Abstract

Many inhibitory nerve terminals in the mammalian anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) contain both glycine and GABA, but the reason for the co-localization of these two inhibitory neurotransmitters in the AVCN is unknown. We have investigated the roles of glycine and GABA at synapses on bushy cells in the rat AVCN, using receptor immunohistochemistry and electrophysiology.

Our immunohistochemical results show prominent punctate labelling of postsynaptic clusters of glycine receptors and of the receptor clustering protein gephyrin over the surface of bushy cells. In contrast, weak diffuse membrane immunolabelling of GABAA receptors was observed.

Whole-cell recordings from bushy cells in AVCN slices demonstrated that evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) were predominantly (81%) glycinergic, based on the decrease in amplitude of the IPSCs in bicuculline (10 μm). This observation was supported by the effect of strychnine (1 μm), which was to decrease the evoked IPSC (to 10% of control IPSC amplitude) and to produce a greater than 90% block of spontaneous miniature IPSCs.

These results suggest a minor role for postsynaptic GABAA receptors in bushy cells, despite a high proportion of GABA-containing terminals on these cells. Therefore, a role for metabotropic GABAB receptors was investigated. Activation of GABAB receptors with baclofen revealed a significant attenuation of evoked glycinergic IPSCs. The effect of baclofen was presynaptic, as indicated by a lack of change in the mean amplitude of spontaneous IPSCs.

Significantly, the decrease in the amplitude of evoked glycinergic IPSCs observed following repetitive nerve stimulation was reduced in the presence of the GABAB antagonist, CGP 35348. This indicates that synaptically released GABA can activate presynaptic GABAB receptors to reduce transmitter release at glycinergic synapses. Our results suggest specific pre- versus postsynaptic physiological roles for GABA and glycine in the AVCN.

Glycine and γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA) are the two major inhibitory neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS). These neurotransmitters are known to act in separate pathways in the brain and spinal cord, but may also co-localize in the same presynaptic terminals, as demonstrated in the spinal cord (Todd et al. 1996; Jonas et al. 1998), cerebellum (Ottersen et al. 1988) and anteroventral cochlear nucleus (Juiz et al. 1996). These observations raise questions concerning the particular roles of the two transmitter systems. A co-operative action has been shown in a recent study by Jonas et al. (1998), demonstrating that glycine and GABA may be co-released from the same terminals to simultaneously activate postsynaptic ionotropic glycine and GABA receptors. Close association between GABA and glycine raises other possibilities, such as the modulation of glycinergic transmission by GABAergic activation of pre- or postsynaptic metabotropic receptors.

We have investigated the roles of glycine and GABA in a rat brainstem auditory nucleus, the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN). Previous immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated glycine or GABA within the AVCN of the rat (Altschuler et al. 1986) and other species (Wenthold et al. 1986; Glendenning & Baker, 1988; Juiz et al. 1989, 1996). Three types of inhibitory terminals have been identified in the AVCN: those containing glycine or GABA alone, and those containing both glycine and GABA (Oberdorfer et al. 1988; Glendenning & Baker, 1988; Juiz et al. 1996). Interestingly, although the majority of inhibitory terminals contain glycine, approximately half the glycinergic terminals also contain GABA (Juiz et al. 1996; see also Ostapoff et al. 1997). A role for both GABA and glycine has been suggested by previous physiological studies (Caspary et al. 1994; Backoff et al. 1997), although other studies indicate that postsynaptic inhibition in the AVCN is primarily mediated by glycine (Wu & Oertel, 1986; Wickesberg & Oertel, 1990). A variety of physiological and developmental roles have been suggested for glycine and GABA in the cochlear nucleus and other auditory brainstem nuclei, but the reason for the presence of both inhibitory neurotransmitters is not clear (Wu & Oertel, 1986; Wickesberg & Oertel, 1990; Caspary et al. 1994; Ostapoff et al. 1997; Backoff et al. 1997; Kotak et al. 1998).

In the present experiments, we have examined glycinergic and GABAergic transmission in AVCN bushy cells using immunohistochemistry and electrophysiological recordings of synaptic currents. Bushy cells exhibit a simple morphology, with a spherical or globular cell body and usually a short, tufted dendrite (Cant & Morest, 1979; Wu & Oertel, 1984). As the majority of synaptic contacts are made with the cell body of bushy cells, this provides a considerable advantage in the study of synaptic currents by avoiding the problems of dendritic electrotonic attenuation (Lim et al. 1999). Our recent study on inhibitory connections with bushy cells found a correlation between glycinergic quantal current amplitude and gephyrin immunoreactive cluster area (Lim et al. 1999). Gephyrin causes clustering of glycine receptors by linking the cytoplasmic loop of the β-subunit of the glycine receptor to microtubules and microfilaments of the cytoskeleton (Kirsch et al. 1993; Meyer et al. 1995; Kirsch & Betz, 1998). Gephyrin may also associate with GABA receptors, specifically via an interaction with the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor (Essrich et al. 1998). Therefore, it is possible that both glycine and GABA receptors are co-localized with gephyrin at a proportion of the inhibitory synapses on AVCN bushy cells.

In the present study, our immunohistochemical and electrophysiological results indicate that, despite a strong co-localization of glycine and GABA in the AVCN, glycine is the major inhibitory transmitter acting at postsynaptic ionotropic receptors on bushy cells. However, the results reveal a specific presynaptic role for GABA acting via presynaptic metabotropic GABAB receptors to depress release at glycinergic synapses on AVCN bushy cells.

METHODS

Immunocytochemistry

Immunohistochemical results were obtained from rats in the early postnatal developmental period, since our electrophysiological recordings from rat AVCN slices are technically limited to the developmental period of less than 3 weeks postnatal (usually between 1 and 2 weeks). Three albino rats (3 weeks postnatal age) were injected (i.p.) with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (gt; 80 mg kg−1) and perfused via the left ventricle with cold vascular rinse (0.01 M phosphate buffer with 137 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM KCl, and 6 mM NaHCO3) followed by fixative (4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer; pH 7.4) for 10–15 min. The brainstem and spinal cords were removed, not postfixed and stored at 4°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 15 % sucrose. This light fixation regime has proven adequate for recognition of epitopes in the extracellular N-terminal regions of the α1 subunit of the glycine receptor and the β2/3 subunits of the GABAA receptor by monoclonal antibodies (mAb) 2b and bd-17, respectively (Alvarez et al. 1996, 1997). Light fixation also increases immunofluorescence for gephyrin using mAb 7a. All animal procedures were performed according to NIH guidelines and approved by the local animal welfare and ethics committee.

Transverse sections (30 μM thick) of the brainstem were obtained at the level of the cochlear nuclei on a freezing sliding microtome. The sections were immediately mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air-dried and frozen until use. Then, the sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1 % Triton X-100 (PBS-T, 0.01 M; pH 7.4) and incubated with one of the following primary antibodies: mouse mAb 7a diluted 1:100 (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, USA), mouse mAb bd-17 diluted 1:10 (Boehringer Mannheim) or mouse mAb 2b diluted 1:50 (gift from Drs J. Kirsch and H. Betz, Max Plank Institute, Frankfurt, Germany). All dilutions were made in PBS-T. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C. The sections were then washed in PBS-T and incubated for 3 h in FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:50 in PBS-T; Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA). The preparations were coverslipped with anti-fading and fluorescence mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescence preparations were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview). Low magnification imaging was performed with a ×10 objective lens (NA 0.3; pixel size 1.60 μm2) and confocal conditions (confocal aperture, laser strength, scan velocity, photomultiplier tube sensitivity, gain and offset) were kept identical when imaging immunofluorescence for each of the three antibodies. Hence, grey intensity levels reflect the relative immunofluorescence intensity obtained with each antibody in Fig. 1. High magnification analysis was carried out with a ×60 oil immersion objective lens (NA 1.4) and digitally zoomed (×2; pixel size = 0.13 μm2). The optimal confocal conditions were set for each antibody and maintained while imaging different neurons in the same or serial sections. Differences in intensity of immunolabelling between cells for each particular antibody therefore parallel immunoreactivity differences between cells (Figs 2 and 3). For surface reconstruction of selected neurons a series of optical sections separated by either 0.5 or 1 μm in the z-axis were acquired throughout whole cells. For clarity, only half-cells (from a mid-cross section to the top or bottom surfaces) were reconstructed. Figure trimming, pasting and composition was done in ImagePro Plus (version 3.0.01; Media Cybernetics) and CorelDraw 3.0 (Corel, Ottawa, Canada).

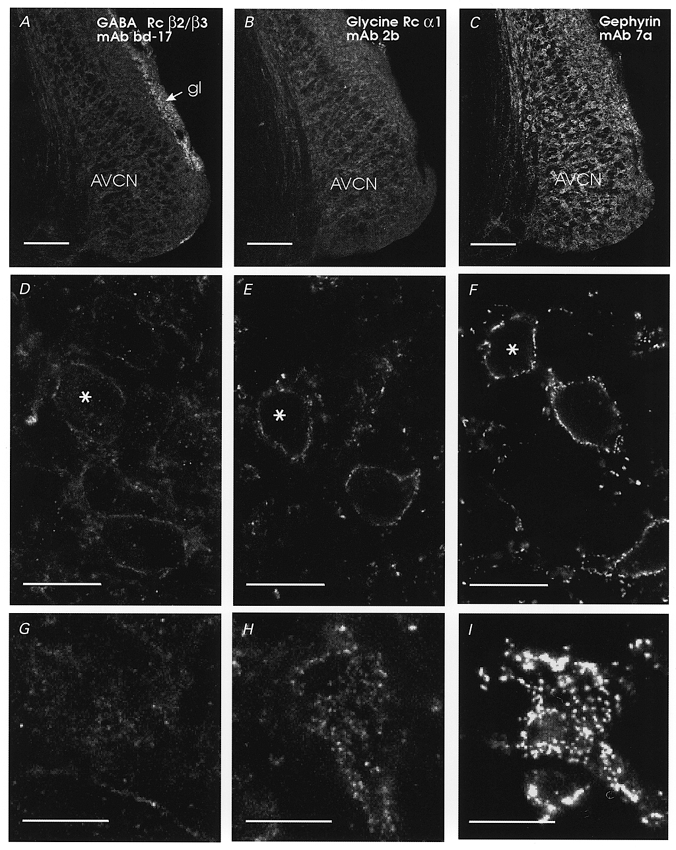

Figure 1. GABAA receptors are expressed at lower levels than glycine receptors and gephyrin on AVCN neurons.

Distribution of GABAA receptor β2/3 subunit (A, D and G), glycine receptor α1 subunit (B, E and H) and gephyrin (C, F and I) immunofluorescence in serial sections of the rat AVCN. A–C, low power confocal images obtained with identical sensitivity and gain settings, illustrating the relative immunofluorescence intensities observed with all three antibodies. GABAA receptor β2/3 subunit immunofluorescence was rather weak in the AVCN but strong in the granular layer (gl). Immunofluorescence for glycine receptor α1 subunits (B) or gephyrin (C) was stronger in the AVCN, but the cochlear nucleus granular layer did not show increased immunofluorescence for glycine receptor α1 subunits or gephyrin. D–F, medium power confocal images of AVCN neurons surrounded by immunofluorescence to GABAA receptor β2/3 subunits (D), glycine receptor α1 subunits (E) or gephyrin (F). Images are from mid-somatic optical sections of medium-sized bushy cells (characteristically rounded cell body with only one major dendrite, and located between bundles of cochlear nerve fibres). Cells indicated with asterisks have their top surfaces shown in G–I. GABAA receptor β2/3 subunit immunofluorescence was very weak and surrounded the soma and dendritic plasma membranes with little evidence of hot-spots (D). Superficial images of the top surface optical sections (G) revealed rather homogeneous and weak immunofluorescence (just above the background) with perhaps a few patches in between. In contrast, immunoreactive clusters can easily be observed with antibodies against glycine receptor α1 subunits (E and H, top surface optical section) or gephyrin (F and I, reconstruction from the two most superficial optical sections). Scale bars: A–C, 200 μm; D–F, 20 μm; G–I, 20 μm.

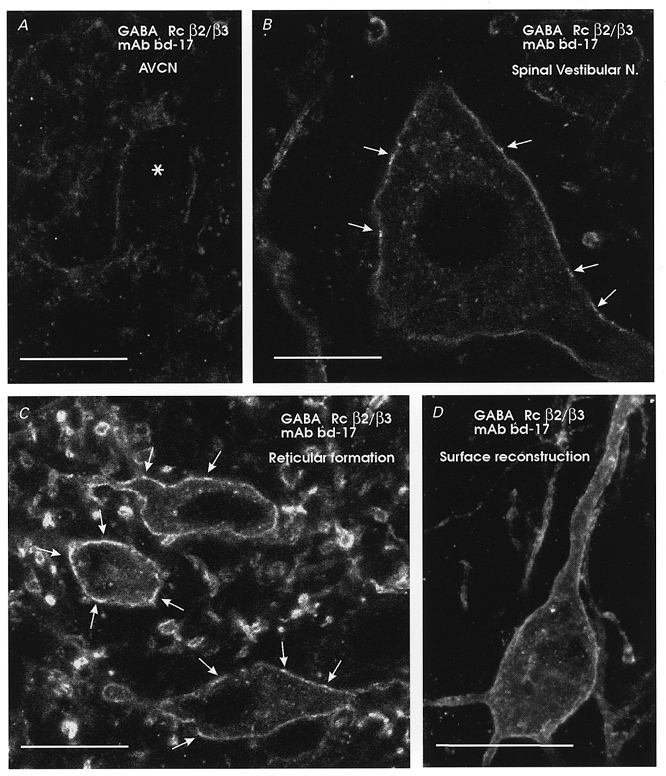

Figure 2. GABAA receptors are expressed at low levels compared with other brainstem neurons.

Comparison of immunofluorescence for the β2/3 subunits of the GABAA receptor for neurons in different nuclei of the same immunostained brainstem section. A, an AVCN neuron; B, a large neuron of the spinal vestibular nucleus with moderate immunolabelling intensity; C, intensely immunolabelled neurons of the reticular formation. AVCN neurons show comparatively very weak immunolabelling (asterisk in A indicates the soma of one neuron) and usually did not display apparent ‘hot-spots’ such as those indicated by arrows in B and C. Some cytoplasmic immunolabelling was apparent, particularly in strongly immunolabelled neurons (B and C). D, surface reconstruction of a reticular neuron (14 optical planes each separated by 0.5 μm), demonstrating continuous surface labelling for β2/3 subunits of the GABAA receptor. Scale bars, 20 μm.

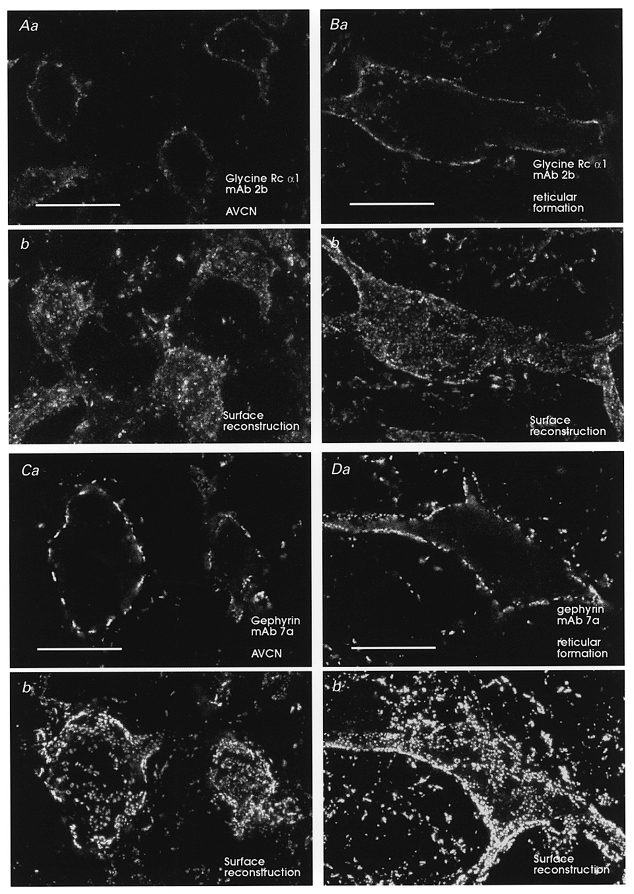

Figure 3. Glycine receptor and gephyrin expression in AVCN neurons are equivalent to other brainstem neurons.

Immunofluorescence for the α1 subunit of the glycine receptor (A) and gephyrin (C) over AVCN neurons and neurons in the reticular formation (B and D). Each neuron is illustrated in one mid-somatic optical plane (Aa, Ba, Ca and Da) or in a surface reconstruction of cluster coverage obtained from 6–12 optical sections each separated by 1 μm from the top surface of each cell (Ab, Bb, Cb and Db). There is no difference in immunostaining intensity or pattern between AVCN neurons and other brainstem neurons exhibiting high expression of glycine receptors and gephyrin. Gephyrin immunofluorescence was always more robust than immunofluorescence for glycine receptor α1 subunits (Wenthold et al. 1988). Almost all immunofluorescence appears in patches on the membrane. These patches have been shown to correspond ultrastructurally with the receptor cluster at postsynaptic densities (Triller et al. 1985; Alvarez et al. 1997). Scale bars, 20 μm.

Electrophysiology

Albino rats (Wistar, 12–16 days old) were anaesthetized with 20 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone i.p. and decapitated. Parasagittal slices (150 μm) were made of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) as previously described (Isaacson & Walmsley, 1995; Lim et al. 1999). Whole-cell patch electrode recordings (at a membrane potential of −60 mV) were made from neurons visualized in the slices using infrared differential interference contrast optics. Afferent nerve fibres were stimulated (0.1 ms, 2–40 V pulses) using a glass microelectrode filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) and placed close to the recorded cell. Experiments were performed at room temperature (22-25°C), and conducted on slices superfused with an ACSF solution containing (mM): 130 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.3 Mg2SO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, equilibrated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. Patch electrodes (3-5 MΩ resistance) contained (mM): 120 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 4 MgCl2, 0.001 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.2 GTP-tris, and 0.2-10 EGTA (pH 7.2). In one series of experiments to examine postsynaptic GABAB responses, potassium methyl-sulphate was substituted for CsCl in the patch pipette solution, and recordings were made at membrane potentials of −20 to −60 mV. Series resistance, which was <10 MΩ, was routinely compensated by >80 %. Synaptic currents were recorded and filtered at 10 kHz with an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments) before being digitized at 20 kHz. Data were also recorded on videotape with a Vetter videocassette recorder and digitized off line. Data acquisition and analysis was performed using Axograph software (Axon Instruments). The amplitudes of spontaneous IPSCs were measured using semi-automated detection procedures (Axograph 4.0), as previously described (Lim et al. 1999). Results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Significance of results was assessed using Student's paired t test. (In most cases, statistical tests on evoked IPSCs were carried out using relative changes, normalized with respect to the control IPSC, since the absolute control IPSC amplitude was arbitrarily set by the stimulus conditions for each cell.)

Drugs were added to the perfusate, as indicated, from stock H2O-based solutions (except where indicated otherwise): 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Tocris; 20 mM stock, dissolved in DMSO), (±)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV; RBI; 50 mM stock), bicuculline methochloride (Tocris; 10 mM stock), bicuculline methiodide (Sigma; 10 mM stock), strychnine hydrochloride (Sigma; 1 mM stock), tetrodotoxin (TTX; Alamone; 1 mM stock). The GABAB antagonist, 3-aminopropyl(diethoxymethyl)phosphinic acid (CGP 35348; 10 mM stock) was a gift from Novartis.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabelling experiments were carried out to provide a structural basis for subsequent electrophysiological experiments on the functional role of glycine and GABA in the AVCN. The distribution of immunolabelled glycine receptors (α1 subunit), GABAA receptors (β2/3 subunit) and gephyrin was examined over the surface of bushy cells in the rat AVCN. As a control for the AVCN immunolabelling, simultaneous observations were made of immunolabelled neurons from other adjacent brainstem nuclei (spinal vestibular nucleus, reticular formation), taken from the same histological sections. Identical imaging protocols were used to facilitate comparison between different regions and immunolabels (Methods).

Figure 1 illustrates immunolabelling results for the AVCN. GABAA receptor immunolabelling was found to be weak in most regions of the AVCN, except for a strong band of labelling in the granule cell layer (Fig. 1A). Labelling of this band is consistent with intense GABAA and GABAB binding studies (Juiz et al. 1994). In contrast, strong punctate immunolabelling of glycine receptors (Fig. 1B, E and H) and gephyrin (Fig. 1C, F and I) was found throughout the AVCN. High magnification images illustrate the punctate labelling of the receptor clusters of both the glycine receptors (Fig. 1E) and gephyrin (Fig. 1F). As reported previously (Wenthold et al. 1988), immunolabelling for gephyrin was more intense than for the α1 subunit of the glycine receptor, perhaps reflecting the better characteristics of gephyrin epitopes over α1 subunit epitopes for immunolocalization studies using these monoclonal antibodies (Kirsch & Betz, 1993; Alvarez et al. 1997). Labelling of GABAA receptors was generally diffuse with very few postsynaptic clusters (Fig. 1D). Surface reconstructions of individual cells shown by asterisks (Fig. 1D, E and F) exhibited strong punctate covering of bushy cell somas with gephyrin (Fig. 1I) and glycine receptor immunoreactivity (Fig. 1H). In contrast, GABAA receptor immunolabelling displayed only a few sparse weakly immunoreactive clusters and diffuse weak membrane labelling (Fig. 1G). This striking difference in labelling patterns suggests a lack of association between GABAA receptors and glycine receptor (or gephyrin) clusters in AVCN neurons, and indicates a predominance of glycine over GABA postsynaptic receptor clusters on AVCN neurons.

Weak GABAA immunolabelling and low numbers of local surface intensities or ‘hot-spots’ on AVCN neurons were not due to technical difficulties with the immunocytochemistry. Uniform and robust immunolabelling was observed in adjacent areas of the same sections which contained weakly immunolabelled AVCN neurons. These neighbouring brainstem neurons frequently displayed ‘hot-spots’, in addition to continuous extrasynaptic immunolabelling (Fig. 2). Diffuse cytoplasmic GABAA receptor immunoreactivity and immunoreactive granules in the cytoplasm were also clearly visible in strongly immunolabelled brainstem neurons (Fig. 2B and C). These most probably correspond to immunoreactivity localized to the Golgi apparatus and to small transport vesicles, as demonstrated previously in spinal neurons with electron microscopy (Alvarez et al. 1996). Cytoplasmic immunolabelling was rare and weak on AVCN neurons, also indicating low levels of expression of GABAA receptor subunits. In contrast, immunofluorescence intensity for glycine receptors or gephyrin was no different in AVCN neurons than in other brainstem or spinal neurons and displayed identical patterns of surface clustering or ‘hot-spots’ (Fig. 3). In addition, some intracellular granules were seen immunolabelled for glycine receptor α1 subunits but not for gephyrin, perhaps reflecting differences in the trafficking mechanisms of both molecules.

In summary, GABAA receptor β2/3 subunits appear to be expressed at lower levels on AVCN neurons compared with other brainstem neurons. In contrast, glycine receptor α1 subunits and gephyrin are expressed at levels comparable to the highest expressing neurons in other brainstem nuclei, and appear concentrated in surface clusters known to represent postsynaptic receptor aggregates (Triller et al. 1985; Wenthold et al. 1988; Alvarez et al. 1997). Our results also suggest a closer association of gephyrin with postsynaptic glycine receptors than with GABAA receptors in AVCN neurons.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were used to determine the relative contributions of glycine and GABAA receptor activation to inhibitory transmission in AVCN bushy cells. Figure 4A illustrates the postsynaptic currents recorded in a bushy cell in a thick slice preparation of the entire cochlear nucleus (approximately 300–400 μm thick), following stimulation of the auditory nerve stump with a bipolar stimulating electrode. The response demonstrates an initial large monosynaptic excitatory current (due to the endbulb of Held connections; Isaacson & Walmsley, 1995), followed by a later polysynaptic inhibitory current (Wu & Oertel, 1986). This response exemplifies the prominent but delayed nature of auditory nerve-mediated inhibitory input to bushy cells, generated within the cochlear nucleus itself (Wu & Oertel, 1986). As inhibitory inputs also originate outside the cochlear nucleus, and local inhibitory nerve fibres may be severed by the slice procedure, all subsequent experiments were carried out with IPSCs evoked using local stimulation close to the recorded cell. (Because similar results were obtained for a variety of stimulus conditions, it seems unlikely that the stimulation procedure restricted the inputs to an exclusive subset of input fibre type.) Bushy cells were visualized in thin AVCN slices (150 μm thick), identified initially on the basis of their morphology (with globular or spherical cell bodies) and, following whole-cell recording, by the presence of characteristically brief excitatory spontaneous synaptic currents, as shown in our previous studies (Isaacson & Walmsley, 1995). Following identification, AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory currents were blocked using CNQX (10 μM) and APV (50 μM), respectively, in order to record IPSCs in isolation. Between 50 and 150 evoked IPSCs were averaged to obtain a reliable measure of the control inhibitory synaptic current. These IPSCs result from the activation of multiple fibres, as evidenced by the graded nature of IPSC amplitude with stimulus voltage. For each cell, the stimulation voltage was adjusted to obtain a stable IPSC, and the voltage was not altered during the recording period.

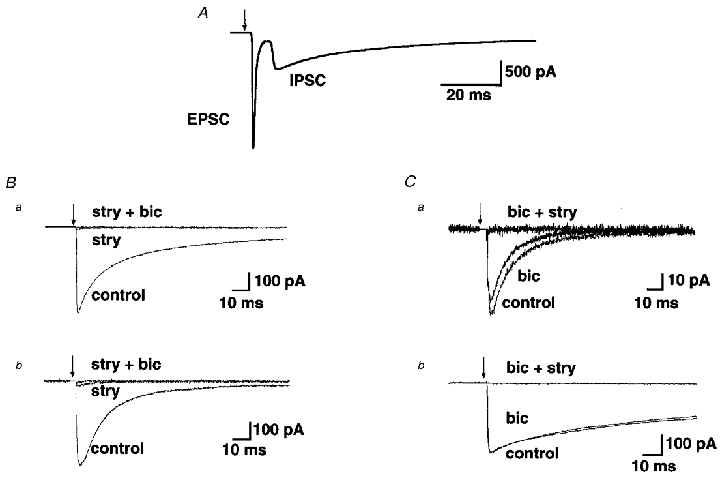

Figure 4. Inhibitory transmission in AVCN bushy cells is mediated primarily by glycine.

A, stimulation of the auditory nerve (arrow) resulted in a monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic current followed by a disynaptic inhibitory postsynaptic current in a bushy cell of the AVCN. B, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from two bushy cells following local stimulation show that strychnine (1 μM) almost completely abolishes the IPSC, while the residual current is blocked by bicuculline (10 μM). Records are averages of 102 responses (a) and 141 responses (b). C, bicuculline (10 μM) has very little effect in blocking the IPSC, which is subsequently blocked by application of strychnine (1 μM). Records are averages of 173 responses (a) and 104 responses (b) from two different bushy cells. Arrows in all panels indicate times of stimulus artefact which have been removed from all traces.

The relative glycine versus GABA contributions to evoked IPSCs were determined by addition of the pharmacological antagonists strychnine or bicuculline, respectively, to the perfusate. The concentrations of strychnine (1 μM) and bicuculline (10 μM) were chosen to provide a near-maximal effect, as determined by previous studies (e.g. Jonas et al. 1998). Although 10 μM bicuculline is likely to have very little effect on glycine receptors, there may be partial antagonism of GABA receptors by 1 μM strychnine (Jonas et al. 1998). Therefore, experiments were conducted by applying either strychnine or bicuculline first, followed by application of the other antagonist. Figure 4Ba and B illustrates the responses of two different bushy cells to application of the glycine receptor antagonist, strychnine (1 μM), followed by application of the GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (10 μM). Figure 4Ca and B illustrates the responses of two other bushy cells in which bicuculline was added first, followed by strychnine. For 11 cells in which strychnine was applied first, the evoked IPSC was decreased by application of strychnine (1 μM) to a mean of 10 ± 3.4 % of the control peak amplitude (mean peak amplitude of control IPSC, 400.7 ± 78.8 pA; mean peak amplitude in presence of strychnine, 31.6 ± 14.5 pA). Application of bicuculline (10 μM) first reduced the evoked IPSC amplitude to 81 ± 6.1 % of the control amplitude (n = 5 cells; mean peak amplitude of control IPSC, 161.7 ± 49.2 pA; mean peak amplitude in presence of bicuculline, 137.6 ± 52.4 pA). The latter result provides a more reliable quantitative estimate of the contribution of GABA receptors to the evoked IPSC, although both results suggest that the majority of the evoked IPSC is mediated by glycine receptor activation.

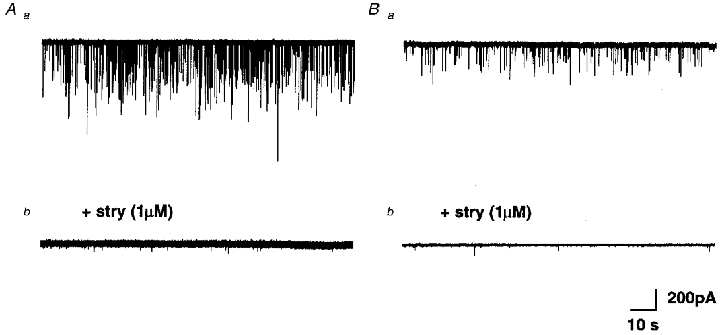

We next recorded spontaneous miniature IPSCs (mIPCSs), in the presence of TTX (1 μM) to block presynaptic action potentials (in addition to 10 μm CNQX and 50 μM APV to block glutamatergic transmission). Figure 5 shows recordings of mIPSCs in two different AVCN bushy cells (Fig. 5Aa and Ba). Addition of strychnine (1 μM) to the perfusate eliminated nearly all of the mIPSCs in both cells (Fig. 5Ab and Bb). Similar results obtained in a total of five AVCN bushy cells demonstrated that, on average, 93 % of the detectable mIPSCs in these cells are glycinergic. We have shown previously that mean glycinergic mIPSC amplitude varies considerably between bushy cells (Lim et al. 1999). The small contribution of GABAA receptor- mediated spontaneous events did not appear to differ between bushy cells displaying either predominantly large (Fig. 5A) or small (Fig. 5B) glycinergic mIPSCs.

Figure 5. Glycinergic spontaneous mIPSCs in bushy cells.

A and B, continuous whole-cell recording from two different bushy cells with large (Aa) and small (Ba) spontaneous mIPSCs, in the presence of TTX (1 μM). Application of strychnine (1 μM) abolished the majority of detectable mIPSCs in both cells (Ab and Bb).

These results suggest that glycine is the major inhibitory transmitter in the AVCN. However, a large complement of inhibitory terminals in the AVCN contain both glycine and GABA. It is therefore possible that GABA may mediate its effects through activation of metabotropic GABAB receptors. Activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors may depress transmitter release by reducing calcium currents in presynaptic terminals (Takahashi et al. 1998), while postsynaptic GABAB receptor activation may activate membrane conductances, such as a slow potassium conductance (Newberry & Nicoll, 1985). Preliminary experiments (n = 3), conducted using a potassium methylsulfate patch-electrode solution, membrane depolarization (-40 mV) and high frequency nerve stimulation (5 pulses, 50 Hz), failed to find evidence for the nerve-mediated activation of membrane currents (e.g. potassium currents) which may have resulted from postsynaptic GABAB receptor activation (data not shown).

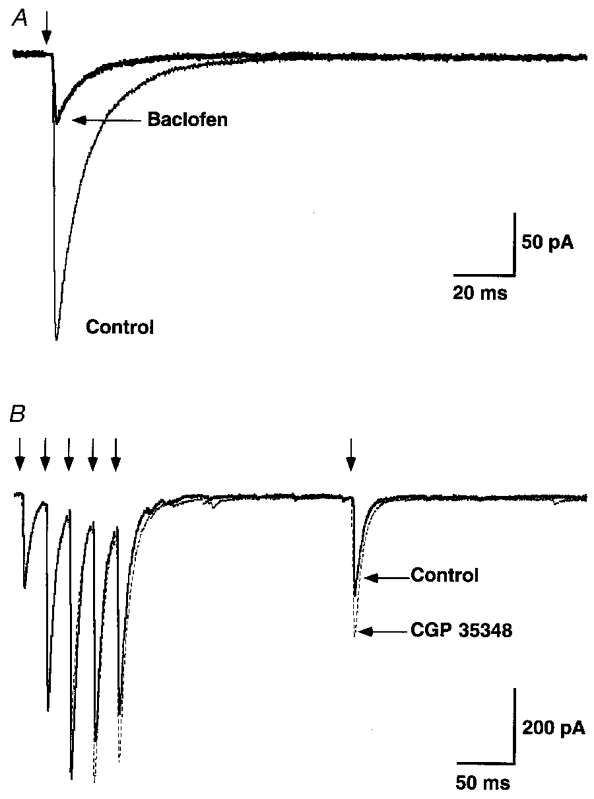

We next investigated the possible involvement of presynaptic GABAB receptors. Evoked glycinergic IPSCs were recorded before and after the addition of baclofen. Figure 6A illustrates a marked reduction by baclofen (10 μM) of the evoked IPSC. A significant reduction was observed in all cells examined (mean, 16 ± 3.9 % of control amplitude; P < 0.01, n = 3 cells). We also found that the mean amplitude of mIPSCs was unchanged in the presence of baclofen (mean control mIPSC amplitude 94 ± 21.5 pA, mean mIPSC amplitude in baclofen 91 ± 18.7 pA, P > 0.76, n = 4 cells; see also Wall & Dale, 1993; Grudt & Henderson, 1998). The lack of a postsynaptic effect on glycinergic mIPSC amplitude indicates that the dramatic reduction in nerve-evoked IPSCs following application of baclofen is most likely via activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors. A presynaptic effect was supported by the action of baclofen to decrease the mean mIPSC frequency to 62 ± 37 % (n = 4 cells) of the control value (mean frequency of control mIPCSs, 37 ± 10 mIPCSs min−1; frequency in the presence of baclofen, 23 ± 6 mIPSCs min−1; n = 4 cells). We were therefore interested in determining whether presynaptic GABAB receptors could be activated physiologically through nerve stimulation.

Figure 6. Glycinergic IPSCs are reduced by activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors.

A, nerve-evoked glycinergic IPSC, recorded in the presence of CNQX (10 μM), APV (50 μM) and bicuculline (10 μM). Application of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (10 μM) significantly attentuated the evoked glycinergic IPSC (85 % reduction). Traces are averages of 98 records. B, glycinergic IPSCs during a pulse train (5 pulses at 50 Hz), followed by a single stimulus (delay 200 ms), before (continuous traces) and after (dashed lines) bath application of the GABAB antagonist CGP 35348 (500 μM). Traces are averages of 50 records. Stimulus artefacts have been removed (arrows).

We examined the effect of the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 35348 on the nerve-evoked glycinergic IPSC, during repetitive trains of stimuli. Figure 6B illustrates nerve-evoked glycinergic IPSCs isolated in the presence of CNQX, APV and bicuculline. The control trace (average of 5 pulse trains; continuous line) illustrates glycinergic IPSCs during a brief stimulus train (5 pulses, 50 Hz), followed by a single test stimulus 200 ms after the train. If GABA were co-released during the stimulus train, then it may act presynaptically to depress glycine release and thus reduce the evoked IPSCs. Application of the GABAB antagonist should therefore block this effect and produce an increase in the evoked glycinergic IPSCs. Figure 6B (dashed lines) shows that this is the case. An increase in the amplitude of the test IPSC can be seen, following bath application of CGP 35348 (500 μM; Isaacson et al. 1993). No significant change was observed in the amplitude of the first IPSC in the pulse train (P1), ruling out a possible non-specific effect of CGP 35348 (P > 0.05; mean control IPSC amplitude 713 ± 299 pA). In all six cells examined, an increase was observed in the ratio of the delayed test IPSC to the first (control) IPSC in the train, in the presence of CGP 35348 (mean increase, 26 ± 8.7 % P < 0.01, n = 6 cells). This result demonstrates that presynaptic GABAB receptors can be activated by synaptically released GABA during repetitive nerve activation, resulting in a reduction of glycine release.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have reported a large proportion of inhibitory presynaptic terminals in the AVCN containing both GABA and glycine (Oberdorfer et al. 1988; Juiz et al. 1989, 1996; Ostapoff et al. 1997). The electrophysiological results presented here indicate that postsynaptic inhibition in bushy cells of the AVCN is mediated primarily by glycine, with only a minor contribution from GABAA receptors, as previously suggested in the mouse (Wu & Oertel, 1986). A major postsynaptic role for glycine in contrast to GABA is supported by our immunohistochemical results using monoclonal antibodies known to specifically immunolocalize GABAA receptor β2/3 subunits (mAb bd-17; Ewert et al. 1990), glycine receptor α1 subunits or gephyrin (mAbs 2b and 7a; Pfeiffer et al. 1984). Beta subunits are almost universal in functional brain GABAA receptors, since they are necessary for forming the native GABA/muscimol and picrotoxin binding sites and targeting of the receptor (Mehta & Ticku, 1999). In the AVCN, β2 and β3, but not β1, expression has been detected using in situ hybridization (Zhang et al. 1991). Therefore, it is likely that antibodies raised against a shared epitope of β2/3 subunits (Ewert et al. 1990) will detect a large proportion of (if not all) functional GABAA receptors expressed by AVCN neurons. In contrast to GABAA receptors, mature postsynaptic glycine receptors are generally formed by only two subunit types (Kuhse et al. 1993), although the presence of α subunit homo-oligomers at postsynaptic sites has also been proposed (Legendre, 1997). Molecular variability in α subunits has also been detected (reviewed in Betz, 1992) and AVCN neurons in animals younger than 5 weeks co-express all three α subunits cloned in the rat (Sato et al. 1995). Alpha-1 subunits are upregulated after 4 days of postnatal development (Friauf et al. 1997), α2 subunits are downregulated after 5 weeks of postnatal development and α3 subunits are expressed throughout (Sato et al. 1995). A preponderance of α1 subunits is suggested, based on the relative intensity of the in situ hybridization signal (Sato et al. 1995). Hence, immunohistochemistry against the α1 subunit of the glycine receptor constitutes an adequate target to compare the distribution of glycine receptors to that of gephyrin or GABAA receptors. Finally, gephyrin is a protein associated with the inner leaf of the plasma membrane and specifically associated with postsynaptic sites at inhibitory synapses (Triller et al. 1985). Many studies have demonstrated an important role for gephyrin in the postsynaptic clustering of glycine receptors at spinal and brainstem synapses (Kirsch et al. 1993; Meyer et al. 1995; Kirsch & Betz, 1998). More recent studies provided evidence suggesting a possible interaction between gephyrin and GABAA receptors at certain synapses (Essrich et al. 1998), and it is therefore important to elucidate which receptors are preferentially expressed by neurons displaying prominent gephyrin clusters on their surfaces.

Glycine receptor and gephyrin immunolabelling showed many intense punctate clusters over the surface of AVCN bushy cells of very similar appearance, frequency and distribution, compared with weak, diffuse labelling of postsynaptic GABAA receptors. Weak GABAA receptor labelling and the fixation sensitivity of targeted epitopes may explain previous observations at the light microscopic level reporting undetectable labelling, using avidin-peroxidase techniques in more strongly fixed tissue with another monoclonal antibody of similar specificity to the one used here (Juiz et al. 1989). Weak β2/3 subunit immunolabelling is also consistent with low levels of GABAAβ2/3 subunit expression detected using in situ hybridization (Zhang et al. 1991). We conclude that GABAA receptors are expressed at low levels in AVCN neurons and do not appear to greatly concentrate at postsynaptic membrane ‘hot-spots’. Our results are consistent with GABA receptor β2/3 subunits located at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites (Nusser et al. 1998). In contrast, both glycine receptor and gephyrin immunolabelling is concentrated in membrane clusters that ultrastructurally have been shown to correspond to postsynaptic sites (Triller et al. 1985; Wenthold et al. 1988; Alvarez et al. 1997).

Previous reports have shown a decrease in glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission via activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors by baclofen (e.g. Thompson & Gahwiler, 1992; Brenowitz et al. 1998). Our electrophysiological results demonstrate that the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, strongly attenuates the amplitude of the postsynaptic glycinergic IPSCs in AVCN bushy cells. Our results also show that baclofen does not change the mean amplitude of glycine mIPSCs, consistent with similar observations in Xenopus embryo motoneurons (Wall & Dale, 1993) and rat substantia gelatinosa neurons (Grudt & Henderson, 1998). Our results suggest that baclofen depresses transmitter release through activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors located on glycinergic terminals (Wall & Dale, 1993; Grudt & Henderson, 1998; Jonas et al. 1998), possibly due to a reduction in calcium entry into the presynaptic terminal (Wall & Dale, 1994; Takahashi et al. 1998). The existence of presynaptic GABAB receptors on nerve terminals does not provide direct evidence in support of a physiological role for these receptors. Importantly, such a role in the AVCN was supported by the further observation that nerve-mediated release of GABA following repetitive stimulation depresses glycinergic inhibitory transmission via activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors.

Nerve-mediated presynaptic inhibition may be due to a number of different mechanisms. The most direct mechanism is via presynaptic contacts, as demonstrated in the spinal cord (Walmsley et al. 1987). However, this is unlikely in the AVCN, since electron microscopy studies have not reported the existence of presynaptic boutons on nerve terminals contacting bushy cells (Wenthold, 1987; Ostapoff & Morest, 1991). Our observation of nerve-mediated activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors is therefore probably due to autoinhibition arising from co-release of GABA and glycine from the same terminals, or diffusion of GABA from nearby nerve terminals (Isaacson et al. 1993). Since the large excitatory auditory terminals (the endbulbs of Held) on the soma of bushy cells interdigitate with the inhibitory nerve terminals (Ostapoff & Morest, 1991; Lim et al. 1999), this raises the interesting possibility that GABA may spillover sufficiently to activate presynaptic receptors on the excitatory terminals. This possibility, supported by the observation that baclofen severely depresses transmission at the endbulb synapse (B. Walmsley, unpublished observations; Brenowitz et al. 1998), may provide an additional role for GABA in the AVCN.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the present results were obtained in immature rats (less than 3 weeks postnatal age), during a period when there are likely to be developmental changes in inhibitory transmission in the AVCN (Sato et al. 1995; Friauf et al. 1997). A developmental role for GABA in the brainstem auditory system has been suggested by Kotak et al. (1998), who have described a developmental transition from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the gerbil over the first 2 weeks postnatal. Whether there is a further shift in the relative roles of GABA and glycine in the adult rat AVCN remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Drs Ian Forsythe and Sharon Oleskevich for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. This work was supported by the HFSP (F.J.A.), and NIH grants (33555 and 25547; F.J.A. and R. E. W. Fyffe).

References

- Altschuler RA, Betz H, Parakaal MH, Reeks KA, Wenthold RJ. Identification of glycinergic synapses in the cochlear nucleus through immunocytochemical localization of the postsynaptic receptor. Brain Research. 1986;369:316–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Blake B, Fyffe REW, DeBlas AL, Light AR. Distribution of immunoreactivity for the β2 and β3 subunits of the GABAA receptor in the mammalian spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;365:392–412. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960212)365:3<392::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Dewey DE, Harrington DA, Fyffe REW. Cell-type specific organization of glycine receptor clusters in the mammalian spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;379:150–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backoff PM, Shadduck P, Caspary DM. Glycinergic and GABAergic inputs affect short-term suppression in the cochlear nucleus. Hearing Research. 1997;110:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz H. Structure and function of inhibitory glycine receptors. Quarterly Reviews in Biophysics. 1992;25:381–394. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz S, David J, Trussell LO. Enhancement of synaptic efficacy by presynaptic GABAB receptors. Neuron. 1998;20:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB, Morest DK. Organisation of the neurons in the anterior division of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. Light-microscopic observations. Neuroscience. 1979;4:1909–1923. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Backoff PM, Finlayson PG, Palombi PS. Inhibitory inputs modulate discharge rate within frequency receptive fields of anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:2124–2133. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essrich C, Lorez M, Benson JA, Fritschy J, Luscher B. Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the gamma2 subunit and gephyrin. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:563–571. doi: 10.1038/2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewert M, Shivers BD, Luddens H, Mohelt H, Seeburg PH. Subunit selectivity and epitope characterization of mABs directed against the GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor. Journal of Cell Biology. 1990;110:2043–2048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friauf E, Hammerschmidt B, Kirsch J. Development of adult-type inhibitory glycine receptors in the central auditory system of rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;385:117–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970818)385:1<117::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendenning KK, Baker BN. Neuroanatomical distribution of receptors for three potential inhibitory neurotransmitters in the brainstem auditory nuclei of the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;275:288–308. doi: 10.1002/cne.902750210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Henderson G. Glycine and GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in rat substantia gelatinosa: inhibition by μ-opioid and GABAB agonists. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:473–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.473bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Solis JM, Nicoll RA. Local and diffuse synaptic actions of GABA in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1993;10:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90308-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Sandkuhler J. Corelease of two fast neurotransmitters at a central synapse. Science. 1998;281:419–424. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juiz JM, Albin RL, Helfert RH, Altschuler RA. Distribution of GABAA and GABAB binding sites in the cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Brain Research. 1994;639:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juiz JM, Helfert RH, Bonneau JM, Wenthold RJ, Altschuler RA. Three classes of inhibitory amino acid terminals in the cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;373:11–26. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960909)373:1<11::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juiz JM, Helfert RH, Wenthold RJ, DeBlas AL, Altschuler RA. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor in the guinea pig cochlear nucleus: evidence for receptor localization heterogeneity. Brain Research. 1989;504:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch J, Betz H. Widespread distribution of gephyrin, a putative glycine receptor-tubulin linker protein, in rat brain. Brain Research. 1993;621:301–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90120-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch J, Betz H. Glycine-receptor activation is required for receptor clustering in spinal neurons. Nature. 1998;392:717–720. doi: 10.1038/33694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch J, Wolters I, Triller A, Betz H. Gephyrin antisense oligonucleotides prevent glycine receptor clustering in spinal neurons. Nature. 1993;366:745–748. doi: 10.1038/366745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak VC, Korada S, Schwartz IR, Sanes DH. A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:4646–4655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhse J, Laube B, Magalei D, Betz H. Assembly of the inhibitory glycine receptor: identification of amino acid sequence motifs governing subunit stoichiometry. Neuron. 1993;11:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90218-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. Pharmacological evidence for two types of postsynaptic glycinergic receptors on the Mauthner cell of 52-h-old zebrafish larvae. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:2400–2415. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim R, Alvarez FJ, Walmsley B. Quantal size is correlated with receptor cluster area at glycinergic synapses in the rat brainstem. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0505v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AK, Ticku MK. An update on GABAA receptors. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;29:196–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Kirsch J, Betz H, Langosch D. Identification of a gephyrin binding motif on the glycine receptor β subunit. Neuron. 1995;15:563–572. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry NR, Nicoll RA. Comparison of the action of baclofen with gamma-aminobutyric acid on rat hippocampal pyramidal cells in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;360:161–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Segregation of different GABAA receptors to synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes of cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorfer MD, Parakkal MH, Altschuler RA, Wenthold RJ. Ultrastructural localization of GABA-immunoreactive terminals in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Hearing Research. 1988;33:229–238. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapoff E, Benson CG, Saint-Marie RL. GABA- and glycine-immunoreactive projections from the superior olivary complex to the cochlear nucleus in guinea pig. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;381:500–512. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970519)381:4<500::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapoff E, Morest DK. Synaptic organization of globular bushy cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus of the cat: a quantitative study. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;314:598–613. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Somogyi P. Colocalization of glycine-like and GABA-like immunoreactivities in Golgi cell terminals in the rat cerebellum: a postembedding light and electron microscopic study. Brain Research. 1988;450:342–353. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer F, Simler R, Grenningloh G, Betz H. Monoclonal antibodies and peptide mapping reveal structural similarities between the subunits of the glycine receptor of rat spinal cord. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1984;81:7224–7227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Kuriyama H, Altschuler RA. Expression of glycine receptor subunits in the cochlear nucleus and superior olivary complex using non-radioactive in-situ hybridization. Hearing Research. 1995;91:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Kajikawa Y, Tsujimoto T. G-protein-coupled modulation of presynaptic calcium currents and transmitter release by a GABAB receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3138–3146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SM, Gahwiler BH. Comparison of the actions of baclofen at pre- and postsynaptic receptors in the rat hippocampus in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:329–345. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, Watt C, Spike RC, Sieghart W. Colocalization of GABA, glycine and their receptors at synapses in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:974–982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-00974.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triller A, Cluzeaud F, Pfeiffer F, Betz H, Korn H. Distribution of glycine receptors at central synapses: an immunoelectron study. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101:683–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MJ, Dale N. GABAB receptors modulate glycinergic inhibition and spike threshold in Xenopus embryo spinal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;469:275–290. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MJ, Dale N. GABAB receptors modulate an omega-conotoxin-sensitive calcium current that is required for synaptic transmission in the Xenopus embryo spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:6248–6255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-06248.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley B, Wieniawa E, Nicol MJ. Ultrastructural evidence related to presynaptic inhibition of primary muscle afferents in Clarke's column of the cat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:236–243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-01-00236.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ. Evidence for a glycinergic pathway connecting the two cochlear nuclei: an immunocytochemical and retrograde transport study. Brain Research. 1987;415:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ, Parakkal MH, Oberdorfer MD, Altschuler RA. Glycine receptor immunoreactivity in the ventral cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;276:423–435. doi: 10.1002/cne.902760307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ, Zempel JM, Parakkal MH, Reeks KA, Altschuler RA. Immunocytochemical localization of GABA in the cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Brain Research. 1986;380:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91423-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickesberg RE, Oertel D. Delayed, frequency-specific inhibition in the cochlear nuclei of mice; a mechanism for monoaural echo suppression. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:1762–1768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01762.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SH, Oertel D. Intracellular injection with horseradish peroxidase of physiologically characterized stellate and bushy cells in slices of mouse anteroventral cochlear nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1984;4:1577–1588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-06-01577.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SH, Oertel D. Inhibitory transmission in the ventral cochlear nucleus is probably mediated by glycine. Journal of Neuroscience. 1986;6:2691–2706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-09-02691.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sato M, Tohyama M. Region-specific expression of the mRNAs encoding subunits (1, 2 and 3) of the GABAA receptor in the rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;303:637–657. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]