Abstract

In pre-eclampsia, a functional change occurs in the role played by endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) in the regulation of smooth muscle contraction in resistance arteries. We investigated the underlying mechanism in human omental resistance arteries from normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women in the presence of diclofenac (an inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenase).

In endothelium-intact strips, the sensitivity to 9,11-epithio-11,12-methano-thromboxane A2 (STA2) was significantly higher in pre-eclampsia, and this was not modified by either NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA, an inhibitor of NO synthase) or removal of the endothelium.

Bradykinin and substance P each produced an endothelium-dependent relaxation of the STA2-induced contraction in both groups, although the relaxation was significantly smaller for pre-eclampsia. l-NNA markedly attenuated the endothelium-dependent relaxation in the normotensive pregnant group but not in the pre-eclamptic group.

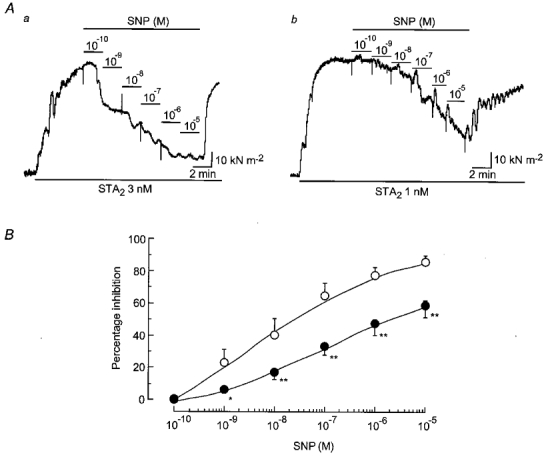

In the presence of l-NNA, the relaxation induced by sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on the STA2 contraction was significantly smaller for pre-eclamptic than for normotensive pregnant women.

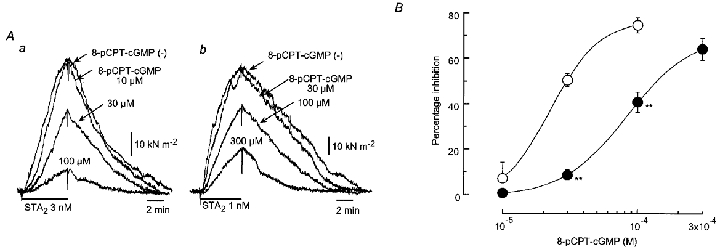

In endothelium-denuded strips, the relaxation induced by 8-para- chlorophenyl thio-guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pCPT-cGMP) on the STA2 contraction was significantly less for pre-eclampsia.

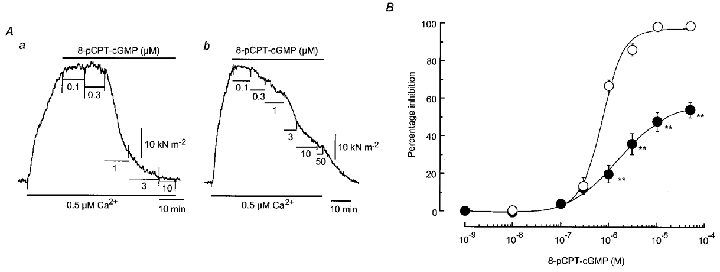

In β-escin-skinned strips from both groups of women, 8-pCPT-cGMP (1–10 μm) concentration-dependently attenuated the contraction induced by 0.5 μm Ca2+. However, its relaxing action was significantly weaker in pre-eclampsia.

It is suggested that the weaker responsiveness to NO seen in strips from pre-eclamptic women may be partly due to a reduced smooth muscle responsiveness to cyclic GMP.

Vascular endothelial cells release vasorelaxing factors, such as nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) and these play an important role in the regulation of vascular tone, vascular permeability and blood coagulation, thus helping to maintain circulatory homeostasis (Vallance et al. 1989; Moncada et al. 1991; Kuriyama et al. 1998). NO is known to be a potent vasodilator and to be important in regulating peripheral vascular resistance. During human pregnancy, blood volume and cardiac output increase while blood pressure and peripheral vascular resistance decrease (Robson et al. 1989). Endothelium-derived NO is thought to play a pivotal role in the decrease in peripheral vascular resistance in pregnancy, although its relative contribution varies depending both on the vascular bed and the vessel size (Roberts et al. 1989; Sladek et al. 1997).

Pre-eclampsia is characterized by marked increases in peripheral vascular resistance and vascular permeability together with a disturbance of blood coagulation (Lenfant et al. 1990; Cines et al. 1998; Cunningham, 1998). It has been suggested that an abnormality in the role played by endothelium-derived NO in resistance arteries may be involved in the pathogenesis and/or development of pre-eclampsia (Poston et al. 1995; Sladek et al. 1997). On the basis of experiments on isolated human resistance arteries, one report suggested that bradykinin-induced, NO-dependent relaxation is reduced in subcutaneous fat arteries in pre-eclampsia (compared with the response in normotensive pregnant women) (Knock & Poston, 1996). Recently, evidence has accumulated to suggest that the production of NO in endothelial cells may be increased in pre-eclampsia (Baker et al. 1995; Davidge et al. 1995; Bartha et al. 1999; Norris et al. 1999; Ranta et al. 1999). It was recently suggested that in the aorta of mice overexpressing endothelial NO synthase, NO-mediated smooth muscle relaxation would be reduced if the production of endothelium-derived NO were chronically increased (Ohashi et al. 1998). Thus, it might be expected that a similar desensitization to NO might develop if the release of endothelium-derived NO actually is enhanced in vascular beds in pre-eclampsia. However, the mechanism underlying the reduced response to endothelium-derived NO seen in resistance vessels in pre-eclampsia has not yet been clarified.

When pre-eclamptic women are compared with normotensive pregnant women, the contractile responses to angiotensin II (Gant et al. 1973; Aalkjaer et al. 1985) and vasopressin (Pascoal et al. 1998) are seen to be increased in omental resistance arteries, while that to noradrenaline is enhanced in epigastric arteries (Ebeigbe & Ezimokhai, 1988) but not in small subcutaneous arteries (McCarthy et al. 1993). Recently, much attention has been paid to the role of thromboxane A2, a very potent vasoconstrictor and platelet-aggregating agent, in the pathogenesis and development of pre-eclampsia (Sladek et al. 1997). If a dysfunction of the endothelium does occur in resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia, it might be expected that less prostacyclin would be produced in a given vessel, leading to an acceleration of platelet aggregation and a subsequent release of thromboxane A2 (Roberts et al. 1989). However, it remains unknown whether the responsiveness of resistance arteries to thromboxane A2 is altered in pre-eclampsia.

We first investigated whether or not characteristic changes in the contractile response to thromboxane A2 do develop in omental resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia. Since the degradation of thromboxane A2 is rapid, a stable thromboxane analogue, 9,11-epithio-11,12-methano-thromboxane A2 (STA2, Kanmura et al. 1987) was used. Secondly, to test whether or not functional changes in the relaxation response to endothelium-derived NO do indeed develop in omental resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia, we studied the effects of bradykinin and substance P (to stimulate the endothelial release of NO) on the STA2-induced contraction seen in the presence of diclofenac (to prevent the production of prostanoids) in endothelium-intact strips. We also examined the changes occurring in the abilities of SNP (a NO donor, Feelisch & Noack, 1987) and 8-para-chlorophenyl thioguanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pCPT-cGMP, a phosphodiesterase-resistant cyclic GMP analogue) to relax the STA2-induced contraction (to test for changes in the responsiveness to NO and cyclic GMP in smooth muscle cells). In addition, we looked for a change in the action of cyclic GMP on contractile proteins by observing the effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP on the Ca2+-induced contraction in β-escin-skinned muscles.

METHODS

Preparations

Muscle strips were cut from omental resistance arteries (outer diameter, 0.1–0.3 mm) obtained from 29 normotensive pregnant and 15 pre-eclamptic women at the time of Caesarean section. Patients were matched for both maternal and gestational age (31 ± 1 vs. 30 ± 2 years old, 39 ± 1 vs. 37 ± 2 weeks of gestation, respectively). None of the patients was taking any medication (except for the anaesthetic given for the Caesarean section). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The procedures used in this study were approved by the institutional review boards of Nagoya City University Medical School. Pre-eclampsia was diagnosed according to the criteria suggested by the working group of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (Lenfant et al. 1990). Patient details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient details

| Normotensive | Preeclamptic | |

|---|---|---|

| patients | patients | |

| n | 29 | 15 |

| Age (years) | 31 ±1 | 30 ±2 |

| Parity (primiparous/multiparous) | 20/9 | 13/2 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39 ±1 | 37 ±1 |

| Blood pressure | ||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 115 ±3 | 163 ±9* |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 71 ±9 | 107 ±8* |

| Proteinuria (g l−1) | — | 4.0 ±2.1 |

| Generalized oedema | — | 5/10 |

| Platelet count (1 × 109cells l−1) | 308 ±21 | 191 ±45* |

| Uric acid (mg dl−1) | 4.2 ±0.1 | 5.8 ±0.4* |

| Urinary calcium/creatinine | 0.13 ±0.04 | 0.03 ±0.02* |

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.The number of patients used is given in parentheses.

Significance was assumed if P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

The tissue specimens were immediately placed in Krebs solution and transported to the laboratory. Omental artery segments (3 cm in length) were excised and the tissues were prepared as follows in Krebs solution at room temperature. The connective tissue was carefully removed under a binocular microscope and the artery was then cut along its long axis with small scissors so as not to damage the endothelium. Small circularly cut muscle strips with intact endothelium (0.1–0.3 mm in width, 0.05–0.08 mm in thickness, 0.3–0.4 mm in length) were then prepared, as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992a,b;Yamakawa et al. 1997). The usefulness of this preparation in investigations of endothelium-dependent responses in small resistance arteries has been reported previously following studies involving measurements of isometric tension (Nishiye et al. 1989), membrane potential changes (Yamakawa et al. 1997) or the production of prostanoids (Suzuki et al. 1991; Yamashita et al. 1999). In some experiments, the endothelium was removed using a small razor blade, as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992a,b;Yamakawa et al. 1997) and the lack of endothelial function was pharmacologically verified by the absence of a bradykinin-induced relaxation on the noradrenaline (3 μm)-induced contraction. Diclofenac (3 μm, to inhibit the synthesis of prostanoids) and 5 μm guanethidine (to prevent effects due to release of sympathetic transmitters) were present throughout the experiments. Diclofenac itself had no effect on the contractions induced by 128 mm K+ or STA2.

Recording of mechanical responses

A strip of omental artery was placed in a chamber with a capacity of 0.3 ml and superfused with Krebs solution at flow rate of about 2 ml min−1. Both ends of the preparation were fixed using fine silk threads and isometric tension was recorded using a strain-gauge transducer (AE801; SensoNor a.s., Horten, Norway). In some experiments, the muscle strip under study was mounted horizontally in an experimental recording chamber with a capacity of 0.2 ml and superfused with Krebs solution. In these experiments, each end of the preparation was fixed using pieces of Scotch double-sided adhesive tape (3M, St Paul, MN, USA) and isometric tension was recorded using a strain gauge transducer (U-Gauge; Shinko, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992a,b). A resting tension of 2–3 mg was applied so as to obtain a maximum contraction in response to 128 mm K+. Each preparation was allowed to equilibrate for 1–2 h before the start of the experiment. The length, width and thickness and the cross-sectional area of the preparation were measured with the aid of an inverted microscope at ×250 magnification using a calibrated scale. The transverse cross-sectional area was calculated assuming a rectangular cross-section, as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992a,b). Tension measurements were then expressed in kilonewtons per metre squared (kN m−2).

Concentration–response relationships for STA2 were obtained in endothelium-intact and -denuded strips from both groups of women, the STA2 (0.03–10 nm) being applied cumulatively from low to high concentration. The same relationship was also derived in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips, the strips being pre-treated with 0.3 mml-NNA for 45 min, which was then present throughout the experiment.

Endothelium-dependent relaxation was induced by an application of bradykinin (0.1 μm) or substance P (0.1 μm) during the contraction induced by STA2. Unless otherwise stated, the concentration of STA2 used was 3 nm in strips from normotensive pregnant women and 1 nm in strips from pre-eclamptic women; these concentrations were used to obtain contractions of approximately equal amplitude. For this set of experiments, the preparations were first contracted with STA2 and, after a steady-state contraction had been attained, one of the relaxants was then applied during the on-going STA2-induced contraction.

The effect of 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone (1-EBIO, a putative activator of intermediate Ca2+-activated K+ channels; Pedersen et al. 1999) was observed on the STA2-induced contraction in endothelium-denuded strips from both groups of women. STA2 was applied for 6 min at 45 min intervals until a reproducible contraction was obtained (normally, STA2 was given three or four times). Then the strips were pre-treated with 1-EBIO for 5 min and STA2 was applied for 6 min in the presence of 1-EBIO. This protocol was repeated with step-wise increases in the concentration of 1-EBIO from low to high.

The concentration–response relationship for SNP (0.1 nm-10 μm) was obtained by its cumulative application during the steady-state contraction induced by STA2 in endothelium-intact strips treated with l-NNA. For this set of experiments, the preparations were first treated with l-NNA (0.3 mm) for 45 min, then contracted with STA2 in the presence of l-NNA and finally, after a steady-state contraction had been attained, SNP was cumulatively applied during the on-going STA2-induced contraction.

To examine the concentration-dependent effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP (30–300 μm) on the STA2-induced contraction in endothelium-denuded strips from both groups of women, STA2 was applied for 6 min at 45 min intervals until a reproducible contraction was obtained. Then the strips were pre-treated with 8-pCPT-cGMP for 30 min and STA2 was applied for 6 min in the presence of 8-pCPT-cGMP. This protocol was repeated with step-wise increases in the concentration of 8-pCPT-cGMP from low to high.

Permeabilized smooth muscle strips

Endothelium-denuded muscle strips (0.50–0.75 mm wide, 0.03–0.05 mm thick, 0.3–0.4 mm long) obtained from both groups of women were permeabilized by an application for 30 min of β-escin (40 μm) in a relaxing solution containing 3 μm A23187 (pH 7.1), which was applied to avoid spurious effects due to Ca2+ release from intracellular storage sites in the skinned muscle, as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992b). To prevent deterioration of the Ca2+-induced contraction, 0.1 μm calmodulin was present throughout the experiment. The free Ca2+ concentration was calculated as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992b). All experiments were performed at room temperature (23–25°C). Various concentrations of Ca2+ were cumulatively applied, from low to high concentration. The amplitudes of the contractions induced by these concentrations of Ca2+ were normalized with respect to that induced by 10 μm Ca2+ in the same strip. To observe the concentration-dependent effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP on the Ca2+-induced contraction in β-escin-skinned strips, 0.5 μm Ca2+ was first applied to produce a contraction, then various concentrations of 8-pCPT-cGMP (30–300 μm) were cumulatively applied from low to high in the presence of 0.5 μm Ca2+.

Solutions

The ionic composition of the Krebs solution was as follows (mm): Na+, 137.4; K+, 5.9; Mg2+, 1.2; Ca2+, 2.6; HCO3−, 15.5; H2PO4−, 1.2; Cl−, 134; and glucose, 11.5. High K+ solution (128 mm) was prepared by replacing sodium chloride with potassium chloride isosmotically. All the solutions used in the present experiments contained diclofenac (3 μm, to prevent the production of cyclooxygenase products) and guanethidine (5 μm, to prevent effects due to release of sympathetic transmitters). The solutions were bubbled with 95 % oxygen and 5 % carbon dioxide and the pH was adjusted to 7.3–7.4 using NaOH and HCl.

The relaxing solution used for skinned-muscle experiments contained 4 mm ethyleneglycol-bis-(β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 87 mm potassium methanesulphonate (KMS), 5.1 mm Mg(MS)2, 5.2 mm ATP, 5 mm creatine phosphate, 20 mm 1,4-piperazinediethansulphonic acid (Pipes), 3 μm A23187 and 0.1 μm calmodulin. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.1 at 25°C using KOH and the ionic strength was standardized at 0.18 m by changing the amount of KMS added. The free Ca2+ concentration was calculated as described previously (Itoh et al. 1992b).

Drugs

The drugs used in the current experiments were as follows: sodium nitroprusside (SNP), β-escin, calmodulin and diclofenac sodium (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), l-NNA, bradykinin, substance P, charybdotoxin and apamin (Peptide Institute Inc, Osaka, Japan), 8-pCPT-cGMP (Biolog, Life Science Inst, Bremen, Germany), 1-EBIO (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), A23187 (free acid; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) and guanethidine (Tokyo Kasei, Tokyo, Japan). STA2 was kindly provided by Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Osaka, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The EC50 value (the concentration producing 50 % of the maximum effect) for the action of STA2 was obtained by fitting the data points for each strip by a non-linear least-squares method using software (Kaleida graph; Synergy Software, PA, USA) written for the Macintosh Computer (Apple Co. Ltd). The ED50 value (the dose producing 50 % of the maximum effect) for the relaxant action of SNP or 8-pCPT-cGMP on the STA2-induced contraction was also obtained by fitting the data points for each strip by a non-linear least-squares method. Since a steady-state contraction in response to Ca2+ was not clearly achieved before the addition of individual concentrations of 8-pCPT-cGMP in our experimental protocol (described above), the ED50 values derived for 8-pCPT-cGMP (see last section of Results) may be considered approximate. The Emax value represents the maximum response induced by a given agent. All results are expressed as the means ±s.e.m. The n values represent the number of subjects. A one-way or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (followed by Scheffé's F test for post hoc analysis) and Student's paired and unpaired t tests with an F test were used for statistical analysis. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Mechanical responses induced by high K+ and STA2

Application of high K+ solution (128 mm) produced a phasic, followed by a tonic increase in force in endothelium-intact strips from both normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women. In absolute terms, the maximum force induced by high K+ was not significantly different whether the strips were obtained from normotensive pregnant women or from pre-eclamptic women (Table 2). STA2 (10 nm) usually produced a monotonic contraction in endothelium-intact strips from both groups. However, on occasion STA2 produced a phasic, followed by an oscillatory contraction in strips from normotensive pregnant women (5 of 15 preparations) or pre-eclamptic women (3 of 9 preparations). When the maximum amplitude of contraction induced by high K+ solution was normalized as 1.0 in each preparation, the relative maximum contraction induced by 10 nm STA2 was 1.27 ± 0.08 (n = 15) in strips from normotensive pregnant women and 1.92 ± 0.12 (n = 9) in strips from pre-eclamptic women, the two values being significantly different from each other (P < 0.001).

Table 2. Mechanical properties of human omental arteries.

| Maximum tension | EC50 with intact endothelium | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128 mm K+(kN m−2) | STA2(kN m−2) | l-NNA + STA2(kN m−2) | Before l-NNA (nm) | After l-NNA(nm) | EC50 with endothelium removed(nm) | |

| Normotensive | 65.2 ±6.6 (15) | 80.9 ±5.4 (15) | 127.1 ±13.0 † (15) | 1.75 ±0.25 (10) | 1.87 ±0.29 (10) | 1.77 ±0.34 (5) |

| Preeclamptic | 53.4 ±9.2 (9) | 99.3 ±9.6 (9) | 111.2 ±18.1 (9) | 0.30 ±0.17* (9) | 0.32 ±0.15* (9) | 0.63 ±0.05* (9) |

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.Maximum force was obtained by an application of 10 nm STA2 in both groups of women. When used, l-NNA (0.3 mm) was given as a pretreatment for 45 min and was present throughout the experiment.

Significant at P < 0.05 vs. normotensive pregnant women.

P < 0.05 vs. before application of m-NNA.

l-NNA (0.3 mm, an inhibitor of NO synthase) did not modify the resting force. However, it significantly enhanced the contraction induced by 10 nm STA2 in strips from normotensive pregnant women (1.40 ± 0.14 times, n = 15,P = 0.01) but not in strips from pre-eclamptic women (1.12 ± 0.06 times, n = 9) (Table 2).

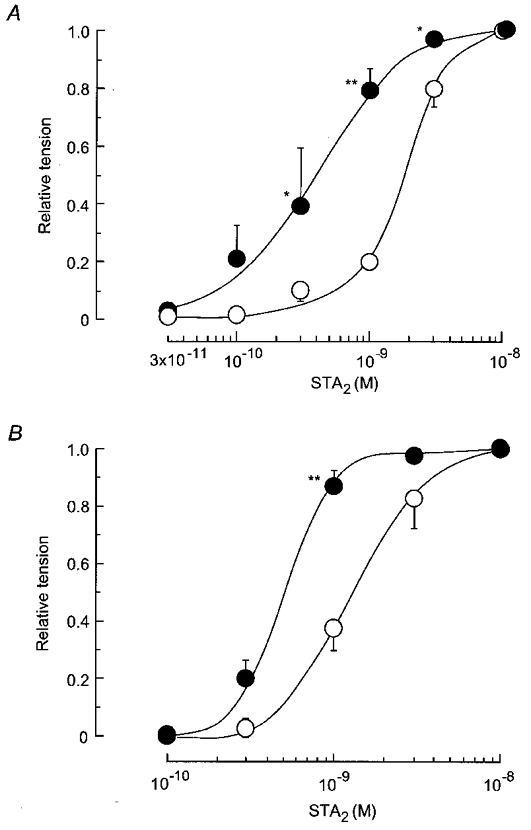

Effect of STA2 on contraction in endothelium-intact and -denuded strips

STA2 (0.03–10 nm) produced a concentration-dependent contraction in endothelium-intact strips from both normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women. The EC50 value was significantly smaller for pre-eclamptic women than for normotensive pregnant women (P = 0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). l-NNA (0.3 mm) did not modify the EC50 value for STA2 in strips from normotensive pregnant women (n = 10,P = 0.75) or in those from pre-eclamptic women (n = 9,P = 0.93,Table 2).

Figure 1. Concentration-dependent effects of STA2 in endothelium-intact and -denuded strips from normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women.

A, STA2 (0.003–10 nm) was applied cumulatively from low to high concentration in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 10) and pre-eclamptic women (•, n = 9).B, similar experiment on endothelium-denuded strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 5) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 6) women. The maximum amplitude of contraction induced by 10 nm STA2 was normalized as a relative tension of 1.0 for each strip. All tests were carried out in a solution containing 5 μm guanethidine and 3 μm diclofenac. Data are shown as means and s.e.m.*P < 0.05vs. corresponding normotensive value (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Scheffé's F test). **P < 0.01.

In endothelium-denuded strips, the EC50 value for the effect of STA2 was significantly smaller for pre-eclamptic women (n = 6) than for normotensive pregnant women (n = 5,P < 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 1B).

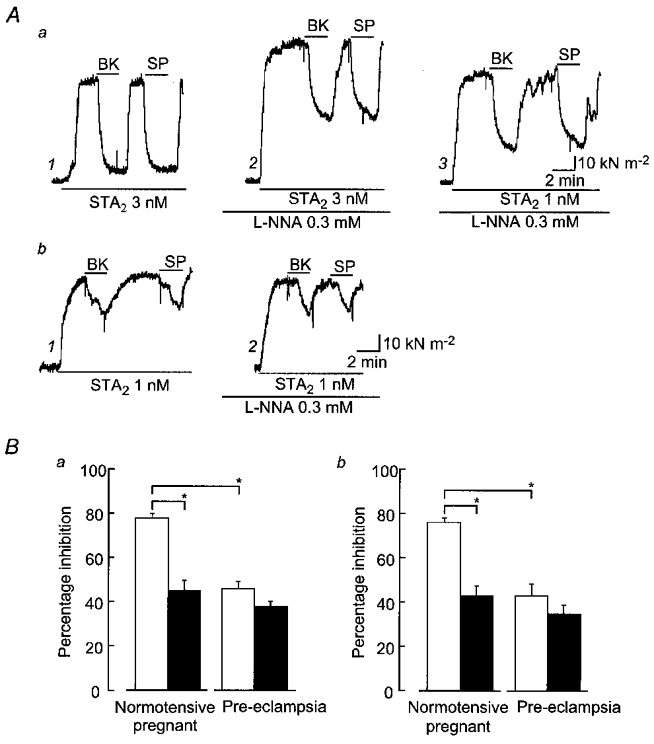

Effects of bradykinin and substance P on STA2 contraction

Bradykinin (0.1 μm) and substance P (0.1 μm) were each applied for 2 min during the steady-state contraction induced by STA2. An application of bradykinin or substance P produced a relaxation on the STA2-induced contraction in strips from both normotensive pregnant (Fig. 2Aa) and pre-eclamptic women (Fig. 2Ab). However, these effects were not seen in endothelium-denuded strips from either group (n = 4 in each case, data not shown). In strips from normotensive pregnant women, the relaxation induced by bradykinin was by 77.6 ± 2.0 % (n = 11) and that induced by substance P was by 75.6 ± 2.0 % (n = 11). In strips from pre-eclamptic women, the relaxation induced by either agent was significantly less than that seen in strips from normotensive pregnant women (relaxation 45.8 ± 3.2 %, n = 10, for bradykinin and 42.8 ± 5.6 %, n = 8, for substance P; P < 0.001 in each case) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Effects of bradykinin and substance P on STA2-induced contraction in endothelium-intact strips.

A, actual tracings of the effects of bradykinin (BK, 0.1 μm) and substance P (SP, 0.1 μm) on strips from normotensive pregnant (a) and pre-eclamptic (b) women. Bradykinin or substance P was applied for 2 min during the steady-state contraction induced by STA2 before (Aa1 and Ab1) and after (Aa2, Aa3 and Ab2) application of NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA, 0.3 mm). The concentrations of STA2 used are indicated. B, summary of the effects of bradykinin (Ba) and substance P (Bb) in the absence (□) or presence (▪) of l-NNA. Data are shown as means and s.e.m.*P < 0.05 (Student's paired or unpaired t test with F test).

l-NNA (0.3 mm) enhanced the contraction induced by 3 nm STA2 (Table 2) and significantly attenuated the relaxations induced by bradykinin (relaxation 45.1 ± 4.5 %, n = 11) and substance P (relaxation 43.1 ± 4.0 %, n = 11) in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant women (Fig. 2Aa and B). This l-NNA-induced attenuation of the relaxations induced by bradykinin and substance P was also observed when 1 nm STA2 was used to induce the test contraction (so as to adjust the size of the contraction to the match that induced by 3 nm STA2 before the application of l-NNA; Fig. 2Aa, traces 1–3). In the presence of l-NNA with 1 nm STA2, the relaxation induced by bradykinin was by 50.5 ± 6.6 % (n = 6) and that induced by substance P was by 47.6 ± 9.5 % (n = 6); these values were significantly smaller than those seen in the presence of 3 nm STA2 before the application of l-NNA in the same strips (P < 0.01). In contrast, in strips from pre-eclamptic women, l-NNA did not modify the relaxation induced by bradykinin (relaxation 37.5 ± 4.0 %, n = 10,P = 0.11) or substance P (relaxation 34.8 ± 3.9 %, n = 8,P = 0.26) (Fig. 2Ab and B).

In the presence of 0.3 mml-NNA, application of charybdotoxin (0.1 μm) plus apamin (0.1 μm) enhanced the contraction induced by STA2 (1.38 ± 0.05 times, n = 5,P < 0.001) and greatly attenuated the relaxation induced by 0.1 μm bradykinin (relaxation 13.4 ± 5.0 %, n = 5,P < 0.001) in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant women (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained in endothelium-intact strips from pre-eclamptic women, in which the relaxation induced by 0.1 μm bradykinin was by 17.0 ± 4.6 % in the presence of charybdotoxin plus apamin (n = 3,P < 0.05,Fig. 3B). In contrast, in the presence of 0.3 mml-NNA, BaCl2 (30 μm) had no significant effect on the relaxation induced by 0.1 μm bradykinin in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant (relaxation 40.0 ± 3.7 %, n = 6,P = 0.44) or pre-eclamptic women (relaxation 36.1 ± 5.2 %, n = 4,P = 0.84).

Figure 3. Effect of charybdotoxin plus apamin on the relaxation induced by bradykinin in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips from normotensive pregnant (A) and pre-eclamptic women (B).

l-NNA (0.3 mm) was applied for 45 min and STA2 was then applied in the presence of l-NNA. Bradykinin (BK, 0.1 μm) was subsequently applied for 2 min during the steady-state contraction induced by STA2. After a 25 min interval, STA2 was again applied and charybdotoxin (ChTX, 0.1 μm) plus apamin (0.1 μm) was subsequently applied during the STA2-induced steady-state contraction. BK (0.1 μm) was finally applied in the presence of ChTX, apamin and STA2.

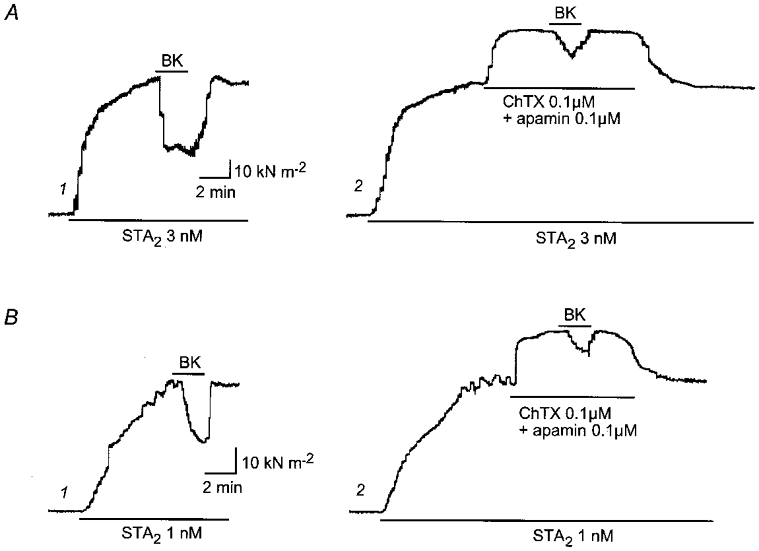

Effect of 1-EBIO on STA2 contraction

In endothelium-denuded strips, 1-EBIO (100–500 μm), a putative activator of intermediate KCa channels (Pedersen et al. 1999), did not modify the resting force. However, it did attenuate the contraction induced by STA2 in a concentration-dependent manner in endothelium-denuded strips from both groups of women. The values obtained for the sensitivity of the response to 1-EBIO (ED50 = 50.0 ± 24.5 μm, n = 4) and its maximum effect (Emax = 80.0 ± 2.8 %, n = 4) in strips from pre-eclamptic women did not differ significantly from those obtained in strips from normotensive pregnant women (ED50 = 55.7 ± 34.1 μm, n = 8,P = 0.91 and Emax = 77.6 ± 2.5 %, P = 0.53) (Fig. 4). These ED50 values for 1-EBIO are quite similar to the value of 74 μm reported for a cloned human intermediate-conductance KCa channel by Jensen et al. (1998).

Figure 4. Effect of 1-EBIO on contraction induced by STA2 in endothelium-denuded strips.

A, actual tracings of the concentration-dependent effect of 1-EBIO on the contraction induced by 1 nm STA2 in an endothelium-denuded strip from a pre-eclamptic woman. STA2 was applied for 4 min at 25 min intervals. After the control STA2 response had been recorded, 1-EBIO was pre-treated for 5 min and STA2 was then applied in the presence of 1-EBIO. 1-EBIO was cumulatively applied from low to high concentration. All the tests were carried out using a single strip from a pre-eclamptic woman. B, summary of the concentration-dependent effect of 1-EBIO (10–500 μm) in endothelium-denuded strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 8) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 4) women. Data are shown as means and s.e.m.

Effect of SNP and 8-pCPT-cGMP on STA2 contraction

SNP (1 nm-10 μm) produced a concentration-dependent relaxation on the steady-state contraction induced by STA2 in strips from both normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women. At any given concentration (0.001–10 μm), the magnitude of the SNP-induced relaxation was significantly smaller for pre-eclamptic women than for normotensive pregnant women (Fig. 5A). However, the ED50 values for SNP were not significantly different between strips from normotensive pregnant women (0.12 ± 0.09 μm, n = 7) and those from pre-eclamptic women (0.13 ± 0.08 μm, n = 6,P = 0.92) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Concentration-dependent effect of SNP on contraction induced by STA2 in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips.

A, actual tracings of the effect of SNP (0.1 nm-10 μm) on the contraction induced by STA2 in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant (Aa) and pre-eclamptic (Ab) women. Following an application of 0.3 mml-NNA for 45 min, SNP was applied cumulatively from low to high concentration during the steady-state contraction induced by STA2 in the presence of l-NNA. B, summary of the effect of SNP on the STA2-induced contraction in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 7) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 6) women. Data are shown as means and s.e.m.*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01vs. corresponding normotensive value (one-way and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Scheffé's F test).

In the next set of experiments, 8-pCPT-cGMP (30–300 μm) was given as pre-treatment for 30 min after the control STA2-induced contraction had been recorded in endothelium-denuded strips. This agent concentration-dependently attenuated the STA2-induced contraction in strips from both groups of women (Fig. 6). The values obtained for the sensitivity of the response (ED50 = 21.3 ± 1.4 μm, n = 5) and its maximum value (Emax = 73.4 ± 4.4 % at 100 μm 8-pCPT-cGMP, n = 5) in strips from normotensive pregnant women differed significantly from those obtained in strips from pre-eclamptic women (ED50 = 91.3 ± 16.6 μm, P < 0.001 and Emax = 64.2 ± 4.8 % at 300 μm 8-pCPT-cGMP, P = 0.03,n = 6) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP on contraction induced by STA2 in endothelium-denuded strips.

A, actual tracings of the effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP (30–300 μm) on contractions induced by STA2 in strips from normotensive pregnant (Aa) and pre-eclamptic (Ab) women. STA2 was applied for 5 min at 45 min intervals. After the control STA2 response had been recorded in each strip (8-pCPT-cGMP (–)), 8-pCPT-cGMP was pre-treated for 30 min and STA2 was then applied in the presence of 8-pCPT-cGMP. 8-pCPT-cGMP was cumulatively applied from low to high concentration. B, summary of the effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP in strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 5) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 6) women. Data are shown as means and s.e.m. **P < 0.01vs. corresponding normotensive value (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Scheffé's F test).

Effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP on Ca2+-induced contraction in β-escin-skinned smooth muscle

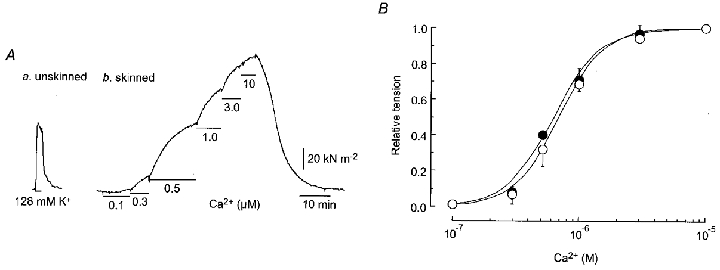

In β-escin-treated skinned muscle from normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women, the minimum concentration of Ca2+ that produced a contraction was 0.1 μm and the maximum contraction was obtained at 10 μm (Fig. 7A). The ED50 value obtained for pre-eclamptic women (0.64 ± 0.04 μm, n = 10) did not differ significantly from that obtained for normotensive pregnant women (0.70 ± 0.09 μm, n = 12,P = 0.40) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. [Ca2+]–tension relationship in β-escin-treated skinned smooth muscle strips from normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic women.

Aa, high K+ (128 mm) solution was applied to an endothelium-denuded, unskinned muscle strip from a pre-eclamptic woman. Ab, after application of β-escin (40 μm) for 30 min in a relaxing solution, Ca2+ (0.1–10 μm) was cumulatively applied from low to high concentration. B,[Ca2+]-tension relationship in β-escin-skinned strips from normotensive pregnant (○, n = 12) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 10) women. Contractions are normalized with respect to the contraction induced by 10 μm Ca2+ in the same strip. Data are presented as means and s.e.m.

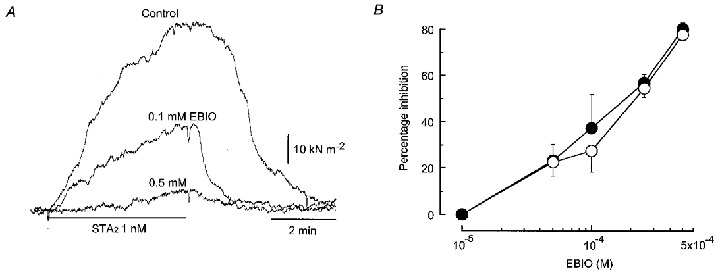

When 8-pCPT-cGMP (1–30 μm) was applied on the steady-state contraction induced by 0.5 μm Ca2+, this agent concentration-dependently attenuated the Ca2+-induced contraction in skinned strips obtained from both groups of women. At any given concentration from within the range 1–100 μm, the relaxation induced by 8-pCPT-cGMP was significantly smaller for strips from pre-eclamptic women than for those from normotensive pregnant women (Fig. 8). The ED50 value for the response to 8-pCPT-cGMPS in strips from pre-eclamptic women (2.2 ± 1.4 μm, n = 8) was significantly larger than that obtained for normotensive pregnant women (0.81 ± 0.17 μm, n = 11,P < 0.0001) (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Effect of 8-pCPT-cGMP on Ca2+-induced contraction in β-escin-skinned strips.

A, actual tracings of the concentration-dependent effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP on the contraction induced by 0.5 μm Ca2+ in skinned strips from normotensive pregnant (Aa) and pre-eclamptic (Ab) women. After a steady-state contraction had been obtained to 0.5 μm Ca2+, 8-pCPT-cGMP was cumulatively applied from low to high concentration in the presence of 0.5 μm Ca2+. B, summary of the effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP on the contractions induced by 0.5 μm Ca2+ in β-escin-skinned strips from normotensive (○, n = 11) and pre-eclamptic (•, n = 8) women. Data are shown as means and s.e.m. **P < 0.01vs. corresponding normotensive value (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Scheffé's F test).

DISCUSSION

Increase in the contractile response to a thromboxane A2 mimetic in pre-eclampsia

It has been found that the contractile responses to both angiotensin II (Gant et al. 1973; Aalkjaer et al. 1985) and vasopressin (Pascoal et al. 1998) are up-regulated in omental resistance arteries in patients with pre-eclampsia (by comparison with the situation in normotensive pregnant women). In the present experiments, the concentration- response relationship for the contraction induced by STA2 (a stable analogue of thromboxane A2) was significantly shifted to the left in endothelium-intact omental resistance arteries from pre-eclamptic women (by comparison with that for normotensive pregnant women). Neither an application of l-NNA (an inhibitor of NO synthase) nor removal of the endothelium modified this difference in STA2 sensitivity. Furthermore, the ratio between the contractions induced by 10 nm STA2 and high [K+] (128 mm) before the application of l-NNA was significantly higher for the pre-eclamptic group than for the normotensive pregnant group, although the absolute tension induced by 10 nm STA2 in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips was similar for both groups. These results suggest that, like the responses to angiotensin II and vasopressin, the mechanisms underlying the contraction mediated by thromboxane A2 (such as Ca2+ mobilization and Ca2+ sensitization) may be up-regulated in the smooth muscle of omental resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia.

Decrease in the role of endothelium-derived NO in pre-eclampsia

In the present experiments, l-NNA enhanced the STA2-induced contraction in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant women but not in those from pre-eclamptic women. Furthermore, l-NNA attenuated the endothelium-dependent relaxations induced by bradykinin and substance P only in strips from normotensive pregnant women. An attenuation by l-NNA was also apparent when contraction was induced by a lower concentration of STA2 (1 nm) so as to adjust its amplitude to the same level as that seen before the application of l-NNA. These results suggest that in human omental resistance arteries, the role of NO (which is released from the endothelium spontaneously or by agonists) is reduced in pre-eclampsia.

There are at least three possible explanations for this reduced endothelium-dependent, NO-mediated response in resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia: (i) a reduction in the amount of NO released from the endothelium or an acceleration in the breakdown of NO, (ii) a reduction in the synthesis of cyclic GMP (a second messenger for NO-mediated vasodilatation) induced by endothelium-derived NO (via a reduced amount or reduced activity of soluble guanylyl cyclase and/or an increase in the activities of phosphodiesterases), and (iii) a reduction in the relaxing activity of cyclic GMP in smooth muscle cells. It has recently been found that, in arteries from the subcutaneous fat, the endothelial NO synthase expression is increased in patients with pre-eclampsia (by comparison with normotensive pregnant women) (Roggensack et al. 1999). Furthermore, both the activity and the expression of NO synthase are greater in cultured endothelial cells when the cells are exposed to plasma from pre-eclamptic women than when they are exposed to that from women with uncomplicated pregnancies (Baker et al. 1995; Davidge et al. 1995). These results support the notion that the production of NO by endothelial cells may be greater in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia than in women with an uncomplicated pregnancy. In the present experiments, we found that the relaxation induced by SNP on the STA2-induced contraction was significantly attenuated in endothelium-intact, l-NNA-treated strips from pre-eclamptic women. Furthermore, to our surprise, the relaxation induced by 8-pCPT-cGMP (a membrane permeable, phosphodiesterase-resistant cyclic GMP analogue) on the STA2-induced contraction was also significantly attenuated in endothelium-denuded strips from pre-eclamptic women (by comparison with those from normotensive pregnant women). This reduced responsiveness to 8-pCPT-cGMP was confirmed when the test response was the Ca2+-induced contraction in β-escin skinned muscle (in which the intracellular ionic concentrations and the pH were both closely matched). It was recently noted that NO-mediated vascular relaxation was significantly attenuated without an alteration in cyclic AMP-mediated responses in the aorta of endothelial NO synthase transgenic mice (Ohashi et al. 1998), suggesting that if the release of NO from the endothelium were chronically increased in the resistance arteries of patients with pre-eclampsia, a downregulation of endothelium-derived, NO-mediated relaxation could be expected. Taken together, these results suggest that in human omental resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia, a reduced release of NO from the endothelium is probably not the cause of the abnormality in the role played by endothelium-derived NO. Instead, this phenomenon is likely to result, at least in part, from a reduction in the cyclic GMP-mediated response in the smooth muscle cell. The precise mechanisms remain to be clarified in future work.

The present results are not consistent with previous findings that suggest that the relaxation response to SNP is not significantly modified in endothelium-intact strips of resistance arteries from pre-eclamptic women (by comparison with those from normotensive pregnant women) (McCarthy et al. 1993; Knock & Poston, 1996; Pascoal et al. 1998). This may, in part, result from the use of different vasospasmogenic agents (STA2 in the present study vs. noradrenaline or vasopressin in the previous studies).

Unchanged role of endothelium-derived NO- and prostanoid-independent factor in pre-eclampsia

It is known that bradykinin and substance P each produce an endothelium-dependent relaxation though the release not only of NO and prostanoids but also of an endothelium-derived, membrane hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF), the action of which can be inhibited by a combined application of charybdotoxin (a blocker of intermediate- and large- conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels) plus apamin (a blocker of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels) (Garland et al. 1995; Marchenko & Sage, 1996; Petersson et al. 1997). In the present experiments, conducted in the presence of the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor diclofenac, the relaxations induced by bradykinin and substance P on the STA2-induced contraction were attenuated by l-NNA in endothelium-intact strips from normotensive pregnant women, with about one-half of the relaxation remaining in each case. In contrast, l-NNA had no such effect in strips from pre-eclamptic women. Furthermore, the bradykinin-induced relaxations seen in strips from both groups of women in the presence of l-NNA plus diclofenac were greatly reduced by the application of charybdotoxin plus apamin, but not of Ba2+. This implies that bradykinin activates Ca2+-activated K+ channels (possibly by mobilizing Ca2+ from the intracellular stores) but not inwardly rectifying K+ channels (which would have been largely prevented by the 30 μm Ba2+ we used, Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Moreover, the relaxation response to 1-EBIO (a putative activator of intermediate Ca2+-activated K+ channels, Pedersen et al. 1999) in endothelium-denuded strips was not different between normotensive pregnant and pre-eclamptic groups. These results suggest that in human omental resistance arteries, the role of the endothelium-derived-NO- and prostanoid-independent factor (possibly EDHF) may be preserved in pre-eclampsia.

In conclusion, our results suggest that in human omental resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia, the contractile response to thromboxane A2 in smooth muscle cells is up-regulated and that the role of endothelium-derived NO, but not of NO- and prostanoid-independent factor, is reduced. It is suggested that the reduced responsiveness to endothelium-derived NO seen in resistance arteries in pre-eclampsia is likely to result, at least in part, from a reduction in the cyclic GMP-mediated response in smooth muscle cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr R. J. Timms for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Drs I. Murakami, T. Ohshima, K. Yamaguchi, K. Kojima and T. Yamamoto (the staff of the delivery suites at Nagoya City University Hospital), K. Teshigawara (Teshigawara Clinic) and T. Wada (Kainan Hospital) for their co-operation in this study. This work was partly supported by a Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

References

- Aalkjaer C, Danielsen H, Johannesen P, Pedersen EB, Rasmussen A, Mulvany MJ. Abnormal vascular function and morphology in pre-eclampsia: a study of isolated resistance vessels. Clinical Science. 1985;69:477–482. doi: 10.1042/cs0690477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PN, Davidge ST, Roberts JM. Plasma from women with pre-eclampsia increases endothelial cell nitric oxide production. Hypertension. 1995;26:244–248. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartha JL, Comino-Delgado R, Bedoya FJ, Barahona M, Lubian D, Garcia-Benasach F. Maternal serum nitric oxide levels associated with biochemical and clinical parameters in hypertension in pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1999;82:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, Pober JS, Wick TM, Konkle BA, Schwartz BS, Barnathan ES, McCrae KR, Hug BA, Schmidt AM, Stern DM. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham FG. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. In: Cunningham FG, Macdonald PC, Leveno KJ, Gant NF, Gilstrap LC III, editors. Williams Obstetrics. NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1998. pp. 693–744. [Google Scholar]

- Davidge ST, Baker PN, Roberts JM. NOS expression is increased in endothelial cells exposed to plasma from women with preeclampsia. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H1106–1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeigbe AB, Ezimokhai M. Vascular smooth muscle responses in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1988;9:455–457. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feelisch M, Noack EA. Correlation between nitric oxide formation during degradation of organic nitrates and activation of guanylate cyclase. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1987;139:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant NF, Daley GL, Chand S, Whalley PJ, Macdonald PC. A study of angiotensin II pressor response throughout primigravid pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1973;52:2682–2689. doi: 10.1172/JCI107462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland CJ, Plane F, Kemp BK, Cocks TM. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization: a role in the control of vascular tone. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Kajikuri J, Kuriyama H. Characteristic features of noradrenaline-induced Ca2+ mobilization and tension in arterial smooth muscle of the rabbit. The Journal of Physiology. 1992a;457:297–314. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Seki N, Suzuki S, Ito S, Kajikuri J, Kuriyama H. Membrane hyperpolarization inhibits agonist-induced synthesis of inositol 1,4, 5-trisphosphate in rabbit mesenteric artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1992b;451:307–328. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen BS, Strøbæk D, Christophersen P, Jorgensen TD, Hansen C, Silahtaroglu A, Olesen SP, Ahring PK. Characterization of the cloned human intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C848–856. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmura Y, Itoh T, Kuriyama H. Mechanisms of vasoconstriction induced by 9,11-epithio-11,12-methano-thromboxane A2 in the rabbit coronary artery. Circulation Research. 1987;60:402–409. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knock GA, Poston L. Bradykinin-mediated relaxation of isolated maternal resistance arteries in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:1668–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama H, Kitamura K, Itoh T, Inoue R. Physiological features of visceral smooth muscle cells, with special reference to receptors and ion channels. Physiological Reviews. 1998;78:811–920. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenfant C, Gifford RW, Jr, Zuspan FP. National high blood pressure education program working group report on high blood pressure in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;163:1691–1712. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90653-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy AL, Woolfson RG, Raju SK, Poston L. Abnormal endothelial cell function of resistance arteries from women with preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;168:1323–1330. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko SM, Sage SO. Calcium-activated potassium channels in the endothelium of intact rat aorta. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:53–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacological Reviews. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiye E, Nakao K, Itoh T, Kuriyama H. Factors inducing endothelium-dependent relaxation in the guinea-pig basilar artery as estimated from the actions of haemoglobin. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;96:645–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris LA, Higgins JR, Darling MR, Walshe JJ, Bonnar J. Nitric oxide in the uteroplacental, fetoplacental, and peripheral circulations in preeclampsia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;93:958–963. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi Y, Kawashima S, Hirata KI, Yamashita T, Ishida T, Inoue N, Sakoda T, Kurihara H, Yazaki Y, Yokoyama M. Hypotension and reduced nitric oxide-elicited vasorelaxation in transgenic mice overexpressing endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102:2061–2071. doi: 10.1172/JCI4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal IF, Lindheimer MD, Nalbantian-Brandt C, Umans JG. Preeclampsia selectively impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation and leads to oscillatory activity in small omental arteries. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:464–470. doi: 10.1172/JCI557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen KA, Schroder RL, Skaaning-Jensen B, Strobaek D, Olesen SP, Christophersen P. Activation of the human intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel by 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone is strongly Ca2+-dependent. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1420:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson J, Zygmunt PM, Hogestatt ED. Characterization of the potassium channels involved in EDHF-mediated relaxation in cerebral arteries. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:1344–1350. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston L, McCarthy AL, Ritter JM. Control of vascular resistance in the maternal and feto-placental arterial beds. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1995;65:215–239. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00064-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranta V, Viinikka L, Halmesmäki E, Ylikorkala O. Nitric oxide production with preeclampsia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;93:442–445. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;161:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson SC, Hunter S, Boys RJ, Dunlop W. Serial study of factors influencing changes in cardiac output during human pregnancy. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:H1060–1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggensack AM, Zhang Y, Davidge ST. Evidence for peroxynitrite formation in the vasculature of women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 1999;33:83–89. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek SM, Magness RR, Conrad KP. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:R441–463. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Kajikuri J, Suzuki A, Itoh T. Effects of endothelin-1 on endothelial cells in the porcine coronary artery. Circulation Research. 1991;69:1361–1368. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance P, Collier J, Moncada S. Effects of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on peripheral arteriolar tone in man. Lancet. 1989;28:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa N, Ohhashi M, Waga S, Itoh T. Role of endothelium in regulation of smooth muscle membrane potential and tone in the rabbit middle cerebral artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;121:1315–1322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Kajikuri J, Ohashi M, Kanmura Y, Itoh T. Inhibitory effects of propofol on acetylcholine-induced, endothelium-dependent relaxation and prostacyclin synthesis in rabbit mesenteric resistance arteries. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1080–1089. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199910000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]