Abstract

Leptospirosis, caused by spirochetes of the genus Leptospira, has increasingly been recognized to affect travelers and residents in tropical settings. A zoonotic disease, leptospirosis is transmitted to humans through environmental surface waters contaminated by the urine of chronically infected mammals. Outcome of infection varies, ranging from acute febrile illness (including self-resolving undifferentiated fever) to aseptic meningitis to a fulminant syndrome of jaundice, oliguric renal failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, and refractory shock. Hospitalized cases have mortality rates as high as 25%. A recent clinical trial showed that third-generation cephalosporin is as effective as doxycycline and penicillin in the treatment of acute disease. Doxycycline is effective in preventing leptospirosis in travelers. No protective vaccine is currently available.

Introduction

Leptospirosis, caused by spirochetes of the genus Leptospira, is a geographically widespread zoonosis. It is commonly overlooked as a cause either of undifferentiated fever or fulminant, multisystem disease. The severe pulmonary form of leptospirosis manifesting as hemorrhage has globally emerged as a clinical important form of this disease [1–3,4••]. In recent years, leptospirosis has increasingly been recognized as an urban disease in both industrialized and developing countries [5,6], as an endemic disease with substantial morbidity in tropical settings [4••,7,8•], and, increasingly, as a disease associated with exotic exposures, whether among adventure travelers [9–13] or military personnel [14]. A recent case was described in which a medical school professor acquired leptospirosis while chasing gliders with her son through soggy grounds in upstate New York [15]. A now classic aphorism in leptospirosis is that the disease is found wherever looked for [16,17].

Here we will discuss clinically important aspects of leptospirosis. For discussions of new advances in basic science aspects of Leptospira and leptospirosis, the reader is referred to recently published reviews [18,19••]. This report focuses on the microbiology of Leptospira relevant to diagnosis and the clinical manifestations of leptospirosis. We will focus on clinical manifestations of leptospirosis in travelers, using the 2000 Eco-Challenge Sabah leptospirosis outbreak [10] as an example of how clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for the highly variable manifestations of this disease. Finally, we will discuss current approaches to treatment and prevention based on lessons learned from recent clinical trials and outbreaks.

Diagnostic Microbiology

Leptospirosis is caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. At least eight identifiable Leptospira species cause human disease. Leptospira are conventionally classified serologically with antisera raised in rabbits that react predominantly against the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on the leptospiral surface. Within the eight species of pathogenic Leptospira, there are more than 230 serovars. These are further divided into 23 serogroups based on antibody-mediated agglutination reactions using rabbit reference sera. The serologic classification of Leptospira is important to know because reference laboratory diagnosis uses live Leptospira representing each serogroup in the microscopic agglutination assay (MAT) to determine the presence of anti-leptospiral antibodies.

Pathogenic Leptospira are fastidious organisms and require specialized media for isolation; such media are Ellinghausen McCullough Johnson Harris medium (EMJH; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and Fletcher’s (beef extract-based; easily made in most clinical microbiology laboratories). Leptospira can be isolated from blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and peritoneal dialysate in the first week of illness (Table 1), preferably before antibiotics are started. Blood cultures cultured in BACTEC™ (Becton, Dickinson, and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ), VITAL (bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO), and other automated blood culture systems can be subcultured into leptospiral culture medium; earlier is better, and blood cultures kept at 30° C rather than 37° C sustain Leptospira longer [20]. After the first week, leptospires can be isolated from urine; optimally, urine should be diluted 1/10 in 1% bovine serum albumin or neutralized to a pH of 7.2 to 7.4 prior to transport to the clinical microbiology laboratory or prior to inoculating into medium. Culture media are inoculated with one to two drops and a 1/10 dilution of one drop of blood or urine, preferably at the bedside; larger inocula inhibit growth. Even in serologically confirmed cases, the organism is usually not recovered. Cultures are examined by darkfield microscopy weekly and have to be kept at least 8 to 12 weeks (sometimes longer) before discarding as negative. Thus culture isolation of leptospires is impractical either as a definitive diagnostic test or as a test to guide therapy.

Table 1.

Laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis

| Weeks 1–2 | Weeks 2–10 |

|---|---|

| Isolation in pure culture | Isolation in pure culture |

| Blood, urine (after 5 days of illness) | Urine |

| Antibody detection | Antibody detection |

| IHA, IgM ELISA, IgM dot blot/lateral flow assay | IgM, IgG ELISA, IgM, IgG dot blot/lateral flow assay |

| Microscopic agglutination test | Microscopic agglutination test |

| PCR on whole blood, serum | PCR on urine |

ELISA—enzyme linked immunsorbent assay;

IHA—indirect hemagglutination; PCR—polymerase chain reaction.

Direct darkfield microscopy of serum, plasma, CSF, peritoneal dialysate and urine to determine the presence of motile spirochetes has been advocated as a rapid diagnostic test [21–24] but lacks sensitivity and specificity (due to misinterpretation of fibrin or protein threads that appear motile due to Brownian movement) [25].

Serology remains the most common way to diagnose leptospirosis. MAT is the gold standard serologic test. This test uses live, in vitro, cultivated leptospires from representative serogroups; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses an MAT antigen panel of 23 serovars [18,25]. MAT is only performed in reference labs and requires acute and convalescent samples for diagnostic confirmation. MAT-detectable antibodies usually do not develop before the end of the first week of illness. Criteria for diagnosis include seroconversion between acute and convalescent serum samples (definitive); fourfold rise in titer (definitive); or a single high titer (> 1/400) (suggestive). The operating characteristics of the MAT limit its use primarily to retrospective diagnosis.

Despite antigenic differences among Leptospira, serologic tests using a single leptospiral antigen to detect leptospiral antibodies have been developed. These tests use lysates of a nonpathogenic leptospire, Leptospira biflexa, whose antigens (primarily a simple LPS [26]) cross-react with many (but not all [14]) leptospires [27]. Indirect hemagglutination (sensitized red cells) [28,29•], enzyme linked immunsorbent assay (ELISA) and lateral flow (dip-stick) assays [29•,30–35] have been exhaustively tested using L. biflexa antigen. ELISA and lateral flow tests are largely comparable in sensitivity and specificity but are generally greater than 80% sensitive and specific when acute and convalescent samples are tested [19••] (Table 1). The indirect hemagglutination test is less sensitive; latex agglutination assays are sensitive but have lower specificity. When testing only acute samples, sensitivity of L. biflexa–based ELISA and lateral flow assays ranged from 40% to 70%. Sensitivity of an IgM ELISA was highest when testing sera from patients within 1 week after the onset of illness but never exceeded 50% with acute damples. If feasible, MAT should be used to confirm the diagnosis.

The most sensitive and accurate tests to diagnose leptospirosis are based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), currently performed only in research laboratories. PCR can detect leptospires early in disease [36]. Quantitative PCR techniques, prognostically useful, have shown that higher leptospiral burden (> ~104–5 of leptospires/mL of blood) is associated with worse disease [4••,37,38]. Demonstration of the presence of Leptospira by antigen detection to diagnose leptospirosis is currently under development but it remains to be shown whether these antigen detection tests are sufficiently sensitive to diagnose disease caused by different infecting leptospiral strains [39,40].

Clinical Presentations of Leptospirosis: Importance of Outbreak Investigations

In September 2000, the CDC was notified by the GeoSentinal Global Surveillance Network, the Idaho Department of Health, and the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services of an outbreak of acute febrile illness among travelers returning from participation in the Eco-Challenge Sabah 2000 multisport expedition race in Borneo, Malaysia. These patients reported the abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgias, and headache variably accompanied by diarrhea and conjunctival suffusion. An astute infectious disease clinician in Los Angeles was the first to clinically suspect leptospirosis [41]. Quickly, through the GeoSentinel network, it became clear that a number of cases of acute febrile illness among returning travelers from the Eco-Challenge race was occurring and that an outbreak of leptospirosis had occurred [10,42]. The etiology of this outbreak was confirmed at the CDC. Epidemiologic investigation suggested that the Segama River in Borneo was the point source of the outbreak. Of substantial importance, those Eco-Challenge athletes who had taken doxycycline were relatively protected from infection [10,41].

The clinical manifestations of leptospirosis in the Eco-Challenge outbreak were similar to other outbreaks, for example affecting triathletes swimming in Lake Spring-field, Illinois [43] or whitewater rafters in Costa Rica [9]. The risk for acquiring leptospirosis for participants in water sports indicates a possible need for prophylaxis in this setting [41]; many travel medicine consultants now recommend such prophylaxis.

The incubation period of leptospirosis is 3 to 14 days. Signs and symptoms are highly variable. Asymptomatic seroconversion may be the most common result of infection [44]. The mildest clinical expression of leptospirosis is that of undifferentiated fever—fever, headache, myalgia—which may be accompanied by other nonspecific findings such as nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, nonproductive cough, and maculo-papular rash. Conjunctival suffusion (red eyes without exudate) and severe calf pain may be characteristic of acute leptospirosis but are not specific. Mild leptospirosis resolves spontaneously without requiring antimicrobial therapy. Severe manifestations of leptospirosis include any combination of jaundice, renal failure, hemorrhage (most commonly pulmonary), myocarditis, and hypotension refractory to fluid resuscitation. Other complications include aseptic meningitis and ocular involvement including uveitis [45]. If patients recover, there are no permanent sequelae, although there are anecdotal reports of depression after the acute infectious process resolves. As originally described in the 19th century, Weil’s Disease is characterized by a triad of fever, jaundice, and splenomegaly. Current usage of the term “Weil’s Disease” refers to fever, jaundice, and renal failure and is often considered synonymous with severe leptospirosis.

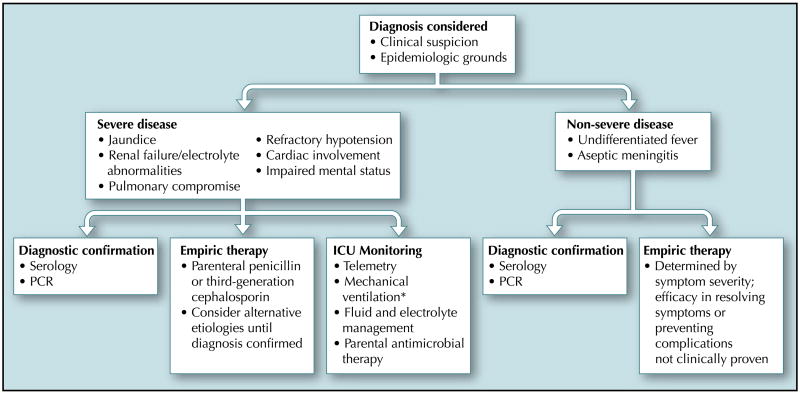

Classic descriptions of leptospirosis include two phases: a septicemic phase that lasts about a week, usually characterized by fever of sudden onset, chills, severe myalgia, anorexia, conjunctival suffusion, nausea, vomiting, and prostration. After a 3- to 4-day period of relative improvement, illness may recur in the so-called immune phase, when leptospires cannot be cultured from blood and antibiotic therapy does not appear to be useful. Many cases of severe leptospirosis do not conform to this classic description [4••,5,46]. Indeed, severe disease may present as a fulminant monophasic illness with fever progressing to jaundice, oliguric renal failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, refractory shock, and death within days [46] (Table 2). In such situations, which occur most often among people living in urban slums, a high index of suspicion is needed to initiate appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy and to institute supportive intensive care unit management (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Clinical features of leptospirosis associated with increased mortality risk

| Altered mental status |

| Respiratory insufficiency |

| Rales |

| Infiltrates |

| Hemoptysis |

| Oliguric hyperkalemic acute renal failure* |

| Cardiac involvement |

| Myocarditis |

| Arrhythmias (complete or incomplete) heart block atrial fibrillation |

Nonoliguric renal failure carries a better prognosis as long as electrolyte abnormalities are corrected.

Figure 1.

Clinical approach to the leptospirosis patient. Asterisk indicates the beneficial effect of inhaled nitric oxide when combined with hemofiltration anecdotal based on a single-case report [62]. ICU—intensive care unit; PCR—polymerase chain reaction.

Renal insufficiency is characteristic of severe leptospirosis and may manifest either as acute oliguric or non-oliguric renal failure. Several pathogenic mechanisms have been suggested to explain the injury to the kidney, most recently, direct inhibition of the Na/K adenosine triphosphatase in proximal renal tubular cells by surface-expressed leptospiral proteins [47], by nonesterified unsaturated fatty acid leptospiral cellular components [48], or by lipoprotein (LipL32)-induced production of inflammatory cytokines via NFκB-induced gene transcription [49]. These mechanisms could explain the Na+/K+ wasting defects and the incomplete tubular type II acidosis that has been reported, and the significant hypokalemia found in up to 40% in different series of patients [50]. Abnormalities of the urinary sediment are characteristic of acute leptospirosis, including proteinuria, pyuria, and hematuria, whether or not renal insufficiency is present.

Oliguric renal failure accompanied by hyperkalemia and serum creatinine more than 3 mg/dL is associated with a poor prognosis and usually indicates the need for renal replacement therapy with either peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. A recently published clinical trial of renal replacement therapy in acute infectious diseases in Vietnam, including malaria and leptospirosis, demonstrated that hemodialysis is preferable to peritoneal dialysis, with improved mortality rates. Complete recovery from renal failure is typical.

Less common forms of leptospirosis include isolated aseptic meningitis which is not known to lead to complications; myocardial involvement accompanied by various arrhythmias (bundle branch block, atrial fibrillation) and frank myocarditis which may be fatal particularly if heart failure occurs; cholecystitis; pancreatitis; and myositis resulting in rhabdomyolysis with attendant renal complications.

Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Leptospirosis

The severe pulmonary hemorrhagic form of leptospirosis (SPFL) has globally emerged as an important complication. An epidemic of leptospirosis in Nicaragua [2] brought pulmonary hemorrhage as a complication to international attention, although this manifestation had been previously well recognized to affect populations in leptospirosis-endemic regions, for example in the Andaman Islands [51]. Curiously, in the epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Salvador, Brazil, originally described by Ko et al. [52••], pulmonary hemorrhage was not observed. Given the detailed, comprehensive population surveillance carried out in this investigation, it is reasonable to conclude that SPFL was not prominent in Salvador in the early to mid-1990s. However, in other urban areas of Brazil, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, SPFL was first noted to emerge in the early 1990s and remains an important complication of leptospiral infection [46,53,54]. Recently, SPFL has also been observed to be emerging in Salvador as a complication of leptospirosis (Ko, personal communication).

In the highly endemic setting such as in the Peruvian Amazon, a population-based study has shown that pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis varies in severity, including a mild febrile illness with blood-streaked sputum, massive intra-alveolar hemorrhage, and nonhemorrhagic acute respiratory distress syndrome [4••]. Neither jaundice nor renal failure is invariably present in patients with pulmonary disease as has been shown in diverse regions such as the Andaman Islands, Nicaragua and Peru. It remains unknown whether SPFL results from specific virulence properties of Leptospira, or whether genetic predisposition leads to SPFL or other forms of severe leptospirosis. Recent evidence from animal models is mixed regarding the roles of acquired T- or B-cell immunity and complement in the pathogenesis of SPFL [55,56]. Human population studies will be necessary to delineate host and bacterial factors predisposing to severe leptospirosis. Understanding the mechanisms of SPFL in humans is key to developing adjunctive support measures for the clinical management of severe pulmonary leptospirosis.

Approach to the Patient

The key step in managing the patient with leptospirosis is considering the diagnosis. Leptospirosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when suggested by an appropriate exposure or travel history accompanied by an unusual undifferentiated febrile illness (ie, “a flu-like” illness without the typical upper respiratory symptoms of influenza or other respiratory viruses), or the highly suggestive combination of fever, jaundice, and renal insufficiency with an active urinary sediment and transminases in the range of low- to mid-100s IU/mL. Other diseases typically considered in mild leptospirosis include influenza (based on the combination of fever and myalgia), rickettsial diseases (in California, Texas, and Hawaii, murine typhus should be considered; in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, scrub typhus), and malaria (in returnees from malaria-endemic regions). Severe leptospirosis, especially when accompanied by hemorrhage, prompts consideration of viral hemorrhagic fever syndromes, especially those caused by hantaviruses, arenaviruses, flaviviruses such as dengue virus and yellow fever virus, and sepsis accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation (including melioidosis in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, which requires ceftazidime treatment and does not respond to penicillin or ceftriaxone). Once the diagnosis of leptospirosis is considered, consideration must be given to empiric antibiotic treatment because definitive diagnostic data are rarely available quickly. Because of variability among cases, routine hematologic (complete blood counts), chemistry (renal and liver function), and urinalysis data are not definitive in the diagnosis of leptospirosis. Patients should be stratified into those who can be safely observed without treatment, those in whom empiric oral therapy is appropriate, and those who require hospital admission and empiric parenteral antibiotic therapy along with general supportive measures (Table 2).

Treatment

Whether penicillin treatment was effective in severe leptospirosis arose in the 1980s when two clinical trials came to opposite conclusions [57,58,59]. However, most clinicians familiar with leptospirosis would empirically treat suspected cases of severe leptospirosis with antibiotics [19••] (Table 3); this approach is supported by a recent clinical trial in which intravenous ceftriaxone was found to be equivalent to intravenous penicillin in the treatment of severe leptospirosis in northern Thailand [60••]. However, given the lack of formal double-blinded, randomized clinical trials, the efficacy of antimicrobials in severe leptospirosis remains less than certain, particularly with relation to the stage of disease at which therapy is initiated. The efficacy of antibiotics in treating nonsevere leptospirosis is unknown, and difficult to test. Acute leptospirosis usually resolves spontaneously. Clinical indicators of progression from undifferentiated fever to severe disease are unknown. Rapid diagnosis remains difficult. Finally, fever is common enough among people in tropical settings that patients may not seek treatment until severe symptoms occur.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial treatment and prevention of leptospirosis

| Treatment of severe leptospirosis |

| Penicillin 1.5 million units IV or IM every 6 h for 5–7 days |

| Ceftriaxone 1 g/d IV for 7 days |

| Treatment of nonsevere leptospirosis |

| Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 5–7 days |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg orally three times daily for 5–7 days |

| Prevention of leptospirosis |

| Doxycycline 100 mg orally every day or 200 mg orally every week |

IM—intramuscular; IV—intravenous.

In vitro studies have shown that Leptospira is susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics. In one study, cefepime, imipenem-cilastatin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, and telithromycin had MIC90 less than 0.01 μg/mL in more than 90% of isolates, whereas amoxicillin, aztreonam, cefdinir, chloramphenicol, and penicillin had MIC90s of greater than 3.13 μg/mL. There was no clear relationship between in vitro killing and in vivo efficacy [61].

The efficacy of adjunct therapies such as nitric oxide [62], plasma exchange [63,64], and corticosteroids has been anecdotally noted in isolated case reports but larger trials have not been confirmed their efficacy.

Prevention of Leptospirosis: Public Health Efforts, Chemoprophylaxis, and Vaccine Development

Efforts to prevent contamination of environmental water sources are key to the control of leptospirosis at the level of public health. The major reservoirs of Leptospira include rats and dogs in cities, and livestock, wild rodents, and opossums in suburban and rural areas. Leptospiral infection of peridomestic rats is common in urban environments, such as Detroit and Baltimore in the United States, or tropical urban slums. Rat eradication programs are generally of low priority to government officials, leading to increased rat populations and the probability of increased transmission to humans. Control measures aimed at vaccination of reservoir hosts are unlikely to be carried out in developing countries, and, in any event, do not prevent leptospiruria in vaccinated animals [65,66]. Public health efforts associated with remediation of urban blight will likely be associated with decreased risk in urban areas, for example better trash removal in slum areas, rat eradication, etc. Placement of livestock ranches away from rivers and creeks would help in preventing contamination of suburban and rural water sources. Flooding in other regions (such as Brazil, India, Nicaragua, Andaman Islands) has been strongly associated with leptospirosis transmission [51], likely by mobilizing leptospires from ground sources into flowing water where people walk and swim [2,45,67,68]. Whether leptospirosis will emerge as an important disease in the recent hurricane-associated flooding along the Gulf Coast remains to be seen. Leptospirosis was not seen after the tsunami in Southeast Asia, probably due to salt water contamination of fresh water sources.

Chemoprophylaxis is the primary approach to preventing leptospirosis among people who have a strong likelihood of exposure, either occupational or through water-related athletic events. A classic study showed that weekly doxycycline prevented leptospirosis in previously naïve soldiers undergoing jungle training in Panama [69]. Such findings were not replicated in an endemic setting in the Andaman Islands where exposure is likely ubiquitous in the course of activities of daily living [70]. As noted in the analysis of the Eco-Challenge leptospirosis outbreak, doxycycline was shown to be protective from symptomatic leptospirosis in athletes swimming in a hot zone of transmission [10,41]. It is reasonable to conclude that daily doxycycline (100 mg/d) would be a useful recommendation to adventure travelers likely to undergo immersion in fresh water in leptospirosis endemic regions. Whether this finding applies to situations such as populations exposed after natural disasters such as floods still remains to be shown.

There is no widely approved human vaccine for leptospirosis. Vaccines (bacterins comprised of formalin-killed pathogenic leptospires) are available for veterinary use, for example, for dogs and cattle. Not all important serovars are included in the canine vaccine, so that serovars such as Grippotyphosa (reservoir primarily opossums) have emerged recently as important infections of dogs [71]; such emerging serovars would place humans at risk for infection. Even vaccinated dogs may be sources of human infection [65], because they can develop leptospiruria in the absence of clinical disease. Bacterin-based vaccines have been tested recently primarily in Cuba and China [72,73] but have not been licensed nor tested in other countries. These vaccines are likely to have unacceptable side effects and variable, probably short-term, efficacy against limited numbers of serovars, thus precluding wide dissemination.

Conclusions

Leptospirosis is a globally important zoonotic infectious disease. Difficulty in diagnosis makes timely treatment difficult so that empiric antibiotic therapy is usually necessary. This disease has emerged as an important clinical problem in adventure travelers. Severe leptospirosis as manifested by a combination of jaundice, renal failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, and refractory shock in the tropical setting is an emerging and expanding problem. Treatment is required for severe disease, with a recent open-label clinical trial showing ceftriaxone and parenteral penicillin to have equivalent efficacy. Adjunctive therapies aimed at secondary pathogenetic events in severe leptospirosis have yet to be developed. A protective vaccine for humans is not yet available.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by United States Public Health Grants RO1TW/ES05860 and D43TW007120.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Yersin C, Bovet P, Merien F, et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage as a predominant cause of death in leptospirosis in Seychelles. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trevejo RT, Rigau-Perez JG, Ashford DA, et al. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage-Nicaragua, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1457–1463. doi: 10.1086/314424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marotto PC, Nascimento CM, Eluf-Neto J, et al. Acute lung injury in leptospirosis: clinical and laboratory features, outcome, and factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1561–1563. doi: 10.1086/313501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Segura E, Ganoza C, Campos K, et al. Clinical spectrum of pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis in an endemic region, with quantification of leptospiral burden. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:343–351. doi: 10.1086/427110. This population-based study demonstrated the urban association of severe disease in the tropical setting and delineated a spectrum of pulmonary manifestations in severe disease. A higher leptospiral burden, quantified using a real-time PCR assay, was associated with poor outcome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinetz JM, Glass GE, Flexner CE, et al. Sporadic urban leptospirosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:794–798. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiermann AB, Frank RR. Human leptospirosis in Detroit and the role of rats as chronic carriers. Int J Zoonoses. 1980;7:62–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehgal SC, Vijayachari P, Murhekar MV, et al. Leptospiral infection among primitive tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:423–428. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Vijayachari V, Sugunan AP, Murhekar MV, et al. Leptospirosis among schoolchildren of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India: low levels of morbidity and mortality among pre-exposed children during an epidemic. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:1115–1120. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002948. This paper is among the first to demonstrate, on a population level, that protective immunity develops in humans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of leptospirosis among white-water rafters—Costa Rica, 1996. MMWR Mor Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:577–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sejvar J, Bancroft E, Winthrop K, et al. Leptospirosis in Eco-Challenge athletes, Malaysian Borneo, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:702–707. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Creel R, Speelman P, Gravekamp C, Terpstra WJ. Leptospirosis in travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:132–134. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kager PA, van Gorp EC, van Thiel PP. Fever and chills due to leptospirosis after travel to Thailand. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2001;145:184–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olszyna DP, Jaspars R, Speelman P, et al. Leptospirosis in the Netherlands, 1991–1995. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1998;142:1270–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell KL, Montiel Gonzalez MA, et al. An outbreak of leptospirosis among Peruvian military recruits. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders L. Diagnosis. The New York Times Magazine. 2005 April 24;6:35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torten M, Marshell RB. Leptospirosis. In: Beran GW, Steele JH, editors. Handbook of Zoonoses, edn 2. Section A: Bacterial, Rickettsial, Chlamydial and Mycotic Zoonoses. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and Leptospirosis. 2. Melbourne: Medisci; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, et al. Leptospirosis: A zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.McBride AJ, Athanazio DA, Reis MG, Ko AI. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:376–386. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000178824.05715.2c. This is the most up-to-date review of leptospirosis from the basic research point of view. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer MF, Zochowski WJ. Survival of leptospires in commercial blood culture systems revisited. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:713–714. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.9.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandrasekaran S, Krishnaveni S, Chandrasekaran N. Darkfield microscopic (DFM) and serologic evidences for leptospiral infection in panuveitis cases. Indian J Med Sci. 1998;52:294–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijayachari P, Sugunan AP, Umapathi T, Sehgal SC. Evaluation of darkground microscopy as a rapid diagnostic procedure in leptospirosis. Indian J Med Res. 2001;114:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelman SS, Gundlapalli AV, Hale D, et al. Spotting the spirochete: rapid diagnosis of leptospirosis in two returned travelers. J Travel Med. 2002;9:165–167. doi: 10.2310/7060.2002.23165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao PS, Shashibhushan Shivananda PG. Comparison of darkground microscopy with serological tests in the diagnosis of leptospirosis with hepatorenal involvement —A preliminary study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1998;41:427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levett PN. Leptospira and Leptonema. In: Murray PR, editor. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2003. pp. 929–936. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuo K, Isogai E, Araki Y. Occurrence of [--> 3)-beta-D-Manp-(1 --> 4)-beta-D-Manp-(1 -->]n units in the antigenic polysaccharides from Leptospira biflexa serovar patoc strain Patoc I. Carbohydr Res. 2000;328:517–524. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terpstra WJ, Ligthart GS, Schoone GJ. ELISA for the detection of specific IgM and IgG in human leptospirosis. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:377–385. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-2-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Effler PV, Domen HY, Bragg SL, et al. Evaluation of the indirect hemagglutination assay for diagnosis of acute leptospirosis in Hawaii. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1081–1084. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1081-1084.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Bajani MD, Ashford DA, Bragg SL, et al. Evaluation of four commercially available rapid serologic tests for diagnosis of leptospirosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:803–809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.803-809.2003. This paper comprehensively compares the sensitivity and specificity of the most recent solid phase assays for the diagnosis of leptospirosis. It may not be applicable to the diagnosis of leptospirosis in the endemic setting where leptospirosis is very common. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smits HL, Hartskeerl RA, Terpstra WJ. International multi-centre evaluation of a dipstick assay for human leptospirosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:124–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smits HL, van der Hoorn MA, Goris MG, et al. Simple latex agglutination assay for rapid serodiagnosis of human leptospirosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1272–1275. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1272-1275.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatta M, Smits HL, Gussenhoven GC, Gooskens J. Introduction of a rapid dipstick assay for the detection of Leptospira- specific immunoglobulin m antibodies in the laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis in a hospital in Makassar, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:515–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smits HL, Chee HD, Eapen CK, et al. Latex based, rapid and easy assay for human leptospirosis in a single test format. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:114–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smits HL, Eapen CK, Sugathan S, et al. Lateral-flow assay for rapid serodiagnosis of human leptospirosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:166–169. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.1.166-169.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levett PN, Branch SL. Evaluation of two enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay methods for detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies in acute leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:745–748. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merien F, Baranton G, Perolat P. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction with microagglutination test and culture for diagnosis of leptospirosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:281–285. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truccolo J, Serais O, Merien F, Perolat P. Following the course of human leptospirosis: evidence of a critical threshold for the vital prognosis using a quantitative PCR assay. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;204:317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merien F, Portnoi D, Bourhy P, et al. A rapid and quantitative method for the detection of Leptospira species in human leptospirosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;249:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suwimonteerabutr J, Chaicumpa W, Saengjaruk P, et al. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody-based dot-blot ELISA for detection of Leptospira spp in bovine urine samples. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66:762–766. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saengjaruk P, Chaicumpa W, Watt G, et al. Diagnosis of human leptospirosis by monoclonal antibody-based antigen detection in urine. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:480–489. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.480-489.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haake DA, Dundoo M, Cader R, et al. Leptospirosis, water sports, and chemoprophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e40–43. doi: 10.1086/339942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreak of acute febrile illness among athletes participating in Eco-Challenge-Sabah 2000—Borneo, Malaysia, 2000. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan J, Bornstein SL, Karpati AM, et al. Outbreak of leptospirosis among triathlon participants and community residents in Springfield, Illinois, 1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1593–1599. doi: 10.1086/340615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashford DA, Kaiser RM, Spiegel RA, et al. Asymptomatic infection and risk factors for leptospirosis in Nicaragua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rathinam SR, Rathnam S, Selvaraj S, et al. Uveitis associated with an epidemic outbreak of leptospirosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spichler A, Moock M, Chapola EG, Vinetz JM. Weil’s Disease: an unusually fulminant presentation characterized by pulmonary hemorrhage and shock. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;9:336–340. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702005000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu MS, Yang CW, Pan MJ, et al. Reduced renal Na+-K+-Cl- co-transporter activity and inhibited NKCC2 mRNA expression by Leptospira shermani: from bed-side to bench. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burth P, Younes-Ibrahim M, Santos MC, et al. Role of nonesterified unsaturated fatty acids in the pathophysiological processes of leptospiral infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:51–57. doi: 10.1086/426455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang CW, Wu MS, Pan MJ, et al. Leptospira outer membrane protein activates NF-kappaB and downstream genes expressed in medullary thick ascending limb cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:2017–2026. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Covic A, Goldsmith DJ, Gusbeth-Tatomir P, et al. A retrospective 5-year study in Moldova of acute renal failure due to leptospirosis: 58 cases and a review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1128–1134. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sehgal SC, Murhekar MV, Sugunan AP. Outbreak of leptospirosis with pulmonary involvement in north Andaman. Indian J Med Res. 1995;102:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Ko AI, Galvao Reis M, Ribeiro Dourado CM, et al. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)80012-9. This paper is an important advance in our epidemiologic understanding of leptospirosis in the tropical urban setting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goncalves AJ, de Carvalho JE, Guedes e Silva JB, et al. Hemoptysis and the adult respiratory distress syndrome as the causes of death in leptospirosis. Changes in the clinical and anatomicopathological patterns (in Portuguese) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1992;25:261–270. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821992000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva JJ, Dalston MO, Carvalho JE, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of the severe pulmonary form of leptospirosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35:395–399. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nally JE, Chantranuwat C, Wu XY, et al. Alveolar septal deposition of immunoglobulin and complement parallels pulmonary hemorrhage in a guinea pig model of severe pulmonary leptospirosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nally JE, Fishbein MC, Blanco DR, Lovett MA. Lethal infection of C3H/HeJ and C3H/SCID mice with an isolate of Leptospira interrogans serovar copenhageni. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7014–7017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.7014-7017.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watt G, Padre LP, Tuazon ML, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of intravenous penicillin for severe and late leptospirosis. Lancet. 1988;1:433–435. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards CH, Nicholson GD, Hassell TA, et al. Penicillin therapy in icteric leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:388–390. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinetz JM. A mountain out of a molehill: Do we treat acute leptospirosis and, if so, with what? Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1514–1515. doi: 10.1086/375275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60••.Panaphut T, Domrongkitchaiporn S, Thinkamrop B. Prognostic factors of death in leptospirosis: a prospective cohort study in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6:52–59. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(02)90137-2. Despite being an open-label study, this paper validates the use of ceftriaxone in the treatment of severe leptospirosis and provides solid evidence that antibiotic therapy is required for severe leptospirosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murray CK, Hospenthal DR. Determination of susceptibilities of 26 Leptospira sp serovars to 24 antimicrobial agents by a broth microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4002–4005. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.4002-4005.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borer A, Metz I, Gilad J, et al. Massive pulmonary haemorrhage caused by leptospirosis successfully treated with nitric oxide inhalation and haemofiltration. J Infect. 1999;38:42–45. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(99)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Siriwanij T, Suttinont C, Tantawichien T, et al. Haemodynamics in leptospirosis: effects of plasmapheresis and continuous venovenous haemofiltration. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tse KC, Yip PS, Hui KM, et al. Potential benefit of plasma exchange in treatment of severe icteric leptospirosis complicated by acute renal failure. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:482–484. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.482-484.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feigin RD, Lobes LA, Anderson D, Pickering L. Human leptospirosis from immunized dogs. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:777–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-6-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talpada MD, Garvey N, Sprowls R, et al. Prevalence of Leptospiral infection in Texas cattle: implications for transmission to humans. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2003;3:141–147. doi: 10.1089/153036603768395843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barcellos C, Sabroza PC. The place behind the case: leptospirosis risks and associated environmental conditions in a flood-related outbreak in Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17(Suppl):59–67. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000700014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vanasco NB, Fusco S, Zanuttini JC, et al. Outbreak of human leptospirosis after a flood in Reconquista, Santa Fe, 1998. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2002;34:124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takafuji ET, Kirkpatrick JW, Miller RN, et al. An efficacy trial of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis against leptospirosis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:497–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198402233100805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sehgal SC, Sugunan AP, Murhekar MV, et al. Randomized controlled trial of doxycycline prophylaxis against leptospirosis in an endemic area. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;13:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Langston CE, Heuter KJ. Leptospirosis. A re-emerging zoonotic disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33:791–807. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(03)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martinez Sanchez R, Perez Sierra A, Baro Suarez M, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a new vaccine against human leptospirosis in groups at risk. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2000;8:385–392. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892000001100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yan Y, Chen Y, Liou W, et al. An evaluation of the serological and epidemiological effects of the outer envelope vaccine to leptospira. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003;66:224–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]