Abstract

Impulses of human single muscle spindle afferents were recorded from the m. extensor carpi radialis, while 1 Hz sinusoidal movements for a wide range of amplitudes (0.05–10 deg, half of the peak-to-peak amplitude) were imposed at the wrist joint.

The response was considered as linear when the discharge was approximately sinusoidally modulated. The linearity was further checked by a linear increase in the response with the amplitude and a constancy of the phase and mean level.

Fifteen of 25 primary afferents were active at rest with a mean rate of 10.6 impulses s−1 (median). The linear response to sinusoidal stretching was limited to amplitudes lower than about 1.0 deg. The sensitivity was 5.6 impulses s−1 deg−1 (median) in the linear range and decreased at larger amplitudes. The other 10 primary afferents were silent at rest and lacked a linear response at low amplitudes.

Nine secondary afferents were active at rest with a mean rate of 9.5 impulses s−1. The linear range extended up to about 4.0 deg with a sensitivity of 1.4 impulses s−1 deg−1.

In the linear range, the phase advance of the response to sinusoidal stretching was about 50 deg and was similar between the two types of spindle afferents. In primary afferents, the phase advance increased to nearly 90 deg outside the linear range.

The findings suggest that high sensitivity to small stretches is important in determining primary afferent firing during natural movements in intact humans.

The response of muscle spindles to sinusoidal stretching of the muscle has been extensively studied in decerebrated cats, leading to an understanding of the basic properties of muscle spindles (Matthews & Stein, 1969; Poppele & Brown, 1970). The prominent feature of muscle spindle primary endings is that the linear response to stretching is limited to amplitudes lower than a few fractions of a millimetre (Matthews & Stein, 1969). In the linear range, primary endings possess a high stretch sensitivity. At larger amplitudes, the response to stretching is no longer linear and the stretch sensitivity is markedly reduced.

High stretch sensitivity at low amplitudes and amplitude non-linearity may be crucial in determining the response of primary endings to any input during natural movements (e.g. Matthews, 1981). Thus, to explain the meaning of spindle signals during natural movements, it is necessary to explore in intact animals how muscle spindle afferents behave during stretches for a wide range of amplitudes. Previous studies of human muscle spindle afferents examined the response to stretches of large amplitudes (Vallbo, 1973; Vallbo et al. 1979; Edin & Vallbo, 1990). However, the response to stretches at low amplitudes has not been quantitatively described.

The purpose of the present study was to give quantitative data for the human muscle spindle response to low frequency sinusoidal stretching and to analyse the effect of stretch amplitude. It will be shown that the response of primary afferents is linear to sinusoidal stretching at low amplitudes and that stretch sensitivity is markedly higher in the linear range.

Methods

Subjects

Fifteen experiments were performed on healthy volunteers, 4 males and 11 females, aged 20–37 years. All subjects gave informed, written consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental plan was approved by the Human Ethical Committee of the National Rehabilitation Centre for the Disabled, Japan.

Experimental set-up

Each subject sat comfortably in a reclining chair, with the left forearm supported on a platform and clamped in mid-position between supination and pronation. The hand was fixed to a manipulandum, which was connected to a servo-controlled torque motor, enabling measurement of joint angle, velocity and torque.

An insulated tungsten electrode was percutaneously inserted into the radial nerve 5 cm proximal to the elbow joint to record nerve activity (Vallbo et al. 1979). The location of the muscle belly of the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis was confirmed by palpation and surface electrical stimulation. To record muscle activity, a pair of surface electrodes was attached near the motor point.

Kinematic signals were sampled at 400 Hz. Surface EMG was filtered at 1.6–800 Hz and sampled at 1600 Hz. Nerve signals were recorded and sampled at 12800 Hz using a SC/ZOOM system (Department of Physiology, Umeå, Sweden). Each recorded nerve spike was inspected off-line on an expanded time scale. When it was judged to be from a single unit based on the regularity of firing and shape invariance of consecutive spikes, the nerve signal was converted to a spike train at 400 Hz for later analysis.

Unit identification

Slowly adapting muscle afferents from the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis were identified by prodding the muscle and tendon. Care was taken to confirm the origin of each afferent as the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis. Further identification procedures consisted of a passive ramp stretch and release of 16 deg and maximal twitch contraction by surface stimulation of the motor point. Muscle spindle afferents were tentatively classified as primary and secondary based on the response during ramp stretch and release. An initial burst at the start of a stretch, deceleration at the end of a stretch and the silence during the releasing phase of a stretch were considered as primary afferent signs (Edin & Vallbo, 1990).

Experimental protocol

The wrist joint was held in position at a 10 deg flexion from the horizontal. Sinusoidal movements were imposed at the wrist joint with this position taken as 0 deg. The subject was instructed to relax completely during imposed movements.

When a single muscle spindle afferent was recorded, 1 Hz sinusoidal movements of 8.0, 5.0, 2.5, 1.0, 0.50, 0.25 and 0.10 deg (half of the peak-to-peak amplitude, throughout the text) were tested in this order. Sinusoidal movements of fixed amplitude were imposed for 10–20 s (Fig. 1A) and the recording started after a few initial cycles. When recording conditions were stable, the stretch amplitude was adjusted with finer steps in the range of 0.05–10.0 deg.

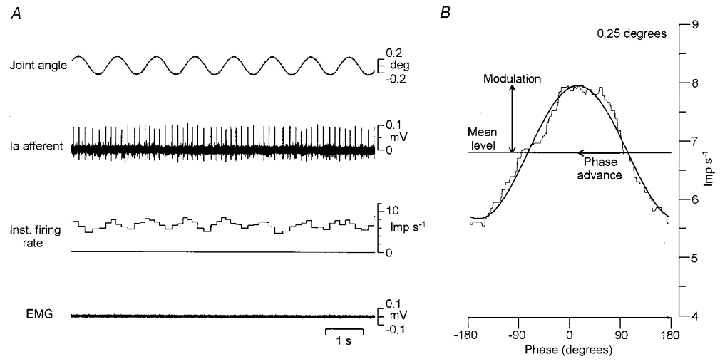

Figure 1. Measurement of the response of a primary afferent to sinusoidal stretching.

A, raw record during 1 Hz sinusoidal movements imposed at the wrist joint. The amplitude was 0.25 deg (half of the peak-to-peak amplitude). From top to bottom, joint angle, primary afferent activity and its instantaneous discharge rate and surface EMG. B, mean instantaneous discharge rate (thin line) and the fitted sine curve (thick line). The horizontal axis shows the phase of sinusoidal stretching with a range of −180 and 180 deg. The vertical axis shows the discharge rate. The horizontal line indicates the mean level, while the vertical and horizontal arrows indicate the depth of modulation and the phase advance, respectively. The depth of modulation was defined as half the peak-to-peak amplitude. The phase was defined as the difference between the fitted sine and the sinusoidal stretching.

Size of movements

The excursion of the tendon during the test movement can be roughly estimated in the following way. If the radius of the joint is approximated to 13.0 mm (Brand, 1985) and the muscle length of the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis is 186 mm (Loren & Lieber, 1995), then a 1.0 deg flexion corresponds to a 0.23 mm stretch. If it is supposed that any movement in the tendon corresponds to a muscle fibre stretch of the same amount, a 1.0 deg flexion corresponds to a 0.12 % relative stretch of the resting muscle length.

Data analysis

The records of 8–12 cycles of 1 Hz sinusoidal movements of constant amplitude were used for analysis. The procedure in this study was almost the same as the methods used in previous studies in decerebrated cats (Matthew & Stein, 1969; Hulliger et al. 1977a). The cycle of sinusoidal movement was divided into 400 bins. The mean interspike interval of all the spikes occurring in each bin was then calculated over a number of cycles. The inverse of the mean interval was the mean discharge rate. The sine curve was fitted to the mean discharge rate by the least mean square method.

The mean level, depth of modulation and phase were measured in the fitted sine (Fig. 1B). The depth of modulation was assessed as half of the peak-to peak-amplitude. The phase was defined as the difference between the fitted sine and the sinusoidal movement.

The correlation coefficient (r2) was calculated to check what proportion of variance in the mean discharge rate was attributed to the fitted sine. In the present study, data were used when the correlation coefficient was higher than 0.6. Moreover, the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) deviation of the mean discharge rate from the fitted sine was calculated to check for a goodness of fit. It was represented by the percentage of the depth of modulation.

When the amplitude of sinusoidal movements was large, primary afferents ceased firing for part of the whole cycle. In such cases, the silent period in the mean discharge rate was determined by eye and was not used for fitting the sine curve, which was allowed to project below zero (Fig. 2C). The correlation coefficient and the root-mean-square deviation were calculated in the same period as used in the fitting procedure.

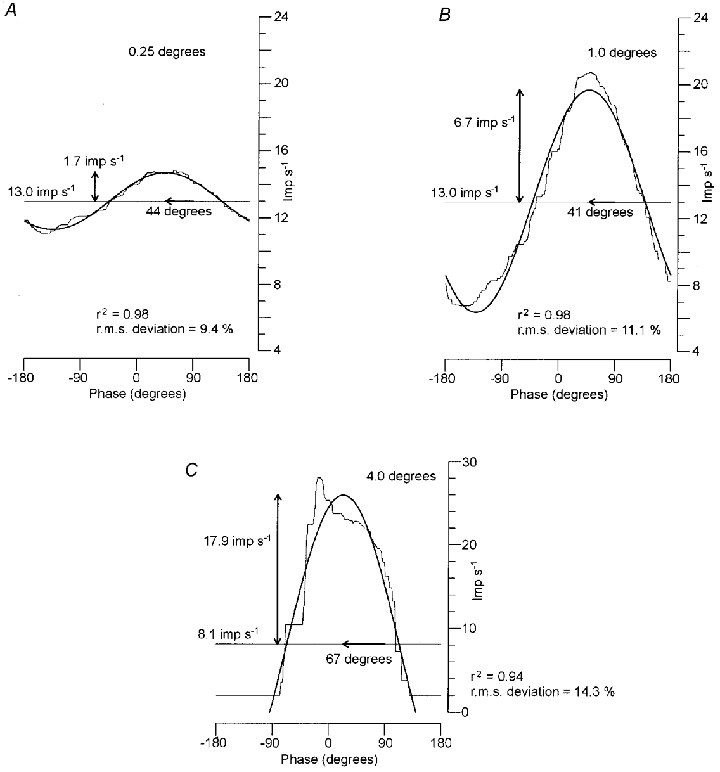

Figure 2. Response of a primary afferent to 1 Hz sinusoidal stretching at different amplitudes.

Mean instantaneous discharge rates (thin lines) and the fitted sine curves (thick lines). The stretch amplitude increased by a factor of four and was 0.25 (A), 1.0 (B) and 4.0 deg (C). The horizontal axis shows the phase of sinusoidal stretching with a range of −180 and 180 deg. The vertical axis shows the discharge rate. Note that the vertical scale in C is twice than that in A–B. The horizontal lines indicate the mean level in the fitted sine, while the vertical and horizontal arrows indicate the depth of modulation and the phase advance, respectively. In C, the mean discharge rate fell silent for about half of the cycle. The silent period was not used for fitting of the sine curve and the fitted sine projected below zero.

Results

Twenty-five muscle spindle primary afferents and nine secondary afferents were recorded from the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis. The resting discharge was assessed while the wrist joint was held in position at a 10 deg flexion from the horizontal. Fifteen primary afferents were active and the median value of the mean discharge rate was 10.6 impulses s−1 (range, 3.4–18.9). The other 10 primary afferents were silent. All secondary afferents were active and the median value of the mean discharge rate was 9.5 impulses s−1 (range, 3.4–14.9).

When the subjects relaxed completely, the spindle discharge was relatively regular and the discharge rate was low. Spontaneous fluctuations in the mean level of discharge rate were not observed. Fusimotor action was therefore probably low and henceforth will be considered negligible, in agreement with previous conclusions for human subjects (e.g. Vallbo et al. 1979).

Measurement of spindle response to sinusoidal stretching

Figure 1 shows a representative result of primary afferent behaviour during sinusoidal stretches at low amplitudes. Figure 1A shows the raw record while 1 Hz sinusoidal movements of 0.25 deg (half of the peak-to-peak amplitude) were imposed at the wrist joint. The discharge is clearly modulated by sinusoidal movements, as seen in the instantaneous discharge rate.

Figure 1B shows the instantaneous discharge rate averaged cycle by cycle (thin line) and the fitted sine curve (thick line), and illustrates the measurement of the response. The discharge was sinusoidally modulated (r2 = 0.98) around the mean level of 6.8 impulses s−1. The depth of modulation was 1.15 impulses s−1 (half of the peak-to-peak amplitude) and the phase advance to the sinusoidal movement was 75 deg. The root-mean-square deviation of the mean discharge rate from the fitted sine was 0.13 impulses s−1, equal to 11.1 % of the depth of modulation.

Response of a primary afferent to stretching with a widely ranging amplitude

Figure 2 shows the mean discharge rates (thin line) and the fitted sine curves (thick line) of a primary afferent. The mean level of resting discharge was 13.2 impulses s−1. The amplitude of sinusoidal movements increased by a factor of four and was 0.25 (A), 1.0 (B) and 4.0 deg (C).

In Fig. 2A and B, the discharge was approximately sinusoidally modulated (r2 = 0.98 in both). The depth of modulation was 1.7 impulses s−1 at 0.25 deg (A) and 6.7 impulses s−1 at 1.0 deg (B), and the increase was proportional to the amplitude. The mean level (13.0 impulses s−1) and phase advance (44 and 41 deg) held constant between A and B. Accordingly, the response in A and B may be regarded to fall in the linear range. The root-mean-square deviation held at about 10 %.

When the amplitude increased by a further factor of four, the afferent ceased firing for about half of a whole cycle (C). The response was not sinusoidal and apparently outside the linear range. The silent period was not used for fitting the sine curve (see Methods). The fitted sine ranged between −9.7 and 26.0 impulses s−1 and the mean level decreased to 8.1 impulses s−1. The depth of modulation was 17.9 impulses s−1 and the increase was less than proportional to the amplitude. The phase advance increased to 67 deg, which was a further sign of non-linearity. The root-mean-square deviation increased to 14.3 %.

Relation between amplitude of stretching and response of a primary afferent

Figure 3 shows the relation between the amplitude of stretching and the response of the primary afferent in Fig. 2. The amplitude ranged between 0.05 and 8.0 deg. The r2 value was higher than 0.6 at any amplitude, indicating that the discharge was significantly modulated. The depth of modulation (A), the mean level (B), the phase advance (C) and the root-mean-square deviation (D) are plotted against the amplitude.

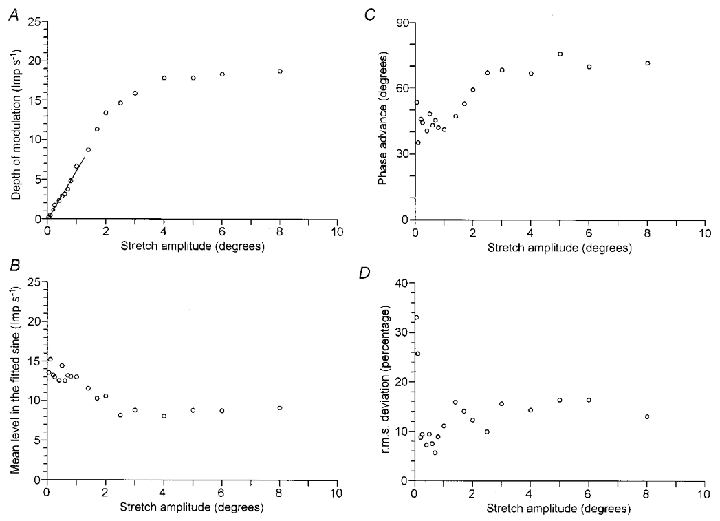

Figure 3. Relation between the amplitude of stretching and the response of a primary afferent.

The effect of stretch amplitude is shown in the same primary afferent as Fig. 2. The stretch amplitude ranged between 0.05 and 8.0 deg. The depth of modulation (A), the phase advance (B), the mean level in the fitted sine (C) and the root-mean-square deviation of the mean discharge rate from the fitted sine (D) are plotted against the amplitude of sinusoidal stretching. In A, linear regression was applied to the points below 1.0 deg (r2 = 0.98). The y-intercept was −0.19 impulses s−1 and the slope was 6.3 impulses s−1 deg−1.

The depth of modulation (A) linearly increased at amplitudes between 0.05–2.0 deg. On the other hand, the mean level (B) held constant up to only 1.0 deg and progressively decreased at larger amplitudes. This reduction was related with the distortion of the response from the sine curve, and in particular with the cessation of discharges for part of the whole cycle. Thus, the increase in the depth of modulation between 1.0–2.0 deg was, in part, due to the reduction in the mean level. Similarly to the mean level, the phase advance (C) held constant up to 1.0 deg and then increased at larger amplitudes. From A–C, it is confirmed that the linear response was limited to amplitudes up to 1.0 deg. In Fig. 3A, linear regression was applied to the points below 1.0 deg (r2 = 0.98). The line passes near the origin and the slope indicates a sensitivity of 6.3 impulses s−1 deg−1.

The root-mean-square deviation (D) stayed at about 10 % between 0.2 and 1.0 deg and increased at larger amplitudes. This suggests that the fitting of the sine curve to the mean discharge rate was good in the linear range. (The value at both 0.05 and 0.10 deg was about 30 %. The depth of modulation was less than 0.5 impulses s−1 at amplitudes lower than 0.10 deg, so that the spontaneous variation in the discharge was not negligible.)

Linear range of primary and secondary afferents

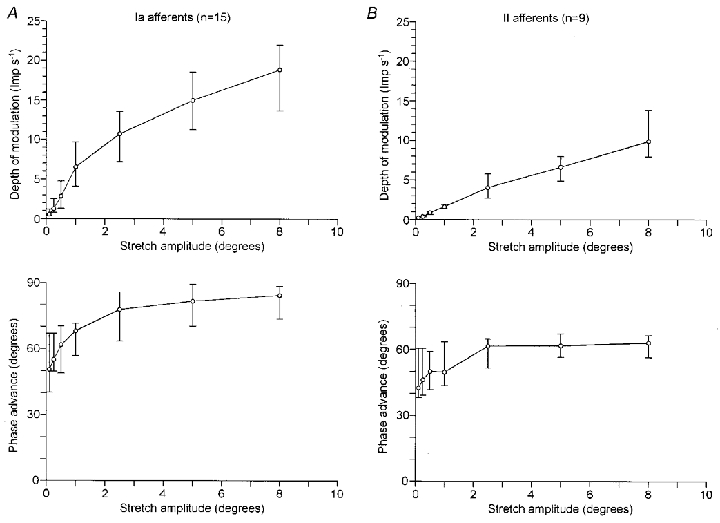

Fifteen of 25 primary afferents were active at rest. The discharge was significantly modulated (r2 > 0.6) in 10 afferents at 0.10 deg and in all afferents above 0.25 deg. The median value of the linear range was 1.0 deg (range, 0.2–1.9). In the linear range, the median value of the sensitivity was 5.6 impulses s−1 deg−1 (range, 3.0–22.6). The medians and quartiles (25 and 75 %) of the depth of modulation were plotted against the amplitude of stretching in the upper graph of Fig. 4A. The linear increase was limited to amplitudes lower than 1.0 deg in the total sample.

Figure 4. Summary of the response of 15 primary and 9 secondary muscle spindle afferents to 1 Hz sinusoidal stretching.

The effect of stretch amplitude on the response of primary and secondary afferents is summarised in A and B, respectively. The upper graphs plot the depth of modulation against the amplitude of stretching, while the lower graphs plot the phase advance. ○, medians, and horizontal bars indicate the quartiles (25 % and 75 %).

The other 10 primary afferents were silent at rest. They started firing during sinusoidal movements at 0.90 deg (median). At any amplitude, they ceased firing for part of the whole cycle and the response was different from the sine curve. They lacked a linear response to stretches at low amplitudes, while the response at amplitudes above about 1.0 deg was similar to that in Fig. 4A.

All nine secondary afferents were active at rest. The modulation of the discharge was significant in three afferents at 0.10 deg, in seven afferents at 0.25 deg and in all afferents above 0.50 deg. The median value of the linear range was 3.6 deg (range, 1.0–8.0). The median value of the sensitivity was 1.4 impulses s−1 deg−1 (range, 0.88–3.1). The upper graph of Fig. 4B plots the depth of modulation in the total sample, which linearly increased with the amplitude up to 8 deg.

Phase advance

The phase advance of the response to sinusoidal stretching in the total sample was plotted in the lower graphs of Fig. 4. In primary afferents (A), the phase advance increased from 50 to 70 deg at amplitudes between 0.1 and 1.0 deg. Some afferents fell outside the linear range at 0.5 or 1.0 deg, accompanying the increase in the phase advance. In secondary afferents (B), the phase advance ranged between 40 and 60 deg. Therefore, the phase advance was about 50 deg in the linear range and similar between the two types of spindle afferents. Both types of afferents respond to the compound of the position and the velocity components of sinusoidal stretching.

In primary afferents, the phase advance increased to about 80 deg at amplitudes above 1.0 deg. This indicates that the velocity component was dominant in determining the response of primary afferents outside the linear range.

Response of spindle afferents to large amplitude ramp stretching

The sensitivity of muscle spindles to large stretches was measured for comparison to the stretch sensitivity at low amplitudes. A ramp stretch of 16 deg was applied at the wrist joint over 0.9 s with a speed of about 18 deg s−1.

The static position response was defined as the difference in discharge rate between that just before the start of the stretch and that during the static phase of the stretch. The latter was assessed as the mean rate during the holding phase between 0.5–1.5 s after the end of the stretch. The dynamic response was measured as the dynamic index, which was defined as the difference in discharge rate between that just before the end of the stretch and that during the static phase of the stretch (Edin & Vallbo, 1990; Kakuda & Nagaoka, 1998).

The response to the ramp stretch was recorded in ten primary and seven secondary afferents of Fig. 4. The median value of the static position response was 5.3 impulses s−1 (range, 3.3–10.2) and 6.7 impulses s−1 (range, 5.8–10.4) in the primary and secondary afferents, respectively. The static sensitivities were calculated as 0.33 impulses s−1 deg−1 and 0.42 impulses s−1 deg−1, respectively, and similar between the two types of spindles. The median value of the dynamic index was 10.5 impulses s−1 (range, 6.1–15.0) and 4.6 impulses s−1 (range, 1.8–7.4) in the primary and afferents, respectively. The dynamic index of primary afferents was larger than that of secondary afferents. These results are compatible with previous data recorded in human forearm muscles (Vallbo, 1973; Edin & Vallbo, 1990) and in isolated human intercostal muscles (Newsom Davis, 1975).

The sensitivity of the primary afferents to sinusoidal stretching at low amplitudes (5.6 impulses s−1 deg−1) was more than 10-fold of the static sensitivity (0.33 impulses s−1 deg−1). It was also much higher than the dynamic index (10.5 impulses s−1), considering the amplitude (16 deg) and the speed (18 deg s−1) of the ramp stretch. In secondary afferents, the sensitivity to sinusoidal stretching (1.4 impulses s−1 deg−1) was of the same order of magnitude as the static sensitivity (0.42 impulses s−1 deg−1) and the dynamic index (4.6 impulses s−1) of the large ramp stretch.

Discussion

The present study gives the first quantitative description of the response of human muscle spindle afferents to low frequency sinusoidal stretching over widely ranging amplitudes.

The main finding was that the response of primary afferents to 1 Hz sinusoidal stretching at amplitudes below about 1.0 deg was linear. The stretch sensitivity in the linear range was markedly higher, compared with the sensitivity at larger amplitudes. In secondary afferents, the linear range extended to larger amplitudes and the stretch sensitivity was about one-fourth to one-fifth of that of the primary afferents. In the linear range, both position and velocity components of stretching contributed to the response and the two types of spindle afferents were similar in this respect. The appearance of non-linearity in the spindle responses provides further evidence that fusimotor activity is low for relaxed human muscles (Hulliger et al. 1977a; Cussons et al. 1977).

Comparison to muscle spindles in the decerebrated cats

The linear range of human primary afferents was 1.0 deg at the wrist joint, estimated to be 0.23 mm and 0.12 percentage of the resting muscle length (see Methods). The stretch sensitivity of 5.6 impulses s−1 deg−1 corresponded to 24 impulses s−1 mm−1 and 47 impulses s−1 (percentage of the resting muscle length)−1. In the primary endings of the soleus muscle (length 50 mm) in decerebrated cats with intact ventral roots, the linear range was about 0.1 mm and 0.2 percentage of the resting muscle length. The sensitivity was about 100 impulses s−1 mm−1 and 50 impulses s−1 (percentage of the resting muscle length)−1 (Matthews & Stein, 1969; Hulliger et al. 1977a). In absolute modulation (impulses s−1) and sensitivity (impulses s−1 mm−1), the present data are smaller than expected from the data for the cat. However, when the sensitivity is expressed in relation to resting muscle length, the figures are more uniform.

The morphological evidence suggests that the difference in absolute modulation (impulses s−1) and sensitivity (impulses s−1 mm−1) is not attributable to fundamental differences in structure per se between human and cat spindles (Hulliger, 1984). It is conceivable that the spindle sensitivity (impulses s−1 mm−1) is related to the resting muscle length. In long muscles, spindles need not lie in parallel with the entire length of extrafusal muscle fibres. Instead, they often originate from, and insert at, extrafusal muscle fibres, so that they are arranged in series with compliant elements (Baker, 1974). Given that human spindles are not longer than cat spindles, locally effective length changes during stretch might constitute a smaller fraction of the change in whole-muscle length than for the much shorter muscles in cats (Hulliger, 1984).

Although the spindle sensitivity might be related to resting muscle length, it also seems likely that the lower sensitivity of human primary afferents is at least partly due to experimental conditions. The present data were obtained with the wrist near its mid position, far from the position at which the m. extensor carpi radialis brevis would be at its maximal physiological length. On the other hand, the data for the cat were obtained at the maximal physiological length of the muscle. If the fusimotor activity is eliminated after cutting the ventral roots in decerebrated cats, spindle endings have a high sensitivity when the muscle is at physiological full extension, but not when the muscle is shorter (Matthews & Stein, 1969). Therefore, the difference in sensitivity (impulses s−1 mm−1) between the data for human subjects and that for the cat might be partly due to the difference in extension of the muscles and to the low fusimotor action for relaxed human muscles.

The sensitivity of human secondary afferents was 1.4 impulses s−1 deg−1 (6.2 impulses s−1 mm−1) in the linear range and it was about one-fourth of that of primary afferents. Considering the differences in experimental conditions, it would be worth noting that the difference in sensitivity to small stretching between the two types of spindles for relaxed human subjects was of the same order of magnitude as that for decerebrated cats (Matthews & Stein, 1969; Cussons et al. 1977).

Functional implications

The discharge rate of human spindle afferents is usually 0–30 impulses s−1 and rarely exceeds 50 impulses s−1 during natural movements (Vallbo et al. 1979). Although the discharge rate is rather low, the present data show that small stretches of the muscle appreciably modulate the discharge rate of the primary afferents. A 1 deg movement at the wrist joint produces a modulation of 6 impulses s−1 in a primary afferent, corresponding to 60 % of the pre-existing level (about 10 impulses s−1). It seems reasonable to conclude that the high stretch sensitivity at low amplitudes plays an important part in determining the spindle activity, at least during passive movements.

The stretch sensitivity of muscle spindles may be affected by the fusimotor activity during voluntary contractions and it is necessary to address whether the high stretch sensitivity at low amplitudes is maintained or not during voluntary contractions. In decerebrated cats, the stretch sensitivity of the primary endings at low amplitudes is reduced by stimulation of a fusimotor fibre, irrespective of dynamic or static fibre. When both dynamic and static fibres are stimulated, the reduction in sensitivity is dependent on the balance between the two types of fusimotor actions (Goodwin et al. 1975; Hulliger et al. 1977a,b). It was suggested in humans that both dynamic and static fusimotor neurones are active during voluntary contractions, when the spindle response was tested by a large amplitude ramp stretch (Kakuda & Nagaoka, 1998). Thus, the fusimotor system possibly maintains and controls the stretch sensitivity of primary endings at low amplitudes during voluntary contractions. As a result, the primary afferents can signal small length changes in the muscle occurring during slow voluntary movements (Wessberg & Vallbo, 1995).

The present data support the view that the muscle spindles contribute to the detection of small passive movements (McCloskey, 1978; Proske et al. 2000). This argument is based on the observation that significant modulation in the discharge rate was obtained during sinusoidal stretches at 0.10 deg in 10 of 25 primary afferents. The threshold amplitude of the primary afferents may be compatible with the psychophysical results. For example, threshold detection of movements imposed at the elbow joint is about 0.1 deg (Wise et al. 1998). It was shown in humans that both muscle spindles and slowly adapting type II cutaneous mechanoreceptors provide reasonable velocity signals of passive movements at large amplitudes (Grill & Hallett, 1995), implying the contribution of both types of sensory inputs to movement perception. To investigate the relative roles of muscle spindles and cutaneous mechanoreceptors in the detection of movements, particularly at small amplitudes, it would be helpful to examine the response of cutaneous mechanoreceptors to small stretches as used in the present study.

In conclusion, muscle spindle primary afferents in humans respond linearly to stretches at low amplitudes with high responsiveness. This suggests that high sensitivity to small stretches is important in the determination of primary afferent firing during natural movement and that muscle spindles contribute to fine motor control, as well as kinaesthetic sensibility.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

References

- Baker D. The morphology of muscle receptors. In: Hunt CC, editor. Handbook of Sensory Physiology, Muscle Receptors. part 2. vol. 3. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1974. pp. 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Brand PW. Clinical Mechanics of the Hand. Toronto & Princeton: The C. V. Mosby, Company St Louis; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cussons PD, Hulliger M, Matthews PBC. Effects of fusimotor stimulation on the response of the secondary ending of the muscle spindle to sinusoidal stretching. The Journal of Physiology. 1977;270:835–850. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin BB, Vallbo Å B. Dynamic response of human muscle spindle afferents to stretch. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:1297–1306. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, Hulliger M, Matthews PBC. The effect of fusimotor stimulation during small amplitude stretching on the frequency-response of the primary ending of the mammalian muscle spindle. The Journal of Physiology. 1975;253:175–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill SE, Hallett M. Velocity sensitivity of human muscle spindle afferents and slowly adapting type II cutaneous mechanoreceptors. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:593–602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulliger M. The mammalian muscle spindle and its central control. Reviews in Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1984;101:1–110. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulliger M, Matthews PBC, Noth J. Static and dynamic fusimotor action on the response of Ia fibres to low frequency sinusoidal stretching of widely ranging amplitude. The Journal of Physiology. 1977a;267:811–838. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulliger M, Matthews PBC, Noth J. Effects of combining static and dynamic fusimotor stimulation on the response of the muscle spindle primary ending to sinusoidal stretching. The Journal of Physiology. 1977b;267:839–856. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuda N, Nagaoka M. Dynamic response of human muscle spindle afferents to stretch during voluntary contraction. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.621bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loren GJ, Lieber RL. Tendon biomechanical properties enhance human wrist muscle specialization. Journal of Biomechanics. 1995;28:791–799. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00137-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DI. Kinaesthetic sensibility. Physiological Reviews. 1978;58:763–820. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PBC, Stein RB. The sensitivity of muscle spindle afferents to small sinusoidal changes of length. The Journal of Physiology. 1969;200:723–743. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PBC. Muscle spindles: their message and their fusimotor supply. In: Brookes VB, editor. Handbook of Physiology, The Nervous System, Motor Control. part 2. vol. II. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 189–228. section 1. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom Davis J. The response to stretch of human intercostal muscle spindles studied in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1975;249:561–579. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Wise AK, Gregory JE. The role of muscle receptors in the detection of movements. Progress in Neurobiology. 2000;60:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppele RE, Brown RJ. Quantitative description of linear behavior of mammalian muscle spindles. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1970;33:59–72. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo Å B. Afferent discharge from human muscle spindles in non-contracting muscles. Steady state impulse frequency as a function of joint angle. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1973;90:303–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1974.tb05593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo ÅB, Hagbarth K-E, Torebjörk HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiological Reviews. 1979;59:919–957. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessberg J, Vallbo Å B. Coding of pulsatile motor output by human muscle spindle afferents during slow finger movements. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:833–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise AK, Gregory JE, Proske U. Detection of movements of the human forearm during and after co-contractions of muscles acting at the elbow joint. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.325br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]