Abstract

Several cell-based immunotherapy strategies have been developed to specifically modulate T cell–mediated immune responses. These methods frequently rely on the utilization of tolerogenic cell–based antigen-presenting cells (APCs). However, APCs are highly sensitive to cytotoxic T-cell responses, thus limiting their therapeutic capacity. Here, we describe a novel bead-based approach to modulate T-cell responses in an antigen-specific fashion. We have generated killer artificial APCs (κaAPCs) by coupling an apoptosis-inducing α-Fas (CD95) IgM mAb together with HLA-A2 Ig molecules onto beads. These κaAPCs deplete targeted antigen-specific T cells in a Fas/Fas ligand (FasL)–dependent fashion. T-cell depletion in cocultures is rapidly initiated (30 minutes), dependent on the amount of κaAPCs and independent of activation-induced cell death (AICD). κaAPCs represent a novel technology that can control T cell–mediated immune responses, and therefore has potential for use in treatment of autoimmune diseases and allograft rejection.

Introduction

The major goal in the treatment of autoimmunity and allograft rejection is controlling autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) directed at self-antigens. Current therapeutic approaches are mostly based on immunosuppressive drugs that globally suppress the immune system.1,2 While successful, these treatments make the patients vulnerable to infections and possibly even the development of cancer. In order to selectively target autoreactive CTLs without compromising normal immune functions, new strategies need to be developed. The steadily increasing knowledge of antigen-presenting cell (APC)/T-cell interactions,3–6 newly identified APC and T-cell subsets,7,8 and the observation that some tumor cells express Fas ligand (FasL; CD95L) on their surface to evade T cell–mediated antitumor responses9–12 has led researchers to design new approaches to induce T-cell inhibition or deletion

One approach to inhibiting or deleting autoreactive CTLs in the setting of autoimmune disease and allograft rejection is based on genetically modified dendritic cells (DCs) that express the apoptosis-inducing ligand FasL.13–20 We and others have previously demonstrated in various murine models and cell lines that FasL expressing DCs can be used for antigen-specific deletion of unwanted CTLs.16,21 While these results are promising, there are several problems related to the use of autologous DCs. DC preparation is time, cost, and labor intensive, and the resulting cell product is highly variable in quality and quantity from donor to donor and from preparation to preparation. In addition, mature killer DCs express high levels of costimulatory molecules such as B7.1 and B7.2, which could be counterproductive by stimulating antiapoptotic processes.22 Furthermore, while killer DCs can be pulsed with peptides of interest, they will also present other previously acquired antigens, potentially leading to deletion of unwanted or unidentified T cells. For the same reason, gene transfer strategies using viral vectors are limited to in vitro studies, as virally transduced killer DCs will present viral antigens, thus causing a suppressed immune response if the patient becomes infected with the native virus. Moreover, all cellular-based DCs or APCs approaches are sensitive to their in vivo and in vitro environment, as the cytolytic effector activity of T cells23 may lead to DC depletion or unwanted changes in cell-cell signaling.

To overcome issues related to the use of cell-based killer APCs, we have developed a new bead-based approach to inhibit or delete self-reactive CTLs in an antigen-specific fashion for the treatment of autoimmune disease and allograft rejection. Based on our previous work using artificial APCs (aAPCs)24 and our experiences with FasL-expressing killer DCs,25,26 we have designed killer aAPCs (κaAPCs), made by coupling HLA-A2 Ig and α-Fas IgM mAb covalently to the surface of beads. In this study, we have successfully used κaAPCs to delete antigen-specific CTLs in vitro from a mixture of T cells with various specificities.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Regensburg.

Peptides

The following HLA-A2–restricted peptides have been synthesized by the Johns Hopkins University core facility and used throughout the experiments: human cytomegalovirus pp65–derived peptide (CMVpp65; NLVPMVATV) and modified melanoma-associated antigen peptide (Mart-1; ELAGIGILTV). The purity (> 98%) of each peptide was confirmed by mass-spectral analysis and high-pressure liquid chromatography. In addition, peptides (purity greater than 95%) were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Peptides were dissolved in 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 1 mg/mL and sterile-filtered through a 0.22-μm SpinX (Corning, Corning, NY).

Generation of human antigen-specific CTLs using aAPCs

aAPCs have been generated as previously described and used to expand Mart-1– and CMVpp65-specific CTLs.24 Briefly, purified CD8+ T cells of HLA-A2+ donors (106) were cultured with Mart-1aAPCs or CMVpp65aAPCs (106 each) in complete RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% autologous plasma and 3% T-cell growth factor (TCGF) in 96-well round bottom plates (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) in a humidified incubator providing 5% CO2 and 37°C for 1 week, respectively. Medium and TCGF were replenished once a week. Specificity of CTLs was monitored each week and directly before use by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Generation of κaAPCs and control beads

κaAPCs were generated by coupling HLA-A2 IgG1 (0.018 μg/mL) and α-Fas IgM mAb, (clone CH11; Upstate, Chicago, IL; 3.64 μg/mL) onto 108 epoxy beads (Dynal/Invitrogen, Oslo, Norway). Briefly, beads were washed twice in sterile 0.1 M borate buffer and then loaded in borate buffer overnight at 4°C on a rotator. The next day, the beads were washed twice with 1 mL bead wash (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 0.001% NaN3, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) and incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotator. Finally, the beads were placed into 1 mL fresh PBS (GIBCO/Invitrogen) and loaded with either CMVpp65 or Mart-1 peptide (10 μg/mL) at 4°C overnight. Before use, κaAPCs were washed several times. Control beads were prepared in identical fashion but lacking the α-Fas IgM mAb (clone CH11).

Cocultures

Cocultures were established by placing expanded antigen-specific CTLs in 96-well round-bottom plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well together with control beads (CBs) or κaAPCs, which have been unloaded or loaded with indicated peptides. A bead–T-cell ratio of 1:1 was used throughout the experiments if not stated differently. Soluble α-Fas IgM (clone CH11) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL served as positive control. Cocultures established with complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 3% autologous plasma or human AB serum (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) and 3% TCGF alone served as negative controls. Plates were incubated in a humidified incubator providing 5% CO2 and 37°C for 45 to 48 hours.

CD107a assay

Antigen-specific CTLs were placed in 96-well round-bottom plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well. Prior to stimulation, 12.5 μL α–human CD107a PE-Cy5 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) were added into each well (200 μL). After an incubation periode of 5 hours, samples were harvested, stained, and immediately analyzed.

PKH26/PKH67 assay

According to previous publications,27 CTLs were transferred to polystyrene tubes (BD Falcon) and washed twice with serum-free media (RPMI-1640). Cells were then resuspended in Diluent C (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany). The dye solution (PKH26 and PKH67, respectively) was added rapidly and incubated for 7 minutes on a shaker. Cells were then washed 3 times with RPMI-1640 containing 10% human AB serum (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany). Differently stained autologous CTLs were then mixed, resulting in a 1:1 ratio, and placed in 96-well round-bottom plates at a final concentration of 1.5 × 105 cells/well. Following incubation for 45 to 48 hours in a humidified incubator providing 5% CO2 and 37°C, cells were harvested and stained with 5 μL 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) and 5 μL annexin V–allophycocyanin (both from BD Pharmingen) for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Samples were immediately analyzed.

Flow cytometry

Cells or beads were stained with α–mouse IgM mAb–FITC (clone R6-60.2; BD Pharmingen), α–mouse IgG1 mAb–PE (BD Pharmingen), and α–human CD8 mAb–FITC (clone UCHT-4; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 4°C for 10 to 15 minutes. Prior to antibody stain, HLA-A2 tetramer (Immunomics, Beckmann Coulter, Marseille, France) stain was performed for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Apoptosis assays were conducted according to the manufacturer's protocol (ApoAlert annexin V Apoptosis Kit; BD Pharmingen). FACS analysis was carried out on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). All flow cytometry data were analyzed with either FCSExpresss 3 (De Novo Software, Thornhill, ON) and/or WinMDI2.8 (http://facs.scripps.edu/software.html). Numbers of viable cells were determined by the amount of Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) or 7-AAD double-negative cells. Untreated control cultures were set to 100%, whereas the percentage of viable cells in specifically treated cultures was calculated as % viable cells = (% treated cells × 100%) / % untreated cells.

Results

Generation of κaAPCs

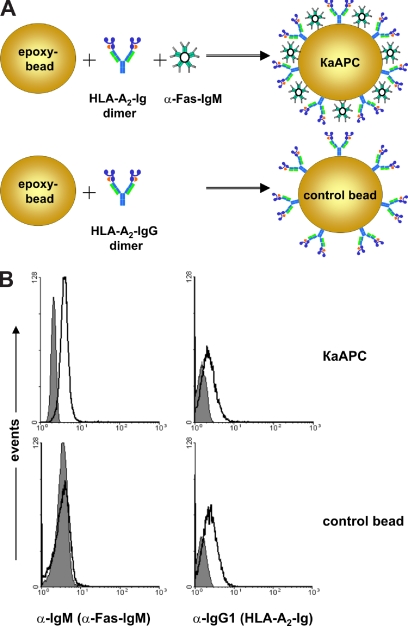

Previously, we developed an HLA-A2 Ig–based aAPC for ex vivo expansion of antigen-specific CTLs.24 Based on this technology, we designed a κaAPC that would induce the depletion of CD8+ T cells in an antigen- and HLA-dependent manner (Figure 1A). In this system, peptide-loaded HLA-A2 Ig was used to provide an antigen-specific signal, and α-Fas IgM (clone CH11) provided an apoptosis-inducing signal. Together, these signals should initiate apoptosis in T cells specific for the peptide-HLA of interest via the Fas/FasL signaling pathway. CBs were made by coating with HLA-A2 Ig in the absence of any apoptosis signal.

Figure 1.

Composition and phenotypical characterization of κaAPC and control beads (CB). (A) Composition of a HLA-A2 IgG1–based κaAPC and CB. (B) FACS analysis of IgM (α-Fas mAb; left panels) and IgG1 (HLA-A2 IgG1; right panels) immobilized on CBs and κaAPCs. ■ represents the isotype control, whereas □ indicates α-Fas mAb (clone CH11) and HLA-A2 IgG1.

To confirm the phenotype of κaAPCs and CBs, FACS analysis was performed (Figure 1B). Staining with an α–mouse IgM mAb and an α–mouse IgG1 mAb demonstrated that κaAPCs displayed both α-Fas IgM (clone CH11) and HLA-A2 Ig immobilized to the bead surface, whereas CBs lacked the apoptosis-inducing signal but had equal amounts of HLA-A2 Ig (Figure 1B left and right panels). Phenotypes of all κaAPCs and the corresponding controls (CBs) used throughout the experiments have been routinely analyzed in this manner.

Antigen-specific apoptosis induction by κaAPCs

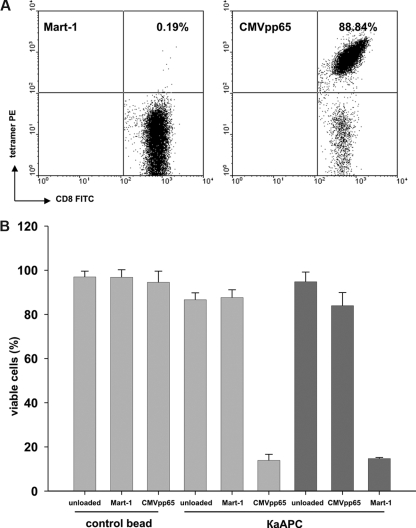

To investigate whether κaAPCs delete primary human CD8+ T cells in an antigen-specific manner, CD8+ T cells were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy donors, expanded as described,24 and used as targets for κaAPCs. Figure 2A shows a representative tetramer analysis of primary CMVpp65-specific CTLs that were used throughout the experiments.

Figure 2.

Elimination of CMVpp65-specific CTLs by CMVpp65κaAPCs. (A) An example of CMVpp65-specific CTLs used throughout the experiments. CTLs were specifically stained with CMVpp65 tetramer (88.84%). Mart-1 tetramer (0.19%) served as control stain. (B) Elimination of (▓) CMVpp65- or (▒) Mart-1–specific CTLs from different donors in cocultures with CBs or κaAPCs loaded with CMVpp65 or Mart-1 peptide. Cocultures with unloaded CBs or κaAPCs served as negative controls. Numbers of viable cells (% viable cells = (% treated cells × 100%) /% untreated cells) after 48 hours of coculture are depicted (means ± SD) of 5 independent experiments.

To distinguish viable cells from apoptotic cells, we simultaneously stained with annexin V and PI. Annexin V is known to bind phosphodidylserine (PS) under high Ca2+ conditions and therefore detects early apoptotic events. Annexin Vhigh T-cell populations are almost exclusively apoptotic and also stain positive for PI.28 PI has been demonstrated to intercalate into fragmented DNA and therefore detects late apoptotic events. The combination of both annexin V+ and PI+ staining ensures a reliable exclusion of dead cells and therefore an accurate determination of viable, nonapoptotic cells (annexin V/PI double-negative).

CMVpp65-specific CTLs generated from different donors were cocultured with κaAPCs loaded with the specific peptide CMVpp65 (CMVpp65κaAPCs), κaAPCs loaded with noncognate Mart-1 peptide (Mart-1κaAPCs), unloaded κaAPCs (unloadedκaAPCs), or with corresponding CBs lacking the apoptosis signal (CMVpp65CBs, Mart-1CBs, and unloadedCBs; Figure 2B). The amount of viable cells (VCs; annexin V−/PI− population) after 48 hours of coculture was compared. There was a strong induction of apoptosis in CMVpp65-specific CTLs cocultured with CMVpp65κaAPCs; only 13% of the CTLs remained viable, whereas unloaded and noncognate peptide–loaded κaAPCs and CBs induced apoptosis only slightly above background levels (VCs, 88%-97%).

CMVpp65 (NLVPMVATV) is known to be a high-affinity peptide. Additional experiments were performed using CD8+T cells directed toward the low-affinity modified Mart-1 peptide (ELAGIGILTV), which is derived from a melanocyte self-antigen. Mart-1–specific CTLs generated from different donors were cocultured with Mart-1κaAPCs, CMVpp65κaAPCs, and unloadedκaAPCs (Figure 2B). As observed with CMVpp65κaAPCs, Mart-1κaAPCs induced strong apoptosis during coculture with their cognate targets; thus, only 15% of the cells remained viable, whereas unloadedκaAPCs did not induce apoptosis (VCs, 95%). In addition, apoptosis at background levels was observed in all control cultures with CMVpp65κaAPCs (VCs, 84%) and Mart-1CBs, CMVpp65CBs, and unloadedCBs (VCs, 87%-95%; data not shown). Apoptosis of CTLs was only slightly elevated in cocultures with unloaded and non–cognate-loaded κaAPCs as compared with cocultures with CBs. These results demonstrate that κaAPCs can be used to efficiently delete CTLs in an antigen-specific fashion.

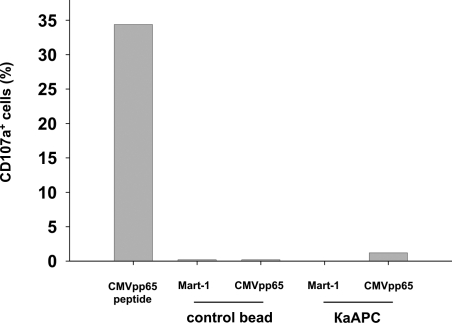

To analyze the mechanism of κaAPCs, we investigated whether cell/bead contact led to an activation of antigen-specific CTLs and subsequent activation-induced cell death (AICD). It has been demonstrated that CD107a is expressed on the cell surface of CD8+ T cells shortly after activation with cognate peptide, and that these cells mediate cytolytic activity in an antigen-specific manner.29 Therefore, we examined the amount of CD107a expressed on the surface of CMVpp65-specific CTLs 5 hours after initiation of cocultures with cognate- and non–cognate-loaded κaAPCs and CBs (Figure 3). As a positive control, CMV-specific CTLs were stimulated with soluble CMVpp65 peptide, which induced strong CD107a up-regulation. In contrast, cocultures of CMVpp65-specific CTLs with CMVpp65κaAPCs did not induce up-regulation of CD107a, but did induce substantial apoptosis in CMVpp65-specific CTLs (data not shown). In contrast, Mart-1κaAPCs and CBs loaded with either CMVpp65 or Mart-1 peptide did not induce cell death or CD107a up-regulation in CMVpp65-specific CTLs. Similar results were obtained in a cytokine-based effector assay (data not shown), which substantiated the CD107a observations.

Figure 3.

Cell/bead contact does not lead to an activation of antigen-specific CTLs and subsequent AICD. Activation in CMVpp65-specific CTLs of a single donor cocultured with Mart-1CBs, CMVpp65CBs, Mart-1κaAPCs, or CMVpp65κaAPCs. CTL cultures stimulated with 7.5 ng/mL soluble CMVpp65 peptide served as positive control. Numbers of CD107a+ cells were determined 5 hours following initiation of cocultures. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

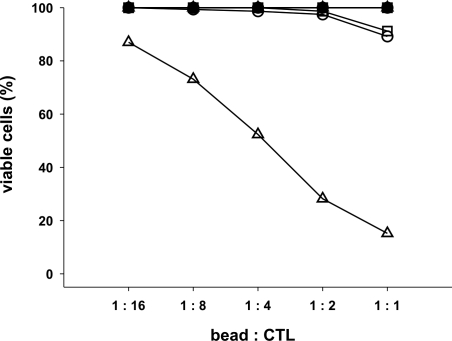

κaAPCs induce apoptosis in a dose-dependent fashion

To further characterize the apoptosis-inducing capacity of κaAPCs, CMVpp65-specific CTLs were cocultured with different amounts of κaAPCs or CBs either unloaded or loaded with the cognate CMVpp65 or the noncognate Mart-1 peptide. As revealed in Figure 4, induction of apoptosis in CMVpp65-specific CTLs by CMVpp65κaAPCs was directly dependent on the κaAPC/CTL ratio. While 87% of the CTLs remained viable at a ratio of 1:16, only 15% of viable CTLs were detected after cocultures, with a bead/CTL ratio of 1:1. Consistent with previous results, all other nonspecifically loaded or unloaded κaAPCs and CBs did not induce apoptosis (numbers of viable cells remained at 90%-100%) regardless of the bead/CTL ratio.

Figure 4.

Elimination of antigen-specific CTLs by κaAPCs is strongly ratio dependent. CTLs were cocultured with unloaded (circles), Mart-1–loaded (squares), and CMVpp65-loaded (triangles) CBs or κaAPCs. Closed symbols represents CTLs cocultured with CBs, whereas open symbols indicate CTLs cocultured with κaAPCs. Different bead-CTL ratios are indicated at the x-axis. Numbers of viable CTLs; (% viable cells = (% treated cells × 100%)/% untreated cells were determined by Annexin V and PI staining 48 hours following initiation of cocultures. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

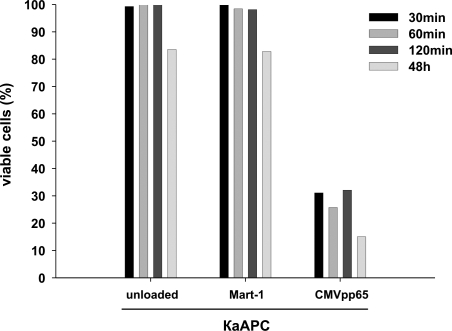

To analyze if a short interaction of κaAPCs with CTLs is sufficient, or if long-term interaction is needed for maximal apoptosis induction, we also characterized the kinetics of the κaAPC-dependent CTL depletion. Antigen-specific CTLs were stimulated with κaAPCs for different coculture periods (Figure 5). Cocultures established for 48 hours served as positive control for maximum depletion. To separate beads from CTLs, beads were magnetically removed from the cocultures at indicated time points. More than 95% of the κaAPCs were removed during this purification step, as confirmed by light microscopy. Following purification, CTLs were cultured for 48 hours, and apoptotic CTLs were determined by FACS analysis. High numbers of apoptotic CTLs could already be observed after a coculture period with CMVpp65κaAPCs for just 30 minutes (VCs, 31%), compared with 15% viable CMVpp65-specific CTLs cocultured with CMVpp65κaAPCs for 48 hours. In contrast, CTL apoptosis was within background levels (VCs, 85%-100%) in all other established cocultures with CMVpp65 peptide–loaded CBs (data not shown) as well as unloaded or non cognate peptide–loaded κaAPCs. These results indicate that even after only a short period of interaction, κaAPCs were able to delete CTLs.

Figure 5.

Elimination of CTLs occurs early during interaction with κaAPCs. CMVpp65-specific CTLs were cocultured with different loaded or unloaded bead preparations (x-axis). At indicated time points (30, 60, and 120 minutes following initiation of cocultures), beads were magnetically removed and CMVpp65-specific CTLs were further incubated. After 48 hours, numbers of viable CTLs, (% viable cells = (% treated cells × 100%)/% untreated cells were determined as described in the experimental protocols. CMVpp65-specific CTLs cocultured for 48 hours with the indicated beads served as positive control.

κaAPCs eliminate CTLs in an antigen-specific manner from T-cell populations with diverse antigen specificities

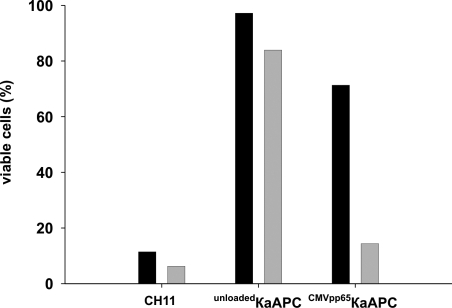

To demonstrate that κaAPCs deplete CTLs in an antigen-specific fashion, additional coculture experiments were performed using a mixture of CTLs with different antigen specificities. For these experiments, an autologous T-cell mixture (Tmix) was established containing PKH67-stained, CMVpp65-specific CTLs and PKH26-labeled, activated Fas+ effector-memory CTLs at a ratio of 1:1. Cells from this Tmix were then cocultured with unloaded or CMVpp65 peptide–loaded κaAPCs or CBs. This experimental set-up allowed us to determine apoptosis in each T-cell population simultaneously. We determined the κaAPC-mediated CTL depletion in both populations by differential gating on PKH67+ CTLs and PKH26+ CTLs. Tmix cocultures with CMVpp65κaAPCs revealed clear differences between both populations (Figure 6). CMVpp65κaAPCs specifically killed cognate CMVpp65–specific CTLs in the Tmix; only 14% of the original CMVpp65 population remained viable. In contrast, non–CMV-specific activated Fas+ effector-memory CTLs were not depleted, and similar to nontreated CTLs, more than 70% of these CTLs remained viable. Considering that both populations were highly apoptosis sensitive when treated with soluble α-FasmAb, our findings demonstrate that the detected differences were due to specific interactions of CMVpp65κaAPCs with CMVpp65-specific CTLs. In addition, cocultures with unloadedκaAPCs or other CBs (data not shown) did not result in significant CTL depletion in any of the populations (VCs, 85%-97%) which further emphasizes that cognate-loaded κaAPCs are capable of depleting activated CTLs in an antigen-specific manner from a mixture of activated T cells with different antigen specificities.

Figure 6.

κaAPCs eliminate CTLs in an antigen-specific fashion. PKH26-labeled activated Fas+ effector-memory CTLs (■) and PKH67-labeled CMVpp65-specific CTLs (▒) from the same donor were mixed to a 1:1 ratio and cocultured with CMVpp65κaAPCs for 48 hours. Control cultures were treated with unloadedκaAPCs or 1 μg/mL of soluble α-Fas IgM (clone CH11). Minimal loss of viable cells was determined in untreated mixed CTL cultures (Tmix). Numbers of viable CTLs, (% viable cells = (% treated cells × 100%)/% untreated cells) for each CTL population of the Tmix are depicted. The illustrating graph is derived from 1 representative experiment out of 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

Antigen-specific elimination of T cells by FasL-expressing APCs has been demonstrated by various investigators in different in vitro and in vivo experimental models using both murine and human cells. Despite promising results indicating the therapeutic potential of FasL-expressing killer APCs as immunoregulatory cells for the treatment of allograft rejection,14–16,30–35 autoimmune disease,13,18,23,36,37 and chronic infections,38,39 there are several significant limitations associated with these approaches related to the cellular nature of the modified APCs. Ultimately, this has limited clinical utilization. There are several limitations. First, transduction with the FasL gene is required to generate killer APCs. Several virus- and nonvirus-based transduction methods have been used; however, all strategies result in different levels of FasL expression depending on the transduction efficiency. Therefore, purification of FasL-expressing APCs is needed to avoid activation of T cells by nontransduced APCs. In addition, production of soluble FasL has been observed in killer APCs, compromising its efficiency due to blockade of the Fas/FasL signaling pathway.5,25 Second, use of primary cells, including DCs, as APCs is time, cost, and labor intensive, and the resulting cell product is highly variable in quality and quantity. In particular, the phenotype of the killer APCs cannot be maintained from donor to donor, resulting in variable functional activity. Third, since killer APCs are also targets of CTLs, the therapeutic potential could be substantially reduced.23 Finally, presentation of new antigens derived from bacteria or viruses as well as viral vectors on the surface of FasL-expressing killer APCs could result in elimination of activated T cells directed against bacterial or viral antigens, resulting in a critical impairment of the protective immune response.

In light of these limitations and based on our previous work24,26 and the work of others,40,41 we generated an artificial killer APC by conjugation of HLA-A2 Ig dimer molecules and an apoptosis-inducing α-Fas IgM mAb onto epoxy-beads, which could then be loaded with different peptides. In contrast to our aAPCs, which express an optimal amount of HLA-A2 Ig and α-CD28 mAb required for efficient T-cell activation, the goal for the κaAPCs was to achieve maximal antigen-specific killing combined with minimal CTL activation. Therefore, it was necessary to carefully titer the amount of HLA-A2 Ig and α-Fas mAb during κaAPC preparation. To evaluate the optimal amount and ratio of HLA-A2 Ig and α-Fas mAb, we found that if more HLA-A2 Ig was coupled to the beads, they would induce antigen-specific activation and consequent expansion of the target cells, while if more α-Fas mAb was coupled to the κaAPCs, they would induce nonspecific killing of all Fas-expressing CTLs. Phenotypic and functional characterization of our current κaAPCs demonstrates deletion of CD8+ T cells in an antigen-specific fashion, which was directly related to the number of κaAPCs present in the cocultures. In addition, κaAPCs selectively eliminated CMVpp65-specific CTLs from mixtures of effector-memory T cells with unknown specificity, specifically reducing the targeted CMV-specific CTL population, while not significantly effecting the viability of the remaining non–CMV-specific CTLs. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the generation and functional characterization of bead-based “off the shelf” κaAPCs that might be of use in modulating T-cell responses in autoimmune and transplantation-related diseases.

In contrast to cell-based killer APCs, κaAPCs do not promote the risk of activation of a T-cell response, or induction of tolerance toward other antigens. Furthermore, κaAPCs are not eliminated by self or paracrine killing due to Fas/FasL signaling, and κaAPCs are not targets of the cytolytic effector functions of CTL. In addition, the ease of the κaAPC system allows one to modify the phenotype through simple peptide exchange, and large numbers of κaAPC with proven activity can be rapidly and reproducibly manufactured. The apoptosis-inducing signal could be modified as well by using other ligands or α receptor mAb of the TNFR superfamily.42,43 Also, κaAPCs do not produce FasL. Cell-based killer APCs that express only minimal or even no FasL might initiate intracellular signaling cascades that ultimately lead to priming and expansion of antigen-specific T cells. The fact that this cannot happen using our system highlights the great advantage of a bead-based κaAPC.

Stimulation with either κaAPCs or CBs did not result in CD107a expression, indicating that the interaction with CTLs did not lead to complete activation.29 Furthermore, we found that only 30 minutes or less of interaction between CTLs and κaAPCs were required to induce Fas-mediated apoptosis leading to CTL deletion. For technical reasons, we were not able to test shorter intervals of stimulation. Nevertheless, these experiments clearly demonstrate that apoptosis in CTLs was dependent on a combined signal, delivered via the T-cell receptor (TCR) and Fas, which was only provided by κaAPCs loaded with the cognate peptide, and not κaAPCs loaded with an irrelevant peptide or CBs. This could reflect the fact that the beads were made with low amounts of HLA-A2 Ig dimer and/or also did not have any costimulatory complexes. In either event, κaAPCs that delivered simultaneous signals through both the TCR and Fas-receptor rosette into big bead-cell clusters so that one κaAPC may simultaneously induce apoptosis in multiple CTLs. Due to the fact that all experiments are preformed in a static 96-well system, it is not clear if κaAPCs can also induce apoptosis to multiple CTLs through multiple contacts during migration.

Other novel approaches that could complement bead-based κaAPCs have been developed. For example, Tykocinski et al have developed a CTLA-4–FasL fusion molecule that physically and functionally bridges APCs and T cells. Binding of CTLA-4 to B7.1 and B7.2 on the APCs blocks the important costimulatory interaction of CD28 on T cells and B7 on the APCs. At the same time, the FasL molecule binds to the Fas receptor on activated T cells and induces Fas/FasL-mediated T-cell apoptosis. It has been shown that this newly designed molecule, which combines the abilities to block an important costimulatory pathway and to induce apoptosis, can be used to delete alloantigen-specific CTLs in vitro. In addition, it was demonstrated that the CTLA-4–FasL fusion protein is more efficient at T-cell deletion than the separated or combined administration of soluble CTLA-4–Ig and FasL-Ig, again suggesting that the combination of signals is crucial for the observed effect.44

With regard to potential clinical applications, bead-based κaAPCs in contrast to cell-based killer APCs cannot process antigens. This is advantageous in that it avoids the depletion of nonpathogenic T cells and the presentation of viral-vector antigens. However, it could be argued that the inability to process antigen is a limitation of κaAPC functionality. κaAPCs require the identification of relevant antigens for each disease. Currently, there are already several HLA-A2–restricted target antigens relevant for type 1 diabetes45–49 as well as for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)50,51 and multiple sclerosis.52,53 Furthermore, the decoding of the human genome and the application of novel molecular technologies will permit the rapid identification of new auto-antigens in the near future.54 In addition, it has been demonstrated that during the onset phase of an autoimmune disease, only a few autoreactive T-cell clones are activated, and that antigen spreading occurs later during the disease course.55 More importantly, κaAPCs provide the advantage of customizing signals and their strength to most efficiently target pathogenic T cells for immunotherapy. Cell-based approaches do not have this advantage, and furthermore, they may harbor other naturally occurring undesirable signals dependent on the cell scaffold used, which can be excluded when using κaAPCs. In cell-based approaches, gene regulation issues affect signal strength and composition; this is not a concern with κaAPCs. In addition, initial experiments in mice have shown that aAPCs are capable of activating CTLs in vivo (data not shown). Furthermore, when injected intravenously, the beads distribute into all organs analyzed, including spleen, lymph nodes, liver, pancreas, kidney, and lungs (data not shown). Therefore, in vivo application of κaAPCs appears to be a promising treatment strategy during the early phase of an autoimmune disease. The beads currently in use are available in Good Manufacturing Practice grade, and one could envision using other scaffolds such as biodegradable particles or latex, which have already been used in vivo in other clinical settings.56

In summary, we provide proof of concept that CTLs can be depleted in an antigen-specific fashion by bead-based HLA-A2 Ig κaAPCs. The flexibility and versatility of the κaAPC platform enables us not only to modulate the signal strength but also to compose new signal combinations to target other T-cell populations for immunotherapy. Therefore, this study shows proof of principal of a bead-based κaAPC that has the potential to treat T cell–related autoimmune diseases and allograft rejection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in parts by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft KFO146 (A.M., M.F.), Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (M.F.), Department of Defense grant PC 040972 (M.O.), and National Institutes of Health grants RO1 CA108835 and RO1 Ai44129 (J.P.S.).

Footnotes

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.S. designed and performed experiments and wrote the paper; M.F., A.M., J.P.S., and M.O. assisted in designing experiments and writing the paper; and A.Z. and D.H. performed experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian Schütz, University of Regensburg, Department of Internal Medicine I, Franz-Josef-Strauss-Allee 11, 93053 Regensburg, Germany; e-mail: christian.schuetz@klinik.uni-r.de.

References

- 1.Toungouz M, Donckier V, Goldman M. Tolerance induction in clinical transplantation: the pending questions. Transplantation. 2003;75:58S–60S. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000067955.60639.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lechler RI, Sykes M, Thomson AW, Turka LA. Organ transplantation: how much of the promise has been realized? Nat Med. 2005;11:605–613. doi: 10.1038/nm1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson G, Moore NC, Owen JJ, Jenkinson EJ. Cellular interactions in thymocyte development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:73–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krammer PH. CD95's deadly mission in the immune system. Nature. 2000;407:789–795. doi: 10.1038/35037728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Askenasy N, Yolcu ES, Yaniv I, Shirwan H. Induction of tolerance using Fas ligand: a double-edged immunomodulator. Blood. 2005;105:1396–1404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluestone JA, Tang Q. How do CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control autoimmunity? Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munz C, Steinman RM, Fujii S. Dendritic cell maturation by innate lymphocytes: coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:203–207. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper MD, Alder MN. The evolution of adaptive immune systems. Cell. 2006;124:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strand S, Hofmann WJ, Hug H, et al. Lymphocyte apoptosis induced by CD95 (APO-1/Fas) ligand-expressing tumor cells–a mechanism of immune evasion? Nat Med. 1996;2:1361–1366. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker PR, Saas P, Dietrich PY. Tumor expression of Fas ligand (CD95L) and the consequences. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:564–572. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Tumor counterattack: fact or fiction? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:1127–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsue H, Matsue K, Walters M, et al. Induction of antigen-specific immunosuppression by CD95L cDNA-transfected ‘killer’ dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:930–937. doi: 10.1038/11375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsue H, Matsue K, Kusuhara M, et al. Immunosuppressive properties of CD95L-transduced “killer” hybrids created by fusing donor- and recipient-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98:3465–3472. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusuhara M, Matsue K, Edelbaum D, et al. Killing of naive T cells by CD95L-transfected dendritic cells (DC): in vivo study using killer DC-DC hybrids and CD4(+) T cells from DO11. 10 mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1035–1043. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200204)32:4<1035::AID-IMMU1035>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgantas RW, III, Leong KW, August JT. Antigen-specific induction of peripheral T cell tolerance in vivo by codelivery of DNA vectors encoding antigen and Fas ligand. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:851–858. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min WP, Gorczynski R, Huang XY, et al. Dendritic cells genetically engineered to express Fas ligand induce donor-specific hyporesponsiveness and prolong allograft survival. J Immunol. 2000;164:161–167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang HG, Liu D, Heike Y, et al. Induction of specific T-cell tolerance by adenovirus-transfected, Fas ligand-producing antigen presenting cells. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:1045–1049. doi: 10.1038/3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buonocore S, Paulart F, Le Moine A, et al. Dendritic cells overexpressing CD95 (Fas) ligand elicit vigorous allospecific T-cell responses in vivo. Blood. 2003;101:1469–1476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buonocore S, Flamand V, Claessen N, et al. Dendritic cells overexpressing Fas-ligand induce pulmonary vasculitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss G, Osen W, Knape I, et al. Membrane-bound CD95 ligand expressed on human antigen-presenting cells prevents alloantigen-specific T cell response without impairment of viral and third-party T cell immunity. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:480–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermans IF, Ritchie DS, Yang J, Roberts JM, Ronchese F. CD8+ T cell-dependent elimination of dendritic cells in vivo limits the induction of antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:3095–3101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oelke M, Maus MV, Didiano D, et al. Ex vivo induction and expansion of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells by HLA-Ig-coated artificial antigen-presenting cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoves S, Krause SW, Halbritter D, et al. Mature but not immature Fas ligand (CD95L)-transduced human monocyte-derived dendritic cells are protected from Fas-mediated apoptosis and can be used as killer APC. J Immunol. 2003;170:5406–5413. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoves S, Krause SW, Herfarth H, et al. Elimination of activated but not resting primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by Fas ligand (FasL/CD95L)-expressing Killer-dendritic cells. Immunobiology. 2004;208:463–475. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer K, Mackensen A. The flow cytometric PKH-26 assay for the determination of T-cell mediated cytotoxic activity. Methods. 2003;31:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer K, Voelkl S, Berger J, et al. Antigen recognition induces phosphatidylserine exposure on the cell surface of human CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006;108:4094–4101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, et al. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;281:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dulat HJ, von Grumbkow C, Baars W, et al. Down-regulation of human alloimmune responses by genetically engineered expression of CD95 ligand on stimulatory and target cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2217–2226. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2217::aid-immu2217>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whartenby KA, Straley EE, Kim H, et al. Transduction of donor hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells with Fas ligand enhanced short-term engraftment in a murine model of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:3147–3154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elhalel MD, Huang JH, Schmidt W, Rachmilewitz J, Tykocinski ML. CTLA-4: FasL induces alloantigen-specific hyporesponsiveness. J Immunol. 2003;170:5842–5850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yolcu ES, Askenasy N, Singh NP, Cherradi SE, Shirwan H. Cell membrane modification for rapid display of proteins as a novel means of immunomodulation: FasL-decorated cells prevent islet graft rejection. Immunity. 2002;17:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yagita H, Seino K, Kayagaki N, Okumura K. CD95 ligand in graft rejection. Nature. 1996;379:682. doi: 10.1038/379682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau HT, Yu M, Fontana A, Stoeckert CJ., Jr Prevention of islet allograft rejection with engineered myoblasts expressing FasL in mice. Science. 1996;273:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleck M, Zhang HG, Kern ER, et al. Treatment of chronic sialadenitis in a murine model of Sjogren's syndrome by local fasL gene transfer. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:964–973. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<964::AID-ANR154>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu B, Wu JM, Miagkov A, et al. Specific immunotherapy by genetically engineered APCs: the “guided missile” strategy. J Immunol. 2001;166:4773–4779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang HG, Fleck M, Kern ER, et al. Antigen presenting cells expressing Fas ligand down-modulate chronic inflammatory disease in Fas ligand-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:813–821. doi: 10.1172/JCI8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfe T, Asseman C, Hughes A, et al. Reduction of antiviral CD8 lymphocytes in vivo with dendritic cells expressing Fas ligand-increased survival of viral (lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus) central nervous system infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:4867–4872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan RR, Wong P, McDevitt MR, et al. Targeted deletion of T-cell clones using alpha-emitting suicide MHC tetramers. Blood. 2004;104:2397–2402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hess PR, Barnes C, Woolard MD, et al. Selective deletion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by MHC class I tetramers coupled to the type I ribosome-inactivating protein, saporin. Blood. 2007;109:3300–3307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen HM, Pervaiz S. TNF receptor superfamily-induced cell death: redox-dependent execution. FASEB J. 2006;20:1589–1598. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5603rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang JH, Tykocinski ML. CTLA-4-Fas ligand functions as a trans signal converter protein in bridging antigen-presenting cells and T cells. Int Immunol. 2001;13:529–539. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Endert P, Hassainya Y, Lindo V, et al. HLA class I epitope discovery in type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1079:190–197. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toma A, Haddouk S, Briand JP, et al. Recognition of a subregion of human proinsulin by class I-restricted T cells in type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10581–10586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinkse GG, Tysma OH, Bergen CA, et al. Autoreactive CD8 T cells associated with beta cell destruction in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18425–18430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508621102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panagiotopoulos C, Qin H, Tan R, Verchere CB. Identification of a beta-cell-specific HLA class I restricted epitope in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:2647–2651. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panina-Bordignon P, Lang R, van Endert PM, et al. Cytotoxic T cells specific for glutamic acid decarboxylase in autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1923–1927. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.den Haan JM, Meadows LM, Wang W, et al. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science. 1998;279:1054–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rufer N, Wolpert E, Helg C, et al. HA-1 and the SMCY-derived peptide FIDSYICQV (H-Y) are immunodominant minor histocompatibility antigens after bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:910–916. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niland B, Banki K, Biddison WE, Perl A. CD8+ T cell-mediated HLA-A*0201-restricted cytotoxicity to transaldolase peptide 168–176 in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2005;175:8365–8378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zang YC, Li S, Rivera VM, et al. Increased CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses to myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2004;172:5120–5127. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hershko AY, Naparstek Y. Autoimmunity in the era of genomics and proteomics. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanderlugt CL, Miller SD. Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nri724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldberg J, Shrikant P, Mescher MF. In vivo augmentation of tumor-specific CTL responses by class I/peptide antigen complexes on microspheres (large multivalent immunogen). J Immunol. 2003;170:228–235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.