Abstract

Alternans of cardiac repolarization is associated with arrhythmias and sudden death. At the cellular level, alternans involves beat-to-beat oscillation of the action potential (AP) and possibly Ca2+ transient (CaT). Because of experimental difficulty in independently controlling the Ca2+ and electrical subsystems, mathematical modelling provides additional insights into mechanisms and causality. Pacing protocols were conducted in a canine ventricular myocyte model with the following results: 1. (I) CaT alternans results from refractoriness of the SR Ca2+ release system; alternation of the L-type calcium current (ICa(L)) has a negligible effect; (II) CaT-AP coupling during late AP occurs through the sodium-calcium exchanger (INaCa) and underlies APD alternans; (III) Increased Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) activity extends the range of CaT and APD alternans to slower frequencies and increases alternans magnitude; its decrease suppresses CaT and APD alternans, exerting an antiarrhythmic effect; (IV). Increase of the rapid delayed rectifier current (IKr) also suppresses APD alternans, but without suppressing CaT alternans. Thus, CaMKII inhibition eliminates APD alternans by eliminating its cause (CaT alternans), while IKr enhancement does so by weakening CaT-APD coupling. The simulations identify combined CaMKII inhibition and IKr enhancement as a possible antiar-rhythmic intervention.

Keywords: arrhythmia, calcium, sudden death, electrophysiology, CaMKII

INTRODUCTION

T-wave alternans is closely associated with dispersion of repolarization, ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death [47, 53]. One hypothesis states that T-wave alternans originates from alternation of cardiac repolarization at the cellular level, particularly beat-to-beat variation of the action potential (AP) duration (APD) [35, 49]. APD alternans can be electrical in nature, caused by ionic currents restitution[35]. Alternatively, alternation of the intracellular Ca2+ transient (CaT alternans) can modulate electrical activation and induce APD alternans [38, 48]. The mechanism of Ca2+ alternans and its coupling to electrical activation is not completely understood [15, 55] Several mechanisms of Ca2+ alternans have been proposed: a) restitution of L-type Ca2+ current (ICa(L)) [20]; b) refractoriness of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release channels (RyR) [50]; c) dependence of Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+-ATPase/phosholamban complex (SERCA/PLB) on [Ca2+]i [31]; d) SR Ca2+ overloading and Ca2+ wave propagation [13]; e) steep dependence of SR Ca2+ release on SR Ca2+ concentration [1, 14]. Interactions among these processes and with metabolic and/or Ca2+- dependent regulatory pathways can promote alternans [6, 30, 48].

Due to tight coupling between the Ca2+ and electrical cellular subsystems, it is difficult to determine cause and effect experimentally because the ability to independently control each subsystem is limited [23]. Even more challenging is the study of interactions between specific SR processes and sarcolemmal currents [50]. Several studies have shown that CaT alternans persists when the cell is voltage clamped either with constant voltage [13, 48, 50] or constant duration action potentials [9], suggesting that Ca2+ oscillation plays the primary role in alternans generation at moderately-fast rate of pacing.

Theoretical modeling can realize precise independent control of individual components and is therefore very useful for studying the highly interactive mechanism of alternans. While important insights have been obtained from simplified models [1, 2, 20, 55, 59], processes relevant to alternans formation such as dynamic ion accumulation and regulation by Ca2+ – dependent regulatory pathways have not been considered. Moreover, properties of CaT-AP coupling are species dependent [4, 15, 23, 50], each with remarkably different CaT and AP morphologies and durations. In addition, there is the well-documented transmural heterogeneities in AP and CaT cycling properties in the same species, which have been documented to affect the onset and amplitude of alternans [51, 68].

It has been observed that the large CaT during beat-to-beat (large-small) CaT alternans is accompanied by a short APD in some species (or certain experimental conditions) [33, 46], while in other species by a prolonged APD [48, 50]. It was suggested that the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, INaCa, is responsible for prolongation of APD during large CaT, while Ca2+ –dependent inactivation of ICa(L) is the mechanism of APD shortening [48, 59]. However , the specific mechanism of CaT-APD coupling during alternans and its modulation by the whole-cell environment require further exploration. A delicate balance between repolarizing and depolarizing currents provides for precise control of the AP time course [54]. Because this balance is modulated by [Ca2+]i, it is important to use physiologically detailed models of the cardiac myocyte for studying the interaction between the Ca2+ and electrical subsystems in the study of alternans.

Here, we investigate the cellular mechanism of alternans that involves both CaT and APD alternation. Specifically, we examine the following hypotheses: 1. Calcium alternans drives APD alternans via coupling of the Ca2+ and electrical subsystems through INaCa. 2. Calcium alternans is caused by refractory properties of the SR Ca2+ release process and steep dependence of Ca2+ release on SR Ca2+ load. 3. Repolarizing currents have a modulatory effect on alternans by influencing APD in a Ca2+-independent manner. 4. By modulating SR Ca2+ cycling, CaMKII is a major determinant of alternans and its rate dependence. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), is a regulatory pathway that modulates its activity in response to frequency, amplitude and duration of Ca2+ pulses [10, 26]. It plays an essential role in frequency-dependent augmentation of normal cardiac contractility [69] and acceleration of relaxation [12], particularly during stress or exercise. CaMKII hyperactivity can lead to structural heart disease and arrhythmias [3, 32, 75]. For the purpose of this study, an updated mathematical formulation of SR Ca2+ release (IRel) was developed. It includes activation of RyR by ICa(L) and its regulation by junctional SR Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]JSR) and CaMKII. This formulation was incorporated into theoretical models of ventricular epicardial myocytes of two species, guinea-pig [16, 43] and canine [28].

The article outline is as follows: First, reformulated IRel is validated by reproducing experimental protocols that reveal properties of the Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release (CICR) process. Second, the dependence of CaMKII on CaT and APD and its inotropic effect are simulated and compared to experiment. Third, the roles of ICa(L), SR Ca2+ fluxes and CaMKII in alternans onset and termination at moderately fast rate are studied. Fourth, the nature of bidirectional CaT-APD coupling during alternans is investigated, particularly the role of ICa(L), INaCa and IKr. Aspects of this work have been presented in abstract form [41].

METHODS

Myocyte Models

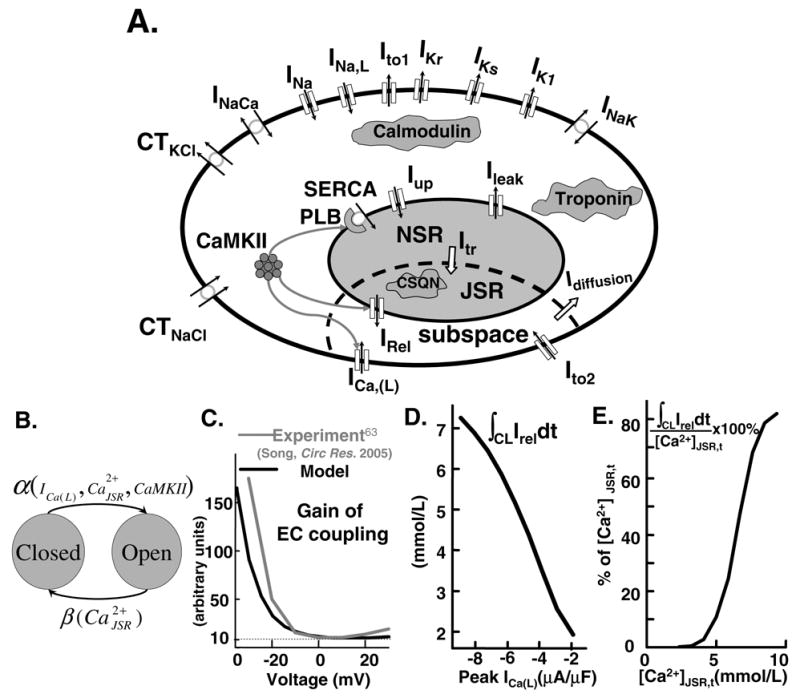

Table I in the Appendix contains parameter definitions. The theoretical LRd [16, 43] and HRd [28] models of mammalian ventricular AP provide the basis for the simulations. The LRd model is based on guinea pig data; it includes membrane ion-channel currents, pumps and exchangers, and accounts for dynamic concentration changes of Na+, K+, and Ca2+. The HRd model ( Figure 1A) is based on epicardial canine data [28] and adds to LRd processes of chloride (Cl−) homeostasis and the CaMKII regulatory pathway. The model includes the following phosphorylation targets of CaMKII: Iup, ICa(L) and IRel. Iup includes effects of CaMKII on both the SERCA pump maximal turnover rate and its affinity to Ca2+. ICa(L) and IRel interact in a subsarcolemmal restricted subspace for Ca2+ distribution. Models equations and codes can be found in the research section of http://rudylab.wustl.edu.

TABLE I.

Abbreviations and Definitions

| Abbreviation | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|

| SR | Sarcoplasmic reticulum | |

| CaMKII | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II | |

| RyR | ryanodine receptor | |

| LCC | L-type calcium channel | |

| SERCA | SR Ca2+-ATPase pump | |

| PLB | phospholamban | |

| SERCA/PLB | the SERCA/PLB complex | |

| CSQN | calsequestrin | |

| CICR | Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release process | |

| JSR | junctional SR | |

| NSR | network SR | |

| AP | action potential | mV |

| APD | AP duration at 90% repolarization | ms |

| CL | cycle length | ms |

| FDAR | frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation | |

| PFFR | positive force-frequency relation | |

| CaMKactive | Fraction of active CaMKII binding sites | |

| CaMK0 | Fraction of low affinity calmodulin CaMKII binding sites | |

| IRel | flux through RyR | mmol/L/ms |

| Itr | Ca2+ translocation flux from NSR to JSR | mmol/L/ms |

| CTNaCl | Na+ − Cl− cotransporter | mmol/L/ms |

| CTKCl | K+ − Cl− cotransporter | mmol/L/ms |

| Idiffusion | Ca2+ translocation flux from subspace to myoplasm | mmol/L/ms |

| Iup | Ca2+ uptake flux by SERCA pump | mmol/L/ms |

| Ileak | Ca2+ leak from SR | mmol/L/ms |

| [Ca2+]JSR | free Ca2+ concentration in JSR | mmol/L |

| [Ca2+]JSR,t | total Ca2+ concentration in JSR | mmol/L |

| [Ca2+]NSR | Ca2+ concentration in NSR | mmol/L |

| total Ca2+ content in SR | mmol | |

| INa | fast sodium current | μA/μF |

| INa,L | Slowly inactivating late Na+ current | μA/μF |

| ICa(L) | current through LCC | μA/μF |

| IKr | Rapid delayed rectifier K+ current | μA/μF |

| IKs | Slow delayed rectifier K+ current, | μA/μF |

| IK1 | Inward rectifier K+ current, | μA/μF |

| INaCa | current through Na+/Ca2+ exchanger | μA/μF |

| INaK | current through Na+/K+ pump | μA/μF |

| Ito1 | transient outward K+ current | μA/μF |

| IK,ATP | ATP dependent K+ current | μA/μF |

| Ito2 | Ca2+ depended transient outward (Cl−) current | μA/μF |

| ΔCa2+ | max(CaT)- min(CaT) | μmol/L |

| CaT ,[Ca2+]i | free Ca2+ concentration in myoplasm | μmol/L |

| [Ca2+]ss | free Ca2+ concentration in subspace | μmol/L |

| ratio of max(CaT)/min(CaT) |

FIG. 1.

(A) Ventricular myocyte model. Symbols are defined in Appendix Table I. Model equations are provided (including code) in research section of http://rudylab.wustl.edu. (B) SR Ca2+ release model. (C) Variable gain. Measured (grey) ([63], reproduced with permission) and simulated (black) excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) gain as function of membrane voltage. (D) Graded release. Ca2+ released by RyR (∫CL IReldt, CL=1000 ms) as function of peak ICa(L). (E) Fractional SR Ca2+ release. Ca2+ released by RyR (∫CL=1000 IReldt) as function of JSR end-diastolic loading ([Ca2+]JSR,t) in percentage of [Ca2+]JSR,t.

Calcium Induced Calcium Release Process (IRel)

We formulated a two-state (closed-open) model of SR Ca2+ release kinetics (Figure 1B) and incorporated it in LRd and HRd. We assumed that in nonfailing myocytes CICR is a spatially uniform process [50]. Based on this assumption and the assumptions that RyRs are independent and identical, the two-state model can describe the kinetics of the SR Ca2+ release process [61, 62, 64]. Transition kinetics between release (open) and no-release (closed) states depend on ICa(L) [42, 59], Ca2+ concentration in junctional SR ([Ca2+]JSR) [19, 67] and CaMKII activity. This is consistent with experiments [7, 18, 34] and early modeling work [16, 43, 58] where efficiency of release was linked to the rate of Ca2+ elevation in myoplasm and not to the level of myoplasmic Ca2+ per se. The differential equations for the model are presented in the Appendix.

Simulation Protocols

The 0.5 ms or 1 ms -80 μA/μF current stimuli were used to pace LRd or HRd, respectively. The stimulus current was assigned Cl− and/or K+ ions as charge carrier to insure charge conservation and model stability [29]. Numerical integration was performed using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick,MA) [56], with error tolerance 10−6. Steady-state was defined when all state variables showed less than 0.1% variability over 100 beats (1 min). The models were tested for convergence and long-term stability over the entire frequency range and parameter values considered. Steady-state APD (90% repolarization) and peak CaT (or Δ[Ca2+]= max(CaT)-min(CaT)) were used to create rate-adaptation curves. Results are shown for HRd simulations except for Figure 4, where alternans are also shown for LRd to demonstrate model (species) independence of the alternans phenomenon.

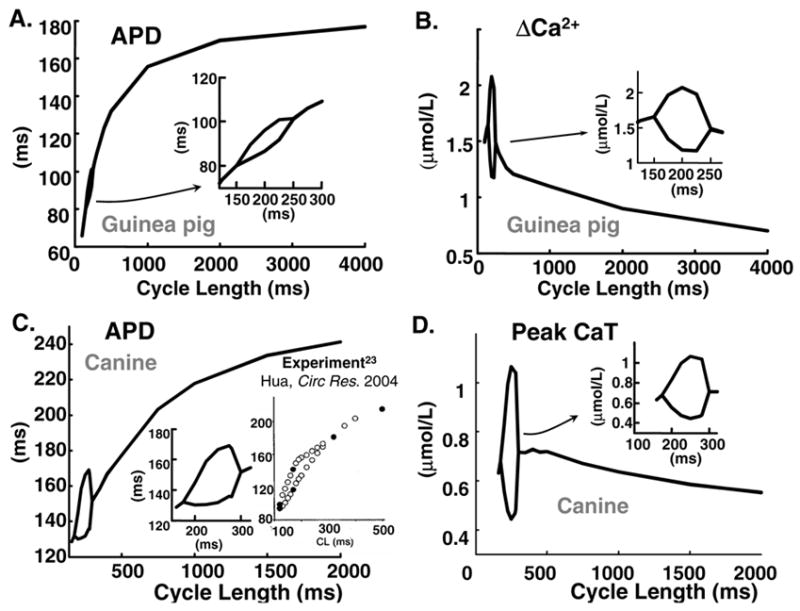

FIG. 4.

APD and CaT rate-adaptation curves. Insets show bifurcation portions on enlarged scale. (A) and (B) Guinea pig (C) and (D) Canine. Inset in (C) shows experimental data ([23], reproduced with permission).

RESULTS

MODEL PROPERTIES VALIDATION

Because we hypothesize that SR Ca2+ cycling plays a key role in CaT alternans, it is essential to verify that the models of SR Ca2+ release and CaMKII activity reproduce the experimentally observed behaviors that are relevant to alternans generation. The following sections and Figures 1, 2, and 3 provide such validation. Table VI and Table V in the Appendix contain documentation of the electrophysiological data used for the canine model validation and CaMKII data, respectively.

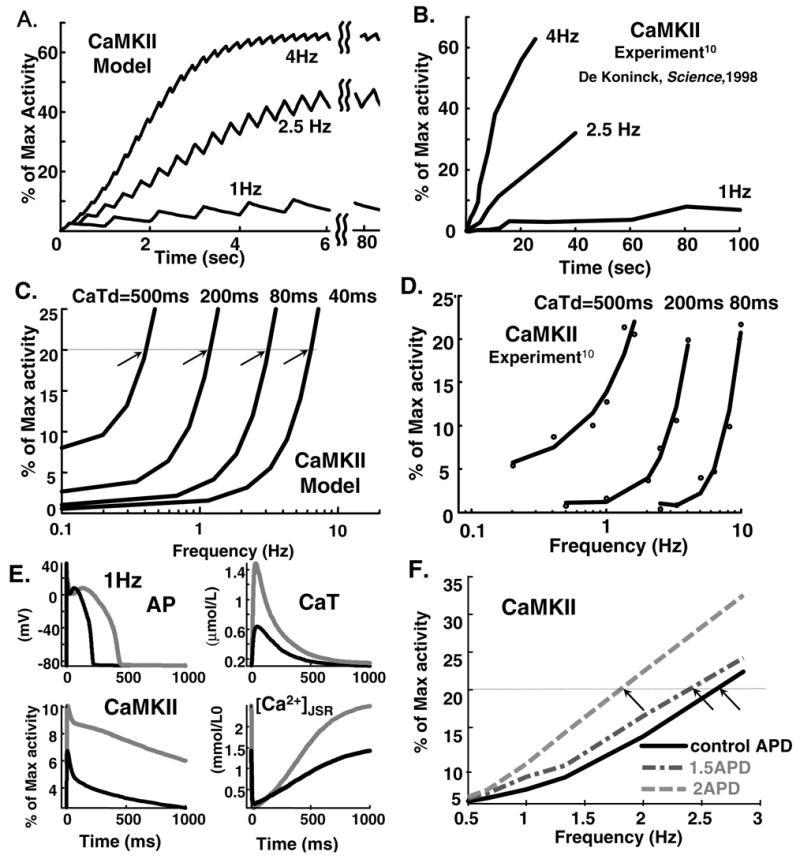

FIG. 2.

(A) Simulated and (B) experimental ([10], reproduced with permission) time course of CaMKII activity at stimulation rates of 1 Hz, 2.5 Hz and 4 Hz; CaT duration and amplitude are held constant at 200 ms and 20 μmol/L. Different time scales reflect different isoforms in model and experiment (see text). (C) Simulated and (D) measured [10] frequency dependence of CaMKII activity for indicated CaT durations (CaTd). (E) Time course of AP, CaT, CaMKII ctivity and [Ca2+]JSR at 1 Hz stimulation rate. Black: control; grey: AP-clamp pacing with wice APD. (F) CaMKII activity as function of pacing rate for different AP-clamp APDs; control (black), 1.5xAPD (dashed-dotted grey), 2xAPD (dashed grey).

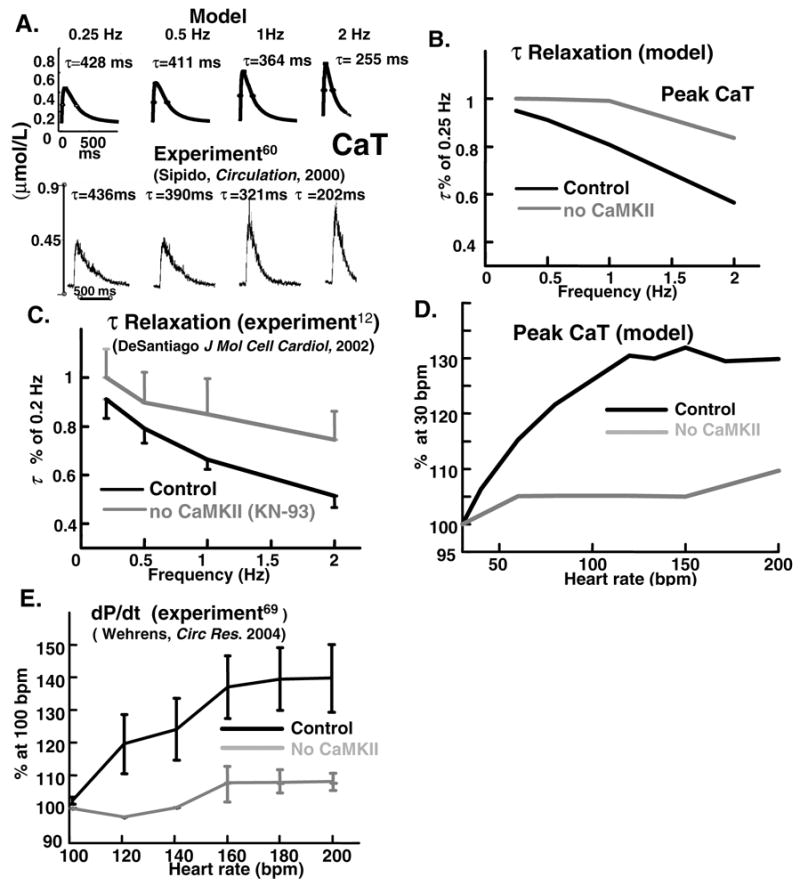

FIG. 3.

Simulated (top) and measured (bottom)([60], reproduced with permission) CaT during pacing at 0.25-,0.5-,1-, and 2-Hz. Descending limb of CaT is fit by a single exponential with time constant τ. (B) Simulated and (C) measured (mouse, force)([12], reproduced with permission) effect of CaMKII inhibition (by KN-93) on rate of CaT decline and mechanical relaxation. (D) Simulated effect of CaMKII inhibition on force-frequency (CaT-frequency) relation. (E) Corresponding experimental data ([69], reproduced with permission) (rabbit, time-derivative of ventricular pressure, dP/dt).

TABLE V.

CaMKII data

| Figure | Source | Experimental conditions |

|---|---|---|

| 3C | DeSantiago et al.[12] Fig.1B (Adapted) | 35°C, mouse, isolated myocyte. |

| 3E | Wehrens et al.[69] Fig. 3A (Adapted) | 37°, Rabbit, whole heart. |

| 2B and 2D | De Koninck and Schulman [10] Fig. 3B and Fig. 4A (Adapted) | Room temperature, in vitro CaMKII phosphorylation. |

| 7A | Diaz et al.[13]Fig.2 (Adapted). | Room temperature, perforated patch clamp, isolated rat myocyte. |

Relationship Between CaT, ICa(L), and SR Ca2+ Loading

The SR Ca2+ release model is validated by reproducing a number of key properties of excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) that determine CaT: A. Variable Gain: Ca2+ influx via ICa(L) is an order of magnitude smaller than the Ca2+ flux via RyR. The ratio IRel/ICa(L) (or CaT/ICa(L)) [63] is ECC gain; it depends on membrane voltage (variable gain). B. Graded Release. SR Ca2+ release and consequently CaT are under tight control of ICa(L), i.e., the magnitude of IRel is graded with the amplitude of ICa(L). C. Fractional SR Ca2+ Release. Percent of total available SR Ca2+([Ca2+]JSR,t) released via RyR. Experiments show that fractional release is a steep non-linear function of [Ca2+]JSR,t [57]. The above properties of ECC are often evaluated experimentally when exploring the mechanisms underlying alternans and arrhythmias [13, 50].

Figure 1C shows ECC gain (ratio of to peak ICa(L)) at different membrane voltages. is ratio of max(CaT) to min(CaT), a definition consistent with experimental measurements of CaT as peak to minimum fluorescence ratio [63]. The cell was clamped to −40 mV for 50 ms, followed by 50 ms pulse to varying voltages. Both experimental [63] and simulated data show ECC gain to be monotonically decreasing function of voltage.

Figure 1D shows total Ca2+ released during one cycle [cycle length (CL)=1000 ms] as function of peak ICa(L). [Ca2+]JSR,t was the same (7.8 mmol/L) at the beginning of the pacing cycle for each value of ICa(L). The simulation shows an almost linear dependence of Ca2+ released on trigger Ca2+ entry.

Figure 1E shows fractional SR Ca2+ release. Note the steep dependence on [Ca2+]JSR,t at high SR loading. This strong nonlinear dependence has two consequences. At low SR Ca2+ load it helps terminate SR Ca2+ release, preventing further depletion of SR Ca2+. However, at high SR Ca2+ load its can cause Ca2+ cycling instability [13, 50, 57].

Sensitivity of CaMKII to CaT and APD

In the model-experiment comparison we use in vitro experimental results from neuronal CaMKII isoform due to lack of direct data regarding rate of CaMKII phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes. However, as shown by Gaertner et al. [22] all CaMKII isoforms have very similar catalytic and regulatory properties [5]. It should be noted that CaMKII isoforms with very similar biochemical characteristics can demonstrate remarkably different targeting properties (e.g., anchoring to target proteins) [25, 72]. Simulated CaMKII activity and steepness of frequency dependence increases at fast rate. The CaMKII model reproduces qualitatively the experimentally (in vitro) observed dependence of CaMKII activity (CaMKactive) on CaT frequency, amplitude and duration [10].

Figure 2 shows simulated (A) and measured [10] (B) time course of CaMKactive (% of maximum) at rates of 1 Hz, 2.5 Hz and 4 Hz (CaT duration and amplitude held constant at 200 ms and 20 μmol/L). Both experiment [10] and simulation show increased CaMKactive and steepness at fast rate (slope at 4 Hz is twice steeper than at 2.5 Hz). This rate dependence is due to the autocatalytic nature of the autophosphorylation reaction [27]. The different time course in model and experiment is due to faster kinetic parameters used in the simulations [28], reflecting higher activity of cardiac isoform δ compared to isoforms α and β in the experiments [22]. Figure 2 also shows simulated (C) and measured [10] (D) frequency dependence of CaMKII activity for different CaT durations, (CaTd): 500 ms, 200 ms, 80 ms, 40 ms (40 ms data are not available in experiment but included in simulation because it is comparable to CaTd in the restricted subspace). As CaTd increases the curve shifts to lower frequencies. Note that the same CaMKII activity can be reached at slower rates for longer CaT durations. For example, CaMKII activity of 20% (horizontal line) is achieved at 0.4 Hz, 1 Hz, 3 Hz, and 6 Hz for CaTd 500 ms, 200 ms, 80 ms and 40 ms, respectively (arrows). Both experiment [10] and model show a threshold phenomenon, i.e., no CaMKII activity occurs for specific CaT duration until minimal frequency is reached. Ability of CaMKII to respond to CaT frequency and morphology is important because CaMKII senses different CaT transients when tethered [26] to different targets; for example, RyR and L-type Ca2+ channel in the restricted tubular subspace experience a different CaT and consequently CaMKII activity than SERCA/PLB in the bulk myoplasm (Figure 1A). Both experiment [10] and model show a threshold phenomenon, i.e., no CaMKII activity occurs for specific CaT duration until minimal frequency is reached. In addition, model simulations show time-dependent saturation of CaMKactive (Figure 2A).

Figures 2E and 2F show modulation of CaMKII activity by APD. Panel (E) shows (clockwise) time course of AP, CaT, [Ca2+]JSR and CaMKactive at 1 Hz stimulation rate. Control AP waveform (black) is prolonged to double APD at CL=1000 ms from 215 to 430 ms (grey). The prolonged AP is used as command waveform to pace the cell to steady-state (grey lines). APD prolongation leads to dramatic increase of CaT and [Ca2+]JSR, >200% of initial values, consequently CaMKactive is increased by 75%. These simulations show that APD can modulate CaMKII activity by increasing intracellular Ca2+ loading and CaT. Panel (F) shows CaMKactive at rates from 0.5 to 3 Hz for control APD and APD increased by 50% or 100%. The same level of CaMKII activity is achieved at lower frequency for longer APD. For example, CaMKII activity of 20 % (horizontal line) is achieved at 1.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz and 2.8 Hz for 2.0, 1.5, and 1.0 control APD, respectively (arrows). The sensitivity of CaMKII activity level to APD is important when considering that CaMKII serves as a frequency sensor in different species (mouse, guinea-pig, dog, human), which have remarkably different AP morphologies and durations [4, 21, 40].

CaMKII underlies FDAR and PFFR

When the heart rate increases, greater force (implying greater CaT) [6] is generated. The increase of force (or CaT) with frequency is termed positive force-frequency relation (PFFR). At fast rate, less time is available for cardiac relaxation, or pumping Ca2+ back into the SR. In this subsection we study the effects of CaMKII on the frequency dependence of CaT amplitude and decay. These properties affect CaT in a rate-dependent manner and are therefore relevant to formation of alternans. Experimental data on CaMKII regulation in ventricular myocytes are limited. For experiment-model comparison we use the measured time-derivative of left ventricular pressure (dP/dt) [69] or twitch relaxation [12] as surrogates of CaT when data for myocyte CaT are not available.

Figure 3A shows experimental (bottom) [60] and simulated (top) CaT at different rates. Both experiment and simulation show that CaT amplitude and rate of decay increase at fast rate. Note that simulated and measured [60] peak CaT increase monotonically with pacing frequency (PFFR). The descending limb of CaT is fit by single exponential, with time constant of relaxation τ. Both experiments and simulations show that with increasing frequency, τ decreases monotonically. 10-fold increase in frequency from 0.25 Hz to 2 Hz, results in about two-fold increase of relaxation rate, with τ decreasing from 450 ms to 200 ms. This phenomenon is called Frequency-Dependent Acceleration of Relaxation (FDAR) and is essential for normal diastolic function. Complete suppression of CaMKII effect on all targets in the model (panel B, grey) slows FDAR and blunts its frequency dependence compared to control (panel B, black). Similar behavior is seen experimentally (panel C) [12].

Figures 3D and 3E show the effect of CaMKII inhibition on force-frequency relation. For control with CaMKII active (black curves), experiment (E) [69] and simulation (D) show similar 40% increase of contractility or CaT, respectively, as rate increases over the range shown. Total CaMKII inhibition greatly suppresses this rate dependence. Simulation for Figures 3 was generated by setting CaMKII activity to zero for all its targets (i.e., Iup, ICa(L) and IRel), which mimics the effect of KN-93 application to the whole cell. The agreement between model and experiment is qualitative. The onset of increased contractility (or CaT) is shifted to lower frequencies in simulations relative to experiments, reflecting the slower heart rate of canine (simulation) compared to rabbit (experiment [69]).

CaT AND APD ALTERNANS

Frequency Dependence of Alternans

Figure 4A and 4B show steady-state APD and ΔCa2+ rate dependence (adaptation curves) generated by the guinea-pig (LRd) model. Figure 4 C and 4D show similar curves for canine (HRd). As pacing rate is increased APD shortens, until it reaches a point of bifurcation at which for the same pacing rate APD oscillates between long and short values. Panels B and D show corresponding CaT adaptation curves; CaT amplitude increases at fast rate until exactly at the same frequency as APD, bifurcation occurs. The bifurcation portions of APD and CaT curves are shown in insets on expanded scales. The guinea-pig model alternates at CL from 150–250 ms, consistent with experimental data [49]. Maximal APD and CaT differences between two consecutive beats occur at CL=200 ms with magnitudes of 12 ms and 0.75 μmol/L, respectively.

The canine model alternates at CL 155–275 ms, also consistent with experimental data [23]. Maximal APD and CaT differences between two consecutive beats occur at CL= 250 ms with magnitudes of 35 ms and 0.5 μmol/L, respectively. APD and CaT curves bifurcate also when plotted against the preceding diastolic interval (not shown), as frequently presented [23, 35]. Note that the bifurcation portions of APD adaptation curves are smooth functions of CL; as CL decreases alternans amplitude increases to a maximum and then decreases [23] (Panel 4C, inset). Both canine and guinea-pig models simulations are shown in Figure 4, demonstrating model (species) independence of the alternans phenomenon. The simulated frequency ranges and amplitudes of alternans are consistent with corresponding experimental data [24, 68].

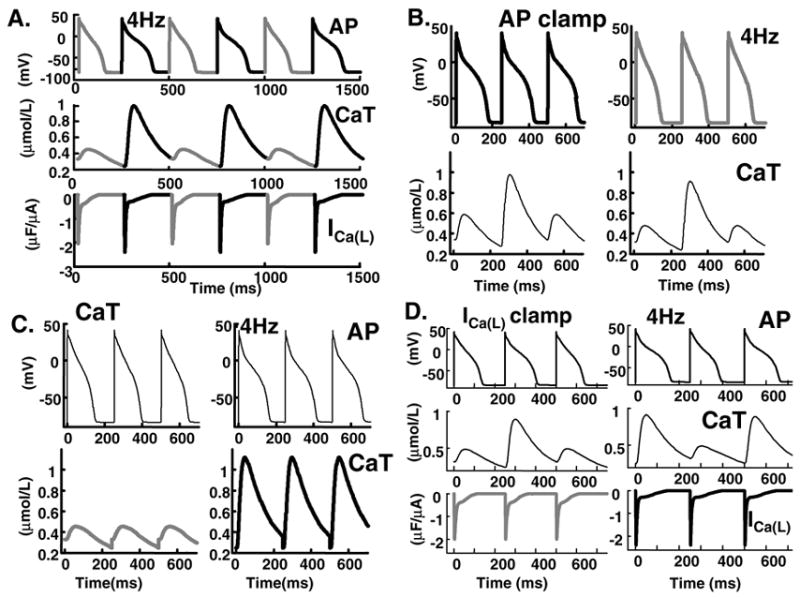

CaT-AP Coupling During Alternans and its Mechanism

To elucidate the link between APD (electrical) and CaT (mechanical) alternans we pace the cell under conditions of AP clamp or CaT clamp (Figure 5). Figure 5A shows AP (top) and CaT (bottom) during alternans at 4 Hz; note that large CaT is accompanied by long APD. In Figure 5B, steady-state behavior is shown during pacing at CL=250 ms with AP (top) clamped to either its short APD=133 ms (grey) or long APD=165 ms (black). Despite elimination of AP alternans by the clamp protocol, CaT alternans persists (Figure 5B, bottom). In Figure 5C CaT (bottom) is clamped to either its small (grey) or large (black) morphology. In either case, AP alternans is eliminated (Figure 5C, top). The SR Ca2+ subsystem continues to oscillate during clamping with large CaT morphology and the SR Ca2+ release rate is higher during large depletion than during small depletion (not shown). The results reveal that at this pacing rate, CaT alternans is causing AP alternans; in other words, oscillation of the Ca2+ subsystem is driving the APD oscillations. Simulations over the entire bifurcation range (170 < CL < 270) show the same Ca2+-driven mechanism of AP alternans.

FIG. 5.

AP and CaT clamp protocols. (A) AP (top), CaT (middle) and ICa(L)(bottom), during alternans at 4Hz. (B) AP clamp with short (grey) or long (black) AP. In spite of AP clamping (top), calcium subsystem oscillates (bottom). (C) Clamping CaT (bottom) to its small (grey) or large (black) waveform eliminates AP alternans (top). (D) Clamping ICa(L) (bottom) to its small (grey) or large (black) waveform does not eliminate AP (top) or CaT (middle) alternans.

To explore the role of ICa(L) in CaT alternans we conducted the simulations in Figure 5D. Bottom panel shows that clamping ICa(L) to either its small (grey) or large (black) morphology does not eliminate either APD or CaT alternans (top panels) indicating that alternation of SR Ca2+ release is not due to alternation of its ICa(L) trigger. However, clamping ICa(L) to either its small (grey) or large (black) morphology reduces the APD alternans amplitude from 32 ms to 21 ms or 14 ms, respectively, indicating a role of ICa(L) in CaT-AP coupling. APD alternans amplitude is defined as the difference between long and short APD.

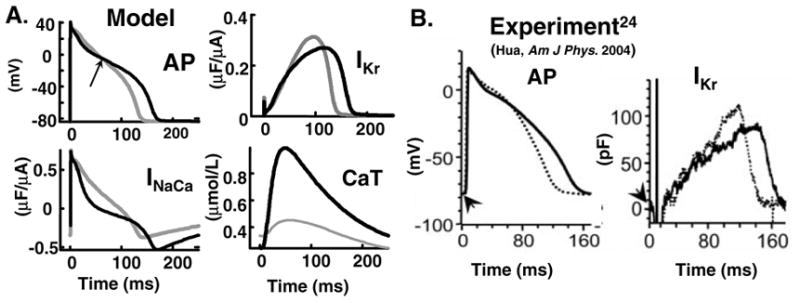

Figure 6A shows ss(clockwise) superimposed AP, IKr, CaT, and INaCa during alternans for two consecutive beats, with long (black) and short (grey) APD. The higher early plateau of the short AP (70 ms, arrow) is mainly due to enhanced ICa(L) caused by less Ca2+-dependent inactivation (Figure 5A, bottom) during the small CaT (grey). Early-plateau Ito2 is also Ca2+ –dependent, but is a small current and its effect on AP morphology changes during alternans is small. During the large CaT (black) INaCa is more inward than during the small CaT (grey), slowing AP repolarization to cause crossover of the APs and prolongation of APD. The higher plateau of the short AP and the APs crossover are in agreement with experimental data [23] (Figure 6B) from canine ventricular myocytes. The simulations identify INaCa as the major coupling link between CaT alternans and APD alternans, due to its major role late in the AP, when repolarization and APD depend on a delicate balance of currents and are easily modulated.

FIG. 6.

(A) Superimposed AP, CaT, INaCa and IKr of consecutive beats during alternans at CL=250 ms. (B) Measured (canine) ([24], reproduced with permission) AP and IKr during alternans.

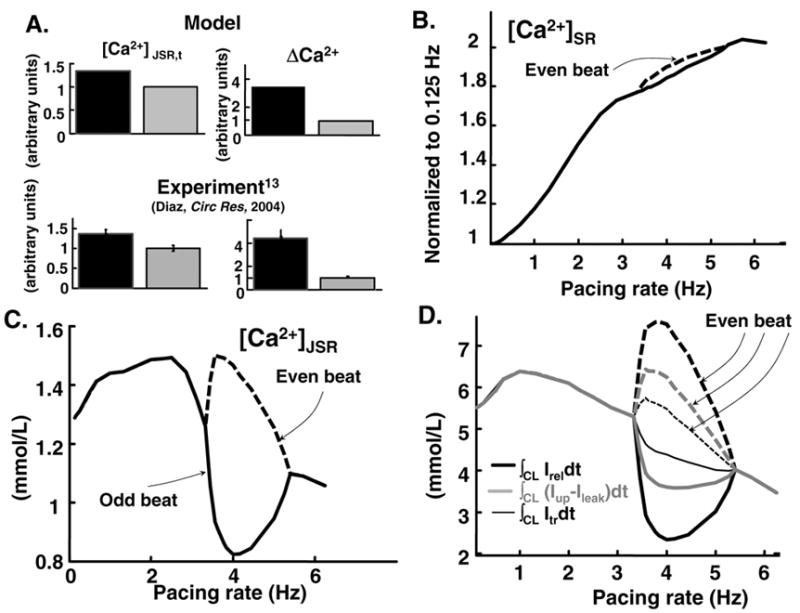

SR Ca2+ Content and CaT Alternans

To explore the role of SR Ca2+ fluxes in onset and offset of CaT alternans we conducted the simulations in Figure 7. Figure 7A shows SR releasable Ca2+ content changes during alternans at 5Hz. ΔCa2+ is shown for two different levels of SR Ca2+ loading during alternans. In the simulation (top), increase of [Ca2+]JSR by 40% leads to a four-fold increase in ΔCa2+, demonstrating that small changes in [Ca2+]JSR lead to large changes in ΔCa2+. Such steep dependence is consistent with experimental findings (bottom) [13]. Total SR Ca2+ content [JSR + network SR (NSR)] increases as function of pacing rate (Figure 7B)[45]. In addition, during alternans, change of total SR content is very small, in accordance with experiment [13, 50]. However, [Ca2+]JSR and consequently the releasable pool of Ca2+ is slightly decreased with rate after reaching a maximum at 1.5 Hz (15% decrease at 4 Hz, Figure 7C). This property of the model is consistent with experimental observations that refractoriness of the global CICR process has a time constant in the range of 0.3–1 sec [8, 50, 65].

FIG. 7.

Steady state SR Ca2+ flux balance during alternans. (A) Dependence of ΔCa2+=max(CaT)-min (CaT) on JSR Ca2+ content during alternans at 5 Hz. Simulation (top) is compared to experiment (rat)([13], reproduced with permission) (bottom). Only 40% change in [Ca2+]JSR leads to 4-fold change in ΔCa2+. [Ca2+]JSR,t= free and buffered Ca2+ concentration in JSR before release; black (grey) bars correspond to larger (smaller) [Ca2+]JSR,t, respectively. Data are normalized to small [Ca2+]JSR,t. (B) Total end-diastolic SR Ca2+ content ([Ca2+]JSR,t and [Ca2+]NSR) as function of rate. (C) Free Ca2+ in JSR ([Ca2+]JSR) as function of frequency. (D) Total Ca2+ released by RyR (∫CL IReldt, black thick line), reloaded into NSR [∫CL(Iup − Ileak)dt, grey] and translocated from NSR to JSR (∫CL Itrdt, black thin line) over one cycle, as function of frequency.

At slow rates in the absence of alternans, SR fluxes are in balance, i.e. the amount of Ca2+ transported from NSR to JSR (∫CL Itrdt, black thin line) during one beat at steady state equals the amount of Ca2+ released (∫CL IReldt, black thick line) and the net flux into the SR (∫CL(Iup−Ileak)dt, grey, Figure 7D). In addition free diastolic Ca2+ is in equilibrium over the entire SR (not shown). However, at moderately-fast rate during alternans following a large CaT (defined as even beat), NSR reloading and Ca2+ transfer to JSR is less than the amount released (Figure 7D, even beat). Consequently, less Ca2+ is available for release during the next beat (Figure 7C, odd beat) and due to the steep dependence of fractional Ca2+ release on [Ca2+]JSR,t (Figure 1E) less Ca2+ is released during this beat (Figure 7D, odd beat). Following a small CaT (odd beat), there is accumulation of releasable Ca2+ (Figure 7C, even beat) because of imbalance between SR reloading and release, resulting in a large CaT. This alternating behavior repeats to cause sustained alternans. When pacing rate is further increased (>6 Hz), time for Ca2+ accumulation after a small release is decreased and the alternans gradually disappear.

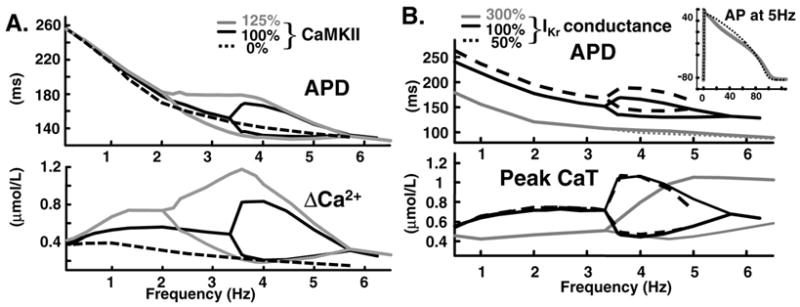

Effect of CaMKII

Figure 8A shows APD (top) and ΔCa2+ (bottom) adaptation curves for three different levels of CaMKII activity (modulated by changing the fraction of low-affinity calmodulin binding sites CaMKII0 [27], which mimics the effect of KN-93 [12]. Setting CaMKII0 to zero completely inhibits CaMKII activity. Increase of CaMKII activity by 25% shifts onset of ΔCa2+ and APD alternans to slower frequencies, from 3.3 Hz to 2 Hz, while the frequency of maximal alternans is unchanged (3.6 Hz). However, the amplitudes of ΔCa2+ and APD oscillations increase by 10 ms and 0.4 μmol/L, respectively. Increase of CaMKII activity has no effect on offset of CaT and APD alternans, while CaMKII inhibition suppresses alternans (dashed curves) thereby exerting an antiarrhythmic effect. Unfortunately, decrease of CaMKII activity blunts the PFFR ( Figure 3E, 3F) and FDAR ( Figure 3C, 3D) thereby compromising cardiac mechanical function.

FIG. 8.

(A) APD (top) and ΔCa2+ (bottom) adaptation curves for three different levels of CaMKII activity: control (100 %), 25 % elevation (125 %) or complete block (0 %). (B) Effect of IKr on APD and CaT alternans. APD (top) and CaT (bottom) adaptation curves for three different levels of IKr conductance: control (100%), 300% elevation and 50 % reduction. Inset: superimposed consecutive APs at 5 Hz for IKr increase of 300%.

Effect of IKr

In general, peak IKr amplitude is smaller at faster rates [28]. However, our simulations and experiments [23] show that during APD alternans IKr is larger during the shorter than longer AP. The simulations indicate that this behavior (large IKr at short APD) is due to combined effect of residual activation due to shorter diastolic interval (DI) after the long APD and greater activation due to high early plateau potential of the short AP.

Figure 8B shows APD (top) and CaT (bottom) adaptation curves for three different levels of IKr conductance. 50% decrease of conductance increases APD by 15 ms over the entire stimulation range (dashed line). In addition, the magnitude of APD alternans increases by 15 ms. However, CaT and magnitude of CaT alternans are not affected. Note that this modest increase of APD prevents one to one capture at 5Hz because the diastolic interval following the long APD approaches zero. Increase of IKr conductance by 200 % (note shown) decreases APD alternans magnitude by 50% (15 ms) with no effect on onset frequency and magnitude of CaT alternans. A large 3-fold increase of IKr conductance is necessary to completely eliminate APD alternans, consistent with experiment [23]. Even with such large increase, the onset frequency and magnitude of CaT alternans (not measured in the experiment) are not affected. The 300 % increase of IKr decreases APD by 50% and CaT amplitude by 50% (grey line) at slow rate; it extends the frequency range of CaT alternans by shifting its termination to 10 Hz (not shown) from 5.5 Hz. Inset shows overlapped consecutive APs at 5 Hz for 300% IKr conductance; while APDs are almost identical, there significant differences in AP morphologies, the AP plateau during small CaT (dotted) is more convex than AP during large CaT.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that at moderately-fast rate (between 3.5 and 5.5 Hz) the SR Ca2+ subsystem, strongly modulated by CaMKII, can initiate CaT alternation that induces APD alternans.

CaT Alternans

At moderately-fast rate, the guinea pig (4 – 6.5 Hz) and canine (3.5 – 5.5 Hz) models produce sustained alternans of both APD and CaT. Simulated AP and CaT clamp protocols confirm [38] that oscillation of the Ca2+ subsystem is driving the APD alternans in both species. The mechanism underlying CaT alternans is explored by evaluating the roles of the trigger for SR Ca2+ release ICa(L), SR load, SR Ca2+ fluxes and CaMKII activity during alternans. Model simulations show that refractoriness of the SR Ca2+ release process is the main mechanism of CaT alternans. Specifically, two rate-limiting processes, Iup and Itr (Figure 7D) in conjunction with steep dependence of SR Ca2+ release on SR Ca2+ load (Figure 1E) determine the onset and offset of sustained alternans at moderately-fast rates.

Itr in the model represents both (local ) RyRs intrinsic recovery from refractoriness and (global) Ca2+ diffusion [8] through the SR . While the steep dependence of release and rate of uptake are sufficient to induce alternans in the model (see also reference [70]), Itr also contributes to alternans formation(Figure 7D). In addition, the model predicts that during Ca2+ overload the SR Ca2+ cycling subsystem can oscillate even without corresponding beat-to-beat oscillations of CaT (not shown).

In contrast to previous modelling reports [20, 55], we find that alternation of ICa(L) is not necessary to evoke steady-state CaT alternans; such alternans are not eliminated under ICa(L) clamp, only reduced in amplitude (Figure 5D). This observation is consistent with experimental data [13, 48, 50] showing that contraction or CaT alternans can occur without ICa(L) fluctuations.

CaT-AP Coupling

While the magnitude of CaT alternans is comparable in guinea pig and canine (100% relative to minimum CaT, Figure 4B, 4D), that of APD alternans is twice as large in canine (20% canine, 10% guinea- pig, of maximum APD, Figure 4C, 4A), indicating stronger CaT-AP coupling in this species. These values are comparable with experimental data [23, 35, 50] that reflect modest level of CaT-APD coupling during alternans. This is in contrast to recently published simulations[55] where 50% alternation of CaT caused greatly exaggerated (more than 100%) alternation in APD. Such strong dependence of APD on CaT during alternans has never been observed experimentally [24, 30, 35, 49, 50].

While the roles of INaCa and ICa,(L) in CaT-AP coupling during alternans were discussed previously in general terms [70], precise nature of these interactions in detailed myocyte models was not addressed. The stronger CaT-AP coupling in the canine compared to guinea pig is due to differences in ion channel expression levels and kinetic properties. On the background of smaller IKr and IKs in the canine [28] in conjunction with a much smaller ICa(L) during the late AP plateau [4], CaT-induced changes in INaCa have a much greater modulatory effect on AP repolarization and APD. This makes the canine myocyte more susceptible to Ca2+-induced AP alternans and suggests that similar sensitivity to arrhythmia is characteristic of the human heart, whose cell electrophysiology and AP morphology resemble those of the canine [21]. The results show that prolongation of APD secondary to a large CaT is mainly due to large inward INaCa at the late AP plateau and repolarization phase, identifying INaCa as the major CaT-APD coupler during alternans. The other Ca2+-dependent currents, ICa(L) and Ito2, play a role in shaping the AP during its initial plateau phase, causing crossover between consecutive APs during alternans ( Figure 8A) but have a minimal effect on APD. Ito1 that contributes to APD rate adaptation [28] has little effect on AP morphology during alternans. The situation can be different, with ICa(L) playing a role in APD alternans, in species where ICa,(L) persists into the late phase of the AP (e.g. the guinea pig). and Ca2+-dependent IKs has a large conductance [17, 40]. Under such conditions, a large CaT can lead to APD shortening during alternans, due to increased Ca2+-dependent inactivation of ICa,(L).

Heart failure shifts the onset of APD alternans to slower frequencies and causes a remarkable increase in its amplitude [71]. Upregulation of INaCa has been reported in human and animal models of heart failure [6]. This observation supports the role of INaCa as the major CaT-APD coupler during alternans. It should be commented that exploration of such mechanistic details requires detailed species-specific and ionic-based cell models. It cannot be accomplished with simplified models [55, 58] where the levels of Ca2+ – dependent and voltage-dependent inactivation of ICa,(L) are treated as model parameters, not based on experimental data.

Modulation of CaT and APD Alternans by CaMKII and Repolarizing Currents

Elevated CaMKII activity, as occurs in hypertrophy and heart failure [3], extends the range of CaT alternans and consequently APD alternans to slower frequencies and increases alternans magnitude, suggesting its role in arrhythmia and sudden death in these pathologies. Decrease of CaMKII activity suppresses both CaT and APD alternans, thereby exerting an antiarrhythmic effect. Unfortunately, the decrease blunts the PFFR and FDAR (Figure 3E, 3D), thereby compromising cardiac mechanical function.

Modification of IKr has been suggested as a possible intervention for reducing APD alternans [20, 23]. Here we describe the first study of the role of Ca2+ – independent currents during Ca2+ driven APD alternans. The simulations show (Figure 8A, 8B) that only a large three fold increase of IKr can completely suppress APD alternans, which limits its potential use as antiarrhythmic intervention. Moreover, increase of IKr has no effect on the onset and magnitude of CaT alternans ( Figure 8D). Thus, unlike CaMKII inhibition that suppresses APD alternans by eliminating its cause, CaT alternans, increased IKr weakens CaT-AP coupling, thereby suppressing APD alternans by disrupting its link to persistent alternans of CaT. Similar results we obtained by modulating other repolarizing currents, namely the slow delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs), the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) and IK,ATP , the ATP-dependent K+ current (not shown). However, results are shown only for IKr, because the conductance of IKs is Ca2+-dependent, increase of IK1 markedly decreases excitability and conduction velocity [44], and IK,ATP is activated only during pathological conditions of ischemia (acidosis) [54].

These results suggest two possible antiarrhythmic strategies for alternans suppression : 1. prevention of CaT alternans by partial CaMKII inhibition; or 2. modification of the coupling between the Ca2+ and electrical subsystems by modulating repolarizing currents such as IKr or IK,ATP . A combined approach of 1 and 2 above seems reasonable, providing more flexibility for alternans suppression with minimization of deleterious effects on contractility and mechanical performance.

At very fast rate (> 7 Hz) APD alternans is primarily an electrical phenomenon. This electrical alternans (not shown) has been attributed to slow recovery from inactivation of either INa [44, 52, 66] or ICa(L) [70]. Several studies have shown that cells in the heart can be exposed to such fast and even faster rates (e.g., 11 Hz) [73] during fast ventricular tachycardia and fibrilation. APD alternans at these rates can lead to propagation failure and transition from ventricular tachycardia to fibrilation via wavebreak mechanims [73].

Limitations

A limitation of the study is that ECC spatial heterogeneity is not considered. A phenomenon associated with this heterogeneity is Ca2+ waves which are known to be arrhythmogenic [13]. However, Ca2+ waves are rarely observed in non-failing myocytes during fast pacing [30, 50], the subject of our investigation. For the same reasons (the models are based on data from non-failing myocytes), only acute up/down regulation of CaMKII was considered. The model does not include the β-adrenergic/PKA regulatory pathway that, while sharing common targets (i.e., Iup, ICa(L) and IRel) with CaMKII, by itself plays an important role in ECC and cardiac repolarization. Incorporating in the model the β-adrenergic/PKA regulatory pathway together with effects of chronic upregulation of CaMKII as occurs in heart failure [75], will be an important step in future model development and simulation studies. As was recently shown in a transgenic mice model chronic inhibition of CaMKII activity leads to upregulation of repolarizing [39] and ICa(L) [75] currents and can compensate for mechanical function impaired due to calcineurin overexpression [32].

The time constant of Itr in the model represents both (local ) RyRs intrinsic recovery from refractoriness and (global) Ca2+ diffusion [8] through the SR. Separation of these time-limiting processes requires additional experimental data that are not yet available and development of a detailed kinetic model of RyR gating. This can be important future work, considering that some studies [50] stress the importance of intrinsic RyR refractoriness in CaT alternans development. The simulations also indicate the need for detailed experimental studies of CaMKII properties in ventricular myocytes and its interactions with RyRs and SERCA/PLB during alternans.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute Merit Award R37-HL 33343 and RO1-HL 49054 (to Y.Rudy). We thank members of the Rudy Lab: Keith Decker, Dr. Greg Faber, Namit Gaur, Tom O'Hara, Dr. Ali Nekouzadeh and Jonathan Silva for helpful discussions. Special thanks got to Dr. Valentin Krinski for insightful comments on various aspects of the paper.

Appendix

Equations and parameters of the of guinea pig (LRd) and canine (HRd) models used in this study are as in previously published papers [16, 28] and in the research section of http://rudylab.wustl.edu. Definitions are provided in Table I of this Appendix. Intracellular calcium buffering was modeled as previously described [74]. Changes made for the purpose of this study are summarized below.

Formulation of IRel (see Table II)

TABLE II.

Parameter Values of SR Ca2+ Release Model

| Value

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Dog | Guinea-Pig | Units | Definition |

| β0 | 4.75 | 4.75 | ms | minimal value for βτ |

| Kβ | 0.28 | mmol/L | Half-saturation constant of Δβτ,CaMK | |

| Δβ0 | 1 | mmol/L | maximal CaMKII-dependent change for βτ | |

| αRel | κβτ | κβτ | mmol/L/ms | amplitude coefficient of IRel,∞ |

| KRel,∞ | 1 | 1 | mmol/L | Half-saturation constant of IRel,∞ |

| hRel | 8 | 9 | Hill coefficient of IRel,∞ | |

| hβ | 10 | Hill coefficient of Δβτ,CaMK | ||

| κ | 0.1125 | 0.125 | μF/μA | amplitude coefficient ofαRel |

| KRel,τ | 0.0123 | 0.0123 | mmol/L | Half-saturation constant of IRel,τ |

| τtr | 120 | 120 | ms | time constant of Itr |

| γCai | 0.341 | 1 | ms | Ca2+ activity coefficient |

| Īup,CamK | 0.9 | mmol/L | maximal CaMKII-dependent change of Iup | |

The differential equation that describes IRel is of the form

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

IRel,∞ represents a steady state value of IRel and τIRel is its time constant, αRel is an amplitude coefficient, KRel,T is a half-saturation coefficient, βτ is a maximal value of τIRel.

We make τIRel in Eq(1) dependent on CaMKII to incorporate CaMKII-dependent facilitation into the model with a maximal change that produces a 100% facilitation of peak Δβτ,CamK:

| (4) |

In addition, we make τIRel in Eq(3) a function of [Ca2+]JSR to prevent an unphysiological draining of JSR. Sensitivity of the release flux Irel to luminal [Ca2+]JSR is modelled by Hill equation with a coefficient hRel [14, 57] and half-saturation constant KRel, ∞ [37].

Gating variables of ICa(L) (see Table III)

TABLE III.

Definitions of ICa(L) Model Parameters

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| d∞ | steady state fast voltage-dependent activation gate of ICa(L). |

| fca | fast Ca2+-dependent inactivation gate of ICa(L). |

| fca∞ | steady-state value of fca . |

| τfca | time constant of fca . |

Fast Ca2+-dependent inactivation (fCa gate) formulation:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where Δτ̄fca,CaMK is the maximal CaMKII-dependent change of τfca (time constant of fCa gate) and set to 5 ms, Km,CamK is a half-saturation coefficient, fCa,∞ is steady-state value of fCa. In addition, to reflect higher [Ca2+] in the subspace ([Ca2+]ss), activity coefficient γCai = 1 was replaced by γCass = 0.341 in the constant field equation for ĪCa(L). Steady state formulation of activation d gate was modified as follow

| (7) |

where V is the membrane voltage.

SR fluxes

CaMKII dependence of Iup was set to ΔĪup,CaMK = 0.9.

Model of SR Ca2+ Release and SR fluxes for LRd model

Numerical values for IRel, ∞ and τIRel are provided in Table II. Itr time constant τtr was set to 120 ms.

Steady state formulation of activation d gate of ICa(L) in LRd model was modified as follow, d∞ = 1/(1 + e− (V +10)/6.24) / (1 + e− (V −60)/0.024); where V is the membrane voltage.

Table IV provides documentation for the electrophysiological data used for the canine model validation. Table V contains CaMKII data used in simulations.

TABLE IV.

Canine ventricular myocyte electrophysiological data for model validation.

References

- 1.Adler D, Wong AY, Mahler Y. Model of mechanical alternans in the mammalian myocardium. J Theor Biol. 1985;117:563–577. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(85)80238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler D, Mahler Y. Modeling mechanical alternans in the beating heart: advantages of a systems-oriented approach. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1987;253:H690–H698. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.3.H690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson M. Calmodulin kinase and L-type calcium channels: a recipe for arrhythmias? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banyasz T, Fulop L, Magyar J, Szentandrassy N, Varro A, Nanasi PP. Endocardial versus epicardial differences in L-type calcium current in canine ventricular myocytes studied by action potential voltage clamp. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:66–75. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00853-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer KM, Schulman H. Regulation of signal transduction by protein targeting: The case for CaMKII. Biochem and Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:917–923. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bers DM. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beuckelmann DJ, Wier WG. Mechanism of release of calcium from sarcoplasmic reticulum of guinea-pig cardiac cells. J Physiol. 1988;405:233–255. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brochet DXP, Yang DM, Di Maio A, Lederer WJ, Franzini-Armstrong C, Cheng HP. Ca2+ blinks: Rapid nanoscopic store calcium signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chudin EJ, Goldhaber J, Garfinkel A, Weiss J, Kogan B. Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and the stability of ventricular tachycardia. Biophys J. 1999;77:2930–2941. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DelPrincipe F, Egger M, Niggli E. Calcium signaling in cardiac muscle: refractoriness revealed by coherent activation. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:323–329. doi: 10.1038/14013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSantiago J, Maier LS, Bers DM. Frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation in the heart depends on CaMKII, but not phospholamban. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:975–984. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Díaz ME, ONeill SC, Eisner DA. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuation is the key to cardiac alternans. Circ Res. 2004;94:650–656. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000119923.64774.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisner DA, Choi HS, Díaz ME, O'Neill SC, Trafford AW. Integrative analysis of calcium cycling in cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 2000;87:1087–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisner DA, Díaz ME, Li Y, ONeill SC, Trafford AW. Stability and instability of regulation of intracellular calcium. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:3–12. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.029231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faber GM, Rudy Y. Action potential and contractility changes in [Na+]i overloaded cardiac myocytes: A simulation study. Biophys J. 2000;78:2392–2404. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76783-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faber GM, Silva J, Livshitz L, Rudy Y. Kinetic properties of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel and its role in myocyte electrophysiology: A theoretical investigation. Biophys J. 2007;92:1522–1543. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabiato A. Simulated calcium current can both cause calcium loading in and trigger calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J Gen Physiol. 1985;85:291–320. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fill M, Copello JA. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox JJ, McHarg JL, Gilmour RF., Jr Ionic mechanism of electrical alternans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:516–530. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00612.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulop L, Banyasz T, Magyar J, Szentandrassy N, Varro A, Nanasi PP. Reopening of L-type calcium current in human ventricular myocytes during applied epicardial action potentials. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;180:39–47. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaertner TR, Kolodziej SJ, Wang D, Kobayashi R, Koomen JM, Stoops JK, Waxham MN. Comparative analyses of the three-dimensional structures and enzymatic properties of α, β, γ, δ Isoforms of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biolog Chem. 2004;279:12484–12494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua F, Gilmour RF., Jr Contribution of IKr to rate-dependent action potential dynamics in canine endocardium. Circ Res. 2004;94:810–819. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000121102.24277.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua F, Johns DC, Gilmour RF. Suppression of electrical alternans by overexpression of HERG in canine ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2342–H2352. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00793.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudmon A, Schulman H, Kim J, Maltez JM, Tsien RW, Pitt GS. CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J Cell Biology. 2005;171:537–547. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudmon A, Schulman H. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 2002;364:593–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hund T, Rudy Y. A Role for Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in cardiac disease and arrhythmia. In: Kass R, Clancy CE, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology: Basis and Treatment of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2004. pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hund TJ, Rudy Y. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation. 2004;110:3168–3174. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147231.69595.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hund TJ, Kucera JP, Otani NF, Rudy Y. Ionic charge conservation and long-term steady state in the Luo-Rudy dynamic cell model. Biophys J. 2001;81:3324–3331. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75965-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hüser J, Wang YG, Sheehan KA, Cifuentes F, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Functional coupling between glycolysis and excitation-contraction coupling underlies alternans in cat heart cells. J Physiol. 2000;524:795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kameyama M, Hirayama Y, Saitoh H, Maruyama M, Atarashi H, Takano T. Possible contribution of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump function to electrical and mechanical alternans. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36:125–135. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2003.50021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khoo MSC, Li J, Singh MV, Yang Y, Kannankeril P, Wu Y, Grueter CE, Guan X, Oddis CV, Zhang R, Mendes L, Ni G, Madu EC, Yang J, Bass M, Gomez RJ, Wadzinski BE, Olson EN, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Death, cardiac dysfunction, and arrhythmias are increased by calmodulin kinase II in calcineurin cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;114:1352–1359. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kihara Y, Morgan JP. Abnormal Cai2+ Handling is the Primary Cause of Mechanical Alternans - Study in Ferret Ventricular Muscles. Am Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1991;261:1746–H1755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knot FJ, Laher I, Sobie EA, Guatimosim S, Gomez-Viquez L, Hartmann H, Song L-S, Lederer WJ, Graier WF, Malli R, Frieden M, Petersen OH. Twenty years of calcium imaging: cell physiology to dye for. Molecular intervention. 2005;1:112–127. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koller ML, Maier SKG, Gelzer AR, Bauer WR, Meesmann M, Gilmour RF. Altered dynamics of action potential restitution and alternans in humans with structural heart disease. Circulation. 2005;112:1542–1548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koller ML, Riccio ML, Gilmour RF., Jr Dynamic restitution of action potential duration during electrical alternans and ventricular fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:1635–1642. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubalova Z, Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Nishijima Y, Gyorke I, Terentyeva R, da Cunha DNQ, Sridhar A, Feldman DS, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA, Gyorke S. Abnormal intrastore calcium signaling in chronic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504298102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lab MJ, Lee JA. Changes in intracellular calcium during mechanical alternans in isolated ferret ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 1990;66:585–595. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Marionneau C, Zhang R, Shah V, Hell JW, Nerbonne JM, Anderson ME. Calmodulin Kinase II inhibition shortens action potential duration by upregulation of K+ currents. Circ Res. 2006;99:1092–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249369.71709.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linz KW, Meyer R. Profile and kinetics of L-type calcium current during the cardiac ventricular action potential compared in guinea-pigs, rats and rabbits. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s004249900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livshitz LM, Rudy Y. Dysfunction of calcium subsystem including CaMKII signaling pathway cause electromechanical alternans in guinea pig and dog myocyte models. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:S65. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 42.López-López JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium channel currents in cardiac cells. Science. 1995;268:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7754383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo CH, Rudy Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circ Res. 1994;74:1071–96. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo CH, Rudy Y. A model of the ventricular cardiac action-potential - depolarization, repolarization, and their interaction. Circ Res. 1991;68:1501–1526. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.6.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maier LS, Barckhausen P, Weisser J, Aleksic I, Baryalei M, Pieske B. Ca2+ handling in isolated human atrial myocardium. Am Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:952–958. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy CF, Horner SM, Dick DJ, Coen B, Lab MJ. Electrical alternans and the onset of rate-induced pulsus alternans during acute regional ischaemia in the anaesthetised pig heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:138–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Narayan SM. T-wave alternans and the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orchard CH, McCall E, Kirby MS, Boyett MR. Mechanical alternans during acidosis in ferret heart muscle. Circ Res. 1991;68:69–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanism linking T-wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 1999;99:1385–1394. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Picht E, DeSantiago J, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Cardiac alternans do not rely on diastolic sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuations. Circ Res. 2006;99:740–48. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244002.88813.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pruvot EJ, Katra RP, Rosenbaum DS, Laurita KR. Role of calcium cycling versus restitution in the mechanism of repolarization alternans. Circ Res. 2004;94:1083–1090. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125629.72053.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pu J, Boyden PA. Alterations of Na+ currents in myocytes from epicardial border zone of the infarct heart: A possible ionic mechanism for reduced excitability and postrepolarization refractoriness. Circ Res. 1997;81:110–119. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenbaum DS, Jackson LE, Smith JM, Garan H, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical Alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J of Med. 1994;330:235–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudy Y. The Cardiac Ventricular Action Potential. In: Page E, Fozzard HA, Solaro RJ, editors. Handbook of Physiology: The Heart. Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato D, Shiferaw Y, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z, Karma A. Spatially discordant alternans in cardiac tissue: Role of calcium cycling. Circ Res. 2006;99:520–527. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000240542.03986.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shampine LF, Reichelt MW, Kierzenka JA. Solving index-I DAEs in MATLAB and Simulink. SIAM Rev. 1999;41:538–552. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys J. 2000;78:334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shiferaw Y, Watanabe MA, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Karma A. Model of intracellular calcium cycling in ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2003;85:3666–3686. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74784-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shiferaw Y, Sato D, Karma A. Coupled dynamics of voltage and calcium in paced cardiac cells. Phys Rev E. 2005;71:021903. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.021903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sipido KR, Volders PG, de Groot SH, Verdonck F, Van de Werf F, Wellens HJJ, Vos MA. Enhanced Ca2+ release and Na+/Ca2+ exchange activity in hypertrophied canine ventricular myocytes: potential link between contractile adaptation and arrhythmogenesis. Circulation. 2000;102:2137–2144. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith SD. Modeling the Stochastic Gating of Ion Channels. In: Fall CP, Marland ES, Wagner JM, Tyson JJ, editors. Computational Cell Biology. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. pp. 285–319. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sneyd J, Falcke M. Models of the Inositol triposphate receptor. Prog Bioph Mol Biol. 2005;89:207–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song L-S, Pi YQ, Kim S-J, Yatani A, Guatimosim S, Kudej RK, Zhang Q, Cheng H, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Vatner DE, Lederer WJ, Vatner SF. Paradoxical cellular Ca2+ signaling in severe but compensated canine left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2005;97:457–464. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000179722.79295.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stern MD, Cheng H. Putting out the fire: what terminates calcium-induced calcium release in cardiac muscle? Cell Calcium. 2004;35:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szentesi P, Pignier C, Egger M, Kranias EG, Niggli E. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ refilling controls recovery from Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release refractoriness in heart muscle. Circ Res. 2004;95:807–813. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146029.80463.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ten Tusscher KHWJ, Panfilov AV. Alternans and spiral breakup in a human ventricular tissue model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:1088–1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00109.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Valdivia HH, Escobar AL, Gyorke S. Luminal Ca2+ controls termination and refractory behavior of CICR in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:414–420. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032490.04207.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wan XP, Laurita KR, Pruvot EJ, Rosenbaum DS. Molecular correlates of repolarization alternans in cardiac myocytes. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wehrens XHT, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res. 2004;94:61–70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiss JN, Karma A, Shiferaw Y, Chen P-S, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. From pulsus to pulseless: the saga of cardiac alternans. Circ Res. 2006;98:1244–1353. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224540.97431.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilson LD, Wan X, Rosenbaum DS. Cellular Alternans. A mechanism linking calcium cycling proteins to cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1080:216–234. doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu XD, Yang DM, Ding JH, Wang W, Chu PH, Dalton ND, Wang HY, Bermingham JR, Ye Z, Liu F, Rosenfeld MG, Manley JL, Ross J, Chen J, Xiao RP, Cheng HP, Fu XD. ASF/SF2-Regulated CaMKIIδ alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell. 2005;120:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zaitsev AV, Guha PK, Sarmast F, Kolli A, Berenfeld O, Pertsov AM, de Groot JR, Coronel R, Jalife J. Wavebreak formation during ventricular fibrillation in the isolated, regionally ischemic pig heart. Circ Res. 2003;92:546–553. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000061917.23107.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeng J, Laurita KR, Rosenbaum DS, Rudy Y. Two components of the delayed rectifier K+ current in ventricular myocytes of the guinea pig type. Circ Res. 1995;77:140–152. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang R, Khoo MSC, Wu YJ, Yang YB, Grueter CE, Ni GM, Price EE, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]