Abstract

This study aimed to compare the antagonistic effects of atipamezole (40, 120, and 320 μg/kg, IM), yohimbine (110 μg/kg, IM), and saline on neurohormonal and metabolic responses induced by medetomidine (20 μg/kg, IM). Five beagle dogs were used in each of the 5 experimental groups in randomized order. Blood samples were taken for 6 h. Medetomidine significantly decreased norepinephrine, epinephrine, insulin, and nonesterified fatty acid levels, and increased plasma glucose levels. Both atipamezole and yohimbine antagonized these effects. The reversal effect of atipamezole was dose-dependency, except on epinephrine. Yohimbine caused prolonged increases in plasma norepinephrine and insulin levels compared to atipamezole, possibly because of its longer half-life elimination. Only yohimbine increased the cortisol levels. Neither glucagon nor lactate levels changed significantly. Based on these findings, when medetomidine-induced sedation is antagonized in dogs, we recommend using atipamezole IM, from 2- to 6-fold the dose of medetomidine, unless otherwise indicated.

Medetomidine, a potent and highly specific α2-adrenoceptor agonist, is often used in veterinary practice as a sedative, analgesic, and muscle relaxant (1). Besides these effects, medetomidine can reduce the stress response to surgery, as assessed by the attenuation of catecholamine, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, and cortisol plasma levels (2). Stress is a generalized response of the body to various factors called stressors. Pain, blood loss, excitement, and underlying pathological conditions may all act as stressors in the surgical patient. The endocrine and metabolic stress response is characterized by the increase of catecholamine; cortisol; glucose; and nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) blood levels, and the decrease of insulin levels (3). Adrenoceptors play an important role in the co-ordination of these events, therefore α2-adrenergic agents may interfere with the pathophysiology of the stress response during and after anaesthesia. That is why there is an increasing interest in using medetomidine as a pre-anaesthetic adjuvant or as part of balanced anaesthesia. If necessary, the actions of medetomidine can be reversed by α2-adrenoceptor antagonists, such as, the highly specific receptor atipamezole or the less specific yohimbine (1). The use of these antagonists may also have adverse effects, like hypotension, tachycardia, over alertness, and the absence of analgesia (1,4). But whether using these antagonists accelerates the stress response and contributes to the fatal outcome of some patients, is not fully understood. The stress-related hormonal and metabolic effects of an antagonist on an α2-agonist, have already been reported in horses (5), cattle, and sheep (6), but not in dogs.

The purpose of this study was to investigate and compare the reversal effects of 3 different doses of atipamezole, and a single dose of yohimbine on stress-related hormonal and metabolic responses following medetomidine administration in dogs. The variables examined were the plasma levels of norepinephrine (NE), epinephrine (EPI), cortisol, glucose, insulin, glucagon, NEFA, and lactate. We hypothesized that the reversal effects of atipamezole were dose-related and similar to the effects of yohimbine.

Our experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Tottori University. Five healthy female beagle dogs, with a mean age of 40 ± 13 mo (mean ± standard deviation (SD)) and weighing 10 ± 2 kg, were used in each of the 5 experimental groups in randomized order at 1 wk intervals. A day before the experiment, a 16 gauge central venous (CV) catheter was introduced into the jugular vein. Food and water were withheld for 12 h before drug injection. The dogs in every experimental group received a 1st treatment of 20 μg/kg medetomidine HCl (Domitor, 1 mg/mL; Meiji Seika Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan) intramuscularly (IM). This was followed 30 min later by a 2nd IM treatment, namely: 0.5 mL physiological saline, 40, 120, or 320 μg/kg atipamezole HCl (Antisedan, 5 mg/mL; Meiji Seika Kaisha), or 110 μg/kg yohimbine HCl (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, USA). The yohimbine injection was prepared in our laboratory (1 mg/mL in aqueous solution). The experimental groups will be hereafter referred to as MED-SAL, MED-ATI 40, MED-ATI 120, MED-ATI 320, and MED-YOH 110, respectively.

The optimal dose of atipamezole was reported to be 4- to 6-fold the dose of medetomidine (4), and that of yohimbine was 110 μg/kg (7). According to our experience 120 μg/kg atipamezole and 110 μg/kg yohimbine were able to antagonize the sedative effect of 20 μg/kg medetomidine with a similar potency. Both yohimbine and atipam-ezole are recommended for IM use under most circumstances (7), to attenuate the side effects of a sudden reversal. Therefore, to model clinical conditions, we administered these drugs through the IM route. Although, the speed and the completeness of absorption may differ among individuals, those differences should also be present under practical conditions.

Blood samples were collected 7 stimes by CV catheter. The initial sample was taken at 0 h (before medetomidine injection), the 2nd at 0.5 h (before antagonist injection), and at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 h after the injection of medetomidine. The sampling and analytical methods were similar to those used by us and published previously (8). Shortly catecholamines were measured by a high performance liquid chromatograph equipped with an electrochemical detector. Cortisol, insulin, and glucagon were detected by radioimmunoassay techniques, and glucose, NEFA, and lactate were detected by a spectrophotometer.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was used to examine time effect within each group and one-way ANOVA was used for treatment effect at each time-point. When ANOVA was significant, the Tukey test was used for the multiple comparisons of the means. Area under curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal method for each individual under the concentration-time curves of the variables measured. The AUC values versus doses of atipamezole were plotted and a linear regression analysis was applied to determine dose-dependency. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 in each test.

Vomiting occurred in 15 occasions (60% incidence), 6.3 ± 3.4 (mean ± SD) min following the medetomidine injections. All dogs became mildly sedated and laterally recumbent at 9.6 ± 4.9 min after the medetomidine treatment. The 1st sign of arousal was observed at 76 ± 49 min following saline; 13 ± 7, 7 ± 3, and 5 ± 2 min after 40, 120, and 320 mg/kg atipamezole IM, respectively; and 18 ± 11 min after yohimbine (110 μg/kg, IM) treatment. The medium and large doses of atipamezole and yohimbine treatments completely reversed the sedative effects of medetomidine, while the animals remained sedated until 149 ± 65 min following a small dose of atipamezole injection. The arousal was smooth after atipamezole treatment, however hyper-alertness, vocalisation, muscle tremor, defecation, and temporary pain at the injection site occurred after the yohimbine injection.

Both the NE and EPI plasma levels (Figure 1), significantly decreased after the medetomidine injection. There was no significant difference between the groups at 0 and 1 h postinjection. In the MED-SAL group, the NE plasma levels remained significantly lowered until 4 h postinjection. Atipamezole dose-dependently reversed these effects. Yohimbine also returned NE levels to baseline at 1 h, but raised them over baseline at 3, 4, and 6 h. On the other hand, EPI plasma levels (Figure 1B) returned to baseline in every antagonist-treated group and did not significantly differ thereafter. The regression analysis confirmed that the effect of atipamezole on EPI plasma levels was not dose-dependent.

Figure 1. Effects of atipamezole (ATI 40, 120, 320 μg/kg IM), yohimbine (YOH 110 μg/kg IM), and saline (SAL IM) on norepinephrine (NE, Figure 1A) and epinephrine (EPI, Figure 1B) plasma levels 30 min following medetomidine (MED 20 mg/kg IM) administration in dogs.

Arrows show the time of MED and antagonist (ANT) injections.

a Significantly different from the initial, 0 h value (P < 0.05).

b Significantly different from the MED-SAL group at that time-point (P < 0.05).

Each point and vertical bar represent the mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 5).

Neither the medetomidine nor atipamezole treatments significantly changed the cortisol plasma levels. In the yohimbine-treated group, however, mean cortisol concentrations increased significantly at 1 h (5.1 ± 0.6 μg/dL), compared with both 0 h (2.0 ± 0.6 μg/dL), and 0.5 h (1.0 ± 0.2 μg/dL) values.

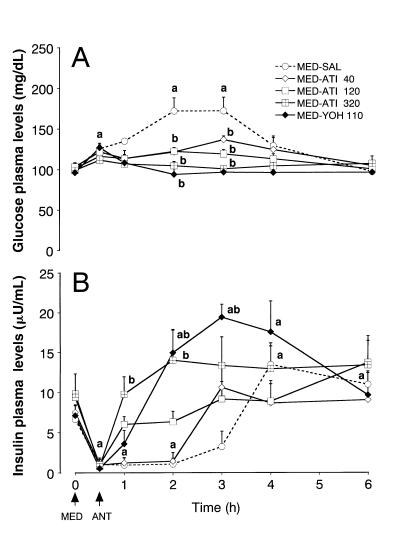

In every group glucose plasma levels (Figure 2A) tended to increase 0.5 h after the medetomidine injection, but it was only significant in the MED-YOH 110 group. However, there was no significant difference between the groups at that time-point. The mean glucose level in the control group increased up to about 170 mg/dL at 2 and 3 h, and then returned to baseline at 4 h. The glucose levels decreased after every antagonist treatment and were not significantly different from the 0 h values thereafter. However, in groups MED-ATI 40 and MED-ATI 120, glucose plasma levels were slightly elevated from baseline at 2 and 3 h. The effect of atipamezole on glucose plasma levels was dose-dependent.

Figure 2. Effects of atipamezole, yohimbine, and saline on glucose (Figure 2A) and insulin (Figure 2B) plasma levels 30 min following medetomidine (MED) administration in dogs.

Arrows show the time of MED and antagonist (ANT) injections.

a Significantly different from the initial, 0 h value (P < 0.05).

b Significantly different from the MED-SAL group at that time-point (P < 0.05).

Each point and vertical bar represent the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 5).

The insulin plasma levels (Figure 2B) decreased after medetomidine treatment, remained significantly lower for 2 h, and then increased above baseline at 4 and 6 h in the MED-SAL group. Atipamezole dose-dependently increased the insulin levels, but this effect in the MED-ATI 40 group was rather weak. Insulin levels increased slowly after the yohimbine injection and were elevated above baseline at 2, 3, and 4 h.

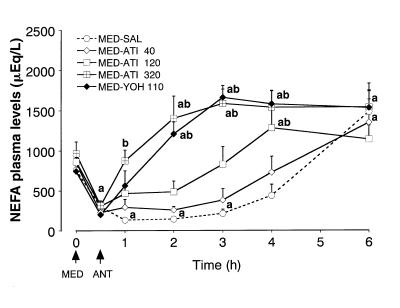

The NEFA plasma levels (Figure 3) decreased significantly in every group after the medetomidine injection, and remained below baseline in the MED-SAL group until 3 h. Atipamezole dose-dependently increased the NEFA levels, but this effect was weak in the MED-ATI 40 group. The NEFA levels were similar in both the highest dose of atipamezole and the yohimbine treatment groups. The glucagon and lactate plasma levels did not change significantly at any sampling time in this experiment.

Figure 3. Effects of atipamezole, yohimbine, and saline on nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) plasma levels 30 min following medetomidine (MED) administration in dogs.

Arrows show the time of MED and antagonist (ANT) injections.

a Significantly different from the initial, 0 h value (P < 0.05).

b Significantly different from the MED-SAL group at that time-point (P < 0.05).

Each point and vertical bar represent the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 5).

In this study, we examined the hormonal and metabolic effects of low, medium, and high doses of atipamezole, and a single dose of yohimbine to reverse the medetomidine-induced sedation. Medetomidine (20 μg/kg, IM) suppressed sympathoneural and adrenomedullary activities (assessed by the decrease of NE and EPI plasma levels), insulin release and lipolysis, and increased glucose plasma levels. The effects of medetomidine were similar to those in our previous study (8). Both atipamezole and yohimbine were able to reverse the effects. Because the antagonistic effects of atipamezole on NE, glucose, insulin, and NEFA plasma levels were dose-related, we accepted our fist hypothesis in these cases. All doses of atipamezole similarly antagonized the suppression of EPI release, consequently we refused the 1st hypothesis for the EPI plasma levels. Even the smallest dose of atipamezole (40 μg/kg IM) effectively antagonized the suppression of adrenomedullary activity and prevented further increase of glucose plasma levels, but the effect of this dose was rather weak on NE, insulin release, and lipolysis. In other words, a small dose of atipamezole could antagonize the hyperglycemic effect of medetomidine, but the insulin levels continued to be low in this group. These data support the theory that α2-adrenergic agents act through glucogenolysis in the liver irrespective of insulin. Our previous study also suggested this possibility (8). The medium (120 μg/kg, IM) and high (320 μg/kg, IM) doses of atipamezole effectively reversed all examined effects of medetomidine. The reversal effects of the medium dose were only moderate on NE, glucose, insulin, and NEFA plasma levels, but the effects of the large dose were always complete.

The potency of yohimbine (110 μg/kg, IM) in reversing the sedative effect of medetomidine was similar to the medium and high dose of atipamezole, but the onset time of the yohimbine effect was longer. The reversal effects of yohimbine on NE, insulin, and NEFA plasma levels were also delayed at 1 h when compared to the high dose of atipamezole. These data suggest that the absorption of yohimbine after an IM injection was slower than that of atipamezole. Yohimbine affected EPI, glucose, and NEFA plasma levels were similar to the high dose atipamezole but increased NE and insulin levels. Also, yohimbine (400 μg/kg, IV) was reported to increase NE, insulin, and NEFA plasma levels in dogs (9). Similarly, a large dose of atipamezole (100 mg, IV) increased NE and EPI plasma levels, while it did not affect cortisol and glucose levels in humans (10). The differences between the actions of atipamezole and yohimbine in the present study may result from the differences in their elimination process from the plasma. When both medetomidine and atipamezole are administered, their half-life elimination is similar, about 1 h in canine plasma (11). On the other hand, yohimbine has much longer half-life elimination, about 16 h in rats (12) and 13 h in humans (13). Consequently, yohimbine might have over-antagonized the actions of medetomidine, after the agonist was already eliminated. In the present experiment, only yohimbine caused increased cortisol levels at 1 h. Therefore, the increase in cortisol levels after the yohimbine treatment is possibly not related to actions on α2-adrenoceptors. For the reasons above, we refused our 2nd hypothesis that the antagonistic actions of atipamezole and yohimbine were similar.

Glucagon levels did not change in the present experiment, similar to our previous study after medetomidine and xylazine treatments (8). Therefore, α2-adrenergic agents may not influence glucagon release in dogs. The lactate plasma levels also did not change in the present study, indicating that the applied dose of medetomidine did not alter anaerobic glycolysis.

We believe that the properties of medetomidine to attenuate the catecholamine and cortisol responses during and after surgery, are desirable and their complete antagonism is normally not indicated. From a pharmacokinetic point of view, yohimbine is not a well-fitted antagonist for medetomidine because of its prolonged actions. Based on these findings, when medetomidine-induced sedation is antagonized in dogs, we recommend using atipamezole IM, from 2- to 6-folds the dose of medetomidine, unless otherwise indicated.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, and Meiji Seika Kaisha, Japan for their support. Also, Fujisawa Pharma for the supply of beagle dogs, and Dr. K. Sato for his technical assistance and valuable suggestions.

Address all correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Yoshiaki Hikasa; telephone/fax: (81) 857-31-5431; e-mail: hikasa@muses.tottori-u.ac.jp

Received December 14, 2001. Accepted May 9, 2002.

References

- 1.Maze M, Tranquilli W. Alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonists: Defining the role in clinical anesthesia. Anesthesiol 1991;74:581–605. [PubMed]

- 2.Benson GJ, Grubb TL, Neff-Davis C, et al. Perioperative stress response in the dog: Effect of pre-emptive administration of medetomidine. Vet Surg 2000;29:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Rosin E. The systemic response to injury. In: Borjab MJ. Pathophysiology in small animal surgery. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1981:3–11.

- 4.Vaha-Vahe AT. The clinical effectiveness of atipamezole as a medetomidine antagonist in the dog. J Vet Pharmacol Therap 1990;13:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Carroll GL, Matthews NS, Hartsfield SM, Slater MR, Champney TH, Erickson SW. The effect of detomidine and its antagonism with tolazoline on stress-related hormones, metabolites, physiologic responses, and behavior in awake ponies. Vet Surg 1997;26:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ranheim B, Horsberg TE, Soli NE, Ryeng KA, Arnemo JM. The effects of medetomidine and its reversal with atipamezole on plasma glucose, cortisol and noradrenaline in cattle and sheep. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2000;23:379–387. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Greene SA. Pros and cons of using α-2 agonists in small animal anesthesia practice. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 1999;14:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ambrisko TD, Hikasa Y. Neurohormonal and metabolic effects of medetomidine compared with xylazine in beagle dogs. Can J Vet Res 2002;66:42–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bagheri H, Chale JJ, Guyen LN, Tran MA, Berlan M, Montastruc JL. Evidence for activation of both adrenergic and cholinergic nervous pathways by yohimbine, an alpha 2-adrenoceptor antagonist. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1995;9: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Karhuvaara S, Kallio A, Scheinin M, Anttila M, Salonen JS, Scheinin H. Pharmacological effects and pharmacokinetics of atipamezole, a novel alpha 2-adrenoceptor antagonist — a randomized, double-blind cross-over study in healthy male volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1990;30:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Salonen S, Vuorilehto L, Vainio O, Anttila M. Atipamezole increases medetomidine clearance in the dog: an agonist-antagonist interaction. J Vet Pharmacol Therap 1995;18:328–332. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hubbard JW, Pfister SL, Biediger AM, Herzig TC, Keeton TK. The pharmacokinetic properties of yohimbine in the conscious rat. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1988;337:583–587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hender T, Edgar B, Edvinsson L, Hender J, Persson B, Pettersson A. Yohimbine pharmacokinetics and interaction with the sympathetic nervous system in normal volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1992;43:651–656. [DOI] [PubMed]