Abstract

In the mammalian heart, Ca2+-independent, depolarization-activated potassium (K+) currents contribute importantly to shaping the waveforms of action potentials, and several distinct types of voltage-gated K+ currents that subserve this role have been characterized. In most cardiac cells, transient outward currents, Ito,f and/or Ito,s, and several components of delayed reactivation, including IKr, IKs, IKur and IK,slow, are expressed. Nevertheless, there are species, as well as cell-type and regional, differences in the expression patterns of these currents, and these differences are manifested as variations in action potential waveforms. A large number of voltage-gated K+ channel pore-forming (α) and accessory (β, minK, MiRP) subunits have been cloned from or shown to be expressed in heart, and a variety of experimental approaches are being exploited in vitro and in vivo to define the relationship(s) between these subunits and functional voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels. Considerable progress has been made in defining these relationships recently, and it is now clear that distinct molecular entities underlie the various electrophysiologically distinct repolarizing K+ currents (i.e. Ito,f, Ito,s, IKr, IKs, IKur, IK,slow, etc.) in myocyardial cells.

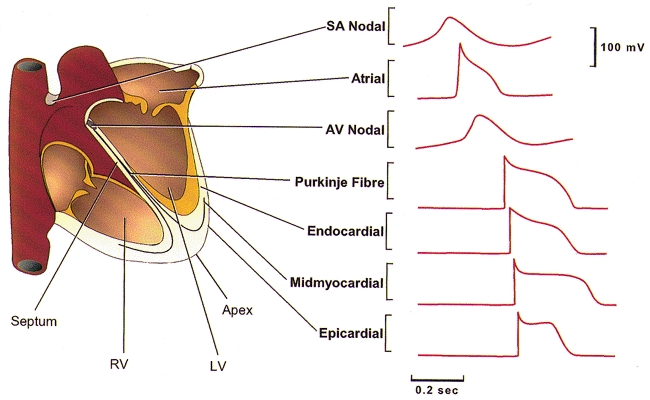

The amplitudes and the durations of action potentials in the mammalian myocardium (Fig. 1) are largely determined by voltage-gated K+ channels and, in most cardiac cells, two broad classes of voltage-gated K+ channel currents have been distinguished based primarily on differences in time- and voltage-dependent properties: (1) rapidly activating and inactivating, transient outward K+ currents, Ito; and (2) slowly inactivating, outwardly rectifying K+ currents, IK (Campbell et al. 1995; Barry & Nerbonne, 1996; Giles et al. 1996; Nerbonne, 1998; Snyders, 1999) (Table 1). These currents serve distinct roles in action potential repolarization: the transient currents (Ito), which activate and inactivate relatively rapidly, for example, underlie the early phase of action potential repolarization (Fig. 1), whereas the delayed rectifiers (IK), which activate with variable rates and typically inactivate slowly, contribute to the later phase of membrane repolarization, back to the resting potential (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, these (Ito and IK) are broad classifications, and there are multiple components of Ito and IK (Table 1) in cardiac cells, with distinct properties and functional roles. In addition, there are differences in the expression patterns of the various voltage-gated K+ currents (Table 1) in cardiac cells isolated from different species, as well as in cells from different regions of the heart in the same species (Antzelevitch et al. 1994; Barry & Nerbonne, 1996), and these distinct K+ current expression patterns contribute to regional differences in action potential waveforms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Action potential waveforms are variable in different regions of the heart.

Schematic representation of the heart; action potential waveforms recorded in different regions of the heart are illustrated. Action potentials are displaced in time to reflect the temporal sequence of propagation through the heart. SA, sino-atrial; AV, atrio-ventricular; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

Table 1. Voltagegated K+ currents/channels in the mammalian heart.

| Current | Activation | Inactivation | Blocker | Tissue* | Species* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito | |||||

| Ito,f | Fast | Fast | Millimolar 4AP | Atrium | Dog, human, mouse, rat |

| Flecainide | Ventricle | Cat, dog, ferret, human, mouse, rat | |||

| HaTX | |||||

| HpTX | |||||

| Ito,s | Fast | Slow | Millimolar 4AP | Atrium | Rabbit |

| Ventricle | Ferret, human, mouse, rabbit, rat | ||||

| Node | Rabbit | ||||

| IK | |||||

| IKr | Moderate | Fast | E4031 | Atrium | Dog, guinea-pig, human, rat |

| Dofetilide | Ventricle | Cat, dog, guineapig, human, mouse, rabbit, rat | |||

| Lanthanum | Node | Rabbit | |||

| IKs | Very slow | No | NE10064 | Atrium | Dog, guinea-pig, human |

| NE10133 | Ventricle | Dog, guinea-pig, human | |||

| Node | Guinea-pig, rabbit | ||||

| IKur | Fast | No | Micromolar 4-AP | Atrium | Dog, human, rat |

| IKp | Fast | No | Ba2+ | Ventricle | Guinea-pig |

| IK | Slow | Slow | Millimolar TEA | Ventricle | Rat |

| IK,slow | Fast | Slow | Micromolar 4-AP | Atrium | Mouse |

| Millimolar TEA | Ventricle | Mouse | |||

| IK,slow | Fast | Very slow | Millimolar 4-AP | Atrium | Human, rat |

| (IK,DTX) | DTX | ||||

| Iss | Slow | No | Millimolar TEA | Atrium | Mouse, rat |

| Millimolar 4-AP | Ventricle | Dog, human, mouse, rat | |||

Currents with these properties have been identified in these tissues/species to date. 4-AP, 4-aminopyridine; HaTX, hanatoxin; HpTX, heteropodatoxin; TEA, tetraethylammonium; DTX, dendrotoxin.

In spite of the marked electrophysiological diversity of repolarizing K+ currents, the time- and voltage-dependent properties of the various Ito and IK currents (Table 1) in different cardiac cell types (and species) are quite similar, observations interpreted as suggesting that the molecular correlates of the underlying K+ channels are also the same (Barry & Nerbonne, 1996). A number of voltage-gated K+ channel (Kv) pore-forming (α) and accessory (β, minK and MiRP) subunits have now been cloned from or shown to be expressed in heart, and the molecular diversity of Kv channel subunits is even greater than expected (Table 2) based on the recognized electrophysiological heterogeneity of these channels (Table 1). Nevertheless, considerable progress has been made recently in defining the relationships between these subunits and the functional voltage-gated K+ currents/channels in cardiac cells. Importantly, the results obtained to date suggest that distinct molecular entities underlie the various electrophysiologically distinct types of voltage-gated K+ currents/channels in myocardial cells (Table 2).

Table 2. Kvα subunits: relation to functional voltage-gated cardiac K+ currents.

| Family | Subunit | Activation* | Inactivation* | Blocker* | Endogenous current |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kv1 (Shaker) | Kv1.1 | ||||

| Kv1.2† | Fast | Slow | 4AP | IK,slow (rat) | |

| DTX | (IK,DTX) | ||||

| Kv1.3 | |||||

| Kv1.4† | Fast | Slow | 4-AP | Ito,s | |

| Kv1.5† | Fast | Slow | 4AP | IKur | |

| IK,slow (mouse) | |||||

| Kv1.6 | |||||

| Kv1.7† | Fast | Fast | NTX | ? | |

| Kv1.8 | |||||

| Kv2 (Shab) | Kv2.1† | Slow | Very slow | TEA, HaTx | IK,slow (mouse) |

| Kv2.2† | Slow | Very slow | TEA | ? | |

| Kv3 (Shaw) | Kv3.1† | Fast | Slow | TEA | ? |

| Kv3.2 | |||||

| Kv3.3 | |||||

| Kv3.4 | |||||

| Kv4 (Shal) | Kv4.1 | ||||

| Kv4.2† | Fast | Fast | 4-AP, HaTx, HpTx | Ito,f | |

| Kv4.3† | Fast | Fast | 4-AP,HpTx | Ito,f | |

| Kv5–9 | |||||

| eag family | |||||

| eag | eag | ||||

| elk | elk | ||||

| erg | erg1† | Moderate | Fast | E4031 | IKr (with MiRP) |

| erg2 | |||||

| erg3 | |||||

| KvLQT1 family | |||||

| KCNQ1 | KvLQT1† | Very slow | Very, very slow | NE10064 | IKs (with minK) |

| KCNQ2 | |||||

| KCNQ3 |

Properties determined for heterologously expressed subunits; detailed properties, however, do vary with expression system (see text).

Subunit expressed in mammalian myocardium. DTX, dendrotoxin; NTX, noxiustoxin; HaTX, hanatoxin; HpTX, heteropodatoxin.

Transient outward K+ current (Ito) diversity in cardiac cells

Although two transient outward current components, referred to as Ito1 and Ito2, were originally identified in cardiac cells (Kenyon & Gibbons, 1979a,b; Coraboeuf & Carmeliet, 1982), only Ito1 is a K+ current; Ito2 is a Cl−-selective, not a K+-selective, conductance pathway (Kenyon & Gibbons, 1979a,b; Zygmunt & Gibbons, 1991) and is not discussed further here. The Ca2+-independent, depolarization-activated outward K+ currents in cardiac cells have been referred to previously as Ito, Ito1 or It (Campbell et al. 1995; Giles et al. 1996; Barry & Nerbonne, 1996). Although initially assumed to reflect the same underlying K+ channel(s), it has now been clearly demonstrated that there are (at least) two distinct transient outward K+ currents, Ito,fast (Ito,f) and Ito,slow (Ito,s), and that these currents are differentially distributed (Brahmajothi et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999; Wickenden et al. 1999a,b,c; Xu et al. 1999b).

The very rapidly inactivating, transient outward current in cardiac cells is now referred to as Ito,fast or Ito,f (Table 1) after Xu et al. (1999b). Currents that can be classified as Ito,f have been characterized in considerable detail in cat (Furukawa et al. 1990), dog (Litovsky & Antzelevitch, 1988; Tseng & Hoffman, 1989), ferret (Campbell et al. 1993), human (Wettwer et al. 1993, 1994; Konarzewska et al. 1995; Amos et al. 1996; Näbauer et al. 1996, 1998), mouse (Xu et al. 1999b) and rat (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991; Himmel et al. 1999; Wickenden et al. 1999a,c) ventricular myocytes (Table 1), as well as in atrial cells from dog (Yue et al. 1996a), rat (Boyle & Nerbonne, 1991, 1992), human (Escande et al. 1987; Shibata et al. 1989; Fermini et al. 1992; Amos et al. 1996) and mouse (Xu et al. 1999c; E. Bou-Abboud, H. Li & J. M. Nerbonne, unpublished observations) (Table 1). Although guinea-pig ventricular myocytes reportedly lack Ito,f (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990, 1991), a rapidly activating and inactivating (Ito,f-like) outward K+ current is detectable in these cells when extracellular Ca2+ is removed (Inoue & Imanaga, 1993), suggesting that functional Ito,f expression may be highly regulated.

The time- and voltage-dependent properties of the currents classified as Ito,f in different cardiac cell types (Table 1) are similar in that activation, inactivation and recovery from steady-state inactivation are all rapid; the pharmacological properties of the currents are also similar (Table 1). The rapid rate of recovery of Ito,f from steady-state inactivation (τ≈ 30–50 ms) has been exploited to distinguish Ito,f and Ito,s (Brahmajothi et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999; Xu et al. 1999b). It has also been demonstrated that Ito,f in rat (Sanguinetti et al. 1997), ferret (Brahmajothi et al. 1999) and mouse (Xu et al. 1999b) ventricular myocytes is selectively attenuated by heteropodatoxin-2 and −3. The fact that the properties of Ito,f in different cardiac cells are similar (Table 1) led to the suggestion that the molecular correlates of functional Ito,f channels in different cell types and/or species are also the same (Barry & Nerbonne, 1996), and considerable experimental support for this hypothesis has now been provided (see below). Nevertheless, there are some subtle differences in the properties of the currents referred to as Ito,f (Table 1). Comparison of rat atrial and ventricular Ito,f, for example, reveals significant differences in rates of inactivation and recovery (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991; Boyle & Nerbonne, 1992).

In contrast to Ito,f, the rate of inactivation and recovery of the transient outward currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular myocytes is slow (Giles & Imaizumi, 1988; Clark et al. 1988; Hiraoka & Kawano, 1989; Fedida & Giles, 1991; Giles et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1999). In mouse ventricular myocytes, a slowly inactivating transient K+ current has also been identified and is referred to as Ito,slow or Ito,s (Xu et al. 1999b). Mouse ventricular Ito,s recovers from steady-state inactivation (τrecovery≈ 1 s) much more slowly than Ito,f (τrecovery≈ 50 ms) and is insensitive to the heteropodatoxins (Xu et al. 1999b). The properties of Ito (It) in rabbit myocytes are similar to those of mouse ventricular Ito,s, suggesting that the transient currents in rabbit should also be termed Ito,s (Table 1). The rates of inactivation and recovery of the transient outward K+ currents are significantly slower in endocardial than in epicardial cells isolated from ferret left ventricles, suggesting that distinct K+ channel α subunits also underlie the transient currents in these cells (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). The time- and voltage-dependent properties and the pharmacological sensitivities of the currents in ferret epicardial and endocardial left ventricular myocytes are similar to those of the mouse ventricular currents, and these currents are also now referred to as Ito,f and Ito,s, respectively (Table 1). There are also distinct transient outward K+ currents in human and in rat ventricular myocytes (Näbauer et al. 1996, 1998; Wickenden et al. 1999a,c) with properties similar to those of mouse and ferret Ito,f anf Ito,s (Table 1).

Delayed rectifier K+ current (IK) diversity in cardiac cells

In most cardiac cells, multiple components of IK are evident (Table 1). The detailed properties of the delayed rectifier K+ currents have been characterized in myocytes isolated from canine (Tseng & Hoffman, 1989; Liu & Antzelevitch, 1995; Yue et al. 1996a,a), feline (Furakawa et al. 1992), guinea-pig (Balser et al. 1990; Horie et al. 1990; Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990, 1991; Walsh et al. 1991; Anumonwo et al. 1992; Freeman & Kass, 1993), human (Wang et al. 1994; Li et al. 1996), mouse (Fiset et al. 1997a; London et al. 1998a; Zhou et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999b,c; Guo et al. 1999), rabbit (Veldkamp et al. 1993) and rat (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991; Boyle & Nerbonne, 1992) heart. Two prominent components of IK, referred to as IKr (IK,rapid) and IKs (IK,slow) for example, have been distinguished in guinea-pig atrial and ventricular myocytes. IKr activates and inactivates rapidly, displays marked inward rectification, and is selectively blocked by lanthanum and by several class III anti-arrhythmics, including dofetilide, E-4031 and sotalol (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990, 1991). IKr and IKs can also be distinguished at the microscopic level: in symmetrical K+, the single channel conductances of IKr and IKs channels are10–13 and 3–5 pS, respectively (Balser et al. 1990; Veldkamp et al. 1993). Similar currents have been described in atrial and ventricular myocytes isolated from human (Wang et al. 1993a, 1994; Li et al. 1996) and canine (Liu & Antzelevitch, 1995; Yue et al. 1996a) hearts, and in rabbit ventricular cells (Veldkamp et al. 1993; Salata et al. 1996).

In rat (Boyle & Nerbonne, 1991, 1992), human (Wang et al. 1993a,b) and dog (Yue et al. 1996a,b) atrial myocytes, rapidly activating, non-inactivating K+ currents (distinct from IKr and IKs) have been identified and referred to as Iss (steady-state), Isus (sustained) or IKur (ultra-rapid). Because the properties of the currents are similar and recent studies suggest that the molecular correlates of the rat and human currents are the same (Feng et al. 1997; Bou-Abboud & Nerbonne, 1999), all are now referred to as IKur (Table 1). In guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, a 12–14 pS K+-selective channel, distinct from IKr, has also been reported and referred to as IKp (Yue & Marban, 1988). IKp activates rapidly on depolarization, does not inactivate and is sensitive to millimolar concentrations of Ba2+ (Backx & Marban, 1993). The properties of this current are very similar to that of dog, human and rat IKur, suggesting that IKp probably also reflects the expression of IKur.

In some cardiac cell types, there are additional components of IK with properties different from IKs, IKr and IKur (Table 1). In mouse ventricular and atrial myocytes, for example, two voltage-gated K+ currents have been identified and are referred to as IK,slow and Iss (Fiset et al. 1997a; London et al. 1998a; Zhou et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999b,c; Guo et al. 1999; E. Bou-Abboud, H. Li & J. M. Nerbonne, unpublished observations). In spite of the terminology, IK,slow, which is rapidly activating and slowly inactivating and is blocked selectively by micromolar concentrations of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), is distinct from IKs (Fiset et al. 1997a; London et al. 1998a; Zhou et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999b). The current remaining at the end of long depolarizing voltage steps, Iss, is slowly activating and, although 4-AP insensitive, is blocked by tetraethylammonium (TEA) (Xu et al. 1999a,b). In rat ventricular and atrial myocytes, there are also novel delayed rectifier K+ currents, referred to as IK and IK,slow, respectively (Table 1) (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991; Boyle & Nerbonne, 1991, 1992). In addition to differences in inactivation, IK and IK,slow can be distinguished pharmacologically: IK is blocked selectively by TEA (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991), whereas IK,slow is blocked by millimolar concentrations of 4-AP (Boyle & Nerbonne, 1991, 1992) and by nanomolar concentrations of the dendrotoxins (Van Wagoner et al. 1996). For this reason, rat atrial IK,slow is now referred to as IK,DTX (Table 1).

Regional differences in voltage-gated K+ channel expression

In some species, there are marked differences in the densities of the K+ currents expressed in different myocardial cell types. In rat, for example, Ito,f density is higher in atrial than in ventricular myocytes (Boyle & Nerbonne, 1991, 1992), whereas in mouse, Ito,f density is higher in ventricular than in atrial cells (Xu et al. 1999c). The density of Ito,f also varies in different regions of the ventricles in canine (Litovsky & Antzelevitch, 1988; Liu et al. 1993), cat (Furukawa et al. 1992), ferret (Brahmajothi et al. 1999), human (Wettwer et al. 1994; Näbauer et al. 1996, 1998), mouse (Xu et al. 1999b; Guo et al. 1999) and rat (Clark et al. 1993; Wickenden et al. 1999a) heart. In canine left ventricles, for example, Ito,f density is 5- to 6-fold higher in epicardial and midmyocardial than in endocardial cells (Liu et al. 1993). Ito,f density is also reportedly higher in guinea-pig atrial epicardium than endocardium (Wang et al. 1991). Ito,s density is significantly higher in rabbit atrial than ventricular myocytes (Giles & Imaizumi, 1988), and the density of Ito,s varies markedly in ferret left ventricular myocytes (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). In mouse ventricles, Ito,f and Ito,s are also differentially distributed (Xu et al. 1999b; Guo et al. 1999): in cells isolated from the right ventricle or the apex of the left ventricle, only Ito,f is present, whereas cells isolated from the left ventricular septum express either Ito,s alone (∼20 % of the cells) or both Ito,f and Ito,s (∼80 % of the cells) (Xu et al. 1999b). In addition, when expressed, Ito,f density is significantly higher in apex than in septum cells (Xu et al. 1999b).

The densities of IKs and IKr in different myocardial cell types are also variable. In guinea-pig, for example, IKr and IKs densities are 2-fold higher in atrial than in ventricular myocytes (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1991). In dog heart, IKs density is higher in epicardial and endocardial cells than in midmyocardial cells (Liu & Antzelevitch, 1995). There are also regional differences in IKr and IKs expression in guinea-pig left ventricle (Bryant et al. 1998; Main et al. 1998). In cells isolated from the guinea-pig left ventricular free wall, for example, the density of IKr is reportedly higher in subepicardial than in midmyocardial or subendocardial myocytes (Main et al. 1998), whereas at the base, the densities of IKr and IKs are lower in endocardial than in midmyocardial or epicardial cells. It seems certain that differences in voltage-gated K+ current densities contribute to the variations in action potential waveforms recorded in atrial and ventricular myocytes, as well as in cells isolated from different regions (apex versus base) and layers (epicardial, midmyocardial and endocardial) of the atria and ventricles (Fig. 1).

Molecular diversity of voltage-gated K+ channel pore-forming α subunits

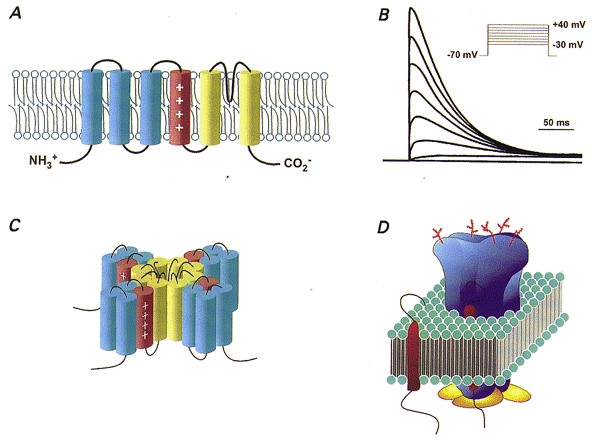

The first voltage-gated K+ channel (Kv) pore-forming (α) subunit was cloned from the Shaker locus in Drosophila and this was followed quickly by the cloning of three homologous Kv α subunit subfamilies, referred to as Shab (Kv2), Shaw (Kv3) and Shal (Kv4) (Butler et al. 1989; Wei et al. 1990). Each Kv α subunit protein has six membrane-spanning regions, a K+-selective pore and a highly charged S4 domain (Fig. 2A), placing the Kv α subunits in the ‘S4 superfamily’ of voltage-gated ion channels (Jan & Jan, 1992; Pongs, 1992). Further diversity results from the presence of multiple members of each subfamily (Table 2) and through alternative splicing of transcripts (Pongs, 1992; Barry & Nerbonne, 1996; Deal et al. 1996; Coetzee et al. 1999). Heterologous expression of Kv α subunit cDNAs reveals voltage-gated K+ channel currents with distinct time- and voltage-dependent properties (Fig. 2B). Because functional voltage-gated K+ channels comprise four α subunits (Fig. 2C) (MacKinnon, 1991), further diversity could arise through the formation of heteromultimeric channels between two or more Kv α subunit proteins (Covarrubias et al. 1991).

Figure 2. Structure, expression and assembly of voltage-gated K+ channel pore-forming (α) and accessory (minK and β) subunits.

A, Kv α subunits are integral membrane proteins with six transmembrane domains, intracellular N- and C-termini and a positively charged S4 region, placing them in the ‘S4 superfamily’ of voltage-gated ion channels. B, schematic representation of outward K+ current waveforms produced on heterologous expression of a Kv α subunit of the Shal subfamily, Kv4.2, which gives rise to K+ currents that activate and inactivate rapidly on membrane depolarization. C, schematic diagram of a voltage-gated K+ channel illustrating the assembly of four Kv α subunits to produce a K+-selective pore. D, schematic diagram of functional voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels with Kv α subunits depicted in blue, cytosolic β (or KChAP) subunits in yellow and minK (or MiRP1) subunits in red.

Additional Kv α subunit subfamilies, Kv5.x to Kv9.x (Table 2), have also been identified (Drewe et al. 1992; Hugnot et al. 1996; Salinas et al. 1997). Although heterologous expression of these subunits (alone) does not reveal functional voltage-gated K+ channel currents, coexpression with Kv2.x subfamily members attenuates the amplitude of the Kv2.x-induced currents (Salinas et al. 1997). These observations, together with sequence similarities to the Kv2.x subfamily suggest that Kv5.x to Kv9.x may be regulatory (Kv α) subunits of the Kv2.x subfamily (Castellano et al. 1997), rather than distinct subfamilies (Salinas et al. 1997). The role of these subfamilies in the generation of functional cardiac K+ channels is presently unclear.

Homologous subfamilies of voltage-gated K+ channel α subunit genes were revealed with the cloning of the Drosophila ether-à-go-go (eag) locus (Warmke et al. 1991) and with the identification of the eag-like gene (elk) and the eag-related gene (erg) in brain (Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994). Although the overall amino acid identity is low (10-15 %), the S4 and pore regions of the proteins encoded by these genes are homologous (Warmke et al. 1991) and the predicted membrane topologies of the proteins are similar to the Kv α subunits (Fig. 2A). erg1 is the locus of mutations leading to one form of familial long QT-syndrome, LQT2, and heterologous expression of erg1 reveals inwardly rectifying K+ currents (Sanguinetti et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1995) similar to cardiac IKr. Additional members of the erg subfamily, erg2 and erg3, have also been identified (Table 2), although these are not expressed in heart (Shi et al. 1997). Another subfamily of voltage-gated K+ channel α subunits was identified with the cloning of KvLQT1, the locus of mutations in LQT1. Heterologous expression of KvLQT1 produces rapidly activating K+ currents, whereas coexpression of KvLQT1 with minK (see below) produces slowly activating K+ currents that resemble cardiac IKs (Barhanin et al. 1996; Sanguinetti et al. 1996). Additional members of the KvLQT (KCNQ) subfamily, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3, have been cloned from brain and identified as loci of mutations that lead to benign familial neonatal convulsions (Biervert et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998; Schroeder et al. 1998). Expression of KCNQ2 or KCNQ3 in Xenopus oocytes produces K+-selective currents that deactivate very slowly on membrane repolarization, and it has been suggested that KCNQ2-KCNQ3 heteromultimers underlie neuronal M currents (Wang et al. 1998). Neither KCNQ2 nor KCNQ3, however, appears to be expressed in the heart (Schroeder et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998).

Accessory subunits of voltage-gated K+ channels

Further K+ channel diversity arises through the association of accessory subunits, such as minK, with the pore-forming K+ channel α subunits. Although heterologous expression of minK, which is a single transmembrane protein, in Xenopus oocytes was shown to result in voltage-gated K+ currents (Murai et al. 1989; Folander et al. 1990; Goldstein & Miller, 1991), subsequent studies revealed that these K+ currents arise from coassembly of minK with the Xenopus homologue of KvLQT1 (Sanguinetti et al. 1996); minK does not, by itself, form functional voltage-gated K+ channels. Rather, minK coassembles with KvLQT1 (Fig. 2D) to form K+ channels similar to cardiac IKs (Barhanin et al. 1996; Sanguinetti et al. 1996).

Another type of voltage-gated K+ channel accessory subunit was revealed with the molecular cloning of low molecular mass (∼45 kDa) accessory β subunits (β1 and β2) from brain (Rettig et al. 1994). Homologous Kv β subunits, Kv β1, Kv β2 and Kv β3, and alternatively spliced transcripts of Kv β1.x, have also been identified (Castellino et al. 1995; England et al. 1995; Majumder et al. 1995; Morales et al. 1995; Deal et al. 1996). These β subunits are cytosolic proteins that interact with the intracellular domains of Kv α subunits in assembled voltage-gated K+ channels (Fig. 2D). In heterologous expression systems, coassembly with β subunits can affect the time- and voltage-dependent properties of Kv α subunit-induced currents (Castellino et al. 1995; England et al. 1995; Majumder et al. 1995; Morales et al. 1995; Accili et al. 1997), as well as the functional expression of voltage-gated K+ channels on the cell surface (Shi et al. 1996; Accili et al. 1997). Another Kv β subunit, Kv β4, increases the functional expression of Kv2.x channels (Fink et al. 1996). Although Kv β4 is not expressed in heart (Fink et al. 1996), there certainly may be Kv β subunits in heart that interact selectively with Kv2.x subfamily members. Because heterologous coexpression studies suggest that the effects of the Kv β subunits are subfamily specific (Fink et al. 1996; Nakahira et al. 1996; Sewing et al. 1996), there are likely also to be β subunits that associate with the Kv4, as well as the erg1 and/or KCNQ, subfamilies of voltage-gated K+ channel α subunits, and further studies aimed at exploring this possibility directly are clearly warranted.

Using a yeast two-hybrid screen, another K+ channel accessory protein, KChAP, which is a 574 amino acid protein with no transmembrane domains and no homology to Kv α or β subunits or to minK, was identified (Wible et al. 1998). Coexpression of KChAP with Kv2.1 (or Kv2.2) markedly increases functional Kv2.x-induced current densities without measurably affecting the time- and/or the voltage-dependent properties of the currents (Wible et al. 1998). Yeast two-hybrid assays also revealed that KChAP interacts with the N-termini of Kv1.xα subunits, as well as with the C-termini of Kv β1.x subunits. Coexpression in Xenopus oocytes of KChAP with Kv1.5, however, has no measurable effect on the properties of Kv1.5-induced currents (Wible et al. 1998). These results suggest either that KChAP and Kv1.5 do not associate in oocytes or, alternatively, that the interaction between KChAP and Kv1.5 does not influence functional (Kv1.5) K+ channel expression. Further experiments aimed at delineating the roles of β subunits and KChAP in controlling the properties and influencing the functional expression of cardiac K+ channels will clearly be of interest.

Molecular correlates of cardiac transient outward K+ currents

Heterologous expression of the voltage-gated K+ channel α subunits Kv1.4, Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 reveals rapidly activating, 4-AP-sensitive K+ currents (Fig. 2B) that qualitatively resemble cardiac transient outward K+ currents (Tseng-Crank et al. 1990; Blair et al. 1991; Roberds & Tamkun, 1991; Tamkun et al. 1991; Dixon et al. 1996). Initially Kv1.4, either as a homomultimer (Tseng-Crank et al. 1990; Tamkun et al. 1991), or as a heteromultimer with other Kv1.x subunits (Po et al. 1993), was considered the likely correlate of the fast transient outward K+ current Ito,f (Table 1) in cardiac cells. The finding that the Kv4.2 mRNA level varies through the thickness of the ventricular wall (in rat), however, led Dixon & McKinnon (1994) to postulate that Kv4.2, rather than Kv1.4, underlies rat ventricular Ito,f. Consistent with this hypothesis, Kv4.2 protein expression in rat heart is high, whereas Kv1.4 is barely detectable (Barry et al. 1995; Xu et al. 1996). In addition, the time- and voltage-dependent properties and the pharmacological sensitivities of the currents produced on heterologous expression of Kv4 α subunits more closely resemble Ito,f than do Kv1.4-induced currents (Yeola & Snyders, 1997; Franqueza et al. 1999; Peterson & Nerbonne, 1999; Wickenden et al. 1999c).

Considerable experimental evidence has now been provided documenting a role for Kv α subunits of the Kv4 subfamily in the generation of cardiac Ito,f. Fiset et al. (1997b), for example, reported that Ito,f is attenuated in rat ventricular myocytes exposed to antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (AsODNs) targeted against Kv4.2 or Kv4.3. In experiments on rat atrial myocytes, in contrast, an AsODN targeted against Kv4.2 attenuated Ito,f, whereas a Kv4.3 AsODN was without effect (Bou-Abboud & Nerbonne, 1999). These results suggest a molecular explanation for the differences in the kinetic properties of rat atrial and ventricular Ito,f (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991; Boyle & Nerbonne, 1992), i.e. that both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 contribute to rat ventricular Ito,f, whereas only Kv4.2 contributes to rat atrial Ito,f.

Rat ventricular Ito,f density is also reduced in cells exposed to adenoviral constructs encoding a truncated Kv4.2 subunit, Kv4.2ST (Johns et al. 1997). Ito,f is also attenuated in transgenic mice expressing this mutant (Wickenden et al. 1999b). In contrast, in ventricular myocytes isolated from transgenic mice expressing a pore mutant of Kv4.2 (Kv4.2W362F) that functions as a dominant negative, Ito,f is eliminated (Barry et al. 1998). Ito,f is also undetectable in atrial myocytes from Kv4.2W362F-expressing animals (Xu et al. 1999c). Given the similarities in the properties of Ito,f in different cell types and species (Table 1), it seems reasonable to speculate that Kv4 α subunits underlie Ito,f in all cardiac cells (Table 2). In dog and human, the candidate subunit is Kv4.3 (Dixon et al. 1996), and it has been demonstrated that Ito,f in human atrial myocytes is attenuated in cells exposed to a Kv4.3 AsODN (Wang et al. 1999). Interestingly, two splice variants of Kv4.3 have been identified in human (Kong et al. 1998) as well as in rat (Takimoto et al. 1997; Ohya et al. 1997) heart. Neither the relative expression levels of the two Kv4.3 proteins nor the contribution of these subunits to the generation of functional cardiac Ito,f channels, however, has been determined.

The properties of Ito,s in rabbit atrial and ventricular myocytes are distinct from those of Ito,f and, in fact, appear similar to those of heterologously expressed Kv1.4 (Tseng-Crank et al. 1990; Petersen & Nerbonne, 1999). Support for a role for Kv1.4 in the generation of Ito,s was provided recently with the demonstration that rabbit atrial Ito,s is attenuated following exposure to an AsODN targeted against Kv1.4 (Wang et al. 1999). In addition, in myocytes isolated from the left ventricular septum of mice with a targeted deletion in the Kv1.4 gene (London et al. 1998b), Ito,s is undetectable, revealing that Kv1.4 also underlies Ito,s in mouse ventricle (Guo et al. 1999). As noted above, the time- and voltage-dependent properties of the transient outward K+ currents in ferret left ventricular epicardial and endocardial myocytes are distinct, and there are regional differences in the expression of Kv1.4 and Kv4.2/Kv4.3 in ferret left ventricles (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). These observations suggest that Kv1.4 and Kv4.2/Kv4.3 underlie Ito,s and Ito,f in ferret left ventricular endocardial and epicardial myocytes, respectively (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). Regional differences in the transient outward K+ currents (Ito,f and Ito,s) in rat ventricles are also attributed to the differential expression of Kv4.2/Kv4.3 and Kv1.4 (Wickenden et al. 1999a).

Molecular correlates of cardiac delayed rectifiers

Considerable progress has also been made in identifying the molecular correlates of several components of IK, including IKr, IKs, IKur and IK,slow (Table 2), in cardiac cells. Expression of erg1, identified as the locus of LQT2 mutations, for example, reveals inwardly rectifying K+-selective currents similar to IKr, suggesting that erg1 underlies cardiac IKr (Sanguinetti et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1995). It has also been reported, however, that AsODNs targeted against minK attenuate IKr in AT-1 (an atrial tumour line) cells (Yang et al. 1995), and that heterologously expressed erg1 and minK coimmunoprecipitate (McDonald et al. 1997). Although these observations were interpreted as suggesting that functional IKr channels reflect the coassembly of erg1 and minK, more recent work has revealed that a minK homologue, MiRP (rather than minK) contributes to IKr (Abbott et al. 1999). Alternatively processed forms of erg1 with unique N- and C-termini have also been identified (Lees-Miller et al. 1997; London et al. 1997; Kuperschmidt et al. 1998) and suggested to be important in the generation of functional IKr channels. Western blot analysis with anti-erg1 antibodies, however, revealed that only full-length erg1 proteins are detected in rat, mouse and human heart, suggesting that alternatively spliced erg1 variants do not contribute to functional cardiac IKr channels (Pond et al. 2000).

Although heterologous expression of KvLQT1, the locus of mutations in LQT1, reveals rapidly activating K+ currents, coexpression of KvLQT1 with minK produces slowly activating K+ currents similar to cardiac IKs (Barhanin et al. 1996; Sanguinetti et al. 1996). The fact that mutations in the transmembrane domain of minK alter the properties of IKs channels further suggests that the transmembrane segment of minK contributes to the K+-selective pore of IKs channels (Goldstein & Miller, 1991; Takumi et al. 1988; Wang et al. 1996; Tai & Goldstein, 1998). Nevertheless, direct biochemical evidence for coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK in the mammalian heart has not been provided to date, and the stoichiometry of functional IKs channels is not known. In addition, the role of the N-terminal splice variant of KvLQT1, which functions as a dominant negative (Jiang et al. 1997), in the functional expression of IKs channels remains to be determined.

The properties of the currents produced on heterologous expression of Kv1.5 are similar to those of IKur in rat (Boyle & Nerbonne, 1992), human (Wang et al. 1993a,b) and canine (Yue et al. 1996a,b) atrial myocytes. In addition, Kv1.5 mRNA (Tamkun et al. 1991; Fedida et al. 1993) and protein (Barry et al. 1995; Van Wagoner et al. 1997) are abundant in rat and human heart. Direct evidence for a role for Kv1.5 in the generation of IKur in human atrial myocytes was provided with the demonstration that IKur in these cells is selectively attenuated following exposure to AsODNs targeted against Kv1.5, whereas AsODNs against Kv1.4 were without effect (Feng et al. 1997). Rat atrial IKur is also selectively reduced following treatment with Kv1.5 AsODNs (Bou-Abboud & Nerbonne, 1999). Interestingly, rat atrial IK,slow (IK,DTX) is selectively attenuated by AsODNs targeted against Kv1.2 (Bou-Abboud & Nerbonne, 1999). These results clearly demonstrate that rat atrial IK,slow (IK,DTX) is a unique molecular entity, distinct from both Ito,f and IKur, and that Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 do not coassemble to form heteromultimeric K+ channels (in rat atria) in vivo (Bou-Abboud & Nerbonne, 1999). The molecular correlate of IKur in canine atrial myocytes (Yue et al. 1996a,b), however, remains to be identified.

An in vivo dominant-negative strategy, involving cardiac-specific expression of a truncated Kv1.1 subunit (Kv1.1N206Tag), was exploited by London and colleagues (1998a) in experiments focused on determining whether Kv1.5 (or other Kv1 α subunits) contribute to the outward K+ currents in mouse ventricle. Electrophysiological recordings from ventricular myocytes isolated from Kv1.1N206Tag-expressing transgenics revealed that IK,slow is selectively attenuated (London et al. 1998a). More recent studies, however, suggest there are two distinct components of IK,slow in mouse ventricular (and atrial) myocytes and that both Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 contribute to these two conductance pathways (Xu et al. 1999a,b E. Bou-Abboud, H. Li & J. M. Nerbonne, unpublished observations). In addition, although the molecular correlate of mouse ventricular Iss has not been determined, it has recently been suggested that Kv2.1 contributes to mouse atrial Iss (E. Bou-Abboud, H. Li & J. M. Nerbonne, unpublished observations).

The results of the various studies described above have allowed the identification of the α subunits contributing to most of the voltage-gated K+ currents expressed in cardiac cells (Table 2). It seems reasonable to suggest that in vivo and in vitro experimental strategies similar to those used in these studies can be exploited to reveal the identities of the α subunits contributing to the other voltage-gated K+ channels in cardiac cells (Table 2), as well as to define the roles of silent Kv α subunits (e.g. Kv5.x to Kv9.x) and accessory (β, KChAP) subunits in the formation and functional expression of these channels.

Summary and future directions

Electrophysiological studies have clearly documented the presence of multiple types of voltage-gated K+ channels/currents in cardiac cells isolated from different species, as well as in cells isolated from different regions of the heart in the same species (Table 1). In most myocardial cells, several voltage-gated K+ channels are expressed, and each channel type contributes importantly to shaping the waveforms of action potentials, as well as influencing automaticity and refractoriness. Molecular cloning has revealed an even greater potential for generating voltage-gated K+ channel diversity than was expected based on the electrophysiology, with the identification of many K+ channel pore-forming (α) (Table 2) and accessory (minK, MiRP1, β and KChAP) subunits in the heart. A variety of experimental approaches have been exploited recently to probe the relationship(s) between these subunits and the functional voltage-gated K+ channels in myocardial cells. Important insights into these relationships have been provided through molecular genetics and the application of techniques that allow functional voltage-gated K+ channel expression to be manipulated in vitro and in vivo. The results of these efforts have led to the identification of the α subunits contributing to the formation of most of the voltage-gated K+ channels (Ito,f, Ito,s, IKr, IKs, IKur, IK,slow) expressed in cardiac cells (Table 2). It seems reasonable to suggest that similar experimental approaches will reveal the identities of the Kv α subunits underlying the other voltage-gated K+ channels in cardiac cells (Table 1).

In contrast to the progress made in identifying the Kv α subunits that underlie the various voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels, much less is presently known about the role of accessory transmembrane (minK or MiRP1) or cytosolic (β and KChAP) subunit proteins in the formation or in the functioning of voltage-gated K+ channels in cardiac (or other) cells. Defining the roles of these subunits in the generation, regulation and modulation of voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels will be an important area for future research efforts. Similarly, very little information is available about the post-translational processing of K+ channel subunit proteins and/or about the role of these modifications in determining the properties of functional voltage-gated K+ channels in cardiac cells. There are a number of potential post-translational mechanisms, including phosphorylation, glycosylation, myristoylation, palmitoylation, etc., that could affect the properties and/or the functional expression levels of voltage-gated myocardial K+ channels (Nerbonne, 2000). Studies focused on examining post-translational processing of voltage-gated myocardial K+ channel α and β subunits, as well as those focused on determining the functional consequences of this processing and the underlying molecular mechanisms controlling post-translational processing, are likely to be major areas of future research interests and efforts.

It is now well-documented that there are marked changes in the functional expression of voltage-gated K+ channels and K+ channel-forming α subunits during normal (fetal and postnatal) cardiac development (Wetzel & Klitzner, 1996; Nerbonne, 1998), as well as in the damaged or diseased myocardium (Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Näbauer & Kääb, 1998; Carmeliet, 1999; Tomaselli & Marbán, 1999; Nerbonne, 2000). In addition, it is clear that electrical remodelling occurs in the damaged/diseased mammalian heart, presumably in direct response to changes in cardiac electrical activity or cardiac output, and that at least some of these changes can be attributed to alterations in the expression and/or the properties of voltage-gated K+ channels (Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Näbauer & Kääb, 1998; Tomaselli & Marbán, 1999; Nerbonne, 2000). There are numerous possible transcriptional (Levitan & Takimoto, 1998), translational and post-translational (Nerbonne, 2000) mechanisms that could be involved in regulating the expression and the properties of functional voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels. At present, however, very little is known about the molecular mechanisms mediating the changes in K+ channel expression/properties that are evident during normal development, as well as in conjunction with myocardial damage, disease and/or electrical remodelling. It seems certain that a major focus of future research will be on exploring these mechanisms in detail.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks several of the past and present members of her laboratory who have made important contributions to our understanding of the electrophysiological and molecular diversity of myocardial K+ channels: Drs Michael Apkon, Dianne M. Barry, Elias Bou-Abboud, Walter A. Boyle, Sylvain Brunet, Weinong Guo, Huilin Li, Amber L. Pond and Haodong Xu. The author also thanks Andrew Benedict, Rebecca Hood and Bridget Scheve for their extraordinary technical assistance in all aspects of the research effort in her laboratory focused on understanding the molecular basis of functional myocardial K+ channel diversity. Preparation of this review and the work from the author's laboratory cited here were supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, by the Monsanto/Searle/Washington University Biomedical Research Agreement, and by the National Office and the Midwest Affiliate of the American Heart Association.

References

- Abbott GW, Sesti F, Splawski I, Buck ME, Lehmann MH, Timothy KW, Keating MT, Goldstein SA. MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell. 1999;97:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accili EA, Kiehn J, Wible BA, Brown AM. Interactions among inactivating and noninactivating Kv-beta subunits, and Kv-alpha-1.2, produce potassium currents with intermediate inactivation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:28232–28236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos GJ, Wettwer E, Metzger F, Li Q, Himmel HM, Ravens U. Differences between outward currents of human atrial and subepicardial ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:31–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Lukas A, Nesterenko VV, Liu D-W, Didiego JM. Regional differences in the electrophysiology of ventricular cells: physiological implications. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. Philadelphia PA, USA: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1994. pp. 228–245. [Google Scholar]

- Anumonwo J M B, Freeman LC, Kwok WM, Kass RS. Delayed rectification in single cells isolated from guinea pig sinoatrial node. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:H921–925. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.3.H921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkon M, Nerbonne JM. Characterization of two distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:973–1011. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backx PH, Marban E. Background potassium current active during the plateau of the action potential in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1993;72:890–900. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Bennett PB, Roden DM. Time-dependent outward currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes: gating kinetics of the delayed rectifier. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;96:835–863. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. KvLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Nerbonne JM. Myocardial potassium channels: electrophysiological and molecular diversity. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:363–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Trimmer JS, Merlie JP, Nerbonne JM. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits in adult rat heart: relationship to functional K+ channels. Circulation Research. 1995;77:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Xu H, Schuessler RB, Nerbonne JM. Functional knockout of the transient outward current, long QT syndrome and cardiac remodelling in mice expressing a dominant negative Kv4 α subunit. Circulation Research. 1998;83:560–567. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biervert C, Schroeder BC, Kubisch C, Berkoviv SF, Propping P, Jentsch TJ, Steinlein OK. A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science. 1998;279:403–405. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair TA, Roberds SL, Tamkun MM, Hartshorne RP. Functional characterization of RK5, a voltage-gated K+ channel cloned from the rat cardiovascular system. FEBS Letters. 1991;295:211–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81420-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou-Abboud E, Nerbonne JM. Molecular correlates of the Ca2+-independent, depolarization-activated K+ currents in rat atrial myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:407–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0407t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WA, Nerbonne JM. A novel type of depolarization-activated K+ current in isolated adult rat atrial myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H1236–1247. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.4.H1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WA, Nerbonne JM. Two functionally distinct 4-aminopyridine-sensitive outward K+ currents in adult rat atrial myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;100:1047–1061. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmajothi MV, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Morales MJ, Nerbonne JM, Strauss HC. Distinct transient outward potassium current (Ito) phenotypes and distribution of fast-inactivating potassium channel alpha subunits in ferret left ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:581–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant SM, Wan XP, Shipsey SJ, Hart G. Regional differences in the delayed rectifier currents (IKr and IKs) contribute to the differences in action potential duration in basal left ventricular myocytes in guinea pig. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;40:322–331. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Wei A, Baker K, Salkoff L. A family of putative potassium channel genes in Drosophila. Science. 1989;243:943–947. doi: 10.1126/science.2493160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Comer MB, Strauss HC. The calcium-independent transient outward potassium current in isolated ferret right ventricular myocytes. I. Basic characterization, and kinetic analysis. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:571–601. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Comer MB, Strauss HC. The cardiac calcium-independent transient outward potassium current: kinetics, molecular properties, and role in ventricular repolarization. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 2. Philadelphia, PA, USA: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1995. pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Cardiac ionic currents and acute ischemia: from channels to arrhythmias. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:917–1017. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano A, Chiara MD, Mellströ B, Molina A, Monje F, Naranjo JR, Lopez-Barneo J. Identification and functional characterization of a K+ channel α subunit with regulatory properties specific to brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:4652–4661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04652.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellino RC, Morales MJ, Strauss HC, Rasmusson RL. Time- and voltage-dependent modulation of a Kv1.4 channel by a β subunit (Kvβ3) cloned from ferret ventricle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:H385–391. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Bouchard RA, Salinas-Stefanson E, Sanchez-Chalupa J, Giles WR. Heterogeneity of action potential waveforms and potassium currents in rat ventricle. Cardiovascular Research. 1993;27:1795–1799. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Properties of the transient outward current in rabbit atrial cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;405:147–168. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo X, Chiu J, Chow A, Lou D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz de Meira E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coraboeuf E, Carmeliet E. Existence of two transient outward currents in sheep Purkinje fibers. Pflügers Archiv. 1982;392:352–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00581631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias M, Wei A, Salkoff L. Shaker, Shal, Shab, and Shaw express independent K+ current systems. Neuron. 1991;7:763–773. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal KK, England SK, Tamkun MM. Molecular physiology of cardiac potassium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:49–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JE, McKinnon D. Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression in atrial and ventricular muscle of rats. Circulation Research. 1994;75:252–260. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JE, Shi WS, Wang HS, McDonald C, Yu H, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, McKinnon D. The role of the Kv4.3 K+ channel in ventricular muscle. A molecular correlate for the transient outward current. Circulation Research. 1996;79:659–668. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewe JA, Verma S, Frech G, Joho RL. Distinct spatial and temporal expression patterns of K+ channel mRNAs from different subfamilies. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:538–548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SK, Uebele VN, Kodali K, Bennett PB, Tamkun MM. A novel K+ channel beta subunit (hKvβ1.3) is produced via alternative mRNA splicing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:28531–28534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escande D, Coulombe A, Faivre JF, Deroubaix E, Corabouef E. Two types of transient outward currents in adult human atrial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252:H142–148. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.1.H142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Giles WR. Regional variations in action potentials and transient outward current in myocytes isolated from rabbit left ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;442:191–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Wible B, Wang Z, Fermini B, Faust F, Nattel S, Brown AM. Identity of a novel delayed rectifier current from human heart with a cloned K+ channel current. Circulation Research. 1993;73:210–216. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Wible B, Li GR, Wang Z, Nattel S. Antisense oligonucleotides directed against Kv1.5 mRNA specifically inhibit ultrarapid delayed rectifier K+ current in cultured adult human atrial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1997;80:572–579. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermini B, Wang Z, Duan D, Nattel S. Differences in rate dependence of the transient outward current in rabbit and human atrium. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:H1747–1754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Duprat F, Lesage F, Heurteux C, Romey G, Barhanin J, Lazdunski M. A new K+ channel β subunit to specifically enhance Kv2.2 (CDRK) expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:26341–26348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiset C, Clark RB, Larsen TS, Giles WR. A rapidly activating, sustained K+ current modulates repolarization and excitation-contraction coupling in adult mouse ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997a;504:557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.557bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiset C, Clark RB, Shimoni Y, Giles WR. Shal-type channels contribute to the Ca2+-independent transient outward K+ current in rat ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997b;500:51–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folander K, Smith JS, Antanavage J, Bennett C, Stein RB, Swanson R. Cloning and expression of the delayed rectifier IsK channel from neonatal rat heart and diethylstilbestrol-primed rat uterus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1990;87:2975–2979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franqueza L, Valenzuela C, Eck J, Tamkun MM, Tamargo J, Snyders DJ. Functional expression of an inactivating potassium channel Kv4.3 in a mammalian cell line. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;41:212–219. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Kass RS. Delayed rectifier potassium channels in ventricle and sinoatrial node of guinea pig: molecular and regulatory properties. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 1993;7:627–635. doi: 10.1007/BF00877630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Kimura S, Furukawa N, Bassett AL, Myerburg RJ. Potassium rectifier currents differ in myocytes of endocardial and epicardial origin. Circulation Research. 1992;70:91–103. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Myerburg RJ, Furukawa N, Bassett AL, Kimura S. Differences in transient outward currents of feline endocardial and epicardial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1990;67:1287–1291. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.5.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles WR, Clark RB, Braun AP. Ca2+-independent transient outward current in mammalian heart. In: Morad M, Kurachi Y, Noma A, Hosada M, editors. Molecular Physiology and Pharmacology of Cardiac Ion Channels and Transporters. Amsterdam: Kluwer Press, Ltd; 1996. pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Comparison of potassium currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;405:123–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SA, Miller C. Site-specific mutations in a minimal voltage-gated K+ channel alter ion selectivity and open channel block. Neuron. 1991;7:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Xu H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of transient outward K+ current diversity in mouse ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;521:587–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel HM, Wettwer E, Li Q, Ravens U. Four different components contribute to outward current in rat ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:H107–118. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka M, Kawano S. Calcium-sensitive and insensitive transient outward current in rabbit ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;410:187–212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie M, Hayashi S, Kawai C. Two types of delayed rectifying K+ channels in atrial cells of guinea pig heart. Japanese The Journal of Physiology. 1990;40:479–490. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.40.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugnot JP, Salinas M, Lesage F, Guillemare E, De Weile J, Heurteaux C, Mattei MG, Lazdunski M. Kv8.1, a new neuronal potassium channel subunit with specific inhibitory properties towards Shab and Shaw channels. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:3322–3331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. Masking of A-type K+ channel in guinea pig cardiac cells by extracellular Ca2+ American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:C1434–1438. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN. Structural elements involved in specific K+ channel functions. Annual Review of Physiology. 1992;54:537–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Tseng-Crank J, Tseng GN. Suppression of slow delayed rectifier current by a truncated isoform of KvLQT1 cloned from normal human heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:24109–24112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns DC, Nuss HB, Marban E. Suppression of neuronal and cardiac transient outward currents by viral gene transfer of dominant-negative Kv4.2 constructs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:31598–31603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon JL, Gibbons WR. Influence of chloride, potassium, and tetraethylammonium on the early outward current of sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1979a;73:117–138. doi: 10.1085/jgp.73.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon JL, Gibbons WR. 4-Aminopyridine and the early outward current of sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1979b;73:139–157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.73.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarzewska H, Peeters GA, Sanguinetti MC. Repolarizing K+ currents in non-failing human hearts: similarities between right-septal subendocardial and left epicardial ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 1995;92:1179–1187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Po S, Yamagishi T, Ashen MD, Stetten G, Tomaselli GF. Isolation and characterization of the human gene encoding Ito: further diversity by alternative mRNA splicing. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:H1963–1970. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperschmidt S, Snyders D, Raes A, Roden D. A K+ channel splice variant common in human heart lacks a C terminal domain required for expression of rapidly activating delayed rectifier current. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:27231–27235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Miller JP, Kondo C, Wang L, Duff HJ. Electrophysiological characterization of an alternatively processed ERG K+ channel in mouse and human hearts. Circulation Research. 1997;81:719–726. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan ES, Takimoto K. Dynamic regulation of K+ channel gene expression in differentiated cells. Journal of Neurobiology. 1998;37:60–68. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199810)37:1<60::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GR, Feng J, Yue L, Carrier M, Nattel S. Evidence for two components of delayed rectifier K+ current in human ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1996;78:689–696. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky SH, Antzelevitch C. Transient outward current prominent in canine ventricular epicardium but not endocardium. Circulation Research. 1988;72:1092–1103. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D-W, Antzelevitch C. Characteristics of the delayed rectifier current (IKr and IKs) in canine ventricular epicardial, midmyocardial, and endocardial myocytes. A weaker IKs contributes to the longer action potential of the M cell. Circulation Research. 1995;76:351–365. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D-W, Gintant GA, Antzelevitch C. Ionic basis for electrophysiological distinctions among epicardial, midmyocardial and endocardial myocytes from the free wall of the canine left ventricle. Circulation Research. 1993;72:671–687. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Jeron A, Zhou J, Buckett P, Han X, Mitchell GF, Koren G. Long QT and ventricular arrhythmias in transgenic mice expressing the N terminus and the first transmembrane segment of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998a;95:2926–2931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Trudeau MC, Newton KP, Beyer AK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Satler CA, Robertson GA. Two isoforms of the mouse ether-a-go-go-related gene coassemble to form channels with properties similar to the rapidly activating component of the cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Circulation Research. 1997;81:870–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Wang DW, Hill JA, Bennett PB. The transient outward current in mice lacking the potassium channel gene Kv1.4. The Journal of Physiology. 1998b;509:171–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.171bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TV, Yu Z, Ming Z, Palma E, Meyers MB, Wang KW, Goldstein SA, Fishman GI. A minK-HERG complex regulates the cardiac potassium current I(Kr) Nature. 1997;388:289–292. doi: 10.1038/40882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MaccKinnon R. Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of a voltage-activated potassium channel. Nature. 1991;350:232–235. doi: 10.1038/350232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main MC, Bryant SM, Hart G. Regional differences in action potential characteristics and membrane currents of guinea-pig left ventricular myocytes. Experimental Physiology. 1998;83:747–761. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder K, Debiasi M, Wang Z, Wible B. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a novel potassium channel β subunit from human atrium. FEBS Letters. 1995;361:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales MJ, Castellino RC, Crews AL, Rasmusson RL, Strauss HC. A novel β subunit increases the rate of inactivation of specific voltage-gated potassium channel α subunits. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:6272–6277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai T, Kakizuka A, Takumi T, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of human genomic DNA encoding a novel membrane protein which exhibits slowly activating potassium channel activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1989;61:176–181. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Barth A, Kääb S. A second calcium-independent transient outward current present in human ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 1998;98:I. [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, Uberführ P, Steinbeck G. Regional differences in current density and rate-dependent properties of the transient outward current in subepicardial and subendocardial myocytes of human left ventricle. Circulation. 1996;93:168–177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Kääb S. Potassium channel downregulation in heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;37:324–334. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K, Shi G, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Selective interaction of voltage-gated K+ channel β-subunits with α subunits. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:7084–7089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM. Regulation of voltage-gated K+ channel expression in the developing mammalian myocardium. Journal of Neurobiology. 1998;37:37–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199810)37:1<37::aid-neu4>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM. Molecular mechanisms controlling functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity and expression in the mammalian heart. In: Archer S, Rusch N, editors. Potassium Channels in Cardiovascular Biology. NY, USA: Plenum Press; 2000. (in the Press) [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S, Tanaka M, Oku T, Asai Y, Watanabe M, Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of an A-type K+ channel α-subunit, Kv4.3 in the rat. FEBS Letters. 1997;420:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KR, Nerbonne JM. Expression environment determines K+ current properties: Kv1 and Kv 4 α subunit-induced K+ currents in mammalian cell lines and cardiac myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;437:381–392. doi: 10.1007/s004240050792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po S, Roberds S, Snyders DJ, Tamkun MM, Bennett PB. Heteromultimeric assembly of human potassium channels. Molecular basis of a transient outward current? Circulation Research. 1993;72:1326–1336. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond AL, Scheve BK, Benedict AT, Petrecca K, Van Wagoner DR, Shrier A, Nerbonne JM. Expression of distinct ERG proteins in rat, mouse and human heart: relation to functional IKr channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:5997–6006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongs O. Molecular biology of voltage-dependent potassium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72:S69–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig J, Heinemann SH, Wunder F, Lorra C, Parcej DN, Dolly JO, Pongs O. Inactivation properties of voltage-gated K+ channels altered by presence of β-subunit. Nature. 1994;369:289–294. doi: 10.1038/369289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Tamkun MM. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of five voltage-gated potassium channel cDNAs expressed in rat heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:1798–1802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salata JJ, Jurkiewicz NK, Jow B, Folander K, Guinoso PJ, Raynor B, Swanson R, Fermini B. IK of rabbit ventricle is composed of two currents: evidence for IKs. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:H2477–2489. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas M, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Hugnot JP, Lazdunski M. New modulatory alpha subunits for mammalian Shab K+ channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:24371–24379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, Keating MT. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Johnson JJ, Hammerland LG, Kelbaugh PR, Volkman RA, Saccomano NA, Mueller AL. Heteropodatoxins: peptides isolated from spider venom that block Kv4.2 potassium channels. Molecular Pharmacology. 1997;51:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;96:195–215. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Delayed rectifier outward K+ current is composed of two currents in guinea pig atrial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H393–399. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.2.H393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BJ, Kubisch C, Stein V, Jentsch TJ. Moderate loss of cyclic-AMP-modulated KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channels causes epilepsy. Nature. 1998;396:687–690. doi: 10.1038/25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz TL, Temple BL, Papazian DM, Jan YN, Jan LY. Multiple potassium-channel components are produced by alternative splicing at the Shaker locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1988;331:137–142. doi: 10.1038/331137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewing S, Roeper J, Pongs O. Kvβ1 subunit binding specific for Shaker-related potassium channel α-subunits. Neuron. 1996;16:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G, Nakahira K, Hammond S, Rhodes KJ, Schechter LE, Trimmer JS. β-Subunits promote K+ channel surface expression through effects early in biosynthesis. Neuron. 1996;16:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Wymore RS, Wang H-S, Pan Z, Cohen IS, McKinnon D, Dixon JE. Identification of two nervous system-specific members of the erg potassium channel gene family. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9423–9432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09423.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata EF, Drury T, Refsum H, Aldrete V, Giles W. Contributions of a transient outward current to repolarization in human atrium. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:H1773–1781. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyders DJ. Structure and function of cardiac potassium channels. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;42:377–390. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai K-K, Goldstein S A N. The conduction pore of a cardiac potassium channel. Nature. 1998;391:605–607. doi: 10.1038/35416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto K, Li D, Hershman KM, Li P, Jackson EK, Levitan ES. Decreased expression of Kv4.2 and novel Kv4.3 K+ channel subunit mRNAs in ventricles of renovascular hypertensive rats. Circulation Research. 1997;81:533–539. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi T, Ohkubo H, Nakinishi S. Cloning of a membrane protein that induces a slow voltage-gated potassium current. Science. 1988;242:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.3194754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun MM, Knoth KM, Walbridge JA, Kroemer H, Roden DM, Glover DM. Molecular cloning and characterization of two voltage-gated K+ channel cDNAs from human ventricle. FASEB Journal. 1991;5:331–337. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.3.2001794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;42:270–283. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau MC, Warmke JW, Ganetsky B, Robertson GA. H-erg, a human inward rectifier with structural and functional homology to voltage-gated K+ channels. Science. 1995;269:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.7604285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng G-N, Hoffman BF. Two components of transient outward current in canine ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1989;64:633–647. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng-Crank J C L, Tseng G-N, Schwartz A, Tanouye MA. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a potassium channel cDNA isolated from a rat cardiac library. FEBS Letters. 1990;268:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80973-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner DR, Kirian M, Lamorgese M. Phenylephrine suppresses outward K+ currents in rat atrial myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:H937–946. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, McCarthy PM, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM. Outward K+ current densities and Kv1.5 expression are reduced in chronic human atrial fibrillation. Circulation Research. 1997;80:772–781. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldkamp MW, Van Ginneken A C G, Bouman LN. Single delayed rectifier channels in the membrane of rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1993;72:865–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KB, Arena JP, Kwok WM, Freeman I. Delayed-rectifier potassium channel activity in isolated membrane patches of guinea pig ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H1390–1393. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.4.H1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: Molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K-W, Tai K-K, Goldstein S A N. MinK residues line a potassium channel pore. Neuron. 1996;16:571–577. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Feng J, Shi H, Pond AL, Nerbonne JM, Nattel S. The potential molecular basis of different physiological properties of transient outward K+ current in rabbit and human atrial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1999;84:551–561. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Repolarization differences between guinea pig atrial endocardium and epicardium. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H1501–1506. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Delayed rectifier outward current and repolarization in human atrial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1993a;73:276–285. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Sustained depolarization-induced outward current in human atrial myocytes. Evidence for a novel delayed rectifier K+ current similar to Kv1.5 cloned channel currents. Circulation Research. 1993b;73:1061–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Rapid and slow components of delayed rectifier current in human atrial myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 1994;28:1540–1546. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmke JW, Drysdale R, Ganetzky B. A distinct potassium channel polypeptide encoded by the Drosophila eag locus. Science. 1991;252:1560–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1840699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmke JW, Ganetzky B. A family of potassium channel genes related to eag in Drosophila and mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:3438–3442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei A, Covarrubias M, Butler A, Baker K, Pak M, Salkoff L. K+ current diversity is produced by an extended gene family conserved in Drosophila and mouse. Science. 1990;248:599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.2333511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Amos G, Gath J, Zerkowski H-R, Reidemeister J-C, Ravens U. Transient outward current in human and rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 1993;27:1662–1669. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Amos G, Posival H, Ravens U. Transient outward current in human and ventricular myocytes of subepicardial and subendocardial origin. Circulation Research. 1994;75:473–482. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel GT, Klitzner TS. Developmental cardiac electrophysiology: Recent advances in cellular physiology. Cardiovascular Research. 1996;31:E52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wible BA, Yang Q, Kuryshev YA, Accili EA, Brown AM. Cloning and expression of a novel K+ channel regulatory protein, KChAP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:11745–11751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden AD, Jegla TJ, Kaprielian R, Buckx PH. Regional contributions of Kv1.4, Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 to transient outward K+ current in rat ventricle. American Journal of Physiology. 1999a;276:H1599–1607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden AD, Lee P, Sah R, Huang Q, Fishman GI, Backx PH. Targeted expression of a dominant-negative K(v)4.2 K+ channel subunit in the mouse heart. Circulation Research. 1999b;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden AD, Tsushima RG, Losita VA, Kaprielian R, Backx PH. Effect of Cd2+ on Kv4.2 and Kv1.4 expressed in Xenopus oocytes and on the transient outward currents in rat and rabbit ventricular myocytes. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 1999c;9:11–28. doi: 10.1159/000016299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]