulation of membrane conductances by dopamine. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C1143–1150. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]