Abstract

The medial superior olive (MSO) is part of the binaural auditory pathway, receiving excitatory projections from both cochlear nuclei and an inhibitory input from the ipsilateral medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). We characterised the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents of MSO neurones in 3- to 14-day-old rats using whole-cell patch-clamp methods in a brain slice preparation.

A dual component EPSC was mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors. The AMPA receptor-mediated EPSC decayed with a time constant of 1.99 ± 0.16 ms (n = 8).

Following blockade of glutamate receptors, a monosynaptic strychnine-sensitive response was evoked on stimulation of the MNTB, indicative of a glycine receptor-mediated IPSC. GABAA receptors contributed to IPSCs in rats under 6 days old (bicuculline blocked 30% of the IPSC). In older rats little or no bicuculline-sensitive component was detectable, except in the presence of flunitrazepam. These glycinergic IPSCs showed a reversal potential that varied with changes in [Cl−]i, as predicted by the Nernst equation.

The IPSC exhibited two developmentally relevant changes. (i) At around postnatal day 6, the GABAA receptor-mediated component declined, leaving a predominant glycine-mediated IPSC. The isolated glycinergic IPSC decayed with time constants of 7.8 ± 0.3 and 38.3 ± 1.7 ms, with the slower component contributing 7.8 ± 0.6% of the peak amplitude (n = 121, 3–11 days old, −70 mV, 25°C). (ii) After day 11 the IPSC fast decay accelerated to 3.9 ± 0.3 ms (n = 12) and the magnitude of the slow component declined to less than 1%.

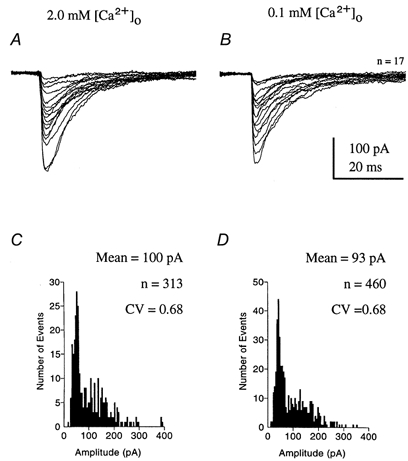

Spontaneous miniature glycinergic IPSCs (mIPSCs) were variable in amplitude and were of large conductance (1.83 ± 0.19 nS, n = 8). The amplitude was unchanged on lowering [Ca2+]o.

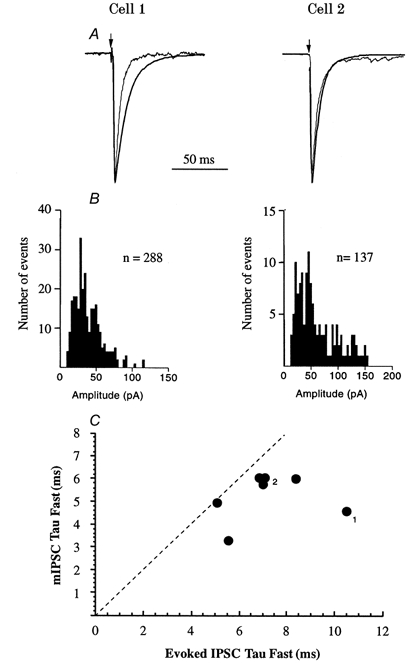

The time course of evoked and spontaneous miniature glycinergic IPSCs were compared. The 10-90% rise times were 0.7 and 0.6 ms, respectively. The evoked IPSC decayed with a fast time constant of 7.2 ± 0.7 ms, while the mIPSC decayed with a fast time constant of 5.3 ± 0.4 ms in the same seven cells.

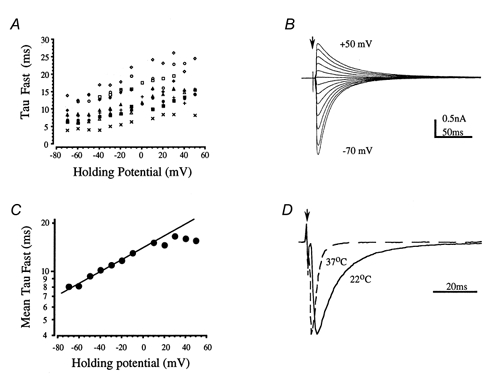

The glycinergic IPSC decay was voltage dependent with an e-fold change over 118 mV. The temperature dependence of the IPSC decay indicated a Q10 value of 2.1. Picrotoxin and cyanotriphenylborate had little or no effect on IPSCs from 6- to 14-day-old animals, implying homomeric channels are rare.

We conclude that the MSO receives excitatory inputs mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors and a strong glycinergic IPSC which has a significant contribution from GABAA receptors in neonatal rats. Functionally, the IPSC could increase membrane conductance during the decay of binaural glutamatergic EPSCs, thus refining coincidence detection and interaural timing differences.

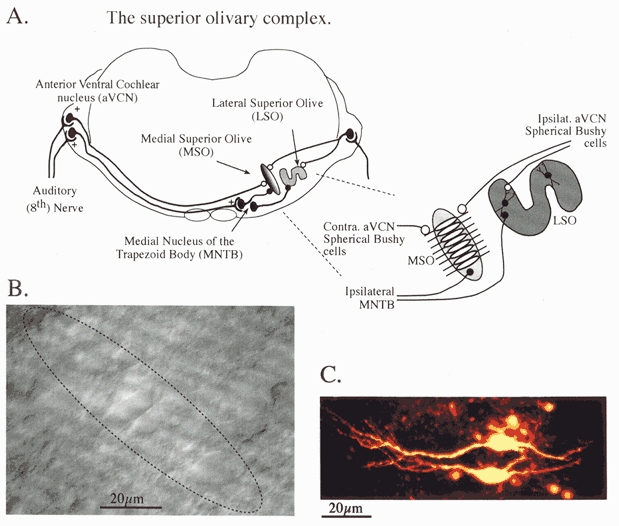

The superior olivary complex (SOC) performs the primary binaural processing in the auditory pathway underlying sound localisation. Within the SOC, the lateral superior olive (LSO) participates in interaural level discrimination (ILD) and the medial superior olive (MSO) is involved in interaural timing discrimination (ITD). ILD and ITD form complementary mechanisms for localisation of high and low (< 3 kHz) frequencies, respectively (Duplex theory, Rayleigh, 1907; Tsuchitani & Johnson, 1991). The binaural processing underlying both mechanisms requires very precise transmission of action potential timing information and the binaural auditory pathway possesses several specialisations that contribute to minimising latency fluctuation and maximising the security of transmission (Trussell, 1997). A schematic summary of the brainstem auditory pathways is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Excitatory projections originate from the bushy cells of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (aVCN). The globular bushy cells project to the contralateral medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) via the calyx of Held; and the spherical bushy cells project to the ipsilateral LSO and bilaterally to each MSO. The MNTB provides an inhibitory ipsilateral projection to both the MSO and the LSO (Spangler et al. 1985; Adams & Mugnaini, 1990; see Tsuchitani & Johnson 1991). Our aim in this paper was to examine the properties of the excitatory and particularly the inhibitory synaptic responses of MSO neurones.

Figure 1. The superior olivary complex.

A, the brainstem binaural auditory pathway in transverse section. The MSO which detects interaural timing differences (ITD) receives bilateral excitatory inputs (open circles) from spherical bushy cells in the anterior ventral cochlear nuclei and an inhibitory input (fillled circles) from the ipsilateral MNTB. The LSO, which detects interaural level differences (ILD) receives an excitatory projection from ipsilateral bushy cells and an inhibitory projection from the ipsilateral MNTB. Inset, detail of excitatory input from each aVCN, which project to opposing MSO dendrites. B, a differential interference contrast image taken through the experimental microscope showing rat MSO neurones in a transverse slice (200 μm thick). The extent of the MSO nucleus is suggested by the dotted line; it is 1 or 2 cell bodies wide and around 8-10 cells long. C, a confocal projection of Lucifer Yellow-filled MSO neurones showing the parallel dendritic arbours of 2 neighbouring cells extending in a bipolar orientation on opposing sides of the nucleus.

Jeffress’s (1948) proposal of a place theory for sound localisation discussed the possibility that the superior olivary nuclei could form the site for ITD detection; today the MSO is considered to be this binaural integration site (see Joris et al. 1998). The size and structure of the MSO and the difficulty in detecting it in vivo have resulted in no intracellular and relatively few extracellular studies of this region (see Goldberg & Brown, 1969; Yin & Chan, 1990). MSO neurones have a distinctive bipolar morphology; their cell bodies form a rostrocaudal sheet with opposing dendritic trees directed medially and laterally (Stotler, 1953; Smith, 1995). The lateral dendrites receive an excitatory input from the ipsilateral aVCN, whilst the medial dendrites receive a projection from the contralateral aVCN (Stotler, 1953; Clark, 1969; Lindsey, 1975). It is the summation of these excitatory responses, originating from the spherical bushy cells of the aVCN, that is thought to form the basis of coincidence detection in the delay line model of interaural timing discrimination (Joris et al. 1998). Examination of the MSO using brain slices from gerbil (Grothe & Sanes, 1993, 1994) and rat (Smith, 1995) shows that the binaural excitatory responses are subject to integration with inhibitory glycinergic IPSPs. However, most models of coincidence detection in the MSO do not incorporate inhibition.

Characterisation of glycine receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials formed the classical basis for our understanding of inhibition in the nervous system (Coombs et al. 1955), with glycine being the predominant inhibitory transmitter in the spinal cord and brainstem. The glycine receptor was the first ligand-gated ion channel to be isolated from the mammalian nervous system (Pfeiffer et al. 1982); the amino acid sequence and subunit composition have been determined (Grenningloh et al. 1987; Langosch et al. 1990) and are similar to those of nicotinic ACh and GABAA receptors (Schofield et al. 1987). To date, four α subunits and a β subunit have been identified (Betz, 1992) and are thought to be associated into functional channels with a 3:2 stoichiometry or possibly as homomeric α1 pentamers. The cochlear nucleus and superior olivary complex are known to possess high levels of glycine and glycine receptor immunoreactivity (Bledsoe et al. 1990; Kolston et al. 1992; Vater, 1995; Friauf et al. 1997). Anatomical, immunocytochemical and pharmacological evidence suggest that the MNTB inhibitory projections are glycinergic (Moore & Caspary, 1983; Adams & Mugnaini, 1990; Kuwabara & Zook, 1992; Smith, 1995) but this projection to the MSO has not been studied using voltage-clamp techniques.

We have characterised synaptic transmission at identified MSO neurones using patch-clamp recording from visualised cells in an in vitro brain slice preparation. Both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents possess multiple fast and slow time course components. The excitatory postsynaptic current was mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors and an inhibitory postsynaptic current was mediated predominantly by glycine receptors. A significant contribution from GABAA receptors was present, but declined at the end of the first week. Additionally, an acceleration in the glycinergic IPSC kinetics was associated with hearing onset at around postnatal day (P)11. The magnitude of the inhibitory synaptic response suggests that it has a major influence on synaptic processing in the MSO. Parts of this work have been published previously in abstract form (Smith & Forsythe, 1996).

METHODS

Brain slice preparation

Transverse brain slices of the SOC were prepared as previously described (Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1995). Briefly, 3- to 14- (mainly 7- to 10-) day-old Lister Hooded rats were killed by decapitation and the brainstem removed into cooled (0-4°C) low-sodium artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, see below). The brainstem was mounted in the chamber of a Campden Instruments vibrotome using a cyanoacrylate adhesive. Transverse slices (150-200 μm thick) were cut sequentially in the rostral direction from the level of the 7th nerve. The slices were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C in normal ACSF (see below). Following incubation, the slice maintenance chamber was allowed to cool to room temperature.

For recording, one slice was transferred to a Peltier controlled environmental chamber mounted on the stage of an upright M2A microscope (MicroInstruments). The microscope was fitted with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics and individual cells were visualised with a × 40 water-immersion objective (Zeiss, NA 0.7). The environmental chamber (∼300-400 μl volume) was maintained at 25°C and the slices were continuously perfused with normal ACSF at a rate of ∼1 ml min−1 using a peristaltic pump (Gilson, Minipuls 3). Drug and antagonist application were achieved by switching between one of four different perfusion lines, each of which passed directly into the recording chamber. The MSO nucleus was recognised in slices immediately rostral to the 7th nerve as a dorsoventrally orientated column of cell bodies that were more transparent than the surrounding tissue and situated between the MNTB and LSO (Fig. 1B). The size of the nucleus shows a large interspecies variation (Harrison & Irving, 1966) and is quite small in rats (around 600 cells). In our transverse brainstem slices the nucleus was approximately two soma diameters wide and between four and ten cells long in the dorsoventral axis. Confirmation of the recording site and morphology was achieved by including Lucifer Yellow (1 mg ml−1) in the pipette solution in some recordings. The cells shown in Fig. 1C were imaged using an MRC 600 confocal microscope (BioRad). MSO neurones have a bipolar morphology, with medial and lateral dendrites orientated in parallel with those of neighbouring cells (Stotler, 1953; Smith, 1995).

Solutions and drugs

The low-Na+, high-sucrose ACSF used for slice preparation contained (mm): 250 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 10 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 sodium pyruvate, 3 myo-inositol, 0.5 ascorbic acid, 2 MgCl2 and 1 CaCl2. The normal ACSF used for incubation and control perfusion media contained (mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 sodium pyruvate, 3 myo-inositol, 0.5 ascorbic acid, 2 CaCl2 and 1 MgCl2. The external solutions were bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2, giving a pH of 7.4.

Various internal chloride concentrations were achieved by proportional mixing of CsMeSO4 and CsCl-based patch solutions giving a final [Cl−]i of 132.5, 34.5 and 6 mm. The patch solution contained (mm): 130 CsMeSO4/CsCl, 10 Hepes, 5 EGTA and 1 MgCl2; pH 7.3. The external chloride concentration was 135 mm throughout. The following drugs were used: 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), (±)2-amino-5-phosphono-pentanoic acid (AP5), (+)MK-801 maleate and (-)bicuculline methochloride (from Tocris-Cookson); 5,7-dichlorokynurenate (from RBI); and tetrodotoxin (TTX), kynurenic acid, strychnine, Lucifer Yellow, flunitrazepam and picrotoxin (from Sigma).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp pipettes were made from thin-walled filamented borosilicate glass (Clark Electromedical Instruments, GC150TF-15) and the shank coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning). Recordings were made from visually identified MSO neurones. Neurones were voltage clamped using an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments) or a List EPC-7 amplifier. Mean series resistance was 12.2 ± 0.4 MΩ (n = 132, maximum 36 MΩ) and 60-80% series resistance compensation with 10 μs lag was routinely used. Data were filtered at 2.5 kHz with a low-pass 8-pole Bessel filter and digitised at between 5 and 20 kHz using a CED 1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) with Patch 6.0v acquisition and analysis software running on a PC. Glycinergic responses were isolated by adding 10 μm bicuculline, 5 μm CNQX, 50 μm AP5, 5 μm MK801 and 5 μm 5,7-dichlorokynurenate to the ACSF. In some experiments 5 mm kynurenic acid and 10 μm bicuculline were used to isolate the glycinergic IPSC. Miniature glycinergic IPSCs (mIPSCs) were recorded onto DAT (DTR-1404, Biologic) at a holding potential of -70 mV using patch solutions based on 130 mm CsCl (see above) and ACSF containing 1 μm TTX. In some cases evoked IPSCs were recorded and then the spontaneous events examined in the same cells following perfusion of TTX. Analysis of mIPSCs was conducted using Minianalysis 4.3.2 software (Synaptosoft) and Axograph 4.0 (Axon Instruments).

Evoked synaptic responses were generated using a bipolar platinum stimulating electrode (0.2 ms, 5-10 V) positioned over the ipsilateral MNTB and triggered by an isolated stimulator (DS2A, Digitimer). In animals under 6 days old stimulus voltages above 10 V were required. Success rates for evoking inhibitory synaptic responses using this technique were very good, with most MSO neurones showing IPSCs. Synaptic responses were generally recorded at a holding potential of -70 mV and evoked at a rate of 0.3 or 0.5 Hz. Data are quoted here as means ± s.e.m. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by Student’s t test. In the figures, traces are the average of at least 20 evoked responses (except the evoked responses in Fig. 4, 7 and 10 where 10 responses were averaged). Most experiments were conducted at 25°C. Q10 values were calculated from measurements taken over a range of temperatures between 22 and 37°C using:

| (1) |

where τ1 and τ2 are the decay time constants at T1 and T2, the control and test temperatures, respectively. Junction potentials were measured as 2.7 mV with symmetrical [Cl−], 5.3 mV with a [Cl−]i of 34.5 mm and 8.2 mV when [Cl−]i was 6 mm, and membrane potentials adjusted accordingly.

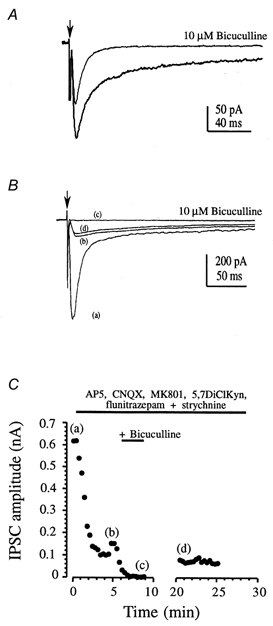

Figure 4. GABAA and glycine receptor-mediated IPSCs.

A, a bicuculline-sensitive IPSC was observed in MSO neurones from a 3-day-old rat. Averaged responses are illustrated under control conditions (in the presence of glutamate receptor antagonists) and following application of 10 μm bicuculline. Each record is the average of 10 traces. B, a small GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC was observed in rats over 7 days old in the presence of a benzodiazepine (4 μm flunitrazepam). Average traces are shown for control (a); following application of glutamate and glycine receptor antagonists (50 μm AP5, 5 μm MK801, 5 μm 5,7-dichlorokynurenate, 10 μm CNQX, 1 μm strychnine (b); following addition of 10 μm bicuculline (c); and recovery on washout of bicuculline (d). Arrow in A and B indicates stimulus artefact. C, the time course of the pharmacological blockade in B is shown as peak synaptic current plotted against time. Letters refer to the traces in B. Note that the response amplitude increase at around 4 min is due to an increase in stimulus intensity.

RESULTS

Basic properties of MSO neurones

The MSO was recognisable in one or two slices, immediately rostral to the 7th nerve; however, since it was only two soma diameters wide there were relatively few MSO neurones per slice. Some recording sites were identified through inclusion of Lucifer Yellow in the patch pipette. The MSO neuronal soma form a compact band of cells with bipolar dendrites orientated mediolaterally as shown in Fig. 1B and C. The MSO neurone zero-current potential measured soon after establishing the whole-cell recording was similar to the resting potential reported by Smith (1995) at -58.3 ± 1.1 mV (n = 10). MSO neurones had a large capacitance of 50.1 ± 9.5 pF (n = 13).

Synaptic responses evoked on MNTB stimulation

A bipolar stimulating electrode positioned over the MNTB activated both the MNTB neurones and some of the axons-of-passage from the contralateral aVCN (see Fig. 1). Thus, MNTB stimulation produced a mixed EPSC-IPSC postsynaptic response in the MSO. These mixed currents were large and of variable amplitude; in symmetrical [Cl−] the mean amplitude of the synaptic responses from five different cells was -5.7 nA at -70 mV.

Glutamatergic EPSC

Pharmacological isolation of the glutamatergic EPSC was achieved by perfusion of 10 μm bicuculline and 1 μm strychnine to block GABAA and glycine receptors, respectively. Under these conditions evoked EPSCs (in 6- to 10-day-old rats) were generated with a multiple decay time course, as shown in Fig. 2. A fast component reversed at +7.8 ± 1.4 mV (n = 4), while a slow EPSC exhibited voltage-dependent depression at negative holding potentials and reversed at +12.3 ± 2.3 mV (n = 4). The slow component was blocked by AP5 while the fast EPSC was blocked by CNQX (Fig. 2C and D). These data are consistent with the idea that AMPA and NMDA receptors, respectively, mediate the fast and slow EPSC components in MSO neurones. These receptors are likely to mediate the excitatory transmission from the spherical bushy cells of the aVCN. The decay time course of the AMPA receptor-mediated component was measured in the presence of AP5 at a holding potential of -70 mV. The decay possessed two components in eight cells; however, in four of these cells the slow component was less than 4% of the peak magnitude. The fast component decayed with a time constant of 1.99 ± 0.16 ms (n = 8) while the slower component decayed with a time constant of 17.3 ± 4.7 ms (n = 4); the fast component contributed 89.3 ± 3.3% of the peak amplitude in these four cells.

Figure 2. Excitatory synaptic responses are mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors.

EPSCs were evoked by midline stimulation in 6- to 10-day-old rats (in the presence of 1 μm strychnine and 10 μm bicuculline). A, average EPSCs were measured at different holding potentials as indicated to the right of each trace. Downward arrow indicates stimulus artefact; bipolar arrows indicate timing of current measurements used in B. B, the current-voltage relationship was measured at the peak of the fast EPSC (•) and the peak of the slow EPSC (○). The slow component exhibits negative slope conductance at voltages close to resting levels. C, at a holding potential of +40 mV the slow EPSC is reversibly blocked by 50 μmd/l-AP5. D, at a holding potential of -60 mV the fast EPSC is reversibly blocked by 10 μm CNQX (in the presence of AP5).

The IPSC is mediated by glycine and GABA receptors

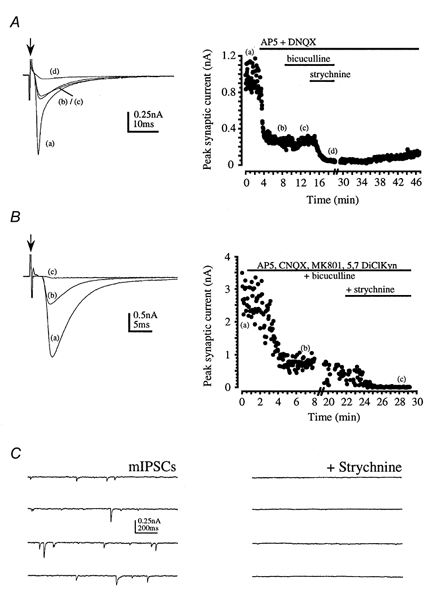

The monosynaptic inhibitory synaptic responses were isolated by perfusion of glutamate receptor antagonists (Fig. 3A). However, to minimise NMDA receptor activation, competitive and non-competitive antagonists were used: DNQX or CNQX (5-10 μm), AP5 (50 μm), MK801 (5 μm) and 5,7-dichlorokynurenate (5 μm), as shown in Fig. 3B. To minimise voltage-clamp errors, most experiments were conducted with synaptic responses of around 1-2 nA; however, with higher stimulus intensities IPSCs of up to 10 nA could be generated. In animals of 6-10 days old the evoked and spontaneous miniature synaptic currents were blocked by perfusion of 1 μm strychnine (Fig. 3) while bicuculline had no effect (n = 6, Fig. 3A). The strychnine block of glycine receptors was slow to reverse, but after a short application (40-60 s) and a long wash (10-40 min) some recovery of the IPSC was observed (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Glycine receptor-mediated IPSCs in 6- to 10-day-old rats.

Arrows indicate stimulus artefact and horizontal bars indicate drug application. A, average evoked synaptic responses (left) and peak response plotted against time (right) are shown under control conditions (a); and following perfusion of 50 μm AP5 + 10 μm DNQX (b); 10 μm bicuculline (c); and 1 μm strychnine (d). Some recovery from strychnine was observed after washing for 30 min. B, average evoked synaptic responses (left) and peak response plotted against time (right) are shown under control conditions (a); following perfusion of the glutamate receptor antagonists 50 μm AP5, 10 μm CNQX, 5 μm MK801, 5 μm 5,7-dichlorokynurenate (DiClKyn) and 10 μm bicuculline (b); and following application of 1 μm strychnine (c). C, spontaneous mIPSCs were observed in the presence of glutamate and GABAA receptor antagonists and 1 μm TTX (left). These mIPSCs were completely blocked by 1 μm strychnine (right).

In young animals under 6 days old, IPSCs in MSO neurones possessed a relatively large contribution from GABAA receptors. In eight cells from 3- to 5-day-old animals, the IPSC decay was fitted by a double exponential: a fast component with a time constant of 8.0 ± 0.6 ms and a slow component with a time constant of 65.2 ± 6.5 ms. The slow component contributed 27.2 ± 5.6% of the peak current. Bicuculline (10 μm) was applied to three cells, resulting in a depression of the IPSC in each case. The mean depression of the peak amplitude was 31.1 ± 11.5% and was in excess of 80% of the IPSC after 40 ms (see Fig. 4A). In these same three cells the IPSC fast decay time constant was unchanged by bicuculline (8.4 ± 1.1 ms in control and 7.7 ± 1.4 ms in bicuculline) but the magnitude of the slow decay component was significantly reduced from 39.3 ± 8.8 to 11 ± 3.9%. In the presence of bicuculline the magnitude of the slow decay component was not significantly different from that in animals aged 7-10 days. Although the proportion of peak current (30%) carried by GABAA receptors was large, the total magnitude of IPSCs in these young animals was small (mean, 0.57 ± 0.13 nA, n = 8). We conclude that there is a marked contribution from GABAA receptors to the IPSC in animals under 6 days old (Fig. 4A and 7A) with the MSO IPSC changing from a mixed glycine-GABA-mediated response to a glycine-mediated IPSC at the end of the first postnatal week.

Although GABAA receptor-mediated responses were usually undetectable in slices from animals over 6 days old, a small component could be measured following potentiation of GABAA receptors by flunitrazepam (Mellor & Randall, 1997; Jonas et al. 1998) as shown in Fig. 4B and C. A small bicuculline-sensitive current was seen in four out of five evoked IPSCs under these conditions. In the four positive recordings, the bicuculline-sensitive current accounted for 19 ± 6.5% of the peak IPSC amplitude. In the presence of flunitrazepam, the GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC had a time to peak of 4.6 ± 1.1 ms and decayed very slowly (half-decay time, 113 ± 22 ms). Under these conditions one might expect to see spontaneous mIPSCs (in the presence of TTX and glutamate receptor antagonists) with fast and slow decay time courses, reflecting the contribution of GABAA and glycine receptor-mediated components. However, since the isolated glycine receptor-mediated IPSCs themselves possess a slow component and the GABAA receptor-mediated components were of small magnitude, we could not unequivocally distinguish between mIPSCs that possessed glycine and/or GABAA receptor-mediated components.

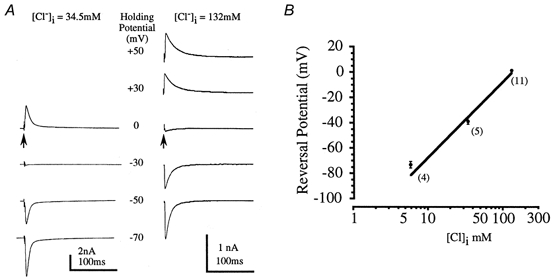

The glycinergic IPSC is generated by a chloride conductance

Isolated glycine receptor-mediated IPSCs were studied in all subsequent experiments following blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors. The reversal potential of the glycinergic IPSC confirmed that the conductance was carried by Cl− ions (Bormann et al. 1987) and was similar to that reported for the LSO of perinatal rats (Kandler & Friauf, 1995). Figure 5A shows averaged IPSCs generated over a range of holding potentials in two recordings with different concentrations of intracellular Cl−. In near-symmetrical [Cl−] solutions, the IPSC reversal potential was +1.6 ± 0.7 mV (n = 11; Cl− equilibrium potential, ECl, under these conditions was -0.3 mV). When [Cl−]i was lowered to 34.5 mm the reversal potential shifted to -37.9 ± 2.5 mV (n = 5) and on reducing [Cl−]i to 6 mm the reversal potential was -71.8 ± 2.5 mV (n = 4). Thus the IPSC reversal potential closely followed ECl, as shown in Fig. 5B.

Figure 5. The glycinergic IPSC reversal potential shifts with changes in [Cl−]i.

A, 2 different glycinergic IPSCs were recorded with [Cl−]i of 34.5 mm (left) and 132 mm (right). In each case the averaged IPSC was recorded at several holding potentials as indicated by the central scale. Arrows indicate stimulus artefacts. B, the reversal potential was plotted against log [Cl−]i. Mean data from 4-11 neurones (numbers in parentheses) are plotted (•) with the straight line indicating a 59 mV shift in reversal potential per 10-fold change in chloride ion concentration. Data from 6- to 10-day-old rats, in the presence of 10 μm bicuculline.

Time course of the glycinergic IPSC

The evoked glycinergic IPSC (recorded in the presence of 10 μm bicuculline and glutamate receptor antagonists) had a 10-90% rise time of 0.7 ± 0.1 ms and a half-width of 8.2 ± 0.7 ms (n = 9), in animals aged 6-11 days. The glycinergic IPSC decay had a double exponential time course: a fast component with a time constant of 7.8 ± 0.3 ms and a slow component that decayed with a time constant of 38.3 ± 1.7 ms (n = 12, animals aged 3-11 days, holding potential -70 mV). The slow component contributed 7.8 ± 0.6% of the peak IPSC magnitude.

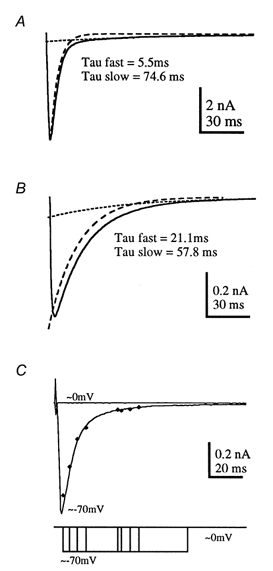

Although all evoked IPSCs exhibited a double exponential decay, the decay time constants showed more variation than we have previously observed with excitatory synaptic responses. The range of responses is illustrated in Fig. 6; a large IPSC shows a rapid decay (τ, 5.5 ms) while a small IPSC in another cell decays with a slower time constant of 21.1 ms (data from 8 cells are shown in Fig. 10A). The decay time constants showed no significant correlation with the current magnitude or series resistance. The dual decay time course was not due to voltage-clamp errors since we could confirm that the underlying synaptic conductance matched the measured IPSC time course using the methods of Pearce (1993). The IPSC was voltage clamped in symmetrical [Cl−] solutions at the reversal potential (around 0 mV). The voltage was then stepped to -70 mV over a sequence of times straddling the IPSC time course, as indicated by the voltage steps in Fig. 6C. Since the electrochemical gradient was maintained at zero until this command step, any current measured after stepping to -70 mV must reflect flow through open channels rather than passive redistribution from dendrites. The conductance generated during the fast and slow decay closely followed the current measured during continuous recording at -70 mV, as shown for one IPSC in Fig. 6C (filled diamonds). Similar results were observed for three other IPSCs. We conclude that the dual component conductance change underlying the glycinergic IPSC reflects a true conductance change and is not due to space-clamp errors.

Figure 6. IPSC decay time course reflects underlying synaptic conductance.

The isolated glycinergic IPSC decays with a dual exponential time course, with a fast decay time constant that was highly variable between different cells. Two examples are shown here: a rapidly decaying IPSC from a 9-day-old rat (A) and a more slowly decaying IPSC from a 7-day-old rat (B). The fast and slow exponential components are indicated by the dashed and dotted lines, respectively. C, the time course of the underlying conductance change was determined by voltage-jump experiments in which the potential was stepped from the IPSC reversal potential (0 mV) to -70 mV. When the membrane potential was maintained at -70 mV an inward current (the IPSC) was observed as shown by the averaged trace plotted as a continuous line. At the reversal potential no current change was measured throughout the synaptic response (upper trace, 0 mV). To assess the synaptic conductance, the voltage was stepped from 0 mV to -70 mV at intervals throughout the synaptic response. The peak current measured immediately following the step to -70 mV is plotted (filled diamonds) and overlies the measured IPSC time course, indicating that the measured current closely follows the time course of the underlying synaptic conductance. The voltage jumps are superimposed on the lower trace.

Figure 10. Comparison of glycinergic spontaneous mIPSC with evoked IPSC time course in the same neurones.

Two examples are shown (Cell 1 and Cell 2). A, normalised mIPSC and evoked IPSCs are superimposed. Arrows indicate the stimulus artefact. B, the amplitude and distribution of unitary mIPSCs are shown; the mean amplitude of mIPSCs in cell 1 was -37.2 pA and for cell 2 was -67.5 pA. C, the fast decay time constants for 7 MSO IPSCs are plotted against those of mIPSCs from the same cells. The dashed line indicates identical time courses; all evoked IPSCs decayed more slowly than mIPSCs. The numbers relate to the cells shown in A.

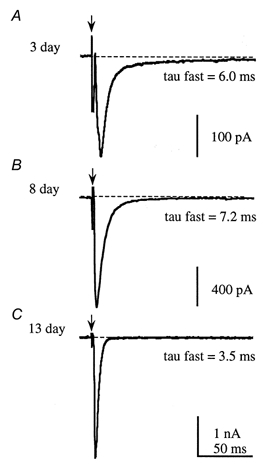

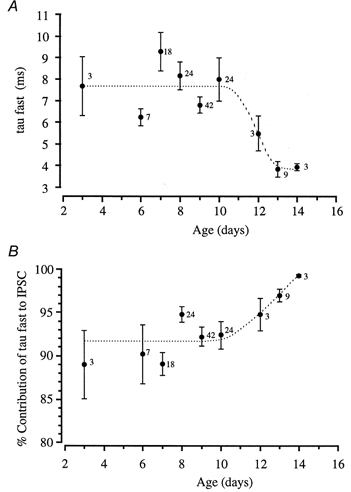

Glycinergic IPSC development

MSO IPSCs recorded from animals aged 3-14 days showed significant developmental changes. We measured both decay time constants and the relative contribution of the fast and slow components to peak IPSC amplitude, but we did not study absolute amplitude (since this is influenced by stimulus intensity and the slicing process, which might reduce IPSCs by severing dendrites). Example data traces from 3-, 8- and 13-day-old rats are shown in Fig. 7 and plots of the mean fast decay time constant and magnitude versus age are shown in Fig. 8. Two significant developmental changes were apparent: first, the decay kinetics accelerated and second, the contribution of the slow decay component declined. The fast IPSC kinetics accelerated after day 10 from around 8 ms to a mean value of 4 ms (Figs 7 and 8A). At around the same age the relative magnitude of the slow component declined to less than 1% of the IPSC peak amplitude by 14 days (Figs 7 and 8B). The slow decay time constant was highly variable but also showed significant acceleration after 10 days, changing from 38.8 ± 1.8 ms (n = 108, 7- to 10-day-old rats) to 25.8 ± 3.2 ms (n = 15) at 12-14 days old. The combined effect of these changes was to vastly decrease the duration of the IPSC, such that in some cases, decays could be fitted by a single exponential in 12- to 14-day old animals. Further work is required to overcome the technical difficulty of visualising and making patch recordings from the MSO in rats over 14 days old.

Figure 7. Glycinergic IPSC kinetics accelerates over the first 2 postnatal weeks.

A and B, in neonatal animals the IPSC has a dual component decay time course. C, at around the time of functional hearing onset (from day 11) there is an acceleration in the decay kinetics of the glycinergic IPSC and a decline in the contribution of the slow component to the IPSC decay. See text and Fig. 8 for mean values.

Figure 8. The developmental time course of the glycinergic IPSC.

A, the mean fast decay time constants are plotted against animal age. The fast decay time constant is slower in young animals, being around 8 ms from day 3 to day 10, but then shows a significant acceleration to 4 ms in 13- and 14-day-old animals. B, a plot of the percentage contribution of the fast component to total IPSC amplitude against animal age. The contribution of the slow IPSC decay time constant declines at around day 11, so that by day 14 the IPSC time course is dominated by the fast component (see trace in Fig. 7C). Numbers beside the data points indicate the number of neurones.

Glycinergic IPSC pharmacology

One possibility is that the fast and slow decay components represent current flow through glycine receptor ion channels possessing different subunit combinations, such as α1 and α2 (adult and fetal forms, respectively). Cyanotriphenylborate (CTB; Rundstrom et al. 1994) and picrotoxin (Pribilla et al. 1992; Lynch et al. 1995) are antagonists of α1-containing recombinant glycine receptor ion channels. Picrotoxin at 10 μm has also been reported to block large conductance glycine channels in zebrafish (Legendre, 1997). Attempts to pharmacologically differentiate between the channel subunits contributing to different components of the glycinergic IPSC were unsuccessful. In animals aged 6-10 days, 20 μm CTB reduced the peak IPSC current in one case by 26% (with no recovery), but in four other cases it had no effect (data not shown). We examined the effect of 10 μm picrotoxin on IPSCs in five MSO neurones (from animals aged 8-10 days) and found no change in the amplitude or time course of evoked glycinergic IPSCs (data not shown). Since both CTB and picrotoxin have a higher affinity for α1-containing channels (particularly homomeric channels), we repeated the experiments in animals aged 13 and 14 days. CTB (20 μm) had no effect in six out of seven IPSCs, with one IPSC being depressed by 55% (however, picrotoxin had no effect on the same IPSC). Picrotoxin (10 μm) had no effect in four out of five IPSCs and reduced one IPSC by 50%. These results imply that homomeric glycine receptors are unlikely to play a significant role in the mediation of MSO IPSCs.

Miniature IPSCs in MSO neurones

Glycinergic spontaneous mIPSCs were isolated by perfusion of TTX, glutamate receptor antagonists and 10 μm bicuculline. The striking features of these mIPSCs were their magnitude and variability. In eight cells the mean conductance was 1.83 ± 0.19 nS with a CV of 0.54 ± 0.19. Reduction of [Ca2+]o from 2 mm to 0.1 mm had no significant effect with the mean from six cells being 1.71 ± 0.13 nS and the CV being 0.69 ± 0.06. Example mIPSC traces and amplitude distributions from the same cell in 2 and 0.1 mm [Ca2+]o are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9. Glycinergic IPSCs.

Spontaneous miniature glycinergic IPSCs were observed in the presence of 1 μm TTX, glutamate receptor antagonists and 10 μm bicuculline. The mIPSCs were unaffected by reduction of [Ca2+]o. In the same cell, unitary responses are shown aligned to their rising phase under control conditions with 2 mm [Ca2+]o (A) and following perfusion of ACSF containing only 0.1 mm [Ca2+]o (B). C and D, the amplitude distribution for all mIPSCs recorded from the same cell with 2 and 0.1 mm [Ca2+]o, respectively, were similar and showed little or no change in amplitude or coefficient of variation (CV).

In the presence of bicuculline these mIPSCs were all blocked by 1 μm strychnine (Fig. 3C) indicating that no other transmitters were of significance. The time courses of evoked and miniature IPSCs were compared in the same cells; examples from two cells are shown in Fig. 10. In symmetrical [Cl−] at a holding potential of -70 mV, the mean mIPSC amplitude was 136.2 ± 16.6 pA (conductance, 1.94 nS) and the 10-90% rise times were 0.62 ± 0.11 ms in seven MSO neurones. Superimposed traces in Fig. 10A show the evoked IPSC and mIPSC normalised to their peak amplitude. The mIPSC amplitude distributions for the same cells are shown in Fig. 10B and a plot of the correlation between evoked and miniature IPSC fast decay time constants is shown in Fig. 10C for each of the seven MSO neurones; mean fast time constants were 7.2 ± 0.7 and 5.3 ± 0.4 ms, respectively. A second slow component of the mIPSC decay was present, as reported previously by Singer et al. (1998); in four cases the slow decay time constant was 16.5 ± 0.3 ms and contributed 26 ± 3.6% of the peak amplitude. In all cases the mIPSC decayed more rapidly than the evoked response, suggesting that, like excitatory synapses (Isaacson & Walmsley, 1995, 1996), the decay of the evoked response was in part determined by asynchronous transmitter release.

Voltage and temperature dependence of IPSC decay

Examination of the glycinergic IPSC decay time course over a range of voltages (-70 to +50 mV) confirmed previous observations (Stuart & Redman, 1990; Legendre, 1999) that these IPSCs are voltage dependent, decaying more slowly at positive voltages (Fig. 11A–C). A small voltage dependence was observed in each of 14 cases from 6- to 10-day-old rats. For the dominant fast component, an e-fold change in decay time was observed for a 118 mV change in membrane potential (Fig. 11B and C). The slower component displayed a similar voltage dependence, but this was difficult to quantify due to the relatively small contribution (less than 10%) of the slow component to the total synaptic current. In order to aid comparison with data from in vivo studies the temperature dependence of the IPSC time course was assessed over a range of 22-37°C, as shown in Fig. 11D. Calculation of the IPSC temperature dependence for four cells using eqn (1) gave a mean Q10 of 2.1 ± 0.2.

Figure 11. Voltage and temperature dependence of glycinergic IPSCs.

A, plot of the fast decay time constant against holding potential for 9 IPSCs from 6- to 10-day-old rats shows a similar trend to slower decays at depolarised potentials. B, averaged IPSCs from 1 cell recorded over a voltage range from -70 to +50 mV. The slower decays of the superimposed traces are obvious at positive holding potentials. C, mean decay time constants plotted on a logarithmic scale against voltage; the line is fitted over a voltage range of -60 to +10 mV and gives an e-fold change for 118 mV (n = 6-10). D, the temperature dependence of the IPSC time course is shown for an IPSC at both 22 and 37°C. The averaged traces have been normalised to their peak amplitude and superimposed with respect to the baseline current and the timing of the stimulus artefact. The fast decay time constants were 8.5 and 2.0 ms, respectively, giving a Q10 of 2.6.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify synaptic inputs to rat MSO neurones and then to isolate and characterise their inhibitory synaptic response on stimulation of the ipsilateral MNTB. Excitatory inputs generated a dual component EPSC mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors. Stimulation of the ipsilateral MNTB generated a monosynaptic IPSC, which was carried by a Cl− conductance through glycine receptors. The evoked IPSC had a significant GABAA receptor-mediated component in young rats, which declined after the first postnatal week. A second developmental change occurred at around the onset of functional hearing in rats (P11) and consisted of an acceleration of the fast IPSC decay time course and a decreased contribution from a slow time constant component, which dropped to less than 1% of the peak amplitude by 14 days.

The excitatory postsynaptic current

The EPSCs generated in MSO neurones originate from axons of the spherical bushy cells of the aVCN (Beckius et al. 1999). Stimulation around the midline/MNTB region generated an EPSC comprising a fast AMPA and a slow NMDA receptor-mediated current. The AMPA receptor component decayed predominantly with a fast exponential time course of 2 ms, somewhat slower than that observed in MNTB neurones (0.8 ms, Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1995). The slow component was of such small magnitude (< 4%) in half of the cells studied that it may have represented incomplete block of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC by the competitive antagonist AP5. The brainstem auditory pathway is known to express AMPA receptors exhibiting fast kinetics (Raman et al. 1994), with glutamatergic EPSCs elsewhere in the brain generally showing even slower kinetics. For example, EPSC decay time constants were 3.9 ms in cultured hippocampal neurones (Forsythe & Westbrook, 1988), 2.4 ms in visual cortex stellate cells (Stern et al. 1992) and 16-19 ms in hippocampal CA3 neurones (McBain & Dingledine, 1992). These differences reflect differential expression of AMPA receptor subunits (Mosbacher et al. 1994; Geiger et al. 1995; Ravindranathan et al. 2000). Additionally, channels that exclude edited GluRB subunits exhibit a high calcium permeability and rectification due to block by internal polyamines (Kamboj et al. 1995; Koh et al. 1995; Bowie & Mayer, 1995). Consistent with this observation, the MNTB synaptic AMPA receptors show rectification in the presence of internal polyamines (Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1996). The current-voltage relationship of the MSO EPSC also shows some rectification (see Fig. 2B).

Glycine receptor ion channels and IPSC time course

Isolated glycinergic IPSCs decayed with a double exponential time course with mean decay time constants of around 8 and 38 ms. The slow component accounted for about 8% of the peak IPSC amplitude in 7- to 10-day-old rats, but declined to less than 1% by 14 days. Assessment of the voltage control at the synaptic site using the method of Pearce (1993) revealed little voltage-clamp error, and the near-somatic location is consistent with the reported distribution of inhibitory synapses in the MSO (Clark, 1969; Adams & Mugnaini, 1990; Brunso-Bechtold et al. 1990; Vater, 1995). Unitary glycine receptor ion channels have been characterised in the spinal cord and brainstem and show multiple conductance states. The predominant conductance is generally around 40-50 pS (Bormann et al. 1987; Twyman & MacDonald, 1991) with larger conductances of over 80 pS in larval zebrafish (Legendre, 1997) and fetal spinal neurones (Takahashi et al. 1992). This may imply utilisation of homomeric ion channels in young animals since recombinant homomeric α1, α2 or α3 receptors exhibit unitary conductances of 85-110 pS, while channels incorporating β subunits have conductances of 45-55 pS (Bormann et al. 1993). A developmental shift, from expression of α2 in embryonic/neonatal animals to α1 in older animals (Becker et al. 1988; Friauf et al. 1997), has been implicated in the decreased open time of glycine receptor ion channels. Mean channel open times decrease from 40 ms at embryonic day (E)20 to 6.5 ms at P8 in rat spinal neurones (Takahashi et al. 1992), which is consistent with the faster time course of glycinergic IPSCs on maturation (Takahashi et al. 1992; Singer et al. 1998). However, in a recent comparison of glycine receptor ion channel properties using rapid application techniques and non-stationary variance analysis, single channel conductances were around 46-49 pS and showed no age-related difference from P1 to P18 (Singer & Berger, 1999). The overall increase in the rate of IPSC decay broadly agrees with the results of Singer et al. (1998) in brainstem motoneurones. Our time course measurements were conducted in the presence of bicuculline and hence we have defined (and exclude) any GABAA receptor-mediated contribution to our data set. Our data show that GABAA receptors made significant contributions to IPSCs in rats under 6 days old. The acceleration in the IPSC decay kinetics in animals less than a week old was due to a decrease in the relative contribution by GABAA receptors rather than a change in glycine IPSC kinetics.

Our attempts to exploit differences in the pharmacological sensitivity of recombinant glycine subunits were unsuccessful. CTB has been shown to non-competitively antagonise recombinant α1 homo-oligomers (Rundstrom et al. 1994) with a much lesser effect on α2 subunits. CTB at 10-20 μm had little or no effect on evoked IPSCs from 6- to 10-day-old and 13- to 14-day-old rats. Local puffer application of 10 mm CTB can depress glycine currents generated in MNTB neurones after the first postnatal week (Kungel & Friauf, 1997) but it is unclear whether such a high dose is specific. The GABA receptor antagonist picrotoxin also blocks glycine receptor α1 subunits (Lynch et al. 1995) at concentrations of around 10 μm and reduces the open probability of the high-conductance substate in native glycine receptors from zebrafish larvae (Legendre, 1997). Histochemical studies suggest that there is little α1 immunoreactivity in rat MSO until after P8 (Friauf et al. 1997). We noted an acceleration of the decay kinetics of the glycinergic IPSC from around P11, accompanied by a reduction in the contribution of the slow component. This coincides with the opening of the auditory canal and hearing onset in rats (Geal-Dor et al. 1993). Other developmental changes in [Cl−]i also have a major impact on inhibitory synaptic development (Kandler & Friauf, 1995; Ehrlich et al. 1999) and must also be considered when examining the physiological role of glycine receptors.

Co-localisation of GABA and glycine

There is recent evidence for the co-localisation and release of GABA and glycine from inhibitory neurones in spinal cord, brainstem and auditory pathway. Schneider & Fyffe (1992) reported mixed strychnine- and bicuculline-sensitive components of the Renshaw cell-mediated inhibition of spinal motoneurones and Jonas et al. (1998) have provided evidence for co-release by showing that unitary evoked and mIPSCs in spinal motoneurones are mediated by both GABA and glycine receptors. Similar observations have also been made in brainstem motoneurones (O’Brien & Berger, 1999). The GABAergic component accounted for around 15% of the IPSC amplitude in both these studies, where most of the animals used were less than a week old. In this study on the MSO, the GABAA receptor-mediated current was too small to detect (without benzodiazepines) in animals over 7 days old, but when the experiments were repeated in slices from 3- to 5-day-old rats we could observe GABAA receptor-mediated responses.

GABAA receptor utilisation declines at MSO synapses during maturation, with the decline coinciding with maturation of the projection to the superior olivary complex from the cochlear nucleus (Kandler & Friauf, 1993) at around 1 week of age. A developmental transition from GABAA-dominated to glycine-dominated transmission has been previously observed in the medial limb of gerbil LSO (Kotak et al. 1998). It is unclear from our data whether this change represents a reduction in the release of GABA or a reduction in the number of postsynaptic GABAA receptors. One interesting possibility is that GABA release remains significant, but that its principal target shifts from GABAA to GABAB receptors. Considering the lack of a known metabotropic glycine receptor, GABA could function in this role at glycinergic pathways via the GABAB receptor as observed recently in the spinal cord (Grudt & Henderson, 1998) and cochlear nucleus (Lim et al. 2000).

Miniature IPSCs

The mIPSCs observed here and elsewhere in spinal cord and auditory pathways show a fast decay time constant of around 5 ms and a slower decay time constant of around 20 ms (Takahashi et al. 1992; Legendre, 1997; Lim et al. 1999). The slower time course of the evoked IPSC compared to mIPSCs is likely to be due to asynchronous release of transmitter as characterised for excitatory synapses elsewhere (Issacson & Walmsley, 1995; Diamond & Jahr, 1995). Most of the evoked responses studied here were generated by stimulation of multiple axons, further exaggerating asynchronous release. The amplitude and coefficient of variance of mIPSCs were similar to those reported in brainstem motoneurones (Singer & Berger, 1999). Like GABAA receptor-mediated synapses (Edwards et al. 1990) the mean amplitude and variation in these glycinergic mIPSC amplitudes is large, suggesting that mIPSCs are multi-quantal. However, convincing evidence of co-operative release in the presence of TTX and in low external calcium is absent, although mechanisms involving calcium release from intracellular stores are a possibility. Most evidence points to the variations in mIPSC amplitude being due to differences in transmitter release (Frerking et al. 1995) and/or a large range in quantal size at glycinergic mIPSCs, which has been directly related to glycine receptor clustering (Lim et al. 1999).

IPSC voltage and temperature dependence

The slowing of the IPSC decay time constant with depolarisation seems to be a general property of glycine receptors. In the cat spinal cord 1a reciprocal interneurone (Stuart & Redman, 1990) and zebrafish hindbrain (Legendre, 1999), glycine receptors show a similar voltage dependence with an e-fold change in the decay time constant on depolarisation by around 95 mV. The time course of spinal IPSCs measured in young rats (Takahashi et al. 1992; Jonas et al. 1998), with mean fast time constants of around 16 ms (22-25°C), is slower than that of the glycinergic IPSCs observed here (decay τ = 8 ms, 25°C). From the measured temperature dependence (Q10 = 2.1), the data from our oldest animals (14 days) would give a fast decay with a time constant of around 1.5 ms at physiological temperatures, close to that reported by Stuart & Redman (1990) from adult cat.

The binaural auditory pathway

The binaural auditory pathway is adapted for rapid high-fidelity processing of timing information (Trussell, 1997). For example, the primary afferent (endbulb of Held) and secondary excitatory synapses (calyx of Held) are giant synapses which generate large EPSCs and utilise glutamate receptors with rapid kinetics (Raman et al. 1994; Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1995; Isaacson & Walmsley, 1995). In addition, specific low- and high-threshold potassium channels are expressed which encourage accurate transmission of the timing information across these brainstem relay synapses (Wang et al. 1998). These properties make important contributions to the physiological mechanism of sound localisation but as yet we have little appreciation of how the properties of MSO neurones might contribute to their role in sound localisation.

The MSO receives synaptic inputs from four sites: excitatory projections from ipsilateral and contralateral spherical bushy cells of the aVCN, and inhibitory inputs from the ipsilateral MNTB and lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB) (Cant & Hyson, 1992; Kuwabara & Zook, 1992). Given the location of the LNTB (lateral to the LSO, see Fig. 1A) it is unlikely that our stimulation site would have excited this nucleus. The MSO gives an excitatory ipsilateral projection to the inferior colliculus and dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (Henkel & Spangler, 1983). Examination of synaptic inputs to the MSO in gerbil (Grothe & Sanes, 1993, 1994) and rat (Smith, 1995) shows that binaural EPSPs are subject to integration with inhibitory inputs. This inhibition is blocked by strychnine, suggesting that the IPSC is mediated by glycine receptors, as has been observed in the LSO, which also receives a projection from the ipsilateral MNTB (Moore & Caspary, 1983; Wu & Kelly, 1991). Our data confirm the presence of the inhibitory response in the MSO and demonstrate that it is predominantly mediated by glycine receptors.

The MSO is considered the site of coincidence detection in binaural timing discrimination (Jeffress, 1948; Joris et al. 1998). Extracellular single units in the cat respond to sound with a characteristic frequency of under 3 kHz (Yin & Chan, 1990) and show a primary-like firing pattern (i.e. it follows the firing pattern of primary afferent fibres). In the rat (Brew & Forsythe, 1996) MSO neurones have a longer latency and higher threshold for action potential generation than MNTB neurones (-27 versus -39 mV, respectively). In the Jeffress model (1948; Joris et al. 1998) a coincidence detector combines with an afferent input delay line to convert interaural timing differences into a spatial location for a sound source. Anatomical and functional confirmation of this mechanism has been elegantly demonstrated in the barn owl, where ITDs of as little as 10 μs can be detected (Carr & Konishi, 1990; Konishi, 1993; Carr, 1993). There is evidence for a spatial map of ITDs running in the rostrocaudal axis of the mammalian MSO (rostral having shorter ITDs), and there is also evidence for a delay line in the contralateral inputs of the spherical bushy cells to the MSO (Yin & Chan, 1990; Smith et al. 1993; Beckius et al. 1999), which is compatible with a Jeffress-like model. Although the simplest idea of a delay line/coincidence model requires only excitatory inputs, there is increasing evidence that blockade of inhibition reduces timing discrimination (Grothe & Sanes, 1994) and that such inhibition plays an important role in sharpening ITDs (Grothe & Park, 1998). Although the utilisation of GABAA receptors in the avian auditory pathway (Carr & Boudreau, 1993) contrasts with the predominantly glycinergic IPSCs observed in the mammalian SOC, its function in regulating neuronal excitability is likely to be similar. The inhibitory input could function to refine coincidence detection and influence the coding of binaural timing differences by increasing the somatic shunt during coincidence detection (Funabiki et al. 1998; Yang et al. 1999) and may also underlie binaural and monaural precedence effects (Litovsky & Yin, 1998) which suppress responses to echoes, thereby increasing the accuracy of sound source localisation in reflective environments.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Margaret Barnes-Davies, Brian Billups and Adrian Wong for critical reading of the manuscript and to D. Langosch for the gift of cyanotriphenylborate. A.J.S. was a Wellcome PhD Prize Student and S.O. has an MRC PhD Scholarship. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

A. J. Smith and S. Owens contributed equally to this work.

References

- Adams JC, Mugnaini E. Immunocytochemical evidence for inhibitory and disinhibitory circuits in the superior olive. Hearing Research. 1990;49:281–298. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Davies M, Forsythe ID. Pre- and postsynaptic glutamate receptors at a giant excitatory synapse in rat auditory brainstem slices. Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:387–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Davies M, Forsythe ID. AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic currents rectify with internal spermine in rat MNTB neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1996;495.P:44. P. [Google Scholar]

- Becker C-M, Hoch W, Betz H. Glycine receptor heterogeneity in rat spinal cord during postnatal development. EMBO Journal. 1988;7:3717–3726. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckius GE, Batra R, Oliver DL. Axons from anteroventral cochlear nucleus that terminate in medial superior olive of cat: Observations related to delay lines. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:3146–3161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03146.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz H. Structure and function of inhibitory glycine receptors. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 1992;25:381–394. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe SCJ, Snead CR, Helfert RH, Prasad V, Wenthold RJ, Altschuler RA. Immunocytochemical and lesion studies support the hypothesis that the projection from the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body to the lateral superior olive is glycinergic. Brain Research. 1990;517:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91025-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Hamill OP, Sakmann B. Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and GABA in mouse cultured spinal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1987;385:243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Rundstrom N, Betz H, Langosch D. Residues within transmembrane segment M2 determine chloride conductance of glycine receptor homo- and hetero-oligomers. EMBO Journal. 1993;12:3729–3737. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D, Mayer ML. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron. 1995;15:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew HM, Forsythe ID. Neurones in two auditory nuclei of rat brainstem exhibit distinct electrophysiological properties. Journal of Physiology. 1996;495.P:57. P. [Google Scholar]

- Brunso-Bechtold JK, Henkel CK, Linville C. Synaptic organization in the adult ferret medial superior olive. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;294:389–398. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB, Hyson RL. Projections from the lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body to the medial superior olivary nucleus in the gerbil. Hearing Research. 1992;58:26–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CE. Processing of temporal information in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1993;16:223–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CE, Boudreau RE. Organization of the nucleus magnocellularis and the nucleus laminaris in the barn owl: Encoding and measuring interaural time differences. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;334:337–355. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CE, Konishi M. A circuit for detection of interaural time differences in the brain stem of the barn owl. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:3227–3246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-10-03227.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GM. The ultrastructure of nerve endings in the medial superior olive of the cat. Brain Research. 1969;14:293–305. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(69)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs JS, Eccles JC, Fatt P. The specific ionic conductance and the ionic movements across the motoneuronal membrane that produce the inhibitory postsynaptic potential. Journal of Physiology. 1955;130:326–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Asynchronous release of synaptic vesicles determines the time course of the AMPA receptor-mediated EPSC. Neuron. 1995;15:1097–1107. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B. Quantal analysis of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampal slices: a patch-clamp study. Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:213–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Lohrke S, Friauf E. Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action in rat auditory neurones is due to age-dependent Cl− regulation. Journal of Physiology. 1999;520:121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Westbrook GL. Slow excitatory postsynaptic currents mediated by activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors on cultured mouse central neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1988;396:515–534. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerking M, Borges S, Wilson M. Variation in GABA mini amplitude is the consequence of variation in transmitter concentration. Neuron. 1995;15:885–895. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friauf E, Hammerschmidt B, Kirsch J. Development of adult-type inhibitory glycine receptors in the central auditory system of rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;385:117–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970818)385:1<117::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki K, Koyano K, Ohmori H. The role of GABAergic inputs for coincidence detection in the neurones of nucleus laminaris of the chick. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:851–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.851bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geal-Dor M, Freeman S, Li G, Sohmer H. Development of hearing in neonatal rats: Air and bone conducted ABR thresholds. Hearing Research. 1993;69:236–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90113-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JRP, Melcher T, Koh DS, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH, Jonas P, Monyer H. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron. 1995;15:193–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JM, Brown PB. Responses of binaural neurones of the dog superior olivary complex to dicotic tonal stimuli: some physiological mechanisms of sound localisation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1969;32:613–636. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenningloh G, Rienitz F, Schmitt B, Methfessel C, Zensen M, Beyreuther K, Gundelfinger ED, Betz H. The strychnine-binding subunit of the glycine receptor shows homology with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nature. 1987;328:215–220. doi: 10.1038/328215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B, Park TJ. Sensitivity to interaural time differences in the medial superior olive of a small mammal, the Mexican free-tailed bat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:6608–6622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06608.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B, Sanes DH. Bilateral inhibition by glycinergic afferents in the medial superior olive. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:1192–1196. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B, Sanes DH. Synaptic inhibition influences the temporal coding properties of medial superior olivary neurons: an in vitro study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:1701–1709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01701.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Henderson G. Glycine and GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in rat substantia gelatinosa: inhibition by μ-opiod and GABAB agonists. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:473–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.473bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JM, Irving R. Visual and nonvisual auditory systems in mammals. Science. 1966;154:738–743. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3750.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel CK, Spangler KM. Organization of the efferent projections of the medial superior olivary nucleus in the cat as revealed by HRP and autoradiographic tracing methods. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1983;221:416–428. doi: 10.1002/cne.902210405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Amplitude and time course of spontaneous and evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents in bushy cells of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:1566–1571. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffress LA. A place theory of sound localisation. Journal of Comparative Physiology and Psychology. 1948;41:35–39. doi: 10.1037/h0061495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Sandkuhler J. Corelease of two fast neurotransmitters at a central synapse. Science. 1998;281:419–424. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Smith PH, Yin TCT. Coincidence detection in the auditory system: 50 years after Jeffress. Neuron. 1998;21:1235–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80643-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj SK, Swanson GT, Cull-Candy SG. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:297–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E. Pre and postnatal development of efferent connections of the cochlear nucleus in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;328:161–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E. Development of glycinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the auditory brainstem of perinatal rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6890–6904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06890.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh D-S, Burnashev N, Jonas P. Block of native Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in rat brain by intracellular polyamines generates double rectification. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:305–312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolston J, Osen KK, Hackney CM, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. An atlas of glycine- and GABA-like immunoreactivity and colocalization in the cochlear nuclear complex of the guinea pig. Anatomy and Embryology. 1992;186:443–465. doi: 10.1007/BF00185459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M. Listening with two ears. Scientific American. 1993;268:66–73. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0493-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak VC, Korada S, Schwartz IR, Sanes DH. A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:4646–4655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kungel M, Friauf E. Physiology and pharmacology of native glycine receptors in developing rat auditory brainstem neurons. Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research. 1997;102:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara N, Zook JM. Projections to the medial superior olive from the medial and lateral nuclei of the trapezoid body in rodents and bats. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;324:522–538. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langosch D, Becker CM, Betz H. The inhibitory glycine receptor: A ligand-gated chloride channel of the central nervous system. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1990;194:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. Pharmacological evidence for two types of postsynaptic glycinergic receptors on the Mauthner cell of 52-h-old zebrafish larvae. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:2400–2415. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. Voltage-dependence of the glycine receptor-channel kinetics in zebrafish hindbrain. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:2120–2129. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim R, Alvarez FJ, Walmsley B. Quantal size is correlated with receptor cluster area at glycinergic synapses in the rat brainstem. Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0505v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim R, Alvarez FJ, Walmsley B. GABA mediates presynaptic inhibition at glycinergic synapses in a rat auditory brainstem nucleus. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey BG. Fine structure and distribution of axon terminals from the cochlear nucleus on neurons in the medial superior olivary nucleus of the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1975;160:81–103. doi: 10.1002/cne.901600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Yin TCT. Physiological studies of the precedence effect in the inferior colliculus of the cat. II. Neural mechanisms. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:1302–1316. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Rajendra S, Barry PH, Schofield PR. Mutations affecting the glycine receptor agonist transduction mechanism convert the competitive antagonist, picrotoxin, into an allosteric potentiator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:13799–13806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain C, Dingledine R. Dual-component miniature excitatory synaptic currents in rat hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:16–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor JR, Randall AD. Frequency-dependent actions of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors in cultured murine cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:353–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.353bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Caspary DM. Strychnine blocks binaural inhibition in lateral superior olivary neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1983;3:237–242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00237.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbacher J, Schoepfer R, Monyer H, Burnashev N, Seeburg PH, Ruppersberg JP. A molecular determinant for sub-millisecond desensitization in glutamate receptors. Science. 1994;266:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.7973663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JA, Berger AJ. Co-transmission of GABA and glycine to brainstem motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:1638–1641. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce RA. Physiological evidence for two distinct GABAA responses in rat hippocampus. Neuron. 1993;10:189–200. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90310-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer F, Graham D, Betz H. Purification by affinity chromatography of the glycine receptor of rat spinal cord. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257:9389–9393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribilla I, Takagi T, Langosch D, Bormann J, Betz H. The atypical M2 segment of the beta subunit confers picrotoxinin resistance to inhibitory glycine receptor channels. EMBO Journal. 1992;11:4305–4311. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Zhang S, Trussell LO. Pathway-specific variants of AMPA receptors and their contribution to neuronal signalling. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:4998–5010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04998.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranathan A, Donean SD, Sugden SG, Greig A, Rao MS, Parks TN. Contrasting molecular composition and channel properties of AMPA receptors on chick auditory and brainstem motor neurons. Journal of Physiology. 2000;523:667–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayleigh OM. On our perception of sound direction. Philosophical Magazine. 1907;13:214–232. [Google Scholar]

- Rundstrom N, Schmieden V, Betz H, Bormann J, Langosch D. Cyanotriphenylborate: Subtype-specific blocker of glycine receptor chloride channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:8950–8954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SP, Fyffe REW. Involvement of GABA and glycine in recurrent inhibition of spinal motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:397–406. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PR, Darlison MG, Fujita N, Burt DR, Stephenson FA, Rodriguez H, Rhee LM, Ramachandran J, Reale V, Glencorse TA, Seeburg PH, Barnard EA. Sequence and functional expression of the GABA(A) receptor shows a ligand-gated receptor super-family. Nature. 1987;328:221–227. doi: 10.1038/328221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JH, Berger AJ. Contribution of single-channel properties to the time course and amplitude variance of quantal glycine currents recorded in rat motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81:1608–1616. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JH, Talley EM, Bayliss DA, Berger AJ. Development of glycinergic synaptic transmission to rat brain stem motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:2608–2620. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Forsythe ID. Glycinergic synaptic responses between identified neurones in the rat auditory pathway. Journal of Physiology. 1996;495.P:56. P. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH. Structural and functional differences distinguish principal from non-principal cells in the guinea pig MSO slice. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:1653–1667. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Joris PX, Yin TCT. Projections of physiologically characterized spherical bushy cell axons from the cochlear nucleus of the cat: Evidence for delay lines to the medial superior olive. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;331:245–260. doi: 10.1002/cne.903310208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler KM, Warr WB, Henkel CK. The projections of the principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1985;238:249–262. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern P, Edwards FA, Sakmann B. Fast and slow components of unitary EPSCs on stellate cells elicited by focal stimulation in slices of rat visual cortex. Journal of Physiology. 1992;449:247–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotler WA. An experimental study of the cells and connections of the superior olivary complex of the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1953;98:401–431. doi: 10.1002/cne.900980303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Redman SJ. Voltage dependence of Ia reciprocal inhibitory currents in cat spinal motoneurones. Journal of Physiology. 1990;420:111–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Momiyama A, Hirai K, Hishinuma F, Akagi H. Functional correlation of fetal and adult forms of glycine receptors with developmental changes in inhibitory synaptic receptor channels. Neuron. 1992;9:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90073-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell LO. Cellular mechanisms for preservation of timing in central auditory pathways. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1997;7:487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchitani C, Johnson DH. Binaural cues and signal processing in the superior olivary complex. In: Altschuler RA, Bobbin RP, Clopton BM, Hoffman DW, editors. Neurobiology of Hearing: The Central Auditory System. New York: Raven Press Ltd; 1991. pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Twyman RE, MacDonald RL. Kinetic properties of the glycine receptor main and sub-conductance states of mouse spinal cord neurones in culture. Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:303–331. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vater M. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical observations on the superior olivary complex of the mustached bat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;358:155–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.903580202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-Y, Gan L, Forsythe ID, Kaczmarek LK. Functional contribution of a Shaw-like high-threshold potassium channel (Kv3. 1) to the phase-locking capability of neurones in mouse auditory brainstem. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.183bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SH, Kelly JB. Physiological properties of neurons in the mouse superior olive: Membrane characteristics and postsynaptic responses studied in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;65:230–246. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Monsivais P, Rubel EW. The superior olivary nucleus and its influence on nucleus laminaris: A source of inhibitory feedback for coincidence detection in the avian auditory brainstem. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2313–2325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02313.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin TCT, Chan JCK. Interaural time sensitivity in medial superior olive of cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;64:465–488. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]