Abstract

A field study of a vaccine; prepared by solubilizing cells infected with bovine coronavirus, Triton X-100, and mixing with an oil adjuvant, was performed at 9 farms over 4 prefectures. The cattle tested were Holstein dairy cows aged 2 to 10 years. A vaccination group consisted of 157 animals (including 132 pregnant cows) and a non-vaccinated control group consisted of 50 animals. The cows received 2 intramuscular injections of vaccine (2 mL) at 3-week intervals. Vaccinated cows did not develop abnormalities, such as a decrease in milk production volume, and all pregnant animals calved normally. The geometric mean of the hemagglutination inhibition antibody titer was 34.2 before vaccination in test cows. The titer had increased to 105.6, 3 weeks after the 1st injection and peaked at 755.6, 1 month after the 2nd injection. A high antibody titer persisted at 396.0; 241.0; and 201.5, at 3, 6, and 9 months after the 2nd injection, respectively.

This confirms the safety and high antibody-response induced by this prototype vaccine. Therefore, this vaccine may be useful for the prevention of winter dysentery caused by bovine coronavirus infection.

Bovine coronavirus (BCV) infection causes epidemics of acute diarrhea in calves and adult cattle (1,2,3,4,5). A mixed infection of bovine rotavirus and cryptosporidium can be fatal to calves (5,6,7). Decreases in milk production in dairy cows with BCV can result in serious economic losses (2,3,8).

To prevent this disease, vaccines have been developed in the United States, Germany, and Spain (1,9,10,11), but their efficacy is questionable (9,12,13). Moreover, these vaccines are for calves, not for adult cattle. To prevent BCV-induced diarrhea in adult cattle, we have prepared a solubilized antigen from BCV-infected cells and developed a vaccine by combining the soluble antigen with an oil adjuvant. A high antibody response and prevention of infection was confirmed in a previous study (14). In this study, we investigated the safety and efficacy of the vaccine using dairy cows in the field.

The BCV 66/H strain has been used to prepare vaccines and as an antigen for hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays. This virus was isolated from the feces of a naturally infected calf using bovine kidney cell cultures in 1977. It was passaged 9 times in the same cells, then 6 times in BEK-1 cells (derived from bovine fetal kidney), and then 3 times in HAL cells (derived from mature hamster lung). The vaccine was prepared as described in our previous report (14). Briefly, HAL cells were inoculated with the virus and cultured at 37°C. At the time the maximal cytopathic effect (CPE) appeared, 2 to 3 d after inoculation, the infected cells were mixed with a 10 fold volume of 0.01 M glycine and 0.038 M Tris-aminomethane containing 0.1% Triton X-100. A 10% detergent-removing gel (Extracti-Gel D; Pierce Chemical, Rockford, Illinois, USA) was added to the supernatant (solubilized antigen solution) and Triton X-100 was removed by stirring the mixture at room temperature for 4 h. After centrifugation at 3000 rotations per minute (rpm) for 15 min, the supernatant was mixed with 0.05% formalin and kept at 4°C for 1 wk to inactivate the residual virus. Oil adjuvant (liquid paraffin containing 10% anhydrous mannitol-oleic acid ester) was added to emulsify the inactivated supernatant. The emulsion was prepared as water in oil. The hemagglutination (HA) titer was determined according to standard methods using 1% rat erythrocytes. The HA titer of the solubilized antigen solution was 16 000 fold.

The field experiment was performed in 1999 and 2000 at 9 farms in Kochi, Ehime, Mie, and Kyoto prefectures in Japan. A total of 207 Holstein dairy cows (aged 2 to 10 y), raised on 9 farms (14 to 40 head each), were used. The cows were randomly allotted to either a vaccine group (157) or a control group (50) at a 3 to 1 ratio. Among the vaccinated cows, 132 were pregnant (3 to 7 mo of gestation). Cows within 10 d of term were excluded from the experiment. For vaccination, 2 mL of the vaccine was intramuscularly injected twice at 3-week intervals. The general symptoms (lethargy, poor appetite, respiratory symptoms, and diarrhea) and local response at the injection site were observed for 14 d after vaccination. The milk yield during the 3-day period before vaccination was compared with that during the 14-day period after vaccination at each farm, and the effect of vaccination on milk production was investigated. In pregnant cows, the delivery state was also examined. Blood samples were collected and the HI antibody titer was measured before the 1st injection; 3 wk after the 1st injection (at the time of the 2nd injection); and 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo after the 2nd injection. The serum neutralizing (SN) antibody titer was measured in samples (20) taken at vaccination and 1 mo after the 2nd injection. Both antibody titers were determined as reported (14).

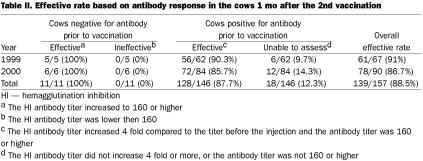

The effect of the vaccine was evaluated based on the response of the HI antibody, as reported previously (14). The vaccine was considered effective when the HI antibody titer was 160 or higher 1 mo after the 2nd injection in cows that were negative for HI antibody (titer 10 or below) prior to injection. In cows that were HI antibody-positive (titer 10 or higher) prior to vaccination, the vaccine was judged as effective when the antibody titer was increased 4 fold, or more, 1 mo after the 2nd injection, as well as when the titer was at least 160-fold higher.

With regard to the safety of the vaccine, there was no clinical abnormality or local response at the injection site of any vaccinated cow. All cows that were pregnant at the time of vaccination calved normally. The milk yield did not change for 3 d prior to injection, or for 14 d after the 1st and 2nd vaccination on any farm. The safety of this vaccine was confirmed.

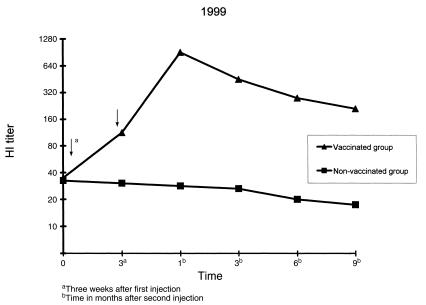

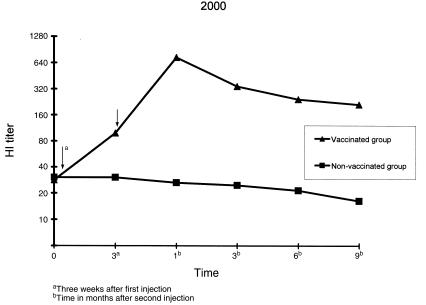

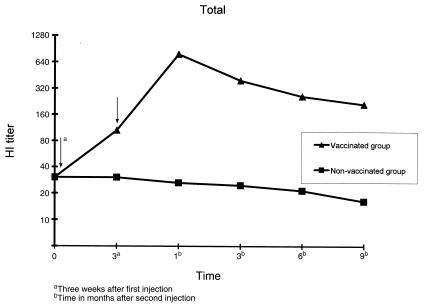

The effect on disease prevention could not be investigated because there was no incidence of BCV infection-induced diarrhea during the experimental period in the vaccinated and control cows at each farm. However, the HI antibody titer increased in the vaccinated group. The geometric mean of the HI antibody titer for all vaccinated cows was 34.2 before the 1st injection. The titer increased to 105.6 at 3 wk after the 1st injection. The highest titer, 755.6, was reached 1 mo after the 2nd injection. The titer then gradually decreased to 396.0, 241.0, and 201.5 at 3, 6, and 9 mo after the 2nd injection, respectively, showing a persistent high antibody response. The HI antibody titer did not increase in the control cows during the study period (Figures 1, 2, 3). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test whether responses were similar on the 9 farms and among the age groups (2 to 10 y). Neither factor was significant (P > 0.05).

Figure 1. Changes in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer (geometric mean) in vaccinated and non-vaccinated cows in 1999. Field experiments were performed at 6 farms in 1999 using 89 Holstein dairy cows (67 vaccinated, 22 non-vaccinated). For vaccination 2 mL of the vaccine was injected intramuscularly twice at 3-week intervals. Blood samples were collected before the 1st injection, 3 wk after the 1st injection, and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo after the 2nd injection. The HI titers of vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups are described by geometric mean.

Arrow — vaccination date.

Figure 2. Changes in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer (geometric mean) in vaccinated and non-vaccinated cows in 2000. Field experiments were performed at 3 farms in 2000 using 118 Holstein dairy cows (90 vaccinated, 28 non-vaccinated). For vaccination 2 mL of the vaccine was injected intramuscularly twice at 3-week intervals. Blood samples were collected before the 1st injection, 3 wk after the 1st injection, and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo after the 2nd injection. The HI titers of vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups are described by geometric mean.

Arrow — vaccination date.

Figure 3. Changes in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer (geometric mean) in vaccinated and non-vaccinated cows in 1999 and 2000. Field experiments were performed at 9 farms in 1999 and 2000 using 207 Holstein dairy cows (157 vaccinated, 50 non-vaccinated). For vaccination 2 mL of the vaccine was injected intramuscularly twice at 3-week intervals. Blood samples were collected before the 1st injection, 3 wk after the 1st injection, and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 mo after the 2nd injection. The HI titers of vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups are described by geometric mean.

Arrow — vaccination date.

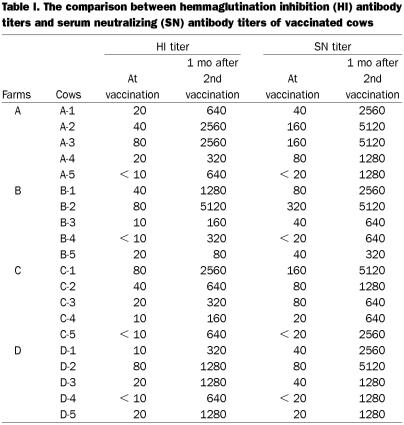

The response of the serum neutralizing (SN) antibody titer was examined in 20 samples at vaccination and 1 mo after the 2nd vaccination. The SN titers showed a strong response 1 mo later. A coefficient of correlation between the SN titers and HI titers was calculated. There was a major correlation (r = 0.95) (Table I). This result was similar to a previous finding (14).

Table I.

The effective rate of the vaccine 1 mo after the 2nd vaccination was 91% (61/67) in 1999 and 86.7% (78/90) in 2000. The overall rate was 88.5% (139/157) (Table II). Thus 88.5% of vaccinated cows achieved a sufficient level of herd immunity 1 mo after the 2nd injection.

Table II.

Waltner-Toews et al (12) reported that in a field study of a combined rotavirus, coronavirus, and Escherichia coli vaccine performed at 41 farms, the vaccine was not effective in preventing diarrhea or mortality in calves. Collins et al (13) vaccinated dairy cows in a field with the above vaccine, and found no differences in neutralizing antibody production between vaccinates and non-vaccinates. In addition, Myers et al (9) reported that differences in colostral and milk antibody titers, between cows vaccinated with a modified live rotavirus and coronavirus vaccine and non-vaccinated cows, were not significant. In contrast to these studies, Thurber et al (15) showed that continuous vaccination of newborn calves with a modified live coronavirus and reovirus vaccine substantially reduced diarrhea associated with these agents. There is controversy as to whether these vaccines are useful for preventing disease. An in vitro method to assess efficacy of the vaccine is necessary.

In this study, the antibody response was good in the vaccinated cows, thus, the vaccine can be expected to prevent infection. The cause of this effect may be a high concentration of HA antigen (HA titer 16 000), which is a protective antigen for bovine coronavirus infection, and the composition of oil adjuvant. With its safety and high antibody productivity confirmed in the field, this vaccine may be useful for preventing winter diarrhea caused by BCV infection.

Footnotes

Address all correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Keizo Takamura; telephone: (+81) 774-22-4518; fax: (+81) 774-24-1407; e-mail: kblboad@kyotobiken.co.jp

Received November 16, 2001. Accepted April 30, 2002.

References

- 1.Mebus CA, Stair EL, Rhode MB, Twiehaus MJ. Neonatal calf diarrhea: Propagation, attenuation, and characteristics of a coronavirus-like agent. Am J Vet Res 1973;34:145–150. [PubMed]

- 2.Saif LJ, Redman DR, Brock KV, Kohler EM, Heckert RA. Winter dysentery in adult dairy cattle: Detection of coronavirus in the faeces. Vet Rec 1988;123:300–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Taniguti S, Iwamoto H, Fukuura H, Ito H, Gekai N, Nagato Y. Recurrence of bovine coronavirus infection in cows. J Jpn Vet Med Assoc 1986;39:298–302.

- 4.Tsunemitsu H, Yonemichi H, Hirai T, et al. Isolation of bovine coronavirus from feces and nasal swabs of calves with diarrhea. J Vet Med Sci 1991;53:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Woode GN, Bridger JC. Viral enteritis of calves. Vet Rec 1975; 25:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Reynolds DJ, Morgan JH, Chanter N, et al. Microbiology of calf diarrhoea in southern Britain. Vet Rec 1986;119:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Snodgrass DR, Terzolo HR, Sherwood D, Campbell I, Menzies JD. Aetiology of diarrhoea in young calves. Vet Rec 1986;119: 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Takahashi E, Inaba Y, Sato K, et al. Epizootic diarrhea of adult cattle associated with a coronavirus-like agent. Vet Microbiol 1980;5:151–154.

- 9.Myers LL, Snodgrass DR. Colostral and milk antibody titers in cows vaccinated with a modified live-rotavirus-coronavirus vaccine. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1982;181:486–488. [PubMed]

- 10.Freitag H, Wetzel H, Espenkoetter E. Prophylaxis of diarrhoea due to rotavirus and coronavirus in calves. Tierarztl Umsch 1984;39:731–734.

- 11.Garcfa Sánchez J, Muzquiz JL, Gironés O, Halaihel NG. Immunization against bovine rotavirus and coronavirus in pregnant cows. II. Antibody titers in the mammary secretion of vaccinated animals. III. Antibody titers in the blood serum of the calves. Veterinaria 1991;8:217–224,289–298.

- 12.Waltner-Toews D, Martin SW, Meek AH, McMillan I, Crouch CF. A field trial to evaluate the efficacy of a combined rotavirus-coronavirus/Escherichia coli vaccine in dairy cattle. Can J Comp Med 1985;49:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Collins JK, Riegel CA, Olson JD, Fountain A. Shedding of enteric coronavirus in adult cattle. Am J Vet Res 1987;48:361–365. [PubMed]

- 14.Takamura K, Okada N, Ui S, Hirahara T, Shimizu Y. Protection studies on winter dysentery caused by bovine coronavirus in cattle using antigens prepared from infected cell lysates. Can J Vet Res 2000;64:138–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Thurber ET, Bass EP, Beckenhauer WH. Field trial evaluation of a reo-coronavirus calf diarrhea vaccine. Can J Comp Med 1977;41:131–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed]