Abstract

Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) is alternatively spliced generating eight isoforms that only differ in the length of their cytoplasmic domain. Multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 are present in the endothelium and their expression levels are regulated during vascular development and angiogenesis. However, the functional significance of PECAM-1 isoforms during these processes remains largely unknown. We recently showed that mouse brain endothelial (bEND) cells prepared from PECAM-1-deficient (PECAM-1-/-) mice differ in their cell adhesive and migratory properties compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells. Here we demonstrate that the restoration of PECAM-1 expression in these cells affects their adhesive and migratory properties in an isoform-specific manner. Expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1, the predominant isoform present in the mouse endothelium, in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells activated MAPK/ERKs, disrupted adherens junctions, and enhanced cell migration and capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel. In contrast, expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells had minimal effects on their activation of MAPK/ERKs, migration and capillary morphogenesis. The effects of PECAM-1 on cell adhesive and migratory properties were mediated in an isoform-specific manner, at least in part, through its interactions with intracellular signaling proteins, including SHP-2 and Src. These results suggest that the impact of PECAM-1 on EC adhesion, migration, and capillary morphogenesis is modulated by alternative splicing of its cytoplasmic domain.

Keywords: CD31, Alternative splicing, Signal transduction, Cell migration, Cell adhesion, MAPK/ERKs, SHP-2, Src

Introduction

Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31) is a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on endothelial cells (EC), platelets, and a subset of hematopoietic cells (Ilan and Madri, 2003; Newman and Newman, 2003; Sheibani and Frazier, 1999). PECAM-1 is a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and consists of six immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains in its extracellular portion, a 19-residue transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail of variable length due to alternative splicing (Albelda et al., 1990; Kirschbaum et al., 1994; Newman et al., 1990; Newman and Newman, 2003; Sheibani and Frazier, 1999). PECAM-1 mediates homophilic binding on adjacent cells through its amino-terminal Ig domains and, in EC, generally localizes to sites of cell-cell contact (Sun et al., 1996). In fact, PECAM-1 is required for endothelial cell-cell interactions and monolayer formation in culture (Albelda et al., 1990). Antibodies to PECAM-1 block capillary morphogenesis of EC in Matrigel (Sheibani et al., 1997) and inhibit angiogenesis in vivo (DeLisser et al., 1997). PECAM-1 antibodies also block transendothelial migration of leukocytes (Muller, 1995; Muller et al., 1993). The functions of PECAM-1 in inflammation and angiogenesis are further emphasized by the defects observed in PECAM-1-deficient (PECAM-1-/-) mice. PECAM-1-/- mice exhibit abnormalities in their inflammatory and angiogenesis responses to foreign body challenges (Duncan et al., 1999; Graesser et al., 2002; Schenkel et al., 2004; Solowiej et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2001). Therefore, expression of PECAM-1 in EC and its functions are important during angiogenesis and inflammation. However, the molecular mechanisms that mediate PECAM-1 activities in the endothelium require further investigation.

The cytoplasmic domain of PECAM-1 is encoded by seven exons (exons 10-16). In mice, three of these exons (exons 12, 14 and 15) undergo alternative splicing (Sheibani et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1995). The splicing of these exons generates multiple isoforms (8 in mice), whose expression levels is regulated during vascular development and angiogenesis, suggesting that the presence of certain exons may influence PECAM-1 adhesive and migratory functions (Sheibani et al., 1999). In fact, isoforms with exon 14 promote heterophilic, while isoforms lacking exon 14 promote homophilic cell-cell interactions when expressed in L-cells (Sun et al., 1996; Yan et al., 1995). Furthermore, PECAM-1 undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation in response to a variety of stimuli including shear stress and adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins (Lu et al., 1996; Osawa et al., 1997). Tyrosine residues in exons 13 and 14 impact PECAM-1 functions (Gratzinger et al., 2003a; O’Brien et al., 2004; Sheibani et al., 2000) and are thought to be part of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) (Newman, 1999). Phosphorylation of these tyrosine residues is important for PECAM-1 interactions with downstream signaling effectors, such as the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 and Src kinase, through their Src homology-2 (SH2) domains (Cao et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 1997a; Lu et al., 1997; Masuda et al., 1997). These interactions may lead to the activation of multiple signaling pathways, thereby impacting EC survival, proliferation, adhesion, and migration (Jackson et al., 1997b; Sagawa et al., 1997; Wang and Sheibani, 2006). However, the identity of these pathways and the role PECAM-1 isoforms may play in the regulation of these pathways are not well understood. This is further complicated by the fact that multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 are expressed in EC and vascular beds of different tissues (Sheibani et al., 1999; Wang and Sheibani, 2002). The majority of previous studies have used non-EC lines to examine the migratory and adhesive properties of PECAM-1 isoforms. These studies have been useful in defining binding properties of different isoforms, but have not addressed the role these interactions may play in EC.

Full-length PECAM-1 represents a low percentage of all the isoforms expressed in the mouse endothelium (Sheibani et al., 1999), while isoforms lacking exons 14 and 15 (Δ14&15) or 15 (Δ15) represent t he major PECAM-1 isoforms. Here we used brain endothelial (bEND) cells prepared from PECAM-1-/- mice to study the role of a specific PECAM-1 isoform in regulation of EC adhesion, migration, and capillary morphogenesis. The expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoform resulted in enhanced activation of the MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway and loss of junctional localization of both VE-cadherin and β-catenin in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. The Δ14&15 PECAM-1-expressing cells also exhibited enhanced migration and capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel compared to vector control cells. In contrast, the expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 had minimal effects on MAPK/ERKs activity, organization of adherens junctions, migration, and capillary morphogenesis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. This is attributed, at least in part, to the recruitment and activation of SHP-2 by Δ15 PECAM-1 negatively impacting the activation of MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway. These studies represent the first evidence for PECAM-1 isoform-specific functions in brain EC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and stable DNA transfection

The wild type (PECAM-1+/+) mouse brain endothelial (bEND) cells, (obtained from W. Risau, Max Planck Institute), were generated by infection of mouse brain endothelial cells (EC) prepared from cerebral capillaries of one-week old C57BL/6 mice with a retrovirus which expresses Polyoma middle-T antigen as described previously (Montesano et al., 1990). The PECAM-1-/- bEND cells were generated using the same retrovirus to infect brain EC prepared from cerebral capillaries of one-week old PECAM-1-/- C57BL/6 mice (Wong et al., 2000). These cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10-5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and maintained in a tissue culture incubator at 37°C with 10% CO2. PECAM-1-/- bEND cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 Hygromycin vector (Invitrogen) containing cDNA for PECAM-1 isoforms Δ15, Δ14&15 or empty vector using Lipofectin as described previously (Sheibani and Frazier, 1995). The transfected cells were grown in the presence of 50 μg/ml hygromycin in regular growth medium. After 2-3 weeks of selection, approximately 60 individual clones were isolated, expanded and screened for PECAM-1 expression by Western blot and FACScan analysis. Several clones with similar levels of PECAM-1 expression were used for further analysis.

Construction of adenoviruses and transient expression of PECAM-1 isoforms in EC

For efficient transient transfections we utilized adenoviruses that express a specific PECAM-1 isoform. The PECAM-1 isoform cDNAs were obtained as Hind III/Not I fragments, blunted, and ligated with the intermediate plasmid (pShuttle; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) digested with EcoRV. The ligation was transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells (Invitrogen), and positive clones were confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing. The functionality of the constructs was further confirmed by expression and Western blotting in 293 cells. For construction of a recombinant adenovirus, pShuttle/PECAM-1 isoform was linearized by Pac I, introduced into E. coli BJ5183-AD-1 (Stratagene), which contains the viral plasmid, and the recombinant clones were screened by PmeI digestion. The isolated recombinant viral plasmid DNA was then digested with PacI to release the viral DNA. This viral DNA was then introduced into 293 cells for viral packaging and amplification. The amplified virus was then titered and used for expression studies. For adenoviral infections, 3×105 EC were plated in a 60 mm culture dish. The next day, cells were rinsed twice with serum-free medium and infected with adenoviruses encoding a specific PECAM-1 isoform or empty vector (10 particles per cell) in the presence of 30 μl of Lipofectin (Invitrogen) for 5 h. Following incubation, plates were rinsed with growth medium to remove Lipofectin solution and fed with growth medium. To confirm the effectiveness of adenoviral infection, the levels of PECAM-1 expression were analyzed by FACScan and Western blot analysis 3 days after infection. PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform were analyzed for PECAM-1 localization, migration, capillary morphogenesis, and PECAM-1’s association with intracellular signaling molecules as described below.

FACScan analysis

Monolayers of cells grown in 60 mm tissue culture dishes were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.04% EDTA and incubated with 2 ml of cell dissociation solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to remove cells from plates. Cells were washed once with DMEM containing 10% FBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml Tris-Buffered Saline (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6; TBS) with 1% goat serum for 20 min on ice. Cells were pelleted and incubated with rat anti-mouse PECAM-1 (2 μg/ml; MEC13.3; BD Pharmingen) prepared in 0.5 ml of TBS with 1% BSA for 30 min on ice. For VE-cadherin staining, cells were fixed in 0.5 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in TBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes before incubation with 2 μg/ml rabbit anti-mouse VE-cadherin (Alexis Biochemicals) prepared in 0.5 ml of TBS with 1% BSA. Following incubation, cells were washed twice with TBS/1% BSA and then incubated with appropriate FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce; diluted 1:200 in 0.5 ml of TBS containing 1% BSA) for 30 min on ice. The stained cells were washed twice with TBS containing 1% BSA, resuspended in 0.5 ml of TBS containing 1% BSA, and analyzed by FACScan caliber flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Immunoprecipitations

PECAM-1-/- bEND cells were infected with adenovirus expressing the empty vector or a specific isoform of PECAM-1 as described above and were serum-starved overnight. The next day, cells were incubated with growth medium containing 1 mM Na3OV4 for 1 h to stimulate PECAM-1 phosphorylation and stabilization of signaling complexes (Lu et al., 1996). Cells were harvested in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM each CaCl2 and MgCl2, 2% Triton X-100, 100 mM NaF, 3 mM Na3OV4, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and transferred to a microfuge tube on ice. Samples were sonicated briefly, rocked for 30 min at 4°C, centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 ×g, and cleared lysates were transferred to clean tubes. Samples were diluted with an equal volume of lysis buffer without detergent and protein concentrations were determined by the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cell lysates (500 μg protein) were immunoprecipitated with 2.5 μg PECAM-1 antibody (MEC13.3) for 2 hours at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected with goat anti-rat IgG-conjugated agarose beads (40 μl/sample; Sigma) and separated on an SDS-PAGE gel as described above. The antibodies used for Western blotting were anti-SHP-2 (Upstate Biotechnology), anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-c-Src (Santa Cruz); they were used at dilutions recommended by the supplier as described above.

Western blot analysis

To assess MAPK/ERKs activation, 1 × 105 cells were plated in 60-mm dishes and, 2 days later, cells were fed with either regular growth medium or serum-free medium to serum starve the cells for 2 additional days. Serum-starved cells were stimulated with regular serum-containing medium for 15 min. Plates were then rinsed twice with cold serum-free medium containing 1 mM Na3OV4, lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM each CaCl2 and MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mM NaF, 3 mM Na3OV4, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and transferred to a microfuge tube on ice. Samples were sonicated briefly, rocked for 30 min at 4°C, centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 ×g, and cleared lysates were transferred to clean tubes. Protein concentrations were determined by the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and aliquots corresponding to equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were mixed with 6× SDS sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 3 min, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (4-20% Tris-glycine gels; Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and processed as described previously (Sheibani and Frazier, 1998). The antibodies to phospho-ERK and total ERK were from Cell Signaling (Cambridge, MA) and used at dilutions recommended by the supplier. Similar experiments were performed with cells incubated with the SHP-2 inhibitor calpeptin (Schoenwaelder et al., 2000), at 100 μg/ml (Calbiochem) for different times.

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis

Cells (2 × 105) were plated on glass coverslips and allowed to reach confluence. Cells were washed in PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. For VE-cadherin (1:100; Alexis Biochemicals), β-catenin (1:800; Sigma), and vinculin (1:100; Sigma), cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.1% Triton X-100 to permeabilize the cells. For PECAM-1 (1:50; (Sheibani et al., 1997)) staining, once fixed, the cells were washed with PBS, then incubated in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 seconds on ice to open the cell-cell junctions. Coverslips were washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibody prepared in TBS with 1% ovalbumin at 37°C for 30 minutes. After washing with TBS, the coverslip was incubated with a 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated appropriate secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in TBS with 1% ovalbumin at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells were viewed on a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope and photographed with an AxioCam digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Chester, VA).

Cell adhesion assays

Cell adhesion assays were performed using Nunc 96-well maxisorp plates as described previously (Rothermel et al., 2005). Briefly, wells were coated with different concentrations of collagen, fibronectin, laminin, or vitronectin in TBS containing 2 mM each of CaCl2 and MgCl2 overnight at 4°C. The next day, plates were washed with TBS and blocked with 200μl of TBS Ca/Mg containing 1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were plated at 5×104 cells/well in 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 4 mg/ml BSA (pH 7.4) and allowed to adhere at 37°C in a humidified incubator for 1.5 hours. Nonadherent cells were gently washed off with TBS containing Ca/Mg, and the number of adherent cells was determined by measuring the intracellular acid phosphatase activity.

Cell migration assays

For scratch wound assays, cells (2×105) were plated in 60 mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to reach confluence (2 days). After aspirating the medium, cell monolayers were wounded using a 1 ml micropipette tip. Plates were then rinsed with PBS and fed with growth medium; wounds were observed and photographed at 0, 24, and 48h. The cell migration assays were also performed in the presence of 5-fluorouracil (10 μg/ml; Sigma) to rule out potential contributions from differences in cell proliferation. The distance migrated as percent of total distance was determined for quantitative assessments using Axiovision Software (Carl Zeiss, Chester, VA). Migration assays were also conducted in the presence of LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor; 20 μM), PD098059 (MEK-1 inhibitor; 50 μM), PP1 (Src inhibitor; 10 μM), and SB203580 (p38 inhibitor; 10 μM; Alexis Biochemicals) or appropriate vehicle control. These concentrations were determined based on dose response studies to be most effective with minimal cytotoxicity.

For transwell assays, transwell filters (Costar 3422) were placed in a 24-well dish and coated on the bottom side with 0.5 ml of 2 μg/ml of fibronectin (BD Biosciences) in PBS overnight at 4°C. The filter was rinsed with PBS and then blocked with 0.5 ml of 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) prepared in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Following blocking, the filter was rinsed with PBS, 0.5 ml of serum free DMEM medium was added to the bottom of each well and 1×105 cells in 0.1 ml of serum free medium was added to the top of each well. Each condition was done in duplicate. Following 3 hours in a 37°C tissue culture incubator, the cells and medium were aspirated and the upper side of the membrane wiped with a cotton swab. The cells that had migrated through the membrane and attached to the bottom of the filter were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The mean number of cells migrated through the filter was determined by counting ten high power fields (×100).

Three-dimensional culture of endothelial cells

Matrigel (10 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) was applied at 0.5 ml/35 mm in a tissue culture dish and incubated at 37°C for at least 30 min to harden. Cells expressing empty vector or a specific isoform of PECAM-1 were removed using trypsin-EDTA, washed with growth medium once, and resuspended at 1.5 × 105 cells per ml in growth medium. Cells (2 ml) were gently added to the Matrigel-coated plates, incubated at 37°C, monitored for 6-24 h, and photographed in digital format using a Nikon microscope. Capillaries were defined as cellular processes connecting two bodies of cells. Ten fields of cells were counted for each condition and the mean and standard deviations were determined.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between groups were evaluated with Student’s t-test (two-tailed). Mean ± S.D. is shown. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Stable expression of PECAM-1 isoforms in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells

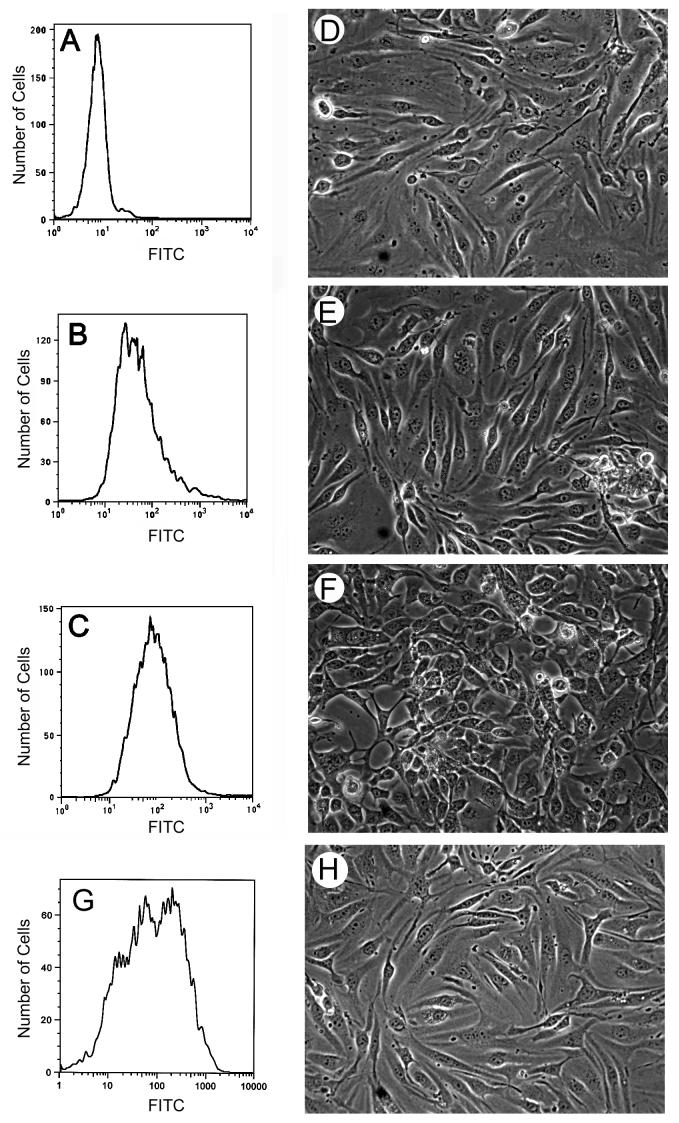

We have previously shown that PECAM-1-/- bEND cells retain the expression of EC markers with the exception of PECAM-1 (Rothermel et al., 2005). These cells exhibited reduced adhesive and migratory abilities compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells. PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 with Δ14&15 and Δ15 PECAM-1 as predominant isoforms (Sheibani et al., 1999). To determine whether expression of PECAM-1 affects EC adhesion and migration, and whether these effects are isoform specific, we transfected PECAM-1-/- bEND cells with vector, Δ15 PECAM-1, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1. Multiple stable clones were obtained and screened by Western blot analysis for PECAM-1 expression. Several clones with comparable levels of PECAM-1 were chosen for further analysis. Figures 1A-C show PECAM-1 expression of representative clones transfected with control vector, Δ15, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1, respectively. Figure 1G shows PECAM-1 expression in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing full-length PECAM-1. The expression of PECAM-1 isoforms differentially affected cell morphology (Figs. 1D-F). PECAM-1+/+ and PECAM-1-/- bEND cells both exhibited a spindle-shaped morphology and formed a tightly packed, closely apposed monolayer (Rothermel et al., 2005). Cells expressing empty vector (Fig. 1D), Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 1E), or full-length PECAM-1 (Fig. 1H) exhibited the parental morphology. However, cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 lose close cell-cell apposition and lacked the spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Expression of PECAM-1 isoforms in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. PECAM-1 expression levels were determined by FACS analysis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing vector (A), Δ15 PECAM-1 (B), and Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (C). Phase micrographs of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing vector (D), Δ15 PECAM-1 (E), and Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (F) (×100). These are examples of representative clones of stably transfected PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. Panel G and H shows expression of full-length PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells and their morphology, respectively.

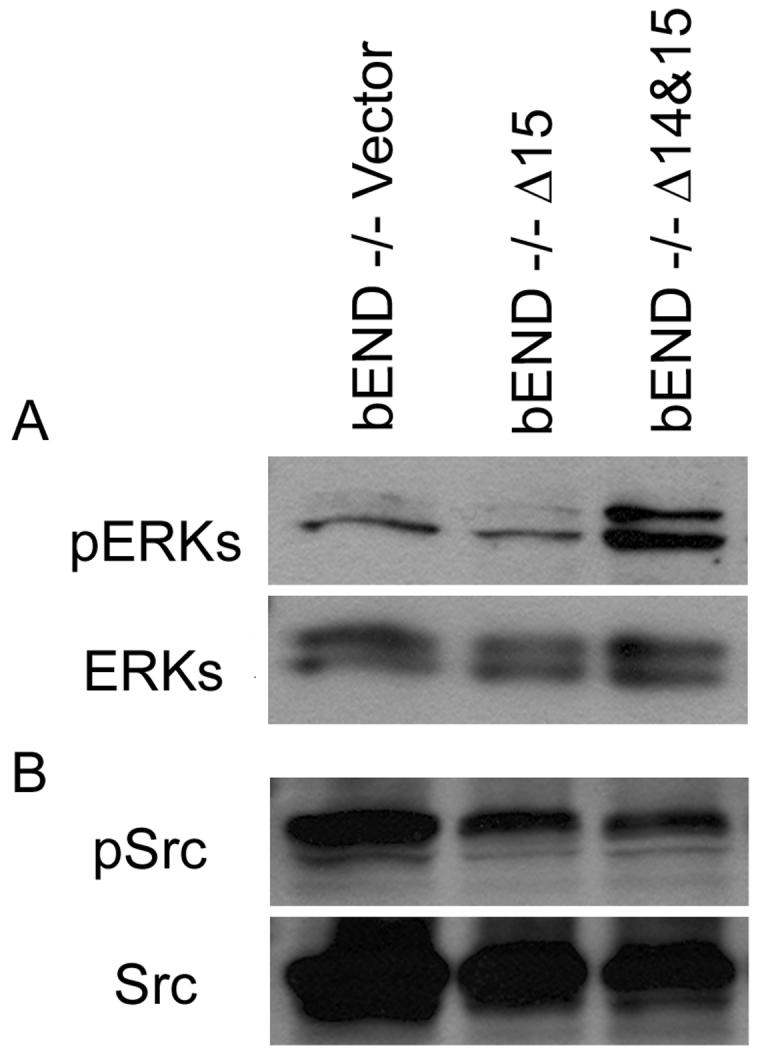

PECAM-1 isoform-specific activation of MAPK/ERKs

The MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway plays a key role in regulation of EC adhesion and migration during angiogenesis. However, the role of PECAM-1 isoforms in activation of MAPK/ERKs signaling in EC has not been well established. We determined whether expression of PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-/- EC could activate the MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway in an isoform-specific manner. Figure 2A demonstrates that expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1 resulted in sustained activation of MAPK/ERKs in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. In contrast, expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 had no effect on the levels of active MAPK/ERKs. We also examined the level of active Src (phosphorylation of tyrosine 418) in Δ15 or Δ14&15 PECAM-1-expressing cells. The Polyoma middle-T- transformed EC generally express high levels of active Src (Sheibani and Frazier, 1995). We observed high levels of active Src in cell lysates prepared from PECAM-1-/- bEND cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the expression of PECAM-1 in these cells had little or no effect on the levels of active Src (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Activation of MAPK/ERKs in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform. Cells expressing vector, Δ15 PECAM-1, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 were lysed and western blotted for activated ERKs (pERKs) as described in Methods (A). The same blot was stripped and probed for total ERKs. The level of active Src was also determined using an antibody to active Src (Y418) by Western blot analysis of total cell lysates (B). The total level of Src is shown in the lower panel. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

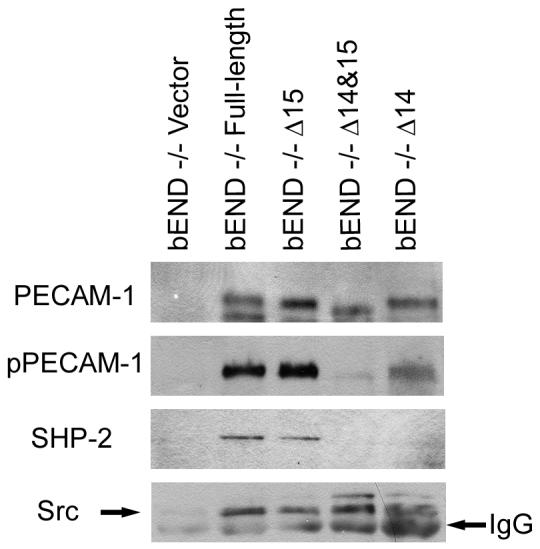

Differential association of signaling molecules with PECAM-1 isoforms

We next determined PECAM-1 isoform-specific association with the intracellular signaling proteins SHP-2 and Src in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing a specific isoform of PECAM-1. Using an antibody to the extracellular domain of PECAM-1 (MEC13.3), we immunoprecipitated various isoforms of PECAM-1 from PECAM-1-/- bEND cells infected with adenoviruses expressing a specific isoform of PECAM-1 or empty vector. We then determined the identity of the PECAM-1-associated proteins by Western blot analysis. Figure 3 shows that SHP-2 associated with Δ15 PECAM -1 but not Δ14&15 PECAM-1, thus suggesting SHP-2 association with PECAM-1 is exon 14-dependent as has been previously demonstrated (Jackson et al., 1997a). This was further supported by the ability of full-length, but not Δ14, PECAM-1 to associate with SHP-2 (Fig. 3). The interaction between SHP-2 and PECAM-1 is dependent upon phosphorylation of the tyrosines making up PECAM-1’s ITIM domains (Jackson et al., 1997a). Figure 3 also shows that PECAM-1 isoforms containing intact ITIM domains (full-length and Δ15) are highly tyrosine phosphorylated. The Δ14 and Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoforms (lacking intact ITIM domain) were phosphorylated at a much lower level. The Src kinase associated with Δ14, Δ15, Δ14&15, and full-length PECAM-1 expressed in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells (Fig. 3). Thus, the Src-PECAM-1 association, unlike SHP-2-PECAM-1 association, is exon 14-independent. Therefore, PECAM-1 association with the intracellular signaling molecules can be modulated by alternative splicing of its cytoplasmic domain.

Fig. 3.

PECAM-1 isoform-specific association with SHP-2 and Src. PECAM-1-/- bEND cells were infected with adenovirus encoding vector, Δ14, Δ15, Δ14&15, or full-length PECAM-1. The next day, the cells were serum starved for 24 hours and serum stimulated in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors for one hour to promote and stabilize PECAM-1-associated signaling complexes. PECAM-1 signaling complexes were then immunoprecipitated with antibody to PECAM-1. Immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and western blotted with antibodies to PECAM-1, phosphotyrosine, SHP-2, or Src. Please note association of SHP-2 with PECAM-1 is exon 14 dependent while its association with Src is not. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

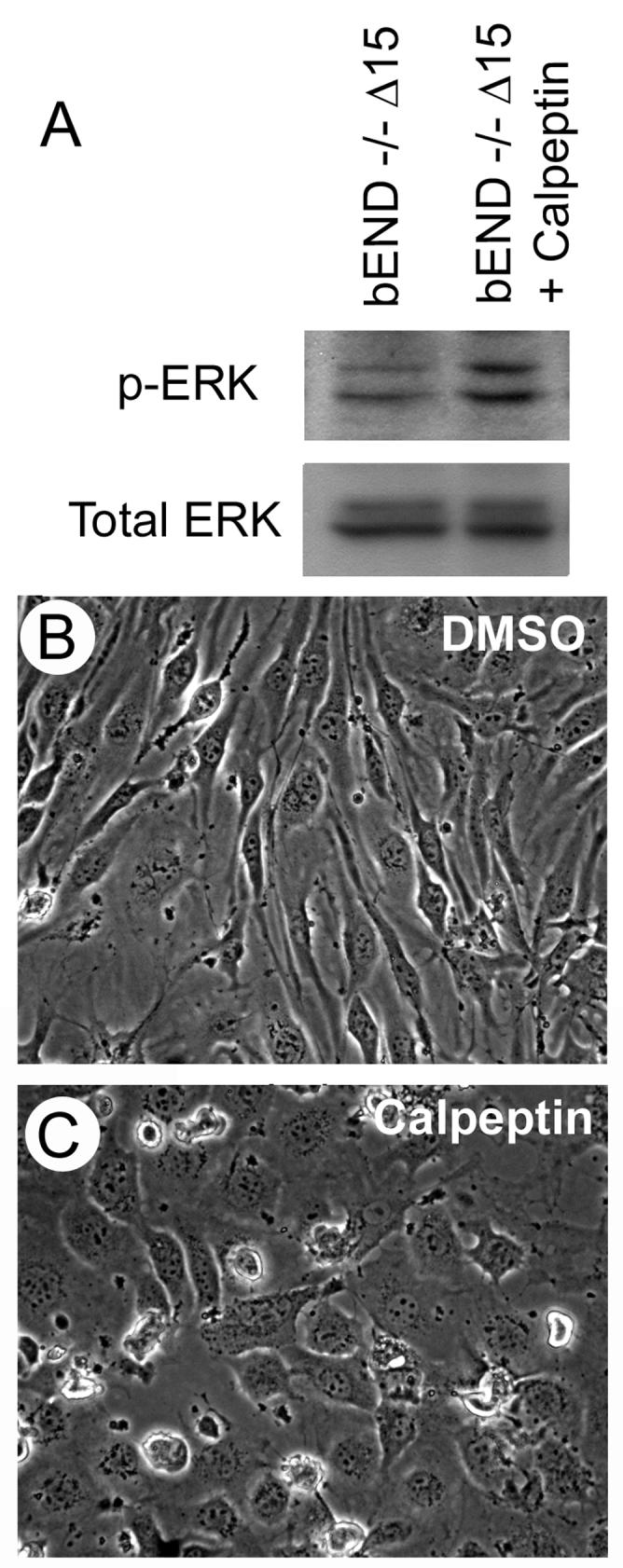

Recruitment of SHP-2 by PECAM-1 negatively impacts MAPK/ERKs activation

Molecules containing ITIM domain are generally involved in down-regulation of signaling activated by receptor kinases. The presence of ITIM domains in PECAM-1 has been proposed to fulfill such a role in PECAM-1 mediated signal transduction (Newman, 1999). We hypothesized that the recruitment of SHP-2 by PECAM-1 mediates the destabilization of signaling complexes formed upon engagement of PECAM-1 on the cell surface, and negatively impacts MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway. To test this hypothesis we incubated PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing empty vector or Δ15 PECAM-1 with calpeptin, an inhibitor of SHP-2 (Schoenwaelder et al., 2000), for different times. Figure 4A shows that inhibition of SHP-2 upon incubation of Δ15 PECAM-1 expressing cells with calpeptin for as short as 1 h, resulted in increased activation of MAPK/ERKs. Furthermore, inhibition of SHP-2 resulted in altered morphology of these cells, very similar to PECAM-1-/- cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 with increased MAPK/ERKs (Fig. 4B, C). However, the effects on the cell morphology required a longer incubation time with calpeptin (24-48 h). Incubation of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing empty vector with calpeptin had no effect on their morphology (not shown). Thus, recruitment of SHP-2 by PECAM-1 may dampen MAPK/ERKs signaling through dephosphorylation and destabilization of up-stream signaling molecules.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of SHP-2 and increased MAPK/ERKs activation in Δ15 PECAM-1 expressing cells. PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 were incubated with DMSO or calpeptin for different times. Following incubation (1h), the cells were lysed and blotted for active or total MAPK/ERKs as described in Methods (A). The phase micrograph of cells incubated with DMSO (B) or calpeptin (C) were obtained in digital format (×100) after 2 days of incubation. These experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

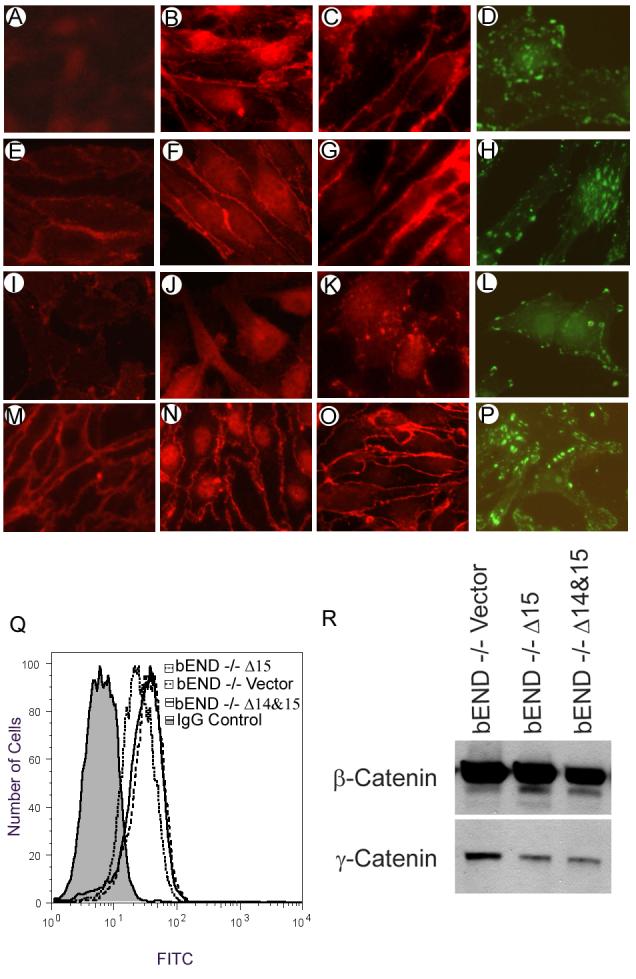

Distribution of PECAM-1 isoforms, VE-cadherin and β-catenin

PECAM-1 generally localizes to sites of cell-cell contact in EC. We next determined the intracellular localization of the PECAM-1 isoforms in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. Δ15 PECAM-1 localized at sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 5E), very similar to full-length PECAM-1 localization (not shown). In contrast, Δ14&15 PECAM-1 exhibited a diffuse staining pattern over the cell surface and lacked junctional localization (Fig. 5I), very similar to Δ14 PECAM-1 (not shown). PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1. The localization of these isoforms is shown in Figure 5M. The most highly expressed isoform of PECAM-1 in these cells is the Δ14&15 PECAM-1, which makes up approximately 40% of the total PECAM-1. This may contribute to the diffuse staining of PECAM-1 in these cells. However, some of the PECAM-1 isoforms expressed in PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells do localize to the cell junctions, including Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5M).

Fig. 5.

Cellular localization of PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, and β-catenin in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform. Immunofluorescence staining of cells expressing vector (A-D), Δ15 PECAM-1 (E-H), Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (I-L), or PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells (M-P) is shown. Cells were grown to confluence on glass coverslips and stained for PECAM-1 (A, E, I, M), VE-cadherin (B, F, J, N), or β-catenin (C, G, K, O) as described in Methods. Sub-confluent cells were stained for vinculin (D, H, L, P) to assess the distribution of focal adhesions. The VE-cadherin levels in these cells were determined by FACS analysis (Q). Cell lysates were also western blotted for expression of β-catenin and γ-catenin (R). These experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

VE-cadherin localizes to sites of cell-cell contact in confluent EC, where it mediates formation of adherens junctions and maintenance of vascular integrity. We examined whether PECAM-1 expression influences the subcellular localization of VE-cadherin. Figures 5B, F, J show immunofluorescence staining for VE-cadherin. The localization of VE-cadherin was unaffected in vector-transfected cells, which lack PECAM-1 (Fig. 5B). Expression of the Δ15 PECAM-1 also did not affect the localization of VE-cadherin (Fig. 5F). However, cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 lost junctional localization of VE-cadherin (Fig. 5J). FACS analysis demonstrated that the VE-cadherin expression level was minimally affected in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing either Δ15 or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5Q). Figure 5N shows junctional localization of VE-cadherin in PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells.

β-catenin is another molecule involved in adherens junction formation. PECAM-1 may influence the subcellular localization of β-catenin, promoting its accumulation in the nucleus (Biswas et al., 2003). The expression of PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells affected the localization of β-catenin (Figs. 4C, G, K). PECAM-1-/- bEND cells transfected with vector or Δ15 PECAM-1 had very little β-catenin in the nucleus, and β-catenin was mainly localized at sites of cell-cell contact (Figs. 5C, G). In contrast, cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM- had much less β-catenin at the sites of cell-cell contact and stronger nuclear staining (Fig. 5O). Western blot analysis of total cell lysates indicated little or no effect on the total amounts of β-catenin in these cells (Fig. 5R). Although γ-catenin expression was lower in cells expressing PECAM-1 isoforms, its level was not affected in the cells expressing a specific isoform of PECAM-1; therefore its contribution to the differences in cell-cell interactions is minimal. The localization of β-catenin in PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells is also shown (Fig. 5O). As with the PECAM-1 localization, some of the β-catenin localizes to the sites of cell-cell contacts and some in the nucleus, consistent with expression of multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 in PECAM-1+/+ cells.

Utilizing vinculin staining to visualize focal adhesions we next examined whether expression of PECAM-1 affected their organization. PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing vector control (Fig. 5D) or Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5H) formed focal adhesions that were centrally localized. In contrast, cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5L) formed focal adhesions that were localized to the cell periphery, suggesting alterations in cell adhesive and migratory properties. PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells showed a combination of these focal adhesions (Fig. 5P) consistent with expression of multiple PECAM-1 isoforms in these cells.

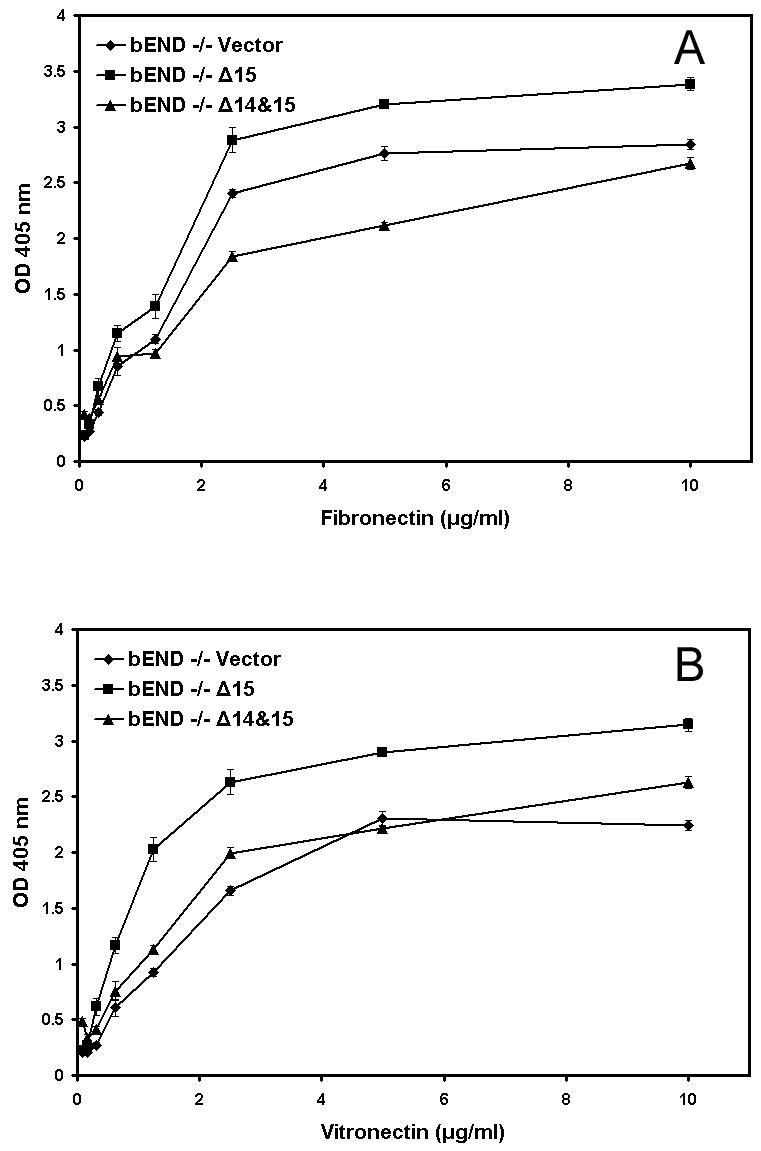

Effects of PECAM-1 isoforms on cell adhesion

We next determined whether expression of PECAM-1 affects the adhesive properties of the PECAM-1-/- bEND cells, potentially contributing to their altered morphology. We previously showed that PECAM-1-/- bEND cells were less adherent on fibronectin and vitronectin compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells (Rothermel et al., 2005). Figure 6 shows adhesion of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing vector, Δ15, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 on various concentrations of fibronectin (Fig. 6A) or vitronectin (Fig. 6A) or vitronectin (Fig. 6B). Expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells resulted in enhanced adhesion on fibronectin and vitronectin compared to vector control cells, while expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1 somewhat lowered the adhesion of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells to fibronectin, but did not significantly affect EC adhesion to vitronectin. None of the cells adhered to collagen or laminin (data not shown). Thus, regulation of cell adhesion by PECAM-1 expression is isoform-specific.

Fig. 6.

Adhesion of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform to various extracellular matrix proteins. Cells expressing vector, Δ15 PECAM-1, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1, were plated in 96-well plates coated with different concentrations of fibronectin (A) or vitronectin (B) and the number of adherent cells were determined as described in Methods. Please note a significant increase in adhesion of cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 to fibronectin and vitronectin (N=3; P< 0.05). None of the cells adhered to type I collagen or laminin (not shown). These experiments were repeated twice with two different clones of each cell line with similar results.

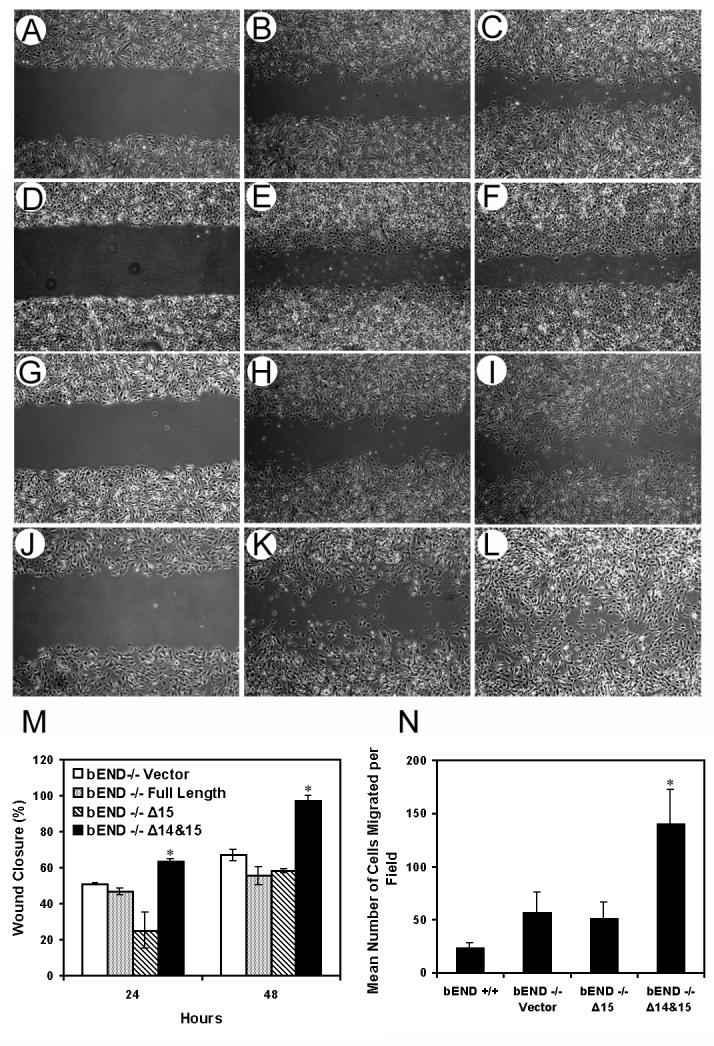

Effects of PECAM-1 isoforms on cell migration

The PECAM-1-/- bEND cells are less migratory compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells in scratch wound assays (Rothermel et al., 2005). To determine whether PECAM-1 expression affects EC migration, we tested the ability of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing vector, Δ15 PECAM-1, or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 to migrate and close a wound. Figure 7 shows that cells expressing empty vector (Figs. 7A-C), or Δ15 (Figs.7G-I) migrated similar to PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. Cells expressing vector closed approximately 51% of the wounded area by 24 h (Fig. 7B) and 67% by 48 h (Fig. 7C). Cell expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 closed approximately 25% of the wounded area by 24 h (Fig. 7H) and only 58% by 48h (Fig. 7I). In contrast, cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 migrated significantly faster, closing approximately 61% of the wound by 24 h (Fig. 7K; P < 0.05, sample vs. vector), and by 48h, cells covered most of the wounded area (Fig. 7L). We also examined the migration of cells expressing full-length PECAM-1. Cells expressing full-length PECAM-1 migrated similar to vector and Δ15 PECAM-1 cells, closing approximately 47% of the wounded area by 24 h (Fig. 7E) and 55% by 48 h (Fig. 7F). Similar results were observed in the transwell migration assay; more cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 migrated across the fibronectin-coated membrane than cells expressing either vector or Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 7N). Thus, expression of PECAM-1 affects EC migration in an isoform-specific manner.

Fig. 7.

Migration of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform. Cells expressing vector (A-C), full-length PECAM-1 (D-F), Δ15 PECAM-1 (G-I), or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (J-L) were grown to confluence in 60 mm plates and wounded as described in Methods. Wound closure was monitored at 0, 24, and 48 h and photographed in digital format. Bars in (M) are the mean distance migrated as a percent of total distance ± SD. Cell migration was also assessed using a transwell migration assay (N) as described in Methods. Please note PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 migrate significantly faster compared to cells expressing empty vector or Δ15 PECAM-1 (n=15; * P < 0.05). These experiments were repeated four times with two different clones of each cell line with similar results.

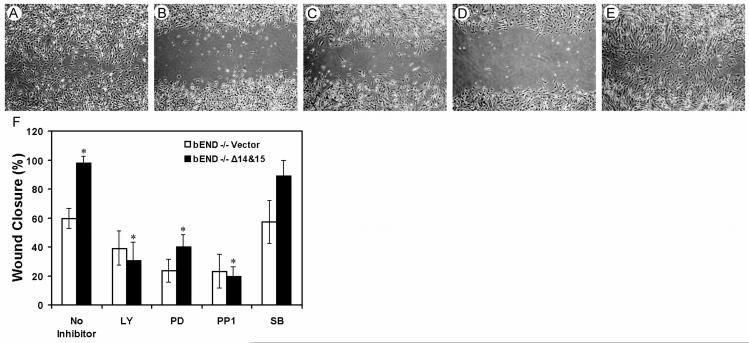

To determine whether sustained activation of MAPK/ERKs is essential for Δ14&15 PECAM-1-mediated enhanced migration of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells, we assessed their migration in the presence of PD098059, an inhibitor of MEK-1 and MAPK/ERKs. Figure 8A shows that PECAM-1-/- bEND cells that express Δ14&15 PECAM-1 migrate and close the wound after 48 h. However, incubation of these cells in the presence of PD098059 blocked their ability to migrate and close the wound (Fig. 8C). Thus, the sustained activity of MAPK/ERKs is essential for enhanced migration of Δ14&15 PECAM-1-expressing cells. Furthermore, inhibition of PI3K (LY294002; Fig. 8B) or Src (PP1; Fig. 8D) also inhibited Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoform-mediated migration, while inhibition of p38 MAPK (SB203580; Fig. 8E) had little or no effect on their migration. The quantification of these data is shown in Fig. 8F. The basal cell migration of all the EC used here was also diminished in the presence of these inhibitors and was considered in our determinations.

Fig. 8.

Enhanced migration of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 is dependent on MAPK/ERKs activity. Scratch wound assays were performed on PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 as described in Methods. Photographs shown are at 48 h post wounding. Cells were incubated with medium containing solvent control, DMSO (A), the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (B), the MEK-1 inhibitor PD098059 (C), the Src inhibitor PP1 (D), or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (E). Panel F shows the mean distance migrated as a percent of total distance ± SD. The data were compared to basal inhibition of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing empty vector. The inhibition of cell migration in the presence of LY, PD, and PP1 was significant (n=6; * P < 0.05), while the inhibition of cell migration in the presence of SB was not (n=6; P> 0.05). These experiments were repeated twice with different batches of inhibitors and in the presence or absence of 5-fluorouracil with similar results.

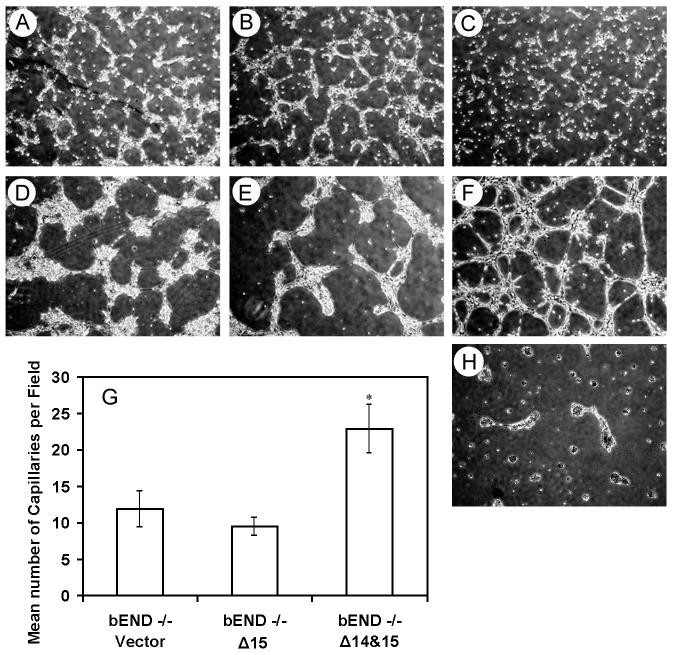

Effects of PECAM-1 isoforms on EC capillary morphogenesis

Antibodies to PECAM-1 block EC capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel (Sheibani et al., 1997) and corneal neovascularization in vivo (DeLisser et al., 1997). PECAM-1-/- bEND cells fail to undergo extensive capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel (Rothermel et al., 2005). We next determined whether expression of PECAM-1 affects the ability of these cells to undergo capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel. The vector or Δ15 PECAM-1-transfected cells began to organize into clusters of cells after 6 h in Matrigel (Figs. 9A, B) and by 24 h they formed larger cell aggregates with few processes between them (Figs. 9D, E). In contrast, PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 formed less extensive cell aggregates at 6 h in Matrigel and organized into an extensive capillary-like network by 24 h (Figs. 9C, F). Longer incubation of these cells did not further enhance their organization in Matrigel. The quantitative assessments are shown in Fig. 9G. Cells expressing full-length PECAM-1 did not organize on Matrigel (Fig. 9H).

Fig. 9.

Capillary morphogenesis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells stably expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform. Cells expressing vector (A, D), Δ15 PECAM-1 (B, E), or Δ14&15 PECAM-1 (C, F) were plated on Matrigel and cultured for 6 h (A-C) or 24 h (D-F). Longer incubation of cells did not further influence their ability to organize on Matrigel. The data in panel G are the mean number of capillaries per field ± SD. Please note extensive organization of cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 compared to cells expressing Δ15 PECAM -1 or vector (n=10; * P < 0.05). Panel H shows PECAM-1-/- cells, which were infected with adenovirus expressing full-length PECAM-1 and plated on Matrigel for 24 h, which fail to form a capillary-like network. These experiments repeated four times with similar results.

Discussion

Murine PECAM-1 mRNA undergoes alternative splicing generating eight isoforms. The expression levels of these isoforms are differentially regulated during vascular development and angiogenesis (Sheibani et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003), thus suggesting PECAM-1 isoforms may have specific functions during these processes. We previously demonstrated that PECAM-1-/- bEND cells are less migratory and differ in their adhesive properties compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells, which express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1. Here using PECAM-1 -/- bEND cells we show that expression of PECAM-1 impacts the adhesion and migration of EC in an isoform-specific manner. The expression of Δ14&15, but not Δ15, PECAM-1 isoform restored the migration defect that was observed in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. Expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1 resulted in sustained activation of MAPK/ERKs, disruption of adherens junctions, and lack of PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, and β-catenin junctional localization in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. Furthermore, expression of the Δ14&15 PECAM-1 resulted in enhanced migration and capillary morphogenesis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells without significantly affecting their adhesion to fibronectin or vitronectin. In contrast, expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 had minimal effect on migration and capillary morphogenesis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. However, the PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 were more adhesive on fibronectin and vitronectin. Thus, lack of exon 14 affected PECAM-1’s association with the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, but not Src kinase, impacting the intracellular signaling pathway(s) activated by PECAM-1. These results demonstrate, for the first time, the isoform-specific functions of PECAM-1 in the regulation of brain EC adhesion, migration, and capillary morphogenesis through modulation of intracellular MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway.

Recent studies suggest that MAPK/ERKs activation in EC by fluid shear stress is dependent on the PECAM-1 signaling function (Osawa et al., 2002; Tai et al., 2005). In addition, expression of PECAM-1 in epithelial cells can activate the MAPK/ERKs signaling pathway in an isoform-specific manner impacting cell adhesion and migration (Sheibani et al., 2000; Wang and Sheibani, 2006). Furthermore, sustained activation of MAPK/ERKs in PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells resulted in disruption of adherens junctions and enhanced cell migration (Wu and Sheibani, 2003). However, the role of PECAM-1 isoforms in activation of MAPK/ERKs in EC requires further study. Here we show that PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 have increased levels of active MAPK/ERKs. These cells exhibited a more scattered morphology, disruption of their adherens junctions, and increased migration. Furthermore, all of these cellular changes were dependent on activation of MAPK/ERKs and were reversed by MEK-1 inhibition. These changes were not observed in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 (Figs. 1, 2, 5, 7, 8) or PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells which express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 (Rothermel et al., 2005). Thus, PECAM-1 can activate the MAPK/ERKs pathway in an isoform-specific manner, thereby impacting cell adhesion and migration.

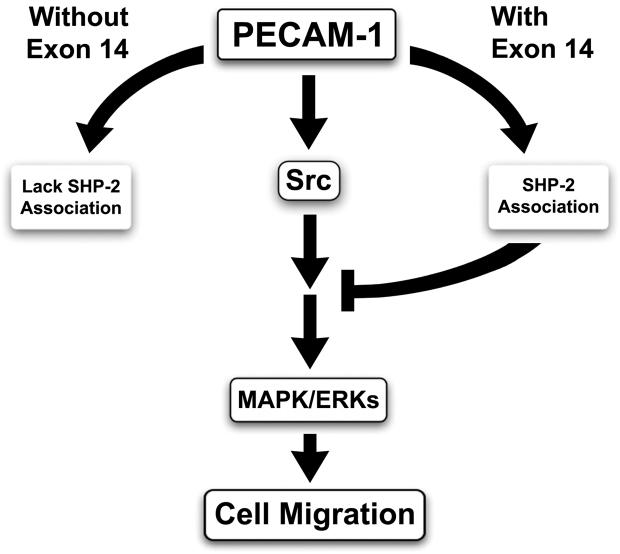

PECAM-1 contains important tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain whose phosphorylation provides a docking site for SH2 domain-containing proteins. The tyrosine residues in exons 13 and 14 are part of a consensus motif known as an ITIM domain. ITIM domains are found on many transmembrane receptor proteins and are generally found to inhibit downstream signaling pathways initiated by receptor kinases. Phosphorylation of the tyrosines in PECAM-1’s ITIM domains is important for its interaction with SH2-domain containing proteins including SHP-2 and Src (Jackson et al., 1997a; Jackson et al., 1997b; Wang and Sheibani, 2006). Thus, the presence or absence of exon 14 may impact the downstream signaling pathways engaged by PECAM-1. Our results indicate SHP-2 associates with the PECAM-1 isoforms containing exon 14 (full-length and Δ15) but not the isoforms lacking exon 14 (Δ14 and Δ14&15). However, Src association with PECAM-1 isoforms is exon 14-independent. It is speculated that interaction of PECAM-1 with SHP-2 brings a tyrosine phosphatase into close proximity with the signaling complexes assembled upon tyrosine phosphorylation of PECAM-1 promoting their turnover and destabilization. Our results suggest interaction of SHP-2 and phosphorylated PECAM-1 dephosphorylates upstream regulators of MAPK/ERKs, including Src kinase, thus inhibiting MAPK/ERKs activity. This is supported by the ability of PP1 (a Src kinase inhibitor) to block the enhanced migratory phenotype of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1, as well as activation of MAPK/ERKs in Δ15 PECAM-1 expressing cells incubated with SHP-2 inhibitor. These observations support the inhibitory signaling role proposed for PECAM-1 isoforms with intact ITIM domains (Fig. 10). The potential role of SHP-2 in PECAM-1-mediated MAPK/ERKs activation, perhaps through modulation of Src activity, whose association with PECAM-1 is exon 14 independent is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Fig. 10.

Negative impact of SHP-2 on PECAM-1-mediated MAPK/ERKs signaling. The ability of PECAM-1 isoforms to associate with Src kinase is exon 14 independent, while its association with SHP-2 is exon 14 dependent. Thus, the ability of isoforms with intact ITIM-domain to recruit SHP-2 to the PECAM-1 initiated signaling complexes negatively impacts the phosphorylation/activity of the down-stream and up-stream signaling molecules leading to the inhibition of activation of MAPK/ERKs.

PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoform lacked junctional localization of PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, and β-catenin. These changes were not observed in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5) or PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells which express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 (Rothermel et al., 2005; Sheibani et al., 1999). PECAM-1 can influence the subcellular localization of β-catenin (Biswas et al., 2003), perhaps through modulation of its phosphorylation and degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (Biswas et al., 2006). Although we did not observe a significant difference in β-catenin expression levels between PECAM-1+/+ and PECAM-1-/- bEND cells, we observed changes in the subcellular localization of β-catenin in cells expressing a specific PECAM-1 isoform. It is possible that PECAM-1, when phosphorylated, recruits both SHP-2 and β-catenin promoting dephosphorylation of β-catenin and adherens junctions formation. However, β-catenin interacts with the portion of PECAM-1 encoded by exon 15 (Biswas et al., 2005). If this is the only site of interaction between PECAM-1 and β-catenin, then isoforms lacking exon 15 (Δ15 and Δ14&15) should have limited ability to form adherens junctions. We observed no significant effect on formation and/or organization of adherens junctions in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 (Fig. 5) or PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells, which express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 (Rothermel et al., 2005). Thus, the role of PECAM-1 isoforms in regulation of β-catenin localization and expression, and its impact on adherens junction formation requires further investigation.

Regulation of integrin functions is essential during vascular development and angiogenesis where EC are required to detach from the extracellular matrix and migrate towards the source of proangiogenic stimulus. Several studies have suggested that PECAM-1 is able to mediate integrin activation, on both migrating leukocytes and platelets (Berman et al., 1996; Varon et al., 1998; Wee and Jackson, 2005). Furthermore, PECAM-1-/- bEND cells are less adherent to extracellular matrix proteins (ligands of integrins) compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells (Rothermel et al., 2005). Our present results indicate PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 were more adhesive on fibronectin and vitronectin compared to cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 or vector. PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells adhere well to these extracellular matrix proteins (Rothermel et al., 2005). The mechanism by which PECAM-1 affects EC adhesive properties remains largely unexplored, and it may be dependent on isoform-specific activation of Rho GTPases and/or association with αvβ3 integrin (Gratzinger et al., 2003b; Wang and Sheibani, 2006). Although activation of Rap1 is involved in PECAM-1 mediated activation of integrins on leukocytes and platelets (Fischer et al., 1994; Reedquist et al., 2000) its role in EC remains to be determined.

An optimal level of PECAM-1 is essential for capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel, such that too much or too little PECAM-1 inhibits this process (Sheibani and Frazier, 1998). Interestingly, we show here that the influence of PECAM-1 on capillary morphogenesis is also isoform specific. Cells expressing Δ15 PECAM-1 appeared to start organizing into aggregates as early as 6 h in Matrigel and formed larger aggregates with few processes between them by 24 h. This was very similar to PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing an empty vector (Fig. 9), or PECAM-1+/+ cells expressing multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 (Rothermel et al., 2005). In contrast, cells expressing the Δ14&15 PECAM-1 formed less extensive cell aggregates early and organize into an extensive network by 24 h. These data suggest that the role of PECAM-1 isoforms may vary during capillary morphogenesis.

In summary, expression of the Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoform in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells resulted in activation of the MAPK/ERKs pathway, disruption of adherens junction complexes, and enhanced cell migration and capillary morphogenesis. In contrast, expression of the Δ15 PECAM-1 had minimal effect on organization of adherens junctions, migration, and capillary morphogenesis of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells. PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells express multiple isoforms of PECAM-1 at different levels. The Δ14&15 PECAM-1 isoform is the most highly expressed, making up approximately 40% of the PECAM-1, while the Δ15 PECAM-1 makes up 12% of the PECAM-1 in these cells (Sheibani et al., 1999). Although expression of Δ15 PECAM-1 did not affect the morphology of PECAM-1-/- bEND cells compared to PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells, these cells were more adherent on fibronectin and vitronectin. This may contribute to the reduced migration observed in these cells compared to PECAM-1+/+ cells which also express a significant level of Δ14&15 PECAM-1. Thus, the expression of Δ14&15 PECAM-1 in PECAM-1+/+ cells may counteract the effects of Δ15 PECAM-1, which is also expressed in these cells, and promotes their migration. However, the rate of migration in PECAM-1-/- bEND cells expressing Δ14&15 PECAM-1 was significantly greater than that observed in PECAM-1+/+ bEND cells (Fig. 7N). These cells also formed significantly better capillary-like network when plated on Matrigel (Fig. 9F). These results may be explained, at least in part, by the lack of Δ15 PECAM-1 expression in these cells. Therefore, a tightly regulated expression of PECAM-1 isoforms with different signaling capabilities may be essential during vascular development and angiogenesis. The ability to express a specific PECAM-1 isoform in null EC will provide further insight into intracellular signaling mechanisms engaged by PECAM-1 isoforms. This knowledge will allow us to better understand how intracellular signaling pathways are integrated by these isoforms to regulate EC function during angiogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in parts by grants from the National Institutes of Health, EY13700 and EY16695 (NS), a Research Award from American Diabetes Association 106RA123 (NS), and a predoctoral fellowship from American Heart Association, 0510047Z (TAD). We thank Dr. Britta Engelhardt (University of Berne, Switzerland) for PECAM-1-/- bEND cells, Dr. Christine M. Sorenson for critical reading of the manuscript, and Elizabeth E. Scheef for help with figure preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albelda SM, Oliver PD, Romer LH, Buck CA. EndoCAM: a novel endothelial cell-cell adhesion molecule. J Cell Biol. 1990;110(4):1227–1237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman ME, Xie Y, Muller WA. Roles of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) in natural killer cell transendothelial migration and beta 2 integrin activation. J Immunol. 1996;156(4):1515–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas P, Canosa S, Schoenfeld D, Schoenfeld J, Li P, Cheas LC, Zhang J, Cordova A, Sumpio B, Madri JA. PECAM-1 affects GSK-3beta-mediated beta-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(1):314–324. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas P, Canosa S, Schoenfeld J, Schoenfeld D, Tucker A, Madri JA. PECAM-1 promotes beta-catenin accumulation and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303(1):212–218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas P, Zhang J, Schoenfeld JD, Schoenfeld D, Gratzinger D, Canosa S, Madri JA. Identification of the regions of PECAM-1 involved in [beta]- and [gamma]-catenin associations. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;329(4):1225–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao MY, Huber M, Beauchemin N, Famiglietti J, Albelda SM, Veillette A. Regulation of mouse PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation by the Src and Csk families of protein-tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(25):15765–15772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisser HM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Robinson CS, Wexler RS, Kerr JS, Garlanda C, Merwin JR, Madri JA, Albelda SM. Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(3):671–677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GS, Andrew DP, Takimoto H, Kaufman SA, Yoshida H, Spellberg J, Luis de la Pompa J, Elia A, Wakeham A, Karan-Tamir B, Muller WA, Senaldi G, Zukowski MM, Mak TW. Genetic Evidence for Functional Redundancy of Platelet/Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (PECAM-1): CD31-Deficient Mice Reveal PECAM-1-Dependent and PECAM-1-Independent Functions. J Immunol. 1999;162(5):3022–3030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TH, Gatling MN, McCormick F, Duffy CM, White GC., 2nd. Incorporation of Rap 1b into the platelet cytoskeleton is dependent on thrombin activation and extracellular calcium. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(25):17257–17261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graesser D, Solowiej A, Bruckner M, Osterweil E, Juedes A, Davis S, Ruddle NH, Engelhardt B, Madri JA. Altered vascular permeability and early onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in PECAM-1-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(3):383–392. doi: 10.1172/JCI13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzinger D, Barreuther M, Madri JA. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 modulates endothelial migration through its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003a;301(1):243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzinger D, Canosa S, Engelhardt B, Madri JA. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 modulates endothelial cell motility through the small G-protein Rho. FASEB J. 2003b;17(11):1458–1469. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1040com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilan N, Madri JA. PECAM-1: old friend, new partners. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(5):515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DE, Kupcho KR, Newman PJ. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that are required for the cellular association and activation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2. J Biol Chem. 1997a;272(40):24868–24875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DE, Ward CM, Wang R, Newman PJ. The protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 binds platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) and forms a distinct signaling complex during platelet aggregation. Evidence for a mechanistic link between PECAM-1- and integrin-mediated cellular signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997b;272(11):6986–6993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum NE, Gumina RJ, Newman PJ. Organization of the gene for human platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 shows alternatively spliced isoforms and a functionally complex cytoplasmic domain. Blood. 1994;84(12):4028–4037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TT, Barreuther M, Davis S, Madri JA. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is phosphorylatable by c-Src, binds Src-Src homology 2 domain, and exhibits immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-like properties. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(22):14442–14446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TT, Yan LG, Madri JA. Integrin engagement mediates tyrosine dephosphorylation on platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(21):11808–11813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Osawa M, Shigematsu H, Harada N, Fujiwara K. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is a major SH-PTP2 binding protein in vascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;408(3):331–336. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano R, Pepper MS, Mohle-Steinlein U, Risau W, Wagner EF, Orci L. Increased proteolytic activity is responsible for the aberrant morphogenetic behavior of endothelial cells expressing the middle T oncogene. Cell. 1990;62(3):435–445. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller WA. The role of PECAM-1 (CD31) in leukocyte emigration: studies in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57(4):523–528. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178(2):449–460. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman PJ. Switched at birth: a new family for PECAM-1. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(1):5–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman PJ, Berndt MC, Gorski J, White GC, 2nd, Lyman S, Paddock C, Muller WA. PECAM-1 (CD31) cloning and relation to adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily. Science. 1990;247(4947):1219–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1690453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman PJ, Newman DK. Signal Transduction Pathways Mediated by PECAM-1: New Roles for an Old Molecule in Platelet and Vascular Cell Biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(6):953–964. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CD, Cao G, Makrigiannakis A, DeLisser HM. Role of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs of PECAM-1 in PECAM-1-dependent cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287(4):C1103–1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00573.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Masuda M, Harada N, Lopes RB, Fujiwara K. Tyrosine phosphorylation of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) in mechanically stimulated vascular endothelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;72(3):229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Masuda M, Kusano K, Fujiwara K. Evidence for a role of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cell mechanosignal transduction: is it a mechanoresponsive molecule? J Cell Biol. 2002;158(4):773–785. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedquist KA, Ross E, Koop EA, Wolthuis RM, Zwartkruis FJ, van Kooyk Y, Salmon M, Buckley CD, Bos JL. The small GTPase, Rap1, mediates CD31-induced integrin adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2000;148(6):1151–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel TA, Engelhardt B, Sheibani N. Polyoma virus middle-T-transformed PECAM-1 deficient mouse brain endothelial cells proliferate rapidly in culture and form hemangiomas in mice. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202(1):230–239. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa K, Kimura T, Swieter M, Siraganian RP. The protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 associates with tyrosine-phosphorylated adhesion molecule PECAM-1 (CD31) J Biol Chem. 1997;272(49):31086–31091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel AR, Chew TW, Muller WA. Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule Deficiency or Blockade Significantly Reduces Leukocyte Emigration in a Majority of Mouse Strains. J Immunol. 2004;173(10):6403–6408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwaelder SM, Petch LA, Williamson D, Shen R, Feng GS, Burridge K. The protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 regulates RhoA activity. Curr Biol. 2000;10(23):1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Thrombospondin 1 expression in transformed endothelial cells restores a normal phenotype and suppresses their tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(15):6788–6792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Down-regulation of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 results in thrombospondin-1 expression and concerted regulation of endothelial cell phenotype. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(4):701–713. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Thrombospondin-1, PECAM-1, and regulation of angiogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14(1):285–294. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Newman PJ, Frazier WA. Thrombospondin-1, a natural inhibitor of angiogenesis, regulates platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 expression and endothelial cell morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8(7):1329–1341. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.7.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Sorenson CM, Frazier WA. Tissue specific expression of alternatively spliced murine PECAM-1 isoforms. Dev Dyn. 1999;214(1):44–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199901)214:1<44::AID-DVDY5>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Sorenson CM, Frazier WA. Differential modulation of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 isoforms through activation of extracellular regulated kinases. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(8):2793–2802. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowiej A, Biswas P, Graesser D, Madri JA. Lack of Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Attenuates Foreign Body Inflammation because of Decreased Angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(3):953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63890-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Williams J, Yan HC, Amin KM, Albelda SM, DeLisser HM. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) homophilic adhesion is mediated by immunoglobulin-like domains 1 and 2 and depends on the cytoplasmic domain and the level of surface expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(31):18561–18570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai L-k, Zheng Q, Pan S, Jin Z-G, Berk BC. Flow Activates ERK1/2 and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase via a Pathway Involving PECAM1, SHP2, and Tie2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(33):29620–29624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RD, Noble KE, Larbi KY, Dewar A, Duncan GS, Mak TW, Nourshargh S. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1)-deficient mice demonstrate a transient and cytokine-specific role for PECAM-1 in leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane. Blood. 2001;97(6):1854–1860. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varon D, Jackson DE, Shenkman B, Dardik R, Tamarin I, Savion N, Newman PJ. Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 serves as a costimulatory agonist receptor that modulates integrin-dependent adhesion and aggregation of human platelets. Blood. 1998;91(2):500–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sheibani N. Expression pattern of alternatively spliced PECAM-1 isoforms in hematopoietic cells and platelets. J Cell Biochem. 2002;87(4):424–438. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sheibani N. PECAM-1 isoform-specific activation of MAPK/ERKs and small GTPases: Implications in inflammation and angiogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:451–468. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Su X, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. Modulation of PECAM-1 expression and alternative splicing during differentiation and activation of hematopoietic cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88(5):1012–1024. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee JL, Jackson DE. The Ig-ITIM superfamily member PECAM-1 regulates the “outside- in” signaling properties of integrin {alpha}IIb{beta}3 in platelets. Blood. 2005;106(12):3816–3823. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CW, Wiedle G, Ballestrem C, Wehrle-Haller B, Etteldorf S, Bruckner M, Engelhardt B, Gisler RH, Imhof BA. PECAM-1/CD31 trans-homophilic binding at the intercellular junctions is independent of its cytoplasmic domain; evidence for heterophilic interaction with integrin alphavbeta3 in Cis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(9):3109–3121. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Sheibani N. Modulation of VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 mediated cell-cell adhesions by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(1):121–137. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H-C, Baldwin HS, Sun J, Buck CA, Albelda SM, DeLisser HM. Alternative Splicing of a Specific Cytoplasmic Exon Alters the Binding Characteristics of Murine Platelet/Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (PECAM-1) J Biol Chem. 1995;270(40):23672–23680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]