Abstract

Fast synaptic transmission is triggered by the activation of presynaptic Ca2+ channels which can be inhibited by Gβγ subunits via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). Regulators of G protein signalling (RGS) proteins are GTPase-accelerating proteins (GAPs), which are responsible for >100-fold increases in the GTPase activity of G proteins and might be involved in the regulation of presynaptic Ca2+ channels. In this study we investigated the effects of RGS2 on G protein modulation of recombinant P/Q-type channels expressed in a human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cell line using whole-cell recordings.

RGS2 markedly accelerates transmitter-mediated inhibition and recovery from inhibition of Ba2+ currents (IBa) through P/Q-type channels heterologously expressed with the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 (mAChR M2).

Both RGS2 and RGS4 modulate the prepulse facilitation properties of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. G protein reinhibition is accelerated, while release from inhibition is slowed. These kinetics depend on the availability of G protein α and βγ subunits which is altered by RGS proteins.

RGS proteins unmask the Ca2+ channel β subunit modulation of Ca2+ channel G protein inhibition. In the presence of RGS2, P/Q-type channels containing the β2a and β3 subunits reveal significantly altered kinetics of G protein modulation and increased facilitation compared to Ca2+ channels coexpressed with the β1b or β4 subunit.

Calcium elevation in the central nervous system (CNS) through voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels regulates a wide range of intracellular processes including synaptic transmission, calcium-dependent second messenger pathways, and gene transcription. Ca2+ channels are composed of an α1, β, α2δ and possibly a recently found γ subunit in the brain. Presently there are five types of Ca2+ channels expressed in the CNS: L-, N-, P/Q-, R- and T-type. A characteristic of the presynaptic P/Q-type and N-type Ca2+ channels is their inhibition by pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G proteins, Gi/o and more recently PTX-insensitive G protein, Gz (Hille, 1994; Jeong & Ikeda, 1998). Past electrophysiological studies have shown that the expression of Gβγ subunits in HEK293 cells or sympathetic neurons is sufficient to inhibit the P/Q- and N-type Ca2+ currents (Herlitze et al. 1996; Ikeda, 1996). Additionally this G protein-dependent inhibition can be reversed with high prepulse depolarizations presumably by releasing Gβγ subunits from the Ca2+ channel. The intracellular loop connecting domains I and II (which contains the QXXER binding motif) of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit as well as the C-terminus have been shown to be involved in Gβγ binding and channel modulation (De Waard et al. 1997; Dolphin et al. 1999; Herlitze et al. 1997; Page et al. 1997; Qin et al. 1997; Zamponi et al. 1997).

Receptor activation via a neurotransmitter initiates the exchange of GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit, allowing the dissociation of its Gβγ counterpart to interact with different effectors such as ion channels. The hydrolysis of GTP to GDP on the Gα subunit leads to the reassociation of the Gβγ dimer to the Gα subunit and termination of the signal (Hamm, 1998). The termination of the G protein signal is accelerated by a superfamily of GAPs known as RGS proteins (for review see Siderovski et al. 1996; Dohlman & Thorner, 1997; Koelle, 1997; Neer, 1997; Berman & Gilman, 1998; Zerangue & Jan, 1998). More than 20 RGS proteins have been identified and share a highly conserved 130 amino acid region responsible for GTPase activity. These proteins mediate the fast kinetics of GTP hydrolysis for the Gi/o, Gq, G12 and Gz families and are responsible for up to 100-fold increases in in vivo GTP hydrolysis compared to in vitro biochemical studies (Zerangue & Jan, 1998).

Rapid transmission of signals is required for the transfer of information between neurons in which P/Q-type Ca2+ channels play an important role. The modulation of the P/Q-type channels by RGS proteins has not been investigated. Here we describe the influence of RGS2 and 4 on the kinetics of G protein modulation of IBa through P/Q-type Ca2+ channels heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells. Our results demonstrate that RGS proteins accelerate the transmitter-mediated inhibition and recovery from G protein inhibition of P/Q-type channels. The kinetics of prepulse facilitation for P/Q-type channels in the presence of RGS proteins indicate that RGS proteins increase the available Gβγ subunit concentration and reveal effects of Gαi subunits on the release of G protein inhibition. Furthermore we detected an important role for Ca2+ channel β subunits in the kinetics of G protein modulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in the presence of RGS2.

METHODS

Cloning of RGS and β2a cDNAs

Reverse transcription and PCR amplification were used to clone RGS4 from adult mouse brain RNA using the following primers:

for sense, TCGAATTCTATGTGCAAAGGACTTGCAGGTCTG;

for antisense, CGCGGTACCTTAGGCACACTGGGAGACCAGGGA.

The entire nucleotide sequence was verified to the mouse RGS4 (Gen Bank accession no. AB004315) by cDNA sequencing. The cloning of RGS2 was described previously by Herlitze et al. (1999).

β2a was amplified by PCR from the p91023(b)-βb24 clone which was kindly provided by Dr Perez-Reyes (Department of Pharmacology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA) using the following primers:

for sense, CTCAGATCTATGCAGTGCTGCGGGCTGGTA;

for antisense, CTCAAGCTTTCATTGGCGGATGTATACATC.

The entire nucleotide sequence was verified by cDNA sequencing.

Expression of clones and mutagenesis

cDNAs encoding Ca2+ channel subunits α1A (rbA isoform) were cloned in pMT2XS1 (Starr et al. 1991), β1b in pMT2XS (Stea et al. 1993), β2a, β3 and β4 in pcDNAIII (Perez-Reyes et al. 1992; Castellano et al. 1993a,b), α2δ in pZEM228 (Ellis et al. 1988), GFP (green fluorescence protein) in pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, California), Gαi1 in pCD-PS (Jones & Reed, 1987) and Gβ1 in CDM8.1 (Fong et al. 1986), RGS2 and 4 in pcDNAIII (Herlitze et al. 1999) and M2 mAChR in pcDNAIII. The Ca2+ channel α1A/QQIEE mutant was constructed previously by Herlitze et al. (1997) and subcloned into pMT2XS1. HEK293 cells were transfected with the Ca2+ channel subunits α1A, α2δ and β1b cDNAs in a 1:1:1 molar ratio plus GFP cDNA in a 1:10 molar ratio with lipofectamine (GibcoBRL, Life Technologies) and incubated for at least 48 h. In some cases the Ca2+ channel subunits were cotransfected with different RGS proteins (RGS2 and 4), Gβ1, Gαi1 or M2 mAChR cDNAs in a 1:1 molar ratio as indicated in the figures. In other cases various Ca2+ channel β subunits (β2a, β3 or β4) were transfected instead of β1b and the α1A/QQIEE (Herlitze et al. 1997) mutant for the wild-type α1A/QQIER as indicated in the figures.

Electrophysiology

Positively transfected cells were identified by green fluorescence from GFP expression and analysed by whole-cell patch clamp (Hamill et al. 1981). Patch electrodes were pulled from a quartz glass capillary (1·0 mm outer diameter, 0·70 mm inner diameter; Science Products GmbH, Hofheim, Germany). The patch electrodes had a resistance of 2·0–3·0 MΩ when filled with the intracellular solution (120 mM aspartic acid, 5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM Mg-ATP with pH adjusted to 7·3 with CsOH). An Ag-AgCl-coated coil was used to ground the external solution (100 mM Tris, 4 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM BaCl2 with pH adjusted to 7·3 with methanesulfonic acid). The cell membrane capacitance and series resistance were compensated electronically using the patch clamp amplifier (EPC-9; HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Voltage protocol design and data aquisition were performed using the Pulse++ 1.7 software (Ulix GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany) on a Macintosh Power PC. Cells were bathed and recorded in the external solution at room temperature. Currents were recorded with 10 mM Ba2+ as the current carrier. When indicated in the figure legends, guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) or guanosine 5′-(γ-thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) was added to the internal solution at a final concentration of 0·6 mM. For M2 mAChR-mediated inhibition studies, 10 μM ACh was applied to cells via a gravity-fed quartz glass capillary tube connected to polyethylene tubing. The tip of the application system was located within 100 μm of the cell. ACh application was initiated for 15 s and terminated by switching between the control external solution and ACh-containing external solution. The external solution was removed at a rate of approximately 1 ml min−1.

Data analysis

ACh-evoked currents were analysed and fitted with a single exponential function at +10 mV and time constants of inhibition (τinhib) and recovery (τrec) from inhibition were obtained using the IGOR data analysis package (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). For double-pulse voltage protocols time constants for reinhibition (τreinhib) and release from inhibition (τrelease from inhib) were obtained by fitting the peak current traces at +10 mV measured after 3·9 ms with a single exponential function. Relative facilitations were determined by dividing the peak currents measured after 3·9 ms from the last time point of the second test pulse by the first test pulse at +10 mV. Data were presented as means ± standard error of means (s.e.m.). Student’s two-tailed t tests were performed on the data to determine statistical significance. As indicated with a *, control means were compared to respective +RGS means. As indicated with a †, secondary comparisons were performed for significance in Figs 4 and 5 where means ± s.e.m. from cells without Gαi1 were compared to cells with Gαi1, and means ± s.e.m. from Ca2+ channel β3 subunits were compared to β1b, β2a or β4 subunits, respectively. Statistical significance was expressed as * or †, P < 0·05.

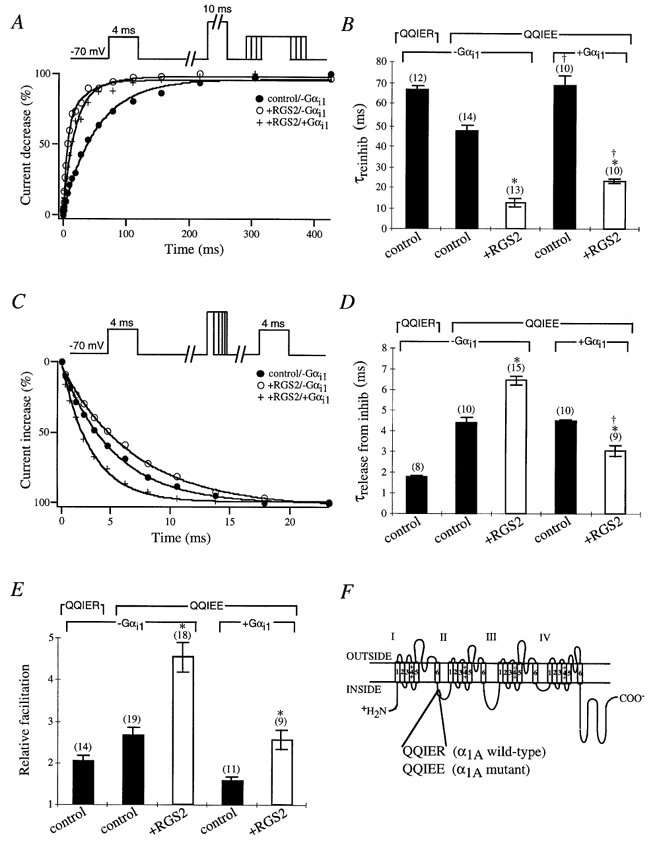

Figure 4.

Effects of RGS2 on the G protein modulation of α1A/QQIEE mutant in the presence of GTPγS

A, sample time courses of reinhibition are shown from cells expressing the α1A/QQIEE mutant in the presence (control; •) or absence (○) of RGS2 and in the presence of RGS2 plus Gαi1 subunit (+) with GTPγS in the intracellular solution. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a 10 ms conditioning prepulse to +100 mV was applied to completely relieve G protein inhibition, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 1–427 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the smallest peak current from the second test pulse, and reinhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at −70 mV between the prepulse and second test pulse. B, time constants for IBa reinhibition are shown from cells expressing the α1A/QQIER wild-type or α1A/QQIEE mutant with (□) or without (control; ▪) RGS2. Time courses of IBa reinhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τreinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. In some cases the Gαi1 subunit was coexpressed as indicated. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test. C, sample time courses of release from inhibition are shown from cells expressing the α1A/QQIEE mutant in the presence (control; •) or absence (○) of RGS2 and in the presence of RGS2 plus Gαi1 subunit (+) with GTPγS in the intracellular solution. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a conditioning prepulse to +100 mV for a period of 1–23 ms was applied, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 10 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the largest peak current from the second test pulse, and recovery from inhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at +100 mV. D, time constants for IBa release from inhibition are shown from cells expressing the α1A/QQIER wild-type or α1A/QQIEE mutant with (□) or without (control; ▪) RGS2. Time courses of IBa release from inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrelease from inhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. In some cases a Gαi1 subunit was coexpressed as indicated. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test. E, relative means (± s.e.m.) of facilitation were determined from cells expressing the α1A/QQIER wild-type or α1A/QQIEE mutant with (□) or without (control; ▪) RGS2 as indicated. In some cases a G protein αi1 subunit was coexpressed as indicated. Currents were normalized to the largest peak current of the second test pulse versus the first test pulse from the traces in B and D. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test. F, schematic diagram of the α1A subunit of the P/Q-type Ca2+ channel depicting the G protein-binding QXXER motif between loops I and II. The QXXER motif in the wild-type α1A subunit QQIER was mutated to QQIEE (Herlitze et al. 1997).

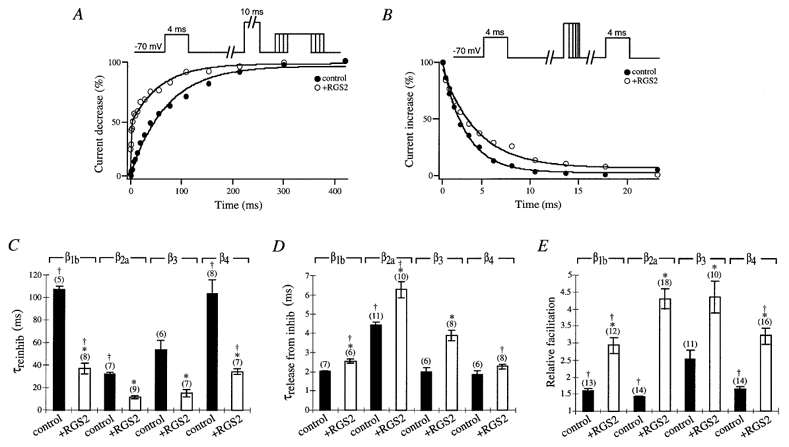

Figure 5.

Effect of different Ca2+ channel β subunits on the G protein modulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in the presence of RGS2 and Gβ1 subunit

A, sample time courses of reinhibition are shown from cells expressing Gβ1 subunit and Ca2+ channel β3 subunit with (○) or without (control; •) RGS2. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a 10 ms conditioning prepulse to +100 mV was applied to completely relieve G protein inhibition, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 1–427 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the smallest peak current from the second test pulse, and reinhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at −70 mV between the prepulse and second test pulse. B, sample time courses of release from inhibition are shown from cells expressing Gβ1 subunit and Ca2+ channel β3 subunits with (○) or without (control; •) RGS2. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a conditioning prepulse to +100 mV for a period of 1–23 ms was applied, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 10 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the largest peak current from the second test pulse, and release from inhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at +100 mV. C, time constants for IBa reinhibition are shown from control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells with Gβ1 subunit and Ca2+ channel β1b, β2a, β3 or β4 subunits as indicated. Time courses of reinhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τreinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test. D, time constants for IBa release from inhibition are shown from control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells with Gβ1 subunit and Ca2+ channel β1b, β2a, β3 or β4 subunits as indicated. Time courses of IBa release from inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrelease from inhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test. E, relative means (± s.e.m.) of facilitation were determined from control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells with Gβ1 subunit and Ca2+ channel β1b, β2a, β3 or β4 subunits as indicated. Currents were normalized to the largest peak current of the second test pulse versus the first test pulse from the traces in C and D. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * and † P < 0·05, Student’s t test.

RESULTS

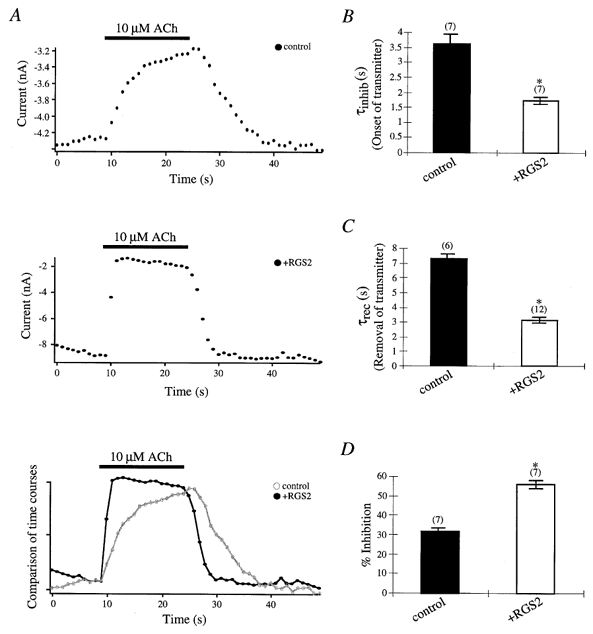

RGS2 accelerates the M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition and recovery from inhibition of P/Q-type channels

N-type Ca2+ channels were demonstrated to be inhibited by noradrenaline (norepinephrine) via Gβγ subunits in superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurons (Herlitze et al. 1996; Ikeda 1996). In addition, the recovery from G protein inhibition for recombinant and native N-type channels in SCG neurons was shown to be accelerated by coexpression of RGS proteins (Bünemann & Hosey, 1998; Jeong & Ikeda, 1998; Melliti et al. 1999). To examine the effects of RGS proteins on the G protein modulation of P/Q-type channels, we cotransfected the α1A, β1b and α2δ subunits of the P/Q-type channel with a GPCR, the M2 mAChR and one RGS protein, RGS2 in HEK293 cells and analysed the time dependence of ACh-induced inhibition of IBa through Ca2+ channels. Figure 1A illustrates the time courses of inhibition in a cell expressing RGS2 compared to the control cell not expressing RGS2. The IBa were elicited every second by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. Time constants from ACh-induced inhibition were calculated by fitting the inhibition and recovery curves following 10 μM ACh application (τinhib; Fig. 1B) and removal (τrec; Fig. 1C), respectively. In control cells not expressing RGS2, 10 μM ACh application induced a slow M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition (τinhib = 3·62 ± 0·31 s (n = 7)) compared to cells expressing RGS2 (τinhib = 1·74 ± 0·11 s (n = 7)). Additionally RGS2 markedly accelerated the recovery from M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition after the removal of ACh (τrec = 3·14 ± 0·18 s (n = 12)) compared to control cells (τrec = 7·27 ± 0·41 s (n = 6)). RGS2 also significantly enhanced IBa inhibition by 55·90 ± 2·10 % (n = 7) compared to 31·52 ± 2·62 % (n = 7) in control cells. Collectively these results indicate that RGS2 accelerates and increases the M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition of P/Q-type channels. As expected recovery from inhibition after transmitter removal was also accelerated because of the GAP activity of RGS2.

Figure 1.

Effects of RGS2 on M2 mAChR-mediated inhibition and recovery from inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

A, sample time courses of M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition in a control (top trace) and RGS2- expressing (middle trace) cell are shown following application and removal of 10 μM ACh. Sample time courses (bottom trace) from the control cell (○, grey line) and RGS2-expressing cell (•) were compared following application and removal of 10 μM ACh. ACh was applied for 15 s and then washed out with external Ca2+ solution as described in the Methods. Currents were recorded with 10 mM Ba2+ as the current carrier through P/Q-type Ca2+ channels and were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV every second. B, time constants for M2 mAChR-mediated IBa inhibition are shown after ACh application in control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells. Time courses for IBa inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. C, time constants for recovery from M2 mAChR-mediated P/Q-type IBa inhibition are shown after ACh removal in control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells. Time courses for recovery from IBa inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrec) ± s.e.m. were plotted. D, percentage means (± s.e.m.) of inhibition of IBa by 10 μM ACh in control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells were plotted. Currents were normalized to the largest current inhibition after ACh application compared to currents before ACh application. In B-D, numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses; * P < 0·05, Student’s t test (see ‘Data analysis’ for explanation of significance tests in figures).

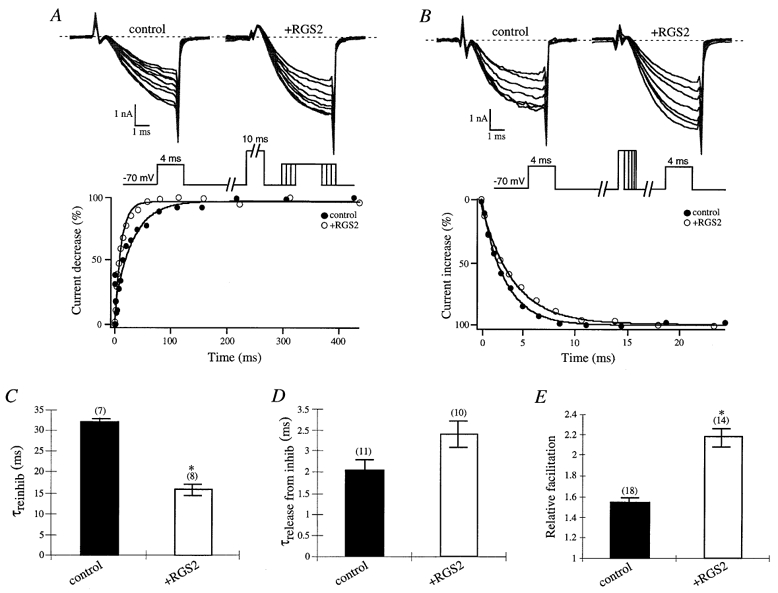

RGS2 increases the facilitation and accelerates the reinhibition of M2 mAChR-mediated inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

Transmitter-mediated inhibition of ion channels involves the activation of G proteins by a GPCR which presumably leads to the inhibition of channels by direct interaction with Gβγ. This inhibition can be reversed by removal of the transmitter (which leads to the reassociation of the Gαβγ heterotrimer and termination of the G protein signal) or also by application of a high depolarizing prepulse. The latter phenomenon, described as prepulse facilitation, is commonly explained as a short release of Gβγ from the channel which results in increased Ca2+ currents. Since the G protein is still active, reinhibition by Gβγ subunits occurs once the membrane is repolarized (for review see Dolphin, 1996; Jones & Elmslie, 1997; Zamponi & Snutch, 1998b).

The release of G protein inhibition and the reinhibition of IBa during application of 10 μM ACh were determined using a double-pulse voltage protocol first described by Elmslie et al. (1990). The protocol consists of two test pulses to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV separated by a high depolarization (prepulse) to +100 mV which relieves the channel from Gβγ inhibition. The time course of G protein reinhibition can be determined by increasing the time period (1–427 ms) between a 10 ms prepulse of +100 mV and the second test pulse which may lead to the reassociation of more Gβγ subunits over time (illustrated in Fig. 2A). The time course of release from G protein inhibition can be examined by varying the time (1–23 ms) of the +100 mV prepulse which results in an increase in Gβγ release from the channel over time (illustrated in Fig. 2B). Time courses obtained using the modified double-pulse voltage protocols were compared by plotting the change in peak currents after 3·9 ms (%) at +10 mV over time. The time course of reinhibition of IBa in the presence of 10 μM ACh and RGS2 was faster than the control cells (Fig. 2A). Mean time constants of reinhibition in the presence of RGS2 (15·94 ± 1·28 ms (n = 8)) and control (32·07 ± 0·95 ms (n = 7)) cells were obtained by fitting the time courses of reinhibition with a single exponential function (Fig. 2C). Differences in the time course of IBa release from ACh-induced inhibition were observed in cells expressing RGS proteins compared to controls using the modified double-pulse voltage protocol (where the time of the prepulse increases), but were not significant. Mean time constants of IBa release from ACh-induced inhibition were 2·03 ± 0·27 ms (n = 11) from control and 2·92 ± 0·30 ms (n = 10) from RGS protein-expressing cells. The relative facilitations were determined by dividing the peak currents from the last time point of the second test pulse by the first test pulse. RGS2 markedly increased the facilitation of ACh-induced IBa compared to control currents with relative facilitations of 2·18 ± 0·09 (n = 18) and 1·54 ± 0·04 (n = 14), respectively (Fig. 2E). These results show that in the presence of RGS2 transmitter-mediated reinhibition is accelerated and facilitation is increased for P/Q-type channels.

Figure 2.

Effects of RGS2 on facilitation properties of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels during transmitter application

A, time courses of IBa reinhibition during application of 10 μM ACh were determined by eliciting currents with a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a 10 ms conditioning prepulse to +100 mV was applied to relieve G protein inhibition, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 1–427 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Sample IBa traces illustrating the reinhibition P/Q-type Ca2+ channels during 10 μM ACh application in a control and RGS-expressing cell are shown in the upper panel from every other time point. Peak currents were normalized to the smallest peak current from the second test pulse, and reinhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at −70 mV between the prepulse and second test pulse. The lower panel shows the time courses of current decrease from a control (▪) and RGS-expressing (□) cell during 10 μM ACh application. B, time courses of IBa release from inhibition during application of 10 μM ACh were determined by eliciting currents by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a conditioning prepulse to +100 mV for a period of 1–23 ms was applied, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 10 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Sample IBa traces illustrating the release from G protein inhibition during application of ACh in a control and RGS-expressing cell are shown in the upper panel from every other time point. Peak currents were normalized to the largest peak current from the second test pulse, and release from inhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at +100 mV. The lower panel shows the time courses of current increase from a control (▪) and RGS-expressing (□) cell during application of ACh. C, time constants for M2 mAChR-mediated IBa reinhibition are shown during ACh application in control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells. Time courses of IBa reinhibition during 10 μM ACh application in control (▪) and RGS-expressing (□) cells were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τreinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. D, time constants for IBa release from M2 mAChR-mediated inhibition are shown during ACh application in control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells. Time courses of IBa release from M2 mAChR-mediated inhibition in control (▪) and RGS-expressing (□) cells were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrelease from inhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test. E, relative means (± s.e.m.) of facilitation were plotted from control (▪) and RGS2-expressing (□) cells. Currents were normalized to the largest peak current of the second test pulse versus the first test pulse from the traces in C and D. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test.

Facilitation and time course of reinhibition depend on the amount of activated G protein

Zamponi & Snutch (1998a, b) showed that reinhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels by Gβγ subunits occurs as a bimolecular reaction, where the time course and amount of inhibition are dependent on the concentration of Gβγ subunits applied to the channel (Zamponi & Snutch, 1998a). According to their results, activation of increasing amounts of endogenous G proteins in HEK293 cells should lead to a faster reinhibition and more facilitation. To test this hypothesis we used various ratios of GTP and GTPγS to activate different amounts of G proteins within the cell. GTPγS is a non-hydrolysable GTP analogue which exchanges for GDP on the Gα subunit; however, it cannot be hydrolysed to the inactive Gα-GDP form. Thereby more Gβγ dimer is available for G protein modulation. We examined the G protein modulation of P/Q-type channels under three conditions, 0·6 mM GTPγS, 0·3 mM GTPγS plus 0·3 mM GTP and 0·6 mM GTP in the intracellular solution using the modified double-pulse voltage protocols. The reinhibition of IBa was accelerated and facilitation was enhanced with increasing concentrations of GTPγS (i.e. higher levels of free Gβγ subunits) in intracellular solutions (Table 1), indicating that reinhibition and facilitation of IBa is dependent on the concentration of available G protein. No significant differences in the release of IBa from G protein inhibition were observed under the various GTPγS concentrations (Table 1). Our results verified that the amount of activated G proteins (i.e. available Gβγ subunits) accelerates the reinhibition of Ca2+ channels and increases the relative facilitation.

Table 1.

Effect of GTPγS on G protein modulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

| Various concentrations of GTPγS (final conc. of 0.6 mm) | τreinhib (ms) | τrelease from inhib (ms) | Relative facilitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GTP | 150.6 ± 39 (3) | 2.0 ± 0.12 (3) | 1.1 ± 0.02 (3) |

| GTP/GTPγS | 99.5 ± 2.4 (3) | 2.6 ± 0.45 (3) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (3) |

| GTPγS | 53.1 ± 7.8 (12) | 2.4 ± 0.3 (6) | 1.8 ± 0.09 (15) |

Values represent means ± s.e.m., with number of cells (n) in parentheses.

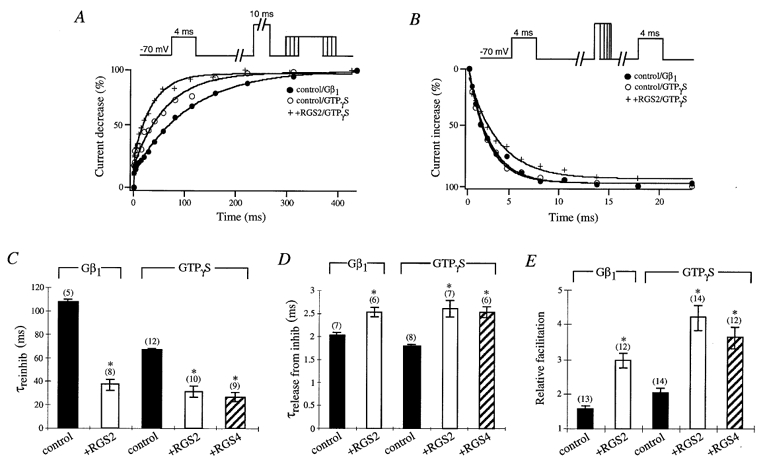

RGS proteins enhance facilitation, accelerate reinhibition and slow release of inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels when inhibited by overexpressed Gβ1 subunits or endogenous, GTPγS-activated G proteins

Since transmitter-mediated activation of G proteins revealed differences in prepulse facilitation properties of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels expressed with or without RGS proteins, we further analysed the effects of RGS proteins on the facilitation of P/Q-type channels when G proteins were activated intracellularly by overexpression of Gβ1 subunits or intracellular application of GTPγS in HEK293 cells. Both methods induce G protein modulation of P/Q-type channels (Herlitze et al. 1996) (Fig. 3). However, control cells expressing Gβ1 displayed a slower reinhibition and less facilitation of IBa compared to control cells with GTPγS in the intracellular solution, with a time constant of 106·89 ± 3·28 ms (n = 5) and 66·65 ± 2·02 ms (n = 12) for reinhibition, respectively (Fig. 3A and C). No significant differences for release from G protein inhibition could be observed between cells coexpressing Gβ1 (control/Gβ1, 2·01 ± 0·06 ms (n = 7)) and cells with GTPγS in the intracellular solution (control/GTPγS, 1·79 ± 0·06 ms (n = 8)) (Fig. 3B and D). The data indicate that in the presence of GTPγS more activated G proteins exist for channel modulation compared to overexpressed Gβ1 subunits.

Figure 3.

Effects of RGS2 and RGS4 on prepulse facilitation properties of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels during coexpression of Gβ1 subunit or activation of endogenous G proteins by GTPγS

A, sample time courses of reinhibition are shown with Gβ1 subunit (•) and GTPγS in the intracellular solution with (+) or without (○) RGS2. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a 10 ms conditioning prepulse to +100 mV was applied to completely relieve G protein inhibition, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 1–427 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the smallest peak current from the second test pulse, and reinhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at −70 mV between the prepulse and second test pulse. B, sample time courses of release from inhibition are shown with Gβ1 subunit (•) and GTPγS in the intracellular solution with (+) or without (○) RGS2. Currents were elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV. After 1 s a conditioning prepulse to +100 mV for a period of 1–23 ms was applied, the cell was repolarized to −70 mV for a period of 10 ms, and a second 4 ms test pulse to +10 mV was applied. Peak currents were normalized to the largest peak current from the second test pulse, and release from inhibition (%) was plotted versus the time interval at +100 mV. C, time constants for IBa reinhibition from control (▪), RGS2- (□) and RGS4-expressing ( ) cells are shown with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Time courses of IBa reinhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τreinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test. D, time constants for IBa release from inhibition from control cells (▪), and RGS2- (□) and RGS4-expressing (

) cells are shown with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Time courses of IBa reinhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τreinhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test. D, time constants for IBa release from inhibition from control cells (▪), and RGS2- (□) and RGS4-expressing ( ) cells, are shown with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Time courses of IBa release from inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrelease from inhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test. E, relative means (± s.e.m.) of facilitation were determined from control cells (▪), and RGS2- (□) and RGS4-expressing (

) cells, are shown with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Time courses of IBa release from inhibition were fitted with a single exponential, and mean time constants (τrelease from inhib) ± s.e.m. were plotted. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test. E, relative means (± s.e.m.) of facilitation were determined from control cells (▪), and RGS2- (□) and RGS4-expressing ( ) cells, with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Currents were normalized to the largest peak current of the second test pulse versus the first test pulse from the traces in C and D. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test.

) cells, with Gβ1 subunit or GTPγS in the intracellular solution as indicated. Currents were normalized to the largest peak current of the second test pulse versus the first test pulse from the traces in C and D. Numbers of cells tested are indicated in parentheses. * P < 0·05, Student’s t test.

In contrast, cells expressing RGS2 showed a faster reinhibition of IBa (+RGS2/GTPγS, 31·33 ± 4·08 ms (n = 10)), a slower release of inhibition (+RGS2/GTPγS, 2·60 ± 0·18 ms (n = 7)) and more facilitation (+RGS2/GTPγS, 4·22 ± 0·35 (n = 14)) compared to control cells not expressing RGS2, regardless of whether calcium channels were inhibited by endogenous G proteins (activated with GTPγS) or by overexpressed Gβ1 subunits. The data suggest that RGS2 proteins contribute to increasing the levels of free Gβγ in the cell. These results could be verified for a different member of the RGS protein family, RGS4. Similar to RGS2, coexpression of RGS4 led to a faster reinhibition (25·77 ± 3·34 ms (n = 9)), slower release from inhibition (2·53 ± 0·10 ms (n = 6)) and more facilitation (3·64 ± 0·31 (n = 12)) compared to Ca2+ channels not coexpressed with RGS proteins, indicating that these effects are not specific to one RGS protein family member.

Release from G protein inhibition is accelerated by overexpression of Gαi1 subunits in the presence of GTPγS and RGS2 for the Ca2+ channel α1A/QQIEE mutant

Our data indicate that the reinhibition and facilitation of IBa through P/Q-type channels are dependent on the amount of available Gβγ subunits in the cell. However, the release from G protein inhibition does not seem to be directly correlated to the level of free Gβγ subunits in the cell. In fact the recovery from G protein inhibition slightly slowed in the presence of RGS proteins and GTPγS, possibly due to decreases in inactive Gαi-GDP available to bind Gβγ and terminate inhibition or by rebinding of excessive Gβγ to the channel. To examine whether the release from inhibition is slower in the presence of RGS2, we used a Ca2+ channel α1A mutant which exhibits slow release kinetics from G protein inhibition (Herlitze et al. 1997; and Fig. 4D) and analysed the properties of this mutant in the presence and absence of overexpressed Gαi1 subunits.

The QXXER motif has been previously described as a Gβγ binding motif for various proteins, including adenylyl cyclase II, IRK channels, phopholipase Cβ, Na+ channels and Ca2+ channel α1 subunits (Chen et al. 1995; De Waard et al. 1997; Herlitze et al. 1997; Ma et al. 1997; Zamponi et al. 1997). The point mutation R to E at the last position of the QXXER motif in the α1A subunit (Fig. 4F) has dramatic effects on inactivation and G protein modulation of recombinant P/Q-type channels heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the reinhibition of the mutant channel was faster, the release from inhibition was slower (QQIER, 1·79 ± 0·06 ms (n = 8); QQIEE, 4·37 ± 0·29 ms (n = 10)) and the relative facilitation was increased compared to the wild-type channels, suggesting that the affinity for Gβγ subunit binding is higher for the mutant. In the presence of RGS2 the reinhibition of mutant channels was accelerated further, relative facilitation was increased, and most importantly the release from G protein inhibition was significantly slower (6·46 ± 0·19 ms (n = 15)) compared to mutant channels expressed without RGS2 (4·37 ± 0·29 ms (n = 10)), indicating that indeed overexpressed RGS proteins lead to a slowing of release from G protein inhibition.

To analyse what influence the available Gαi concentration has on the kinetics of release from G protein inhibition in the presence of RGS proteins, we overexpressed Gαi1 subunits together with the mutant Ca2+ channel. Overexpression of Gαi1 subunits slowed reinhibition and reduced the relative facilitation regardless of whether mutant channels were expressed with or without RGS2 (Fig. 4B and E). In agreement with our hypothesis, more available Gαi1 subunits can bind free Gβγ dimers and thereby reduce the concentration of Gβγ for channel modulation. In contrast the release from G protein inhibition was only significantly altered in the presence of RGS proteins (+RGS2/-Gαi1, 6·46 ± 0·19 ms (n = 15); +RGS2/+Gαi1, 3·05 ± 0·28 ms (n = 9); Fig. 4D) but was not changed in the absence of RGS2. These results indicate that the concentration of Gα subunits can influence the release of P/Q-type channels from G protein inhibition in the presence of RGS proteins but not their absence

RGS2 unmasks differences in G protein modulation of P/Q-type channels by coassembly with different Ca2+ channel β subunits

Since Ca2+ channel β subunits and Gβγ dimers interact at the same domain on the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit (for review see Zamponi & Snutch, 1998b; Dolphin et al. 1999; Ikeda & Dunlap, 1999), it was of particular interest to analyse how RGS2 influences the prepulse facilitation properties of Ca2+ channels when coexpressed with different Ca2+ channel β subunits. To date, four Ca2+ channel β subunits have been identified in the CNS, β1–4. These cytosolic proteins bind the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit on the C-terminus and intracellular linker between domains I and II which overlaps with the Gβγ QXXER binding motif (Fig. 4F). As expected all four Ca2+ channel β subunits tested, β1b, β2a, β3 and β4, exhibited significantly faster reinhibition, slower release from inhibition and stronger facilitation of IBa in the presence of RGS2 and Gβ1 subunits compared to controls not expressing RGS2 (Fig. 5). However, in the presence of RGS2 and Ca2+ channel β2a and β3 subunits, these effects are more pronounced compared to Ca2+ channels assembled with β1b or β4 subunits. For example, reinhibition was more accelerated (β2a, 11·44 ± 1·42 ms (n = 9); β3, 14·97 ± 3·27 ms (n = 7); β1b, 37·06 ± 4·55 ms (n = 8); β4, 33·90 ± 2·56 ms (n = 7)), release from inhibition was slower (β2a, 6·29 ± 0·43 ms (n = 10); β3, 3·90 ± 0·26 ms (n = 8); β1b, 2·55 ± 0·10 ms (n = 6); β4, 2·28 ± 0·12 ms (n = 8)) and relative facilitations were higher for channels assembled with β2a and β3 compared to β1b and β4. These data indicate that Ca2+ channel β subunits influence the kinetics of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel G protein modulation.

DISCUSSION

GPCR-mediated inhibition and release from inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels is accelerated by RGS proteins

GPCR-mediated modulation of ion channels has been studied extensively for the GIRK and presynaptic Ca2+ channels of the N- and P/Q-type (for review see Hille, 1994; Dascal, 1997; Schneider et al. 1997). The effect of RGS proteins on G protein modulation via a GPCR was first shown for GIRK channels and later for N-type channels for both recombinant and native channel types (Doupnik et al. 1997; Saitoh et al. 1997; Bünemann & Hosey, 1998; Jeong & Ikeda, 1998; Diverse-Pierluissi et al. 1999; Melliti et al. 1999). We demonstrate in this study that the ACh-mediated modulation of recombinant P/Q-type channels encoded by the α1A, β and α2δ subunits is also influenced by RGS2. RGS protein effects on transmitter-mediated modulation of all three channel types are quite similar. The transmitter-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ channels or the activation of GIRK channels as well as the recovery from inhibition of Ca2+ channels or deactivation of GIRK channels after transmitter washout are accelerated. The acceleration of recovery from inhibition or deactivation is commonly explained by the increased GAP activity of Gα subunits mediated by RGS proteins which speed up the termination of the G protein signal (Zerangue & Jan, 1998). The acceleration of transmitter-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ channels, as well as the activation of GIRK channels, is not completely understood but can be explained by the increased concentration of available G protein trimer (Gαβγ) for activation by the GPCR (Chuang et al. 1998; Zerangue & Jan 1998; Herlitze et al. 1999). The recombinant P/Q-type channel also exhibited a twofold acceleration in inhibition and release from inhibition via the M2 mAChR in the presence of RGS proteins. These results demonstrate that RGS proteins speed up transmitter action on P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

Overexpressed RGS proteins cause a larger population of activated G proteins to be available for P/Q-type channel modulation within HEK293 cells

G protein inhibition of Ca2+ channels can be reversed by high depolarizing prepulses, a phenomenon known as prepulse facilitation. Prepulse facilitation can be described as a process where Gβγ subunits are released for a short time period from the channel and then rebind again (Lopez & Brown, 1991; Boland & Bean, 1993; Golard & Siegelbaum, 1993; Elmslie & Jones, 1994; Zamponi & Snutch, 1998a). The time course of release and reassociation of Gβγ subunits are characteristic time constants for different G protein-modulated Ca2+ channel types (Dolphin, 1996). The rebinding or reinhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels could be described as a bimolecular reaction, which depends on the concentration of available Gβγ subunits within the cell. Therefore, the faster the reinhibition for one particular channel type, the more Gβγ subunits should be available within the cell for channel modulation. We verified this hypothesis for the P/Q-type channel expressed in HEK293 cells by using different molar ratios of GTP/GTPγS to activate different amounts of G proteins. High intracellular concentrations of GTPγS, which activate more G proteins, speed up reinhibition of Ca2+ channels, indicating that the time constant of reinhibition depends on the concentration of activated G protein. Reinhibition was accelerated for channels expressed with RGS regardless of whether the G protein action was achieved by activating a GPCR, an overexpressed Gβ1 subunit or endogenous G proteins activated by GTPγS. These results indicate that in HEK293 cells RGS2 as well as RGS4 increase the amount of activated G proteins available for channel modulation. Similar results could be obtained by Bünemann & Hosey (1998). They described how RGS proteins overexpressed in HEK293 cells increased basal GIRK currents and induced facilitation for N-type channels. In addition Chuang et al. (1998) reported that RGS4 increased the amplitude of GTPγS-induced GIRK currents, indicating that RGS causes a larger population of G proteins to be available for channel activation. The increase in available G proteins is a probable explanation for the observation that RGS proteins speed up G protein signalling without affecting the steady-state amplitude of a GPCR-mediated signal (Chuang et al. 1998; Herlitze et al. 1999). Surprisingly, opposite results were observed by Melliti et al. (1999) for RGS3T on N-type channel modulation in HEK293 cells. Here, the observed decreases in facilitation and slowing of reinhibition in the presence of RGS can be explained by a decrease in the Gβγ concentration. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the use of different RGS proteins or different expression levels of RGS relative to channel within the cell (Herlitze et al. 1999).

RGS proteins reveal changes in the release of G protein inhibition of P/Q-type channels

The overexpression of RGS led to a speeding up of reinhibition of Ca2+ channels, probably by increasing the available Gβγ subunit concentration. The effects observed on reinhibition are consistent with a bimolecular binding reaction between channel and Gβγ, as already suggested by Zamponi & Snutch (1998a, b). According to this binding reaction the release of Gβγ subunits from the channel should only depend on the strength of the interaction between both binding partners. The overexpression of Gαi1 in the absence of RGS proteins does not change the release kinetics of Gβγ from the channel. However, in the presence of RGS, G protein release was slower and could be accelerated by overexpressed Gαi1 subunits. There are two possibilities to explain these differences in release kinetics. The first possibility is a rebinding of Gβγ subunits during the release of inhibition. Rebinding of Gβγ to the channel during the release process may only be observed at high Gβγ concentrations and can be reduced by overexpressing Gαi subunits. Since RGS proteins increase the availability of Gβγ subunits within the cell, effects on the speed of release from inhibition are only obvious in the presence of RGS. A second possibility is that an additional protein (i.e. Gα-GDP) influences the interaction between Gβγ and the channel. RGS proteins accelerate the rate of GTP hydrolysis on Gαi subunits, which leads to a faster transition from Gα-GTP to Gα-GDP. Gα-GDP has a high binding affinity for Gβγ and may weaken the stability between Gβγ and the Ca2+ channel. High concentrations of Gα-GDP lead then to a fast release of Gβγ from the channel, while low concentrations of Gα-GDP result in a slow release from G protein inhibition.

β subunits of Ca2+ channels modulate G protein inhibition of P/Q-type channels

The β subunits of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels modulate the electrophysiological properties and cell surface expression of the pore-forming α1 subunits (Birnbaumer et al. 1998). Variations in the electrophysiological characteristics caused by different β subunits coexpressed with one α1 subunit have been observed, particularly for the activation and inactivation properties of the channel. Moreover, in the absence of β subunits G protein modulation of Ca2+ channels is increased (Campbell et al. 1995; Roche et al. 1995; Bourinet et al. 1996) and might depend on the α1 and β subunit composition of the channel complex (Qin et al. 1998). For example, N-type channels encoded by the α1B subunit reveal a higher voltage dependence of receptor-mediated inhibition and release from inhibition by high positive prepulses when expressed with the β3 subunit in Xenopus oocytes compared to channels expressed without the auxiliary subunit. In addition, coassembly of the channel with β subunits leads to a faster release from G protein inhibition (Roche & Treistman, 1998). Here, we describe how RGS proteins unmask effects of Ca2+ channel β subunits on the release and recovery of G protein inhibition of P/Q-type channels. Roche & Treistman (1998) suggest that β subunits enhance the rate of dissociation of Gβγ subunits from the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit. Since Ca2+ channel β subunits and Gβγ subunits have overlapping binding sites on the α1 subunit, the competition for a common binding site may be a likely mechanism for G protein modulation (De Waard et al. 1997; Zamponi et al. 1997). Our results suggest that either different Ca2+ channel β subunits allow different association of Gβγ with the P/Q-type channel or that G protein modulation depends on the concentration of expressed Ca2+ channel β subunits relative to Gβγ and the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit. In our study we describe increased facilitation and slow release kinetics for P/Q-type channels containing the β2a and β3 subunits. These results are in contrast with the transmitter-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ channels encoded by α1E and β subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Qin et al. 1998). Here β2a-assembled channels do not show Ca2+ channel inhibition during transmitter application. The use of the different expression systems and different α1 subunits in combination with β subunits may indicate that, besides the specific subunit composition of the channel, the cellular surroundings may have additional effects on G protein modulation of Ca2+ channel complexes.

In conclusion we showed that the fast kinetics of G protein inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels involve RGS proteins. The kinetics of G protein modulation of P/Q-type channels depend on the concentration of available G protein subunits. RGS proteins significantly accelerate the shutting on and off of P/Q-type channels, which may play a critical role in rapid synaptic transmission. Furthermore, Ca2+ channel β subunits coassembled with the P/Q-type channel exhibited different kinetics of G protein modulation. The β2a and β3 subunits exhibited faster inhibition and more facilitation than β1b or β4, indicating that Ca2+ channel β subunits influence the interaction with Gβγ subunits on the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Waka and B. Rudo for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Drs T. P. Snutch, K. P. Campbell, R. R. Reed, E. Perez-Reyes, M. I. Simon and W. A. Catterall for cDNAs and Dr J. P. Ruppersberg for general support. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft project number He2471/5-1.

References

- Berman DM, Gilman AG. Mammalian RGS proteins: barbarians at the gate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:1269–1272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaumer L, Qin N, Olcese R, Tareilus E, Platano D, Costantin J, Stefani E. Structures and functions of calcium channel β subunits. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1998;30:357–375. doi: 10.1023/a:1021989622656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland LM, Bean BP. Modulation of N-type calcium channels in bullfrog sympathetic neurons by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone: kinetics and voltage dependence. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:516–533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00516.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Soong TW, Stea A, Snutch TP. Determinants of the G protein-dependent opioid modulation of neuronal calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:1486–1491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünemann M, Hosey MM. Regulators of G protein signalling (RGS) proteins constitutively activate Gβγ-gated potassium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:31186–31190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell V, Berrow NS, Fitzgerald EM, Brickley K, Dolphin AC. Inhibition of the interaction of G protein G(o) with calcium channels by the calcium channel β-subunit in rat neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:365–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a neuronal calcium channel β subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993a;268:12359–12366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a third calcium channel β subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993b;268:3450–3455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, DeVivo M, Dingus J, Harry A, Li J, Sui J, Carty DJ, Blank JL, Exton JH, Stoffel RH, Inglese J, Lefkowitz RJ, Logothetis DE, Hildebrandt JD, Iyengar R. A region of adenylyl cyclase 2 critical for regulation by G protein βγ subunits. Science. 1995;268:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7761832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H-H, Yu M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Evidence that the nucleotide exchange and hydrolysis cycle of G proteins causes acute desensitization of G-protein gated inward rectifier K+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:11727–11732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N. Signaling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cellular Signalling. 1997;9:551–573. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Liu H, Walker D, Scott VE, Gurnett CA, Campbell KP. Direct binding of G-protein βγ complex to voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1997;385:446–450. doi: 10.1038/385446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diverse-Pierluissi MA, Fischer T, Jordan JD, Schiff M, Ortiz DF, Farquhar MG, De Vries L. Regulators of G protein signalling proteins as determinants of the rate of desensitization of presynaptic calcium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:14490–14494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman HG, Thorner J. RGS proteins and signalling by heterotrimeric G proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:3871–3874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Facilitation of Ca2+ current in excitable cells. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC, Page KM, Berrow NS, Stephens GJ, Canti C. Dissection of the calcium channel domains responsible for modulation of neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels by G proteins. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:160–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik CA, Davidson N, Lester HA, Kofuji P. RGS proteins reconstitute the rapid gating kinetics of Gβγ-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:10461–10466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis SB, Williams ME, Ways NR, Brenner R, Sharp AH, Leung AT, Campbell KP, McKenna E, Koch WJ, Hui A, Schwartz A, Harpold MM. Sequence and expression of mRNAs encoding the α1 and α2 subunits of a DHP-sensitive calcium channel. Science. 1988;241:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.2458626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS, Jones SW. Concentration dependence of neurotransmitter effects on calcium current kinetics in frog sympathetic neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;481:35–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS, Zhou W, Jones SW. LHRH and GTP-γ-S modify calcium current activation in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1990;5:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90035-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong HK, Hurley JB, Hopkins RS, Miake-Lye R, Johnson MS, Doolittle RF, Simon MI. Repetitive segmental structure of the transducin β subunit: homology with the CDC4 gene and identification of related mRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1986;83:2162–2166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golard A, Siegelbaum SA. Kinetic basis for the voltage-dependent inhibition of N-type calcium current by somatostatin and norepinephrine in chick sympathetic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:3884–3894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03884.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm HE. The many faces of G protein signalling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:669–672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Hockerman GH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of inactivation and G protein modulation in the intracellular loop connecting domains I and II of the calcium channel α1A subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1512–1516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Ruppersberg JP, Mark MD. New roles for RGS2, 5 and 8 on the ratio-dependent modulation of recombinant GIRKs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0341t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Modulation of ion-channel function by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR, Dunlap K. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels: role of G protein subunits. Advances in Second Messenger and Phosphoprotein Research. 1999;33:131–151. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SW, Ikeda SR. G protein α subunit Gαz couples neurotransmitter receptors to ion channels in sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1998;21:1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80636-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Reed RR. Molecular cloning of five GTP-binding protein cDNA species from rat olfactory neuroepithelium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:14241–14249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SW, Elmslie KS. Transmitter modulation of neuronal calcium channels. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;155:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s002329900153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle MR. A new family of G-protein regulators – the RGS proteins. Current Biology. 1997;9:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez HS, Brown AM. Correlation between G protein activation and reblocking kinetics of Ca2+ channel currents in rat sensory neurons. Neuron. 1991;7:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JY, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Persistent sodium currents through brain sodium channels induced by G protein βγ subunits. Neuron. 1997;19:443–452. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melliti K, Meza U, Fisher R, Adams B. Regulators of G protein signalling attenuate the G protein-mediated inhibition of N-type Ca channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:97–110. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer EJ. Intracellular signalling: turning down G-protein signals. Current Biology. 1997;7:R31–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page KM, Stephens GJ, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC. The intracellular loop between domains I and II of the B-type calcium channel confers aspects of G-protein sensitivity to the E-type calcium channel. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:1330–1338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei XY, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain β subunit of the L-type calcium channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Platano D, Olcese R, Costantin JL, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Unique regulatory properties of the type 2a Ca2+ channel β subunit caused by palmitoylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:4690–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Platano D, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Direct interaction of Gβγ with a C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit is responsible for channel inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:8866–8871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche JP, Anantharam V, Treistman SN. Abolition of G protein inhibition of α1A and α1B calcium channels by co-expression of the β3 subunit. FEBS Letters. 1995;371:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00860-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche JP, Treistman SN. Ca2+ channel β3 subunit enhances voltage-dependent relief of G-protein inhibition induced by muscarinic receptor activation and Gβγ. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:4883–4890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04883.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh O, Kubo Y, Miyatani Y, Asano T, Nakata H. RGS8 accelerates G-protein-mediated modulation of K+ currents. Nature. 1997;390:525–529. doi: 10.1038/37385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Igelmund P, Hescheler J. G protein interaction with K+ and Ca2+ channels. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1997;18:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siderovski DP, Hessel A, Chung S, Mak TW, Tyers M. A new family of regulators of G-protein-coupled receptors. Current Biology. 1996;6:211–212. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr TV, Prystay W, Snutch TP. Primary structure of a calcium channel that is highly expressed in the rat cerebellum. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:5621–5625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Dubel SJ, Pragnell M, Leonard JP, Campbell KP, Snutch TP. A β-subunit normalizes the electrophysiological properties of a cloned N-type Ca2+ channel α1-subunit. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Bourinet E, Nelson D, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Crosstalk between G proteins and protein kinase C mediated by the calcium channel α1 subunit. Nature. 1997;385:442–446. doi: 10.1038/385442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Snutch TP. Decay of prepulse facilitation of N type calcium channels during G protein inhibition is consistent with binding of a single Gβ subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998a;95:4035–4939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Snutch TP. Modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G proteins. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1998b;8:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Jan LY. G-protein signalling: fine-tuning signalling kinetics. Current Biology. 1998;8:R313–316. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]