Abstract

On March 20, 2000, a suspected vesicular disease in cattle was reported to the National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service (NVRQS) of the Republic of Korea. This represented the index case of a foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak, which spread through several provinces. The Republic of Korea had been free of FMD for 66 years prior to the reintroduction of the virus and had recently suspended imports of pork and pork products from neighboring Japan owing to a reported FMD outbreak in that country. The Korean outbreak was ultimately controlled through the combination of preemptive slaughter, animal movement restrictions, and a strategy of ring vaccination. The purpose of this paper is to review the current FMD situation in Korea in the aftermath of its 2000 epizootic and how it may affect future efforts to eradicate or reduce risk of reintroduction of the disease into Korea.

The foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak in Korea was first reported on a dairy farm in Paju, Kyonggi province, north of Seoul and about 5 km south of the demilitarized zone. All the diseased cows showed typical clinical signs, with severe vesicular lesions of the nares, tongue, teats, and feet. Within 24 h of diagnostic confirmation from the National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service (NVRQS), the decision was made to target all infected farms for slaughter and the premises for disinfection. Additionally, movement restrictions were applied to all animals and animal products within a 20 km radius of the outbreak farm. Differential restrictions within this area consisted of 2 defined zones: a protection zone (area within 10 km radius of the outbreak farm) and a surveillance zone (area within 20 km radius of the outbreak farm). Checkpoints were placed along the border of the restriction zones and enforced by regional veterinary officers, local police, and the army.

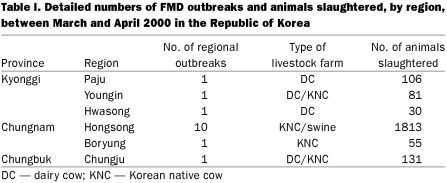

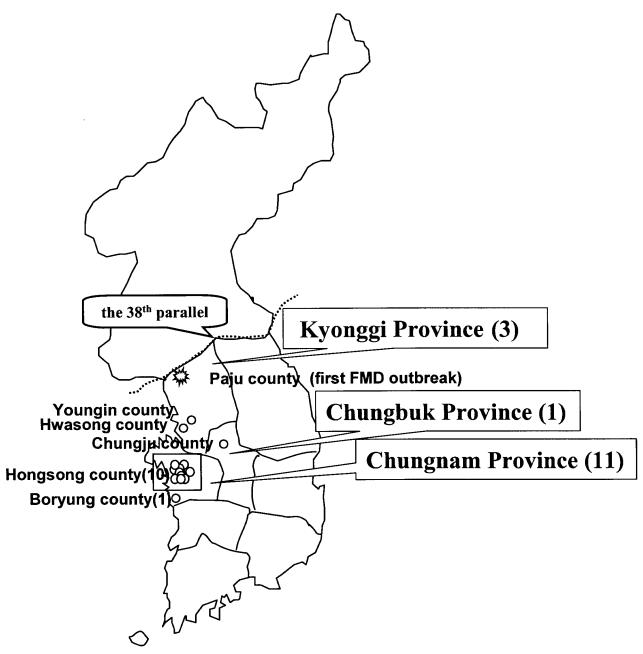

Clinical material from the first affected cows was sent to the World Reference Laboratory, Pirbright, United Kingdom, on April 4, 2000, where serotype O FMD virus (FMDV) (SKR/2000) was identified and shown by VP1 gene sequence analysis to be closely related to FMD virus serotype O/TAW/1/99 (1) and was thereby included in the Pan-Asian topotype. This resulted in cessation of pork and beef product exports from Korea. Two more outbreaks in Hongsong, Chungnam province (approximately 150 km south of the first outbreak dairy farm), and one outbreak in Chungju, Chungbuk province (approximately 140 km south-west of the first outbreak dairy farm), were reported on March 25 and April 15, 2000, respectively. By the end of April, 2216 cattle had been slaughtered and interred (Table I). These actions and limited restrictions in livestock movement effectively confined FMD to 182 cattle farms scattered in 3 northwestern provinces and prevented its spread into southern and eastern parts of the country (Figure 1).

Table I.

Figure 1. Regional FMD outbreaks in the Republic of Korea between March and April 2000. Number of outbreaks, by region, in parentheses.

Given the rapid spread of the disease within the first month, and despite the lack of an internationally accepted serodiagnostic test that differentiates vaccinated and infected animals, the decision was made in the middle of April to vaccinate all cloven-hoofed farm animals within the affected provinces. Vaccination was performed by NVRQS and provincial veterinary officers and was completed by August 2000. Vaccines were monovalent, double oil emulsion vaccines containing inactivated FMDV strain O1 Manisa; this vaccine was used because of its wide range of cross protection against several O strains. A total of 860 700 and 661 770 animals were vaccinated during the first and second (booster) rounds of vaccination, respectively, all vaccinated animals being scheduled for eventual slaughter (2). Between the first and second round vaccinations, a total of 198 930 animals had either been slaughtered according to a government indemnity program or sent by farmers to designated slaughterhouses. By the end of April 2001, 562 838 register-vaccinated animals had been slaughtered (2). Ongoing clinical and serologic surveillance of animals in the vaccinated zones as part of the national FMD surveillance program has yet to identify any new outbreak as of April 16, 2000. Between August 2000 and March 2001, veterinary and animal health inspectors visited over 646 000 cattle, pig, goat, and deer farms outside the vaccination zones: there were no confirmed cases of FMD (2). Serologic surveillance was conducted throughout the country, again without any indication of undetected viral infection.

The FMD situation worldwide has worsened within the last few years, largely owing to spread of FMD virus O Pan-Asian, whose origin is thought to be from the Indian subcontinent in the early 1990s (3,4). Out of 30 to 35 FMD outbreaks officially recorded between February 1999 and August of 2000, 18 were diagnosed in Asia (5). In addition, in 2001, 3 western European countries with long-standing FMD-free status experienced FMD outbreaks. In February to July, outbreaks in pig, cattle, and sheep were reported in the United Kingdom; in March, infected sheep were identified in France; in March/April, infected cattle, sheep, and goats were identified in The Netherlands. Sequence analysis of the VP1 gene revealed that the UK 2001 virus also belonged to the Pan-Asian O topotype of FMD viruses responsible for the outbreaks in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, far eastern Russia, Mongolia, and South Africa in the previous year (4).

Since the initial epidemic in March/April 2000, no further outbreaks have been reported in Korea, and the country has recently applied to the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) for international recognition as an FMD-free country. Similarly, Japan has been free of FMD without vaccination since March 2000. Both of these examples demonstrate that effective control of FMD can be achieved with rapid and efficient application of appropriate control measures, which include movement restrictions and preemptive slaughter, and which may include vaccination.

The origin of the reemergence of FMD in Korea and Japan after 66 and 92 years, respectively, remains unclear. Epidemiologists and virologists at the NVRQS have tried to track FMD in Korea and in the region retrospectively. The situation in China is not well documented. However, illegal entry of infected pigs into Hong Kong from mainland China has often been reported. Possible signs of the disease were detected in China several years before (6). Prior to February 2000, FMD was known to have occurred in Taiwan (7,8) and elsewhere in Asia, including the most recent outbreak of FMD in Ussuriysk district, Russia (9), and Dornogovi province, Mongolia (10). Because of the great distance, and without evidence from animal or product movement, it is unlikely that the outbreak in the territory of Korea originated in Mongolia. It was speculated that the FMD virus could have been transmitted to Korea and Japan from any place in the region by aerosolization. Even the dust storms that begin blowing eastward from China early in March could carry the virus. A more likely possibility of the origin of the Korean FMD outbreak is illegal introduction of traditional Chinese medicines, including deer antlers, and other dried or crude materials, from FMD-endemic countries. Pork and other meat from hoofed animals smuggled into Korea or Japan might also have been a source. The possible route of introduction that is being investigated now is the wind-borne spread of contaminated particles. During the 2000 and 2001 yellow sand season (March and April), 100 and 301 yellow sand samples, respectively, were collected from across the country; all tested negative for FMDV by PCR.

To date, the disease in the Korean FMD outbreak was limited solely to dairy cattle and Korean native yellow cattle, despite the probable exposure of swine. The exclusion of swine in the field outbreak raised the question of whether swine were resistant to this strain of virus O/SKR/2000, as cattle were resistant to FMD virus O/TAW/97 in Taiwan.

Experiments rapidly initiated at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center (Greenport, New York, USA) revealed that pigs are highly susceptible to the Korean FMD virus and that clinical lesions in pigs are even more severe than in cattle (field and experimental cases; in preparation for publication). The basis for restriction of newly emergent FMDV strains to certain species and the apparent discrepancy between field and experimental host range specificities are being investigated (11). From our observations of the FMD outbreak in Korea, we speculate that the lack of clinical FMD in swine is due to the prompt and complete eradication of all swine herds within the protection zones within 48 h prior to allowing the virus to multiply in piggeries. In addition, husbandry practices in cattle and swine rearing may have decreased the opportunity for viral spread.

Foot-and-mouth disease is a constant threat to animal agriculture worldwide and must always be considered when defining policies concerning the trade of live animals and animal products. It can be harbored in many parts of the environment, possibly including an animal reservoir, thus making it difficult to eliminate. As a result, FMD remains the most feared of major animal diseases.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at the Foreign Animal Disease Division, Quarantine and Inspection Division, and Pathology and Diagnostic Reference Division, NVRQS, Republic of Korea. We also thank Edan Tulman for preparation of the figure and Dr. Fred Brown and Dr. Hernando Duque for valuable discussions. This work was supported by the NVRQS, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Republic of Korea.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Jung-Hyang Sur, tel: 631-323-3012/3131, fax: 631-323-2507, e-mail: jsur@piadc.ars.usda.gov

Received October 1, 2001. Accepted February 13, 2002.

References

- 1.Office International des Epizooties. Dis Information 2000;13(14):58.

- 2.Current FMD situation in the Republic of Korea. National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Republic of Korea, 2001.

- 3.Brownlie J. Strategic decisions to evaluate before implementing a vaccine programme in the face of a foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak. Vet Rec 2001;148:358–360. [PubMed]

- 4.Knowles NJ, Samuel AR, Davies PR, Kitching P, Donaldson AI. Outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease virus serotype O in the UK caused by a pandemic strain. Vet Rec 2001;148:258–259. [PubMed]

- 5.Mason PW, Knowles NJ. Emergence and re-emergence of foot-and-mouth disease in Asia: identification and characterization of new strains of an old enemy. Proc US Anim Health Assoc, 2000. Available: www.usaha.org.

- 6.Kitching RP. A recent history of foot-and-mouth disease. J Comp Pathol 1998;118:89–108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dunn CS, Donaldson AI. Natural adoption to pigs of a Taiwanese isolate of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Vet Rec 1997;141:174–175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Yang PC, Chu RM, Chung WB, Sung HT. Epidemiological characteristics and financial costs of the 1997 foot-and-mouth disease epidemic in Taiwan. Vet Rec 1999;145:731–734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Office International des Epizooties. Dis Information 2000; 13(15):63.

- 10.Office International des Epizooties. Dis Information 2000; 13(19):76.

- 11.Beard CW, Mason PW. Genetic determinants of altered virulence of Taiwanese foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol 2000;74: 987–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]