Abstract

We have investigated the characteristics of the α9 acetylcholine receptor (α9AChR) expressed in hair cell precursors in an immortalized cell line UB/OC-2 developed from the organ of Corti of the transgenic H-2Kb-tsA58 mouse (the Immortomouse) using both calcium imaging and whole-cell recording.

Ratiometric measurements of fura-2 fluorescence revealed an increase of intracellular calcium concentration in cells when challenged with 10 μM ACh. The calcium increase was seen in 66 % of the cells grown at 39 °C in differentiated conditions. A smaller fraction (34 %) of cells grown at 33 °C in proliferative conditions responded.

Caffeine (10 mM) elevated cell calcium. In the absence of caffeine, the majority of imaged cells responded only once to ACh. A small proportion (< 2 % of the total) responded with an increase in intracellular calcium to multiple ACh presentations. Pretreatment with caffeine inhibited all calcium responses to ACh.

In whole-cell tight-seal recordings 10 μM ACh activated an inward, non-selective cation current. The reversal potential of the ACh-activated inward current was dependent on the extracellular calcium concentration with an estimated PCa/PNa of 80 for the α9 receptor at physiological calcium levels.

The data indicate that ACh activates a calcium-permeable channel α9AChR in UB/OC-2 cells and that the channel has a significantly higher calcium permeability than other AChRs. The results indicate that the α9AChR may be able to elevate intracellular calcium levels in hair cells both directly and via store release.

Hair cells of the vertebrate cochlea are supplied with an orderly efferent innervation that terminates either on the outer hair cells or on the afferent terminals of the inner hair cells (Guinan, 1996). The pathway terminating on outer hair cells uses acetylcholine as the transmitter and efferent activation leads to hyperpolarization of the hair cell. These apparent inhibitory effects of ACh on outer hair cells have been ascribed to the activation of a potassium-selective current that causes a small hyperpolarization of the cell (Housley & Ashmore, 1991; Evans, 1996). The potassium current activates after intracellular calcium rises, either by entering through the activated ACh receptor or, it has been suggested, by a triggered intracellular mechanism (Doi & Ohmori, 1993; Blanchet et al. 1996; Nenov et al. 1996). The characteristic pharmacology of this response suggests this ACh receptor to be a novel member of the ‘nicotinic’ ACh receptor family (Housley & Ashmore, 1991; Plinkert et al. 1991; Elgoyhen et al. 1994).

The receptor responsible, the so-called α9 subunit of the nicotinic ACh receptor, (α9AChR) has been cloned from the rat olfactory epithelium and has been shown to be present in cochlear hair cells of the rat (Elgoyhen et al. 1994). Properties of α9AChR have also been reported in an oocyte expression system (Katz et al. 2000) which reveal that it has a high calcium permeability. Although direct measurement of the properties of the receptor in native hair cells has proved elusive, the α9AChR has recently been shown to be functionally expressed in the cell line UB/OC-2 derived from the organ of Corti of the Immortomouse (Rivolta et al. 1998). This embryonic immortal cell line can be grown as proliferating cultures (grown at 33°C, including γ-interferon to initiate the promoter) or differentiating cultures (grown at 39°C in the absence of γ-interferon) due to the temperature sensitivity of the immortalizing gene. Populations of hair cell precursors can therefore be grown in large numbers. This cell line expresses a number of molecular markers typical of hair cells. These markers include Brn3.1 and myosin 7 as well as α9. The electrophysiology of the α9AChR can be studied since at this stage of development it is not obscured by the presence of other currents (Jagger et al. 1999) and some of its properties can be investigated directly.

We describe below both calcium imaging experiments and electrophysiological recordings which show that α9 in UB/OC-2 has a higher calcium permeability than any of the other nicotinic receptors and that this calcium entry may be further augmented by induced calcium release from intracellular stores. Such features expressed in mature cells may account for some observed effects of the cholinergic efferent system described in cochlear hair cells. A preliminary report of these results has been published (Jagger et al. 1998).

METHODS

Cell culture and tissue preparation

Cells from the established cochlear cell line UB/OC-2 (see Rivolta et al. 1998 for a detailed description of establishment and cell culture protocols) were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle's salts (Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco). For expression of the immortalizing gene proliferating cultures were grown at 33°C with 50 U ml−1γ-interferon (Gibco). Differentiating cultures were grown at 39°C for 8–10 days without γ-interferon. Cells were grown on 35 mm diameter plastic dishes (Becton Dickinson) for use in electrophysiological recording, and on Petriperm dishes (Heraeus) in imaging experiments. Before experiments, cells were washed with Hepes-buffered solution (HBS, see below). During experiments cells were superfused by HBS at a rate of 200–500 μl min−1. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–25°C) and were completed within 2 h of the cells being removed from the incubator.

Cells will be described as 33°C or 39°C cells depending on growth conditions.

Solutions

The external solution (HBS) contained (mM): NaCl, 142; KCl, 4; MgCl2, 2; CaCl2, 2; Hepes, 10; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH and to 300 mosmol l−1 with D-glucose. Acetylcholine chloride (ACh) was made as a stock solution in H2O and added to the HBS as required. When the ACh solution had a [Ca2+] of lower than 2 mM, Mg2+ was adjusted to minimize errors due to surface charge screening effects. In 5 mM Ca2+ solution Mg2+ was reduced to 1 mM, and in this case, the estimated error due to any change in surface charge was less than 3 mV (Baldridge et al. 1999). Solutions were applied by pressure from fused micropipettes forming a multi-barrelled array or, in imaging experiments, by single perfusion pipettes with large internal diameter (5 μm) to ensure large areas of ACh application. In whole-cell experiments patch pipettes contained (mM): KCl, 142; MgCl2, 2; Na2ATP, 2; EGTA, 0.5; Hepes, 10; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH and to 300 mosmol l−1 with D-glucose.

Calcium imaging

For imaging, cells were grown in 35 mm diameter Petriperm dishes because the thin gas-permeable membrane forming the floor of the dish allows good imaging optics. Cells were loaded with the acetoxymethyl ester form of the calcium indicator fura-2 (fura-2 AM) at 3 μM for 30 min either at 33°C or at 39°C. Cells were placed on the stage of an inverted microscope and viewed with a ×20 0.75 NA FLUAR objective (Zeiss). The chamber was continuously perfused at 0.2 ml min−1 with MEM except when imaging runs started as it was found that the solution pulsation affected the vertical position of the cells. Acetylcholine was applied at a low rate from a 5 μm diameter patch pipette at the edge of the field of view and data acquired for subsequent off-line analysis. Ratiometric images were acquired with 340 nm and 380 nm excitation (emission filter 510 nm) using a Hamamatsu C-4880 camera and stored on disk for subsequent analysis using Lucida imaging software (Kinetic Imaging, UK). From in vitro calibration, the maximum:minimum fluorescence ratio was Rmax/Rmin = 1.78 and the calibration bars in Fig. 2 corresponded to a rise of approximately 200 nM, from a typical baseline calcium of 130 nM. In separate confocal imaging experiments, the cells were found to have large regions of intracellular membrane when labelled with the endocytosis marker dye FM1-43 (data not shown) and since this can produce calibration artifacts when AM dyes are used, only ratios are given in the imaged cell records. No correction for photobleaching was applied to the small signals as only broad features of the responses were investigated.

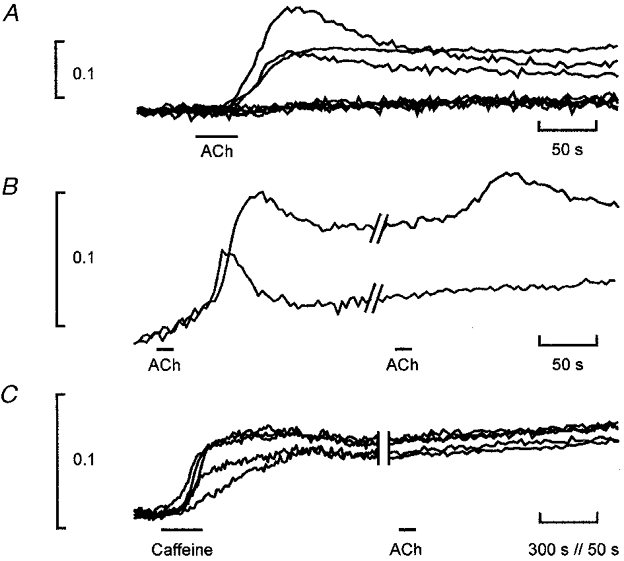

Figure 2. Calcium elevation in UB/OC-2 cells.

A, F340/F380 from individual whole-cell outlines in response to slow application of 10 μM ACh as in Fig. 1. Cells either showed no response at all or a discrete calcium increase that washed out slowly. The baseline ratios of the 8 cells have been set equal for comparison. F340/F380 ratio shown as ordinate scale. The onset time of the response was limited by the drug diffusion from the application pipette, which was placed to minimize movement artifacts. B, response of 2 cells to repeated application of ACh. Both cells received the drug. Some differential bleaching of the dye at the two excitation wavelengths is responsible for upward baseline drift. C, response of cells in a single field superfused with 10 mM caffeine, all cells responding; ACh elicited no subsequent response in any cells in the sample: the expected number of cells responding would have been 3. Note that the display uses a different time scale at the beginning and end of the trace.

Electrophysiology

For electrophysiological recordings, plastic dishes were mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Leica DM-IL, Germany) and cells observed with ×640 magnification. Patch pipettes were pulled on a two-stage vertical puller (PIP5, HEKA, Germany) from 1.2 mm o.d. borosilicate glass capillaries (Clark Electromedical Instruments, UK). Recordings were made using an EPC/7 patch clamp amplifier (List Medical, Germany). The pipette resistance was typically 2–4 MΩ when measured in the bath solution. Series resistance ranged from 5 to 15 MΩ and was electronically compensated by 50–70 %. Current and voltage were sampled at 10 kHz using a laboratory interface (CED 1401, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK). Statistical data results are expressed as means ±s.d.

RESULTS

Calcium imaging

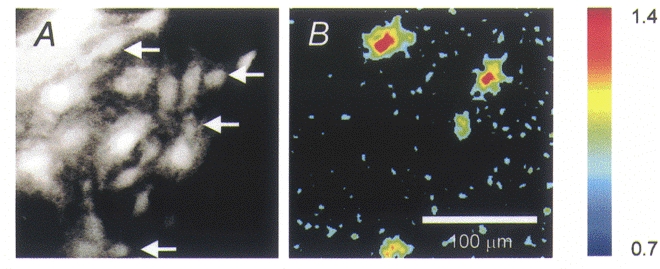

UB/OC-2 cells were used at the stage when they formed a near-confluent population of cells. To investigate effects on internal calcium levels, ACh was applied to a large population of cells loaded with the calcium-sensitive indicator fura-2. Both 33°C and 39°C cells responded to ACh with comparable time courses once differences in application rates were accounted for. Within a field of typically 10–15 cells, application of 10 μM ACh produced either a rise in calcium in individual cells or almost no response at all (Fig. 1). This suggests that calcium permeability in these cells was discrete. Both rise and fall times of the response were compatible with the diffusion-limited drug delivery that was applied deliberately slowly to avoid movement artifacts (see Methods).

Figure 1. Calcium elevation in UB/OC-2 cells monitored by fura-2 imaging.

A, image of a field of cells, viewed by 510 nm fluorescence with 380 nm excitation. B, elevation of F340/F380 ratio (i.e. fluorescence intensity with 340 nm excitation/fluorescence intensity with 380 nm excitation) after 30 s of slow application of 10 μM ACh. The change is displayed relative to the control ratios before drug application. Only 4 cells (arrowed in A) of the field show an elevation relative to background. Note that the cells are not adjacent. The fluorescence ratio is pseudocoloured, with elevation represented by ‘hotter’ colours (colour bar to right, with ratio indicated). Raw images were acquired at 512 × 512 pixels and 3 × 3 point averaging employed. Scale bar applies to both panels.

In the response pattern shown in Fig. 2A, 3/8 (or 38 %) of the cells grown at 33°C responded. A larger proportion (66 %, n = 75 responding cells) of cells grown at 39°C responded to 10 μM ACh. This difference is reflected in the different expression levels detected by RT-PCR in UB/OC-2 cells (Rivolta et al. 1998). All subsequent imaging experiments are described for 39°C cells where the expression levels of α9AChR are highest.

Although the calcium rise was graded with the ACh concentrations between 5 and 20 μM (data not shown), cells rarely responded to a second or third application of ACh which were delivered with an interval of 300–500 s allowing calcium levels to return to baseline. In a total population of 189 cells 56 % responded to ACh; of these 3.8 % (4/105 cells) responded to a second and 2.8 % (3/105) to a third trial (Fig. 2B).

All cells responded to bath application of 10 mM caffeine. The response developed over minutes (Fig. 2C). Calcium levels thereafter only slowly returned to pre-caffeine baseline (typically over times greater than 1200 s). In the experiment shown, cells did not subsequently respond to ACh. In a total population of n = 37 cells, pre-treatment with caffeine eliminated the response to ACh. On the basis of the above data, 37 × 0.56 = 20 of these cells should have responded to ACh. The converse experiment (not shown), where ACh preceded caffeine by an interval greater than 500 s, showed that all cells responding to ACh also responded to caffeine (n = 16 cells).

Ionic currents

The primary event leading to a cellular calcium rise was activation of the α9AChR. Figure 3 shows a typical response of a cell to ACh. Measured electrophysiologically, cells responded to repeated applications of ACh. In this cell line from an early stage of cochlear development, the action of ACh produced an inward current in the absence of other currents and the ACh-activated current could be measured directly (Jagger et al. 1999). The pharmacology of this current, with a binding constant KD(ACh) = 3.1 μM, insensitivity to nicotine and block by strychnine identified it as being mediated by α9AChR (Rivolta et al. 1998). The current-voltage (I-V) curve of UB/OC-2 cells was approximately linear and the action of ACh was to produce a relatively stereotyped inward current of amplitude up to 200 pA.

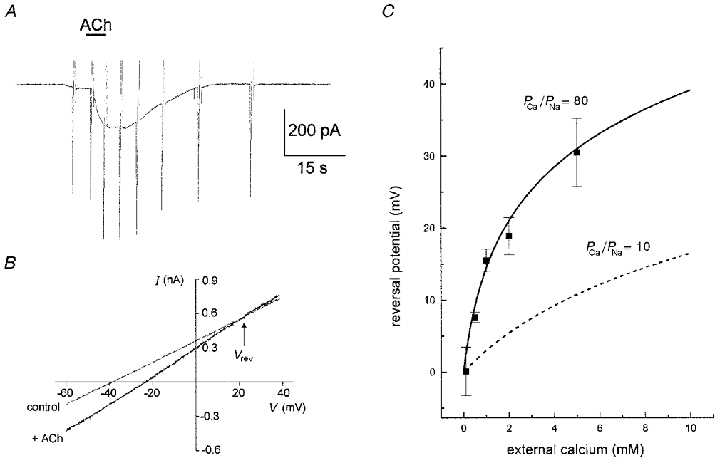

Figure 3. Effect of acetylcholine on the I–V relation of UB/OC-2 cells.

A, 10 μM ACh applied to the cell produced a slowly developing inward current when the cell was held at −40 mV. B, I–V curve applied as ramps (from −100 mV to +30 mV at 0.26 V s−1 from a holding potential of −40 mV) before and during the ACh-induced current. Reversal potential (Vrev) indicated at the I–V curve crossing point. C, measured reversal potential from a population of cells. The best fit to the data using the predictions of eqn (1) using PCa/PNa = 80 and PK/PNa = 1. The error bars show standard deviation of the data (between 6 and 15 determinations per point). For comparison, curve for PCa/PNa = 10 (a value predicted for the α7 receptor) is plotted as a dashed line.

A feature of the currents induced by ACh was a noticeably positive reversal potential (Fig. 3B). The reversal potential (Vrev) was further investigated in a variety of different external calcium solutions (Fig. 3C). The most noticeable feature of the data was the strong dependence of Vrev on external calcium, with a steady positive shift of Vrev as external calcium was increased. At the highest levels of calcium used here (5 mM) the absolute magnitude of the currents was reduced slightly compared with standard solutions, although this property was not further investigated. An explanation for this effect is that calcium itself blocks α9AChR (Katz et al. 2000).

The dependence of Vrev on external calcium was fitted by a modified form of the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation. To obtain this fit, it was assumed that ACh current was carried by Na+, K+ and Ca2+. Writing down the constant field equations for each ionic species and then solving for the reversal potential yields (Mayer & Westbrook, 1987):

| (1) |

where

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

| (1c) |

and where (PNa/PK) and (PCa/PK) are free variables chosen to fit the data optimally. We chose (PNa/PK) = 1 in accordance with a reversal potential approaching zero when calcium is low. The best fit to the data in the least squares sense was then given by (PCa/PK) = 80. This large value for the calcium permeability is anticipated from the strong dependence of Vrev on external calcium.

DISCUSSION

Calcium permeation through α9AChR

The calcium permeability of α9AChR revealed by these equilibrium experiments lies between 4 and 7 times higher than the permeability reported for the homomeric acetylcholine receptor α7 by other authors (Vernino et al. 1991; Bertrand et al. 1993). It is also over an order of magnitude higher than the nicotinic ACh receptors with well characterized subunit structure. If we use activities rather than concentrations and take activities γCa = 0.50 and γNa = 0.76 at physiological solution strengths (Lee & Tsien, 1984), the relative calcium permeability would have been still greater with PCa/PNa = 122.

At physiological solution concentrations of calcium (where, typically, Ca2+ = 1 mM and = 140 mM) we can therefore expect a sizeable fraction of the current to be carried by calcium. From the constant field equations the ratio of calcium to sodium entering the cell would be:

or approximately 70 % of the current flux. Thus, to first approximation α9AChR behaves like an ACh-gated calcium channel. This permeability is greatly in excess of values normally associated with other members of the nicotinic receptor family. For example, the ACh receptors α1–4 combined with appropriate β subunits have relative calcium permeabilities not in excess of 2. The homomeric α7 receptor has a higher calcium permeability variously reported as between 10 when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Bertrand et al. 1993) and 20 (Seguela et al. 1993). Whether the high calcium permeability of α9AChR is determined by molecular sites similar to those described for the α7AChR remains to be investigated.

Several other lines of evidence indicate that the effective calcium permeability of α9AChR in hair cells is high. Measurement of calcium levels in outer hair cells during ionophoretic application of ACh suggest that calcium does rise (Ashmore, 1992; Doi & Ohmori, 1993). The short latency of the currents induced by ACh in outer hair cells is consistent with the hypothesis that calcium permeates through the receptor (Evans, 1996). At higher levels of ACh (100 μM), slow changes in the potassium currents and in the outer hair cell motility suggest that calcium release and activation of an enzyme cascade may occur (Dallos et al. 1997). Evidence from whole-animal experiments further suggests that an abnormal patterning of efferent stimulation may lead to degenerative changes in outer hair cells (Dodson et al. 1986). In such experiments where the auditory system is stimulated by an indwelling unilateral electrode, alterations of the outer hair cells on the contralateral side are observed. One simple explanation is that elevated calcium levels within the target cells may have been involved.

α9AChR coupling to stores in UB/OC-2 cells

The recorded currents show that, in 1 mM external calcium, ACh induces a peak current of about 200 pA in a typical cell. For the cell shown in Fig. 2, this corresponds to a conductance change of 5 nS so that taking the single unit conductance of 29 pS (Jagger et al. 1998), we estimate that the cell would have contained not less than 150 α9AChR channels. We can further calculate what the effects on intracellular calcium would be: ACh would have produced an influx of 200 pA × 15 s = 3 nC of charge, or equivalently 3 × 10−9× 0.7/2 × 96 000 = 10 fmol calcium. From confocal measurements of the dimension of the cells, we estimate that each UB/OC-2 cell has a volume of approximately 20 pl. The ACh-induced rise in calcium concentration in such a cell would therefore be 500 μM. However, this large rise would be buffered and if we assume that an endogenous buffer would have a buffering capacity of 2000 (e.g. Roberts, 1994) the rise in free calcium reported by fura-2 would be about 250 nM, closer to the observed estimate. The magnitude of this calculated response arises because of the high calcium permeability of the α9AChR but depends critically upon assumptions about endogenous calcium buffering.

The experiments with caffeine suggest that a calcium rise can be triggered in these cells by calcium entry through the α9AChR. The present experiments cannot resolve the absolute time scale of such proposed release from intracellular stores. Although caffeine has been reported to interact with the indicator fura-2 (Muschol et al. 1999), the 10 mM concentration used here would have produced only a negligible effect on the ratio measurements and cannot account for the failure of ACh to elicit a subsequent response. The absence of multiple calcium responses to ACh and the discrete nature of the response suggests that α9AChR may be closely associated with mechanisms of store filling and store depletion. Such intracellular events would not be directly detected in the measurements of currents. In addition, it is possible that a calcium rise near the internal surface of the plasma membrane could itself block α9AChR, as found for external calcium (Katz et al. 2000). Similar explanations have been proposed for the actions of ACh on chick hair cells via an α9AChR (Yamamoto et al. 2000). Mechanisms of membrane store linkage, common in non-excitable cell types, have proved hard to demonstrate in hair cells even though in mammalian outer hair cells it is known that there are candidate stores, such as a prominent subsynaptic cisterna below the efferent terminal on the cell (Gulley & Reese, 1977). An association between the acetylcholine receptor and the store in UB/OC-2 cells may therefore be an intrinsic feature of α9AChR organization and assembly, but in which the high calcium permeability plays a critical role.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council and the Hearing Research Trust/Defeating Deafness. We thank Brenda Browning and Linda Churchill for invaluable technical assistance.

References

- Ashmore JF. Mechanisms of hearing and the cellular mechanisms of the cochlear amplifier. In: Corey DP, Roper S, editors. Sensory Transduction. Rockefeller University Press; 1992. pp. 396–412. [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge WH, Kurennyi DE, Barnes S. Calcium-sensitive influx in photoreceptor inner segments. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;79:3012–3018. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Galzi JL, Devillers TA, Bertrand S, Changeux JP. Mutations at two distinct sites within the channel domain M2 alter calcium permeability of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of. Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet C, Erostegui C, Sugasawa M, Dulon D. Acetylcholine-induced potassium current of guinea pig outer hair cells: its dependence on a calcium influx through nicotinic-like receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:2574–2584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, He DZ, Lin X, Sziklai I, Mehta S, Evans BN. Acetylcholine, outer hair cell electromotility, and the cochlear amplifier. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:2212–2226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson HC, Walliker JR, Frampton S, Douek EE, Fourcin AJ, Bannister LH. Structural alteration of hair cells in the contralateral ear resulting from extracochlear electrical stimulation. Nature. 1986;320:65–67. doi: 10.1038/320065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi T, Ohmori H. Acetylcholine increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration and hyperpolarizes the guinea-pig outer hair cell. Hearing Research. 1993;67:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90245-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Johnson DS, Boulter J, Vetter DE, Heinemann S. Alpha 9: an acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties expressed in rat cochlear hair cells. Cell. 1994;79:705–715. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MG. Acetylcholine activates two currents in guinea-pig outer hair cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:563–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ. Physiology of olivocochlear efferents. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The Cochlea. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 435–502. [Google Scholar]

- Gulley RL, Reese TS. Freeze-fracture studies on the synapses in the organ of Corti. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1977;171:517–543. doi: 10.1002/cne.901710407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley GD, Ashmore JF. Direct measurement of the action of acetylcholine on isolated outer hair cells of the guinea pig cochlea. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1991;244:161–167. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Holley MC, Ashmore JF. Ionic currents expressed in a cell line derived from the organ of Corti of the Immortomouse. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;438:8–14. doi: 10.1007/s004240050873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Rivolta MN, Holley MC, Ashmore JF. Cholinergic and voltage-activated currents expressed in a cochlear cell line derived from the Immortomouse. The Journal of Physiology. 1998:509–189. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Verbitsky M, Rothlin CV, Vetter DE, Heinemann SF, Elgoyhen AB. High calcium permeability and calcium block of the α9 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Hearing Research. 2000;141:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Tsien RW. High selectivity of calcium channels in single ventricular heart cells of the guinea pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;354:253–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. Permeation and block of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor channels by divalent cations in mouse cultured central neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;394:501–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschol M, Dasgupta BR, Salzberg BR. Caffeine interaction with fluorescent calcium indicator dyes. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77:577–586. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76914-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenov AP, Norris C, Bobbin RP. Acetylcholine response in guinea pig outer hair cells. II. Activation of a small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Hearing Research. 1996;101:149–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plinkert PK, Zenner HP, Heilbronn E. A nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-like alpha-bungarotoxin-binding site on outer hair cells. Hearing Research. 1991;53:123–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivolta MN, Grix N, Lawlor P, Ashmore JF, Jagger DJ, Holley MC. Auditory hair cell precursors immortalized from the mammalian inner ear. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1998;265:1595–1603. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM. Spatial calcium buffering in saccular hair cells. Nature. 1994;363:74–76. doi: 10.1038/363074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley MK, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain alpha 7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Amador M, Luetje CW, Patrick J, Dani JA. Calcium modulation and high calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90114-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Yuhas W, Fuchs P. Calcium stores modulate nicotinic inhibition of hair cells. Association for Research in Otolaryngology Abstracts. 2000;23:196. [Google Scholar]