Abstract

Age-related changes have been documented in regions of the brain shown to process reward information. However, few studies have examined the effects of aging on associative memory for reward. The present study tested 7 mo old and 24 mo old rats on a conditioned flavor preference task. Half of the rats in each age group received an unsweetened grape-flavored solution (CS−) on odd-numbered days and a sweetened cherry-flavored solution (CS+) on even-numbered days. The remaining rats in each age group received a sweetened grape-flavored solution (CS+) on odd-numbered days and an unsweetened cherry-flavored solution (CS−) on even-numbered days. During the acquisition phase of testing, the designated solution (CS+ or CS−) was presented to each rat for 15 min daily across six consecutive days. On the preference phase, each rat received unsweetened cherry and unsweetened grape flavored solutions simultaneously for 15 min daily across four consecutive days. The 7 mo old rats showed a significant preference for the flavor that was previously sweetened during the acquisition phase (CS+) compared to the previously unsweetened solution (CS−) when the two unsweetened solutions were presented simultaneously during the preference phase of testing. In contrast, the 24 mo old rats did not show a preference and consumed roughly equal amounts of the previously sweetened (CS+) and unsweetened (CS−) solutions. Thus, the data suggest that the ability to form flavor-reward associations declines with increasing age, resulting in impaired conditioned flavor preference.

Keywords: Aging, Reward, Flavor, Associative Learning, Amygdala

Introduction

Rewards play a critical role in the organization and control of goal directed behavior [33]. The control of goal directed behavior often may require that a reward becomes associated with a behavior or stimulus based on past experience. A large number of studies in humans, nonhuman primates, and rodents have examined the neural substrates that may support the formation of associative memories based on fear [1,6,8,9,13,16,18,26,29,34,58]. However, until fairly recently, few studies have focused on memory for reinforcing or rewarding stimuli (for reviews see [5,62]). As discussed below, multiple brain regions have been suggested to play a role in memory for reward. Although many of these regions have been shown to be affected by healthy aging, little research has examined age-related changes in reward-based learning and animal studies have revealed controversial findings (for a review see [31])

As reviewed by White and McDonald [62] and Baxter and Murray [5], a large number of studies have suggested that one of the primary functions of the amygdala may be to form associations between a stimulus and a reward. The amygdala processes reward information via interactions with a number of different cortical and subcortical structures including: 1) the nucleus accumbens, 2) the midbrain dopaminergic system including the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra, 3) the basal forebrain cholinergic system, and 4) the medial and orbital regions of the prefrontal cortex [5]. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in healthy older humans have shown that increased age was associated with volumetric decreases in many of these regions including the frontal lobes [10,21,43], temporal lobes [10,43], amygdala [10,20], and basal ganglia [17]. In addition, age-related decreases in dopamine receptors have been found in the human striatum, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate [3,23,59]. Therefore, aging may have a significant effect on neural substrates critically involved in memory for reward.

As discussed by Kraemer and Apfelbach [27], the modality of a stimulus to be remembered is critical when determining efficient learning. Studies have shown that rats can readily learn and maintain a high level of performance on odor memory tasks [11,30,54]. Therefore, olfactory stimuli may be useful in behavioral paradigms designed to examine age-related changes in learning and memory. Furthermore, flavor cues based on olfactory and taste properties may help animals select foods that are nutritious based on rewarding properties and avoid foods that are toxic or harmful [64]. Research suggests that animals can learn to associate the flavor of foods and fluids with their postingestive rewarding consequences [55]. Roman et al. [47] reported that aged rats were significantly impaired in acquiring odor-reward associations compared to young rats. In their study, the odorants were presented orthonasally to the animals using odorants dissolved in air presented through odor ports. The present study aimed to examine age-related changes in odor-reward associations using a conditioned flavor preference task to offer insight into how flavor-reward association may be affected by aging in an animal model. Schiffman [50] suggested that flavor preferences and aversions may play a critical role in dietary selection and nutritional status in older humans. Therefore, the results of the present study may have important implications for understanding changes in flavor-reward associations in healthy older humans.

Methods

Subjects

Twenty-eight Fischer 344/Brown Norway (Harlan Laboratories) male rats 7 mo of age (n=14) and 24 mo of age (n=14) were used as test subjects. Each rat was individually housed, fed ad libitum, and had continuous access to water for 8 hr each day followed by 16 hr of water deprivation. Animals were maintained on a 12 hr diurnal light-dark cycle, and all testing was conducted during the light cycle.

Conditioned Flavor Preference Task Procedure

Conditioned flavor preference was assessed using a modified version [14] of a task originally described in Reilly and Pritchard [44]. All rats were tested over a period of 15 consecutive days. On all 15 days of the task, each rat was given free access to water for 8 hr each day following testing on the task. Each rat was then water deprived for 16 hr prior to the next testing session. For the first four days of testing, each rat was presented with water for 15 min, which was made available from an inverted graduated cylinder located centrally on the front side of a standard hanging cage with a drinking tube that extended into the cage. The amount consumed (ml) was recorded daily to establish a baseline for fluid consumption. Following the four-day water baseline phase, rats in each age group were equally assigned to one of two randomly selected groups. In the first group, each rat was presented with an unsweetened grape-flavored Koolaid solution (CS−) on odd-numbered days and a sweetened (32% sucrose) cherry-flavored solution (CS+) on even-numbered days. In the second group, each rat was presented with a sweetened (32% sucrose) grape-flavored solution (CS+) on odd-numbered days and an unsweetened cherry-flavored solution (CS−) on even-numbered days. Thus, flavor-reward pairings and day of presentation of the rewarding solution were counterbalanced across subjects in each age group. Days 5 through 10 constituted the acquisition phase, during which a single graduated cylinder filled with the appropriate flavored solution (CS+ or CS−) was presented to the rat centrally on the front of the cage for 15 min, in the same manner as the baseline phase. The amount consumed (ml) by each rat was recorded each day. Days 11-14 constituted the choice preference phase where each rat was presented with an unsweetened cherry flavored and an unsweetened grape flavored solution simultaneously once daily for 15 min. The position of each flavored solution varied randomly each day with respect to the left and right side of the cage to eliminate position bias. The amount (ml) consumed of each solution was recorded and was used as the dependent measure.

Sucrose Preference Task Procedure

To minimize the possibility that differences in conditioned flavor preference were the result of age-related differences in sweet taste perception, it is critical to demonstrate that the 24 mo old rats were able to perceptually discriminate between the solution containing sucrose and the unsweetened solution during the acquisition phase. Therefore, on day 15 all rats were administered a two-bottle sucrose preference test. Each rat was presented simultaneously with a water solution containing 2% sucrose and a water solution containing 32% sucrose. The position of each solution with respect to left and right side of the cage again was randomized across rats. The amount (mL) consumed of each solution was recorded and was used as the dependent measure.

Results

Conditioned Flavor Preference Task

An analysis was conducted to examine group differences in baseline water consumption during the first four days of testing. A 2 × 4 analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group (7 mo, 24 mo) as the between group factor and day (Days 1-4) as the within group factor revealed a significant main effect of day F(3, 78) = 3.34, p < .05 but did not detect a significant main effect of group F(1, 26) = 1.93, p =.18 or a group × day interaction F(3, 78) = 1.81, p =.15. The 7 mo old rats consumed a daily average of 7.25 ml (SE ± .64) and 24 mo old rats consumed a daily average of 6 ml (SE ± .13) during the four days of water baseline. Therefore, the analysis suggests that there were no significant differences in baseline water consumption between 7 mo and 24 mo old rats.

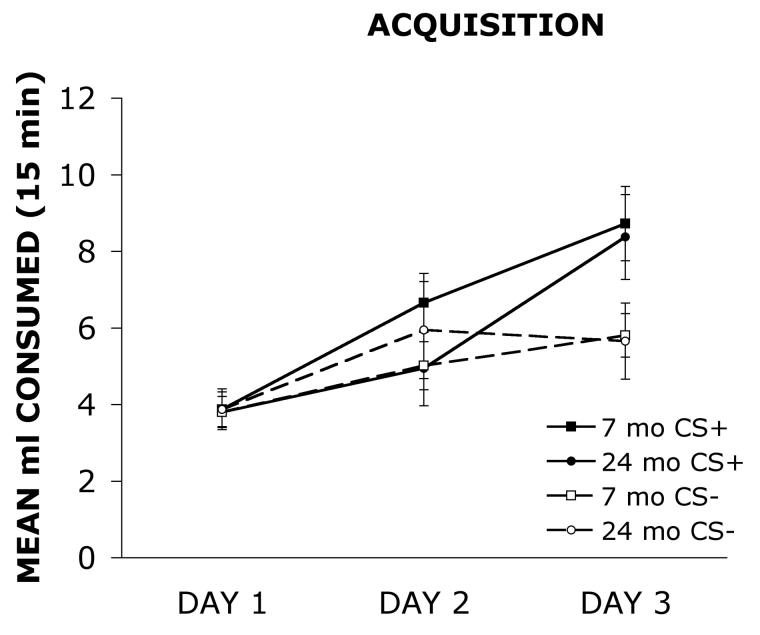

Figure 1 shows the mean ml consumed of the sweetened solution (CS+) and the unsweetened solution (CS−) by 7 mo and 24 mo old rats during the six day acquisition phase of testing. The CS+ and the CS− were presented on alternating days of the acquisition phase so each was presented on three different days. The data are graphed showing mean consumption of the CS+ and CS− on each of the three days.

Figure 1.

Mean ml consumed of the sweetened solution (CS+) and the unsweetened solution (CS−) by 7 mo and 24 mo old rats during the six day acquisition phase of testing. The CS+ and the CS− were presented on alternating days of the acquisition phase so each was presented on three different days. The data are graphed showing mean consumption of the CS+ and CS− on each of the three days.

A 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA with group (7 mo, 24 mo) as the between group factor and day (Days 1-3) and solution (CS+, CS−) as the within group factors revealed a significant main effect of day F(2, 52) = 28.41, p < .001, a main effect of solution F(1, 26) = 10.07, p < .01, and a significant day × solution interaction F(2, 52) = 6.99, p < .01. However, the analysis did not detect a significant main effect of group F(1, 26) = .06, p = .80. The analysis also did not detect significant interactions for group × day F(2, 52) = .10, p = .90, group × solution F(1, 26) = 2.29, p = .14, or group × day × solution F(2, 52) = 1.48, p = .24. These findings indicate that there were no significant consumption differences between 7 mo and 24 mo old rats during the acquisition. In addition, the main effect of solution demonstrates that both groups consumed more of the CS+ than the CS− during acquisition, suggesting that both groups of animals could discriminate between the sweetened and unsweetened solutions.

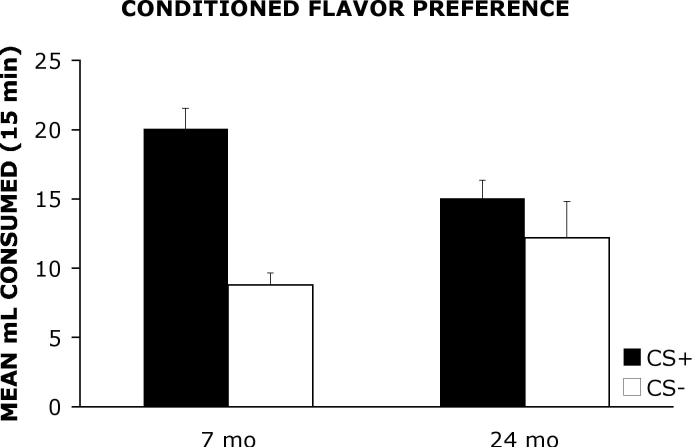

Figure 2 shows the mean ml consumed of the previously sweetened solution (CS+) and the previously unsweetened solution (CS−) when the two unsweetened flavors were presented concurrently to 7 mo and 24 mo old rats during the choice preference phase of testing.

Figure 2.

Mean ml consumed of the previously sweetened solution (CS+) and the previously unsweetened solution (CS−) when the two unsweetened flavors were presented concurrently to 7 mo and 24 mo old rats during the choice preference phase of testing.

A 2 × 2 ANOVA with group (7 mo, 24 mo) as the between group factor and solution (CS+, CS−) as the within group factor revealed a significant main effect of solution F(1, 26) = 12.11, p < .01 and a significant group × solution interaction F(1, 26) = 4.27, p < .05. However, the analysis did not detect a significant main effect of group F(1, 26) = .35, p = .56. A Newman-Keuls comparison test of the group × solution interaction revealed that 7 mo old rats consumed significantly more of the CS+ solution than the CS− solution on choice preference phase trials (p < .05). However, a significant difference was not detected in 24 mo old rats indicating that these animals consumed roughly equal quantities of the CS+ and CS− solutions.

Sucrose Preference Task

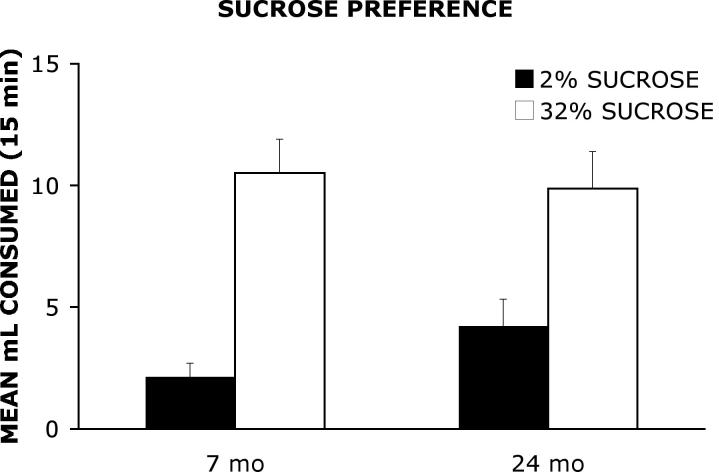

Figure 3 shows the mean ml consumed of a water solution 2% sucrose and a water solution containing 32% sucrose presented simultaneously to 7 mo and 24 mo old rats. A two-way ANOVA with age (7 mo, 24 mo) as the between group factor and sucrose concentration (2%, 32%) as the within group factor, yielded a significant main effect of concentration F(1, 26)= 21.93, p< .0001. However, the analysis did not detect a significant main effect of group F(1, 26)= 0.79, p= .38 or a significant group × concentration interaction F(1, 26)= .824, p= .37.

Figure 3.

Mean ml consumed of a water solution containing 2% sucrose and a water solution containing 32% sucrose presented simultaneously to 7 mo and 24 mo old rats.

Discussion

The present study compared the performance of young and aged rats on a conditioned flavor preference task. The data shown in Figure 1, indicate that there were no significant differences between 7 mo and 24 mo old rats in consumption of the CS+ or CS− solutions during the acquisition phase of testing. As shown in Figure 2, the 7 mo old rats showed a significant preference for the flavor that was sweetened previously during the acquisition phase (CS+) compared to the previously unsweetened solution (CS−) when the two unsweetened solutions were presented simultaneously on the preference phase of testing. In contrast, the 24 mo old rats did not show a preference and consumed roughly equal amounts of the previously sweetened (CS+) and unsweetened (CS−) solutions. To demonstrate a conditioned flavor preference, it is presumed that a rat must form an association between the flavor of the solution and the reward associated with the sucrose. The data suggest that the ability to form flavor-reward associations declines with increasing age.

According to Moreley and Thomas [35], an age-related decline in olfactory and taste sensation may decrease the hedonic qualities of oral stimuli. In the present study, the formation of flavor-reward associations during the acquisition phase required that rats could perceive the sweet taste of sucrose and preferred a 32% sucrose solution. As shown in Figure 3, young and old rats showed a significant preference for a 32% sucrose solution relative to a 2% sucrose solution when tested on a sucrose-flavored water preference task. In addition, young and old rats consumed roughly equal quantities of the 32% sucrose solution. These findings suggest not only that rats can perceive the difference between a 2% and 32% sucrose solution, but that aged rats prefer the 32% sucrose solution and the perceived incentive value of the 32% solution may be comparable between groups. In addition, the analysis of the data from the acquisition phase of testing revealed a significant main effect of solution but no significant effect of group or a group × solution interaction. These results demonstrate that both 7 mo and 24 mo old rats consumed more of the CS+ solution than the CS− solution particularly on the third day the CS+ or CS− solutions were presented (see Figure 1). These data offer further evidence that the 24 mo old rats preferred the sweetened solution and therefore could discriminate between the sweetened and unsweetened solutions during acquisition. Further support for intact sucrose perception in aged rats comes from Osada et al. [37], who did not detect age-related differences in neurophysiological responses to sucrose between young rats and old rats. In addition, studies by Schiffman [51] and Weiffenbach et al. [61] demonstrated that taste thresholds for sucrose, unlike thresholds for sodium chloride, do not increase with age in humans.

The formation of flavor-reward associations during the acquisition phase also would require that rats could discriminate between grape and cherry flavored solutions via retronasal stimulation of the olfactory system. Studies have reported that olfactory sensitivity is decreased in aged rats relative to young rats [2,27]. However, Kraemer and Apfelbach [27] did not detect any differences in olfactory discrimination between young and aged animals. Similarly, other studies have reported that aged rats can acquire olfactory discrimination tasks as readily as young rats [52]. A recent study from this laboratory demonstrated that 24 mo old Fischer 344/Brown Norway rats, the same strain used in the present experiment, learned an olfactory discrimination task as readily as 6 mo old rats [7]. The grape and cherry flavors were selected for the present task because rats have been shown to readily discriminate between these flavors [14]. Taken together, these studies suggest that the age-related impairments in conditioned flavor preference observed in present task were not solely due to an inability to discriminate between the olfactory based flavors used in the present task or an inability to perceive the taste of sucrose.

As noted by van der Staay [57], age-related differences in motivational level is a considerable concern for between group comparisons of young and aged rats on behavioral tasks. Therefore in the present study, it could be argued that differences in consumption of the CS+ in aged rats may be due to age-related decreases in motivation to drink. To rule out that any consumption differences in the aged rats were due solely to a reduction in motivation to drink, the total amount consumed of both solutions during preference phase trials was analyzed by the examining the main effect of group. However, the analysis did not detect a significant main effect, indicating that on the preference phase trials, young and aged rats consumed comparable total amounts of the previously sweetened solution (CS+) combined with the previously unsweetened solution (CS−). This finding suggests that task performance differences cannot be attributed to motivational differences alone.

As discussed by Roman et al. [47], prior investigations of age-related learning and memory impairments reveal that not all aged rats show deficits on behavioral tasks [4,41,42]. Although prior studies discussed above have shown that rats can learn an olfactory discrimination task as readily as controls [7,27,52] some studies have reported olfactory discrimination deficits in a subset of aged rats [28,47]. Roman and colleagues [47] examined age-related changes in odor-reward associations and found that 43% of aged rats learned the task as readily as young rats. In the present experiment, 43% of aged rats also performed within one standard deviation of control rats on the conditioned flavor preference based on preference scores (amount of CS+ consumed/total amount of CS+ and CS− consumed on preference phase trials). Similar results have been reported when aged rats were tested on a spatial version of the Morris water maze [22]. Thus, although group differences often are observed on behavioral tasks involving aged rats, not all aged rats show significant deficits in learning and memory. A recent study found that a subset of 24 mo old rats showed deficits in olfactory learning; however, the same rats performed normally on an analogous non-olfactory tasks [28]. The findings suggest that age-related deficits in olfactory learning may not necessarily extend to other sensory modalities.

The results of the present experiment suggest that age-related impairments in condition flavor preference may result from a decreased ability to form flavor-reward associations. The results are consistent with prior studies examining age-related deficits in odor-reward learning [47]. The amygdala has been shown to be involved in processing positive reward-based memories in appetitive situations [15,14,25,32,49,62] in addition to the well established role of the amygdala in fear-based and aversive memories [9,13,16,18,26,29,36,39,45,58,63]. Gilbert and colleagues [14] tested rats with amygdala lesions on the conditioned flavor preference task used in the present experiment. The results showed that amygdala lesions significantly disrupted conditioned flavor preference. The pattern of the deficit observed in the amygdala lesioned rats in the study by Gilbert and colleagues [14] is quite similar to the aged rats in the present experiment. A study by Sakai and Yamamoto [48] reported a similar deficit in odor-taste associative learning following amygdala lesions. Schoenbaum et al. [53] showed that rats with amygdala lesions could learn a series of four two-odor discrimination problems using a go/no-go paradigm, but were impaired on serial reversals of the original odor problem. As reviewed by White and McDonald [62] and Baxter and Murray [5], a large number of studies have suggested that one of the primary functions of the amygdala may be to form associations between a stimulus and a reward. Since the present deficit in conditioned flavor preference observed in aged rats may be due to an impaired ability to form an association between a flavor and a reward, age-related changes in the amygdala may contribute to the present deficit in aged rats. Since the amygdala is critically involved in reward processing and receives olfactory and gustatory projections [38], a conditioned flavor preference task may be particularly sensitive to age-related changes in the reward system.

However, as discussed previously, other regions of the brain have been shown to be involved in reward processing. In rodents, the agranular insular cortex has been shown to be involved in memory for reward [12,24,40]. In humans and nonhuman primates, the orbitofrontal cortex has been shown to play a significant role in reward [19,46,55,60]. Therefore, it is likely that age-related changes in other regions of the brain supporting reward-based mnemonic functions also contributed to the deficit in conditioned flavor preference in aged rats. In conclusion, the most parsimonious interpretation of the data is that the ability to form flavor-reward associations in a conditioned flavor preference task was impaired in aged rats. The findings cannot be explained solely by age-related group differences in odor-dependent flavor discrimination, sucrose discrimination, perceived incentive value of sucrose, or motivation.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by NIH grant #AG026505 from NIA to Paul E. Gilbert. Please address all correspondence to Dr. Paul Gilbert, SDSU-UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, 6363 Alvarado Court, Suite 103, San Diego, CA 92120. Tel: (619) 594-7409; Fax: (619) 594-3773; Email: pgilbert@sciences.sdsu.edu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adolphs R, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Cortical systems for the recognition of emotion in facial expressions. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7678–7687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07678.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbach R, Russ D, Slotnick BM. Ontogenetic changes in odor sensitivity, olfactory receptor area, and olfactory receptor density in the rat. Chem Senses. 1991;16:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backman L, Ginovart N, Dixon RA, Wahlin TB, Wahlin A, Halldin C, Farde L. Age-related cognitive deficits mediated by changes in the striatal dopamine system. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:635–637. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes CA. Memory deficits associated with senescence: a neurophysiological and behavioral study in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:74–104. doi: 10.1037/h0077579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baxter MG, Murray EA. The amygdala and reward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:563–573. doi: 10.1038/nrn875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broks P, Young AW, Maratos EJ, Coffey PJ, Calder AJ, Isaac CL, Mayes AR, Hodges JR, Montaldi D, Cezayirli E, Roberts N, Hadley D. Face processing impairments after encephalitis: Amygdala damage and recognition of fear. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brushfield AM, McDonald C, Luu T, Moreland C, Callahan B, Penso L, Pavlik D, Robinson L, Wirkus J, Gilbert PE. The effects of normal aging on odor memory using an animal model. Behav Neurosci. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calder AJ, Young AW, Rowland D, Perrett DI, Hodges JR, Etcoff NL. Facial emotion recognition after bilateral amygdala damage: Differential severe impairment of fear. Cogn Neuropsychol. 1996;13:699–745. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campeau S, Davis M. Involvement of the central nucleus and basolateral complex of the amygdala in fear conditioning measured with fear-potentiated startle in rats trained concurrently with auditory and visual conditioned stimuli. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2301–2311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02301.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffey CE, Wilkinson WE, Parashos IA, Soady SAR, Sullivan RJ, Patterson LJ, Figiel GS, Webb MC, Spritzer CE, Djang WT. Quantitative cerebral anatomy of the aging human brain: A cross-sectional study using magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychol. 1992;42:527–536. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darling FM, Slotnick BM. Odor-cued taste avoidance: a simple and efficient method for assessing olfactory detection, discrimination and memory in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:817–22. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decoteau WE, Kesner RP, Williams JM. Short-term memory for food reward magnitude: The role of the prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 1997;88:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fanselow MS, Kim JJ. Acquisition of contextual fear Pavlovian fear conditioning is blocked by application of an NMDA receptor antagonist D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid to the basolateral amygdala. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:210–212. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert PE, Campbell A, Kesner RP. The role of the amygdala in conditioned flavor preference. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;79:118–121. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. Involvement of the amygdala but not the hippocampus in pattern separation based on reward value. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:338–353. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goosens KA, Maren S. Contextual and auditory fear conditioning are mediated by the lateral, basal, and central amygdaloid nuclei. Learn Mem. 2001;8:148–155. doi: 10.1101/lm.37601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunning-Dixon FM, Head D, McQuain J, Acker JD, Raz N. Differential aging of the human striatum: a prospective MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1501–1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holahan MR, White NM. Conditioned memory modulation, freezing, and avoidance as measures of amygdala-mediated conditioned fear. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:250–275. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izquierdo A, Suda RK, Murray EA. Comparison of the effects of bilateral orbital cortex lesions and amygdala lesions on emotional responses in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7540–7548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1232-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu YC, Waring SC, O'Brien PC, Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E. Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurol. 1997;49:786–94. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst AC, Stout JC, Bonner J, Hesselink JR. Effects of age on tissues and regions of the cerebrum and cerebellum. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:581–94. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang HK, Owyang VV, Hong JS, Gallagher M. Elevated dynorphin in the hippocampal formation of aged rats: Relation to cognitive impairment on a spatial learning task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2948–2951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaasinen V, Vilkman H, Hietala J, Nagren K, Helenius H, Olsson H, Farde L, Rinne J. Age-related dopamine D2/D3 receptor loss in extrastriatal regions of the human brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:683–688. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesner RP, Gilbert PE. The role of the agranular insular cortex in anticipation of reward contrast. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.02.002. in press. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kesner RP, Williams JM. Memory for magnitude of reinforcement: Dissociation between the amygdala and hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;64:237–244. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Killcross S, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Different types of fear conditioned behavior mediated by separate nuclei within the amygdala. Nature. 1997;388:377–380. doi: 10.1038/41097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer S, Apfelbach R. Olfactory sensitivity, learning and cognition in young adult and aged male Wistar rats. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:435–42. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaSarge CL, Montgomery KS, Tucker C, Slaton GS, Griffith WH, Setlow B, Bizon JL. Deficits across multiple cognitive domains in a subset of aged Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:928–936. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeDoux JE, Cicchetti P, Xagoraris A, Ramonski LM. The lateral amygdaloid nucleus, sensory interface of the amygdala in fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1062–1069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01062.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu XC, Slotnick BM, Silberberg AM. Odor matching and odor memory in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1993;53:795–804. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90191-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marschner A, Mell T, Wartenburger I, Villringer A, Reischies FM, Heekeren HR. Reward-based decision making and aging. Brain Res Bull. 2005;67:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald RJ, White NM. A triple dissociation of memory systems: Hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:3–22. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mell T, Heekeren HR, Marschner A, Wartenburger A, Reischies FM. Effect of aging on stimulus-reward association learning. Neurospychologia. 2005;43:554–563. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Murray EA, Malkova L, Mishkin M. Effects of aspiration versus neurotoxic lesions of the amygdala on emotional responses in monkeys. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4403–4418. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreley JE, Thomas DR. Anorexia and aging: Pathophysiology. Nutrition. 1999;15:499–503. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris PL, Robinson RG, Raphael B, Hopwood MJ. Lesion location and poststroke depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:399–403. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osada K, Michio K, Bruce PB, Hitoshi S, Kenji T, Yuji F. Age related decreases in neural sensitivity to NaCL in SHR-SP. J Vet Med Sci. 2002;65:313–317. doi: 10.1292/jvms.65.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pare D. Role of the basolateral amygdala in memory consolidation. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:409–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ragozzino ME, Kesner RP. The role of agranular insular cortex in working memory for food reward value and allocentric space in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;98:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rapp PR, Rosenberg RA, Gallagher M. An evaluation of spatial information processing in aged rats. Behav Neurosci. 1987;101:3–12. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.101.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rapp PR, Amaral DG. Individual differences in the cognitive and neurobiological consequences of normal aging. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:340–345. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raz N, Gunning FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, McQuain J, Briggs SD, Loken WJ, Thornton AE, Acker JD. Selective aging of the human cerebral cortex observed in vivo: differential vulnerability of the prefrontal gray matter. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:268–82. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reilly S, Pritchard TC. Gustatory thalamus lesions in the rat: II. Aversive and appetitive taste conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:746–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rollins BL, Stines SG, McGuire HB, King BM. Effects of amygdala lesions on body weight, conditioned taste aversion, and neophobia. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rolls ET. The functions of orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:11–29. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roman FS, Alescio-Lautier B, Soumireu-Mourat B. Age-related learning and memory deficits in odor-reward association in rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)02030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakai N, Yamamoto T. Effects of excitotoxic brain lesions on taste-mediated odor learning in the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;75:128–39. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salinas JA, McGaugh JL. The amygdala modulates memory for changes in reward magnitude: Involvement of the amygdaloid GABAergic system. Behav Brain Res. 1996;80:87–89. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiffman SS. Taste and smell losses in normal aging and disease. JAMA. 1997;278:1357–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiffman SS. Perception of taste and smell in elderly persons. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1993;33:17–26. doi: 10.1080/10408399309527608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoenbaum G, Nugent S, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Teaching old rats new tricks: age-related impairments in olfactory reversal learning. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:555–64. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Nugent SL, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Lesions of orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala complex disrupt acquisition of odor-guided discriminations and reversals. Learn Mem. 2003;10:129–40. doi: 10.1101/lm.55203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slotnick BM, Kufera A, Silberberg AM. Olfactory learning and odor memory in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1991;50:555–61. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90545-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tremblay L, Schultz W. Relative reward preference in primate orbitofrontal cortex. Nature. 1999;398:704–708. doi: 10.1038/19525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Touzani K, Scaflani A. Conditioned flavor preference and aversion: Role of the lateral hypothalamus. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:84–93. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Staay FJ. Assessment of age-associated cognitive deficits in rats: A tricky business. Neurosci Behav Rev. 2002;26:753–759. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venton BJ, Robinson TE, Kennedy RT, Maren S. Dynamic amino acid increases in the basolateral amygdala during acquisition and expression of conditioned fear. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3391–3398. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Volkow ND, Gur RC, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Moberg PJ, Ding YS, Hitzemann R, Smith G, Logan J. Associations between decline in brain dopamine activity with age and cofnitive and motor impairment in healthy individuals. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:344–349. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallis JD, Miller EK. Neuronal activity in primate dorsolateral and orbal prefrontal cortex during performance of a reward preference task. J Neurosci. 2003;18:2069–2081. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiffenbach JM, Baum BJ, Burghauser R. Taste thresholds: Quality specific variation with human aging. J Gerontol. 1982;37:372–377. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White NM, McDonald RJ. Multiple parallel memory systems in the brain of the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:125–184. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto T, Fujimoto Y, Shimura T, Sakai N. Conditioned taste aversion in rats with excitotoxic lesions. Neurosci Rev. 1995;22:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00875-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yiin Y, Ackroff K, Sclafani A. Flavor preferences conditioned by intragastric nutrient infusions in food restricted and free-feeding rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]