Abstract

Members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) subfamily responsive to environmental stress stimuli are known as SAPKs (stress-activated protein kinases), which are conserved from yeast to humans. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Spc1/Sty1 SAPK is activated by diverse forms of stress, such as osmostress, oxidative stress and heat shock, and induces gene expression through the Atf1 transcription factor. Sin1 (SAPK interacting protein 1) was originally isolated as a protein that interacts with Spc1, and its orthologs were also found in diverse eukaryotes. Here we report that Sin1 is not required for the stress gene expression regulated by Spc1 and Atf1, and that Sin1 is an essential component of TOR (target of rapamycin) complex 2 (TORC2). TORC2 is not essential for cell viability in S. pombe but plays important roles in cellular survival of stress conditions through phosphorylation and activation of an AGC-family protein kinase, Gad8. In addition, inactivation of Gad8 results in a synthetic growth defect with cdc25-22, a temperature-sensitive mutation of the Cdc25 phosphatase that activates Cdc2 kinase at G2/M. Gad8 also positively regulates expression of the CDK inhibitor gene rum1+, which is essential for cell cycle arrest in G1 after nitrogen starvation. These results strongly suggest that the TORC2–Gad8 pathway has multiple physiological functions in cellular stress resistance and cell cycle progression at both G1/S and G2/M transitions.

Keywords: cell cycle, fission yeast, stress, TOR, TORC2

INTRODUCTION

Stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs) form an evolutionarily conserved subfamily of the MAP kinase (MAPK), members of which are stimulated in response to environmental stress. The prototype of SAPK was first identified in budding yeast as Hog1, which is mainly activated by high osmolarity stress.1 On the other hand, human JNK (c-Jun N-terminal Kinase) and p38 SAPKs2 as well as Spc1/Sty1 in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe3 are activated in response to diverse forms of stress, including osmostress, heat shock, oxidative stress and nutritional starvation. In S. pombe, activated Spc1 induces expression of a set of stress resistance genes through the Atf1 transcription factor.4–6 Cells lacking the functional Spc1–Atf1 pathway are hypersensitive to diverse forms of stress conditions, indicating the essential role of the SAPK signaling in cellular survival of environmental changes. In addition, Spc1 positively regulates the initiation of mitosis independently of the Atf1-regulated gene expression.7–9

Sin1 (SAPK interacting protein 1) was isolated by a yeast two-hybrid screen as a protein that interacts with Spc1 MAPK.10 It was reported that a sin1 mutant was hypersensitive to various stress conditions and defective in the stress gene expression regulated by the Spc1–Atf1 pathway and that by Pap1, an AP-1 family transcription factor.10 Sin1 is widely conserved among eukaryotic species,11,12 and its mammalian ortholog also interacts with JNK SAPK13 and MEKK2 MAPK kinase kinase.14 More recently, however, Sin1 orthologs have been identified in a protein complex with the TOR protein kinase. The TOR kinase was first discovered in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a cellular target of rapamycin, an anti-proliferative drug used as immunosuppressant,15 and subsequently, TOR orthologs were identified ubiquitously among eukaryotes. Two distinct protein complexes containing TOR, TOR complex (TORC) 1 and 2, are conserved between budding yeast and mammals, and these complexes appear to have different regulatory functions in cellular responses to nutrients and other extracellular stimuli.16 TORC2 in diverse eukaryotes contain orthologs of Sin1 as an essential component, including Avo1 in budding yeast,17,18 RIP3 in Dictyostelium19 and mSin1 in mammals.20–22 A recent intriguing progress in our understanding of the TORC2 function is the identification of mammalian TORC2 (mTORC2) as a kinase that phosphorylates the C-terminal hydrophobic motif of an AGC-family kinase, Akt/protein kinase B (PKB).20–23 Together with the phosphorylation of the T-loop by PDK1 kinase, this TORC2-dependent phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif contributes to full activation of Akt in response to insulin and the insulin-like growth factor (IGF1). Akt plays pivotal roles in modulation of glucose uptake and metabolism,24 and also promotes cell survival and proliferation through phosphorylation of forkhead-family transcription factors and other substrates.25

In addition to Sin1, orthologs of the other TORC2 subunits are also present in the S. pombe genome. Like S. cerevisiae, S. pombe has two TOR homologs, Tor1 and Tor2, with Tor2 being essential for viability.26,27 The Δtor1 mutant is viable but defective in the phosphorylation of the C-terminal hydrophobic motif of an AGC-family protein kinase, Gad8, which is essential for mating and cellular stress resistance.28 S. pombe Ste2029 shares significant sequence similarity to Avo3/rictor, another conserved subunit of TORC2 in budding yeast and higher eukaryotes.16 In addition, Wat1/Pop330 in S. pombe appears to be an ortholog of Lst8, a common subunit for both TORC1 and TORC2 in budding yeast and mammals.16 Like the Δtor1 mutant, Δste20 and Δwat1 are sterile, and a temperature-sensitive growth phenotype has also been reported with Δwat1.29,30 It has recently been reported that Tor1, but not Tor2, associates with Sin1 and Ste20,31 possibly forming a TORC2-like complex in S. pombe. However, TORC2 function in S. pombe remains to be characterized.

Here we report that, in contrast to the earlier report,10 Sin1 is not required for the Atf1- and Pap1-regulated stress gene expression. However, like its orthologs in other eukaryotes, Sin1 is an essential component of TORC2 in S. pombe. We have demonstrated that S. pombe TORC2 is required for phosphorylation and activation of Gad8 kinase. Thus, regulation of Gad8 by TORC2 in S. pombe has some resemblance to that of Akt by mTORC2. In addition to its role in cellular stress resistance, the TORC2–Gad8 pathway promotes the initiation of mitosis and also affects expression of the CDK inhibitor rum1+ gene, which is essential for G1 cell cycle arrest after nitrogen starvation. These results shed light on the crucial cellular functions of TORC2 in S. pombe.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. pombe strains and general techniques

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Gene disruption of the chromosomal sin1+ and ste20+ loci with the kanMX6 marker gene was performed by the PCR-based method32 and confirmed by genomic Southern hybridization. In the Δsin1 (sin1::kanMX6) strains, the sequence between nucleotides −68 to 2049 of the sin1+ open reading frame (ORF) was replaced by the kanMX6 marker gene fragment. DNA sequences of the PCR primers used in this study are available upon request. QuikChange XL (Stratagene) was used for site-directed mutagenesis. Growth media and basic techniques for S. pombe have been described.33 Northern blotting with total RNA was performed as described previously.4 Stress sensitivity of wild-type and mutant strains was tested by the drop test.34

Table 1.

S. pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 972 | h− | Laboratory stock |

| CA3 | h− leu1 ura4 | Laboratory stock |

| CA101 | h− leu1 | Laboratory stock |

| CA287 | h− leu1 ura4 pap1::ura4+ | Ref. 55 |

| CA4231 | h+ leu1 ura4 his7-366 cdc25-22 | Laboratory stock |

| CA4574 | h− leu1 ura4 sin1::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA4593 | h− leu1 ura4 tor1::ura4+ | Ref. 26 |

| CA4763 | h− leu1 ura4 sin1::kanMX6 atf1:12myc(ura4+) | This study |

| CA4765 | h− leu1 ura4 tor1::ura4+ atf1:12myc(ura4+) | This study |

| CA4767 | h− leu1 ura4 tor1::ura4+ sin1::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA4770 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8:6HA≪kanr gad8::ura4+ | Ref. 28 |

| CA4783 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8:6HA≪kanr gad8::ura4+ tor1::ura4+ | This study |

| CA4800 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8:6HA≪kanr gad8::ura4+ sin1::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA4925 | h− leu1 ura4 tor1::ura4+ ste20::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA4955 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8:6HA≪kanr gad8::ura4+ ste20::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA5021 | h− leu1 ste20::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA5126 | h− leu1 sin1::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA5142 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8::ura4+ | Ref. 28 |

| CA5266 | h− ura4 tor1::ura4+ | This study |

| CA5268 | h− ura4 gad8::ura4+ | This study |

| CA5687 | h− leu1 pop3::kanMX6 | Ref. 30 |

| CA5696 | h− leu1 ura4 tor1::ura4+ pop3::kanMX6 | This study |

| CA5697 | h− leu1 ura4 gad8:6HA≪kanr gad8::ura4+ pop3::kanMX6 | This study |

| FG2156 | h− leu1 ura4 atf1:12myc(ura4+) | Ref. 56 |

| KS1497 | h− leu1 ura4 atf1::ura4+ | Ref. 4 |

The leu1 and ura4 alleles used are leu1-32 and ura4-D18, respectively.

Biochemical techniques

Activation of Spc1 SAPK was detected in crude S. pombe cell lysate by immunoblotting35 with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the Spc1 peptide phosphorylated on both Thr-171 and Tyr-173. Detection of Gad8HA by anti-HA immunoblotting and the kinase assay of immunoprecipitated Gad8 was performed as reported28 with the following modifications. As a substrate for the Gad8 kinase assay, amino acid residues 209–411 of Fkh2 was expressed in E. coli as GST fusion, using the pGEX-KG expression vector.36 Immunoprecipitated Gad8HA and GST-Fkh2 purified by glutathione-Sepharose chromatography were incubated in the kinase assay buffer with [γ-32P]ATP23 at room temperature for 2 min, followed by SDS-PAGE. PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) was used for quantification of radioactivity in the kinase assay.

RESULTS

Sin1 is not required for the stress gene expression regulated by Spc1 SAPK

It was previously reported that the Atf1 transcription factor became unstable in a sin1 mutant exposed to stress, leading to failure in the expression of the Atf1-regulated genes.10 Because only a portion of the sin1 ORF was deleted in the sin1 mutant used in those experiments, we newly constructed sin1 null (Δsin1) strains (sin1::kanMX6) to reexamine the phenotypes caused by the loss of Sin1. In response to high osmolarity stress, Atf1 exhibited a mobility shift due to phosphorylation by Spc1 SAPK,4 but destabilization of Atf1 was not observed in Δsin1 cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the Δsin1 mutant showed no apparent defect in the stress-induced expression of gpd1+ and pyp2+ (Fig. 1B), which are under the regulation by Atf1.4,5 These results strongly suggest that Sin1 is not required for the stress-gene expression regulated by the Spc1–Atf1 pathway.

Figure 1.

(A) Phosphorylation and expression of the Atf1 protein is not altered in Δsin1 and Δtor1 mutants. Wild-type (FG2156), Δsin1 (CA4763) and Δtor1 (CA4765) strains carrying the atf1:myc allele were grown in YES medium at 30°C and subjected to high osmolarity stress of 0.6 M KCl for the time indicated, and their cell lysate was analyzed by anti-myc immunoblotting. (B) Stress-induced expression of the Atf1-regulated genes is not affected by the Δsin1 and Δtor1 mutations. Wild-type (CA3), Δtor1 (CA4593) and Δsin1 (CA4574) strains were exposed to high osmolarity stress as in (A) and their total RNA was subjected to northern hybridization for gpd1+ and pyp2+, which encode glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and the Pyp2 tyrosine phosphatase, respectively. The leu1 probe served as a loading control.

(C) Transient activation of Spc1 MAPK upon stress in wild-type, Δsin1 and Δtor1 strains. Wild-type (CA101), Δsin1 (CA4574), Δtor1 (CA4593) and Δatf1 (KS1497) strains were exposed to high osmolarity stress as in (A) and their cell lysate was analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated, active form of Spc1 (P-Spc1).

Stress-induced activation of Spc1 SAPK was not significantly affected in the Δsin1 mutant, and like in wild-type cells, transient phosphorylation of Spc1 was detected after osmostress (Fig. 1C) and other stress treatments (data not shown). In contrast, Spc1 remained phosphorylated to later time points in Δatf1 cells (Fig. 1C, bottom) due to their defect in the expression of pyp2+, which encodes a tyrosine phosphatase to dephosphorylate Spc1.7,37 Thus, the kinetics of stress-induced Spc1 activation in the Δsin1 mutant is different from that in the Δatf1 strain, corroborating that the Δsin1 mutant is not defective in the Atf1-dependent gene expression.

It was also reported that Sin1 is required for Pap1-dependent gene transcription.10 The Pap1 transcription factor is activated in response to low concentrations of H2O2 and induces expression of the trr1+ thioredoxin reductase gene and other genes in cellular response to oxidative stress.38,39 When treated with 0.2 mM H2O2, which is known to strongly activate Pap1,38,39 Δsin1 cells induced trr1+ to a level comparable to that in wild-type cells (Fig. 2). In contrast, no induction of trr1+ was observed in Δpap1 cell. Therefore, Sin1 does not appear to be required for Pap1-induced gene expression upon oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

The Δsin1 and Δtor1 mutants can induce expression of trr1+, the thioredoxin reductase gene regulated by the Pap1 transcription factor. Wild-type (CA101), Δtor1 (CA4593), Δsin1 (CA4574) and Δpap1 (CA287) strains were grown in YES medium at 30°C and stressed by 0.2 mM H2O2, followed by northern blotting with their total RNA. Ethidium bromide-staining of rRNAs served as a loading control.

On the other hand, consistent with the previously reported sin1 mutant phenotypes,10 we found that Δsin1 cells were sterile, hypersensitive to high temperature and osmolarity, and more elongated than wild-type cells, a phenotype indicative of a delay in mitotic initiation (see below).

Genetic evidence of TORC2-like complex in S. pombe

It has recently been reported that Sin1, Ste20 and Wat1 can be co-purified with Tor1 in immunoprecipitation experiments, suggesting that these proteins form a TORC2-like complex in S. pombe.31 To test whether these proteins indeed function in the same signaling pathway, we performed epistasis analysis. Δsin1 cells showed increased sensitivity to high osmolarity and temperatures, phenotypes very similar to those of Δtor1 (Fig. 3, top panels). Construction of the Δtor1 Δsin1 double mutant demonstrated that the stress sensitivity of the double mutant was not severer than that of the individual single mutants. Similar stress-sensitive phenotypes were found with the Δste20 mutant, and like Δsin1, the Δste20 defect was not additive to that of Δtor1 (Fig. 3, middle panels). These results are consistent with the idea that Tor1, Sin1 and Ste20 function in the same pathway that affects cellular stress resistance. The Δwat1 mutant exhibited moderate osmosensitivity, which did not exacerbate the Δtor1 phenotype in the Δtor1 Δwat1 double mutant (Fig. 3, bottom panels), implying that Wat1 also functions in the same pathway as Tor1 for cellular osmoresistance. However, the temperature sensitivity of the Δwat1 mutant was more severe than that of the Δtor1, Δsin1 and Δste20 mutants (Fig. 3, bottom panels), implying that Wat1 has additional cellular function.

Figure 3.

Genetic evidence for functional interaction of tor1+ with sin1+, ste20+ and wat1+. Wild-type (CA101), Δtor1 (CA4593), Δsin1 (CA5126), Δtor1 Δsin1 (CA4767), Δste20 (CA5021) and Δtor1 Δste20 (CA4925), Δwat1 (CA5687) and Δtor1 Δwat1 (CA5696) strains were grown in liquid YES medium at 30°C, and their growth under high osmolarity (0.4 M KCl) and at high temperature (37°C) was tested by spotting serial dilutions on agar plates.

These genetic data corroborate the idea that Sin1, Tor1, Ste20 and Wat1 form a TORC2-like complex and function together in the same signaling pathway required for cellular stress survival. However, like Δsin1, the Δtor1 mutant did not show any defect in the gene expression regulated by the Spc1–Atf1 (Fig. 1) and Pap1 (Fig. 2) pathways, indicating that TORC2 is not required for the function of these stress response pathways. We also observed no apparent defect in cellular actin organization with Δtor1, Δsin1 and Δste20 cells (data not shown), in contrast to the TORC2 mutants in budding yeast.17

S. pombe TORC2 regulates phosphorylation and activation of Gad8 kinase

It was reported that Tor1 is required for the phosphorylation of an AGC-family protein kinase, Gad8, at Ser-546 in the C-terminal hydrophobic motif, which is conserved among the AGC-family kinases.28 As described above, Tor1 forms a TORC2-like complex with Sin1, Ste20 and Wat1, but it has not been tested whether this complex is involved in the phosphorylation of Gad8. Therefore, we examined the Gad8 phosphorylation in strains lacking the TORC2 components, Sin1, Ste20 and Wat1. The activating phosphorylation of Gad8 in the hydrophobic motif reduces its electrophoretic mobility in SDS-PAGE.28 Like in Δtor1, the phosphorylated form of Gad8 was not detected in the Δsin1, Δste20 and Δwat1 strains (Fig. 4A, upper panels). Therefore, not only Tor1, but also the other components of TORC2 are required for phosphorylation of the Gad8 hydrophobic motif.

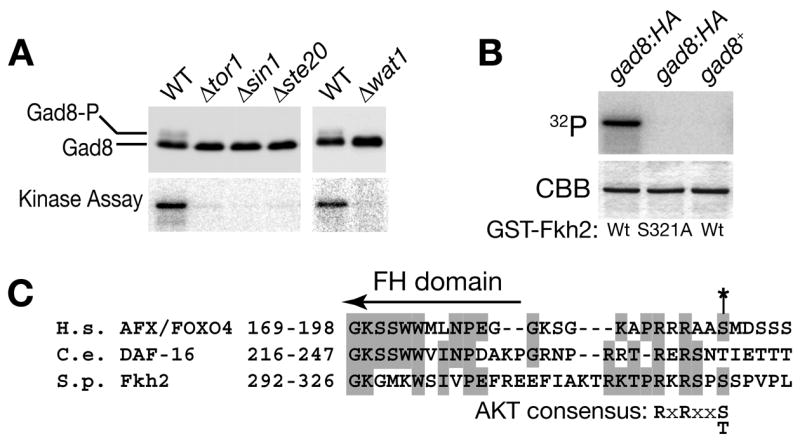

Figure 4. S. pombe TORC2 regulates the phosphorylation and activity of Gad8 kinase, which can phosphorylate an Akt phosphorylation motif in the Fkh2 transcription factor.

(A) The activating phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif in Gad8 is dependent on Tor1, Sin1, Ste20 and Wat1. Wild-type (CA4770), Δtor1 (CA4783), Δsin1 (CA4800), Δste20 (CA4955) and Δwat1 (CA5697) strains carrying the gad8:HA allele were grown in YES medium and their cell lysate was analyzed by anti-HA immunoblotting (upper panels). The Gad8HA protein immunoprecipitated from each cell lysate was assayed for its kinase activity against the bacterially produced GST-Fkh2 protein in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (lower panels).

(B) Fkh2 with and without an alanine substitution of Ser-321 was expressed in E. coli as GST-fusions, and the purified fusion proteins were incubated with Gad8HA immunoprecipitated from the gad8:6HA strain (CA4770) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie Blue staining (CBB) and autoradiography (32P) of GST-Fkh2. Immunoprecipitate from a gad8+ strain (CA101) was used as a negative control.

(C) Amino acid sequence alignment of forkhead-family transcription factors, human AFX/FOXO4, C. elegans DAF-16 and S. pombe Fkh2. All three proteins contain an Akt phosphorylation site motif at the C-terminus of the DNA-binding forkhead (FH) domain. An asterisk indicates a known Akt phosphorylation site in AFX, Ser-193, which is aligned to Ser-321 in Fkh2.

To determine the contribution of the TORC2-dependent phosphorylation to the Gad8 activity, we set out to establish an in vitro kinase assay for Gad8. As a substrate for the assay, we identified the Fkh2 protein, a forkhead transcription factor involved in cell cycle-regulated gene expression.40–42 Fkh2 was bacterially expressed as a fusion with GST (glutathione S-transferase), which was strongly phosphorylated by HA-tagged Gad8 immunoprecipitated from S. pombe cell lysate (Fig. 4B, lane 1) but not by mock immunoprecipitates (lane 3). Thus, Fkh2 appears to be an excellent substrate of Gad8 kinase in the in vitro assay. Fkh2 orthologs in higher eukaryotes, such as mammalian AFX/FOXO4 and DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans, are known to be phosphorylated by Akt/PKB at multiple sites.43 As shown in Fig. 4C, amino acid sequence alignment suggests that one of the Akt phosphorylation sites in AFX/FOXO4, Ser-193, is conserved in Fkh2 as Ser-321, which matches the consensus motif for phosphorylation by Akt, RXRXXS/T.44 To test whether Fkh2 Ser-321 is phosphorylated by Gad8, this residues is substituted with alanine (S321A) in GST-Fkh2. Gad8 failed to phosphorylate this mutant GST-Fkh2 in the kinase assay (Fig. 4B, lane 2), demonstrating that Gad8 phosphorylates Ser-321 of Fkh2 in vitro. These results suggest that Gad8 kinase has substrate specificity similar to that of mammalian Akt. However, we noticed that a strain carrying the S321A mutation in the chromosomal fkh2 locus did not show Δgad8-like phenotypes, such as sterility, sensitivity to high temperature and osmolarity, and cell cycle defects (data not shown). Therefore, Fkh2 does not seem to be a major in vivo substrate of Gad8 kinase.

Having established a Gad8 kinase assay, we then measured Gad8 activity in mutants lacking functional TORC2. Gad8 immunoprecipitated from Δtor1, Δsin1, Δste20 and Δwat1 showed dramatically reduced activity against GST-Fkh2 in the kinase assay (Fig. 4A, lower panels). These results strongly suggest that TORC2-dependent phosphorylation is crucial for activation of Gad8. Consistently, the Δgad8 mutant exhibits sterile and stress-sensitive phenotypes,28 which appear to be very similar to those observed in TORC2 mutants (Fig. 3).

TORC2-dependent activation of Gad8 regulates cell cycle at G1/S and G2/M

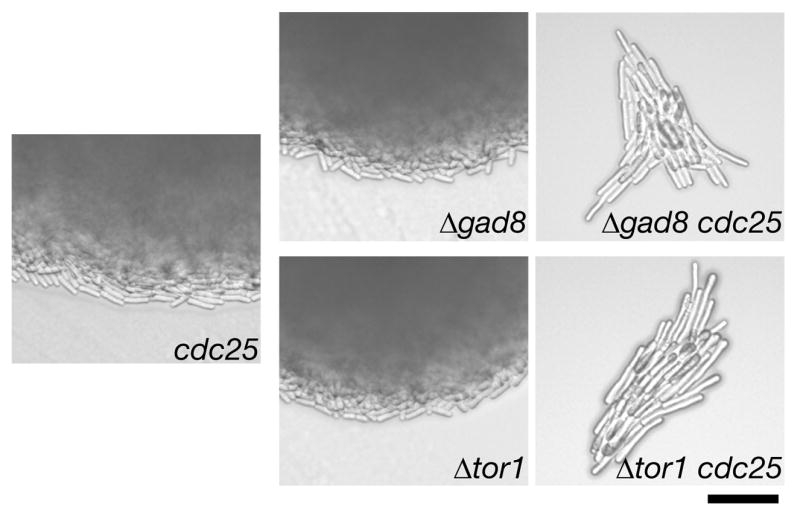

In comparison to the wild type, cells lacking functional Sin1 divide at a longer cell size, implying that the timing of mitotic initiation is delayed.10 Elongated cell morphology with 2C DNA content was also reported with Δtor126 and Δgad828 mutants, implying that the TORC2–Gad8 pathway promotes the initiation of mitosis. Therefore, we tested whether the components of this pathway show any genetic interaction with cdc25-22, a temperature-sensitive mutation of the Cdc25 phosphatase that activates Cdc2 kinase at G2/M.45 After crossing the Δgad8 and Δtor1 mutants with a cdc25-22 strain, the germinated double mutants formed microcolonies, exhibiting a cell cycle arrest phenotype with highly elongated morphology (Fig. 5). Furthermore, very similar phenotypes were observed also when the cdc25-22 mutation was introduced to the Δsin1 and Δste20 strains (data not shown). These results are consistent with the idea that Gad8 activated by TORC2 promotes mitotic initiation.

Figure 5.

The gad8 and TORC2 mutants exhibit a synthetic growth defect with the cdc25-22 mutation. A cdc25-22 strain (CA4231) was crossed with Δgad8 (CA5142) and Δtor1 (CA4593) mutants, followed by tetrad dissection. Colonies were photographed after 3-day incubation at 25°C. Micro colonies of Δgad8 cdc25-22 and tΔor1 cdc25-22 showed little growth even after longer incubation. Scale bar, 50 μm.

It was also reported that Δgad8, Δtor1, Δste20 and Δsin1 cells fail to arrest in G1 in response to nitrogen starvation,10,26–29 suggesting a regulatory role of Gad8 at G1/S. Therefore, we examined expression of rum1+, which encodes a CDK inhibitor required for G1 arrest after nitrogen starvation.46,47 During exponential growth (Fig. 6, 0 hr) and after nitrogen starvation, Δgad8 and Δtor1 mutants showed reduced rum1+ expression, which may contribute to their defect in the G1 arrest upon nitrogen starvation. Thus, the TORC2–Gad8 pathway appears to positively regulate expression of rum1+.

Figure 6.

Expression of the rum1+ CDK inhibitor gene is compromised in Δtor1 and Δgad8 mutants. Exponentially growing wild-type (972), Δtor1 (CA5266) and Δgad8 (CA5268) strains in EMM medium were shifted to the same medium without nitrogen source (NH4Cl), followed by rum1+ northern blotting. For the graph below, rum1+ mRNA signals were quantified and normalized with control hybridization by the act1+ probe.

DISCUSSION

Based on the earlier report that S. pombe Sin1 is required for the stress gene expression regulated by Spc1 SAPK,10 a similar function has been speculated for its orthologs in higher eukaryotes. To delve into the role of Sin1 in the cellular stress response, we in this study newly constructed sin1 null (Δsin1) strains in S. pombe and found that Δsin1 cells are not defective in the expression of the stress response genes regulated by the Spc1–Atf1 pathway. The Δsin1 mutant appears to be normal also in the H2O2-induced expression of the trr1+ gene, which is regulated by the Pap1 transcription factor.39 These observations are in a clear contrast to the previous study,10 which used a sin1-disrupted strain with a significant portion of the sin1+ ORF remained on the chromosome; therefore, a truncated form of Sin1 may have been expressed, affecting their experimental results. On the other hand, the almost entire sin1+ ORF was deleted in the Δsin1 strains used in our study to avoid possible complications. Having found no impact of the Δsin1 mutation on the Spc1-regulated gene expression, the functional significance of the interaction between Sin1 and Spc1 SAPK remains to be determined. We have confirmed the interaction between Sin1 and Spc1 (our unpublished results), and the Sin1 interaction with SAPK is also conserved in humans.13 It is still possible that Sin1 affects the Spc1 functions other than the stress gene expression, such as those in mitotic initiation.7–9

It has recently been reported that Sin1, as well as Ste20 and Wat1, interacts with Tor1 kinase31. Together with the genetic data presented in this study, these observations strongly suggest that, like Sin1 orthologs in other eukaryotes, Sin1 is a component of TORC2-like complex in S. pombe. Although TORC2 is essential for viability in budding yeast,16–18 the Δsin1, Δtor1, Δste20 and Δwat1 mutants are all viable, indicating that S. pombe TORC2 is not essential for growth under normal conditions. However, these mutants are sensitive to high osmolarity and temperatures, implicating TORC2 in cellular survival of stressful conditions. Among the components of TORC2, we noticed that phenotypes caused by the loss of Wat1 are slightly different from those of the Δsin1, Δtor1 and Δste20 mutants. Δwat1 cells show only mild osmosensitivity, which may indicate that TORC2 is partially functional even in the absence of Wat1. However, the temperature sensitivity of the Δwat1 mutant is more severe than that of the other TORC2 and gad8 mutants. Like its ortholog Lst8 in budding yeast and mammals,16 Wat1 is also a component of TORC1.48 Therefore, it is probably not surprising that the Δwat1 mutant shows additional defects comparing to the TORC2-specific mutants.

Data presented here strongly suggest that S. pombe TORC2 is required for the phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif in the AGC-family kinase Gad8. Functional TORC2 is essential for the Gad8 activity, because the phenotypes of the Δgad8 mutant are indistinguishable from those of the Δtor1, Δsin1 and Δste20 mutants, including sterility, stress hypersensitivity and cell cycle defects. The phenotypic similarity between the gad8 and TORC2 mutants also suggests that Gad8 is a major downstream target of S. pombe TORC2. An emerging model from recent TOR studies in budding yeast and mammals is that the two distinct TOR complexes, TORC1 and TORC2, phosphorylate and activate different AGC-family protein kinases.49 mTORC1 and mTORC2 in mammals phosphorylate the hydrophobic motif of S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and Akt, respectively.16 In S. cerevisiae, TORC1 regulates the AGC-family Sch9 kinase,50 while TORC2 is an activator of Ypk2, another AGC-family member regulating actin localization.51 Therefore, our finding of Gad8 regulation by TORC2 suggests that Gad8 may be a S. pombe equivalent of mammalian Akt, though it was previously proposed that Tor1–Gad8 parallels mTOR–S6K1 in mammals.28 S. pombe has two orthologs of Sch9 in S. cerevisiae, Sck152 and Sck2,53 which might be good candidates as S6K1 equivalents regulated by TORC1 in S. pombe.

In summary, Sin1 is a component of S. pombe TORC2 required for phosphorylation and activation of Gad8, an AGC-family kinase important for stress resistance and cell cycle control. Although Sin1 is not required for the SAPK-regulated stress gene expression, it is conceivable that Sin1 functions as a molecular link to coordinate the SAPK and TORC2 pathways for cellular stress survival and modulation of the cell cycle. Finally, the regulation and physiological function of Gad8 have apparent similarity to those of mammalian Akt.25 Considering the pivotal role of Akt in cancerous cell proliferation and diabetes,24, 54 the S. pombe TORC2–Gad8 pathway described here may serve as a useful model system to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of TORC2 and signaling to Akt.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Maximo for technical assistance, T. Matsumoto, E. Noguchi, T. Toda, M. Uritani, M. Yamamoto and the Yeast Genetic Resource Center Japan for reagents, and T. Powers for discussions. K.I. was a recipient of the Nihon University 2005/2006 Overseas Scholarship. This research was supported by grants from NIH (CA41996 to F.T.; GM59788 to K.S.) and the University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee (K.S.).

References

- 1.Brewster JL, de Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259:1760–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7681220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen AN, Shiozaki K. MAPping stress survival in yeasts: From the cell surface to the nucleus. In: Storey KB, Storey JM, editors. Sensing, signaling and cell adaptation. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2002. pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiozaki K, Russell P. Conjugation, meiosis and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2276–88. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson MG, Samuels M, Takeda T, Toone WM, Shieh JC, Toda T, Millar JB, Jones N. The Atf1 transcription factor is a target for the Sty1 stress-activated MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2289–301. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K, Brazma A, Jones N, Bähler J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:214–29. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millar JB, Buck V, Wilkinson MG. Pyp1 and Pyp2 PTPases dephosphorylate an osmosensing MAP kinase controlling cell size at division in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2117–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiozaki K, Russell P. Cell-cycle control linked to the extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature. 1995;378:739–43. doi: 10.1038/378739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen J, Hagan IM. Polo kinase links the stress pathway to cell cycle control and tip growth in fission yeast. Nature. 2005;435:507–12. doi: 10.1038/nature03590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson MG, Pino TS, Tournier S, Buck V, Martin H, Christiansen J, Wilkinson DG, Millar JBA. Sin1: an evolutionarily conserved component of the eukaryotic SAPK pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:4210–21. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colicelli J, Nicolette C, Birchmeier C, Rodgers L, Riggs M, Wigler M. Expression of three mammalian cDNAs that interfere with RAS function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2913–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang SZ, Roberts RM. The evolution of the Sin1 gene product, a little known protein implicated in stress responses and type I interferon signaling in vertebrates. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder W, Bushell G, Sculley T. The human stress-activated protein kinase-interacting 1 gene encodes JNK-binding proteins. Cell Signal. 2005;17:761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J, Zhang D, Kim K, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Su B. Mip1, an MEKK2-interacting protein, controls MEKK2 dimerization and activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5955–64. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5955-5964.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, Deuter-Reinhard M, Movva NR, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell. 1993;73:585–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–68. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedaman KP, Reinke A, Anderson S, Yates J, 3rd, McCaffery JM, Powers T. Tor kinases are in distinct membrane-associated protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1204–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S, Comer FI, Sasaki A, McLeod IX, Duong Y, Okumura K, Yates JR, 3rd, Parent CA, Firtel RA. TOR complex 2 integrates cell movement during chemotaxis and signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4572–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1865–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Q, Inoki K, Ikenoue T, Guan KL. Identification of Sin1 as an essential TORC2 component required for complex formation and kinase activity. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2820–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.1461206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteman EL, Cho H, Birnbaum MJ. Role of Akt/protein kinase B in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:444–51. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazil DP, Yang ZZ, Hemmings BA. Advances in protein kinase B signalling: AKTion on multiple fronts. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:233–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai M, Nakashima A, Ueno M, Ushimaru T, Aiba K, Doi H, Uritani M. Fission yeast Tor1 functions in response to various stresses including nitrogen starvation, high osmolarity, and high temperature. Curr Genet. 2001;39:166–74. doi: 10.1007/s002940100198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisman R, Choder M. The fission yeast TOR homolog, tor1+, is required for the response to starvation and other stresses via a conserved serine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7027–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuo T, Kubo Y, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M. Schizosaccharomyces pombe AGC family kinase Gad8p forms a conserved signaling module with TOR and PDK1-like kinases. EMBO J. 2003;22:3073–83. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilti N, Baumann D, Schweingruber AM, Bigler P, Schweingruber ME. Gene ste20 controls amiloride sensitivity and fertility in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr Genet. 1999;35:585–92. doi: 10.1007/s002940050456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochotorena IL, Hirata D, Kominami K, Potashkin J, Sahin F, Wentz-Hunter K, Gould KL, Sato K, Yoshida Y, Vardy L, Toda T. Conserved Wat1/Pop3 WD-repeat protein of fission yeast secures genome stability through microtubule integrity and may be involved in mRNA maturation. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2911–20. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuo T, Otsubo Y, Urano J, Tamanoi F, Yamamoto M. Loss of the TOR kinase Tor2 mimics nitrogen starvation and activates the sexual development pathway in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3154–64. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bähler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alfa C, Fantes P, Hyams J, McLeod M, Warbrick E. A laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1993. Experiments with Fission Yeast. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang LY, Shimada K, Morishita M, Shiozaki K. Response of fission yeast to toxic cations involves cooperative action of the stress-activated protein kinase Spc1/Sty1 and the Hal4 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3945–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.3945-3955.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatebe H, Shiozaki K. Identification of Cdc37 as a novel regulator of the stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5132–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5132-5142.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guan K, Dixon JE. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: An improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with Glutathione S-Transferase. Anal Biochem. 1991;192:262–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Degols G, Shiozaki K, Russell P. Activation and regulation of the Spc1 stress-activated protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2870–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn J, Findlay VJ, Dawson K, Millar JB, Jones N, Morgan BA, Toone WM. Distinct regulatory proteins control the graded transcriptional response to increasing H2O2 levels in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:805–16. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bozonet SM, Findlay VJ, Day AM, Cameron J, Veal EA, Morgan BA. Oxidation of a eukaryotic 2-Cys peroxiredoxin is a molecular switch controlling the transcriptional response to increasing levels of hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23319–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buck V, Ng SS, Ruiz-Garcia AB, Papadopoulou K, Bhatti S, Samuel JM, Anderson M, Millar JB, McInerny CJ. Fkh2p and Sep1p regulate mitotic gene transcription in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5623–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bulmer R, Pic-Taylor A, Whitehall SK, Martin KA, Millar JB, Quinn J, Morgan BA. The forkhead transcription factor Fkh2 regulates the cell division cycle of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:944–54. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.944-954.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szilagyi Z, Batta G, Enczi K, Sipiczki M. Characterisation of two novel fork-head gene homologues of Schizosaccharomyces pombe: their involvement in cell cycle and sexual differentiation. Gene. 2005;348:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kops GJ, de Ruiter ND, De Vries-Smits AM, Powell DR, Bos JL, Burgering BM. Direct control of the Forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Nature. 1999;398:630–4. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. PKB/Akt: a key mediator of cell proliferation, survival and insulin responses? J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2903–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell P, Nurse P. cdc25+ functions as an inducer in the mitotic control of fission yeast. Cell. 1986;45:145–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno S, Nurse P. Regulation of progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle by the rum1+ gene. Nature. 1994;367:236–42. doi: 10.1038/367236a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daga RR, Bolanos P, Moreno S. Regulated mRNA stability of the Cdk inhibitor Rum1 links nutrient status to cell cycle progression. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2015–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aspuria PJ, Sato T, Tamanoi F. The TSC/Rheb/TOR signaling pathway in fission yeast and mammalian cells: temperature sensitive and constitutive active mutants of TOR. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1692–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.14.4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powers T. TOR signaling and S6 kinase 1: Yeast catches up. Cell Metab. 2007;6:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urban J, Soulard A, Huber A, Lippman S, Mukhopadhyay D, Deloche O, Wanke V, Anrather D, Ammerer G, Riezman H, Broach JR, De Virgilio C, Hall MN, Loewith R. Sch9 is a major target of TORC1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2007;26:663–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamada Y, Fujioka Y, Suzuki NN, Inagaki F, Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN, Ohsumi Y. Tor2 directly phosphorylates the AGC kinase Ypk2 to regulate actin polarization. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7239–48. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7239-7248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin M, Fujita M, Culley BM, Apolinario E, Yamamoto M, Maundrell K, Hoffman CS. sck1, a high copy number suppressor of defects in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathway in fission yeast, encodes a protein homologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCH9 kinase. Genetics. 1995;140:457–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujita M, Yamamoto M. S. pombe sck2+, a second homologue of S. cerevisiae SCH9 in fission yeast, encodes a putative protein kinase closely related to PKA in function. Curr Genet. 1998;33:248–54. doi: 10.1007/s002940050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toda T, Shimanuki M, Yanagida M. Fission yeast genes that confer resistance to staurosporine encode an AP-1-like transcription factor and a protein kinase related to the mammalian ERK1/MAP2 and budding yeast FUS3 and KSS1 kinases. Genes Dev. 1991;5:60–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaits F, Degols G, Shiozaki K, Russell P. Phosphorylation and association with the transcription factor Atf1 regulate localization of Spc1/Sty1 stress-activated kinase in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1464–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]