Abstract

Intrinsic primary afferent neurons in the small intestine are exposed to distortion of their processes and of their cell bodies. Recordings of mechanosensitivity have previously been made from these neurons using intracellular microelectrodes, but this form of recording has not permitted detection of generator potentials from the processes, or of responses to cell body distortion.

We have developed a technique to record from enteric neurons in situ using patch electrodes. The mechanical stability of the patch recordings has allowed recording in cell-attached and whole cell configuration during imposed movement of the neurons.

Pressing with a fine probe initiated generator potentials (14 ± 9 mV) from circumscribed regions of the neuron processes within the same myenteric ganglion, at distances from 100 to 500 μm from the cell body that was patched. Generator potentials persisted when synaptic transmission was blocked with high Mg2+, low Ca2+ solution.

Soma distortion, by pressing down with the whole cell recording electrode, inhibited action potential firing. Consistent with this, moderate intra-electrode pressure (10 mbar; 1 kPa) increased the opening probability of large-conductance (BK) potassium channels, recorded in cell-attached mode, but suction was not effective. In outside-out patches, suction, but not pressure, increased channel opening probability. Mechanosensitive BK channels have not been identified on other neurons.

The BK channels had conductances of 195 ± 25 pS. Open probability was increased by depolarization, with a half-maximum activation at a patch potential of 20 mV and a slope factor of 10 mV. Channel activity was blocked by charybdotoxin (20 nM).

Stretch that increased membrane area under the electrode by 15 % was sufficient to double open probability. Similar changes in membrane area occur when the intestine changes diameter and wall tension under physiological conditions. Thus, the intestinal intrinsic primary afferent neurons are detectors of neurite distortion and of compression of the soma, these stimuli having opposite effects on neuron excitability.

Although recordings from mechanosensitive neurons were first made more than 40 years ago (Katz, 1950; Eyzaguirre & Kuffler, 1955), biophysical analysis of mammalian mechanosensory neurons has been hampered by the distances between physiologically relevant mechanotransducing sites, for example in skin and joints, and cell bodies in spinal ganglia. The recent identification of mechanosensitivity of neurons in the wall of the intestine (Kunze et al. 1998, 1999) provides an opportunity to record from nerve cells close to the tissues from which they draw information. In fact, both the cell body and the processes of the intrinsic primary afferent neurons (IPANs) are in the wall of the intestine, and the cell body is distorted when the gut wall contracts or is distended (Gabella & Trigg, 1974).

IPANs have a distinctive shape, referred to as Dogiel type II, and a characteristic prolonged after-hyperpolarization following the action potential, from which they have gained the electrophysiological designation AH. Dogiel type II/AH neurons in the small intestine of the guinea-pig respond with action potential discharge when the intestine is stretched (Kunze et al. 1998, 1999). The initiation of action potentials in the neurons is dependent on the opening of gadolinium-sensitive mechanosensitive channels (MSCs) in the muscle. When these channels are opened, the muscle is triggered to contract; if the channels are blocked or if muscle contraction is prevented by nicardipine or isoprenaline (isoproterenol), the response of the neurons to maintained stretch is lost (Kunze et al. 1988, 1999). Tension in the tissue that results from contraction of the muscle is conveyed to the neurons through connective tissue elements whose weakening by dispase prevents the excitation of the IPANs. The neurons also respond at the onset of a rapid stretch, even when the muscle is paralysed by nicardipine (Kunze et al. 1999).

The previous studies used mobile intracellular electrodes to record action potentials from the neuronal somas during tissue movement (Kunze et al. 1999), and registered responses that were indirect, being conveyed to the neurons through connective tissue attachments. Generator potentials were not detected. In order to investigate the initiation of neurite action potentials, and to determine whether the cell body is also mechanosensitive, we have recorded from neurons in undissociated ganglia with patch electrodes. This method has the considerable advantage over intracellular recording that the patch electrodes adhere strongly to the neurons, making it feasible to record within about 100 μm of the application of a mechanical probe, and also to use the patch electrode itself to distort the nerve cell body.

METHODS

Guinea-pigs were stunned and killed by cutting the spinal cord and exsanguination. All procedures were approved by the University of Melbourne Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee. A 1–2 cm long segment of the proximal duodenum was removed and placed in a recording dish filled with oxygenated physiological saline of the following composition (mM): NaCl, 118.1; KCl, 4.8; NaHCO3, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.0; MgSO4, 1.2; glucose, 11.1; CaCl2, 2.5; which was kept at room temperature (17-20°C) during dissection, but which was heated to 35–37°C during recording. Hyoscine (1 μm) plus either nicardipine (1 μm) or isoprenaline (1 μm) was added to the superfusate to block spontaneous muscle movement. The myenteric plexus was exposed by dissecting away the mucosa, submucosal plexus and circular muscle and the preparation was mounted in a transparent recording dish on the stage of an inverted microscope. The surface of one ganglion was exposed to 0.01-0.02 % protease type XIV (http://www.sigma-aldrich.com) in physiological saline, and the upper surfaces of neurons were cleaned by sweeping with a hair over a portion of the ganglion (Gola et al. 1992). Conventional single channel and whole cell patch clamp recordings were made. Electrodes were filled with a K+-rich saline (composition (mM): KCl, 140; NaCl, 10; MgCl2, 1; CaCl2, 0.1; Hepes, 10; BAPTA, 10; pH 7.4) and had tip resistances of 4–10 MΩ in saline. The concentration of free Ca2+ in the presence of BAPTA and Mg2+ was calculated using Maxchelator (Bers et al. 1994; http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/). Most seals (1-20 GΩ) formed spontaneously after the pipette contacted the soma, with others requiring only gentle suction, which was released after the seal was obtained.

Signals were filtered at 2 or 10 kHz, amplified and digitized at 5–25 kHz, stored on computer and analysed off-line. In all recordings, outward membrane current is displayed as upward going. The mean number of open channels (NPo) was calculated as the sum of the proportions of time that 1, 2, n channels were open (Gola et al. 1990) or as the time-averaged current divided by the unitary current (Sigurdson et al. 1987). N was estimated as the maximum number of coincident openings seen when a high probability of opening (Po) was evoked by membrane depolarization.

In whole cell configuration, receptive sites were sought by probing the preparation with a small polished glass probe (20-80 μm rounded tip) or a fine hair. The probes were pushed vertically down onto the tissue by using a calibrated hydraulic micromanipulator.

Stretch sensitivity of channels in patches was tested by applying pressure via the patch pipette; pressure was measured via a transducer connected to suction syringe using a T-piece. The pressure transducer was calibrated to zero by opening the port to the atmosphere.

Data are given as means ± standard deviation, or as median and range.

RESULTS

Whole cell recordings were made from 64 myenteric IPANs (AH neurons) that were identified by the distinct calcium-dependent hump on the descending phase of the action potential; the characteristics observed in whole cell recordings were similar to those recorded previously with intracellular electrodes (Schutte et al. 1995; Clerc et al. 1998). Prolonged after-hyperpolarizations (AHPs), lasting 2 s or more, were observed in these neurons following an action potential volley. Four IPANs were filled with 0.2 % biocytin, which confirmed their identity as multipolar, Dogiel type II neurons. Resting membrane potentials and input resistances were not affected by either agent used to prevent muscle movement; in the presence of isoprenaline these were -60 ± 7 mV and 346 ± 200 MΩ (n= 14) and in the presence of nicardipine they were -62 ± 8 mV and 354 ± 183 MΩ (n= 17). These values are similar to values (-61 ± 9 mV and 310 ± 178 MΩ) reported for AH neurons in the guinea-pig duodenum recorded using intracellular electrodes (Clerc et al. 1998).

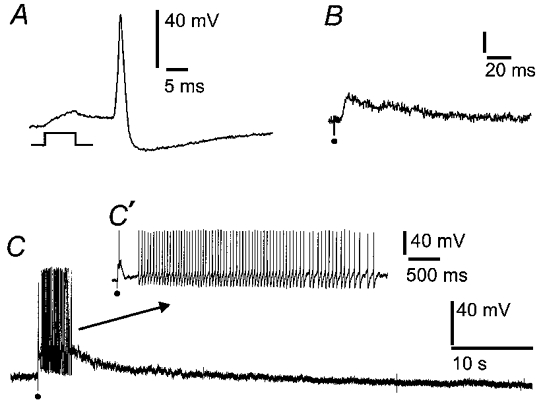

Whole cell recordings were also made from S neurons and revealed characteristics similar to those reported with intracellular electrodes (Fig. 1). These neurons had narrow action potentials with monophasic repolarizations that were not followed by prolonged AHPs. Fast excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) were recorded in S neurons and slow EPSPs were recorded in both S and AH neurons (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Whole cell patch electrode recordings of action potentials and synaptic potentials from neurons in intact myenteric ganglia.

The records are from S neurons whose surfaces were exposed by mild protease treatment, leaving the myenteric ganglia, including synaptic connections with the neurons, intact. A, action potential evoked by a brief depolarizing current passed through the recording electrode. B, fast excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) elicited by a single electrical pulse applied to a connecting nerve strand, at the dot. C, slow EPSP in response to a volley of stimuli (10 Hz for 1 s) applied to a connecting nerve strand, at the dot. The slow EPSP lasts about 10 s and has triggered a burst of action potentials, shown on an expanded time scale in C′.

Mechanical stimulation of processes

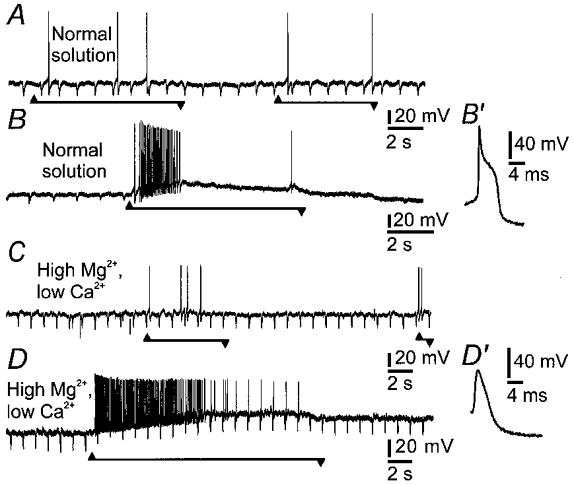

Action potentials and/or depolarizing responses were evoked by pressing on the surface of the same ganglion that contained the cell body from which recordings were made. Whole cell recordings were from neuron somas in the cleaned part of a ganglion (see Methods) and receptive sites (locations where pressing evoked action potentials) were mapped by pressing to a depth of 25 μm for 1–3 s, with a small glass probe (20-80 μm rounded tip) or a hair, on uncleaned regions in and around the ganglion. Seventeen of thirty-one AH neurons responded with one or more action potentials which ceased before the stimulus was removed (Fig. 2). Greater numbers of action potentials were evoked when the probe was moved to one side by 20–30 μm while pressing down (Fig. 2B). There were usually only one or two receptive sites per neuron; the majority of the sites tested gave no response. The number of spikes per response ranged between neurons from 1 to 32 (median 2.5) and durations of bursts of action potentials ranged from 0.08 to 5.6 s (median 0.8). Repeat responses were evoked with repeated pressing on the same receptive site. Mechanosensitive responses were elicited equally in the presence of each of the agents used to quell muscle movement, isoprenaline (8/14 neurons) or nicardipine (9/17 neurons).

Figure 2. Excitation of intrinsic primary afferent neurons (IPANs) in response to mechanical force applied to a process is independent of synaptic transmission.

A, action potentials, recorded by a patch electrode in whole cell mode, evoked by pressing on the ganglion with a hair at a distance of 200 μm from the cell body of the AH neuron. Note that there is a small depolarization just after the onset of the pressure. Onset of pressing is at the upward arrowhead and offset is at the downward arrowhead. B, depolarizing potential and action potentials evoked by pressing at the receptive site and moving the probe laterally. After synaptic blockade with high Mg2+ (10 mm) and low Ca2+ (0.25 mm), responses to pressing (C) and stretching (D) were not diminished. In normal solution there was a hump on the repolarizing phase of the action potential (B′) which was abolished in the high Mg2+, low Ca2+ solution (D′). Soma input resistance was monitored by brief hyperpolarizing deflections that were evoked by intracellular injection of negative current pulses. Soma input resistance did not change during the depolarizing potential in high Mg2+ and low Ca2+ (D). However, as shown in B, it was reduced following action potentials in normal solution, due to the post-spike, Ca2+-dependent, AH current.

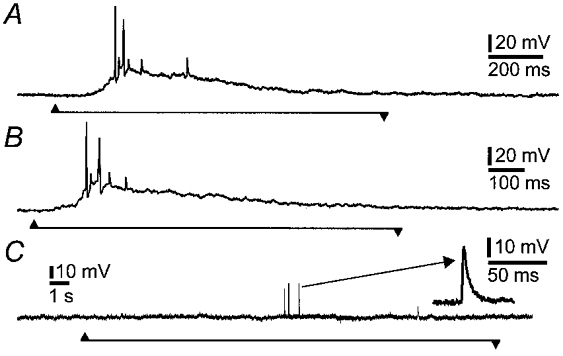

Depolarization (14 ± 9 mV) occurred during application of the probe in 15 of the 17 neurons that responded with action potentials (Fig. 3). The first action potential occurred after the onset of the depolarization, but firing ceased before the membrane had repolarized. Three of the 14 neurons that did not respond with action potentials to 25 μm probing gave depolarizing responses. Moreover, when the depth of probing was less than about 20 μm, neurons that had responded to a 25 μm probe with action potentials showed depolarizations that were subthreshold for eliciting spikes. Input resistances, measured by injecting small current steps via the electrode, were apparently unaltered during the depolarization, confirming the neurite origin of responses to pressure. In four neurons in which subthreshold depolarizations were evoked by probing the ganglion surface, input resistances were 352 ± 53 MΩ before probing and 349 ± 61 MΩ during the depolarization.

Figure 3. Depolarizing potentials evoked by probing close to an IPAN and action potentials evoked by probing at a greater distance.

A and B, repeatable depolarizing potentials, action potentials and proximal process potentials were evoked by pressing with a hair on the ganglion 150 μm from the soma. C, pressing at the edge of the ganglion (400 μm from the soma) evoked action potentials that were recorded as proximal process potentials at the cell body, but a depolarizing potential was not recorded at this distance. One of the proximal process potentials is shown at a faster sweep speed in the inset. The depolarizing potentials are likely to represent the electrotonic conduction of generator potentials, elicited in the neurites, to the cell body.

In some cases action potentials were recorded at the cell body as proximal process potentials (Fig. 3C). These were deduced to be proximal process potentials because of their brief durations (less than 5 ms at half-amplitude), compared to more than 20 ms for fast EPSPs (Fig. 1), and their constant amplitudes within an individual cell (Wood, 1989; Kunze et al. 1998). Proximal process potentials in enteric neurons in response to mechanical distortion by stretching the wall of the intestine have been reported previously, and shown to be unaffected by soma hyperpolarization, confirming that they are generated in the processes (Kunze et al. 1998).

Depolarizations of nerve cells induced by pressing on the ganglia were not affected (n= 5 cells) by changing the bathing solution to one containing high Mg2+ (10 mm) and low Ca2+ (0.25 mm), which blocks fast (Kunze et al. 1995) and slow (Kunze et al. 1993) synaptic transmission in myenteric ganglia. The calcium-dependent hump was abolished, but neither the amplitude of the depolarization nor the number of evoked action potentials was diminished (Fig. 2). High Mg2+ and low Ca2+ depolarized the neurons, as has previously been reported (Hirst et al. 1985), by 6 mV (median, n= 5 cells).

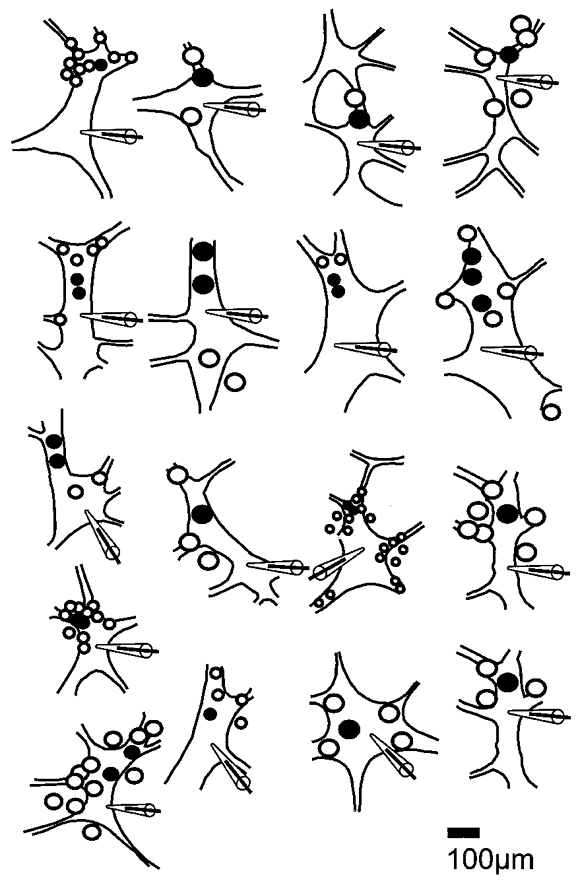

Maps of receptive sites within the ganglion

Sites at which pressing within the ganglion with the probe evoked action potentials in the patched cell were mapped (Fig. 4). Pressing at one or two, and rarely at three, places evoked spikes. Receptive sites were located in the same ganglion as the soma but did not extend into the nerve fibre bundles connecting to adjacent ganglia. Ineffective sites were sometimes intercalated between the soma and the receptive site. Pressing on internodal strands, or on the muscle outside the ganglion, did not elicit depolarizations or action potentials in AH neurons.

Figure 4. Distribution of responsive and unresponsive sites for generating electrical events in mechanosensitive IPANs.

Drawings of ganglion from which recordings were made, as viewed through the inverted microscope. Sites at which pressing evoked (•) or failed to evoke action potentials (○) were plotted during the experiment. The positions of somas from which records were taken are indicated by the tip of the patch pipette silhouette. Sizes of circles correspond to the sizes of probes used (20 or 80 μm).

Mechanical stimulation of the soma

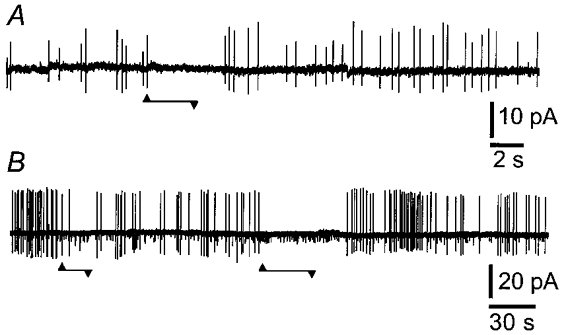

When ganglia were probed for receptive sites, the soma of the patched neuron was distorted. Although this deformation was obvious when cells were viewed through the inverted microscope on which the recording bath was mounted, it failed to increase the excitability of the soma. We therefore directly tested soma excitability by pushing down with the patch pipette in the cell-attached configuration. Moderate deformation (5-10 μm vertical displacement) failed to excite 10/10 neurons. However, when the somas of spontaneously spiking neurons were similarly deformed, action potentials in 5/6 were reversibly inhibited (Fig. 4). More severe deformation (>15 μm) resulted in loss of the seal, sometimes after a brief injury discharge. Single channel recordings were made to reveal channels that might mediate the inhibitory response to deformation of IPAN somas and mechanosensitive large-conductance channels were recorded in 10 patches, four cell attached and six outside-out.

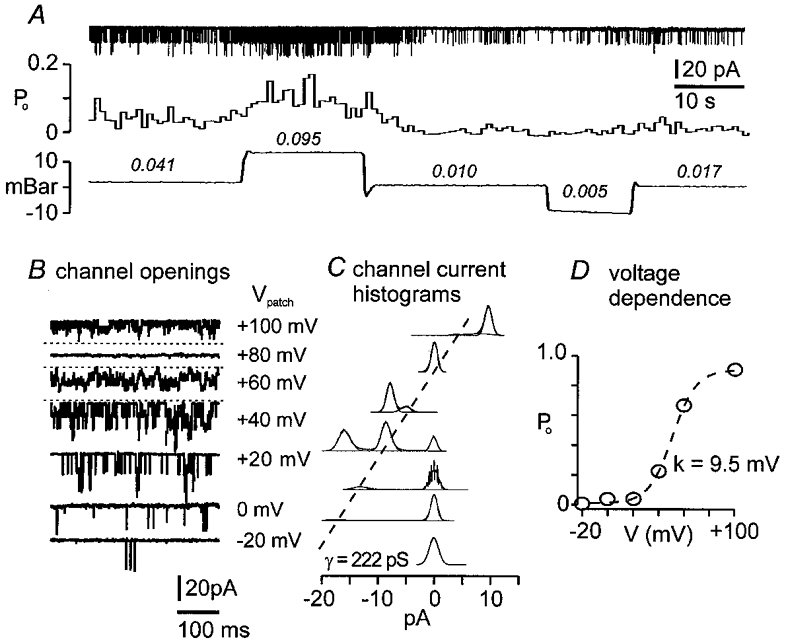

Cell-attached patches

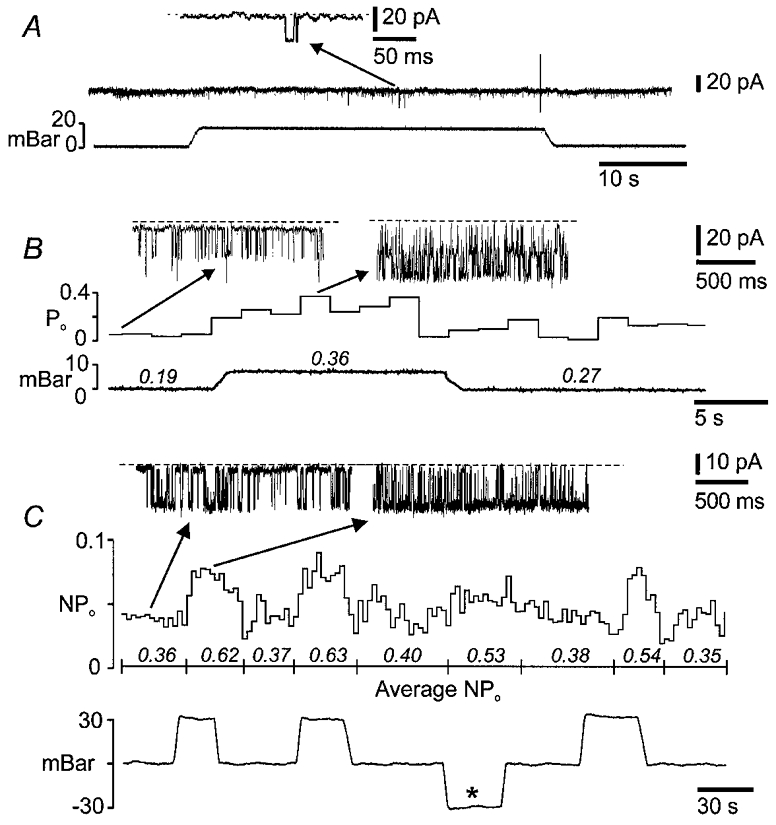

Channel openings consistent with K+ channel activity (inward current at a pipette potential (Vpipette) of 0 mV) were recorded in the cell-attached configuration. For a single patch on each of 16 AH neurons, 5–30 mbar (0.5-3 kPa) of pressure or suction was applied via the pipette. Four of 16 patches tested contained large-conductance K+ channels, whose characteristics are described below, which increased their open probability (Po or NPo) by 50–150 % in response to an increase (≤10 mbar) in intrapipette pressure. Decreases in pressure (suction) of up to 30 mbar were ineffective in altering the Po (Fig. 6). The magnitude and times of onset and offset of responses varied considerably between repeated applications of pressure in the same patch (Fig. 7). A delay usually occurred between the increase in intrapipette pressure and the activation of the mechanosensitive channel. For one response, the increase in NPo occurred after a delay of some hundreds of milliseconds and in 3/4 patches increased activity persisted beyond the period of applied pressure. As has been demonstrated by Wan et al. (1999) for MSCs in Lymnea neurons, prior application of pressure could enhance the response (Fig. 6). However, the NPo was usually smaller for the second trial if the interval between stimuli was less than 30 s; recovery of NPo occurred if intervals were greater than about 1 min. Potassium channels in the remaining 12/16 patches tested had smaller conductances (52 ± 29, 14–75 pS) and were not sensitive to pressures up to ± 30 mbar.

Figure 6. Activity of mechanosensitive BK channels.

The records and analysis are from the same cell-attached patch, with a pipette solution containing 140 mm KCl. A, upper trace is continuous recording of inward unitary current transients; middle trace is Po calculated from time-averaged segments of current trace; lower trace is intrapipette pressure. Positive but not negative pressure doubles the open probability of the K+ channel. Numbers above the pressure trace are mean Po for the corresponding periods. B, voltage dependence of the K+ channel: unitary current amplitude increased with patch hyperpolarization and decreased with depolarization. Depolarization increased channel activity. Horizontal dotted line, in this and subsequent figures, indicates the position of the closed state. C, amplitude histograms of the channel conductance from 5 s sampling periods were each fitted with Gaussian functions. Histograms corresponding to patch potentials (Vpatch) and records are aligned on the closed state. Single channel conductance (γ= 222 pS) is given by the slope of the dashed line connecting the single channel open states. D, plot of steady-state Povs. Vpatch was fitted with a Boltzmann function: Po=Pmax(1 + exp(-(V – V½)/k))−1, with slope factor (k) = 9.5 mV, and membrane potential at half-maximal inactivation (V½) = 52 mV.

Figure 7. Effects of repeated pressure application to cell-attached patches.

A, brief openings seen in previously silent BK channels during the first application of pressure. B, a notably larger increase in open probability is elicited by a second application of pressure, 5 min later. C, for another neuron, repeated applications of positive pressure evoke similar increases in channel activity but with marked variation in onset latencies and durations. Negative pressure (*) did not change NPo. The mean number of open channels (NPo) is given in italics for the intervals marked below the means.

The mechanosensitive K+ channels had large conductances and were voltage sensitive (4 patches tested). With equal K+ (140 mm) on both sides of the membrane, the i-V relation was linear (Fig. 5), the unitary current was 14 ± 5 pA (9-19 pA) and the slope conductance was 195 ± 2 pS (165-222 pS). Steady-state open probability (NPo) was plotted against -Vpipette (i.e. membrane polarization away from rest) and the resulting relation was S shaped (Fig. 6). The plots were well described by the Boltzman function, with a membrane polarization for half-maximal activation (V½) of 21 ± 20 mV, and a slope factor corresponding to an e-fold change in Po (k) of 10.5 ± 1.5 mV.

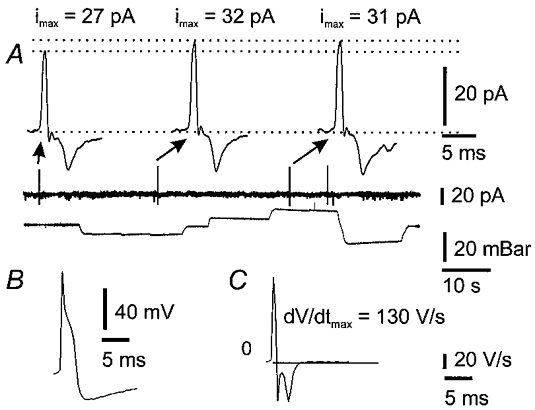

Figure 5. Suppression of action potential firing caused by pressing on somas of IPANs.

These records were taken in the cell-attached configuration. A and B, action potential currents recorded from spontaneously spiking neurons were inhibited when the IPAN cell body was deformed by pressing down (up to 10 μm) with the patch pipette (Vpipette= 0 mV). Onsets and offsets of pressure are marked by upward and downward arrowheads. B, K+ channel openings (small downward deflections) were recorded along with action currents.

Capacitive currents (ipatch) associated with action potential discharge were recorded when the patch potential (Vpatch) was equal to the resting membrane potential (Vpipette= 0 mV). The capacitance of the patch was calculated using the relation Cpatch=ipatch(dV/dt)−1 (Gola et al. 1992). Values of ipatch were recorded in cell-attached configuration and the rate of change of membrane voltage was measured from intracellular action potentials recorded after breaking into the cell. The mean capacitance for 15 patches was 0.10 ± 0.07 pF. Assuming a specific capacitance for neuronal membranes of 0.7 pF (100 μm)−2 (Sokabe & Sachs, 1990), this corresponds to an average patch area of 15 ± 10 μm2. In four patches, application of 10 mbar pressure increased Cpatch (Fig. 7) by 0.02 ± 0.01 pF from an initial value of 0.12 ± 0.07 pF. This indicates that the area of the patch increased by 14.8 ± 2.6 %, assuming that the specific capacitance remained constant (Sokabe & Sachs, 1990).

Overall, 28 patches (not all of which were tested for stretch sensitivity) contained large-conductance (>150 pS) K+ channels. For eight of these, channels were active at the resting membrane potential (Vpipette= 0 mV) and there were two to four channels per patch (determined as explained in Methods). Whole cell capacitance (n= 36 neurons), calculated from the membrane time constant (17 ± 9 ms) and input resistance 319 ± 165 MΩ measured at rest, was 55 ± 22 pF. Thus, the average number of BK channels per neuron was about 1650, calculated as the number of channels per patch multipied by the ratio of whole cell to patch capacitance.

Active BK-like channels were not recorded from S neurons at resting membrane potential, and applying pressure (± 30 mbar) through the patch pipette failed to reveal BK-like channels in five S neurons that were tested.

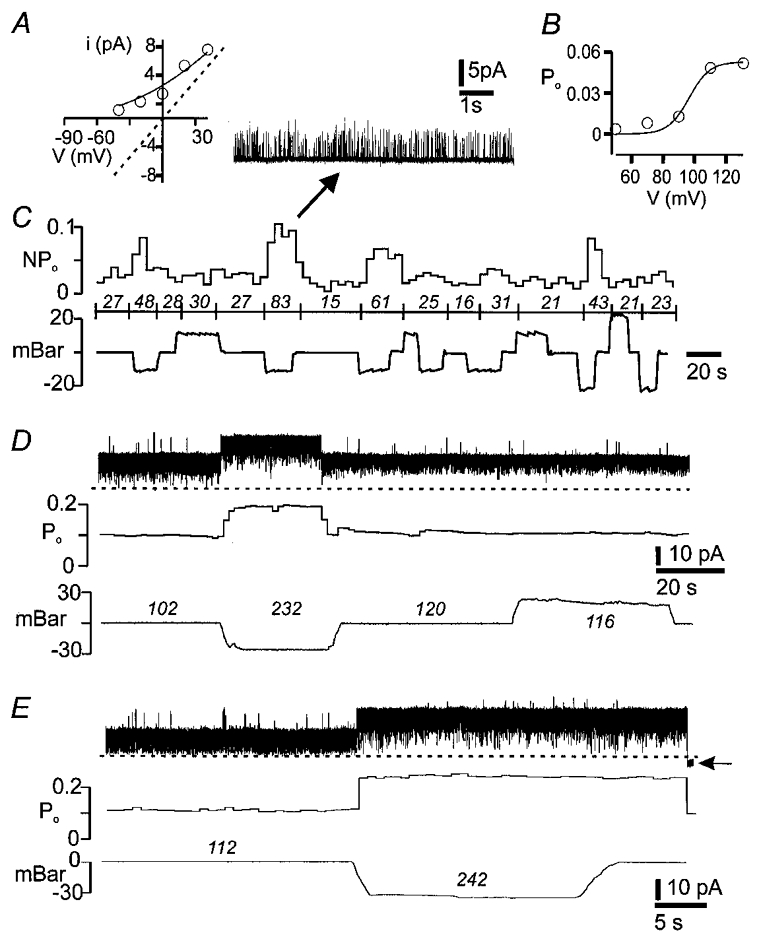

Outside-out patches

Single channel currents in outside-out patches were recorded from 17 neurons with asymmetric K+ ([K+]o= 4.8 mm, [K+]i= 140 mm). Unitary potassium channel currents were obtained in 14 patches; they were positive (outward) at Vpipette= 0 mV and their amplitude approached 0 mV near the equilibrium potential for potassium (EK= -90 mV). Negative (inward) currents from unidentified channels were recorded in three patches which were held at a transpatch potential of -50 mV; these channels were not mechanosensitive. Potassium channels in six patches were activated by decreasing intrapipette pressure (from -10 to -30 mbar), but positive pressure up to 30 mbar did not alter the opening probability. Compared to cell-attached patches, the onset of responses in outside-out patches was more abrupt and there was little accommodation while suction was applied (Fig. 9). The mechanosensitive channels had chord conductances (Vpipette= 0 mV) of 59 ± 22 pS. The unitary current was plotted against voltage and fitted to the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) current equation for asymmetric K+. The value of the K+permeability was then used with the GHK current equation to predict channel conductance for symmetrical K+of 140 mm (Fig. 8). The calculated unitary conductance of the mechanosensitive channels in symmetrical K+ was in the range for BK channels (202 ± 65 pS). The steady-state open probability was measured for different transpatch voltages for three of these channels and Po-V plots were fitted with the Boltzmann function. The channels, like the mechanosensitive K+ channels recorded in cell-attached patches, were voltage dependent (Fig. 8), with a V½ of 11.8 ± 10 mV and a slope factor of 6.0 ± 0.9 mV. Addition of 20 nM charybdotoxin to the superfusate abolished channel opening for 3/3 of the mechanosensitive channels. K+ channels in the remaining eight patches had lower chord conductances (25 ± 15 pS at Vpipette= 0 mV) and were not mechanosensitive.

Figure 9. Responses of BK channels recorded in outside-out patches.

A, plot of unitary current (i) vs. patch voltage was fitted with the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz current equation for asymmetric [K+] (140/4.8 mm). The predicted i-V relationship in symmetrical [K+] is indicated by the dashed line which has a slope of 180 pS. B, open probability-patch voltage plot was fitted with the Boltzmann function, which gave a slope factor of 6.5 mV and V½ of 6.4 mV. C, unequal responses (upper trace) to repeated applications of negative but not positive pressure (lower trace) to patch. Data in A-C are from the same patch. D and E, BK channel with brisk responses to application of suction to the patch. Note that the increase in Po persisted beyond the second pressure wave. Loss of seal is marked by the horizontal arrow. Po and NPo× 1000 are given in italics for the intervals indicated by the pressure traces.

Figure 8. Estimation of changes in patch area with changes in patch pressure.

Examples of recordings that were used to estimate changes in cell-attached patch area are illustrated. A, spontaneous action currents recorded before (first action current) and while applying ± 10 mbar (2nd and 3rd action currents) to the patch pipette. Amplitudes of action current spikes increased during application of pressure or suction, indicating that total capacitance, and hence membrane area, increased. B, intracellular action potential recorded from the same cell after breaking through the patch. C, time differential of the action potential. The time of maximal voltage rate of change coincides with the peak of the capacitative current transients in A.

Taken together, recordings from cell-attached and outside-out patches revealed a difference in mechanical sensitivity between BK channels (sensitive in 10/10 patches) and smaller K+ channels (sensitive in 0/20 patches) (P < 0.002; Fischer's exact probability test, two tailed).

DISCUSSION

Differential responses to mechanical stimulation

The present work reveals that myenteric AH neurons are excited by mechanical distortion of their processes and are inhibited by mechanical force on the cell body. However, in other mammalian sensory neurons mechanical distortion increases excitability of both the neurites and the cell bodies (Cunningham et al. 1995, 1997; Kraske et al. 1998; Raybould et al. 1999). Because IPANs in the gut have neurites with mechanosensitive regions close to their cell bodies, we have been able to record the responses from both sources by recording from the cell bodies in situ.

Neurite mechanosensitive channels

The present work supports our previous conclusion, made with less direct evidence, that the processes of AH neurons are mechanosensitive (Kunze et al. 1998, 1999). In the present study, distortion of the ganglia with a hair or glass probe, away from the cell body, evoked depolarizations and action potentials that were recorded at the cell body and these were not affected by block of synaptic transmission. We propose that the depolarizations represent the electrotonic conduction of generator potentials to the cell body from their sites of initiation in the processes. Their remote origin and electrotonic conduction is indicated by the invariance in input resistance, measured at the soma (Sah & Bekkers, 1996). Responses elicited from greater distances in this study and previously (Kunze et al. 1998, 1999) consisted only of action potentials, implying that the mechanotransduction occurred at distances of at least several length constants from the soma, too far for generator potentials to be recorded.

The generator potentials lasted for only as long as pressure was applied, although the accompanying spike discharge ceased before removal of the stimulus. Whether this adaptation in firing is a consequence of the intrinsic properties of mechanosensitive channels or indicates the presence of other, outwardly rectifying, ion channels in the region of action potential initiation requires direct recording from the processes. Several properties of the neurite mechanosensitive channels (MSCs) can be inferred. The activation of neurite MSCs is not inhibited by low concentrations of gadolinium (1 μm) because muscle contraction is able to elicit neurite action potentials in the presence of gadolinium (Kunze et al. 1999). Also, it is unlikely that the MSCs are calcium channels because the generator potentials were not diminished when 10 mm Mg2+ was included in the superfusate and Ca2+ was reduced to 0.25 mm.

Receptive sites were located in the ganglion but did not extend over the interganglionic connectives or adjacent longitudinal muscle. This parallels observations by Ohkawa & Prosser (1972) who reported that extracellularly recorded spike discharge could be evoked by pressing on myenteric ganglia with a fine glass probe but that pressing on the connective tissues or the muscle was ineffective.

Structural and physiological analysis of the enteric circuitry indicate that IPANs form self-reinforcing networks, in which IPANs communicate with each other through slow EPSPs (Kunze & Furness, 1999). However, we did not record slow EPSPs in IPANs when the ganglia were probed mechanically. This may be attributed to the small number and localized nature of sites responsive to probing and to the brief responses of neurons. Thus there may be low probability of recording from an IPAN, receiving synapses from a neuron activated by the probe, in which a slow EPSP is of sufficient amplitude to record. As Morita & North (1985) point out, slow EPSPs sometimes cause little change in membrane potential.

Mechanosensitivity of the soma

Action currents were inhibited in cells that were distorted by being pressed on by the recording electrode (whole cell recording). Consistent with these observations, increased intrapipette pressure when recording from cell-attached patches, or suction on outside-out patches, opened K+ channels. This surprising finding appears to be the first demonstration of mechanical inhibition at the soma of a sensory neuron. By contrast, acutely dissociated nodose baroreceptor neurons respond to soma stretch with net inward currents, through excitatory (cationic) MSCs (Cunningham et al. 1995; Kraske et al. 1998). Similarly, the cell bodies of dorsal root ganglion neurons which innervate the intestine are excited through an inward current when they are prodded with a glass probe (Raybould et al. 1999). Wall & Devor (1983) showed that action potential discharge in primary afferent neurons is increased by pressure applied to the dorsal root ganglion.

Stretch sensitivity to intrapipette pressures of 5–20 mbar was demonstrated only for large-conductance, voltage-dependent K+ channels. K+ channels with smaller conductances and other channels carrying an inward current in outside-out patches were unaffected by pressure changes. The large-conductance mechanosensitive channels were blocked by 20 nM external charybdotoxin, had a conductance in symmetrical high [K+] (140 mm) of about 220 pS, and were sensitive to voltage, properties that are characteristic of BK channels (Blatz & Magleby, 1987; Vergara et al. 1998).

In cell-attached patches, the BK-like channel in AH neurons was frequently active at the resting membrane potential in the absence of applied pipette pressure. During the formation of such patches, a vesicle incorporating both membrane and cytoplasm forms inside the pipette, and the membrane in the pipette can undergo spontaneous concave deformations (Sokabe & Sachs, 1990). Thus, mechanosensitive channels may be continuously activated, which would shift the NPo-V curve to hyperpolarizing potentials. Consistent with this, we observed that the BK channels were active even when the cell-attached patches were not depolarized from the resting membrane potential (about -60 mV), a condition when other, presumably stretch-insensitive, BK channels would be inactive (Blatz & Magleby, 1987).

If they are present, stretch-sensitive Ca2+ channels might confer pressure-sensitive responses to calcium-dependent potassium channels. However, responses of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels would be abolished if [Ca2+]i is clamped at 1 nM (Christensen, 1987), as it was in our outside-out patches, for which the Ca2+ that was available at the inside surface of the membrane was 1 nM (calculated according to Bers et al. 1994; see Methods). The pressure sensitivity persisted in the outside-out configuration, indicating that the BK channels were directly mechanosensitive. The present paper appears to be the first one to describe a BK-like mechanosensitive channel in a neuron, although they have been previously described in, for example, smooth muscle (Dopico et al. 1994), heart muscle (Kawakubo et al. 1999), renal tubules (Taniguchi & Imai, 1998) and osteosarcoma cells (Davidson, 1993).

Cytoskeletal involvement in the mechanosensitive responses is suggested by a number of observations. The most compelling was that for both cell-attached and outside-out configurations the direction of membrane curvature was critical for activation of the channel, increased intrapipette pressure being effective in cell-attached patches and decreased pressure being effective in outside-out patches. Also, the enhanced responses after repeating the pressure application or after excising the patch is consistent with intact cytoskeletal elements shielding channels from excessive tension (see Sachs & Morris, 1998; Wan et al. 1999).

Is the degree of distortion of the neuronal soma physiological?

The open probability of BK channels was altered with intrapipette pressures of 5–20 mbar. This is low compared to the intrapipette pressure of over 100 mbar used by Wan et al. (1999) to establish the mechanosensitivity of Lymnea neurons. Even at the low pressures used, changes in patch capacitance when pressure was applied show that the membrane area was increased by about 15 % (see Results). How does this compare to the stretch experienced by the soma as a whole in contracting gut? Shape changes in myenteric neuron profiles when the gut wall contracts and relaxes have been measured (Gabella & Trigg, 1984). The somas are like thick elliptical discs in the plane of the gut surface. Assuming the somas are of constant volume, the change in total surface area can be calculated from the data of Gabella & Trigg (1984), who reported that the profile area of myenteric neurons in the plane of the plexus changes from 219 μm2 in the contracted intestine to 411 μm2 with distension (95 % increase). These authors also published micrographs, which we have measured, that indicate a reduction in the thicknesses of the nerve cells by a factor of 1.9 in the distended intestine. The flattening of the discs will increase the total surface areas of the somas, the extent of the increase depending on whether the profiles retain their initial shape or are elongated by gut distension. The increase in surface area (2 × disc area plus circumference × thickness) can be calculated using an approximation for the perimeterof an ellipse (p):

where a and b are the ellipse's hemiaxes (Ramanujan, 1913). The minimum change in surface area given by the data of Gabella & Trigg (1984) is an increase of 12.6 %, for a nerve cell for which the eccentricity of the profile is unchanged. If the cell were to change asymmetrically, lengthening and narrowing, the increase in surface area would be greater, by a factor of 16 % if the ratio of length to breadth doubled. Data on asymmetry of change is not in the published paper, although a greater stretch in the circumferential direction is suggested by Fig. 3 of Gabella & Trigg (1984). Thus, the degree of stretch (∼15 %) that we have shown to cause large KCa channels to open is of the same order as that which the soma would be expected to experience during normal gut function.

Physiological implications

The physiological significance of our results requires further, direct investigation. However, some implications can be drawn. The IPANs form connections with each other, via slow excitatory synaptic connections, and they are extremely frequent, about 600 per millimetre length of gut (Kunze & Furness, 1999). Their neurites are excited by contraction of the gut, which pulls on connections with the neurons (Kunze et al. 1999). Thus, when the gut contracts, the neurons will be excited via their neurites and via synaptic inputs, but stretch of the soma membrane will be diminished, and inhibition via soma BK channels will be minimized. On the other hand, if the gut is distended and the muscle contracts against the distending force, inhibition via soma BK channels will be greater. It is possible that the stretch sensitivity of the soma channels plays a protective role, reducing the firing of the neurons and the intensity of reflexes, when the intestine contracts against a blockage that it fails (at least initially) to dislodge. The only relevant experimental data that we have been able to find in the literature is consistent with these speculations (Streeton & Vaughan Williams, 1951). These authors studied the efficiency of peristalsis in Thiry-Vella loops in which the inflow and outflow pressures could be varied. Wall pressure was increased by increasing both pressures at the same time; as this was done, the efficiency of peristalsis at first increased at pressures in the range 1–4 cmH2O which trigger peristalsis, but decreased as wall pressure was increased from about 7 to 12 cmH2O. Normal pressures in the dog duodenum are 2–4 cmH2O (Sherrington, 1915).

Conclusion

The sensory neurons within the gut wall are subjected to mechanical deformation of their processes and of their cell bodies. Deformation of the processes by stretch that occurs when the intestine is distended or the muscle contracts excites the neurons and triggers reflexes. Compression of the soma by pressure causes increased opening of potassium channels and thus has an inhibitory effect, which may be protective.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and a grant from the University of Melbourne Collaborative Research Program.

References

- Bers D, Patton C, Nuccitelli R. Methods in Cell Biology: A Practical Guide to the Study of Ca2+ in Living Cells. Vol. 40. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca buffers; pp. 3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatz AL, Magleby KL. Calcium-activated potassium channels. Trends in Neurosciences. 1987;10:463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen O. Mediation of cell volume regulation by Ca2+ influx through stretch-activated channels. Nature. 1987;330:66–68. doi: 10.1038/330066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc N, Furness JB, Bornstein JC, Kunze WAA. Correlation of electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of myenteric neurons of the duodenum in the guinea-pig. Neuroscience. 1998;82:899–914. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Wachtel RE, Abboud FM. Mechanosensitive currents in putative aortic baroreceptor neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:2094–2098. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Wachtel RE, Abboud FM. Mechanical stimulation of neurites generates an inward current in putative aortic baroreceptor neurons in vitro. Brain Research. 1997;757:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RM. Membrane stretch activates a high-conductance K+ channel in G292 osteoblastic-like cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1993;131:81–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02258536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopico AM, Kirber MT, Singer JJ, Walsh JV., Jr Membrane stretch directly activates large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Hypertension. 1994;7:82–89. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyzaguirre C, Kuffler SW. Process of excitation in the dendrites and in the soma of single isolated sensory nerve cells of the lobster and crayfish. Journal of General Physiology. 1955;39:87–119. doi: 10.1085/jgp.39.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabella G, Trigg P. Size of neurons and glial cells in the enteric ganglia of mice, guinea-pigs, rabbits and sheep. Journal of Neurocytology. 1984;13:49–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01148318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Ducreux C, Chagneux H. Ca2+-activated K+ current involvement in neuronal function revealed by in situ single-channel analysis in Helix neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;420:73–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Niel JP, Bessone R, Fayolle R. Single-channel and whole-cell recordings from non-dissociated sympathetic neurones in rabbit coeliac ganglia. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;43:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90062-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GDS, Johnson SM, van Helden DF. The slow calcium-dependent potassium current in a myenteric neurone of the guinea-pig ileum. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;361:315–337. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. Depolarization of sensory terminals and the initiation of impulses in the muscle spindle. The Journal of Physiology. 1950;111:261–282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1950.sp004479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakubo T, Naruse K, Matsubara T, Hotta N, Sokabe M. Characterization of a newly found stretch-activated KCa,ATP channel in cultured chick ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:H1827–1838. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraske S, Cunningham JT, Hajduczok G, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM, Wachtel RE. Mechanosensitive ion channels in putative aortic baroreceptor neurons. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:H1497–1501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WAA, Bornstein JC, Furness JB. Identification of sensory nerve cells in a peripheral organ, the intestine of a mammal. Neuroscience. 1995;66:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00067-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WAA, Clerc N, Bertrand PP, Furness JB. Contractile activity in intestinal muscle evokes action potential discharge in guinea-pig myenteric neurons. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:547–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0547t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WAA, Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and regulation of intestinal motility. Annual Review of Physiology. 1999;61:117–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WAA, Furness JB, Bertrand PP, Bornstein JC. Intracellular recording from myenteric neurons of the guinea-pig ileum that respond to stretch. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.827bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WAA, Furness JB, Bornstein JC. Simultaneous intracellular recordings from enteric neurons reveal that myenteric AH neurons transmit via slow excitatory postsynaptic potentials. Neuroscience. 1993;55:685–694. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90434-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, North RA. Significance of slow synaptic potentials for transmission of excitation in guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Neuroscience. 1985;14:661–672. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Prosser CL. Functions of neurons in enteric plexuses of cat intestine. American Journal of Physiology. 1972;222:1420–1426. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.6.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujan S. Modular equations and approximations to π. Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. 1913;45:350–372. [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE, Gschossman JM, Ennes H, Lembo T, Mayer EA. Involvement of stretch-sensitive calcium flux in mechanical transduction in visceral afferents. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1999;75:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F, Morris CE. Mechanosensitive ion channels in nonspecialized cells. Review of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1998;132:1–77. doi: 10.1007/BFb0004985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Bekkers JM. Apical dendritic location of slow afterhyperpolarization current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons: implications for the integration of long-term potentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:4537–4542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04537.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte IWM, Kroese ABA, Akkermans LMA. Somal size and location within the ganglia for electrophysiologically identified myenteric neurons of the guinea pig ileum. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;355:563–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington CS. Postural activity of muscle and nerve. Brain. 1915;38:191–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsun WJ, Morris CE, Brezden BL, Gardner DR. Stretch activation of a K+ channel in molluscan heart cells. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1987;127:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe M, Sachs F. The structure and dynamics of patch-clamped membranes: a study using differential interference contrast light microscopy. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1990;111:599–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeten DHP, Vaughan Williams EM. The influence of intraluminal pressure upon the transport of fluid through cannulated Thiry-Vella loops in dogs. The Journal of Physiology. 1951;112:1–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi J, Imai M. Flow-dependent activation of maxi K+ channels in apical membrane of rabbit connecting tubule. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1998;164:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s002329900391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Latorre R, Marrion NV, Adelman JP. Calcium-activated potassium channels. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1998;8:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD, Devor M. Sensory afferent impulses originate from dorsal root ganglia as well as from the periphery in normal and nerve injured rats. Pain. 1983;17:321–339. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Juranka P, Morris CE. Activation of mechanosensitive currents in traumatized membrane. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:C318–327. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.2.C318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD. Electrical and synaptic behavior of enteric neurons. In: Schultz SG, Wood JD, Ranner BB, editors. Handbook of Physiology. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1989. pp. 465–516. [Google Scholar]