Abstract

Membrane-bound phosphoinositides are signalling molecules that have a key role in vesicle trafficking in eukaryotic cells1. Proteins that bind specific phosphoinositides mediate interactions between membrane-bounded compartments whose identity is partially encoded by cytoplasmic phospholipid tags. Little is known about the localization and regulation of mammalian phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(3,5)P2), a phospholipid present in small quantities that regulates membrane trafficking in the endosome–lysosome axis in yeast2. Here we describe a multi-organ disorder with neuronal degeneration in the central nervous system, peripheral neuronopathy and diluted pigmentation in the ‘pale tremor’ mouse. Positional cloning identified insertion of ETn2β (early transposon 2β)3 into intron 18 of Fig4 (A530089I17Rik), the homologue of a yeast SAC (suppressor of actin) domain PtdIns(3,5)P2 5-phosphatase located in the vacuolar membrane. The abnormal concentration of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in cultured fibroblasts from pale tremor mice demonstrates the conserved biochemical function of mammalian Fig4. The cytoplasm of fibroblasts from pale tremor mice is filled with large vacuoles that are immunoreactive for LAMP-2 (lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2), consistent with dysfunction of the late endosome–lysosome axis. Neonatal neurodegeneration in sensory and autonomic ganglia is followed by loss of neurons from layers four and five of the cortex, deep cerebellar nuclei and other localized brain regions. The sciatic nerve exhibits reduced numbers of large-diameter myelinated axons, slowed nerve conduction velocity and reduced amplitude of compound muscle action potentials. We identified pathogenic mutations of human FIG4 (KIAA0274) on chromosome 6q21 in four unrelated patients with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. This novel form of autosomal recessive Charcot–Marie–Tooth disorder is designated CMT4J.

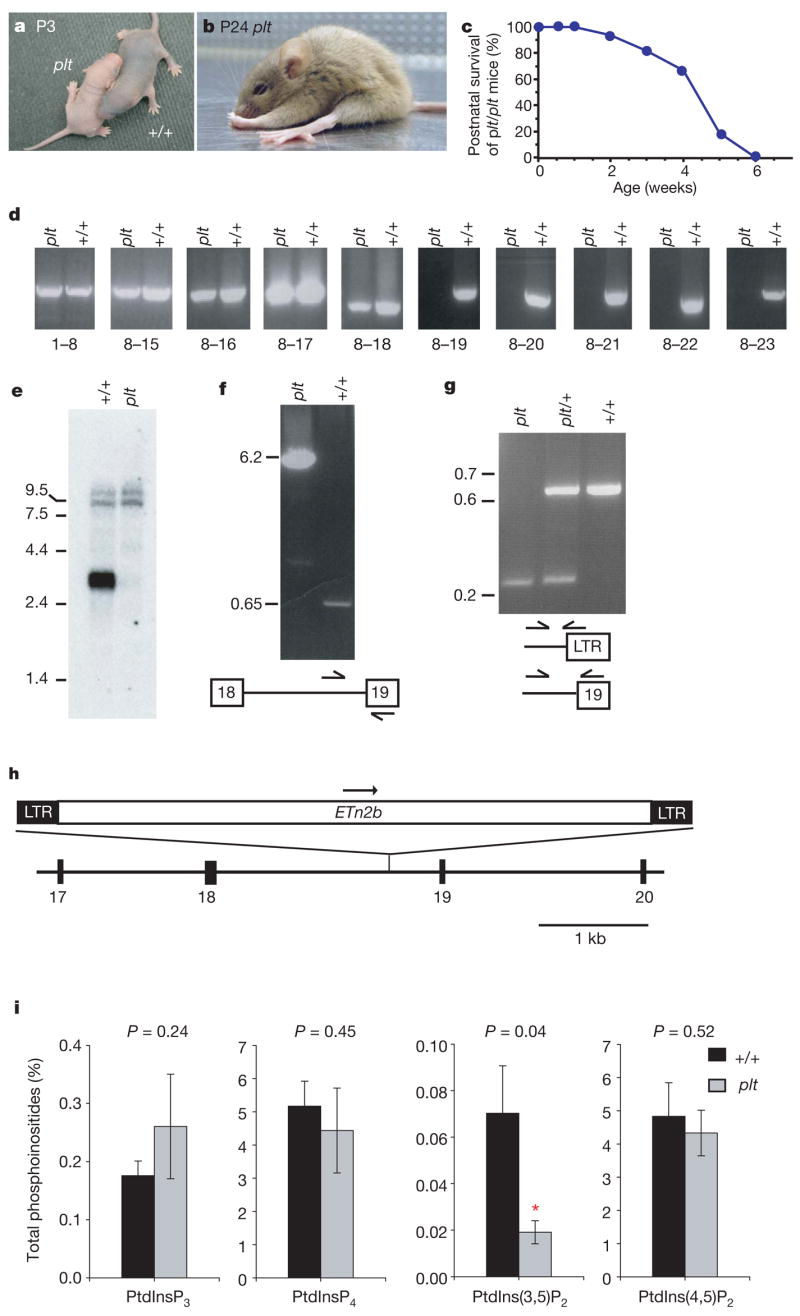

Mutant mice with severe tremor, abnormal gait and diluted pigmentation were identified in our mouse colony on a mixed inbred strain background. One breeding pair generated 8/30 affected progeny, consistent with inheritance of an autosomal recessive mutation designated ‘pale tremor’. At postnatal day three (P3), affected homozygotes have diluted pigmentation and reduced size (Fig. 1a). Intentional tremor develops during the second week after birth, and abnormal limb postures are evident by the third week (Fig. 1b). The impaired motor coordination, muscle weakness and ‘swimming’ gait of pale tremor mice are demonstrated in the Supplementary Movie. There is progressive loss of mobility, reduction in body weight and juvenile lethality (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Phenotypes of homozygous pale tremor mice.

a, Diluted pigmentation of the pale tremor mouse (plt) compared with the wild-type (+/+) mouse. b, Abnormal limb postures. c, Juvenile lethality of F2 mice from the CAST/Ei cross (n = 50). d, RT–PCR of Fig4 transcript from brain with primers in indicated exons. e, Northern blot containing 3 mg of brain polyA+RNA, isolated at P7 before extensive neurodegeneration, using a 1 kb Fig4 cDNA probe (exons 8–15). RNA integrity and equal loading of samples is indicated by the intensity of minor bands (9–10 kb). f, Long-range PCR of genomic DNA with primers in intron 18 and exon 19. g, Three-primer genotyping assay for Fig4 produces 646 bp wild-type and 245 bp Fig4paletremor products. LTR, long terminal repeat. Molecular weight markers in e–g are given in kb. h, ETn2β retrotransposon in intron 18 of Fig4. i, Altered abundance of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in cultured fibroblasts. *Significant difference at P <0.05. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 6).

To genetically map the pale tremor gene, a cross was carried out with strain CAST/Ei. The recovery of affected F2 offspring was 9% (50/532), indicative of prenatal loss on this genetic background. We genotyped 532 F2 animals with microsatellite and single nucleotide polymorphism markers to map the pale tremor gene to a 2-megabase interval of mouse chromosome 10 between D10Umi13 and D10Mit184 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). There are 21 annotated genes in the non-recombinant interval (http://www.ensembl.org; mouse build 35); these were tested as candidates by sequencing reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) products from brain RNA. The A530089I17Rik transcript amplified from pale tremor RNA lacks exons 19 to 23 from the 3′end of the gene (Fig. 1d). Hybridization of a polyA+ northern blot with a complementary DNA probe containing exons 8 to 15 identified a wild-type transcript of 3.3 kilobases (kb) that is not present in messenger RNA from pale tremor mice (Fig. 1e). No abnormal transcripts were detected in the mutant, even when the exposure time was increased from 3 to 63 h (not shown). We were able to amplify exons 19 to 23 from genomic DNA, eliminating the possibility of a genomic deletion (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

To identify the genomic mutation, we examined the structure of intron 18 using PCR. A wild-type product of 0.65 kb and a mutant product of 6.2 kb were amplified from the 3′ end of intron 18 (Fig. 1f). The sequence of the mutant product (GenBank DQ813648) contains a 5,547 base pair (bp) insert with 99% sequence identity to mouse retro-transposon ETn2β (GenBank Y17106). The transposon is inserted 384 bp upstream of exon 19, in the same orientation as the gene (Fig. 1h), and is flanked by a duplication of the hexanucleotide CCCCTG, characteristic of ETn2β insertions3. The mutant allele can be detected by PCR with a primer in the long terminalrepeat (Fig. 1g). The background strains do not contain the ETn2β element (data not shown), indicating that mutation of the pale tremor gene is a result of transposon insertion. The data are consistent with abnormal splicing from exon 18 of Fig4 to one of the cryptic splice acceptor sites in the ETn2β element3, generating a transcript of very low abundance that is detected by RT–PCR but is below the sensitivity of the polyA+ northern blot.

RT–PCR of tissues from wild-type mice demonstrated widespread expression of Fig4 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), consistent with public expressed-sequence-tag and microarray databases. In situ hybridization data demonstrate distribution of the transcript throughout the brain (http://www.brainatlas.org/aba/ and unpublished observations, C.Y.C. and M.H.M.). The human orthologue, KIAA0274, is located on human chromosome 6q21. The mutated protein is most closely related to the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAC-domain phosphatase Fig4, with overall amino acid sequence identity of 35% and similarity of 66%. The SAC domain with the active site motif CX5R(S/T) is characteristic of phosphatases with specificity for phosphoprotein or phospholipid substrates4, and exhibits 44% sequence identity (191/435 amino acids; Supplementary Fig. 1b). The four other mammalian genes with SAC domains (SYNJ1, SYNJ2, INPP5F and SAC1) differ from Fig4 at other domains4, indicating that mouse A530089I17Rik and human KIAA0274 are homologues of yeast Fig4.

Yeast Fig4 is localized to the vacuolar membrane and is required for both generation and turnover of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (ref. 5). Yeast Fig4 exhibits lipid phosphatase activity towards the 5-phosphate residue of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (ref. 6), and also appears to activate the Fab1 kinase that synthesizes PtdIns(3,5)P2 from phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, possibly by dephosphorylating the kinase or one of its regulators5. As a result, deletion of yeast Fig4 reduces rather than increases the intracellular concentration of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (ref. 7), leading to defects in vacuole fission, formation of enlarged vacuoles and impaired retrograde traffic to the late endosome2,8,9. Knockdown of mammalian Fab1/PIKfyve kinase causes a similar defect in retrograde endosome traffic and enlarged vacuoles10.

Analysis of phosphoinositides from cultured fibroblasts of pale tremor mice demonstrated a three-fold reduction in PtdIns(3,5)P2 (P = 0.04), with no change in three other phosphoinositides (Fig. 1i). Enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles accumulate in 40% of cultured fibroblasts from pale tremor mice (174/435) compared with 5% of wild-type cells (22/403) (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). These vacuoles stain positively for LAMP-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3e–g), indicating that they represent late-stage endosomes. The altered levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 demonstrate conserved enzymatic function of FIG4 from yeast to mouse, whereas the enlarged vacuoles demonstrate a conserved cellular role in regulation of the size of late endosomes.

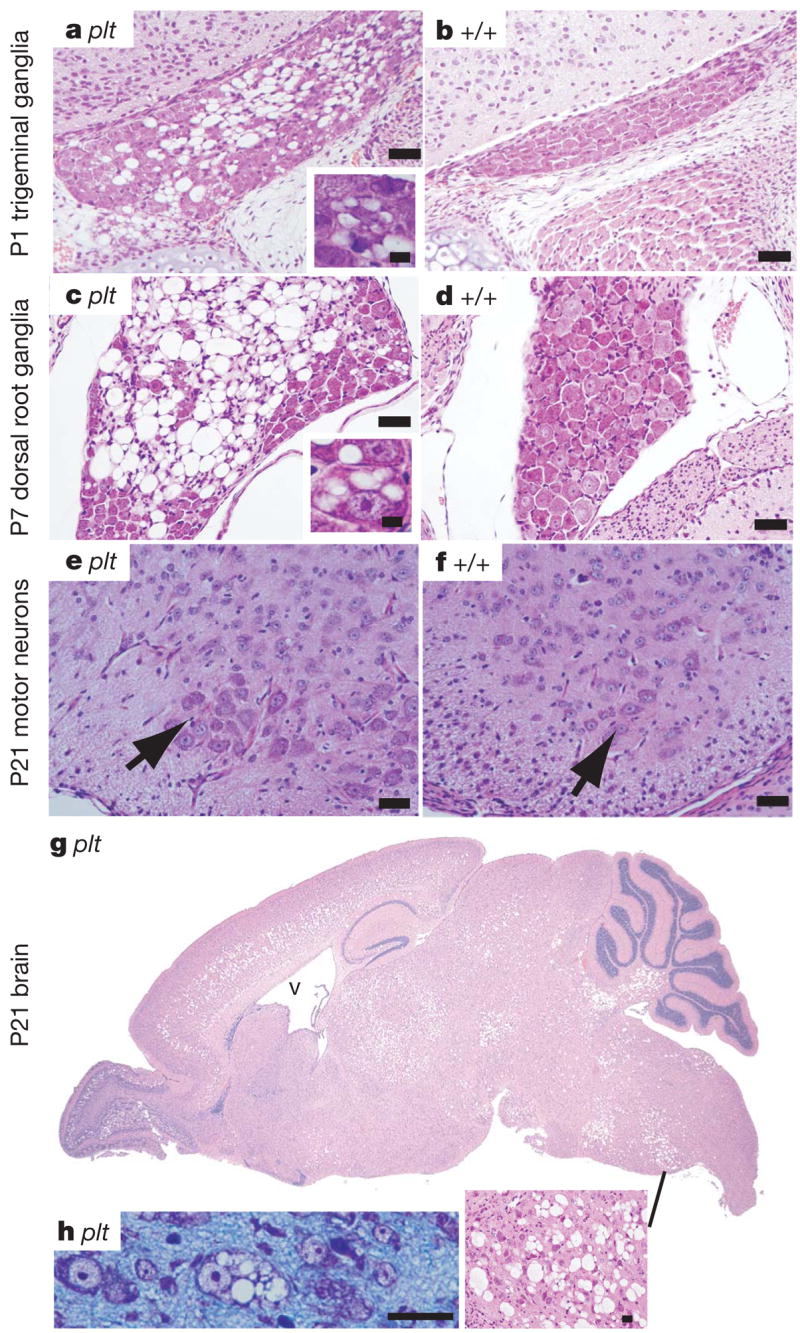

In vivo loss of FIG4 results in a striking pattern of selective neurodegeneration. Extensive loss of neurons from sensory and autonomic ganglia is evident during the neonatal period (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Fig. 4a). The presence of neurons with enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles suggests that vacuole accumulation precedes cell loss (Fig. 2, insets). Spinal motor neurons exhibit normal morphology at three weeks (Fig. 2e–f) but contain vacuoles at six weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 2. Neuropathology in pale tremor mice.

a, b, Trigeminal ganglia; c, d, dorsal root ganglia from lumbar region. Insets reveal cytoplasmic vacuoles. (Superior cervical ganglia have a similar appearance; see Supplementary Fig. 4a.) e, f, Spinal cord ventral horn. Arrow, motor neuron cell body. g, Sagittal section of the brain of a pale tremor mouse (for wild-type control lacking degeneration see Supplementary Fig. 6). V, enlarged ventricle. h, Neuronal cell bodies from regions of degeneration in P7 brain. Scale bars: a–f, 25 mm; insets in a and c, 12.5 mm; panel h, 25 μm.

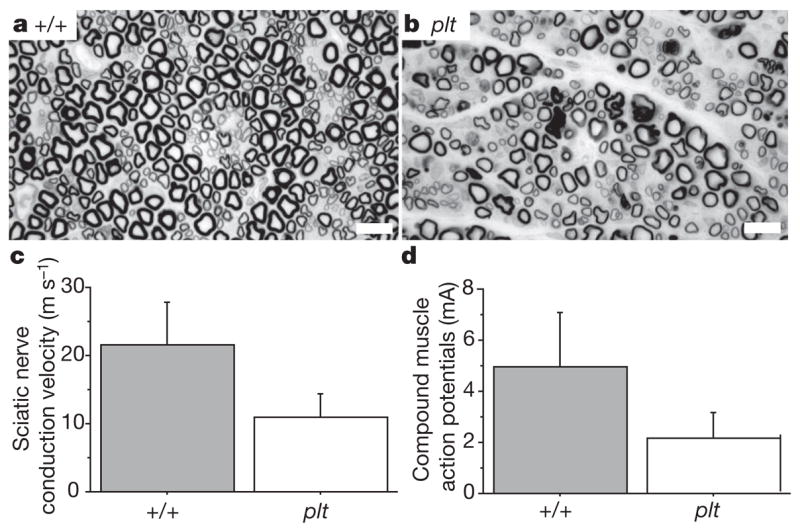

Peripheral nerves are also affected. Cross-sections of the sciatic nerve reveal substantial reduction in the number of large-diameter myelinated axons in the mutant (Fig. 3a, b). Nerve conduction velocity and amplitude of compound muscle action potentials are reduced (Fig. 3c, d), consistent with the axonal loss visible in the sections of the sciatic nerve and the pathological abnormalities in the motor neurons. There was no response when recording from tail sensory fibres, consistent with the severe loss of sensory neurons from the dorsal root ganglia shown in Fig. 2a.

Figure 3. Pathological abnormalities in peripheral nerves.

a, b, Semi-thin sections of sciatic nerve prepared as described27, demonstrating reduced density of large-diameter myelinated axons in the pale tremor mutant. Scale bars, 10 μm. c, d, Reduced sciatic nerve conduction velocity (mutant, 11.0 ± 3.4 m s−1; wild type, 21.5 ± 6.3 m s−1) and reduced amplitude of compound muscle action potentials (mutant, 2.2 ± 1.0 mA; wild type, 5.0 ± 2.1 mA) (mean ± s.d., n = 6).

In the brain, neuronal loss in the thalamus, pons, medulla and deep cerebellar nuclei is visible at one week of age (Supplementary Fig. 6). By three weeks of age there is additional loss of neurons from layers four and five of the cortex, the deep layers of the superior and inferior colliculus and the olfactory bulb (Fig. 2g). Some neuronal cell bodies contain enlarged vacuoles (Fig. 2h); these vacuoles are not stained by Oil Red O (for lipid) or periodic acid Schiff (for carbohydrate) (not shown). Hippocampus, cerebellar cortex and cerebral cortex layers one, two, three and six remain relatively unaffected throughout the course of the disease, although under culture conditions hippocampal neurons become vacuolated (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). The abnormal gait and motor coordination in the pale tremor mutant may be accounted for by abnormal proprioception owing to degeneration of dorsal root ganglia neurons, in combination with degeneration of neurons from brain regions directly involved in motor control (layer five of the cortex, thalamus and deep cerebellar nuclei).

Abnormalities are visible in skin and spleen. Pigment-containing hair follicles are greatly reduced in number and the few pigmented hairs contain clumped melanosomes (Supplementary Fig. 7), similar to mouse mutants with defects in lysosome–melanosome biogenesis11. There is extensive cell loss in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 8). White blood cell profiles are normal, and liver, kidney and testis appear normal when observed by light microscopy.

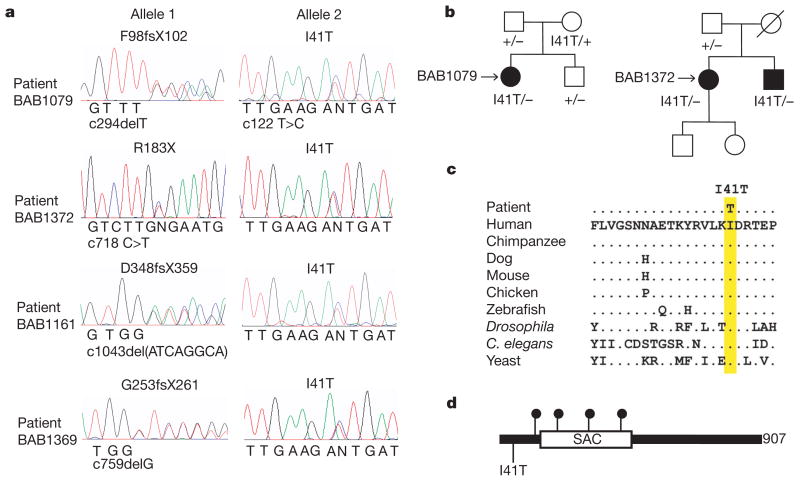

The clinical and pathological features of peripheral neuropathy in pale tremor mice resemble some types of Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) disorder12,13. We tested FIG4 as a candidate gene by screening 95 individuals diagnosed with CMT disorder but lacking mutations in known genes13. The 23 coding exons of FIG4 were amplified from genomic DNA, screened by heteroduplex analysis and sequenced. Patient BAB1079 has a severe, early onset disorder. We identified the protein truncation mutation F98fsX102 in exon 4 and the missense mutation I41T in exon 2 of FIG4 (Fig. 4a). F98fsX102 truncates the protein within the SAC domain and is likely to be a loss-of-function allele. Pedigree analysis demonstrated autosomal recessive inheritance. Each mutation was inherited from a heterozygous parent (Fig. 4b). Two heterozygous carriers of F98fsX102 are unaffected, indicating that FIG4 is not haploinsufficient. Heterozygous pale tremor mice at 18 months of age are also unaffected.

Figure 4. Mutations of FIG4 in patients with CMT disorder.

a, Sequencing chromatographs for four unrelated patients with CMT disorder. Nucleotide mutations are indicated on the x-axis of each chromatograph numbered from +1 for the first codon. b, Inheritance of mutant alleles in two pedigrees. Circle, female; square, male; open symbol, unaffected; filled symbol, affected. Patient BAB1079 is a compound heterozygote for protein truncation mutation F98fsX102 and missense mutation I41T. Patients BAB1372 and BAB1373 are compound heterozygotes for nonsense mutation R183X and missense mutation I41T. c, Residue isoleucine 41 is evolutionarily invariant in FIG4 from vertebrates, invertebrates and yeast. d, Location of CMT mutations in the FIG4 protein. Solid circles, protein truncation mutations. 907 amino acids are present per protein.

Another patient, BAB1372, was found to be a compound heterozygote with a nonsense mutation R183X in exon 6 together with I41T (Fig. 4a). R183X was inherited from the patient’s father (Fig. 4b). The mother is an obligate carrier of I41T, and the patient has an affected sibling (BAB1373) that also inherited both mutations (Fig. 4b). Both siblings have severe disease: BAB1372 is functionally quadriplegic and BAB1373 is wheelchair-bound although retaining normal use of his arms. Both have slow nerve conduction velocities. A sural nerve biopsy for BAB1373 demonstrated profound axonal loss, thinly myelinated nerve fibres and evidence of de- and re-myelination.

Two additional patients, BAB1161 and BAB1369, carry unique truncation mutations together with I41T (Fig. 4a). Both patients developed disease by the age of five and demonstrate reduced nerve conduction velocity (2–7 m s−1, compared with normal values of 40–50 m s−1). One patient had motor developmental delay consistent with Dejerine–Sottas neuropathy.

It is remarkable that four unrelated Caucasian patients carry the same missense mutation. No additional coding or splice site variants were detected in these patients when all 23 exons of FIG4 were sequenced. Isoleucine 41 is located upstream of theSAC phosphatase domain and is evolutionarily invariant in FIG4 from yeast, invertebrates and vertebrates (Fig. 4c, d). We sequenced exon 2 from 295 neurologically normal Caucasian controls but did not identify carriers of this variant. The observed allele frequencies were 0/590 in controls and 4/190 in CMT patients (P = 0.003). The four patients carry I41T on the same 15 kb haplotype, defined by single nucleotide polymorphisms rs3799845 (G), rs2025249 (C) and rs7764711 (G) (haplotype frequency 0.29; disequilibrium coefficient, D′ = 51), consistent with inheritance of a common ancestral mutant allele (see data in Supplementary Fig. 9). The evidence suggests that I41T is a rare allele causing partial loss of function that is pathogenic in combination with a null allele of FIG4.

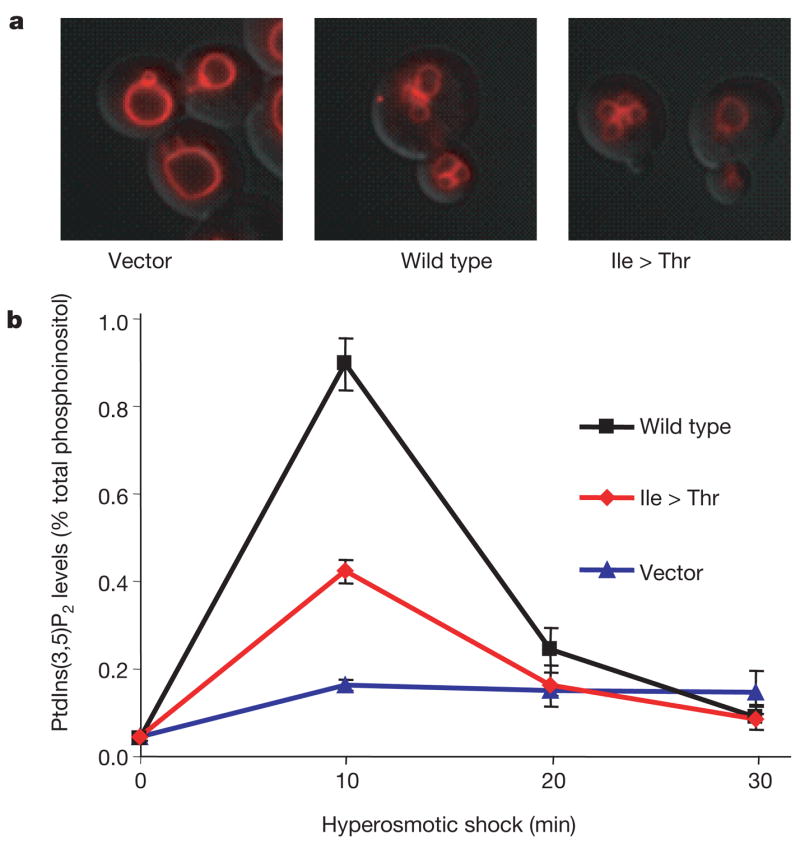

To assess the functional effect of the I41T allele, we tested the corresponding mutation (I59T) in yeast. Wild-type and mutant cDNAs were transformed into the yeast strain fig4Δ lacking functional Fig4 (ref.7). Transformation with the empty vector did not correct the enlarged vacuoles in fig4Δ, which reflects the slightly reduced levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 that result from the absence of Fig4 (ref. 7) (Fig. 5a). The vacuolar enlargement was corrected to a comparable extent by wild-type and mutant Fig4, indicating that, under basal conditions, cells expressing Fig4I59T produce normal levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (Fig. 5a). The ability of the mutant to activate Fab1/PIKfyve kinase was tested by treatment with hyperosmotic shock as previously described5,7. In cells expressing wild-type Fig4, hyperosmotic shock produces a transient tenfold increase in intracellular PtdIns(3,5)P2 concentration owing to activation of Fab1/PIKfyve kinase (Fig. 5b). In cells expressing the mutant, a partial fourfold increase was observed, demonstrating impaired activation of Fab1/PIKfyve kinase. It is not clear whether the phosphatase activity of the mutant is also impaired, owing to the low levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2.

Figure 5. Yeast Fig 4Ile > Thr is defective in activation of kinase Fab1/PIKfyve.

The fig 4Δ yeast strain lacking endogenous Fig 4 (refs 5, 7) was transformed with empty vector (vector), wild-type myc-Fig4 or myc-Fig4 containing I59T corresponding to human I41T (mutant). a, Yeast were labelled with FM4–64 to assess vacuole volume, an indicator of basal levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2. b, Time course of PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels after hyperosmotic shock (measured in minutes after change to hyperosmotic medium) reflects activation of Fab1 kinase. The mutant protein exhibits impaired activation at 10 min compared with the wild type (P = 0.004; mean ± s.d., n = 3). A western blot demonstrating comparable expression of wild-type and mutant constructs is presented in Supplementary Fig. 10.

The data presented here demonstrate that mutation of FIG4 is responsible for peripheral neuronopathy in human patients. We propose the designation CMT4J for this disorder, based on the recessive inheritance pattern. Phosphoinositide signalling has previously been implicated in CMT disorder types 4B1, 4B2 and 4H (ref. 14–19) (see Supplementary Discussion). Other genes that function in vesicle trafficking, such as RAB7A and DNM2 in human20,21 and Vps54 in mouse22, are associated with inherited neuropathies.

The pale tremor mutant provides the first evidence regarding the functional role of mammalian Fig4. The results demonstrate a conserved biochemical function in metabolism of PtdIns(3,5)P2, a conserved cellular role in regulation of endosomal vesicles, and an unexpected role in neuronal survival. The molecular basis for the differential sensitivity of neuronal subtypes to loss of this widely expressed gene is unclear. Neuronal dependence on FIG4 may be related to the role of endosomal vesicles in delivering membrane components to dendritic spines during long-term potentiation23. The pale tremor mouse will generate insights into PtdIns(3,5)P2 signalling in neurons and provide an animal model for CMT4J and related human neuropathies.

METHODS

Animals

For genetic mapping, plt/+ heterozygotes were crossed with strain CAST/Ei (Jackson Laboratory). Experiments were carried out on F2 and F3 mice from the mapping cross. This research was approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Animals were housed and cared for in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Genotyping and markers

Genotyping was carried out using microsatellite markers from public databases as well as novel microsatellite markers designed from mouse genomic sequence (http://www.ensemble.org). D10Umi13 was amplified with the forward primer 5′-CCACCACATCAACAGGCTCACAGG and the reverse primer 5′-AATGCAACCGTGACACAAGTACAC. PCR was carried out with the PCR core kit (Qiagen). PCR products were separated on 6% acrylamide gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The pale tremor mutation is genotyped by PCR with a forward primer in intron 18 (5′-CGTATGAATT-GAGTAGTTTTGATG) and two reverse primers, one in the proximal LTR of the inserted ETn2β element (5′-GCTGGGGGAGGGGAGACTACACAG) and one in exon 19 (5′-ATGGACTTGGATCAATGCCAACAG).

RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from brain of P7 mice, before extensive neurodegeneration. cDNA was synthesized using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). RT–PCR was carried out with the PCR Core Kit (Qiagen). Long-range PCR was performed with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche). The northern blot with 3 μg of polyA+RNA was prepared as previously described28. The hybridization probe, a 1 kb RT–PCR product containing exons 8 to 15, was labelled with two radiolabelled nucleotide triphosphates.

Histology

Tissues were sectioned and stained at HistoServ. Fast blue/eosin staining was carried out in the Department of Pathology, University of Michigan. Light microscopy was performed on an Olympus BX-51 microscope and DP50 camera. Sciatic and femoral nerves were sectioned and stained with osmium for electron microscopy as previously described27. Skin whole mounts were prepared from P10 mice with the guidance of A. Dlugosz. The commercial depilatory Nair was applied to the dorsal surface for five minutes followed by washing with warm water to remove hair. The skin was dissected and superficial fascia removed. Follicles were visualized on a standard dissecting microscope with transmitted light.

Neurophysiology

Nerve conduction velocities were recorded from affected pale tremor mice and littermate controls. Mice were anaesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine solution and placed under a heating lamp to maintain body temperature at 32 °C. Recordings were obtained using a Nicolet VikingQuest portable system and Nicolet disposable EEG needles. Tail sensory responses were obtained by stimulating proximally over a 3 cm region. Sciatic nerve motor velocities were obtained by stimulating distally at the sciatic notch and proximally at the knee.

Cell culture and immunofluorescence

Primary fibroblasts were cultured from mouse tail biopsies treated with collagenase. Cells were plated in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for up to three passages. For immunofluorescence, 100,000 cells were seeded on polylysine-coated cover slips in 35 mm dishes. We thank T. August and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for monoclonal antibody to LAMP-2, developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa. For labelling with antibody, cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol at −20 °C for 5 min and blocked with 2% goat serum. Antibodies were applied for 1 h in PBS with 2% serum at room temperature and detected with Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes) or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rat (Molecular Probes). Cells were visualized on a DeltaVision Deconvolution microscope system (Applied Precision).

Hippocampal neurons were cultured with glial conditioned media. Neurons were visualized with a Nikon TE2000 microscope.

Phosphoinositide assays

Fibroblast phosphoinositides were labelled with myo-[2-3H] inositol, extracted and quantified by HPLC. Mouse fibroblasts from the first passage were grown in 100 mm dishes to 60–70% confluency. The culture was rinsed with PBS and starved for 12 h in inositol-free DMEM (Tissue Culture Support Centre, Washington University) supplemented with 5 μg ml−1 transfer-rin, 5 μg ml−1 insulin and 10% dialysed fetal bovine serum. The medium was replaced with labelling medium (inositol-free DMEM containing 5 μg ml−1 transferrin, 20 mM HEPES and 50 μCi myo-[2-3H] inositol, GE Healthcare). After 24 h, the culture was treated with 0.6 ml of 4.5% (v/v) perchloric acid for 15 min, scraped off the plate, and spun down at 12,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with 0.1 M EDTA once and resuspended in 50 μl deionized water. To deacylate the lipids, samples were transferred to a glass vial, mixed with 1 ml methanol/40% methylamine/n-butanol (4:4:1, v/v), and incubated at 55 °C for 1 h. The resulting samples were vacuum-dried, resuspended in 0.3 ml water and extracted twice with an equal volume of n-butanol/ethyl ether/formate (20:4:1, v/v). The aqueous phase was vacuum dried and resuspended in 20 μl water.

For separation of all isoforms of the glycerophosphoinositides by HPLC, two different elution gradients were used at 1 ml min−1 flow rate. (Pump A, H2O; pump B, 1 M (NH4)2HPO4, pH 3.8.) Gradient 1: 0% B for 5 min; 0–2% B over 15 min; 2% B for 80 min; 2–12% B over 20 min; 12% B for 20 min; 12–80% B over 40 min; 80% B for 20 min; 80–0% B over 5 min. To separate glyceroPtdIns(3,4)P2 from glyceroPtdIns(3,5)P2, a longer gradient (gradient 2) was used: 0% B for 5 min; 0–2% B over 15 min; 2% B for 80 min; 2–10% B over20 min; 10% B for 65 min; 10–80% B over 40 min; 80% B for 20 min; 80–0% B over 5 min. The positions of glyceroPtdIns(3)P, glyceroPtdIns(3,5)P2, glyceroPtdIns(3,4)P2 and glyceroPtdIns (3,4,5)P3 were determined by 32P-labelled standards received as gifts from L. Rameh. The positions of glyceroPtdIns(4)P and glyceroPtdIns(4,5)P2 were confirmed with yeast glycerophosphoinositide extracts.

Human mutation detection

The cohort of unrelated patients with CMT disorder was previously described13. The clinical diagnosis was based on clinical examination, electrophysiological studies and, in a few cases, nerve biopsy. All patients received appropriate counselling and gave informed consent approved by the institutional review board. For the initial screen of FIG4, each coding exon was amplified and examined by heteroduplex analysis as previously described25. The patient mutations were identified by sequencing products exhibiting abnormal mobility. Subsequently, the 23 exons of FIG4 were completely sequenced from the four individuals carrying variants.

METHODS SUMMARY

Mutation of the pale tremor gene arose on a mixed background derived from inbred mouse strains 129/Ola, C57BL/6J, C3H and SJL (ref. 24). The mutant allele is designated Fig4paletremor. Total RNA was isolated from brain of P7 mice before extensive neurodegeneration. Primary fibroblasts were cultured from mouse tail biopsies treated with collagenase. Phosphoinositides were labelled for 24 h with myo-[2-3H] inositol, extracted and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, see Methods). The cohort of unrelated patients with CMT disorder was previously described13. The 23 coding exons of FIG4 were screened by heteroduplex analysis25 and products with abnormal mobility were sequenced. For the four individuals with identified mutations, all of the other exons were sequenced. Genomic DNA from neurological normal control individuals was obtained from the Coriell Institute (NDPT006 and NDPT009, 96 samples each) and from a collection of 111 subjects older than 60 without personal or family history of neurological disease26.

Supplementary Material

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgments

For discussions and advice we are grateful to A. Dlugosz, E. Feldman, D. Goldowitz, J. Hammond, L. Isom, J. M. Jones, A. Lieberman, M. Khajavi, J. Swanson, K. Verhey and S. H. Yang. S. Cheek and M. Hancock provided technical assistance. This research was supported by NIH research grants (M.H.M., L.W. and J.R.L.) and NIH predoctoral training (C.Y.C.).

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michell RH, Heath VL, Lemmon MA, Dove SK. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate: metabolism and cellular functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maksakova IA, et al. Retroviral elements and their hosts: insertional mutagenesis in the mouse germ line. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes WE, Cooke FT, Parker PJ. Sac phosphatase domain proteins. Biochem J. 2000;350:337–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duex JE, Tang F, Weisman LS. The Vac14p–Fig4p complex acts independently of Vac7p and couples PI3,5P2 synthesis and turnover. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:693–704. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudge SA, Anderson DM, Emr SD. Vacuole size control: regulation of PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels by the vacuole-associated Vac14–Fig4 complex, a PtdIns(3,5)P2-specific phosphatase. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:24–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duex JE, Nau JJ, Kauffman EJ, Weisman LS. Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase Fig 4p is required for both acute rise and subsequent fall in stress-induced phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate levels. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:723–731. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.4.723-731.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonangelino CJ, et al. Osmotic stress-induced increase of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate requires Vac14p, an activator of the lipid kinase Fab1p. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1015–1028. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gary JD, et al. Regulation of Fab1 phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase pathway by Vac7 protein and Fig4, a polyphosphoinositide phosphatase family member. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1238–1251. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutherford AC, et al. The mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase (PIKfyve) regulates endosome-to-TGN retrograde transport. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3944–3957. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks MS, Seabra MC. The melanosome: membrane dynamics in black and white. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:738–748. doi: 10.1038/35096009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroder JM. Neuropathology of Charcot–Marie–Tooth and related disorders. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:23–42. doi: 10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szigeti K, Garcia CA, Lupski JR. Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease and related hereditary polyneuropathies: molecular diagnostics determine aspects of medical management. Genet Med. 2006;8:86–92. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000200160.29385.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley MJ, et al. Molecular basis for substrate recognition by MTMR2, a myotubularin family phosphoinositide phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:927–932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolino A, et al. Disruption of Mtmr2 produces CMT4B1-like neuropathy with myelin outfolding and impaired spermatogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:711–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolino A, et al. Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 4B is caused by mutations in the gene encoding myotubularin-related protein-2. Nature Genet. 2000;25:17–19. doi: 10.1038/75542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonneick S, et al. An animal model for Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 4B1. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3685–3695. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senderek J, et al. Mutation of the SBF2 gene, encoding a novel member of the myotubularin family, in Charcot–Marie–Tooth neuropathy type 4B2/11p15. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:349–356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stendel C, et al. Peripheral nerve demyelination caused by a mutant Rho GTPase guanine nucleotide exchange factor, frabin/FGD4. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1086/518770. in the press. preprint at http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/AJHG/journal/preprints/AJHG44688.preprint.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Verhoeven K, et al. Mutations in the small GTP-ase late endosomal protein RAB7 cause Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2B neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:722–727. doi: 10.1086/367847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuchner S, et al. Mutations in the pleckstrin homology domain of dynamin 2 cause dominant intermediate Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. Nature Genet. 2005;37:289–294. doi: 10.1038/ng1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt-John T, et al. Mutation of Vps54 causes motor neuron disease and defective spermiogenesis in the wobbler mouse. Nature Genet. 2005;37:1213–1215. doi: 10.1038/ng1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park M, et al. Plasticity-induced growth of dendritic spines by exocytic trafficking from recycling endosomes. Neuron. 2006;52:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adamska M, Billi AC, Cheek S, Meisler MH. Genetic interaction between Wnt7a and Lrp6 during patterning of dorsal and posterior structures of the mouse limb. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:368–372. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escayg A, et al. Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2. Nature Genet. 2000;24:343–345. doi: 10.1038/74159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rainier S, Sher C, Reish O, Thomas D, Fink JK. De novo occurrence of novel SPG3A/atlastin mutation presenting as cerebral palsy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:445–447. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, et al. Major myelin protein gene (P0) mutation causes a novel form of axonal degeneration. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:252–265. doi: 10.1002/cne.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohrman DC, Harris JB, Meisler MH. Mutation detection in the med and medJ alleles of the sodium channel Scn8a. Unusual splicing due to a minor class AT–AC intron. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17576–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.