In recent years, researchers and policy makers have focused attention on the emotional climate of the preschool classroom as an important predictor of young children’s socioemotional adjustment and early learning (Goldstein, Arnold, Rosenberg, Stowe, & Ortiz, 2001; Rimm-Kaufman, La Paro, Downey, & Pianta, 2005). Recent large-scale studies suggest that many early childhood classrooms score well on observational measures of emotional climate and classroom management. Still, a disconcertingly large number of preschool classrooms are less emotionally supportive and well-organized than is optimal for young children’s development (LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2007; NICHD ECCRN, 2000).

Transactional theories of development suggest that classrooms may become chaotic and difficult to manage as children with more behavioral difficulty engage in a spiraling cycle of emotionally negative “coercive processes” with teachers (Arnold, McWilliams, & Arnold, 1998; Conduct Problems Prevention Group, 1999; Kellam, Ling, Merisca, Brown, & Ialongo, 1998; Ritchie & Howes, 2003). Children’s negative behavior may disrupt their opportunities for learning, and teachers may become more frustrated and irritated by children’s dysregulated behavior and emotion. In contrast, teachers with more effective skills in classroom management are likely to prevent “chain reactions” of escalating emotional and behavioral difficulty in their classrooms (Goldstein et al., 2001, p. 709). Teachers who proactively reinforce children’s prosocial behaviors by maintaining well-managed, emotionally positive classrooms are likely to provide children with support for the development of self-regulation (Hyson, Hirsh-Pasek, & Rescorla, 1990; Raver, Garner, & Smith-Donald, 2007; Webster-Stratton & Taylor, 2001). One implication of this transactional framework is that intervention should target teachers’ classroom management as one way to support young children’s school readiness (Raver, 2002; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001).

On the basis of this theoretical framework, a primary aim of the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP) was to test whether intervention services could significantly improve teachers’ ability to provide positive emotional support and well-structured classroom management to their classrooms. In the CSRP model, teacher training was paired with intensive, on-site provision of mental health consultation, with social workers providing capacity-building for teachers and mental health services for children (August, Realmuto, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2001). Using a clustered randomized control trial (or RCT) design, this multi-component intervention targeted Head Start classrooms with the hypothesis that improvements in teachers’ classroom management would provide key regulatory support to children having behavioral difficulty, as well as to those children demonstrating greater self-regulatory competence. Our long-run hypothesis was that “emotions matter,” where children in treatment classrooms would show higher levels of school readiness and lower levels of behavior problems than their control-classroom-enrolled counterparts at the end of the school year. This paper tests the short-run impact of the Chicago School Readiness Project’s intervention on teachers’ classroom management practices, as an important preliminary step in assessing the benefits of this intervention.

Factors inside and outside the classroom: Rationale for multiple components of CSRP

What constitutes effective classroom management? Educational research suggests that classrooms are well-managed when teachers provide clear, firm rules and a high level of monitoring, and when they follow a set of simple, behaviorally-oriented steps to minimize children’s disruptive behavior (Arnold et al., 1998; Bear, 1998; Webster-Stratton, 1999). Research on classroom management suggests that teachers also need to be flexible in their use of rewards and sanctions, recognizing children’s compliant behavior with praise, greater responsibility, and choice, while responding to disruptive behavior in ways that do not inadvertently reinforce children for acting out (Hoy & Weinstein, 2006; Stipek & Byler, 2004). In this framework, teachers’ use of more effective classroom management strategies are hypothesized to help emotionally dysregulated children to develop more effective self-regulatory skills, while also providing lower-risk children with ongoing support (Thijs, Koomen, & van der Leij, 2006). From this perspective, teachers are viewed as adult learners who would benefit from workforce development and more extensive training in order to maintain emotionally supportive class environments that are more rewarding to teach and more conducive to learning (Webster-Stratton et al., 2001). Accordingly, we anchored the CSRP intervention in 30 hours of teacher training on effective classroom management strategies (Hoy & Weinstein, 2006; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001).

Recent research in staff development for early childhood educators suggests that teachers benefit from a collaborative model of training where their role as professionals is respected, and where both mentorship and didactic instruction are provided (Helterbran & Fennimore, 2004; Howes, James, & Ritchie, 2003). Pairing teachers with mentors or “coaches” allows teachers’ skills to be scaffolded through observational learning, practice, and reflection (Jacobs, 2001; Jones, Brown, & Aber, in press; Riley & Roach, 2006). In addition, children’s disciplinary problems have been found to contribute to teacher’s feelings of “burnout, “ and mentors or coaches may provide an important source of emotional support to teachers as they try to implement new strategies to deal with children’s disruptiveness (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Bishop, 1992; Woolfolk, Rosoff, & Hoy, 1990). We also drew from the success of several recent promising interventions that have trained adults (e.g., parents and teachers) to proactively support children’s positive behavior and to more effectively limit children’s aggressive and disruptive behavior (Barrera et al., 2002; Brotman et al., 2005; Dumas, Prinz, Smith, & Laughlin, 1999; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001).

Following these collaborative, mentoring models of workforce development and adult training, the Chicago School Readiness Project provided teachers with weekly coaching support as a way to build on didactic workshops (Fantuzzo et al., 1997; Gorman-Smith, Beidel, Brown, Lochman, & Haaga, 2003). Specifically, each classroom receiving CSRP intervention services was assigned a weekly Mental Health Consultant (MHC) who attended all 5 teacher training sessions with the teaching staff. Using a manualized approach, MHCs served as on-site “coaches,” providing encouragement and feedback on teachers’ use of the classroom management strategies that had been covered in the training sessions. For example, training sessions covered topics such as developing positive relationships with children, rewarding children who modeled well-regulated behavior through specific praise, and establishing classroom rules and routines. MHCs supported teachers to implement these management strategies by helping to identify obstacles, by adapting strategies to fit the teacher’s needs, and by jointly highlighting successes as well as areas needing further practice. MHCs also spent a substantial portion of the school year, during winter, helping teachers to reduce stress and limit burnout.

One concern in targeting teachers’ classroom practices for improvement is that we run the risk of placing responsibility for children’s behavior problems with teachers, when it may be that children’s behavioral difficulty is due to a wide range of poverty-related stressors that lie outside teachers’ control. For example, low-income children have a higher probability of exposure to family violence, exposure to community violence, and experience of material hardship (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997). As a result, children living in urban areas of concentrated poverty are at higher risk for developing externalizing and internalizing problems, with between 20% – 23% of preschoolers exhibiting high levels of symptomatology (Fantuzzo et al.,1999; Li-Grining, Votruba-Drzal, Bachman, & Chase-Lansdale, 2006). In addition, preschoolers appear to be substantially underserved by community mental health services, with less than 1% of preschoolers receiving services (Pottick & Warner, 2002; see also Yoshikawa & Knitzer, 1997). Thus a key, additional component of the CSRP model was the provision of “one-on-one,” child-focused mental health consultation to three to five children in each classroom, in the late spring of the school year. Because we are first interested in testing the respective roles of teacher training and coaching components of our model in improving classroom quality and climate, this paper is restricted to analyses of treatment impact from fall to early spring of the school year. We leave analyses of this additional intervention component as a next empirical step to be addressed in a subsequent empirical paper.

Chicago School Readiness Project’s Study Design

In many cases, interventions are implemented with the high hope that families, teachers, and children will participate as fully as possible, receiving a high “dose” of the services provided. Recent educational and clinical efficacy trials of a wide array of interventions, however, have documented that parents and teachers must manage many competing demands for their time: In many cases, adults attend slightly more than half of the trainings that are offered (Webster-Stratton et al., 2001). For example, in a number of recent, successful school-based interventions, 63% of teachers and 21% to 72% of parents attended at least one session of multi-session training programs, with adults attending 5 to 6 sessions, on average, out of the 10 to 12 sessions offered (Barrera et al., 2002; Lochman & Wells, 2003). In addition, it is difficult to untangle causal influences when analyzing the relations between teachers’ classroom management skills and teacher training. For instance, teachers who are more reticent or unsure of their classroom management skills might feel uncertain, untrusting, or uncomfortable reaching out for additional training, mentoring, or support from their principals or agency supervisors.

To be able to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy of classroom-based interventions, randomized (or experimental) research designs have increasingly been relied upon as the “gold standard” on which to assess whether interventions work, yielding estimates of the amount of improvement in classroom quality that can be expected from the introduction of a new curriculum or set of instructional practices (Bloom, 2005; Love et al., 2002; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Congruent with this recent trend, we use an RCT design and analyses that focused on our “intent to treat.” Intent-to-treat analysis compares all classrooms randomly assigned to treatment to those assigned to the control group, estimating an average impact on classroom quality across all those classrooms (or teachers) regardless of whether they participated in a large or small number of trainings or other related intervention services. These analyses provide a statistically conservative or “lower bound” estimate of treatment impact on classroom quality, because the average impact of the intervention is calculated across a range of types of classrooms and teachers, including teachers who “take up” only some of the services, some of the time, as well as those few teachers who were randomly assigned to the intervention but did not participate in any of the trainings. It is for this reason that intent-to-treat analyses are so valuable: Those estimates provide an index of what can reasonably be expected when a policy or intervention is implemented, under “real world” conditions where teachers, classrooms, or agencies may vary substantially in their willingness or ability to participate in the intervention.1

An additional policy-based critique might be that Mental Health Consultants (MHCs) bring “an extra pair of hands” to the classroom in addition to their clinical expertise. To control for improvements in adult-child ratio introduced by the presence of MHCs in treatment classrooms, control group classrooms were assigned a lower-cost, Teacher’s Aide for the same amount of time per week. Such a contrast is likely to be of critical importance to policy makers and local school administrations as they weigh a set of costly budgetary choices in supporting program improvement.

In sum, this experimental design allowed us to compare classrooms randomly assigned either to the control condition or to the intervention condition. In keeping with lessons learned from the past research outlined earlier, the CSRP intervention condition included four sequential segments of service provision. These components of service provision included a teacher training component in the fall (with a booster training in mid-winter for new staff in the event of teacher turnover), the MHCs’ provision of “coaching” of the strategies learned in teacher training in fall and winter, the MHCs’ support for teachers’ stress reduction in the winter, and their provision of “one-on-one” direct consultation services to children in the spring. These services were guided by three principles, including cultural competence, sustainability, and the importance of collaboration between MHCs and teachers.

Using this experimental design and this model of intervention, what were the goals of this research project? Our long-term goal was to test whether this package of classroom-based services reduces children’s risk of behavioral difficulty and increases their chances of school readiness by improving teachers’ classroom practices. While there have been a large number of experimental prevention trials targeting parenting practices for families with children with elevated behavior problems (for reviews, see Brotman et al., 2005; Raver, 2002; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001), we know of very few classroom-based interventions aimed at supporting teachers’ practices in preschool settings. Yet, early educational settings represent a promising opportunity for interventions targeting children’s socioemotional difficulties (Arnold et al., 2006; Berryhill & Prinz, 2003; Webster-Stratton, 1999).

The more immediate goal for the following study was to test whether CSRP’s intervention services had an impact on teachers’ management of children’s disruptive behavior and on teachers’ ability to foster an emotionally positive classroom climate. To our knowledge, ours is the first RCT-designed trial of a classroom-based model that tests a teacher-training and mental health consultation model in early educational classrooms (see Gorman-Smith et al., 2003). In addition, a strength of this study is that we experimentally test whether teachers’ practices and classroom quality can be improved in community-based contexts where program administrators struggle to meet the needs of economically disadvantaged families. Informed by a developmental-ecological perspective highlighting the embeddedness of children and classrooms in local institutions and neighborhoods, CSRP recruited participating Head Start-funded sites on the basis of their spatial location in seven urban neighborhoods characterized by high rates of poverty (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Henry, 2004). Our aim was to test the impact of the intervention across a wide range of sites that varied in their program quality and level of institutional readiness. In so doing, our goal was to focus on important sources of support and opportunities for program improvement in early educational settings that must stretch to make fiscal ends meet.

Method

Participants

The CSRP intervention was implemented for two cohorts of teachers (as well as for the children enrolled in their classrooms), with Cohort 1 participating from fall to spring in 2004–05 and Cohort 2 participating from fall to spring in 2005–06. As with other recent efficacy trials implemented with multiple cohorts across time, regions, or racially segregated neighborhoods, the sites enrolled in Cohorts 1 and 2 differed on a wide array of program-level and demographic characteristics, and therefore cohort membership was included as a covariate in all analyses (see, for example, Gross et al., 2003).

Ninety-four teachers agreed to participate in the study during the site selection process (see below), welcoming CSRP research and intervention staff into their classrooms to conduct classroom observations, to provide classroom-based services, etc. Of those teachers, 65 (69%) consented to complete teacher surveys (e.g., demographic characteristics, values, and beliefs about teaching practices). Among teachers willing to provide survey data, teachers were 40-years-old on average (SD = 11), nearly all teachers were female (97%), and most teachers belonged to an ethnic minority group (70% of teachers were African American, 20% were Latina, and 10% were European American). A majority of teachers held an associate’s degree or higher, with over one-quarter having a high school degree or some college experience, almost one-half holding an associate’s degree, and nearly one-quarter having a bachelor’s degree or higher. Post-randomization statistical analyses revealed no statistically significant differences between teachers in the treatment vs. control groups for these demographic and educational variables.

A total of 87 teachers participated in CSRP at baseline. The number of teachers increased to 90 by the spring. This net increase reflected the entry of seven more teachers and the exit of four teachers who either moved or quit during the school year. The two cohorts of teachers were also pooled into a single dataset (n = 90), with cohort membership included in all analyses as a covariate.

At baseline, a total of 543 children participated in CSRP. By the spring, the number of participating children was reduced to 509. This attrition was due to the exit and entry of two groups of children. The group of 543 children was reduced when 88 children exited the study, leaving 455 children who entered the study at baseline and remaining in the study throughout the school year. In addition to the original group at baseline, 59 children entered the study later in the school year, with five of these children subsequently exiting and 54 of them remaining in the study. Thus, there were 509 children (455 children who entered at baseline and 54 children who entered after baseline) participating in the study by the spring. Nearly all of the exits were due to children voluntarily leaving the Head Start program, though one child was requested to leave the Head Start program and one parent opted to withdraw her child from participating in CSRP.

Procedure

Site selection

In an effort to balance generalizability and feasibility, preschool sites were selected on the basis of (a) receipt of Head Start funding, (b) having two or more classrooms that offered “full day” programming, and (c) location in one of seven high-poverty neighborhoods that were selected on the basis of six exclusionary criteria. Of Chicago’s 70 neighborhood areas, 57 were excluded based on one or more of the following criteria: (a) poverty rates of below 40% among families with related children under age five; (b) fewer than 400 Head Start eligible children; (c) more than 15% decrease in poor families due to Chicago Housing Authority demolition and/or gentrification; (d) crime rate below median level; and (e) ethnic composition (e.g., large % population Lithuanian) for which ethnically similar “matches” could not be found in other neighborhoods. This process yielded 13 eligible neighborhoods, seven of which were selected on the basis of spatial contiguity and distance from the research office to meet feasibility needs. CSRP staff completed block-by-block surveys of all seven neighborhoods, identifying all child-serving agencies that might potentially provide Head Start-funded preschool services, including both community-based organizations and public schools. All identified sites were telephoned to determine if they met the site selection criteria (including receipt of Head Start funding, etc.). CSRP staff members then contacted and met with the head administrators and teaching staff at eligible sites to explain the research project fully and to offer them the opportunity to self-nominate for participation in the research project. Self-nomination included completion of comprehensive Memos of Understanding (MOUs). MOUs outlined CSRP staff obligations, such as services to be rendered by intervention staff, data to be collected by research staff, timelines for completion of the study, and CSRP staff responsibilities such as mandated reporting requirements. In their MOUs, all site-level staff outlined their willingness to support CSRP data collection effort, including teachers’ consent to be observed, their consent to “host” a CSRP intervention staff member (MHC or Teacher’s Aide) in their classrooms for the duration of the school year, and to participate in other details of the research project. Eighteen sites across seven neighborhoods completed the self-nomination process and were included as CSRP sites. Two classrooms from each site were initially included (N = 36 classrooms). After randomization (but two weeks before the start of the school year in Year 2), one site was informed by Chicago Public Schools that it was allocated funding for one classroom rather than two classrooms, leaving a total of 35 classrooms enrolled in the CSRP.

Randomization process

Because of our interest in the impact of intervention implemented in children’s early educational settings, randomization to treatment and control conditions was undertaken at the preschool site level (see Bloom, 2005). A challenge that researchers face when conducting settings-based experiments is that randomization yields more precise statistical estimates, greater statistical power, and a lower margin of random error when when the number of clusters, groups, or sites to be randomized is large. One risk with randomly assigning a small number of programs or sites to treatment vs. control groups is that the two groups might end up “imbalanced,” differing on key characteristics (such as school size, salary of teachers, etc.) by sheer chance. In order to guard against this risk, we used a pair-wise matching procedure recommended for clustered random assignment studies in education research (Bloom, 2005). Specifically, an algorithm was used to compute the numeric distance from each site to every other site along 14 different continuous variables, including teacher, child, and site characteristics likely to be related to the outcome variables of interest (e.g., the average annual salary of teachers, the education level of teachers, the total number of 3- to 5-year-old children served, the percent of children who were African American, etc.). All variables employed were drawn from Head Start Program Information Report data collected by each site and reported annually to the federal government.

To conduct random assignment of matched pairs to the intervention and control groups, a MatLab uniform random numbers generator was employed to generate, in sequence, five (for Cohort 1) random numbers ranging from 0–1 that were assigned to the first site in each of the five pairs. The first site in each pair was assigned to the intervention or control group based on the randomly generated number, and the second school in the pair was, therefore, assigned to the other group. After random assignment, the two groups were compared across the 14 teacher, child, and site variables employed in the matching procedures. As expected, the two groups did not differ significantly on any of these characteristics and η2 values. This process was repeated for the eight sites in Cohort 2, with no statistically significant differences found between treatment- and control-assigned groups of sites on any of the 14 teacher, child, and site variables.2

Teachers’ receipt of treatment group services: Training

All treatment-assigned teachers (including lead teachers and assistant teachers) were invited to participate in five trainings on Saturdays, each lasting six hours. A behaviorally- and evidence-based teacher training package was selected and purchased, and a seasoned trainer with Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) qualifications delivered the 30 hours of teacher training over fall and winter, adapting the Incredible Years teacher training module (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2004). Teachers were reimbursed $15 per hour for their participation. Examination of rates of participation suggests that 75% of teachers participated in at least one training and 63% of teachers participated in more than half of the trainings. Each teacher spent an average of 18 hours (SD = 12) in training from September through March, with each classroom receiving an average of 50 training hours (SD = 26) across teachers in each classroom.

Teachers’ receipt of treatment group services: Mental health consultation

Based on prior research on the importance of pairing teacher training with coaching, teachers received placement of a MHC with a master’s degree in Social Work in their classrooms one morning a week (see Aber, Brown, & Jones, 2003; Gorman-Smith et al., 2003). MHCs were trained following a manualized approach and were matched to sites on the basis of racial/ethnic and cultural similarity, Spanish proficiency, and the judgment of supervisory staff (a master’s level Intervention Coordinator). MHCs were introduced to the teaching staff in the classrooms to which they were assigned in September of the school year. MHCs were expected to provide equivalent hours of service to each site, regardless of teachers’ participation in the training sessions. MHCs were also required to complete service provision forms designed to heighten their sense of accountability to CSRP and to their classroom placement. In addition to their role as “coaches,” MHCs maintained stress reduction roles in the winter of the school year. In March, April, and May, MHCs were free to work individually (or “one-on-one”) to provide child-focused consultation with a small number of children in the classroom after obtaining a second written parental consent.

MHCs provided an average of 4.54 hours (SD = 0.45) of weekly service and 82 hours (SD = 12) of total service to classrooms from September through March, with the variability in MHCs’ hours due to school holidays, snow days, illness, and the like. On average, classrooms received a total of 132 hours (SD = 28) of both teacher training and mental health consultation during this time period.

Teachers’ receipt of control group services: Staffing support

Teachers in preschool sites that were randomly assigned to the control group were given staffing support. Teacher’s Aides were hired to provide staffing support in control classrooms to ensure that the teacher-student ratio was similar across treatment and control sites. Teacher’s Aides provided weekly staffing to classrooms from September through March, yielding an average of 5.18 (SD = 0.99) hours of service per week, in classrooms.

Written parental consent to participate

All parents in two classrooms per site were invited to allow their children to participate prior to collection of baseline data in October of the school year. Rates of consent ranged from 66% to 100% across all sites (M = 91%, SD = 7%). All child-level and teacher-child observations were restricted to those children for whom consent was obtained. No identifying information was obtained for children who were not enrolled in the study. CSRP classrooms included 67% of children who were identified as African American and 26% as Latino/a, with 20 classrooms of racial compositions greater than 80% African American and 5 classrooms greater than 80% Latino/a.

Classroom observation protocol

A cadre of 12 trained observers (blind to intervention status of each site as well as to the approaches taken by training and MHCs) collected classroom-level data using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; La Paro, Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004) and the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale, revised edition (ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2003). This group of observers was comprised of both graduate students and full-time research staff, all of whom had at least a bachelor’s degree. Half of the observers were African American and the other half were Caucasian or Asian, so that the race of the observers matched the race of the majority of children in the observed classroom roughly half of the time. All of the observers were female. Observers underwent training with one of the primary authors of the CLASS and certified trainers for the ECERS-R, including a practice observation in a demonstration site not presently enrolled in the study. The CLASS was collected in each classroom at four points throughout the school-year (with data from September and March included in this report). For each month of data collection, observers were present in each classroom for one day. CLASS observations were scheduled on days when intervention staff (e.g., MHCs) were not in classrooms, so that observers’ ratings would not be affected by presence of CSRP intervention staff. Observations were completed “live” on-site during three sessions on each observation day, including breakfast, “circle time/free play,” and lunch. The resultant data utilize the mean scores across these three observation sessions, averaged between coders for those observations that were double-coded.

Measures

Dependent measures of treatment impact

The CLASS (La Paro et al., 2004) was used to test whether our intervention had an impact on classroom quality, with four scales representing important indicators of classrooms’ emotional climate (see LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2007). These indicators included 7-point Likert scores on positive climate, negative climate, teacher sensitivity, and behavior management. The positive climate score captured the emotional tone of the classroom, focusing on teachers’ enjoyment of the children and enthusiasm for teaching. The negative climate score reflected teachers’ expressions of anger, sarcasm, or harshness. Teacher sensitivity measured teachers’ responsiveness to the children’s needs or the extent to which they provided a “secure base” for the children. The final indicator, behavior management, captured teachers’ ways of structuring the classroom so that the children knew what was expected of them, as well as the use of appropriate redirection when children demonstrated challenging behavior. Three-quarters of the observations were double-coded “live” by two observers to gauge inter-rater reliability. Because measures were coded on an ordinal scale from 1 to 7, inter-rater reliability was established via calculation of intraclass correlation values (α), which indicated adequate to high levels of inter-observer agreement (positive climate, α = .82; negative climate, α = .70; teacher sensitivity, α = .77; behavior management, α = .66).

Class-level covariates

In order to control for the variability in sites’ classroom quality, baseline measures of the ECERS-R and CLASS variables (collected in fall) were included as covariates in all analyses. The ECERS-R (Harms et al., 2003) is a widely used research tool used to measure early childhood classroom quality across a wide range of constructs. Based on 43 items, the ECERS-R provides an observational snapshot of the “use of space, materials and experiences to enhance children’s development, daily schedule, and supervision” where each item is scored from one to seven (ranging from 1 = “Inadequate” to 7 = “Excellent”; Harms et al., 2003). The ECERS-R data were collected during the fall of each year by the same cadre of observers who collected the CLASS data, with 43% of the ECERS-R observations double-coded for purposes of reliability (α =.87 for the ECERS-R Total Score). In addition, the number of children and the number of teachers observed in each classroom in September and in March were also included as covariates in all intent-to-treat analyses, to control for the potential confounds of differences in class size or staffing ratios at both time points.

Attrition was much less of a concern among teachers than among children. Indeed, less than 5% (4/87) of the teachers who participated in the fall exited the study, whereas 16% (88/543) of the children who participated in the fall exited the study. Because the number of teachers exiting the study was too small to analyze comparatively, attrition analyses were limited to children. In order to conduct attrition analyses, child-level demographic characteristics were also included in the following analyses. These included (a) child membership in race/ethnic categories of African American versus Latino/a; (b) child gender; (c) child age; (d) household family structure; (e) maternal education; (f) maternal employment, coded categorically as no employment (0–9 hours per week), part-time employment (10–34 hours per week), or full-time employment (35 or more hours per week); (g) family income-to-needs ratio; and (h) families’ use of TANF assistance.

Results

To test the short-term impact of our intervention, several analyses were conducted. First, attrition analyses were conducted to determine whether there was differential retention of children across treatment and control conditions. Second, descriptive analyses were conducted to analyze rates of participation for the treatment group, as well as to provide a descriptive portrait of the types of programs and their quality. Third, treatment impacts on classroom quality over time were examined using an intent-to-treat analysis. That is, all data for all classrooms and all teachers were analyzed, regardless of attrition, missing data status, or level of participation. As August and others have argued, “This is a conservative model that guarantees greater comparability between program and control families than a model in which only help-seeking volunteers are included in the intervention“ (August, Lee, Bloomquist, Realmuto, & Hektner, 2004, p. 156). Post-hoc repeated measures MANCOVAs were then conducted to yield covariate-adjusted estimates of means and standard deviations for treatment and control groups for the four dependent variables.

Attrition analyses

Recall that child enrollment in CSRP was affected by the exit of 93 children (88 children left the original group and five children left the group who entered later). CSRP enrollment also included 59 late entries (54 children entered late and stayed, and five children entered late and left) into the 35 Head Start classrooms over the course of the school year. We conducted two sets of attrition analyses. One set focused on 548 children, comparing the 455 children who entered at baseline and remained in the study to the 93 children who left the study. Another set focused on 514 children, comparing the 455 children who entered at baseline and stayed in the study to the 59 children who entered after baseline. Baseline demographic characteristics were compared for possible differences using analyses of variance and chi-square analyses with standard errors adjusted for classroom-level clustering. Results of these analyses suggest there were no statistically significant differences between children who stayed in the program versus those children who exited early. Results examining late entry suggest that there were no differences between fall-enrolled children and children enrolled later in the year, with the one exception that children who entered the sample later in the year were somewhat younger (MLate Entrant = 3.70, SDLate Entrant = .74, MFall Entrant = 4.20, SDFall Entrant = .57, t(33) = 4.09, p < .001).

A second key concern is whether different types of children exited and entered the treatment and control groups. Following Smolkowski et al. (2005), we used analyses of variance to examine interactions between children’s exit and entry status and their membership in the treatment versus control group across the same range of baseline demographic characteristics. Chi-square analyses were used to compare categorical demographic characteristics. No statistically significant differences were found between enrolled children and children exiting early in either the treatment or control group across all eight demographic characteristics. Analyses of late entry suggest that more girls than boys entered CSRP classrooms late in the school year, with an equal number of girls and boys entering treatment classrooms (i.e., 13 girls and 14 boys) but a higher number of late-entering girls compared to boys entering control group classrooms (i.e., 24 girls and 8 boys; chi square (3) = 10.82, p < .01).

In sum, there were no statistically significant differences between enrolled and early-exiting groups of children for child membership in race/ethnic categories of African American versus Latino/a, child gender, child age, household family structure, maternal education, maternal employment, family income-to-needs ratio, or families’ use of TANF assistance. There were only two differences out of 16 tests conducted for comparisons of enrolled and late-entering children. Given the large literature on girls’ lower risk of disruptive and externalizing behavior, the larger proportion of girls entering control classrooms versus treatment classrooms should bias estimates of treatment impact downward rather than inflating the estimate of impact upward. Because enrolled and late-entering children are present in spring classroom assessments, the use of intent-to-treat analyses protects against the potential statistical bias that these minor demographic differences might introduce.

Descriptive analyses

Examination of means and standard deviations for fall and spring suggests that classrooms averaged 15 to 16 children (SDs ranged from 2.72 to 2.74), with some classrooms observed to have as few as eight to ten children in the classroom on a given day, and some observed to have as many as 20 children in the room. On average, classes were staffed by two adults (SDs ranged from 0.65 to 0.69), with as few as one adult and as many as four adults in the room on any given day.

Examination of the descriptive statistics for classroom quality suggests substantial variability among sites. Total scores for the ECERS-R ranged from 2.89 (“inadequate”) to 6.14 (“excellent”) at baseline (M = 4.72, SD = .81). The CLASS scores demonstrated that teachers varied widely in the emotional support that they provided for their students. For instance, March data for CLASS positive climate ranged from 2.3 to 6.3 (M = 4.95, SD = 1.1). Negative climate, or teacher’s harshness or sarcasm, showed much lower average levels, though this construct also demonstrated considerable variation across classrooms (M = 2.42, SD = 1.12). The final two constructs, teacher sensitivity and behavior management, exhibited very similar ranges to that of positive climate, with means of 4.70 and 4.65, respectively, and standard deviations of one point.

Treatment impact using intent-to-treat analyses

In this study, we employed the CLASS subscores of (a) positive classroom climate, (b) negative classroom climate, (c) teachers’ classroom management, and (d) teachers’ sensitivity in spring as dependent measures of CSRP program influence. Because these analyses involve classrooms nested within treatment and control groups, we employed Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) to account for the multilevel structure of the data. This article focuses on two levels of the hierarchy: Level 1 is the classroom level including the baseline assessment of the relevant dependent variable (e.g., classroom positive climate in the Fall) and key classroom-level covariates; Level 2 is the site level and includes exposure to intervention, which is a site-level (between-classrooms) characteristic. The impact of intervention was then modeled using two equations, with the equation at Level 1 (classroom level) specified in the following way:

where Y, classroom quality in March of class i in site j, varies as a function of a string of classroom-level covariates; B0, the intercept, is the adjusted mean classroom quality in site j after controlling for classroom covariates; and B1 through B7 are the fixed Level-1 classroom covariate effects on classroom quality in March. As mentioned earlier, these covariates include cohort membership, number of adults in the fall and spring, classroom quality in the fall, number of children in the fall and spring, and ECERS-R scores in the fall.

A second equation specifying Level 2 (site level) is then written as:

where B0, the adjusted mean classroom quality in site j, varies as a function of whether or not the site was assigned to the treatment or control group; G00 is the adjusted mean classroom quality of control group sites; and G01 is the treatment effect. Though not shown here, G10 – G70 represent the pooled within-site regression coefficients for the Level-1 covariates. The magnitude of treatment impact can then be examined, where G01 represents the average difference between treatment and control sites, controlling for all covariates. Effect sizes are calculated by dividing that difference by the total sample’s standard deviation for the measure used as the dependent variable.

Analyses for this article were conducted using the HLM 5.01 software package with full maximum likelihood estimation used for all models. HLM allows for the simultaneous estimation of variance associated with individual (within-subject) and population (between-subjects) change based on the specification of fixed- and random-effect variables in a given model (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Burchinal, Bailey, & Snyder, 1994).

Model-Testing

As shown in Column 1 of Table 1, results suggest that treatment-control group differences were statistically significant for classrooms’ positive climate in March, controlling for classrooms’ level of positive climate at baseline, t(16) = 3.00, p < .01. Of note, the estimate of the impact of treatment on classroom positive climate is larger when controlling for classrooms’ level of positive climate at baseline as well as the set of classroom covariates, t(16) = 4.98, p < .001. Examination of the unstandardized coefficient for treatment impact (in the final model) suggests that treatment leads to almost a one-point increase in positive climate, on average. This translated to an effect size of d = 0.89. There were also significant treatment-control differences for March assessment of classroom negative climate, t(16) = −2.13, p < .05. The estimate of the impact of intervention was larger for negative classroom climate when baseline measures of quality and classroom-level covariates were included in the model, t(16) = −3.72, p < .01. The effect size for treatment impact was d = 0.64 for negative climate (see Table 1 for unstandardized regression coefficients).

Table 1.

Conditional Linear Models Linking Intervention Status to Emotional Climate

| Intervention | Intervention & Covariates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate & intervention variables | B | SE | B | SE |

| Positive climate | ||||

| Intercept | .65 | .97 | 2.54 | 1.69 |

| Intervention | .90** | .30 | .98** | .20 |

| Cohort | −.41 | .27 | ||

| Number of adults, fall | −.56** | .19 | ||

| Number of adults, spring | .59 | .23 | ||

| Positive climate, fall | .73*** | .16 | .91*** | .17 |

| Number of children, fall | −.10 | .05+ | ||

| Number of children, spring | .05 | .04 | ||

| ECERS-R | −.27 | .19 | ||

|

| ||||

| Negative climate | ||||

| Intercept | 1.26*** | .28 | −.02 | 1.60 |

| Intervention | −.63* | .22 | −.72** | .19 |

| Cohort | −.34 | .30 | ||

| Number of adults, fall | .02 | .20 | ||

| Number of adults, spring | −.48** | .17 | ||

| Negative climate, fall | .72*** | .12 | .84*** | .20 |

| Number of children, fall | .05 | .05 | ||

| Number of children, spring | .08 | .06 | ||

| ECERS-R | .11 | .17 | ||

Note. ECERS-R = Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale, revised edition.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results suggest that the CSRP intervention marginally benefited teacher sensitivity, t(16) = 1.97, p = .11 with the difference between treatment and control groups statistically significant only once covariates were included, t(16) = 2.70, p < .05 (unstandardized regression coefficients are presented in Table 2). The effect size for CSRP impact on teacher sensitivity was d = 0.53. Regarding teachers’ management of children’s disruptive behavior, analyses suggest that differences between treatment and control group classrooms met trend levels of statistical significance with covariates included in the model, t(16) = 1.88, p < .10. Similar to other CLASS outcomes, treatment led to over a half of a standard deviation increase in teachers’ classroom management, d = 0.52.

Table 2.

Conditional Models Linking Intervention Status to Teacher Sensitivity and Behavior Management

| Intervention | Intervention & Covariates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate & intervention variables | B | SE | B | SE |

| Teacher sensitivity | ||||

| Intercept | 1.74* | .74 | 1.33 | 1.40 |

| Intervention | .55+ | .28 | .54* | .20 |

| Cohort | −.24 | .30 | ||

| Number of adults, fall | −.40 | .24 | ||

| Number of adults, spring | .74* | .23 | ||

| Teacher sensitivity fall | .56*** | .14 | .57** | .18 |

| Number of children, fall | .04 | .06 | ||

| Number of children, spring | .02 | .07 | ||

| ECERS-R | −.18 | .22 | ||

|

| ||||

| Behavior management | ||||

| Intercept | 1.75+ | .87 | 1.41 | 1.53 |

| Intervention | .58+ | .32 | .55+ | .29 |

| Cohort | −.49 | .36 | ||

| Adults fall | −.27 | .25 | ||

| Adults spring | .61* | .25 | ||

| Behavior management fall | .54** | .17 | .44* | .17 |

| Children fall | .00 | .05 | ||

| Children spring | .05 | .07 | ||

| ECERS-R | .01 | .20 | ||

Note. ECERS-R = Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale, revised edition.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The covariates themselves were not statistically significant predictors of classroom processes in March of the school year, with the exception of the baseline (or lagged autoregressive) term for classroom quality in September and the number of adults in the classroom in March of the school year.3

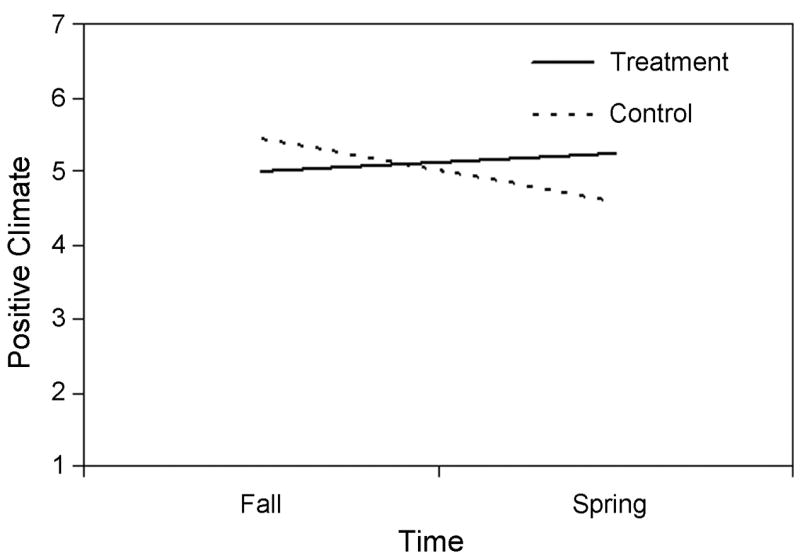

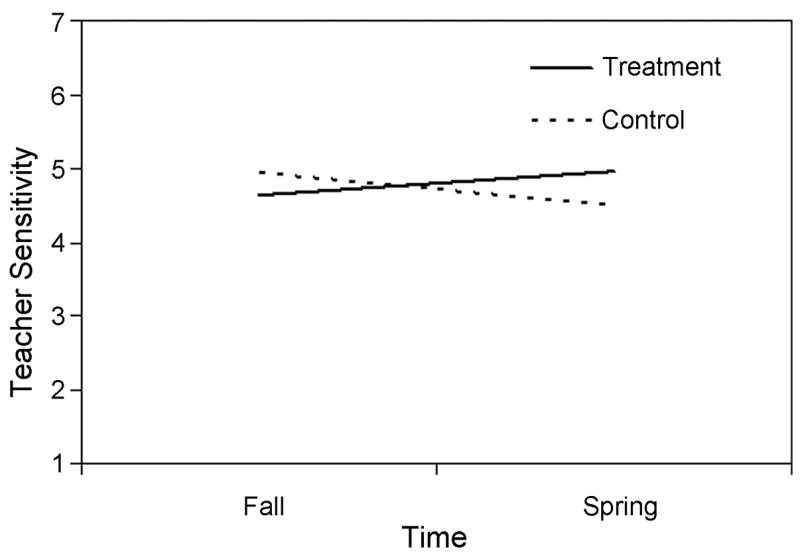

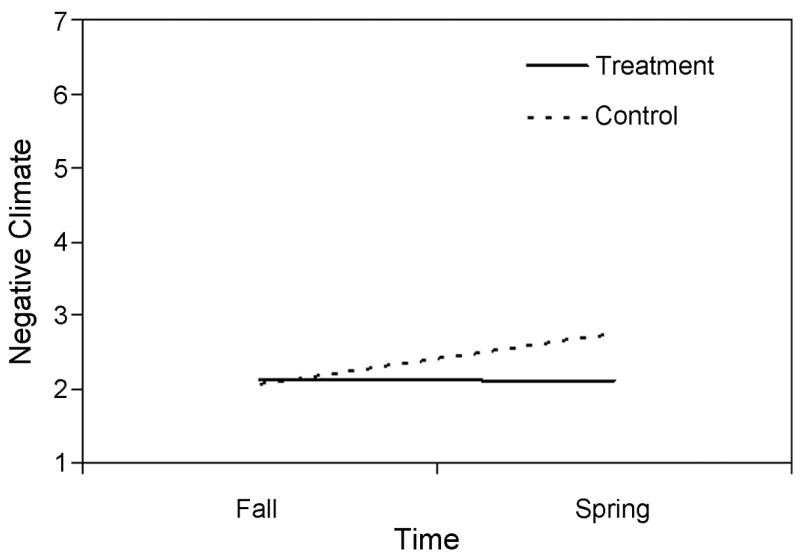

To illustrate the results of our HLM analyses, post-hoc repeated measures MANCOVAs with all covariates and treatment status were conducted using SPSS Version 13.0.01 (2004) to yield a table of covariate-adjusted means for treatment and control groups at fall and spring (see Table 3). These values were then graphed as illustrated in Figures 1 through 3 (including all outcomes except behavior management). Implications of these results are discussed below.

Table 3.

Estimated means and standard errors for dependent variables by group and time

| Control | Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | September | March | September | March |

| Positive climate | 5.44 (.19) | 4.60 (.25) | 5.00 (.19) | 5.24 (.24) |

| Negative climate | 2.07 (.16) | 2.76 (.24) | 2.13 (.16) | 2.11 (.23) |

| Teacher sensitivity | 4.94 (.22) | 4.49 (.23) | 4.64 (.22) | 4.95 (.22) |

| Classroom management | 5.05 (.23) | 4.36 (.24) | 4.58 (.22) | 4.83 (.23) |

Figure 1.

Estimated means for positive climate as a function of time of assessment and treatment group status.

Figure 3.

Estimated means for teacher sensitivity as a function of time of assessment and treatment group status.

Discussion

Similar to findings from recent, large-scale surveys, CSRP-enrolled Head Start classrooms varied in their quality, with the majority of classrooms scoring in the four to five (or “good”) range in terms of positive emotional climate, teachers’ sensitivity, and teachers’ behavioral management of their classrooms (La Paro et al., 2004; Li-Grining & Coley, 2006). Teachers generally conveyed their responsiveness to, respect for, and emotional support of their students, with our observers’ CLASS scores reflecting that many classrooms were warm, positive, well-organized places to be. A smaller proportion of classrooms struggled with inadequate levels of resources and environments (as indicated by their low ECERS-R scores and lower observed staffing patterns). Similarly, a small proportion of classrooms struggled to provide adequate classroom quality, as indicated by lower positive climate, higher negative climate, and teachers’ difficulty in monitoring and managing children’s behavior. Of particular concern was the finding that, in the absence of intervention, classroom quality substantially deteriorated over the course of the school year, as illustrated in Figures 1 through 3. Studies of classroom observational quality often note that emotional climate plummets as the school year draws to a close (Greenberg, 2007; Hamre, Pianta, Downer, & Mashburn, 2007). There could be a “honeymoon” period in the fall, with the everyday stresses of managing a classroom mounting as the year progresses.

Our analyses of the short-term impact of two components of CSRP intervention suggests that concrete steps can be taken to improve the ways that teachers manage children’s behavior and structure the emotional climate in their classrooms. Specifically, our analyses suggest that intervention classrooms experienced a substantial improvement over control classrooms in their emotional climate, with teachers demonstrating greater enthusiasm with their students, more responsiveness to their students’ needs, and lower use of harsh or emotionally negative practices in March, after participating in the CSRP intervention for 6 months. By early spring, teachers in the treatment group classrooms were marginally more likely to demonstrate improved classroom management practices, as well as showing better skills in monitoring and preventing children’s misbehavior in proactive ways, than were teachers in control group classrooms. It is important to note that CSRP was successful in improving classroom processes based on conservative intent-to-treat estimates of impact, where all treatment-assigned classrooms are included in analyses even when some teachers participated in fewer trainings than others. In addition, the control group’s receipt of a Teacher’s Aide helps us to rule out the likelihood that differences in classroom quality might have simply been because MHCs were able to lend “an extra pair of hands” during the day. As such, the CSRP components of workforce development through training and coaching are promising avenues for improving teachers’ classroom management. Our next step will be to experimentally test the hypothesis that these improvements in teachers’ classroom management lead to emotional, behavioral, and pre-academic gains made by the preschoolers enrolled in their classes.

These findings have important implications for policy professionals concerned with quality of care and education in preschool settings. Workforce development may serve as an important complement to state and national teacher education standards as ways to increase the quality of care in early educational settings (Hotz & Xiao, 2005; Hyson & Biggar, 2006). Our experimental results suggest that classroom quality can be increased by as much as one-half to three-quarters of a standard deviation if programs make a clear, sustained commitment to program improvement by offering a package of intervention services that include workshops on classroom management paired with in-class mental health consultation. This is in keeping with findings from other recent randomized trial interventions targeting teachers’ classroom practices (Gorman-Smith et al., 2003; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001).

One likely mechanism was that MHCs provided support and feedback to teachers while they tackled the difficult challenge of managing children’s emotionally negative, and disruptive behaviors. Repeated conflict with children who are disruptive, overly needy, or hard to manage has been argued to lead to teachers’ feelings of emotional distress and “burnout” marked by “emotional exhaustion” and “depersonalization” (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Morris-Rothschild & Brassard, 2006). The combination of training and MHC support appears to have diverted teachers in treatment group from engaging in these more emotionally negative cycles of interaction and may have supported teachers in maintaining sensitive, emotionally positive classroom climate.

It is also important to highlight that the CSRP was successful in partnering with teachers to support classroom quality in Head Start-funded preschools in low-income communities facing high numbers of poverty-related stressors. In recent research examining predictors of high child care quality among a talented group of African American and Latina teachers, Howes et al. (2003) point out that many definitions of effective teaching are linked to standards of high levels of formal education. Yet the workforce in early education and care is increasingly “composed of poor women of color for who access to BA level education is problematic” (p. 107). Howes et al. found that many programs, including those that are Head Start-funded, find alternative routes to supporting effective teaching, including extensive guidance, support, and supervision from more experienced practitioners in the field (see also Early et al., 2006). Moreover, Howes et al. found that the key to centers’ retention of effective teachers was teachers’ dedication to, and embeddedness within, the communities that they served.

Our findings are congruent with the observations of Howes et al. (2003), where our independent classroom observations indicated that teachers responded positively to a model that emphasized collaboration, coaching, and a shared commitment to meeting the emotional and behavioral needs of children facing high levels of disadvantage. Teaching staff in the treatment group generally demonstrated a high level of dedication to their own professional development (and by extension to the children they served), with 75% giving up at least one of their Saturdays to attend CSRP training. As many as 63% of the teaching staff attended three or more of CSRP’s Saturday trainings, which is equivalent to or higher than the amount of training and coaching found in other interventions (Aber et al., 2003; Linares et al., 2005; Lochman & Wells, 2003). For teachers who attended fewer trainings, we believe that the coaching component of CSRP, which was provided regardless of teachers’ participation in the workshops, was an especially important component of the intervention. MHCs were able to help teachers make up for missed workshop sessions by briefly reviewing the “high points” of workshop concepts during their weekly visits to teachers’ classrooms (see Webster-Stratton et al., 2001 and Lochman & Wells, 2003 for more discussion). Our analyses provide an important complement to observational studies of child care quality, by helping to identify the strengths of these early educational settings, the areas that need improvement, and the steps that can be taken to achieve higher quality in “real world,” low-income preschool contexts.

Limitations

Though this study is marked by numerous strengths, including its randomized, longitudinal design and observations of classroom quality, this investigation should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, this study’s findings are based on Head Start programs in high poverty neighborhoods in Chicago. Replication of these findings is needed to determine its generalizability to early childhood education classrooms serving low-income children in other urban and rural areas in the U.S. Second, the current study relies on two data points. Future analyses based on data collected at the end of the school year will shed light on whether improvements in classroom quality will be sustained over time or whether classroom quality will regress to the mean.

Lastly, we cannot answer the question of whether we would have obtained a statistically significant impact on classrooms if we had relied on teacher training only, without including MHCs serving a coaching and stress reduction role. Based on previous research on the importance of collaboration, reflective practice, and mentorship in supporting effective teaching, our speculation is that MHCs’ role in supporting teachers was central to the intervention’s success (Arnold et al., 2006; Fantuzzo et al., 1997; Gorman-Smith et al., 2003). Future research with multi-cell designs contrasting a multi-component model of intervention against a didactic workshop-only format would provide more definitive evidence to answer this important policy question.

Future Directions

Our findings suggest that teachers make change in the ways that they run their classrooms when they are given both extensive opportunities for training and “coaching” support in integrating newly learned skills into their daily routines. Improving the classroom climate may have benefits for both teachers and children. Specifically, we will next test whether treatment group teachers were less stressed, experienced greater confidence in their ability to manage their classrooms, and provided more instruction as a result of the CSRP. From a service provision perspective, improvements in teachers’ feelings about their jobs are not trivial: Sites struggle with high turnover in low-income preschools, raising the costs of recruiting, training, and supervising replacement staff (Gross et al., 2003). In addition, teacher stress has been associated with higher rates of child expulsion from programs (Gilliam, 2005). In short, investments in workforce development that support teachers’ provision of a positive emotional climate may have longer term payoffs to teachers and to centers, as well as to the children enrolled in teachers’ classrooms.

We will also be able to test whether children in treatment classrooms have a higher likelihood of demonstrating better regulation of emotions and behavior than do their counterparts in control condition classrooms. Teachers and students have been hypothesized to be part of a “regulatory system” (Pianta, 1999). It remains to be seen if experimental results of the CSRP intervention will replicate previous correlational findings suggesting that children demonstrate higher engagement and greater academic competence when enrolled in emotionally supportive classrooms (Pianta, La Paro, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2005; Stipek et al., 1998). Furthermore, these potential impacts may depend on the level of teachers’ psychosocial stressors or on their level of participation in the intervention. As such, we will also investigate the moderating role of teachers’ stressors and “dosage.” In addition, classroom supports for children’s behavioral regulation may be one of many pathways to support school readiness: Other recent studies point to the benefits of focusing on children’s attention, motivation, and enthusiasm for learning as alternative approaches to lowering their risk of academic and socioemotional difficulty (Dobbs, Doctoroff, Fisher, & Arnold, 2006; McWayne, Fantuzzo, & McDermott, 2004; Sonuga-Barke, Thompson, Abikoff, Klein, & Brotman, 2006). Further analyses from our research, as well as other school readiness interventions using experimental designs, will help answer these questions soon.

Figure 2.

Estimated means for negative climate as a function of time of assessment and treatment group status.

Footnotes

We recognize that this does not provide answers to developmentally-oriented questions about mechanisms that led to variability in program participation across classrooms targeted for intervention. Models of participation must take into consideration teachers’ psychosocial and demographic characteristics, the ecological characteristics of the settings in which teachers work, and multiple measures of participants’ levels of involvement in multiple components of the program. In keeping with other recent studies of the impact of multicomponent interventions in early educational settings, analyses of program participation are discussed elsewhere (CPPRG, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c).

The implications for treating the pairwise matches as fixed versus random in our models are related directly to the generalizability of the findings. In the case of (a) fixed pairwise matches, our results are generalizable to our own sample only, while in the case of (b) random pairwise matches, our results are broadly generalizable to parallel samples other than our own. We think that this stage of the science about the impact of interventions on setting-level constructs in the context of place-randomized designs is early enough in its development that it would be presumptuous for us to expect to generalize our findings beyond our current sample. In the future, we expect to build on this study’s findings and employ a broader sampling strategy that would allow us to replicate any findings and generalize more broadly. We acknowledge that we do not have adequate power to detect treatment effects if we want to generalize beyond our sample and we accept this as a significant constraint on this study. It’s also important to note the limitations of causal inference that can be drawn from tests of the null hypothesis: A lack of statistically significant difference between groups does not mean that there are no differences between them (Wilkinson & APA Task Force on Statistical Inference, 1999). Despite these constraints, we expect the results of the current study to play an important role in stimulating the future research necessary to solve the sampling issues and power constraints currently facing the field.

As mentioned earlier, we include this baseline measure (also referred to as a lagged autoregressive term) to provide a more conservative test of causal impact, recognizing that outcomes likely depend on their starting point (Cronbach & Furby, 1970).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

C. Cybele Raver, New York University.

Stephanie M. Jones, Fordham University

Christine P. Li-Grining, Loyola University Chicago

Molly Metzger, Northwestern University.

Kina Smallwood, University of Chicago.

Latriese Sardin, University of Chicago.

References

- Aber JL, Brown JL, Jones SM. Developmental trajectories toward violence in middle childhood: Course, demographic differences, and response to school-based intervention. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:324–348. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, Brown SA, Meagher S, Baker CN, Dobbs J, Doctoroff GL. Preschool-based programs for externalizing problems. Education & Treatment of Children. 2006;29:311–339. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, McWilliams L, Arnold EH. Teacher discipline and child misbehavior in day care: Untangling causality with correlational data. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:276–287. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Lee SS, Bloomquist ML, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Maintenance effects of an evidence-based preventive innovation for aggressive children living in culturally diverse, urban neighborhoods: The Early Risers effectiveness study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12:194–205. [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM, Bloomquist ML. An integrated components preventive intervention for aggressive elementary school children: The Early Risers program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:614–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Biglan A, Taylor TK, Gunn BK, Smolkowski K, Black C, et al. Early elementary school intervention to reduce conduct problems: A randomized trial with Hispanic and non-Hispanic children. Prevention Science. 2002;3:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1015443932331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear GG. School discipline in the United States: Prevention, correction, and long-term social development. School Psychology Review. 1998;27:14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill JC, Prinz RJ. Environmental interventions to enhance student adjustment: Implications for prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4:65–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1022994514767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom HS. Learning more from social experiments: Evolving analytic approaches. New York: Russell Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber L. Neighborhood Poverty: Context and consequences for children. Vol. 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman LM, Gouley KK, Chesir-Teran D, Dennis T, Kelin RG, Shrout P. Prevention for preschoolers at high risk for conduct problems: Immediate outcomes on parenting practices and child social competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:724–734. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers A, Tomic W. A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2000;16:239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Bailey DB, Snyder P. Using growth curve analysis to evaluate child change in longitudinal investigations. Journal of Early Intervention. 1994;4:403–423. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:648–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The implementation of the Fast Track program: An example of a large-scale prevention science efficacy trial. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002a;30(1):1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Evaluation of the first three years of the Fast Track prevention trial with children at high risk for adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002b;30(1):19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1014274914287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Predictor variables associated with positive Fast Track outcomes at the end of third grade. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002c;30(1):37–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Furby L. How we should measure “change” – or should we? Psychological Bulletin. 1970;74:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs J, Doctoroff GL, Fisher PH, Arnold DH. The association between preschool children’s socio-emotional functioning and their mathematical skills. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Prinz RJ, Smith EP, Laughlin J. The EARLY ALLIANCE prevention trial: An integrated set of interventions to promote competence and reduce risk for conduct disorder, substance abuse, and school failure. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:37–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1021815408272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Bryant DM, Pianta RC, Clifford RM, Burchinal MR, Ritchie S, et al. Are teachers’ education, major, and credentials related to classroom quality and children’s academic gains in pre-kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:174–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Childs S, Hampton V, Ginsburg-Block M, Coolahan KC, Debnam D. Enhancing the quality of early childhood education: A follow-up evaluation of an experiential, collaborative training model for Head Start. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1997;12:425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Stoltzfus J, Lutz MN, Hamlet H, Balraj T, Turner C, et al. An evaluation of the special needs referral process for low-income preschool children with emotional and behavioral problems. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1999;14:465–482. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Bishop N. Instructional adaptation for students at risk. Journal of Educational Research. 1992;88:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS. Prekindergarteners left behind: Expulsion rates in state prekindergarten programs (FCD Policy Brief Series No. 3) New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NE, Arnold DH, Rosenberg JL, Stowe RM, Ortiz C. Contagion of aggression in day care classrooms as a function of peer and teacher responses. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2001;93:708–719. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Beidel D, Brown TA, Lochman J, Haaga AF. Effects of teacher training and consultation on teacher behavior towards students at high risk for aggression. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M. Discussant comments. In: Li-Grining CP Chair, editor. Getting schools ready for children: Observing and stimulating change in early childhood classroom quality; Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Boston, MA.2007. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Fogg L, Webster-Stratton C, Garvey C, Julion W, Grady J. Parent training with multi-ethnic families of toddlers in day care in low-income urban neighborhoods. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:261–278. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Downer JT, Mashburn AJ. Growth models of classroom quality over the course of the year in preschool programs. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Boston, MA. 2007. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Harms T, Clifford RM, Cryer D. Early childhood environment rating scale. revised. New York: Teachers College Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Helterbran VR, Fennimore BS. Collaborative early childhood professional development: Building from a base of teacher investigation. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2004;31:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, James J, Ritchie S. Pathways to effective teaching. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2003;18:104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hotz VJ, Xiao M. The impact of minimum quality standards on firm entry, exit and product quality: The case of the child care market (Working Paper No. 11873) Cambridge, MA: NBER; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy AW, Weinstein CS. Student and teacher perspectives on classroom management. In: Evertson CM, Weinstein CS, editors. Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice and contemporary issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 181–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hyson M, Biggar H. NAEYC’s standards for early childhood professional preparation: Getting from here to there. In: Zaslow M, Martinez-Beck I, editors. Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing; 2006. pp. 283–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hyson MC, Hirsh-Pasek K, Rescorla L. The classroom practices inventory: An observation instrument based on NAEYC’s guidelines for developmentally appropriate practices for 4- and 5-year-old children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1990;5:475–494. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs GM. Providing the scaffold: A model for early childhood/primary teacher preparation. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2001;29:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Brown JL, Aber JL. Classroom settings as targets of intervention and research. In: Shinn M, Yoshikawa H, editors. The power of social settings: Transforming schools and community organizations to enhance youth development. New York: Oxford University; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Ling S, Merisca R, Brown CH, Ialongo N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:165–185. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Paro K, Pianta R, Stuhlman M. Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS): Findings from the pre-k year. The Elementary School Journal. 2004;104:409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CP, Coley RL. Child care experiences in low-income communities: Developmental quality and maternal views. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CP, Raver CC, Smallwood KM, Sardin L, Metzger MW, Jones SM. Understanding and improving classroom emotional climate in the “real world”: The role of Head Start teachers’ psychosocial stressors. 2007 Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CP, Votruba-Drzal E, Bachman HJ, Chase-Lansdale PL. Are certain preschoolers at risk in the era of welfare reform? Children’s effortful control and negative emotionality as moderators. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:1102–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Linares O, Rosbruch N, Stern MB, Edwards ME, Walker G, Abikoff HB, et al. Developing cognitive-social-emotional competencies to enhance academic learning. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:405–417. [Google Scholar]

- LoCasale-Crouch J, Konold T, Pianta R, Howes C, Burchinal M, Bryant D, et al. Observed classroom quality profiles in state-funded pre-kindergarten programs and associations with teacher, program, and classroom characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness of the Coping Power Program and of classroom intervention with aggressive children: Outcomes at a 1-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:493–515. [Google Scholar]

- Love JM, Kisker EE, Ross CM, Schochet PZ, Brooks-Gunn J, Paulsell D, et al. Final Technical Report. I. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2002. Making a difference in the lives of infants and toddlers and their families: The impacts of Early Head Start. [Google Scholar]

- McWayne CM, Fantuzzo JW, McDermott PA. Preschool competency in context: An investigation of the unique contribution of child competencies to early academic success. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:633–645. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Rothschild B, Brassard MR. Teachers’ conflict management styles: The role of attachment styles and classroom management efficacy. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Early Child Care Research Network. Characteristics and quality of child care for toddlers and preschoolers. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:116–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro K, Payne C, Cox MJ, Bradley R. The relation of kindergarten classroom environment to teacher, family, and school characteristics and child outcomes. Elementary School Journal. 2002;102:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pottick KJ, Warner LA. Update: Latest findings in children’s mental health. Policy report submitted to the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Vol. 1. New Brunswick, NJ: Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, Rutgers University; 2002. More than 115,000 disadvantaged preschoolers receive mental health services. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Report. 2002;16:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Garner P, Smith-Donald R. The roles of emotion regulation and emotion knowledge for children’s academic readiness: Are the links causal? In: Pianta RC, Cox MJ, Snow KL, editors. School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 2007. pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Riley DA, Roach MA. Helping teachers grow: Toward theory and practice of an ‘emergent curriculum’ model of staff development. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2006;33:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman S, LaParo KM, Downer JT, Pianta R. The contribution of classroom setting and quality of instruction to children’s behavior in kindergarten classrooms. The Elementary School Journal. 2005;105:377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie S, Howes C. Program practices, caregiver stability, and child-caregiver relationships. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smolkowski K, Biglan A, Barrera M, Taylor T, Black C, Blair J. Schools and homes in partnership (SHIP): Long-term effects of a preventive intervention focused on social behavior and reading skill in early elementary school. Prevention Science. 2005;6:113–125. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Thompson M, Abikoff H, Klein R, Brotman LM. Nonpharmacological intervention for preschoolers with ADHD: The case for specialized parent training. Infants and Young Children. 2006;19:142–152. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS for Windows, Rel. 13.0.1. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D, Byler P. The early childhood classroom observation measure. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:375–397. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek DJ, Feiler R, Byler P, Ryan R, Milburn S, Salmon JM. Good beginnings: What difference does the program make in preparing young children for school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19:41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Thijs JT, Koomen HM, van der Leij A. Teachers’ self-reported pedagogical practices toward socially inhibited, hyperactive, and average children. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43:635–651. [Google Scholar]