Abstract

Mammalian neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels have been implicated as potential mediators of membrane permeability to Zn2+. We tested directly whether voltage-gated Ca2+ channels can flux Zn2+ in whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from cultured murine cortical neurones.

In the presence of extracellular Zn2+ and no Na+, K+, or other divalent cations, a small, non-inactivating, voltage-gated inward current was observed exhibiting a current-voltage relationship characteristic of high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels. Inward current was detectable at Zn2+ levels as low as 50 μm, and both the amplitude and voltage sensitivity of the current depended upon Zn2+ concentration. This Zn2+ current was sensitive to blockade by Gd3+ and nimodipine and, to a lesser extent, by ω-conotoxin GVIA.

Zn2+ could permeate Ca2+ channels in the presence of Ca2+ and other physiological cations. Inward currents recorded with 2 mm Ca2+ were attenuated by Zn2+ (IC50 = 210 μm), and currents recorded with Zn2+ were unaffected by up to equimolar Ca2+ concentrations. Furthermore, the Zn2+-selective fluorescent dye Newport Green revealed a depolarisation-activated, nimodipine-sensitive Zn2+ influx into cortical neurones that were bathed in a physiological extracellular solution plus 300 μm ZnCl2.

Surprisingly, while lowering extracellular pH suppressed HVA Ca2+ currents, Zn2+ current amplitude was affected oppositely, varying inversely with pH with an apparent pK of 7·4. The acidity-induced enhancement of Zn2+ current was associated with a positive shift in reversal potential but no change in the kinetics or voltage sensitivity of channel activation.

These results provide evidence that L- and N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels can mediate Zn2+ entry into cortical neurones and that this entry may be enhanced by extracellular acidity.

Zinc is concentrated in the synaptic vesicles of central excitatory nerve terminals (Perez-Clausell & Danscher, 1985) and is released upon synaptic activation (Assaf & Chung, 1984; Howell et al. 1984). The total concentration of Zn2+ in the hippocampus and cortical grey matter has been estimated at 220–300 μm (Frederickson, 1989), and peak concentrations of synaptically released Zn2+ may reach hundreds of micromolar in hippocampal slices (Assaf & Chung, 1984; Vogt et al. 2000) – concentrations more than sufficient for Zn2+ to exhibit profound modulatory effects on a variety of agonist- and voltage-gated mammalian ion channels, including attenuation of current through NMDA and GABA receptor-gated channels, potentiation of AMPA, glycine, and ATP receptor-mediated currents, modulation of the transient outward K+ current IA, and blockade of voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels (Harrison & Gibbons, 1994; Smart et al. 1994).

Excessive exposure to extracellular Zn2+ can also be toxic to neurones (Yokoyama et al. 1986), inducing apoptosis at lower concentrations (Manev et al. 1997; Lobner et al. 2000) and necrosis at higher concentrations (Choi et al. 1988; Lobner et al. 2000). Zn2+ neurotoxicity has been implicated in the pathogenesis of selective neuronal death following transient global cerebral ischaemia and prolonged seizures (Choi & Koh, 1998). A critical step in Zn2+-induced neuronal death appears to be its permeation across the plasma membrane (Tønder et al. 1990; Weiss et al. 1993; Koh et al. 1996). Raising extracellular Ca2+ reduces Zn2+ neurotoxicity (Weiss et al. 1993; Koh & Choi, 1994), suggesting that routes implicated in membrane permeability to Ca2+ may also mediate Zn2+ flux (Choi & Koh, 1998). Putative routes of neuronal Zn2+ entry include Ca2+-permeable AMPA (Yin & Weiss, 1995; Sensi et al. 1997) and NMDA (Christine & Choi, 1990; Koh & Choi, 1994) receptor-gated channels, as well as transporter-mediated exchange with intracellular Na+ (Sensi et al. 1997). An especially prominent route of toxic Zn2+ entry may be voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, as neuronal depolarisation enhanced both Zn2+ influx and resultant neuronal death, and Ca2+ channel antagonists attenuated both indices (Weiss et al. 1993; Freund & Reddig, 1994; Manev et al. 1997).

Zn2+ is a potent antagonist of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in invertebrates (Hagiwara & Takahashi, 1967) and mammals (Winegar & Lansman, 1990; Büsselberg et al. 1992). There is also clear evidence that Zn2+ can permeate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in invertebrates: in the absence of Ca2+, Zn2+ can support full Ca2+ channel-mediated action potentials in insect muscle membranes (Fukuda & Kawa, 1977) and snail neurones (Kawa, 1979). In addition, nanoampere-sized whole-cell Zn2+ currents through verapamil- and Co2+-sensitive channels have been characterised in Helix neurones (Oyama et al. 1982). However, the evidence for Zn2+ permeation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in mammals has so far been only indirect. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel antagonists, including dihydropyridine compounds and ω-conotoxin GVIA in particular, attenuated depolarisation-induced intracellular Zn2+ accumulation as measured by transcription of a reporter gene coupled to a Zn2+-activated metallothionein promoter in pituitary tumour cells (Atar et al. 1995), fluorescence of a Zn2+-sensitive dye loaded into living cortical neurones (Sensi et al. 1997), and cortical neuronal uptake of 65Zn2+ (H. Ying and D. W. Choi, unpublished observations), suggesting that Zn2+ may permeate L- and N-type HVA Ca2+ channels. Although two reports exist of small (< 50 pA) inward whole-cell currents recorded in the presence of extracellular Zn2+ in bovine chromaffin cells (Vega et al. 1994) and rat ventricular myocytes (Atar et al. 1995), neither study directly implicated Zn2+ as the charge carrier or provided any characterisation of the currents observed. In this study, we sought to test whether cortical neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels flux Zn2+. We showed that Zn2+ could indeed permeate these channels and, in addition, that it could do so in the ionic conditions normally encountered in the brain. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that extracellular acidity enhanced the permeation of Zn2+ relative to Ca2+ through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. An abstract based on these results has appeared (Kerchner et al. 1998).

METHODS

Murine cortical cell cultures

Mixed cortical cultures, containing both neurones and glia, were prepared from embryonic day 15 mice as described previously (Rose et al. 1993). Embryos were harvested acutely from pregnant female mice killed under halothane anaesthesia by cervical dislocation. Embryos were decapitated, and neocortices were dissected, dissociated, and plated in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM, Earle's salts) supplemented with 20 mm glucose (final concentration 25 mm), 2 mm glutamine, 5 % fetal bovine serum, and 5 % horse serum at a density of 0·4 hemispheres per dish onto 35 mm culture dishes (Becton Dickinson and Company, Plymouth, UK), which were prepared by incubation overnight with 1 mg ml−1 poly-D-lysine (Sigma Chemical Co.) and 20 μg ml−1 laminin (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA, USA) and subsequent rinsing with water. The medium was changed after 9 days in vitro (DIV 9) to MEM containing 25 mm glucose and 2 mm glutamine. Cultures were maintained in a 37°C, humidified incubator in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. All experiments were performed between DIV 14 and 17. Protocols for the handling of experimental animals were approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine, in accordance with local and national ethical guidelines.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed on cultured murine cortical neurones in 35 mm dishes on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan) using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc.). Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (World Precision Instruments) using a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co.) and fire polished to a final tip resistance of 7–12 MΩ when filled with the internal pipette solution (Table 1). Capacitance neutralisation and series resistance compensation were routinely applied, and input resistance was typically ∼400–500 MΩ in the standard external solution (Table 1). Current was digitally sampled at 20 kHz and filtered by a 5 kHz, 4-pole low-pass Bessel filter. Current traces were displayed and stored on an IBM PC-compatible computer (Comtrade Express) using the A/D converter interface Digidata 1200 and the data acquisition/analysis software package pCLAMP 6.0 (Axon Instruments Inc.). Leak subtraction was performed by pCLAMP by delivering two negative-going voltage pulses, each half the height of the test pulse, from a holding potential of −90 mV, before delivery of each depolarising test pulse from −70 mV. All experiments were performed at room temperature (21–22°C). Data are reported as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Table 1.

Composition of electrophysiological recording solutions (concentrations in mm except as indicated)

| Solute | Internal (all expts) | External | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expts at constant pH | Expts at varying pH | ||

| NMDG | — | 122 | 120 |

| ZnCl2 or CaCl2 | — | As indicated | As indicated |

| TEA-Cl | 130 | 20 | 20 |

| Hepes | 10 | 5 | — |

| Hepes or Pipes | — | — | 10 |

| Glucose | — | 10 | 10 |

| MgCl2 | 3 | — | — |

| BAPTA | 2.5 | — | — |

| Na2-ATP | 5 | — | — |

| Li-GTP | 0.3 | — | — |

| TTX | — | 200 nm | 200 nm |

| HCl | — | To pH 7.4 | To indicated pH |

| TEA-OH | To pH 7.4 | — | — |

Abbreviations: NMDG, N-methyl-d-glucamine; TEA-Cl, tetraethylammonium chloride; Hepes, N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid); Pipes, piperazine-N,N′-bis (2-ethanesulfonic acid); BAPTA, 1,2-bis (2-aminophenoxy) -ethane-NN,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; TTX, tetrodotoxin.

Solution preparation and delivery

The contents of the standard external bath and internal pipette solutions are itemised in Table 1. To aid in the formation of a tight electrical seal between the glass pipette and the neuronal membrane, cells were initially bathed in standard external solution supplemented with 2 mm MgCl2. During recordings, a neurone was bathed in a control solution with no divalent cations, one supplemented with CaCl2 or ZnCl2, or one supplemented both with ZnCl2 and a pharmacological agent. In each case, solutions were delivered directly to the tested neurone by continuous perfusion with a gravity-fed delivery pipette of approximately 300 μm internal diameter. Solution changes occurred at a cell in less than 100 ms.

Current-voltage curve fits

In Figs 4 and 9, current-voltage relations were fitted with curves to allow determination and comparison of the voltage sensitivity of channel activation in different conditions. At some voltage V:

where I is the magnitude of current measured in relative units, Po is the proportion of channels open at V, Vrev is the reversal potential of the current, and g is proportional to membrane conductance when channels are fully activated. Po is described by the Boltzmann relation:

where Vh is the voltage of half-maximal channel activation, and m is a slope factor. These equations apply whether I represents the contribution of a single ion (e.g. Zn2+) flowing into a cell or the net current resulting from multiple conductances (e.g. Zn2+ flowing into and Na+ flowing out of a cell); in the latter case, g would represent the sum of conductances, and Vrev would represent the net reversal potential of the current, an average of the Vrev values for each ion weighted by the relative contribution of each ion's conductance to the total membrane conductance. Curves were fitted by least-squares regression.

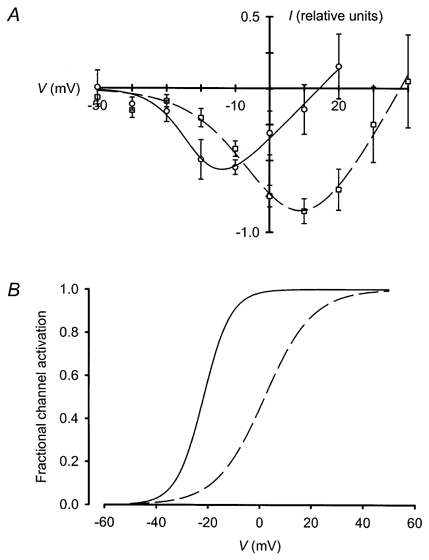

Figure 4.

Zn2+ concentration affected both maximal current amplitude and voltage sensitivity

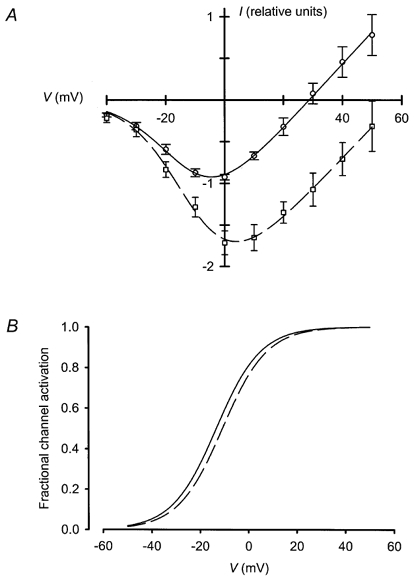

Figure 9.

Extracellular acidity enhanced Zn2+ current amplitude with no effect on voltage sensitivity

A, the I–V relationships of currents recorded in the presence of 500 μm Zn2+ at pHo 7·4 (○-○) and pHo 6·4 (□ – – □) were plotted. Twelve cells were tested, each at both pHo values, and I–V curves for each cell were normalised to the peak inward steady-state current at pHo 7·4. Points represent means ± s.e.m., and curves were fitted as in Fig. 4. At pHo 7·4, Vh = −13 mV, m = 9·2, Vrev = 29 mV, and g = 0·038; at pHo 6·4, Vh = −11 mV, m = 9·3, Vrev = 59 mV, and g = 0·037. B, decreasing pHo from 7·4 (continuous line) to 6·4 (dashed line) resulted in little to no shift of the voltage sensitivity of channel activation. Curves were plotted as in Fig. 4.

Fluorescence detection of intracellular Zn2+

The intracellular Zn2+ concentration ([Zn2+]i) was assessed using Newport Green as previously described (Canzoniero et al. 1999). Cell cultures were first washed with a Hepes-buffered physiological saline solution containing (mm): NaCl 120, KCl 5·4, MgCl2 0·8, Hepes 20, glucose 15, CaCl2 1·8, NaOH 10 (pH 7·4). Cells were then loaded with 5 μm Newport Green diacetate (excitation wavelength (λ), 485 nm; emission λ, 530 nm; Molecular Probes) in the presence of 0·02 % Pluronic F-127 for 30 min at room temperature. Neurones were washed and incubated for an additional 30 min in the Hepes-buffered saline. Before each experiment, cultures were washed twice with the same solution.

All experiments were performed at room temperature under constant perfusion (2 ml min−1) on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope equipped with a 75 W xenon lamp and a Nikon × 40, 1·3 NA epifluorescence oil immersion objective lens. Background fluorescence was subtracted at the beginning of each experiment. Images were acquired with a CCD camera (Quantex, CA, USA) and digitised using Metafluor 4.0 software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA, USA).

[Zn2+]i was calculated using in situ calibration at the end of each experiment. For each field of neurones, maximum (Fmax) and minimum (Fmin) fluorescence values were determined by exposure to 1 mm Zn2+plus 50 μm sodium pyrithione or to the heavy metal chelator N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN, 100 μm) in a Zn2+-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free medium, respectively. An assumed Kd of 1 μm (Haugland, 1996) was applied to the formula described by Grynkiewicz et al. (1985), which gives that for a fluorescence value F:

The experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Atomic zinc analysis

Samples (prepared according to Table 3) were transferred to a quartz beaker and treated with concentrated sulphuric acid. A sample was then repeatedly charred on a hot plate at 250°C and treated with nitric acid until the sample no longer charred, at which point the sample was resuspended in doubly deionised water. A determination of the zinc content of these samples was performed with an inductively-coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer, the Thermo Jarrell Ash IRIS Advantage Duo-View System (Thermo Jarrell Ash Corp., Franklin, MA, USA).

Table 3.

Atomic emission spectroscopic analysis of zinc recovered from experimental recording solutions in various conditions

| Nominal [Zn2+](μm) | pH | Exposure to cultures | Zinc recovered (p.p.m.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 7.4 | − | 28.8 |

| 500 | 6.4 | − | 29.5 |

| 0 | 7.4 | − | < 0.5 |

| 0 | 6.4 | − | < 0.5 |

| 500 | 7.4 | + | 28.0 |

| 500 | 6.4 | + | 29.1 |

| 0 | 7.4 | + | <0.5 |

| 0 | 6.4 | + | < 0.5 |

Extracellular recording solutions (Table 1) were prepared at the indicated pH and [Zn2+] and stored in the same polypropylene containers used to store solutions during electrophysiological experiments. Some solutions were washed through cortical neuronal cultures before storage.

Chemicals and pharmacological agents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. except ω-conotoxin GVIA which was from Bachem Biosciences Inc. (King of Prussia, PA, USA).

RESULTS

A voltage-gated current is observed in the presence of Zn2+

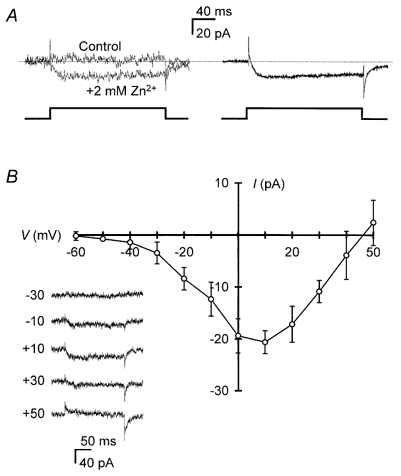

When extracellular Ca2+ is lowered below micromolar levels, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels become highly permeable to other divalent and monovalent ions including Na+ and K+ (Kostyuk et al. 1983; Almers & McCleskey, 1984). To isolate any Zn2+ permeation through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, voltage-clamp recordings of cultured cortical neurones were made using an internal solution containing TEA to block voltage-gated K+ channels and an external solution nominally devoid of any divalent cations, Na+ and K+ (Table 1) to eliminate contributions of these ions to inward whole-cell currents. Under these conditions, no membrane current was observed during a voltage step from −70 to +10 mV, whereas in the presence of 2 mm extracellular Zn2+, a sustained inward current appeared (Fig. 1A) with an average steady-state amplitude of −19 ± 1 pA (n = 33) and a current-voltage (I–V) relationship consistent with mediation by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Fig. 1B). No significant voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation was observed in inward currents recorded in the presence of Zn2+ after prepulses of 1 s duration, although currents carried by Ca2+ showed substantial inactivation in the same conditions (Fig. 2). To compare the activation kinetics of inward currents recorded in the presence of either Zn2+ or Ca2+, the 10–90 % rise times of currents elicited by voltage steps to 0 mV were measured, revealing a slower activation phase when Zn2+ rather than Ca2+ was used as the putative charge carrier (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Zn2+ produced an inward current in cultured cortical neurones

A, an inward current was elicited in the presence but not the absence (Control) of 2 mm Zn2+ by a voltage step to +10 mV. Illustrated are superimposed traces from a representative cell (left; data filtered at 0·5 kHz for display) and the averaged current from 33 cells in 2 mm Zn2+ (right; no additional filter). Dotted line indicates the baseline zero current level for these leak-subtracted traces (see Methods). B, the I–V relationship of steady-state current recorded during voltage steps from −70 mV in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+ is shown as the mean ± s.e.m. of 5 cells. Sample traces over a range of voltages (mV) are illustrated for a representative cell (inset; current traces here and in subsequent figures were filtered at 1 or 2 kHz to optimise legibility). ‘Steady-state current’ in these and the other experiments reported here refers to an average of the sustained component of current, minus baseline, during a voltage step; for instance, the average current recorded during the last 100 ms of a 200 ms pulse. A reversal potential appears in this I–V relationship, and an outward current was evident at positive potentials. This outward current was probably not carried by Zn2+ that had accumulated within a cell during experiments, as recorded cells were perfused with BAPTA (2 mm; Kd for Zn2+ = 1–10 nm; Aballay et al. 1995). More likely, intracellular cations such as Na+ and Li+ (Table 1), as well as some residual K+, may have accounted for the outward conductance, by analogy with the known effect of intracellular monovalent cations to influence the experimentally observed reversal potential of voltage-gated Ca2+ currents (Hille, 1992).

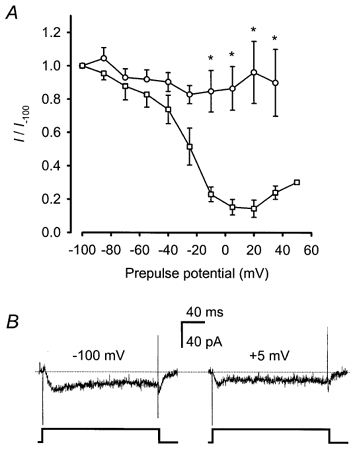

Figure 2.

Zn2+ current exhibited no voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation

A, after 1 s prepulses to the indicated potentials, the amplitude of steady-state inward currents elicited by immediately subsequent voltage steps to 0 mV in the presence of 500 μm Zn2+ (○; n = 6) or 2 mm Ca2+ (□; n = 3) are plotted relative to values obtained after a prepulse to −100 mV. In each cell tested, families of voltage pulses were delivered twice – once in an ascending order (−100 to +50 mV), and once in a descending order, to help compensate for any non-voltage-dependent current run-down. * Significant difference between relative current amplitudes recorded in Zn2+versus Ca2+ after the indicated prepulse potentials (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's t test). Points represent means ± s.e.m.B, traces obtained by voltage steps from −70 to 0 mV after a 1 s prepulse to −100 mV (left) or +5 mV (right) are illustrated for the cell for which the greatest degree of inactivation was observed in the presence of 500 μm Zn2+. The dotted line indicates the zero current level. The sustained component (latter 100 ms) of the inward currents were compared to generate the graph in A.

Table 2.

Rise times of currents carried by Zn2+ or Ca2+

| Charge carrier | pH | 10–90%(ms) rise time | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+ (1 mm) | 7.4 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 7 |

| Zn2+ (0.5 mm) | 7.4 | 12 ± 2 | 12 |

| Zn2+ (0.5 mm) | 6.4 | 14 ± 2 | 12 |

Rise times were calculated from the rising phase of currents evoked by voltage steps from −70 to 0 mV. Rise times differ significantly between Zn2+ and Ca2+ currents at pH 7.4 (P < 0.05, Student's t test) but not between Zn2+ currents at pH 7.4 and 6.4.

Zn2+ concentration affects current amplitude and voltage sensitivity

To test the hypothesis that Zn2+ was the charge carrier for the inward current described above, the effects of varying the extracellular Zn2+ concentration ([Zn2+]o) were explored. As [Zn2+]o was increased through a range from 200 μm to 1 mm, the steady-state inward current amplitudes elicited by voltage steps from −70 to 0 mV increased (Fig. 3). Increasing [Zn2+]o to 2 mm did not increase inward current amplitude any further.

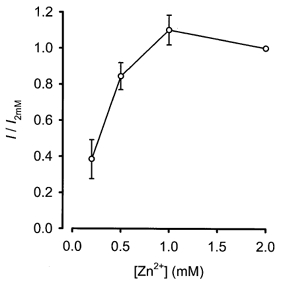

Figure 3.

Inward current amplitude at 0 mV depended upon extracellular Zn2+ concentration

Increasing [Zn2+]o increased the amplitude of steady-state currents elicited by voltage steps to 0 mV. Points represent means ± s.e.m. of 4–7 cells and are plotted relative to currents elicited in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+.

To determine whether this positive correlation between [Zn2+]o and steady-state current amplitude at 0 mV was due to an increase in maximum steady-state current amplitude or a shift in the I–V relationship, I–V curves were constructed in the presence of 50 μm and 2 mm extracellular Zn2+ (Fig. 4A). The maximum steady-state current amplitude recorded in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+ was larger than in 50 μm Zn2+. In addition, the I–V curve peak in 2 mm Zn2+ occurred at a more depolarised membrane potential than in 50 μm Zn2+. When curves were fitted to the I–V data, the voltage dependence of channel activation could be approximated (see Methods). Raising the Zn2+ concentration caused the channel activation-voltage relationship to shift rightwards with some reduction in slope; Vh was approximately −22 mV in 50 μm Zn2+ and +2·1 mV in 2 mm Zn2+ (Fig. 4B).

Zn2+ current is blocked by voltage-gated Ca2+ channel antagonists

To investigate whether voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediated the inward current recorded in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+ and to determine which subtypes of these channels were involved, we tested voltage-gated Ca2+ channel antagonists for their effects on the current (Fig. 5A). Gd3+ (10 μm), a non-subtype-selective Ca2+ channel antagonist (Lansman, 1990; Canzoniero et al. 1993), suppressed steady-state current amplitude by 86 ± 5 % (n = 8). Nimodipine (1 μm), an L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist, attenuated a larger portion of the inward current (81 ± 10 %; n = 6) than ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 μm; 33 ± 4 %; n = 6), an N-type Ca2+ channel antagonist. In contrast, MK-801 (1 μm), an NMDA receptor-gated channel blocker, had no effect on the current amplitude (0·0 ± 8 % compared to controls; n = 3). Further experiments with nimodipine demonstrated that its inhibition of a Zn2+ current was reversible (Fig. 5B) and occurred at all voltage levels (Fig. 5C).

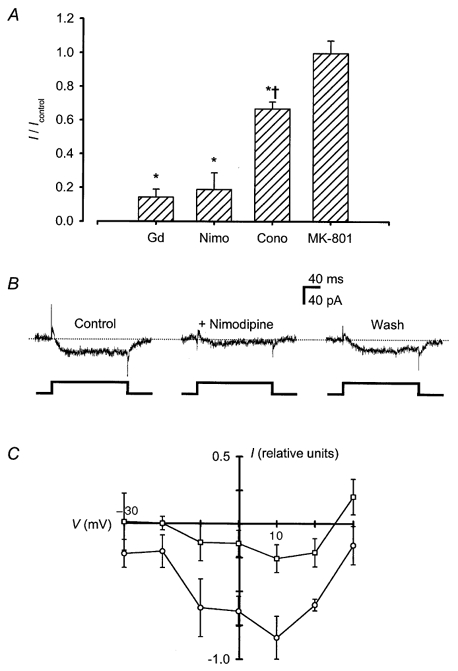

Figure 5.

Zn2+ current was sensitive to blockade by non-specific and specific blockers of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

A, steady-state Zn2+ current was inhibited by 10 μm Gd3+ (Gd), 1 μm nimodipine (Nimo), and 1 μm ω-conotoxin GVIA (Cono), but not by 1 μm MK-801. Zn2+ current was evoked by a voltage step to +10 mV in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+. The level of steady-state current recorded in the presence of an antagonist was normalised to current amplitude measured with Zn2+ alone and plotted as the mean + s.e.m. of 3–8 cells per condition. Cells were perfused with drugs or control solution for 30 s between voltage step trials. * Significant difference between normalised steady-state current amplitudes measured in the presence and absence of an agent; † Significant difference compared to currents measured after treatment with nimodipine or Gd3+ (P < 0·05, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's t test). B, current traces from a representative cell demonstrate reversible inhibition of Zn2+ current by 1 μm nimodipine; the cell was treated as in A. The dotted line represents the zero current level. C, the I–V relationship of steady-state currents recorded in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+ in the absence (○) or presence (□) of 1 μm nimodipine is plotted. I–V curves from 3 cells were normalised, each to its peak, and averaged. Points represent means ± s.e.m.

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel-mediated Zn2+ influx can occur in the presence of Ca2+

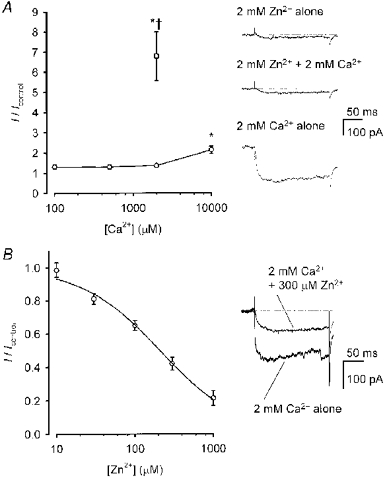

While isolating the contribution of Zn2+ to voltage-gated inward currents required the removal of other mono- and divalent cations – including Ca2+, in particular – from the extracellular bathing solution, it is important to determine whether voltage-gated Ca2+ channel-mediated Zn2+ entry can occur in physiological solutions. First, the effect of extracellular Ca2+ on Zn2+ current was examined. When inward currents were generated by voltage steps in the presence of 2 mm Zn2+, extracellular Ca2+ up to 2 mm had no effect on steady-state current amplitude (n = 7–14 cells per Ca2+ concentration; Fig. 6A). At 10 mm Ca2+, the net amplitude of inward current doubled compared to the level of current recorded in Zn2+ alone, but it was not as high as the currents measured in the presence of 2 mm Ca2+ alone (n = 4; Fig. 6A), suggesting that the presence of Zn2+ impeded Ca2+ permeation. To confirm that Zn2+ could block cortical neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ current as reported previously in other systems (see Introduction), the effect of Zn2+ on voltage-gated inward currents generated in the presence of 2 mm Ca2+ was tested. In contrast to the effect of Ca2+ on Zn2+ current, Zn2+ exerted a dose-dependent depression of Ca2+ current, with an approximate IC50 of 210 μm (n = 4; Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Zn2+ competed with Ca2+ for voltage-gated Ca2+ channel permeation

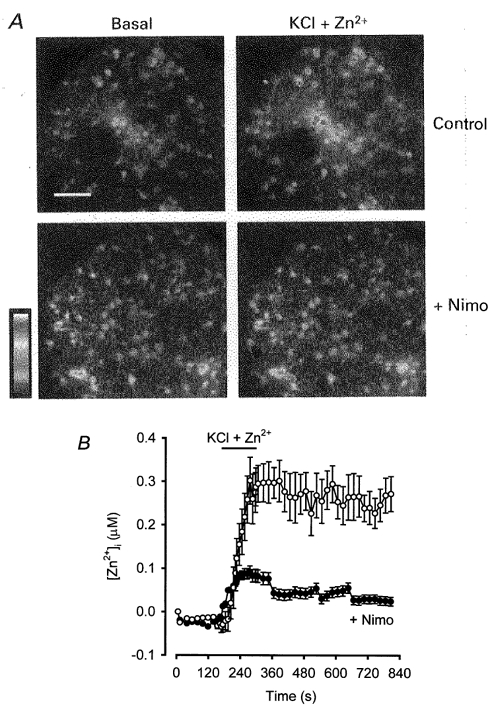

Since it is impossible to assign to Zn2+ a defined portion of the inward current evoked in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ plus Zn2+, we turned to Zn2+-selective fluorimetric imaging to verify that Zn2+ can permeate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the presence of physiological extracellular cation concentrations. Cortical neurones were loaded with the Zn2+-selective fluorescent probe Newport Green, which is capable of discriminating Zn2+ from other divalent cations, including Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Canzoniero et al. 1999; Sensi et al. 1999). When Newport Green-loaded neurones were exposed to depolarising conditions (60 mm KCl, 2 min) in the presence of physiological extracellular cation concentrations plus 300 μm Zn2+, a marked increase in [Zn2+]i was detected. The addition of nimodipine (10 μm) substantially attenuated the KCl-induced [Zn2+]i increase, confirming that Zn2+ entry occurred predominantly through L-type Ca2+ channels (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediated depolarisation-induced rises in [Zn2+]i in physiological saline

A, cortical neuronal cultures loaded with Newport Green and bathed in Hepes-buffered saline (see Methods) were exposed for 2 min to either high-potassium + 300 μm Zn2+ (control) or high-potassium + 300 μm Zn2+ + 10 μm nimodipine (high-potassium solutions contained 60 mm KCl, 65 mm NaCl, and were otherwise identical to the Hepes-buffered saline). MK-801 (10 μm) and NBQX (10 μm) were present throughout experiments to block glutamate receptor activation by endogenous glutamate release. Pseudo-colour images from a representative experiment depict changes in [Zn2+]i according to the Newport Green fluorescence values indicated in the scale. The fluorescence signal attributed to increased [Zn2+]i was completely quenched by the addition of the selective membrane-permeable Zn2+ chelator, 100 μm TPEN (not shown). Scale bar = 50 μm. B, each trace represents the change in [Zn2+]i observed in the same experiments described in A (control, n = 57 cells; nimodipine (Nimo), n = 52). Fluorescence values were converted to Zn2+ concentrations by a calibration performed at the end of the experiment (see Methods).

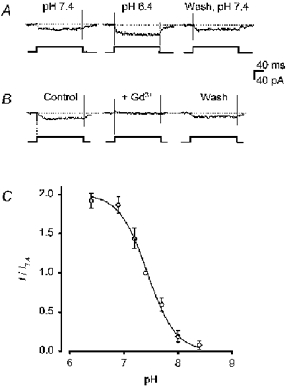

Zn2+ current is enhanced by extracellular acidity

Lowering extracellular pH (pHo) suppresses HVA Ca2+ channel currents carried by Ca2+, Ba2+, or monovalent cations in a variety of cell types including hippocampal neurones (e.g. Tombaugh & Somjen, 1996), and we examined the effect of this manoeuvre on inward currents carried by 1 mm Ca2+ or 500 μm Zn2+. In these experiments, intracellular pH was buffered to 7·4 with 10 mm Hepes (Table 1). Consistent with previous studies, lowering pHo from 7·4 to 6·4 reversibly decreased Ca2+ current amplitude at 0 mV by 29 ± 2 % (n = 7). In contrast, the same drop in pHo reversibly enhanced Zn2+ current amplitude at 0 mV by 92 ± 10 % (n = 5; Fig. 8A), and raising pHo from 7·4 to 8·4 resulted in near-complete suppression of the Zn2+ current. Extracellular pH affected Zn2+ current in a graded fashion with an approximate pK of 7·4 (Fig. 8C). Compared to currents at pHo 7·4, Zn2+ currents recorded at pHo 6·4 were similarly sensitive to blockade by 10 μm Gd3+ (currents were suppressed by 86 ± 5 %; n = 4; Fig. 8B) and had a similar time constant of Zn2+ current activation (Table 2).

Figure 8.

Extracellular acidity enhanced Zn2+ current

We examined the effects of varying pHo on the I–V relationship of the Zn2+ current. A decrease in pHo was accompanied by an increase in inward steady-state Zn2+ current amplitude at all membrane potentials as well as a positive shift in reversal potential (n = 12; Fig. 9A) from 29 mV at pHo 7·4 to 59 mV at pHo 6·4 (approximated by fitting curves to the I–V data; see Methods), although the voltage dependence of the estimated steady-state Zn2+ current activation was similar in both conditions, with Vh being −13 mV at pHo 7·4 and −11 mV at pHo 6·4 (Fig. 9B). These data suggest that the enhanced Zn2+ current observed at the lower pHo was not due to an increase in the activity of free Zn2+ available for voltage-gated Ca2+ channel permeation, as an increase in [Zn2+]o sufficient to double peak inward current would be expected to cause a considerable shift in Vh (see Fig. 4). Consistent with the hypothesis that the observed relationship between Zn2+ current amplitude and pHo was not explained by changes in Zn2+ activity, the amount of zinc recoverable from solutions, which were prepared in the same plastic containers used in experiments and exposed to cultured cortical neurones, was no different at pH 6·4 than at 7·4 (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate here that extracellular Zn2+ carried a voltage-activated inward current in murine cortical neurones exhibiting properties consistent with mediation by HVA Ca2+ channels. Under the recording conditions utilised, only extracellular Zn2+ or intracellular Cl− were available to carry inward current, and current amplitude increased with increasing extracellular ZnCl2. Consistent with the propensity of divalent cations to screen negative membrane surface charges (Hille, 1992), increasing [Zn2+]o increased the threshold and peak potentials of the current's I–V relationship to a degree consistent with similar observations of Zn2+ currents in Helix neurones (Oyama et al. 1982). Relative to Ca2+ currents in these neurones, Zn2+ current was smaller and showed slower activation kinetics, and unlike Ca2+ currents, Zn2+ current did not exhibit voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation. In addition, Zn2+ was able to permeate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the presence of Ca2+. Unexpectedly, Zn2+ current amplitude increased with decreasing pHo, whereas HVA Ca2+ currents were suppressed by the same manoeuvre. Zn2+ current enhancement at lower pHo was not accompanied by changes in activation kinetics or in the voltage sensitivity of channel gating.

Zn2+ current was mediated by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

Supporting a role for HVA Ca2+ channels in mediating voltage-activated Zn2+ current, the I–V relationship of the current exhibited a profile typical for these channels (Fig. 1), and the current was sensitive to L- and N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blockers (Figs 5 and 7). Nimodipine blocked a majority of Zn2+ entry into cortical neurones as measured both by electrophysiology and fluorescent dye imaging, suggesting that L-type channels carry the bulk of voltage-activated Zn2+ influx. ω-Conotoxin GVIA blocked a smaller proportion of the current, suggesting a smaller role for N-type channels. These data do not permit a calculation of the relative permeabilities of L- versus N-type channels to Zn2+, as the magnitude of the pharmacological effects is also affected by differences in the population sizes and membrane distribution of these channel subtypes.

As noted above, previous electrophysiological studies of the effects of Zn2+ on mammalian voltage-gated Ca2+ channels have focused on the ability of Zn2+ to serve as a channel blocker (Winegar & Lansman, 1990; Büsselberg et al. 1992). However, Zn2+ permeation and blockade of current carried by other ions through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels may occur simultaneously, as has been proposed, for instance, in the interactions of Mg2+ (Ascher & Nowak, 1988) and Zn2+ (Christine & Choi, 1990) with NMDA receptor-gated channels. Winegar & Lansman (1990) showed that Zn2+ antagonises Ba2+ currents through single dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channels in mouse myotubes in a voltage-dependent manner, suggesting that Zn2+ binds in or near the channel pore. This blockade was characterised by an increase in open channel noise, presumably reflecting fast, unresolved blocking and unblocking of the channel, and calculations based on the kinetics of the blockade suggested that Zn2+ binds to open channels and has an exit rate from the pore faster than that of Mg2+, Cd2+, or La3+. In addition, although the entry rate of Zn2+ into the Ca2+ channel pore was linearly dependent on [Zn2+]o, the exit rate was independent of Zn2+ concentration, suggesting, in agreement with data in the present study, that as Zn2+ exits a Ca2+ channel pore, it leaves from the cytoplasmic face.

Extracellular acidity enhanced Zn2+ current

In this study, decreasing pHo was found to have opposite effects on inward currents carried by 500 μm Zn2+ and by 1 mm Ca2+. The enhancement of Zn2+ current observed at acidic pH was not accompanied by a shift in the voltage sensitivity of the current (Fig. 9), as was seen when [Zn2+]o was increased (Fig. 4), arguing against the possibility that this enhancement was due to an increase in free Zn2+. In agreement with that observation, the amount of zinc recoverable from recording solutions was not affected by pH (Table 3).

The ability of decreasing pHo to suppress HVA Ca2+ channel currents carried by Ca2+, Ba2+, or monovalent cations is well established, and appears to reflect some combination of two underlying mechanisms. First, experiments on single dihydropyridine-sensitive voltage-gated Ca2+ channels have suggested the existence of a low-conductance state for L-type channels that is stabilised by protonation and destabilised by the binding of permeant cations (Prod'som et al. 1987; Pietrobon et al. 1988). Second, H+ may screen negative surface charges and thus alter the voltage dependence of channel gating (e.g. Iijima et al. 1986; Prod'som et al. 1989).

Additional studies will be needed to delineate the mechanisms responsible for the paradoxical effect of lowering pHo to enhance Zn2+ current through HVA Ca2+ channels. Perhaps H+ permeates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and increased Zn2+ permeation does not account for the increased current amplitude. Arguing against this possibility is the observation that in the presence of monovalent cations as charge carriers, H+ affects single L-type Ca2+ channels without apparently interacting with the channel pore (Prod'som et al. 1987). Some controversy surrounds this point, as recent work has shown that the sensitivity of L-type Ca2+ channels to pHo can be altered by mutagenesis of the glutamate residues that form the high-affinity Ca2+ interaction site in the channel pore (Chen et al. 1996), suggesting that pore interactions may indeed account for the ability of H+ to elicit changes in channel conductance. However, single channel studies have revealed no direct competition between permeant cations and H+ for entry into the channel (Pietrobon et al. 1988; Prod'som et al. 1989); even if such competition were possible, Zn2+, with a relatively high affinity for voltage-gated Ca2+ channel pore binding sites, might be expected to exclude H+ from the pore even more effectively than other permeant cations.

Alternatively, extracellular H+ may allosterically influence the permeability of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Prod'som et al. 1987, 1989; Pietrobon et al. 1988, 1989), as is the case, for instance, for NMDA receptor-gated channels (Tang et al. 1990; Traynelis & Cull-Candy, 1990). A H+-induced conformational change in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels may increase their permeability to Zn2+ while decreasing their permeability to Ca2+ and monovalent cations. The increase in reversal potential observed in Zn2+ currents at lower pHo is consistent with an increase in permeability to Zn2+ relative to permeant intracellular cations, which, in these experiments, may include Na+ or Li+ (see Fig. 1 legend and Table 1). The fact that the net membrane conductance g (sum of all conductances when multiple permeant ions are present; see Methods), as estimated from curve fits to I–V data (Fig. 9A), did not change with a change in pHo is consistent with a simple model in which a small absolute increase in Zn2+ conductance is counterbalanced by a comparable decrease in absolute conductance to permeant intracellular cations, although other scenarios cannot be excluded. Regardless of the exact underlying mechanism, the observed ability of extracellular acidity to enhance voltage-gated Ca2+ channel permeability to Zn2+ suggests that H+ may have more complex effects on ion permeation through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels than previously thought.

Physiological significance

Both electrophysiological and fluorimetric evidence is presented supporting the notion that Zn2+ can permeate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the presence of physiological amounts of other cations, including Ca2+. First, unlike the effect of Ca2+ on voltage-gated Ca2+ channel-mediated Ba2+ currents (Hille, 1992), no blockade of Zn2+ current was evident at low [Ca2+]o; net inward current amplitude in the presence of 2 mm extracellular Zn2+ was unaffected by up to equimolar amounts of extracellular Ca2+. When [Ca2+]o exceeded [Zn2+]o, at least some of the inward current was probably carried by Ca2+, but the presence of Zn2+ clearly impeded voltage-gated Ca2+ channel permeability to Ca2+. As in other cell types, Zn2+ blocked cortical neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ currents. Second, neurones loaded with the fluorescent Zn2+ probe Newport Green exhibited depolarisation-evoked increases in [Zn2+]i in the presence of physiological concentrations of extracellular cations plus 300 μm extracellular Zn2+. Depolarisation-evoked Zn2+ influx was largely inhibited by nimodipine, implicating L-type Ca2+ channels as the major mediators of membrane permeability to Zn2+. In these experiments, [Ca2+]o exceeded [Zn2+]o by sixfold.

The demonstration that murine neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels can carry an inward Zn2+ current supports the notion that blockade of these channels may have therapeutic utility in pathological conditions, such as cardiac arrest or sustained seizures, where excessive Zn2+ influx may contribute to neuronal death (Choi & Koh, 1998). Although the absolute permeability of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to Zn2+ is low compared to Ca2+, these channels exhibited much less voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation when Zn2+, instead of Ca2+, was used as the charge carrier (Fig. 2). These data suggest that voltage-gated Ca2+ channels could indeed mediate the sustained increases in [Zn2+]i observed in conditions where Zn2+ is toxic to cortical neurones (Canzoniero et al. 1999). In addition, data presented here raise the novel possibility that the neurotoxic contribution of Zn2+ influx through HVA Ca2+ channels may be specifically enhanced by increases in extracellular acidity caused by the build-up of brain lactate associated with ischaemic conditions.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank J. H. Steinbach and C. J. Lingle for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Student Research Training Fellowship (G. A.K.) and NIH grant NS 32636 (D.W.C.).

References

- Aballay A, Sarrouf MN, Colombo MI, Stahl PD, Mayorga LS. Zn2+ depletion blocks endosome fusion. Biochemical Journal. 1995;312:919–923. doi: 10.1042/bj3120919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almers W, McCleskey EW. Non-selective conductance in calcium channels of frog muscle: calcium selectivity in a single-file pore. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;353:585–608. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher P, Nowak L. The role of divalent cations in the N-methyl-D-aspartate responses of mouse central neurones in culture. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;399:247–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf SY, Chung SH. Release of endogenous Zn2+ from brain tissue during activity. Nature. 1984;308:734–736. doi: 10.1038/308734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atar D, Backx PH, Appel MM, Gao WD, Marban E. Excitation-transcription coupling mediated by zinc influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:2473–2477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büsselberg D, Michael D, Evans ML, Carpenter DO, Haas HL. Zinc (Zn2+) blocks voltage gated calcium channels in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion cells. Brain Research. 1992;593:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91266-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canzoniero LM, Taglialatela M, Di Renzo G, Annunziato L. Gadolinium and neomycin block voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels without interfering with the Na+-Ca2+ antiporter in brain nerve endings. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;245:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90116-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canzoniero LMT, Turetsky DM, Choi DW. Measurement of intracellular free zinc concentrations accompanying zinc-induced neuronal death. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(RC31):1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-j0005.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X-H, Bezprozvanny I, Tsien RW. Molecular basis of proton block of L-type Ca2+ channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:363–374. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.5.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Koh JY. Zinc and brain injury. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1998;21:347–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Yokoyama M, Koh J. Zinc neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture. Neuroscience. 1988;24:67–79. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christine CW, Choi DW. Effect of zinc on NMDA receptor-mediated channel currents in cortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:108–116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00108.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ. Neurobiology of zinc and zinc-containing neurons. International Review of Neurobiology. 1989;31:145–238. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund W-D, Reddig S. AMPA/Zn2+-induced neurotoxicity in rat primary cortical cultures: involvement of L-type calcium channels. Brain Research. 1994;654:257–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda J, Kawa K. Permeation of manganese, cadmium, zinc, and beryllium through calcium channels of an insect muscle membrane. Science. 1977;196:309–311. doi: 10.1126/science.847472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S, Takahashi K. Surface density of calcium ions and calcium spikes in the barnacle muscle fiber membrane. Journal of General Physiology. 1967;50:583–601. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison NL, Gibbons SJ. Zn2+: an endogenous modulator of ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:935–952. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland RP. In: Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Chemicals. 6. Spence MTZ, editor. Eugene, OR, USA: Molecular Probes; 1996. pp. 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. MA. USA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Howell GA, Welch MG, Frederickson CJ. Stimulation-induced uptake and release of zinc in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1984;308:736–738. doi: 10.1038/308736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima T, Ciani S, Hagiwara S. Effects of the external pH on Ca channels: experimental studies and theoretical considerations using a two-site, two-ion model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1986;83:654–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawa K. Zinc-dependent action potentials in giant neurons of the snail, Euhadra quaestia. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1979;49:325–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01868990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Yu SP, Choi DW. Measurement of zinc current through cortical neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: enhancement by extracellular acidity. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998;24:466. [Google Scholar]

- Koh J-Y, Choi DW. Zinc toxicity on cultured cortical neurons: involvement of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neuroscience. 1994;60:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J-Y, Suh SW, Gwag BJ, He YY, Hsu CY, Choi DW. The role of zinc in selective neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia. Science. 1996;272:1013–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuk PG, Mironov SL, Shuba Ya M. Two ion-selecting filters in the calcium channel of the somatic membrane of mollusc neurons. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1983;76:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lansman JB. Blockade of current through single calcium channels by trivalent lanthanide cations: effect of ionic radius on the rates of ion entry and exit. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;95:679–696. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobner D, Canzoniero LMT, Manzerra P, Gottron F, Ying H, Knudson M, Tian M, Dugan LL, Kerchner GA, Sheline CT, Korsmeyer SJ, Choi DW. Zinc-induced neuronal death in cortical neurons. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2000;46:797–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manev H, Kharlamov E, Uz T, Mason RP, Cagnoli CM. Characterization of zinc-induced neuronal death in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule cells. Experimental Neurology. 1997;146:171–178. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama Y, Nishi K, Yatani A, Akaike N. Zinc current in Helix soma membrane. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1982;72C:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(82)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Clausell J, Danscher G. Intravesicular localization of zinc in rat telencephalic boutons: a histochemical study. Brain Research. 1985;337:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon D, Prod'som B, Hess P. Conformational changes associated with ion permeation in L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1988;333:373–376. doi: 10.1038/333373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon D, Prod'som B, Hess P. Interactions of protons with single open L-type calcium channels: pH dependence of proton-induced current fluctuations with Cs+, K+, and Na+ as permeant ions. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:1–21. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prod'som B, Pietrobon D, Hess P. Direct measurement of proton transfer rates to a group controlling the dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel. Nature. 1987;329:243–246. doi: 10.1038/329243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prod'som B, Pietrobon D, Hess P. Interactions of protons with single open L-type calcium channels: location of protonation site and dependence of proton-induced current fluctuations on concentration and species of permeant ion. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:23–42. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose K, Goldberg MP, Choi DW. Cytotoxicity in murine neocortical cell culture. In: Tyson CA, Frazier JM, editors. Methods in Toxicology. San Diego, CA. USA: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sensi SL, Canzoniero LMT, Yu SP, Ying HS, Koh J-Y, Kerchner GA, Choi DW. Measurement of intracellular free zinc in living cortical neurons: routes of entry. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9554–9564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi SL, Yin HZ, Carriedo SG, Rao SS, Weiss JH. Preferential Zn2+ influx through Ca2+-permeable AMPA/kainate channels triggers prolonged mitochondrial superoxide production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:2414–2419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart TG, Xie X, Krishek BJ. Modulation of inhibitory and excitatory amino acid receptor ion channels by zinc. Progress in Neurobiology. 1994;42:393–441. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CM, Dichter M, Morad M. Modulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate channel by extracellular H+ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1990;87:6445–6449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh GC, Somjen GG. Effects of extracellular pH on voltage-gated Na+, K+, and Ca2+ currents in isolated rat CA1 neurons. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:719–732. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønder N, Johansen FF, Frederickson CJ, Zimmer J, Diemer NH. Possible role of zinc in the selective degeneration of dentate hilar neurons after cerebral ischemia in the adult rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;109:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90002-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Cull-Candy SG. Proton inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in cerebellar neurons. Nature. 1990;345:347–350. doi: 10.1038/345347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega MT, Villalobos C, Garrido B, Gandía L, Bulbena O, García-Sancho J, García AG, Artalejo AR. Permeation by zinc of bovine chromaffin cell calcium channels: relevance to secretion. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;429:231–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00374317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt K, Mellor J, Tong G, Nicoll R. The actions of synaptically released zinc at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JH, Hartley DM, Koh J-Y, Choi DW. AMPA receptor activation potentiates zinc neurotoxicity. Neuron. 1993;10:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90240-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winegar BD, Lansman JB. Voltage-dependent block by zinc of single calcium channels in mouse myotubes. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:563–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HZ, Weiss JH. Zn2+ permeates Ca2+ permeable AMPA/kainate channels and triggers selective neural injury. NeuroReport. 1995;6:2553–2556. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512150-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama M, Koh J, Choi DW. Brief exposure to zinc is toxic to cortical neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1986;71:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]