Abstract

This study determined the decline in oxidative capacity per volume of human vastus lateralis muscle between nine adult (mean age 38.8 years) and 40 elderly (mean age 68.8 years) human subjects (age range 25-80 years). We based our oxidative capacity estimates on the kinetics of changes in creatine phosphate content ([PCr]) during recovery from exercise as measured by 31P magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy. A matched muscle biopsy sample permitted determination of mitochondrial volume density and the contribution of the loss of mitochondrial content to the decline in oxidative capacity with age.

The maximal oxidative phosphorylation rate or oxidative capacity was estimated from the PCr recovery rate constant (kPCr) and the [PCr] in accordance with a simple electrical circuit model of mitochondrial respiratory control. Oxidative capacity was 50 % lower in the elderly vs. the adult group (0.61 ± 0.04 vs. 1.16 ± 0.147 mM ATP s−1).

Mitochondrial volume density was significantly lower in elderly compared with adult muscle (2.9 ± 0.15 vs. 3.6 ± 0.11 %). In addition, the oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume (0.22 ± 0.042 vs. 0.32 ± 0.015 mM ATP (s %)−1) was reduced in elderly vs. adult subjects.

This study showed that elderly subjects had nearly 50 % lower oxidative capacity per volume of muscle than adult subjects. The cellular basis of this drop was a reduction in mitochondrial content, as well as a lower oxidative capacity of the mitochondria with age.

Muscle and whole body maximal aerobic performance decline with age in humans (Buskirk & Hodgson, 1987; Brooks & Faulkner, 1994). The loss of muscle mass is an important contributor to this decline (Proctor & Joyner, 1997), but the role of oxidative capacity per muscle mass is less clear. Age-related changes in volume-specific oxidative capacity have been inferred from both in vitro and in vivo measurements of muscle oxidative properties. For example, a decline in marker enzyme activity in muscle biopsies and a slower recovery rate from exercise indicate a reduced capacity for oxidative phosphorylation in elderly muscle (Coggan et al. 1993; McCully et al. 1993; Papa, 1996). However, it is unclear how these relative measures of aerobic properties relate to the muscle's capacity for oxidative phosphorylation. What is needed is a quantitative measure of oxidative capacity to determine the contribution of muscle properties to the decline in maximal oxygen consumption and aerobic performance with age.

Two tools have the potential for allowing a determination of muscle oxidative capacity in vivo. First are magnetic resonance (MR) methods that make possible non-invasive assessment of the change in muscle energetics in vivo. These methods allow us to measure changes in metabolites, such as creatine phosphate (PCr), during muscle activity. The greater change in [PCr] for a given steady-state exercise rate normalized to muscle mass in the elderly indicates a lower muscle oxidative capacity compared with the young (Coggan et al. 1993; McCully et al. 1993). We can now use the recovery of [PCr] after exercise to quantify the change in oxidative properties of muscle with age (Blei et al. 1993; Walter et al. 1997).

The second tool allowing us to determine oxidative capacity in muscle is the model of the control of oxidative phosphorylation presented by Meyer et al. (Meyer, 1988, 1989; Paganini et al. 1997). These workers have shown that a simple electrical circuit model links the change in [PCr] with exercise to the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation rate. Human and rodent studies have shown that the rate constant describing [PCr] recovery following exercise (kPCr) is proportional to the oxidative enzyme activity of muscle (McCully et al. 1993; Paganini et al. 1997). At full PCr depletion (Δ[PCr]), the model predicts that the mitochondria should be working at their oxidative capacity. Thus the PCr level and the dynamics following exercise provide a means of estimating muscle oxidative capacity in vivo.

The purpose of this study was to determine the oxidative capacity of muscle and how it differs between adult and elderly groups. We evaluated muscle properties using 31P MR spectroscopy during electrical stimulation and recovery of the vastus lateralis muscle. Specifically, the [PCr] dynamics during recovery was used to quantify the kPCr of each subject and, along with [PCr] at rest ([PCr]rest), was used to estimate oxidative capacity. This estimate was compared with an independent method based on mitochondrial volume density determined from muscle biopsies taken at the site of the MR acquisition. Our main finding was a 50 % reduction in oxidative capacity between the adult and elderly groups, half of which was due to reduced mitochondrial volume density and the remaining half to reduced mitochondrial function.

METHODS

Subjects

An adult group consisted of nine subjects (6 males, 3 females) ranging in age from 25 to 48 years (38.8 ± 7.9 years, mean ±s.d.). An elderly group consisted of 40 subjects (18 male, 22 female) ranging in age from 65 to 80 years (68.8 ± 5.9 years). Body mass was not significantly different between the two groups (adult 69.8 ± 2.8 kg, elderly 72.1 ± 2.2 kg, means ±s.e.m.). Subjects were not involved in a formal exercise training programme, were in good health and had no significant cardiac, neurological or musculoskeletal disease. Nine of the elderly female subjects were receiving hormone replacement therapy. Subjects’ activity profiles ranged from housework, yardwork, and occasional walks to aerobic activities several times per week. All subjects voluntarily gave informed, written consent. The study was undertaken in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Stimulation and recovery protocol

Experimental protocol

We used the dynamics of [PCr] and pH during stimulation to estimate glycolytic H+ production and during aerobic recovery from exercise to measure ATP supply and estimate oxidative capacity. Spectral data were collected at 6 s intervals over an 8 min period using the following protocol.

Control period (60 s, 10 spectra): baseline data were obtained during resting conditions to establish initial metabolite peak areas and pH under partially saturating nuclear MR data acquisition conditions.

Stimulation period (120 s, 20 spectra): a 3 Hz electrical stimulation period was used to decrease [PCr]. Glycolytic H+ production was determined from the [PCr] and pH changes as previously reported (Conley et al. 1997, 1998).

Aerobic recovery (300 s, 50 spectra): upon cessation of stimulation, the extent and time course of the aerobic PCr recovery was followed and used as the basis of the oxidative phosphorylation determinations.

Muscle stimulation

We activated the quadriceps muscles by transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the femoral nerve, as previously described (Blei et al. 1993; Conley et al. 1997, 1998). Briefly, a 3 cm × 4 cm cathode was placed over the femoral nerve just below the inguinal ligament in the femoral triangle, and a 7.5 cm × 12.5 cm anode was placed on the posterolateral hip. We used EMG to monitor muscle activation and establish the maximal stimulating voltage. The active electrode was placed over the belly of the vastus lateralis muscle and the reference electrode at the tendon just above the patella. The application of a series of single stimulations (duration 150-350 μs) of increasing intensity allowed us to determine the intensity that evoked the maximum EMG response for each subject. During the experiment, stimulations of supramaximal intensity (1.3-1.5 times maximal) were delivered for 2 min at 3 Hz.

Magnetic resonance determinations

A General Electric 1.5 T Signa imager/spectrometer was used for all studies. A 9 cm diameter surface coil tuned to the phosphorus frequency (25.9 MHz) was placed over the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh. The B1 field homogeneity was optimized by off-resonance proton shimming on the muscle water peak. The unfiltered PCr line-width (full width at half-maximal height) was typically 4-8 Hz. Each subject had a high resolution control 31P MR spectrum of the resting muscle taken under conditions of fully relaxed nuclear spins (16 free-induction decays (FID) with a 16 s interpulse delay) using a spectral width of ±1250 Hz and 2048 data points. Measurement of changes in [PCr], [ATP], [Pi] and pH during and following stimulation were made using a standard 1 pulse experiment with partially saturated nuclear spins (1.5 s interpulse delay). Four FIDs were averaged per spectrum, yielding a time resolution of 6 s. These rapidly acquired spectra typically had a 40:1 signal-to-noise ratio for the PCr peak. No attempt was made to gate the signal acquisition to the electrical stimulation, but artifacts due to movement were reduced by stabilizing the limb during the contractions. The FIDs were Fourier-transformed into spectra and analysed as previously described (Blei et al. 1993; Conley et al. 1997). The area corresponding to each spectral peak was expressed relative to the ATP peak, which was calibrated using the ATP concentration measured in the muscle. For missing [ATP] values, literature values were used for the two youngest subjects (< 30 years old; Harris et al. 1975) or the average values for each group. The free ADP level was calculated from the creatine kinase equilibrium (Lawson & Veech, 1979) corrected for the effects of pH (Golding et al. 1995). The chemical shift (δ) of the Pi peak relative to PCr (-2.54 parts per million (p.p.m.)) referenced to phosphoric acid (0 p.p.m.) was used to calculate pH (Taylor et al. 1983).

Calculations

The linear model of oxidative phosphorylation described by Meyer et al. (Meyer, 1989; Foley & Meyer, 1993; Paganini et al. 1997) was used. The first step in using this model is to fit the recovery of [PCr] from exercise to the resting level using a monoexponential equation taken from a resistance-capacitance (RC) circuit:

| (1) |

where the levels at time t and the beginning of recovery are [PCr]t and [PCr]0, respectively; kPCr is the rate constant of PCr recovery (kPCr = 1/time constant (τ)) and Δ[PCr] =[PCr]rest–[PCr]0. The initial rate of change of PCr is given by the following derivative of eqn (1):

| (2) |

The instantaneous rate at t = 0 reduces the equation to:

| (3) |

This equation predicts the oxidative phosphorylation rate (d[PCr]/dt) at any given Δ[PCr] based on the characteristic kPCr of each muscle. To estimate oxidative capacity, we assumed that [PCr]rest reflects the maximum range of change in Δ[PCr] (i.e. Δ[PCr]max =[PCr]rest– 0). Thus, an estimate of the oxidative capacity of the muscle comes from the characteristic kPCr of that muscle and [PCr]rest in eqn (3).

Oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume

The average oxidative capacity of mitochondria has been measured as the whole body maximum oxygen consumption divided by the total mitochondrial volume of the musculature (see Hoppeler, 1990). This method yielded a oxidative capacity of between 4 and 5 ml O2 min−1 (ml mitochondria)−1, which averages 27 μmol ATP min−1 (ml mitochondria)−1 for a P/O2 (phosphorylation to oxidation ratio of mitochondrial respiration) of 6. An independent estimate of the maximal rate of mitochondrial respiration comes from isolated mitochondrial studies (Schwerzmann et al. 1989). Since muscle oxidizes>85 % pyruvate at the maximal oxygen uptake rate (V̇O2,max, see Brooks & Mercier, 1994; Connett & Sahlin, 1996), the substrate pair best suited for comparison with in vivo mitochondria is pyruvate and malate (Schwerzmann et al. 1989). This substrate pair yielded a maximum oxidative rate of 17 μmol ATP min−1 (ml mitochondria)−1 (2.7 ml O2 min−1 (ml mitochondria)−1) at 30°C, when corrected for a P/O2 of 6 and 0.7 ml H2O per ml tissue (Sjøgaard & Saltin, 1982). Correcting the rate to 37°C (assuming a doubling of rate with each 10°C, i.e. Q10 = 2) yields 27 μmol ATP min−1 (ml mitochondria)−1. Thus isolated mitochondria and in vivo mitochondria have the same maximum oxidative rate per mitochondrial volume. This value is used to estimate muscle oxidative capacity based on mitochondrial volume density.

Glycolysis

We have previously shown how to quantify glycolytic ATP production based on the H+ generated during muscle stimulation (Conley et al. 1998). The glycolytic H+ generated was quantified from the change in PCr and pH through stimulation:

| (4) |

where ΔpH and ΔPCr are the changes in pH and PCr during exercise, βtot is the buffering capacity of the individual's muscle, and γ is the proton stoichiometric coefficient of the coupled Lohman reaction, as previously described (Conley et al. 1997; Kushmerick, 1997). Glycolytic ATP synthesis is related to H+ production by the ATP/H+ stoichiometry of glycogenolysis and glycolysis (i.e. 1.5 ATP/H+).

Tissue analysis

We used the Bergstrom needle biopsy technique to acquire tissue from the mid-thigh level of the right vastus lateralis muscle. A 25 mg piece was immersion fixed in glutaraldehyde, processed for electron microscopy, and morphometrically analysed as previously described (Hoppeler et al. 1981). Any remaining tissue was freeze-clamped immediately after collection and stored at -80°C prior to HPLC metabolite analysis (Wiseman et al. 1992). Metabolite concentrations were expressed per volume of cell water by assuming 0.7 ml intracellular water (g muscle mass)−1, as found for human muscle biopsy samples (Sjøgaard & Saltin, 1982).

Statistics

We used Student's two-tailed paired and unpaired t tests to determine differences between groups and standard linear regression methods for analysis of correlations. Statistical significance was defined at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

We took three steps to achieve the goal of evaluating the change in oxidative capacity with age. First, 31P MR spectroscopy was used to quantify the metabolite levels in resting muscle, during stimulation and through recovery. Second, we used the PCr recovery from exercise to estimate the muscle oxidative capacity. Finally, we evaluated the contribution of a loss of mitochondrial volume density and mitochondrial function to the change in oxidative capacity with age.

Metabolite levels and dynamics

Our first step was to quantify the metabolite levels using a combination of HPLC analysis of muscle biopsies and the peak areas in the 31P MR spectra.

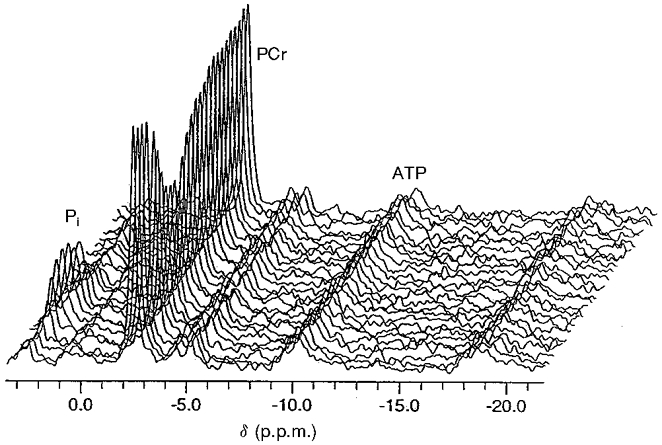

Resting levels

A stack plot of the dynamics of PCr and ATP through recovery is shown for a typical experiment in Fig. 1. The metabolite peak areas and concentrations shown in Table 1 were similar in the muscles of the two groups with the exception of a significantly higher [PCr]/[ATP] in the elderly vs. adult groups. There was good agreement between the [PCr]/[ATP] determined by MR vs. that determined by HPLC from biopsies at the same location in elderly muscle (P > 0.28, paired t test, n = 24). We found no significant change in [PCr] with age, but [ATP] did decline significantly at a rate of 0.048 mM year−1.

Figure 1. Stack plot of every third 31P NMR spectrum during rest, stimulation and recovery in an elderly individual.

The abscissal scale references PCr to a chemical shift (δ) of -2.54 p.p.m. Pi, inorganic phosphate.

Table 1.

Metabolite levels determined by HPLC from muscle biopsies of the vastus lateralis and by MR of the same muscle

| Metabolite | Adult | Elderly | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| [ATP] (mM) | 6.8 ± 0.6 (3) | 5.9 ± 0.2 (32) | 8.2 |

| Total [Cr] (mM) | 43.4 ± 5.2 (2) | 46.7 ± 1.1 (31) | 42 |

| [PCr] (mM) | 26.7 ± 3.5 (3) | 26.0 ± 1.0 (32) | 32 |

| [PCr]/[ATP] | — | 4.30 ± 0.2 (32) | 3.9 |

| MR [PCr]/[ATP] | 4.00 ± 0.11 (9) | 4.53 ± 0.10 (38)* | — |

| MR [P1]/[ATP] | 0.52 ± 0.03 (9) | 0.62 ± 0.03 (38) | — |

| MR [PDE]/[ATP] | 0.75 ± 0.14 (9) | 0.76 ± 0.05 (38) | — |

Values are means ± S.E.M. with the sample size given in parentheses. Literature values are from Harris et al. (1974) for subjects 18–30 years old. PDE, phosphodiester.

Significant difference between adult and elderly groups.

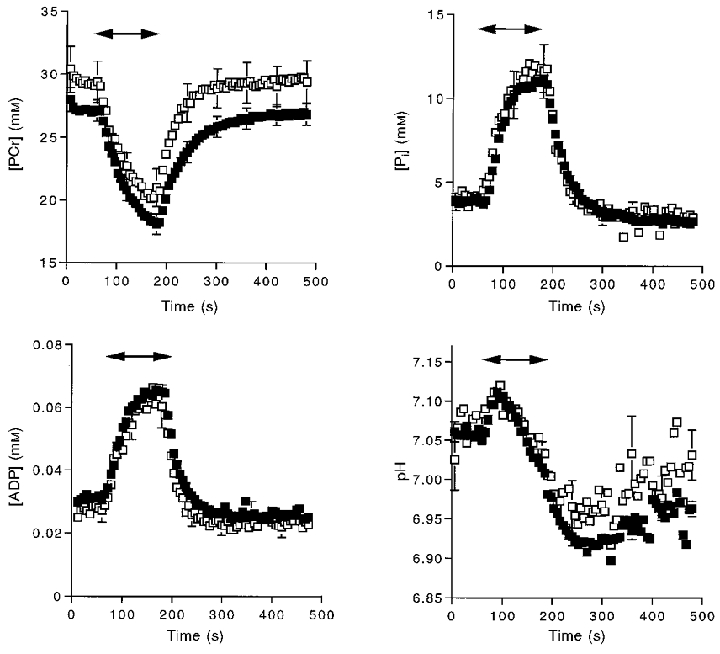

Dynamics

The changes in metabolite levels and pH during stimulation and recovery for the two groups are shown in Fig. 2. The metabolite and pH levels at rest, at the end of stimulation and the change with stimulation for each group are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2. Metabolite levels as a function of time during the stimulation and recovery experiment.

Symbols indicate means and error bars indicate s.e.m. Double-headed arrows indicate the duration of stimulation. □, adult subjects; ▪, elderly subjects.

Table 2.

Metabolite levels determined by MR at rest and at the end of stimulation

| Quantity | Group | Rest | Stimulation end | Stimulation–Rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [PCr] (mM) | Adult | 29.24 ± 1.60 | 20.44 ± 1.32 | −8.80 ± 1.37* |

| Elderly | 27.11 ± 0.88 | 18.24 ± 0.79 | −8.87 ± 0.38* | |

| [P1] (mM) | Adult | 4.32 ± 0.69 | 11.62 ± 1.78 | 7.30 ± 1.32* |

| Elderly | 3.87 ± 0.22 | 11.12 ± 0.74 | 7.24 ± 0.56* | |

| pH | Adult | 7.063 ± 0.011 | 7.040 ± 0.016 | −0.022 ± 0.022 |

| Elderly | 7.058 ± 0.006 | 7.020 ± 0.009 | −0.036 ± 0.011* | |

| [ADP] (mM) | Adult | 0.030 ± 0.004 | 0.062 ± 0.007 | 0.032 ± 0.005* |

| Elderly | 0.031 ± 0.0015 | 0.065 ± 0.002 | 0.033 ± 0.002* |

Values are means ± S.E.M. The sample size was 9 for the adult group and 40 for the elderly group.

Significant difference between conditions.

Oxidative phosphorylation rate

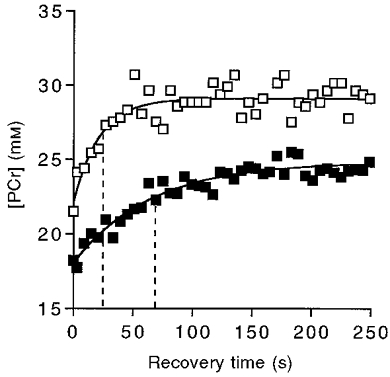

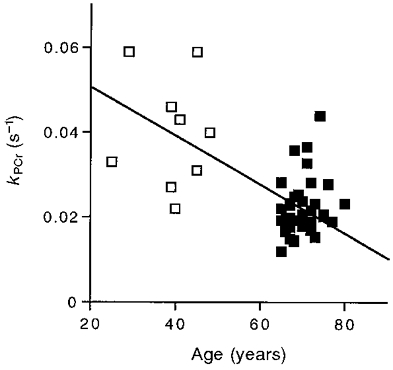

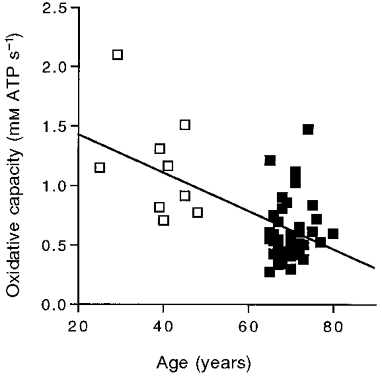

Our next step was to determine the oxidative phosphorylation rate and estimate the oxidative capacity. We compared the initial rate of oxidative phosphorylation estimated from the monoexponential fit of the PCr recovery to that measured directly. The time constant (τ) of the monoexponential fit of this recovery is shown for adult and elderly individuals in Fig. 3 (vertical dashed lines). The rate constant (kPCr) is the inverse of τ, and along with the Δ[PCr] achieved at the end of exercise (i.e. Δ[PCr] =[PCr]rest–[PCr]stim), was used to estimate the initial recovery rate according to eqn (3). Our direct measurement of oxidative ATP synthesis was based on initial change in [PCr] (0.23 ± 0.02 mM ATP s−1) minus the glycolytic ATP synthesis (0.033 ± 0.004 mM ATP s−1), which we have found persists for a few seconds into recovery (Crowther et al. 1999). The initial recovery rate estimated from the monoexponential PCr recovery (eqn (3); 0.19 ± 0.012 mM ATP s−1) did not significantly differ from the direct measurement of oxidative ATP synthesis (0.20 ± 0.017 mM ATP s−1; P = 0.5, paired t test, n = 48). The change in kPCr with age is shown in Fig. 4 to significantly decrease between 25 and 80 years. The product of kPCr and [PCr]rest yields the oxidative capacity in eqn (3). This calculation reveals a 50 % lower oxidative capacity in the elderly (0.61 ± 0.04 mM ATP s−1, n = 32) vs. the adult group (1.16 ± 0.147 mM ATP s−1, n = 9). Figure 5 shows the decline in oxidative capacity with age.

Figure 3. [PCr] recovery following stimulation.

Continuous lines are monoexponential fits to the data for an adult (□) and an elderly (▪) subject. The vertical dashed lines denote the time constant for each recovery.

Figure 4. [PCr] recovery rate constant (kPCr) as a function of age.

The line represents the regression equation: y = -0.0005x = 0.057 (r2 = 0.35). Symbols as in Fig. 2.

Figure 5. Oxidative capacity as a function of age.

The line represents the regression equation: y = -0.017x = 1.777 (r2 = 0.34). Symbols as in Fig. 2.

Oxidative and mitochondrial properties vs. age

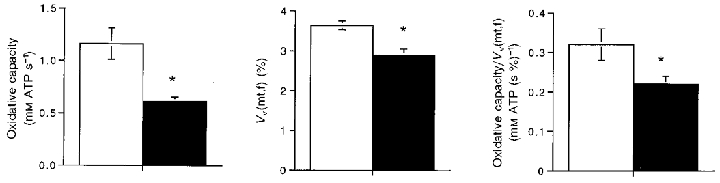

Our final step was to evaluate the structural basis for the decline in oxidative capacity with age by determining the mitochondrial volume density (VV(mt,f)) from biopsies taken at the same site as the MR determinations. The two groups significantly differed in VV(mt,f), oxidative capacity, and oxidative capacity/VV(mt,f) as shown in Fig. 6. A significant negative correlation of oxidative capacity/VV(mt,f) with age (P = 0.01) confirmed the loss of mitochondrial function apparent between the two groups in Fig. 6. These results indicate that accompanying the loss of oxidative capacity in elderly muscle is a reduced VV(mt,f) and lower mitochondrial function. Thus reductions in both the quantity and quality of mitochondria underlie the loss of oxidative capacity between adult and elderly muscle.

Figure 6. Oxidative capacity, mitochondrial volume density (VV(mt,f)) and oxidative capacity/VV(mt,f) in the adult and elderly groups.

Values are means ±s.e.m. and asterisks denote significant difference from the adult values. □, adult subjects; ▪, elderly subjects.

A direct comparison between the mitochondrial volume and MR estimates of oxidative properties is possible with the mitochondrial oxidative capacity in vivo (0.45 μmol ATP s−1 (ml mitochondria)−1; see Methods for details). The oxidative capacity estimated from VV(mt,f) yielded no significant difference from that estimated by the MR method for the adult subjects (0.98 ± 0.03 vs. 1.14 ± 0.13 mM ATP s−1; P = 0.32, paired t test, n = 5). This comparison indicates that on average the MR method provides an estimate of oxidative capacity similar to that based on the muscle mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity of mitochondria in vivo.

A similar comparison of methods for the elderly subjects shows that the estimate based on VV(mt,f) was significantly higher than the MR value for the elderly subjects (0.78 ± 0.04 vs. 0.61 ± 0.04 mM ATP s−1; P = 0.002, n = 27). These results confirm the lower oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume for the elderly vs. adult muscle shown in Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine how oxidative capacity changes with age in muscle. To achieve this goal, we estimated oxidative capacity per muscle volume using MR measurements of [PCr] dynamics following exercise and compared these estimates to the mitochondrial content of matched biopsy samples. The end result was a measure of the decline in oxidative capacity between adult and elderly muscle and the contribution of the loss of mitochondrial content vs. function to this decline with age.

Oxidative recovery

A clear indication of the change in oxidative properties between adult and elderly muscle is the twofold difference in the time course of PCr recovery from exercise shown in Fig. 3. The rate constant of recovery (kPCr, the inverse of τ, shown as the dashed lines in Fig. 3) represents this oxidative response time. The initial phosphorylation rate predicted from kPCr agrees with a direct measure of the PCr recovery rate. The rate constant also provides a measure of oxidative properties when the control of oxidative phosphorylation in muscle is viewed analogously to an electrical circuit (Meyer, 1988, 1989; Paganini et al. 1997). The rate constant (k) of an electrical circuit is characteristic of the resistance (R) and capacitance (C) (where, 1/k =RC). In the analogous circuit in muscle, mitochondria set the ‘resistance’ and total creatine sets the ‘capacitance’. Since the total creatine (C in the muscle circuit) did not differ between the two groups (Table 1), kPCr will vary with the mitochondrial content of muscle (R in the muscle circuit) and therefore with oxidative properties.

Two results support the notion that kPCr is a characteristic of the oxidative properties of mitochondria in muscle. First, kPCr is independent of Δ[PCr] to 50 % PCr depletion in a number of rodent and human muscles (Paganini et al. 1997; Walter et al. 1997). Only at low pH levels does kPCr vary in a given muscle, because [H+] significantly affects the creatine kinase equilibrium thereby altering the link between Δ[PCr] and oxidative phosphorylation (Paganini et al. 1997; Walter et al. 1997). Over the pH values found in this experiment (7.1-6.9; Table 2), however, the rate constant of PCr recovery (kPCr) remains constant. Second, kPCr is proportional to oxidative enzyme activity in both human and animal muscle (McCully et al. 1993; Paganini et al. 1997), which indicates that kPCr is determined by the mitochondrial properties of the muscle. In support of this link is the parallel decline of kPCr and oxidative enzyme activity with age in human vastus lateralis (McCully et al. 1993). Such an age-related loss of oxidative properties is indicated in this study by the significant reduction in kPCr with age (Fig. 4).

Can we estimate oxidative capacity of the muscle knowing kPCr? The maximum oxidative phosphorylation rate is expected when the signal activating mitochondrial respiration is maximal. The electrical analog model shown in eqn (3) predicts a maximum rate when Δ[PCr] is maximal. Since [PCr]rest sets the upper limit, Δ[PCr]max is reached when [PCr] drops to zero. Richardson et al. (1995) measured [PCr] at the oxidative capacity using a procedure to exercise only the quadriceps muscles while simultaneously measuring the oxygen consumption across the exercising leg up to the maximum oxygen consumption of the limb. They found that [PCr] was close to zero (i.e. 3 mM) at the highest aerobic work rate. Confirmation that the muscles were working at or close to their oxidative capacity came from the ADP levels in the muscles at the highest workloads. The [PCr], [ATP] and pH levels at V̇O2,max result in [ADP] above 230 μM (creatine kinase equilibrium constant, 166 M−1; Lawson & Veech, 1979). This [ADP] is> 90 % of the level needed to achieve maximum oxygen consumption in isolated mitochondria (Mootha et al. 1997), which indicates that the quadriceps were operating close to the mitochondrial maximum in the experiment of Richardson et al. (1995). Thus the maximum Δ[PCr] possible during aerobic exercise is the range represented by [PCr]rest and zero. We can therefore estimate oxidative capacity from the product of [PCr]rest and kPCr according to eqn (3). Since we found no change in [PCr]rest with age, the oxidative capacity will vary in proportion to kPCr (Fig. 5).

Muscle vs. mitochondrial oxidative capacity

Does this estimate of the muscle's oxidative capacity reflect the true capacity of mitochondria? To answer this question, an independent measure of mitochondrial oxidative capacity is needed to evaluate our MR estimates. The maximum oxygen consumption of mammalian mitochondria has been measured in vivo in running animals at their aerobic capacity (see Hoppeler, 1990 and Methods). These data provide an independent measure of oxidative capacity that can be derived from VV(mt,f). A direct comparison between these methods for the adult subjects in this study revealed no significant difference between the mitochondrial and MR estimates of the oxidative capacity (0.98 ± 0.03 vs. 1.14 ± 0.13 mM ATP s−1, respectively; P = 0.32, paired t test, n = 5). In contrast, the mitochondrial value was significantly greater than the MR estimate in the elderly subjects (0.78 ± 0.04 vs. 0.61 ± 0.04 mM ATP s−1, respectively; P = 0.002, n = 27). These results indicate a lower oxidative capacity of elderly compared with adult mitochondria and suggest that the loss of muscle oxidative capacity per muscle volume reflects not only mitochondrial volume loss but also the reduced capacity of the mitochondria themselves.

Adult vs. elderly oxidative capacity

The lower oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume of the elderly vastus lateralis compared with the adult group shown in Fig. 6 is consistent with a lower mitochondrial oxidative enzyme activity with age. The 30 % difference in oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume seen for our subject groups is similar to the 30-40 % reductions in both mitochondrial respiration rates (Trounce et al. 1989; Cooper et al. 1992; Boffoli et al. 1994) and mitochondria-specific oxidative enzyme activities (Cooper et al. 1992; Boffoli et al. 1994; Rooyackers et al. 1996) that have been demonstrated in old vs. younger subjects. However, Papa (1996) showed that this activity loss is not equally shown by all enzymes, which may explain the failure to find an age-related decline in oxidative capacity using single enzyme assays of muscle biopsy tissue (e.g. Houmard et al. 1998). In addition, the large variance inherent in the individual decline in oxidative capacity (Fig. 5) means that the age-related change may be missed in small sample sizes or in groups close in age.

The reduction in mitochondrial function with age may be caused by a number of factors, such as mitochondrial DNA mutations (Cooper et al. 1992; Boffoli et al. 1994; Michikawa et al. 1999), oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species (Papa, 1996), or reduced synthesis of mitochondrial proteins (Rooyackers et al. 1996). Brierly et al. (1997a,b) suggest that the reduction in mitochondrial function seen in elderly subjects is not directly caused by an ageing process per se. They report that there was no difference in mitochondrial respiration rates between endurance-trained subjects whether young or old. This suggests that reduced mitochondrial function in the sedentary elderly may be due to physical inactivity rather than ageing itself. However, a significant decline in mitochondrial function and mitochondrial volume density was found in the study reported here (Fig. 6) despite the fact that all of our subjects were recreationally active. Thus, moderate levels of activity are not sufficient to eliminate either the loss of mitochondrial oxidative capacity or of mitochondrial content with age. The end result is a decline of nearly half of the muscle oxidative capacity between adults and elderly subjects due to reduced mitochondrial content as well as a significantly lower oxidative capacity per mitochondrial volume.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to Elizabeth Egan, Barbara Inglin, Chris Mogadam and Rudy Stuppard for their participation in these studies. M. Elaine Cress, Greg Crowther, Martin Kushmerick, Ron Meyer and Ib Odderson provided helpful input, advice or assistance. This work was supported by the University of Washington Clinical Research Center facility grant no. M01-RR00037, Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant no. 5-P30-DK17047, and NIH grants AG-10853, AR-41928 and HL-07403.

References

- Blei ML, Conley KE, Kushmerick MJ. Separate measures of ATP utilization and recovery in human skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;465:203–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffoli D, Scacco SC, Vergari R, Solarino G, Santacroce G, Papa S. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1226:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierly EJ, Johnson MA, Bowman A, Ford GA, Reed JW, James OFW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial function in muscle from elderly athletes. Annals of Neurology. 1997a;41:114–116. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierly EJ, Johnson MA, James OFW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial involvement in the ageing process. Facts and controversies. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1997b;174:325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA, Mercier J. Balance of carbohydrate and lipid utilization during exercise: the ‘cross-over’ concept. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;76:2253–2261. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Skeletal muscle weakness in old age: underlying mechanisms. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1994;26:432–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskirk ER, Hodgson JL. Age and aerobic power: the rate of change in men and women. Federation Proceedings. 1987;46:1824–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan AR, Abduljalil AM, Swanson SC, Earle MS, Farris JW, Mendenhall LA, Robitaille PM. Muscle metabolism during exercise in young and older untrained and endurance-trained men. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75:2125–2133. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.5.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Blei ML, Richards TL, Kushmerick MJ, Jubrias SA. Activation of glycolysis in human muscle in vivo. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C306–315. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Kushmerick MJ, Jubrias SA. Glycolysis is independent of oxygenation state in stimulated human skeletal muscle in vivo. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:935–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.935bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connett RJ, Sahlin K. Control of Glycolysis and Glycogen Metabolism. Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 870–911. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JM, Mann VM, Schapira AHV. Analysis of mitochondrial respiratory chain function and mitochondrial DNA deletion in human skeletal muscle: effect of aging. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1992;113:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90270-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther GJ, Carey MF, Kemper WF, Conley KE. Getting at the crux of glycolytic flux: Direct measurement of glycolysis during and after exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1999;31:S242–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Foley JM, Meyer RA. Energy cost of twitch and tetanic contractions of rat muscle estimated in situ by gated 31P NMR. NMR in Biomedicine. 1993;6:32–38. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940060106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding EM, Teague WE, Jr, Dobson G P. Adjustment of K’ to varying pH and pMg for the creatine kinase, adenylate kinase and ATP hydrolysis equilibria permitting quantitative bioenergetic assessment. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1995;198:1775–1782. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.8.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, Hultman E, Kaijser L, Nordesjo L-O. The effect of circulatory occlusion on isometic exercise capacity and energy metabolism of the quadriceps muscle in man. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical Laboratory Investigation. 1975;35:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, Hultman E, Nordesjo L-O. Glycogen, glycolytic intermediates and high-energy phosphates determined in biopsy samples of musculus quadraceps femoris of man at rest. Methods and variance of values. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical Laboratory Investigation. 1974;33:109–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppeler H. The different relationship of VO2max to muscle mitochondria in humans and quadrupedal animals. Respiration Physiology. 1990;80:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(90)90077-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppeler H, Mathieu O, Krauer R, Claassen H, Armstrong RB, Weibel ER. Design of the mammalian respiratory system. VI. Distribution of mitochondria and capillaries in various muscles. Respiration Physiology. 1981;44:87–111. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(81)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard JA, Weidner ML, Gavigan KE, Tyndall GL, Hickey MS, Alshami A. Fiber type and citrate synthase activity in the human gastrocnemius and vastus lateralis with aging. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;85:1337–1341. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ. Multiple equilibria of cations with metabolites in muscle bioenergetics. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C1739–1747. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.5.C1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JW, Veech RL. Effects of pH and free Mg2+ on the Keq of the creatine kinase reaction and other phosphate hydrolyses and phosphate transfer reactions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1979;254:6528–6537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KK, Fielding RA, Evans WJ, Leigh JS, Posner JD. Relationship between in vivo and in vitro measurements of metabolism in young and old human calf muscles. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75:813–819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. A linear model of muscle respiration explains monoexponential phosphocreatine changes. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:C548–553. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.4.C548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on total creatine content. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:C1149–1157. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.6.C1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michikawa Y, Mazzucchelli F, Bresolin N, Scarlato G, Attardi G. Aging-dependent large accumulation of point mutations in the human mtDNA control region for replication. Science. 1999;286:774–779. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha VK, Arai AE, Balaban RS. Maximum oxidative phosphorylation capacity of the mammalian heart. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:H769–775. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini AT, Foley JM, Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on mitochondrial content. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C501–510. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation changes in the life span. Molecular aspects and physiopathological implications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1276:87–105. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Joyner MJ. Skeletal muscle mass and the reduction of VO2max in trained older subjects. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;82:1411–1415. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson RS, Noyszewski EA, Kendrick KF, Leigh JS, Wagner PD. Myoglobin O2 desaturation during exercise. Evidence of limited O2 transport. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96:1916–1926. doi: 10.1172/JCI118237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooyackers OE, Adey DB, Ades PA, Nair KS. Effect of age on in vivo rates of mitochondrial protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:15364–15369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerzmann K, Hoppeler H, Kayar SR, Weibel ER. Oxidative capacity of muscle and mitochondria: correlation of physiological, biochemical, and morphometric characteristics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:1583–1587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjøgaard G, Saltin B. Extra- and intracellular water spaces in muscles of man at rest and with dynamic exercise. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;243:R271–280. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.243.3.R271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DJ, Bore PJ, Styles P, Gadian DG, Radda GK. Bioenergetics of intact human muscle. A 31P nuclear magnetic resonance study. Molecular Biology in Medicine. 1983;1:77–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trounce I, Byrne E, Marzuki S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory chain function: possible factor in ageing. Lanceti. 1989:637–639. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter G, Vandenborne K, McCully KK, Leigh JS. Noninvasive measurement of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in single human muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C525–534. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RW, Moerland TS, Chase PB, Stuppard R, Kushmerick MJ. High-performance liquid chromatographic assays for free and phosphorylated derivatives of the creatine analogues beta-guanidopropionic acid and 1-carboxy-methyl-2-iminoimidazolidine (cyclocreatine) Analytical Biochemistry. 1992;204:383–389. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]