Abstract

Oxalate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.2) catalyses the conversion of oxalate into carbon dioxide and formate. It requires manganese and, uniquely, dioxygen for catalysis. It forms a homohexamer and each subunit contains two similar, but distinct, manganese sites termed sites 1 and 2. There is kinetic evidence that only site 1 is catalytically active and that site 2 is purely structural. However, the kinetics of enzymes with mutations in site 2 are often ambiguous and all mutant kinetics have been interpreted without structural information. Nine new site-directed mutants have been generated and four mutant crystal structures have now been solved. Most mutants targeted (i) the flexibility (T165P), (ii) favoured conformation (S161A, S164A, D297A or H299A) or (iii) presence (Δ162–163 or Δ162–164) of a lid associated with site 1. The kinetics of these mutants were consistent with only site 1 being catalytically active. This was particularly striking with D297A and H299A because they disrupted hydrogen bonds between the lid and a neighbouring subunit only when in the open conformation and were distant from site 2. These observations also provided the first evidence that the flexibility and stability of lid conformations are important in catalysis. The deletion of the lid to mimic the plant oxalate oxidase led to a loss of decarboxylase activity, but only a slight elevation in the oxalate oxidase side reaction, implying other changes are required to afford a reaction specificity switch. The four mutant crystal structures (R92A, E162A, Δ162–163 and S161A) strongly support the hypothesis that site 2 is purely structural.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, catalytically active site, manganese, oxalate decarboxylase, oxalate oxidase, protein crystallography

Abbreviations: ABTS, 2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); DTT, dithiothreitol

INTRODUCTION

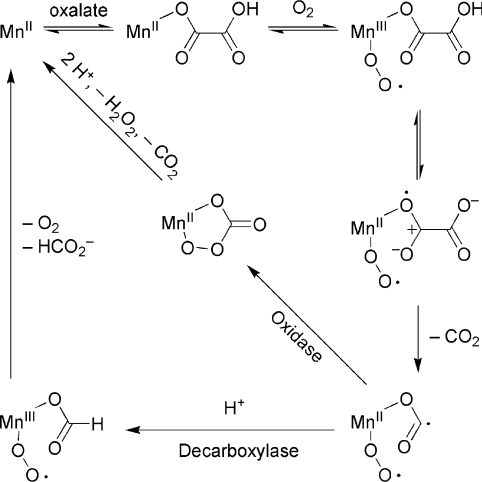

Oxalate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.2) catalyses the conversion of oxalate into carbon dioxide and formate in a reaction that involves the cleavage of a relatively inert C–C bond [1,2]. The enzyme, coded by the oxdC gene in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, is thought to be involved in the response to acid pH stress [3] and a recent study has reported that it is unexpectedly targeted to the cell wall [4]. It requires Mn(II) and, uniquely, dioxygen for catalysis [5]. A novel free-radical catalytic cycle for this enzyme, based on the requirement for manganese and dioxygen, was proposed [5] and has since been elaborated with additional kinetic [6,7], spectroscopic [8,9], theoretical [10], mutagenic and structural [11,12] information (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Proposed divergent catalytic cycles of oxalate decarboxylase and oxalate oxidase.

See the text for evidence for these cycles.

Properties shared with oxalate oxidases, including the requirement for manganese [13], shared membership of the cupin superfamily of proteins [14], and a predicted similar active-site architecture [13,15] led to the proposal of a similar [13] but divergent [5] catalytic mechanism that has since had further input from structural [16,17], spectroscopic [18] and theoretical [19] studies (Scheme 1). When oxalate oxidase was first discovered to contain manganese, a catalytic cycle based on Mn(III) and well-known chemistry was considered unlikely since the resting state of the enzyme is predominantly in the Mn(II) oxidation state [13]. However, a recent study has provided evidence that the Mn(III) form of the plant enzyme could be the catalytically active form [20]. Whatever the case, a decarboxylase catalytic cycle based on Mn(III) would not require dioxygen in any obvious way, so would be unlikely as argued previously [5].

Both enzymes co-ordinate mononuclear Mn(II) ions with one glutamic acid residue and three histidine residues [11,16], but the outcome of catalysis is expected to be dictated by the protonation of a formyl radical intermediate in only the decarboxylase reaction (perhaps together with the initial oxidation state of the manganese). Reaction specificity is not absolute because both enzymes have small amounts of the other respective activity [5,21]. These oxalate-degrading enzymes have potential commercial applications for diagnostics, gene therapy, bioremediation and crop improvement [22,23].

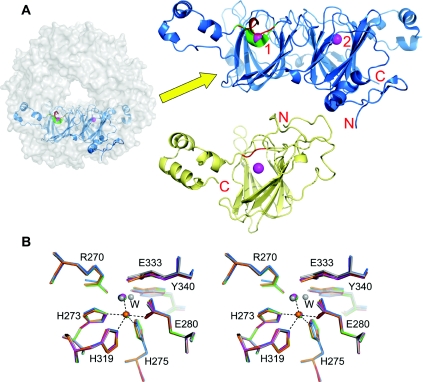

B. subtilis oxalate decarboxylase has two manganese-binding sites (Figure 1A; [11,12]). Structural evidence that site 1 is the catalytic site includes the presence of formate bound to site 1 in one crystal structure [11] (together with spectroscopic support [9]), the presence of a suitable proton donor, Glu162, on a lid that can isolate site 1 from solvent [12] and the apparent solvent inaccessibility of site 2 in both known structures. Kinetic evidence includes the expected kinetic isotope effects and loss of activities when site 1 residues are mutated [7,12]. However, assumptions had to be made regarding the structural consequences of the mutations on activity. In addition, many site 2 mutants gave ambiguous results because they were severely compromised [11,12], precluding reliable kinetic isotope effect measurements and therefore the unambiguous assignment of site 2 as purely structural. Furthermore, the replacement of Glu162 was expected to result in an enzyme that had no decarboxylase activity but substantial oxidase activity [12]. Although a reaction specificity switch was reported with an E162Q mutant [7], it was modest (0.56 unit·mg−1 of oxidase activity compared with a wild-type activity decarboxylase of 79 units·mg−1), not observed in our laboratory [12] and not observed with any other replacement of Glu162. Finally, an approach that has not yet been explored is the mutation of the lid directed towards altering the flexibility and conformational stability of the active-site lid.

Figure 1. Structure of the wild-type oxalate decarboxylase and superposition of mutant site 2 structures.

(A) Location of the OxdC subunit (shown in blue cartoon representation) within the context of the hexamer (depicted as a semitransparent grey surface). The magenta spheres represent the manganese ions at sites 1 and 2 (labelled in the enlarged view). The lid region (residues 160–166) is highlighted in red for the open (PDB code 1J58; [11]) and green for the closed (PDB code 1UW8; [12]) conformations. Access to site 1 is via the channel that runs through the centre of the hexamer. For comparison, the plant oxalate oxidase monomer structure (PDB code 1FI2; [16]) is also shown below (pale yellow cartoon) in the same relative orientation as the OxdC N-terminal domain, with the equivalent of the lid region highlighted in red (residues 158–160). (B) Stereoview showing key residues and water molecules around site 2 for all six known oxalate decarboxylase structures. Green, wild-type closed (PDB code 1UW8; [12]); grey, wild-type open (PDB code 1J58; [11]); blue, R92A; orange, E162A; red, Δ162–163; and magenta, S161A. The dotted lines indicate interactions between the manganese, its protein ligands, and water molecules in the closed structure. The ‘W’ indicates the second water molecule that is only seen in the open structure. The Figures were generated using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

The present paper describes structural and kinetic evidence, with site-directed mutants of B. subtilis oxalate decarboxylase, that site 1 is indeed the sole catalytically active site, that the flexibility and stability of the conformations of the active-site 1 lid are important in the catalytic cycle and that the conversion of a decarboxylase into an oxidase is not achievable by simply removing the lid with its Glu162 proton donor to mimic the plant oxalate oxidase.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All the materials and biochemicals used in the present study were of the highest grade available and, unless stated otherwise, were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce Coomassie Plus-200 assay. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP4C) was purchased from Biozyme Laboratories (Blaenavon, Gwent, Wales, U.K.). DTT (dithiothreitol) was obtained from Melford Laboratories (Suffolk, U.K.). Metal analysis was performed by Southern Science Laboratories (Lewes, Sussex, U.K.) by using inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy of acid-digested samples. The metal content is quoted after the subtraction of control values obtained with buffer alone. Amino acid analysis of acid-digested protein using ion-exchange ninhydrin chromatography was performed by the University of Cambridge Protein and Nucleic Acid Facility, U.K.

Expression, purification and site-directed mutagenesis of histidine-tagged oxalate decarboxylase

The oxdC gene from B. subtilis strain 168 was inserted into the pET32a vector (Novagen) to give pLB36 as described previously [12]. This construct allowed expression of the C-terminally histidine-tagged protein in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Site-directed mutagenesis of histidine-tagged oxalate decarboxylase was carried out using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), and the DNA sequence of each mutant was verified successfully. Cultures were grown and protein expression was induced with isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside after heat-shock treatment at 42 °C and addition of MnCl2 as described previously [12]. The heat-shock treatment was for either 2 or 20 min as indicated. Cells were harvested and broken to allow the purification of the protein by using HiTrap Chelating HP columns (GE Healthcare) charged with NiCl2 as described previously [12]. Active fractions were pooled and incubated for 1 h on ice with Chelex beads (Bio-Rad) to remove adventitiously bound bivalent metal ions. The samples were then concentrated in the presence of 5 mM DTT and filtered (0.2 μm). Protein was further purified by gel filtration with a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (GE Healthcare) eluted with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5), containing 0.5 M NaCl. Enzyme solutions were then concentrated to >10 mg·ml−1 using Amicon Ultra filters (Millipore) and frozen in aliquots at −80 °C.

Oxalate decarboxylase assay

One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the conversion of 1 μmol of substrate into product per min. Oxalate decarboxylase activity at pH 4.0 was determined using a stopped assay at 26 °C, where the production of formate was coupled with the reduction of NAD by formate dehydrogenase as described previously [5]. Unless otherwise stated, the oxalate decarboxylase reaction mixtures contain 1–150 mM potassium oxalate, air-saturated 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 4.0), 300 μM o-phenylenediamine, 10 μM BSA and enzyme (up to 1.5 mg·ml−1) and were incubated for 10 min. Michaelis–Menten constants and their standard errors were estimated by fitting data by using the Pharmacology-Simple Ligand Binding-One Site Saturation option in SigmaPlot v8.0.

Oxalate oxidase and dye oxidation assays

Oxalate oxidase activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 23 °C using a continuous assay, where the production of H2O2 was coupled with the single-electron oxidation of ABTS [2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] using horseradish peroxidase as described previously [13]. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.0), horseradish peroxidase (25 units; as defined by the supplier), 5 mM ABTS, 20 mM potassium oxalate and enzyme (up to 0.02 mg·ml−1). Assays were performed in at least duplicate. In order to distinguish between oxalate oxidase (i.e. H2O2 production) and direct oxalate-dependent single-electron dye oxidation activities of the enzyme, controls without peroxidase were necessary.

X-ray crystallography

Protein samples were supplemented with 5 mM DTT and 0.5 mM MnCl2 and filtered (0.2 μm) before crystallization by using the hanging-drop vapour diffusion method at 18 °C. The mutant enzymes generally crystallized with 8–15% (v/v) poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.5), with 0–15% xylitol. The conditions for each mutant were then optimized (see Supplementary material at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/407/bj4070397add.htm). The crystals were cryoprotected using a crystallization solution containing 25% (v/v) glycerol in place of an equivalent volume of buffer, and flash-cooled to 100 K for data collection. Diffraction data were collected in-house using a Mar 345-image plate detector (X-ray Research) mounted on a Rigaku RU-H3RHB rotating anode X-ray generator (operated at 50 kV and 100 mA) fitted with Osmic confocal optics and a copper target (Cu Kα; λ=1.542 Å; 1 Å=0.1 nm). Additional X-ray data were recorded at the ESRF (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility; Grenoble, France) on beamline ID14-2 (λ=0.933 Å) by using an ADSC Quantum 4 CCD camera (charge-coupled-device camera). The diffraction data were integrated using MOSFLM [24] and scaled with SCALA [25]. All other downstream data processing and statistical analyses were carried out using programs from the CCP4 software suite [26]. The crystals were essentially isomorphous with those previously obtained [12]. They all belonged to space group R32 with approximate cell parameters of a=b=155 Å and c=122 Å and contained a single monomer per asymmetric unit, giving an estimated solvent content of 62% [27]. Details of the data collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1. The initial co-ordinate sets and starting phases were obtained by rigid body refinement of the 2.0 Å resolution closed structure [12] (PDB code 1UW8) against the new data sets by using the program REFMAC5 [28]. Model building was performed by interactive computer graphics by using the programs O [29] and COOT [30] with reference to SIGMAA-weighted [31] 2mFobs–DFcalc and mFobs–DFcalc Fourier electron density maps (where m is figure-of-merit and D is estimated co-ordinate error). Positional and thermal parameters of the model were subsequently refined using REFMAC5. The electron density maps confirmed the presence of each expected mutation. A summary of the model contents and geometrical parameters of the final structures is given in Table 1. To compare the structures of the two manganese-binding sites, each was independently superposed on the closed structure on the basis of the Cα positions of the four amino acids providing ligands to the manganese.

Table 1. Summary of X-ray data and model parameters for oxalate decarboxylase mutants.

rmsd, Root mean square deviation.

| Variant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R92A | E162A | Δ162–163 | S161A | |

| Data collection | ||||

| Radiation source | RU-H3RHB | RU-H3RHB | ESRF ID14-2 | RU-H3RHB |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.542 | 1.542 | 0.933 | 1.542 |

| Cell parameters (Å) | a=b=154.5 | a=b=154.7 | a=b=154.9 | a=b=154.7 |

| c=122.3 | c=122.1 | c=123.3 | c=121.9 | |

| Resolution range* (Å) | 28.04–2.80 (2.95–2.80) | 28.04–3.10 (3.27–3.10) | 58.93–2.00 (2.11–2.00) | 31.72–2.10 (2.21–2.10) |

| Unique reflections | 13947 | 10285 | 38270 | 32697 |

| Completeness* (%) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.5 (99.9) | 99.9 (99.1) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Multiplicity | 7.7 (7.6) | 5.9 (5.9) | 8.9 (7.0) | 7.8 (7.3) |

| Rmerge*† | 0.156 (0.352) | 0.152 (0.283) | 0.098 (0.293) | 0.140 (0.375) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉* | 13.4 (6.2) | 9.8 (6.3) | 22.2 (5.6) | 15.3 (5.9) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Rcryst‡ (95% of data; %) | 13.4 | 16.3 | 12.8 | 13.8 |

| Rfree‡ (5% of data; %) | 21.1 | 21.9 | 16.6 | 18.3 |

| DPI§ (based on Rfree; Å) | 0.297 | 0.383 | 0.103 | 0.130 |

| Ramachandran plot∥ (%) | 86.7 | 87.3 | 89.1 | 88.6 |

| rmsd bond distances (Å) | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.015 |

| rmsd bond angles (°) | 1.612 | 1.504 | 1.499 | 1.438 |

| Contents of model | ||||

| Protein residues | 377 | 377 | 375 | 377 |

| Water molecules | 215 | 0 | 411 | 412 |

| Manganese ions | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Other ligands¶ | − | − | 1×chloride | 1×formate |

| PDB accession code | 2UY8 | 2UY9 | 2UYA | 2UYB |

* The values in parentheses indicate the values for the outer resolution shell.

† Rmerge=ΣhΣl|Ihl–〈Ih〉|/ΣhΣl〈Ih〉, where Il is the lth observation of reflection h and 〈Ih〉 is the weighted average intensity for all observations l of reflection h.

‡ The R factors Rcryst and Rfree are calculated as follows: R=Σ(|Fobs–Fcalc|)/Σ|Fobs|×100, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes respectively.

§ Diffraction-component precision index [34] (an estimate of the overall co-ordinate errors calculated in REFMAC5 [28]).

∥ Residues with most favoured Φ/Ψ angles as calculated using PROCHECK [35].

¶ Not including buffer or cryoprotectant molecules that are remote from the manganese sites.

EPR spectroscopy

X-band EPR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker ELEXSYS 500 spectrometer with an ER049X SuperX microwave bridge and an SHQ cavity. Low-temperature experiments were performed using an Oxford Instruments ESR-900 cryostat and ITC3 temperature controller. Conditions were adjusted to ensure non-saturation of signals. Spectra were obtained with a microwave frequency of 9 GHz and power of 2 mW at 30 K.

Molecular modelling

The dominant conformation of the lid of the T165P mutant was estimated using Swiss-PdbViewer v3.6b3 [32]. The feasibility of disulfide bond formation in double mutants of oxalate decarboxylase was modelled on the basis of the open and closed structures (PDB codes 1J58 and 1UW8) [11,12] by using this application.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure of and ligand binding to the R92A mutant

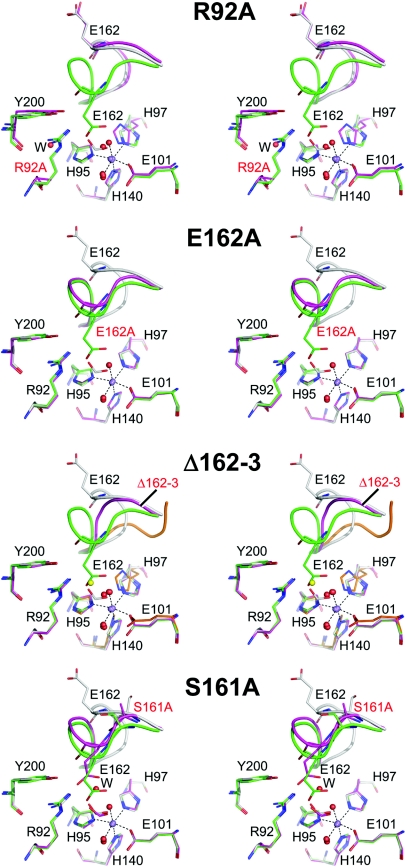

We have previously shown that the R92A mutant lacks both oxalate decarboxylase and oxalate oxidase activities (Table 2; [12]). This had been rationalized as the requirement of Arg92 to bind the substrate and/or stabilize catalytic intermediates [12], as supported by recent kinetic isotope effect measurements [7]. It was important to obtain structural information in order to rule out any unexpected consequences of this mutation, especially at site 2. The crystal structure of the R92A mutant was obtained at 2.8 Å resolution (Figure 2). The conformation of the main chain at amino acid 92 was unchanged. At least one water molecule occupied the space in the mutant structure that the guanidinium group of the Arg92 side chain took up in the wild-type structures [11,12]. The site 1 lid was in a conformation closely similar to that of the open structure. This might have been due to the inability of Glu162 to form a hydrogen bond with Arg92 in the closed conformation of this mutant. Formate, which was added to the crystallization solution, was not observed bound to the site 1 manganese ion but two water molecules were. The manganese ion was slightly displaced (∼0.5 Å compared with the closed and open wild-type structures) towards the core of the protein. This was accompanied by a shift in the position of His97, including its main chain atoms, together with a 180° flip of the imidazole ring to maintain its co-ordination with the metal ion. Incidentally, this flipped conformation resembles that of the equivalent residue in the plant oxalate oxidase structure [16], where there is an asparagine residue in the equivalent position of Arg92. Site 2 (Figure 1B) was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type closed structure [12].

Table 2. Activities of oxalate decarboxylase mutants prepared with the short heat-shock protocol*.

n.d., Not determined.

| Oxalate decarboxylase | Specific activity† (unit·mg−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant | Vmax† (unit·mg−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km† (M−1·s−1) | Oxalate oxidase | Dye oxidation |

| Wild-type‡ | 21.0±1.2 (100) | 16.4±3.4 | 950±200 (100) | 0.03 (100) | 0.09 (100) |

| Site 1 R92A‡§ | 0∥ | n.d. | n.d. | 0¶ | 0.05 (56) |

| Site 1 R92K‡ | 0.195±0.008 (1) | 1.9±0.5 | 76±20 (8) | 0¶ | 0.05 (56) |

| Site 1 E162A‡§ | 0∥ | n.d. | n.d. | 0.02 (67) | 0.11 (122) |

| Site 1 E162Q‡ | 0.230±0.014 (1) | 13.5±2.7 | 13±3 (1) | 0.03 (100) | 0.21 (233) |

| Site 1 Δ162–163§ | 0.213±0.015 (1) | 2.3±0.9 | 69±27 (7) | 0.08 (247) | 0.08 (91) |

| Site 2 R270A‡ | 0.263±0.010 (1) | 8.0±1.4 | 24±4 (3) | 0¶ | 0.06 (67) |

| Site 2 R270K‡ | 0.554±0.018 (3) | 1.14±0.25 | 361±80 (38) | 0¶ | 0.07 (78) |

| Site 2 E333A‡ | 1.29±0.05 (6) | 4.1±0.8 | 235±50 (25) | 0.02 (50) | 0.03 (33) |

| Site 2 E333Q‡ | 0∥ | n.d. | n.d. | 0¶ | 0.06 (67) |

* Recombinant oxalate decarboxylase enzymes were expressed in E. coli with a 2 min 42 °C heat shock prior to induction.

† Values in parentheses indicate percentage compared with wild-type enzyme.

‡ Published previously [12], but original data have since been re-analysed to provide estimates of standard errors as described in the Experimental section.

§ Mutants whose structures are described herein are highlighted in boldface.

∥ Detection limit was 0.03 unit·mg−1.

¶ Detection limit was 0.01 unit·mg−1.

Figure 2. Structures of oxalate decarboxylase site 1 mutants.

Stereoviews showing key residues and ligands (i.e. water molecules, formate or chloride) around site 1 and the lid region. In each case, the wild-type open (PDB code 1J58; [11]) and closed (PDB code 1UW8; [12]) structures are shown for reference with carbons coloured grey and green respectively, and the mutant structures (R92A, E162A, Δ162–163 and S161A) are depicted with magenta carbon atoms. The main-chain backbones of the lid regions (residues 160–166 in oxalate decarboxylase) are shown in ribbon representation. The dotted lines indicate interactions between the manganese, its protein ligands, and water molecules in the closed structure. In the R92A mutant structure, ‘W’ indicates the water molecule that partially fills the space occupied by the guanidinium group of the wild-type side chain. In the Δ162–163 mutant structure, a chloride ion is shown in yellow. The equivalent region of the plant oxalate oxidase is shown with orange carbon atoms for comparison with the Δ162–163 mutant structure. In the S161A mutant, ‘W’ indicates the water molecule adjacent to Glu162, formate and Oγ of Thr165 (results not shown) in this structure. The Figures were generated using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

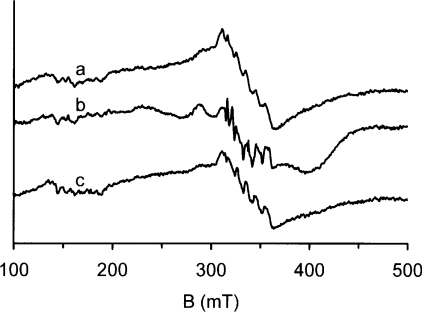

The lack of activity of this mutant could have been due to a lack of turnover or simply the lack of binding of oxalate. Indeed, formate was not bound in the crystal of the mutant despite its addition to the crystallization conditions and its presence in the wild-type open structure [11]. However, the manganese EPR spectrum of the anaerobic enzyme in frozen solution changed in the presence of either formate or oxalate (Figure 3). The spectral changes were qualitatively similar to those observed previously with the wild-type enzyme [33], indicating similar modes of binding to site 1 despite the mutation. It would therefore appear that a lack of catalysis rather than a lack of binding was primarily responsible for the poor activity of this mutant. These results are consistent with site 1 being the only catalytic site and that Arg92 is essential for activity.

Figure 3. X-band EPR anaerobic spectra of the R92A oxalate decarboxylase mutant in the presence of oxalate or formate.

The anaerobic samples contained mutant protein (80 μM), 50 mM citrate (pH 4.0), 20% glycerol and 200 mM NaCl with (a) no additive, (b) 200 mM formate or (c) 200 mM oxalate.

Structure of the E162A mutant

We have previously shown that the E162A mutant possesses no oxalate decarboxylase activity but retains most of its oxalate oxidase side activity (Table 2; [12]). It has been suggested that this provides evidence that Glu162 is the proton donor required to complete the decarboxylase reaction [12]. Again, this was on the assumption that the structure of site 2 was unchanged. The structure of the E162A mutant was determined to 3.1 Å resolution. In this case, the lid was in an essentially closed conformation (Figure 2), perhaps because of the loss of extensive hydrogen-bonding interactions in the open state involving Glu162 [11]. Unfortunately, the results did not permit solvent or other ligands to be modelled with confidence, although we assume that there was no formate bound to site 1, as was the case with the closed form of the wild-type enzyme [12]. No changes were apparent in site 2 (Figure 1B), consistent with Glu162 being the proton donor.

We have previously shown that the E162Q mutant exhibits only 1% of the decarboxylase activity of the wild-type enzyme (Table 2; [12]). A recent report presented evidence for an additional modest increase in oxalate oxidase activity [7], when the enzyme was purified and activity was determined using alternative methods. We have obtained crystals of this mutant that were isomorphous with those of the wild-type with cell parameters of a=b=155.1 Å and c=121.3 Å, indicating that the overall fold and oligomerization state of the protein were unchanged. However, the crystals diffracted weakly, yielding a very poor data set to ∼4 Å resolution (results not shown), such that the structure could not be determined with confidence.

Additional mutations of Glu162 or Glu333

We have previously shown that the replacement of Glu162 near site 1 with either alanine or glutamine results in a dramatic lowering of decarboxylase Vmax (Table 2; [12]). The equivalent mutations in site 2 of Glu333 also lowered the Vmax substantially (Table 2; [12]). What was not clear, however, was the reason why such mutations at site 2 should have such a significant effect if site 1 were responsible for decarboxylase activity.

In order to probe this further, each of these glutamine residues was replaced by aspartic acid. These mutants (Table 3) were expressed in E. coli using a heat shock for 20 min at 42 °C prior to induction (similar to a method reported by others [6]), rather than 2 min as had been used for the enzymes described in Table 2 [12]. This new protocol gave a wild-type enzyme preparation with an improved specific activity. This new protocol was therefore used for all new mutants (Table 3) unless indicated otherwise.

Table 3. Activities of oxalate decarboxylase site 1 mutants prepared with the long heat-shock protocol*.

n.d., Not determined.

| Oxalate decarboxylase | Specific activity† (unit·mg−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant | Vmax† (unit·mg−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km† (M−1·s−1) | Oxalate oxidase | Dye oxidation |

| Wild-type | 94.9±2.3 (100) | 6.6±0.6 | 10670±960 (100) | 0.04 (100) | 0.45 (100) |

| Site 1 E162D | 27.6±1.9 (29) | 17.4±3.9 | 1180±280 (11) | 0.02 (34) | 0.04 (9) |

| Site 2 E333D | 0.85±0.08 (1) | 6.3±2.3 | 101±39 (1) | 0.03 (67) | 0.12 (26) |

| Site 1 Δ162–164 | 0‡ | n.d. | n.d. | 0.12 (304) | 0.06 (13) |

| Site 1 T165P | 2.90±0.37 (3) | 25±9 | 85±33 (1) | 0.01 (20) | 0.04 (8) |

| Site 1 S161A§ | 14.3±1.3 (15) | 71±14 | 149±32 (1) | ≤0.01 (≤12) | 0.03 (7) |

| Site 1 S164A | 13.8±0.9 (15) | 31±5 | 332±60 (3) | ≤0.01 (≤12) | 0.03 (7) |

| Site 1 D297A | 47.3±2.5 (50) | 11.2±2.3 | 3150±660 (30) | 0.12 (320) | 0.40 (89) |

| Site 1 H299A | 46.3±2.5 (49) | 11.6±2.2 | 2960±590 (28) | 0.01 (31) | 0.06 (14) |

* Recombinant oxalate decarboxylase enzymes were expressed in E. coli with a 20 min 42 °C heat shock prior to induction.

† Values in parentheses indicate percentage compared with wild-type enzyme.

‡ Detection limit was 0.03 unit·mg−1.

§ Mutants whose structures are described herein are highlighted in boldface.

The E162D mutant retained 29% of the decarboxylase activity. Such changes were not unexpected because the aspartic acid side chain could still function as the proton donor in the decarboxylase reaction, but less efficiently due to its inevitably different position relative to the active site. It was surprising that the E333D mutant was much more severely affected, with the retention of only 1% of the Vmax of the wild-type enzyme, consistent with a recent report [7]. It must be noted, however, that this mutant gave two orders of magnitude lower yields of purified soluble protein compared with the wild-type and was the only mutant to do so in this laboratory. This implied that the kinetic results might not have reflected the true catalytic properties of this mutant. Indeed, gel filtration and dynamic light scattering revealed an unusual ability of this mutant to exist as a trimer and an aggregate in addition to the normal hexamer. The trimer exhibited a specific activity of approximately half that of the hexamer. A recent report described a similar oligomeric distribution with this mutant and its tendency to lose manganese [7]. It would therefore appear that this residue has an important role, either directly or indirectly, in both oligomerization and metal affinity. One possible reason is that a Glu333 carboxylate O atom in the wild-type enzyme is within ∼2.8 Å of the Nε atom of Arg270. This close interaction would presumably not be possible in the E333D mutant and such a buried and unfulfilled salt bridge could be disruptive.

Deletion of the lid

As described above, the replacement of the Glu162 residue in the oxalate decarboxylase site 1 lid with alanine or glutamine residue dramatically lowers activity (Table 2; [12]). If this were due to the loss of the active-site proton donor for the decarboxylase reaction, one might have expected that the enzyme would have undergone a complete switch to an oxalate oxidase, but it had not. When the structures of the bacterial oxalate decarboxylase and the plant oxalate oxidase were superposed, it was apparent that the site 1 lid, including its glutamic acid residue, was absent from the oxidase [12]. Such a structural alignment indicated that the loop is two or more probably three amino acids shorter in the oxidase, preventing formation of the lid (Figures 1A and 2 and Supplementary material).

In order to test whether the absence of the lid was a prerequisite for oxidase activity, as well as the loss of the glutamic acid residue, a deletion mutant was prepared (using the short heat-shock protocol in this case). The loss of the Glu162 and Asn163 residues in the Δ162–163 mutant resulted in a decarboxylase Vmax of 1% and kcat/Km of 7% as expected (Table 2). Its oxidase activity was increased ∼2.5-fold. While this approach was somewhat successful, the oxalate oxidase Vmax of the mutant was still two orders of magnitude less than that of the plant oxidase [13].

The structure of this Δ162–163 mutant was solved to 2.0 Å. The lid took up a well-ordered conformation and, due to its small size, site 1 was relatively open as expected (Figure 2). Electron density between one of the water molecules bound to the site 1 manganese ion and Arg92 was best modelled by the introduction of a chloride ion. This site is occupied by a carboxyl O atom of either formate in the open structure [11] or Glu162 in the closed structure [12]. This illustrated the propensity for this site to bind negative charges. Halide ions have been reported to bind to the manganese ion of oxalate oxidase according to EPR spectroscopy [18]. However, in this case, it was suggested that chloride displaced the water molecules directly bound to the metal ion, which was not the situation in the decarboxylase mutant structure. The site 2 structure was again unchanged (Figure 1B).

It was apparent from the comparison of this mutant structure with that of the plant oxalate oxidase [16] that the deletion of two residues from the lid was not enough to remove it completely and that a third amino acid deletion would be required to further open the entrance to site 1. On this basis, a third residue, Ser164, was also deleted to give the Δ162–164 mutant, in order to make sure that the lid was completely removed. This mutant exhibited no detectable decarboxylase activity but a ∼3-fold increase in oxalate oxidase activity compared with wild-type (Table 3). Therefore the removal of a third residue enhanced the effect of removing the first two, but did not result in the complete conversion of a decarboxylase into an efficient oxalate oxidase. Its oxidase activity was also less than that reported for E162Q by others [7].

It is clear that additional mutations are required to afford an efficient conversion by stabilizing intermediates associated with the oxidase catalytic cycle. This could include changing the lining of the site 1 active site to resemble more the plant oxidase [17] or perhaps making multiple changes around site 1 to resemble the predicted structure of a fungal oxidase [21]. Such changes could influence factors such as the affinity of the enzyme for oxygen and perhaps the reduction potential of the manganese ion.

Mutation of the lid affecting flexibility

If site 1 were the only active site, mutations of the site 1 lid, other than that of Glu162, would be expected to interfere with its flexibility and ability to open and close, thus impairing substrate entry, positioning of Glu162 for catalysis, product release and therefore enzyme activity. One way in which the lid flexibility could be limited would be to introduce a proline residue in place of one of the amino acids that undergoes the greatest backbone conformational changes [12]. Molecular modelling identified T165P as being the most promising mutation that would least disrupt the lid while at the same time strongly favouring the closed conformation. This mutant's Vmax and kcat/Km were very low (3 and 1% respectively), as expected (Table 3).

Mutations of the lid affecting hydrogen-bonding in either the closed or open conformations

Of interest was the effect of preventing the formation of hydrogen bonds associated with the lid in one or other of its conformations. The Ser161 side chain forms hydrogen bonds to the Thr44 side chain, Glu67 side chain and Asn163 main chain NH in the closed form [12] but only a water molecule in the open form [11]. One might expect therefore that the closed form of a S161A mutant might be destabilized. The S161A mutant retained 15% of its decarboxylase Vmax (Table 3), indicating that such a modest mutation near site 1 did have a detrimental effect on catalytic activity. Furthermore, the affinity for oxalate was affected more than in any other mutant tested, giving a 10-fold increase in Km and a kcat/Km of only 1%.

The structure of the S161A mutant was solved to 2.1 Å resolution. The lid adopted an essentially closed conformation (Figure 2). This mutant was designed with the destabilization of the closed conformation in mind, so the structure was somewhat surprising. Formate was clearly bound to site 1 in a manner previously seen in the open conformation only [11]; noting that in neither case was formate deliberately added to the crystallization conditions. The side chain of Glu162 was within hydrogen-bonding distance of the formate and Tyr200. These interactions perhaps accounted for the lid being closed. Indeed, this is the first known closed structure with formate bound.

These results may give an insight into the structure of the enzyme when it is poised to protonate the proposed formyl radical intermediate. Glu162 is well positioned to act as the proton donor. However, in this chemical step, the formyl radical would be expected to be in an altered conformation after radical decarboxylation, allowing the proton to be transferred to the formyl carbon atom. Interestingly, the observed formate conformation could resemble that required for the formyl radical of the oxalate oxidase reaction either to form percarbonate or to facilitate electron transfer with manganese-bound oxygen.

There was a water molecule within hydrogen-bonding distance of the formate, Glu162 and Thr165 in the mutant structure. The side chain of Thr165 was in the same conformation as in the open wild-type structure but flipped relative to that in the closed structure (results not shown). The side chain conformation in the mutant structure of an adjacent residue, Gln167, was also more similar to that of the open structure (results not shown). The position taken up by the water molecule is unoccupied in all other structures. One can speculate that this position could be occupied by carbon dioxide after the decarboxylation step and that the Thr165 side chain could flip to modulate the hydrophobicity of this site. The site 2 structure was unchanged (Figure 1B).

The Ser164 residue of the wild-type enzyme makes hydrogen bonds to the Glu99 side chain, the Ser161 main chain NH and a water molecule in the open form [11] and none in the closed form [12]. It would therefore be expected that the open form of the lid of a S164A mutant would be destabilized. Interestingly, the Vmax of this mutant was similar to that of the S161A mutant giving 15% of that of the wild-type enzyme (Table 3). However, the Km of this mutant was less affected, giving a kcat/Km of 3%. The oxalate oxidase activities of the S161A and S164A mutants were much lower than that of the wild-type, indicating that the site 1 lid had some influence on this side reaction too.

Mutations near the lid affecting hydrogen-bonding in the open conformation

In order to better assess whether the lid and the stability of its open conformation are important for catalysis and that site 1 is the only catalytic site, mutations were considered that would have more subtle effects. The Glu162 side chain makes hydrogen bonds to the Asp297 side chain, the His299 side chain, the Thr44 side chain and Thr44 main chain NH when in the open form [11]. These three residues are present on the surface of neighbouring subunits, are remote from site 2 and, in the case of the first two, are not involved in interactions with the lid when in the closed form. It was therefore of interest to establish whether mutations of the first two residues would affect catalytic activity.

Both the D297A and H299A mutants had their decarboxylase Vmax lowered by half with little change in their Km for oxalate (Table 3). This provides compelling evidence that only site 1 is catalytically active. It is not clear why the D297A mutant exhibited one of the highest oxalate oxidase activities of any of the mutants tested, but its absolute value is nevertheless small.

Manganese content of mutant enzymes

Some of the oxalate decarboxylase mutant enzymes were selected for metal analysis using inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (Table 4). What is immediately apparent is that none of the enzymes, including the wild-type, contained the theoretical maximum of two atoms of manganese per subunit. While the method that we used for metal analysis is generally considered to be reliable, protein assays are not necessarily so. We compared the results from the protein assay based on dye binding with amino acid analysis, which is generally considered to be a reliable method for protein determination, and found that they gave indistinguishable results. Therefore the metal contents of enzymes presented in Table 4 can be considered to be good estimates.

Table 4. Manganese content of oxalate decarboxylase mutants.

| Mutant | No. of atoms of Mn/subunit |

|---|---|

| Wild-type | 1.2*, 1.2†, 1.3† |

| Site 1 R92A‡ | 0.8* |

| Site 1 R92K | 0.9* |

| Site 1 E162A‡ | 1.4* |

| Site 1 E162Q | 1.8* |

| Site 2 R270K | 0.7* |

| Site 2 E333A | 1.0* |

| Site 2 E333Q | 0.6* |

* Recombinant enzyme was expressed in E. coli with a 2 min 42 °C heat shock prior to induction.

† Recombinant enzyme was expressed in E. coli with a 20 min 42 °C heat shock prior to induction.

‡ Mutants whose structures are described herein are highlighted in boldface.

There was no correlation between the manganese content of the enzymes and their decarboxylase Vmax (Table 4). For example, although the mutants with the lowest manganese content (R92A and E333Q) possessed no decarboxylase activity, the mutant with the second highest manganese content (E162A) also had no decarboxylase activity. In addition, the mutant with a manganese content closest to two atoms per subunit (E162Q) had only 1% of the decarboxylase Vmax of the wild-type and the most active mutant tested (E333A) had a lower manganese content than the wild-type.

The fact that there were essentially full manganese occupancies for both binding sites in all of the crystal structures (as estimated from temperature factors) shows that the crystals represented a subpopulation of the enzymes in solution. This implies that the protein without full manganese occupancy exhibited a conformational disorder that disfavoured crystallization.

Oxalate-dependent dye oxidation

Oxalate decarboxylase is known to catalyse the oxalate-dependent oxidation of dyes [5]. The exact chemical details of this reaction are not known. There was a similar increase in the decarboxylase Vmax and the dye oxidation rate when the wild-type enzyme was prepared with the longer heat-shock protocol (Tables 2 and 3). The rate of dye oxidation catalysed by the mutants varied between 7 and 233% compared with the wild-type enzyme. There was no obvious correlation between the rate of this side reaction and either the rate of oxalate decarboxylation or oxalate oxidation with the mutants, but the error in determining such small rates might have obscured any correlation.

Summary of structural evidence for the identity of the catalytic site

Evidence for site 1 being the sole or dominant active site has previously been presented on the basis of the kinetics of a limited number of site-specific mutants [12], but assumptions were made regarding their structures. We have now solved the structures of two of these mutants. We have also generated and kinetically characterized another nine mutants and solved the structures of two of them. The structural changes in site 1 of the mutants are consistent with their kinetic properties and the hypothesis that site 1 is the main or sole catalytic centre. In none of the crystal structures described was site 2 in any obvious way disrupted.

There are now a total of six structures of oxalate decarboxylase known. Of these, two have formate bound despite formate not being added to the crystallization conditions. In each case, the formate was bound to the site 1 manganese trans to the His140 ligand. The equivalent co-ordination site in the plant oxalate oxidase is known to be capable of binding the oxalate analogue, glycolate [17]. The presence of the product of the decarboxylase reaction, formate, exclusively in site 1 in two decarboxylase structures adds more weight to the argument that site 1 is the only catalytically active site.

Summary of additional kinetic evidence for the identity of the catalytic site and the importance of lid flexibility and conformational stability in the catalytic cycle

Several mutagenic approaches were taken to lend further support for site 1 being the catalytically active site. These included deletion of much of the lid, the restriction of lid flexibility and the disruption of hydrogen-bonding between the lid and the rest of the protein. All of these mutants led to a loss of decarboxylase activity. In a separate set of experiments (results not shown), preliminary kinetic results with the mutants T44C/S161C and S161C/S164C indicated that it was possible to turn decarboxylase activity on and off by preventing or promoting disulfide formation. Disulfide formation would lead to the lid being locked in the closed conformation according to molecular modelling. Further work on such a redox-controlled switch will be required to develop this approach.

The effect of the mutations of the lid on Vmax are generally easy to rationalize. However, the effects on Km are not so easy to explain. The affinity for oxalate was decreased in most of the new mutants generated. The only side chains of the lid to line site 1 are those of Glu162 and Thr165 and that is when the lid is closed. The implication is that the lid has an important role in substrate affinity, through gating access to site 1 as well as its precise conformation when closed.

The most compelling kinetic evidence that site 1 is most likely the only catalytically active site came from the significant lowering of activity when hydrogen bonds between the open lid and the rest of the protein were disrupted. This also suggests that the open conformation is accessed during the catalytic cycle and that the conformational stability and/or movement of the lid can limit the rate of reaction. It is interesting to note that the Gibbs energy of activation associated with the wild-type Vmax (Table 3) is 62.4 kJ·mol−1, whereas that of the above mutants is 64.2 kJ·mol−1. Thus the ΔΔG‡ is 1.7 kJ·mol−1, which is comparable with the typical strength of a hydrogen bond of 2–6 kJ·mol−1; note that no implication is made that the hydrogen bonds associated with these residues are directly involved in the rate-limiting transition state. Nevertheless, there is clearly a fine balance between the stabilities of the open and closed conformations to allow efficient catalysis.

The lid has to open to allow access of the substrates to site 1 and we have presented the first evidence that the stability of the open conformation is indeed important in catalysis. Partial closure would then be required if Glu162 were the base that abstracted the proton from the bound oxalate when the oxalate radical forms. It certainly would have to close in order for Glu162 to protonate the formyl radical intermediate. The lid would then have to open in order to release the products. Why the lid should isolate the catalytic site from solvent when closed is not clear. It could be that catalysis is more efficient within the closed protein environment for electrostatic reasons, that the free-radical chemistry might be interrupted if other small molecules, such as redox-active dyes like ABTS, have access to reactive catalytic intermediates, that it is important to avoid non-specific protonation of dioxygen when bound to the manganese ion or that the reduction potential of the manganese ion requires modulation during the cycle. However, the plant oxidase does not appear to require a lid to function [16], so perhaps the lid is only essential for the decarboxylase reaction. Further work is required to address these issues.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank Sascha Keller for assistance with crystallographic data collection, Shirley Fairhurst for electron paramagnetic spectroscopy and Peter Sharratt for the amino acid analysis. This work was supported by the BBSRC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council) with a grant (grant number C18140 to V. J. J.), a Committee Studentship (to M. R. B.) and a Core Strategic Grant to the John Innes Centre.

References

- 1.Begley T. P., Ealick S. E. Enzymatic reactions involving novel mechanisms of carbanion stabilization. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svedruzic D., Jonsson S., Toyota C. G., Reinhardt L. A., Ricagno S., Linqvist Y., Richards N. G. J. The enzymes of oxalate metabolism: unexpected structures and mechanisms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:176–192. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanner A., Bornemann S. Bacillus subtilis YvrK is an acid-induced oxalate decarboxylase. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5271–5273. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5271-5273.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antelmann H., Towe S., Albrecht D., Hecker M. The phosphorus source phytate changes the composition of the cell wall proteome in Bacillus subtilis. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:897–903. doi: 10.1021/pr060440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanner A., Bowater L., Fairhurst S. A., Bornemann S. Oxalate decarboxylase requires manganese and dioxygen for activity: overexpression and characterization of Bacillus subtilis YvrK and YoaN. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43627–43634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt L. A., Svedruzic D., Chang C. H., Cleland W. W., Richards N. G. J. Heavy atom isotope effects on the reaction catalyzed by the oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1244–1252. doi: 10.1021/ja0286977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svedruzic D., Liu Y., Reinhardt L. A., Wroclawska E., Cleland W. W., Richards N. G. J. Investigating the roles of putative active site residues in the oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;464:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C. H., Svedruzic D., Ozarowski A., Walker L., Yeagle G., Britt R. D., Angerhofer A., Richards N. G. J. EPR spectroscopic characterization of the manganese center and a free radical in the oxalate decarboxylase reaction: identification of a tyrosyl radical during turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52840–52849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angerhofer A., Moomaw E. W., Garcia-Rubio I., Ozarowski A., Krzystek J., Weber R. T., Richards N. G. J. Multifrequency EPR studies on the Mn(II) centers of oxalate decarboxylase. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:5043–5046. doi: 10.1021/jp0715326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C. H., Richards N. G. J. Intrinsic carbon–carbon bond reactivity at the manganese center of oxalate decarboxylase from density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:994–1007. doi: 10.1021/ct050063d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand R., Dorrestein P. C., Kinsland C., Begley T. P., Ealick S. E. Structure of oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis at 1.75 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7659–7669. doi: 10.1021/bi0200965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Just V. J., Stevenson C. E. M., Bowater L., Tanner A., Lawson D. M., Bornemann S. A closed conformation of Bacillus subtilis oxalate decarboxylase OxdC provides evidence for the true identity of the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19867–19874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Requena L., Bornemann S. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) oxalate oxidase is a manganese-containing enzyme. Biochem. J. 1999;343:185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunwell J. M., Gane P. J. Microbial relatives of seed storage proteins: conservation of motifs in a functionally diverse superfamily of enzymes. J. Mol. Evol. 1998;46:147–154. doi: 10.1007/pl00006289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gane P. J., Dunwell J. M., Warwicker J. Modeling based on the structure of vicilins predicts a histidine cluster in the active site of oxalate oxidase. J. Mol. Evol. 1998;46:488–493. doi: 10.1007/pl00006329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo E. J., Dunwell J. M., Goodenough P. W., Marvier A. C., Pickersgill R. W. Germin is a manganese containing homohexamer with oxalate oxidase and superoxide dismutase activities. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:1036–1040. doi: 10.1038/80954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opaleye O., Rose R. S., Whittaker M. M., Woo E. J., Whittaker J. W., Pickersgill R. W. Structural and spectroscopic studies shed light on the mechanism of oxalate oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6428–6433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittaker M. M., Whittaker J. W. Characterization of recombinant barley oxalate oxidase expressed by Pichia pastoris. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:136–145. doi: 10.1007/s007750100281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borowski T., Bassan A., Richards N. G. J., Siegbahn P. E. M. Catalytic reaction mechanism of oxalate oxidase (germin). A hybrid DFT study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:686–693. doi: 10.1021/ct050041r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittaker M. M., Pan H. Y., Yukl E. T., Whittaker J. W. Burst kinetics and redox transformations of the active site manganese ion in oxalate oxidase: implications for the catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7011–7023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escutia M. R., Bowater L., Edwards A., Bottrill A. R., Burrell M. R., Polanco R., Vicuña R., Bornemann S. Cloning and sequencing of two Ceriporiopsis subvermispora bicupin oxalate oxidase allelic isoforms: implications for the reaction specificity of oxalate oxidases and decarboxylases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:3608–3616. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3608-3616.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutton M. V., Evans C. S. Oxalate production by fungi: its role in pathogenicity and ecology in the soil environment. Can. J. Microbiol. 1996;42:881–895. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunwell J. M., Khuri S., Gane P. J. Microbial relatives of the seed storage proteins of higher plants: conservation of structure and diversification of function during evolution of the cupin superfamily. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:153–179. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.153-179.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie A. G. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews B. W. Solvent content of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Read R. J. Improved Fourier coefficients for maps using phases from partial structures with errors. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1986;42:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guex N., Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthusamy M., Burrell M. R., Thorneley R. N. F., Bornemann S. Real-time monitoring of the oxalate decarboxylase reaction and probing hydrogen exchange in the product, formate, using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10667–10673. doi: 10.1021/bi060460q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruickshank D. W. J. Remarks about protein structure precision. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1999;55:583–601. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskowski R. A., Macarthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.