Abstract

Receptor-mediated modulation of ion channels generally involves G-proteins, phosphorylation, or both in combination. The sigma receptor, which modulates voltage-gated K+ channels, is a novel protein with no homology to other receptors known to modulate ion channels. In the present study patch clamp and photolabelling techniques were used to investigate the mechanism by which sigma receptors modulate K+ channels in peptidergic nerve terminals.

The sigma receptor photoprobe iodoazidococaine labelled a protein with the same molecular mass (26 kDa) as the sigma receptor protein identified by cloning.

The sigma receptor ligands pentazocine and SKF10047 modulated K+ channels, despite intra-terminal perfusion with GTP-free solutions, a G-protein inhibitor (GDPβS), a G-protein activator (GTPγS) or a non-hydrolysable ATP analogue (AMPPcP).

Channels in excised outside-out patches were modulated by ligand, indicating that soluble cytoplasmic factors are not required. In contrast, channels within cell-attached patches were not modulated by ligand outside a patch, indicating that receptors and channels must be in close proximity for functional interactions. Channels expressed in oocytes without receptors were unresponsive to sigma receptor agonists, ruling out inhibition through a direct drug interaction with channels.

These experiments indicate that sigma receptor-mediated signal transduction is membrane delimited, and requires neither G-protein activation nor protein phosphorylation. This novel transduction mechanism is mediated by membrane proteins in close proximity, possibly through direct interactions between the receptor and channel. This would allow for more rapid signal transduction than other ion channel modulation mechanisms, which in the present case of neurohypophysial nerve terminals would lead to the enhancement of neuropeptide release.

Sigma receptors modulate the excitability of peptidergic nerve terminals in the neurohypophysis by inhibiting voltage-dependent K+ channels (IK) (Wilke et al. 1999a). The activation of sigma receptors by a variety of ligands reduces current flow through two distinct K+ channel types, the A-current channel (IA) and the Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IBK). Current is reduced by the same proportion over the entire accessible voltage range, with no shift in the voltage dependence of activation or inactivation. Furthermore, the residual unblocked currents inactivate with very similar rates, indicating that sigma receptor modulation entails a shutting down of function rather than a modification of gating behaviour (Wilke et al. 1998, 1999a,b). A comparison of the concentration dependence of IA reduction with that of IBK reduction indicated that the sigma receptor ligand PPHT inhibits both of these channels with a very similar EC50 (Wilke et al. 1998); similar results were obtained with haloperidol (Wilke et al. 1999a). Both IA and IK were reduced proportionally by a large number of sigma receptor ligands (including ditolylguanidine, SKF10047, pentazocine, haloperidol, PPHT, U101958, and apomorphine), suggesting that in the rat the same receptor is coupled to two types of K+ channels. In D2, D3 and D4 dopamine receptor-deficient mice, sigma receptor ligands reduced IK as effectively as in wild-type mice, indicating that the responses are not mediated by dopamine receptor subtypes known to interact with some sigma receptor ligands (Wilke et al. 1999a). Many candidate endogenous ligands were tested, including neuropeptides, catecholamines, and steroids, and none altered IK in this preparation. Furthermore, although the posterior pituitary contains κ-opioid receptors, which modulate Ca2+ channels (Rusin et al. 1997), K+ channels are not modulated by dynorphin in this preparation (authors’ unpublished observations), indicating that the reduction of IK by these ligands is not mediated by opioid receptors.

The sigma receptor binding site was first described over two decades ago. Originally thought to be a novel opioid receptor (Martin et al. 1976), subsequent studies demonstrated that the sigma receptor binding site is a distinct pharmacological entity distinguished by unusually promiscuous binding properties (Su, 1993; de Costa & He, 1994). Recent molecular characterization has shown that the sigma receptor is a novel protein with a molecular mass of 26 kDa. Hydropathy analysis has indicated that this protein has a single putative membrane-spanning segment (Hanner et al. 1996; Kekuda et al. 1996; Seth et al. 1997). The deduced amino acid sequence of the sigma receptor has no homology with known mammalian proteins, but a weak homology with fungal sterol isomerase has led some investigators to speculate that sigma receptors may be involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis (Jbilo et al. 1997; Moebius et al. 1997). Sigma receptors are ubiquitously distributed in both brain and peripheral tissue. Their binding to many different kinds of drugs has made it difficult to determine their function, but sigma receptors have been implicated in a variety of functions, including motor control, psychosis, and a wide range of endocrine and immune processes (Su, 1993; Bowen, 1993).

The unique molecular structure of the sigma receptor has raised intriguing questions about its mechanism of signal transduction. As novel proteins, sigma receptors fall outside the large families of membrane signalling molecules that have been identified in the past two decades. The sigma receptor does not have seven putative transmembrane domains, and so it would appear that this protein lacks the essential structural elements necessary for an interaction with G-proteins. At a topological level, the single putative transmembrane segment of the sigma receptor is reminiscent of many growth factor receptors with protein kinase activity, but at the sequence level no homology was found. There is some evidence that sigma receptor activation stimulates GTPase activity in mouse and rat brain (Itzhak, 1989; Tokuyama et al. 1997). GTP analogues have been reported to influence the binding of sigma receptor ligands (Beart et al. 1989), but a number of other binding studies led to different conclusions (Bowen, 1994). The modulation of IK by sigma receptor ligands was abolished by reagents that inactivate G-proteins in some studies (Nakazawa et al. 1995; Soriani et al. 1998, 1999), but in other studies G-protein perturbation had no effect (Morio et al. 1994; Wilke et al. 1999b). These questions and conflicting results prompted us to use patch clamp techniques to investigate the mechanism by which sigma receptors inhibit IK in nerve terminals of slices prepared from the posterior pituitary gland. Reagents known to block G-protein and phosphorylation-mediated signal transduction pathways failed to prevent IK modulation. Sigma receptor ligands modulated channel function in excised outside-out patches in the absence of soluble cytoplasmic factors. In contrast, channels within cell-attached patches could not be modulated by drug application to adjacent membrane outside the pipette tip. These results indicate that sigma receptors modulate membrane function by a novel membrane-delimited mechanism requiring close proximity between receptors and channels.

METHODS

Tissue preparation

Experiments were carried out in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals. Sprague-Dawley rats were rendered unconscious by rising concentrations of CO2 and then decapitated. The pituitary gland was removed, and the neurointermediate lobe was separated and glued to a Plexiglas chamber. Slices 75 μm thick were cut with a Vibratome (Technical Products, International, St Louis, MO, USA) while chilling with ice-cold saline (Jackson et al. 1991). Tissue was prepared and maintained in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) consisting of (mM): 115 NaCl, 4.0 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 glucose, bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. During recordings the preparation was perfused with aCSF by gravity feed at a rate of 2-4 ml min−1. Slices were stored at room temperature (21-24°C) in aCSF and used within 3 h of preparation.

Electrophysiology

An upright DIC microscope (Reichert-Jung Diastar) equipped with either a Zeiss × 40 or Olympus × 60 water-immersion objective was used to locate nerve terminals at the slice surface for recording. Recordings were made using an EPC-7 patch clamp amplifier (Instrutech, Elmont, NY, USA) interfaced to a PC, or an EPC-9 patch clamp amplifier (Instrutech) interfaced to a MacIntosh computer. Stimulus and data acquisition were controlled with the computer program pCLAMP7 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) on the PC, or PULSE (Instrutech) on the MacIntosh. Patch pipettes were fabricated from thin-walled borosilicate glass (Garner Glass, Claremont, CA, USA) and coated with Sylgard to reduce capacitance (Hamill et al. 1981). Terminal capacitance and series resistance were determined by transient cancellation; series resistance was often compensated by ∼50 %. For whole-terminal and outside-out patch recordings, pipettes were filled with (mM): 130 KCl, 10 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 2 MgATP, 0.1 NaGTP, pH 7.3. In many experiments this solution was modified as indicated in Results and figure legends by omitting ATP and/or GTP, and including β,γ-methylene adenosine triphosphate (AMPPcP, Sigma), γ-thiol-guanosine triphosphate (GTPγS, Sigma), β-thiol-guanosine diphosphate (GDPβS, Sigma) or okadaic acid (Calbiochem). The pipette solution for cell-attached patches contained (mM): 150 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH. Prior to contact with the cell membrane, pipette resistances ranged from 3 to 8 MΩ. Voltage clamp protocols for investigating IK are indicated in the figure legends, and were similar to those described in previous reports from this laboratory (Bielefeldt et al. 1992). Since the modulation of IK is proportional over a wide range of voltages (Wilke et al. 1998,1999a, b), the results were insensitive to variations in the pulse protocol employed here.

Photolabelling

Photolabelling follows methods described previously (Wilke et al. 1999b). The sigma receptor photolabel iodo-4-azidococaine ([125I]IAC) was synthesized according to Kahoun & Ruoho (1992). Posterior pituitary glands were removed from ten rats and homogenized with a Teflon pestle in phosphate-buffered saline (mM: 140 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 10 Na2HPO4, 1.8 KH2PO4, at pH 7.3). The homogenate was divided into 100 μl aliquots and incubated in the same saline at 0°C with the indicated concentrations of ligand for 30 min. [125I]IAC (1 nM) was added to each aliquot and the incubation continued for another 7.5 min, at which time the homogenate was illuminated for 5 s with a mercury lamp. Labelled proteins were then resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12 % acrylamide) (Kahoun & Ruoho, 1992) and detected with phosphorimaging.

Drug application

Pentazocine, SKF10047, and ditolylguanidine were obtained from Research Biochemicals, Inc. (Natick, MA, USA), and applied in solutions of aCSF. DMSO was used in some experiments to aid solubilization of drugs, but the final DMSO never exceeded 0.1 %, and this level had no effect on IK. Bath application of drug was made either by direct dilution of stock into the recording chamber or replacement of aCSF perfusing the preparation with aCSF supplemented with the indicated drug concentration. In a few experiments drug was applied from a patch pipette positioned approximately 10 μm from the nerve terminal under recording. Pressure pulses (10 p.s.i. (7 kPa) 5-10 s) were applied by a Picospritzer to eject the drug (General Valve Corp., Fairfield, NJ, USA). Prior to drug addition, the stability of baseline current was verified by recording IK at 15 s intervals for 1-4 min. In experiments where the patch pipette solution was used to introduce reagents into the nerve terminal interior, a longer predrug baseline was obtained (3-5 min) to allow sufficient time for effective internal perfusion (Pusch & Neher, 1988).

Oocyte expression and recording

Oocytes were collected from female frogs (Xenopus laevis, Nasco) anaesthetized by 10-20 min exposure to 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (1 g l−1). Small abdominal incisions were made above the ovary, first through the skin and then the muscle. Several lobes of ovary were removed with a single scissors cut. The abdominal muscle and the skin were resutured separately and the frog was allowed to recover in shallow water. After the final removal of oocytes the animals were humanely killed. After removal of the follicular membranes, oocytes were cultured at 18°C in storage solution consisting of (mM): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 Hepes at pH 7.4, supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin. The Kv1.4 K+ channel clone was obtained from G. N. Tseng (Columbia University) and the Kv1.5 K+ channel clone was obtained from L. Kaczmarek (Yale University). These genes were subcloned into the pGH19 oocyte expression vector and RNA was transcribed from the T7 promoter using a T7 Message Machine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RNA was diluted in sterile water and injected (∼10-50 ng per oocyte). K+ current was recorded using a two-electrode voltage clamp (Warner Gene-Clamp, Hamden, CT, USA) and pCLAMP7.0 software (Axon Instruments). Glass capillary electrodes had resistances of 0.5-1 MΩ when filled with 2 M KCl. Bathing solution consisted of (mM): 93 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.3 CaCl2, 5 Hepes at pH 7.4, and recordings were made at room temperature (22-24°C).

Data analysis

Current recordings were analysed on a PC with pCLAMP 7, or on a MacIntosh computer with PULSEFIT. Simple statistical analyses were performed on exported data using Microsoft Excel. Where arithmetic means were computed, they are presented with the standard error of the mean. When statistical significance was determined it was based on Student's t test.

RESULTS

Sigma receptor-mediated inhibition of K+ current

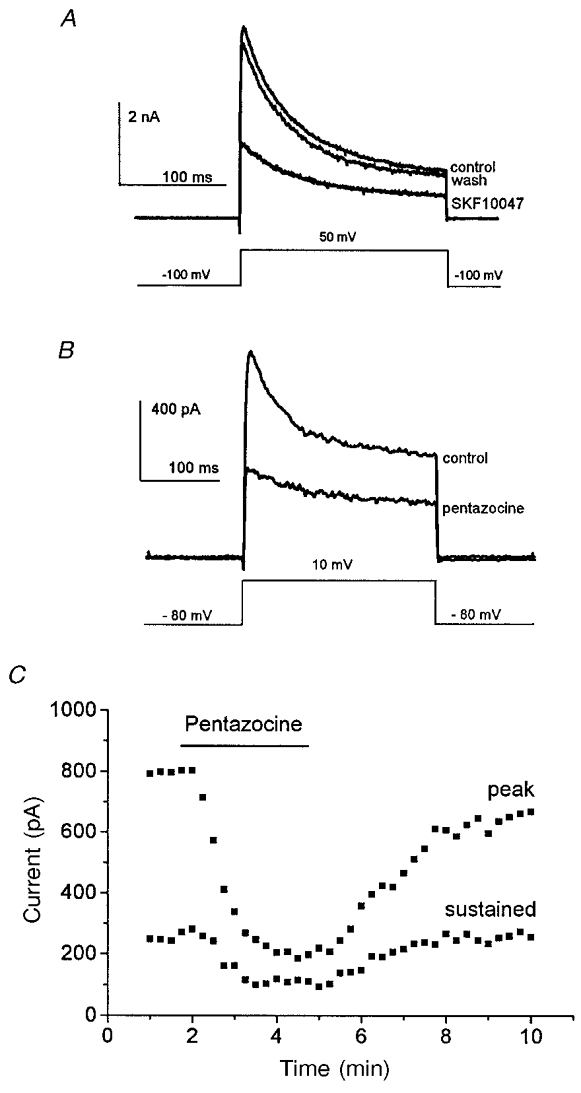

Nerve terminals of the neurohypophysis have voltage-gated K+ channels that are activated by depolarizing pulses (Jackson et al. 1991; Bielefeldt et al. 1992). Figure 1 shows IK recordings in this preparation, and the reduction of IK following application of the sigma receptor ligands SKF10047 and pentazocine. A recovery trace recorded ∼1 min after SKF10047 removal shows that in this time IK recovered almost completely. SKF10047 reduced peak IK to 56 ± 11 % of the control; the sustained component of IK recorded at the end of the 200 ms pulse to 50 mV was reduced to 64 ± 11 % of control (n = 4). (Here and elsewhere, controls refer to the predrug IK baseline value obtained with the same pulse protocol prior to drug application.) Pentazocine reduced peak and sustained IK to 39 ± 8 and 47 ± 9 % of control values, respectively (n = 4). As with SKF10047, the modulation of IK by pentazocine reversed after drug removal; the time course of onset and recovery for pentazocine is shown in Fig. 1C.

Figure 1.

Sigma receptor ligands inhibit IK

A, nerve terminal membranes were held at -100 mV and stepped to 50 mV for 200 ms to activate IK. SKF10047 (100 μm) was applied from a picospritzer for 5 s and current was recorded again. Washing with control saline removed the drug and allowed IK to recover to control levels in 1 min. B, nerve terminals were held at -80 mV and stepped to 10 mV for 250 ms to activate IK. Pentazocine (100 μm) was applied by bath perfusion and current was blocked after 2 min. The drugs reduced both peak and sustained components of IK. C, plot of peak IKversus time as pentazocine was applied and removed (the time of drug application is indicated by the bar).

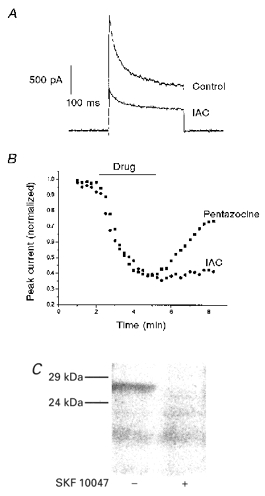

In an effort to relate these physiological responses to a molecularly characterized receptor, experiments were carried out with the sigma receptor photoprobe IAC (Kahoun & Ruoho, 1992). This compound reduced peak IK to 40 ± 12 % of control and sustained IK to 52 ± 11 % of control (Fig. 2A, n = 4). In contrast to the responses to pentazocine and SKF10047, IK did not recover following exposure to IAC (Fig. 2B). The lack of recovery with IAC may reflect the very high affinity of this drug for sigma receptors (Kd < 1 nM; Kahoun & Ruoho, 1992). Alternatively, since IAC is a photoprobe, there could be some photolysis by the microscope illumination while recordings are in progress, leading to chemical modification of residues in or near the sigma receptor binding site.

Figure 2.

Agonist activity and photolabelling by iodoazidococaine (IAC)

A, IAC reduced IK evoked by voltage pulses as in Fig. 1. B, time course of modulation of IK while drug was added and removed (the time of drug application is indicated by the bar). Values plotted were normalized to predrug control IK. Peak IK was reduced by 100 μm pentazocine and 100 μm IAC. Three minutes after return to control solution IK partly recovered in the terminal exposed to pentazocine but not in the terminal exposed to IAC. C, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed on homogenized neurohypophysis after photolabelling with [125I]IAC. Phosphorimaging revealed labelled proteins. A band at 26 kDa was labelled (left), and the labelling of this band was blocked by 100 μm SKF10047 (right).

Homogenized pituitary was photolabelled with [125I]IAC, and subsequent SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed that a 26 kDa protein was labelled. The labelling of this protein was selectively blocked by SKF10047 (Fig. 2C). This experiment was performed three times, but each experiment required 10 rats, and the small amount of tissue limited how many lanes could be run in one experiment. Similar photolabelling experiments in a clonal lung tumour cell line recently showed that the concentration dependence of block of photolabelling by SKF10047 was similar to the concentration dependence of inhibition of IK (Wilke et al. 1999b). These results indicate that the sigma receptor bindings sites of the pituitary (Wolfe et al. 1989) and physiological responses to sigma receptor ligands (Wilke et al. 1999a) are associated with a protein with the same molecular mass as that encoded for by sigma receptor cDNA (Hanner et al. 1996; Kekuda et al. 1996; Seth et al. 1997). The molecular mass of the sigma receptor, 26 kDa, is well below that of the molecularly characterized voltage-gated K+ channels with properties similar to those modulated in this preparation (see Discussion).

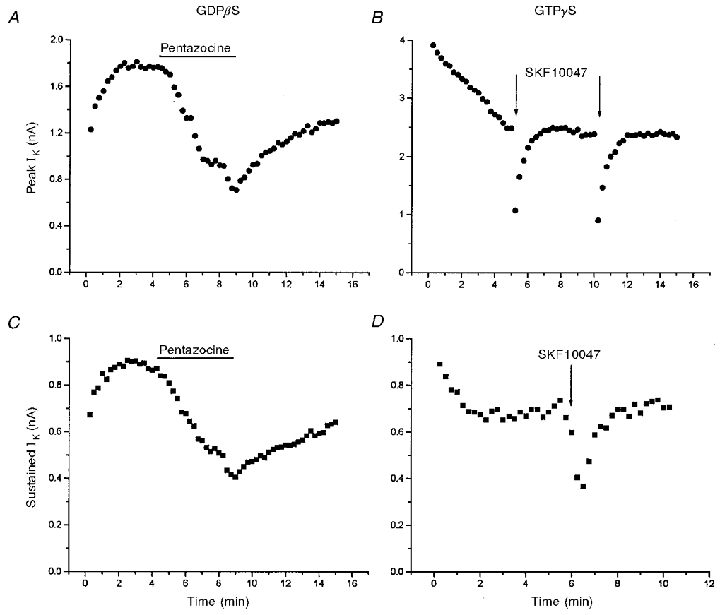

Tests for G-proteins

G-proteins can mediate membrane responses either by directly interacting with ion channels or by activating enzymes to generate second messengers. These two forms of transduction are quite general, and operate in a vast number of systems in which receptor occupancy leads to ion channel modulation (Hille, 1992; Wickman & Clapham, 1995; Breitwieser, 1996; Schneider et al. 1997). To test the role of G-proteins in sigma receptor-mediated responses we used the patch pipette filling solution to perfuse nerve terminals internally with a GTP-free solution, the GDP analogue GDBβS, or the GTP analogue GTPγS. All these manipulations have been shown to eliminate responses mediated by G-proteins, with response amplitudes diminished by ∼75 % after 2 min of internal perfusion (Trussell & Jackson, 1987). Sigma receptor ligands still reversibly inhibited IK in nerve terminals subjected to each of these three manipulations. The pentazocine response was unaffected by internal perfusion with 1 mM GDPβS (Fig. 3A and C), and the SKF10047 response was unaffected by internal perfusion with 100 μm GTPγS (Fig. 3B and D). (In Fig. 3B and D the drug was applied by pressure ejection from a micropipette positioned about 10 μm from the nerve terminal, so the onset and recovery are much faster than those achieved by bath application of drug shown in Fig. 3A and C.) Even after 10 min of perfusion with GTPγS, the percentage reduction of peak IK by SKF10047 was the same (Fig. 3B). Similar repeat applications after >10 min of internal perfusion with 150 μm GDPβS also produced similar responses (data not shown). Figure 4 summarizes the results of inhibition of IK by pentazocine with GTP-free patch pipette solutions, and patch pipette solutions containing 150 μm and 1 mM GDPβS. For all these conditions the reduction of both peak and sustained components of IK by 100 μm pentazocine was the same as control recordings in which cells were perfused with GTP (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

IK modulation and G-protein perturbation

Pentazocine (100 μm) reversibly reduced both peak (A) and sustained (C) IK in a nerve terminal perfused with 1 mM GDPβS (IK evoked by 250 ms pulses from -100 to 50 mV). SKF10047 (100 μm) reversibly inhibited both peak (B) and sustained (D) IK in a nerve terminal filled with 100 μm GTPγS (IK evoked by 250 ms pulses from -80 to 10 mV). In A and C, pentazocine was added to the bathing solution; both plots are taken from the same recording. In B and D, SKF10047 was applied by pressure ejection of an ≈2 μm diameter-tipped micropipette positioned within 10 μm of the nerve terminal under recording; the plots are from different recordings. The different time courses of inhibition and recovery reflect the different modes of drug application. GDPβS and GTPγS began to perfuse the cell interior at break-in, shortly before data acquisition was started. The increase (A and C) in IK at the beginning of the experiment with GDPβS (prior to drug application) results from block of G-protein-dependent modulation of channels. The decrease (B and D) in IK at the beginning of the experiment with GTPγS results from the enhancement of this modulation (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994).

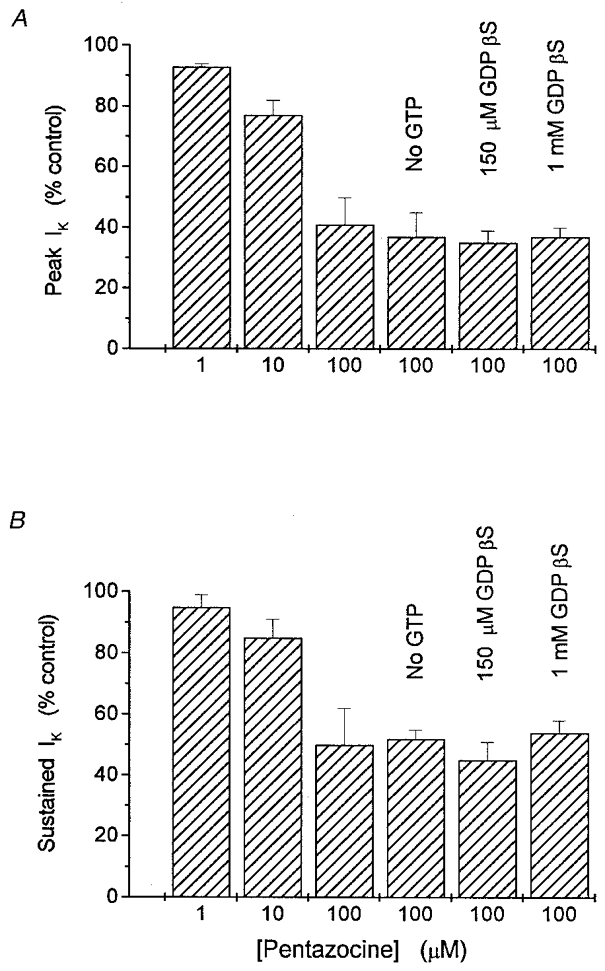

Figure 4.

Means of peak (A) and sustained (B) IK in the presence of the indicated concentrations of pentazocine (normalized to predrug control IK level)

Increasing pentazocine from 1 to 100 μm resulted in greater reductions of both components. The reduction by 100 μm pentazocine was the same in recordings with 150 μm or 1 mM GDPβS instead of GTP, or with GTP-free intracellular recording solutions. n = 3 to 6 nerve terminals for each result shown; IK was evoked by 250 ms pulses from -80 to 10 mV.

The time course of whole-terminal IK shown in Fig. 3 also provides a positive control for the effectiveness of thioguanine nucleotides in this experimental protocol. Previous work from this laboratory has shown that GTPγS activates a protein phosphatase in excised patches of nerve terminal membrane, and this initiates a rapid rundown of activity of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel responsible for IBK (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994). Here we found that adding 100 μm GTPγS to the patch pipette solution caused a decline in IK in the first few minutes after establishing a whole-terminal recording (Fig. 3B and D). Likewise, perfusion with GDPβS produced an increase in IK immediately following break-in (Fig. 3A and C). Both of these guanine nucleotide effects were seen prior to application of sigma receptor ligands, and show that G-proteins are modulating channel activity independently of receptor activation, presumably by altering the level of protein phosphorylation within the nerve terminal. The decline in peak IK was variable in time course and extent, and sometimes continued for several minutes. This probably reflects multiple forms of G-protein-mediated modulation of the K+ channels underlying this current. On the other hand, the rapid changes in sustained IK are consistent with the finding that membrane-bound G-proteins rapidly activate a membrane-bound protein phosphatase in this system (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994).

Based on diffusion, molecules of the size of GTP can be expected to perfuse cells in about 8 s in whole-cell recordings (Pusch & Neher, 1988; Jackson, 1997). This figure in seconds was arrived at using the formula:

where M was taken as the molecular mass of GTPγS (456 Da), Cc was the capacitance of a typical nerve terminal (5 pF) and Rs was a typical series resistance value (5 MΩ). Since the time taken for current to change during intracellular perfusion is of the order of a minute (Fig. 3), it is probably the kinetics of nucleotide binding and effector activation that is rate limiting, rather than diffusion of the guanosine nucleotides into the nerve terminals.

The fact that neither GDPβS, GTPγS nor GTP-free intracellular solutions reduced responses to pentazocine or SKF10047 indicates that G-proteins are not required for the sigma receptor-mediated modulation of neurohypophysial IK. Both peak and sustained IK were reduced by the same amount as in control experiments (Fig. 4). Since peak IK reflects predominantly IA and sustained IK reflects predominantly IBK (Wilke et al. 1998), this result indicates that both types of K+ channels can be modulated independently of G-proteins. Additional experiments with excised patches described below provide further support for this conclusion.

Tests for protein phosphorylation

Protein phosphorylation regulates the activity of many ion channels (Levitan, 1994; Jonas & Kaczmarek, 1996; Breitwieser, 1996). This form of channel modulation may or may not involve G-proteins. The production of second messengers that activate protein kinases generally depends on G-proteins, but many receptors have intrinsic, G-protein-independent protein kinase activity. To investigate the role of protein phosphorylation in the sigma receptor-mediated modulation of K+ channels, recordings were made with patch pipettes containing the nonhydrolysable ATP analogue AMPPcP in place of ATP, and with 50 nM okadaic acid, a protein phosphatase inhibitor (okadaic acid was included to block protein phosphatase activity and prevent the run-down of K+ channels that occurs with AMPPcP in place of ATP; Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994). Under these conditions SKF10047 still reduced both peak and sustained IK. Figure 5 shows a time course of IK inhibition and recovery in two successive rounds of drug application. Peak and sustained IK were reduced to 43 ± 7 and 54 ± 3 % of control (n = 4), and this inhibition of IK was indistinguishable from that seen in control whole-terminal recordings (P = 0.18 and 0.21, for the probabilities of originating from the same distribution with peak and sustained IK, respectively). In this preparation, AMPPcP and okadaic acid have proven effective in interfering with phosphorylation and dephosphorylation-dependent modulation of K+ channels. These reagents produce significant changes in the whole-terminal IK within 2 or 3 min of break-in (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994). This provides a positive control to verify the utility of these reagents.

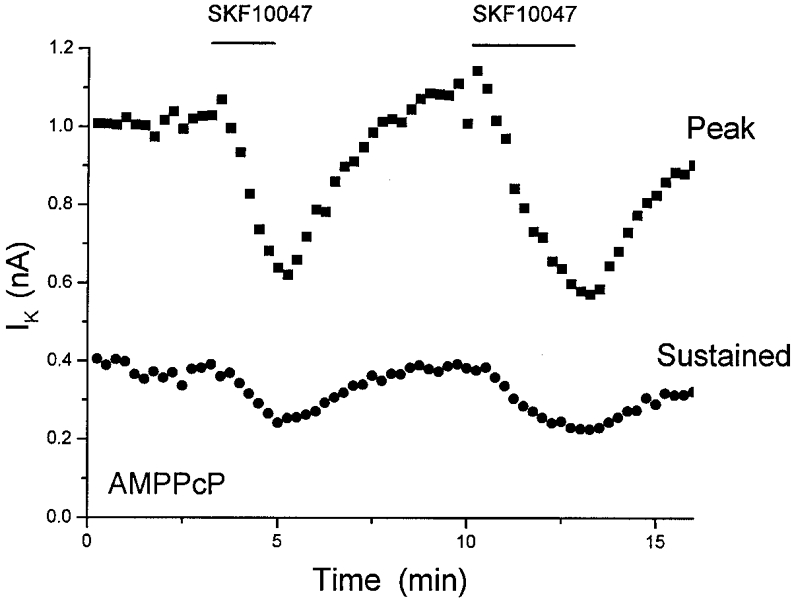

Figure 5.

Sigma receptor-mediated inhibition is independent of ATP

ATP (2 mM) was replaced in the patch pipette solution by 2 mM AMPPcP. Protein phosphatase was also blocked by adding 50 nM okadaic acid. SKF10047 (100 μm) was applied twice (indicated by bars) to demonstrate two cycles of response and recovery. As in Fig. 3, internal perfusion began at break-in, ≈3 min before the first application of SKF10047. Both peak and sustained IK were inhibited, and recovered after drug removal (mean reduction given in text).

These experiments show that sigma receptor-mediated modulation of IK does not depend on ATP hydrolysis, and presumably does not require protein phosphorylation. Since okadaic acid was present at levels sufficient to block either protein phosphatase 1 or 2a (Shenolikar & Nairn, 1991), it would appear that these enzymes are also not involved. Further, the involvement of other forms of protein phosphatase can be ruled out because recovery from dephosphorylation would depend on protein phosphorylation, and Fig. 5 shows two cycles of response and recovery under conditions where phosphorylation is blocked.

Channel modulation in membrane patches

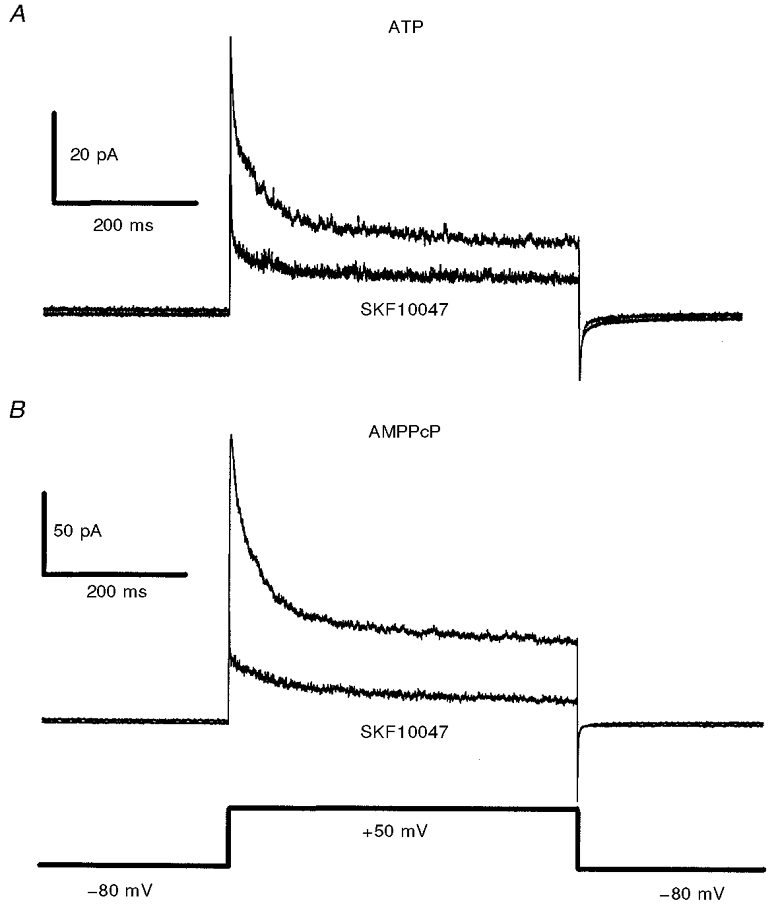

The formation of excised outside-out patches (Hamill et al. 1981) provides a convenient way of isolating ion channels from the cytoplasm and determining the molecular dependence of a membrane transduction process. Figure 6 shows the inhibition of K+ channel activity in outside-out patches by 100 μm SKF10047. With the normal ATP-GTP-containing control pipette solution (see Methods), peak and sustained IK were reduced to 42 ± 6 and 60 ± 6 % of control values, respectively (n = 10). Following replacement of ATP by AMPPcP, and addition of okadaic acid to block membrane-bound protein phosphatase (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1994), SKF10047 still reduced these components of IK to 55 ± 9 and 63 ± 12 % of control values, respectively (n = 5). The inhibition of IK in excised outside-out patches was statistically indistinguishable from that seen in whole-terminal recordings with the same pipette solution (P = 0.17 and 0.25 for peak and sustained IK, respectively), as well as in outside-out patches with control solution (P = 0.13 and 0.40 for peak and sustained IK, respectively). These results show that the response to sigma receptor activation does not depend on soluble cytoplasmic factors, and confirm the findings from whole-terminal recordings above, that channel modulation does not depend on protein phosphorylation, dephosphorylation or G-protein activation. Furthermore, these experiments indicate that the sigma receptor binding site is located in the plasma membrane, and this is of interest because the deduced amino acid sequence of the sigma receptor contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence (Kekuda et al. 1996; Hanner et al. 1996).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of peak and sustained IK by SKF10047 in outside-out patches

A, IK reduction in outside-out patches with the control pipette solution containing 2 mM ATP. B, IK reduction in outside-out patches with 50 nM okadaic acid and 2 mM AMPPcP in the patch pipette (no ATP). Voltage pulses 300 ms in duration from -80 mV to 50 mV activated IK. Averages of ten traces are shown (collected at 15 s intervals) for both predrug control and after 1 min exposure to SKF10047 (100 μm). IK recovered to predrug levels within 1 min of drug removal (data not shown). IK recorded from outside-out patches is nearly identical in time course but smaller in amplitude compared with typical whole-terminal IK (e.g. Fig. 1).

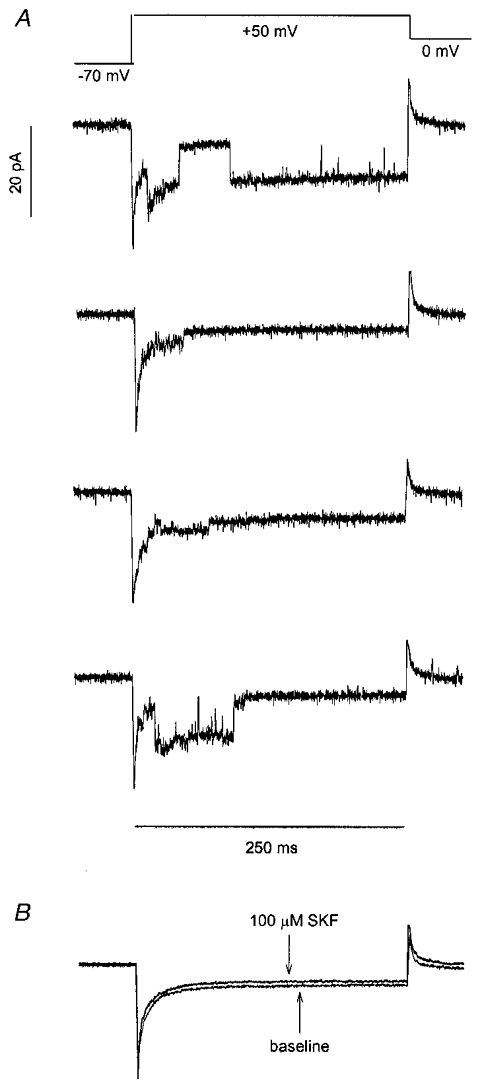

To investigate the need for close proximity between sigma receptors and the target ion channels modulated in nerve terminal membranes, experiments were conducted in cell-attached patches. This experimental configuration isolates the patch of membrane under recording from the rest of the membrane of the nerve terminal. Thus, receptors outside a patch can be presented with drug, and the effect on channels within a patch can be monitored. In the case of responses mediated by a soluble intracellular second messenger, the modulation of ion channels in cell-attached patches can be elicited by the bath application of receptor ligands (Siegelbaum et al. 1982). Single K+ channel currents are readily recorded in cell-attached patches in neurohypophysial nerve terminals (Bielefeldt et al. 1992), and superfusion of the preparation with SKF10047 produced only a small reduction in channel activity (Fig. 7). IK measured 10 ms after the start of a depolarizing pulse was reduced to 87 ± 6 % of the predrug control IK (n = 10). This is much less than the reduction in IK at this same time point seen in outside-out patches with ATP (41 ± 6 %, n = 9) or okadaic acid + AMPPcP (57 ± 9 %, n = 5), and these differences were statistically significant (P = 0.0005 and 0.007, respectively). Figure 7 shows that there was little reduction in IK for the duration of the depolarizing pulse. Due to their different activation and inactivation kinetics (Bielefeldt et al. 1992), inhibition of either IA or IBK would have reduced IK either early or late in the pulse, respectively. Thus, in cell-attached patches neither of these K+ channels was appreciably modulated by externally applied drug. The slight reduction of IK in these experiments is probably due to the lipophilic nature of SKF10047, enabling a small amount of drug leakage through the cell membrane and into the region sealed off by the patch pipette.

Figure 7.

K+ channels in cell-attached patches

Cell-attached patches were hyperpolarized to -110 mV for 250 ms (to remove inactivation, see Bielefeldt et al. 1992), then depolarized to 50 mV for 300 ms to activate K+ channels. Prior hyperpolarization has been shown to leave the percentage reduction of IK by sigma receptor ligands unchanged (Wilke et al. 1999b). Voltage was estimated by assuming a resting membrane potential of -70 mV. A, four sweeps show single channel activity through A-current and Ca2+-activated K+ channels under control conditions. B, averages of 25 sweeps were recorded before and after application of 100 μm SKF10047 to the bathing solution. SKF10047 reduced current only slightly in these experiments because the drug could not reach the membrane under the pipette tip in which channel activity was recorded.

The failure to see channel modulation in cell-attached patches indicates that receptors in the cell membrane located outside the walls of the patch pipette tip cannot modulate channels inside the patch of membrane sealed off by the electrode. The wall thickness of a typical patch electrode is generally of the order of < 1 μm. Thus, separating sigma receptors from target K+ channels by this distance prevented the transmission of signals between these two membrane proteins.

Failure of ligands to modulate K+ channels in the absence of sigma receptors

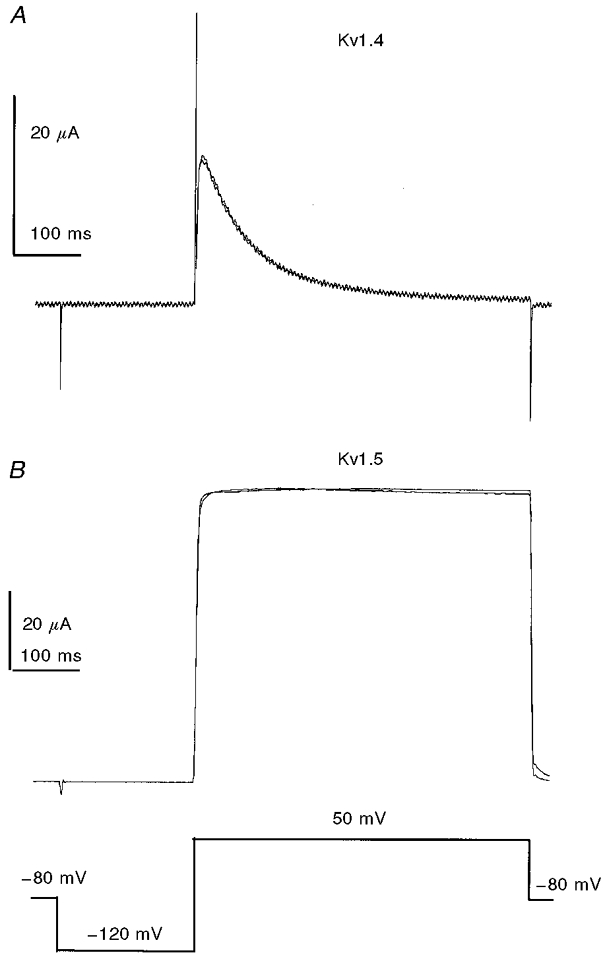

The findings that G-proteins, ATP and cytoplasmic factors were not required for ion channel modulation by sigma receptor ligands raise the possibility that ligands interact directly with the ion channel protein itself. The molecular structure of sigma receptors strongly suggests that it is incapable of forming ion channels (Hanner et al. 1996; Kekuda et al. 1996; Seth et al. 1997). The existence of antagonists that can block the action of sigma receptor agonists without inhibiting K+ currents on their own (Wilke et al. 1998) argues against a mechanism of K+ current inhibition involving open channel block. As an additional test that the modulation of K+ channels by sigma receptor ligands does indeed depend on the presence of the sigma receptor we expressed voltage-gated K+ channels in Xenopus oocytes and applied sigma receptor ligands to see if these K+ channels were inhibited.

For these experiments we selected the mammalian homologue of the Drosophila Shaker K+ channel, Kv1.4. This channel has biophysical properties that are similar to those of the A-current channel of the posterior pituitary, and has been shown to be localized in nerve terminals (Sheng et al. 1993). Neither SKF10047 (Fig. 8; n = 8; 100 μm) nor ditolylguanidine (n = 6; 100 μm) had any effect on K+ current in oocytes expressing Kv1.4. Further experiments with the related K+ channel Kv1.5 produced the same result in five experiments with SKF10047 and seven with ditolylguanidine. For both these channels, K+ current was inhibited when the K+ channels were expressed together with sigma receptors, and the amount was somewhat greater than that seen in nerve terminals (Aydar et al. 2000). Thus, the modulation of K+ channels by these drugs requires the sigma receptor, and does not result from direct interactions between the ligand and the channel protein.

Figure 8.

Lack of modulation of K+ channels in the absence of sigma receptor

The voltage-gated K+ channels Kv1.4 and Kv1.5 were expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes by injecting mRNA encoding for these proteins. Voltage steps from -120 to +50 mV activated K+ current. Addition of 100 μm SKF10047 left the current essentially unchanged in 8 oocytes expressing Kv1.4 (A) and 5 oocytes expressing Kv1.5 (B). Another sigma receptor agonist, ditolylguanidine, also failed to modulate K+ current (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study has shown that signal transduction by sigma receptors does not depend on any of the well-established molecular systems known to operate in the receptor-mediated modulation of membrane excitability. Although the basic phenomenon of modulation of voltage-gated channels has been encountered many times, in every instance where the transduction mechanism was investigated, G-proteins or protein phosphorylation have been shown to play a role (Hille, 1992; Levitan, 1994; Wickman & Clapham, 1995; Breitwieser, 1996; Jonas & Kaczmarek, 1996; Schneider et al. 1997). However, we found that neither GTPγS nor GDPβS interfered with sigma receptor-mediated modulation of IK, even as initial changes in current amplitude provided a report of the effectiveness of these reagents in manipulating G-proteins. Likewise, removal of ATP and blockade of protein phosphorylation left signal transduction intact. These findings therefore imply a novel mechanism of signal transduction, in keeping with the novel structure of the sigma receptor protein.

Our finding of G-protein-independent transduction by sigma receptors is consistent with previous work from this laboratory on the modulation of IK in a lung tumour cell line (Wilke et al. 1999b). Another group reported similar results for sigma receptor-mediated modulation of K+ channels in a neuroblastoma cell line (Morio et al. 1994). However, a number of other studies have suggested that sigma receptors may interact with G-proteins and regulate protein phosphorylation (Su, 1993; Nakazawa et al. 1995; Soriani et al. 1998, 1999). Some of these effects could be interpreted as Ca2+-dependent processes that are indirect consequences of ion channel modulation (Brent et al. 1997). The mechanism of signal transduction may also depend on what is chosen experimentally as the physiological endpoint. Sigma receptors may have other physiological functions and it has been suggested that they initiate processes other than the modulation of ion channels (Moebius et al. 1997). It is possible that some sigma receptor-mediated responses employ other transduction mechanisms. With regard to the reports suggesting an involvement of G-proteins in ion channel modulation (Nakazawa et al. 1995; Soriani et al. 1998, 1999) it is also possible that sigma receptor variants differ in their coupling to G-proteins (Bowen, 1994), and this has been proposed as a resolution of the differences in the literature regarding effector pathways employed by sigma receptors (Soriani et al. 1999).

The photolabelling data from the neurohypophysis presented here (Fig. 2C) suggest that sigma receptor ligands interact with a 26 kDa protein similar in molecular mass to the sigma receptor protein identified by molecular cloning. Further, in DMS-114 human lung tumour cells, where better photolabelling signals were obtained, the concentration dependence of blockade of photolabelling by SKF10047 was found to be very similar to the concentration dependence of inhibition of IK (Wilke et al. 1999b). These results indicate that the receptor that modulates K+ channels in tumour cells also has a molecular mass of 26 kDa, thus identifying it with the cloned sigma receptor.

Ordinarily, the observation that ion channels can be modulated in excised outside-out patches, with G-proteins and ATP hydrolysis blocked (Fig. 6), is diagnostic of a ligand-gated channel in which the receptor and channel are part of the same protein. However, the sigma receptor does not have the amino acid sequence or the membrane topology of an ion channel (Hanner et al. 1996; Kekuda et al. 1996; Seth et al. 1997), and the photolabelling results obtained with IAC suggest that this protein does indeed mediate the modulation of K+ channels. Furthermore, the photolabelling results indicate that the actions of sigma receptor ligands are mediated by a protein with a molecular mass smaller than the channels that are modulated. The two K+ channels inhibited by sigma receptor ligands produce the A-current and a Ca2+-activated K+ current (Bielefeldt et al. 1992). The molecular mass deduced from the genes of members of these protein families are 73 and 134 kDa, respectively. Accessory or auxiliary subunits of voltage-gated channels are smaller, and if these drugs interact with such a protein, then it would coincidentally have the same molecular mass as the cloned sigma receptor.

The size of the photolabelled protein makes it unlikely that the inhibition of IK by sigma receptor ligands results from direct blockade of open channels (such as that produced by local anaesthetics). The hypothesis of open channel block is also inconsistent with the fact that in this same preparation two antagonists, eticlopride and RBI257, were shown to block the modulation of IK by sigma receptor agonists, without producing any inhibition of current on their own (Wilke et al. 1998). Finally, when K+ channels are expressed in oocytes in the absence of sigma receptors, there is no modulation (Fig. 8). Only when both channel and receptor proteins were expressed in oocytes could the K+ current be inhibited by sigma receptor ligands (Aydar et al. 2000). Thus, the inhibition of K+ channels by sigma receptor agonists does not arise from direct interactions of these ligands with the channel itself.

Since sigma receptors and ion channels are distinct proteins, there must be a relay mechanism to transmit the signal of binding site occupancy to the target ion channels. Since G-proteins, protein kinases, protein phosphatases and soluble cytoplasmic molecules were ruled out by the results of the present study, and since the results with cell-attached patches indicate a requirement for close proximity between the receptor and channel, the most parsimonious explanation is that the transduction signal is mediated by protein- protein interactions within the cell membrane. These interactions could be through a direct association between the receptor and channel, and this mechanism is especially appealing in its simplicity. It is also possible that the coupling between the receptor and channel is mediated by other proteins, which would then also be membrane bound. Thus, the sigma receptor could either behave like, or activate, a minK-like protein. With a single membrane-spanning segment this protein resembles the sigma receptor in overall topology. It cannot form a channel by itself but can modify the activity of other voltage-gated K+ channels (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Barhanin et al. 1996). Auxiliary β-subunits are another example of membrane proteins that do not form channels themselves, but can modify ion channel activity (Adelman, 1995; England et al. 1995). Sigma receptor activation could lead to a similar modification of K+ channels, but in a ligand-dependent manner. The recently described receptor-activity-modifying protein (RAMP) has a single membrane-spanning segment and regulates the transport and functional activity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor (McLatchie et al. 1998). From this perspective the sigma receptor may act in an analogous manner as a channel-activity-modifying protein. Direct functional interaction between integral membrane proteins such as these appears to be an emerging theme in physiology, as similar mechanisms have been proposed for neurotrophin receptor-mediated modulation of Na+ channels (Kafitz et al. 1999), and mutual modulation between GABAA receptors and dopamine D5 receptors (Liu et al. 2000).

Since the molecular characterization of the sigma receptor has occurred only recently, it is difficult to speculate whether its mode of signal transduction is widely used. Sigma receptor homologues may or may not exist, but to date none have been described. The sigma receptor itself is ubiquitously distributed in vertebrates, and has been implicated in a wide range of biological functions (Bowen, 1993; Su, 1993). The neurohypophysis has a high density of sigma receptors (Wolfe et al. 1989), and in this preparation the sigma receptor-mediated reduction of IK would be expected to enhance the release of neuropeptide hormones. Future work will clarify the physiological processes that depend on sigma receptors, and as this work progresses it will be interesting to see if a biological principle emerges for functions that are better served by the sigma transduction process.

Endogenous ligands that activate sigma receptors have not been identified. Although the sigma receptor binds progesterone (Su et al. 1988), concentrations of this steroid of up to 1 mM were tested and found to have no impact on the modulation of IK in the neurohypophysis (Wilke et al. 1999a). A number of additional candidate ligands, including catecholamines, peptides and other steroids, were also tested with negative results. Given the potent modulation of IK in every nerve terminal tested, it would appear that if endogenous chemical signals enter the neurohypophysis and activate sigma receptors, the release of the two neurohypophysial peptides, oxytocin and vasopressin, would both be enhanced. The inhibition of IK would prolong individual action potentials (Jackson et al. 1991) as well as increase the duration of action potential bursts (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1993), and both of these would increase the release of hormone. Thus, the transduction mechanism employed by sigma receptors is likely to play a role in endocrine functions, both in the neurohypophysis and other endocrine systems in which sigma receptors are found.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by NIH Grant NS30016 to M.B.J. P.J.L. is a Hilldale Fellow and R.A.W. is a trainee in the Clinical Investigator Pathway of the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics.

References

- Adelman JP. Proteins that interact with the pore-forming subunits of voltage-gated ion channels. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1995;5:286–295. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydar E, Palmer C, Jackson M. Modulation of Kv1.4 K+ channels by sigma receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:98A. [Google Scholar]

- Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. KVLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKscardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beart PM, O'shea RD, Manallack DT. Regulation of σ-receptors: high- and low-affinity agonist states, GTP shifts, and upregulation by rimcazole and 1,3-di(2-tolyl)guanidine. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;53:779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb11773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Jackson MB. A calcium-activated potassium channel causes frequency-dependent action-potential failures in a mammalian nerve terminal. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:284–298. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Jackson MB. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation modulate a Ca2+-activated K+ channel in rat peptidergic nerve terminals. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;475:241–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Rotter JL, Jackson MB. Three potassium channels in rat posterior pituitary nerve endings. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;458:41–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WD. Biochemical pharmacology of sigma receptors. In: Stone TW, editor. Aspects of Synaptic Transmission. Washington DC, USA: Taylor and Francis; 1993. pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WD. Interaction of sigma receptors with signal transduction pathways and effects of second messengers. In: Itzhak Y, editor. Sigma Receptors. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Breitwieser GE. Mechanisms of K+ channel regulation. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;152:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002329900080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent PJ, Herd L, Saunders H, Sim ATR, Dunkley PR. Protein phosphorylation and calcium uptake into rat forebrain synaptosomes: modulation by the σ ligand, 1,3-ditolylguanidine. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68:2201–2211. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Costa BR, He X-S. Structure-activity relationships and evolution of sigma receptor ligands (1976-present) In: Itzhak Y, editor. Sigma Receptors. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 45–111. [Google Scholar]

- England SK, Uebele VN, Kodali J, Bennett PB, Tamkun MM. A novel K+ channel β-subunit (hKvβ1.3) is produced via alternative mRNA splicing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:28531–28534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanner M, Moebius FF, Flandorfer A, Knaus H-G, Striessnig J, Kempner E, Glossman H. Purification, molecular cloning, and the expression of the mammalian sigma-1 binding site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:8072–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. G protein-coupled mechanisms and nervous signaling. Neuron. 1992;9:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90158-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y. Multiple affinity binding states of the σ receptor: effect of GTP-binding protein-mediated agents. Molecular Pharmacology. 1989;36:512–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB. Whole-cell patch clamping. In: Rogowski M, editor. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 6.6.1–6.6.30. New York: John Wiley Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Konnerth A, Augustine GJ. Action potential broadening and frequency-dependent facilitation of calcium signals in pituitary nerve terminals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:380–384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jbilo O, Vidal H, Paul R, Nys ND, Bensaid M, Silve S, Carayon P, Davi D, Galiegue S, Bourrie B, Guillemot L-C, Ferrara P, Loison G, Maffrand J-P, Fur GL, Casellas P. Purification and characterization of the human SR 31747A-binding protein: a nuclear membrane protein related to yeast sterol isomerase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:27107–27115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas EA, Kaczmarek LK. Regulation of potassium channels by protein kinases. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:318–323. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Rose CR, Thoenen H, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin-evoked rapid excitation through TrkB receptors. Nature. 1999;401:918–921. doi: 10.1038/44847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahoun JR, Ruoho AE. (125I)Iodoazidococaine, a photoaffinity label for the haloperidol-sensitive sigma receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:1393–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekuda R, Prasad PD, Fei Y-J, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cloning and functional expression of the human type 1 sigma receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;229:553–558. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan IB. Modulation of ion channels by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wan Q, Pristupa ZB, Yu X-M, Wang YT, Niznik HB. Direct protein-protein coupling enables cross-talk between dopamine D5 and γ-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Nature. 2000;403:274–280. doi: 10.1038/35002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLatchie LM, Fraser NJ, Main MJ, Wise A, Brown J, Thompson N, Solari R, Lee MG, Foord SM. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Eades CG, Thompson JA, Huppler RE, Gilbert PE. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine-like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1976;197:517–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moebius FF, Striessnig J, Glossman H. The mysteries of sigma receptors – new family members reveal a role in cholesterol synthesis. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1997;18:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio Y, Tanimoto H, Yakushiji T, Morimoto Y. Characterization of the currents induced by sigma ligands in NCB20 neuroblastoma cells. Brain Research. 1994;637:190–196. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Ito K, Koizumi S, Ohno Y, Inoue K. Characterization of inhibition by haloperidol and chlorpromazine of a voltage-activated K+ current in rat phaeochromocytoma cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;116:2603–2610. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Neher E. Rates of diffusional exchange between small cells and a measuring patch pipette. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;411:204–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00582316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusin KI, Giovannucci DR, Stuenkel EL, Moises HC. κ-Opioid receptor activation modulates Ca2+ currents and secretion in isolated neuroendocrine nerve terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:6565–6574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06565.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, Keating MT. Coassembly of KVLQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Igelmund P, Hescheler J. G-protein interaction with K+ and Ca2+ channels. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1997;18:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cloning and structural analysis of the cDNA and the gene encoding the murine type 1 sigma receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;241:535–540. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Presynaptic A-current based on heteromultimeric K+ channels detected in vivo. Nature. 1993;365:72–75. doi: 10.1038/365072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenolikar S, Nairn AC. Protein phosphatases: recent progress. Advances in Second Messenger and Phosphoprotein Research. 1991;23:1–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegelbaum SA, Camardo JS, Kandel ER. Serotonin and cAMP close single K+ channels in Aplysia sensory neurons. Nature. 1982;299:413–417. doi: 10.1038/299413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriani A, Le Foll F, Roman F, Monnet FP, Vaudry H, Cazin L. A-current down-modulated by σ receptor in frog pituitary melanotrope cells through a G protein-dependent pathway. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;289:321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriani O, Vaudry H, Mei YA, Roman F, Cazin L. Sigma ligands stimulate the electrical activity of frog pituitary melanotrophs through G-protein dependent inhibition of potassium conductances. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;286:163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T-P. Delineating biochemical and functional properties of sigma receptors: Emerging concepts. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology. 1993;7:187–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T-P, London ED, Jaffe JH. Steroid binding at sigma receptors suggests a link between endocrine, nervous and immune systems. Science. 1988;240:219–221. doi: 10.1126/science.2832949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyama S, Hirata K, Ide A, Ueda H. Sigma ligands stimulate GTPase activity in mouse prefrontal membranes: Evidence for existence of metabotropic sigma receptor. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;233:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00657-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell LO, Jackson MB. Dependence of an adenosine-activated potassium current on a GTP-binding protein in mammalian central neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:3306–3316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03306.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickman KD, Clapham DE. Ion channel regulation by G-proteins. Physiological Reviews. 1995;75:865–885. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke RA, Hsu S-F, Jackson MB. Dopamine D4 receptor mediated inhibition of potassium current in neurohypophysial nerve terminals. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;284:542–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke RA, Lupardus PJ, Grandy DK, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Jackson MB. K+ channel modulation in rodent neurohypophysial nerve terminals by sigma receptors and not by dopamine receptors. The Journal of Physiology. 1999a;517:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke RA, Mehta RP, Lupardus PJ, Chen Y, Ruoho AE, Jackson MB. Sigma receptor photolabeling and sigma receptor-mediated modulation of potassium channels in tumor cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999b;274:18387–18392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe SA, Culp SG, De Souza EB. σ-Receptors in endocrine organs: identification, characterization, and autoradiographic localization in rat pituitary, adrenal, testis, and ovary. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1160–1172. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-3-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]