Abstract

Hydroethidine (HE) is a cell-permeable probe used for the intracellular detection of superoxide. Here we report the direct measurement of the rate constant between hydroethidine and superoxide radical anion using the pulse radiolysis technique. This reaction rate constant was calculated to be ca. 2·106 M-1s-1 in water:ethanol (1:1) mixture. The spectral characteristics of the intermediates indicated that the one-electron oxidation product of HE was different from the one-electron reduction product of ethidium (E+). The HPLC-electrochemical measurements of incubation mixtures containing HE and the oxygenated Fenton’s reagent (Fe2+/DTPA/H2O2) in the presence of aliphatic alcohols or formate as a superoxide generating system revealed 2-OH-E+ as a major product. Formation of 2-OH-E+ by the Fenton’s reagent without additives was shown to be superoxide dismutase-sensitive and we attribute the formation of superoxide radical anion to the one-electron reduction of oxygen by the DTPA-derived radical. Addition of tert-butanol, DMSO, and potassium bromide to the Fenton’s system caused inhibition of 2-OH-E+ formation. Results indicate that reducing and oxidizing radicals have differential effects on the formation of 2-OH-E+.

Introduction

The intracellular reaction between hydroethidine (HE, also known as dihydroethidium, DHE, Figure 1) and superoxide anion (O2·-) results in the generation of a characteristic product, 2-hydroxyethidium cation (2-OH-E+, Figure 1) [1-8].1 For decades, this product was believed to be the ethidium cation (E+, Figure 1) [3-6]. Using a competition kinetics based on spin-trapping, we previously estimated the rate constant for the reaction between HE and O2·- as ∼105 M-1s-1 [7]. A major advantage of using HE as a probe for detecting intracellular O2·- is that the product, 2-OH-E+, is highly specific for O2·-, as other biologically-relevant oxidants do not react with HE to form this particular product [7-9]. Unlike other assays such as the lucigenin chemiluminescence or hydroxylamines oxidation to nitroxides, which are fraught with artifacts, the O2·--dependent hydroxylation of HE to 2-OH-E+ is very specific. Because O2·- formation is invariably associated with generation of other oxidants (hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite, etc.), it is essential to acquire as much mechanistic information as possible on the oxidation/reduction reactions of HE.

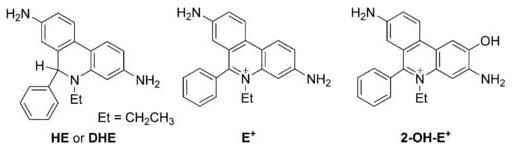

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of hydroethidine (HE), ethidium (E+) and 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+).

In the present study, we used both time-resolved (pulse radiolysis) and steady-state (using a Fenton system) analyses of the reaction of HE with O2·-. Results show that O2·- reacts fairly rapidly with HE and that O2·- generated from hydroxyl radicals (·OH) reacts with HE to form the characteristic product, 2-OH-E+. We have also demonstrated that the one-electron oxidation species formed from the reaction between O2·- and HE is structurally very different from the one-electron reduction of ethidium.

Materials and Methods

Materials

HE (dihydroethidium) and E+ (ethidium bromide) were from Molecular Probes. Sodium azide was obtained from Fisher Scientific. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) isolated from bovine erythrocytes was purchased from Roche Diagnostics Corporation. Catalase (beef liver) was from Boehringer Mannheim GmbH. Hydrogen Peroxide (30% in water, not stabilized) was from Fluka. Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich and were of the highest purity available. 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+) was independently synthesized according to the published procedure [10]. Ethyl alcohol (EtOH) was obtained from Aaper Alcohol and Chemical Co. The spin trap 5-tert-butoxycarbonyl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (BMPO) was synthesized as described previously [11].

Preparation of stock solutions

Stock solutions of HE (5 mM) were prepared by dissolving in cold aqueous solution of HClO4 (0.1 M) and stored on ice, protected from room light. DMSO was not used as it reacts with the hydroxyl radical. The concentration of HE was determined at pH 7.4, after 100 × dilution using the extinction coefficients 1.8 × 104 and 9.75 × 103 M-1cm-1 at 265 and 345 nm, respectively [10]. 2-OH-E+ and E+ solutions were prepared in 1 mM HCl and stored at 4 °C. 2-OH-E+ and E+ concentrations were determined at pH 7.4, using the extinction coefficients 1.2 × 104 (470 nm) and 5.8 × 103 M-1cm-1 (480 nm), for 2-OH-E+ and E+, respectively [10,12]. The concentration of H2O2 solution (∼10 mM in water) was determined by measuring the absorbance at 240 nm using the extinction coefficient 39.4 M-1cm-1 [13]. FeSO4 stock solution (10 mM) was prepared by dissolving in cold 1 mM HClO4 and was diluted 100-fold in 1 mM HClO4 to prepare a 100 μM working solution and stored at 4 °C before use. Water for the solution preparation was purified by Milli-Q system (Millipore Corp.) and passed through a Prevail C18 SPE cartridge (Alltech) to remove traces of organic contaminants.

Determination of 2-hydroxyethidium by HPLC with electrochemical detection (HPLC-EC)

2-Hydroxyethidium concentration was measured by HPLC with electrochemical detection (ESA CoulArray® detector) as described previously [12] with minor modifications. To obtain a better separation between 2-OH-E+ and E+, an ether-linked phenyl column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 4 μm, Synergi Polar-RP®, Phenomenex) was used instead of a C18 column. The elution method was used with two mobile phases: A. 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.6), 10% acetonitrile, 90 % water; B. 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.6), 60% acetonitrile, 40 % water. HE, 2-OH-E+ and E+ were separated using a gradient elution with ratios of the A and B mobile phases changing from 3:2 to a pure B phase over a time period of 30 min, using a flow rate 0.5 ml/min. The potentials of the detector channels were set to 0, 150, 280, 365, 400, 450, 500 and 600 mV versus the palladium reference electrode.

HPLC with fluorescence detection (HPLC-Fl)

HPLC-Fl experiments were performed using an Agilent 1100 system equipped with UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence detectors as described previously [10]. The compounds were separated on a C18 column (Kromasil 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Alltech).

Pulse radiolysis

Pulse radiolysis experiments were carried out at the Brookhaven National Laboratory using a 2 MeV electron Van de Graaff accelerator. The radiolysis of neutral water leads to the formation of three highly reactive species: eaq- (2.6), ·OH (2.7) and H· (0.6) in addition to the formation of less reactive products, H2O2 (0.7), H2 (0.45) and H3O+ (2.6) (numbers in parentheses are the radiation yield values defined as the number of the species formed per 100 eV energy absorbed) [14]. The dose absorbed per pulse was measured on the basis of the initial yield of (SCN)2·- formed in the N2O-saturated 0.01 M KSCN aqueous solution assuming a radiation yield 6.13 and an extinction coefficient of 7580 M-1cm-1 at 472 nm [15].

To investigate the reaction between HE and ·OH radicals, eaq- was converted into ·OH by saturating the solution with N2O (reaction 1, k1 = 9.1 × 109 M-1s-1 [14]):

| (1) |

For the reaction of HE with Br2·-, pulse radiolysis was carried out in the presence of KBr (0.1 M), so that the bromide anions reacted with ·OH to from Br2·- via reactions 2 and 3 (k2 = 1.1 × 1010 M-1s-1, k3 = 1.2 × 1010 M-1s-1 [16]):

| (2) |

| (3) |

To investigate the reaction between HE and O2·-, we used an O2-saturated EtOH:water (1:1 by volume) mixture in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 μM EDTA. This system was chosen to increase HE concentration, thereby increasing the rate of the reaction of HE and O2·-. In this system the products of EtOH radiolysis, including hydroxyethyl radicals, were also formed along with the water radiolysis products. Moreover, the hydroxyl radicals react quickly with EtOH to yield an additional EtOH-derived radicals (reaction 4, k4 = 1.9 × 109 M-1s-1 [14]).

| (4) |

The solvated electrons (es-) react quickly with O2 to form the superoxide radical anion (reaction 5, k5 = 1.9 × 1010 M-1s-1 [14]):

| (5) |

Hydroxyethyl radicals also react with O2 to form the α-hydroxyethylperoxyl radical (reaction 6, k6 = 4.6 × 109 M-1s-1 [17]):

| (6) |

The peroxyl radical formed can react with HE or eliminate O2·- spontaneously (reaction 7, k7 = 50 s-1 [18]) or undergo base-catalyzed reactions (reactions 8 and 9, k8 = 4 × 109 M-1s-1, k9 = 4 × 106 M-1s-1 [18]).

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Given the pH of the solution (pH = 8) and phosphate buffer concentration (10 mM), it can be assumed that under these conditions reaction 9 is the predominant decomposition pathway of the α-hydroxyethylperoxyl radicals.

For one-electron reduction of E+ we used the carbon dioxide radical anion (CO2·-) that was formed in a N2O-saturated aqueous solution of HCOONa (0.05 M) via reactions 1, 10 and 11 (k10 = 3.2 × 109 M-1s-1, k11 = 2.1 × 108 M-1s-1 [14]):

| (10) |

| (11) |

EPR measurements

EPR spectra were recorded at room temperature using the Bruker EMX spectrometer operating at 9.85 GHz and equipped with a Bruker ER 4119HS-WI high sensitivity resonator. Typical spectrometer parameters were: scan range 100 G, time constant 1.28 ms, sweep time 5.24 s, modulation amplitude 1.0 G, modulation frequency 100 kHz, microwave power: 5.0 mW. Micropipettes (100 μl) were used as sample tubes.

Fenton’s system

The reaction of HE with the Fenton reagent was studied in a system containing 50 μM HE, 10 μM FeSO4, 1.0 mM H2O2, 100 μM DTPA (unless otherwise stated) and 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with or without other additives. The mixtures without HE and FeSO4 (0.89 ml) were bubbled with O2 or argon for ca. 15 min at ambient temperature in amber glass vials and the reaction was started by adding HE (10 μl) followed by FeSO4 (100 μl). The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min with continuous O2 or argon bubbling. For HPLC-Fl measurements, the reaction mixture was diluted 1:1 with a cold aqueous solution containing 100 mM phosphate pH 2.6 and 200 μM DTPA and immediately injected for analysis. For HPLC-EC analysis, typically 30 samples were obtained from each experiment and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μl of a mixture of catalase (CAT, 10 kU/ml) and SOD (100 μg/ml) and 100 μl of t-BuOH (10 % v/v aqueous solution). The reaction mixture was then placed in a refrigerator (4 °C) and after 1 hr 190 μl of the mixture was transferred to black tubes and mixed with 10 μl of 70% aqueous solution of HClO4 to precipitate the proteins. Solutions were then stored at -80 °C overnight. On the next day the samples were placed on ice for 2-3 hrs and centrifuged (30 min, 20,000 g, 4 °C). The supernatant (50 μl) was mixed with 450 μl of a cold aqueous solution containing 100 mM phosphate pH 2.6 and 200 μM DTPA. Solutions were than placed in a thermostatted autosampler (6 °C) and stored until HPLC-EC analysis.

Analysis of the kinetic data

The rate constant values were obtained using the Pro-Kineticist II program version 1.9 (Applied Photophysics Ltd), which enables fitting of the reaction mechanism to the measured data using numerical integration. As the program simultaneously analyzes data obtained at different wavelengths, it enables the simulation of the spectra of the reaction intermediates.

Results

One-electron oxidation of HE

The one-electron oxidation product of HE was generated by reaction with dibromide radical anion (Br2·-) formed by pulse radiolysis. Br2·- is a strong one-electron oxidant that reacts with most organic compounds via an electron-transfer mechanism. Several reports indicate that Br2·- reacts rapidly with different dihydropyridines, including NADH and the primary oxidation products formed during these reactions have been previously characterized [19, 20]. Thus, we decided to investigate the one-electron oxidation product formed from the reaction between HE and Br2·- (Fig. 2). The transient species formed during the reaction was characterized by the two absorption bands (λmax = 455 and 700 nm) with extinction coefficients of 2.3 × 104 M-1cm-1 and 1.2 × 104 M-1cm-1, respectively, as measured from the absorbance changes assuming the radiation yield of Br2·- radical anion to be 6.0. The rate constant of the reaction ((2.1±0.3) × 109 M-1s-1) was calculated on the basis of the rate of Br2·- decay (λobs = 360 nm) as well as the build-up of the product (λobs = 460 nm and 700 nm) in a solution containing 0.1 mM HE.

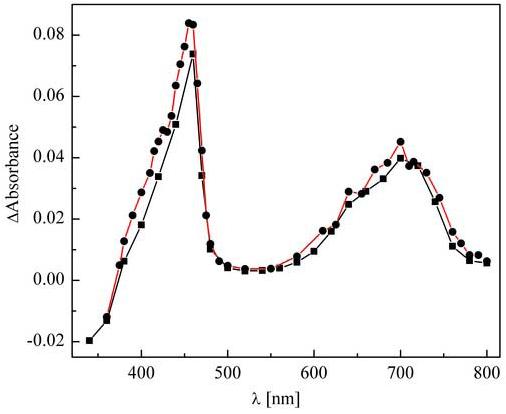

Figure 2.

Transient absorption spectra obtained by pulse radiolysis of HE (0.1 mM) in N2O-saturated aqueous solution containing 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, with (●) and without (■) 0.1 M KBr. The spectra were collected 30 μs after the electron pulse and were normalized to a radiation dose 3 Gy. The optical pathlength was 2.0 cm.

As ·OH is one of the most powerful oxidants formed in biological systems, we investigated its reactivity towards HE. As can be seen in Figure 2, despite the fact that ·OH is a non-selective reactive species known to react with aromatic compounds by electron transfer, hydrogen abstraction and/or addition to a double bond, the spectrum observed 10 μs after the electron pulse resembles the spectrum of the one-electron oxidation product formed during the reaction of HE with Br2·-. Indeed both wavelengths of the absorption bands maxima (460 and 700 nm) and extinction coefficients (2.1 × 104 M-1cm-1 and 1.1 × 104 M-1cm-1, respectively) were nearly identical within the experimental error (∼10%), as measured for the product of the reaction of HE with Br2·-. Therefore, we can conclude that even if the initial adducts of HE with ·OH radical are formed, they undergo water (or -OH) elimination with the formation of a one-electron oxidation product. As ·OH radical does not exhibit any absorption band in the wavelength range analyzed, the rate constant of the reaction was measured only on the basis of product build-up kinetics, resulting in a value of (7±1)·109 M-1s-1.

Reaction of HE with superoxide radical anion

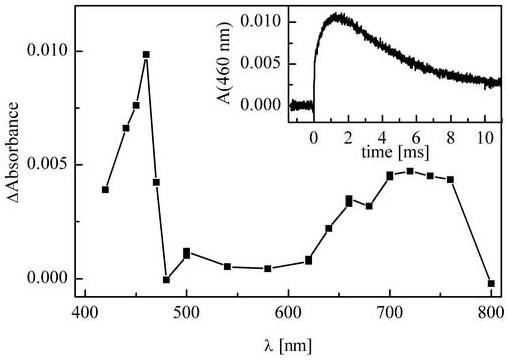

The reactivity of superoxide radical anion with HE was investigated using the pulse radiolysis of an aqueous-ethanolic (50:50, volume:volume) solution of HE in phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 8). Ethanol was added to increase the solubility of HE, thereby increasing the concentration of the intermediate. As described in the Materials and Methods section O2·- was formed as the main reactive species as a result of solvated electron scavenging by oxygen (reaction 5) and by the decomposition of the α-hydroxyethylperoxyl radical (reactions 7-9). Additional evidence for the formation of superoxide was obtained by monitoring the changes of the absorbance at 250 nm following the pulse radiolysis of an analogous solution without HE. The transient spectrum obtained from the reaction of HE with superoxide radical anion together with the kinetic trace recorded at 460 nm are shown in Figure 3. This spectrum (Fig. 3) resembles the spectrum of the one-electron oxidation product of HE (Fig. 2) with respect to the position of the absorption bands as well as their intensity ratios. It can be therefore assumed that the one-electron oxidation product is formed during the reaction between HE and O2·-. The only difference between the spectra shown in Figures 2 and 3 is the much lower band intensities in the spectrum obtained by reacting HE with O2·-. As the superoxide dismutation rate under the conditions used should be relatively slow (half lifetime > 100 ms), the observed low concentration of the radical can be explained by the interference of the decay of the primary product with its formation.2 In fact, the kinetic trace presented in Figure 3 shows that the decay of the intermediate takes place on the same timescale as its formation. As the nature of the decay process(es) is not known, the kinetic modeling and fitting gives only an estimate of the rate constant and the best fit was obtained using a rate constant of 2·106 M-1s-1 for the reaction of HE with O2·-. However the rate constant values within the range (0.5 - 4)·106 M-1s-1 also yielded good fit to the experimental data.

Figure 3.

Transient absorption spectrum obtained on pulse radiolysis of O2-saturated water-ethanol (50/50 vol.) solution of HE (0.3 mM) containing 10 μM EDTA and 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8). Dose: 5 Gy, optical pathlength: 2.0 cm. The spectrum collected 1.1 ms after the electron pulse. Inset: kinetic trace recorded at 460 nm.

One-electron reduction of ethidium cation

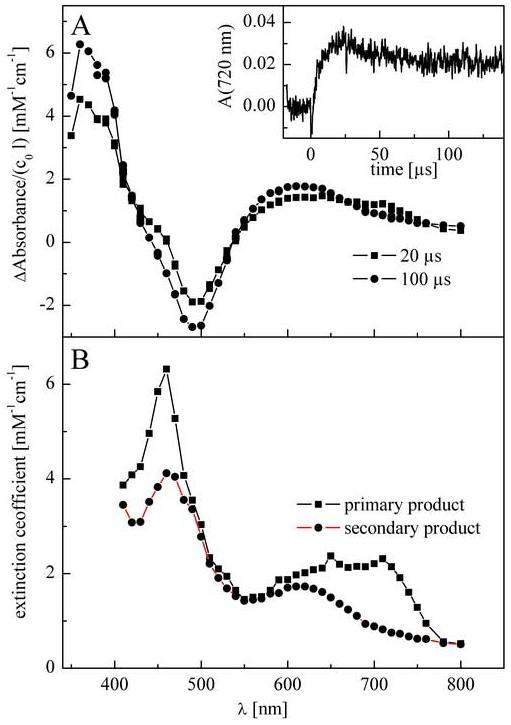

To obtain additional structural information concerning the oxidation product formed during the one-electron oxidation of HE, we decided to compare its spectrum to the spectrum obtained from the one-electron reduction of the ethidium cation. HE is formed from the two-electron reduction of E+. Despite the fact that the kinetics of one-electron reduction of E+ by eaq has been used in pulse radiolysis studies of the interaction of E+ with polyanions [22], the spectrum of the reduction product has not yet been characterized. Thus, we performed the pulse radiolysis of the E+ solution using CO2·- as a one-electron reducing agent. The transient spectra collected at 20 and 100 μs after the electron pulse together with the kinetic trace recorded at 720 nm are presented in Figure 4A. It is evident that the primary product formed during the reduction of E+ is not stable and changes to another product during the first 100 μs. Although the initial spectrum recorded after the one-electron reduction of E+ is different from that of the one-electron oxidation of HE, there could be ambiguity in distinguishing whether that is due to a different chemical structure of the intermediate formed in both processes, or due to the instability of the one-electron reduction product. Therefore we used ProKin II software that enables not only modeling and fitting the kinetics of the reaction, but also enables simulation of the absorption spectra of the transient products formed during the course of the reaction. The simulated spectra of the intermediates formed during the one-electron reduction of E+ (calculated on the basis of a model of two consecutive first order reactions) are presented in Figure 4B. As these spectra are different from the spectrum of the one-electron oxidized HE, we concluded that the one-electron reduction of E+ generates a different species compared to the one-electron oxidation of HE.

Figure 4.

(A) Transient absorption spectra obtained on pulse radiolysis of N2O-saturated aqueous solution of 0.1 mM E+Br- containing 50 mM HCOONa and 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Dose: 7 Gy. Inset: kinetic trace recorded at 720 nm. (B) The simulated spectra of the initial and subsequent products of the reaction between E+ and CO2·-.

Reaction of HE with the Fenton’s reagent

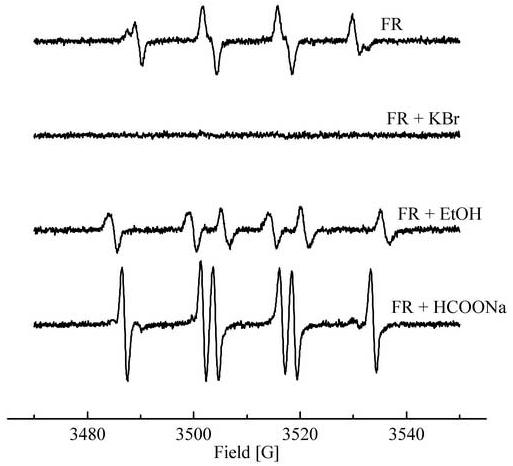

As the primary oxidation product of the HE/ O2·- reaction is the same as that formed in the reaction between HE and Br2·- or ·OH, we speculated whether the final products of the oxidation would also be the same. To this end, we used a Fenton’s reagent (FR) consisting of Fe2+/DTPA and H2O2 so as to mimic the steady-state radiolytic system [23,24]. Highly reactive oxidizing species or the Fenton-derived reactive species are formed in this system. Although the exact structure of these species in most systems still remains controversial, we propose that ·OH is formed as the primary oxidant under the present experimental conditions. This is based on our EPR spin-trapping results. Figure 5a shows the EPR spectrum of the spin adduct attributable to the BMPO-OH adduct formed from trapping of the hydroxyl radical by BMPO [11]. In the presence of KBr, no EPR signal was observed (Fig. 5b), suggesting that the bromide anion was able to inhibit the formation of BMPO-OH by scavenging the ·OH radicals. In the presence of EtOH, we detected the spin adduct BMPO-CH(OH)CH3 formed from trapping of the hydroxyethyl radical by BMPO (Fig. 5c). Addition of formate to the Fenton system generated the carbon dioxide radical adduct (Fig. 5d). These results are consistent with formation of ·OH - like species in the Fenton system used in this study.

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of BMPO spin adducts. Incubations consisted of the following: The Fenton’s reagent (100 μM FeSO4, 2.5 mM H2O2, 100 μM DTPA, 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4), BMPO (25 mM) and various hydroxyl radical scavengers. Spectra collected 3 min after mixing.

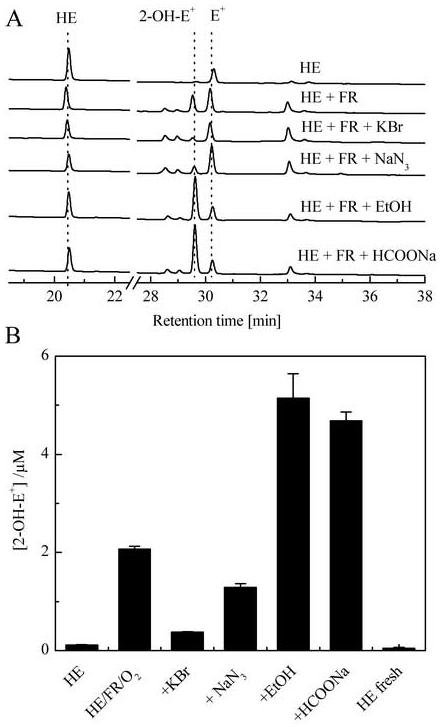

The HPLC analyses of the reaction products of HE with the Fenton’s reagent in oxygenated aqueous solution containing different ·OH radical scavengers are shown in Figure 6. The absorbance changes detected at 290 nm during the elution of the reaction mixtures are shown in Figure 6A. Major products detected in this system were 2-OH-E+ and E+, although there were other products whose structures have not yet been determined. In the presence of KBr or NaN3 that resulted in the formation of specific one-electron oxidants (Br2·- and N3·, respectively), the 2-OH-E+ levels decreased along with a concominant increase in the peak areas of other products. The decrease in 2-OH-E+ levels was also observed after the addition of DMSO, a widely used solvent for HE (data not shown). In contrast, addition of EtOH or HCOONa to the Fenton system caused a dramatic increase in 2-OH-E+ (Fig. 6). Similarly, the addition of other aliphatic alcohols including methanol, 2-propanol and n-butyl alcohol, but not t-BuOH, also enhanced 2-OH-E+ levels in the Fenton system. Based on these results, we conclude that most of these radical scavengers with the exception of tert- butyl alcohol were converted into reducing radical species that reacts with O2 to form O2·-.

Figure 6.

HPLC analysis of the reaction products. HE (50 μM) was mixed with the Fenton’s reagent (10 μM FeSO4, 1.0 mM H2O2, 100 μM DTPA, 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4). Incubation mixtures were bubbled for 30 min with O2 and where indicated, KBr (0.1 M), NaN3 (0.1 M), 1% (by vol.) EtOH or 0.1 M HCOONa was included. (A). HPLC absorption traces recorded at 290 nm. (B) 2-OH-E+ concentration as determined by HPLC-EC. Samples for HPLC analyses were processed as described in Materials and Methods.

Enhanced formation of O2·- in the presence of ethanol can be explained based on the reaction between the α-hydroxyethyl radical and oxygen that results in formation of O2·- (reactions 6-9). Analogous reaction pathways account for O2·- formation from other alcohol-derived α-hydroxyaliphatic radicals [25,26]. The inability of t-BuOH to stimulate 2-OH-E+ production by the Fenton’s reagent can be attributed to the “non-reducing” nature of the radical formed from the reaction between ·OH and t-BuOH [27]. With formate anion, the resulting carbon dioxide radical anion reacts very rapidly with oxygen by an electron transfer mechanism (reaction 12, k12 = 2.0·109 M-1s-1 [28]):

| (12) |

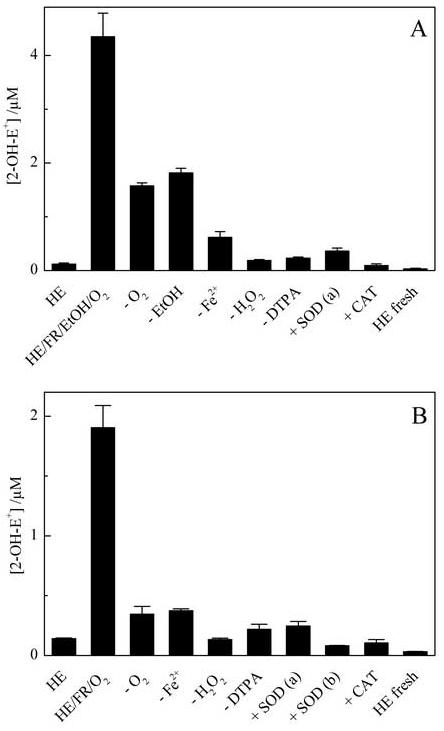

As ethanol was used in both pulse radiolysis and steady state measurements, we investigated the plausible mechanisms of O2·- formation by modifying several factors (e.g., oxygen, the Fenton’s reagent components, SOD and catalase) on 2-OH-E+ formation (Fig. 7A). Results suggest that 2-OH-E+ formation was maximal in incubations containing all of the Fenton’s reagent components in the presence of EtOH and O2. The residual formation of the 2-OH-E+ in the deoxygenated system may be due to inadequate removal of oxygen. Moreover, the 2-OH-E+ formation was inhibited by SOD. This suggests that 2-OH-E+ is derived from interaction of superoxide radical anion with HE. Thus, it can be concluded that the oxygenated Fenton’s system in the presence of EtOH mimics the radiolytic system used and can be used as a convenient way of non-enzymatic continuous generation of O2·-.

Figure 7.

The effect of oxygen, SOD, catalase and Fenton’s reagent components on 2-OH-E+ formed (A) in the presence of EtOH and (B) in the absence of EtOH. Where indicated, SOD (a - 1 μg/ml, b - 10 μg/ml) and catalase (CAT, 100 U/ml) were included in the Fenton system containing HE (50 μM) and DTPA (100 μM) in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 and the amount of 2-OH-E+ formed was analyzed by HPLC-EC. The 2-OH-E+ levels in the solution without Fenton’s reagent with (“HE”) and without incubation (“fresh HE”) are shown for comparison. The reaction conditions are similar to those shown in Figure 6.

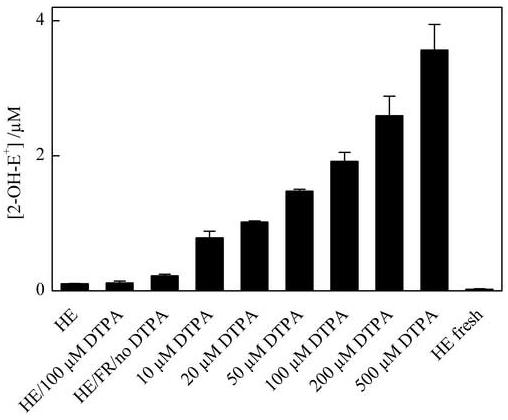

As we observed a significant increase in the formation of 2-OH-E+ (by incubation of HE with Fenton’s reagent alone) that could be inhibited by some hydroxyl radical scavengers, we decided to check whether the Fenton-derived reactive species can oxidize HE to 2-OH-E+. Therefore we checked the effect of Fenton’s reagent components, oxygen, SOD and catalase on 2-OH-E+ formation (Fig. 7B). As SOD almost completely inhibited the formation of 2-OH-E+, we conclude that superoxide radical anion is responsible for oxidizing HE to 2-OH-E+ in this system. Deoxygenation of the reaction mixture inhibited 2-OH-E+ formation as well. Based on these results, we propose that the Fenton’s reagent-induced radical species is able to reduce O2 to O2·-. In addition to reacting with HE, the Fenton-derived reactive species also could react with other components of the Fenton’s system, including H2O2, DTPA, Fe-DTPA complex and phosphate anion. After taking into account the reactivities of these species with ·OH, we conclude that DTPA is the only component present in the Fenton system that can effectively compete with HE for hydroxyl radical. Thus we investigated the effect of DTPA on 2-OH-E+ formation, and the results are shown in Figure 8. As can be seen, the 2-OH-E+ levels increased with increasing DTPA concentration. We suggest that the radical derived from DTPA can react with oxygen to yield the superoxide radical anion.

Figure 8.

The effect of varying concentrations of DTPA on the formation of 2-OH-E+ in the Fenton system. The 2-OH-E+ levels in the solution without Fenton’s reagent with (“HE”) and without incubation (“fresh HE”) are shown for comparison. The reaction conditions are as described in Figure 6.

Discussion

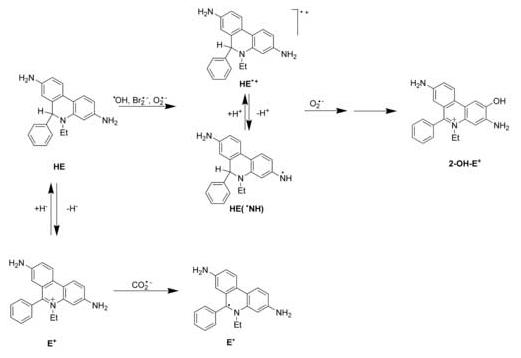

In this study, we present the spectroscopic evidence for the intermediate formed during the reaction of HE with superoxide radical anion. This spectrum resembles that obtained from the one-electron oxidation of HE with Br2·- or ·OH radicals. Therefore, we conclude that the initial step of the reaction of HE with O2·- involves an electron or a hydrogen atom transfer to form the corresponding one-electron oxidized form of HE. To obtain additional insights into the structure of the intermediate, we generated the one-electron reduced form of E+. The spectrum of the one-electron reduction intermediate (E·) is distinctly different from the spectrum obtained from the one-electron oxidation of HE with O2·-, Br2·- or ·OH radicals. Thus, these two species are structurally different.

Because of the structural similarities of HE and benzidine, we propose that the one-electron oxidation of HE results in the formation of the radical cation HE·+ which is in acid-base equilibrium with the aromatic aminyl radical HE(·NH) [29,30]. The aminyl-type radical has previously been suggested as an intermediate during the reaction between HE and Fremy’s salt [10]. The inhibitory effect of acetylation of HE with respect to its O2·- reactivity also tend to support this mechanism [8]. The actual acid-base forms present at pH 7.4 have not been evaluated in the present study; however, if we assume a pKa value similar to that reported for the benzidine radical cation (pKa = 10.9 [29,30]), we can calculate the protonated (radical cation HE·+) form to be predominant at pH 7.4. In fact the spectrum of the one-electron oxidation product of HE resembles that of the benzidine radical cation exhibiting characteristic absorption maxima at 455 and 780 nm [30].

When ethanol or formate was added to the Fenton system, we observed an increase in 2-OH-E+ formation (Fig. 6). This can be explained based on their reactions with ·OH radicals to form the reducing species (hydroxyethyl and carbon dioxide anion radicals) that react with O2 to generate O2·- (see Materials and Methods). Previously, we postulated that the initial radical formed during the reaction of HE with O2·- reacts with another O2·- to form the 2-OH-E+ product [10]. Alternatively, HE·+ or HE(·NH) can react with oxygen to form the peroxyl radical. However, if this were the main route to 2-OH-E+ formation, we should have expected an increase in 2-OH-E+ from incubations containing HE and a strong one-electron oxidants including Br2·- in the presence of oxygen. In contrast, the addition of KBr to the Fenton’s reagent actually decreased the yield of 2-OH-E+ (Fig. 6). Thus, the involvement of a peroxy radical intermediate during the reaction between HE and O2·- is unlikely. This observation is in an agreement with the generally accepted assumption of the lack of reactivity of aromatic aminyl radicals towards molecular oxygen [31].

To our surprise, we found an increase in 2-OH-E+ formation when HE was mixed with the Fenton’s reagent alone. Previously, this was attributed to the reaction between ·OH and HE [32]. However, we found that SOD vastly diminished 2-OH-E+ formation, suggesting that superoxide is responsible for 2-OH-E+ generation in this system. We propose that superoxide is formed in this system from the reaction between the DTPA-derived radical and oxygen. This reaction could explain the DTPA-dependent oxygen consumption in the Fenton’s reaction reported previously [33].

Major findings reported in this study are summarized in Scheme 1. The reaction of HE with Br2·- leads directly to HE·+. The reaction of ·OH with HE leads to HE·+ probably via the pathway involving a direct electron transfer and hydrogen abstraction from the amine group with subsequent protonation of the radicals or adduct formation and elimination of a water molecule or a hydroxyl anion. In the case of O2·- we can expect an electron transfer with direct formation of HE·+ or hydrogen transfer with subsequent protonation of the neutral radical. The reaction of the semi-oxidized form (radical or radical cation) of HE with another O2·- can lead to 2-OH-E+ formation via the quinone imine intermediate, as previously proposed [10]. As shown in Scheme 1, the one-electron reduction of E+ leads to the formation of a neutral radical E· that is a tautomeric form of HE(·NH) radical. In some respects, the redox chemistry of HE is similar to the chemistry of dihydropyridines involving NADH and its analogs, in which the tautomeric (keto-enol) forms of radical cations were observed during stepwise oxidation/stepwise reduction [20 and references therein]. However, unlike NADH, even in the presence of oxygen, the stepwise oxidation of HE, leads to several products whose structures still remain unknown. As presented in Scheme 1, the formation of E+ from HE could be, however, achieved by a direct hydride transfer as evidenced by the chloranil-dependent oxidation of HE to E+ (data not shown). The opposite reaction, direct reduction of E+ to HE can be achieved using the hydride donor, NaBH4, which is a convenient route for synthesis of HE [34].

Scheme 1.

Relevant redox reactions of hydroethidine.

In cellular and biological systems, HE could also be oxidized to HE·+ or HE(·NH) by other oxidants (higher oxidants derived from peroxidases, peroxynitrite, etc.) in addition to O2·-. However, to our knowledge, only O2·- reacts with the intermediate radical to form the specific product, 2-OH-E+ (Scheme 1). Clearly, additional experiments are needed to further elucidate the exact mechanism of the reaction between HE and superoxide radical anion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5P01HL68769-01, 5R01HL067244, 2R01NS39958, and 5R01CA77822. The work performed at Brookhaven National Laboratory was funded under contract DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the US Department of Energy and supported by its Division of Chemical Sciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. T. Sarna thanks Polish Ministry of National Education and Information Technology for financial support (grant BW/WBt/16). The authors wish to thank Diane Cabelli for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Zhao et al. referred to the product of HE and O2·- as “oxyethidium”. The correct term, however, for this product is 2-hydroxyethidium cation (2-OH-E+) [8].

The low yield of the radical formed is attributed to the consecutive reactions of HE radical, namely, the reaction of the radical with another superoxide as well as the self-decay of the radical. The simulation of the reaction kinetics gives the experimental value of the maximal absorbance using a simple model of the reaction of HE with O2·- to give HE radical (k = 2 × 106 M-1s-1), followed by its reaction with another superoxide molecule (k = 2 × 109 M-1s-1) or its self-decay via a second-order process (k = 6 × 108 M-1s-1 estimated from the decay of radical in the system involving Br2·-). The higher rate constant of the HE radical with superoxide is consistent with the literature reports [21].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Tarpey MM, Wink DA, Grisham MB. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004;286:R431–R444. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00361.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fridovich I. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1357–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rothe G, Valet G. J. Leukocyt. Biol. 1990;47:440–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Budd SL, Castilho RF, Nicholls DG. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Han D, Antunes F, Canali R, Rettori D, Cadenas E. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:5557–5563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Walrand S, Valeix S, Rodriguez C, Ligot P, Chassagne J, Vasson M-P. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2003;331:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, Joseph J, Nithipatikom K, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhao H, Joseph J, Fales HM, Sokoloski EA, Levine RL, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5727–5732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fink B, Laude K, McCann L, Doughan A, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C895–C902. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00028.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zielonka J, Zhao H, Xu Y, Kalyanaraman B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;39:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhao H, Joseph J, Zhang H, Karoui H, Kalyanaraman B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nelson DP, Kiesow LA. Anal. Biochem. 1972;49:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:513–886. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schuler RH, Patterson LK, Janata E. J. Phys. Chem. 1980;84:2088–2089. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zehavi D, Rabani J. J. Phys. Chem. 1972;76:312–319. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Adams GE, Willson RL. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1969;65:2981–2987. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bothe E, Schuchmann MN, Schulte-Frohlinde D, von Sonntag C. Z. Naturforsch. 1983;38b:212–219. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zielonka J, Marcinek A, Adamus J, Gȩbicki J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:9860–9864. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gȩbicki J, Marcinek A, Zielonka J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:379–386. doi: 10.1021/ar030171j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;305:729–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chaudhuri S, Phillips GO, Power DM, Davies JV. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1975;28:345–352. doi: 10.1080/09553007514551131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cohen G, Sinet PM. FEBS Lett. 1982;138:258–260. [Google Scholar]

- [24].von Sonntag C. The Chemical basis of radiation biology. Taylor & Francis; London: 1987. pp. 487–491. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bothe E, Schuchmann MN, Schulte-Frohlinde D, von Sonntag C. Photochem Photobiol. 1978;28:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- [26].von Sonntag C, Schuchmann HP. In: Peroxyl radicals. Alfassi ZB, editor. Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 173–234. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schuchmann MN, von Sonntag C. J. Phys. Chem. 1979;83:780–784. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Buxton GV, Sellers RM, McCracken DR. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1976;1 72:1464–1476. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tripathi GNR, Schuler RH. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1988;32:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dey GR, Naik DB, Kishore K, Moorthy PN. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1994;43:481–485. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Merényi G, Lind J. In: The chemistry of N-centered radicals. Alfassi ZB, editor. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 599–613. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Posen Y, Kalchenko V, Seger R, Brandis A, Scherz A, Salomon Y. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1957–1969. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cohen G, Lewis D, Sinet PM. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1981;15:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Thomas G, Roques B. FEBS Lett. 1972;26:169–175. [Google Scholar]