Abstract

Acupuncture analgesia is an important issue in veterinary medicine. This study was designed to elucidate central modulation effects in response to electroacupuncture (EA) at different acupoints. Manganese-enhanced functional magnetic resonance imaging was performed in Sprague-Dawley rats after sham acupuncture, sham EA, or true EA at somatic acupoints. The acupoints were divided into 3 groups: group 1, analgesic acupoints commonly used for pain relief, such as Hegu (LI 4); group 2, nonanalgesic acupoints rarely used for analgesic effect, such as Neiguan (PC 6); and group 3, acupoints occasionally used for analgesia, such as Zusanli (ST 36). Image acquisition was performed on a 1.5-T superconductive clinical scanner with a circular polarized extremity coil. The results showed that there was no neural activation caused by EA at a true acupoint with shallow needling and no electric current (sham acupuncture). When EA at a true acupoint was applied with true needling but no electric current (sham EA), there was only a slight increase in brain activity at the hypothalamus; when EA was applied at a true acupoint with true needling and an electric current (true EA), the primary response at the hypothalamus was enhanced. Also, there was a tendency for the early activation of pain-modulation areas to be prominent after EA at analgesic acupoints as compared with nonanalgesic acupoints. In conclusion, understanding the linkage between peripheral acupoint stimulation and central neural pathways provides not only an evidence-based approach for veterinary acupuncture but also a useful guide for clinical applications of acupuncture.

Introduction

In the past decade, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) as well as positron emission tomography (PET) have been generally accepted as strong tools for providing detailed information in the noninvasive mapping of brain function (1,2). For example, fMRI analysis clearly identifies the structures activated during the brain's processing of pain, and the intensity of the response in regional cerebral blood flow correlates parametrically with perceived pain intensity (3,4). Nevertheless, the informative data about pain-modulation mechanisms in animals remain to be elucidated.

The recognition and alleviation of animal pain is a growing veterinary and public concern. Previously, much effort was devoted to studies of pain management in both large and small animals, such as dogs and cats (5). Accumulating knowledge of the physiologic and pharmacologic features of pain from human imaging has had a significant impact on clinical veterinary medicine (6,7). Several lines of evidence suggest that acupuncture is effective for treating not only human diseases (8) but also animal disorders (9,10,11). For example, Hegu (LI 4) is an acupoint commonly chosen for acupuncture analgesia (9), and electroacupuncture (EA) at acupoint Neiguan (PC 6) inhibits the bradykinin-induced cardiac pressor response and consequently improves the function of ischemic myocardium in rats (12). The better outcome with EA is postulated to depend on the activation of opioid receptors, especially those in the rostral ventrolateral medulla, which is responsible for maintaining blood pressure and integrating cardiovascular reflexes (13). In addition, EA stimulation of acupoint Riyue (GB 24) regulates the motility of the sphincter of Oddi (SO) in rabbits and cats through a somatovisceral reflex mediated by the secretion of cholecystokinin (14). Although the brain plays important roles in modulating body responses to peripheral stimulation, the link between acupuncture effects and central cortical modulation remains unclear.

Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between acupuncture stimulation and cortical activation in the brain (15,16). The involvement of the hypothalamic–limbic system has been postulated to be critical in the mechanism of acupuncture analgesia (17). It is generally accepted that manganese, a paramagnetic contrast agent, can be used in vivo to provide higher functional resolution for fMRI in static states (18). By using Mn2+-fMRI in our previous study, we found brain activation to be primarily in the hippocampus when EA was applied at acupoint Zusanli (ST 36) and in the hypothalamus, insula, and motor cortex when EA was applied at acupoint Yanglingquan (GB 34) (19). Recently we found that EA at Hegu (LI 4), an acupoint known to be effective in acupuncture analgesia, induced central neural activation in pain-modulation areas, such as periaqueduct grey matter (PAG) and the median raphe nucleus (MnR), whereas EA at Riyue (GB 24), an acupoint known to be effective in SO relaxation, induced less or no activation in such areas.

Since information about the correlation between central effects and EA stimulation at different acupoints (analgesic or nonanalgesic) is lacking, we investigated the correlation between acupuncture effects, target specificity, and brain modulatory mechanisms with the aid of Mn2+-fMRI.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental protocol

Thirty-eight male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250 to 300 g were obtained from the animal centre of the National Science Council or National Yang-Ming University. They were treated according to the principles outlined by the US National Institutes of Health (20). The experiment was performed as described previously (19), with some modification. Briefly, after food was withheld overnight but free access to water was allowed, the animals were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (35 mg/kg body weight (BW), administered intramuscularly), anesthesia was maintained with urethrane (125 mg/100 g BW, administered intraperitoneally) (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and additional low doses of ketamine (5 to 10 mg/kg) were given as needed. The depth of anesthesia was kept steady, such that heart rate and arterial blood pressure were not affected and there was no pain response to skin traction. Usually the rectal temperature was kept around 38°C with the use of an intermittent heating pad throughout the procedure. Catheters were placed in a femoral artery and vein for monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure. A catheter was also placed in a carotid artery for administration of drugs. A polyethylene tube (PE-50) was positioned in the external carotid artery (ECA), which was ligated distal to the entrance of the tube. The tip of the catheter was located at the junction between the ECA and the internal carotid artery (ICA), so that blood flowed to the brain through the ICA during periods when drugs or saline (0.9% NaCl) solution was not being infused. Hypertonic (20%) D-mannitol solution (5 mL/kg) was administered via the ICA to break down the blood–brain barrier, and MnCl2 (120 mM in isotonic saline solution, 0.5 mg/kg) was administered for manganese-enhanced fMRI.

Functional MRI

The fMRI studies were performed with a circular polarized extremity coil in a 1.5-T superconductive magnet (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Multislice, T1WI conventional spin-echo images (TR, 400 ms; TE, 12 ms) were acquired. A 116 × 128 matrix with a 5-cm field of view was used. Slice thickness was 4 mm. For better resolution and registration of anatomic structures, images were acquired with the 3D Fast Low Angle Shot (FLASH) (TR, 50 ms; TE, 10 ms; flip angle, 50°; matrix, 128 × 128; field of view, 64 mm; slice thickness, 0.5 mm) after completion of EA.

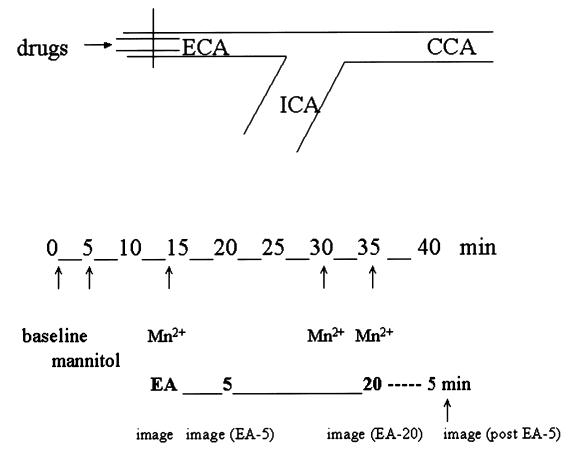

To separate nonspecific and specific signal enhancement, we obtained 5 series of images. Baseline fMRI was performed at 0 min. At 5 min, mannitol was infused and a 2nd series of images obtained. At 10 min, MnCl2 was infused and a 3rd series obtained. At 15 min, EA was begun at the acupoints to be studied. A 4th series of images was obtained 5 min after initiation of EA stimulation. To study the aftereffect of acupuncture treatment, we administered MnCl2 at the end of EA or after removal of the needles and obtained images 5 min later. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Experimental setup. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was performed at baseline and the indicated number of minutes after mannitol administration, MnCl2 injection, electroacupuncture (EA), and the end of EA stimulation or removal of the needles. ECA — external carotid artery; ICA — internal carotid artery; CCA — common carotid artery.

Electroacupuncture

The EA was performed by applying an electric current with an electrical nerve stimulator (Han Acutens, LH 202H, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China) to 2 fine needles (1 and 1.5 mm) positioned 2 to 3 mm apart at 1 acupoint to prevent a short circuit. The nomenclature of the acupoints was standardized (21,22). Stimulation was pulse-waved with alternate frequencies of 2 and 15 Hz. Wave width was 300 μs, stimulation duration 20 min, and intensity of stimulation between 1 and 2 mA.

Study design

The rats' acupoints were arbitrarily divided into 3 groups (19,22): group 1, analgesic acupoints commonly used in humans or in animals, such as Hegu (LI 4), Sanyinjiao (SP 6), and Yanglingquan (GB 34); group 2, nonanalgesic acupoints rarely used for analgesic effect, such as Neiguan (PC 6), Riyue (GB 24), and Feishu (BL 13); and group 3, acupoints occasionally used for analgesia, such as Zusanli (ST 36) and Zhiyin (BL 67). These choices were based on scientific studies (9,12,13,19,22), the ancient Chinese literature, and advice of senior acupuncturists at the Veterans General Hospital, Taipei.

Data analyses

Data analyses were managed by a biomedical statistical group, including statisticians from National Yang-Ming University, Veterans General Hospital (Taipei), and Academia Sinica, Republic of China. The fMRI signals in 4 series of images (after mannitol infusion, after the beginning of the Mn2+ infusion, after EA, and after the end of the Mn2+ infusion) were compared to separate the nonspecific signal enhancement in Mn2+-fMRI. High-resolution 3-dimensional MRI images were analyzed by subtraction. All images were made with the same grey scale, and signal intensity of neural activation in the brain was graded as negative (−), borderline (±, defined as < 10% of vascular or intraventricular intensity), slightly increased (+, defined as 10% to 50% of vascular or intraventricular intensity), or markedly increased (++, defined as > 50% of vascular or intraventricular intensity). The neural activation was localized according to the stereotaxic reference system described previously (24).

Results

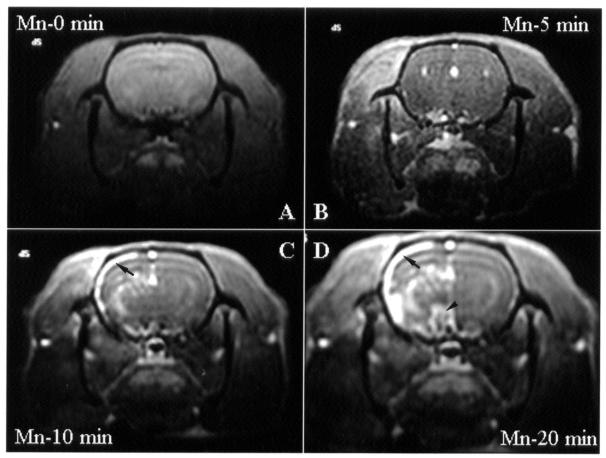

There was no obvious brain activation immediately after infusion of mannitol or MnCl2 (data not shown). Since Mn2+ is neurotoxic, prolonged exposure to MnCl2 resulted in time-dependent brain activation (Figure 2; n = 4); therefore, we reduced the infusion time to 5 min. In addition, since MnCl2 interference was noticed in rats receiving repeated or sequential treatment at different acupoints, each rat was given only 1 treatment at 1 acupoint.

Figure 2. Transverse images obtained by manganese-enhanced functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Mn2+-fMRI) of the brain of rats at baseline (A) and 5, 10, and 20 min after infusion of MnCl2 into the internal carotid artery (ICA). No electroacupuncture (EA) was done. Images were obtained at the level of the hypothalamus and thalamus. Nonspecific increases in signal intensity are apparent in the cortex (arrow) and in the hypothalamus (arrowhead).

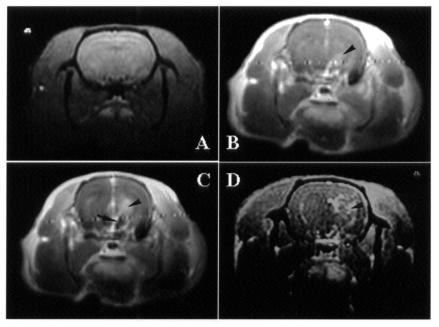

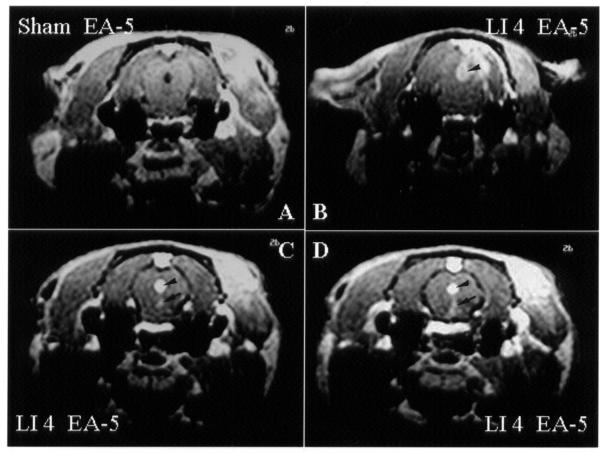

To elucidate the specificity of EA stimulation, changes in brain activity were evaluated by Mn2+-fMRI in different control manipulations (2 to 3 rats per group). When the stimulation was at a true acupoint with shallow needling and no electric current (sham acupuncture), no change in central neural activity was noticed (Figure 3A). When the stimulation was at a true acupoint with true needling but no electric current (sham EA), there was a slight increase in brain activity in the area of the hypothalamus (Figure 3B). However, the primary response in the hypothalamic region was enhanced with EA at a true acupoint (true EA) (Figure 3C). Interestingly, an increase in brain activity was also noticed with EA stimulation at a control acupoint (EA at sham point) 3 mm from the true acupoint [Hegu (LI 4)] (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Transverse images obtained by Mn2+-functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain of rats 5 min after the start of acupuncture stimulation. A: Sham acupuncture (stimulation at a true acupoint [Hegu (LI 4)], with shallow needling and no electric current). B: Sham electroacupuncture (EA) (stimulation at Hegu with true needling but no electric current). C: True EA (stimulation at Hegu with true needling and an electric current). D: Control EA (stimulation at a control acupoint 2 mm from a true acupoint, with true needling and an electric current). Increased signal intensity is apparent in the hypothalamus (arrow) and in the thalamus (arrowhead).

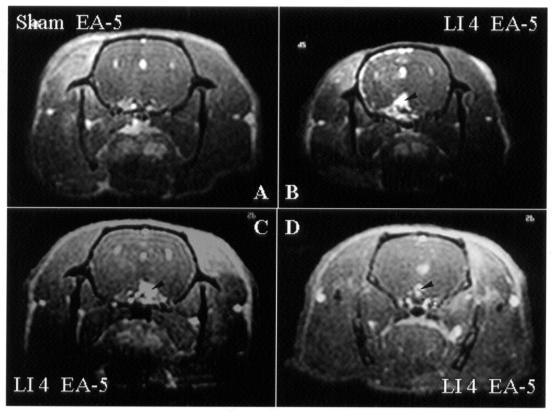

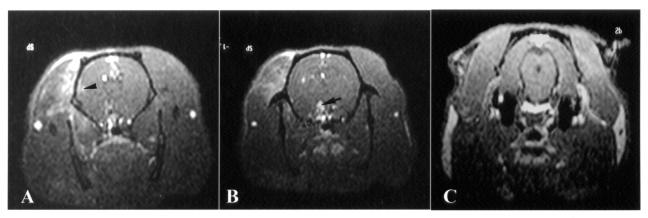

Since acupuncture analgesia is the most widely accepted function of acupuncture treatment, Hegu (LI 4), an acupoint known to be effective in pain relief, was chosen to correlate the brain-activation areas with EA stimulation. There was consistent neural activation in the hypothalamus (Figure 4, panels B–D; n = 4), PAG (Figure 5, panels B–D; n = 4), and MnR (Figure 5, panels C and D; n = 3) after EA at Hegu (LI 4) for 5 min. After EA at acupoint Riyue (GB 24) for 5 min, there was an increase in brain activity in the somatosensory area (Figure 6A) and the hypothalamus (Figure 6B) but not in the PAG (Figure 6C). Table I summarizes the areas of brain activation by EA applied for 5 min at different acupoints known to have different functions, such as analgesia or modulation of visceral functions. A tendency to activation of pain-modulation areas such as PAG and MnR was noticed with EA at group-1 (analgesic) acupoints, whereas little neural activation was noticed in these areas with EA at group-2 (nonanalgesic) acupoints.

Figure 4. Transverse images obtained by Mn2+-functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain of rats 5 min after the start of electroacupuncture (EA) at Hegu (LI 4) in different animals (B–D), at the level of the hypothalamus and thalamus. As compared with sham EA (A), true EA results in an increase in signal intensity in the hypothalamus (arrowhead).

Figure 5. Transverse images obtained as with Figure 4 but at the level of the midbrain. As compared with sham electroacupuncture (EA) (A), true EA results in an increase in signal intensity in the periaqueduct grey (PAG) matter (arrowhead) and in the median raphe nucleus (MnR) (arrow).

Figure 6. Transverse images obtained by Mn2+-functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain of rats at the level of the hypothalamus and thalamus (A and B) and the midbrain (C). Increased signal intensity 5 min after the start of electroacupuncture (EA) at Riyue (GB 24) is apparent in the sensory cortex (A, arrowhead) and in the hypothalamus (B, arrow) but not in the PAG and MnR regions (C).

Table I.

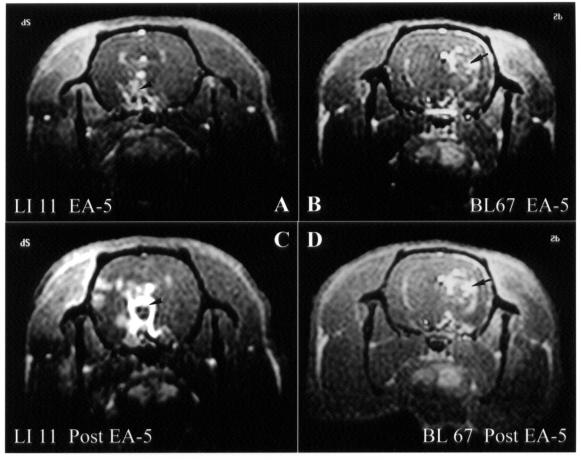

To study the change in brain neural activity after the end of EA (post-EA effect), brain images were taken 5 min after the completion of EA stimulation and the removal of the needles from the acupoints. There was an increase in signal changes in the hypothalamus, insula, and sensory cortex 5 min after the end of EA at Hegu (LI 4), whereas the signal changes were persistent in the hypothalamic and thalamic areas 5 min after the end of EA at Zhiyin (BL 67) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Transverse images obtained by Mn2+-functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain of rats at the level of the hypothalamus and thalamus 5 min after the start of electroacupuncture (EA) at Quchi (LI 11) (A) and Zhiyin (BL 67) (B) and 5 min after the end of EA or the removal of the needles from the Quchi (C) and Zhiyin (D) acupoints. Increased signal change is apparent in the hypothalamus, insula, and sensory cortex 5 min after the end of EA at Hegu (LI 4), whereas the signal changes are persistent in the hypothalamus (arrow) and thalamus (arrowhead) 5 min after the end of EA at Zhiyin.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated, using Mn2+-fMRI, a correlation between acupoint-specific EA stimulation and central activation of pain-modulation areas in the brain. To our knowledge, these are novel findings.

Because depth of anesthesia may affect brain activity (for example, there is nonspecific activation with minimal anesthesia and hypoactivity with deep anesthesia), a steady depth is mandatory to allow measurement of specific brain activity. Several lines of evidence suggest that anesthetized small animals are good models for studies of acupuncture effects (6,9,25). We maintained the animals at a surgical plane of anesthesia without affecting heart rate or arterial blood pressure and without inducing signs of pain in response to skin traction. Furthermore, results of this and a previous study indicated that fMRI of the brain could be performed in anesthetized rats (26).

Intravenous administration of mannitol followed by manganese is a useful fMRI technique to separate stimulation-specific signal enhancement from nonspecific enhancement (18,27). Manganese, a paramagnetic calcium analog, is a good contrast agent, entering cells through voltage-gated calcium channels. Moreover, manganese-induced activity-specific contrast is independent of cerebral blood flow. Our previous study indicated that manganese could be used as a contrast agent to monitor brain activation by use of fMRI (19). Since Mn2+ is neurotoxic, and prolonged exposure to MnCl2 results in time-dependent brain activation similar to primary responses induced by EA stimulation (Figure 2), we designed our experiments to avoid this confounding effect, limiting the infusion time for MnCl2 to 5 min.

Recent evidence in humans as well as in animals indicates that fMRI is able to detect brain activation in response to pain, thereby identifying regions involved in the central processing of pain (3). Following episodes of intense electrical stimulation on the forepaw of rats, activation was observed consistently in the contralateral sensory–motor cortex and frontal cortical regions and frequently in the anterior cingulate cortex and the ipsilateral sensory–motor cortex (28,29). In addition to these regions, the claustrum, ventral thalamic nucleus, interpeduncular nucleus, PAG, hippocampus, and insular and pyriform cortices have been implicated in the response of the central nervous system to pain in the rat (28,29). Interestingly, the activation seemed to appear sequentially in these regions. Accumulating evidence suggests that fMRI is playing an important role in elucidating the central mechanism of acupuncture effects. Cho et al (15) found a correlation between visual cortical activation and acupuncture at acupoint BL 67 as well as between auditory cortical activation and acupuncture at acupoint SJ 5. Furthermore, findings suggest a central nervous mechanism for acupuncture analgesia and a critical role for the hypothalamic–limbic system in this pathway (17). Since acupuncture is a manipulation evoking a sensory stimulation similar to peripheral stimulation (pain, touch, etc.), it is not surprising to find overlapping activation regions for acupuncture stimulation and pain stimulation.

It is generally accepted that clinically relevant acupuncture-induced body responses usually require prolonged and multiple stimulation sessions. The needed duration of acupuncture stimulation is within minutes for De-Qi (pronounced De-Chi) (16), 15–20 min for cholecystokinin-8 secretion (14), and 20–40 min for antinociceptive effect (9). Because of ethical considerations, it has been difficult to assess the analgesic effect of acupuncture in humans by the use of fMRI. The results of this study showed consistent neural activation in the hypothalamus by EA stimulation for 5 min at nearly all acupoints, whereas pain-modulation areas such as PAG and MnR seemed to be activated early by EA only at analgesic acupoints. These findings are consistent with previous reports that the descending antinociceptive systems, including the hypothalamus, the nucleus accumbens, and the mesencephalon (PAG and raphe nuclei), are important central pathways mediating acupuncture analgesia (17). Our previous studies designed to investigate acupuncture effects in a time-dependent manner showed that 5 min of EA stimulation at different acupoints induced more specific brain activation than 20 min of stimulation at these acupoints. This phenomenon might explain the clinical observation that an analgesic effect can be induced by EA at several acupoints (19). EA at acupoint PC 6 leads to neural activation in the hypothalamus and primary sensorimotor areas but not in pain-modulating areas (PAG and MnR). Since acupoint PC 6 is supplied by the median nerve, this observation is in agreement with the finding that electrical stimulation of the median nerve leads to functional activation of the S1 and M1 cortex (30,31). Taking these findings together with our preliminary data, we assume that EA at acupoints causing early activation (within 5 min) of pain-modulation areas might result in better pain relief. However, this postulation requires further investigation, both experimental and clinical.

The advantages of using Mn2+-fMRI to interpret acupuncture effects are 2-fold. First, the linkage of acupoints with cerebral function can be demonstrated in vivo. Second, manganese-enhanced fMRI requires less time for image processing than conventional fMRI. However, there are some drawbacks to Mn2+-fMRI. First, unilateral injection of mannitol and MnCl2 into the ICA precludes detection of cerebellar and contralateral brain activity. Second, change in brain activity detected by the use of Mn2+-fMRI indicates the mobilization of cellular ions as a result of activation or deactivation of central neurons; therefore, it is unclear whether the actual change in brain activity is activation or deactivation in conditions in which EA stimulation at different acupoints results in similar fMRI manifestations. Third, Mn2+-fMRI allows only qualitative or semi-quantitative evaluation of brain images (18). In this study, the signal intensity in regions of interest was compared objectively with that in the intravascular or intraventricular space and was graded semi-quantitatively. Recently, monocrystalline iron oxide nanocolloid (MION) has been reported as a good contrast agent for quantitative fMRI analyses (32), and we are now investigating its use. In the West, acupuncture has been largely considered as having a psychological or hypnotic effect or a placebo effect rather than being a physiologically based treatment. A number of significant correlations between acupuncture stimulation and cortical activation have recently been observed. In addition, marked changes have been noted in central neural activation with true EA (EA at a true acupoint with true needling and an electric current), whereas no activation was observed with sham acupuncture (stimulation at a true acupoint with shallow needling and no electric current), and very little activation was observed with sham EA (EA at a true acupoint with true needling but no electric current). Although the data are very preliminary, they bring into perspective the application of acupuncture analgesia in clinical veterinary medicine.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NSC90-2320-B-010-054 and project of excellency (88-FA22-A), Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Address all correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Jen-Hwey Chiu; telephone: 886-2-2826-7178; fax: 886-2-2875-7537; e-mail: chiujh@mailsrv.ym.edu.tw

Received March 4, 2002. Accepted July 23, 2002.

References

- 1.Belliveau JW, Kennedy DN, McKinstry RC, et al. Functional mapping of the human visual cortex by magnetic resonance imaging. Science 1991;254:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:5675–5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wiech K, Preissl H, Birbaumer N. Neural networks and pain processing. New insights from imaging techniques. Anaesthesist 2001;50:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Casey KL. Forebrain mechanisms of nociception and pain: analysis through imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:7668–7674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Mathews KA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics. Indications and contraindications for pain management in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000;30:783–804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Tuor UI, Malisza K, Foniok T, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in rats subjected to intense electrical and noxious chemical stimulation of the forepaw. Pain 2000;87:315–324. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lamont LA, Tranquilli WJ, Grimm KA. Physiology of pain. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000;30:703–728. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for Western Pacific, 1980.

- 9.Han JS. The Neurochemical Basis of Pain Relief by Acupuncture. Hubei, China: Hubei Science & Technology Press, 1998:110–188.

- 10.Nam TC, Seo KM, Chang KH. Acupuncture anesthesia in animals. In: Lin JH, Wu LS, Rogers AM, Watkins D, Boldt E, eds. Sustainable Medicine for Animals. Intl Vet Acup Soc & Chin Sco Trad Vet Sci 2002:67–84.

- 11.Chan WW, Chen KY, Liu H, Wu LS, Lin JH. Acupuncture for general veterinary practice. J Vet Med Sci 2001;63:1057–1062. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Li P, Pitsillides KF, Rendig SV, Pan HL, Longhurst JC. Reversal of reflex-induced myocardial ischemia by median nerve stimulation: a feline model of electroacupuncture. Circulation 1998;97:1186–1194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Chao DM, Shen LL, Tjen-A-Looi S, Pitsillides KF, Li P, Longhurst JC. Naloxone reverses inhibitory effect of electroacupuncture on sympathetic cardiovascular reflex responses. Am J Physiol 1999;276:2127–2134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chiu JH, Kuo YL, Lui WY, Wu CW, Hong CY. Somatic electrical nerve stimulation regulates the motility of sphincter of Oddi in rabbits and cats: evidence for a somatovisceral reflex mediated by cholecystokinin. Dig Dis Sci 1999;44:1759–1767. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Cho ZH, Chung SC, Jones JP, et al. New findings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:2670–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 16.Hsieh JC, Tu CH, Chen FP, et al. Activation of the hypothalamus characterizes the acupuncture stimulation at the analgesic acupoint in human: a positron emission tomography study. Neurosci Let 2001;307:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wu MT, Hsieh JC, Xiong J, et al. Central nervous pathway for acupuncture stimulation: localization of processing with functional MR imaging of the brain-preliminary experience. Radiology 1999;212:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lin YJ, Koretsky AP. Manganese ion enhances T1-weighted MRI during brain activation: an approach to direct imaging of brain function. Magn Reson Med 1997;38:378–388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Chiu JH, Cheng HC, Tai CH, et al. Electroacupuncture-induced neural activation detected by use of functional manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in rabbits. Am J Vet Res 2001;62:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.National Institutes of Health. Revised Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996:25.

- 21.Hua XB. On animal acupoints. J Tradit Chin Med 1987;7:301–304. [PubMed]

- 22.Du W, Chen Y, Chen Z, eds. The Locations of Acupoints. Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press, 1990.

- 23.Chiu JH, Chen YL, Lui WY, Hong CY. Local somatothermal stimulation inhibits the motility of sphincter of Oddi in cats, rabbits and humans through neural release of nitric oxide. Life Sci 1998;63:413–428. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C, eds. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 4th ed. San Diego, California: Academic Press, 1998.

- 25.Jiang JK, Chiu JH, Lin JK. Local thermal stimulation inhibits the motility of internal anal sphincter through nitrergic neural release of nitric oxide. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Scanley BE, Kennan RP, Cannan S, Skudlarski P, Innis RB, Gore JC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of median nerve stimulation in rats at 2.0 T. Magn Reson Med 1997;37:969–972. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Pautler RG, Silva AC, Koretsky AP. In vivo neuronal tract tracing using manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 1998;40:740–748. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Porro CA, Cettolo V, Francescato MP, Baraldi P. Temporal and intensity coding of pain in human cortex. J Neurophysiol 1998;80:3312–3320. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Davis KD, Kwan CL, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ. Functional MRI study of thalamic and cortical activation evoked by cutaneous heat, cold and tactile stimuli. J Neurophysiol 1998;80:1533–1546. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Spiegel J, Tintera J, Gawehn J, Stoeter P, Treede RD. Functional MRI of human primary somatosensory and motor cortex during median nerve stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 1999;110:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kampe KKW, Jones RA, Auer DP. Frequency dependence of the functional MRI response after electrical median nerve stimulation. Human Brain Map 2000;9:106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]