Abstract

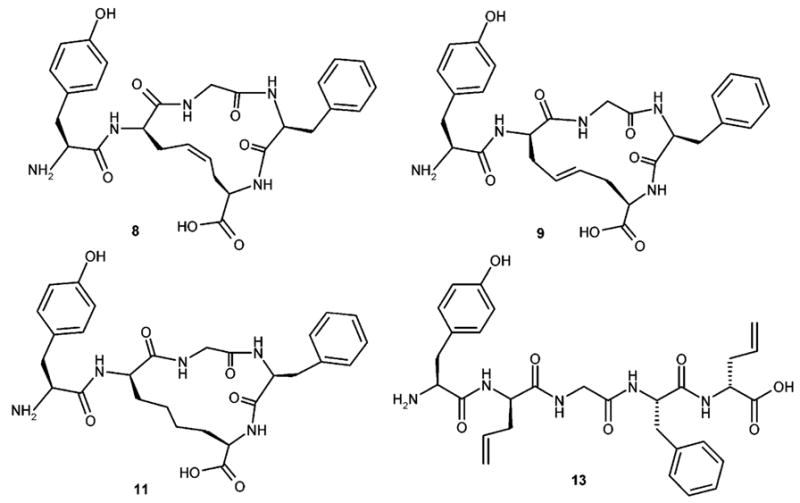

Ring-closing metathesis has emerged as a powerful tool in organic synthesis for generating cyclic structures via C–C double bond formation. Recently, it has been successfully used in peptide chemistry for obtaining cyclic molecules bridged through an olefin unit in place of the usual disulfide bond. Here, we describe this approach for obtaining cyclic olefin bridged analogues of H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-Cys]-OH. The synthesis of the new ligands was performed using the second generation Grubbs’ catalyst. The resulting cis-8 (cDADAE) and trans-9 (tDADAE) were fully characterized and tested at δ, μ, and κ opioid receptors. Also the linear precursor 13 (lDADAE) and the hydrogenated derivative 11 (rDADAE) also were tested. All the cyclic products containing a olefinic bond are slightly selective but highly active and potent for the δ and μ opioid receptors. Activity toward the κ opioid receptors was absent or very low.

Introduction

Cysteine-based disulfide bridges are a common feature in proteins and natural peptides where they play essential roles in a variety of structural and biochemical functions. Among the different functions, the limitation of the conformational flexibility with stabilization of secondary structures and the consequent lowering of the unfavorable entropy loss upon binding is extremely important.1,2 Disulfide-bridge cyclization is also one of the most common tools in the design of synthetic models starting from their linear counterparts.3 The 14-membered cyclic enkephalin analogues H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH4 and the related [D-Pen2,D-Pen5] model (DPDPEa)5 are the most relevant cyclic opioid peptides. The side-chain thiol groups at the 2- and 5-position residues of these molecules are oxidized to form a disulfide bridge that imposes a global constraint to the structure. In particular, the cystine bridge containing analogue shows an exceptionally good activity on δ and μ receptors, whereas due to the presence of the gem-dimethyl groups of the penicillamine residues, DPDPE is highly selective toward δ receptors and is used in the opioid binding assays as the radio-labeled δ receptor full agonist.5 Furthermore, while the cystine analogues possessing a C-terminal carboxamide function are essentially nonselective, the corresponding free acids show a certain preference for δ over μ receptors.4a

Although widely used with success, the disulfide-based cyclization approach still maintains some limitations. Due to its redox properties, the S–S bond is exposed to the enzymatic attack by reductases and can be cleaved by sulfhydryl groups or other soft nucleophiles. Moreover, the geometry of the bond is limited by the stereoelectronic effects exerted by the sulfur atoms’ lone pairs, which fix the dihedral angle C–S–S–C at about ±90°.6

Because the stabilization of well-ordered secondary structures is a major issue in peptide chemistry, several cyclization strategies, not based on the disulfide bridge formation, have been applied to obtain more stable and versatile products.7 Very attractive in this context appears the replacement of the critical S–S junction with a noncleavable C–C bond. An early application performed on a bioactive peptide, reported by Keller and Rudinger8 concerns the synthesis of the dicarba-analogue of oxytocin: it is based on the incorporation of a 1,6-α, α′-diamino suberic acid residue in place of the native cystine fragment. More recently, Stymiest et al.9 reported that the replacement of cysteines with allylglycine residues, followed by ruthenium-catalyzed ring-closing olefin metathesis (RCM), gives an easy access to cis and trans olefinic analogs of oxytocin as well as to the previously reported8 corresponding bis-methylene derivative.

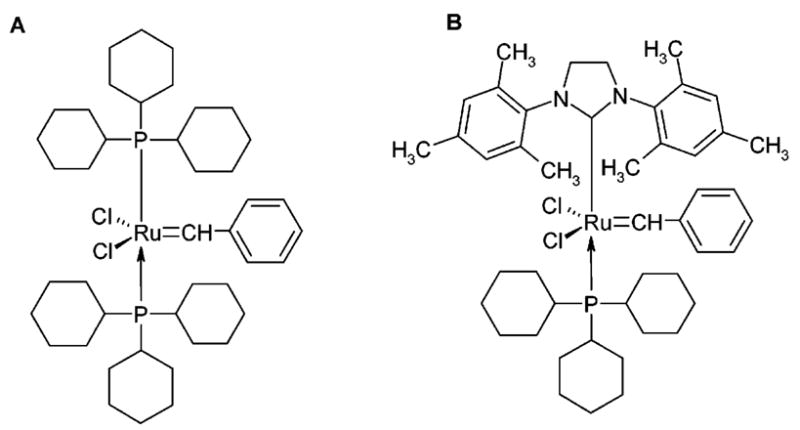

RCM is an emerging powerful tool in the peptide chemistry for generating cyclic structures via C–C double bond formation. The reaction is catalyzed by ruthenium complexes, first- or second-generation Grubbs catalysts (Figure 1), and can directly be used for the synthesis of a variety of peptide diene systems.10 Thus, by adopting the RCM methodology, a “third” generation of cyclic opioid analogues, characterized by metabolic stability and rigid conformation, becomes available. However, although many studies are dedicated to the application of the RCM methodology in peptide chemistry11 and the perspective of a fine control of the conformations, based on the incorporation of cis or trans olefin junctions into the cyclic backbone is extremely important and promising, only the synthesis and properties of carboxamides of the dicarba-analogues of the cyclic 14-membered disulfide enkephalin analogues12 are reported in a symposium record by Schiller et al.

Figure 1.

First (A) and second (B) generation Grubbs’ catalysts.

On the basis of the above observations, here we report the synthetic protocols and in vitro biological tests of cystine-containing enkephalin dicarba analogues 8, 9, 11, and 13 (Figure 2). All these derivatives possess a C-terminal free carboxyl group: this feature, in analogy with the behavior exhibited by the corresponding disulfide analogues, should improve the δ/μ selectivity as compared with the previously reported C-terminal carboxamide derivatives.12

Figure 2.

Structures of cDADAE (8), tDADAE (9), rDADAE (11), and lDADAE (13).

Results and Discussion

The ability of the synthesized enkephalin analogues to inhibit electrically evoked contractions of the myenteric plexus of the longitudinal muscle of the guinea pig ileum (GPI) and the mouse vas deferens (MVD) proves to be very high: IC50 values for 8, 9, 11, and 13 are 0.59, 0.76, 3.4, and 5.7 nM in the predominant DOR containing MVD and 5.3, 5.2, 59, and 34 nM in the MOR-rich GPI (Table 1). Tests performed by using nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI), an antagonist of κ Kappa opioid receptors (10nM nor-BNI), show little effect on κ receptor activity (data not reported).

Table 1.

Binding Affinity and In Vitro Activity for Compounds 8, 9, 11, and 13 and Reference Compounds

| bioassay IC50a(nM)

|

binding Kia,b (nM)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpds | MVD | GPI/LMMP | hDOR | hMOR | KOR |

| cDADAE (8) | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 5.3 ± 0.21 | 0.43 ± 0.16 | 1.35 ± 0.45 | 576 ± 23 |

| tDADAE (9) | 0.76 ± 0.070 | 5.2 ± 0.61 | 0.57 ± 0.21 | 1.30 ± 1.2 | 74.8 ± 5.1 |

| rDADAE (11) | 3.4 ± 0.60 | 59 ± 24 | 7.9 ± 0.61 | 56.9 ± 3.5 | 3960 ± 210 |

| lDADAE (13) | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 34 ± 11 | 8.1 ± 0.22 | 64.5 ± 4.1 | 3870 ± 185 |

| H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-Xc | 0.12 | 1.48 | 0.822 | 0.550 | 44.9 |

| DPDPEd | 4.1 ± 0.46 | 7300 ± 1700 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 609 ± 70 | |

Displacement of [3H]DAMGO (μ -selective) and [3H]DPDPE (δ-selective) from rat brain membrane binding sites; displacement of [3H]U69593 (κ-selective) from guinea pig brain membrane binding sites.

±S.E.M.

MVD and GPI data refers to H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-Xc (X = OH) according to ref 4a and hDor, hMor, and Kor data refers to H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-Xc (X = NH2) according to ref 12a.

Data according to ref 19b.

To test the affinity of 8, 9, 11, and 13 for opioid receptors, binding tests with radiolabeled standards (3H-DPDPE for hDOR, 3H-DAMGO for MOR, and 3H-U69593 for KOR) were performed19 (see Table 1). Literature data for DPDPE and H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH are also reported for comparison.

The results show that compounds 8, 9, 11, and 13 have a different binding affinity for δ, μ, and κ receptors: Ki values for 8 and 9 are 1.35 and 1.30 nM, respectively, for the MOR and 0.43 and 0.57 nM for the DOR; Ki values for 11 and 13 are 56.9 and 64.5 nM, respectively, for the MOR and 7.9 and 8.1 nM, respectively, for the DOR. All compounds show very small affinity for KOR (Table 1). Therefore, the binding affinity of 8 and 9 for the μ receptor is higher than that of 11 and 13 and much higher than that of DPDPE, which is similar to H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-X (X = NH2).

The above-reported in vitro bioassays show that both 8 and 9 are highly potent agonists at μ and δ receptors, but only slightly selective (δ/μ ratio is in the range of about 7–9): they are 10 times more potent than DPDPE for the δ receptors and more than 1000 times more potent for μ receptors. These results suggest that the novel H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH analogues show high potency but a low selectivity as previously found for the related peptides family of H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-X (X = OH or NH2). However, the two analogues 8 and 9, characterized by a different geometrical isomerism, do not show any significant difference in their biological profile.

It is well-established that the spatial orientation of the Tyr1 and Phe4 aromatic moieties19 is a key conformational feature for the selectivity of the ligands of opioid receptors. The results reported here suggest that the olefin bridge, present in the H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH dicarba analogues, do not significantly affect the orientation of the aromatic moieties when compared to the disulfide bond. The lack of selectivity obtained clearly confirms that the selectivity of DPDPE is principally attributable to the gem-dimethyl moiety of the penicillamine residues, which generates an enhancement of the affinity for the δ receptor. It is important to notice that the different configuration of the double bond in the two new ligands does not influence their biological profile, but the increased structural flexibility of the ring scaffold obtained by the reduction of the double bond of compounds 8 and 9 leads to a decreased binding affinity and biological activity for both the DOR and the MOR. Therefore, the higher activity of cyclic products 8 and 9 compared to that of linear compound 13 can be attributed to their rather rigid conformations.

A final consideration concerns the results of the [35S]GTP-γ-S binding. EC50 values exhibited by 8 and 9 for GPTγ[S35] binding to δ and μ receptor. The results (Table 2) show that the ligands have a high ability to activate the transduction of the μ and δ receptors. Also the Emax% value expresses the high efficacy of all the tested compounds.

Table 2.

GTP Binding Assay

|

[35S]GTPγS bindinga |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) hDOR | Emax(%)b | EC50 (nM) hMOR | Emax%b | |

| cDADAE (8) | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 121 | 2.35 ± 0.20 | 65 |

| tDADAE (9) | 0.88 ± 0.28 | 128 | 2.65 ± 0.45 | 70 |

Reference compound: [35S]GTP-γ-S.

Net total bound/basal binding × 100 ± SEM for compounds 8 and 9.

In conclusion, the reported modification of the disulfide bridge in H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-X (X = OH or NH2) leads to analogue products that show a significant improvement of both chemical and biological stability with respect to their disulfide analogues. This property is accompanied by a slightly enhanced selectivity toward the δ opioid receptor and by the same efficacy and potency of D-cysteine-containing peptides. The choice to synthesize derivatives with a C-terminal free carboxylic function, instead of the C-terminal amide groups aimed at verifying if this feature could improve the δ versus μ selectivity, as observed in the case of the disulfide counterparts. The present results show that the δ/μ ratio is not significantly altered by the carboxy terminus: this observed lack of selectivity may be useful in clinical trials to evaluate the effects of the synergistic stimulation of both δ and μ opioid receptors.20 Therefore, the presented results may be considered a further step in understanding the opioid system and the design of more stable, potent, and efficacious drugs.

Experimental Section

General Information

All solvents, reagents, and starting materials were obtained from commercial sources unless otherwise indicated. All reactions were performed under N2 unless otherwise noted. Intermediate products 2, 3, 4, and 5 were purified by silica gel chromatography. The fully protected products 6, 7, and 10 were purified by RP-HPLC using a semipreparative Vydac (C18-bonded, 300 Å) column and an isocratic elution at a flow rate of 10 mL/min monitored at 254 and 270 nm. The mobile phase used was 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous TFA over 40 min. Approximately 20 mg of crude peptide was injected each time, and the fractions containing the purified peptide were collected and lyophylized to dryness. In the case of products 6 and 7, this method was unable to separate the two geometric isomers that were collected, and their mixture was purified by HPLC. Products 8, 9, 11, and 13 used for the biological assay were further purified by RP-HPLC using a semipreparative Vydac (C18-bonded, 300 Å) column and a gradient elution at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. The gradient used was 10–90% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous TFA over 40 min. Approximately 10 mg of crude peptide was injected each time, and the fractions containing the purified peptide were collected and lyophilised to dryness. The purity of the final products, determined by NMR analysis and by analytical RP-HPLC (C18-bonded 4.6 × 150 mm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min on a Waters Binary pump 1525 using a isocratic elution of 20% CH3CN/H2O 0.1% TFA, monitored with a Waters 2996 Photodiode Array Detector, was found to be >95%.

Peptide structures were determined by NMR spectroscopy and confirmed by high resolution-mass spectra (HR-MS). For the final products, 8 (cDADAE), 9 (tDADAE), 11 (rDADAE), and 13 (lDADAE), elemental analyses (within ± 0.4% of the theoretical values) were performed (for detailed experimental and analytical data, refer to the Supporting Information).

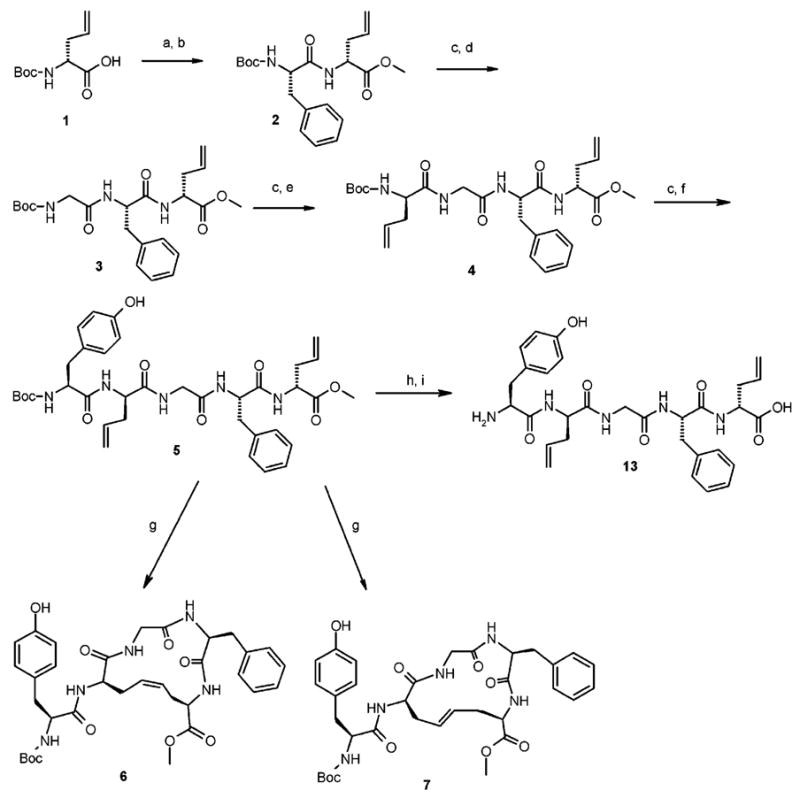

Chemistry

The linear intermediate pentapeptide 5 (lDADAE; Scheme 1) was synthesized in the solution phase by using the Nα-Boc strategy. Amino acid couplings were performed by using either EDC or BOP-Cl/HOBT•H2O/NMM in DMF,13 both resulting in high yields. N-Terminus Nα-Boc deprotection of compound 1 was accomplished with SOCl2/MeOH, thus realizing contemporary C-terminal esterification; in all the other cases, Boc cleavage was performed by using excess of TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:2) at rt for 1 h. All the intermediate products, unless otherwise specified, were purified by RP-HPLC and then characterized by Fab+ MS and NMR spectroscopy. All new final compounds gave correct elemental analysis. For the RCM reaction, the second generation of Grubbs’ catalyst (Figure 1B), which is rated to be more stable and reactive than the first generation (Figure 1A), was used.14 The ring closure was accomplished by adding a catalytic amount of the catalyst to a 10 mM solution of 5 in CHCl3 at rt until the reaction was complete. The cyclization progress was monitored by TLC (EtOAc). The two isomeric peptides cis-8 (cDADAE) and trans-9 (tDADAE; Figure 2) were obtained in about 1:3 ratio, respectively (Scheme 1). While the two products were clearly distinguishable by TLC (EtOAc), they showed very close RP-HPLC retention times in the condition of the analysis. The cis and trans isomers where then separated by PLC, charging a maximum of 10 mg on each 20 × 20 cm/0.25 mm silica gel plate.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Fully Protected H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH Analogues 5, 6, and 7 and Linear Deprotected Product 13a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) SOCl2/MeOH 10 min at 0 °C, then 6 h at rt; (b) Boc-Phe-OH/EDC/HOBT•H2O/DMF/NMM, 16 h at rt; (c) TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:2) 1 h, rt; (d) Boc-Gly-OH/EDC/HOBT•H2O/NMM/DMF, 16 h at rt; (e) Boc-D-Allyl-Gly-OH/EDC/HOBT•H2O/NMM/DMF, 16 h at rt; (f) Boc-Tyr-OH/EDC/HOBT•H2O/NMM/DMF, 16 h at rt; (g) Grubbs’ catalyst second generation (20%)/CH2Cl2 at rt; (h) TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:2) 1 h at rt; (i) NaOH 1 N 6 equiv/MeOH, 4 h at rt.

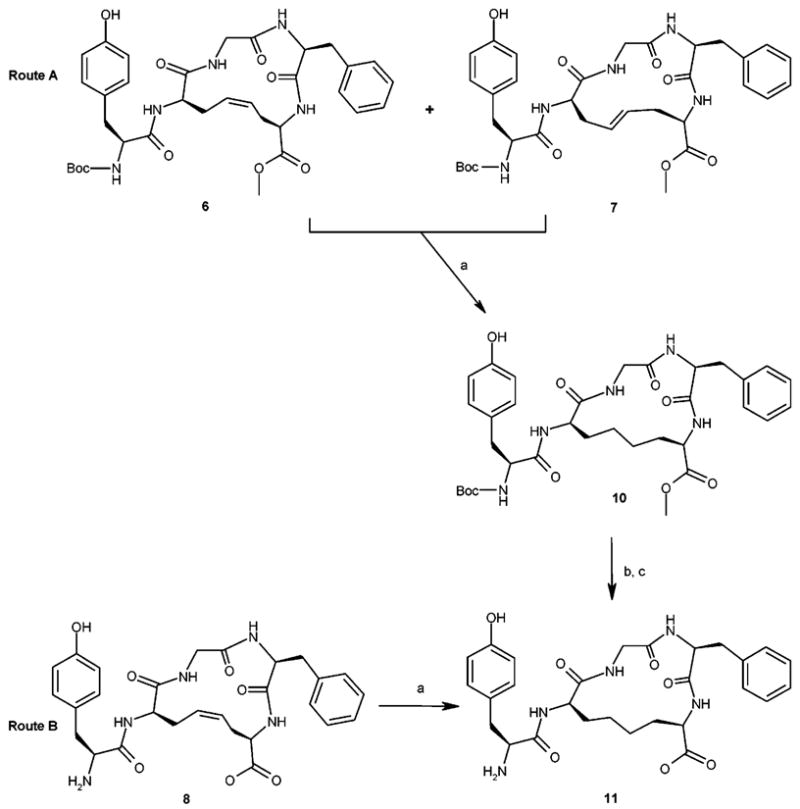

To synthesize the analogue 11 (rDADAE), containing a –CH2–CH2– junction, a portion of the RP-HPLC purified mixture, containing both the geometrical isomers 6 and 7 (1:3 ratio), was catalytically hydrogenated at atmospheric pressure in MeOH (Scheme 2; route A). The reaction was monitored every 6 h by TLC. After about 48 h, all the starting material disappeared, giving rise to a single spot. The catalyst was filtered and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum. After purification by silica gel chromatography, the fully protected methyl ester 10 was obtained in almost quantitative yield. Hydrolysis followed by Boc deprotection under standard conditions and purification by RP-HPLC gave the desired free acid 11. This compound was also obtained in one step starting from the cis analogue 8 (Scheme 2; route B) by applying the same catalytic hydrogenation conditions described before.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the Bismethylene Analogue 11: Route A, Catalytic Hydrogenation of (6 + 7) Mixture; Route B, Catalytic Hydrogenation of cis-8 (cDADAE)a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) H2/Pt/C 10%/MeOH, 48 h, rt; (b) NaOH (1 N, 3 equiv), 6 h, rt; (c) TFA/CH2Cl2 1:2, 1 h, rt.

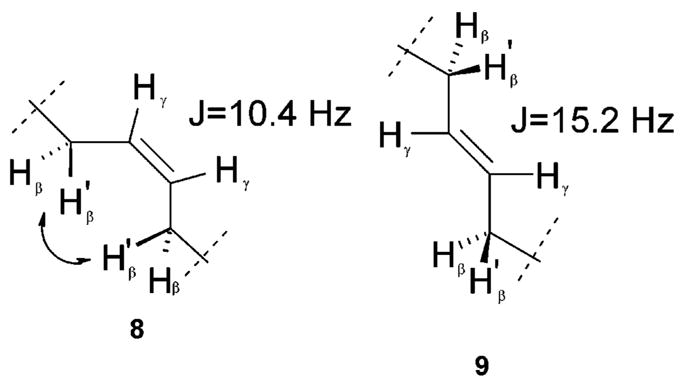

The configuration of the double bond of compounds 8 and 9 was accurately established by the NMR analysis.15 The value of the J coupling constants between γ-protons of D-All-Gly2 and D-All-Gly5 (10.4 Hz for 8 and 15.2 Hz for 9) corresponds to a cis and a trans configuration of the double bond in 8 and 9, respectively. This assignment is confirmed by the presence of a correlation peak between H-β of D-All-Gly5 and H-β of D-All-Gly2 in the ROESY map of 8. In the case of 9, β-protons of D-All-Gly5 and D-All-Gly2 do not give any observable NOE correlation, confirming the trans configuration of the double bond (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Double bond geometry in 8 (cis conformer) and 9 (trans conformer).

Biological Testing

In vitro biological assays were performed on 8, 9, 11, and 13 as TFA salts.

GPI and MVD In Vitro Bioassays

The in vitro tissue bioassays were performed as described previously.16 Electrically induced smooth muscle contractions of mouse vas deferens and guinea pig ileum longitudinal muscle-myenteric plexus were used as bioassays. Tissue came from male ICR mice weighing 25–30 g and from male Hartley guinea pigs weighing 150–400 g. The tissues were tied to gold chains with suture silk, suspended in 20 mL baths containing 37 °C oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Krebs bicarbonate solution (magnesium-free for MVD), and allowed to equilibrate for 15 min. The tissues were then stretched to optimal length previously determined to be 1 g tension (0.5 g for MVD) and allowed to equilibrate for 15 min. The tissues were stimulated transmurally between platinum plate electrodes at 0.1 Hz for 0.4 ms pulses (2.0 ms pulses for MVD) and supramaximal voltage. Grugs were added to the baths in 20–60 μL volumes. The agonists remained in contact with the tissue for 3 min and the baths were then rinsed several times with fresh Krebs solution. Tissues were given 8 min to re-equilibrate and regain predrug contraction height. IC50 values represent the mean of not less than four tissues. IC50 estimates and relative potency estimates were determined by fitting the mean data to the Hill equation by using a computerized nonlinear least-squares method. All biological data are summarized in Table 1.

Radioligand-Labeled Binding Assays

Receptor binding affinities to the δ, μ, and κ opioid receptors were performed using cell membrane preparations from transfected cells that stably express the respective receptor type and were evaluated as previously described.17 The ligands used were [3H]DPDPE, [3H]DAMGO, and [3H]U69593 for δ, μ, and κ opioid receptors, respectively.

GTP Binding and Emax% (Agonist Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding).18

We used [35S]GTP-γ-S binding to examine opioid agonist efficacy for functional characterization of the ligands at the δ and μ opioid receptors, which are members of the seven transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor super family. Agonist efficacy can be determined at the level of receptor G-protein interaction by measuring agonist-stimulated binding with a non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue. The ability of μ and δ opioid agonists to activate G-proteins has been demonstrated by studying the binding of the GTP analogue guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate ([35S]GTP-γ-S). The opioid receptor mediated assay was performed as previously described.19 Cells expressing hDOR for δ receptor (or rMOR for μ receptor) were incubated with increasing concentrations of the test compounds in the presence of 0.1 nM [35S]GTP-γ-S (1000–1500 Ci/mmol, MEN, Boston, MA) in assay buffer (total volume of 1 mL, duplicate samples) as a measure of agonist-mediated G-protein activation. After incubation (90 min, 30 °C), the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters, followed by four washes with ice-cold 15 mM Tris/120 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Filters were pretreated with assay buffer prior to filtration to reduce nonspecific binding. Bound reactivity was measured by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry after an overnight extraction with EcoLite (ICN, Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) scintillation cocktail. The data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism Software (San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures and representative scheme of the synthesis of compounds 1–13, elemental analyses for products 6–11 and 13, HPLC and HR-MS for products 5–11 and 13, NMR analyses of products 1–13, and Roesy spectra of 8 and 9. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Gino Lucente, Prof. Mario Paglialunga Paradisi, Prof. Annalaura Segre, and Dr. Yeon Sun Lee for their helpful support and discussions. This study was supported in part by the U.S. Public Health Service, Grant DA06284.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: D-Allylgly, D-Allylglycine; cDADAE, cis-c[2-D-allylg-lycine, 5-D-allylglycine]enkephalin; 3H-DAMGO, [3H]-[D-Ala(2),N-Me-Phe-(4),Glyol(5)]enkephalin; 3H-DPDPE, [3H]-c[2-D-penicillamine,5-D-penicillamine]enkephalin; 3H-U69593, [3H]-(+)-5α,7α,8β)-N-methyl-N-[7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro[4,5]dec-8-yl]-benzeneacetamide; DCM, dichloromethane; DMF, N,N-dimethyl formamide; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; EDC,1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide; GPI/LMMP, guinea pig ileum/longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus (μ opioid receptors); GTP, guanosine triphosphate; hMOR, human μ opioid receptor; HOBT, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole; KOR, κ opioid receptor; lDADAE, [2-D-allylglycine, 5-D-allylglycine]-enkephalin; MVD, mouse vas deferens (δ opioid receptors); rDADAE, reduced bond-c[2-D-allylglycine, 5-D-allylglycine]enkephalin; rDOR, rat δ opioid receptor; tDADAE, trans-c[2-D-allylglycine, 5-D-allylglycine]enkephalin; TEA, triethylamine; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid.

References

- 1.Li P, Roller PP. Cyclization strategies in peptide derived drug design. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:325–341. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hruby VJ. Conformational restrictions of biologically active peptides via amino acid side chain groups. Life Sci. 1982;31:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creighton TE. Proteins: Structures and Molecular Properties. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Schiller PH, DiMaio J, Nguyen TMD. Activity profiles of conformationally restricted opioid peptide analogs. Proc FEBS Congr 16th. 1985;B:457–462. [Google Scholar]; (b) Froimowitz M, Hruby VJ. Conformational analysis of enkephalin analogs containing a disulfide bond. Models for delta- and mu-receptor opioid agonists. Int J Pept Prot Res. 1989;34:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1989.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hruby VJ, Gehrig CA. Recent developments in the design of receptor specific opioid peptides. Med Res Rev. 1989;9:343–401. doi: 10.1002/med.2610090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mosherg HI, Hurst R, Hruby VJ, Galligan JJ, Burks TF, Gee K, Yamanura HI. [D-Pen2,L-Cys5]Enkephalinamide and [D-Pen2, D-Cys5]enkephalinamide, conformationally constrained cycle enkephalinamide analogues with delta receptor specificity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Mosberg HI, Hurst R, Hruby VJ, Cree K, Yamamura HI, Galligan JJ, Burks TF. Bis Penicillamine enkephalins possess highly improved specificity toward δ opioid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5871–5871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.5871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collins N, Flippen-Anderson J, Haaseth RC, Deschamps JR, George C, Kover K, Hruby VJ. Conformational determinants of agonist versus antagonist properties of [D-Pen2, D-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE) analogs at opioid receptors. Comparison of X-ray crystallographic structure, solution 1H NMR data, and molecular dynamic simulations of [L-Ala3]-DPDPE and [D-Ala3]DPDPE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2143–2152. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bartosz-Bechowski H, Davis P, Zalewska T, Slaninova J, Porreca F, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ. Cyclic enkephalin analogs with exceptional potency at peripheral δ opioid receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:146–150. doi: 10.1021/jm00027a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hruby VJ, Kao LF, Pettitt BM, Karplus M. The conformational properties of the delta opioid peptide [D-Pen2, D-Pen5]enkephalin in acqueous solution determined by NMR and energy minimization calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3351–3359. [Google Scholar]; (e) Akiyama K, Gee KW, Mosberg HI, Hruby VJ, Yamamura HI. Characterization of [3H] [D-Pen2-D-Pen5]enkephalin binding to δ opiate receptors in the rat brain and neuroblastomaglioma hybrid cell line (NG 108–15) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2543–2547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Voyer N, Lamothe J. The use of peptidic frameworks for the construction of molecular receptors and devices. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:9241–9284. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kaul R, Balaram P. Stereochemical control of peptide folding. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:105–117. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Andrews MJI, Tabor AB. Forming stable helical peptides using natural and artificial amino acids. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:11711–11743. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hruby VJ, Al-Obeidi F, Kasmierski WM. Emerging approaches in the molecular design of receptor selective peptide ligands: conformational topographical and dynamic considerations. Biochem J. 1990;268:249–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2680249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) DiMaio J, Schiller PW. A cyclic enkephalin analog with high in vitro opiate activity. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7162–7166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DiMaio J, Nguyen TMD, Lemieux C, Schiller PW. Synthesis and pharmacological characterization in vitro of cyclic enkephalin analogs: Effect of conformational constraints on opiate receptor selectivity. J Med Chem. 1982;25:1432–1438. doi: 10.1021/jm00354a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schiller PW, Nguyen TMD, Miller J. Synthesis of side-chain to side-chain cyclized peptide analogs on solid supports. Int J Pept Prot Res. 1985;25:171–177. [Google Scholar]; (d) Siemion IZ, Szewczuk Z, Herman ZS, Stachura Z. To the problem of biologically active conformation of enkephalin. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;34:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02354848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller O, Rudinger J. Synthesis of (1,6-alpha,alpha′-diaminosuberic acid)oxytocin (“dicarba-oxytocin”) Helv Chim Acta. 1974;57:1253–1259. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19740570502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stymiest JL, Mitchell BF, Wong S, Vederas JC. Synthesis of biologically active dicarba analogues of the peptide hormone oxytocin using ring-closing metathesis. Org Lett. 2003;5:47–49. doi: 10.1021/ol027160v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Grubbs RH, Chang S. Recent advances in olefin metathesis and its application in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4413–4450. [Google Scholar]; (b) Armstrong SK. Ring closing diene metathesis in organic synthesis. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 1998:371–388. [Google Scholar]; (c) Blackwell HE, Grubbs RH. Highly efficient synthesis of covalently cross-linked peptide helices by ring closing metathesis. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:3281–3284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981217)37:23<3281::AID-ANIE3281>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Celanire S, Descamps-Francois C, Lesur B, Guillaumet G, Joseph B. Synthesis of 14-membered ring jaspamide derivatives. Lett Org Chem. 2005;2:528–531. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wels B, Kruijtzer JAW, Garner K, Nijenhuis WAJ, Gispen WH, Adan RAH, Liskamp RMJ. Synthesis of a novel potent cyclic peptide MC4-ligand by ring-closing metathesis. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:4221–4227. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stymiest JL, Mitchell BF, Wong S, Vederas JC. Synthesis of oxytocin analogues with replacement of sulfur by carbon gives potent antagonists with increased stability. J Org Chem. 2003;70:7799–7809. doi: 10.1021/jo050539l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Schmidt B, Kuhn C, Ehlert DK, Lindeberg G, Lindman S, Karlen A, Hallberg A. A frame shifted disulfide bridged analogue of angiotensin II. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:985–990. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00517-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kaptein B, Broxterman QB, Schoemaker HE, Rutjes FPJT, Veerman JJN, Kamphuis J, Peggion C, Formaggio F, Toniolo C. Enantiopure Cα-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis and application to turn-forming peptides. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:6567–6577. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Schiller PW, Weltrowska G, Berezowska I, Lemieux C, Chung NN, Wilkes BC. Synthesis and in vitro opioid activity profiles of novel cyclic enkephalin analogs. In Understanding Biology Using Peptides. In: Blondelle SE, editor. Proceedings of the 19th American Peptide Symposium; June 18–23; San Diego CA. La Costa, CA: American Peptide Society; 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schiller PW. Opioid peptide analog design: from cyclic enkephalins to orally active analgesics. Biopolymers. 2005;80:492. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Han So-Y, Kim YA. Recent development of peptide coupling reagents in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:2447. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim Y-A, Han So-Y. Comparative study of cyanuric fluoride and Bop-Cl as carboxyl activators in peptide coupling reactions. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2000;21:943–946. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Trnka TM, Grubbs RH. The development of L2X2Ru:CHR olefin metathesis catalysts: An organometallic success story. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:18–29. doi: 10.1021/ar000114f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chatterjee AK, Grubbs RH. Synthesis of trisubstituted alkenes via olefin cross-metathesis. Org Lett. 1999;11:1751–1753. doi: 10.1021/ol991023p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Synthesis and activity of a new generation of ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts coordinated with 1,3-dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene ligands. Org Lett. 1999;6:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Kessler H, Seip S. NMR of Peptide. In: Croasmun WR, Carlson RMK, editors. Two-dimensional NMR Spectroscopy: Application for Chemists and Biochemists. 2. VCH Publishers; New York: 1994. pp. 619–650. [Google Scholar]; (b) Braun S, Kalinowski HO, Berger S. 150 and More Basic NMR Experiments. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer TH, Davis P, Hruby VJ, Burks TF, Porreca F. In vitro potency, affinity and agonist efficacy of highly selective delta opioid receptor ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Vanderah TW, Brennan BB, Hochgeschwender U, Hruby VJ, Malan TP, Jr, Lai J, Porreca F. Pronociceptive actions of dynorphin maintain chronic neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1779–1786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01779.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szekeres PG, Traynor JR. Delta opioid modulation of the binding of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate to NG108-15 cell membranes: Characterization of agonist and inverse agonist effects. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1997;283:1284–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Misicka A, Lipkowski AW, Horvath R, Davis P, Kramer TH, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ. Topographical requirements for delta opioid ligands: Common structural features of dermenkephalin and deltorphin. Life Sci. 1992;51:1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90501-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hosohata K, Varga EV, Alfaro-Lopez J, Tang X, Vanderah TW, Porreca F, Hruby VJ, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. (2S,3R) β-methyl-2′,6′-dimethyltyrosine- L-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid [(2S,3R)TMT-L-Tic-OH] is a potent, selective δ opioid receptor antagonist in mouse brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:683–688. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hruby VJ, Toth G, Gehrig AC, Kao L-Fa, Knapp R, Lui GK, Yamamura HI, Kramer TH, Davis P, Burks TF. Topographically designed Analogues of c[D-Pen2, D-Pen5]enkephalin. J Med Chem. 1991;34:1823–1830. doi: 10.1021/jm00110a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Toth G, Russell KC, Landis G, Kramer TH, Fang L, Knapp R, Davis P, Burks TF, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ. Ring substituted and other conformationally tyrosine analogues of c[D-Pen2, D-Pen5]-enkephalin with δ opioid receptor selectivity. J Med Chem. 1992;35:2384–2391. doi: 10.1021/jm00091a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Ananthan S. Opioid ligands with mixed μ/δ opioid receptor interactions: An emerging approach to novel analgesics. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2006;8:118–125. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080114. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Horan PJ, Mattia A, Bilsky EJ, Weber S, Davis TP, Yamamura HI, Malatynska E, Appleyard SM, Slaninova J, Misicka A, Lipkowski AW, Hruby VJ, Porreca F. Antinociceptive profile of biphalin, a dimeric enkephalin analog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1446–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures and representative scheme of the synthesis of compounds 1–13, elemental analyses for products 6–11 and 13, HPLC and HR-MS for products 5–11 and 13, NMR analyses of products 1–13, and Roesy spectra of 8 and 9. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.