Abstract

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis (TBA) is a rare disease. No general consensus exists with regard to its optimal treatment, resulting in a variety of modalities used to manage this condition. In this article, we present a case of TBA treated with external beam radiation therapy with encouraging results. A brief literature review of this rare ailment is also included.

Introduction

Primary amyloidosis involving the tracheobronchial tree is rare.[1,2] It represents a localized variant of amyloidosis and is characterized by multifocal amyloid deposition within the airway walls with subsequent formation of submucosal plaques or polypoid nodules. The clinical presentation of this disease is often nonspecific, with symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, hoarseness, and stridor.[2] Pulmonary function tests typically reveal an obstructive pattern but may be normal when the disease is confined to the distal airways.[3] Chest x-rays are frequently unremarkable, often culminating in a delay of diagnosis. In most cases, the identification of this disease is made by means of bronchoscopy and biopsy of the airway mucosa.[4] Management of this disease often aims at maintaining patent airways. Localized treatment techniques such as bronchoscopic resection of disease and stenting have been described in current literature. However, these modalities often offer only a temporary solution as the disease usually recurs and progresses. The use of radiation therapy has been scarcely reported in the management of this rare condition.

Case Report

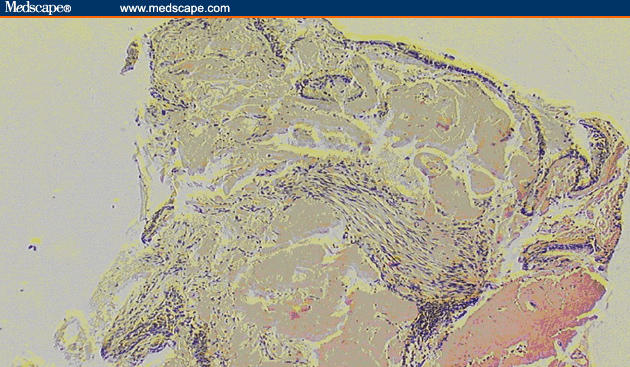

A 73-year-old woman with tracheobronchial amyloidosis (TBA) was referred for consideration of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). She was diagnosed more than 20 years previously when she was referred with a persistent collapse of the lingula and a background history of chronic obstructive airways disease. Her primary symptom at that point was dyspnea. Bronchoscopy revealed an obstructive lesion at the orifice of the lingula. Biopsy and Congo red staining revealed abundant submucosal amorphous pinkish material consistent with amyloid deposits (Figure 1). Serum and urine protein electrophoresis as well as an echocardiogram were normal. In view of the isolated amyloid involvement to the pulmonary tree, a diagnosis of primary TBA was made.

Figure 1.

Biopsy indicating amyloid deposition in the bronchial wall lamina propria below the mucosal surface. (100× magnification)

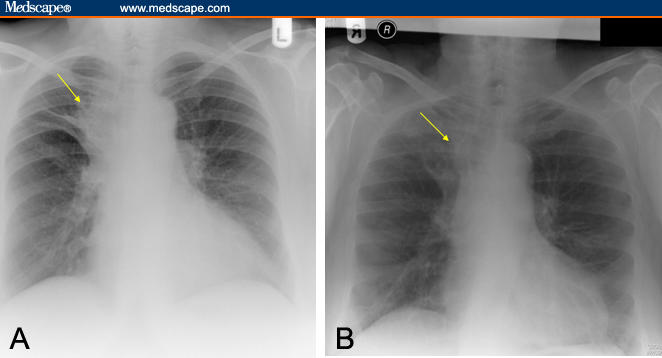

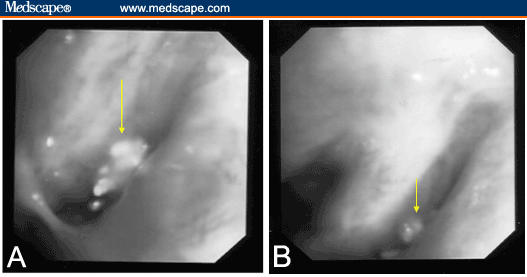

Over the next few years, she had repeated bronchoscopic procedures to relieve her airways obstruction secondary to her amyloidosis and remained quite well. However, 20 years after the original diagnosis, she had progressive breathlessness associated with a new right upper lobe partial collapse (Figure 2A). A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a narrowing of the right upper lobe orifice with distal collapse. At bronchoscopy she had severe narrowing of the anterior segment of the right upper lobe bronchus (Figure 3A). Biopsies and brushings were performed and histology confirmed this to be amyloid disease.

Figure 2.

Chest x-ray depicting (A) partial right upper lobe collapse, (B) with subsequent resolution after radiation therapy.

Figure 3.

Bronchoscopic pictures depicting (A) mass at right upper lobe airway, (B) with subsequent improvement after radiation therapy.

She then underwent repeated bronchoscopies to relieve the obstruction but with limited success. Her case was subsequently discussed at the multidisciplinary meeting and it was felt that EBRT was an appropriate treatment option. Radiation therapy was discussed in detail with the patient because of the scarcity of clinical evidence regarding its use for amyloid disease. She received EBRT, 24 Gy in 12 fractions using 6 MV photons over 2 1/2 weeks. Opposed anterior-posterior and posterior-anterior treatment fields were used to encompass the entire tracheobronchial tree. The treatment volume was determined using CT-guided simulation. Treatment was uneventful apart from worsening dyspnea toward the end of her treatment. This was successfully treated with oral corticosteroids.

She had a repeat bronchoscopy after radiation therapy that revealed a partial response to treatment (Figure 3B). Clinically, her symptoms continued to improve over the next few months. Repeat evaluation by means of chest x-ray at 9 months after radiation therapy revealed response to radiation therapy was maintained, with no evidence of disease progression (Figure 2B).

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to a disease spectrum that is characterized by abnormal extracellular deposition of amyloid and autologous fibrillar protein material, most often derived from immunoglobulin light chains.[4,5] Diagnosis is made by means of biopsy, which shows green bifringence of Congo red-stained deposits when viewed under polarized light.[2,5] Amyloidosis usually occurs as a multiorgan disease. Localized amyloid deposition affecting single organs such as the kidney, bladder, or respiratory tract is uncommon but has been documented in the literature.[4]

Amyloidosis of the respiratory tract has 3 different subtypes: focal or diffuse TBA, nodular parenchymal, and diffuse parenchymal amyloidosis.[3,6] Among these 3 entities, TBA is comparatively the most common subtype and occurs almost invariably in the absence of systemic amyloidosis.[4] TBA is more prevalent in males, with a median age of onset in the fifth and sixth decade.[4] The respiratory symptoms associated with this condition are nonspecific but are related to the anatomic site of involvement, so that patients with proximal disease tend to have upper airways obstruction, and those with distal disease have lobar collapse and recurrent infections.[4]

Investigations performed in the workup of patients with TBA serve 2 functions: (1) to characterize the site and extent of the local disease and (2) to exclude the presence of systemic disease. Chest x-rays are often normal but occasionally may show atelectasis caused by obstructing lesions.[3] CT imaging provides better anatomic delineation of disease extent by revealing the degree of soft tissue thickening and calcification of the airway wall and narrowing of the lumen.[4] However, other conditions can have similar radiologic characteristics, including tracheobronchial osteochondroplastica, chronic tracheobronchilitis, and relapsing polychondritis, highlighting the value of tissue sampling for definitive diagnosis.[5] Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and echocardiography are performed to rule out systemic involvement of amyloidosis.

There is no established treatment for TBA. Review of the current literature shows that information about TBA is often limited to small case series or case reports. The treatment options, as gathered from published data, can be categorized into 3 not necessarily exclusive groups: (1) bronchoscopic recanalization techniques, (2) pharmacologic treatments, and (3) the use of EBRT.

Most of the treatments described in TBA include bronchoscopic resections with a predictable improvement in symptoms. Flemming and coworkers[7] published a case report and Capizzi and colleagues[1] described a small case series that demonstrated improvement in symptoms following intermittent resection. Laser resection using CO2 and Nd:YAG has been reported to produce long periods of disease control.[3] Maitwand and coworkers[8] reported similar success with cryosurgery in a single patient. However, in most cases, repeated resections are required because the disease inevitably recurs and progresses, with worsening pulmonary function.[7,9,10] In addition, there is an inherent risk for bleeding with repeated resections.

Pharmacologic treatment with colchicine has been tried, although the evidence for its use is based on small noncontrolled trials that have suggested some benefit as adjuvant treatment in primary systemic amyloidosis.[11,12] Kurrus and associates[13] used colchicine with EBRT in one patient but were unable to determine whether it was synergistic with radiation therapy.[13] Success with intermittent chemotherapy using melphalan and prednisolone following repeated laser resections has been shown in a case report by Sharma and coworkers.[14] Steroids also have been used in conjunction with all treatment modalities.

The successful use of radiation therapy for the treatment of TBA was first described by Kurrus and colleagues[13] as a case report in 1998. A patient with life-threatening airway obstruction secondary to TBA received 20 Gy in 10 fractions to the distal trachea and right main bronchus; this was repeated 6 months later to the lower lobe bronchus because of disease progression. In both treated areas the patient responded radiologically and symptomatically.[13] Kalra and colleagues[15] also described the benefits of radiation therapy in airway obstruction at a dose similar to that used by Kurrus and associates. Benefit was maintained 21 months after radiation therapy. Munroe and coworkers[2] used a higher dose of radiation, 24 Gy in 12 fractions, in a single case, and 18 months posttreatment there was demonstrable improvement in pulmonary function, and improvement was shown on CT imaging and bronchoscopic visualization.

Radiation therapy has to be considered with caution because it can carry potential late complications that include esophageal injury, pericarditis, pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, and myelitis, despite the relatively moderate dose.[15] In our patient, the deterioration in respiratory function in the absence of effective alternative therapies justified the use of radiation. Although use of radiation therapy in TBA has been successful in case reports described by Kurrus and coworkers,[13] Kalra and associates,[15] Munroe and colleagues,[2] and our group in this patient, the optimal dose of radiation remains undefined. The long-term effects of radiation therapy for TBA are still unknown, and close follow-up to detect late complications is required.

Overall, TBA remains a rare and technically challenging condition to treat. The treatment of this disease needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and managed within an appropriate multidisciplinary team.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Tracheobronchial Amyloidosis: Utilization of Radiotherapy As a Treatment Modality See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at spoovan@doctors.net.uk or to George Lundberg, MD, Editor in Chief of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Contributor Information

Sangeetha Poovaneswaran, Newcastle General Hospital, United Kingdom Author's email: spoovan@doctors.net.uk.

Albiruni Ryan Abdul Razak, Newcastle General Hospital, United Kingdom.

Hilmi Lockman, South Tyneside Hospital, United Kingdom.

Michael Bone, South Tyneside Hospital, United Kingdom.

Kenneth Pollard, South Tyneside Hospital, United Kingdom.

Goudarz Mazdai, Newcastle General Hospital, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Capizzi SA, Betancourt E, Prakash UB. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2000;75:1148–1152. doi: 10.4065/75.11.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munroe AT, Walia R, Zlotecki RA, Jantz MA. A case report of successful treatment with external beam radiation therapy. Chest. 2004;125:784–789. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Regan A, Fenlon HM, Beamis JF, Jr, et al. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis. The Boston University experience from 1984 to 1999. Medicine. 2000;79:69–79. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbaoui H, Abouchacra S, Yaman M. A case of primary diffuse tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1832–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozer C, Nass Duce M, Yildiz A, apaydin FD, Eqilmez H, Arpaci T. Primary diffuse tracheobronchial amyloidosis: case report. Eur J Radiol. 2002;44:37–39. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00437-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HY, Im JG, Song KS. Localized amyloidosis of the respiratory system: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:627–631. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199907000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flemming AF, Fairfax AJ, Arnold AG, Lane DJ. Treatment of endobronchial amyloidosis by intermittent bronchoscopic resection. Br J Dis Chest. 1980;74:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(80)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maitwand MO, Nath AR, Kamath BSK. Cryosurgery in the treatment of tracheobronchial amyloidosis. J Bronchol. 2001;8:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumon JF. A dedicated tracheobronchial stent. Chest. 1990;97:328–332. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millar AB, O'Reilly AP, Clarke SW, Hetzel MR. Amyloidosis of the respiratory tract treated by laser therapy. Thorax. 1985;40:544–545. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.7.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen AS, Rubinow A, Anderson JJ, et al. Survival of patients with primary (AL) amyloidosis: colchicine-treated cases from 1976 to 1983 compared with cases seen in previous years (1961 to 1973) Am J Med. 1987;82:1182–1190. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson MD. Treatment of amyloidosis with melphalan, prednisolone, and colchicines. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:683–687. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurrus JA, Hayes JK, Hoidal JR, Menendez MM, Elstad MR. Radiation therapy for tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Chest. 1998;114:1189–1192. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.5.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma SK, Ahluwalia G, Ahluwalia A, Mukhopadhyay S. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis masquerading as bronchial asthma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004;46:117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalra S, Utz JP, Edell ES, Foote RL. External beam radiation therapy in the treatment of diffuse tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:853–856. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]