Abstract

Previous studies which have indicated that the stimulation of ventricular mechanoreceptors induces significant reflex responses can be criticised because of the likelihood of concomitant stimulation of coronary arterial baroreceptors. We therefore undertook this investigation to examine the coronary and ventricular mechanoreflexes in a preparation in which the pressure stimuli to each region were effectively separated.

Dogs were anaesthetised, artificially ventilated and placed on cardiopulmonary bypass. A balloon at the ventricular outflow separated pressure in the left ventricle from that perfusing the coronary arteries. Ventricular pressures were changed by varying inflow and outflow of blood entering and leaving the ventricle through an apical cannula, and coronary pressure by changing pressure in a reservoir connected to a cannula tied in the aortic root. Pressures distending carotid and aortic baroreceptors were controlled. Changes in descending aortic perfusion pressure (flow constant) were used to assess systemic vascular responses.

Large changes in carotid sinus and coronary pressures decreased vascular resistance by 35 ± 1.9 and 40 ± 2.5 %, respectively. Intracoronary injections of veratridine (30–60 μg) decreased vascular resistance by 31 ± 2.5 %. However, large increases in ventricular pressure decreased resistance by only 9 ± 2.2 %.

Significant changes in vascular resistance were obtained with increases in coronary arterial pressure from 60 to 90 mmHg. However, ventricular pressures had to increase to 152/18 mmHg (systolic/end-diastolic) before there was a significant response.

These results show that coronary mechanoreceptors are likely to play an important role in cardiovascular control. If ventricular receptors have any function at all, it is as a protective mechanism during gross distension, possibly associated with myocardial ischaemia.

It has been known for a very long time that very powerful depressor reflexes can be obtained from stimulation of reflexogenic areas in the left ventricle (Von Bezold & Hirt, 1867; Dawes, 1947; Jarisch & Zotterman, 1948; McGregor et al. 1986). However, all the studies showing large responses have involved intracoronary injections of foreign chemicals including veratridine, capsaicin and phenyl diguanide, or administration of inflammatory products such as a prostaglandin or bradykinin (Kaufman et al. 1980). Some ventricular afferents have been shown also to possess mechanosensitivity (Coleridge et al. 1964; Thames et al. 1977; Thorén, 1977; Drinkhill et al. 1993), but there is no conclusive evidence that mechanical stimulation results in major depressor responses.

Interventions that were thought to stimulate ventricular mechanoreceptors include distension by negative pressures applied to a cardiometer (Daly & Verney, 1927), direct ventricular distension by a balloon (Salisbury et al. 1960; Chevalier et al. 1974; Zelis et al. 1977; Hoka et al. 1988) and ventricular outflow obstruction (Aviado & Schmidt, 1959; Ross et al. 1961; Mark et al. 1973; Challenger et al. 1987). The problem with all these techniques, apart from the lack of quantification in most cases, is the failure of adequate localisation of the stimulus to the left ventricle. It is now apparent that the coronary arteries contain baroreceptors (Brown, 1966; Al-Timman et al. 1993; Drinkhill et al. 1993) and most of the previous investigations, which were thought to have examined the effects of ventricular reflexes, would almost certainly have altered the stimuli to these very sensitive coronary receptors (McMahon et al. 1996).

The main purpose of the present investigation, therefore, was to provide a selective stimulus to ventricular mechanoreceptors, which would not have influenced other reflexogenic areas, particularly those in the coronary arteries, and attempt finally to resolve the question as to whether left ventricular mechanoreceptors are important in cardiovascular control. In order to evaluate the likely physiological importance of ventricular mechanoreceptors, we compared responses to increases in ventricular pressures with those resulting from the stimulation of other known reflexes – coronary baroreceptors, coronary chemosensitive nerves and carotid baroreceptors.

METHODS

Animals and preparation

Beagle dogs of both sexes weighing 15–20 kg were anaesthetised with α-chloralose (Vickers Laboratories Ltd, Leeds, UK), 100 mg kg−1i.v. in saline. A continuous i.v. infusion of chloralose (0.5–1.0 mg kg−1 min−1) maintained a steady level of anaesthesia throughout the experiment. Prior to major surgical procedures, alfentanyl (30 μg kg−1) was given by a slow intravenous infusion. During surgery, it was infused continuously at 2.5 μg min−1 and was terminated 60 min prior to the start of the protocol. At intervals throughout the experiment, the appropriate depth of anaesthesia was assessed from the stability of blood pressure and heart rate, the absence of a significant response to toe pinch and only a minimal contraction of the limbs to a sharp tap on the surgical table.

A longitudinal mid-line incision was made in the neck, the trachea was cannulated and the dog was artificially ventilated with oxygen-enriched air using a Starling ‘Ideal’ pump, initially set at 17 ml kg−1 and 18 strokes min−1. The pH, PCO2 and PO2 in arterial blood were frequently determined using a pH/blood gas analyser (Instrumentation Laboratory, model 1610) and they were maintained within normal limits (see below) by adjustments of the stroke of the respiratory pump, the rate of oxygen inflow and infusions as required of molar sodium bicarbonate solution.

The left and right carotid sinuses were vascularly isolated by tying all branches from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, except the lingual artery, which was left for subsequent cannulation, taking care not to damage the innervation. The left side of the chest was widely opened by dividing the second to sixth ribs and the sternum. Once the pleural cavity had been breached an end-expiratory pressure of 3 cmH2O was applied. The descending aorta was mobilised by tying and cutting the upper six pairs of intercostal arteries. The left subclavian artery was freed from the surrounding tissue, the pericardium opened and a snare was carefully threaded around the ascending aorta 0.5–1 cm from its origin, just distal to the coronary ostia.

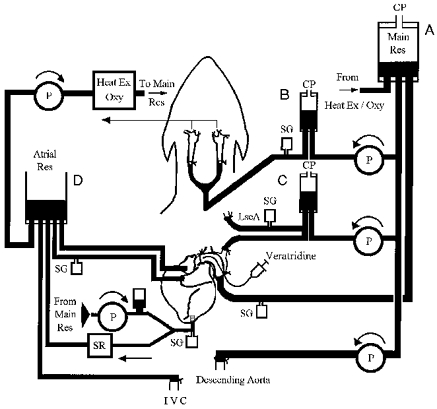

Heparin (500 i.u. kg−1i.v.) was administered to the animal immediately prior to cannulation. The perfusion circuit (Fig. 1) was part filled with a 2 l mixture of equal parts of mammalian Ringer solution and dextran in dextrose solution. Blood cells, obtained from a previous experiment and washed, were added to the perfusate solution. The circuit was then attached to the animal in the following sequence. A large curved stainless-steel cannula was inserted into the aortic arch to convey aortic flow to a pressurised reservoir (A in Fig. 1). Blood from this reservoir was distributed to various parts of the circuit. The descending aorta was cannulated and the subdiaphragmatic circulation perfused at a constant flow. The changes in perfusion pressure to this region provided an index of changes in vascular resistance. A full heart-lung bypass was achieved by inserting cannulae into the left and right atria, and the inferior vena cava (7, 7 and 10 mm i.d., respectively) and draining the blood into a reservoir (D in Fig. 1). Blood from this reservoir was pumped through a membrane blood oxygenator (Sorin Monolyth Integrated Lung, Sorin Biomedica Cardio, Saluggia, Italy) and thence back to the main reservoir.

Figure 1. Diagram of the experimental preparation.

A large cannula tied in the aortic root, just beyond the coronary ostea and distal to the LscA, created a pouch of aorta outside the cannula and conveyed blood to reservoir A from which it was distributed to the rest of the circuit. A cardiopulmonary bypass was created by draining blood from the inferior vena cava and both atria to reservoir D from which it was pumped through a heat/gas exchanger to reservoir A. Blood was pumped from reservoir A into: (i) reservoir B and into cannulae tied into both common carotid arteries; (ii) reservoir C and into cannulae in the peripheral and central ends of the LscA; (iii) the left ventricle (LV) at controlled flows, via a damping chamber, with outflow to reservoir D controlled by a Starling resistor; (iv) the descending aorta at constant flow. The LV was isolated from the coronary circulation by a catheter balloon inserted into the LV and positioned to occlude the aortic valve. Veratridine was administered into the coronary arteries by insertion of a catheter into the aortic root. Abbreviations: CP, constant pressure; LscA, left subclavian artery; IVC, inferior vena cava; SG, strain gauge transducer; P, pump; SR, Starling resistor.

A cannula (8 mm i.d.) was then inserted into the cavity of the left ventricle through a stab incision in the apex and secured by a purse-string suture. Blood was pumped through this cannula directly into the left ventricle from the main reservoir via a damping chamber. The outflow from the ventricle also passed through the apical cannula and this was regulated by the pressure applied to a Starling resistor (Knowlton & Starling, 1912) on the ventricular outflow.

Both carotid arteries were cannulated and perfused with blood from a separate pressurised reservoir (B in Fig. 1) and drained via the cannulated lingual arteries into the atrial reservoir. The aortic arch and cephalic region were perfused from another constant pressure reservoir (C in Fig. 1) through cannulae inserted into both the central and distal ends of the left subclavian artery.

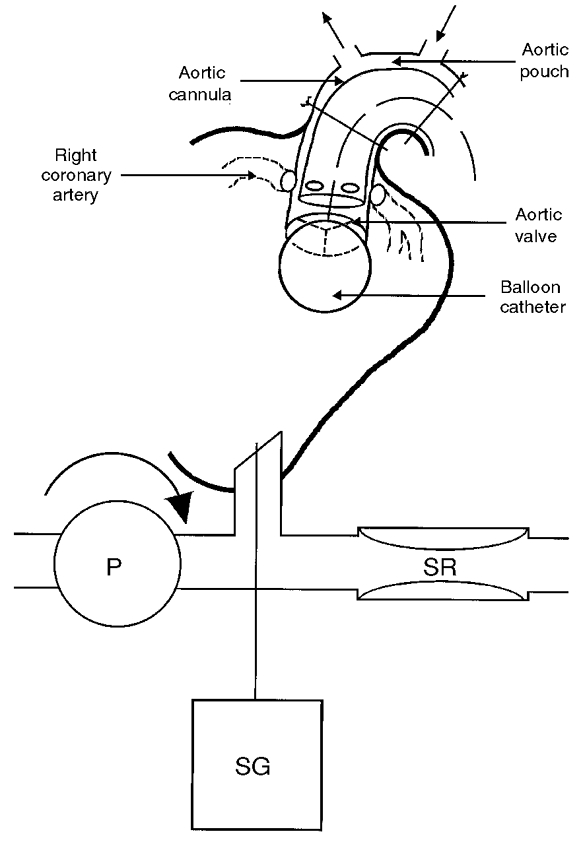

After completion of the cannulation, the snare previously placed around the ascending aorta was tied on to the stainless-steel cannula. This created a pouch of the aortic arch containing the aortic baroreceptors (and chemoreceptors) on the outside of this cannula. The pressure applied to the inside of the steel cannula determined coronary perfusion pressure. A balloon catheter (Atrioseptostomy catheter, Baxter International Inc., IL, USA) was then passed through the large stainless-steel cannula into the cavity of the left ventricle. It was inflated with 2–3 ml of saline and then retracted so that the balloon occluded the aortic valve, thereby isolating the coronary circulation from the left ventricle (see Fig. 2). Satisfactory positioning of the balloon was confirmed by observing independence of aortic and ventricular pressures. Its position was always confirmed postmortem. A catheter was advanced through the lumen of the aortic cannula, and was positioned adjacent to the coronary arteries, thus permitting the intracoronary delivery of veratridine.

Figure 2. Diagram showing how the balloon catheter was positioned to occlude the aortic valve and so isolating the left ventricle from the coronary circulation.

Abbreviations: SG, strain gauge transducer; P, pump; SR, Starling resistor.

Blood pressures were recorded, using nylon catheters attached to strain gauges (Gould-Statham P23 ID, Oxnard, CA, USA) from: the right carotid cannula (carotid sinus pressure), the aortic cannula (coronary arterial pressure), the left subclavian cannulae (cephalic and aortic pouch perfusion pressures), the apical left ventricular cannula (left ventricular pressure), the left atrial cannula (left atrial pressure) and the right femoral artery (systemic arterial perfusion pressure). These pressures were recorded on both a direct-writing electrostatic recorder (Model ES 1000, Gould Electronics, France) and a magnetic tape (Racal V-store, Racal Recorders Ltd, Southampton, UK). Data were analysed on-line using a real-time data acquisition unit (Fastdaq, Lectromed, Letchworth, UK). The temperature of the animal was recorded by a thermistor probe in the oesophagus and was maintained between 37 and 39°C by a heat exchanger incorporated into the circuit and by heating the animal table.

These experiments were carried out in accordance with the current UK legislation, the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Experiments were terminated by exsanguination of the animal while under deep anaesthesia.

Experimental procedure

After connection of the perfusion circuit, approximately 30 min were allowed for the animal to reach a stable state. During this time arterial blood gases were analysed and corrected so that the values of PO2, PCO2 and pH were 209.5 ± 11.2 mmHg, 38.0 ± 0.7 mmHg, and 7.4 ± 0.01. The haematocrit of arterial blood was 19 ± 1 %.

The following procedures were performed.

Carotid sinus pressure test

With coronary, aortic arch and cephalic, and ventricular pressures held constant, carotid sinus pressure was increased over the range 60–180 mmHg and the responses determined. Pressure changes were maintained for between 1 and 2 min, which enabled steady-state responses to be recorded.

Veratridine tests

With pressures perfusing carotid, aortic and cephalic, and coronary regions held constant, veratridine (30–60 μg) was injected via the aortic root cannula and flushed with 2 ml of saline. A 5 s average was taken of the maximal response and this was compared with the average values in the 30 s period preceding injection.

Coronary pressure test

Carotid sinus, aortic arch and cephalic, and left ventricular pressures were held constant while coronary arterial pressure was increased by increasing the pressures applied to the main reservoir in either a single step or in increments of 30 mmHg from 60 to 180 mmHg. Records were obtained of steady-state values at each step. These tests were repeated at intervals during the experiment to confirm the viability of the preparation.

Ventricular pressure tests

In these tests, carotid, aortic and cephalic, and aortic root pressures were held constant. Ventricular systolic pressure was changed either in a single step or in increments of 30 mmHg from 60 to 180 mmHg by changing the pressure to the Starling resistor with the rate of ventricular inflow held constant. This also resulted in changes in end-diastolic pressure, particularly at the higher ventricular systolic pressures. Records were obtained of steady-state values at each step.

Data analysis

Because we were mainly interested in examining reflexes from the heart, it was necessary to establish that the preparation responded normally. Therefore, comparisons of reflexes from different reflexogenic regions were only made if the responses to distension of the coronary arteries (over the full range of sensitivity) induced changes in systemic pressure in excess of 24 mmHg. The same criteria were also applied for the veratridine and carotid tests.

As it was not always possible to adjust ventricular pressures precisely to the intended values, plots were drawn of the systemic perfusion pressure against ventricular pressures, and the required values were determined by interpolation. All values reported are means ±s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (Tukey-Kramer multiple post hoc test comparisons), repeated measures analysis of variance (Dunnett’s multiple post hoc test comparison) or Student’s paired t test and considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

During the testing of responses to carotid, coronary and ventricular mechanoreceptors, and also ventricular chemosensitive nerves, pressures perfusing the regions not being studied were maintained at: carotid, 64.2 ± 1.9 mmHg; coronary, 85.6 ± 2.2 mmHg; ventricular systolic and end-diastolic, 65.8 ± 3.9 and 9.7 ± 0.9 mmHg. Pressures in the aortic arch and cephalic circulation were 118.0 ± 4.3 mmHg (in six animals, the cephalic circulation was perfused separately at 151.8 ± 4.8 mmHg). Atrial pressures were maintained at a low level due to the presence of atrial drains; in fifteen animals in which it was recorded, mean left atrial pressure was 1.4 ± 0.7 mmHg.

Responses to stimulation of carotid, coronary and ventricular mechanoreceptors and the coronary chemoreflex

In 26 animals we investigated the responses to large step increases in coronary arterial pressure between 60 and 180 mmHg; in 22 of them, responses were also determined to changes in carotid sinus pressure, and in 18, to changes in ventricular systolic pressure. In 10 animals we also studied the responses to injections of veratridine. Prior to each of these tests, control values for systemic perfusion pressure were: for carotid tests, 146.8 ± 5.5 mmHg; coronary tests, 174.1 ± 5.9 mmHg; ventricular chemoreflex, 134.8 ± 6.4 mmHg; ventricular mechanoreflex, 143.9 ± 7.4 mmHg. For the mechanoreceptor reflexes, the changes in arterial pressures were held at each level for 1–2 min to allow steady-state responses to be recorded, before being returned to the initial low value.

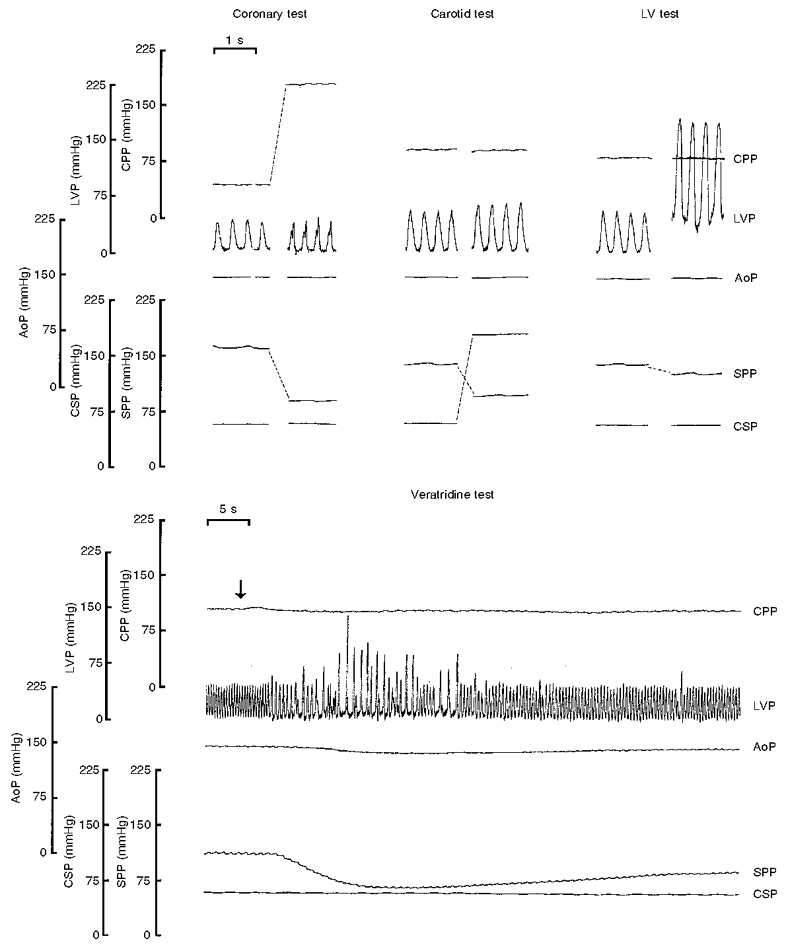

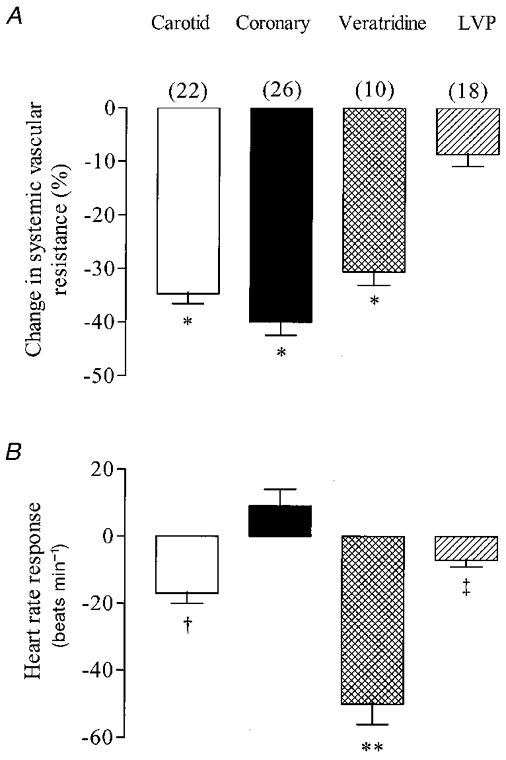

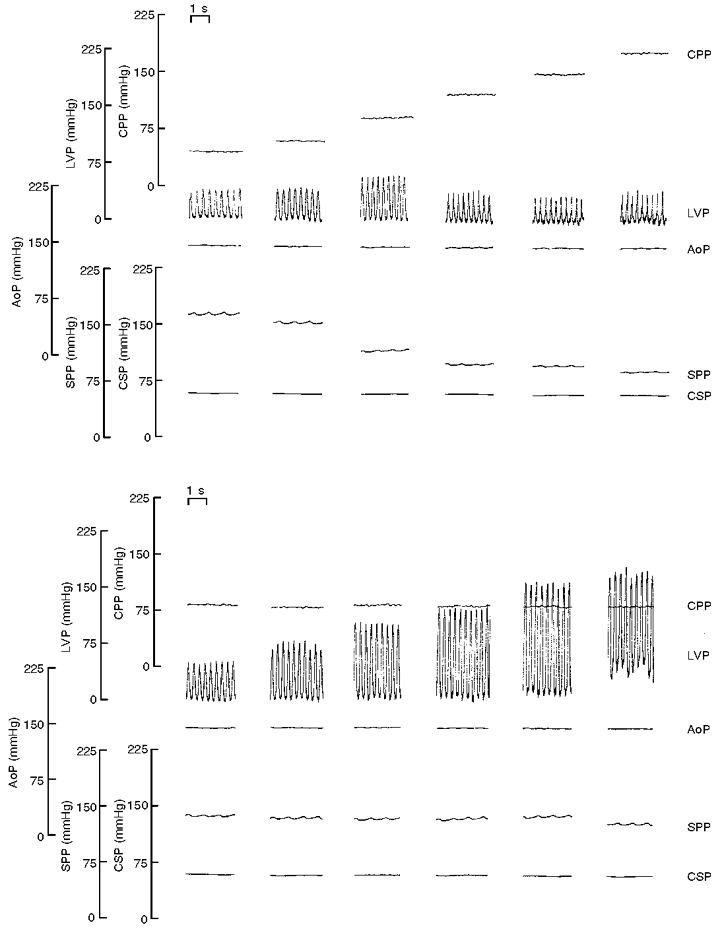

Figure 3 shows original traces comparing responses to the various stimuli. Increases in ventricular systolic pressure were always accompanied by changes in end-diastolic pressure. The mean change in diastolic pressure associated with the maximal change in systolic pressure was from 7.6 ± 0.8 to 29 ± 3.4 mmHg. The average responses to the four stimuli are compared in Fig. 4A. This emphasises that the changes in vascular resistance to stimulation of carotid, ventricular chemosensitive afferents and coronary arterial receptors were all very similar. The responses to changes in ventricular pressures, however, were much smaller.

Figure 3. Comparison of responses to stimulation of mechanoreceptors or the coronary chemoreflex.

The top traces compare the systemic responses to coronary (left), carotid (middle) and left ventricular (right) mechanoreceptor stimulation. In the same animal, the systemic response to intracoronary injection of veratridine is also shown (bottom traces). Traces are shown of coronary perfusion pressure (CPP), left ventricular pressure (LVP), aortic pouch pressure (AoP), carotid sinus pressure (CSP) and systemic perfusion pressure (SPP).

Figure 4. Comparison of resistance (A) and heart rate (B) responses to increases in carotid sinus (□), coronary arterial (▪) and ventricular systolic pressures ( ) between 60 and 180 mmHg, and also aortic root injections of veratridine (

) between 60 and 180 mmHg, and also aortic root injections of veratridine ( ).

).

Resting levels of heart rate prior to the stimulation of carotid, coronary and ventricular chemo- and mechanoreceptors were 163 ± 6, 164 ± 5, 177 ± 11 and 180 ± 7 beats min−1, respectively. Values are means ±s.e.m. for a total of 26 dogs, with numbers for each test shown in parentheses. Levels of significance (one-way ANOVA) were: *P < 0.001, when vascular responses to carotid and coronary distension, and the coronary chemoreflex, were compared with those resulting from ventricular distension; **P < 0.001, when the coronary chemoreflex heart rate response was compared with carotid, coronary and ventricular mechanoreceptor responses; †P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05, when comparing the heart rate responses from carotid and ventricular mechanoreceptor stimulation with those resulting from coronary mechanoreceptor stimulation, respectively.

The effects of the four stimuli on cardiac rate were very different (see Fig. 4B). Stimulation of carotid baroreceptors and ventricular chemosensitive afferents caused significant decreases in heart rate, although the response to the chemical stimulation was considerably larger. Stimulation of coronary baroreceptors tended to increase heart rate, but not significantly (P > 0.05), whereas increases in ventricular pressure induced small decreases in heart rate (P < 0.005, Student’s paired t test).

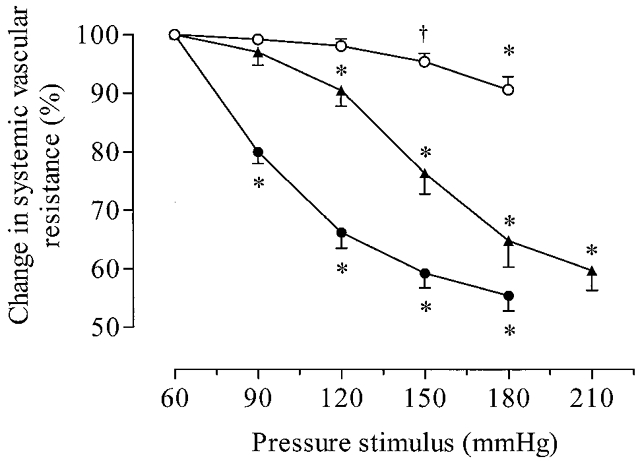

Responses to graded changes in pressure to the three mechanosensitive regions

In 17 animals, pressures were changed in 30 mmHg steps from 60 to 180 mmHg in each of the three regions. Figure 5 shows examples of original traces comparing responses to changes in coronary and ventricular pressures and emphasises the small vascular responses obtained when only ventricular pressures were changed. The responses to changes in pressure to all three regions are summarised in Fig. 6. The most striking finding was the very low pressure required to induce responses from coronary receptors, with the largest response occurring to the lowest pressure step tested. Responses to changes in ventricular pressure only became significant at the two highest pressure steps tested and these were associated with a large increase in end-diastolic pressure. Changes in ventricular and carotid sinus pressure decreased heart rate from 179 ± 8 to 172 ± 8 beats min−1 (−7 ± 2; P < 0.005) and 176 ± 12 to 147 ± 11 beats min−1 (−29 ± 6; P < 0.05, Student’s paired t test), respectively. However, no significant (P > 0.05) effect was observed to the change in coronary pressure, which increased slightly from 163 ± 5 to 167 ± 6 beats min−1 (+4 ± 5).

Figure 5. Reflex responses to stepwise changes in coronary pressure (top traces) or ventricular pressure (bottom traces) in the same dog.

Traces are shown of coronary perfusion pressure (CPP), left ventricular pressure (LVP), systemic arterial perfusion pressure (SPP), aortic pouch pressure (AoP) and carotid sinus pressure (CSP). Note that the magnitudes of the changes in systemic perfusion pressure to changes in coronary pressure were larger than those to changes in ventricular pressure, and that responses were obtained at lower coronary pressures. Pressures distending the carotid and aortic baroreceptors were held constant throughout these tests.

Figure 6. Responses of systemic vascular resistance to stepwise increases in coronary (•) and left ventricular pressure (○), in 17 dogs.

In four of these dogs, responses resulting from a change in carotid sinus pressure (▴) are shown. Under resting conditions, values of systemic perfusion pressure were: carotid, 152.8 ± 13.7 mmHg; coronary, 179.7 ± 8.2 mmHg; ventricular mechanoreflex, 144.4 ± 7.8 mmHg. Note that the ventricular mechanoreflex only induced a significant change in vascular resistance when ventricular systolic pressure increased to 150 mmHg, and end-diastolic pressure to 18.2 ± 1.6 mmHg. In contrast, significant decreases were observed at 120 and 90 mmHg during the carotid and coronary mechanoreceptor reflexes. Values are means ±s.e.m.†P < 0.05 and *P < 0.01 when comparing responses with control values (repeated measures ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in which the stimuli to coronary and left ventricular receptors were adequately separated and the pressures changed to each region independently. In our earlier report (Al-Timman et al. 1993) we achieved a degree of separation by use of a partial left ventricular bypass and limiting aortic ejection by applying a high pressure to the aortic root. These experiments provided good evidence that changes in aortic root and coronary pressure did induce reflex responses, but did not fully demonstrate the contribution from ventricular receptors. This was partly because responses could only be studied when aortic root pressure was sufficiently high that the valve remained closed. The peripheral circulation would therefore have been reflexively dilated, thus making further dilator responses difficult to obtain. The other limitation of preparations in which the ventricular outflow was open is that even at high aortic pressures, increases in ventricular pressure resulted in some ejection during systole and, although mean aortic pressure could be controlled, the pulse pressure could not. This implies that part of the effect of changes in ventricular systolic pressure might have been due to changes in aortic root, and therefore coronary pulse pressure. The present study effectively resolves this problem because the ejection through the aortic valve was prevented by the inflation of a small balloon catheter at the level of the aortic orifice.

There are a number of constraints imposed by the techniques used in the present study that need to be considered. The use of a balloon may have influenced the stimulus to some ventricular mechanoreceptors near the outflow tract. We do not, however, consider that this is a major problem because of the small size of the balloon (2–3 ml) and the fact that its position remained constant throughout the procedures. Although the balloon effectively obstructed ventricular outflow, it would not have influenced coronary blood flow as it was always at the ventricular side of the aortic valve. During all the various reflex tests we aimed to keep the stimuli to the regions not being tested close to threshold to ensure maximal vasoconstriction prior to inducing vasodilatation. Thus carotid and ventricular systolic pressures were maintained at about 60 mmHg. However, it was necessary to hold aortic pouch pressure at a high pressure (about 120 mmHg) because in the majority of experiments it determined pressure perfusing the cephalic region. Also, aortic root pressure was slightly elevated (about 85 mmHg), particularly during tests of ventricular pressure to ensure that coronary perfusion remained adequate. The consequence of this was that the control systemic perfusion pressure for the coronary pressure test, when coronary pressure started from a lower level, was higher than for the other tests. The effect of this is not likely to be very large but it may explain the slightly larger vascular response to the coronary pressure tests than the carotid tests.

The results of the experiments of changes in ventricular pressure show that the responses were even smaller than previously thought. Changes in pressures to either of the other two mechanosensitive regions (coronary and carotid regions) caused vascular responses about 5–7 times as great as those from ventricular receptors. Furthermore, ventricular mechanoreceptors only induced significant responses at abnormally high pressures (>150 mmHg) when end-diastolic pressure also started to increase steeply. These findings of reflex responses are entirely compatible with our electrophysiological study of afferent activity from ventricular mechanoreceptors (Drinkhill et al. 1993). Afferent activity in non-myelinated ventricular afferents only increased when systolic pressure increased in excess of 150–180 mmHg.

The experiments described in this study were performed in chloralose-anaesthetised dogs. Anaesthetics, in general, do affect the resting levels of vagal and sympathetic tone, but chloralose was chosen because it does not depress cardiovascular reflexes to the same extent as other anaesthetics such as halothane and sodium pentobarbitol (Halliwell & Billman, 1991; Watkins & Maixner, 1991). Responses of both vascular resistance and heart rate could be readily demonstrated to activation of carotid baroreceptors and ventricular chemosensitive nerves and it would therefore seem unlikely that anaesthesia could account for the smallness of responses from the ventricular mechanoreceptors.

The smallness of the responses from ventricular mechanoreceptors is also unlikely to have been due to damage to the innervation because, in all dogs in which it was tested, chemical stimulation of ventricular afferents induced both vasodilatation and bradycardia of a magnitude similar to that previously reported (−30.6 % and −50 beats min−1). The responses induced by the injection of veratridine are likely to have been due to stimulation of non-myelinated left ventricular receptors because Dawes (1947) found that when small doses of veratridine were injected into branches of the coronary arteries, it was only the supply to left ventricle that was effective in causing responses, whereas injection into arteries supplying the right ventricle and atrium had no effect.

It could also be argued that, by changing predominantly ventricular systolic pressure, we were not applying the most appropriate stimulus. It has been shown from action potential recordings that changes in diastolic pressure are more effective than changes in systolic pressure in changing the activity in ventricular afferent nerves (Thorén, 1977, 1979). Whilst in the present study we did not aim to change ventricular systolic and diastolic pressures independently, our results are entirely compatible with the earlier electrophysiological work. Reflex vasodilatation to increases in ventricular systolic pressure became significant only when there was a concomitant change in end-diastolic pressure. However, even at grossly elevated levels of both systolic and end-diastolic pressures, vascular resistance decreased by only about 10 %.

We believe this investigation is important for two main reasons: firstly, it confirms the existence of a potent reflex originating from mechanoreceptors in the coronary arteries, and secondly, it clearly demonstrates that physiological changes in both systolic and diastolic pressures in the left ventricle do not result in significant changes in vascular resistance.

Coronary arterial mechanoreceptors have the properties of arterial baroreceptors and, when considering the baroreceptor buffering capacity of the body it is necessary to consider not only the well-established carotid and aortic reflexes (see Heymans & Neil, 1958), but also the coronary baroreceptors. Our study has found coronary mechanoreceptors to be as potent as those in the carotid sinuses. However, there are also important differences. McMahon et al. (1996) compared the reflex responses to changes in pressure in the coronary arteries with those to changes in carotid and aortic pressure, and reported that the coronary reflex operated over a much lower pressure range than either of the other two reflexes. Also, although all three reflexes exerted qualitatively similar effects on vascular resistance, the coronary reflex alone had no significant effect on heart rate. We believe that it is very likely that much of the reflex activity that in earlier studies was attributed to the heart, particularly effects inferred from the effects of vagotomy (see Hainsworth, 1991), were actually due to coronary mechanoreceptors.

We need finally to consider what, if any, is the physiological role of ventricular receptors. Previous electrophysiological studies (Coleridge et al. 1964; Drinkhill et al. 1993) grouped non-myelinated afferents from the left ventricle into three categories: those with mechanosensitivity only, those with chemosensitivity only, and those with both. It is uncertain whether this is a true categorisation or whether mechanosensitive nerves were just not accessed by injected chemicals, and chemosensitive afferents not stimulated sufficiently by stretching. Whatever the effective stimulus is, it is clear that they are not strongly influenced by events occurring during normal life. Coleridge & Coleridge (1980) regard the non-myelinated afferents as playing a ‘protective’ rather than regulatory role. This seems quite plausible in that they seem only to induce responses during extreme stresses, such as very high ventricular pressures and volumes, or during altered chemical environments, as would occur during myocardial ischaemia. Their function, therefore, may be more concerned with pathophysiological situations rather than physiological control.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a studentship (FS/97075) from the British Heart Foundation and by the Medical Research Council (G9809405). The technical assistance of Mr D. Myers is also gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Al-Timman JKA, Drinkhill MJ, Hainsworth R. Reflex responses to stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the left ventricle and coronary arteries in anaesthetized dogs. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;472:769–783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviado DM, Schmidt CF. Cardiovascular and respiratory reflexes from the left side of the heart. American Journal of Physiology. 1959;196(suppl. 4):726–730. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM. The depressor reflex arising from the left coronary artery of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1966;184:825–836. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challenger S, McGregor KH, Hainsworth R. Peripheral vascular responses to changes in left ventricular pressure in anaesthetized dogs. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 1987;72:271–283. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1987.sp003074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier PA, Weber KC, Lyons GW, Nicoloff DM, Fox IJ. Hemodynamic changes from stimulation of left ventricular baroreceptors. American Journal of Physiology. 1974;227(suppl. 3):719–728. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JCG. Cardiovascular afferents involved in the regulation of peripheral vessels. Annual Review of Physiology. 1980;42:413–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.42.030180.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JCG, Kidd C. Cardiac receptors in the dog, with particular reference to two types of afferent ending in the ventricular wall. The Journal of Physiology. 1964;174:323–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly I de B, Verney EB. The localization of receptors involved in the reflex regulation of the heart rate. The Journal of Physiology. 1927;62:330–340. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1927.sp002363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes GS. Studies on veratrum alkaloids. VII. Receptor areas in the coronary arteries and elsewhere as revealed by the use of veratridine. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1947;89:325–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkhill MJ, Moore J, Hainsworth R. Afferent discharges from coronary arterial and ventricular receptors in anaesthetized dogs. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;472:785–799. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainsworth R. Reflexes from the heart. Physiological Reviews. 1991;71:617–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell JR, Billman GE. Effect of general anaesthesia on cardiac vagal tone. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;262:H1719–1724. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymans C, Neil E. In: Reflexogenic Areas of the Cardiovascular System. Little, Brown, editors. London: Churchill; 1958. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Hoka S, Bosnjak ZJ, Siker D, Luo R, Kampine JP. Dynamic changes in venous outflow by baroreflex and left ventricular distension. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:R212–221. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.254.2.R212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarisch A, Zotterman Y. Depressor reflexes from the heart. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1948;16:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MP, Baker DG, Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Stimulation by bradykinin of afferent vagal C-fibers with chemosensitive endings in the heart and aorta of the dog. Circulation Research. 1980;46:476–484. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton FP, Starling EH. The influence of variations in temperature and blood pressure on the performance of the isolated mammalian heart. The Journal of Physiology. 1912;44:206–219. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1912.sp001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor KH, Hainsworth R, Ford R. Hindlimb vascular responses in anaesthetized dogs to aortic root injections of veratridine. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 1986;71:577–587. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1986.sp003018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon NC, Drinkhill MJ, Hainsworth R. Reflex vascular responses from aortic arch, carotid sinus and coronary baroreceptors in the anaesthetized dog. Experimental Physiology. 1996;81:397–408. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark AL, Abboud FM, Schmid PG, Heistad DD, Johannsen UJ. Reflex vascular responses to left ventricular outflow obstruction and activation of ventricular baroreceptors in dogs. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1973;52:1147–1153. doi: 10.1172/JCI107281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Frahm CJ, Braunwald E. The influence of intrathoracic baroreceptors on venous return, systemic vascular volume and peripheral resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1961;40:563–572. doi: 10.1172/JCI104284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury PF, Cross CE, Rieben PA. Reflex effects of left ventricular distension. Circulation Research. 1960;8:530–534. doi: 10.1161/01.res.8.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames MD, Donald DE, Shepherd JT. Behaviour of cardiac receptors with non-myelinated vagal afferents during spontaneous respiration in cats. Circulation Research. 1977;41:694–701. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorén PN. Characteristics of left ventricular receptors with non-medullated vagal afferents in cats. Circulation Research. 1977;40:415–421. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorén PN. Reflex effects of left ventricular mechanoreceptors with afferent fibers in the vagal nerves. In: Hainsworth R, Kidd C, Linden RJ, editors. Cardiac Receptors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1979. pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bezold AV, Hirt L. Über die physiolischen Wirkungendes essigsauren Veratrins. In: Von Bezold AV, editor. Untersuchungen aus dem physiologischen Laboratorium in Würzberg. Vol. 1. Leipzig: Engelmann; 1867. pp. 75–156. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins L, Maixner W. The effect of pentobarbitol anaesthesia on the autonomic nervous system control of heart rate during baroreceptor activation. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1991;36:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(91)90106-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelis R, Lotysh M, Brais M, Peng CL, Hurley E, Mason DJ. Effects of isolated right and left ventricular stretch on regional arteriolar resistance. Cardiovascular Research. 1977;11:419–426. doi: 10.1093/cvr/11.5.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]