Abstract

Unique among the vascular beds, loss of endothelial integrity in the pulmonary microcirculation due to injury can lead to rapidly fatal hypoxemia. The ability to regain confluence and re-establish barrier function is central to restoring proper gas exchange. The adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a heterogeneous disease, however, meaning that endothelial cells within different regions of the lung do not likely see the same oxygen tension as they attempt to proliferate and re-establish an intact endothelial monolayer; the effect of hypoxia on the integrity of this newly formed endothelial monolayer is not clear. Immortalized human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVEC) (ST1.6R cells) were sparsely plated and grown to confluence over 4 days in either normoxia (21% oxygen) or hypoxia (5% oxygen). Confluence attained in a hypoxic environment resulted in a tighter, less permeable endothelial monolayer (as determined by an increase in transendothelial electrical resistance, decreased permeability to fluorescently labeled macromolecules, and decreased hydraulic conductance). PMVEC grown to confluence under hypoxia had decreased RhoA activity; consistent with this finding, inhibition of Rho kinase, a well-described downstream target of RhoA, markedly increased electrical resistance in normoxic, but not hypoxic, PMVEC. These results were confirmed in primary human and rat PMVEC. These data suggest that PMVEC grown to confluence under hypoxia form a tighter monolayer than similar cells grown under normoxia. This tighter barrier appears to be due, in part, to the inhibition of RhoA activity in hypoxic cells.

Keywords: human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells, hypoxia, permeability, RhoA/Rho kinase

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Re-establishing endothelial confluence in the pulmonary circulation is critical to restoring proper gas exchange after acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. These studies demonstrate that the oxygen tension at which this occurs impacts the integrity of the monolayer formed.

Disruption of the endothelial lining in the pulmonary circulation in response to sepsis, trauma, pancreatitis, or other insults can cause widespread alveolar flooding and life-threatening hypoxemia (1, 2). The ability to regain confluence and re-establish barrier function after injury is important to restoring proper gas exchange (3). Acute lung injury and its more severe manifestation, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), are heterogeneous diseases (4–6), however, meaning that endothelial cells within different regions of the lung do not likely see the same oxygen tension as they attempt to re-establish the vascular barrier. Areas where pulmonary microvessels are injured (and alveolar ventilation compromised) might be expected to see a profoundly hypoxic environment. The effect of hypoxia on the integrity and quality of the endothelial monolayer reformed after injury is not clear.

Intercellular junctions including endothelial tight junctions, focal adhesions, and adherent junctions are important in controlling permeability and are linked to the actin cytoskeleton (7); changes in endothelial permeability are accompanied by actin reorganization (8, 9). In in vitro experiments, hypoxia can disrupt monolayer integrity and increase endothelial permeability (10–12). Activation of the RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathway coupled with inhibition of Rac1 is thought to account for at least part of this increased permeability (11, 13). Most of those experiments focused on the effect of acute hypoxia on established monolayers, however. The effect of sustained hypoxia as endothelial cells form a monolayer is less well studied, but may be relevant to repair following acute lung injury.

In this article we demonstrate that human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVEC) form a tighter endothelial monolayer when grown to confluence under hypoxia (5% oxygen) compared with similar cells grown under normoxia (21% oxygen) in vitro. In addition, PMVEC grown to confluence under hypoxia had decreased RhoA activity; consistent with this finding, inhibition of Rho kinase, a well-described downstream target of RhoA, markedly increased the electrical resistance in normoxic, but not hypoxic, PMVEC monolayers. These data suggest that in contrast to the increased monolayer permeability seen with acute hypoxia, PMVEC grown to confluence under physiologically relevant hypoxia form a tighter monolayer than similar cells grown under normoxia. This tighter barrier appears to be due, in part, to the inhibition of RhoA activity in hypoxic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dulbecco's modified essential media (DMEM), Trypsin-EDTA, and L-glutamine were from Gibco (Grand Island, NY); fetal bovine serum (FBS) from HyClone (Salt Lake City, UT); HyBond-P from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK); and SuperSignal West Dura and SuperSignal West Femto both from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Y27632 (Rho kinase inhibitor, cat# 688,001), KN-62 (CaM kinase II inhibitor, cat# 422,706), Rac 1 inhibitor (cat# 553,502), and PP-2 (src tyrosine kinases inhibitor, cat# 529,573) were from CalBiochem (San Diego, CA). Chelerythrine chloride (PKC inhibitor, cat# c2932) and ML-7 (MLCK inhibitor, I2764) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture

Three different cell lines were used in these experiments. (1) A human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell line (line ST1.6R) immortalized by the addition of hTert (human telomerase reverse transcriptase) (14) (kindly provided by C. James Kirkpatrick, Institute of Pathology, Johannes-Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany), which were cultured in EGM2-MV growth medium. These cells form a monolayer of density-inhibited cells with a cobblestone-like morphology and possess the constitutively expressed endothelial markers vWF, CD31, and Flt-1 as well as the inducible cell adhesion molecules ICAM-1, E-Selectin, and VCAM-1. (2) Primary human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells purchased from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD) (Lung Microvascular Endothelial Cells, cat. # CC-2527), which were cultured in EGM2-MV growth medium (cat.#CC-4147; Clonetics, San Diego, CA). Cells were obtained from Cambrex at passage 4 and studied at passages 5 through 7. (3) Rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells isolated in our cell culture core laboratory (15) that were grown in DMEM/10% FBS.

Exposure to Hypoxia

PMVEC were plated sparsely in media and grown to confluence in humidified airtight chambers (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) that were gassed with 21% or 5% O2, 5% CO2 (balance nitrogen) for 10 minutes before being sealed; the chamber was re-flushed every 2 days. The chambers were maintained in a 37°C incubator for 1 to 12 days depending on the experimental design. Pressure was normalized 20 and 80 minutes after sealing.

Measurement of Transendothelial Electrical Resistance

Transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) was measured with the electrical cell impedance sensor (ECIS) technique as described (16, 17). In this system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY), cells are cultured to confluence on a small gold electrode (10−4 cm2) (ECIS cultureware, cat. # 8W10E; Applied Biophysics) and a 4,000-Hz AC signal with 1-V amplitude applied to the cells through a 1-MΩ resistor, creating an approximate constant current source (1 μA). Cells act as insulating particles, and the total resistance across the monolayer comprises the resistance between the ventral cell surface and the electrode and the resistance between cells.

Rho Activation Assay

To assess the amount of activated Rho (i.e., Rho-GTP), total protein extracts from PMVEC grown to confluence in 21 or 5% O2 were analyzed for Rho-GTP using the Rho Activation Kit (catalog # 17–294; Upstate, Temecula, CA) according to manufacture instructions. To determine the total amount of Rho capable of binding GTP, total protein aliquots were pre-incubated with 100 μM GTPγS to maximally activate Rho. The precipitates were visualized using an anti-Rho antibody.

Fluorescent Microscopy

PMVEC were grown to confluence on glass coverslips. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed in PBS, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes, and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes. The actin cytoskeleton was stained with Texas Red-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, the coverslips were mounted with a SlowFade antifade kit (Molecular Probes) and visualized.

Hydraulic Conductance

Experiments were performed on monolayers grown by seeding 80,000 cells/cm2 on 12-mm Transwell filters (0.4 μm pore size; Fisher Scientific, Sawanee, GA) as described in a previous paper (18) and grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen. Filters were then mounted on a 6-well plate using diffusion chamber (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) and perfused with growth medium at 37°C. Perfusate was circulated between the apical chamber and the reservoir using a Gilson roller pump. Perfusion pressure (P) was controlled by adjusting the reservoir height to 20, 30, 40, and 50 cm H2O, and filtration rates (Jv) were measured by timing the medium movements in volumetric pipettes for 30 minutes. Simultaneous liquid movement was recorded for all six chambers using a Watec video camera and Panasonic video recorder as previously described (18). Filtration rates were corrected for filtration surface area (A). Hydraulic conductance (Lp) in cm/second · cm H2O−1 · 10−7 was calculated for each monolayer using a regression of Jv/A on P at the different P states, where Lp equals the slope of the regression, or: Lp = Jv/A/P. A mean ± SE of the regression slopes for the two groups was used to calculate the Lp for each group. Differences between the two groups were determined using an unpaired t test.

Transendothelial Dextran Transport

PMVEC were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen in HTS FluoroBlok inserts (1 μm pore size, cat. # 351150; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The membrane inserts were filled with a total of 0.4 ml of perfusate containing FITC-labeled dextran (70 kD) to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. The lower well was filled with 1.2 ml medium of the same osmolarity as the inner well to minimize hydrostatic and osmotic effects. Transendothelial dextran permeability was measured in real time by detecting the appearance of FITC-labeled dextrans in the lower well using Fluoroskan Ascent CF system (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). The diffusional permeability (Pd) in cm/second was calculated at 10 minutes using the equation: Jp/Cp/S, where Jp = dextran flux in μg/second, Cp = initial concentration in top well in μg/cm3, and S = surface area in cm2.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM of three to five independent experiments. Cell growth, changes in TER, and changes in dextran permeability were compared using ANOVA combined with Fisher post hoc analysis, with a P value < 0.05 considered significant. Protein expression levels and Rho activity were compared using a two-tailed unpaired t test with a P value < 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

We first studied a human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell line (ST1.6R) immortalized by transfection with hTert (graciously provided by Dr. C. James Kirkpatrick, Institute of Pathology, Jahannes-Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany) (14). Cells were plated at low confluence (< 10% coverage) in either 24-well plates (for cell number) or on small gold electrodes (to measure transendothelial electrical resistance). Cell number was determined every 2 days and TER measured every 2 days once cells had attained confluence (as determined by visual examination under a light microscope). Cells were fed every 2 days; before replacing the media in the hypoxic cells, it was bubbled with 5% oxygen to prevent reoxygenation effects.

Human PMVEC Grown to Confluence under Hypoxia Form a Tighter, Less Permeable Monolayer

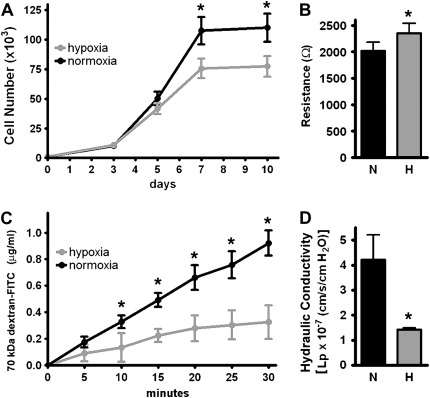

ST1.6R PMVEC grown in 5% oxygen had approximately 30% fewer cells at confluence (Figure 1A); despite this, hypoxic cells developed a higher TER than similar cells grown in 21% oxygen (Figure 1B). To confirm that the changes in TER correlated with changes in monolayer permeability, we demonstrated a decreased permeability to fluorescently labeled (70 kD) dextran in monolayers formed in 5% oxygen (Figure 1C) (Pd = 6.4 × 10−5 cm/s for normoxia and 2.6 × 10−5 cm/s for hypoxia). We then grew ST1.6R PMVEC on polyester membranes and determined hydraulic conductance (fluid translocation across the monolayer under pressure). Monolayers formed in 5% oxygen had decreased hydraulic conductance (less fluid translocation) compared with monolayers formed in 21% oxygen (Figure 1D). Taken together, these results indicate that the endothelial monolayer generated under hypoxia formed a tighter, less permeable barrier than monolayers formed in normoxia.

Figure 1.

Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVEC) (ST1.6R) form a tighter, less permeable monolayer when grown in hypoxia. ST1.6R PMVEC were plated sparsely and grown to confluence in 5% or 21% oxygen. (A) Cell growth over 10 days (n = 3). (B) Transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) at Day 10 (n = 10). (C) Monolayer permeability to 70 kD FITC-labeled dextran at Day 10 (n = 4) (Pd = 6.4 × 10−5 cm/s for normoxia, 2.6 × 10−5 cm/s for hypoxia, and 24.9 × 10−5 cm/s for the membrane insert without cells). (D) Hydraulic conductance at Day 10 (Lp = 4.2 × 10−7 for the normoxic monolayer, 1.4 x10−7 for the hypoxic monolayer, and 3.9 × 10−5 cm/s/cm H2O for the filter without cells) (n = 6) (*P < 0.05).

Decreased Rho/Rho Kinase Activation in PMVEC Grown to Confluence in Hypoxia

Many published papers report that acute hypoxia increases endothelial monolayer permeability (11, 12, 19) and may do so in part through activation of Rho/Rho kinase (11, 13). Our preliminary data demonstrate that PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia have decreased monolayer permeability, however. This suggested that Rho/Rho kinase was inhibited. Therefore we undertook these experiments to examine Rho/Rho kinase activity in these PMVEC under each condition.

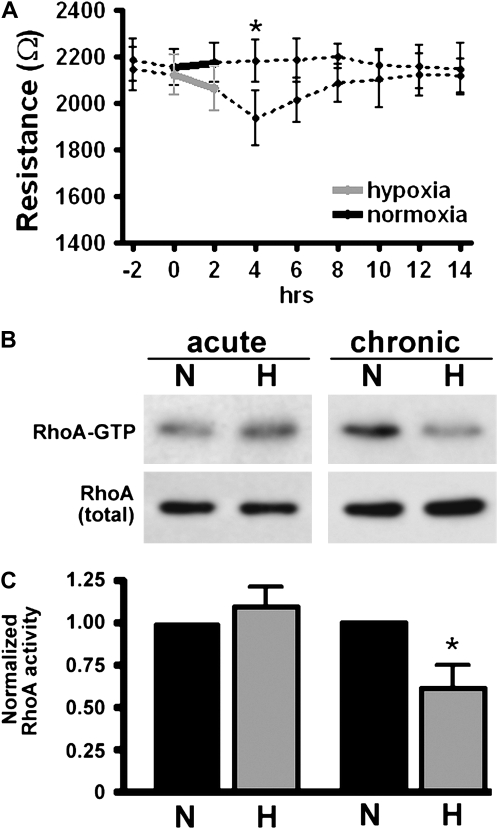

Human PMVEC (ST1.6R) were grown to confluence in normoxia or hypoxia as described above. Consistent with published reports, an established monolayer exposed to acute hypoxia (2 h of 5% oxygen) transiently decreased electrical resistance (Figure 2A); this was in contrast to the increased resistance seen in cells grown to confluence in hypoxia (Figure 1B). Rho activity, determined using a Rho-GTP pull down assay, demonstrated increased Rho activity in acute hypoxia, but decreased Rho activity in cells grown to confluence in (chronic) hypoxia (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

Acute and chronic hypoxia have different effects on TER and Rho activation in PMVEC monolayers. (A) Human PMVEC were grown to confluence in 21% oxygen. After obtaining a stable resistance baseline, cells were exposed to either 5% oxygen or continued in 21% oxygen for 2 hours (from 0–2 h, solid lines). Cells were then returned to 21% oxygen and TER measured every 2 hours for 14 hours. Acute hypoxia caused a transient drop in TER (2–6 h) followed by a return to baseline (n = 3). Cells were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen. Using the Rhotekin pull-down assay, Rho-GTP levels were determined from whole-cell lysates from either acutely hypoxic cells (Hour 4 in A) or at Day 10 in PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia (chronic). (B) Representative blot (N: normoxia, H: hypoxia). (C) Statistical data from three distinct experiments assessing Rho-GTP level. Rho activity was normalized to that in normoxic cells (*P < 0.05).

Confluence Attained under Hypoxia Increases TER in Primary Human PMVEC

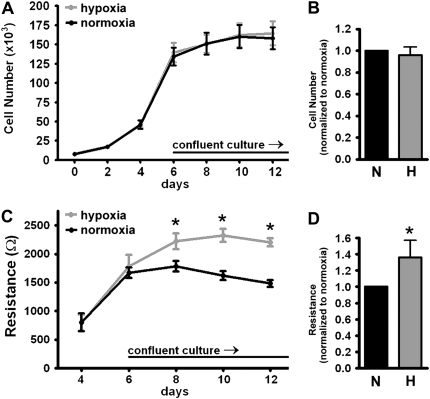

To determine whether growth under hypoxia had the same effect on nonimmortalized cells, primary human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (from Cambrex) were plated at low confluence as described above and grown to confluence under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Similar to our findings in the human PMVEC cell line (ST1.6R), the TER of the PMVEC grown under hypoxia was significantly higher than cells grown under normoxia (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Primary (nonimmortalized) human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell monolayers formed in hypoxia have an increased TER. Primary human PMVEC were plated sparsely and grown to confluence under 5% O2 (hypoxia) or 21% O2 (normoxia). Cells were counted every 2 days: (A) cell growth over 12 days, and (B) cell number normalized to normoxia at Day 10 (N: normoxia, H: hypoxia) (n = 3 experiments, P = ns). Once cells were confluent, TER was measured every 2 days: (C) TER (in ohms) at each time point and (D) TER normalized to the normoxic monolayer at Day 10 (n = 3 separate experiments; *P < 0.05 based on ANOVA [C] or paired t test [D]).

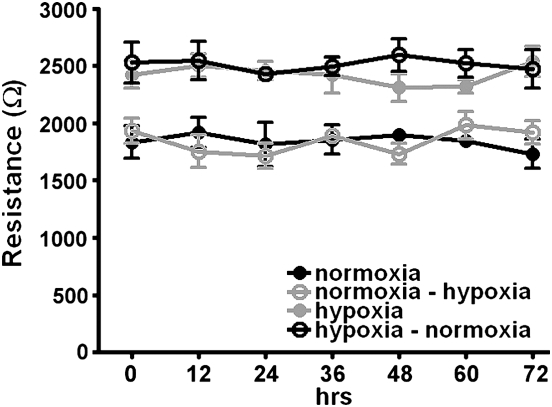

To determine whether this difference in resistance was acutely reversible, we grew primary human PMVEC to confluence under either 5% or 21% oxygen, measured monolayer resistance, and then switched the oxygen tensions (i.e., the cells which came to confluence at 5% oxygen were then incubated in 21% oxygen and vice versa). The increased resistance in cells grown under hypoxia persisted despite the return to normoxia (Figure 4). If PMVEC that were grown to confluence in 5% oxygen were then trypsinized, re-plated, and allowed to grow to confluence in 21% oxygen, the monolayer resistance decreased to that seen with cells originally grown in 21% oxygen (data not shown), indicating that it was the current oxygen environment, rather than cell memory, that dictated monolayer resistance.

Figure 4.

Increased TER persists in hypoxic monolayers despite return to normoxia. Primary human PMVEC (Cambrex) were grown to confluence in each oxygen condition. Once a stable monolayer was established (Day 4 after confluence), hypoxic cells were returned to 21% oxygen (normoxia) and normoxic cells exposed to 5% oxygen (hypoxia); TER was measured every 12 hours for 72 hours. The change in oxygen tension had no effect on TER in either group (n = 3 experiments).

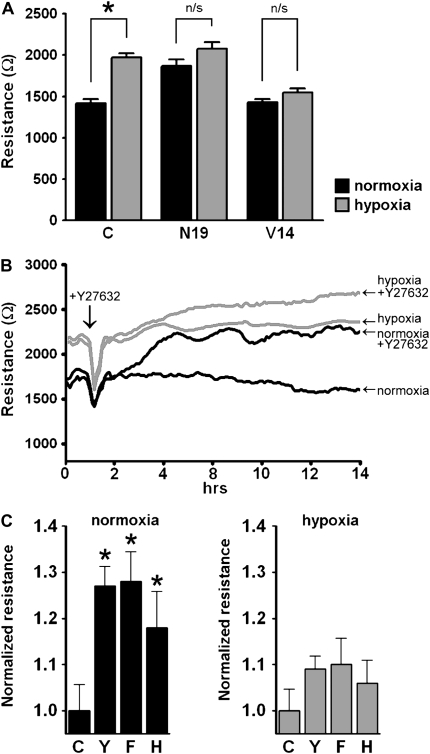

Rho Kinase Inhibition Increases TER in Primary Human PMVEC

Our previous data suggested that human PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia had less RhoA activation than cells grown under 21% oxygen. To further explore this hypothesis we stably transfected primary human PMVEC with either dominant-negative (N19) or constitutively active (V-14) RhoA (generously provided by Dr. Senger, Harvard Medical School [20]) and grew them to confluence in both conditions. As predicted from our previous data, cells expressing a dominant-negative mutation of RhoA (N-19) formed a tighter monolayer even in normoxia, whereas cells expressing the constitutively active mutation (V-14) formed a monolayer with decreased electrical resistance even when grown in 5% oxygen (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Inhibiting RhoA/Rho kinase signaling increased TER in human PMVEC. (A) Primary human PMVEC were stably transfected with either the dominant-negative (N-19) or the constitutively active (V-14) RhoA mutant, grown to confluence in 21% or 5% oxygen, and TER measured (n = 3, *P < 0.05). Dominant-negative RhoA increased monolayer resistance in normoxia and constitutively active RhoA decreased monolayer resistance in hypoxia. (B) Inhibiting Rho kinase increased TER in PMVEC monolayer. Human PMVEC were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen. After obtaining a stable baseline, either 5 μmol/L Y27632 (Rho kinase inhibitor) or vehicle (saline) was added to the monolayer and TER measured continuously over 14 hours. Y27632 increased TER in both monolayers, but had a much greater effect on the monolayer formed in normoxia, suggesting that there was less active RhoA in the hypoxic monolayer. (Representative tracing of three separate experiments.) (C) Inhibiting Rho kinase increased TER in normoxic cells. Human PMVEC were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen. TER was measured 8 hours after the addition of either vehicle control or the agent and values normalized to vehicle-treated cells. Control (C) and Rho kinase inhibitors: Y, Y27632 (5 μmol/L); H, HA 1,100 hydrochloride (10.7 μmol/L); and F, Fasudil (10.7 μmol/L).

Consistent with this finding, inhibition of Rho kinase, a well-described downstream target of RhoA, increased electrical resistance to a greater degree in normoxic cells compared with hypoxic ones (Figures 5B and 5C), suggesting that there is less baseline Rho kinase activity in hypoxic PMVEC. In contrast, pharmacologic inhibition of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), protein kinase C (PKC), calcium/Calmodulin, and the SRC family of protein tyrosine kinases had no effect on monolayer resistance (data not shown). Similarly, pharmacologic inhibition of Rac 1 had no effect on membrane resistance (data not shown).

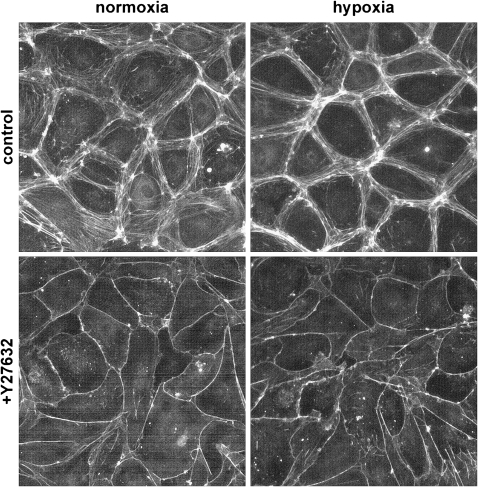

Hypoxia Increases Cortical Actin in Human PMVEC

Primary human PMVEC grown to confluence in either hypoxia or normoxia were stained with Texas Red–phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton. Figure 6 shows that PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia have more cortical actin than cells grown in normoxia. Localization of actin to the endothelial cell membrane strengthens the integrity of the monolayer (7, 11) and is consistent with our previous data demonstrating that exposure to hypoxia during proliferation yields a tighter, less permeable monolayer. Inhibition of Rho kinase with Y27632 led to further translocation of the actin cytoskeleton to the cell membrane in both monolayers, indicating that Rho kinase was not completely inhibited in the hypoxic PMVEC.

Figure 6.

PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia have more cortical actin than PMVEC grown in normoxia. Cells were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen; the monolayer was then stained with Texas Red–phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton. Cells grown under hypoxia demonstrated more cortical actin than cells grown under normoxia. The addition of the Rho kinase inhibitor, Y27632, led to further translocation of the actin cytoskeleton to the membrane in both monolayers.

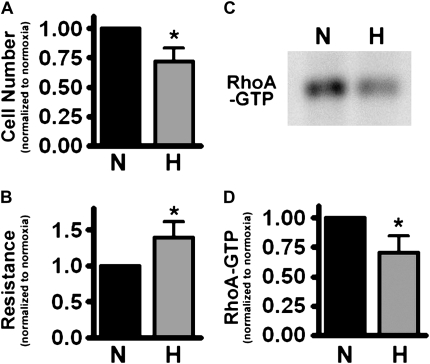

Confluence Attained under Hypoxia Increases TER in Rat PMVEC

To confirm our key observations (increased monolayer resistance with inhibition of the Rho/Rho kinase pathway in PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia) in another cell type, we performed similar experiments in a well-defined population of rat PMVEC (15). Similar to our findings in both the immortalized human PMVEC cell line (ST1.6R) and the human primary PMVEC, rat PMVEC grown to confluence in 5% oxygen formed a monolayer with increased transendothelial electrical resistance (Figure 7B); we also demonstrated decreased RhoA activation in the chronically hypoxic rat PMVEC (Figures 7C and 7D). This observation indicates that the barrier-enhancing effect of hypoxia on endothelial monolayers is not restricted to humans.

Figure 7.

Rat PMVEC grown in hypoxia also form a tighter monolayer. Well-characterized rat PMVEC were grown to confluence in either 5% or 21% oxygen. (A) Cell number at Day 10. (B) TER at Day 10. (C) Representative blot of RhoA-GTP pull-down assay at Day 10. (D) Statistical data from three distinct RhoA-GTP pull-down assays (normalized to normoxic monolayer) (*P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrate that the oxygen tension at which pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells come to confluence has an important impact on the integrity of the monolayer formed; specifically that monolayers formed in hypoxia develop a tighter, less permeable barrier than similar monolayers formed in normoxia. Furthermore, these studies demonstrate that the RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathway is blunted by this degree of hypoxia, and this appears to account for a large component of the differences in monolayer permeability. The degree of hypoxia studied, 5% oxygen (40–50 mm Hg), is clinically relevant and would correlate with the in vivo oxygen tension seen by pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells trying to restore the monolayer in areas of shunt after acute lung injury.

The effect of hypoxia on endothelial monolayer permeability has been examined in a number of published papers. In a series of papers (10, 19), Ogawa and colleagues demonstrate that exposure of a bovine aortic endothelial cell monolayer to severe hypoxia (12–14 mm Hg) led to an increase in transport of radiolabeled inulin and sorbitol across the monolayer. In 1995, Catherine Partridge demonstrated that the permeability of a confluent monolayer of (bovine pulmonary artery) endothelial cells increased within the first 4 to 6 hours after exposure to hypoxia (3% oxygen), although by 24 hours, the permeability of the monolayer had actually decreased relative to baseline (12). More recent studies have also demonstrated an increase in monolayer permeability in cells exposed to hypoxia. Wojciak-Stothard and colleagues demonstrated that acute hypoxia (5 min to 4 h of 3% oxygen) increased monolayer permeability and did so in part through the activation of RhoA and inhibition of Rac1 (11). These papers as well as a number of others (21, 22) have established a paradigm in which hypoxia increases endothelial monolayer permeability.

In all the experiments cited above, endothelial cells were grown to confluence in ambient air (21% oxygen) before the monolayer was exposed to acute hypoxia. Our intent was to understand the effect of oxygen tension on monolayer integrity as cells came to confluence. We demonstrated that in contrast to the effects of acute hypoxia on the permeability of an established monolayer, exposure to hypoxia during monolayer formation led to a tighter, less permeable barrier. Since we were able to re-produce the effects of acute hypoxia on monolayer permeability, and since the barrier-enhancing effect of chronic hypoxia was seen in three different cell lines, we believe our observations are not merely due to differences in cell culture conditions.

Intercellular junctions including endothelial tight junctions, focal adhesions, and adherent junction are important in controlling permeability and are linked to the actin cytoskeleton (7). Actin maintains endothelial integrity by anchoring cells to its neighbors or to the extracellular matrix. The Rho/Rho kinase signaling pathway is important in controlling stress fiber and actin cytoskeleton localization (23, 24). We found a difference between the effects of acute and chronic hypoxia on Rho/Rho kinase signaling in PMVEC. Consistent with previous papers (11, 13), we demonstrated that when an established monolayer was exposed to acute hypoxia, RhoA was activated; when PMVEC were grown to confluence in hypoxia, however, Rho/Rho kinase activity was blunted. This decrease in Rho/Rho kinase activity correlated with the increased cortical actin seen in PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia. Therefore, while Rho/Rho kinase signaling is not the only pathway that regulates endothelial permeability, it is reasonable to speculate that the decreased Rho/Rho kinase activity in PMVEC grown to confluence in hypoxia was responsible for a large part of the observed increase in monolayer resistance.

The importance of pulmonary microvascular endothelial injury in acute lung injury and ARDS has been debated. When describing the histology of patients with ARDS (25, 26), Bachofen and Weibel noted alveolar epithelial damage with a relatively preserved endothelial monolayer, suggesting that endothelial injury was not a critical part of this syndrome. Significant animal and human data strongly suggest that extensive endothelial injury does occur in acute lung injury/ARDS, however, and that failure to repair the integrity of the pulmonary microcirculation worsens outcome. Increased levels of circulating endothelial cells and soluble adhesion molecules in patients with sepsis and acute lung injury have been demonstrated in clinical studies (27, 28), suggesting the presence of endothelial injury. Bovine pulmonary artery explants exposed to Escherichia coli endotoxin resulted not only in an increase in monolayer permeability, but scattered endothelial cell death by 2 hours (29).

More direct evidence that endothelial repair after acute lung injury is important comes from a recent study by Zhao and colleagues (3) that examined the effect of inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation in mice exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The authors demonstrated that LPS-mediated acute lung injury is significantly more severe in mice in which endothelial proliferation is impaired due to deletion of the transcription factor forkhead box M1. Such mice demonstrated a protracted period of increased lung vascular permeability with a marked increase in mortality. Taken together, these papers suggest an important role for the pulmonary microvascular endothelium in determining both the severity of acute lung injury and the speed from which the lung recovers from it.

In summary, we have found that human PMVEC grown to confluence in clinically relevant hypoxia form tighter, less permeable monolayers than cells grown in normoxia. The implications of this observation are not clear. Tighter barrier function might be considered a benefit by preventing the translocation of fluid from the pulmonary vasculature into the interstitial and alveolar space. Conversely, the formation of a tighter barrier in hypoxia might impair migration and proliferation that could delay vessel repair. Furthermore, it is not clear whether this in vitro observation mimics the effect of hypoxia on endothelial monolayer formation in the complicated in vivo environment associated with the development of, and recovery from, acute lung injury. This will require additional studies. These findings do suggest, however, that the effect of hypoxia on endothelial barrier formation is determined by both the severity and duration of exposure. In acute lung injury in which injury and repair occur over days and weeks, this effect of oxygen tension on endothelial cells may be relevant to understanding the variable course of this disease.

Funding for this project was provided by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH RO1 award, RO1 HL70273–01 (B.F.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0127OC on November 29, 2007

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, Bhattacharya J, Coller B, Doerschuk CM, Floros J, Gimbrone MA Jr, Hoffman E, Hubmayr RD, et al. Future research directions in acute lung injury: summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1027–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1334–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao YY, Gao XP, Zhao YD, Mirza MK, Frey RS, Kalinichenko VV, Wang IC, Costa RH, Malik AB. Endothelial cell-restricted disruption of FoxM1 impairs endothelial repair following LPS-induced vascular injury. J Clin Invest 2006;116:2333–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L, Presenti A, Torresin A, Baglioni S, Rivolta M, Rossi F, Scarani F, Marcolin R, Cappelletti G. Adult respiratory distress syndrome profiles by computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging 1986;1:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L, D'Andrea L, Pelosi P, Vitale G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. Regional effects and mechanism of positive end-expiratory pressure in early adult respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 1993;269:2122–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, Russo S, Patroniti N, Cornejo R, Bugedo G. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1775–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waschke J, Curry FE, Adamson RH, Drenckhahn D. Regulation of actin dynamics is critical for endothelial barrier functions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;288:H1296–H1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waschke J, Drenckhahn D, Adamson RH, Curry FE. Role of adhesion and contraction in Rac 1-regulated endothelial barrier function in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;287:H704–H711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waschke J, Baumgartner W, Adamson RH, Zeng M, Aktories K, Barth H, Wilde C, Curry FE, Drenckhahn D. Requirement of Rac activity for maintenance of capillary endothelial barrier properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H394–H401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa S, Shreeniwas R, Brett J, Clauss M, Furie M, Stern DM. The effect of hypoxia on capillary endothelial cell function: modulation of barrier and coagulant function. Br J Haematol 1990;75:517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojciak-Stothard B, Tsang LY, Haworth SG. Rac and Rho play opposing roles in the regulation of hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced permeability changes in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L749–L760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partridge CA. Hypoxia and reoxygenation stimulate biphasic changes in endothelial monolayer permeability. Am J Physiol 1995;269:L52–L58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojciak-Stothard B, Tsang LY, Paleolog E, Hall SM, Haworth SG. Rac1 and RhoA as regulators of endothelial phenotype and barrier function in hypoxia-induced neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L1173–L1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unger RE, Krump-Konvalinkova V, Peters K, Kirkpatrick CJ. In vitro expression of the endothelial phenotype: comparative study of primary isolated cells and cell lines, including the novel cell line HPMEC-ST1.6R. Microvasc Res 2002;64:384–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King J, Hamil T, Creighton J, Wu S, Bhat P, McDonald F, Stevens T. Structural and functional characteristics of lung macro- and microvascular endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc Res 2004;67:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia JG, Schaphorst KL, Verin AD, Vepa S, Patterson CE, Natarajan V. Diperoxovanadate alters endothelial cell focal contacts and barrier function: role of tyrosine phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol 2000;89:2333–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaphorst KL, Chiang E, Jacobs KN, Zaiman A, Natarajan V, Wigley F, Garcia JG. Role of sphingosine-1 phosphate in the enhancement of endothelial barrier integrity by platelet-released products. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;285:L258–L267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker JC, Stevens T, Randall J, Weber DS, King JA. Hydraulic conductance of pulmonary microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L30–L37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa S, Gerlach H, Esposito C, Pasagian-Macaulay A, Brett J, Stern D. Hypoxia modulates the barrier and coagulant function of cultured bovine endothelium: increased monolayer permeability and induction of procoagulant properties. J Clin Invest 1990;85:1090–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoang MV, Whelan MC, Senger DR. Rho activity critically and selectively regulates endothelial cell organization during angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:1874–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer S, Wobben M, Marti HH, Renz D, Schaper W. Hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells involves VEGF-mediated changes in the expression of zonula occludens-1. Microvasc Res 2002;63:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayyali US, Pennella CM, Trujillo C, Villa O, Gaestel M, Hassoun PM. Cytoskeletal changes in hypoxic pulmonary endothelial cells are dependent on MAPK-activated protein kinase MK2. J Biol Chem 2002;277:42596–42602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An SS, Pennella CM, Gonnabathula A, Chen J, Wang N, Gaestel M, Hassoun PM, Fredberg JJ, Kayyali US. Hypoxia alters biophysical properties of endothelial cells via p38 MAPK- and Rho kinase-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2005;289:C521–C530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wojciak-Stothard B, Potempa S, Eichholtz T, Ridley AJ. Rho and Rac but not Cdc42 regulate endothelial cell permeability. J Cell Sci 2001;114:1343–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Basic pattern of tissue repair in human lungs following unspecific injury. Chest 1974;65:14S–19S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Structural alterations of lung parenchyma in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med 1982;3:35–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutunga M, Fulton B, Bullock R, Batchelor A, Gascoigne A, Gillespie JI, Baudouin SV. Circulating endothelial cells in patients with septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burnham EL, Taylor WR, Quyyumi AA, Rojas M, Brigham KL, Moss M. Increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells are associated with survival in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyrick BO, Ryan US, Brigham KL. Direct effects of E coli endotoxin on structure and permeability of pulmonary endothelial monolayers and the endothelial layer of intimal explants. Am J Pathol 1986;122:140–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]