Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that propagation of cytosolic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c) spikes and oscillations to the mitochondria is important for the control of fundamental cellular functions. Delivery of [Ca2+]c spikes to the mitochondria may utilize activation of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites by the large local [Ca2+]c rise occurring in the vicinity of activated sarco-endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) Ca2+ release channels. Although direct measurement of the local [Ca2+]c sensed by the mitochondria has been difficult, recent studies shed some light onto the molecular mechanism of local Ca2+ communication between SR/ER and mitochondria. Subdomains of the SR/ER are in close contact with mitochondria and display a concentration of Ca2+ release sites, providing the conditions for an effective delivery of released Ca2+ to the mitochondrial targets. Furthermore, many functional properties of the signalling between SR/ER Ca2+ release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites, including transient microdomains of high [Ca2+], saturation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites by released Ca2+, connection of multiple release sites to each uptake site and quantal transmission, are analogous to the features of the coupling between neurotransmitter release sites and postsynaptic receptors in synaptic transmission. As such, Ca2+ signal transmission between SR/ER and mitochondria may utilize discrete communication sites and a closely related functional architecture to that used for synaptic signal propagation between cells.

Although the large capacity of isolated mitochondria to take up Ca2+ has been well known since the 1960′s, its relevance under physiological conditions remained subject to controversy until recently. Mitochondria were believed to be relatively insensitive to physiological [Ca2+]c increases since the rise of global [Ca2+]c to 500 nM-1 μm during IP3 receptor (IP3R)- or ryanodine receptor (RyR)-driven [Ca2+]c spiking is probably not sufficient to activate the low affinity mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanisms. However, a different picture emerged from experiments that utilized novel approaches to directly measure mitochondrial matrix [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]m) in living cells. Experiments using Ca2+-sensitive photoproteins targeted to the mitochondria, or fluorescent Ca2+ tracers loaded into the mitochondria, demonstrated increases of [Ca2+]m that occurred simultaneously with [Ca2+]c spikes and oscillations (Rizzuto et al. 1993, 1994; Hajnóczky et al. 1995). These results have been explained by a close coupling of IP3R- and RyR-mediated Ca2+ release to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, allowing mitochondrial uptake sites to sense the high local [Ca2+]c adjacent to the activated release sites.

The obligatory components of the local Ca2+ transfer are the SR/ER Ca2+ release sites (RyR/IP3R) and the mito-chondrial Ca2+ uptake sites (Ca2+ uniporter), but the SR/ER Ca2+ uptake sites, the mitochondrial Ca2+ release sites and Ca2+ binding proteins are also important Ca2+-handling elements of the SR/ER-mitochondrial communication. The complex regulation of RyR by Ca2+, and IP3R by IP3 and Ca2+, allows these Ca2+ channels to exhibit rapid and concerted activation and inactivation, giving rise to bursts of Ca2+ release from the high [Ca2+] SR/ER lumen to the low [Ca2+] cytosol. At low [Ca2+]c levels, the membrane potential (ΔΨm)-driven Ca2+ uniporter-mediated mito-chondrial Ca2+ influx is balanced by Ca2+ efflux, but large or sustained elevations of [Ca2+]c effectively activate the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and may result in robust [Ca2+]m signals. For a comprehensive analysis of Ca2+ transport properties of SR/ER and mitochondria we refer the reader to reviews published recently (Pozzan et al. 1994; Taylor, 1998; Gunter et al. 1998; Bers & Perez-Reyes, 1999).

The physiological significance of IP3R- and RyR-driven [Ca2+]m signals has been shown in the control of mito-chondrial energy metabolism (McCormack et al. 1990; Pralong et al. 1994; Hajnóczky et al. 1995; Rutter et al. 1996; Brandes & Bers, 1997; Rohács et al. 1997; Robb-Gaspers et al. 1998a,b; Jouaville et al. 1999). This effector system can be tuned to the oscillatory range of [Ca2+]c signalling and actually tune out sustained [Ca2+]c signals, indicating that mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is activated by the short-lasting [Ca2+]c microdomains during IP3R- and RyR-driven [Ca2+]c signals (Hajnóczky et al. 1995). Furthermore, several lines of evidence suggest that mito-chondrial Ca2+ uptake may exert a number of important feedback effects on the [Ca2+]c signal during IP3R- and RyR-driven [Ca2+]c spikes and oscillations (Jouaville et al. 1995; Ichas et al. 1997; Babcock et al. 1997; Simpson et al. 1997; Landolfi et al. 1998; Boitier et al. 1999; Hajnóczky et al. 1999; Tinel et al. 1999; Jaconi et al. 2000). One major mechanism for the feedback could be that mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites modulate the local Ca2+ feedback control on adjacent Ca2+ release sites (Jouaville et al. 1995; Boitier et al. 1999; Hajnóczky et al. 1999). Thus the local communication between Ca2+ release and uptake sites is also important for the shaping of the SR/ER-dependent global [Ca2+]c signals. Mitochondria may also blunt and prolong global [Ca2+]c signals by acting as a slow, large-capacity Ca2+ buffer that accumulates Ca2+ during rapid [Ca2+]c increases and then returns the Ca2+ as [Ca2+]c declines (Babcock et al. 1997), but the fraction of released Ca2+ taken up by the mitochondria remains to be determined. Furthermore, mitochondrial ATP production may exert local control over Ca2+ handling by SR/ER (Landolfi et al. 1998). A role for mitochondrial Ca2+ overload in cell death has been proposed for many years. Recent studies have established that release of mitochondrial factors into the cytosol is essential for execution of apoptosis (Liu et al. 1996; Susin et al. 1999a,b) and that propagation of IP3R-mediated [Ca2+]c signals to the mitochondria may trigger the mitochondrial phase of apoptotic cell death (Szalai et al. 1999). Local Ca2+ transfer between SR/ER and mitochondria has also been involved in this pathway. Collectively, these results underscore the role of local Ca2+ communication between SR/ER Ca2+ release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites in the control of a number of cellular functions.

In addition to the local Ca2+ signalling between SR/ER and mitochondria, Ca2+ transfer may also occur between plasma membrane Ca2+ entry sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Pralong et al. 1992; Rutter et al. 1993; Friel & Tsien, 1994; Budd & Nicholls, 1996) utilizing high [Ca2+]c microdomains that occur beneath the plasma membrane and are sensed by the mitochondria located in this region (Lawrie et al. 1996; Hoth et al. 1997; Svichar et al. 1997; Peng & Greenamyre, 1998). Notably, close association of mitochondria with the source of Ca2+ is not always apparent and alternative explanations for mito-chondrial Ca2+ sequestration during physiological [Ca2+]c signals include sensitization of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites by cytosolic factors (Rustenbeck et al. 1993) and a rapid mode of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Sparagna et al. 1995). These mechanisms and the overall role of mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling in cell physiology have been reviewed elsewhere (Babcock & Hille, 1998; Gunter et al. 1998; Bernardi, 1999; Duchen, 1999; Rizzuto et al. 1999; Hajnóczky et al. 2000; Hüser et al. 2000; Nicholls & Budd, 2000). This review is restricted to the machinery of local Ca2+ coupling between SR/ER and mitochondria.

Our paper is arranged in three sections. The first is concerned with observations on the structural coupling between SR/ER and mitochondria. The second section summarizes the [Ca2+]m signal phenomena observed in association with IP3R- and RyR-driven [Ca2+]c oscillations and the arguments that strategical localization of mito-chondria at sites of Ca2+ release facilitates Ca2+ signal propagation to the mitochondria. In the third section we discuss the experiments and ideas on the functional organization underlying local communication between SR/ER Ca2+ release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites. Although other examples are also available, we use the data of our group to illustrate some major features of mitochondrial calcium signalling.

Structural coupling between SR/ER and mitochondria

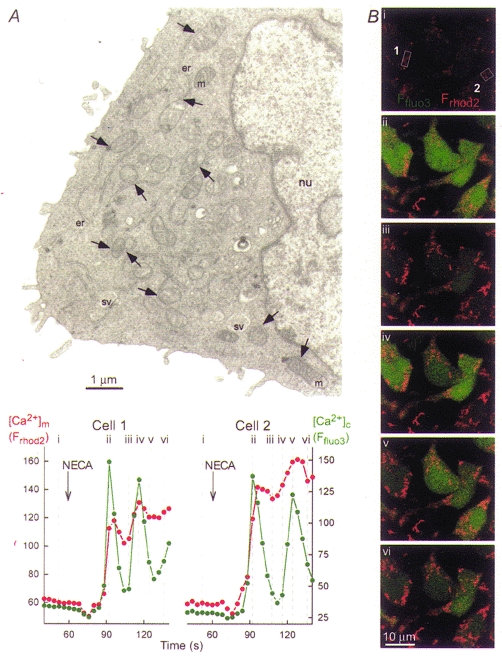

In a wide variety of cells, conventional thin section transmission electron microscopy images have shown mitochondria in close apposition with SR/ER (Sommer & Johnson, 1970; Shore & Tata, 1977). For example, Fig. 1A shows that most of the mitochondria exhibit membrane regions that are in close proximity with ER membranes in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Based on our two-dimensional electron microscopy data, the interface area is restricted to a small part of the total surface area for most of the mitochondria. Notably, in some cell types the interface area appears to be larger than in RBL-2H3 mast cells. For example, hepatic mitochondria are embedded in multi-lamellar stacks of ER as demonstrated using three-dimensional reconstruction of images obtained by high-voltage electron microscopic tomography of thick liver sections (Mannella et al. 1998; Mannella, 2000). By imaging green fluorescent protein (GFP) constructs targeted to the ER and mitochondria, Rizzuto et al. (1998) estimated that 5-20 % of the mitochondrial surface is in close apposition to ER in living HeLa cells. Taken together, these results suggest that discrete domains of the SR/ER and mitochondrial surface form junctions that may be particularly suitable to support local communication between these organelles.

Figure 1. Physical and functional coupling between ER and mitochondria in RBL-2H3 mast cells.

A, electron micrograph showing a thin section (80 nm) of a RBL-2H3 mast cell. Organelles are marked as follows: nu, nucleus; er, endoplasmic reticulum; m, mitochondria; sv, secretory vesicles. Arrows point to ER-mitochondrial junctions. Note that only a few examples of ER, mitochondria and ER-mitochondrial junctions are marked. B, simultaneous confocal imaging of IP3R-driven [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m signals in RBL-2H3 cells. Cells were loaded first with rhod-2 AM ([Ca2+]m; 3 μm for 50 min at 37 °C) and subsequently with fluo-3 AM ([Ca2+]c; 5 μm for 25 min at room temperature). Evidence that rhod-2 measured [Ca2+]m in RBL-2H3 cells was provided by morphological and pharmacological studies described in Csordás et al. 1999. Fluorescence intensity of fluo-3 and rhod-2 reflecting [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m are depicted on linear green and red scales, respectively. Confocal image time series shows the spatiotemporal pattern of [Ca2+] responses evoked by a phospholipase C-linked adenosine receptor agonist, 5′-(N-ethyl)carboxamidoadenosine (NECA, 50 μm). Graphs show corresponding traces of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m (fluo-3 and rhod-2 signals, respectively, expressed as fluorescence arbitrary units) calculated for the regions marked by boxes on image i.

To establish effective local calcium signalling at the ER-mitochondrial junctions both the reticular Ca2+ release sites and the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites should be present at the interface area. Distribution of the IP3Rs and RyRs is not homogenous in SR/ER and the subdomains exhibiting a high density of IP3R or RyR Ca2+ release sites appear to be particularly active in calcium signal generation. Although visualization of Ca2+ release sites has been difficult in many cell types, evidence emerges that a high density of IP3Rs exist in ER domains facing the mitochondria (type 1 IP3R: Mignery et al. 1989; Satoh et al. 1990; Takei et al. 1992; type 2 IP3R: Simpson et al. 1997, 1998). In cardiac muscle cells, RyRs are concentrated at the calcium release units and can be identified (as the feet) without immunostaining using conventional transmission electron microscopy. In a recent study, Sharma et al. (2000) demonstrated that 90 % of the calcium release units are very close to mitochondria. Distribution of Ca2+ uptake sites on the mitochondrial surface has not been visualized thus far. Data showing heterogeneity of the IP3R- or RyR-mediated [Ca2+]m signal at subcellular resolution (e.g. Rizzuto et al. 1998; Drummond et al. 2000) may indicate that only subsets of the mitochondrial uptake sites are concentrated at the junctions. Alternatively, some mitochondria may not form junctions with SR/ER or may display less effective Ca2+ uptake (e.g. differences in driving force or in allosteric activation of the uniporter). Under conditions designed to ensure uniform substrate supply and synchronized activation of all Ca2+ release sites in permeabilized cells, we demonstrated saturation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites during IP3R-induced Ca2+ release in RBL-2H3 cells (Csordás et al. 1999) and an almost maximal activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during RyR-mediated Ca2+ release in H9c2 myotubes (Szalai et al. 2000). Thus in these experiments, most of the Ca2+ uptake sites sensed the high local [Ca2+] occurring in the vicinity of activated release sites. Based on these data, a high density of RyRs/IP3Rs occurs in the domains of SR/ER membranes adjacent to the mitochondria, providing the structural background for exposure of the mitochondria to high [Ca2+]c microdomains generated at the activated Ca2+ release sites. Furthermore, mitochondrial uptake sites also face the SR/ER-mitochondrial junctions, although the fraction of uptake sites coupled to the SR/ER may depend on cell type and condition of the cell.

If SR/ER-mitochondrial junctions are the major relay stations in calcium signal propagation to the mitochondria, it is important to explain how the local communication is sustained during continuous movement and reorganization of these organelles in the cells. One solution might be anchoring of the significant SR/ER domains to the mitochondria. Since microfilaments and microtubules control organization of the ER (Terasaki & Reese, 1994) including the continuity of the ER Ca2+ store (Hajnóczky et al. 1994) and interactions with the cytoskeleton are also involved in mitochondrial movements (for review see Bereiter-Hahn & Voth, 1994; Yaffe, 1999), cytoskeleton elements may provide a frame to stabilize the position of the interacting Ca2+ channels. Other anchoring proteins might also be involved in linking mitochondrial membranes to the Ca2+ release sites; for example, IP3R and RyR interact with a plethora of accessory proteins (for recent review see MacKrill, 1999). However, a single protein is not likely to form a bridge between SR/ER Ca2+ release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites since the Ca2+-permeable outer mitochondrial membrane is located between the SR/ER membrane and inner mitochondrial membrane that contains the Ca2+ uptake sites. A major task for future studies is to determine whether the SR/ER-mitochondrial junctions are supported by coupling elements and if there is a physical connection then the participating molecules have to be identified. An alternative to the supporting frame or direct physical connection between the interacting membranes is that colocalization of Ca2+ release and uptake sites at the junctions is ensured by redistribution of Ca2+ channels as SR/ER and mitochondrial membranes move. Redistribution of the release sites has already been shown to occur under various conditions (e.g. Wilson et al. 1998) and the spatial rearrangements may ensure that the local connections to the mitochondria are sustained. However, it is likely that the release site redistribution does not simply follow the organelle movements and so this relocation may also serve to modulate the effectiveness of the local Ca2+ coupling between ER release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites.

[Ca2+]m signals coupled to [Ca2+]c oscillations

Direct measurement of IP3R-linked [Ca2+]m responses was accomplished first using aequorin targeted to the mitochondria (Rizzuto et al. 1993, 1994; Rutter et al. 1996). These studies provided the seminal observation that [Ca2+]c transients are associated with large [Ca2+]m spikes. However, owing to the low signal levels and consumption of aequorin it has been difficult to study [Ca2+] oscillations in individual cells using this approach. Measurement of [Ca2+]m with fluorescent Ca2+ tracers has been complicated by non-selective loading of intracellular compartments (e.g. Miyata et al. 1991). The development of Ca2+-sensitive probes which are loaded preferentially into the mitochondria (rhod-2, Tsien & Bácskai, 1995) and optimization of the loading conditions has allowed single cell fluorescence imaging of [Ca2+]m to be established in many cell types (Hajnóczky et al. 1995; Jou et al. 1996; Simpson & Russell, 1996). Furthermore, co-loading of cells with fura-2 that is trapped in the cytosol and rhod-2 permits simultaneous kinetic comparison of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m changes (Hajnóczky et al. 1995). These studies have demonstrated that [Ca2+]m spikes are synchronized to the individual [Ca2+]c spikes during IP3R-driven [Ca2+]c oscillations.

Propagation of IP3-induced [Ca2+]c spiking to the mitochondria is illustrated by a simultaneous confocal imaging measurement of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m carried out in RBL-2H3 cells co-loaded with fluo-3 and rhod-2 (Fig. 1B). In a previous study, we have shown that compartmentalized rhod-2 is co-localized with mitochondrion-specific fluorophores (e.g. Mitotracker, GFP targeted to the mitochondria) and the IP3-induced [Ca2+]rhod-2 signal is abolished by mitochondrial inhibitors, suggesting that rhod-2 measured [Ca2+]m in RBL-2H3 cells (Csordás et al. 1999). In intact cells, stimulation of IP3 formation by an adenosine receptor agonist resulted in [Ca2+]c spikes which appeared throughout the cells (Fig. 1B; shown in green). IP3-induced global elevations of [Ca2+]c have been calculated to peak at 400-700 nM in RBL-2H3 mast cells (Oancea & Meyer, 1996). As also shown in Fig. 1B, the IP3-induced [Ca2+]c spikes were accompanied by parallel spikes of [Ca2+]m that showed relatively slow decay (permanent red signal in the images). Because of the prolonged decay phase, the second [Ca2+]m transients were superimposed on the falling phase of the preceding transient. A rapid rise of [Ca2+]m during IP3-induced Ca2+ mobilization has been documented in a wide variety of cell types, whereas relaxation of the [Ca2+]m spikes is slower in RBL-2H3 mast cells than in some other cell types e.g. HeLa cells, MH75 cells, 143B ostesarcoma cells, L929 fibroblasts (Rizzuto et al. 1993, 1994) and hepatocytes (Hajnóczky et al. 1995; Rutter et al. 1996). In hepatocytes, which display [Ca2+]m transients in association with brief [Ca2+]c spikes, the maintained high [Ca2+]c signals elicited by maximal activation of the IP3-linked pathway also evoked a transient elevation of [Ca2+]m (Hajnóczky et al. 1995). The decay of the [Ca2+]m signals during the sustained phase of stimulation may result from dissipation of the high [Ca2+]c microdomain after the initial rapid Ca2+ release phase.

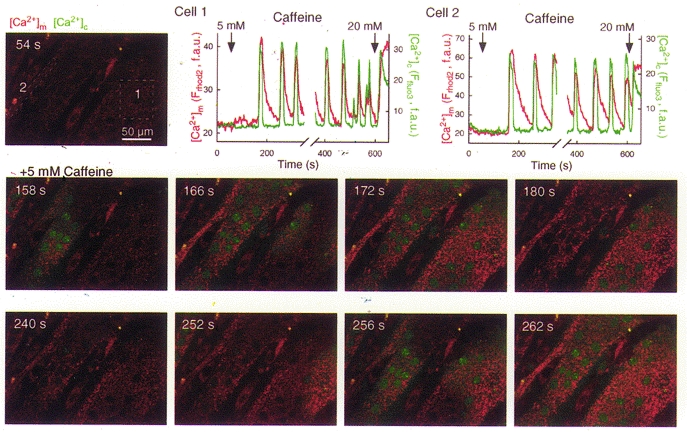

Coupling of large [Ca2+]m transients to RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c signals has also been reported in various cell types such as skeletal muscle myotubes (Brini et al. 1997), smooth muscle cells (Drummond & Tuft, 1999; Drummond et al. 2000) and chromaffin cells (Montero et al. 2000). Because the [Ca2+]m signal may be important for coordination of mitochondrial ATP production with the demand imposed by heart contractions, the effect of RyR-dependent [Ca2+]c oscillations on [Ca2+]m have been intensively investigated in cardiac cells. Fluorescence measurements of [Ca2+]m showed that changes of [Ca2+]m occur in association with changes in the frequency of [Ca2+]c spiking (Miyata et al. 1991; Bassani et al. 1992; Griffiths et al. 1997a; Zhou et al. 1998), whereas other studies showed beat-to-beat regulation of [Ca2+]m in intact cardiac myocytes (Sheu & Jou, 1994; Chacon et al. 1996; Trollinger et al. 1997; Ohata et al. 1998). Concern has been raised that the cytosolic contribution from Ca2+-sensitive dyes could contribute to the beat-to-beat fluctuations reported in [Ca2+]m (e.g. Zhou et al. 1998). To avoid the complexities resulting from heterogeneous compartmentalization of Ca2+-sensitive tracers, experiments have also been carried out recently using permeabilized adherent cardiomyocytes (Sharma et al. 2000) and H9c2 cardiac myotubes (Szalai et al. 2000). Activation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release was found to evoke large [Ca2+]m transients, demonstrating delivery of Ca2+ from RyR to the mitochondria. Furthermore, in response to suboptimal stimulation of the RyR, coordinated oscillations of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m were recorded in permeabilized cardiac myotubes (Szalai et al. 2000). The spatiotemporal organization of the RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m spiking is illustrated by the confocal imaging experiment shown in Fig. 2. After addition of suboptimal caffeine, Ca2+ release started at discrete subcellular regions and gave rise to repetitive [Ca2+]c waves that travelled several hundred micrometre distances at a relatively constant rate (∼20 μm s−1, shown in green) in permeabilized H9c2 myotubes. These Ca2+ waves never appeared if the SR Ca2+ store had been discharged prior to addition of caffeine, suggesting SR origin of the [Ca2+]c response. Furthermore, the [Ca2+]c waves were associated with [Ca2+]m waves, illustrating propagation of the RyR-mediated calcium signal to the mitochondria (shown in red). Time courses of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m show that the [Ca2+]c spikes were uniform during [Ca2+]c oscillations and each spike exhibited a sharp rise and decay phase. Rise of the [Ca2+]m spikes was synchronized to the upstroke of the [Ca2+]c spikes and the decay phase of the [Ca2+]m response was also fast, resulting in rapid return close to the prestimulation [Ca2+]m level. Although the [Ca2+]c spikes last longer in H9c2 myotubes than in cardiac myocytes, close association of the [Ca2+]m rise with the [Ca2+]c rise suggests, that subsecond [Ca2+]c spikes would also be effective in eliciting a [Ca2+]m rise. Consistent with this idea we have been able to record very short [Ca2+]c transients and closely associated [Ca2+]m transients in small regions of permeabilized H9c2 myotubes (P. Pacher & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished data). Taken together, growing evidence suggests that RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c spikes are translated into [Ca2+]m spikes in a number of cell types.

Figure 2. Coordination of RyR-driven [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m oscillations and waves in permeabilized H9c2 cardiac myotubes.

Simultaneous confocal imaging of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m carried out using fluo-3 and compartmentalized rhod-2, respectively. Cells were loaded first with rhod-2 AM (4 μm for 50 min at 37 °C) and after permeabilization, fluo-3 FA (10 μm) was added to the intracellular medium. Measurement of [Ca2+]m with rhod-2 in permeabilized myotubes has been described in Szalai et al. 2000. Fluorescence intensity of fluo-3 and rhod-2 reflecting [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m are depicted on linear green and red scales, respectively. Confocal image time series shows the spatiotemporal pattern of [Ca2+] responses evoked by a RyR activator, caffeine. [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m spikes propagated through the myotubes as waves (middle row of images shows the first wave, whereas the lower row of images shows the second wave). Graphs show corresponding traces of [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m calculated for the regions marked by boxes on the image in the upper row. f.a.u., fluorescence arbitrary units.

A quantitative estimate of the amount of calcium utilized in mitochondrial signalling during IP3R- or RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c spikes has not been determined. Babcock, Hille and coworkers calculated that during a [Ca2+]c rise to 1.5 μm 70 % of the initial Ca2+ load is cleared first to the mitochondria in adrenal chromaffin cells (Babcock et al. 1997; Babcock & Hille, 1998). To measure the fraction of released Ca2+ utilized by the mitochondria during RyR- and IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signals, we used simultaneous fluorescence imaging of mitochondrial and cytosolic [Ca2+] in permeabilized H9c2 myotubes and RBL-2H3 mast cells, respectively. When SR/ER Ca2+ mobilization was evoked by addition of saturating caffeine and IP3, mitochondria accumulated 26 and 50 % of the released Ca2+ in adherent, carefully permeabilized H9c2 myotubes and RBL-2H3 cells, respectively (Pacher et al. 2000). Since the mitochondrial matrix volume is a small fraction of the total intracellular volume (a few percent in most cell types and up to 15 % in cell types particularly rich in mitochondria such as hepatocytes), this Ca2+ uptake could allow elevation of [Ca2+]m well above the [Ca2+]c level. However, different Ca2+ buffering in cytosol and mitochondria (Babcock et al. 1997) and dynamic control of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (David, 1999; Kaftan et al. 2000) may also affect the magnitude of the [Ca2+]m rise. Based on the calibration of [Ca2+]m signals recorded with fluorescent Ca2+ tracers compartmentalized to the mitochondria and aequorin targeted to the mitochondria, peak [Ca2+]m values were reported between < 1 μm (Babcock et al. 1997) and > 500 μm (Montero et al. 2000) during IP3R- or RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c spikes. These vastly different values may result from difficulties in intramitochondrial calibration of Ca2+-sensitive probes and also from heterogeneity among mitochondria in location, Ca2+ uptake properties or Ca2+ buffering.

The role for local [Ca2+]c gradients in mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling has been underscored by studies in intact cells demonstrating that Ca2+ released to the cytosol in response to IP3 is transferred to the mitochondria much more effectively than [Ca2+]c increases induced by leakage of Ca2+ from the ER (Rizzuto et al. 1993, 1994; Hajnóczky et al. 1995) and that the [Ca2+] elevation brought about by IP3 in the mitochondrial intermembrane space is larger than the global [Ca2+]c rise (Rizzuto et al. 1998). The extension of [Ca2+]m measurements to permeabilized cells allowed direct comparison of the [Ca2+]m responses evoked by Ca2+ and IP3 addition and led to the findings that buffered [Ca2+]c similar to the global [Ca2+]c measured in stimulated intact cells results in a small [Ca2+]m rise, whereas IP3 causes a brisk and large [Ca2+]m rise (Rizzuto et al. 1993). Most of these points have also been confirmed for delivery of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release to the mitochondria in some models (Brini et al. 1997; Sharma et al. 2000; Szalai et al. 2000). Based on these data, activation of IP3R or RyR may yield local high [Ca2+]c gradients sufficient to facilitate rapid activation of Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria.

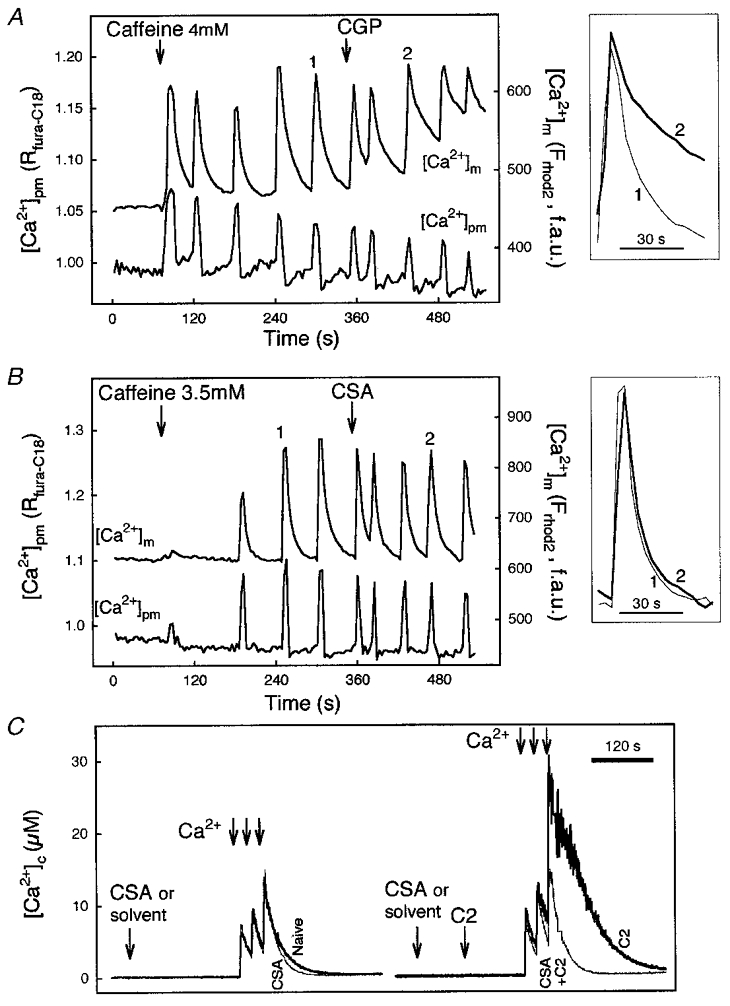

Recently much attention has been focused on the mechanisms underlying the relaxation phase of the [Ca2+]m signals. To identify the mechanisms that are responsible for the decay phase, inhibitors of the two main mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux pathways (Ca2+ exchanger and permeability transition pore (PTP)) have been utilized. In permeabilized H9c2 myotubes, an inhibitor of the Ca2+ exchanger, CGP37157, did not change the shape of the cytosolic transients or the frequency of cytosolic and mitochondrial spikes evoked by caffeine, but prolonged the decay phase of the [Ca2+]m spikes (Fig. 3A). By contrast, an inhibitor of PTP, cyclosporin A (CSA), failed to affect the relaxation phase of the [Ca2+]m spikes (Fig. 3B). Opening of the PTP causes dissipation of ΔΨm. Large CSA-sensitive mitochondrial depolarizations are frequently used as evidence for PTP opening (e.g. at the level of single mitochondria, Hüser et al. 1998), but the [Ca2+] oscillations and waves shown in Figs 2 and 3A and B never caused major depolarization on their own (Szalai et al. 2000; P. Pacher & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished data). Thus the Ca2+ exchanger appears to be important in decay of the RyR-mediated [Ca2+]m spikes in H9c2 myotubes, whereas activation of the PTP did not contribute to the mitochondrial Ca2+ egress. A similar picture has emerged in other cell types (Rizzuto et al. 1994; Brandenburger et al. 1996; Griffiths et al. 1997b; Szalai et al. 1999; Montero et al. 2000). However, it should be noted that the PTP has also been involved in mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux in physiological Ca2+ spiking in some cell types (Altschuld et al. 1992; Ichas et al. 1997; Fall & Bennett, 1999; Smaili & Russell 1999). In particular, Ichas and co-workers (1997) proposed that PTP-mediated Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the mitochondria may be important in amplification of the [Ca2+]c signal emitted by the SR/ER. Since opening of the PTP is controlled by a number of factors such as Ca2+, pH, adenine nucleotides, free radicals, ΔΨm and Bcl-2 family proteins the controversial data on the involvement of PTP in physiological [Ca2+]c transients may be related to differences in the contribution of the other regulators. This point is illustrated by the experiment shown in Fig. 3C. On the left side, permeabilized HepG2 hepatoma cells are shown to effectively buffer global [Ca2+] in the cytosolic medium during exposure to large Ca2+ pulses. (In contrast to the imaging experiments shown in Figs 1, 2, 3A and B, the amount of cells used in these suspension measurements is sufficient to control global [Ca2+] in the incubation medium.) The cells were pretreated with thapsigargin to prevent Ca2+ accumulation into the ER and the decay phase of the [Ca2+]c rise was completely abolished by inhibitors of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (data not shown), suggesting that mitochondria sequestered the added Ca2+. CSA added to inhibit PTP opening did not exert a major effect on the decay of [Ca2+]c pulses, suggesting that little if any PTP activation was evoked by the large amounts of Ca2+ taken up by the mitochondria. In contrast, if the cells were exposed to C2-ceramide, an apoptotic agent which exerts multiple effects on the mitochondria, Ca2+ pulsing yielded a large and relatively prolonged [Ca2+]c rise that was prevented by CSA (right). This suggests that C2-ceramide sensitizes PTP to Ca2+ accumulated to the mitochondria, thereby allowing activation of PTP by the IP3-induced [Ca2+]m signal (Szalai et al. 1999). Similar results have been obtained exposing the cells to stress by other means (staurosporin, GD3 ganglioside, reactive oxygen species, prolonged exposure to ethanol; Szalai et al. 1999; M. Madesh, P. Pacher & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished data). One mechanism to change the control of PTP by IP3-induced Ca2+ spiking appears to depend on activation of protein kinases or phosphatases (Hoek et al. 1995, 1997; M. Madesh & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished data). Thus, the mitochondrial Ca2+ load required for activation of PTP is decreased under various cellular stress conditions, increasing the contribution of PTP to the decay phase of IP3R- and RyR-mediated [Ca2+]m signals.

Figure 3. Ca2+ release from mitochondria in naive cells and in cells exposed to C2-ceramide.

A and B, time courses of perimembrane [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]pm) and [Ca2+]m, and responses evoked by caffeine in two individual rhod-2-loaded permeabilized myotubes. [Ca2+]pm was monitored using fura-C18. Effect of CGP 37157 (CGP, 10 μm; A) and cyclosporin A (CSA, 1 μm; B) on caffeine-induced [Ca2+] oscillations. Insets: [Ca2+]m spikes recorded prior to and after addition of the drug are shown by synchronizing the rising phase. Reproduced with permission from Szalai et al. (2000). C, effect of CSA on mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration evoked by Ca2+ pulsing (3 pulses, 25 μm CaCl2 each) in suspensions of naive (left) and C2-ceramide-pretreated (C2; 40 μm for 3 min; right) permeabilized HepG2 cells. In contrast to the imaging studies, intracellular Ca2+ stores were able to control global medium [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c) in the cell suspension studies, since the ratio of cell mass to bath volume was > 20 times larger than that in the imaging experiments. Measurements of [Ca2+]c were carried out using fura-2 FF/free acid added to the intracellular medium as described in Szalai et al. 1999. The Kd value of 3 μm was determined in intracellular medium (G. Csordás & G. Hajnóczky, manuscript in preparation) and used to translate the fura-2 FF fluorescence ratios to [Ca2+] concentrations.

Principles of Ca2+ signalling at the microdomain

Direct measurement of the local [Ca2+]c rise experienced by mitochondrial uptake sites at the relay domains and of the unitary [Ca2+]m signal in single mitochondria has not been accomplished. Recently, Duchen et al. (1998) reported transient depolarizations at the level of single mitochondria, called ‘flickers’ that were directly related to focal RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from SR in cardiac myocytes. Mitochondrial depolarization was probably due to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that may drive down ΔΨm via multiple mechanisms (direct effect of Ca2+ influx, [Ca2+]m-induced changes in metabolism, summarized in Loew et al. 1994; activation of PTP, Hüser et al. 1998). Thus, the microdomain generated by focal Ca2+ release appears to be sufficient to support mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in this model. Although resolution of the single mitochondrial [Ca2+]m changes evoked by elementary [Ca2+]c signals has not been achieved, [Ca2+]m elevations associated with global IP3R- and RyR-driven [Ca2+]c signals have been visualized in single mitochondria (Simpson et al. 1998; Csordás et al. 1999; Drummond et al. 2000) and these studies have provided information on regional distribution of the [Ca2+]m response and on the incremental detection properties of mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling.

To better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the local Ca2+ signalling at the SR/ER-mitochondrial junctions, studies have been carried out in carefully permeabilized cell models that provide direct access to the cytosolic domain of intracellular Ca2+ transport mechanisms and display rapid mitochondrial uptake of Ca2+ released from reticular stores (Biden et al. 1986; Rizzuto et al. 1993, 1994; Csordás et al. 1999; Hajnóczky et al. 1999; Sharma et al. 2000; Szalai et al. 2000). In permeabilized RBL-2H3 and H9c2 cells, the pharmacological profiles of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake suggest that it is mediated by the Ca2+ uniporter during rapid release from the reticular stores. Also, based on studies addressing the uniporter’s allosteric control by Ca2+-releasing agents we concluded that an IP3-dependent conformational change of the uniporter does not account for the stimulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Csordás et al. 1999). Most importantly, using 100-200 μm EGTA-Ca2+ buffer, the bulk [Ca2+]c could be clamped at the resting level during Ca2+ release evoked by activators of IP3R or RyR, but the increase of [Ca2+]m was observed even in the absence of any global [Ca2+]c increase (Csordás et al. 1999; Szalai et al. 2000). Taken together, these data are in support of the idea that the IP3R- or RyR-driven Ca2+ release led to activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized cells via generation of a localized large [Ca2+]c increase in the vicinity of the Ca2+ uniporters.

The magnitude of the local [Ca2+]c increases to which the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites are exposed during IP3R- or RyR-mediated Ca2+ release was estimated by measuring the rate of [Ca2+]m rise during Ca2+ release and comparing that with the rate obtained at varying concentrations of Ca2+ in the medium. Notably, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was not limited by the ΔΨm under the conditions used in these experiments (Szalai et al. 2000). In permeabilized RBL-2H3 cells, half-maximal activation was attained at a [Ca2+]c of ∼10 μm, and maximal activation required > 16 μm[Ca2+]c. Since the [Ca2+]m rise evoked by IP3-induced Ca2+ release was as steep as it was with the maximally effective concentration of [Ca2+]c, we concluded that the localized [Ca2+]c increase caused by IP3 is > 16 μm (Csordás et al. 1999). In permeabilized H9c2 myotubes, half-maximal activation was attained at ∼20 μm[Ca2+]c, and maximal activation required > 50 μm[Ca2+]c. The rate of [Ca2+]m rise elicited by synchronized activation of RyR was similar to that achieved with 30 μm added free [Ca2+]c, suggesting that the local [Ca2+]c rise sensed by the mitochondria is in the region of 30 μm (Szalai et al. 2000). Consistent with these results, the local [Ca2+]c between RyR and mitochondrial uptake sites was estimated to be 20-40 μm in chromaffin cells (Montero et al. 2000). Considering that the IP3R- and RyR-driven global [Ca2+]c spikes peak in the submicromolar range, the local [Ca2+]c elevation sensed by the uptake sites can reach values > 20-fold higher than the global increases of [Ca2+]c. Furthermore, this high local [Ca2+]c appears to control most of the uniporters that mediate Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized RBL-2H3 cells and H9c2 myotubes, whereas a smaller fraction (20-50 %) is highly responsive to IP3-induced Ca2+ release in MH75, HeLa and chromaffin cells (Rizzuto et al. 1994, 1998; Montero et al. 2000). Although these results reflect significant cell type-to-cell type differences, it appears that the proportion of SR/ER-mitochondrial interface area to the total mitochondrial surface area is smaller than the proportion of uptake sites exposed to high [Ca2+]c microdomains to the total number of uptake sites (see also above). Thus, one may conclude that mitochondrial uptake sites are concentrated at the mitochondrial membrane regions that are close to the SR/ER Ca2+ release sites.

In the microdomain, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites could be activated independently of each other by the Ca2+ flux through a single IP3R or RyR, similar to the connection between L-type Ca2+ channels and RyRs in the heart. An alternative mechanism is that populations of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites are controlled by populations of reticular Ca2+ release sites similarly to the synaptic transmission. One argument in favour of the latter mechanism is that cooperation has been demonstrated between Ca2+ release events supporting mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, since cooperation is not expected if release and uptake sites are coupled on a one-to-one basis (Csordás et al. 1999). Furthermore, based on the magnitude of the local [Ca2+]c rise experienced by the mitochondria and on the ability of millimolar EGTA/Ca2+ buffers to interfere with delivery of released Ca2+ to the mitochondria, we estimated that the average distance between the coupled RyR/IP3R and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites is probably in the region of 100 nm rather than < 20 nm (Csordás et al. 1999; Szalai et al. 2000). Microdomains of this size result from the superposition of several nearby channels. Thus, Ca2+ release through multiple release sites may be integrated at the level of individual mitochondrial uptake sites.

SR/ER Ca2+ uptake mediated by the sarco-endoplasmic Ca2+ pumps (SERCA) is important in the shaping of IP3R- or RyR-driven global [Ca2+]c signals, but owing to the substantially larger Ca2+ release flux through the activated release sites, there is little contribution of the SERCA, if any, during the initial rapid release phase. As such, activity of the SERCA was not anticipated to affect Ca2+ delivery to the mitochondria during concerted activation of the release sites and this assumption has been confirmed experimentally (Csordás et al. 1999). Interestingly, subcellular distribution of SERCA shows high density regions close to the mitochondria (Simpson & Russell, 1997; G. Csordás & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished data), suggesting that Ca2+ uptake by SERCA may be involved in local Ca2+ signalling. In an attempt to determine whether ER Ca2+ pumps can modulate the [Ca2+] near mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites without changing global [Ca2+]c, we carried out imaging of [Ca2+]m in adherent permeabilized single cells that were not able to control the global [Ca2+] at the cytosolic side owing to low cell density. In these experiments, pretreatment of the cells with a SERCA inhibitor, thapsigargin, resulted in a 2.4-fold increase in the initial rate of the [Ca2+]m rise evoked by addition of CaCl2 (3 μm), suggesting that SERCA-mediated Ca2+ uptake resulted in a decrease of the [Ca2+] mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites were exposed to. We also showed that increasing the strength of cytosolic [Ca2+] buffering attenuated the ability of SERCA inhibitors to increase the rate of [Ca2+]m rise induced by Ca2+ addition (G. Csordás & G. Hajnóczky, unpublished observations). These studies suggest that the high affinity and moderate capacity Ca2+ uptake via SERCA may exert a local control over [Ca2+]c in the vicinity of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites. This mechanism may be an important local scavenger of Ca2+ released through RyR/IP3R and may insulate mitochondria from modest [Ca2+]c elevations originating outside the junctions between SR/ER and mitochondria.

The features of the RyR/IP3R-mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling system summarized above suggest that the functional organization underlying SR/ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling is similar to synaptic transmission. Release of Ca2+ from the ER occurs in a quantal manner in response to IP3, in a similar way to neurotransmitter release in response to Ca2+ entry through voltage-operated Ca2+ channels. Microdomains of high [Ca2+] with a short lifetime are built up at the SR/ER-mitochondrial junctions, analogous to the large transients of neurotransmitter concentration in the synaptic cleft. Local reuptake of the messenger and diffusion are involved in the rapid clearance in both cases. Each mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake site is supported by Ca2+ release mediated by more than one IP3Rs, which is comparable with the fact that each postsynaptic receptor can be activated by neurotransmitter release from more than one synaptic vesicle. Furthermore, the coupling between IP3R and the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake site shows maximal efficiency in activation of the Ca2+ uniporter, just as maximal activation of the neurotransmitter receptors can be obtained during neurotransmitter release in the synapses. Constitutive release of Ca2+ during inhibition of the reuptake is poorly detected by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites, just as non-vesicular release of the neurotransmitter is detected with low efficiency at the synapses. Thus, Ca2+ signal transmission between intracellular organelles can show analogous behaviour to synaptic transmission.

An important area of future work will be to determine the role of cytosolic and mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ buffering in the local Ca2+ signalling between IP3R/RyR and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites. Since mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake depends on [Ca2+]c in a supralinear way, the cytosolic Ca2+ buffering capacity is anticipated to be a factor in Ca2+ signal propagation to the mitochondria (Neher, 1998). Cytosolic Ca2+ buffering exhibits substantial differences between different cell types (reviewed in Neher, 1995), adding to the complexity of mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling observed in intracellular perfusion and permeabilized cell experiments that involve dilution of cytosolic ingredients. Also, if the junctional surfaces of SR/ER and mitochondria are physically coupled and the transport of macromolecules is limited between the cleft and the bulk cytosol, the local Ca2+ buffering may be different from the global cytosolic Ca2+ buffering. Remarkably, Ca2+ buffering in the mitochondrial matrix is much larger than Ca2+ buffering in the cytosol (Babcock et al. 1997). In a recent study, David (1999) demonstrated that during electrical stimulation of nerve terminals the prolonged elevation in [Ca2+]c resulted in a sustained stimulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, but [Ca2+]m never exceeded a plateau level of ∼1 μm. He suggested that reversible formation of an insoluble calcium salt could account for stabilizing [Ca2+]m at a modestly elevated level. Buffering of intramitochondrial [Ca2+] may affect the activity of the Ca2+ uptake sites as well as activation of the mitochondrial Ca2+ release sites by accumulated Ca2+ and in turn, it may also modulate local Ca2+ signalling in the microdomain between the SR/ER Ca2+ release sites and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites.

Conclusion

Local interactions between SR/ER and mitochondria enable rapid propagation of IP3R/RyR-driven [Ca2+]c signals to the mitochondria. Localization of effectors close to the source of the calcium signal emerges as a common mechanism underlying activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites and several other Ca2+-regulated targets (e.g. enzymes, ion channels and elements of the exocytotic machinery), but at the molecular level, different designs of the local signalling are possible in each case. Recent developments suggest that in the SR/ER membrane facing mitochondria, IP3 or ryanodine receptors are concentrated into clusters and form functional units that communicate with juxtapositioned mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites. Based on circumstantial evidence, concerted opening of the release channels yields exposure of the mitochondrial uptake sites to tens of micromolar [Ca2+]c that is sufficient for optimal activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. SR/ER Ca2+ pumps strategically localized at the junctions may also contribute to the local interplay between ER and mitochondria by stabilizing a low local [Ca2+]c in the absence of coordinated opening of the Ca2+ release channels. Further insight into SR/ER-mitochondrial calcium coupling will be gained by uncovering and modifying the molecular structure of the mitochondrial Ca2+ transport sites, by direct visualization of the fundamental perimitochondrial and mitochondrial [Ca2+] signals and by computer modelling of the likely [Ca2+] changes in the junctional space and mitochondria.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Suresh K. Joseph for critical reading of the manuscript and Timothy Schneider for his help with the electron microscopy. This work was supported by a Grant-In-Aid from the American Heart Association and grants from the NIH to G.H. G.H. is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences. P.P. is a recipient of a Juvenile Diabetes Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

- Altschuld RA, Hohl CM, Castillo LC, Garleb AA, Starling RC, Brierley GP. Cyclosporin inhibits mitochondrial calcium efflux in isolated adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:1699–1704. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock DF, Herrington J, Goodwin PC, Park YB, Hille B. Mitochondrial participation in the intracellular Ca2+ network. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;136:833–844. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock DF, Hille B. Mitochondrial oversight of cellular Ca2+ signalling. Current Opinions in Neurobiology. 1998;8:398–404. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani RA, Bassani JW, Bers DM. Mitochondrial and sarcolemmal Ca2+ transport reduce [Ca2+]i during caffeine contractures in rabbit cardiac myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;453:591–608. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereiter-Hahn J, Voth M. Dynamics of mitochondria in living cells: shape changes, dislocations, fusion, and fission of mitochondria. Microscopy Research and Technique. 1994;27:198–219. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070270303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P. Mitochondrial transport of cations: channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:1127–1155. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Perez-Reyes E. Ca channels in cardiac myocytes: structure and function in Ca influx and intracellular Ca release. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;42:339–360. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biden TJ, Wollheim CB, Schlegel W. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in clonal pituitary cells (GH3). Translocation of Ca2+ into mitochondria from a functionally discrete portion of the nonmitochondrial store. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:7223–7229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitier E, Rea R, Duchen MR. Mitochondria exert a negative feedback on the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves in rat cortical astrocytes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;145:795–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger Y, Kennedy ED, Python CP, Rossier MF, Vallotton MB, Wollheim CB, Capponi AM. Possible role for mitochondrial calcium in angiotensin II- and potassium-stimulated steroidogenesis in bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5544–5551. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes R, Bers DM. Intracellular Ca2+ increases the mitochondrial NADH concentration during elevated work in intact cardiac muscle. Circulation Research. 1997;80:82–87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M, De Giorgi F, Murgia M, Marsault R, Massimino ML, Cantini M, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Subcellular analysis of Ca2+ homeostasis in primary cultures of skeletal muscle myotubes. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1997;8:129–143. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Nicholls DG. Mitochondria, calcium regulation, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;67:2282–2291. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon E, Ohata H, Harper IS, Trollinger DR, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial free calcium transients during excitation-contraction coupling in rabbit cardiac myocytes. FEBS Letters. 1996;382:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G, Thomas AP, Hajnóczky G. Quasi-synaptic calcium signal transmission between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. EMBO Journal. 1999;18:96–108. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G. Mitochondrial clearance of cytosolic Ca2+ in stimulated lizard motor nerve terminals proceeds without progressive elevation of mitochondrial matrix [Ca2+] Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:7495–7506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond RM, Mix TC, Tuft RA, Walsh JV, Jr, Fay FS. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis during Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release in gastric myocytes from Bufo marinus. The Journal of Physiology. 2000;522:375–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond RM, Tuft RA. Release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum increases mitochondrial [Ca2+] in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.139aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR. Contributions of mitochondria to animal physiology: from homeostatic sensor to calcium signalling and cell death. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.001aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Leyssens A, Crompton M. Transient mitochondrial depolarizations reflect focal sarcoplasmic reticular calcium release in single rat cardiomyocytes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;24:975–988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall CP, Bennett JP., Jr Visualization of cyclosporin A and Ca2+-sensitive cyclical mitochondrial depolarizations in cell culture. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1410:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel DD, Tsien RW. An FCCP-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurons and its participation in stimulus-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:4007–4024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04007.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EJ, Stern MD, Silverman HS. Measurement of mitochondrial calcium in single living cardiomyocytes by selective removal of cytosolic indo 1. American Journal of Physiology. 1997a;273:C37–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EJ, Wei SK, Haigney MC, Ocampo CJ, Stern MD, Silverman HS. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium efflux by clonazepam in intact single rat cardiomyocytes and effects on NADH production. Cell Calcium. 1997b;21:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter TE, Buntinas L, Sparagna GC, Gunter KK. The Ca2+ transport mechanisms of mitochondria and Ca2+ uptake from physiological-type Ca2+ transients. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1366:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnóczky G, Csordás G, Krishnamurthy R, Szalai G. Mitochondrial calcium signalling driven by the IP3 receptor. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2000;32:15–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1005504210587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnóczky G, Hager R, Thomas AP. Mitochondria suppress local feedback activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by Ca2+ Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:14157–14162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnóczky G, Lin C, Thomas AP. Luminal communication between intracellular calcium stores modulated by GTP and the cytoskeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:10280–10287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnóczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell. 1995;82:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek JB, Farber JL, Thomas AP, Wang X. Calcium ion-dependent signalling and mitochondrial dysfunction: mitochondrial calcium uptake during hormonal stimulation in intact liver cells and its implication for the mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1271:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00015-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek JB, Walajtys-Rode E, Wang X. Hormonal stimulation, mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, and the control of the mitochondrial permeability transition in intact hepatocytes. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1997;174:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M, Fanger CM, Lewis RS. Mitochondrial regulation of store-operated calcium signalling in T lymphocytes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;137:633–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüser J, Blatter LA, Sheu SS. Mitochondrial calcium in heart cells: beat-to-beat oscillations or slow integration of cytosolic transients? Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2000;32:27–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1005556227425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüser J, Rechenmacher CE, Blatter LA. Imaging the permeability pore transition in single mitochondria. Biophysical Journal. 1998;74:2129–2137. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichas F, Jouaville LS, Mazat JP. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell. 1997;89:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaconi M, Bony C, Richards SM, Terzic A, Arnaudeau S, Vassort G, Puceat M. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate directs Ca2+ flow between mitochondria and the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum: a role in regulating cardiac autonomic Ca2+ spiking. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11:1845–1858. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou MJ, Peng TI, Sheu SS. Histamine induces oscillations of mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration in single cultured rat brain astrocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:299–308. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouaville LS, Ichas F, Holmuhamedov EL, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD. Synchronization of calcium waves by mitochondrial substrates in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Nature. 1995;377:438–441. doi: 10.1038/377438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouaville LS, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, Rutter GA, Rizzuto R. Regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by calcium: Evidence for a long-term metabolic priming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaftan EJ, Xu T, Abercrombie RF, Hille B. Mitochondria shape hormonally induced cytoplasmic calcium oscillations and modulate exocytosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:25465–25470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolfi B, Curci S, Debellis L, Pozzan T, Hofer AM. Ca2+ homeostasis in the agonist-sensitive internal store: functional interactions between mitochondria and the ER measured in situ in intact cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;142:1235–1243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie AM, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Simpson AW. A role for calcium influx in the regulation of mitochondrial calcium in endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:10753–10759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew LM, Carrington W, Tuft RA, Fay FS. Physiological cytosolic Ca2+ transients evoke concurrent mitochondrial depolarizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12579–12583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack JG, Halestrap AP, Denton RM. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiological Reviews. 1990;70:391–425. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKrill JJ. Protein-protein interactions in intracellular Ca2+-release channel function. Biochemical Journal. 1999;337:345–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannella CA. Introduction: our changing views of mitochondria. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2000;32:1–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1005562109678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannella CA, Buttle K, Rath BK, Marko M. Electron microscopic tomography of rat-liver mitochondria and their interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum. Biofactors. 1998;8:225–228. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignery GA, Sudhof TC, Takei K, De Camilli P. Putative receptor for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate similar to ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1989;342:192–195. doi: 10.1038/342192a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata H, Silverman HS, Sollott SJ, Lakatta EG, Stern MD, Hansford RG. Measurement of mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration in living single rat cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:H1123–1134. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero M, Alonso MT, Carnicero E, Cuchillo-Ibanez I, Albillos A, Garcia AG, Garcia-Sancho J, Alvarez J. Chromaffin-cell stimulation triggers fast millimolar mitochondrial Ca2+ transients that modulate secretion. Nature Cell Biology. 2000;2:57–61. doi: 10.1038/35000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. The use of fura 2 for estimating Ca buffers and Ca fluxes. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1423–1442. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00144-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Usefulness and limitations of linear approximations to the understanding of Ca2+ signals. Cell Calcium. 1998;24:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Budd SL. Mitochondria and neuronal survival. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:315–360. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Meyer T. Reversible desensitization of inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release provides a mechanism for repetitive calcium spikes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:17253–17260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata H, Chacon E, Tesfai SA, Harper IS, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in cardiac myocytes during the excitation-contraction cycle: effects of pacing and hormonal stimulation. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1998;30:207–222. doi: 10.1023/a:1020588618496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Csordás G, Schneider TG, Hajnóczky G. Quantification of calcium signal transmission from sarco-endoplasmic reticulum to the mitochondria. The Journal of Physiology. 2000. in the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peng TI, Greenamyre JT. Privileged access to mitochondria of calcium influx through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;53:974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J. Molecular and cellular physiology of intracellular calcium stores. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:595–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong WF, Hunyady L, Varnai P, Wollheim CB, Spät A. Pyridine nucleotide redox state parallels production of aldosterone in potassium-stimulated adrenal glomerulosa cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:132–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong WF, Spät A, Wollheim CB. Dynamic pacing of cell metabolism by intracellular Ca2+ transients. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:27310–27314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Bastianutto C, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in intact cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;126:1183–1194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Brini M, Chiesa A, Filippin L, Pozzan T. Mitochondria as biosensors of calcium microdomains. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:193–199. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA, Pozzan T. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb-Gaspers LD, Burnett P, Rutter GA, Denton RM, Rizzuto R, Thomas AP. Integrating cytosolic calcium signals into mitochondrial metabolic responses. EMBO Journal. 1998a;17:4987–5000. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb-Gaspers LD, Rutter GA, Burnett P, Hajnóczky G, Denton RM, Rizzuto R, Thomas AP. Coupling between cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium oscillations: role in the regulation of hepatic metabolism. Biochimica at Biophysica Acta. 1998b;1366:17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohács T, Nagy T, Spät A. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ signalling and reduction of mitochondrial pyridine nucleotides in adrenal glomerulosa cells in response to K+, angiotensin II and vasopressin. Biochemical Journal. 1997;322:785–792. doi: 10.1042/bj3220785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustenbeck I, Eggers G, Munster W, Lenzen S. Effect of spermine on mitochondrial matrix calcium in relation to its enhancement of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1993;194:1261–1268. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter GA, Burnett P, Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T, Tavare JM, Denton RM. Subcellular imaging of intramitochondrial Ca2+ with recombinant targeted aequorin: significance for the regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:5489–5494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter GA, Theler JM, Murgia M, Wollheim CB, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. Stimulated Ca2+ influx raises mitochondrial free Ca2+ to supramicromolar levels in a pancreatic beta-cell line. Possible role in glucose and agonist-induced insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:22385–22390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Ross CA, Villa A, Supattapone S, Pozzan T, Snyder SH, Meldolesi J. The inositol 1,4,5,-trisphosphate receptor in cerebellar Purkinje cells: quantitative immunogold labeling reveals concentration in an ER subcompartment. Journal of Cell Biology. 1990;111:615–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu SS, Jou MJ. Mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration in living cells. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1994;26:487–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00762733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PB, Mehotra S, Lange GD, Russell JT. High density distribution of endoplasmic reticulum proteins and mitochondria at specialized Ca2+ release sites in oligodendrocyte processes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:22654–22661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PB, Mehotra S, Langley D, Sheppard CA, Russell JT. Specialized distributions of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum proteins define Ca2+ wave amplification sites in cultured astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;52:672–683. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980615)52:6<672::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PB, Russell JT. Mitochondria support inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ waves in cultured oligodendrocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:33493–33501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PB, Russell JT. Role of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+-ATPases in mediating Ca2+ waves and local Ca2+-release microdomains in cultured glia. Biochemical Journal. 1997;325:239–247. doi: 10.1042/bj3250239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VK, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, Sheu SS. Transport of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2000;32:97–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1005520714221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore GC, Tata JR. Two fractions of rough endoplasmic reticulum from rat liver. I. Recovery of rapidly sedimenting endoplasmic reticulum in association with mitochondria. Journal of Cell Biology. 1977;72:714–725. doi: 10.1083/jcb.72.3.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaili SS, Russell JT. Permeability transition pore regulates both mitochondrial membrane potential and agonist-evoked Ca2+ signals in oligodendrocyte progenitors. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:121–130. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer JR, Johnson EA. Comparative ultrastructure of cardiac cell membrane specializations. A review. American Journal of Cardiology. 1970;25:184–194. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparagna GC, Gunter KK, Sheu SS, Gunter TE. Mitochondrial calcium uptake from physiological-type pulses of calcium. A description of the rapid uptake mode. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:27510–27515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Brenner C, Larochettem N, Prevost MC, Alzari PM, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial release of caspase-2 and -9 during the apoptotic process. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999a;189:381–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999b;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svichar N, Kostyuk P, Verkhratsky A. Mitochondria buffer Ca2+ entry but not intracellular Ca2+ release in mouse DRG neurones. NeuroReport. 1997;8:3929–3932. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199712220-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalai G, Csordás G, Hantash B, Thomas AP, Hajnóczky G. Calcium signal transmission between ryanodine receptors and mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:15305–15313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalai G, Krishnamurthy R, Hajnóczky G. Apoptosis driven by IP3-linked mitochondrial calcium signals. EMBO Journal. 1999;18:6349–6361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei K, Stukenbrok H, Metcalf A, Mignery GA, Sudhof TC, Volpe P, De Camilli P. Ca2+ stores in Purkinje neurons: endoplasmic reticulum subcompartments demonstrated by the heterogeneous distribution of the InsP3 receptor, Ca(2+)-ATPase, and calsequestrin. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:489–505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00489.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CW. Inositol trisphosphate receptors: Ca2+-modulated intracellular Ca2+ channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1436:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Reese TS. Interactions among endoplasmic reticulum, microtubules, and retrograde movements of the cell surface. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 1994;29:291–300. doi: 10.1002/cm.970290402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Miller RJ. Regulation of the intracellular free calcium concentration in single rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:85–115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinel H, Cancela JM, Mogami H, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH. Active mitochondria surrounding the pancreatic acinar granule region prevent spreading of inositol trisphosphate-evoked local cytosolic Ca2+ signals. EMBO Journal. 1999;18:4999–5008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trollinger DR, Cascio WE, Lemasters JJ. Selective loading of Rhod 2 into mitochondria shows mitochondrial Ca2+ transients during the contractile cycle in adult rabbit cardiac myocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;236:738–742. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY, Bácskai BJ. Video-rate confocal microscopy. In: Pawley JB, editor. Handbook of Confocal Microscopy. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 459–478. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BS, Pfeiffer JR, Smith AJ, Oliver JM, Oberdorf JA, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Calcium-dependent clustering of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1998;9:1465–1478. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MP. The machinery of mitochondrial inheritance and behavior. Science. 1999;283:1493–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Matlib MA, Bers DM. Cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ signals in patch clamped mammalian ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:379–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.379bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]