Abstract

Selenocysteine (Sec)-decoding archaea and eukaryotes employ a unique route of Sec-tRNASec synthesis in which O-phosphoseryl-tRNASec kinase (PSTK) phosphorylates Ser-tRNASec to produce the O-phosphoseryl-tRNASec (Sep-tRNASec) substrate that Sep-tRNA:Sec-tRNA synthase (SepSecS) converts to Sec-tRNASec. This study presents a biochemical characterization of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii PSTK, including kinetics of Sep-tRNASec formation (Km for Ser-tRNASec of 40 nM and ATP of 2.6 mM). PSTK binds both Ser-tRNASec and tRNASec with high affinity (Kd values of 53 nM and 39 nM, respectively). The ATPase activity of PSTK may be activated via an induced fit mechanism in which binding of tRNASec specifically stimulates hydrolysis. Albeit with lower activity than ATP, PSTK utilizes GTP, CTP, UTP and dATP as phosphate-donors. Homology with related kinases allowed prediction of the ATPase active site, comprised of phosphate-binding loop (P-loop), Walker B and RxxxR motifs. Gly14, Lys17, Ser18, Asp41, Arg116 and Arg120 mutations resulted in enzymes with decreased activity highlighting the importance of these conserved motifs in PSTK catalysis both in vivo and in vitro. Phylogenetic analysis of PSTK in the context of its ‘DxTN’ kinase family shows that PSTK co-evolved precisely with SepSecS and indicates the presence of a previously unidentified PSTK in Plasmodium species.

INTRODUCTION

The micronutrient selenium is found in proteins as Sec, a natural amino acid that is cotranslationally inserted into proteins in response to the codon UGA. Sec is formed in a tRNA-dependent transformation of Ser to Sec. In bacteria this is achieved in a single step by selenocysteine synthase, SelA, in the presence of the selenium donor selenophosphate (1). Eukaryotes and archaea add an additional step to Sec-tRNASec formation. Following serylation of tRNASec by seryl-tRNA synthetase (SerRS), PSTK specifically phosphorylates Ser-tRNASec to form Sep-tRNASec (2,3). Recently, the enzyme responsible for Sep-tRNASec to Sec-tRNASec conversion, SepSecS, was uncovered in both mammals and archaea (4,5). While PSTK activity was initially found in rat and rooster liver (6) and in the bovine mammary gland (7), the enzyme was later characterized for bovine liver (8), human (9), mouse (2) and M. jannaschii (3). The enzyme requires both ATP and Mg2+ for activity. PSTK was shown to transfer the γ-phosphate from ATP to Ser-tRNASec, yielding Sep-tRNASec and ADP. A computational search of several archaeal and eukaryotic genomes for a kinase-like gene present only in those organisms containing the Sec insertion machinery identified the pstk gene (2).

Here we present a biochemical characterization of M. jannaschii wild-type PSTK and the identification of the ATP-binding site by in vitro and in vivo analysis of PSTK mutants. A detailed phylogenetic analysis of PSTK in the context of its close relatives from the DxTN kinase family is also presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents

All oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing was carried out by the Keck Foundation Biotechnology Research Laboratory at Yale University. [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmol), l-[U-14C]serine (163 mCi/mmol), and [α-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) were from GE Healthcare.

Cloning, expression and purification of enzymes

M. jannaschii PSTK (MJ1538) was cloned between the Nde I and Xho I restriction sites in the pET20b vector (Novagen) with a C-terminal His6 tag. PSTK-pET20b was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) codon plus (Stratagene). A pre-culture was used to inoculate 800 ml of LB broth with 100 µg/ml of ampicillin, 34 µg/ml chloramphenicol, 5052 solution, and phosphate buffer for autoinduction as described previously (10). The cells were grown for 8 h at 37°C and continued at 15°C for 14–16 h. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mM PMSF. After sonication and centrifugation, the cell lysates were applied to TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech) and purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. The eluted enzymes were dialyzed into 25 mM Hepes–KOH (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl and 50% glycerol. SDS–PAGE electrophoresis followed by staining with Coomassie blue revealed greater than 95% purity. Methanococcus maripaludis SerRS was overexpressed as described above and purified as described previously (11).

Mutagenesis of PSTK active site

Point mutations were introduced into amino acid codons for the P-loop residues Gly14, Lys17, Ser18, Thr19, the Walker B motif residue Asp41, and the RxxxR residues Arg116 and Arg120 with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After verification by DNA sequencing, the plasmids were transformed into BL21(DE3) codon plus cells (Stratagene). The mutant proteins were overexpressed and purified as described above.

tRNA purification

The gene encoding M. maripaludis tRNASec with the preceding sequence of the T7 promoter was cloned into the pUC18 plasmid, and the gene encoding M. maripaludis tRNASerUGA with the preceding sequence of the T7 promoter was cloned into the pUC19 plasmid. Both were expressed in E. coli DH5α. Plasmid DNA was purified using the HISpeed Plasmid Maxi kit (Qiagen). The purified plasmid was digested with BstNI for run-off transcription as described previously (12). The transcript was phenol–chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated and purified by electrophoresis on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The tRNA transcripts were refolded at a concentration of 10 µM by heating for 5 min at 70°C in buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0), followed by addition of 5 mM MgCl2 and immediate cooling on ice (11).

Preparation of labeled tRNA

Refolded transcript was 32P-labeled on the 3′ terminus by using the E. coli CCA-adding enzyme and [α-32P]ATP as described previously with some modification (13). Briefly, 8 µM of tRNASec or tRNASer transcript was incubated with the CCA-adding enzyme and 0.5 µCi/µl [α-32P]ATP for 45 min at room temperature in buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT and 50 µM NaPPi. After phenol/chloroform extraction the sample was passed over a Sephadex G25 Microspin column (Amersham Biosciences) to remove excess ATP.

Preparation of seryl-tRNA

Transcript was aminoacylated in 1× PSTK buffer [50 mM Hepes–KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT] with 1 mM l-Ser (Sigma), 5 mM ATP, 3 µM M. maripaludis SerRS and 5 µM 32P-labeled transcript. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 1 h followed by phenol/chloroform extraction, ethanol precipitation and resuspension in water. The samples were passed a minimum of two times over Sephadex G25 Microspin columns (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with water. Transcript that was used to determine the Km for ATP and used in the NTP preference studies was passed over two to three G25 columns equilibrated with 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl to remove all detectable ATP, followed by one G25 column equilibrated with water. Unlabeled transcripts were aminoacylated in parallel. To check aminoacylation levels, 2 µl aliquots were removed at the start and end of the reactions with labeled tRNA, quenched on ice with 3 µl of 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.0) and 0.66 mg/ml nuclease P1 (Sigma), and incubated at room temperature for 35 min (14,15). To separate Ser-AMP from AMP, 1 µl of quenched, digested sample was spotted on glass polyethyleneimine (PEI) cellulose 20 cm × 20 cm thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (EMD) and developed for 75 min in 100 mM ammonium acetate and 5% acetic acid. The plates were exposed on an imaging plate (FujiFilms) for 16 h, scanned on a Molecular Dynamics Storm 860 PhosphorImager, and quantified using ImageQuant software.

TLC separation of Ser-AMP, AMP and Sep-AMP using TLC

Three assay conditions were utilized to confirm the identities of Ser-AMP, AMP and Sep-AMP after TLC analysis. In 1× PSTK buffer, 1 µM 32P-labeled tRNASec transcript was incubated with 5 mM ATP, 1 mM L-Ser, 600 nM SerRS and 100 nM PSTK for 45 min at 37°C. The reactions were quenched, digested and analyzed by TLC as stated above. The second reaction conditions included 1× PSTK buffer, 2 µM tRNASec transcript, 100 µM [14C]Ser, 5 mM ATP, 1.2 µM SerRS and 200 nM PSTK for 45 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped by phenol/chloroform extraction and put over a G25 column to remove unincorporated [14C]Ser, and 2 µl aliquots (3000 cpm/µl) were digested in 3 µl of 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.0) and 0.66 mg/ml nuclease P1 (Sigma) and analyzed by TLC as above. Lastly, 1 µM Ser-tRNASec or Ser-tRNASer was incubated in 1× PSTK buffer with 1.67 µM γ-[32P]ATP and 100 nM PSTK for 45 min at 37°C. The reactions were immediately put over a G25 column, and 2 µl aliquots were quenched, digested and analyzed by TLC as stated above.

Measurement of tRNA binding to PSTK

The affinity of PSTK for Ser-tRNASec, tRNASec, Ser-tRNASer and tRNASer was measured using the filter-binding method described previously with slight modifications (16,17). 32P-labeled transcript and 32P-labeled and serylated transcript was prepared as stated above. Dissociation constants for each were determined by incubating increasing concentrations of PSTK on ice in 25 µl of binding buffer [50 mM Hepes–KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol] for 15 min after the addition of 5 nM 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec, tRNASec, Ser-tRNASer or tRNASer. Minimal deacylation of Ser-tRNASec and Ser-tRNASer was detected over this time frame under the described conditions. A 96-well vacuum manifold (Hybri-dot 96; Whatman Biometra) was used to spot aliquots of the binding reaction onto the upper nitrocellulose membrane (MF-Membrane Filter; Millipore) and a lower nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham). Prior to use the membranes were pre-washed in RNase-free water and soaked for at least 30 min in binding buffer at 4°C. Aliquots of 7 µl from each binding reaction were spotted in triplicate and washed with 200 µl of ice-cold binding buffer. The levels of radiolabeled tRNA on each filter were quantified by PhosphorImager and then used to determine the ratio of RNAbound to RNAtotal after correction for nonspecific binding (17). The corrected data were plotted as a semilog plot of the fraction of total RNA bound to nitrocellulose versus the log of PSTK concentration, and the resulting plot was fitted to the following equation: [RE] = ([Rtotal] × [E])/(Kd + [E]) using Kaleidagraph v. 3.6 (Synergy Software) (R, RNA; E, enzyme).

Phosphotransferase assay

These assays were carried out in 1× PSTK buffer at 37°C. Unless otherwise noted, 5 mM ATP and 200–600 nM 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec was added. For kinetic parameter determination, initial velocities were measured in triplicate while varying concentration of one substrate and saturating with the other. When determining kinetic parameters with varying Ser-tRNASec concentration, reactions were for 50 s with 2 nM enzyme. When determining kinetic parameters with varying ATP concentration, reactions were for 120 s with 6 nM enzyme. Reaction mixes were preincubated at 37°C and started by addition of enzyme. At each time point, 2 µl aliquots were taken and treated as described above for aminoacylation. The previous TLC conditions described were also used to separate Ser-AMP, AMP and Sep-AMP (Figure 2A). Kaleidagraph v. 3.6 (Synergy Software) was used to calculate the kinetic parameters using nonlinear regression plots of the initial velocity versus substrate concentration (Ser-tRNASec or ATP).

Figure 2.

Kinetics of Sep-tRNASec formation. (A) Representative phosphorimage of Sep-tRNASec formation (Sep-AMP) over time. The reaction was carried out with 2 nM PSTK, 5mM ATP and 300 nM 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec. At the indicated time points reaction aliquots were quenched, digested with nuclease P1, and spotted onto PEI-cellulose TLC plates as in Figure 1A. (B) Representative plot of initial velocity versus Ser-tRNASec concentration (4.7–600 nM) with 2 nM PSTK. Following quantification of the intensities of Ser-[32P]AMP, [32P]AMP and Sep-[32P]AMP using ImageQuant, the concentration of Sep-tRNASec formed at each time point was calculated by dividing the intensity of the Sep-[32P]AMP spot by the total intensity. KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) was used to calculate kinetic parameters by nonlinear regression. Error bars represent the difference of three experiments.

The phosphotransferase assays performed with wild-type PSTK and the PSTK active site mutant enzymes, G14W, K17A, S18A, T19W, D41A, R116A and R120A were either carried out with 10 nM enzyme for 1 min or 100 nM enzyme for 5 min. Aliquots of 2 µl were taken and treated as described above for aminoacylation. The aminoacylated tRNA substrate remained stable over these time periods.

For phosphoryl donor preference determination, the phosphotransferase assays were carried out for 6 min with 6 nM PSTK and either no NTP or 20 mM ultrapure (>99%) NTP (ATP, ITP, GTP, CTP, UTP) (Sigma) or dATP (New England Biolabs). For assays using 20 mM α,β-methyleneadenosine-5′-triphosphate (AMP-CPP) or β,γ-methyleneadenosine-5′-triphosphate (AMP-PCP), 200 nM PSTK was used. Aliquots of 2 µl were taken at time points and quenched, digested and analyzed by TLC as stated previously, except reactions with AMP-CPP and AMP-PCP were digested with 6.6 mg/ml nuclease P1 (Sigma). The kphosphorylation (kphosph) values for Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec conversion were calculated for each phosphoryl donor.

ATPase activity measurement

ATPase activity was determined by measuring the amount of [α-32P]ATP converted to [α-32P]ADP as described before with modifications (18). These assays were carried out in a 5 µl reaction volume including 1× PSTK buffer with 130 nM cold ATP, 100 nM [α-32P]ATP and 200 nM enzyme at 37°C for 45 min. Unless noted otherwise, 1 µM unlabeled Ser-tRNASec was included. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 45 µl ice-cold 55 mM EDTA. One microliter of each reaction mixture was spotted on PEI cellulose TLC plates (EMD) and developed in 1 M LiCl for 60–75 min. After separation, the [α-32P]ATP and [α-32P]ADP spots were quantified by PhosphorImager using ImageQuant software.

Steady-state ATPase activity

The [ATP]-dependent steady state ATPase activity of tRNASec-activated PSTK was measured using the NADH-coupled assay (19,20) at 37°C in 1× PSTK buffer. Decrease of absorbance due to NADH oxidation was monitored at 340 nm (εex = 6220 M−1cm−1) using a Lambda 20 UV/Vis Spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Reactions were initiated by the addition of 200 nM PSTK to a solution containing 1× PSTK buffer, 1 µM tRNASec, 100 U/ml pyruvate kinase, 10 U/ml lactate dehydrogenase, 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.5 mM NADH and ATP ranging from 0 to 25 mM (MgCl2 was increased to 25 mM in the reaction with 25 mM ATP). Background ATP hydrolysis in the absence of PSTK was subtracted from all reactions prior to analysis. Background NADH oxidation in the absence of ATP was minimal. Kaleidagraph v. 3.6 (Synergy Software) was used to calculate the kinetic parameters, kcat and Km using nonlinear regression plots of the initial velocity versus ATP concentration.

Complementation of an E. coli ΔselA strain

M. jannaschii PSTK and the PSTK mutant genes, G14W, K17A, S18A, T19W, D41A, R116A and R120A, were each digested from pET20b with Nde I and Blp I and cloned into the pACYCDuet-1 vector (Novagen). M. jannaschii SepSecS was cloned into pET15b (Novagen) (4). The selA deletion strain JS1 was described previously (4). M. jannaschii PSTK and M. jannaschii SepSecS were transformed into the JS1 strain to serve as a positive control. The following combinations transformed into the strain served as negative controls: M. jannaschii PSTK plus pET15b, pACYCDuet-l plus M. jannaschii SepSecS and pACYCDuet-1 plus pET15b. Each PSTK mutant was transformed into the strain plus M. jannaschii SepSecS. Cell growth and the benzyl viologen test was performed as described previously (4).

Sequence-based structure alignment and modeling

The structures of T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 Pnk) (21,22) and gluconate kinase (GntK) (23) were aligned by using Multiseq in VMD 1.8.5 (24). PSTK sequences taken from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database were aligned to T4 Pnk and GntK also using Multiseq in VMD 1.8.5. Representative PSTK sequences were chosen from two archaea and four divergent eukaryotes for Figure 6. A model of M. jannaschii PSTK was generated using GntK (PDB code 1ltq) as the template with the program Modeller 9v2 and default parameters (25).

Figure 6.

Sequence based structure alignment and modeling of the kinase domain. (A) Alignment of the structures of E. coli gluconate kinase (GntK) and Enterobacter phage T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 Pnk) with representative PSTK sequences from two archaea and four divergent eukaryotes. Amino acids are colored according to sequence similarity (BLOSUM 50) and asterisks indicate key residues that were mutated and tested experimentally. The P-loop motif, GxxxxGK(S/T), the conserved Asp residue of the Walker B motif, and the conserved RxxxR motif that are involved in ATP-binding and Mg2+ coordination in T4 Pnk and GntK are shown. Residue numbering is shown adjacent to each sequence. The structures of Pnk (B) and GntK (C) are shown, with active site residues and bound substrates highlighted. (D) A homology model of M. jannaschii PSTK is shown with the predicted positions of key active site residues and docked ATP highlighted.

Phylogenetic analysis of PSTK

Sequences of PSTK, Kti12 and additional closely related DxTN kinases were identified using BLAST and downloaded from NCBI. Alignments were performed using MUSCLE (26), and manually adjusted using the CINEMA alignment editor (27). As detailed previously (28), the phylogenies were determined using a combined maximum parsimony/maximum likelihood method with the programs PAUP* (29), which was used to generate the 1000 most parsimonious trees, and PHYML v.2.4.4 (30), which was used to find the parsimony tree of maximum likelihood and optimize both the branch lengths and topology of that tree. Local bootstrap partitions were computed with MOLPHY (31). Final trees were graphed with the DRAWTREE program in PHYLIP version 3.66 (32). Trees were calculated similarly for the full length PSTK and Kti12 alignment as well as the kinase domain and C-terminal domain alignments, except that gaps were counted as missing data in the parsimony analysis of the DxTN kinase tree.

RESULTS

Establishment of a [32P]tRNA/nuclease P1 phosphotransferase assay

The biochemical characterization of M. jannaschii PSTK required a sensitive assay that would accurately monitor conversion of Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec. We thus adapted an assay that was successfully used for studies of the tRNA-dependent amidotransferases (33). It is based on digestion of [32P]-end-labeled aminoacyl-tRNA with nuclease P1 and separation of the resulting aminoacyl-[32P]AMP derivatives by TLC (34).

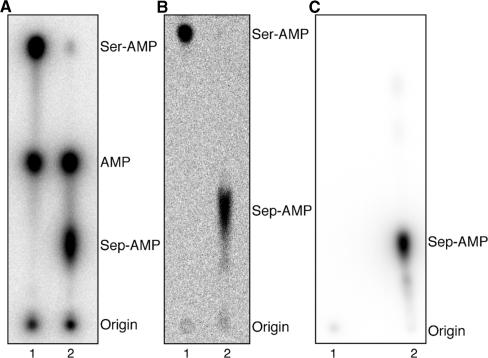

First, we 32P-labeled the terminal 3′-AMP of the tRNA using the exchange reaction of the E. coli CCA-adding enzyme in the presence of [α-32P]ATP. The radioactive tRNA was then serylated by pure M. maripaludis SerRS. After conversion of the Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec by M. jannaschii PSTK, the aa-tRNA products were digested by nuclease P1. The resulting mixture of Sep-[32P]AMP, [32P]AMP and Ser-[32P]AMP was separated on polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose plates by TLC (Figure 1A), giving Rf values of 0.29, 0.50 and 0.85, respectively. This assay allows direct monitoring of the deacylation of the substrate Ser-tRNASec and the product Sep-tRNASec that inevitably occurs over the course of the reaction. We should note that in this study we used the transcript of the M. maripaludis tRNASec; while SerRS serylated both M. jannaschii Ser-tRNASec and M. maripaludis Ser-tRNASec to 70–80%, M. jannaschii Ser-tRNASec deacylated more rapidly than M. maripaludis Ser-tRNASec.

Figure 1.

In vitro conversion of Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec by M. jannaschii PSTK. (A) PSTK assay with 32P-labeled tRNA. Representative phosphorimage of the separation of Ser-[32P]AMP, [32P]AMP and Sep-[32P]AMP by PEI cellulose chromatography is shown. 1 µM 32P-labeled tRNASec was incubated with 600 nM SerRS (lane 1) or 600 nM SerRS and 100 nM PSTK (lane 2) at 37°C for 45 min. Aliquots of the reactions were quenched with 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.0 and digested with 0.66 mg/ml nuclease P1 for 35 min at room temperature. Samples were then spotted onto a PEI-cellulose TLC plate and developed in 100 mM ammonium acetate, 5% acetic acid for 75 min. (B) PSTK assay using [14C]Ser. Phosphorimage of the separation of [14C]Ser-AMP and [14C]Sep-AMP on a PEI-cellulose TLC plate is shown. 2 µM tRNASec was incubated with 1.2 µM SerRS (lane 1) or 1.2 µM SerRS and 200 nM PSTK (lane 2) in the presence of 100 µM [14C]Ser for 45 min at 37°C. The aa-tRNASec products were purified as described in the Materials and Methods section, digested with nuclease P1 and chromatographed as above. (C) PSTK assay with γ-[32P]ATP as the phosphate donor. Phosphorimage of [32P]Sep-AMP on PEI-cellulose is shown. 1 µM Ser-tRNASer (lane 1) or 1 µM Ser-tRNASec (lane 2) was incubated with 100 nM PSTK with 1.67 µM γ-[32P]ATP for 45 min at 37°C. The reactions were purified over a Sephadex G25 Microspin column to remove unincorporated γ-[32P]ATP prior to digestion with nuclease P1 and TLC analysis as in (A).

To verify the identity of the Sep-AMP and Ser-AMP spots the same assay was used with unlabeled tRNASec and [14C]Ser (Figure 1B). The 14C label enabled us to observe the amino acid attached to the 3′-terminal AMP of the tRNA. Thus, SerRS formed [14C]Ser-tRNASec (Figure 1B, lane 1) which was then converted to [14C]Sep-tRNASec by PSTK (Figure 1B, lane 2). The [14C]Ser-AMP and [14C]Sep-AMP products of nuclease P1 digestion migrated similarly to Ser-[32P]AMP and Sep-[32P]AMP, respectively, on PEI cellulose plates (Figure 1A, B). The Rf values were 0.24 for [14C]Sep-AMP and 0.84 for [14C]Ser-AMP. As a final test, we confirmed the identity of the Sep-AMP spot by carrying out the assay with [γ-32P]ATP, unlabeled tRNASec and Ser. This yielded [γ-32P]Sep-AMP after nuclease P1 digestion (Figure 1C) which migrated with an Rf value of 0.27. While the aforementioned two assays (Figure 1B, 1C) show the migration of Ser-AMP and Sep-AMP, neither of them affords the sensitivity of the [32P]tRNA/nuclease P1 assay nor allows the aminoacylation state to be monitored as easily.

PSTK and its substrates

With the [32P]tRNA/nuclease P1 assay (Figure 2A), we were able to determine the steady state parameters of PSTK for ATP and Ser-tRNASec. The assay shows that PSTK is saturable at elevated substrate concentrations and does not display cooperativity, as the curve is not sigmoidal in a nonlinear regression plot of the initial velocities versus substrate concentrations (Figure 2B). The enzyme has a Km for ATP of 2.6 mM and for Ser-tRNASec of 40 nM (Table 1). These values are similar to the ones published previously for bovine PSTK, 2 mM and 21 nM, respectively (8).

Table 1.

Kinetic data for M. jannaschii PSTK

| Substrate | Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 µM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ser-tRNASec a,d | 0.04 ± 0.007 | 0.098 ± 0.005 | 2.6 ± 0.49 |

| ATPb,d | 2600 ± 1000 | 0.069 ± 0.009 | 2.7 × 10−5 ± 1.1 × 10−5 |

| ATPc,d | 2430 ± 970 | 2.9 × 10−5 ± 3.0 × 10−6 | 1.1 × 10−8 ± 4.0 × 10−9 |

Steady-state kinetics of M. jannaschii PSTK phosphotransferase and ATPase activities are shown. See Materials and Methods section for details.

aATP (10 mM) was added in excess with 2 nM enzyme.

bSer-tRNASec (400–600 nM) was added in excess with 6 nM enzyme.

ctRNASec (1 µM) was added in excess with 200 nM enzyme.

dMeasurements were taken three times. Standard deviations are reported.

PSTK must be able to discriminate Ser-tRNASec from Ser-tRNASer (9). We therefore determined the binding affinity of M. jannaschii PSTK for Ser-tRNASec, tRNASec, Ser-tRNASer and tRNASer in a double filter-binding assay (16,17) where 32P-labeled tRNA transcript was incubated with increasing concentrations of PSTK, followed by binding to nitrocellose and nylon filters (Figure 3A) (see Materials and Methods section). A semi-log plot of the fraction of Ser-tRNASec bound to the nitrocellose filter versus the log of the concentration of PSTK (Figure 3B) showed that PSTK has a Kd value of 53.3 nM for Ser-tRNASec (Table 2), which is similar to the Km of PSTK for Ser-tRNASec, 40 nM (Table 1). Interestingly, the Kd of PSTK for tRNASec, 39.4 nM (Table 2), is similar to the Kd of PSTK for Ser-tRNASec, demonstrating that the aminoacylation state of tRNASec is not involved in PSTK recognition of its tRNA substrate. This is in contrast to the next enzyme in the selenocysteine biosynthesis pathway, SepSecS, which has a higher affinity for its substrate, Sep-tRNASec, than for either tRNASec or Ser-tRNASec (5), though neither Kd nor Km values have been reported.

Figure 3.

Binding affinity of PSTK for Ser-tRNASec. (A) Representative data showing a transition in the quantity of 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec retained by the nitrocellulose membrane (RNAbound) to the nylon membrane (RNAfree) as PSTK concentration decreases from 5 µM to 0.61 nM. Minimal deacylation of Ser-tRNASec occurred over this time frame under the described conditions. (B) Semilog plot of the fraction of RNA bound versus the log of the concentration of PSTK.

Table 2.

Affinity of M. jannaschii PSTK for tRNASec and tRNASer

| Substrate | Kd (µM)a |

|---|---|

| tRNASec | 0.039 ± 0.003 |

| Ser-tRNASec | 0.053 ± 0.005 |

| tRNASer | 1.30 ± 0.14 |

| Ser-tRNASer | 1.26 ± 0.30 |

aDissociation constants for binding were determined by enzyme titration using M. maripaludis tRNASec and tRNASer in vitro transcripts. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated twice. Standard deviations are reported.

As expected, PSTK has a much lower affinity for both tRNASer and Ser-tRNASer with Kd values of 1.30 µM and 1.26 µM (Table 2), respectively. Neither is a substrate for phosphorylation by PSTK (Figure 1C and data not shown) (9). PSTK recognizes both tRNASer and Ser-tRNASer with similar Kd values (Table 2), further revealing that the Ser moiety has no effect on binding affinity.

While PSTK was able to transfer the γ-phosphate of [γ-32P]ATP to the Ser moiety of Ser-tRNASec, we proceeded to establish whether the reaction was tRNA-dependent. We attempted to phosphorylate free Ser with [γ-32P]ATP (data not shown), followed by TLC separation as described for Figure 1. There was, however, no detectable conversion of Ser to Sep, suggesting that PSTK does not recognize free Ser as a substrate for phosphate transfer; Ser attached to tRNASec is its obligate substrate.

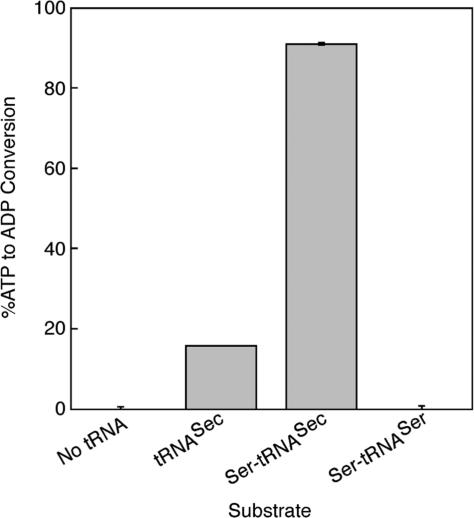

PSTK is a tRNASec-induced ATPase

Since PSTK recognizes both tRNASec and Ser-tRNASec with equal affinity, we determined if the binding of tRNASec would stimulate ATPase activity or if Ser-tRNASec was required. PSTK was assayed for ATPase activity using [α-32P]ATP as a substrate. The reaction product, [α-32P]ADP was separated from [α-32P]ATP by TLC on PEI-cellulose plates and quantified with a PhosphorImager. The ATPase activity was tested in the absence of tRNA or presence of tRNASec, Ser-tRNASec or Ser-tRNASer (Figure 4). There was little ATP hydrolysis when no tRNA or Ser-tRNASer was present, but addition of Ser-tRNASec increased the ATPase activity 20-fold over the control with no tRNA. Interestingly, addition of tRNASec resulted in a 4.3-fold increase in ATPase activity compared to the control with no tRNA. The steady-state ATPase activity in the presence of tRNASec was measured by an NADH-coupled assay, in which the production of free ADP was followed spectrophotometrically from the oxidation of NADH in a solution containing NADH, phosphoenolpyruvate, Mg2+, pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase (19,20). The Km for ATP in the presence of tRNASec, 2.43 mM, is similar to the Km for ATP, 2.6 mM, measured by the phosphotransferase assay in the presence of Ser-tRNASec (Table 1). The results suggest that PSTK uses an induced fit mechanism (35) where binding of one substrate (tRNASec) specifically induces hydrolysis of the ATP substrate similar to the mechanism of yeast hexokinase (36).

Figure 4.

ATPase activity of M. jannaschii PSTK. Graph of the ratio of [α-32P]ATP converted to [α-32P]ADP by PSTK (200 nM) in the absence or presence of 1 µM tRNASec, Ser-tRNASec, or Ser-tRNASer. After incubation at 37°C for 45 min, the reactions were quenched with ice-cold EDTA and spotted on PEI-cellulose TLC plates which were developed in 1 M LiCl for 60 to 75 min. PhosphorImager analysis was used to quantify the intensities of the [α-32P]ATP and [α-32P]ADP spots. The minimal ATPase activity in the absence of tRNA was subtracted. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three separate experiments.

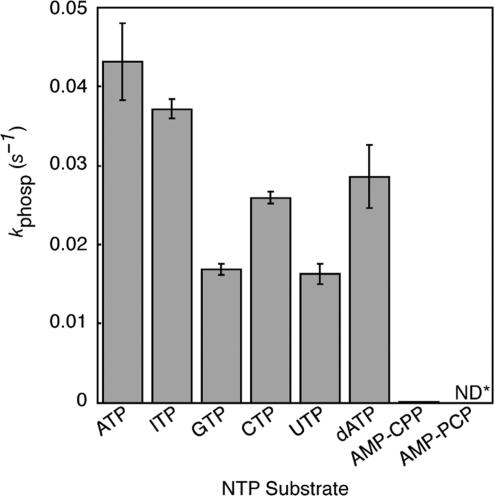

NTP substrate preferences of PSTK

We tested PSTK to determine activity with different nucleotides by measuring the initial velocity (kphosph) of Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec conversion in the presence of 20 mM ATP, ITP, GTP, CTP, UTP, AMP-CPP, AMP-PCP or dATP (Figure 5). The reaction proceeded most quickly in the presence of ATP, but PSTK was able to use dATP and all the rNTPs tested to form Sep-tRNASec. Even pyrimidine nucleotides were used at greater than 50% activity. Phosphorylation activity was low in the presence of the ATP analog AMP-CPP, suggesting that the bridging oxygen atom between the α- and β-phosphates may be important for NTP recognition. As expected, there was no detectible phosphorylation activity in the presence of AMP-PCP.

Figure 5.

Specificity of M. jannaschii PSTK for the phosphoryl donor. Initial velocities for the phosphotransferase activity of PSTK (6 nM PSTK without NTP or the addition of ATP, ITP, GTP, CTP, UTP or dATP or 200 nM PSTK with AMP-CPP or AMP-PCP) in the presence of the indicated phosphoryl donors (20 mM). Reactions proceeded for 6 min at 37°C and 1.5 min time points were taken and analyzed as in Figure 1A and 2. *ND, no detectable phosphorylation. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three experiments.

Modeling of the N-terminal kinase domain of PSTK and mutation of putative functional residues

The N-terminal region of M. jannaschii PSTK is homologous to a large superfamily of P-loop kinases (37). Structures complexed with ADP and ATP/Mg2+ are available for T4 Pnk (21) and GntK (23), respectively. These proteins are homologous to the kinase domain of PSTK (N-terminal 150 amino acids). We generated a structure-based sequence alignment of T4 Pnk, GntK and all available PSTK sequences, which revealed conserved motifs that are likely involved in ATP-binding and Mg2+ coordination (Figure 6).

Both T4 Pnk and GntK have a P-loop motif, i.e. Walker A motif, GxxxxGK(T/S), which is characteristic of nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) phosphoanhydrolases and phosphotransferases (38,39). The P-loop motif functions to position the triphosphate moiety of a bound nucleotide for hydrolysis of the β-γ phosphate bond. PSTK also has a conserved P-loop motif, 11GxP(G/A)xGK(S/T)18 (in the M. jannaschii numbering) (Figure 6). An invariant aspartic acid residue in PSTK (D41) (Figure 6A) likely corresponds to the Walker B motif (DxxG), which is common to P-loop kinases (40). An additional ATP-binding motif (RxxxR) is conserved as 116RNxxR121 in PSTK (Figure 6A) and is also present in structures of chloramphenicol phosphotransferase (41), adenylate kinase (42), T4 Pnk (22) and GntK (23).

Based on the above information and the knowledge that residues Lys15, Ser16, Asp35 and Arg126 are required for 5′-kinase activity of T4 Pnk, we made mutations of key residues likely involved in ATP-binding and Mg2+ coordination in M. jannaschii PSTK (Figure 6). The interactions of the conserved residues Gly14 and Thr19 with ATP were unlikely to be sequence-specific, thus these residues were replaced with a bulky amino acid, Trp. Single Ala mutations were made of the residues Lys17 and Ser18 in the P-loop motif, Asp41, the conserved Asp in the Walker B motif, and Arg116 and Arg120 in the RxxxR motif.

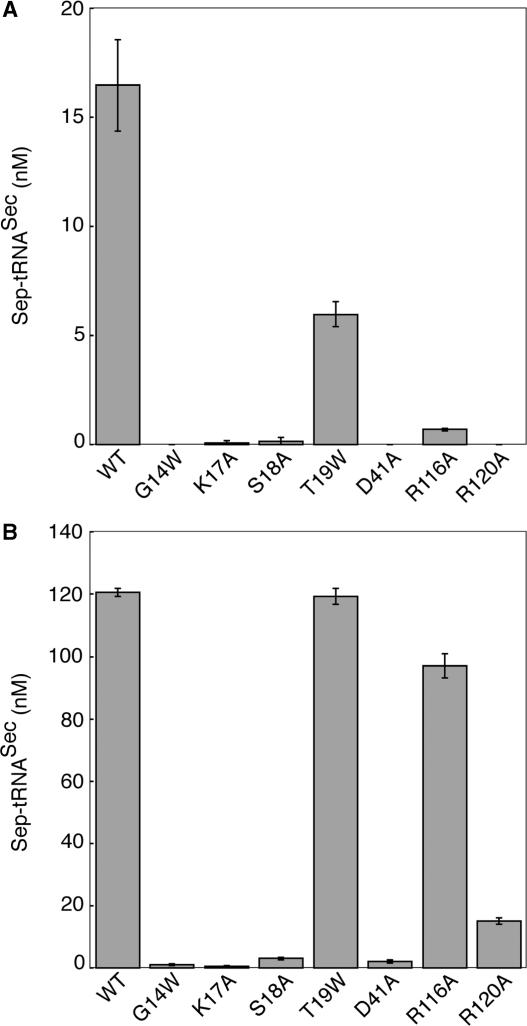

In vivo activity of PSTK mutants

A previously used assay (4) was available to give an in vivo functional test of PSTK. E. coli produces the selenium-dependent formate dehydrogenase H (FDHH) when grown under anaerobic atmosphere, and FDHH activity allows the cells to reduce benzyl viologen (BV) in the presence of formate (43). Co-expression of M. jannaschii PSTK and SepSecS in an E. coli selA deletion strain (JS1) in which selenoprotein production is abolished restores selenoprotein biosynthesis (4). Growth of the E. coli cells under anaerobic atmosphere (CO2 90%: N2 5%: H2 5%) for 24 h followed by a top agar overlay containing formate and BV resulted in violet-colored cells when BV was reduced due to the activity of the selenoprotein FDHH (4). We utilized JS1 to test the ability of our M. jannaschii PSTK mutants G14W, K17A, S18A, T19W, D41A, R116A and R120A with M. jannaschii SepSecS to complement the selA deletion. Complementation did not occur in the presence of PSTK alone, SepSecS alone, or in the presence of empty expression vectors (Figure 7). Wild-type PSTK and the T19W mutant were able to fully complement the JS1 strain, while the R116A mutant was able to complement to a lesser degree, as seen by the lighter violet colonies (Figure 7B). Mutants G14W, K17A, S18A, located within the P-loop, D41A, in the Walker B motif, and R120A, in the RxxxR motif, were unable to complement the JS1 strain (Figure 7), demonstrating the importance of the mutated amino acids for PSTK activity in vivo. These in vivo complementation studies confirmed the importance of the P-loop, Walker B motif, and RxxxR motif residues.

Figure 7.

In vivo assays of M. jannaschii PSTK mutants. Formation of Sep-tRNASec in vivo is assayed by the ability of the wild-type PSTK and its mutant variants (G14W, K17A, S18A, T19W, D41A, R116A, R120A) to restore the benzyl viologen reducing activity (seen as a violet color) of the selenoprotein FDHH in the E. coli selA deletion strain JS1. Cotransformation of the SepSecS gene from M. jannaschii is required for the conversion of Sep-tRNASec to Sec-tRNASec, which is then used during translation of FDHH.

In vitro phosphotransferase activity of PSTK mutants

In order to demonstrate that the in vivo deficiencies in BV reduction were properties of PSTK, the phosphotransferase assay was used to determine in vitro activity of the mutant enzymes. We found that G14, K17, S18, D41 and R120 are essential constituents of the PSTK active site. All of the mutant enzyme preparations were analyzed in parallel to determine their ability to convert Ser-tRNASec to Sep-tRNASec using the [32P]tRNA/nuclease P1 assay. At 10 nM enzyme, the mutant enzymes displayed reduced phosphotransferase activity (Figure 8A). The T19W enzyme was 2.8-fold less active than wild-type PSTK, while the R116A enzyme was 23.5-fold less active. The remaining mutants displayed little detectable activity. To determine if these mutant enzymes exhibited any catalytic activity, we increased the time of the assay from 1 to 5 min and assayed the enzymes at a higher enzyme concentration, 100 nM (Figure 8B). However, four mutants, G14W, K17A, S18A and D41A, were grossly deficient in phosphotransferase activity at both enzyme concentrations. Sep-tRNASec formation was saturated with the T19W enzyme at 100 nM enzyme. R116A was 1.2-fold less active than wild-type, whereas R120A had a more severe effect on catalysis, with 7.9-fold less activity than wild-type enzyme.

Figure 8.

In vitro assays of M. jannaschii PSTK mutants. The catalytic activity of the ATP-binding site mutants G14W, K17A, S18A, T19W, D41A, R116A and R120A was tested using the phosphotransferase assay. (A) 10 nM enzyme was incubated with 200 nM 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec for 1 min at 37°C. (B) 100 nM enzyme was incubated with 200 nM 32P-labeled Ser-tRNASec for 5 min at 37°C. The reactions were analyzed as in Figure 1A and 2. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three experiments.

Phylogenetic analysis of PSTK

PSTK is a protein composed of two domains. The N-terminal P-loop kinase domain belongs to a family of related kinases including both cellular and viral polynucleotide kinase, phosphoserine/phosphothreonine kinase as well as bacterial kinases of unknown function. The second domain, which is presumed to be involved in tRNASec recognition in PSTK, is found only in one other group of eukaryotic proteins of which the yeast examples are named Kti12 (killer toxin-insensitive) in reference to the gene's ability to confer yeast resistance to the Kluyveromyces lactis toxin zymocin (44). Kti12 is required for the biosynthesis of certain tRNA modifications (45), but its precise function is unknown. A genetic deletion of KTI12 in yeast abolished formation of mcm5- and ncm5-modified uridines at the wobble position of some tRNAs and caused growth defects (45). Based on its close homology with PSTK, we predict that Kti12 interacts directly with its tRNA substrates. Perhaps, like PSTK, Kti12 is also a tRNA-dependent kinase.

The strong similarity of PSTK and Kti12 throughout the full-length of the molecule along with misannotations in the sequence databases led to a previous misclassification of some Kti12 proteins as PSTKs (4). In addition to presenting a resolved phylogeny of PSTK and Kti12 (Supplementary Data Figures 1 and 2), we also computed the phylogenetic root between these proteins. Such a root helps determine if Kti12 is derived from the eukaryotic PSTK or if Kti12 diverged from PSTK at some earlier time. A set of more distantly related (so-called out group) sequences is required to place the root. Since PSTK and Kti12 only display homology with other proteins in their kinase domain, their root must be determined from a phylogeny based only on the kinase domain (Figure 9). This tree shows a deep separation between the PSTK/Kti12 cluster and the other kinases in their family.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of the kinase domains of PSTK, Kti12 and representative groups of closely related ‘DxTN’ kinases, which include cellular and viral polynucleotide kinases (Pnk) and the phosphoserine/phosphothreonine kinases (PrpA). Organism names are color-coded: Archaea (blue), Eukarya (green), Bacteria (red) and viruses (purple). Bootstrap values for major branches are shown. All bootstrap values are included in Supplementary Figure 3.

The evolution of PSTK and Kti12 is characterized by vertical gene flow, i.e. organismal groupings are essentially in accord with standard taxonomy, and gene loss. Kti12 is present in nearly all eukaryotes, though noticeably absent from Trypanosomatidae and Plasmodium. All non-Sec decoding eukaryotes and archaea lack PSTK. Based on current genomic data, and with our identification of PSTK in Plasmodium, we observed that all organisms that encode SepSecS also encode PSTK (see Supplementary Table 1). The Plasmodium PSTK, however, cannot be recovered with a typical BLAST search of the NCBI databases. Only by using the PlasmoDB (46) BLAST server with the kinase domain of the fly PSTK as a query and searching over the ‘protein’ database of all Plasmodium species could a partial hit to a P. knowlesi open reading frame (ORF) be found. Four additional Plasmodium PSTKs were then readily discovered based on homology with the P. knowlesi ORF. A proper alignment of these Plasmodium sequences to other PSTKs revealed conserved PSTK active site residues and the phylogeny resulting from that alignment clearly supports the grouping of the Plasmodium PSTKs with their other eukaryotic counterparts (Figure 9).

The vertical inheritance pattern and deep phylogenetic divide between archaeal and eukaryotic PSTKs (Figure 9) shows that the protein originated before the evolutionary divergence of the domains Archaea and Eukarya. Kti12 is restricted to eukaryotes, yet it appears to have originated from a duplication of the ancestor of the archaeal and eukaryotic PSTKs. The phylogenetic relationship between PSTK and Kti12, which is also supported in phylogenies of the full-length and C-terminal domains (see Supplementary Data Figure 1 and 2), indicates that the eukaryotic protein, Kti12, evolved before the phylogenetic divergence of the archaeal and eukaryotic domains.

DISCUSSION

PSTK recognition of its tRNA substrate

PSTK not only has high affinity for its substrate, Ser-tRNASec, but surprisingly also binds unacylated tRNASec more tightly than does the human SerRS (41). Aminoacyl tRNA-synthetases typically have a higher affinity for their substrates, unacylated tRNAs, than for their products, aminoacyl-tRNAs. Why PSTK has high affinity for unacylated tRNASec is unclear. Mizutani and Hashimoto estimated the cytoplasmic concentration of tRNASec to be quite low at 50 nM (8); PSTK could possibly sequester tRNASec for acylation by SerRS in order to channel the tRNA from one enzyme to the next so that a ‘mis’-acylated tRNA is never available for use in protein translation. Whether these two enzymes and/or SepSecS form a complex is yet an open question. What is apparent, however, from the Kd values of PSTK for tRNASec, Ser-tRNASec, tRNASer and Ser-tRNASer, is that selection for the tRNA substrate is based on the tRNA alone and not the serine moiety.

ATP-binding site of PSTK

PSTK catalyzes transfer of the γ-phosphate of an NTP to the hydroxyl group of Ser on Ser-tRNASec to form Sep-tRNASec. The active site of PSTK employs a P-loop motif, 11GxP(G/A)xGK(S/T)18, a Walker B motif (D41), and a 116RNxxR121 motif for ATPase and phosphotransferase activities. Based on our homology model of the PSTK kinase domain (Figure 6D), we predicted the roles of several key residues in these motifs: G14, K17, S18, T19, D41, R116, and R120.

In the P-loop motif, Gly18 in GntK (23), which aligns to Gly14 in M. jannaschii PSTK, forms a hydrogen bond with the bridging oxygen of the γ-phosphate of ATP in a non-sequence dependent manner. We perturbed this essential contact with a G14W mutation that caused the loss of both in vivo and in vitro activities. Conserved Lys and Ser residues in the P-loops of T4 Pnk and GntK are essential for ATP-binding. These residues make specific contacts with the β- and γ-phosphates of ATP (21,22). In GntK, the side-chain hydroxyl on this serine residue (Ser22) also coordinates the Mg2+, which is bound to the substrate ATP (23). Similarly, the corresponding residues in M. jannaschii PSTK, Lys17 and Ser18, were required for in vivo activity and separate alanine mutants displayed minimal in vitro activity. The backbone nitrogen of Thr17 in T4 Pnk and Ala23 in GntK interact with the α-phosphate of ATP, and our model of PSTK suggests a similar role for Thr19. Mutation of this residue to Trp resulted in partially active enzyme.

The Walker B motif is less clearly defined than the P-loop, but it must contain a negatively charged residue (typically Asp) that is involved in binding Mg2+ (47). GntK (23) and T4 Pnk (22) also have a conserved Asp at a homologous position. Even though this residue is distant from the active site, it contributes to Mg2+ binding via a water-mediated hydrogen bond, as observed in GntK (23) (Figure 6C). Mutation of the corresponding Asp (D41A) in PSTK drastically reduced activity of the enzyme. These data support our prediction that D41 is the essential feature of the Walker B motif in PSTK, and it likely has a similar role to the homologous Asp residues in T4 Pnk and GntK.

In both Pnk and GntK, the proximal Arg of the RxxxR motif forms a cation–π interaction with the adenylate's conjugated rings. The GntK structure suggests that the distal Arg interacts with the α-phosphate of ATP, and the T4 Pnk structure suggests that this Arg interacts with the ester linkage between the 5′-hydroxyl of the ribose and the α-phosphate of ADP after ATP hydrolysis. In PSTK, mutation of the distal Arg (R120A) had a more severe effect on catalysis than mutation of Arg116. This indicates that in PSTK the cation–π interaction of Arg116 with the ATP substrate is less important than the specific interaction of Arg120 with the α-phosphate of ATP.

In summary, we experimentally determined that the Gly14, Lys17, Ser18, Asp41, Arg116 and Arg120 residues are important or required for enzyme activity both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that they make contacts in ATP-binding and Mg2+ coordination similar to those observed in the crystal structures of T4 Pnk and GntK.

NTP preference of PSTK

Interestingly, the binding site for the phosphate donating NTP exhibits little specificity in PSTK. T4 Pnk is also able to utilize multiple NTPs (48), which is supported by the crystal structure that shows the contacts between the enzyme and ADP are mostly through interactions with the phosphate oxygens (21). Crystal structures of other P-loop proteins show similar contacts (23,49). The broad occurrence of relaxed NTP specificity for P-loop kinases is unknown. Some P-loop NTPases have higher specificity for a particular phosphate donor, e.g. GTP was preferred 100-fold over other NTPs by yeast tRNA ligase (50). In addition to a well-conserved Walker B motif (DxxG), an evolutionary study of P-loop GTPases and GTPase-related proteins found a NKxD motif is linked to GTP-specificity (51). Though we do not know the physiological phosphate donor for PSTK, there is a preference for ATP in vitro. Characterizing PSTK as an NTP generalist may allow further investigation into the molecular basis of NTP specificity.

Insights into PSTK catalysis

P-loop-containing enzymes typically either catalyze their reactions by a proton-abstracting acidic residue or the γ-phosphate of the NTP phosphate donor acts as a base in substrate-assisted catalysis (37). Our observation that PSTK has little detectable ATPase activity in the absence of tRNASec, and that this activity is greatly stimulated in the presence of Ser-tRNASec was thus not unexpected. The Ser hydroxyl may be the attacking nucleophile, possibly activated by abstraction of a proton. D35 in T4 Pnk was identified as a potential proton-abstracting residue (22), and D41 in M. jannaschii PSTK aligns to this residue (Figure 6). Our D41A enzyme was severely deficient in both phosphotransferase and ATPase activities in vitro and unable to complement the E. coli selA deletion strain in vivo. Whether this was due to a role for D41 in Mg2+ coordination as discussed previously or required as a base for proton-abstraction requires further analysis.

Evolutionary history of PSTK

PSTK and SepSecS complete the archaeal and eukaryotic pathway for Sec-tRNASec formation. The more detailed phylogeny presented here resolves evolutionary idiosyncrasies observed previously for PSTK (4) and shows that PSTK exactly co-evolved with SepSecS. This pathway was vertically inherited over the course of its evolution which originated before the archaeal-eukaryotic phylogenetic divide, though how long before will remain an unresolved issue.

The phylogenetic analysis also identifies an evolutionarily bona fide PSTK in the Plasmodium species. These parasites are known for their accelerated evolutionary clock (52), and PSTK is no exception. The Plasmodium PSTKs have evolved at a significantly faster rate (note their long branch in Figure 9) than their counterparts in other eukaryotes. Indeed, the Plasmodium PSTKs evolved at such a fast rate that even detecting these PSTKs by sequence homology is rather difficult, explaining why this gene has not been identified previously or properly annotated.

Kti12, which is the only known protein that is homologous to the full-length of PSTK, is a eukaryotic signature gene that evolved before the archaeal-eukaryotic phylogenetic divide. The signature gene notion was developed by Woese and colleagues as they sought to understand how the Archaea are so distinct from Eukarya and Bacteria. They defined the archaeal genomic signature as ‘the set of genes that function uniquely within the archaeal lineage’ (53). Signature genes also exist in Bacteria and Eukarya. Hartman and Federov explored the eukaryotic signature in detail (54), but limited their set of signature genes to those without homologs in Archaea or Bacteria. This study identified genes involved in eukaryotic specific cellular structures including the cytoskeleton, nucleus, internal membranes and signaling as well as eukaryotic specific features of protein synthesis and degradation. Although this study produced an admittedly minimal set of eukaryotic signature genes, it is clear that the eukaryotic signature is broader than previously thought including proteins, which are involved in more basic cellular functions, such as tRNA modification in the case of Kti12.

Since Kti12 is restricted to eukaryotic genomes and because it is closely related to PSTK one might speculate that Kti12 is a duplication of the eukaryotic PSTK. The inclusion of related kinases in the phylogenetic analysis of PSTK and Kti12 (Figure 9) allows the determination of a root between PSTK and Kti12, which leads to the conclusion that Kti12 diverged from the archaeal-eukaryotic ancestral PSTK. Two points of fundamental significance for understanding the evolution of the eukaryotic cell type are brought to light in the PSTK-Kti12 phylogeny: (i) many more eukaryotic signature genes exist with roles in a broader range and perhaps in more basic cellular functions than previously recognized and (ii) lineage defining signature genes can evolve before the phylogenetic split of that lineage from its sister lineage. Archaeal and bacterial signature genes have been shown to predate the phylogenetic divide between the domains Archaea and Bacteria (28) and now we document this phenomenon in eukaryotes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Kelly Sheppard, Jeff Sabina, Jing Yuan, Sotiria Palioura, Adrian Olivares, Lennart Randau and Markus Englert for technical advice and many discussions, and Joanne Ho for her enthusiastic support. We thank Enrique De La Cruz for the use of the Perkin Elmer Lambda 20 UV/Vis Spectrometer in his laboratory. R.L.S. holds a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32 GM075602 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and P. O’D. is a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in Biological Informatics. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Department of Energy (to D.S.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM22854 (to D.S.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Böck A, Thanbichler M, Rother M, Resch A. In: Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Ibba M, Francklyn CS, Cusack S, editors. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2005. pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson BA, Xu XM, Kryukov GV, Rao M, Berry MJ, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Identification and characterization of phosphoseryl-tRNA[Ser]Sec kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12848–12853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402636101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaiser JT, Gromadski K, Rother M, Engelhardt H, Rodnina MV, Wahl MC. Structural and functional investigation of a putative archaeal selenocysteine synthase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13315–13327. doi: 10.1021/bi051110r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan J, Palioura S, Salazar JC, Su D, O’Donoghue P, Hohn MJ, Cardoso AM, Whitman WB, Söll D. RNA-dependent conversion of phosphoserine forms selenocysteine in eukaryotes and archaea. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18923–18927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609703104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu XM, Carlson BA, Mix H, Zhang Y, Saira K, Glass RS, Berry MJ, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Biosynthesis of selenocysteine on its tRNA in eukaryotes. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050004. Epub: doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäenpää PH, Bernfield MR. A specific hepatic transfer RNA for phosphoserine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1970;67:688–695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp SJ, Stewart TS. The characterization of phosphoseryl tRNA from lactating bovine mammary gland. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4:2123–2136. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.7.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizutani T, Hashimoto A. Purification and properties of suppressor seryl-tRNA: ATP phosphotransferase from bovine liver. FEBS Lett. 1984;169:319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu XQ, Gross HJ. The length and the secondary structure of the D-stem of human selenocysteine tRNA are the major identity determinants for serine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1994;13:241–248. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilokapic S, Korencic D, Söll D, Weygand-Durasevic I. The unusual methanogenic seryl-tRNA synthetase recognizes tRNASer species from all three kingdoms of life. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:694–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2003.03971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milligan JF, Groebe DR, Witherell GW, Uhlenbeck OC. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshikane H, Sheppard K, Fukai S, Nakamura Y, Ishitani R, Numata T, Sherrer RL, Feng L, Schmitt E, et al. Structural basis of RNA-dependent recruitment of glutamine to the genetic code. Science. 2006;312:1950–1954. doi: 10.1126/science.1128470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bullock TL, Uter N, Nissan TA, Perona JJ. Amino acid discrimination by a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specified by negative determinants. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:395–408. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC. Modulation of tRNAAla identity by inorganic pyrophosphatase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5965–5970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092152799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabina J, Söll D. The RNA-binding PUA domain of archaeal tRNA-guanine transglycosylase is not required for archaeosine formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6993–7001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong I, Lohman TM. A double-filter method for nitrocellulose-filter binding: application to protein-nucleic acid interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5428–5432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zakalskiy A, Hogenauer G, Ishikawa T, Wehrschutz-Sigl E, Wendler F, Teis D, Zisser G, Steven AC, Bergler H. Structural and enzymatic properties of the AAA protein Drg1p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Decoupling of intracellular function from ATPase activity and hexamerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26788–26795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De La Cruz EM, Sweeney HL, Ostap EM. ADP inhibition of myosin V ATPase activity. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1524–1529. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trentham DR, Bardsley RG, Eccleston JF, Weeds AG. Elementary processes of the magnesium ion-dependent adenosine triphosphatase activity of heavy meromyosin. A transient kinetic approach to the study of kinases and adenosine triphosphatases and a colorimetric inorganic phosphate assay in situ. Biochem. J. 1972;126:635–644. doi: 10.1042/bj1260635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galburt EA, Pelletier J, Wilson G, Stoddard BL. Structure of a tRNA repair enzyme and molecular biology workhorse: T4 polynucleotide kinase. Structure. 2002;10:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00835-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang LK, Lima CD, Shuman S. Structure and mechanism of T4 polynucleotide kinase: an RNA repair enzyme. EMBO J. 2002;21:3873–3880. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraft L, Sprenger GA, Lindqvist Y. Conformational changes during the catalytic cycle of gluconate kinase as revealed by X-ray crystallography. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;318:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts E, Eargle J, Wright D, Luthey-Schulten Z. MultiSeq: Unifying sequence and structure data for evolutionary analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:382. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettifer SR, Sinnott JR, Attwood TK. UTOPIA – user-friendly tools for operating informatics applications. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:56–60. doi: 10.1002/cfg.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Donoghue P, Sethi A, Woese CR, Luthey-Schulten ZA. The evolutionary history of Cys-tRNACys formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:19003–19008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509617102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swofford D. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2003. (Version 4) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adachi J, Hasegawa M. MOLPHY: Programs for Molecular Phylogenetics Based on Maximum Likelihood (Version 2.3) Comp. Sci. Monogr. 1996;28:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP – Phylogeny Interference Package (Version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheppard K, Akochy PM, Salazar JC, Söll D. The Helicobacter pylori amidotransferase GatCAB is equally efficient in glutamine-dependent transamidation of Asp-tRNAAsn and Glu-tRNAGln. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11866–11873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfson AD, Pleiss JA, Uhlenbeck OC. A new assay for tRNA aminoacylation kinetics. RNA. 1998;4:1019–1023. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshland DE. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1958;44:98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DelaFuente G, Lagunas R, Sols A. Induced fit in yeast hexokinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1970;16:226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolution and classification of P-loop kinases and related proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:781–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saraste M, Sibbald PR, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop – a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Via A, Ferre F, Brannetti B, Valencia A, Helmer-Citterich M. Three-dimensional view of the surface motif associated with the P-loop structure: cis and trans cases of convergent evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;303:455–465. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izard T, Ellis J. The crystal structures of chloramphenicol phosphotransferase reveal a novel inactivation mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:2690–2700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berry MB, Phillips G.N., Jr Crystal structures of Bacillus stearothermophilus adenylate kinase with bound Ap5A, Mg2+ Ap5A, and Mn2+ Ap5A reveal an intermediate lid position and six coordinate octahedral geometry for bound Mg2+ and Mn2+ Proteins. 1998;32:276–288. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980815)32:3<276::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lacourciere GM, Levine RL, Stadtman TC. Direct detection of potential selenium delivery proteins by using an Escherichia coli strain unable to incorporate selenium from selenite into proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9150–9153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142291199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butler AR, Porter M, Stark MJ. Intracellular expression of Kluyveromyces lactis toxin gamma subunit mimics treatment with exogenous toxin and distinguishes two classes of toxin-resistant mutant. Yeast. 1991;7:617–625. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang B, Johansson MJ, Bystrom AS. An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the Elongator complex. RNA. 2005;11:424–436. doi: 10.1261/rna.7247705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bahl A, Brunk B, Crabtree J, Fraunholz MJ, Gajria B, Grant GR, Ginsburg H, Gupta D, Kissinger JC, et al. PlasmoDB: the plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:212–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. Nucleoside triphosphate-binding proteins: different scaffolds to achieve phosphoryl transfer. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1999;32:1–56. doi: 10.1017/s0033583599003480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novogrodsky A, Tal M, Traub A, Hurwitz J. The enzymatic phosphorylation of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid. II. Further properties of the 5'-hydroxyl polynucleotide kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1966;241:2933–2943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berry MB, Meador B, Bilderback T, Liang P, Glaser M, Phillips G.N., Jr The closed conformation of a highly flexible protein: the structure of E. coli adenylate kinase with bound AMP and AMPPNP. Proteins. 1994;19:183–198. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belford HG, Westaway SK, Abelson J, Greer CL. Multiple nucleotide cofactor use by yeast ligase in tRNA splicing. Evidence for independent ATP- and GTP-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:2444–2450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leipe DD, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:41–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, Borevitz JO, Plouffe D, Zhou Y, Johnson JR, Le Roch K, Sarr O, et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graham DE, Overbeek R, Olsen GJ, Woese CR. An archaeal genomic signature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3304–3308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050564797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartman H, Fedorov A. The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1420–1425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032658599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.