Abstract

The modulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels by the nitric oxide (NO) donors S-nitroso-L-cysteine (NOCys) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and agents which oxidize or reduce reactive thiol groups were compared in excised inside-out membrane patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci.

When the cytosolic side of excised patches was bathed in a physiological salt solution (PSS) containing 130 mm K+ and 15 nm Ca2+, few BKCa channel openings were recorded at potentials negative to 0 mV. However, the current amplitude and open probability (NPo) of these BKCa channels increased with patch depolarization. A plot of ln(NPo) against the membrane potential (V) fitted with a straight line revealed a voltage at half-maximal activation (V0.5) of 9.4 mV and a slope (K) indicating an e-fold increase in NPo with 12.9 mV depolarization. As the cytosolic Ca2+ was raised to 150 nm, V0.5 shifted 11.5 mV in the negative direction, with little change in K (13.1 mV).

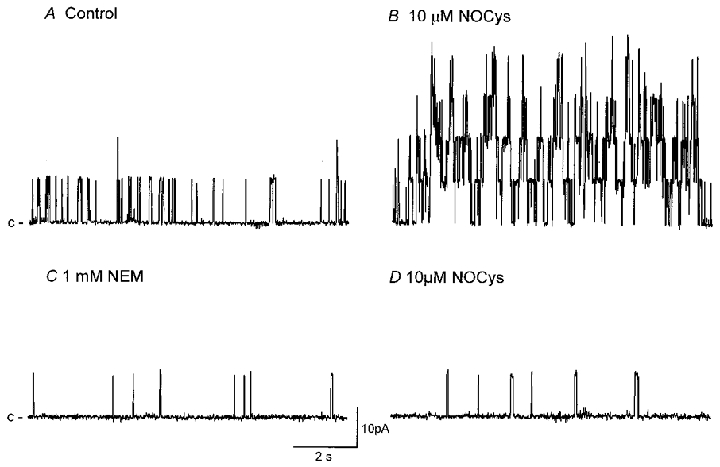

NOCys (10 μm) and SNP (100 μm) transiently increased NPo 16- and 3.7-fold, respectively, after a delay of 2–5 min. This increase in NPo was associated with an increase in the number of BKCa channel openings evoked at positive potentials by ramped depolarizations (between −60 and +60 mV). Moreover, this NOCys-induced increase in NPo was still evident in the presence of 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ; 10 μm), the specific blocker of soluble guanylyl cyclase.

The sulfhydryl reducing agents dithiothreitol (DTT; 10 and 100 μm) and reduced glutathione (GSH; 1 mm) also significantly increased NPo (at 0 mV) 7- to 9-fold, as well as increasing the number of BKCa channel openings evoked during ramped depolarizations.

Sulfhydryl oxidizing agents thimerosal (10 μm) and 4,4′-dithiodipyridine (4,4DTDP; 10 μm) and the thiol-specific alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; 1 mm) significantly decreased NPo (at 0 mV) to 40–50 % of control values after 5–10 min. Ramped depolarizations to +100 mV evoked relatively few BKCa channel openings.

The effects of thimerosal on NPo were readily reversed by DTT, while the effects of NOCys were prevented by NEM.

It was concluded that both redox modulation and nitrothiosylation of cysteine groups on the cytosolic surface of the α subunit of the BKCa channel protein can alter channel gating.

It is now well established that the release of nitric oxide (NO), or a NO-related compound, forms an essential part of the processes which underlie endothelium-dependent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and the relaxation of the circular muscle layer in the gastrointestinal tract evoked upon stimulation of intrinsic non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic (NANC) inhibitory motor neurones. Throughout the gastrointestinal tract, the muscle relaxation and transient membrane hyperpolarization (inhibitory junction potential; IJP) recorded upon NANC nerve stimulation can be divided into a component reduced by apamin, the blocker of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SKCa) channels (Blatz & Magelby, 1986), and a component sensitive to inhibitors of NO synthase (NOS). However, there are many gastrointestinal preparations in which these components are not mutually exclusive, such that apamin can reduce the component sensitive to NOS inhibition in the human colon and dog pylorus (Keef et al. 1993; Bayguinov & Sanders, 1993), while NOS inhibitors may also reduce the ‘apamin-sensitive’ component in the dog ileocolonic sphincter (Ward et al. 1992b). The NO released from NANC nerves, endothelial cells and from many nitrovasodilators has generally been thought to mediate smooth muscle relaxation via the stimulation of cytosolic guanylyl cyclases (Gruetter et al. 1981; Cayabyab & Daniel, 1995). However, there is growing evidence that the muscle relaxation and membrane hyperpolarisation in many smooth muscle preparations induced by endogenously released NO or externally applied NO donors can occur in a manner independent of cGMP formation (Bayguinov et al. 1992; Ward et al. 1992a; Bayguinov & Sanders, 1993; Kitamura et al. 1993; Bolotina et al. 1994; Watson et al. 1996).

The NO donor-induced membrane hyperpolarizations recorded in myocytes of smooth muscle have been reported to arise from both an increase in the membrane K+ conductance (Lang & Watson, 1998) and a decrease in a Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance (Zhang et al. 1998). In single myocytes of the opossum oesophagus (Murray et al. 1995), guinea-pig proximal colon (Lang & Watson, 1998) and rat mesenteric artery (Mistry & Garland, 1998), NO donors have been demonstrated to increase the whole-cell K+ current activated upon membrane depolarisation. This increased outward current is blocked by charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin, specific blockers of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels (Murray et al. 1995; Mistry & Garland, 1998). The effects of NO donors were mimicked by membrane-permeable analogues of cGMP and partially blocked by specific inhibitors of soluble guanylyl cyclase in the guinea-pig proximal colon and opossum oesophagus, but not in the rat mesenteric artery. At the single channel level, both NO donors, NOCys and S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine (SNAP), and membrane-permeable analogues of cGMP increased the open probability of BKCa channels recorded in cell-attached patches on colonic myocytes of the guinea-pig or dog (Koh et al. 1995; Lang & Watson, 1998). However, NO- and NO donor-induced increases in BKCa channel activity were still evident in excised membrane patches of the guinea-pig proximal colon (Lang & Watson, 1998) and rat mesenteric artery and rabbit aorta (Botolina et al. 1994; Mistry & Garland, 1998), but not in patches excised from myocytes of the dog colon (Koh et al. 1995).

In the guinea-pig taenia caeci, the IJP and muscle relaxation recorded in response to a single nerve stimulation is sensitive to blockade by apamin, but not to NOS inhibition. However, the muscle relaxation of the taenia caeci recorded upon repetitive NANC nerve stimulation (5-20 Hz for 10 s), is sensitive to NOS inhibition, particularly in the presence of apamin (Selemidis et al. 1997). In this report, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which the NO donors NOCys and SNP affect the activity of BKCa channels in excised membrane patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci. Moreover, we have compared the effects of these NO donors with the effects of agents which oxidize/reduce cysteine residues on the BKCa channel protein/s. We have established that both NOCys and SNP directly increase BKCa channel opening; possibly by the nitrothiosylation of thiol groups on the BKCa channel protein. Some of these results have been presented previously in brief (McPhee & Lang, 1994; Harvey & Lang, 1998).

METHODS

Single cell preparation

Guinea-pigs were killed by stunning and exsanguination, the caecum was exposed through an abdominal incision and the taenia caeci dissected free. All experiments were carried out using procedures approved by the Physiological Department Animal Ethics Committee at Monash University. Single smooth muscle myocytes were enzymatically dispersed from 5 mm strips of guinea-pig taenia caeci in a low-Ca2+ (50 μM) physiological salt solution (PSS; see below) with added collagenase (0.5 mg ml−1, Worthington), trypsin inhibitor (0.5 mg ml−1, Sigma) and bovine serum albumin (2 mg ml−1, Sigma) at 37°C (see Lang et al. 1991). Single cells were either stored at 4°C or plated onto the glass base of a recording chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Olympus CK2). Cells were allowed 5–10 min to settle and then perfused for 2–5 min with a normal Ca2+ (1.5 mM)-containing PSS (see below) prior to commencing patch-clamp experiments.

Solutions

Cells were dispersed in a low-Ca2+ PSS containing (mM): NaCl 126, KCl 6, Na-Hepes 10, MgCl2 1, D-glucose 10, EGTA 0.3 and CaCl2 50 μM. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.4 with 5 M NaOH. Following dispersion, the Ca2+ concentration was increased to 1.5 mM (normal Ca2+) before cell storage or experimentation. Excised patches were bathed in a high-K+, low-Ca2+ PSS containing (mM): KCl 126 or 130, Na-Hepes 10, MgCl2 1, D-glucose 10, EGTA 0.3 and CaCl2 50 μM, which gives a calculated free Ca2+ concentration of 15 nM. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.4 with 5 M KOH. Cells were routinely perfused with this high-K+ (126 or 130 mM), low-Ca2+ (15-30 nM) PSS after the formation of a seal (> 2 GΩ) between the pipette and the smooth muscle membrane and prior to patch excision. Inside-out patches were then excised into this high-K+ PSS, establishing either a symmetrical high-K+ (126 or 130 mM [K]o: 126 or 130 mM [K]i), low-Ca2+ gradient (15-30 nM) or a near-physiological Ca2+ and K+ (6 mM [K]o: 130 mM [K]i) gradient across the membrane patch. All recordings were made at room temperature (22-25°C) (Lang & Watson, 1998).

Single channel recording and analysis

Patch pipettes were drawn from glass capillary tubing (1.5-1.8 mm; Clarke Electromedical Instruments) on a micropipette puller (Sachs-Flaming PC-84, Sutter Instruments) and pipette tips were heat polished (MF-84 Microforge, Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab.). Pipette resistances ranged between 4 and 10 MΩ. Command potentials were delivered and channel currents recorded using an Axopatch 200 amplifier (3 dB cutoff frequency 1 kHz, 4-pole Bessel filter; Axon Instruments). Patch potentials and channel currents were stored on video tape via a Digital Data Recorder VR10B, (Instrutech Corp.) and later digitized (at 2 kHz) onto a computer hard disk for analysis using a DigiData 1200 Interface (Axon Instruments) and pCLAMP 6 software (Axon Instruments). Channel openings were recorded for 30–120 s at holding patch potentials between −100 and +100 mV.

In most patches when the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was 15 nM, two to six active BKCa channels were observed at positive potentials. BKCa channel activity was therefore quantified using the methods described by Singer & Walsh (1987). Briefly, channel current levels at each holding potential were first plotted as an all-points amplitude histogram. Closed and opened levels were fitted with single Gaussian distributions (using a Simplex least squares algorithm), the difference between the mean of each Gaussian giving an estimate of the amplitude (I, pA) of the BKCa channel currents at each patch potential (V, mV). The area under each fitted Gaussian was used to calculate the relative probability (PL) of the patch current being open at each current level (L) by dividing the summed time spent at each level by the total observation time. The mean open probability for N channels (NPo) was therefore:

Typically, ln(NPo) was plotted against V and fitted to the straight line:

| (1) |

where V0.5 and K represent the voltage of half-maximal activation and the slope of the line, respectively (Singer & Walsh, 1987; Lang & Watson, 1998).

Patches were sometimes subjected to a ramped depolarization (between −100 and +100 mV over 1 s) from a holding potential between 0 and +40 mV. These ramp-evoked channel currents (I) were then plotted against the patch potential (V) to give ‘instantaneous’ current-voltage (I–V) plots, which were used to follow any time-dependent changes in BKCa channel activity.

Drugs

Stock solutions of S-nitroso-L-cysteine (NOCys, 100 mM) were prepared as previously described (Lang & Watson, 1998). Sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 0.1 mM; May and Baker) was dissolved in distilled water. Both NOCys and SNP stock solutions were stored at −20°C for no more than 7 days. Dithiothreitol (DTT), reduced glutathione (GSH), thimerosal and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) were dissolved in distilled water and stored at 4°C. 4,4′-Dithiodipyridine (4,4DTDP) was dissolved initially in ethanol and diluted in distilled water. The infusion of the vehicles for NOCys and 4,4DTDP at their final concentrations had no effect on BKCa channel activity. All stock solutions were diluted with PSS and applied as a bolus (1-100 μl) to the bath solution (volume of 0.2 ml); the concentrations indicated throughout the results are the calculated final concentrations.

Immunohistochemistry for BKCa channels and α smooth muscle actin

Single myocytes (obtained as above) were allowed to settle onto glass coverslips, fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (for 2 h) and then rinsed (30 min) in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5 % Triton X-100 (PBS/Triton), in DMSO for 20 min and for a further 10 min in PBS. Cells were then incubated overnight in a mixture of rabbit anti-BKCa channel polyclonal antibody (1:100, Alomone) and mouse anti α smooth muscle actin (1: 800, Sigma). Cells were then rinsed in PBS, incubated for 1 h in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham, 1: 200) and rinsed again, prior to incubation (for 1 h) in a mixture of streptavidin-CY3 (1:1000, Jackson Immunoresearch) and anti-mouse Oregon green (1:100, Molecular Probes). For negative control sections, PBS replaced the primary antibodies. Some cells from each animal were also prepared for single-label immunohistochemistry for each antibody using the same protocols. After rinsing away any excess antibody in PBS, preparations were mounted using DAKO mounting medium (Dako Corporation) and examined using a confocal microscope (Leica TCS NT) equipped with ×40, ×63 and ×100 oil immersion lenses, and set up for double-label immunohistochemistry. To detect CY3 in one channel, specimens were excited using the 568 nm line of the Kr/Ar laser, and emissions were detected through a 665 nm long pass filter. To detect Oregon green, specimens were simultaneously excited using the 488 nm line of the Kr/Ar laser, and emissions were detected through a 530/30 nm bandpass filter. Preparations were scanned and the gain settings adjusted to maximize the signal while reducing the background signal. Images from a single X–Y confocal plane, or X-Y-Z stacks were collected and saved to a computer hard disk. 3-Dimensional reconstructions of X-Y-Z series were made using Voxblast software (VayTek, Fairfield, IA, USA).

RESULTS

Localization of BKCa channels

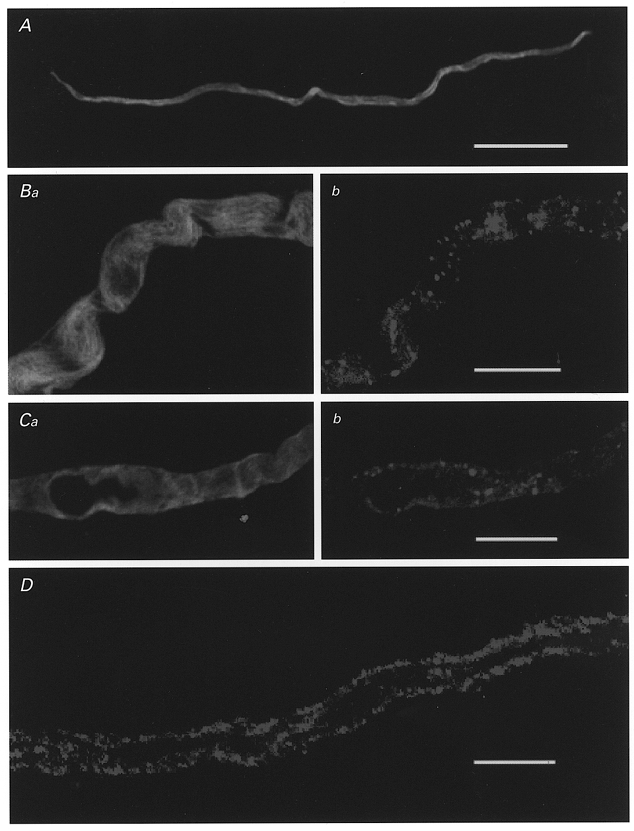

Dispersed taenia caeci myocytes treated to reveal immunoreactivity for α smooth muscle actin appeared as long, narrow spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 1A), 351 ± 25 μm (range 159–582 μm) in length and 11.3 ± 0.74μm (range 6–19 μm) wide at the nuclear region, tapering slowly to the ends (n = 23 cells from 3 animals). Figure 1B and C illustrates single confocal sections (150 nm in thickness) through portions of dissociated myocytes at higher magnification (×300), stained for both α smooth muscle actin (Fig. 1Ba and Ca), and the COOH terminal region of any BKCa channels present (Fig. 1Bb and Cb). Most myocytes showed an evenly distributed staining for α smooth muscle actin, except where the plane of focus was on the cell surface (Fig. 1Ba) or through the nucleus (Fig. 1Ca). Immuno-staining for BKCa channels was associated with the cell membrane and most clearly evident in the regions where the plane of focus rested on the cell membrane (Fig. 1Bb). When the plane of focus of single myocytes was taken at the level of the nucleus, immunoreactivity for BKCa channels was seen near the edge of the cell (Fig. 1Cb). Finally, when the confocal section passed through the centre of myocytes immuno-stained only for BKCa channels, clusters of BKCa channel immunoreactivity were readily evident within the submembrane region at the edges of the cell (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Localisation of BKCa channels in freshly isolated myocytes of the guinea-pig taenia caeci.

Low magnification confocal micrographs of single myocytes after immuno-staining for either α smooth muscle actin (A) or the COOH terminus of the α subunit of mouse BKCa channel (mslo) (D). Some cells were stained for both α smooth muscle actin (Ba, Ca) and the anti-BKCa channel antibody (Bb, Cb). Calibration bars: A, 50 μm; B–D, 10 μm.

Single channel recordings

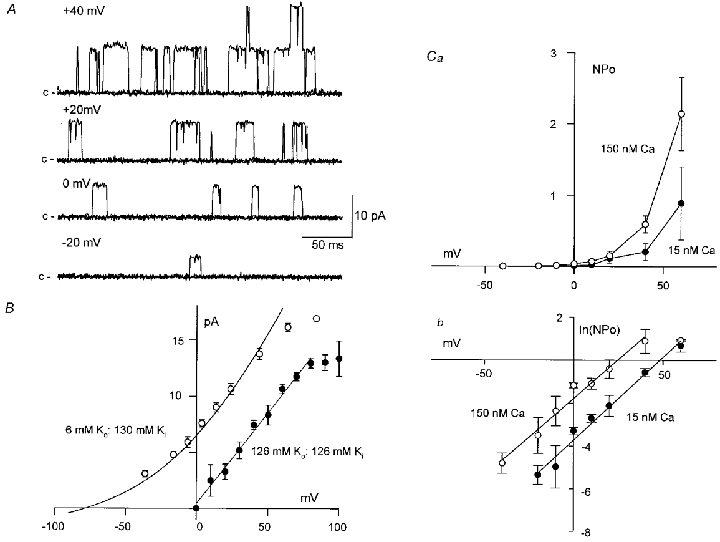

In excised membrane patches exposed to the near-physiological K+ gradient (6 mM [K]o: 130 mM [K]i) and a cytosolic Ca2+ concentration of 15 nM, single BKCa channel openings were seldom recorded at potentials < 0 mV. At 0 mV, BKCa channel currents were 7.6 ± 0.3 pA in amplitude and had an open probability (NPo) of 0.012 ± 0.007 (n = 4). However, both the current amplitude and NPo of these BKCa channels increased with depolarization of membrane patches to positive potentials (Fig. 2A, B and Ca). Between −40 and +40 mV, the plot of the current amplitude (I) of these BKCa channels against V was well fitted by the Goldman-Huxley-Hodgkin constant field equation for a K+-selective channel (see Benham et al. 1986), after a tip potential correction of 3.7 mV. In excised patches (n = 10) bathed in the symmetrical high-K+ gradient (126 mM [K]o: 126 mM [K]i), the mean I–V plot of these BKCa channels demonstrated a linear relationship between −20 and +80 mV and a marked curvature at potentials positive to +80 mV (Fig. 2B, •). This reduction of channel current amplitude at positive potentials in both the symmetrical and near-physiological K+ gradients (at potentials positive to +40 mV) was often associated with an increase in the frequency of fast transitions (‘flickers’) to the closed state during individual channel openings. A similar blockade of channel currents was also seen at potentials positive to +40 mV in cell-attached patches (n = 13) bathed in the symmetrical K+ gradient (data not shown). This inward rectification of the I–V plots at positive potential presumably arises from blockade of outward current flow by cytosolic constituents such as Na+ or Mg2+or soluble proteins, which are reduced upon membrane excision (Benham et al. 1986; Singer & Walsh, 1987). The conductance (167 pS) of these BKCa channels was therefore calculated from the slope of the straight line fitted (by linear regression) to the mean I–V relationship (between 0 and +80 mV) obtained from excised patches (n = 10) bathed in the symmetrical high 126 mM K+ PSS (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Properties of BKCa channels recorded in excised inside-out patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci.

When the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was fixed at 15 nM, single BKCa channel openings increased in frequency as the patch was held at more positive potentials (Fig. 2A and Ca, •). In Fig. 2Cb (•), the averaged plot of ln(NPo) against V (n = 3) in 15 nM Ca2+ has been fitted, by least squares, to eqn (1) to give V0.5 and K values of +9.03 and 12.01 mV, respectively. These values are in good agreement with the mean estimates of these values obtained from the individual plots of ln(NPo) against V, with V0.5 and K being +9.4 ± 2.2 mV and 12.9 ± 0.6 mV (n = 3), respectively. When the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was raised to 150 nM, BKCa channel activity was increased at all potentials (Fig. 2Ca, ○). This increase in channel activity in 150 nM Ca2+ was evident as a parallel shift to the left of the plots of ln(NPo) against V, without any change in slope, such that V0.5 and K were −1.9 ± 2.8 mV (n = 3, P < 0.05, paired t test) and 13.1 ± 1.4 mV (n = 3, P > 0.05), respectively, in 150 nM Ca2+ (Fig. 2Cb, ○).

Effects of the NO donors NOCys and SNP

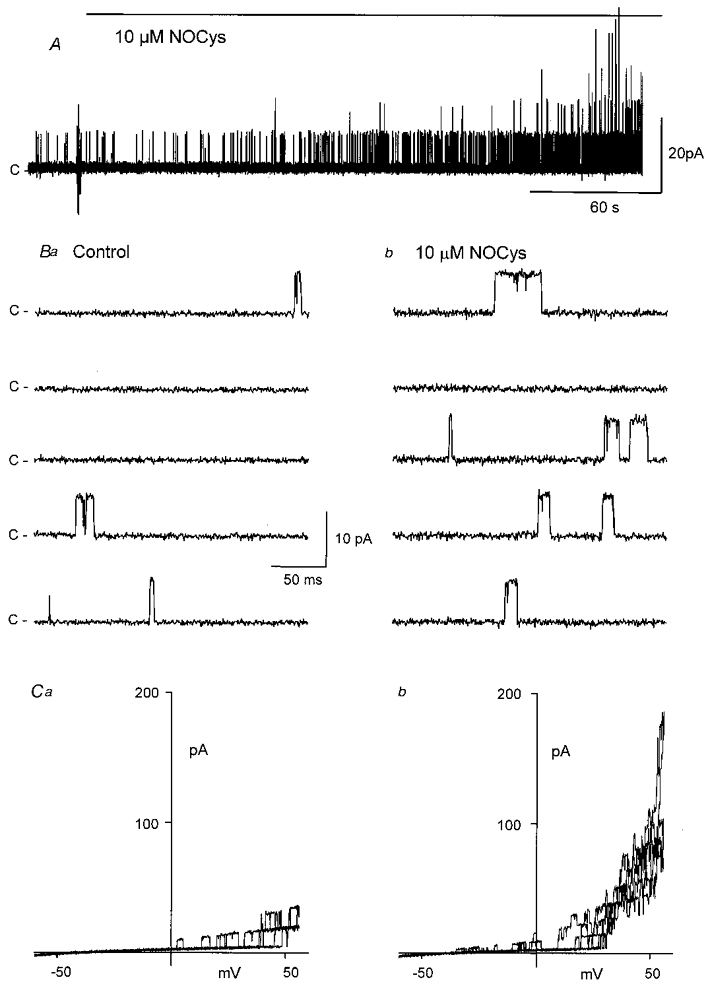

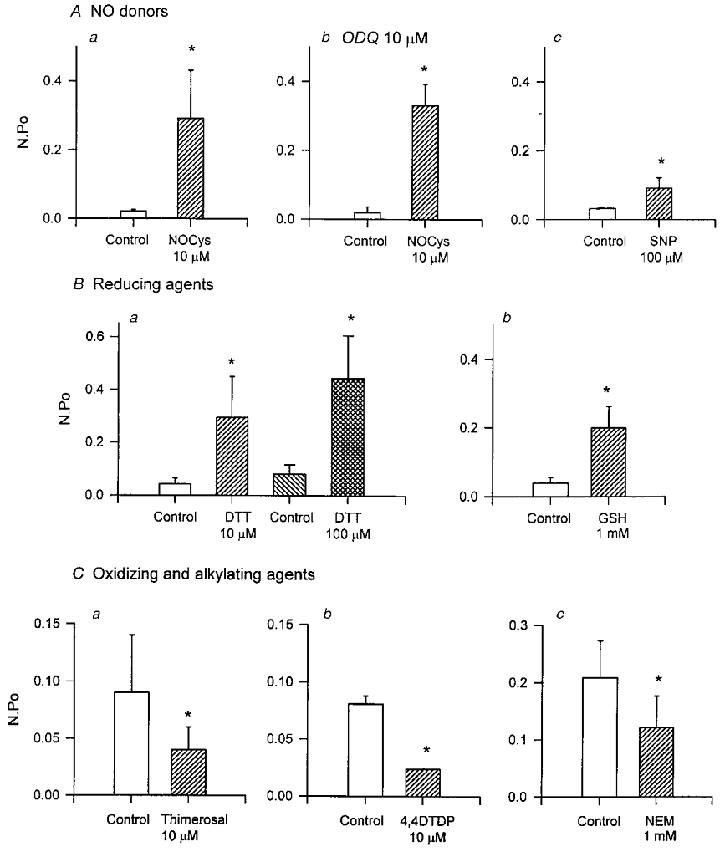

S-nitroso-L-cysteine (NOCys) is a S-nitrosothiol compound that is relatively unstable in PSS such that NOCys has a half-life of about 80 s. In contrast, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is another nitrovasodilator, which releases NO more slowly. When NOCys (10 μM) was added to the cytosolic surface of the excised membrane patch bathed in the physiological K+ (6 mM [K]o: 130 mM [K]i) gradient, BKCa channel activity increased after a delay of about 60 s (Fig. 3A and B). In seven experiments, 10 μM NOCys increased NPo (at 0 mV) to 1609 ± 643 % (P < 0.05, Student's paired t test) of control within 5 min (Fig. 6Aa). In contrast, SNP (100 μM) increased NPo to only 372 ± 113 % (P < 0.05) of control after 6–8 min (Fig. 6Ac). In patches bathed in the symmetrical high-K+ (30 nM Ca2+) gradient, NOCys (5 and 10 μM) and SNP (100 μM) increased the mean NPo values (at +40 mV) after 5 min to 0.12 ± 0.05, 0.8 ± 0.4 and 0.09 ± 0.03, respectively, significantly larger than their respective control NPo values of 0.02 ± 0.004 (n = 7), 0.21 ± 0.18 (n = 5) and 0.03 ± 0.01 (n = 7, all P < 0.05). The effects of both NOCys and SNP slowly decayed over 5–10 min in the continued presence of the NO donor. Moreover, the effects of both NO donors were mostly, but not completely, reversible. NPo values generally returned to near control values after 15–20 min washout (data not shown).

Figure 3. S-nitroso-L-cysteine (NOCys) activation of BKCa channels in excised patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci.

A, addition of NOCys (10 μM) to the cytosolic surface increased BKCa channel activity (at 0 mV) in membrane patches bathed in the near-physiological K+ gradient, after a delay of some 60–120 s. B, typical channel openings at 0 mV before (a) and 10 min after (b) the application of NOCys (10 μM). C, comparison of the channel activity evident during ramped depolarizations (3 ramp depolarizations between −60 and +60 mV every 10 s) in the absence (a) and 5 min after the application (b) of NOCys (10 μm); holding potential 0 mV.

Figure 6. Summary of the effects of NO donors and agents, which oxidize, reduce or alkylate cellular proteins on BKCa channel activity in excised patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci.

Both NOCys (10 μM, n = 7; Aa) and SNP (100 μM, n = 7; Ac) significantly increased NPo (at 0 mV, both P < 0.05) measured 5–10 min after application, in either the absence (Aa, c) or in the presence (Ab) of ODQ (10 μM), the specific inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase. The effects of the NO donors were mimicked by the reducing agents DTT (10 and 100 μM, n = 4 and 8; Ba) and reduced glutathione (GSH, 1 mM, n = 5; Bb). In contrast, both the oxidizing agents thimerosal (10 μM, n = 7; Ca) and 4,4DTDP (10 μM, n = 7; Cb) and the specific alkylating agent NEM (1 mM, n = 9; Cc), decreased NPo measured 10 min after application (all P < 0.05). The significant effects of applied agents were established using Student's paired t tests or repeated measured ANOVAs as appropriate. *P < 0.05.

The effects of these NO donors was also examined in cell-attached patches in which the membrane potential had been zeroed by bathing the cell in the 126 mM K+ PSS. In ten cell-attached patches, NOCys (10 μM) significantly increased the mean NPo (at +40 mV) 5-fold from 0.08 ± 0.03 to 0.41 ± 0.1 (P < 0.05, paired t test), while 100 μM NOCys significantly increased NPo to 2.42 ± 0.68 (control NPo of 0.15 ± 0.06, n = 4, P < 0.05). In contrast, SNP (100-300 μM applied for 2–15 min) had little effect on BKCa channel activity recorded in cell-attached patches (P > 0.05, n = 5), even though the subsequent addition of 10 μM NOCys increased NPo in the same patch (n = 3; data not shown), suggesting that SNP experienced some difficulty crossing the cell membrane before the release of it's NO.

To exclude the possibility that this effect of NOCys on BKCa channel activity occurred via the activation of either cytosolic or membrane-bound guanylyl cyclases, cells were bathed in the presence of the specific guanylyl cyclase blocker 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ, 10 μM). After a 20 min exposure to ODQ (10 μM), NOCys (10 μM) still increased NPo 2900 ± 352 % (n = 6, P < 0.05) of control within 5 min (Fig. 6Ab). Similar results were obtained with bathing cells in methylene blue (10-50 μM) for 30–90 min (at 37°C) prior to and during experimentation. NOCys (10-100 μM) in the presence of methylene blue (10 μM) still increased BKCa channel activity in both cell-attached (n = 3) and excised inside-out patches (n = 2; data not shown).

Voltage-dependent effects of NOCys

We attempted to examine the voltage-dependent effects of NOCys (10 μM) using the same holding potential protocols (between −40 and +80 mV for 30–60 s) when the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was altered (Fig. 2C). In six patches, the individual plots of ln(NPo) against V gave mean V0.5 and K values of 6.13 ± 2.9 mV and 12.72 ± 1.14 mV, respectively, in the presence of NOCys (10 μM), not significantly different from their respective control values of 5.19 ± 2.26 mV and 11.67 ± 0.79 mV (P > 0.05) (data not shown). However, these experiments have to be treated with caution due to the long periods (5-10 min) of channel sampling required during the generation of each NPo-V curve, compared to the relatively transient nature of the effects of NOCys.

The voltage-dependent effects of NOCys were therefore examined using the ramped depolarizations (between −60 and +60 mV over 1 s) applied every 10 s before (Fig. 3Ca) and during (Fig. 3Cb) the peak response to NOCys (10 μM). During these applied ramp depolarizations, NOCys evoked a time-dependent increase in the number of active channels (from 1–3 to 8–10 channels) opening simultaneously at positive potentials. Moreover, more BKCa channel openings were evident at potentials negative of 0 mV, as might be expected with a substantial shift to the left of these ‘activation’ curves (Fig. 3C b).

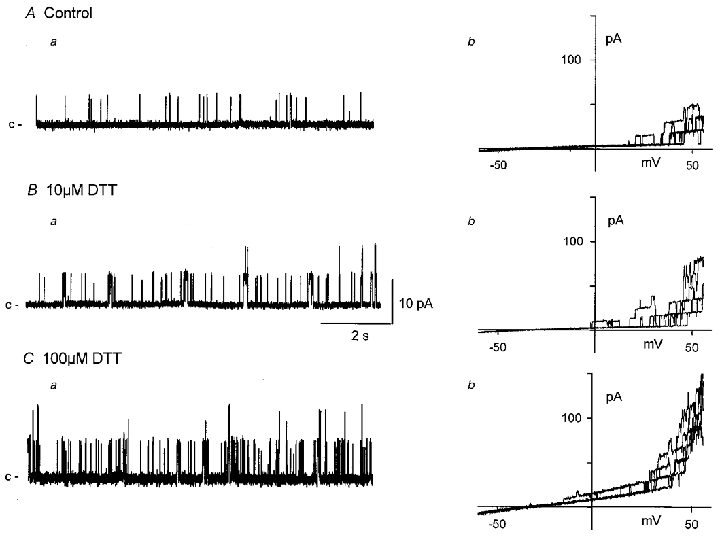

Effects of dithiothreitol and reduced glutathione

Dithiothreitol (DTT) is a disulfide reducing agent, which prevents the excitatory effects of NO donors on BKCa channels isolated from tracheal sarcolemmal vesicles (Abderrahmane et al. 1998), small conductance K+ channels in canine colonic myocytes (Koh et al. 1995) and Ca2+-activated cationic channels in single cells of rat adipose tissue (Koivisto & Nedergaard, 1995). In the present experiments, application of DTT (10 and 100 μM for 2–8 min) to the cytosolic surface of excised membrane patches increased NPo (at 0 mV) to 709 ± 269 % (n = 4; Figs 4B and 6Ba) and 878 ± 388 % (n = 8, both P < 0.05; Figs 4C and 6Ba), respectively, of their control values. These excitatory effects of DTT were mostly irreversible, even after 15–20 min washout (data not shown).

Figure 4. The disulfide reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) activates BKCa channels in excised inside-out patches.

Application of DTT to the cytosolic surface of excised patches bathed in a near-physiological K+ gradient (at 0 mV) causes a concentration-dependent activation of BKCa channels (Aa, Ba, Ca). Plots of BKCa channel activity against patch potential evoked during ramped depolarizations (5 ramps between −60 and +60 mV evoked every 10 s) in the absence (Ab) and after 10 min exposure to 10 μM (Bb) or 100 μM (Cb) DTT. The effects of DTT were not reversed after 10 min washout.

Glutathione is an endogenous redox agent, which is mainly present in its reduced form (GSH) due to the reducing environment of most cells (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997). The application of GSH (1 mM) also evoked a time-dependent increase in BKCa channel activity: NPo increased to 831 ± 352 % (n = 5, P < 0.05; Fig. 6Bb) of control after 10 min. As intracellular GSH concentrations vary between 0.1 and 1 mM, these data establish that the reduction of disulfide groups is likely to be of physiological relevance and occurs on the intracellular surface of the membrane patches (Wang et al. 1997).

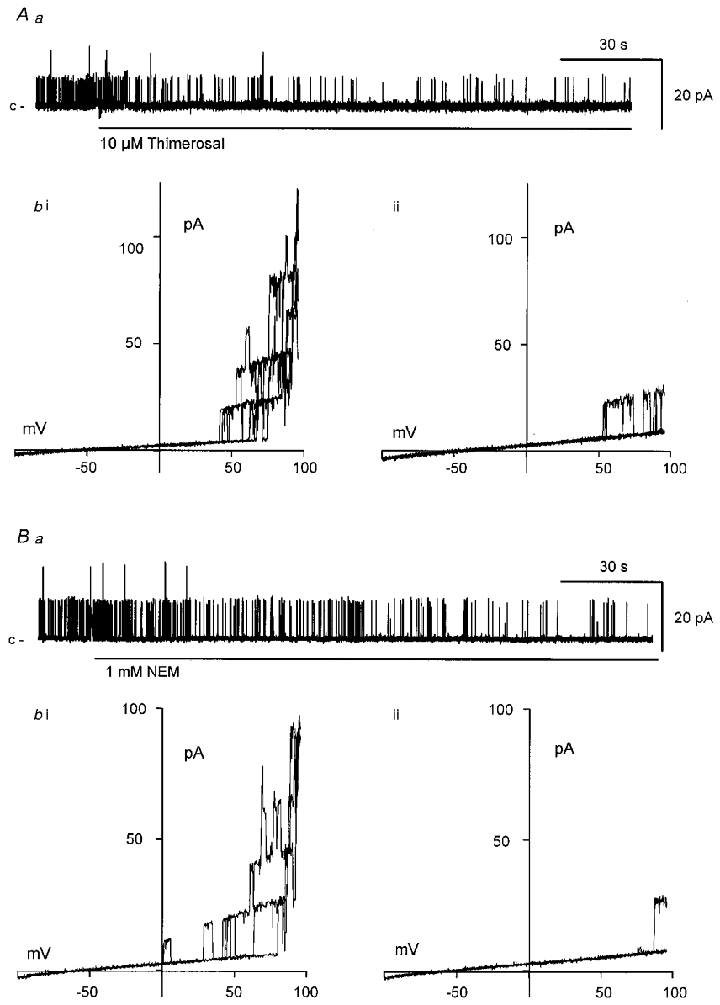

Effects of sulfhydryl oxidizing agents thimerosal and 4,4′-dithiodipyridine

The effects of the sulfhydryl oxidizing agents thimerosal and 4,4′-dithiodipyridine (4,4DTDP) added to the PSS bathing the cytosolic surface of excised membrane patches was also examined. As shown in Fig. 5A, thimerosal (10 μM) rapidly decreased (within 2 min) BKCa openings recorded either at 0 mV (Fig. 5Aa) or evoked during ramped depolarizations (Fig. 5Ab i and ii). After 10 min exposure to thimerosal (10 μM), NPo was decreased to 46.7 ± 16.5 % (n = 7) of control (Fig. 6C a). Channel activity was also decreased by the reactive disulfide 4,4′-dithiodipyridine (4,4DTDP, 10 μM), such that after 5 min NPo was decreased to 47.7 ± 16.6 % (n = 7) of its control value (Fig. 6C b). In most experiments, the inhibitory effects of both oxidizing agents persisted, even after 15 min washout and multiple exchanges of the bath volume.

Figure 5. Thiol oxidation or alkylation inhibits BKCa channel activity.

Application of either the sulfhydryl oxidizing agent thimerosal (10 μM; Aa) or the specific alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, 1 mM; Ba) to the cytosolic surface decreased BKCa channel activity (at 0 mV) within 60–120 s. Ab and Bb, plots of BKCa channel activity against patch potential evoked during ramped depolarizations (3 ramps between −100 and +100 mV evoked every 10 s) in the absence of either agent (Ab i, Bb i) or after 10 min exposure to either 10 μM thimerosal (Ab ii) or 1 mM NEM (Bb ii). The effects of either agent were not reversed after 10 min washout.

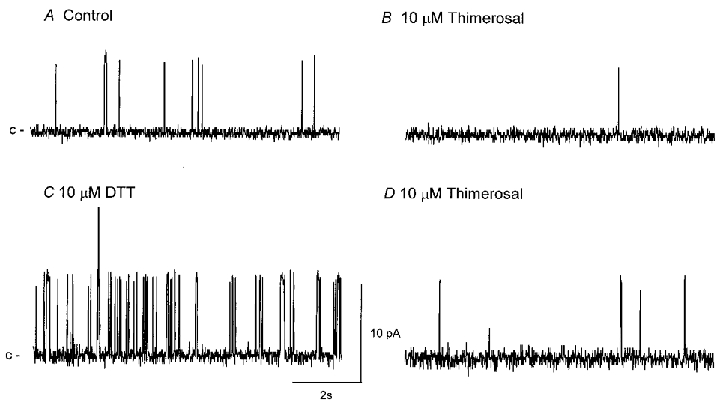

To establish whether these redox agents were indeed affecting the redox state of the BKCa channels, we examined whether the effects of sulfhydryl oxidation could be reversed by a subsequent sulfhydryl reduction, and vice versa. In Fig. 7, the oxidizing agent thimerosal (10 μM) decreased BKCa channel activity recorded either during a maintained holding potential (at 0 mV; Fig. 7A and B) or during ramp depolarizations (data not shown), which persisted long after washout. However, channel openings readily returned upon exposure to DTT (10 μM; Fig. 7C). This increase in channel activity also remained after washout of the DTT, but could be inhibited by the subsequent addition of thimerosal (10 μM; Fig. 7D). Similar results were observed in two other experiments (Wang et al. 1997).

Figure 7. Patch oxidation with thimerosal reverses the effects of reduction with DTT.

Typical traces of BKCa channel activity in an excised patch bathed in a near-physiological K+ gradient (holding potential 0 mV) before (A; control NPo of 0.014) and 5 min after (B) the application of thimerosal (10 μM; NPo of 0.002 after 5 min). The effects of thimerosal remained after washout (NPo of 0.003) but were rapidly reversed upon the application of DTT (10 μM; NPo of 0.371 after 5 min; C). The effects of DTT were mostly irreversible upon washout (NPo 0.116 after 10 min washout), but rapidly blocked upon the subsequent application of thimerosal (10 μM; NPo of 0.012; D).

Effects of N-ethylmaleimide

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) is a specific alkylating agent of free thiol (RSH) groups on cysteine residues. If the actions of NO donors and redox agents described above involve the crosslinking of free thiols on the BKCa channel protein/s, NEM should covalently modify any available thiols, preventing disulfide bond formation and any subsequent alteration in channel gating. The application of NEM (1 mM for 10 min) to the cytosolic surface of excised patches decreased BKCa channel openings recorded either during maintained membrane holding potentials (0 mV; Fig. 5Ba) or during applied ramp depolarizations (Fig. 5Bb i and ii). NPo recorded 5 min after exposure to NEM was decreased to 46.9 ± 11.5 % (n = 9, P < 0.05) of control (Fig. 6Cc and persisted after washout.

It has been previously demonstrated that alkylation of free thiol groups on cysteine residues of BKCa channels prevents the inhibitory actions of the oxidizing agents diamide and thimerosal (Wang et al. 1997). In the present experiments, we examined whether thiol alkylation with NEM could prevent the excitatory actions of NOCys. In Fig. 8, BKCa channel openings (at 0 mV) were readily increased by NOCys (10 μM; Fig. 8B), and declined slowly (over 10–20 min) upon washout of the NO donor. However, the addition of NEM (1 mM) after 5 min washout of NOCys rapidly reduced BKCa channel openings (Fig. 8C) to below control levels. Moreover, BKCa channel activity remained low after 10 min washout of NEM. The subsequent addition of NOCys (10 μM) failed to evoke any further increase in NPo (Fig. 8D). In six experiments, NPo was 0.02 ± 0.008 after 10 min exposure and 10 min washout of NEM (10 μM) and was not significantly increased by a subsequent application of NOCys (10 μM; NPo of 0.026 ± 0.013, P > 0.05). The time-matched control for these experiments involving exposing membrane patches to two applications of NOCys (10 μM) 20–30 min apart revealed that NPo was readily increased by both the first and the second application of NOCys (n = 4).

Figure 8. Thiol alkylation inhibits BKCa channel gating and prevents the effects of NOCys.

BKCa channel activity in an excised patch bathed in a near-physiological K+ gradient (holding potential 0 mV) before (A; control NPo of 0.134) and 5 min after (B) the application of NOCys (10 μM; NPo was 1.698). The effects of NOCys were slowly reversible upon washout (NPo of 1.282 after 10 min washout) but were rapidly decreased by NEM (1 mM; NPo of 0.049 after 5 min exposure; C), and remained low after washout (NPo of 0.04). Subsequent application of NOCys (10 μM) had little effect on NPo (0.009 after 10 min).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have demonstrated that NO released from NOCys or SNP can directly increase BKCa channel openings in excised inside-out membrane patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci (Fig. 3), confirming recent observations in single myocytes of the circular muscle of the guinea-pig proximal colon (Lang & Watson, 1998) and the rat mesenteric artery (Mistry & Garland, 1998). In addition, we have demonstrated that sulfhydryl reducing agents mimic the effects of NO, while oxidation or alkylation of free thiol groups have the opposite effect, suggesting that BKCa channels in excised membrane patches must exist in a mixed redox state. Alkylation of free thiols with NEM also prevented the actions of NOCys, indicating that a chemical modification of intracellular sulfhydryl groups (S-nitrosation or nitrothiosylation) on the BKCa channel is likely to be involved.

Effects of redox agents

Redox reagents have been reported to have variable effects on smooth muscle BKCa channels in both excised inside-out patches (Wang et al. 1997; Lang & Watson, 1998) and after fusion into artificial lipid bilayers (Abderrahmane et al. 1998). As isolation and incubation conditions vary between experimental laboratories, BKCa channels may well not be in the same redox state in all experiments. Although they are presumably more oxidized than when they are within the cell membrane and exposed to a relatively reduced cellular environment (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997). Such differing conditions may well explain, in part, some of the varying results reported to date. BKCa channel activity in excised patches from myocytes of the small (< 300 μm) pulmonary artery of the rabbit are sensitive to oxidizing agents (oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and NAD) or their reduced forms GSH and NADH (Lee et al. 1994; Park et al. 1995). In contrast, myocytes obtained from the large (> 300 μm) pulmonary arteries (Thuringer & Findlay, 1997) and the ear artery (Park et al. 1995) of the rabbit are little affected. In excised membranes of horse trachea (Wang et al. 1997) and the guinea-pig taenia caeci (Fig. 6), DTT (10-1000 μM) and GSH (1 mM) readily increase NPo, while NEM (1 mM), thimerosal and 4,4DTDP (all 10 μM) decrease NPo. On the other hand, DTT, GSH and NEM (all at 5 mM) increase the gating of bovine airway BKCa channels incorporated into lipid bilayers (Abderrahmane et al. 1997). Finally, it is interesting to note that DTT (1 mM) readily increases the activity of BKCa channels cloned from human brain (hslo), expressed in either immortal cell lines or Xenopus oocytes, but not that of BKCa channels cloned from Drosophila (dslo) (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997).

Effects of NO

Both the nature of the applied NO donor and the redox state of the BKCa channel proteins appear to influence the observed effects of various NO donors on channel gating. Directly applied NO or the rapidly degrading NOCys increase (within 1–5 min) NPo in the guinea-pig taenia caeci (Fig. 3), proximal colon (Lang & Watson, 1998) and rat mesenteric artery (Mistry & Garland, 1998). In contrast, the slow-release NO donors SNP and 3-morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1) or S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine (SNAP) have more variable affects. For example, SNP (100 μM) slowly increases NPo in excised patches of the guinea-pig taenia caeci (Fig. 6Ac) and proximal colon (Lang & Watson, 1998), but not when patches remained cell-attached. In excised patches of the rat mesenteric artery, SNP and SIN-1 (100-200 μM) increased BKCa channel activity in < 50 % of patches examined (Mistry & Garland, 1998). In contrast, SNAP had little effect on BKCa channel gating in excised inside-out patches pulled either from myocytes of the dog proximal colon (Koh et al. 1995) or after molecular isolation from the human aorta (hslo1.1) and expression in Xenopus oocytes (McCobb et al. 1995). NO donors such as SNP and SIN-1 also release other byproducts (e.g. heavy metals and superoxides) which may well react with each other and/or thiol groups to modulate BKCa channel activity. However, the excitatory effects of NO donors are little altered in the presence of superoxide dismutase, potassium urate (a peroxinitrite scavenger), EDTA (Abderrahmane et al. 1997) or EGTA (Fig. 3), which would chelate any heavy metals present.

NOCys-induced increases in NPo were relatively transient in nature. The mean values of V0.5 and K obtained from the steady state estimates of NPo at various membrane potentials in NOCys (10 μM) were therefore not significantly different from control. At face value, the NO-induced increases in NPo (at 0 mV; Fig. 3) would therefore have to be interpreted as arising purely from an increase in N, the number of active channels. However, when ramped depolarisations (-100 to +100 mV) were used to monitor BKCa channel activity, there was an appreciable increase in BKCa channel activity at negative potentials in the presence of NOCys (Fig. 3C a and B) or SNP. This increase in channel activity at negative ramp potentials was not as great as that seen with a 10-fold increase (from 15 to 150 nM Ca2+) in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (data not shown), which we established involved an 11 mV shift in the negative direction of the plots of ln(NPo) vs. V (Fig. 2Cb; Benham et al. 1986; Singer & Walsh, 1987). Thus, it is likely that a negative shift (perhaps < 10 mV in 10 μM NOCys) in the activation curves, with little change in the voltage-sensing properties of the BKCa channels underlies, in part, the NOCys-induced increases in NPo (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997; Lang & Watson, 1998). A similar negative shift of the NPovs. V relationship has been suggested to occur upon reduction of the BKCa channel protein with β-mercaptoethanol (Wang et al. 1997).

In the present experiments, the previously reported blockade of BKCa channel amplitudes in cell-attached patches of the guinea-pig proximal colon and in excised patches of rat mesenteric artery (with 500 μM SIN-1; Mistry & Garland, 1998) was not evident. In the guinea-pig colonic myocytes, we suggested that the NO-induced blockade of BKCa channels arose from a rise in the internal Na+ due to the opening of small conductance cationic channels (Lang & Watson, 1998). Similar small cationic-selective single channel openings were evident in excised patches of the taenia caeci after the application of either NOCys or DTT (data not shown). The nature of these cationic channels has yet to be elucidated.

Site of NO action

Many nucleophilic centres of cell proteins can undergo nitrosation; however, nitrothiosylation occurs most preferentially at exposed thiol (RSH) groups (Gaston, 1999). Moreover, these S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) can be unstable, readily reverting to thiol groups or to a disulfide bond if neighbouring thiols are also reduced (Stamler et al. 1992). The effects of NOCys (Fig. 7), diamide and thimerosal (Wang et al. 1997) were blocked by NEM, establishing that the major site for the formation or rupture of disulfide bonds between vicinal thiols was likely to be on cysteine residues. Even though there are considerable differences in the gating kinetics and voltage/Ca2+ sensitivities of BKCa channels between tissues (particularly smooth muscle) and species, the channel appears to be encoded by a single gene (slo). It comprises: (i) an α subunit, which contains seven membrane-spanning domains (S0-S6), six of which are relatively homologous to KV channels, a separate pore region (S5-S6) and a long COOH terminus ‘tail’ (S7-S10) involved in Ca2+ activation and modulation by kinase phosphorylation; and (ii) a β subunit, involved in modulation of the Ca2+ sensitivity and iberiotoxin binding (Tanaka et al. 1997). Given that the slo protein contains a large number of cysteine residues (27 and 29 in hslo and hslo1.1, respectively; DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997), largely concentrated on the COOH terminus of the α subunit, it is not yet clear which reactive residue/s are available for NO or redox modulation. However, it is unlikely that the reactive cysteine groups are on the extracellular surface, within the pore of the BKCa channel, or involved in Ca2+ binding for the following reasons: (i) neither the application of NO, nor the oxidation/reduction or alkylation of the BKCa channel complex has any affect on the unit conductance of the BKCa channels recorded in excised patches (Figs 3A, 4A–C and 5Aa and Ba); (ii) thimerosal and GSH, which are membrane-impermeant, were only effective when applied to the cytosolic surface of excised membrane patches (data not shown; Wang et al. 1997), and (iii) the application of NEM or DDT did not prevent the excitatory effects of raising the Ca2+ concentration on the trans side of BKCa channels in lipid bilayers (Abderrahmane et al. 1997). An investigation of the effects of NO on dsloBKCa channels would be timely, as dslo channels are not modulated by redox agents, presumably because compared with hslo channels nine cysteine groups are not conserved (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1997).

In summary, it is clear that NO modulation of thiol groups may well constitute a physiologically relevant control mechanism of BKCa channel function in smooth muscle. This modulation presumably arises from the number of reactive thiol residues in the appropriate alignment, the redox state of the cell and the amount of endogenously released NO (Simon et al. 1996; Gaston, 1999). In the dog colon, NO donors have also been shown to activate two additional K+ channels, KNO1 and KNO2 which have unit conductances of 80 pS and < 4 pS, respectively (Koh et al. 1995). Both DTT (2 mM) and NEM (5 mM) prevented the activation of these channels by NO; however, it was not reported whether these thiol reagents affected channel gating directly. Moreover, many other K+-, Ca2+- and cationic-selective channels and receptors (e.g. intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, KATP channels, GABAA receptors, ryanodine receptors) have also been reported to be modulated by either NO and/or thiol reagents (Coetzee et al. 1995; Campbell et al. 1996; Cai & Sauve, 1997; Eager & Dulhunty, 1999; Herson & Ashford, 1999). It may well be that studies of the physiological role of smooth muscle BKCa channels, such as, for example, their contribution to the membrane potential or their modulation by kinases and phosphatases, would be better conducted using cell-attached patches or excised membrane patches and lipid bilayers bathed in a reduced cytosolic environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part, by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- Abderrahmane A, Salvail D, Dumoulin M, Garon J, Cadieux A, Rousseau E. Direct activation of KCa channel in airway smooth muscle by nitric oxide: involvement of a nitrothiosylation mechanism? American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1998;19:485–497. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.3.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayguinov O, Sanders KM. Role of nitric oxide as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the canine pyloric sphincter. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:G975–983. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.5.G975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayguinov O, Vogalis F, Morris B, Sanders KM. Patterns of electrical activity and neural responses in canine proximal duodenum. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:G887–894. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.6.G887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Bolton TB, Lang RJ, Takewaki T. Calcium-activated potassium channels in single smooth muscle cells of rabbit jejunum and guinea-pig mesenteric artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;371:45–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatz AL, Magelby KL. Single apamin-blocked Ca-activated K+ channels of small conductance in rat cultured skeletal muscle. Nature. 1986;323:718–720. doi: 10.1038/323718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotina VM, Najibi S, Palacino JJ, Pagano PJ, Cohen RA. Nitric oxide directly activates calcium-dependent channels in vascular smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;368:850–853. doi: 10.1038/368850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Sauve R. Effects of thiol-modifying agents on a KCa2+ channel of intermediate conductance in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;158:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s002329900252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Stamler JS, Strauss HC. Redox modulation of L-type calcium channels in ferret ventricular myocytes. Dual mechanism regulation by nitric oxide and S-nitrosothiols. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:277–293. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayabyab FS, Daniel EE. K+ channel opening mediates hyperpolarizations by nitric oxide donors and IJPs in opossum esophagus. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:G831–842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.5.G831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Nakamura TY, Faivre JF. Effects of thiol-modifying agents on KATP channels in guinea pig ventricular cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H1625–1633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiChiara TJ, Reinhart PH. Redox modulation of hslo Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:4942–4955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-04942.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eager KR, Dulhunty AF. Cardiac ryanodine receptor activity is altered by oxidizing reagents in either the luminal or cytoplasmic solution. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1999;167:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s002329900484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston B. Nitric oxide and thiol groups. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1411:323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetter CA, Kadowitz PJ, Ignarro LJ. Methylene blue inhibits coronary arterial relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by nitroglycerin, sodium nitrate and amyl nitrate. Canadian The Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1981;59:150–156. doi: 10.1139/y81-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JR, Lang RJ. Effects of nitric oxide and sulfhydryl reagents on Ca2+-activated K+ and cationic channels in myocytes of the guinea-pig taenia caeci. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 1998;10:75. [Google Scholar]

- Herson PS, Ashford ML. Reduced glutathione inhibits β-NAD+-activated non-selective cationic currents in the CRI-G1 rat insulin-secreting cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.047af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keef KD, Du C, Ward SM, McGregor B, Sanders KM. Enteric inhibitory neural regulation of human colonic circular muscle: role of nitric oxide. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K, Lian Q, Carl A, Kuriyama H. S-nitrosocysteine, but not sodium nitroprusside, produces apamin-sensitive hyperpolarization in rat gastric fundus. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109:415–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Campbell JD, Carl A, Sanders KM. Nitric oxide activates multiple potassium channels in canine colonic smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:735–743. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto A, Nedergaard J. Modulation of calcium-activated non-selective cation channel activity by nitric oxide in rat brown adipose tissue. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:59–65. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RJ, Ozolins IZ, Paul RJ. Effects of okadaic acid and ATPγS on cell length and Ca2+-channel currents recorded in single smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig taenia caeci. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;104:331–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RJ, Watson MJ. Effects of nitric oxide donors, S-nitroso-L-cysteine and sodium nitroprusside, on the whole-cell and single channel currents in single myocytes of the guinea-pig proximal colon. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;123:505–517. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Park M, So I, Earm YE. NADH and NAD modulates Ca2+-activated K+ channels in small pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;427:378–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00374548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCobb DP, Fowler NL, Featherstone T, Lingle CJ, Saito M, Krause JE, Salkoff L. A human calcium-activated potassium channel gene expressed in vascular smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H767–777. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee GJ, Lang RJ. Effects of nitric oxide donors, nitrosocysteine and sodium nitroprusside, on the activity of the Ca2+-activated K+ (‘B-K’) channels in the guinea-pig taenia caeci. Proceedings of the Australian Physiology and Pharmacology Society. 1994;25:214P. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry DK, Garland CJ. Nitric oxide (NO)-induced activation of large conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (BKCa) in smooth muscle cells isolated from the rat mesenteric artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;124:1131–1140. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JA, Shibata EF, Buresh TL, Picken H, O'Meara BW, Conklin JL. Nitric oxide modulates a calcium-activated potassium current in muscle cells from opossum esophagus. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:G606–612. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.4.G606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MK, Lee SH, Lee SJ, Ho WK, Earm YE. Different modulation of Ca-activated K channels by the intracellular redox potential in pulmonary and ear arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;430:308–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00373904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemidis S, Satchell DG, Cocks TM. Evidence that NO acts as a redundant NANC inhibitory neurotransmitter in the guinea-pig isolated taenia coli. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;121:604–611. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DI, Mullins ME, Jia L, Gaston B, Singel DJ, Stamler JS. Polynitrosylated proteins: characterization, bioactivity, and functional consequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JJ, Walsh JV., Jr Characterization of calcium-activated potassium channels in single smooth muscle cells using the patch-clamp technique. Pflügers Archiv. 1987;408:98–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00581337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. S-nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:444–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Meera P, Song M, Knaus HG, Toro L. Molecular constituents of maxi-KCa channels in human coronary smooth muscle: predominant alpha + beta subunit complexes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:545–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.545bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuringer D, Findlay I. Contrasting effects of intracellular redox couples on the regulation of maxi-K channels in isolated myocytes from rabbit pulmonary artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:583–592. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZW, Nara M, Wang Y-X, Kotlikoff MI. Redox regulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in smooth muscle cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:35–44. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Dalziel HH, Bradley ME, Buxton ILO, Keef K, Westfall DP, Sanders KM. Involvement of cyclic GMP in non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic inhibitory neurotransmission in dog proximal colon. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992a;107:1075–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb13409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, McKeen ES, Sanders KM. Role of nitric oxide in non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic inhibitory junction potentials in canine ileocolonic sphincter. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992b;105:776–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M, Lang RJ, Bywater RAR, Taylor GS. Characterization of the conductance changes underlying the apamin-resistant NANC inhibitory junction potential in the guinea-pig proximal and distal colon. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1996;60:31–42. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(96)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Vogalis F, Goyal RK. Nitric oxide suppresses a Ca2+-stimulated Cl− current in smooth muscle cells of opossum esophagus. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:G886–890. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.5.G886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]