Abstract

The first step of this study was to determine the early time course and pattern of hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) recovery following irreversible bilateral carotid sinus nerve transection (CSNT). The second step was to find out if HVR recovery was associated with changes in the neurochemical activity of the medullary catecholaminergic cell groups involved in the O2 chemoreflex pathway.

The breathing response to acute hypoxia (10% O2) was measured in awake rats 2, 6, 10, 45 and 90 days after CSNT. In a control group of sham-operated rats, the ventilatory response to hypoxia was principally due to increased respiratory frequency. There was a large reduction in HVR in the CSNT compared to the sham-operated rats (−65%, 2 days after surgery). Within the weeks following denervation, the CSNT rats progressively recovered a HVR level similar to the sham-operated rats (-37% at 6 days, −27% at 10 days, and no difference at 45 or 90 days). After recovery, the CSNT rats exhibited a higher tidal volume (+38%) than the sham-operated rats in response to hypoxia, but not a complete recovery of respiratory frequency.

Fifteen days after CSNT, in vivo tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity had decreased in caudal A2C2 (−35%) and A6 cells (−35%). After 90 days, the CSNT rats displayed higher TH activity than the sham-operated animals in caudal A1C1 (+51%), caudal A2C2 (+129%), A5 (+216%) and A6 cells (+79%).

It is concluded that HVR following CSNT is associated with a profound functional reorganisation of the central O2 chemoreflex pathway, including changes in ventilatory pattern and medullary catecholaminergic activity.

Hyperventilation is the primary adaptive response to hypoxia in all mammalian species. The increased breathing is mediated by peripheral arterial chemoreceptors, including the carotid bodies, the aortic bodies and, possibly, the carotid body-like organs (paraganglia) scattered along the gross trunk blood vessels (McDonald & Blewett, 1981). Rat carotid bodies are generally considered as the main initiators of the hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR). Bilateral carotid sinus nerve transection (CSNT) induces hypoventilation in normoxic conditions, and abolishes the HVR (Sapru & Krieger, 1977). However, studies have shown that the initial loss of HVR is followed by its progressive recovery within the following weeks (Bisgard et al. 1976; Smith & Mills, 1980; Martin-Body et al. 1985, 1986). Although the mechanism involved in this recovery is still unclear, it may be due to a central reorganisation of the chemoreflex pathway following a break in the sensory pathway from the carotid bodies, which would enhance the efficacy of the aortic ventilation chemoreflex (Majumdar et al. 1982; Martin-Body et al. 1986). In cats deprived of carotid sinus nerve afferents, Majumdar et al. (1982) reported changes in the efficacy of the aortic depressor nerve reflexes. Majumdar et al. (1983), in a subsequent neuroanatomical study, provided direct evidence for the central reorganisation of arterial chemoreflex pathways, with the initial degeneration of the central carotid sinus nerve terminals being found to be followed by a renewed central sprouting in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). More recent studies have suggested the possibility of a direct hypoxic stimulation of neurones in brain regions such as the rostro-ventrolateral medulla (Nolan & Waldrop, 1993, 1996; Sun & Reis, 1994), the hypothalamus (Nolan et al. 1995) and the red nucleus (Waites et al. 1996). This central O2-sensing mechanism could be involved in HVR recovery observed after CSNT.

In the rat, the afferent chemosensory fibres project into discrete areas of the medulla oblongata, mainly the caudal part of the NTS, and, to a lesser extent, the ventrolateral medulla (Housley et al. 1987; Finley & Katz, 1992). Both medullary areas contain two major respiratory cell groups: the dorsal respiratory group, in the ventrolateral subset of the solitary tract, and the ventral respiratory group, in the ventrolateral medulla. It is worth noting that these two medullary respiratory groups are closely associated with catecholaminergic neurones which belong respectively, to the A2C2 cell group and the A1C1 cell group. The medullary A2 noradrenergic neurones are adjacent to the dorsal respiratory group, while the A1C1 neurones are intermingled with the ventral respiratory group. There is growing evidence that medullary catecholaminergic neurones participate in the chemoreflex responses to systemic hypoxia (Guyenet et al. 1993; Bianchi et al. 1995; Smith et al. 1995). The respiratory premotorneurones do not synthesise catecholamines, but may possess adrenergic receptors, given that the iontophoretic application of α2 agonists depresses their discharge (Champagnat et al. 1979; Denavit-Saubié & Foutz, 1997). Noradrenergic A2 neurones display functional neuroplasticity in vivo during ventilatory acclimatisation to hypoxia (Schmitt et al. 1994). A5 and A6 cells are excited by hypoxic stimulation of peripheral chemoreceptors and are involved in central respiratory modulation (Guyenet et al. 1993; Coles & Dick, 1996). The A5 area is known to modify respiratory frequency and expiratory duration (Dick et al. 1995; Coles & Dick, 1996), and there is evidence that α2 receptors are involved in this respiratory mechanism (Errchidi et al. 1991). Systemic hypoxia enhances the recruitment of caudally located ventrolateral medullary catecholamine cells, which form a part of the A1 noradrenergic cell group (Smith et al. 1995). To date, however, there is no evidence that the neural activity of the central structures involved in respiratory regulation is affected by chemosensory recovery following CSNT.

Since the brainstem catecholaminergic cell groups play a prominent part in the modulation of the chemoreflex responses to hypoxia, we hypothesised that CSNT might produce functional changes in the catecholaminergic medullary areas during ventilatory recovery after CSNT. To test this hypothesis, we looked for possible ventilatory and neurochemical modifications in the chemoreflex pathway during the reorganisation process. The first step was to determine the early time course, and the pattern of HVR recovery following CSNT, by analysis of respiratory frequency (f), tidal volume (VT), and inspiratory (TI) and expiratory (TE) duration in rats. The second step was to measure the level of activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme of catecholamine biosynthesis, in medullary catecholaminergic cell groups before and after HVR recovery.

METHODS

Experiments were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats (240–260 g, IFFA CREDO, France) housed in an air-conditioned room at 23°C with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle, and with food and water available ad libitum. Animal care was in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institute of Health Publication No. 85–23, revised 1985), and the experiments were carried out under licence No. 3030, granted by the Veterinary Service of the French Ministry of Agriculture.

Surgery

The animals were anaesthetised by a single intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (1 ml (100 g body weight)−1 of 1.4% tribromoethanol) so as to make them areflexic to a nociceptive stimulus (a pinch to the front paw), as checked during the surgical procedure. The first group (sham-operated, n = 38) was operated on, but not chemodenervated. Body temperature was maintained close to 37°C using a heated underblanket. The second group was subjected to CSNT (n = 38). The two carotid sinus nerves were transected at the point where they branched off from the glossopharyngeal nerve, and at the cranial pole of the carotid body. Denervation was performed under a dissection microscope. The procedure used for the sham operation included the same midline approach as for the CSNT rats. Both carotid bifurcations were then exposed. Body-growth values were not affected by surgery, either in the sham-operated or the CSNT rats. Following surgery, the wounds were painted twice a day with a 10% polyvidone iodine solution (Betadine) in order to prevent infection.

Ventilation

Ventilation was measured in awake unrestrained rats 2, 6, 10, 45 and 90 days after chemodenervation, using a barometric plethysmograph, as described by Bartlett & Tenney (1970). To avoid possible hypoxic habituation, a different group of rats was used each stage after surgery (n = 6 at 2, 6, 10, 90 days; n = 9 at 45 days). A plexiglass plethysmographic chamber adapted to rats (volume 5.4 l), and flushed with heated, humidified air, was connected to a reference chamber of the same size. Both chambers were saturated with water vapour. Temperature, O2 and CO2 levels in the chamber which housed the animal were continuously monitored. The plethysmograph was calibrated by injecting 1 ml of air into the animal chamber. Immediately after calibration, an animal was placed in the chamber and left until it was calm. At this point the flow was interrupted, the inlet and outlet tubes of the chamber were closed, and the pressure fluctuations caused by breathing were recorded with a differential pressure transducer (Celesco, CA, USA). VT (ml), f (min−1), minute ventilation (V̇E; ml min−1), TI (s), TE (s) and the total respiratory cycle (Ttot; (s)) were calculated from breath-by-breath by computer analysis of the spirogram. All measurements were taken in quadruplicate, separated by intervals of 10–15 min, depending on the degree of activity of the rat. The mean of these four values was taken as the basal (normoxic) ventilation. The hypoxic test was then carried out by flushing the plethysmograph chamber with a mixture of 10% O2 and 90% N2. Washout of the plethysmograph required about 3 min for the 5.4 l chamber to reach a new stable inspired O2 fraction. This was considered to be the beginning of hypoxia. After the 10% O2 level was reached inside the chamber, the system was clamped to perform the first measurement of the HVR involving 40–60 breath cycles. The plethysmograph was then flushed again with the same gas mixture. Subsequent HVR recordings were done in the same way at 4, 7 and 10 min after the beginning of hypoxia. All the recordings were performed at thermoneutrality (26 ± 1°C), as described by Gautier & Bonora (1992), whose study showed no difference in body temperature between CSNT and sham-operated rats during the first 10 min of hypoxia.

Neurochemistry

Tyrosine hydroxylase activity can be used as a marker of the rate of catecholamine synthesis. Indeed, in noradrenergic and adrenergic cell groups it is considered to be proportional to, respectively, the noradrenaline and adrenaline synthesis levels. In vivo TH activity is estimated by measuring the L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) accumulation after the inhibition of L-amino acid decarboxylase by NSD 1015 (3-hydroxybenzylhydrazine dichloride: Sigma) (Carlsson et al. 1972). NSD 1015 was injected intraperitoneally (100 mg (kg body weight)−1) 10 min before the animals were killed. TH activity was expressed in picomoles of L-DOPA formed during these 10 min, and per pair of structures.

Tissue dissection for biochemical analyses

Two groups of rats were killed by cervical dislocation at 15 days (n = 5) and 90 days (n = 5) after CSNT. Blood samples were drawn from the heart by puncture. The brain was rapidly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. The brainstem was cut into serial coronal slices 480 μm thick. The noradrenergic cell groups A5 and A6, and the noradrenergic and adrenergic cell groups A1C1 and A2C2 were punched out (needle diameter 0.9 mm) according to the dissection procedure described by Palkovits & Brownstein (1988). As previously described (Soulier et al. 1992), A2C2 was divided into two subsets, caudal (A2C2c) and rostral (A2C2r) to the calamus scriptorius, in order to distinguish the area receiving chemosensory inputs from the area to which the barosensory fibres project within the NTS (Housley et al. 1987; Finley & Katz, 1992). In the same way, A1C1 was divided into two subsets, caudal (A1C1c) and rostral (A1C1r), which accounted, respectively, for most of the A1 and C1 cell groups.

In all cases, the various structures were dissected out bilaterally, and the catecholamines in each pair of structures were assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection. The structures were broken down by ultrasound in 100 μl of 0.1 M perchloric acid containing 2.7 mM EDTA-Na2. The homogenates were centrifugated (8800 g, 5 min) and a 10 μl aliquot of the supernatant was injected directly into a reverse phase column (ODS-Hypersil, 5 μm, 150 mm × 4.6 mm, Shandon, Cheshire, UK) with a mobile phase consisting of 27 mM citric acid, 50 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.8 mM sodium acetyl sulphate and 8% methanol. The flow rate was 1.2 ml min−1. L-DOPA was measured at +0.72 V versus the Ag+-AgCl reference electrode (ELDEC 102, Chromatofield, Chateauneuf-les-Martigues, France). The detection limits, which were calculated by doubling the background noise level, and expressed in terms of picomoles of injected amounts, were less than 0.03 pmol for all compounds, and the intra-assay coefficients were 0.2%.

Blood parameters

Haematocrit levels were measured by a microtechnique method, and haemoglobin (Hb) concentrations with a kit (525A-Sigma).

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. A general ANOVA combining all the relevant factors was performed in order to assess the significance of the post hoc test.

Ventilation

A two-factor (treatment, date) analysis of variance was carried out in order to determine, in normoxia, differences in V̇E, VT, f, Ti, TE and Ttot between the CSNT and the sham-operated groups. The general response to 10 min of hypoxia was studied by a three-factor (treatment, date, time) analysis of variance using absolute values. To study the existence of the chemosensory response to hypoxia, resting values and response after 1 min of hypoxia were compared. In order to assess the time course of chemosensory responses to hypoxia, V̇E, VT and f were compared between 2 and 90 days after surgery.

The relative contributions of the VT and f components of the HVR were assessed over 10 min of hypoxia.

Neurochemistry

A two-factor (treatment, date) analysis of variance was used to determine differences in TH activity between the CSNT and the sham-operated groups.

Tyrosine hydroxylase activity is a specific marker of catecholaminergic systems, and the conditions of punching correspond to dissection by excess, including all the catecholamine-synthesising cells of the neurochemical structures being studied. Total protein content can fluctuate under physiological conditions, which means that the expression of TH activity per structure is better than the expression of results per milligram of protein for avoiding artefactual variations in TH activity, following modifications of total protein content in a given structure.

RESULTS

Body weight and haematological parameters

The mean body weight of the sham-operated and CSNT groups was never different after surgery (sham-operated vs. CSNT rats: 243 ± 3 vs. 245 ± 2 g at 2 days; 270 ± 2 vs. 275 ± 4 g at 6 days; 292 ± 2 vs. 294 ± 4 g at 10 days; 465 ± 9 vs. 489 ± 6 g at 45 days; 493 ± 9 vs. 496 ± 5 g at 90 days).

At 15 or 90 days post surgery no differences between the two groups were observed in the haematocrit (sham-operated vs. CSNT rats: 41.3 ± 1.1 vs. 41.2 ± 1.9% at 15 days; 41.6 ± 1.7 vs. 45 ± 1.5% at 90 days) and haemoglobin (sham-operated vs. CSNT rats: 15.2 ± 0.5 vs. 15.6 ± 0.6 g ml−1 at 15 days; 16.0 ± 0.5 vs. 15.9 ± 0.6 g ml−1 at 90 days) levels.

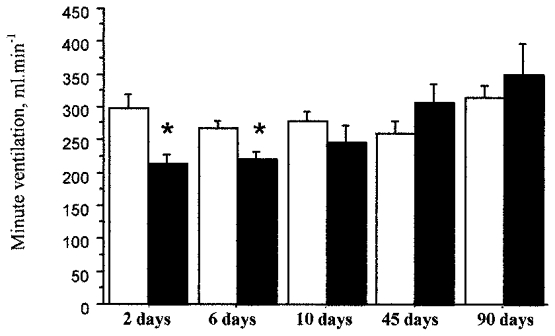

Resting ventilatory minute ventilation

Minute ventilation in normoxia (Fig. 1) was lower in the CSNT than the sham-operated rats at 2 days (-29%) and 6 days (-17%) after surgery. Thereafter, no difference was detected between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Time course of resting minute ventilation (V̇E) after carotid sinus nerve transection in rats breathing room air. The bars represent the mean ±s.e.m. of V̇E in sham-operated (□) and CSNT (▪) rats under normoxia. The time course is measured in days post surgery. * Statistically significant difference between values in the sham-operated and CSNT groups; P < 0.05 (n = 6 for 2, 6, 10 and 90 days in both the sham-operated and CSNT rats; n = 10 for 45 days in both sham-operated and CSNT rats).

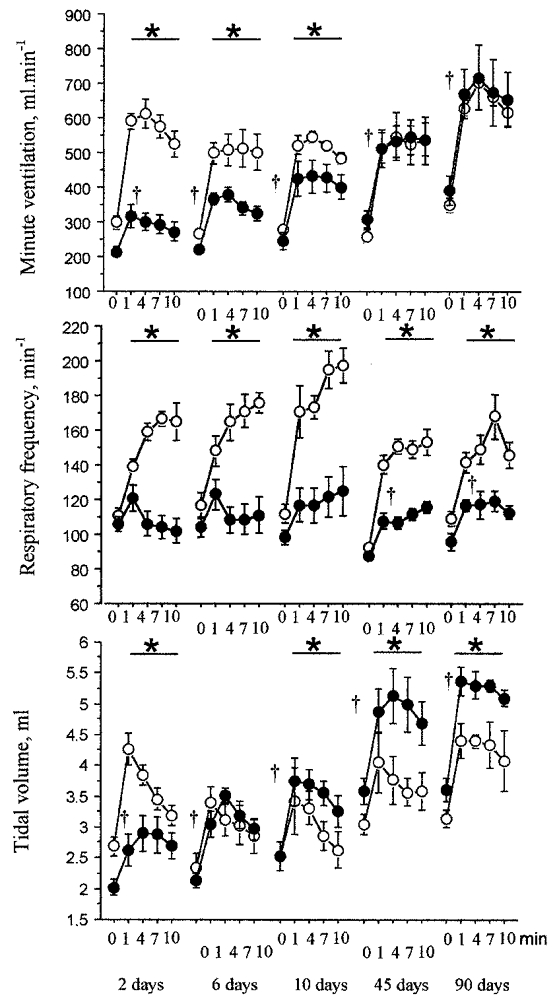

Hypoxic ventilatory response

HVR was much reduced in the CSNT rats 2 days after surgery (Fig. 2), but a gradual recovery was observed within the weeks following surgery: at 1 min after the hypoxic exposure, the CSNT rats had a lower HVR than the sham-operated rats, (-65% after 2 days; −37% after 6 days; −27% after 10 days). At 45 and 90 days after surgery, the CSNT rats had regained the same HVR level as the sham-operated animals. Moreover, the CSNT rats displayed a progressive increase in HVR (+77% at 10 days; +100% at 45 days; +171% at 90 days). HVR recovery was primarily due to a progressive increase in the VT response to hypoxia. Two days after surgery, the VT response of the CSNT group was less marked than that of the sham-operated group (-62%). At 6 days, no difference was observed between the CSNT and the sham-operated rats. After 10, 45 and 90 days, the VT response became higher in the CSNT than the sham-operated rats (+34% at 10 days; +29% at 45 days; +38% at 90 days) (Fig. 2). Moreover, the CSNT rats displayed a progressive increase in VT response to hypoxia (+101% at 10 days; +117% at 45 days; +194% at 90 days). No f response to hypoxia was detected in the CSNT rats at 2, 6 and 10 days after surgery. At 45 and 90 days, the CSNT rats showed an increase in f response to hypoxia, but to a lesser extent than the sham-operated rats (responses at 45 and 90 days were 41 and 61% relative to sham-operated rats).

Figure 2.

Time course of minute ventilation (V̇E), respiratory frequency (f) and tidal volume (VT) in response to hypoxia after carotid sinus nerve transection. The points represent the means ±s.e.m. of V̇E, f and VT in sham-operated (○) and CSNT (•) rats. The time course is measured in days post surgery. * Statistically significant differences between values in the sham-operated and CSNT groups; †statistically significant differences between values at the first minute of hypoxia (10% O2 and 90% N2) and normoxic values in the CSNT group; P < 0.05 (n = 6 at 2, 6, 10 and 90 days for both the sham-operated and CSNT rats; n = 10 at 45 days for both the sham-operated and CSNT rats).

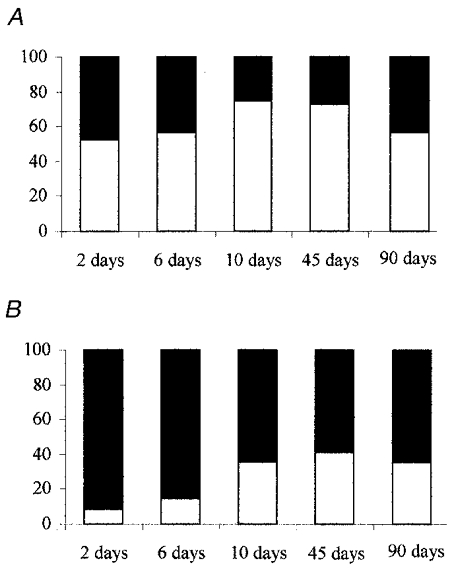

Relative proportion of respiratory frequency and tidal volume components in minute ventilation

Frequency was the component mainly affected in HVR in the sham-operated rats increasing (from 53% of the V̇E response 2 days after surgery to 59% at 90 days) (Fig 3 and Fig 4). In contrast, VT was the component mainly affected in the HVR in CSNT rats, extending from 92% of the V̇E response 2 days after surgery to 66% after 90 days.

Figure 3.

Relative proportions of respiratory frequency and tidal volume in the ventilatory response to hypoxia after carotid sinus nerve transection in the rat. The bars represent the relative mean proportions of the f (□) and VT (▪) components of the V̇E response to hypoxia in the sham-operated (A) and CSNT (B) rats. The data were measured over 10 min of hypoxia. The time course is measured in days post surgery (n = 6 at 2, 6, 10 and 90 days for both the sham-operated and CSNT rats; n = 10 at 45 days for both the sham-operated and CSNT rats).

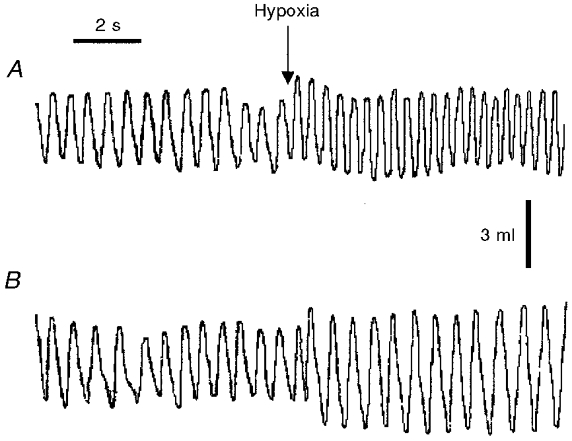

Figure 4.

Respiratory recording in normoxia and in response to hypoxia in a sham-operated rat (A) and in a CSNT rat (B) 90 days after surgery. Ventilation was measured in normoxia and during the first minute of hypoxia. The mean values over the entire recording period are (hypoxia vs. normoxia): for the sham-operated rat, f = 159 vs. 105 min−1 and VT = 4.1 vs. 3.1 ml; for the CSNT rat: f = 109 vs. 99 min−1 and VT = 5.4 vs. 3.2 ml.

Respiratory duration in normoxia and hypoxia

Two days after surgery, no difference in respiratory duration was observed between the CSNT and sham-operated rats in normoxia, or in response to hypoxia (Table 1). Ninety days after surgery, CSNT rats in normoxia exhibited an increase in Ttot (+12%) compared to sham-operated animals, due to an increase in TI (+28%). In response to hypoxia, CSNT rats exhibited an increase in Ttot (+27%) due to an increase in TE (+30%).

Table 1.

Respiratory duration (s) in normoxia and in response to hypoxia 2 and 90 days after carotid sinus nerve transection

| Sham | CSNT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | Normoxia | Hypoxia | |

| 2 days | ||||

| Ttot | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.03 |

| TI | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| TE | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| 90 days | ||||

| Ttot | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.02* | 0.57 ± 0.03* |

| TI | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01* | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| TE | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.02 0 | 40 ± 0.02* |

The values are the means ± S.E.M. found in sham-operated (Sham) and CSNT rats 2 and 90 days after surgery; n = 6 in each group.

P < 0.05; statistically significant differences between values in the sham-operated and CSNT groups.

Neurochemistry

CSNT caused a decrease in TH activity in the A2C2c (-35%) and A6 (-35%) brainstem cell groups 15 days after surgery (Table 2). After 90 days, the CSNT group displayed higher TH activity than the sham-operated group in the A1C1c (+51%), A2C2c (+129%), A5 (+216%), and A6 (+79%) cell groups. There was no observed difference in the TH activity of the A2C2r and A1C1r cell groups between the CSNT and sham-operated rats at any stage after surgery.

Table 2.

In vivo tyrosine hydroxylase activity in brainstem noradrenergic cell groups 15 and 90 days after carotid sinus nerve transection

| 15 days | 90 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | CSNT | Difference | Sham | CSNT | Difference | |

| A1C1c | 3.09 ± 0.34 | 2.58 ± 038 | −17% | 2.41 ± 0.35 | 3.63 ± 0.40 | +51%* |

| A1C1r | 1.35 ± 0.19 | 1.82 ± 0.38 | +34% | 1.22 ± 0.20 | 1.36 ± 0.25 | +11% |

| A2C2c | 5.40 ± 1.17 | 3.51 ± 0.48 | −35%* | 2.07 ± 0.58 | 4.74 ± 0.73 | +129%* |

| A2C2r | 3.03 ± 0.44 | 3.68 ± 0.77 | +21% | 3.52 ± 0.24 | 3.53 ± 0.82 | 0% |

| A5 | 1.20 ± 0.14 | 1.15 ± 0.24 | −4% | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 2.98 ± 0.80 | +216%* |

| A6 | 17.83 ± 1.27 | 11.62 ± 1.28 | −35%* | 9.20 ± 1.60 | 16.45 ± 3.99 | +79%* |

The values are the means ± S.E.M. in the shamoperated and CSNT rats. Data are expressed as picomoles of L-DOPA per 10 min per pair of cell groups (A1C1c: caudal A1C1 subset, A1C1r: rostral A1C1 subset; A2C2c: caudal A2C2 subset; A2C2r: rostral A2C2 subset). n = 5 in each group.

P < 0.05; statistically significant differences between values in the sham-operated and CSNT groups.

DISCUSSION

In the rat, increased breathing in response to hypoxia is mediated principally by the carotid bodies (Sapru & Krieger, 1977). CSNT induces a striking decrease in the HVR (Olson et al. 1988). However, it has been shown that the initial loss of HVR is followed by progressive recovery within the following weeks (Bisgard et al. 1976; Smith & Mills, 1980; Martin-Body et al. 1985, 1986). Because the catecholaminergic cell groups of the brainstem play a prominent part in the modulation of the chemoreflex response to hypoxia, we hypothesised that CSNT may produce functional changes in the catecholaminergic medullary areas, in association with ventilatory recovery after CSNT. To test this hypothesis, we looked at the possibility that ventilatory and/or neurochemical modifications of the chemoreflex pathway might occur during the reorganisation process.

We found that the ventilatory pattern during recovery of the HVR in the CSNT rats was different from that in the sham-operated rats. The CSNT rats exhibited a higher VT, but no increase in f in response to acute hypoxia. Recovery of O2 chemosensitivity was associated with substantial changes in TH activity in the medullary areas involved in the chemoreflex responses to hypoxia.

Recovery of resting minute ventilation

In the rat, denervation of the carotid sinus has been found to be followed by a very small increase in arterial blood pressure, which indicates an absence of functional barosensory fibres in the carotid sinus nerve in this species (Krieger, 1964, 1970). Chemoreceptor afferents have been found in the aortic nerve of rats (Brophy et al. 1999), but their contribution to chemoreflex breathing is minor, and thus it is generally accepted that the bulk of peripheral arterial chemosensory inputs to the brainstem is conveyed by the carotid sinus nerve (Sapru & Krieger, 1977). In the present study, transection of the carotid sinus nerve led to hypoventilation 2 days after surgery, mainly due to a decrease in VT. The effect of chemodenervation on resting V̇E in rats has been previously observed (Favier & Lacaisse, 1978; Cardenas & Zapata, 1983; Martin-Body et al. 1985), and it has been shown that carotid bodies positively stimulate respiration in awake animals. In the present study, the resting V̇E was progressively restored, since no difference could be detected between CSNT and sham-operated rats 6 days after surgery.

Different studies have been carried out on the ventilatory effect of carotid sinus nerve section (Zapata et al. 1976; Favier & Lacaisse, 1978; Majumdar et al. 1982, 1983; Martin-Body et al. 1985, 1986; Martin-Body, 1988) using various surgical techniques, i.e. cutting (Favier & Lacaisse, 1978; Martin-Body et al. 1985, 1986; Martin-Body, 1988), transecting (Majumdar et al. 1982, 1983), crushing (Zapata et al. 1976) or ligaturing (Favier & Lacaisse, 1978). In the present study, in order to eliminate any possible regeneration of the chemosensory fibres, the carotid sinus nerves were bilaterally transected at the point of branching off from the glossopharyngeal nerve, and at the cranial pole of the carotid body.

The haematocrit and haemoglobin levels at 15 days and 45 days after surgery were not found to be affected by CSNT, suggesting that the rats were not chronically hypoxaemic. The chronic nature of this experiment, along with the constraints imposed during studies on awake animals and the relatively small blood volume of the rat, meant that it was difficult to make repeated blood gas measurements. Moreover, it is well known that repeated blood sample recovery can modify blood parameters such as volaemia and tissue hypoxia, which are related to anaemia. It has been shown that hypoventilation following carotid chemodenervation does not change arterial O2 pressure (Favier & Lacaisse, 1978), or produces only a small decrease in arterial PO2 (Pa,CO2; 5 Torr: Olson et al. 1988; 5–6 Torr: Matsuoka et al. 1994). This level of hypoxaemia is low, and would not significantly alter ventilatory output, given the threshold of arterial O2 pressure that triggers significant hyperventilation or an increase in the chemosensory firing rate. Furthermore, carotid chemodenervation produces either no change in Pa,CO2 or arterial pH (Matsuoka et al. 1994) or else a small increase in Pa,CO2 (4 Torr: Favier & Lacaisse, 1978; 8 Torr: Olson et al. 1988). In our study, the CSNT rats hypoventilated within the first 10 days following surgery, following which the resting ventilation was unaltered, thus showing that even if there was an increase in the Pa,CO2 level, it would not have contributed significantly to the ventilatory output. We therefore concluded that the small differences in arterial blood gas levels between sham-operated and CSNT rats made only a minor contribution, if any, to the difference in ventilation between the two groups of rats.

Recovery of the hypoxic ventilatory response

Two days after surgery, a considerable reduction in the HVR was observed in the CSNT rats. This result is in agreement with previous studies (Sapru & Krieger, 1977; Cardenas & Zapata, 1983), which suggests that the carotid bodies are the main peripheral chemoreceptors in the rat. The modest HVR remaining after CSNT was probably produced by secondary glomus tissue. In the rat, an absence of functional aortic chemoreceptors has been clearly demonstrated (Sapru & Krieger, 1977). On the other hand, a part of the HVR has been attributed to abdominal chemoreceptors, although their contribution to overall chemoreception appears to be very small (Martin-Body et al. 1985). A number of carotid body-like organs (paraganglia) have been found near the glossopharyngeal, vagus and sympathetic nerves in rats (McDonald & Blewett, 1981). All these minute organs are composed of tightly packed collections of small cells surrounded by a system of thin-walled blood vessels. The paraganglia may participate in the HVR, but the physiological component of these chemoreceptors is difficult to assess, due principally to their very small size, and to the fact that they are scattered along the trunk arterial blood vessels.

In the present study, the CSNT rats began to show a similar HVR to the sham-operated rats 45 days after surgery. Earlier studies on chemodenervated ponies (Bisgard et al. 1976), cats (Smith & Mills, 1979) and rats (Martin-Body et al. 1985) showed an absence of hypoxic ventilation and a recovery of HVR to a level similar to that of the control animals. The time course and magnitude of ventilatory recovery vary according to the species. In anaesthetised cats, complete recovery occurred 260–315 days after carotid body resection (Smith & Mills, 1979). In ponies, a modest recovery (30–40%) was observed 22 months after carotid body resection (Bisgard et al. 1980). In rats, Martin-Body et al. (1986) observed a partial (55%) recovery of the HVR, under severe hypoxic conditions (50–60 mmHg) 3 weeks after carotid body denervation, but no further significant evolution until 27 weeks. The difference in recovery levels between this latter study and the present one may be explicable in terms of gender differences, given that Martin-Body et al. (1986) used females. This is of importance because female rats have a higher HVR than males (Mortola & Saiki, 1996), probably due to the stimulatory influence of ovarian hormones on peripheral arterial chemosensitivity (Tatsumi et al. 1997). In our study, moreover, different groups of rats were used for ventilation at each stage after surgery in order to avoid possible hypoxic habituation, which was not the case of the study carried out by Martin-Body et al. (1986).

Components of ventilatory recovery

A significant finding of this study is the difference in HVR patterns after recovery between the CSNT and the sham-operated rats. In the sham-operated rats, the HVR was principally a function of increases in f, whereas the f response was blunted in the CSNT rats. On the other hand, VT was the main component of HVR recovery in the CSNT group, and after 10 days it reached a higher level than in the sham-operated group. A minor delayed response in f was apparent after 45 days in the CSNT group.

It has been suggested that the recovery of chemoreflex pathways originates in a central reorganisation of the medullary structures responsible for respiratory control, with a resulting increase in the processing of chemosensory inputs from secondary glomus tissue (Majumdar et al. 1982, 1983; Martin-Body et al. 1985, 1986; Martin-Body, 1988; Eugenin et al. 1990). Martin-Body (1988) demonstrated that in adult rats a depression of f by hypoxia after carotid sinus denervation requires the integrity of a region at or immediately above the intercollicular level, and in contrast, the stimulation of VT by hypoxia is markedly dependent upon precollicular structures (Martin-Body, 1988). More recent studies have indicated the existence of direct hypoxic stimulation of the neurones located in brain regions such as the rostro-ventrolateral medulla (Nolan & Waldrop, 1993, 1996; Sun & Reis, 1994), the hypothalamus (Nolan et al. 1995) and the red nucleus (Waites et al. 1996). In the present study, the considerable alteration of the HVR pattern following CSNT would suggest a strategy that is progressively developed to compensate for reduced oxygen availability. VT is considered to be a relatively direct indicator of the output of the brainstem control system to the respiratory motor neurones (Clark & Euler, 1972; Bradley et al. 1975). Therefore, the gradual increase in VT associated with the recovery of chemosensitivity suggests the recruitment of further phrenic motor neurones (Bartoli et al. 1975).

Neurochemical reorganisation of the chemoreflex pathway

Most previous studies have suggested a central origin of HVR recovery on the basis of ventilatory measurements. Neuroanatomical evidence for central reorganisation at the brainstem level has been provided by just one study (Majumdar et al. 1983) where carotid body denervation in cats was followed by a degenerative phase (4–15 days), then a phase of axonal sprouting (56–91 days).

Our study included a neurochemical investigation of the catecholaminergic medullary areas involved in the chemoreflex pathway. Like Majumdar et al. (1982), we chose two time points, the first 15 days after CSNT, during HVR recovery, and the second 90 days after CSNT, i.e. after complete HVR recovery and putative central reorganisation. Fifteen days after surgery, there was found to be a decrease in TH activity in the A2C2c and A6 brainstem cell groups. Reduced TH activity in A2C2c could be due to degeneration of the carotid sinus nerve terminals, as has been found in the cat after carotid body denervation (Majumdar et al. 1983). The carotid body may play a tonic role in the NTS, given that the carotid afferent inputs significantly stimulate minute respiration. The A6 cell group (locus coeruleus), which is involved in arousal and behavioural activity, is known to be affected by environmental modifications (Valentino et al. 1993), and its connections with the NTS may explain the decrease in TH activity that we found. Ninety days after surgery, on the other hand, ventilatory recovery was associated with an increase in TH activity in the A2C2c, A6, A1C1c and A5 cell groups of the CSNT rats.

Although the present study was not designed to assess the direct role of medullary noradrenergic neurones in the development of ventilatory recovery following CSNT, the short- and long-term evolution of TH activity after CSNT can be considered as a neuronal marker of the central reorganisation that leads to the new HVR pattern, for at least four reasons. (i) TH changes were restricted to the medullary cell groups involved in the chemoreflex pathway, i.e. the A2C2c subset, A5, A6, and the A1C1c subset (Guyenet et al. 1993; Schmitt et al. 1994; Smith et al. 1995). Worth noting is the lack of TH alteration in the A1C1r (rostro-ventrolateral medulla) and A2C2r (rostro-dorsomedial medulla) subsets, both of which are catecholaminergic areas involved in the central integration of barosensitive inputs and the control of sympathetic baroreflex responses. (ii) Noradrenaline in the caudal dorsomedial medulla and caudal ventrolateral medulla has been found to play an inhibitory role in the neuromodulation of ventilatory control and chemoreflex pathway (Bianchi et al. 1995; Denavit-Saubié & Foutz, 1997). (iii) In the present study, opposite changes in catecholaminergic neuronal activity were observed in the CSNT rats before and after complete HVR recovery. During the early phase of development of recovery, a low TH activity was associated with a gradual increase in the VT response to hypoxia, but after complete HVR recovery the TH activity was higher in the sham-operated rats. (iv) Again in the present study, after complete HVR recovery the A5 cell group exhibited the highest increase in TH activity (Table 2). At the same time, the CSNT rats showed an increase in TE, concomitant with a depressed f response to hypoxia. Interestingly, direct activation of the A5 neurones induces an increase in TE and a decrease in f (Dick et al. 1995). Taken together, these results suggest an increase in the excitability of the A5 neurones after HVR recovery, with a possible central involvement of the A5 cell group in the new chemoreflex pathway.

Potential mechanisms explaining the hypoxic ventilatory response recovery

There are a number of mechanisms that could explain the reorganisation of the medullary catecholaminergic areas associated with HVR recovery. For example, ventilatory recovery associated with increased TH activity in A2C2c cells could be due to aortic body reinforcement. Thus, aortic body afferents may have occupied the vacant carotid body postsynaptic sites due to the initial degeneration of the central carotid sinus nerve terminals that has been observed after CSNT (Majumdar et al. 1982). It is also possible that the medullary catecholaminergic neurones developed or increased their capacity to be directly activated by low O2, as has been found with the neurones in the rostro-ventrolateral medulla (Nolan & Waldrop, 1993, 1996; Sun & Reis, 1994). Other possible mechanisms for HVR recovery include afferent inputs from other putative central O2 sensors, which could increase their O2 sensitivity and/or their capacity to activate the chemoreflex pathway after HVR recovery following CSNT. Indeed it is known that caudal hypothalamic neurones can facilitate the respiratory response to hypoxia independently of peripheral chemosensory inputs (Horn & Waldrop, 1998).

In summary, the present data indicate a progressive and profound reorganisation of the HVR pattern after irreversible interruption of the carotid sinus afferent pathway, associated with changes in the neurochemical activity of the medullary catecholaminergic cell groups involved in the chemoreceptor pathway.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the CNRS (UMR CNRS 5578) and the Région Rhône-Alpes (Grant: ‘Souffrance Foetale et Maturation neuronale’). J. C. Roux has held a fellowship from the Région Rhône-Alpes. We are most grateful to Jérôme Zobel for his technical assistance and John Doherty for revision of English.

References

- Bartlett D, Jr, Tenney SM. Control of breathing in experimental anemia. Respiration Physiology. 1970;10:384–395. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(70)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli A, Cross BA, Guz A, Huszczuk A, Jeffries R. The effect of varying tidal volume on the associated phrenic motoneurone output: studies of vagal and chemical feedback. Respiration Physiology. 1975;25:135–155. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(75)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Denavit-Saubié M, Champagnat J. Central control of breathing in mammals: neuronal circuitry, membrane properties, and neurotransmitters. Physiological Reviews. 1995;75:1–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Forster HV, Klein JP. Recovery of peripheral chemoreceptor functions after denervation in ponies. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1980;49:964–970. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.6.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Forster HV, Orr JA, Buss DD, Rawlings CA, Rasmussen B. Hypoventilation in ponies after carotid body denervation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1976;40:184–190. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley GW, van Euler C, Marttila I, Roos B. A model of the central and reflex inhibition of inspiration in the cat. Biological Cybernetics. 1975;19:105–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00364107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy S, Ford TW, Carey M, Jones JF. Activity of aortic chemoreceptors in the anaesthetized rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:821–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.821ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas H, Zapata P. Ventilatory reflexes originated from carotid and extracarotid chemoreceptors in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1983;244:R119–125. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.1.R119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Davis JN, Kehr W, Lindqvist M, Atack CV. Simultaneous measurement of tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylase activities in brain in vivo using an inhibitor of the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1972;275:153–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00508904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagnat J, Denavit-Saubié M, Henry JL, Leviel V. Catecholaminergic depressant effects on bulbar respiratory mechanisms. Brain Research. 1979;160:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90600-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FJ, Von Euler C. On the regulation of depth and rate of breathing. The Journal of Physiology. 1972;222:267–295. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles SK, Dick TE. Neurones in the ventrolateral pons are required for post-hypoxic frequency decline in rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:79–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denavit-Saubié M, Foutz A. Neuropharmacology of respiration. In: Miller AD, Bianchi AL, Bishop BP, editors. Neural Control of the Respiratory Muscles. New York: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Coles SK, Jodkowski JS. A ‘pneumotaxic centre’ in ventrolateral pons of rats. In: Trouth O, Millis R, Kiwell-Schöne H, Schläfke M, editors. Ventral Brainstem Mechanisms and Control Functions. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. pp. 723–737. [Google Scholar]

- Errchidi S, Monteau R, Hilaire G. Noradrenergic modulation of the medullary respiratory rhythm generator in the newborn rat: an in vitro study. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;443:477–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin J, Larrain C, Zapata P. Functional recovery of the ventilatory chemoreflexes after partial chronic denervation of the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Research. 1990;523:263–272. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier R, Lacaisse A. O2 chemoreflex drive of ventilation in the awake rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;74:411–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JC, Katz DM. The central organisation of carotid body afferent projections to the brainstem of the rat. Brain Research. 1992;572:108–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90458-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H, Bonora M. Ventilatory and metabolic responses to cold and hypoxia in intact and carotid body-denervated rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1992;73:847–854. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Koshiya N, Huangfu D, Verberne AJ, Riley TA. Central respiratory control of A5 and A6 pontine noradrenergic neurons. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:R1035–1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.R1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn EM, Waldrop TG. Suprapontine control of respiration. Respiration Physiology. 1998;114:201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley GD, Martin-Body RL, Dawson NJ, Sinclair JD. Brain stem projections of the glossopharyngeal nerve and its carotid sinus branch in the rat. Neuroscience. 1987;22:237–250. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger EM. Neurogenic hypertension in rat. Circulation Research. 1964;15:511–521. doi: 10.1161/01.res.15.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger EM. The acute phase of neurogenic hypertension in rat. Experentia Basel. 1970;26:628–629. doi: 10.1007/BF01898727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DM, Blewett RW. Location and size of carotid body-like organs (paraganglia) revealed in rats by the permeability of blood vessels to Evans blue dye. Journal of Neurocytology. 1981;10:607–643. doi: 10.1007/BF01262593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Mills E, Smith PG. Degenerative and regenerative changes in central projections of glossopharyngeal and vagal sensory neurons after peripheral axotomy in cats: a structural basis for central reorganization of arterial chemoreflex pathways. Neuroscience. 1983;10:841–849. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Smith PG, Mills E. Evidence for central reorganisation of ventilatory chemoreflex pathways in the cat during regeneration of visceral afferents in the carotid sinus nerve. Neuroscience. 1982;7:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)91136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Body RL. Brain transections demonstrate the central origin of hypoxic ventilatory depression in carotid body-denervated rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;407:41–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Body RL, Robson GJ, Sinclair JD. Respiratory effects of sectioning the carotid sinus glossopharyngeal and abdominal vagal nerves in the awake rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;361:35–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Body RL, Robson GJ, Sinclair JD. Restoration of hypoxic respiratory responses in the awake rat after carotid body denervation by sinus nerve section. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;380:61–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka T, Dotta A, Mortola J. Metabolic response to ambiant temperature and hypoxia in sinoaortic-denervated rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:R387–391. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.2.R387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortola JP, Saiki C. Ventilatory response to hypoxia in rats: gender differences. Respiration Physiology. 1996;106:21–34. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan PC, Dillon GH, Waldrop TG. Central hypoxic chemoreceptors in the ventrolateral medulla and caudal hypothalamus. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1995;393:261–266. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1933-1_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan PC, Waldrop TG. In vivo and in vitro responses of neurons in the ventrolateral medulla to hypoxia. Brain Research. 1993;630:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan PC, Waldrop TG. In vitro responses of VLM neurons to hypoxia after normobaric hypoxic acclimatization. Respiration Physiology. 1996;105:23–33. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EB, Vidruk EH, Dempsey JA. Carotid body excision changes ventilatory control in awake rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1988;64:666–671. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.2.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Brownstein MJ. Maps and Guide to Microdissection of the Rat Brain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sapru HN, Krieger AJ. Carotid and aortic chemoreceptor function in the rat. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1977;42:344–348. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt P, Soulier V, Pequignot JM, Pujol JF, Denavit-Saubié M. Ventilatory acclimatization to chronic hypoxia: relationship to noradrenaline metabolism in the rat solitary complex. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;477:331–337. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Buller KM, Day TA. Role of ventrolateral medulla catecholamine cells in hypothalamic neuroendocrine cell responses to systemic hypoxia. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;12:7979–7988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07979.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PG, Mills E. Physiological and ultrastructural observations on regenerated carotid sinus nerves after removal of the carotid bodies in cats. Neuroscience. 1979;4:2009–2020. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PG, Mills E. Restoration of reflex ventilatory response to hypoxia after removal of carotid bodies in the cat. Neuroscience. 1980;5:573–580. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier V, Cottet-Emard JM, Pequignot J, Hanchin F, Peyrin L, Pequignot JM. Differential effects of long-term hypoxia on norepinephrine turnover in brain stem cell groups. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1992;73:1810–1814. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK, Reis DJ. Hypoxia selectively excites vasomotor neurons of rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:R245–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.1.R245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Pickett CK, Jacoby CR, Weil JV, Moore LG. Role of endogenous female hormones in hypoxic chemosensitivity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;83:1706–1710. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL, Page ME. The locus coeruleus as a site for integrating corticotropin-releasing factor and noradrenergic mediation of stress responses. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;697:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites BA, Ackland GL, Noble R, Hanson MA. Red nucleus lesions abolish the biphasic respiratory response to isocapnic hypoxia in decerebrate young rabbits. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;495:217–225. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata P, Stensaas LJ, Eyzaguirre C. Axon regeneration following a lesion of the carotid nerve: electrophysiological and ultrastructural observations. Brain Research. 1976;113:235–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90939-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]