Abstract

Glucose-induced insulin secretion is determined by signals generated in the mitochondria. The elevation of ATP is necessary for the membrane-dependent increase in cytosolic Ca2+, the main trigger of insulin exocytosis. Beta cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA fail to respond to glucose while still secreting insulin in response to membrane depolarisation. This cell model resembles the situation of defective insulin secretion in patients with mitochondrial diabetes. On the other hand, infants with activating mutations in the mitochondrial enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase are characterised by hyperinsulinism and hypoglycaemia. We have recently proposed that glutamate, generated by this enzyme, participates in insulin secretion as a glucose-derived metabolic messenger. In this model, glutamate acts downstream of the mitochondria by sensitising the exocytotic process to Ca2+. The evidence in favour of such a role for glutamate is discussed in the present review.

Blood glucose homeostasis depends on the normal regulation of insulin secretion from the pancreatic beta cells and on the biological action of the hormone on its target tissues. Most forms of type 2 diabetes display disregulation of insulin secretion combined with insulin resistance. Insulin secretion is stimulated not only by glucose but also by leucine and other amino acids (for review, see Wollheim, 2000). Nutrient-induced secretion is potentiated by the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP), as well as by the gastrointestinal hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) (reviewed by Ahren, 2000). These and other factors, including fatty acids, all participate in the physiological stimulation of insulin secretion. For instance, knock-out of the GIP receptor in the mouse leads to glucose intolerance (Miyawaki et al. 1999). In addition, insulin exocytosis is under the direct negative control of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and somatostatin (Lang et al. 1995; Sharp, 1996; Ahren, 2000).

Signal generation by glucose

The beta cell is poised to adapt rapidly the rate of insulin secretion to fluctuations in the blood glucose concentration. Glucose equilibrates across the plasma membrane and is phosphorylated by glucokinase, which determines the rate of glycolysis and the generation of pyruvate (see Newgard & McGarry, 1995). High rates of glycolysis are maintained through the activity of mitochondrial shuttles, mainly the glycerophosphate and malate/aspartate shuttles (MacDonald, 1981; Eto et al. 1999), which allow the reoxidation of cytosolic NADH. Other shuttles generating cytosolic NADPH have also been described (MacDonald, 1995; Farfari et al. 2000). As demonstrated in isolated purified beta cells, as much as 90 % of glucose-derived carbons are oxidized by the mitochondria (Schuit et al. 1997). This is favoured by the very low expression of monocarboxylate transporters in the plasma membrane coupled with low activity of lactate dehydrogenase (Sekine et al. 1994; Ishihara et al. 1999; reviewed in Ishihara & Wollheim, 2000). Pyruvate, once transported into the mitochondria, is a substrate both for pyruvate dehydrogenase and pyruvate carboxylase. These enzymes ensure, respectively, the formation of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. The latter provides anaplerotic input to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Schuit et al. 1997; Farfari et al. 2000). Through activation of the TCA cycle, reducing equivalents are transferred to the electron transport chain resulting in hyperpolarisation of the mitochondrial membrane (ΔΨm) and generation of ATP. In addition to pyruvate dehydrogenase, two TCA cycle enzymes, isocitrate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, are activated by Ca2+ (reviewed by Duchen, 1999). In the consensus model of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, mitochondrial metabolism increases the cytosolic ATP/ADP ratio. This leads to closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) and depolarisation of the plasma membrane. As a consequence, the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) is raised by the opening of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (see Rorsman, 1997). The increase in [Ca2+]c is the main trigger for exocytosis, the process by which the insulin-containing secretory granules fuse with the plasma membrane (Lang, 1999). In glucose-stimulated beta cells both the [Ca2+]c rises and the insulin secretion are biphasic with a transient first phase and a second, sustained phase (Bergsten, 1995; Kennedy et al. 1996).

The Ca2+ signal in the cytosol is necessary but not sufficient for the full development of biphasic insulin secretion. It was first shown in 1992 that glucose elicits secretion under conditions of clamped, elevated [Ca2+]c (Gembal et al. 1992; Sato et al. 1992). The importance of this KATP-independent pathway is illustrated by mouse models lacking functional KATP following the knock-out of either of the two subunits of the channel (Miki et al. 1998; Seghers et al. 2000). The beta cells of these animals show spontaneous increases in [Ca2+]c and glucose is still able to cause limited insulin secretion. Thus, both the KATP-dependent and -independent insulin secretion require mitochondrial metabolism (Detimary et al. 1994).

Mitochondrial diabetes

Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, or type 2 diabetes, is a polygenic disease characterised by impaired insulin secretion (Porte, 1991) often combined with insulin resistance (Kahn, 1998). A subform of type 2 diabetes referred to as maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) has been linked to mutations in the mitochondrial genome. These mutations involve deletions or point mutations, e.g. in tRNALeu(UUR) at position 3243 also giving rise to mitochondrial myoencephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) (Maassen & Kadowaki, 1996). In MIDD there is a progressive impairment of insulin secretion, which may eventually lead to severe insulin deficiency reminiscent of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. The clinical picture of these patients illustrates the well-known dependency of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion on mitochondrial function. It was already demonstrated three decades ago that mitochondrial poisons inhibit the effect of glucose (Hellman, 1970).

In vitro models of mitochondrial diabetes

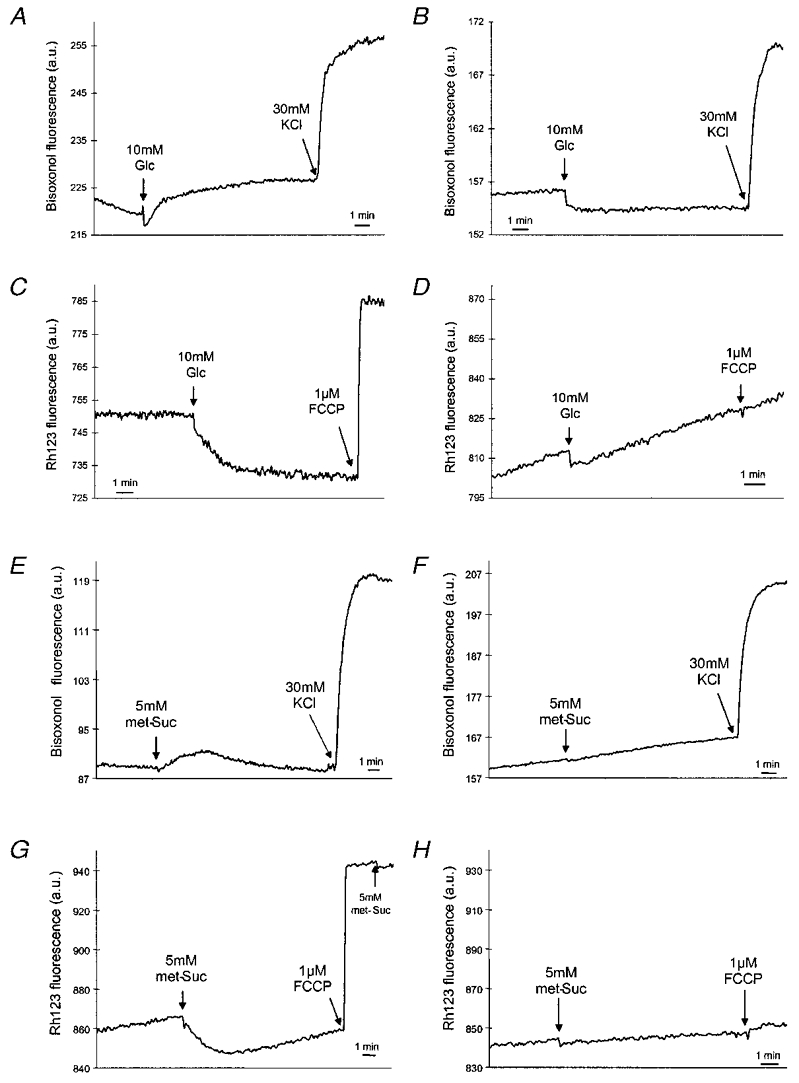

Patients with mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) display heteroplasmy, i.e. mitochondria within the same cells harbour both normal and mutated forms of the multicopy mtDNA. Autopsy of a mitochondrial diabetic with the 3243 mtDNA point mutation revealed much higher heteroplasmy (63 %) in beta cells compared with other cell types (Kobayashi et al. 1997). The mutated mtDNA could be enriched in engineered cell lines by fusing patient-derived enucleated skin fibroblasts with a mtDNA depleted human cell line. After selection, such cybrids carry nearly 100 % of either mutated or wild-type mtDNA. These cells with mutated mtDNA exhibited grossly altered morphology of the mitochondria and severely decreased oxygen consumption (van den Ouweland et al. 1999). Unfortunately, the mitochondria of patient origin cannot be introduced into human beta cells for the study of stimulus-secretion coupling, as human insulin-secreting cell lines are not yet available. By contrast, the mtDNA of several rodent beta cell lines has been depleted by chemical treatment resulting in so-called ρ° cells. In rat insulinoma INS-1 cells mtDNA depletion also resulted in altered mitochondrial morphology and inhibition of glucose-stimulated ATP production (Kennedy et al. 1998). The latter explains why glucose does not depolarise the plasma membrane potential in INS-1 ρ° cells (Fig. 1B) compared with the depolarisation seen in control INS-1 cells (Fig. 1A). The deficient ATP generation and membrane depolarisation are secondary to the impaired activation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This is reflected in the absence of hyperpolarisation of ΔΨm normally seen in control cells (Fig. 1C and D). Similar results were obtained with the membrane-permeant mitochondrial substrate methyl-succinate (Fig. 1E-H), which mimics the effect of glucose on insulin secretion (Maechler et al. 1997). This suggests that mitochondrial metabolism rather than glycolysis is defective in ρ° cells. As expected from these results, glucose does not increase [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in different ρ° beta cell line preparations (Soejima et al. 1996; Kennedy et al. 1998; Tsuruzoe et al. 1998; Hayakawa et al. 1998). These ρ° cells still synthesise, store and secrete insulin as demonstrated by insulin secretion in response to the [Ca2+]c raising agents KCl and glibenclamide, which do not require mitochondrial metabolism (Kennedy et al. 1998; Tsuruzoe et al. 1998; Hayakawa et al. 1998). Replenishment of MIN-6 ρ° cells with normal mitochondria from mouse fibroblasts completely restored glucose-stimulated insulin secretion as shown in an elegant study by Soejima et al. (1996). Taken together, these results emphasise the crucial role of the mitochondria in the generation of metabolic coupling factors in glucose-induced insulin release.

Figure 1. Plasma membrane potential and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in INS-1 and INS-1 ρ° cells.

Suspensions of cells were loaded either with the fluorescent probe bisoxonol to monitor plasma membrane potential in INS-1 (A and E) or INS-1 ρ° cells (B and F) or with Rh123 to monitor ΔΨm in INS-1 (C and G) or INS-1 ρ° cells (D and H). met-Suc, methyl-succinate. Reproduced from Kennedy et al. (1998), with permission.

Mitochondrially driven insulin exocytosis

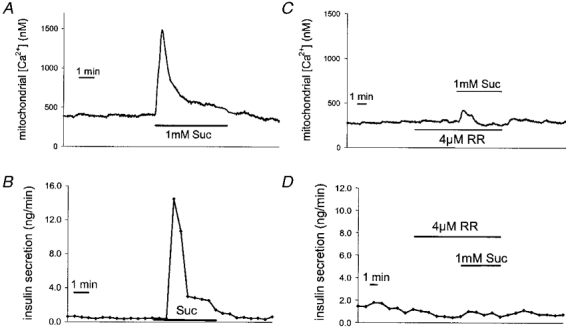

Numerous studies have sought to identify the factor(s) mediating the KATP-independent effect of glucose on insulin secretion. Neither protein kinase A nor protein kinase C appeared to be implicated. Malonyl-CoA has been proposed as a metabolic coupling factor in insulin secretion (Prentki et al. 1992), being a messenger derived from citrate generated in the mitochondria (Farfari et al. 2000). However, disruption of malonyl-CoA accumulation during glucose stimulation did not affect the secretory response (Antinozzi et al. 1998), leaving the debate open as to the role of long chain acyl-CoA as a coupling factor (see Corkey et al. 2000). In order to study the link between mitochondrial activation and insulin exocytosis, we have established a Staphylococcusα-toxin-permeabilised beta cell model permitting the clamping of [Ca2+]c and nucleotides such as ATP. This preparation can be directly stimulated with various mitochondrial substrates including succinate, a TCA cycle intermediate. Three mitochondrial dehydrogenases are known to be activated by Ca2+ in various tissues (Denton & McCormack, 1980; Hansford, 1985), including insulin-secreting cells (Sener et al. 1990; Civelek et al. 1996; Maechler et al. 1998). Therefore, the increase in [Ca2+]m conveniently reflects mitochondrial activation (Rizzuto et al. 1992; Duchen, 1999). To monitor mitochondrial activation, we measured mitochondrial free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]m) using INS-1 cells stably expressing the Ca2+-sensitive photoprotein aequorin (Kennedy et al. 1996) with simultaneous assessment of insulin secretion. When the [Ca2+]c was clamped at 500 nM, succinate caused a marked biphasic increase in [Ca2+]m (Fig. 2A), an effect secondary to hyperpolarisation of ΔΨm (Maechler et al. 1997). This mitochondrial activation resulted in biphasic insulin release (Fig. 2B). As Ca2+ enhances succinate oxidation under these conditions (Maechler et al. 1998), it can be concluded that mitochondrial activation directly stimulates insulin exocytosis. The obvious question is whether the increase in [Ca2+]m is required for the action of succinate on insulin secretion. To test this, Ruthenium Red, an inhibitor of Ca2+ uptake through the mitochondrial uniporter, was applied. Ruthenium Red attenuated the [Ca2+]m rise and abolished insulin release induced by succinate (Fig. 2C and D). A [Ca2+]m rise is thus necessary for the mitochondrially driven insulin exocytosis, but Ca2+ is not sufficient. Indeed, the sole [Ca2+]m elevation without provision of carbons to the TCA cycle (anaplerosis) failed to elicit insulin secretion under these conditions (Maechler et al. 1997). This strongly suggested the existence of a mitochondrial factor generated through anaplerotic input into the TCA cycle.

Figure 2. Effects of the TCA cycle intermediate succinate on [Ca2+]m and insulin secretion in permeabilised INS-1 cells.

Cells expressing the Ca2+-sensitive photoprotein aequorin targeted to the mitochondria were permeabilised with α-toxin and perifused with an intracellular buffer containing 500 nM free Ca2+ and high ATP (10 mm). The effects of succinate (Suc) on [Ca2+]m (A) and insulin secretion (B) were measured simultaneously. Influx of Ca2+ into the mitochondria via the uniporter was blocked using Ruthenium Red (RR) before the addition of Suc during the measurement of [Ca2+]m (C) and insulin secretion (D). Modified with permission from Maechler et al. (1997).

Is glutamate the mitochondrially derived coupling factor?

Using the α-toxin-permeabilised cell model, metabolic intermediates of mitochondrial origin were screened for their putative direct action on insulin exocytosis. These and other experiments suggested glutamate as the coupling factor. Glucose increased the cellular glutamate content in INS-1 cells and human islets (Maechler & Wollheim, 1999). In rat islets Tamarit-Rodriguez et al. (2000) reported that glutamate was the only amino acid out of twelve that increased during glucose stimulation, whereas aspartate decreased. Using a similar islet preparation MacDonald & Fahien (2000) did not observe any changes in glutamate levels. In incubated mouse islets, glucose did not augment glutamate (Danielsson et al. 1970). Thus, conflicting data emanate from different laboratories regarding the effect of glucose on glutamate levels. This discrepancy might be explained by culture conditions that can substantially increase the background of glutamate, especially in the case of whole islets constituted of a mixture of beta and non-beta cells (Michalik et al. 1992). Basal total glutamate levels range from sub-millimolar in INS-1 cells to millimolar in the islet preparations (Danielsson et al. 1970; Michalik et al. 1992; MacDonald & Fahien, 2000). These data obtained in whole cells do not yield information on changes in the cytosol, the critical compartment for a putative messenger molecule, since mitochondria and possibly secretory granules contain glutamate. In isolated INS-1 cell mitochondria, succinate generates glutamate under conditions in which insulin secretion is stimulated in permeabilised cells (Maechler et al. 2000). Using a mannitol-sucrose buffer, unfortunately without a set Ca2+ concentration, MacDonald & Fahien (2000) did not observe this effect of succinate in rat islet mitochondria.

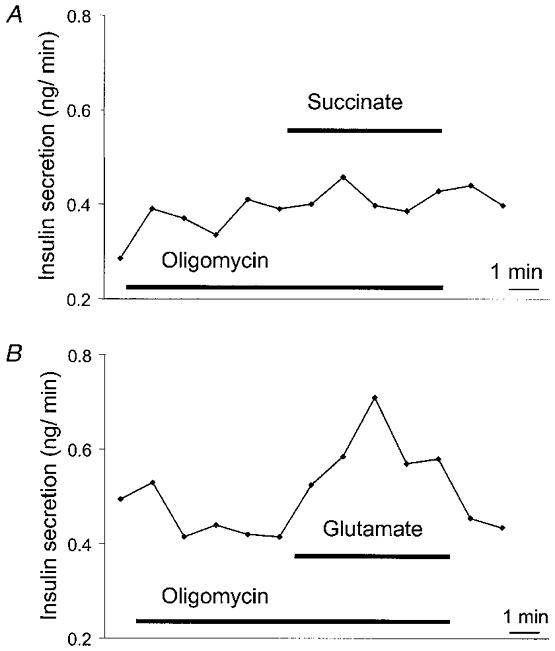

Irrespective of the glutamate levels measured in glucose-stimulated cells, the principal observation is that glutamate directly stimulates insulin exocytosis in permeabilised cells at permissive [Ca2+]c independently of mitochondrial activation (Maechler & Wollheim, 1999). This was corroborated by addition to permeabilised cells of oligomycin, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial ATP synthase. Oligomycin abolished insulin release in response to succinate without affecting glutamate-induced exocytosis (Fig. 3A and B). These results suggest that glutamate, in contrast to succinate, acts downstream of mitochondrial metabolism. Finally, addition of the cell-permeant derivative diemethyl-glutamate to intact beta cell preparations only stimulates insulin secretion at intermediate but not at basal or optimal glucose concentrations (Sener et al. 1994; Maechler & Wollheim, 1999). Similarly, glutamine, which forms glutamate in the beta cell (Michalik et al. 1992), enhances insulin release only in the presence of other nutrient stimuli (Malaisse et al. 1980). The converging evidence favours the contention that intracellular glutamate requires other glucose-triggered signals, such as an increase in [Ca2+]c.

Figure 3. Effects of oligomycin on insulin secretion in permeabilised INS-1 cells.

Cells were permeabilised with α-toxin and perifused with an intracellular buffer at 500 nM [Ca2+]c and 1 mm ATP. Oligomycin (1 μg ml−1) suppresses the effect of succinate (1 mm, A) but not of glutamate (1 mm, B) on insulin secretion. Conditions as in Maechler & Wollheim (1999); the traces are representative of three independent experiments.

Role of glutamate in beta cell function

We thus postulate an intracellular messenger role for glutamate in stimulus-secretion coupling. Previously, extracellular glutamate was reported to cause a transient stimulation of insulin secretion in the perfused rat pancreas (Bertrand et al. 1992) and to elicit a small secretory response in isolated rat islets (Inagaki et al. 1995). It is noteworthy that only approximately 25 % of rat beta cells express glutamate receptors (Weaver et al. 1996) and that glutamate does not elicit insulin release in intact rat islets (Fahien et al. 1988) or INS-1 cells (authors’ unpublished observations). We therefore suggest that glutamate acts as an intracellular rather than an extracellular messenger in insulin exocytosis.

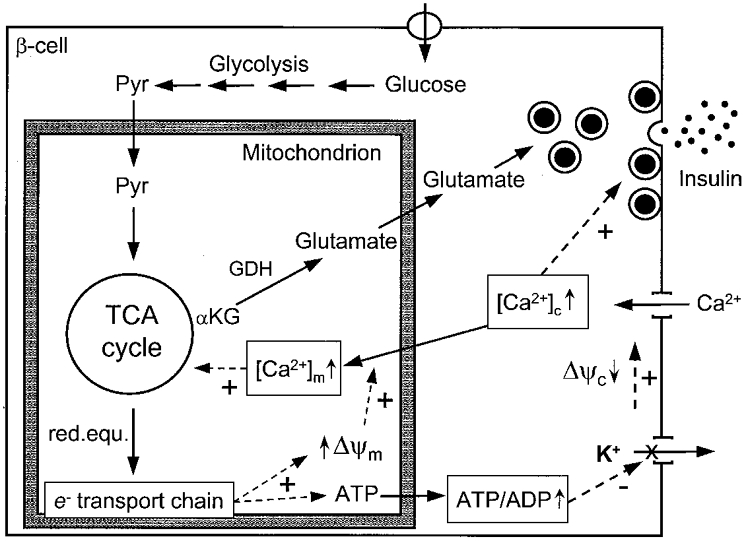

Glutamate can be generated through several biochemical pathways including transamination reactions (see Nissim, 1999). Predominantly, in the mitochondria, glutamate dehydrogenase forms glutamate from the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate (Fig. 4). In most tissues this is the prevailing direction for the enzyme reaction with the notable exception of astrocytes (reviewed by Hudson & Daniel, 1993; Nissim, 1999). Several studies have addressed the question of the importance of glutamate dehydrogenase in the pancreatic beta cell. It is noteworthy that glutamine oxidation, stimulated by the presence of an allosteric activator of glutamate dehydrogenase, is inhibited by glucose (Gao et al. 1999). The most likely donors of ammonia for glutamate synthesis by glutamate dehydrogenase are glutamine and aspartate (Nissim, 1999). In the cerebral cortex glutamate production from glucose has been shown to reflect TCA cycle activity and carbon flux in resting humans and exercising rats (Hyder et al. 1996; Shen et al. 1999). The directional flux was also increased in mouse islets since incorporation of glucose carbons into glutamate was augmented by glucose stimulation without a change in cellular glutamate content (Gylfe & Hellman, 1974).

Figure 4. Proposed model for coupling of glucose metabolism to insulin secretion in the beta cell.

Glycolysis converts glucose to pyruvate (Pyr), which enters the mitochondrion and feeds the TCA cycle, resulting in the transfer of reducing equivalents (red.equ.) to the electron (e−) transport chain, hyperpolarisation of ΔΨm and generation of ATP. Subsequently, closure of KATP channels depolarises the plasma membrane which opens voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels, raising [Ca2+]c and triggering insulin exocytosis. Concomitantly, under conditions of elevated [Ca2+]c, hyperpolarised ΔΨm promotes [Ca2+]m rise, further activating the TCA cycle. Glutamate is then formed from α-ketoglutarate (αKG) by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). Glutamate uptake by granules would participate in the second phase of insulin secretion. Reproduced from Maechler & Wollheim (1999), with permission.

The glutamate formed in the mitochondria is transferred to the cytosol where it is probably taken up by the insulin-containing granules (Fig. 4). In agreement with glutamate transport properties in synaptic vesicles (see Ozkan & Ueda, 1998), collapse of the granule membrane potential and application of an inhibitor of glutamate uptake blocked glutamate-induced insulin exocytosis in permeabilised INS-1 cells (Maechler & Wollheim, 1999). However, glutamate uptake by insulin-containing secretory granules remains to be demonstrated. Glutamate may be transported by the recently identified vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT1 or BNPI (Bellocchio et al. 2000; Takamori et al. 2000). It can be speculated that glutamate has a general effect of sensitising secretory vesicles to the action of Ca2+ in exocytosis. Interestingly, glutamate is usually used as the main anion in experiments employing permeabilised cells or the patch-clamp technique for the monitoring of exocytosis. Churcher & Gomperts (1990) used Cl− as the main anion in permeabilised mast cells and in fact observed that glutamate was required for Ca2+-induced exocytosis. Our experiments, like those in the mast cells, employed a buffer containing Cl− as the main anion (Maechler & Wollheim, 1999). At present, the mechanism underlying the permissive action of glutamate in the secretory process is unknown.

Conclusion

Glutamate may not only play a role in the physiological regulation of insulin secretion but may also be implicated in beta cell pathology. It is of interest in this context that a syndrome of hyperinsulinism has been linked to mutations in the glutamate dehydrogenase gene resulting in an increase in enzyme activity (Stanley et al. 1998; Yorifuji et al. 1999). The impact of these mutations on insulin secretion has its counterpart in the allosteric stimulation of the enzyme by the amino acid analogue 2-amino-bicyclo[2,2,1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid (Sener & Malaisse, 1980). The putative role of glutamate as a messenger has recently been substantiated in a transgenic mouse model. Those mice overexpressing the glutamate decarboxylating enzyme GAD65 display glucose intolerance without any sign of insulitis or loss of beta cells. Their islets showed impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, while the response to KCl was preserved (Shi et al. 2000).

In conclusion, although the crucial role of the mitochondria in beta cell function is well recognised, the last decade has revealed that metabolism-secretion coupling is more complex than originally expected. It may be speculated that not only ATP and glutamate but also other mitochondrially derived factors participate in the overall control of exocytosis. The elucidation of the mode of glutamate action in the beta cell should help to define its putative implication in other secretory processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs T. Pozzan, H. Ishihara and P. A. Antinozzi for stimulating discussions. We are grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for continued support of our research.

References

- Ahren B. Autonomic regulation of islet hormone secretion-implications for health and disease. Diabetologia. 2000;43:393–410. doi: 10.1007/s001250051322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinozzi PA, Segall L, Prentki M, McGarry JD, Newgard CB. Molecular or pharmacologic perturbation of the link between glucose and lipid metabolism is without effect on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. A re-evaluation of the long-chain acyl-CoA hypothesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:16146–16154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–960. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten P. Slow and fast oscillations of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in pancreatic islets correspond to pulsatile insulin release. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:E282–287. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.2.E282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand G, Gross R, Puech R, Loubatieres-Mariani MM, Bockaert J. Evidence for a glutamate receptor of the AMPA subtype which mediates insulin release from rat perfused pancreas. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;106:354–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churcher Y, Gomperts BD. ATP-dependent and ATP-independent pathways of exocytosis revealed by interchanging glutamate and chloride as the major anion in permeabilized mast cells. Cell Regulation. 1990;1:337–346. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.4.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civelek VN, Deeney JT, Shalosky NJ, Tornheim K, Hansford RG, Prentki M, Corkey BE. Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mitochondrial metabolism: influence of Ca2+, substrate and ADP. Biochemical Journal. 1996;318:615–621. doi: 10.1042/bj3180615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkey BE, Deeney JT, Yaney GC, Tornheim K, Prentki M. The role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in beta-cell signal transduction. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:299–304S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.299S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson A, Hellman B, Idahl LA. Levels of α-ketoglutarate and glutamate in stimulated pancreatic β-cells. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 1970;2:28–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton RM, McCormack JG. On the role of the calcium transport cycle in heart and other mammalian mitochondria. FEBS Letters. 1980;119:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80986-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detimary P, Gilon P, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Two sites of glucose control of insulin release with distinct dependence on the energy state in pancreatic B-cells. Biochemical Journal. 1994;297:455–461. doi: 10.1042/bj2970455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR. Contributions of mitochondria to animal physiology: from homeostatic sensor to calcium signalling and cell death. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.001aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K, Tsubamoto Y, Terauchi Y, Sugiyama T, Kishimoto T, Takahashi N, Yamauchi N, Kubota N, Murayama S, Aizawa T, Akanuma Y, Aizawa S, Kasai H, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Role of NADH shuttle system in glucose-induced activation of mitochondrial metabolism and insulin secretion. Science. 1999;283:981–985. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahien LA, MacDonald MJ, Kmiotek EH, Mertz RJ, Fahien CM. Regulation of insulin release by factors that also modify glutamate dehydrogenase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:13610–13614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfari S, Schulz V, Corkey B, Prentki M. Glucose-regulated anaplerosis and cataplerosis in pancreatic β-cells: possible implication of a pyruvate/citrate shuttle in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:718–726. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZY, Li G, Najafi H, Wolf BA, Matschinsky FM. Glucose regulation of glutaminolysis and its role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1999;48:1535–1542. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gembal M, Gilon P, Henquin JC. Evidence that glucose can control insulin release independently from its action on ATP-sensitive K+ channels in mouse B cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;89:1288–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI115714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gylfe E, Hellman B. Role of glucose as a regulator and precursor of amino acids in the pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 1974;94:1150–1156. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-4-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford RG. Relation between mitochondrial calcium transport and control of energy metabolism. Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1985;102:1–72. doi: 10.1007/BFb0034084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Noda M, Yasuda K, Yorifuji H, Taniguchi S, Miwa I, Sakura H, Terauchi Y, Hayashi J, Sharp GW, Kanazawa Y, Akanuma Y, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Ethidium bromide-induced inhibition of mitochondrial gene transcription suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin release in the mouse pancreatic beta-cell line betaHC9. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:20300–20307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman B. Methodological approaches to studies on the pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 1970;6:110–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00421438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RC, Daniel RM. L-glutamate dehydrogenases: distribution, properties and mechanism. Comprehensive Biochemical Physiology. 1993;106:767–792. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(93)90031-y. B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder F, Chase JR, Behar KL, Mason GF, Siddeek M, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. Increased tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in rat brain during forepaw stimulation detected with 1H[13C]NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:7612–7617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Kuromi H, Gonoi T, Okamoto Y, Ishida H, Seino Y, Kaneko T, Iwanaga T, Seino S. Expression and role of ionotropic glutamate receptors in pancreatic islet cells. FASEB Journal. 1995;9:686–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Wang H, Drewes LR, Wollheim CB. Overexpression of monocarboxylate transporter and lactate dehydrogenase alters insulin secretory responses to pyruvate and lactate in beta cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;104:1621–1629. doi: 10.1172/JCI7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Wollheim CB. What couples glycolysis to mitochondrial signal generation in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion? IUBMB Life. 2000;49:391–395. doi: 10.1080/152165400410236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn BB. Type 2 diabetes: when insulin secretion fails to compensate for insulin resistance. Cell. 1998;92:593–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy ED, Maechler P, Wollheim CB. Effects of depletion of mitochondrial DNA in metabolism secretion coupling in INS-1 cells. Diabetes. 1998;47:374–380. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy ED, Rizzuto R, Theler JM, Pralong WF, Bastianutto C, Pozzan T, Wollheim CB. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion correlates with changes in mitochondrial and cytosolic Ca2+ in aequorin-expressing INS-1 cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98:2524–2538. doi: 10.1172/JCI119071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Nakanishi K, Nakase H, Kajio H, Okubo M, Murase T, Kosaka K. In situ characterization of islets in diabetes with a mitochondrial DNA mutation at nucleotide position 3243. Diabetes. 1997;46:1567–1571. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of insulin exocytosis as a paradigm of endocrine secretion. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1999;259:3–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J, Nishimoto I, Okamoto T, Regazzi R, Kiraly C, Weller U, Wollheim CB. Direct control of exocytosis by receptor-mediated activation of the heterotrimeric GTPases Gi and Go or by the expression of their active G alpha subunits. EMBO Journal. 1995;14:3635–3644. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen JA, Kadowaki T. Maternally inherited diabetes and deafness: a new diabetes subtype. Diabetologia. 1996;39:375–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00400668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MJ. High content of mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in pancreatic islets and its inhibition by diazoxide. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256:8287–8290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MJ. Feasibility of a mitochondrial pyruvate malate shuttle in pancreatic islets. Further implication of cytosolic NADPH in insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:20051–20058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MJ, Fahien LA. Glutamate is not a messenger in insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000411200. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P, Antinozzi PA, Wollheim CB. Modulation of glutamate generation in the mitochondria affects hormone secretion in INS-1E beta cells. IUBMB Life. 2000. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maechler P, Kennedy ED, Pozzan T, Wollheim CB. Mitochondrial activation directly triggers the exocytosis of insulin in permeabilized pancreatic β-cells. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:3833–3841. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P, Kennedy ED, Wang H, Wollheim CB. Desensitization of mitochondrial Ca2+ and insulin secretion responses in the beta cell. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:20770–20778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P, Wollheim CB. Glutamate acts as a mitochondrially derived messenger in glucose-induced insulin exocytosis. Nature. 1999;402:685–689. doi: 10.1038/45280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaisse WJ, Sener A, Carpinelli AR, Anjaneyulu K, Lebrun P, Herchuelz A, Christophe J. The stimulus-secretion coupling of glucose-induced insulin release. XLVI. Physiological role of L-glutamine as a fuel for pancreatic islets. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1980;20:171–189. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(80)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik M, Nelson J, Erecinska M. Glutamate production in islets of Langerhans: properties of phosphate-activated glutaminase. Metabolism. 1992;41:1319–1326. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90102-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Nagashima K, Tashiro F, Kotake K, Yoshitomi H, Tamamoto A, Gonoi T, Iwanaga T, Miyazaki J, Seino S. Defective insulin secretion and enhanced insulin action in KATP channel-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:10402–10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Yano H, Niwa H, Ban N, Ihara Y, Kubota A, Fujimoto S, Kajikawa M, Kuroe A, Tsuda K, Hashimoto H, Yamashita T, Jomori T, Tashiro F, Miyazaki J, Seino Y. Glucose intolerance caused by a defect in the entero-insular axis: a study in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:14843–14847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard CB, McGarry JD. Metabolic coupling factors in pancreatic β-cell signal transduction. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1995;64:689–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim I. Newer aspects of glutamine/glutamate metabolism: the role of acute pH changes. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:F493–497. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.4.F493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan ED, Ueda T. Glutamate transport and storage in synaptic vesicles. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;77:1–10. doi: 10.1254/jjp.77.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porte D. Beta-cells in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1991;40:166–180. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentki M, Vischer S, Glennon MC, Regazzi R, Deeney JT, Corkey BE. Malonyl-CoA and long chain acyl-CoA esters as metabolic coupling factors in nutrient-induced insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:5802–5810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Simpson AWM, Brini M, Pozzan T. Rapid changes of mitochondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature. 1992;358:325–327. doi: 10.1038/358325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P. The pancreatic beta-cell as a fuel sensor: an electrophysiologist’s viewpoint. Diabetologia. 1997;40:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s001250050706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Aizawa T, Komatsu M, Okada N, Yamada T. Dual functional role of membrane depolarization/Ca2+ influx in rat pancreatic B-cell. Diabetes. 1992;41:438–443. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit F, De Vos A, Farfari S, Moens K, Pipeleers D, Brun T, Prentki M. Metabolic fate of glucose in purified islet cells. Glucose-regulated anaplerosis in beta cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:18572–18579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice. A model for K(ATP) channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:9270–9277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine N, Cirulli V, Regazzi R, Brown LJ, Gine E, Tamarit-Rodriguez J, Girotti M, Marie S, MacDonald MJ, Wollheim CB, Rutter GA. Low lactate dehydrogenase and high mitochondrial glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase in pancreatic beta-cells. Potential role in nutrient sensing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:4895–4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener A, Conget I, Rasschaert J, Leclercq-Meyer V, Villanueva-Penacarrillo ML, Valverde I, Malaisse WJ. Insulinotropic action of glutamic acid dimethyl ester. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:E573–584. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.4.E573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener A, Malaisse WJ. L-leucine and a nonmetabolized analogue activate pancreatic islet glutamate dehydrogenase. Nature. 1980;288:187–189. doi: 10.1038/288187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener A, Rasschaert J, Malaisse WJ. Hexose metabolism in pancreatic islets. Participation of Ca2+-sensitive 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in the regulation of mitochondrial function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1990;1019:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90122-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp GW. Mechanisms of inhibition of insulin release. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C1781–1799. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.6.C1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Petersen KF, Behar KL, Brown P, Nixon TW, Mason GF, Petroff OA, Shulman GI, Shulman RG, Rothman DL. Determination of the rate of the glutamate/glutamine cycle in the human brain by in vivo 13C NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Kanaani J, Menard-Rose V, Ma YH, Chang P-Y, Hanahan D, Tobin A, Grodsky G, Baekkeskov S. Increased expression of GAD65 and GABA in pancreatic β-cell impairs first phase insulin secretion. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;279:E684–694. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.3.E684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soejima A, Inoue K, Takai D, Kaneko M, Ishihara H, Oka Y, Hayashi JI. Mitochondrial DNA is required for regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in a mouse pancreatic beta cell line, MIN6. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:26194–26199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley CA, Lieu YK, Hsu BY, Burlina AB, Greenberg CR, Hopwood NJ, Perlman K, Rich BH, Zammarchi E, Poncz M. Hyperinsulinism and hyperammonemia in infants with regulatory mutations of the glutamate dehydrogenase gene. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:1352–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature. 2000;407:189–194. doi: 10.1038/35025070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamarit-Rodriguez J, Fernandez-Pascual S, Mukala-Nsengu-Tshibangu A, Martin del Rio R. Changes of L-α-amino acid profile in rat islets stimulated to secrete insulin. Proceedings of the Islet in Eilat 2000 Meeting; 21–24 September 2000; 2000. p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruzoe K, Araki E, Furukawa N, Shirotani T, Matsumoto K, Kaneko K, Motoshima H, Yoshizato K, Shirakami A, Kishikawa H, Miyazaki J, Shichiri M. Creation and characterization of a mitochondrial DNA-depleted pancreatic beta-cell line: impaired insulin secretion induced by glucose, leucine, and sulfonylureas. Diabetes. 1998;47:621–631. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ouweland JM, Maechler P, Wollheim CB, Attardi G, Maassen JA. Functional and morphological abnormalities of mitochondria harbouring the tRNA(Leu)(UUR) mutation in mitochondrial DNA derived from patients with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) and progressive kidney disease. Diabetologia. 1999;42:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s001250051183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CD, Yao TL, Powers AC, Verdoorn TA. Differential expression of glutamate receptor subtypes in rat pancreatic islets. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:12977–12984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollheim CB. Beta-cell mitochondria in the regulation of insulin secretion: a new culprit in Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2000;43:265–277. doi: 10.1007/s001250050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorifuji T, Muroi J, Uematsu A, Hiramatsu H, Momoi T. Hyperinsulinism-hyperammonemia syndrome caused by mutant glutamate dehydrogenase accompanied by novel enzyme kinetics. Human Genetics. 1999;104:476–479. doi: 10.1007/s004390050990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]