In this issue of The Journal of Physiology the properties and somatodendritic distribution of voltage-gated K+ channels in pyramidal cells of neocortex are systematically analysed in three papers: two companion papers by John Bekkers (JB) in Canberra (Bekkers, 2000a,b) and one paper by Alon Korngreen and Bert Sakmann (K&S) in Heidelberg (Korngreen & Sakmann, 2000). Both laboratories focus on K+ channels in one of the most remarkable cell types in the mammalian brain: the large layer V (L5) pyramidal cells. These are primary output cells of the cortex, with long apical dendrites that rise through most of the cortical thickness, receiving thousands of synaptic contacts and reaching lengths of nearly 1 mm in the rat (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

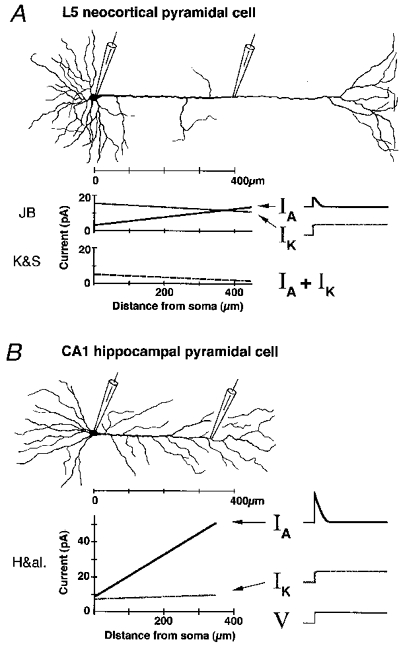

Schematic comparison of large cortical layer 5 pyramidal cell (A) and CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cell (B) from rat, with main voltage-gated currents IA and IK (elicited by depolarizing voltage clamp step, V) and their distributions along the cells. Distribution plots for L5 based on data from three papers in this issue of The Journal of Physiology (JB: Bekkers, 2000a,b; K&S: Korngreen & Sakmann, 2000). Plots for CA1 based on Hoffman et al. (1997: H&al.).

For decades it was believed that the dendrites of these and other neurones were passive structures which served merely to collect, integrate and funnel synaptic currents to the soma and axon, where the active responses – action potentials (APs) – were finally generated. In recent years, this view has been thoroughly revised. Convergent evidence from electrical and optical recordings has made it clear that dendrites are electrically highly active structures, equipped with a rich variety of voltage-gated ion channels at high densities (Stuart et al. 1997; Johnston et al. 1999). Hence, pyramidal cell dendrites can actively boost, suppress or reshape synaptic potentials, and generate and conduct APs, usually in the retrograde direction from the soma to the dendrites (so-called ‘back-propagation’). However, until recently very little was known about dendritic K+ channels.

Three years ago, Dax Hoffman and colleagues in Dan Johnston's group reported (Hoffman et al. 1997) that a particular class of voltage-gated K+ channels-fast-inactivating (‘A-type’) channels- have a surprising distribution in hippocampal CA1 pyramids: A-channel density increases steeply along the apical dendrite, being >5-fold concentrated in the distal dendrites compared to the soma. In addition, a shift in the voltage dependence of the distal A-channels increases their impact in the sub-threshold range. In one stroke, this discovery seemed to explain a series of observations, in particular why the dendrites appeared to be passive, i.e. why APs are not normally initiated in the dendrites, in spite of their high densities of Na+ and Ca2+ channels and excitatory inputs. It also seemed to explain why dendritic APs are smaller in amplitude than somatic ones, and why dendritic APs are greatly boosted by pairing with synaptic input, through voltage-dependent inactivation of local A-channels. This provides an elegant Hebbian associativity mechanism that can promote long-term synaptic plasticity such as LTP, and that is itself regulated by several neuromodulators (Johnston et al. 1999).

These findings in the hippocampus have underscored the importance of also mapping K+ channel distributions in other CNS neurones, not least in the related neocortical pyramidal cells, in which dendritic spike propagation and initiation, as well as interesting forms of associative synaptic plasticity, have been thoroughly demonstrated (Stuart et al. 1997). The large L5 pyramidal cells have attracted the interest of electrophysiologists for decades. Their large size permits stable intracellular recordings, and they were among the first mammalian brain neurones to be voltage clamped (Schwindt, 1992). Their prominent apical dendrite soon became a favourite target for patch clampers exploring the active properties of dendrites (Stuart et al. 1997). However, in spite of a series of important studies in L5 pyramids by several groups, there has been a lack of systematic studies of K+ channels that fully exploit the unique advantages of the patch clamp method. In particular, little was known about voltage-gated K+ channels in the prominent dendrites of these cells. The three papers appearing in the present issue do much to fill this gap.

The preparation and methodological approach used in these papers are nearly identical. Both laboratories obtained patch clamp recordings, guided by infrared video microscopy, from the soma and apical dendrite of large L5 pyramids (Fig. 1A), in neocortical slices from young rats. First, to characterise the main K+ currents in the soma efficiently, they recorded from large outside-out somatic membrane patches containing the nucleus (nucleated patches). Since the large ‘macroscopic’ currents recorded in this way are not dominated by single channel noise, they could be measured with little or no averaging. Also, the spherical shape of nucleated patches ensures good voltage clamp control over the entire membrane area, thus avoiding ‘space clamp’ problems that often limit the value of traditional whole cell recordings from cells with intact dendrites. The outside-out configuration also allows pharmacological properties to be characterised by puffing on K+ channel blockers.

JB and K&S used similar (but not identical) voltage clamp protocols under conditions giving little or no contribution from Na+, Ca2+, or Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Both found two major voltage-gated K+ currents in the somatic membrane: a typical fast-inactivating A-type K+ current (here abbreviated as IA) and a more sustained K+ current of delayed-rectifier type (dubbed IK). Using the two classical K+ channel blockers 4-AP and TEA, the pharmacological profiles of the currents were found to be very similar to those reported in many other CNS neurones: IA was blocked by 4-AP, but not by TEA, whereas IK was blocked by TEA but not by 4AP. In both studies, these blockers, along with suitable voltage protocols, were used to separate the two currents. The effects of a range of peptide toxins (K&S) and cadmium ions (JB) were also determined.

In both labs, IK was found to inactivate with two time constants (both somewhat voltage dependent) of 0.2-1 and 3–6 s. In contrast, IA inactivated mono-exponentially with a weakly voltage-dependent time constant of 5–8 ms over the range -30 to +70 mV. The time constant of recovery from inactivation, however, was strongly voltage dependent, with a maximum of 50–60 ms near -70 mV. The activation speed was also similar for the two studies, at least for IA at positive membrane potentials (τ∼0.3-1 ms for IA at >0 mV) and for IK at negative potentials. The activation and inactivation curves had similar slope factors (k= 17-20 for IA activation, 7–10 for IA inactivation, and 9–13 for IK activation and inactivation), but the midpoints were shifted to more depolarised levels in K&S compared to JB (15-20 mV shift for IA and ∼8 mV for IK).

In spite of these and other apparent differences, the studies agree well in their main conclusions regarding the somatic voltage-gated K+ currents of L5 pyramids. They both found a fast transient A-current and a slower, more sustained delayed rectifier current (with two kinetic components), similar to those observed in many other CNS neurones (Rudy, 1999). The patch clamp techniques they used allow these currents for the first time to be unequivocally pinpointed to the soma, and provide a uniquely systematic and accurate (due to excellent space clamp) characterisation of the K+ currents in these cells.

Next, both labs proceeded to characterise the single channel properties at the soma, using only cell-attached patches (K&S), or cell-attached patches at the soma plus outside-out patches from the dendrites (JB). Again, both labs identified two main groups of voltage-gated somatic K+ channels: fast-inactivating A-type and a more sustained delayed rectifier type. JB found that single A- and K-type channels showed about the same voltage dependence as IA and IK, respectively. However, the Heidelberg group found a 4-fold slower inactivation of single A-channels compared to IA in nucleated patches, whereas JB observed no such difference (τ= 9 vs. 7 ms, respectively). As mentioned by K&S, washout of cytoplasmic components in nucleated patches might alter the currents, implying that the A-channels are modulated. The recent discovery of accessory subunits that slow down A-channel inactivation (KChIPs; An et al. 2000) might be relevant in this context.

Some differences in single channel conductances were also observed. Whereas K&S found an A-type single channel conductance of 13 pS, JB found 8.5 pS. K&S also found two distinct types of delayed rectifier channels (16 and 9.5 pS), with inactivation properties corresponding to the slow and faster IK time constants seen in nucleated patches. In contrast, JB found a single 20 pS channel type whose inactivation kinetics differed between patches, thus apparently accounting for both kinetic components of IK.

Finally, in perhaps the most exciting part of these studies, both labs mapped the distribution of voltage-gated K+ channels from the soma and along the apical dendrite, by recording from membrane patches. This is a demanding and laborious procedure, not only because it is difficult to obtain stable patch recordings from dendrites. In addition, the tiny size of each membrane sample plus uneven channel distributions and the stochastic ‘noisy’ activity of single channel molecules, makes it necessary both to sample a large number of patches and to average multiple recordings (‘ensemble averages’) for every voltage step in each patch. However, only this approach can precisely localise different functional channel types.

So, did the two studies find the same channel distributions? Almost, but not quite. First and foremost, both arrive at the surprising result that the gradient of A-channels in layer 5 cells is very different from that in hippocampal CA1 cells (as first reported by Bekkers & Stuart, 1998). Compared to the steep 5-fold increase in A-channel density found in CA1 apical dendrites, the overall K+ channel gradient along L5 dendrites is remarkably flat (Fig. 1A,B). K&S even saw a small but significant decrease in K+ channel density outwards along the L5 dendrites. Equally important, the total density of K+ currents found in distal L5 dendrites was only a fraction of what was found in CA1 (2-20 vs. 60 pA per patch) with roughly similar voltage protocols. In addition, JB found that the maximal amplitude of IA was considerably smaller than IK near the soma in L5 cells, whereas IA was equal (soma) or 5-fold larger (distal dendrite) than IK in CA1 (Fig. 1). Thus both studies seem to indicate that IA is far less prominent in L5 than in hippocampal pyramids. By combining somatic whole cell recording and cell-attached patch recording from the apical dendrite, JB also provides an elegant direct demonstration that A- and K-channels open during a single back-propagating AP.

There are, however, two notable differences in L5 K+ channel distributions described by the two groups. First, JB found a maximal A-type conductance of 500–770 μS cm−2 (using two different methods), whereas the Heidelberg team obtained 270 μS cm−2. Use of slightly different intracellular media and series resistance compensation might contribute to this difference, but cannot explain the larger differences in absolute current density found in cell-attached patches. For example, 400 μm from the soma JB found ∼25 pA per patch, with roughly equal parts IA and IK, whereas K&S observed a total (IA+IK) of ∼2 pA per patch. The fact that JB used both outside-out and cell-attached patch configuration, whereas K&S used only cell-attached, may be a contributing factor, but does not seem to fully explain the observed differences in densities (see Fig. 6 in Bekkers, 2000b). Perhaps a more likely cause of this and other differences is the use of older rat pups in the single channel study of JB (13-28 days, vs. 13–15 days in K&S and in the nucleated patch experiments of JB) combined with a possible developmental increase in channel density. Also, it is always possible that slightly different cell populations or patch sizes were sampled. Age differences may also help explain the much larger currents found in CA1 cells by Hoffman et al. (1997), who used 35- to 56-day-old rats. Future studies of developmental changes in channel densities may help resolve this issue. Thus, in spite of the truly impressive amount of work condensed in each of these papers, more experiments of this type will still be useful.

In conclusion, there is good agreement between the two studies with respect to their main findings: the main kinetic and pharmacological properties of the principal K+ currents (IA and the two IK components), and the striking difference in dendritic A-channel distribution between hippocampal CA1 and neocortical L5 pyramid cells.

What might be the functional significance of this difference between CA1 and L5 cells? It seems that A-channels cannot be such powerful dendritic shock absorbers in L5 cells as they are in CA1. Assuming similar Na+ channel properties and densities in the two cell types, dendritic A-channels in L5 cells should be less effective suppressors of dendritic AP initiation and back-propagation than in CA1. However, it remains to be seen how this can be reconciled with the apparent functional similarities between L5 and CA1 dendrites: in neither of them are Na+ APs normally initiated by synaptic input, and both show an almost identical decline in AP amplitude with distance from soma. These observations seem to undermine the hypothesis that a steep gradient of dendritic A-channels is necessary for both of these phenomena. Again, it seems important to test for developmental differences.

Nevertheless, the new data suggest that the A-channels in L5 cells play less of a role in integrating sub-threshold synaptic potentials and back-propagating APs than in CA1 cells. K&S point out that the low K+ channel density in the distal dendrite, close to the apical dendritic tuft, may permit Ca2+ spikes to be triggered by coincident distal synaptic input and back-propagating APs. Since such dendritic Ca2+ spikes are thought to be instrumental in burst-generation in these cells (Larkum et al. 1999), the particular K+ channel distribution of L5 cells may be tailored for local coincidence detection and signal processing in the distal dendrites, allowing them to function as a separate integrating unit. It will be exciting to follow future work exploring K+ channel gradients further out in the distal dendrites, into the apical tuft (Fig. 1A), and the modulation of dendritic K+ channels. Thus, the new results from Bekkers, and Korngreen & Sakmann, provide an important foundation for a range of future studies.

References

- An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling HP, Mendoza G, et al. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM. Journal of Physiology. 2000a;525:593–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM. Journal of Physiology. 2000b;525:611–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM, Stuart G. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998;24:2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Hoffmann DA, Colbert CM, Magee JC. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1999;9:288–292. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korngreen A, Sakmann B. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, Zhu JJ, Sakmann B. Nature. 1999;398:338–341. doi: 10.1038/18686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy B. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt PC. In: Single Neuron Computation. McKenna T, Davis J, Zornetzer SF, editors. San Diego: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Spruston N, Sakmann B, Häusser M. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]