Abstract

The intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) was monitored in fura-2-loaded myocytes isolated from the rat gastric antrum and voltage clamped at −60 1r1rqmV1qusing the perforated patch clamp technique. The rate of quench of fura-2 fluorescence by Mn2+ was used as a measure of capacitative Ca2+ entry.

Cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM) did not affect the holding current but produced a sustained elevation in steady-state [Ca2+]i that was dependent on the presence of external calcium. Cyclopiazonic acid increased Mn2+ influx with physiological external [Ca2+], but not in Ca2+-free conditions. Cyclopiazonic acid increased the rate of [Ca2+]i rise following a rapid switch from Ca2+-free to physiological [Ca2+] solution.

Sustained application of carbachol (10 μM) produced an elevation in steady-state [Ca2+]i that was associated with an increased rate of Mn2+ influx. Application of cyclopiazonic acid in the presence of carbachol further elevated steady-state [Ca2+]i without changing Mn2+ influx.

Ryanodine (10 μM) elevated steady-state [Ca2+]i either on its own or following a brief application of caffeine (10 mm). Cyclopiazonic acid had no further effect when added to cells pre-treated with ryanodine. Neither caffeine nor ryanodine increased the rate of Mn2+ influx. When brief applications of ionomycin (25 μm) in Ca2+-free solution were used to release stored Ca2+, ryanodine reduced the amplitude of the resulting [Ca2+]i transients by approximately 30 %, indicating that intracellular stores were partially depleted.

These findings suggest that continual uptake of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase into a ryanodine-sensitive store limits the bulk cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i under resting conditions. This pathway can be short circuited by 10 μm ryanodine, presumably by opening Ca2+ channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Depletion of stores with cyclopiazonic acid or carbachol also activates capacitative Ca2+ entry.

Inhibition of the uptake of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum produces an elevation of tension and intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in a number of smooth muscle preparations (Khalil & Van Breemen, 1990; Shima & Blaustein, 1992; de la Fuente et al. 1995; Petkov & Boev, 1996; Abe et al. 1996). At least four different mechanisms have been invoked to explain this. Some regard it as a Ca2+ release phenomenon, with blockade of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase allowing Ca2+ to escape from the intracellular stores and accumulate within the cytoplasm (Zhu et al. 1994). Inhibition of refilling might also lead to spontaneous depletion of the Ca2+ store, thus activating a capacitative or store-operated Ca2+ influx pathway (Missiaen et al. 1990; Munro & Wendt, 1994; de la Fuente et al. 1995; Wayman et al. 1996). Thirdly, it may be that a superficial buffer barrier mechanism normally limits basal [Ca2+]i by sequestering a fraction of the resting Ca2+ influx across the cell membrane (Chen & Van Breemen, 1993; reviewed in Van Breemen et al. 1995). Under these circumstances, blockade of uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum would allow more of the Ca2+ influx to enter the main cytoplasmic compartment of the cell. Finally, inhibition of Ca2+ uptake may prevent subsequent release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the sub-sarcolemmal space, and thus may inhibit membrane currents such as the Ca2+-sensitive K+ current (IK(Ca)) (Suzuki et al. 1992; Imaizumi et al. 1998). Decreased activation of IK(Ca) would lead to cell depolarization and the resultant opening of voltage-operated Ca2+ channels could explain an increased [Ca2+]i and tissue contraction. Such a mechanism has been described in vascular smooth muscle (Nelson et al. 1995) but can be disregarded as an explanation of the effects presented in this paper, all of which were observed under voltage clamp conditions. This technique was used to assess the remaining possibilities in rat gastric smooth muscle, focusing particularly on the relative importance of capacitative Ca2+ entry and the Ca2+ buffering function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

We have already demonstrated that blocking either Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, or Ca2+ release via ryanodine-sensitive channels increases the baseline [Ca2+]i in gastric myocytes, as well as increasing the rise in bulk [Ca2+]i produced by a given size of voltage-activated Ca2+ current (White & McGeown, 1998b). This second observation can be explained most easily on the basis of decreased Ca2+ buffering by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and it seems reasonable to suggest that a similar mechanism might account for the increase in basal [Ca2+]i produced by cyclopiazonic acid under resting conditions. This hypothesis requires further investigation, however, since depletion of the Ca2+ store with Ca2+-ATPase inhibitors has also been shown to activate additional Ca2+ influx in many tissues, including some types of smooth muscle (Missiaen et al. 1990; Wayman et al. 1996, 1998). To test between these options Mn2+ influx was used as a measure of capacitative Ca2+ entry (Hallam, 1988), and the effects of cyclopiazonic acid were studied using various protocols designed to alter the Ca2+ content of the intracellular store prior to inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump. This allowed the effects of blockade of the pump under conditions which caused an increase in sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx to be compared with those in which it did not. These comparisons suggest that influx is increased following inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake, but that this is not a prerequisite for the maintained rise in [Ca2+]i seen.

Preliminary reports of this work have been presented to The Physiological Society (White & McGeown, 1998a).

METHODS

Cell isolation, voltage clamp and [Ca2+]i recordings

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats 400–500 g in weight were killed by cervical dislocation, after being rendered unconcious through inhalation of a narcotic dose of CO2 in an induction chamber, as approved under Home Office regulations. The antral region of the stomach was then dissected out. Gastric myocytes were isolated enzymatically using collagenase (Sigma Type 1A, 13 mg (5 ml)−1), protease (Sigma Type XXIV, 1 mg (5 ml)−1), bovine serum albumin (10 mg (5 ml)−1) and trypsin inhibitor (9 mg (5 ml)−1). The perforated patch technique was applied, with amphotericin B (600 μg ml−1) in the pipette solution, and cells were voltage clamped at −60 mV (Axopatch 200A amplifier; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz, digitized, recorded and analysed using pCLAMP 5.0 software (Axon Instruments). All experiments were carried out at 35°C.

Measurements of intracellular [Ca2+] were made using fura-2 by first incubating the cells with fura-2AM (5 μM). They were then excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm at a rate of 20 counts s−1. Fluorescence output at 510 nm was recorded for each excitation wavelength (F340 and F380) using a Ratiomaster RF-F3011 (Photon Technology International, South Brunswick, NJ, USA) configured for microfluorimetry and mounted on a fluorescence inverted microscope (Diaphot 200, Nikon Instruments, Japan). A separate input channel on the computer interface of the microfluorimeter was used to record the output from the Axopatch amplifier so that simultaneously recorded current and fluorescence records could be synchronized.

At the end of each experiment cells were permeabilized with ionomycin (50 μM) and superfused with two EGTA (10 mM) buffered solutions, one containing no added Ca2+ and the other with a calculated free [Ca2+] of 1 mM (Maxchelator software 6.63, Chris Patton, Hopkins Marine Station, CA, USA, with constants from Brooks & Storey, 1992). The permeabilized cells were then exposed to Mn2+ (1 mM), which completely quenched the Ca2+-sensitive fura-2 signal and allowed the background fluorescence to be measured. The background corrected fluorescence ratio (R =F340/F380) was converted to [Ca2+]i using the equation of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985), i.e. [Ca2+]i=Kdβ(R – Rmin)/(Rmax–R). The procedure described above provided background corrected values for Rmin (R with nominally zero [Ca2+]), Rmax (R at saturating [Ca2+]) and β (F380 in zero [Ca2+]/F380 at saturating [Ca2+]) in each cell. A Kd of 287 nM was used, as determined by exposing ionomycin (50 μM)-treated cells to zero and 1 mM [Ca2+], plus eight EGTA-buffered solutions of known [Ca2+] in the range 10−7 to 10−6 m. Calibration attempts using saponin or alphatoxin to promote entry of EGTA failed due to rapid fura loss from the cytoplasm.

Mn2+ influx measurements

The rate of fura-2 quenching in the presence of extracellular Mn2+ was used as a measure of Mn2+ influx into the bulk cytoplasm in intact cells. The background corrected F340 and F380 outputs during a rapid change in [Ca2+]i were used to calculate a fluorescence value (Fi) which was unaffected by [Ca2+]i, using the method of Zhou & Neher (1993). Fi is defined by the equation:

| (1) |

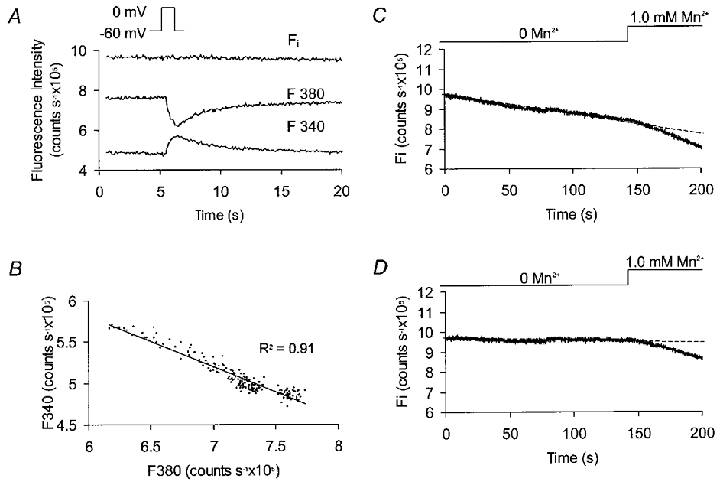

where α is the isocoefficient (Zhou & Neher, 1993), which equals the slope of the F340vs. F380 relationship during a rapid change in [Ca2+]i. The application of this is demonstrated for a cell which was depolarized from −60 to 0 mV for 1 s, inducing an inward Ca2+ current and a rapid rise in [Ca2+]i. This caused F340 to rise and F380 to fall as expected (Fig. 1A). The relationship between F340 and F380 was plotted for the 10 s following repolarization and the gradient of the best linear fit (α) was determined (Fig. 1B). Equation 1 was then applied to the corrected fluorescence data set to determine Fi at each time point. It can be seen that this value is independent of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Calculation of [Ca2+]-insensitive fluorescence (Fi) from fluorescence signals.

A, recorded fluorescence output at 340 nm (F340) and 380 nm (F380) for a single cell which was depolarized from −60 to 0 mV for 1 s. The resulting inward Ca2+ current (not shown) raised [Ca2+]i, producing divergent changes in fluorescence output. Fi was calculated from the recorded fluorescence using eqn (1) (see text). B, F340 plotted against F380 for each data point over the 10 s period immediately following repolarization. The gradient of the linear fit gives the value for α in eqn (1). C, changes in Fi for a single cell voltage clamped at −60 mV. In the absence of external Mn2+ there was a slow, linear decline. The rate of decay in Fi increased when external Mn2+ was added due to quenching of intracellular fura-2. D, the effects of Mn2+ influx can be isolated by correcting Fi to eliminate the Mn2+ independent, baseline decay.

Over longer periods of time Fi fell off linearly even in the absence of external Mn2+ (Fig. 1C), presumably due to dye loss and photobleaching (Becker & Fay, 1987). Correcting for this background decay gave a constant baseline prior to Mn2+ addition (Fig. 1D). Linear fits were applied to corrected data (Microsoft Excel) to determine the rate of Fi decay during superfusion with Mn2+ (1 mM). For summary purposes, the Mn2+-dependent fluorescence decay rate in the presence of a drug was always expressed as a percentage of the control rate in the same cell prior to drug addition.

Tension and [Ca2+]i measurements in tissue strips

Some experiments were carried out in which tension alone was measured from strips of rat stomach muscle superfused with solutions containing the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (10−7 M, 0.001 % DMSO). The temperature was held at 25°C to reduce spontaneous phasic activity and the external solution was switched between a modified Hanks’ solution (see below) containing 2 mM EGTA with no added CaCl2 and one in which the free [Ca2+] was calculated to be 70 nM (Maxchelator). Isometric tension changes were recorded using a force transducer (Pioden Controls Ltd, UK) whose output was amplified and digitized with a Maclab interface (Analog Digital Instruments Pty Ltd, Hastings, East Sussex, UK) and data stored and analysed on a Macintosh personal computer.

Solutions and drugs

The following solutions were used.

Pipette solution (mM): CsCl, 133; MgCl2, 1.0; EGTA, 0.5; Hepes, 10; amphotericin B (300 μg ml−1).

Bath solutions (mM).

Physiologically modified Hanks’ solution: NaCl, 125; KCl, 5.36; glucose, 10; sucrose, 2.9; NaHCO3, 4.17; KH2PO4, 0.44; Na2HPO4, 0.33; MgCl2, 0.5; CaCl2, 1.8; MgSO4, 0.4; Hepes, 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. In nominally Ca2+-free Hanks’ solution this recipe was adjusted by substituting MgCl2 for CaCl2 and including EGTA (2 mM).

Manganese solution containing Ca2+: NaCl, 131.5; KCl, 5.9; glucose, 11.5; CaCl2, 1.8; MnCl2, 1.0; Hepes, 11.6; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. MnCl2 was omitted from the relevant control solution. In Ca2+-free Mn2+ solution MgCl2 was substituted for CaCl2 and EGTA (5 mM) was added, while the total MnCl2 was increased to 3.0 mM. This was calculated to provide 1 mM free [Mn2+] under these conditions (Maxchelator software). MnCl2 was omitted from the relevant control solution.

Cyclopiazonic acid, ionomycin and A23187 were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and ryanodine in 50 % ethanol, to give 10−2 M stock solutions in each case. These were further diluted in extracellular perfusate to achieve the final concentration. DMSO and ethanol alone had no effects at concentrations well above those used (0.001–0.05 % v/v). Caffeine was dissolved directly in extracellular solution to give the final concentration required. All solutions were delivered through a custom-built multi-channel perfusion system which allowed complete exchange of the solution in the cell/tissue chamber in less than 10 s. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK) with the exception of fura-2 AM, which came from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA.

Analysis and statistics

Data have been summarized as the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Slopes were determined using a linear fit to minimize the sum of the squared differences between the data and the fitted line (Microsoft Excel). Differences between means for paired data sets were accepted as statistically significant at the 95 % significance level, as assessed using Student's paired or unpaired t test (for normally distributed data) or the Wilcoxon signed rank test (for paired data sets normalized to give percentage changes). Multiple comparisons within a data set were carried out using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and differences were again accepted as significant at the 95 % level, as assessed using Fisher's protected least significant difference test.

RESULTS

Effects of cyclopiazonic acid in the presence of physiological [Ca2+]

In single gastric myocytes voltage clamped at −60 mV and superfused with modified Hanks’ solution containing physiological [Ca2+], blockade of the Ca2+-ATPase in the sarcoplasmic reticulum using cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM) produced a persistent but reversible elevation of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2A). In nine such experiments [Ca2+]i rose from 65 ± 8 to 129 ± 10 nM (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test) and showed no sign of decaying back towards control levels over a period of 200 s. This rise was not associated with any measurable change in holding current (Fig. 2A) but the effect did appear to require Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma, since cyclopiazonic acid either had no effect (Fig. 2B; n = 10) or produced a small and transient rise in [Ca2+]i (n = 2) in cells which were perfused with Ca2+-free solution for 100 s prior to drug application. [Ca2+]i fell during washout of cyclopiazonic acid but seldom reached the original resting levels (data not shown).

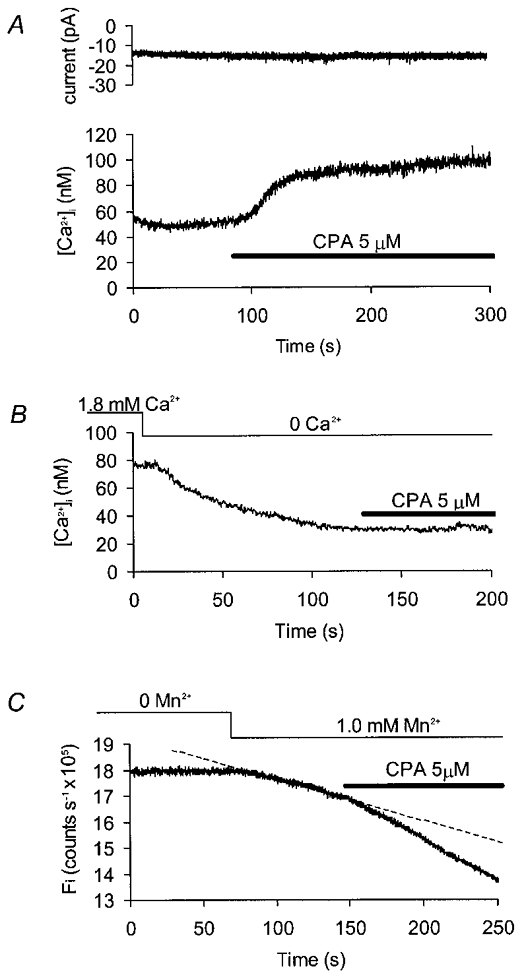

Figure 2. Effect of cyclopiazonic acid on basal [Ca2+]i and Mn2+ influx.

All records were made from gastric myocytes clamped at −60 mV. A, current (upper trace) and [Ca2+]i (lower trace) records under control conditions. Addition of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) to the superfusate produced a sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i without any obvious change in holding current. B, cyclopiazonic acid did not affect [Ca2+]i when applied after approximately 100 s exposure to zero external Ca2+. C, changes in the calculated [Ca2+]-independent fluorescence (Fi) in the presence of normal external Ca2+. Externally applied Mn2+caused a linear decline in fluorescence (the dashed line shows an extrapolated linear fit to these data). Addition of cyclopiazonic acid further increased the rate of decay.

Elevation of steady-state [Ca2+]i may be explained either by an increase in Ca2+ entry to the cell or a decrease in Ca2+ removal. Possible changes in the rate of Ca2+ entry were inferred from changes in Mn2+ influx, as estimated using quenching of fura-2 fluorescence (Hallam et al. 1988). In voltage clamped cells exposed to solutions containing physiological [Ca2+], the [Ca2+]i-independent fluorescence (Fi) declined linearly following addition of Mn2+ to the bath perfusate (Fig. 1D). When cyclopiazonic acid was added, the rate of quench was increased by a mean of 32 ± 10 % (Fig. 2C; P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed rank test, n = 6), presumably due to activation of a capacitative Ca2+ entry pathway permeable to Mn2+ (Fasolato et al. 1993).

Cyclopiazonic acid modulates the effects of step changes in external [Ca2+]

From the results described above, it seemed likely that cyclopiazonic acid increased Ca2+ influx when applied in the presence of physiological external [Ca2+]. It was still possible, however, that some or all of the elevation in [Ca2+]i seen was due to decreased Ca2+ sequestration when uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum was blocked. That this might have been the case was suggested by experiments in which increases in tension were recorded from strips of gastric muscle permeabilized with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and exposed to a step in external [Ca2+] from zero to 70 nM (Fig. 3A). Cyclopiazonic acid (1 μM) increased both the maximum rate of tension rise and the peak increase in tension achieved, which was, on average, 0.67 ± 0.14 mN under control conditions and 1.27 ± 0.22 mN in the presence of the drug (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test, n = 10). Similarly, when external [Ca2+] was stepped from 0 to 1.8 mM in experiments using voltage clamped, non-permeabilized cells, both the rate of [Ca2+]i rise and the steady-state [Ca2+]i reached were increased by cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM; Fig. 3B). The rate of [Ca2+]i rise was estimated from a linear data fit over the first 5 s after the increase in external [Ca2+]. In a series of seven experiments, this increased from 1.3 ± 0.5 nM s−1 under control conditions to 2.3 ± 0.7 nM s−1 in the presence of the cyclopiazonic acid (P < 0.05; Student's paired t test). The peak, steady-state [Ca2+]i achieved in the presence of external Ca2+ was 91 ± 12 nM in cyclopiazonic acid-treated cells, as compared with 62 ± 11 nM under control conditions (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test, n = 8).

Figure 3. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid on responses to step changes in external [Ca2+].

A, tension records from a strip of stomach muscle permeabilized to Ca2+ using the ionophore A23187 (present in all solutions at 0.1 μM with 0.001 % DMSO vehicle). External [Ca2+] was stepped from 0 to 70 nM, and the resulting increase in tension was measured before (left trace) and during (right trace) perfusion of the organ bath with cyclopiazonic acid (1 μM). B, [Ca2+]i record from an intact, single gastric myocyte voltage clamped at −60 mV. The external [Ca2+] was stepped from zero to 1.8 mM (top line). This was repeated in the presence of cyclopiazonic acid. C, Fi plotted for a cell voltage clamped at −60 mV and superfused with a series of Ca2+-free solutions. External Mn2+ produced a linear decay in fluorescence which was extrapolated using a linear fit (dashed line). Addition of cyclopiazonic acid slightly reduced the decay rate in the absence of external Ca2+.

Although it seemed unlikely that cyclopiazonic acid could have affected the rate of Ca2+ influx in permeabilized muscle strips, it was still possible that some such mechanism could account for the increased global [Ca2+]i seen in intact cells on stepping from zero Ca2+ to physiological solution. This was tested using Mn2+ influx measurements in a Ca2+-free external solution. In contrast to the results reported with physiological [Ca2+] outside the cell (Fig. 2C), cyclopiazonic acid actually produced a small but statistically significant decrease in the rate of Mn2+ influx under Ca2+-free conditions (Fig. 3C), with a mean rate of quench after drug treatment equal to 88 ± 4 % of the control rate (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed rank test). This suggests that the increase in the rate of [Ca2+]i rise caused by cyclopiazonic acid when external [Ca2+] was stepped from zero did not result from an increase in Ca2+ influx. These results are consistent, therefore, with the idea that a fraction of the Ca2+ entering the cell can be diverted away from the bulk cytoplasm (and the contractile proteins) by uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The fact that cyclopiazonic acid produced different effects on Mn2+ influx depending on whether Ca2+ was included in the external solution or not was an interesting observation in its own right and has technical importance for the interpretation of similar measurements in other tissues. One possible explanation could be that Ca2+ stores empty spontaneously in Ca2+-free solution, fully activating any capacitative entry mechanism so that addition of cyclopiazonic acid has no further effect. The effect of Ca2+-free solution on store content was tested with caffeine (10 mM) and carbachol (10 μM). These produced repeatable increases in [Ca2+]i in the presence of external Ca2+, but the responses were almost completely abolished after 100 s superfusion with Ca2+-free solution (data not shown). Thus, when there is no external Ca2+ to allow refilling, the agonist-releasable stores deplete spontaneously in these cells.

Interaction of cyclopiazonic acid and carbachol- sensitive stores

The results presented so far indicate that cyclopiazonic acid can both increase Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma and decrease uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum in gastric myocytes. Attempts were made to separate these two effects using pharmacological manipulation of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Application of carbachol (10 μM) produced an initial, transient peak followed by a sustained elevation of basal [Ca2+]i during the period of application of the drug (Fig. 4A), with a mean baseline rise of 34 ± 3 nM (P < 0.01; ANOVA, n = 6). When cyclopiazonic acid was added to these carbachol-treated cells [Ca2+]i increased, on average, by a further 59 ± 10 nM (P < 0.01; ANOVA, n = 6). The fact that these drugs had additive effects suggests that they act through at least partially independent mechanisms. No consistent changes in membrane current were observed in these experiments (Fig. 4A).

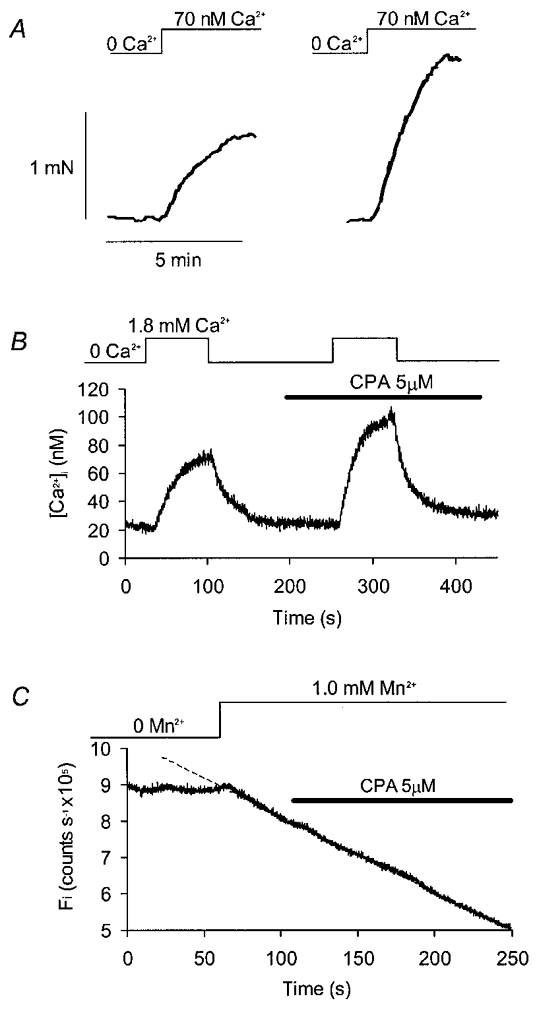

Figure 4. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid on cells pretreated with carbachol.

A, current (upper record) and [Ca2+]i (lower record) for a voltage clamped cell exposed first to carbachol (10 μM) and then to cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM) in the maintained presence of carbachol. B, Fi plotted for another cell clamped at −60 mV and superfused with a series of solutions containing physiological [Ca2+]. External Mn2+ produced a linear decay in fluorescence which was extrapolated using a linear data fit (dashed line). Carbachol increased the rate of this decay but addition of cyclopiazonic acid in the presence of carbachol had no further effect.

Carbachol increased the rate of Mn2+ influx in Ca2+-containing solutions (Fig. 4B), accelerating fluorescence decay on average by 28 ± 8 % (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed rank test, n = 6). Cyclopiazonic acid had no additional effect on influx when applied in the presence of carbachol. Thus, cyclopiazonic acid can increase [Ca2+]i without increasing Ca2+ influx (at least as measured using Mn2+ quenching of fura) in cells exposed to physiological [Ca2+].

Interaction of cyclopiazonic acid and ryanodine- sensitive stores

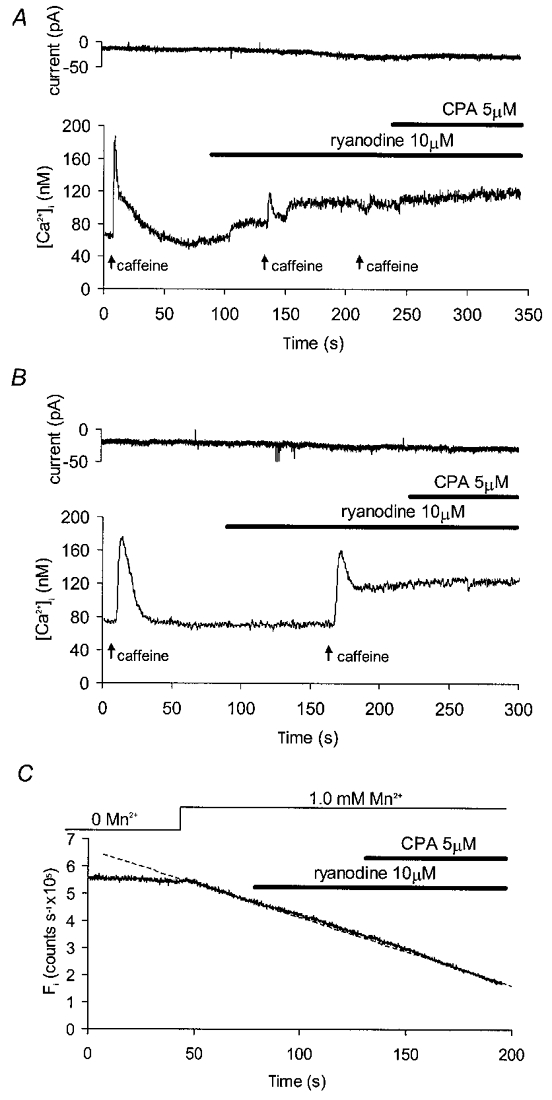

Further experiments were carried out to investigate the possible role of ryanodine-sensitive stores in the response to cyclopiazonic acid. When 10 μM ryanodine was continuously applied and caffeine (10 mM) then briefly superfused, two patterns of response were observed. In six out of ten cells studied, ryanodine alone caused a spontaneous increase in [Ca2+]i to a new steady state some 46 ± 3 nM above the original baseline (Fig. 5A; P < 0.001; Student's paired t test, n = 6). In the remaining 4 cells there was evidence of use dependence, since ryanodine alone caused little or no change in basal [Ca2+]i, but [Ca2+]i did not return to baseline after a brief addition of caffeine, remaining on average 53 ± 5 nM above control (Fig. 5B; P < 0.005; Student's paired t test, n = 4). Addition of cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM) in the presence of ryanodine had little further effect on [Ca2+]i in either group of cells (Fig. 5), with mean values of 152 ± 27 nM in ryanodine alone and 159 ± 21 nM after a further 100 s superfusion with ryanodine plus cyclopiazonic acid (n.s.; Student's paired t test, n = 5). Ryanodine itself had no effect on Mn2+ influx as estimated in the presence of physiological external [Ca2+] (Fig. 5C), with fluorescence decay rates in the presence of ryanodine (10 μM) averaging 95 ± 5 % of control (n.s.; Wilcoxon signed rank test, n = 7).

Figure 5. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid on cells pretreated with ryanodine.

A, current (upper record) and [Ca2+]i (lower record) for a voltage clamped cell (−60 mV) exposed to ryanodine. Brief (< 10 s) applications of caffeine (10 mM) were used to confirm successful blockade of the ryanodine-sensitive channels. Ryanodine alone raised [Ca2+]i but subsequent application of cyclopiazonic acid produced no additional effect. B, records for a second cell exposed to ryanodine and caffeine in which ryanodine produced a sustained rise in [Ca2+]i but only after a brief application of caffeine. Once again, cyclopiazonic acid produced no further effect. C, Fi plotted for a cell voltage clamped at −60 mV in normal [Ca2+] solutions. External Mn2+ produced a linear decay in fluorescence (dashed line), but this was unaffected by addition of ryanodine alone or in combination with cyclopiazonic acid.

Effect of ryanodine on Ca2+ store content

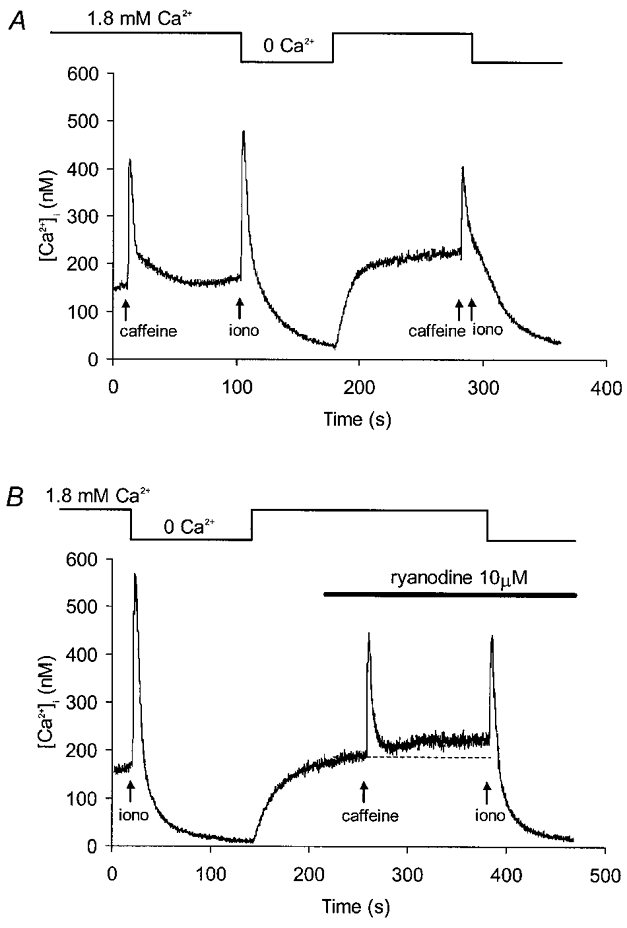

These results are consistent with the existence of a Ca2+ removal pathway involving uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase into a ryanodine-sensitive store. They do not tell us, however, whether ryanodine is acting to inhibit or promote store emptying. To test between these possibilities, ionomycin was used to dump the intracellular Ca2+ stores. Cells were not voltage clamped since the addition of ionophore produced dramatic changes in membrane conductance. Experiments were first carried out to demonstrate that ionomycin was indeed releasing stored Ca2+ (Fig. 6A). Caffeine (10 mM) was briefly applied under control conditions, and approximately 100 s later the superfusate was switched to a zero-Ca2+ solution containing 25 μM ionomycin. The resulting transient peaked in about 5 s and ionomycin was then washed out, allowing [Ca2+]i to decay to low levels (Fig. 6A). When returned to physiological [Ca2+] the stores were able to reload, as demonstrated by the response to a further application of caffeine. The mean amplitudes of caffeine transients evoked before and after ionomycin were 144 ± 28 and 127 ± 21 nM, respectively (n.s.; Student's paired t test, n = 6). Ionomycin was then re-applied in zero Ca2+, shortly after the second caffeine administration, at a time when [Ca2+]i was close to baseline. This did not produce any measurable rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6A).

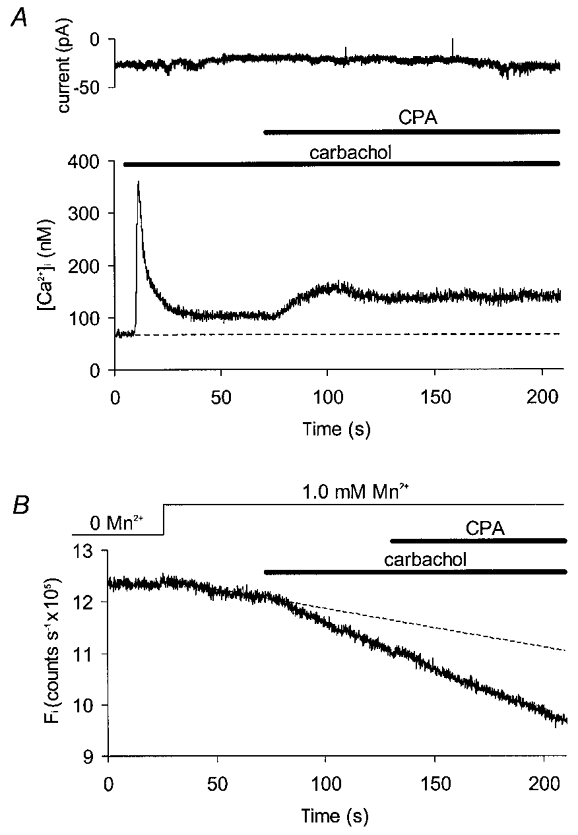

Figure 6. Effect of ryanodine on ionomycin releasable Ca2+ stores.

A, [Ca2+]i record from a control experiment. A test response to caffeine (10 mM) was followed by a recovery period in normal solution. This was followed by a rapid switch to Ca2+-free superfusate containing 25 μM ionomycin (iono; application time < 10 s) which was also washed out in Ca2+-free conditions. About 100 s after returning to normal Ca2+ solution, a second application of caffeine was followed by another switch to ionomycin in zero Ca2+. This produced no measurable rise in [Ca2+]i suggesting that ionomycin and caffeine were acting on the same intracellular Ca2+ stores. B, [Ca2+]i transients evoked by ionomycin in zero-Ca2+ solution before and during superfusion with ryanodine. Brief application of caffeine in the presence of ryanodine evoked a transient followed by sustained rise in [Ca2+]i.

Thus, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, ionomycin elevates [Ca2+]i by emptying intracellular stores. Following washout of ionomycin, store refilling and release mechanisms appear to be intact. Ionomycin was used, therefore, to assess Ca2+ store content before and after treatment with 10 μM ryanodine (Fig. 6B). As before, caffeine (10 mM) was applied briefly during the ryanodine superfusion because of the use dependence of the ryanodine effect (Fig. 5B). The ryanodine-dependent rise in steady-state [Ca2+]i was confirmed, with a mean increase of 48 ± 8 nM (P < 0.0005; Student's paired t test, n = 9). The average amplitude of the ionomycin-dependent transient was 193 ± 32 nM before exposure to ryanodine and 124 ± 21 nM in the presence of the drug (P < 0.05; Student's paired t test, n = 9). Thus, ryanodine produced a partial reduction in loading of the Ca2+ store under these experimental conditions.

DISCUSSION

Cyclopiazonic acid promotes Ca2+ influx and reduces Ca2+ buffering

The increase in basal [Ca2+]i can best be explained by postulating that cyclopiazonic acid has two effects on rat gastric muscle. The increase in Mn2+-dependent quenching of fura-2 fluorescence seen with physiological levels of external [Ca2+] (Fig. 2C) suggests that cyclopiazonic acid promoted store-operated Ca2+ entry, presumably as a response to spontaneous store depletion when reuptake was inhibited. This was not the sole mechanism involved, however, since cyclopiazonic acid still promoted a rise in [Ca2+]i under conditions in which it did not affect Mn2+ influx. For example, when added in the presence of carbachol, cyclopiazonic acid produced a mean rise in [Ca2+]i (59 ± 10 nM, n = 6; Fig. 4A), which was very similar to that seen following blockade of Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum under control conditions (64 ± 7 nM, n = 9, Fig. 2A; n.s., Student's unpaired t test). It also increased the rate of rise of both tension and [Ca2+]i on stepping from a low external [Ca2+] to a more physiological solution (Fig. 3A and B), even though it did not increase Mn2+ influx in the absence of external Ca2+ (Fig. 3C). We believe that this is explained by the spontaneous depletion of releasable stores seen after 100 s in zero external [Ca2+], since this would make it unlikely that cyclopiazonic acid could have any further effect on store content or related store-operated influx pathways. Appreciable releasable stores have been reported to persist in Ca2+-free conditions for much longer than this in other smooth muscles, ranging from 5–6 min in rabbit intestinal cells (Komori & Bolton, 1991) and rat myometrial tissue (Taggart & Wray, 1998), up to an hour or more in strips of rabbit aorta (Leijten & van Breemen, 1984). These tissue differences suggest that the rate of spontaneous store unloading is relatively fast in rat gastric myocytes, while the rate of reuptake of released Ca2+, in Ca2+-free conditions at least, is slow.

Since cyclopiazonic acid can increase [Ca2+]i without increasing influx, we propose that the sarcoplasmic reticulum normally buffers basal Ca2+ entry (van Breemen et al. 1995) and that blocking this leads to a rise in [Ca2+]i. This is consistent with the observation that cyclopiazonic acid increases the rise in bulk [Ca2+]i produced by a given Ca2+ influx during a step depolarization in this cell type (White & McGeown, 1998b). Such a mechanism requires that Ca2+ be continually released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and transported across the cell membrane without contributing to the bulk [Ca2+]i. There is no direct evidence for such a pathway in the present study but the additional elevation in [Ca2+]i produced by cyclopiazonic acid in the presence of carbachol (Fig. 4A) suggests that the sarcoplasmic reticulum's buffering role is maintained even under conditions in which Ca2+ release is maximally stimulated. Such a buffering mechanism can only have effect during Ca2+ entry across the sarcolemma, and so it is not surprising that cyclopiazonic acid did not change [Ca2+]i in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2B). Ryanodine completely abolished any additional effect of cyclopiazonic acid (Fig. 5), so uptake into a ryanodine-sensitive store appears to be important, but this does not exclude the possibility that inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate channels play a parallel role in the buffering pathway. Ryanodine can lock Ca2+ release channels open or shut in a concentration-dependent manner (Rousseau et al. 1987) and either action might explain a rise in basal [Ca2+]i. Ionomycin was used to test between these possible actions, and the resulting transient was reduced, on average, to 71 ± 10 % of control amplitude in the presence of 10 μM ryanodine. Caffeine completely abolished ionomycin-dependent release (Fig. 6A), suggesting that ryanodine depleted the releasable store, although only partially, presumably by increasing the mean number of open channels (Fig. 6B). This might be expected to cause leakage of stored Ca2+ into the cytoplasm and short circuit the cyclopiazonic acid-sensitive uptake mechanism, raising [Ca2+]i.

Activation of store-operated influx

Some of the fluorescence quench results reported here differ from those in earlier studies on vascular smooth muscle. For example, blockade of the Ca2+-ATPase with thapsigargin increased basal [Ca2+]i without increasing Mn2+ influx in rabbit vena cava (Chen & van Breemen, 1993), whereas we found influx to be increased when cyclopiazonic acid was applied to gastric myocytes under control conditions (Fig. 2C). This effect disappeared in Ca2+-free conditions (Fig. 3C), however, and these were the conditions used for all the Mn2+ influx measurements in the earlier thapsigargin study. Microfluorimetric estimates of Mn2+ entry are unlikely to detect influx into cell compartments other than the bulk cytoplasm, which accounts for most of the spatially averaged fura-2 signal (Etter et al. 1996). Thus, failure to detect a change in the rate of quenching cannot rule out the possibility of any increase in influx into some other cell compartment, e.g. the subsarcolemmal space. This does not invalidate our data, however, providing it is understood that they can only be safely interpreted in terms of the direct contribution of changes in influx to any measured change in bulk [Ca2+]i, since both [Ca2+]i and quench measurements are derived from the same fura-2 signal. Carbachol increased Mn2+ entry to the bulk cytoplasm, producing a sustained rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4), but ryanodine had no effect on Mn2+ influx. It is not safe to conclude, however, that this reflects a specific link between inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive stores and store-operated channels, since the apparently modest depletion of Ca2+ stores in the presence of 10 μM ryanodine (Fig. 6B) may have been inadequate to activate significant capacitative entry. One might have expected that addition of cyclopiazonic acid to ryanodine-treated cells would have completely depleted the stores, leading to store-operated influx, and yet there was no increase in [Ca2+]i or Mn2+ influx (Fig. 6). This observation remains to be investigated further but it does not undermine the main conclusion of the study, i.e. that resting cell [Ca2+]i is limited by uptake into a cyclopiazonic acid- and ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store.

We were unable to resolve any current due to a change in Ca2+ influx following store depletion with cyclopiazonic acid, carbachol or ryanodine (Figs 2, 4 and 5, respectively), even though the first two interventions increased Mn2+ influx. These results contrast with findings in many non-excitable tissue types in which blockade of Ca2+ uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum has a dramatic effect on Ca2+ entry, producing relatively large Ca2+ currents and a dramatic elevation of [Ca2+]i (reviewed in Parekh & Penner, 1997). There is also evidence that depletion of intracellular stores can activate a non-selective cation current in the smooth muscle of annococcygeus (Wayman et al. 1996, 1998). Presumably, any equivalent current in the rat gastric myocytes was either obscured by other currents or was too small to be reliably detected above background noise, which averaged about 2–3 pA. This seems likely, given that the depletion-operated currents in annococcygeus average 3.5 pA at −40 mV, even in the presence of 10 mM external [Ca2+] (Wayman et al. 1996). This current was activated both by carbachol and 3 μM ryanodine in mouse annococcygeus, but not by 30 μM ryanodine (Wayman et al. 1998), which suggests that the failure of ryanodine to increase Mn2+ influx in rat gastric myocytes may also be concentration dependent.

Conclusions

Our experiments suggest that the sarcoplasmic reticulum regulates basal global [Ca2+]i in rat gastric myocytes by two independent mechanisms. Uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump continuously diverts a significant fraction of the Ca2+ entering across the sarcolemma away from the bulk cytoplasm into a ryanodine-sensitive store. Depletion of the carbachol-sensitive store activated a capacitative Ca2+ entry pathway. It is difficult to assess the relative contributions of these two mechanisms to the rise in basal [Ca2+]i following treatment with cyclopiazonic acid, although the fact that pretreatment with carbachol failed to reduce the subsequent effect of cyclopiazonic acid suggests that inhibition of Ca2+ removal may be dominant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust and a Department of Education (Northern Ireland) funded research studentship to C.W.

References

- Abe F, Karaki H, Endoh M. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid and ryanodine on cytosolic calcium and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118:1711–1716. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker PL, Fay FS. Photobleaching of fura-2 and its effect on determination of calcium concentrations. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:C613–618. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.4.C613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SPJ, Storey KB. Bound and determined – a computer-program for making buffers of defined ion concentrations. Analytical Biochemistry. 1992;201:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Van Breemen C. The superficial buffer barrier in venous smooth muscle: sarcoplasmic reticulum refilling and unloading. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109:336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente P, Savineau J-P, Marthan R. Control of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle tone by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump blockers: thapsigargin and cyclopiazonic acid. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;429:617–624. doi: 10.1007/BF00373982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter EF, Minta A, Poenie M, Fay FS. Near-membrane [Ca2+] transients resolved using the Ca2+ indicator FFP18. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:5368–5373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasolato C, Hoth M, Penner R. Multiple mechanisms of manganese-induced quenching of fura-2 fluorescence in rat mast cells. Plügers Archiv. 1993;423:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00374399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero A, Fay FS, Singer JJ. Caffeine activates a Ca2+-permeable, nonselective cation channel in smooth muscle cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:395–422. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam TJ, Jacob R, Merrit JE. Evidence that agonists stimulate bivalent-cation influx into human endothelial cells. Biochemical Journal. 1988;255:179–184. doi: 10.1042/bj2550179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi Y, Torii Y, Ohi Y, Nagano N, Atsuki K, Yamamura H, Muraki K, Watanabe M, Bolton TB. Ca2+ images and K+ current during depolarization in smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig vas deferens and urinary bladder. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:705–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.705bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil RA, Van Breemen C. Intracellular free calcium-concentration force relationship in rabbit inferior vena-cava activated by norepinephrine and high K+ Plügers Archiv. 1990;416:727–734. doi: 10.1007/BF00370622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori S, Bolton TB. Calcium release induced by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in single rabbit intestinal smooth muscle cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;433:495–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leijten PAA, van Breemen C. The effects of caffeine on the noradrenaline-sensitive calcium store in rabbit aorta. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;357:327–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, Declerck I, Droogmans G, Plessers L, De Smedt H, Raeymaekers L, Casteels R. Agonist-dependent Ca2+ and Mn2+ entry dependent on state of filling of Ca2+ stores in aortic smooth muscle cells of the rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;427:171–186. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro DD, Wendt IR. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid on [Ca2+]i and contraction in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 1994;15:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev A, Knot H, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Penner R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:902–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov GV, Boev KK. The role of sarcoplasmic reticulum and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase in the smooth muscle tone of the cat gastric fundus. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431:928–935. doi: 10.1007/s004240050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr Capacitative calcium entry revisited. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:611–624. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90016-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau E, Smith JS, Meissner G. Ryanodine modifies conductance and gating behavior of single Ca2+ release channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:C364–368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.3.C364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima H, Blaustein MP. Modulation of evoked contractions in rat arteries by ryanodine, thapsigargin and cyclopiazonic acid. Circulation Research. 1992;70:968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehno-Bittel L, Sturek M. Spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release and extrusion from bovine, not porcine, coronary artery smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:49–78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Muraki K, Imaizumi Y, Watanabe M. Cyclopiazonic acid, an inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-pump, reduces Ca2+-dependent K+ currents in guinea-pig smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;107:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart MJ, Wray S. Contribution of sarcoplasmic reticular calcium to smooth muscle activation: gestational dependence in isolated rat uterus. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:133–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.133bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breemen C, Chen Q, Laher I. Superficial buffer barrier function of smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:98–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88990-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman CP, Gibson A, McFadzean I. Depletion of either ryanodine- or IP3-sensitive calcium stores activates capacitative calcium entry in mouse anococcygeus smooth muscle cells. Plügers Archiv. 1998;435:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s004240050506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman CP, McFadzean I, Gibson A, Tucker JF. Two distinct membrane currents activated by cyclopiazonic acid induced calcium store depletion in single smooth muscle cells of the mouse anococcygeus. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;117:566–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, McGeown JG. Calcium uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum limits steady-state cytoplasmic [Ca2+] in rat gastric myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1998a;511.P:164. P. [Google Scholar]

- White C, McGeown JG. Cyclopiazonic acid amplifies rather than attenuates depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients in rat gastric myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1998b;511.P:164–165. P. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Neher E. Mobile and immobile calcium buffers in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;469:245–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Tepel M, Neusser M, Zidek W. Role of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in agonist-induced changes in cytosolic Ca2+ in vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C794–799. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.3.C794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]