Abstract

Aspergillus section Clavati has been revised using morphology, secondary metabolites, physiological characters and DNA sequences. Phylogenetic analysis of β-tubulin, ITS and calmodulin sequence data indicated that Aspergillus section Clavati includes 6 species, A. clavatus (synonyms: A. apicalis, A. pallidus), A. giganteus, A. rhizopodus, A. longivesica, Neocarpenteles acanthosporus and A. clavatonanicus. Neocarpenteles acanthosporus is the only known teleomorph of this section. The sister genera to Neocarpenteles are Neosartorya and Dichotomomyces based on sequence data. Species in Neosartorya and Neocarpenteles have anamorphs with green conidia and share the production of tryptoquivalins, while Dichotomomyces was found to be able to produce gliotoxin, which is also produced by some Neosartorya species, and tryptoquivalines and tryptoquivalones produced by members of both section Clavati and Fumigati. All species in section Clavati are alkalitolerant and acidotolerant and they all have clavate conidial heads. Many species are coprophilic and produce the effective antibiotic patulin. Members of section Clavati also produce antafumicin, tryptoquivalines, cytochalasins, sarcins, dehydrocarolic acid and kotanins (orlandin, desmethylkotanin and kotanin) in species specific combinations. Another species previously assigned to section Clavati, A. ingratus is considered a synonym of Hemicarpenteles paradoxus, which is phylogenetically very distantly related to Neocarpenteles and section Clavati.

Keywords: Ascomycetes, Aspergillus section Clavati, β-tubulin, calmodulin, Dichotomomyces, Eurotiales, Hemicarpenteles, ITS, mycotoxin, Neocarpenteles, patulin, polyphasic taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

Species in Aspergillus section Clavati are alkalitolerant, often dung-borne species that produce several mycotoxins such as patulin (Varga et al. 2003), cytochalasins (Demain et al. 1976; Steyn et al. 1982), tryptoquivalines and tryptoquivalones (Clardy et al. 1975; Büchi et al. 1977), and other bioactive natural products, including the sarcins (Cole & Cox 1981; Lin et al. 1994). Weisner (1942) and Bergel et al. 1943 found that A. clavatus produces patulin, and Florey et al. (1944) reported on patulin production by Aspergillus giganteus in 1944. Clavatol (Bergel et al. 1944) and ascladiol (Suzuki et al. 1971) were also isolates from A. clavatus as antibiotics. Cytochalasin E and K are also mycotoxins known from Aspergillus clavatus (Demain et al. 1976). A. clavatus was also reported to produce kotanin and xanthocillin X dimethylether (Büchi et al. 1977). Among the mycotoxins produced, patulin is receiving world-wide attention due to its frequent occurrence in apple juices (Harrison 1989; Beretta et al. 2000). Aspergillus clavatus, A. giganteus and Neocarpenteles acanthosporus isolates also produce ribotoxins, which are promising tools for immunotherapy of cancer (Martinez-Ruiz et al. 1999; Varga et al. 2003). The economically most important species of the section, A. clavatus is possibly a cosmopolitan fungus. It can be isolated mainly from soil and dung, but also occurs on stored products (mainly cereals) with high moisture content, e.g. inadequately stored rice, corn and millet (Flannigan & Pearce 1994). A. clavatus isolates appear to be particularly well adapted for growth during malting (Flannigan & Pearce 1994). A. clavatus was found to be responsible for an extrinsic allergic alveolitis known as malt worker”s lung, and in cases of mycotoxicoses of animals fed with by-products of malting (Flannigan & Pearce 1994; Lopez-Diaz & Flannigan 1997). The toxic syndromes observed in animals were suggested to result from the synergistic action of various mycotoxins produced by this species (Flannigan & Pearce 1994). Several species of section Clavati have phototrophic long conidiophores at temperatures around 20-23 °C (Fennell & Raper 1955; Trinci & Banbury 1967; Sarbhoy & Elphick 1968; Huang & Raper 1971; Yaguchi et al. 1993).

Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati section Clavati (Gams et al. 1985; Peterson 2000), formerly the Aspergillus clavatus group was recognised by Thom & Church (1926) with two species, A. clavatus and A. giganteus. A. clavatonanicus was added by Batista et al. (1955). After Raper & Fennell (1965) published their monograph on aspergilli, several new species or varieties assigned to section Clavati were described. These were summarised by Samson (1979), who recognised A. longivesica (Huang & Raper 1971) as the fourth species within the section. None of these have known teleomorphs. Another species, A. rhizopodus (Rai et al. 1975) was treated by Samson (1979) as a synonym of A. giganteus. A. pallidus Kamyschko has been treated as a white-spored synonym of A. clavatus by several authors (Peterson 2000; Varga et al. 2003). A. acanthosporus (Udagawa & Takada (1971), placed in subgenus Ornati (Samson 1979), was shown by Peterson (2000) to be more closely related to section Clavati than to section Ornati. Also, their major ubiquinone systems point in this direction as section Clavati and A. acanthosporus have Q10, while H. ornatus has Q9 ubiquinones (Tamura et al. 1999). Although its teleomorph was originally placed into the Hemicarpenteles genus, recently Udagawa & Uchiyama (2002) proposed the new ascomycete genus Neocarpenteles to accommodate this species, and excluded N. acanthosporus from section Ornati. Similar conclusions were drawn by Varga et al. (2003) based on sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions and the 5.8 S rRNA gene (ITS region) of isolates belonging to Aspergillus section Clavati. Another species, A. apicalis Mehrotra & Basu (1976) (as A. apica), was placed in section Ornati by Samson (1979) because of morphological similarities to H. paradoxus (small clavate blue green aspergilla). Finally, A. ingratus has been described by Yaguchi et al. (1993), who stated that this sclerotium producing species belonged to section Clavati.

In this study, we examined the taxonomic assignment of these alkalitolerant species characterised by clavate aspergilla using molecular, morphological and chemotaxonomical methods. We also examined the relationships among teleomorphs of Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati, including Neocarpenteles and Neosartorya species to the Dichotomomyces genus using molecular approaches. Although the anamorphs of Dichotomomyces belong to the Polypaecilum, ascomata and ascospores of Dichotomomyces species have a similar morphology as those of Neosartorya and Neocarpenteles (Samson RA, unpubl. data).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of microorganisms

The fungi examined included all species allocated to Aspergillus section Clavati, and some species assigned to section Ornati with clavate aspergilla (the Aspergillus ornatus group), which could possibly be related to A. clavatus. The strains examined are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Aspergillus section Clavati isolates examined in this study.

| Species | Strain No. | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| A. clavatus | CBS 104.45 | ATCC 9600; Czech Republic, Pribram |

| CBS 105.45 | Church, No. Ac 87 | |

| CBS 106.45 | Humulus lupulus (Cannabaceae), G. Smith | |

| CBS 114.48 | Culture contaminant, Netherlands | |

| CBS 513.65T | ATCC 1007; IMI 015949; NRRL 1; Thom 107 | |

| CBS 514.65 | ATCC 10058; IMI 321306; NRRL 4; Thom 4754.3 | |

| CBS 470.91 | Toxic feed pellets, Hungary | |

| CBS 116685 | Milled rice, Netherlands | |

| CBS 118451 | Medicine, Germany | |

| DTO 6-F8 | Air, ciabatta factory, Netherlands | |

| DTO 27-C2 | Bakery, Netherlands | |

| SZMC 0918 | Soil, Hungary | |

| SZMC JV4 | Stored wheat, Hungary | |

| SZMC JV1.1 | Human mucosa, Hungary | |

| IMI 358435 | Feed pellet, Hungary | |

| A. giganteus | CBS 117.45 | IMI 024256; P. Biourge |

| CBS 119.48 | H. Burgeff, No. 382, Germany | |

| CBS 118.49 | Wood of ship (Virola surinamensis), Suriname | |

| CBS 122.53 | Tail borad, Nigeria | |

| CBS 117.56 | Wood in swimming pool, Netherlands | |

| CBS 101.64 | Unknown, Poland | |

| CBS 515.65T | ATCC 16439; IMI 235601; NRRL 7974; mouse dung, U.S.A. | |

| CBS 526.65 | ATCC 10059; IMI 227678; NRRL 10; Thom 5581.13A | |

| CBS 112.27 | A. Blochwitz | |

| A. rhizopodus | CBS 450.75T | Usar soil, India, Lucknow |

| IMI 351309 | Soil, Yugoslavia | |

| A. pallidus | CBS 344.67T | ATCC 18327; IMI 129967; soil, Moldova |

| SZMC JV6 | Culture contaminant, Hungary | |

| A. clavatonanicus | CBS 474.65T | ATCC 12413; IMI 235352; WB 4741; finger nail lesion, Brazil |

| A. longivesica | CBS 530.71T | ATCC 22434; IMI 156966; soil, Nigeria |

| CBS 187.77 | Soil, Ivory Coast, Tai | |

| A. apicalis | CBS 236.81T | Wheat bran, India |

| N. acanthosporus | CBS 558.71T | Solomon Islands, Bougainville Island |

| CBS 445.75 | Solomon Islands, Bougainville Island, Buin, Malapita | |

| CBS 446.75 | Solomon Islands, Bougainville Island, Buin, Batubatuai | |

| CBS 447.75 | Solomon Islands, Bougainville Island, Kieta | |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 761.96 | spent mushroom compost, Netherlands |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 779.70 | Soil, Cincinatti, U.S.A. |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 100192 | Soil, Bratislava, Slovakia |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 474.77 | Soil, Egypt |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 780.70 | Pasturised milk, Cincinatti, U.S.A. |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 397.68 | Soil, South Africa |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 345.68 | rhizosphere of Hordeum vulgare, Pakistan |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 159.67 | Soil, Kominato, Japan |

| D. cepjii var. cejpii | CBS 157.66T | Orchard soil, Moldova, near Tiraspol |

| D. cepjii var. spinosus | CBS 219.67T | Soil, Kyoto, Japan |

Morphology and physiology

The strains (Table 1) were grown for 7 d as 3-point inoculations on Czapek agar (CZA), Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA), creatine sucrose agar (CREA) and malt extract agar (MEA) at 25 °C in artificial daylight (medium compositions in Samson et al. 2004).

Analysis for secondary metabolites

The cultures were analysed according to the HPLC-diode array detection method of Frisvad & Thrane (1987, 1993) as modified by Smedsgaard (1997). The isolates were analyzed on CYA and YES agar using three agar plugs (Smedsgaard 1997). The secondary metabolite production was confirmed by identical UV spectra with those of standards and by TLC analysis using the agar plug method, the TLC plates were eluted in toluene : ethylacetate:formic acid (6:3:1) and chloroform:acetone:2-propanol (85:15:20) (Filtenborg et al. 1983; Samson et al. 2004). Standards of patulin, cytochalasin E, kotanin, and nortryptoquivalin known to be produced by these fungi, were also used to confirm the identity of the compounds.

Isolation and analysis of nucleic acids

The cultures used for the molecular studies were grown on malt peptone (MP) broth using 10 % (v/v) of malt extract (Brix 10) and 0.1 % (w/v) Bacto peptone (Difco), 2 mL of medium in 15 mL tubes. The cultures were incubated at 25 °C for 7 d. DNA was extracted from the cells using the Masterpure™ yeast DNA purification kit (Epicentre Biotechnol.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Fragments containing the ITS region were amplified using primers ITS1 and ITS4 as described previously (White et al. 1990). Amplification of part of the β-tubulin gene was performed using the primers Bt2a and Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995). Amplifications of the partial calmodulin gene were set up as described previously (Hong et al. 2005). Sequence analysis was performed with the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit for both strands, and the sequences were aligned with the MT Navigator software (Applied Biosystems). All the sequencing reactions were purified by gel filtration through Sephadex G-50 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated in double-distilled water and analyzed on the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The unique ITS, β-tubulin, actin and calmodulin sequences were deposited at the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession numbers EU078624-EU078678 and EU076312-EU076343.

Data analysis

The sequence data was optimised using the software package Seqman from DNAStar Inc. Sequence alignments were performed by using CLUSTAL-X (Thompson et al. 1997) and improved manually. The neighbour-joining (NJ) method was used for the phylogenetic analysis. For NJ analysis, the data were first analysed using the Tamura-Nei parameter distance calculation model with gamma-distributed substitution rates (Tamura & Nei 1993), which were then used to construct the NJ tree with MEGA v. 3.1 (Kumar et al. 2004). To determine the support for each clade, a bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replications.

For parsimony analysis, the PAUP v. 4.0 software was used (Swofford 2002). Alignment gaps were treated as a fifth character state and all characters were unordered and of equal weight. Maximum parsimony analysis was performed for all data sets using the heuristic search option with 100 random taxa additions and tree bisection and reconstruction (TBR) as the branch-swapping algorithm. Branches of zero length were collapsed and all multiple, equally parsimonious trees were saved. The robustness of the trees obtained was evaluated by 1000 bootstrap replications (Hillis & Bull 1993). A Neosartorya fischeri isolate was used as outgroup in these experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phylogeny

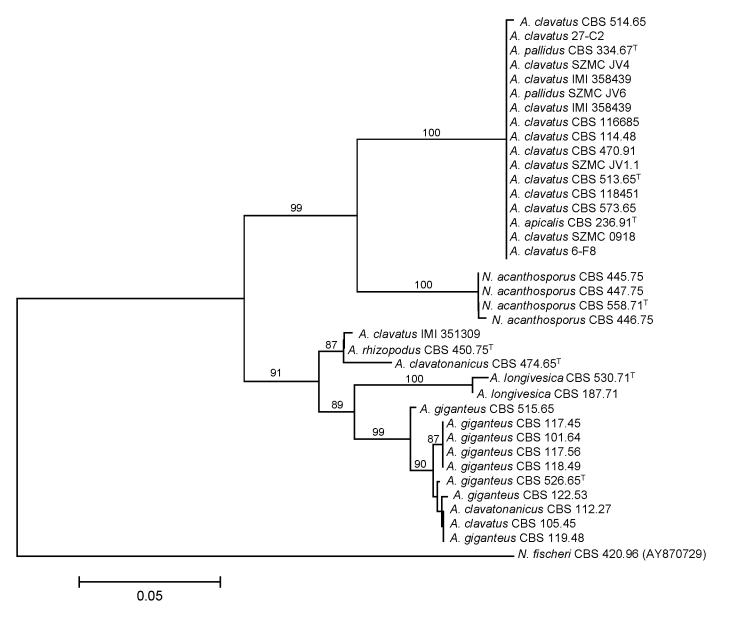

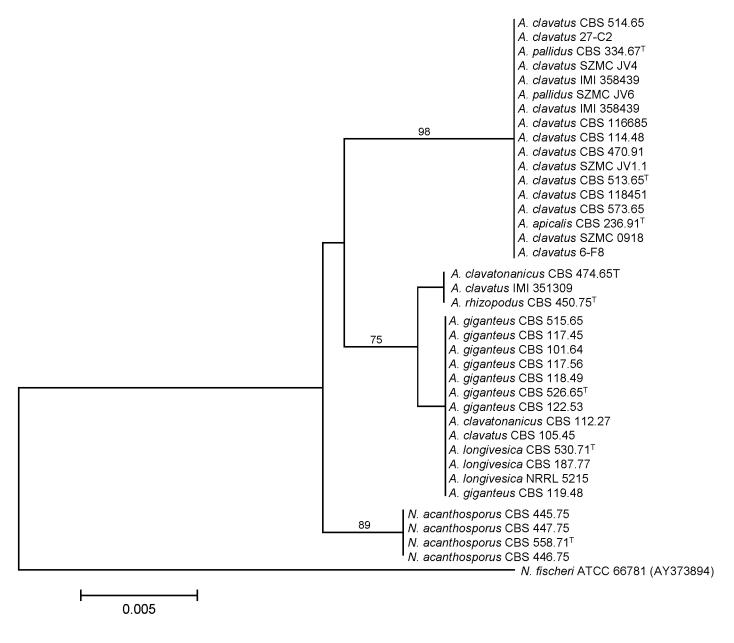

We examined the genetic relatedness of section Clavati isolates and their presumed relatives using sequence analysis of the ITS region of the ribosomal RNA gene cluster, and parts of the calmodulin and β-tubulin genes. During analysis of part of the β-tubulin gene, 468 characters were analyzed. Among the 174 polymorphic sites, 102 were found to be phylogenetically informative. The Neighbour-joining tree based on partial β-tubulin genes sequences is shown in Fig. 1. The topology of the tree is the same as one of the more than 105 maximum parsimony trees constructed by the PAUP program (length: 233 steps, consistency index: 0.8798, retention index: 0.9728). The ITS data set included 448 characters with 8 parsimony informative characters. The Neighbour-joining tree shown in Fig. 2 has the same topology as one of the 4 maximum parsimony trees (tree length: 25, consistency index: 0.9600, retention index: 0.9896).

Fig. 1.

Neighbour-joining tree based on β-tubulin sequence data of Aspergillus section Clavati. Numbers above branches are bootstrap values. Only values above 70 % are indicated.

Fig. 2.

Neighbour-joining tree based on ITS sequence data of Aspergillus section Clavati. Numbers above branches are bootstrap values. Only values above 70 % are indicated.

Phylogenetic analysis of β-tubulin sequence data indicated that Aspergillus section Clavati includes six species, namely: A. clavatus (synonyms: A. pallidus, A. apicalis), A. giganteus, A. longivesica, A. rhizopodus, A. clavatonanicus and N. acanthosporus. Some misidentifications have also been clarified: isolates previously identified as A. clavatus (CBS 105.45) and A. clavatonanicus (CBS 112.27) were found to belong to the A. giganteus species, while one isolate originally identified as A. clavatus (IMI 351309) was found to belong to the A. rhizopodus species. The ITS sequences of A. clavatonanicus and A. rhizopodus isolates, and A. giganteus and A. longivesica isolates, respectively, were identical, indicating their close relationship.

A. ingratus (Yaguchi et al. 1993) was found to be the synonym of H. paradoxus based on sequence data, so it was excluded from section Clavati (data not shown). H. paradoxus isolates are only distantly related to section Clavati, with affinities to some Penicillium species (to be published elsewhere).

Chemotaxonomy

The extrolites produced by species of Aspergillus section Clavati are listed in Table 2. Based on the common production of patulin, tryptoquivalins, tryptoquivalons and kotanins, most of the species appear to be closely related. A. clavatus produces patulin (= clavatin = clavacin) (Weisner 1942; Waksman et al. 1942, 1943; Hooper et al. 1944) and has been reported to cause mycotoxicosis in calves as early as 1954 (Forgacs et al. 1954). This mycotoxin was detected on YES agar in all isolates of A. clavatus, A. giganteus and A. longivesica. Previously the presence of the isoepoxydon dehydrogenase gene taking part in the biosynthesis of patulin has also been proved for A. clavatonanicus and A. pallidus isolates using primer pairs developed by Paterson et al. (2000) to identify potential patulin producing Penicillia (Varga et al. 2003). Other interesting metabolites produced by species of section Clavati are ribotoxins. Ribotoxins are a family of ribosome-inactivating proteins that have specific ribonucleolytic activity against a single phospodiester bond in the conserved sarcin/ricin domain of 26 S rRNA (Martinez Ruiz et al. 1999). Ribotoxins have recently been found in a number of Aspergillus species including A. clavatus, A. giganteus, A. viridinutans, A. fumigatus, A. restrictus, A. oryzae var. effusus, A. tamarii and A. ostianus. Anamorphs of Neosartorya fischeri, N. glabra and N. spinosa also produced ribotoxins (Lin et al. 1994; Martinez-Ruiz et al. 1999). Using the PCR probe developed by Lin et al. (1994), Varga et al. (2003) examined the presence of ribotoxin genes in isolates of Aspergillus section Clavati; a DNA fragment of about 600 bp was amplified in some A. clavatus, A. giganteus, A. pallidus and N. acanthosporus isolates, indicating that these isolates are able to synthesize ribotoxins (Varga et al. 2003). Hemicarpenteles paradoxus, however, including its synonym A. ingratus produces no secondary metabolites in common with these core species and appear to more distantly related to section Clavati. Thus this species appears to occupy a unique position in the Aspergillus genus with no obvious closely related species.

Table 2.

Extrolite production of species assigned to Aspergillus section Clavati and D. cejpii. These toxins were all verified or found for the first time in the species listed, the ribotoxins (including α-sarcin) and xanthocillin X in D. cejpii were not verified, however.

| Species | Extrolites |

|---|---|

| A. clavatonanicus | antafumicins, glyanthrypine, kotanins, tryptoquivalines, tryptoquivalones |

| A. clavatus | patulin, cytochalasin E & K, kotanins, antafumicin, (dehydrocarolic acid), tryptoquivalones, tryptoquivalines, ascladiol, ribotoxins |

| A. giganteus | patulin, antafumicin, ascladiol, tryptoquivalones; tryptoquivalines, glyanthrypine, pyripyropen, α-sarcin and other ribotoxins |

| A. longivesica | patulin, tryptoquivalones, tryptoquivalines, antafumicins, pyripyropen |

| A. rhizopodus | pseurotins, dehydrocarolic acid, tryptoquivalines, tryptoquivalones, kotanins, cytochalasins |

| N. acanthosporus | kotanins, tryptoquivalines, tryptoquivalones, ribotoxins |

| D. cejpii | gliotoxin, tryptoquivalones, rubratoxins, (xanthocillin X) |

Morphology

All the isolates except the ex type culture of A. clavatonanicus, produced numerous conidiophores with blue green conidia, hyaline conidiophore stipes and clavate aspergilla. The isolates in three species were phototropic producing very long conidiophores: A. giganteus, A. rhizopodus and A. longivesica. Another common phenotypic similarity was the alkalophilic tendency already described for A. rhizopodus which was isolated from soil with pH 8.5-9 and other species in the group (Raper & Fennell 1965; Rai et al. 1975). Several species have been isolated from dung which is also an alkaline substrate. This is further confirmed by the strong growth of all isolates on creatine-sucrose agar. This medium has an initial pH of 8 and creatine is an alkaline amino acid. Morphological and physiological data confirmed that Neocarpenteles acanthosporus and Aspergillus section Clavati are closely related.

Teleomorph relationships in Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati

Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati includes section Clavati with the N. acanthosporus teleomorph, and section Fumigati with Neosartorya teleomorphs. We examined the relationships of these teleomorphs taxa to another ascomycete genus, Dichotomomyces. Dichotomomyces cejpii was originally described by Saito (1949) as D. albus, later validated as D. cejpii by Scott (1970). This species belongs to the Trichocomaceae family (although Malloch & Cain (1971) placed it to Onygenaceae). This species is characterised by the production of aleurioconidia on short branched conidiophores, and ascospores embedded in cleithothecia (Scott 1970; Udagawa 1970). Isolates of D. cejpii are highly heat resistant and can be found world-wide in soil, heat treated products and marine environments (Pieckova et al. 1994; Jesenska et al. 1993; Mayer et al. 2007). D. cejpii isolates has been claimed to produce a range of secondary metabolites including gliotoxin (Seigle-Murandi et al. 1990), xanthocillin X (Kitahara & Endo 1981), and several metabolites with antibiotic and ciliostatic properties (Pieckova & Jesenska 1997a, 1997b; Pieckova & Roeijmans 1999).

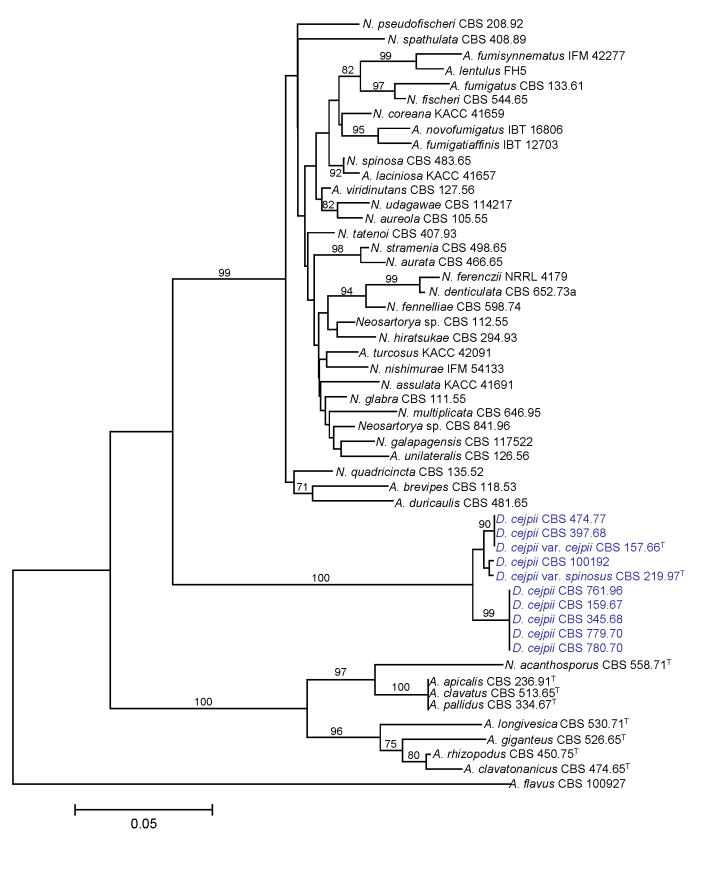

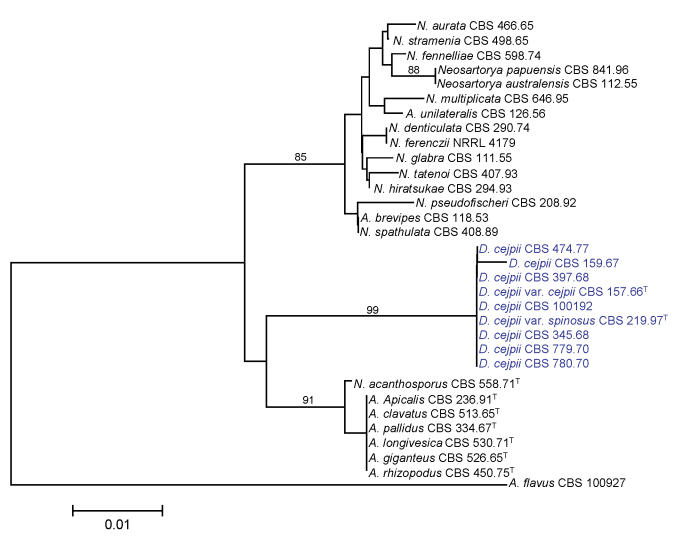

We examined the genetic variability and relationships of Aspergillus section Clavati and Fumigati isolates, D. cejpii var. cejpii and D. cejpii var. spinosus (Malloch & Cain 1971; originally described as D. albus var. spinosus; Udagawa 1970). Both the ITS region and part of the β-tubulin gene were amplified and sequenced, and phylogenetic analyses were carried out as described above. The trees based on both ITS and β-tubulin data indicate that D. cejpii forms a sister group with Neosartorya and Neocarpenteles species (Figs 3-4). During analysis of part of the β-tubulin gene, 469 characters were analyzed. Among the 270 polymorphic sites, 214 were found to be phylogenetically informative. The Neighbour-joining tree based on partial β-tubulin genes sequences is shown in Fig. 3. The topology of the tree is the same as one of the 22 maximum parsimony trees constructed by the PAUP program (length: 738 steps, consistency index: 0.6233, retention index: 0.8614). The ITS data set consisted of 446 nucleotides, with 45 parsimony informative sites. The topology of the Neighbour joining tree depicted in Fig. 4 was the same as one of the more than 105 maximum parsimony trees (length: 124 steps, consistency index: 0.7419, retention index: 0.9229). Both trees indicate that the Dichotomomyces genus should be transferred to Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati. Similar results were obtained during phylogenetic analysis of partial calmodulin gene sequences (data not shown). D. cejpii isolates have been found to produce gliotoxin in common with several species assigned to section Fumigati including some Neosartorya species (Larsen et al. 2007), tryptoquivalones also produced by several species assigned to sections Clavati and Fumigati (Hong et al. 2005), and rubratoxins, which are hepatotoxic mycotoxins produced by P. crateriforme (Frisvad 1989; Sigler et al. 1996; Richer et al. 1997) [misidentified as Penicillium purpurogenum (Natori et al. 1970) or P. rubrum (Moss et al. 1968)]. D. cejpii has also been claimed to produce xanthocillin X (Kitahara & Endo 1981), even though it could not be confirmed in our analyses. Xanthocillin and related compounds have also been found in H. paradoxus (Frisvad JC, unpubl. data) A. candidus (Rahbaek et al. 2000), Eupenicillium crustaceum (Turner & Aldridge 1983), E. egyptiacum (Vesonder 1979), P. italicum (Arai et al. 1989), P. flavigenum (Frisvad et al. 2004) and P. chrysogenum (Hagedorn et al. 1960; Achenbach et al. 1972; Pfeiffer et al. 1972; Frisvad et al. 2004; de la Campa et al. 2007). Since the anamorph of Dichotomomyces was earlier found to belong to Polypaecilum, further morphological and molecular studies are needed to clarify the significance of the morphology of the anamorph in the taxonomic placement of these species, and to clarify the taxonomy of Polypaecilum species.

Fig. 3.

Neighbour-joining tree based on β-tubulin sequence data of Neosartorya, Neocarpenteles, Dichotomomyces species and their asexual relatives. Numbers above branches are bootstrap values. Only values above 70 % are indicated.

Fig. 4.

Neighbour-joining tree based on ITS sequence data of Neosartorya, Neocarpenteles, Dichotomomyces species and their asexual relatives. Numbers above branches are bootstrap values. Only values above 70 % are indicated.

In conclusion, the polyphasic approach applied to clarify the taxonomy of Aspergillus section Clavati led to the assignment of six species, namely: A. clavatus (synonyms: A. pallidus, A. apicalis), A. giganteus, A. longivesica, A. rhizopodus, A. clavatonanicus and N. acanthosporum to this section. Hemicarpenteles paradoxus (synonym: A. ingratus) was found to be unrelated to section Clavati, but more closely related to Penicillium. Dichotomomyces and Neosartorya were found to be sister clades to the genus Neocarpenteles. Further studies are needed to clarify the taxonomic status of Dichotomomyces species with Polypaecilum anamorphs.

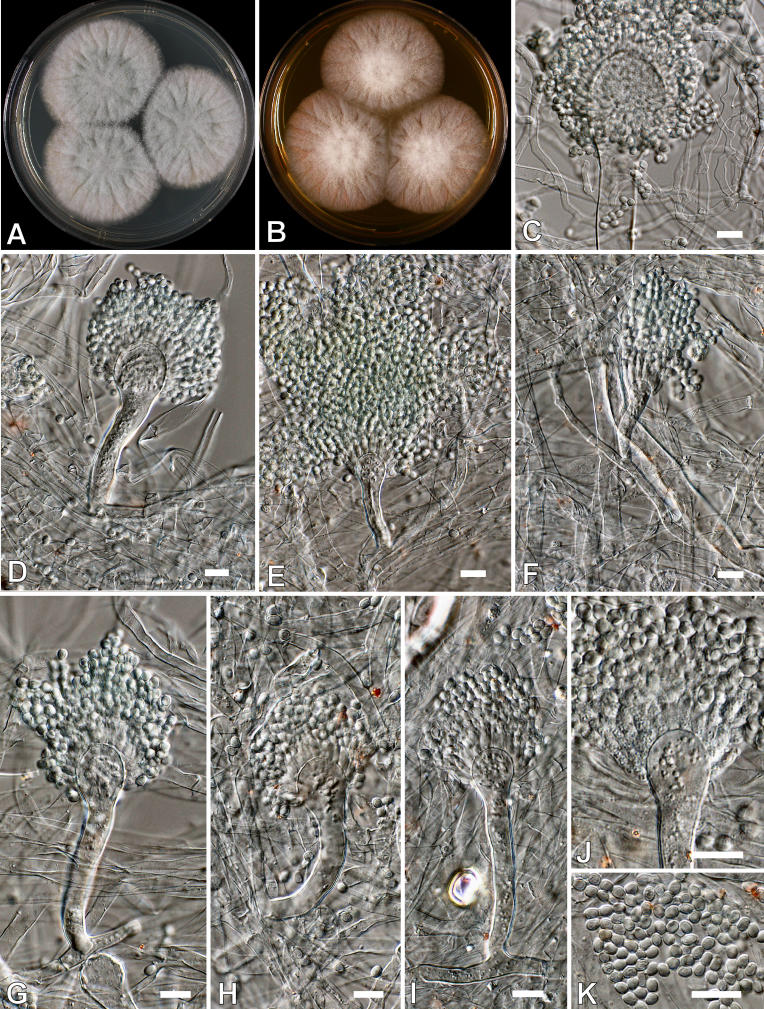

Aspergillus clavatonanicus Batista, Maia & Alecrim, Anais Fac. Med. Univ. Recife 15: 197. 1955. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Aspergillus clavatonanicus. A-B. Colonies after 7 d at 25 °C. A. CYA. B. MEA. C-J. Conidiophores. K. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Type: CBS 474.65, from finger nail lesion, Recife, Brazil

Other no. of the type: ATCC 12413; DMUR 532; IMI 235352; WB 4741

Description

Colony diam (7 d): CYA25: 50-82 mm, MEA25: 45-78 mm, YES25: 57-82 mm, OA25: 49-60 mm, CYA37: 8-17 mm, CREA: very good growth and acid production in the margin of the colony

Colony colour: greyish blue green

Conidiation: abundant

Reverse colour (CZA): uncoloured to light brownish

Colony texture: floccose

Conidial head: clavate, up to 145-360 × 120-180 μm

Stipe: 40-470 × 6-16 μm, rough walled

Vesicle diam/shape: 22-125 × 5-22 μm, clavate

Conidium size/shape/surface texture: 5-8.5 × 5-6.5 μm, ellipsoid or cylindrical, smooth

Cultures examined: CBS 474.65 = IBT 12370 = IBT 24678, CBS 112.27 = IBT 12369 = IBT 24677

Diagnostic features: conidial heads smaller than 1 mm

Similar species: A. clavatus

Distribution: Brazil

Ecology and habitats: human

Extrolites: antafumicins, glyanthrypine, kotanin, tryptoquivalins, tryptoquivalons

Pathogenicity: isolated from nail lesion (Batista et al. 1955)

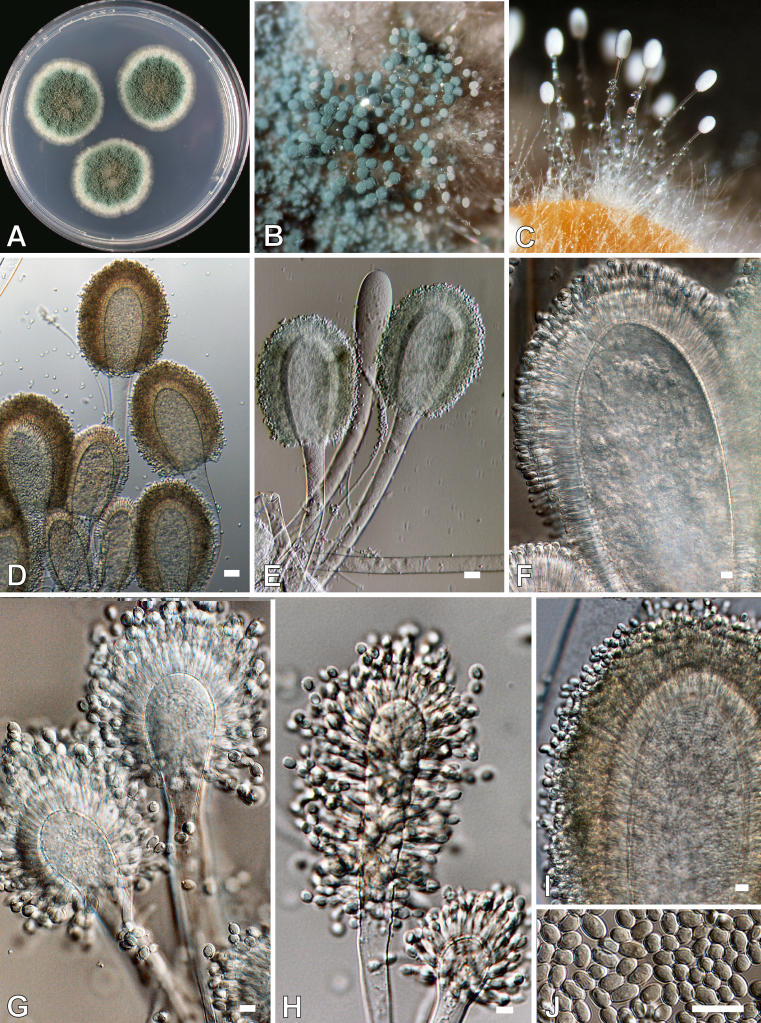

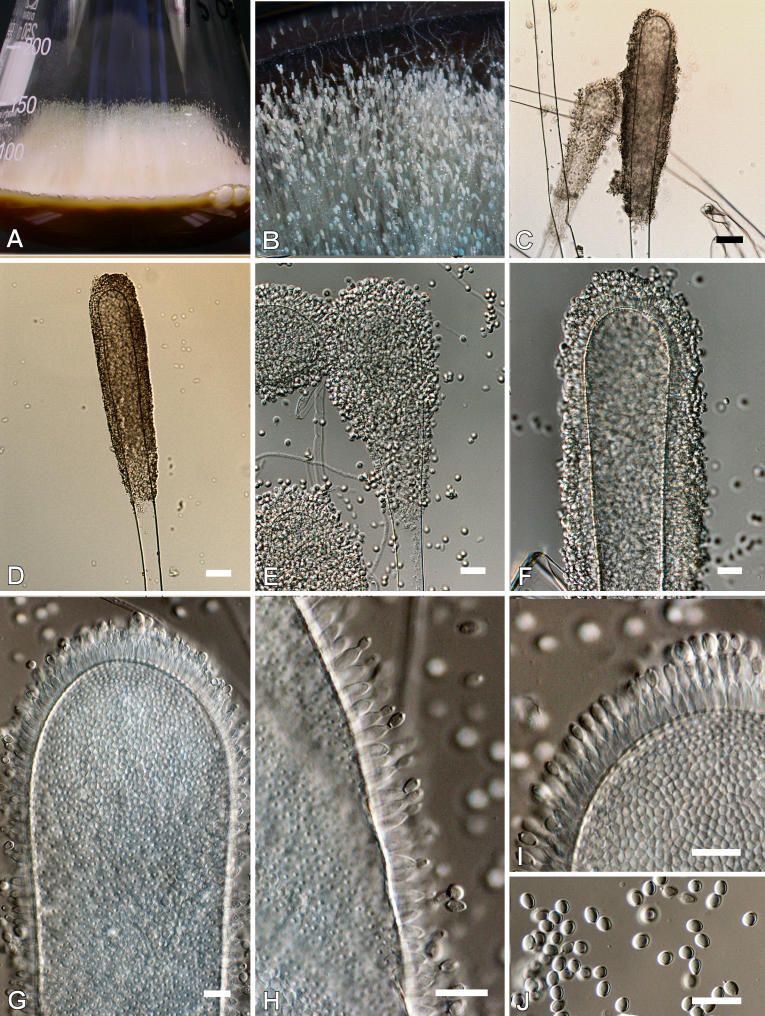

Aspergillus clavatus Desmazières, Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot. 2: 71, 1834. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Aspergillus clavatus. A. Colonies after 7 d at 25 °C on CYA. B-C. Macrophotograph of conidiophores. D-I. Conidiophores. J. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm, except D and E = 30 μm.

= Aspergillus pallidus Kamyschko (1963)

= Aspergillus apicalis Mehrotra & Basu (1976)

Type: CBS 513.65, J. Westerdijk > 1909, C. Thom > NRRL

Other no. of the type: ATCC 1007; ATCC 9602; ATCC 9598; CECT 2674; DSM 816; IMI 015949; IMI 015949v; IMI 015949iv; IMI 015949iii; LSHB Ac86; LSHB Ac95; NCTC 978; NCTC 3887; NRRL 1; NRRL 1656; QM 1276; QM 7404; WB 1

Description

Colony diam (7 d): CYA25: 28-45 mm; MEA25: 25-44 mm, YES25: 29-45 mm, OA25: 31-47 mm, CYA37: 9-26 mm, CREA25: very good growth and moderate to very strong acid production (exceptions: CBS 514.65, NRRL 2, NRRL 8 and NRRL 2254 grow poorly on CREA and produce no or very little acid)

Colony colour: blue-green

Conidiation: abundant

Reverse colour (CZA): uncoloured to somewhat brownish with age in some isolates

Colony texture: velvety

Conidial head: clavate, commonly ranging from 300 to 400 μm by 150 to 200 μm when young, in age commonly splitting into two, three, or more divergent columns

Stipe: 1500-3000 × 20-30 μm

Vesicle diam/shape: 200-250 × 40-60 μm, clavate

Conidium size/shape/surface texture: 3-4.5 × 2.5-3 μm, elliptical, smooth

Cultures examined: CBS 104.45, CBS 105.45, CBS 106.45, CBS 114.48, CBS 513.65, CBS 514.65, CBS 470.91, CBS 116685, CBS 118451, DTO 6-F8, DTO 27-C2, SZMC 0918, SZMC JV4, SZMC JV1.1, IMI 351309, IMI 358435, CBS 117.45, CBS 119.48, CBS 118.49, CBS 122.53, CBS 117.56, CBS 101.64, CBS 515.65, CBS 526.65

Diagnostic features: conidial heads up to 4 mm in size

Similar species: A. clavatonanicus

Distribution: worldwide, mainly in tropical, subtropical and Mediterranean regions

Ecology and habitats: soil, cereals, malt, dung

Extrolites: Patulin, cytochalasin E, kotanins, antafumicin, (dehydrocarolic acid), tryptoquivalone, tryptoquivalines, ascladiol (all found in this study), ribotoxins (Lin et al. 1995, Huang et al. 1997)

Pathogenicity: caused endocarditis (Opal et al. 1986), responsible for an extrinsic allergic alveolitis known as malt worker”s lung (Grant et al. 1976; Lopez-Diaz & Flannigan 1997; Flannigan & Pearce 1994), and various toxic syndromes including neurological disorders (Shlosberg et al. 1991; McKenzie et al. 2004; Loretti et al. 2003; Gilmour et al. 1989; Kellerman et al. 1976) and other mycotoxicosis-related diseases (Byth & Lloyd 1971) observed in animals

Notes: some isolates carry dsRNA mycoviruses 35-40 nm in size (Varga et al. 2003)

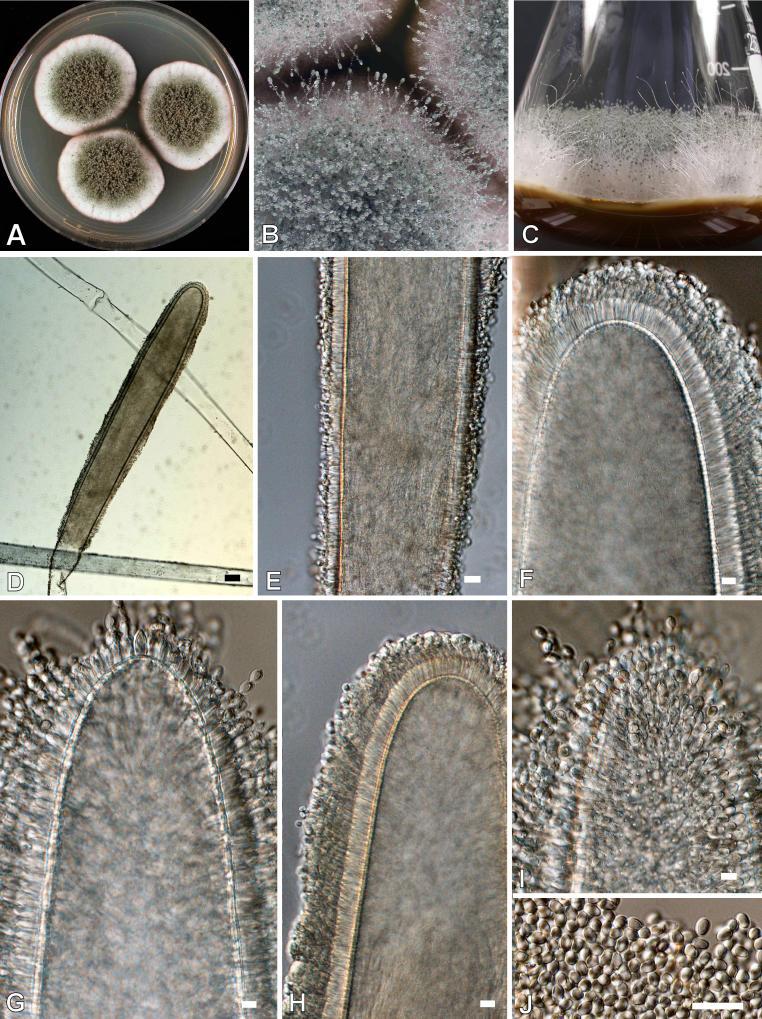

Aspergillus giganteus Wehmer, Mem. Soc. Phys. Genève 33 (2): 85. 1901. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Aspergillus giganteus. A. Colonies after 7 d at 25 °C on CYA. B-C. Macrophotograph of conidiophores. D-I. Conidiophores. J. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm, except D and E = 30 μm.

Type: CBS 526.65, dung of bat in cave, Yucatan, Mexico

Other no. of the type: ATCC 10059; DSM 1146; IFO 5818; IMI 227678; NRRL 10; QM 1970; WB 10; IBT 12368

Description

Colony diam: CYA25: (26-) 40-65 mm, MEA25: (29-) 43-65 mm, YES25: 40-80 mm, OA25: 31-75 mm, CYA37: 10-29 mm, CREA: very good growth and poor or no acid production

Colony colour: first white, becoming pale blue-green near light celandine green to slate-olive

Conidiation: usually abundant

Reverse colour (CZA): dull tan

Colony texture: velvety

Conidial head: splitting into 2 or more columns with age, blue green

Stipe: two types: 2-3(-4) mm; or several cm in length

Vesicle diam/shape: two types: 100-250 × 30-50 μm on short conidiophores, 400-600 × 120-180 μm on long ones, clavate

Conidium size/shape/surface texture: 3.5-4.5 × 2.4-3 μm, elliptical, thick-walled, smooth

Cultures examined: CBS 117.45, CBS 119.48, CBS 118.49, CBS 122.53, CBS 117.56, CBS 101.64, CBS 515.65

Diagnostic features: produces clavate vesicles in contrast with the elongate ones of A. longivesica; do not produce rhizoidal foot cells characteristic to A. rhizopodus; conidial heads can be up to 1-5 cm long

Similar species: A. rhizopodus, A. longivesica

Distribution: Nigeria, U.S.A., Egypt, Mexico, Panama, Germany, Suriname, Netherlands, Poland

Ecology and habitats: dung, soil, wood

Extrolites: patulin, antafumicin, ascladiol, tryptoquivalone; tryptoquivalines, glyanthrypine, pyripyropen (found in this study), α-sarcin and other ribotoxins (Olson & Goerner 1965; Olson et al. 1965; Lin et al. 1995; Wirth et al. 1997; Martinez-Ruiz et al. 1999). Carotens are also produced (van Eijk et al. 1979)

Pathogenicity: not reported

Note: two types of conidial structures: (1) conidiophores commonly 2 to 3 mm, rarely exceeding 4 mm in height, bearing clavate heads 200 to 350 μm in length; (2) conidiophores one to several centimeters in length, bearing heads up to 1 mm in length; longer conidiophores are phototropic, and only elongate in the presence of light

Aspergillus longivesica Huang & Raper, Mycologia 63(1): 53. 1971. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Aspergillus longivesica. A. Colonies after 10 d at 25 °C on CYA. B-C. Macrophotograph of conidiophores. D-I. Conidiophores. J. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm, except D and E = 30 μm.

Type: CBS 530.71, from soil, rain forest, Nigeria

Other no. of the type: ATCC 22434; IMI 156966; QM 9698

Description

Colony diam: CYA25: 31-51 mm; MEA25: 48-56 mm; YES25: 60-74 mm; OA25: 52-60 mm, CYA37: 0 mm, CREA25: weak growth and no acid production (CBS 187.77 grow very well on CREA, however)

Colour: white to cream

Conidiation: abundant, rarely less abundant

Reverse colour (CYA): pale cinnamon buff

Colony texture: thin floccose

Conidial head: elongate, splitting into divergent columns with age, greyish blue green

Stipe: two types: 80-420 × 7-11.2 μm, or 1.5-4.5 cm long, thick walled (5.6-7 μm)

Vesicle diam/shape: two types: 2.2-3.2 mm × 130-200 μm, elongate, clavate, thick-walled, or 18-36 μm, globose to flask-shaped, thin-walled

Conidia length/shape/surface texture: two types: 4.2-16.8 × 2.8-7 μm, globose to elliptical, or 3.5-5.2 × 2.5-3.5 μm, elliptical or pyriform

Cultures examined: CBS 530.71, CBS 187.77

Diagnostic features: produces longer and wider conidiophores, longer vesicles and larger conidia than A. giganteus; vesicles are elongate to fusoid-clavate for the long conidiophre and globose for the samml ones, while those of A. giganteus are clavate

Similar species: A. giganteus

Distribution: Nigeria, Ivory Coast

Ecology and habitats: soil

Extrolites: patulin, tryptoquivalone, tryptoquivalines, antafumicins, pyripyropens (found in this study)

Pathogenicity: not reported

Note: longer conidiophores are phototropic, and only elongate in the presence of light

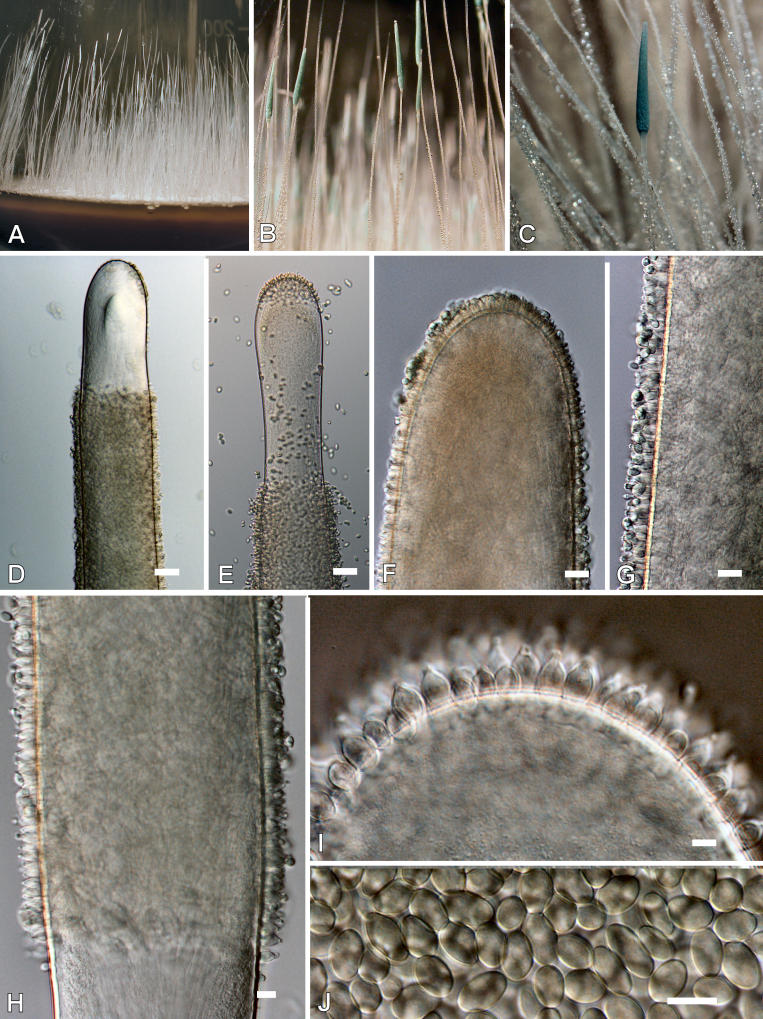

Aspergillus rhizopodus Rai, Wadhwani & Agarwal, Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 64: 515. 1975. Fig. 9

Fig. 9.

Aspergillus rhizopodus. A. Colonies after 10 d at 25 °C on CYA. B. Macrophotograph of conidiophores. C-I. Conidiophores. J. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm, except D and E = 30 μm.

Type: CBS 450.75, from usar soil, Lucknow, India

Other no. of the type: IMI 385057; WB5442

Description

Colony diam (7 d): CZA30: 40 mm; CYA25: 38-42 mm; MEA25: 50-55 mm; YES25: 68-72 mm; OA25: 43-47 mm; CYA37: 17-19 mm; CREA25: rather good growth and no acid production

Colony colour: blue green

Conidiation: abundant

Reverse colour (CZA): colourless

Colony texture: slightly furrowed

Conidial head: short columnar

Stipe: two types: 208-800 × 11-32 μm, or 5-22 mm × 36 μm, thick walled, smooth

Vesicle diam/shape: two types: 40-176 × 11-32 μm, or 288 × 79 μm, clavate

Conidium size/shape/surface texture: 4-5.5 × 2.5-3 μm, ellipsoidal, smooth

Cultures examined: CBS 450.75, IMI 351309

Diagnostic features: produces variously shaped foot cells with finger-like projections

Similar species: A. giganteus, A. longivesica

Distribution: India, Yugoslavia

Ecology and habitats: soil

Extrolites: pseurotins, dehydrocarolic acid, tryptoquivalines, tryptoquivalones, kotanins and cytochalasin (found in this study)

Pathogenicity: not reported

Note: large conidial heads formed only in the presence of light

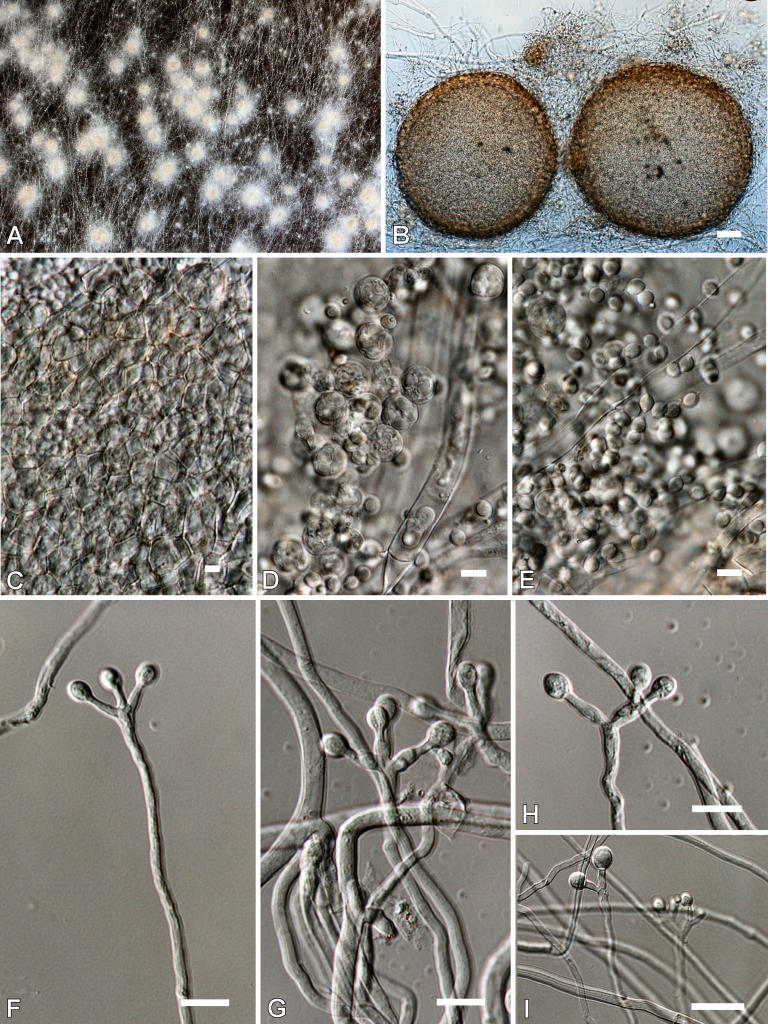

Dichotomomyces cejpii (Milko) D.B. Scott, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 47: 428, 1970. Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Dichotomomyces cejpii. A-B. Ascomata on MEA after 10 d at 25 °C. C. Ascomata wall. D-E. Asci and ascospores. F-I conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm, except B and C = 30 μm.

= Talaromyces cejpii Milko (1964)

= Dichotomomycs albus Saito (1949)

= Royella albida Dwiveli (1960)

Type: CBS 157.66, from orchard soil, near Tiraspol, Moldova

Description

Colony diam (7 d): CYA25: 25-47 mm; MEA25: 35-58 mm; YES25: 47-50 mm; OA25: 38-48; CYA37: 24-32 mm; CREA: poor growth and noa cid production

Colony colour: white to cream coloured

Conidiation: sparse

Reverse colour (CZA):

Colony texture: floccose, granular

Conidium size/shape/surface texture: 5-10 μm, subglobose to pyriform, smooth

Homothallic

Cleistothecia: variable in size, spherical, white to cream coloured

Ascospores: 3-3.5 × 4-4.5 μm, lenticular, with two closely appressed very thin equatorial crests and convex walls smooth

Cultures examined: CBS 761.96, CBS 779.7, CBS 219.67, CBS 100192, CBS 474.77, CSB 780.70, CBS 397.68, CBS 345.68, CBS 159.67, CBS 157.66, CBS 212.50

Diagnostic features: conidiophore apices are dichotomously branched, and conidia are produced from these branches (Polypaecilum anamorph); racquet hyphae are frequently produced; vegetative hyphae often bear rhizomorphs

Similar species: -

Distribution: Slovakia, Netherlands, Egypt, U.S.A., South Africa, Pakistan, Japan, Moldova, India

Ecology and habitats: soil, compost, pasteurised products

Extrolites: gliotoxin (Seigle-Murandi et al. 1990, confirmed in this study), tryptoquivalons (found in this study), rubratoxins (found in this study), xanthocillin X (Kitahara & Endo 1981; could not be confirmed in this study), and several metabolites with antibiotic and ciliostatic properties (Pieckova & Roeijmans 1999; Pieckova & Jesenska 1997a, 1997b)

Pathogenicity: not reported

Note: this species is reported as a heat resistant fungus causing food spoilage (Pieckova et al. 1994; Jesenska et al. 1993; Mayer et al. 2007)

Neocarpenteles acanthosporus (Udagawa & Takada) Udagawa & Uchiyama [anamorph: A. acanthosporus Udagawa & Takada], Mycoscience 43(1): 4. 2002.

= Hemicarpenteles acanthosporus Udagawa & Takada (1971)

Type: CBS 558.71, from soil, Bougainville Island (Solomon Islands), Papua New Guinea

Other no. of the type: ATCC 22931; IMI 164621; NHL 2462

Description

Colony diam (7 d): CYA25: 37-47 mm; MEA25: 72-85: mm; YES25: 62-82; OA25: 40-49 mm; CYA37: 0 mm; CREA: poor growth and no acid production

Colour: white to brownish orange

Conidiation: sparse

Reverse colour (CYA): greyish-orange

Colony texture: floccose

Conidial head: radiate to loosely columnar

Stipe: (50-)100-400 × 5-12 μm, smooth, septate

Vesicle diam/shape: 10-26 μm, flask shaped

Conidia length/shape/surface texture: 4.5-7 μm, globose to subglobose, spinulose

Homothallic

Cleistothecia: 350-1000 × 250-850 μm, sclerotioid, subglobose to ovoid, fawn, covered with dense aerial hyphae

Ascospores: 4-4.5 × 3.5-4 μm, lenticular, with two thin equatorial crests and convex walls ornamented with raised flaps

Cultures examined: CBS 558.71, CBS 445.75, CBS 446.75, CBS 447.75

Diagnostic features: small dull green readiate conidial heads, short conidiophores with small flask-shaped vesicle, production of ascospores, and large globose conidia distinguish this species from other members of section Clavati

Distribution: Papua New Guinea (Bougainville Island), Japan

Ecology and habitats: soil

Extrolites: kotanins, tryptoquivalines, tryptoquivalones (found in this study), ribotoxins (Varga et al. 2003). (+)-isoepoxydon has also been reported (Kontani et al. 1990)

Pathogenicity: not reported

Note: not illustrated here, for detailed description and illustration see Udagawa & Takada (1971); no growth at 37 °C

Acknowledgments

We thank Ellen Kirstine Lyhne for technical assistance and the Danish Technical Research Council for financial support to Programme for Predictive Biotechnology.

References

- Achenbach H, Strittmatter H, Kohl W (1972). Die Strukturen der Xanthocilline Y1 und Y2. Chemisches Berichte 105: 3061-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, Miyajima H, Mushiroda T, Yamamoto Y (1989). Metabolites of Penicillium italicum Wehmer: isolation and structures of new metabolites including naturally occurring 4-ylideneacyltetronic acids, italicinic acid and italicic acid. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 37: 3229-3235. [Google Scholar]

- Batista AC, Maia HS, Alecrim IC (1955). Onicomicose produizida por “Aspergillus clavato-nanica” n. sp. Anais da Faculdade de Medecina da Universidade do Recife 15: 197-203. [Google Scholar]

- Bergel F, Klein R, Morrison AL, Mioss AR, Rindetrknect H, Ward JL (1943) An antibacterial substance from Aspergillus clavatus and Penicillium claviforme and its probable identity with patulin. Nature 152: 750. [Google Scholar]

- Bergel F, Morrison AL, Moss AR, Rinderknecht H (1944) An antibacterial substance from Aspergillus clavatus. Journal of the Chemical Society 1944: 415-421. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta B, Gaiaschi A, Galli CL, Restani P (2000). Patulin in apple-based foods: occurrence and safety evaluation. Food Additives and Contaminants 17: 399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth W, Lloyd MM (1971). Granulomatous and mycotoxic syndromes in mice due to Aspergillus clavatus Desm. Sabouraudia 9: 263-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchi G, Luk KC, Kobbe B, Townsend JM (1977). Four new mycotoxins from Aspergillus clavatus related to tryptoquivaline. Journal of Organic Chemistry 42: 244-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa R de la, Seifert K, Miller JD (2007). Toxins from strains of Penicillium chrysogenum isolated from buildings and other sources. Mycopathologia 163: 161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clardy J, Springer JP, Büchi G, Matsuo K, Wrightman R (1975). Tryptoquivaline and tryptoquivalone, two new tremorgenic metabolites of Aspergillus clavatus. Journal of the American Chemical Society 97: 663-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RJ, Cox RH (1981). Handbook of toxic fungal metabolites. New York: Academic Press.

- Demain AL, Hunt NA, Malik V, Kobbe B, Hawkins H, Matsuo K, Wogan GN (1976). Improved procedure for production of cytochalasin E by Aspergillus clavatus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 31: 138-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijk GW van, Mummery RS, Roeymans HJ, Valadon LRG (1979). A comparative study of carotenoids of Aschersonia aleyroides and Aspergillus giganteus. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 83: 191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell DI, Raper KB (1955). New species and varieties of Aspergillus. Mycologia 47: 68-89. [Google Scholar]

- Filtenborg O, Frisvad JC, Svendsen JA (1083). Simple screening method for molds producing intracellular mycotoxins in pure culture. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 45: 581-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannigan B, Pearce AR (1994). Aspergillus spoilage: spoilage of cereals and cereal products by the hazardous species Aspergillus clavatus. In: The genus Aspergillus. From taxonomy and genetics to industrial application. (Powell, KA, Renwick A, Peberdy JF, eds). New York. Plenum Press: 55-62.

- Florey HW, Jennings MA, Philpot FJ (1944). Claviformin from Aspergillus giganteus Wehm. Nature 153: 139. [Google Scholar]

- Forgacs J, Carll WT, Herring AS, Mahlandt BG (1954). A toxic Aspergillus clavatus isolated from feed pellets. American Journal of Hygiene 60: 15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad JC (1989) The connection between the Penicillia and aspergilli and mycotoxins with special emphasis on misidentified isolates. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 18: 452-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad JC, Smedsgaard J, Larsen TO, Samson RA (2004). Mycotoxins, drugs and other extrolites produced by species in Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. Studies in Mycology 49: 201-241. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad JC, Thrane U (1987). Standardized high performance liquid chromatography of 182 mycotoxins and other fungal metabolites based on alkylphenone retention indices and UV-VIS spectra (diode array detection). Journal of Chromatography A 404: 195-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad JC, Thrane U (1993). Liquid chromatography of mycotoxins. In: Betina V (ed.). Chromatography of mycotoxins: techniques and applications. Journal of Chromatography Library 54 Amsterdam: Elsevier: 253-372. [Google Scholar]

- Gams W, Christensen M, Onions AH, Pitt JI, Samson RA (1985). Infrageneric taxa of Aspergillus. In: Advances in Penicillium and Aspergillus Systematics. Samson RA, Pitt JI, eds. New York: Plenum Press: 55-62.

- Gilmour JS, Inglis DM, Robb J, Maclean M (1989). A fodder mycotoxicosis of ruminants caused by contamination of a distillery by-product with Aspergillus clavatus. The Veterinary Record 124: 133-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass NL, Donaldson GC (1995). Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and Environrnental Microbiology 61: 1323-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant IW, Blackadder ES, Greenberg M, Blyth W (1976). Extrinsic allergic alveolitis in Scottish maltworkers. British Medical Journal 1: 490-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn I, Eholzer U, Luttringhaus A (1960). Beiträge zur Konstitutionsermittlung des Antibiotikums Xanthocillin. Chemisches Berichte 93: 1584-1590. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MA (1989). Presence and stability of patulin in apple products: a review. Journal of Food Protection 9: 147-153. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ (1993). An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic Biology 42: 182-192. [Google Scholar]

- Hong SB, Cho HS, Shin HD, Frisvad JC, Samson RA (2006). Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 56: 477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SB, Go SJ, Shin HD, Frisvad JC, Samson RA (2005). Polyphasic taxonomy of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Mycologia 97: 1316-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper IR, Anderson HW, Skell P, Carter HE (1944). The identity of clavacin with patulin. Science 99: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KC, Hwang YY, Hwu L, Lin A (1997). Characterization of a new ribotoxin gene (c-sar) from Aspergillus clavatus. Toxicon 35: 383-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LH, Raper KB (1971). Aspergillus longivesica, a new species from Nigerian soil. Mycologia 63: 50-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesenska Z, Pieckova E, Bernat D (1993). Heat resistance of fungi from soil. International Journal of Food Microbiology 19: 187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman TS, Pienaar JG, van der Westhuizen GC, Anderson GC, Naude TW (1976). A highly fatal tremorgenic mycotoxicosis of cattle caused by Aspergillus clavatus. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 43: 147-154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara N, Endo A (1981). Xanthocillin X monomethyl ether, a potent inhibitor of prostaglandin biosynthesis. Journal of Antibiotics (Tokyo) 34: 1556-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontani M, Fukushima Y, Sakagami Y, Marumo S (1990). Inhibitors of β-glucan biosynthesis in fungal metabolites. Tennen Yuki Kagobutsu Toronkai Koen Yoshishu 32: 103-110. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M (2004). MEGA3: Integrated Software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and Sequence Alignment. Briefings in Bioinformatics 5: 150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TO, Smedsgaard J, Nielsen KF, Hansen MA, Samson RA, Frisvad JC (2007). Production of mycotoxins by Aspergillus lentulus and other medically important and closely related species in section Fumigati. Medical Mycology 45: 225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Huang K, Hwu L, Tzean SS (1994). Production of type II ribotoxins by Aspergillus species and related fungi in Thailand. Toxicon 33: 105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Diaz TM, Flannigan B (1997). Production of patulin and cytochalasin E by Aspergillus clavatus during malting of barley and wheat. International Journal of Food Microbiology 35: 129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretti AP, Colodel EM, Driemeier D, Correa AM, Bangel JJ Jr, Ferreiro L (2003). Neurological disorder in dairy cattle associated with consumption of beer residues contaminated with Aspergillus clavatus. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 15: 123-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloch D, Cain RF (1971). New genera of Onygenaceaae. Canadian Journal of Botany 49: 839-846. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ruiz A, Kao R, Davies J, Martínez del Pozo A (1999). Ribotoxins are a more widespread group of proteins within the filamentous fungi than previously believed. Toxicon 37: 1549-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KM, Ford J, Macpherson GR, Padgett D, Volkmann-Kohlmeyer B, Kohlmeyer J, Murphy C, Douglas SE, Wright JM, Wright JLC (2007). Exploring the diversity of marine-derived fungal polyketide synthases. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 53: 291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie RA, Kelly MA, Shivas RG, Gibson JA, Cook PJ, Widderick K, Guilfoyle AF (2004). Aspergillus clavatus tremorgenic neurotoxicosis in cattle fed sprouted grains. Austalian Veterinary Journal 82: 635-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrothra BS, Basu M (1976). Some interesting new isolates of Aspergillus from stored wheat. Nova Hedwigia 27: 597-607. [Google Scholar]

- Moss MO, Robinson FV, Wood AB (1968). Rubratoxin B, a toxic metabolite of Penicillium rubrum. Chemistry & Industry 18: 587-588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natori S, Sakaki S, Kurata H, Udagawa SI, Ichinoe M (1970). Production of rubratoxin B by Penicillium purpurogenum Stoll. Applied Microbiology 19: 613-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson BH, Goerner GL (1965). Alpha sarcin, a new antitumor agent. I. Isolation, purification, chemical composition, and the identity of a new amino acid. Applied Microbiology 13: 314-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson BH, Jennings JC, BH, Roga V, Junek AJ, Schuurmans DM (1965). Alpha sarcin, a new antitumor agent. II. Fermentation and antitumor spectrum. Applied Microbiology 13: 322-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, Reller LB, Harrington G, Cannady P Jr (1986). Aspergillus clavatus endocarditis involving a normal aortic valve following coronary artery surgery. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 8: 781-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson RRM, Archer S, Kozakiewicz Z, Lea A, Locke T, O”Grady E (2000). A gene probe for the patulin metabolic pathway with potential for use in patulin and novel disease control. Biocontrol Science and Technology 10: 509-512. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SW (2000). Phylogenetic relationships in Aspergillus based on rDNA sequence analysis. In: Integration of modern taxonomic methods for Penicillium and Aspergillus classification. (Samson RA, Pitt JI, eds). Amsterdam. Harwood Academic Publishers: 323-355.

- Pfeiffer S, Bar H, Zarnack J (1972) Über Stoffwechselprodukte der Xanthocillin-bildende Mutante der Penicillium notatum Westl. Pharmazie 27: 536-542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieckova E, Bernat D, Jesenska Z (1994). Heat resistant fungi isolated from soil. International Journal of Food Microbiology 22: 297-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieckova E, Jesenska Z (1997a). Dichotomomyces cejpii - some characteristics of strains isolated from soil in the Slovak Republic. Czech Mycology 49: 229-237. [Google Scholar]

- Pieckova E, Jesenska Z (1997b). Toxinogenicity of heat-resistant fungi detected by a bio-assay. International Journal of Food Microbiology 36: 227-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieckova E, Roeijmans H (1999). Antibiotic secondary metabolites of Dichotomomyces cejpii. Mycopathologia 146: 121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbaek L, Frisvad JC, Christophersen C (2000). An amendment of Aspergillus section Candidi based on chemotaxonomical evidence. Phytochemistry 53: 581-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai JN, Wadhwani K, Agarwal SC (1975). Aspergillus rhizopodus sp.nov. from Indian alkaline soils. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 64: 515-517. [Google Scholar]

- Raper KB, Fennell DI (1965). The genus Aspergillus. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Richer L, Sigalet D, Kneteman N, Joens A, Scott RB, Asgbourne R, Sigler L, Frisvad J, Smith L (1997). Fulminant hepatic failure following ingestion of mouldy homemade rhubard wine. Gastenterology 112: A1366. [Google Scholar]

- Saito K (1949). Studies on the fungi in the Orient. Journal of Fermentation Technology 27: 120-122. [Google Scholar]

- Samson RA (1979). A compilation of the aspergilli described since 1965. Studies in Mycology 18: 1-38. [Google Scholar]

- Samson RA, Hoekstra ES, Frisvad JC (eds) (2004). Introduction to food and airborne fungi. 7th ed. Utrecht: Centraal Bureau voor Schimmelcultures.

- Sarbhoy AK, Elphick JJ (1968). Hemicarpenteles paradoxus gen. & sp. nov.: The perfect state of Aspergillus paradoxus. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 51: 155-157. [Google Scholar]

- Scott DB (1970). Dichotomomyces cejpii (Milko) comb. nov. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 55: 313-316. [Google Scholar]

- Seigle-Murandi F, Krivobok S, Steiman R, Marzin D (1990). Production, mutagenicity, and immunotoxicity of gliotoxin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 38: 1854-1856. [Google Scholar]

- Shlosberg A, Zadikov I, Perl S, Yakobson B, Varod Y, Elad D, Rapoport E, Handji V (1991). Aspergillus clavatus as the probable cause of a lethal mass neurotoxicosis in sheep. Mycopathologia 114: 35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigler L, Abbott SP, Frisvad JC (1996). Rubratoxin mycotoxicosis by Penicillium crateriforme following ingestion of homemade rhubarb wine. Abstracts, 96th ASM, New Orleans. F-22, p. 77.

- Smedsgaard J (1997). Micro-scale extraction procedure for standardized screening of fungal metabolite production in cultures. Journal of Chromatography A 760: 264-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn PS, van Heerden FR, Rabie CJ (1982). Cytochalasins E and K, toxic metabolites from Aspergillus clavatus. Journal of the Chemical Society Perkin Transactions I 1982: 541-544. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Takeda M, Tanabe H (1971). A new mycotoxin produced by Aspergillus clavatus. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 19: 1786-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford T (2000). PAUP: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony. v. 4.0. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

- Tamura K, Nei M (1993). Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 10: 512-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Hamamoto M, Cañete-Gibat CF, Sugiyama J, Nakase T (1999). Genetic relatedness among species in Aspergillus section Clavati as measured by electrophoretic comparison of enzymes, DNA base composition, and DNA-DNA hybridization. Journal of General and Applied Microbiology 45: 77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom C, Church MB (1926). The aspergilli. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997). The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research 25: 4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinci APJ, Banbury GH (1967). A study of the growth of the tall conidiophores of Aspergillus giganteus. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 50: 525-538. [Google Scholar]

- Turner WB, Aldridge DC (1983). Fungal Metabolites II. London: Academic Press.

- Udagawa S (1970). Notes on some Japanese Ascomycetes IX. Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan 10: 103-109. [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa S, Takada M (1971). Mycological reports from New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. 10. Soil and coprophilous microfungi. Bulletin of the National Science Museum Tokyo 14: 501-546. [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa S, Uchiyama S (2002). Neocarpenteles: a new ascomycete genus to accommodate Hemicarpenteles acanthosporus. Mycoscience 43: 3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Varga J, Rigó K, Molnár J, Tóth B, Szencz S, Téren J, Kozakiewicz Z (2003). Mycotoxin production and evolutionary relationships among species of Aspergillus section Clavati. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 83: 191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesonder RF (1979). Xanthocillin, a metabolite of Eupenicillium egyptiacum NRRL 1022. Journal of Natural Products 42: 232-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman SA, Horning ES, Spencer EL (1942). The production of two antibacterial substances, fumigacin and clavacin. Science 96: 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman SA, Horning ES, Spencer EL (1943). Two antagonistic fungi, Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus clavatus, and their antibiotic substances. Journal of Bacteriology 45: 233-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner BP (1942). Bactericidal effects of Aspergillus clavatus. Nature 149: 356. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocols: A guide to methods and applications. (Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, eds). New York: Academic Press: 315-322.

- Wirth J, Martinez del Pozo A, Mancheno JM, Martinez-Ruiz A, Lacadena J, Onaderra M, Gavilanes JG (1997). Sequence determination and molecular characterization of gigantin, a cytotoxic protein produced by the mould Aspergillus giganteus IFO 5818. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 343: 188-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi T, Someya A, Miyadoh S, Udagawa S (1993). Aspergillus ingratus, a new species in Aspergillus section Clavati. Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan 34: 305-310. [Google Scholar]