Abstract

Background

Xenotransplantation holds the promise of providing an unlimited supply of donor organs for terminal patients with organ failure. Pre-existing natural antibodies to the Galα1,3Galβ1,4GlcNac-R (αGal) carbohydrate xenoantigen, however, bind rapidly to the graft endothelium and initiate hyperacute rejection of wild type pig grafts in humans. Experimental procedures designed to prevent xenoantibody-mediated rejection have been tested in gal knockout mice. These mice produce anti-gal xenoantibodies and are widely used as small animal models for xenotransplantation research. In this model, chimerism for cells expressing the gal carbohydrate can be achieved by transplantation of mixed cells or by transduction of bone marrow cells with viral vectors expressing a functional α1,3 galactosyltransferase gene. Chimerism induces tolerance to heart grafts expressing αGal. The mechanisms by which tolerance is achieved include systemic changes such as clonal deletion and/or anergy. Intragraft changes that occur during the early stages of tolerance induction have not been characterized.

Results

Cytoprotective genes heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), Bcl2, and A20 that have been reported to contribute to long-term graft survival in various models of accommodation were not expressed at high levels in tolerant heart grafts. Intragraft gene expression at both early (Day 10) and late (>2 month) time points after heart transplant were examined by real-time PCR and microarray analysis was used to identify changes associated with the induction of tolerance. Intragraft gene expression profiling using microarray analysis demonstrated that genes identified in the functional categories of stress and immunity and signal transduction were significantly up-regulated in early tolerant grafts compared with syngeneic control grafts. Biological process classification showed lower binomial p-values in the categories of "response to biotic stimulus, defense response, and immune response" suggesting that up-regulated genes identified in these grafts promote survival in the presence of an immune response. The expression of the incompatible carbohydrate antigen (αGal) was reduced by 2 months post-transplant when compared with the expression of this gene at Day 10 post-transplant. These results suggest that the gal carbohydrate antigen is downmodulated over time in grafts that demonstrate tolerance.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that tolerance is associated with intragraft gene expression changes that render the heart resistant to immune-mediated rejection. Genes associated with stress and immunity are up-regulated, however cytoprotective genes HO-1, Bcl2 and A20 were not up-regulated. The expression of the gal carbohydrate, the key target initiating an immune response in this model, is down-regulated in the post-transplant period.

Background

The use of pigs as organ donors could potentially provide an unlimited supply of organs for patients with end-stage organ failure. The Galα1,3Galβ1,4GlcNac-R (αGal) carbohydrate expressed on wild type pig organs, however, initiates the rapid rejection of these grafts [1]. The α1,3 galactosyltransferase (GalT) knockout model (GalT-/-) in mice provides a unique system in which to study the immunological events associated with the rejection of cells or organs expressing the gal carbohydrate [2]. Several promising therapies designed to prevent graft rejection have been studied in this model, including the induction of chimerism to achieve transplant tolerance [3]. Mixed chimerism, acquired by transplantation of the donor's bone marrow cells into the recipient, results in tolerance to xenoreactive T cells as well as B cells [4]. Molecular chimerism, acquired by transplantation of transduced, autologous cells expressing a new gene has also been successfully applied to achieve tolerance [5]. Our group has focused on the use of gene therapy using lentiviral vectors to express the porcine α1,3 galactosyltransferase gene and establish a state of chimerism as a means of achieving transplant tolerance [6-8]. Irrespective of the methodology applied to establish chimerism prior to transplantation, receptor editing and/or clonal deletion play a role in the induction of tolerance [7,9,10]. In accommodation models, in which a transplanted organ may survive continuously in the presence of anti-graft antibodies and complement that might otherwise cause rejection, systemic events as well as intragraft gene expression changes have been shown to contribute to prolonged graft survival [11]. Cytoprotective genes are induced during accommodation and protect the grafts by blocking the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and preventing apoptosis [12,13]. Intragraft gene expression changes associated with the induction of transplant tolerance are less well-characterized and may differ between models [14-18]. The development of gene expression profiling using microarrays has now provided a technologically sophisticated means of studying intragraft gene expression profiles in tolerant and/or rejected grafts [19-25]. Identification of distinct patterns of gene expression changes in graft biopsies may be useful in predicting graft outcome.

In this manuscript, early intragraft gene expression changes associated with the induction of chimerism and tolerance are identified. We demonstrate that expression of cytoprotective genes, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), Bcl2, and A20, do not play a role in tolerance induction in this model. This new information can be used to compare early gene expression profiles associated with various models of tolerance induction with the goal of identifying common intragraft gene expression changes that promote graft survival.

Results

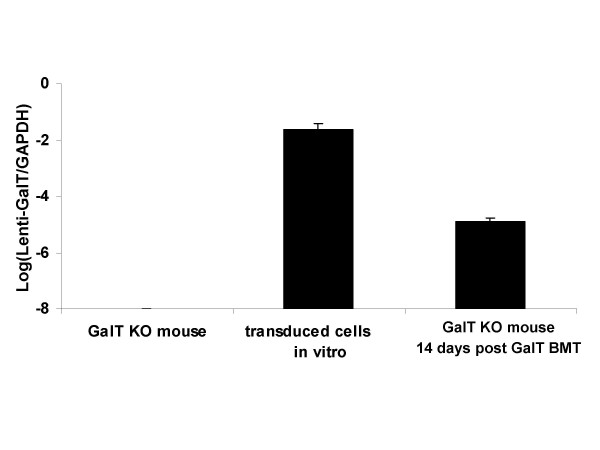

The level of GalT expression in transduced bone marrow cells

Sublethally irradiated GalT-/- mice transplanted with transduced bone marrow expressing GalT prior to heart transplantation demonstrated chimerism and permanently accepted heart grafts from wild type mice, consistent with data previously reported from our laboratory [7]. The level of GalT transduction in bone marrow cells was examined by real-time PCR using primers that specifically identify the galactosyltransferase gene in the lentiviral vector construct. The newly-introduced galactosyltransferase gene was expressed in transduced bone marrow cells in vitro as well as in vivo in bone marrow cells isolated from GalT-/-mice at fourteen days post-GalT bone marrow transplantation (BMT) as identified by real-time PCR (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Level of GalT transduction in bone marrow cells. GalT is not expressed in the bone marrow cells of the normal GalT-/- mouse, however, transduced bone marrow cells in vitro and bone marrow cells from GalT BMT mice at day 14 post-BMT express the galactosyltransferase gene as identified by real-time PCR. Relative cDNA expression levels were normalized with respect to GAPDH gene expression as an internal control. The samples were run in triplicate and the experiment was repeated twice. Standard deviations are shown for each experiment.

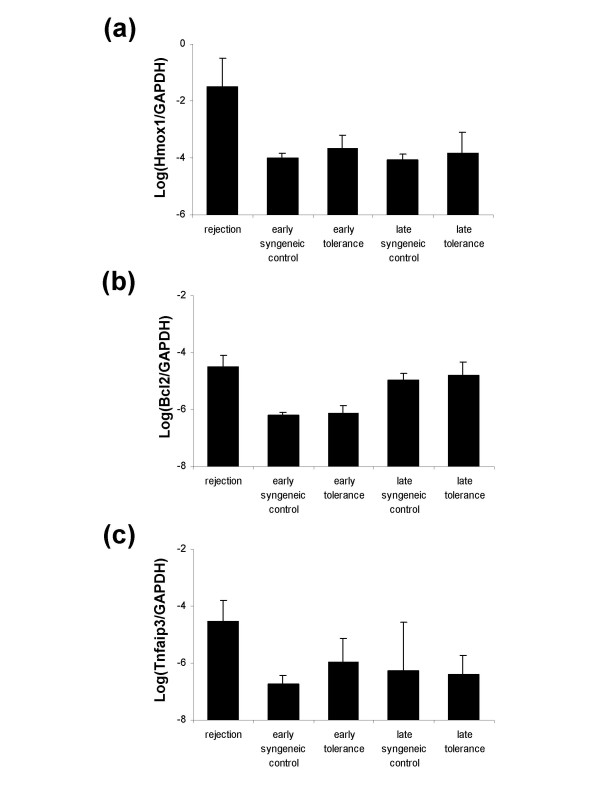

Cytoprotective genes

Genes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; Hmox1, Hsp32), Bcl2, and A20 (Tnfaip3) have been associated with accommodation in rodent xenograft models [11-13]. In contrast, gene expression changes studied in biopsies of accommodated kidney allografts in humans failed to demonstrate significant changes in the expression levels of the same cytoprotective genes [26]. To investigate whether cytoprotective genes are expressed in tolerant grafts in our model, we compared the expression levels of HO-1, Bcl2 and A20 by real-time PCR in transplanted tolerant and syngeneic control hearts. Total RNA was isolated from grafts at day 10 post-heart transplantation. The selection of this time point allowed us to study gene expression changes that occur in graft hearts at the early stages of tolerance induction. We also isolated total RNA from grafts in GalT BMT chimeras demonstrating long-term tolerance to αGal+ heart grafts during later stages of tolerance (>2 months post-heart transplantation) to allow us to compare levels of cytoprotective gene expression at early and later time points. Lymphocyte infiltration that was evident in rejecting grafts could not be detected in tolerant hearts as identified by histology at both early and late time points after transplantation. Infiltrating immune cells were therefore not likely to contribute substantially to gene expression changes in the tolerance model. Our results show that cytoprotective genes were not increased at either early or late time points in tolerant grafts (Fig. 2a–c). These data suggest that the mechanism of tolerance in this model does not involve selective up-regulation of these genes.

Figure 2.

Cytoprotective gene expression by real-time PCR. Cytoprotective genes (Hmox1, Bcl2, Tnfaip3) expressed in syngeneic control grafts and in tolerant grafts at both early (day 10) and late (>2 months) time points after transplantation were identified by real-time PCR. Relative cDNA expression levels were normalized with respect to GAPDH gene expression as an internal control. Results are shown as the logarithmic value of respective gene expression. Standard deviations are shown for each experiment which was run in triplicate. (a): Hmox1 (HO-1); (b): Bcl2; (c): Tnfaip3 (A20).

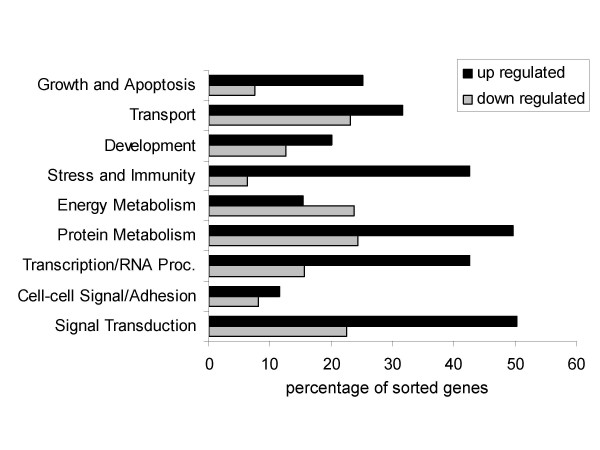

Gene expression profiling in tolerant heart grafts: Functional classification of significantly up-regulated genes

In order to further understand the early events that occur within tolerant grafts, we extended our analysis to the application of gene expression profiling. This technique makes it possible to identify novel gene expression changes that characterize the immunological events associated with tolerance induction. We isolated RNA from transplanted hearts following GalT BMT at ten days after heart transplantation (n = 4) as well as from syngeneic heart transplant controls (n = 4) for microarray analysis. Our objective was to identify novel genes and pathways that may be associated with the early stages of tolerance induction and to compare our data with information in the literature identifying genes uniquely expressed in tolerant grafts. The data were normalized with the dChip software and analyzed by the algorithm "Significant Analysis of Microarrays (SAM)" with a q-value cutoff of 10% and a fold change of greater than 1.5 and less than 0.75. Using these criteria, 535 probe sets representing 465 genes were selected as up-regulated genes and 311 probe sets representing 272 genes were selected as down-regulated. In order to determine whether these genes could be associated with specific functional categories, we used L2L software (ver. 2006.2) to sort the data into each of 9 functional subsets according to the Gene Ontology (GO; ver. 2006.2) "biological process" categories (Fig. 3). The genes classified in the subsets of "stress and immunity" (GO: 0006955, 0006350), "transcription/RNA processing" (GO: 0007165), and "signal transduction" (GO: 0016070, 0006350) were significantly up-regulated during the early stages of tolerance induction. Genes classified in the "energy metabolism" (GO: 0005975, 0006118, 0006629, 0006119, 0006800) category were down-regulated.

Figure 3.

Functional subsets that are up- or down-regulated in tolerance model. L2L software was used to sort the up- or down-regulated genes in tolerant grafts (GalT BMT) compared to syngeneic control grafts. Nine functional subsets were identified using Gene Ontology Biological Process categories.

Profiling of the biological processes associated with significantly up-regulated genes induced in tolerant heart grafts

L2L software was used to sort and prepare a summary profile of biological processes associated with genes with increased expression in tolerant grafts as compared to controls at the day 10 time point (Table 1). This table separates genes according to biological processes using a p-value of less than 0.01 as a basis for selection. Genes are ranked according to "binomial p-values," the p-values representing the statistical significance of the overlap, derived from a binomial distribution. "Total probes" signifies the total number of probes representing genes on the list. The list of "expected matches" includes the number of probes derived from the list that would match our data by random chance. The list of "actual matches" shows the number of matches identified with our data. "Fold enrichment" is the fold-enrichment of genes that match our data (actual/expected). As shown in Table 1, the top three categories for function of genes with increased expression in tolerant hearts were "response to biotic stimulus", "defense response" and "immune response." Gene Ontology defines "response to biotic stimulus" as a change in state or activity of a cell or an organism (in terms of movement, secretion, enzyme production, gene expression, etc.) as a result of a biotic stimulus, a stimulus caused or produced by a living organism. The genes in this category show a 2.7 fold enrichment, the highest number of actual matches, and the lowest binomial p-values. Genes in the "defense response" and "immune response" categories demonstrated similar levels of fold enrichment, actual matches and low binomial p-values. Within these 3 categories, fifty-five up-regulated genes that were common to all three categories were identified as preferentially expressed during the early stages of tolerance induction in our model (Table 2).

Table 1.

Gene Ontology: biological process – up-regulated genes in tolerant hearts compared to syngeneic controls

| List Name | Total probes | Expected matches | Actual matches | Fold Enrichment | Binomial p-values |

| response to biotic stimulus | 1353 | 22.64 | 61 | 2.69 | 1.16E-11 |

| defense response | 1275 | 21.33 | 53 | 2.48 | 3.86E-09 |

| immune response | 1166 | 19.51 | 50 | 2.56 | 3.87E-09 |

| response to virus | 108 | 1.81 | 12 | 6.64 | 3.04E-07 |

| response to pest, pathogen or parasite | 767 | 12.83 | 33 | 2.57 | 1.41E-06 |

| response to other organism | 782 | 13.08 | 33 | 2.52 | 2.13E-06 |

| response to stimulus | 3134 | 52.44 | 87 | 1.66 | 6.47E-06 |

| JAK-STAT cascade | 66 | 1.1 | 8 | 7.24 | 1.49E-05 |

| protein kinase cascade | 610 | 10.21 | 26 | 2.55 | 2.02E-05 |

| response to pathogenic bacteria | 24 | 0.4 | 5 | 12.45 | 4.27E-05 |

| regulation of DNA binding | 15 | 0.25 | 4 | 15.94 | 9.23E-05 |

| I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB cascade | 223 | 3.73 | 13 | 3.48 | 1.18E-04 |

| nuclear transport | 254 | 4.25 | 14 | 3.29 | 1.19E-04 |

| nucleocytoplasmic transport | 276 | 4.62 | 14 | 3.03 | 2.79E-04 |

| response to pathogen | 35 | 0.59 | 5 | 8.54 | 2.80E-04 |

| maintenance of localization | 38 | 0.64 | 5 | 7.86 | 4.15E-04 |

| response to bacteria | 59 | 0.99 | 6 | 6.08 | 4.63E-04 |

| regulation of binding | 23 | 0.38 | 4 | 10.39 | 5.38E-04 |

| response to stress | 1778 | 29.75 | 49 | 1.65 | 6.71E-04 |

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | 14 | 0.23 | 3 | 12.81 | 1.48E-03 |

| immune cell mediated cytotoxicity | 15 | 0.25 | 3 | 11.95 | 1.83E-03 |

| negative regulation of protein import into nucleus | 15 | 0.25 | 3 | 11.95 | 1.83E-03 |

| negative regulation of transcription factor import into nucleus | 15 | 0.25 | 3 | 11.95 | 1.83E-03 |

| cytoplasmic sequestering of transcription factor | 15 | 0.25 | 3 | 11.95 | 1.83E-03 |

| cytoplasmic sequestering of protein | 15 | 0.25 | 3 | 11.95 | 1.83E-03 |

| negative regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport | 16 | 0.27 | 3 | 11.21 | 2.23E-03 |

| negative regulation of protein transport | 16 | 0.27 | 3 | 11.21 | 2.23E-03 |

| inflammatory response | 311 | 5.2 | 13 | 2.5 | 2.57E-03 |

| cholesterol metabolism | 140 | 2.34 | 8 | 3.42 | 2.61E-03 |

| tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT protein | 17 | 0.28 | 3 | 10.55 | 2.67E-03 |

| regulation of NF-kappaB import into nucleus | 17 | 0.28 | 3 | 10.55 | 2.67E-03 |

| NF-kappaB import into nucleus | 17 | 0.28 | 3 | 10.55 | 2.67E-03 |

| antigen receptor-mediated signaling pathway | 18 | 0.3 | 3 | 9.96 | 3.17E-03 |

| nuclear export | 115 | 1.92 | 7 | 3.64 | 3.34E-03 |

| cell killing | 19 | 0.32 | 3 | 9.44 | 3.71E-03 |

| sterol metabolism | 149 | 2.49 | 8 | 3.21 | 3.82E-03 |

| detection of stimulus | 63 | 1.05 | 5 | 4.74 | 4.12E-03 |

| positive regulation of apoptosis | 368 | 6.16 | 14 | 2.27 | 4.18E-03 |

| positive regulation of programmed cell death | 368 | 6.16 | 14 | 2.27 | 4.18E-03 |

| detection of external stimulus | 41 | 0.69 | 4 | 5.83 | 4.85E-03 |

| detection of abiotic stimulus | 41 | 0.69 | 4 | 5.83 | 4.85E-03 |

| DNA metabolism | 1205 | 20.16 | 33 | 1.64 | 4.94E-03 |

| viral genome replication | 42 | 0.7 | 4 | 5.69 | 5.29E-03 |

| RNA export from nucleus | 97 | 1.62 | 6 | 3.7 | 5.94E-03 |

| nucleic acid transport | 97 | 1.62 | 6 | 3.7 | 5.94E-03 |

| RNA transport | 97 | 1.62 | 6 | 3.7 | 5.94E-03 |

| establishment of RNA localization | 97 | 1.62 | 6 | 3.7 | 5.94E-03 |

| caspase activation | 44 | 0.74 | 4 | 5.43 | 6.25E-03 |

| response to drug | 44 | 0.74 | 4 | 5.43 | 6.25E-03 |

| positive regulation of caspase activity | 44 | 0.74 | 4 | 5.43 | 6.25E-03 |

| lipid transport | 131 | 2.19 | 7 | 3.19 | 6.78E-03 |

| RNA localization | 101 | 1.69 | 6 | 3.55 | 7.20E-03 |

Table 2.

Up-regulated genes in tolerant hearts classified as response to biotic stimulus, defense response, and immune response

| Probe ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Also known as |

| 1416111_at | Cd83 | CD83 antigen | |

| 1416295_a_at | Il2rg | interleukin 2 receptor, gamma chain | CD132 |

| 1416697_at | Dpp4 | dipeptidylpeptidase 4 | Cd26; THAM; Dpp-4 |

| 1459973_x_at | Dpp4 | ||

| 1417056_at | Psme1 | proteasome (prosome, macropain) 28 subunit, alpha | PA28a |

| 1417189_at | Psme2 | proteasome (prosome, macropain) 28 subunit, beta | PA28b |

| 1417640_at | Cd79b | CD79B antigen | B29; Igb; Ig-beta |

| 1418652_at | Cxcl9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | CMK; Mig; Scyb9; crg-10 |

| 1419282_at | Ccl12 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 12 | MCP-5; Scya12 |

| 1419684_at | Ccl8 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | HC14; MCP-2; Scya8 |

| 1420089_at | Nfkbia | nuclear factor of kappa light chain gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | |

| 1448306_at | Nfkbia | ||

| 1449731_s_at | Nfkbia | ||

| 1420788_at | Klrg1 | killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, member 1 | MAFA; 2F1-Ag; MAFA-L |

| 1420915_at | Stat1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | |

| 1450033_a_at | Stat1 | ||

| 1450034_at | Stat1 | ||

| 1421578_at | Ccl4 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | Act-2; Mip1b; Scya4; MIP-1B |

| 1421818_at | Bcl6 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 6 | Bcl5 |

| 1421911_at | Stat2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | |

| 1422005_at | Eif2ak2 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 2 | Pkr; tik; Prkr |

| 1422028_a_at | Ets1 | E26 avian leukemia oncogene 1, 5' domain | Tpl1; Ets-1 |

| 1422903_at | Ly86 | lymphocyte antigen 86 | MD1 |

| 1422962_a_at | Psmb8 | proteosome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 8 (large multifunctional peptidase 7) | Lmp7 |

| 1424208_at | Ptger4 | prostaglandin E receptor 4 (subtype EP4) | EP4; Ptgerep4 |

| 1425396_a_at | Lck | lymphocyte protein tyrosine kinase | Hck-3; p56 |

| 1425548_a_at | Lst1 | leukocyte specific transcript 1 | B144 |

| 1426587_a_at | Stat3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | Aprf |

| 1427689_a_at | Tnip1 | TNFAIP3 interacting protein 1 | Nef; ABIN; Naf; ABIN1 |

| 1427746_x_at | H2-K1 | histocompatibility 2, K1, K region | H-2K; H2-K; MHC I; |

| 1429272_a_at | Apol3 | apolipoprotein L 3 | |

| 1433508_at | Klf6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 | FM2; FM6; Zf9; BCD1; CPBP; Copcb; Ierepo1; Ierepo3 |

| 1434438_at | Samhd1 | SAM domain and HD domain, 1 | Mg11 |

| 1435560_at | Itgal | integrin alpha L | Cd11a; LFA-1; Ly-15; Ly-21 |

| 1435710_at | Cd226 | CD226 antigen | Pta1; PNAM1; TLiSA1 |

| 1435906_x_at | Gbp2 | guanylate nucleotide binding protein 2 | |

| 1436562_at | Ddx58 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 58 | RIG-I |

| 1436779_at | Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | Cgd; Nox2; gp91phox |

| 1437304_at | Cblb | Casitas B-lineage lymphoma b | |

| 1438052_at | Ptprc | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, C | Ioc; Ly-5; T200; CD45R; Lyt-4 |

| 1439034_at | Spn | sialophorin | Cd43; Ly48; Galgp |

| 1439680_at | Tnfsf10 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | TL2; Ly81; Trail; APO-2L |

| 1439773_at | Ly6e | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | Ly67; Tsa1; RIG-E; Sca-2; TSA-1 |

| 1439819_at | Ctsc | cathepsin C | DPP1 |

| 1440169_x_at | Ifnar2 | interferon (alpha and beta) receptor 2 | |

| 1441026_at | Parp4 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 4 | PH5P; p193; Gm743; PARPL; VPARP; VAULT3; Adprtl1 |

| 1445897_s_at | Ifi35 | interferon-induced protein 35 | IFP35 |

| 1459151_x_at | Ifi35 | ||

| 1448436_a_at | Irf1 | interferon regulatory factor 1 |

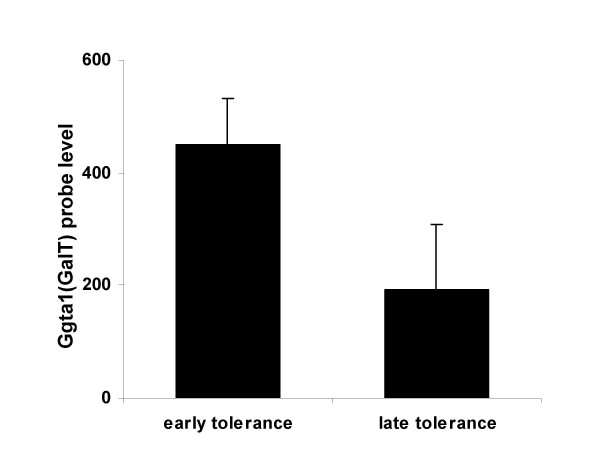

Intragraft α1,3 galactosyltransferase gene expression

An additional factor that plays a key role in long-term graft survival is the level of expression of xenoantigens on the surface of the graft. Accommodation has been associated with a decrease in the expression level of incompatible carbohydrate antigens on highly vascularized grafts exposed to tolerable levels of allo- or xenoantibodies [27]. We therefore evaluated whether or not changes in expression level of the gene encoding for the gal carbohydrate occur in either the immediate or late post-transplant periods in our model of tolerance induction. Expression of the galactosyltransferase gene which encodes the target of rejection of wild type organs in this model was significantly reduced during the late post-transplant period (Fig. 4), suggesting that a reduction in the level of expression of the αGal epitope occurs on the graft at later time points post transplant. Lower levels of expression of the gal carbohydrate may therefore contribute to the maintenance of long-term tolerance in this model.

Figure 4.

Intragraft GalT expression changes in tolerant heart grafts. Ggta1 (1418483_a_at) probe expression levels at early (day 10) and late (>2 months) time points in tolerant hearts, identified by microarray analysis. Standard deviations are shown as error bars.

Validation of microarray results by real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was used to confirm the results obtained from the gene expression profiling studies. Four up-regulated genes and 3 down-regulated genes were selected for quantification of gene expression by real-time PCR. RNA from transplanted hearts isolated from GalT BMT groups (n = 4) and syngeneic control groups (n = 4) was used for this experiment. Real-time PCR results were found to correlate with the differential gene expression data obtained by the microarray analysis (Fig. 5). The sequences of primers used for real-time PCR validation are listed in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Validation of microarray results by real-time PCR. Selected genes (Ptger4, Tnsls10, Il2rg, Stat3, Cfh, Cxcl12, Hfe) in the early tolerance group (GalT BMT) compared to syngeneic controls were analyzed by real-time PCR to determine whether the data obtained by microarray analysis could be validated using an alternative technique. Relative cDNA expression levels were normalized with respect to GAPDH gene expression as internal control. Results are shown as the logarithmic value of mean fold-change of gene expression.

Table 3.

Primer sequences used to identify gene transcript levels by real-time PCR

| Gene Symbol | Sequence (5' -> 3') | |

| lenti-porcine GalT | sense | GTT CGC TTC TCG CTT CTG TT |

| antisense | CCA AAA CAC AAC CAT TAC AGT TGA G | |

| Ptger4 (EP4) | sense | TAC TTC TAC AGC CAC TAC GTG GAC |

| antisense | TGG TCC AGT CGA TGA AGC ACC AGG | |

| Tnfsf10 (Trail) | sense | ACC ACG TGC TCT TTA GGA ATG GAG |

| antisense | AGA CCA TCT TGG AAG CGT CTT CAG | |

| Il2rg (CD132) | sense | GGT TGG AAC GAA TGC CTC CAA TTC |

| antisense | GCA GAA CCG TTC ACT GTA GTC TGG | |

| Stat3 | sense | GCA AAG AGT CAC ATG CCA CGT TGG |

| antisense | AGA TAC CTG CTC TGC AGA AAC TGC | |

| Cfh | sense | AAG GTG GCA GTC ATT ACC TCG CTG |

| antisense | GTT CAT GAC TGC TGG ACT CAA TGG | |

| Cxcl12 | sense | CGC TCT GCA TCA GTG ACG GTA AAC |

| antisense | CTT CAG CCG TGC AAC AAT CTG AAG | |

| Hfe | sense | TCT CTA AGG TGT CAG GCT CTG GAC |

| antisense | TGT CAG CCA GCC TTG ATA GGT CTC | |

| Foxp3 | sense | TCC AGA GAG AAG TGG TGC AGT CTC |

| antisense | GTG GCT ACG ATG CAG CAA GAG CTC | |

| Hmox1 (HO-1) | sense | ACA GAT GGC GTC ACT TCG TCA GAG |

| antisense | ACT GCC ACT GTT GCC AAC AGG AAG | |

| Bcl2 | sense | GAT GCC TTT GTG GAA CTA TAT GGC |

| antisense | AGG TAT GCA CCC AGA GTG ATG CAG | |

| Tnfaip3 (A20) | sense | CTA AGC CAA CGA GTA GGT TCT GTG |

| antisense | CCA TAC ATC TGC TTG AAC TGG TAG | |

| GAPDH | sense | GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GAG |

| antisense | TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA GCC |

Discussion

An understanding of the systemic and intragraft gene expression changes that promote immune modulation and long term graft survival may provide insight into new ways to achieve tolerance. One of the most well-studied methods for inducing tolerance is by the induction of chimerism in Gal KO mice [3-7]. These mice do not express the galactosyltransferase that is responsible for gal carbohydrate expression and produce high levels of anti-gal antibodies after immunization [28]. As gal knockout mice age, they naturally produce anti-α Gal antibodies at levels that are sufficient to cause delayed rejection of wild type mouse hearts [29]. Anti-gal xenoantibodies induced after immunization are capable of initiating hyperacute rejection of gal+ hearts [28]. This small animal model is extensively used to study xenoantibodies to grafts that express the gal carbohydrate, the major antigen responsible for initiating xenograft rejection. Chimerism for the gal carbohydrate can be achieved in a number of ways and results in tolerance to wild type gal+ heart grafts [3-7].

The mechanisms by which tolerance can be achieved after the induction of chimerism include systemic changes such as B cell hyporesponsiveness, initially due to anergy, and receptor editing or clonal deletion which occur later [9]. Regulatory T cells can also contribute to long-term graft survival [30]. Our laboratory has been interested in studying the induction of chimerism using lentiviral vectors to express the galactosyltransferase gene in the bone marrow. In this model, systemic events associated with tolerance induction similarly include receptor editing and/or clonal deletion [7]. Cytoprotective IgG2b antibodies [7] and elevated levels of cytoprotective genes HO-1 and A20 that contribute to graft accommodation [11,31] were not induced at levels higher than those identified in syngeneic transplant controls [21]. Data similar to ours was recently reported in a clinical study which showed that protective genes Bcl-2 and A20 were not induced in human cardiac biopsies taken at 0–2 months from non-rejecting grafts, however these genes were shown to be induced at later times (>10 months post-transplant) [32]. The time between transplantation and gene expression analysis may therefore be an important consideration. Cytoprotective genes were, however, induced at early timepoints in the rejecting grafts in our study. This finding is consistent with prior reports that A20 and/or HO-1 are upregulated in response to immune injury during acute rejection of renal, heart and lung allografts [32-34]. These gene products have anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic functions which may be produced in an attempt to protect grafts from injury [35-37]. Expression of the gene encoding the gal carbohydrate, in contrast, was significantly reduced in tolerant hearts. Similar findings have been reported in models of accommodation where expression of endothelial carbohydrate antigens declines post-transplantation [27]. The level of expression of the gal carbohydrate influences not only the antibody response, but impacts the cellular immune response. NK cells have receptors that recognize the α Gal epitope, and this recognition may contribute to the induction of a cellular immune response in the post-transplant period [38,39].

The gene expression profile associated with tolerance induction may be a key predictor of graft outcome. Within the past few years, microarray technology has been applied to identify gene expression changes that distinguish tolerance and rejection in various models. Although the conditions under which tolerance is induced are not uniform, the source of cells or tissues varies, the biostatistical analysis differs and the software used in studies from other laboratories varies, differential gene expression in stress-activated pathways and immune response genes tends to distinguish tolerant grafts from controls [21,22,40-43]. Our results are strikingly similar to those reported from two other laboratories who identified a small number of genes that were associated with the induction and maintenance of tolerance to liver grafts in rodents. The genes that were common to the molecular signature of tolerance in these three studies included STAT-1, IRF-1, Gpb2 and several chemokines [42,43]. STAT-1 and IRF-1 are the two key transcripts that play a role in the pathway that links IFN-γ signalling to the induction of apoptosis [44,45]. The fact that these transcripts were induced in the early stages of tolerance to heart and liver grafts [42] and in the PBL of tolerant recipients of liver grafts at 100 days post-transplantation [43] suggests that the STAT-1/IRF-1 apoptotic pathway may be important in the induction and maintenance of graft tolerance. The data from our lab and others suggests that the tolerant graft itself responds on a continuous basis to the environment around it.

Tolerance to pig organs is a long-term goal in the field of xenotransplantation. Whether this is achieved by introduction of new genes in the donor organs prior to transplantation, or by the development of methods that adequately suppress the immune response to porcine xenoantigens, gene expression profiling of tolerant grafts is providing new insight into the mechanisms by which tolerance is achieved and maintained. An improved understanding of the similarities and differences in intragraft gene expression profiles that are associated with tolerance induced by various approaches and a clear statement of the methods used for the analysis of the data should allow new opportunities to identify common parameters in intragraft gene expression profiles in tolerant grafts. In addition, the development of accurate, targeted and reliable tests for gene expression in graft biopsies may someday be available for use in clinical transplantation as a means to monitor graft survival.

Conclusion

In this study, we have described the intragraft gene expression changes that associate with the induction of tolerance to the αGal carbohydrate. Although the cytoprotective genes HO-1, Bcl2 and A20 were not induced in the early stages of tolerance induction in this model, genes associated with stress and immunity were up-regulated. This result suggests that the tolerant graft itself responds on a continuous basis to the environment around it. The reduction of αGal carbohydrate gene expression over time in tolerant grafts indicates the possibility of adaptation of the graft. An improved understanding of the similarities and differences in intragraft gene expression profiles that are associated with tolerance induced by various approaches and a clear statement of the methods used for the analysis of the data should allow new opportunities to identify common parameters in intragraft gene expression profiles in these grafts.

Methods

Mice

Gal T-/- mice homozygous for the targeted disruption in the GalT gene do not express the αGal epitope and produce anti-αGal-reactive antibodies in their serum. GalT-/- mice were backcrossed 10 times using C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and were obtained from Dr. A. d'Apice (St Vincent's Hospital in Melbourne, Australia). The mice used for these experiments were 12 to 16 weeks age at the time of heart transplantation. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care, formulated by the National Society for Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, prepared by the National Institutes of Health.

Transplantation of bone marrow cells transduced by lentiviral vectors

A nonmyeloablative regimen was used to establish chimerism by transplantation of bone marrow cells transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing porcine α1,3 galactosyltransferase, as previously described [7]. Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs of GalT-/- mice and were transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing the porcine α1,3 GalT gene. Recipient mice were matched for age and anti-αGal Ab levels prior to bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Mice were sublethally irradiated with 3 Gy of whole-body irradiation using a 137Cs irradiator. Transduced bone marrow cells (2.7 × 107 to 5.0 × 107 cells) were administered by tail vein injection to recipient GalT-/- mice within 48 hours after irradiation.

Heterotopic heart transplantation

Intra-abdominal heterotopic heart transplantation was performed at 2 to 4 weeks after BMT [46]. Heart grafts from C57BL/6 mice were transplanted into GalT BMT mice (n = 6), C57BL/6 syngeneic control mice (n = 8), and GalT-/- mice that did not receive a BMT to induce chimerism (n = 6). Mice were anesthetized with 1.5 to 2.0% Isoflurane. The heart grafts from C57BL/6 mice which were transplanted to GalT-/- mice in the absence of a BMT to achieve chimerism were rejected at an average of 12.8 days after transplantation. Graft function was monitored daily by palpation. At day 10 post heart transplantation, recipient mice were euthanized for examination. Tolerance at early and late time points was compared by isolation of hearts at Day 10 (n = 6) and at >2 months post-heart transplantation (n = 3). Matched syngeneic control mice were examined at early and late time points (n = 8, n = 3 each). The RNA was extracted from the graft tissue and microarray data were used to compare gene expression at the early and later time points.

RNA extraction from heart graft samples

The graft heart tissues for RNA extraction were immediately frozen and kept at -80°C. RNA was isolated and purified using an RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Optical density was measured by spectrophotometry at 260 and 280 nm, and integrity of total RNA was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Microarray target preparation and hybridization for Affymetrix GeneChips

Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse 430 2.0 Expression Arrays were used for this study. Two μg of tRNA was reverse transcribed using a T7-Oligo(dT) primer. Second-strand cDNA was purified and used as a template for in vitro transcription (IVT). IVT with T7 RNA Polymerase and biotin yielded labeled cRNA targets that were then fragmented and 10 μg hybridized to the GeneChip. These procedures were performed by the USC/CHLA Genome Core, Department of Pathology, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles according to the manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Microarray data analysis

The processed image file of the Affymetrix Mouse 430v2 array contained over 45000 probe sets covering approximately 39000/34000 transcripts/genes [47]. The probe set level data were analyzed with the dChip software [48]. Values deemed "present' using the PM/MM correction model with single probe rejection were considered further. The algorithm "Significant Analysis of Microarrays (SAM)" which uses a permutation test to set the "no-change" expression threshold, selecting genes that showed statistically significant differences for each condition. The program generated a false positive rate or a q-value for each gene for the replicated samples using a nearest neighbor metric. This test creates a set of individual genes that are differentially expressed for each ligand-time condition. To note the enrichment of a particular gene annotation from the list of differentially expressed genes determined to be statistically significant (p < 0.01), we used the hypergeometric distribution formula. The gene ontology was obtained from the L2L database [49]. We selected the gene attribute "biological process" as described by the Gene Ontology Consortium [50] for subgroup enrichment. We elected to use dChip, SAM, and L2L software packages as they are available free of charge to facilitate the comparison of our data with that obtained by other investigators interested in the identification of genes expressed in tolerant grafts. The microarray data used in this study was deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [51] with accession numbers GSM179880 through GSM 179573. The microarray data are also available in a series with accession number GSE 7424.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA (Omniscript RT Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) and a Quantitect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplification was performed at 95°C for 15 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec. Each PCR was performed in triplicate. Samples were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel to confirm that nonspecific amplification did not occur. Results were expressed relative to the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Oligonucleotides used as primers in this study are shown in Table 3.

List of abbreviations

All abbreviations are defined at their first appearance in the text, and in the legends of tables and figures, as follows:

αGal – Galα1,3Galβ1,4GlcNac-R

GalT – α1,3 galactosyltransferase

GalT-/- – gal knockout

NF-κB – nuclearfactor kappa B

BMT – bone marrow transplantation

HO-1 – heme oxygenase-1

SAM – significant analysis of microarrays

Gene Ontology – GO

IVT – in vitro transcription

NCBI – National Center for Biotechnology Information

GEO – Gene Expression Omnibus

Authors' contributions

TD performed the heart transplants, prepared the RNA, was responsible for the real-time PCR and the microarray data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MM transduced the bone marrow cells and produced the bone marrow chimeras. DM analyzed the gene expression arrays and provided suggestions for the statistical analysis of the microarray data. JME provided the RNA for the PCR used to identify gene expression at >2 months post-transplant. MKJ designed the study, participated in its coordination, and made major contributions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from The Robert E. and May R. Wright Foundation Research Award to MKJ. Grant number 23-5131-2264.

Contributor Information

Tomoko Doki, Email: tdoki@chla.usc.edu.

Michael Mello, Email: mellom@usc.edu.

Dennis Mock, Email: dmock@chla.usc.edu.

Jacqueline M Evans, Email: jaevans@chla.usc.edu.

Mary Kearns-Jonker, Email: mkearns@chla.usc.edu.

References

- Sandrin MS, Vaughan HA, Dabkowski PL, McKenzie IFC. Anti-pig IgM antibodies in human serum react predominantly with Gal(α1–3)Gal epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11391–11395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tearle TF, Tange MJ, Zannettino ZL, Katerelos M, Shinkel TA, Van Denderen BJW, Lonie AJ, Lyons I, Nottle MB, Cox T, Becker C, Oeura AM, Wigley PL, Crawford RJ, Robins AJ, Pearse MJ, d'Apice AJF. The α1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout mouse: implications for xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:13–19. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U. Immune response, accommodation, and tolerance to transplantation carbohydrate antigens. Transplantation. 2004;78:1093–1098. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000142673.32394.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes M, Shimizu I, Kawahara T. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism for the simultaneous induction of T and B cell tolerance. Transplantation. 2005;79:S28–29. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000153296.80385.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracy JL, Iacomini J. Induction of B-cell tolerance by retroviral gene therapy. Blood. 2000;96:3008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns-Jonker M, Fischer-Lougheed J, Shulkin I, Kleihauer A, Mitsuhashi N, Kohn DB, Weinberg K, D'Apice AJF, Starnes VA, Cramer DV. Use of lentiviral vectors to induce long-term tolerance to gal+ heart grafts. Transplantation. 2004;77:1748–1754. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000131174.52424.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi N, Fischer-Lougheed J, Shulkin I, Kleihauer A, Kohn DB, Weinberg KI, Starnes VA, Kearns-Jonker M. Tolerance induction by lentiviral gene therapy with a nonmyeloablative regimen. Blood. 2006;107:2286–2293. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Lougheed JY, Tarantal AF, Shulkin I, Mitsuhashi N, Kohn DB, Lee CCI, Kearns-Jonker M. Gene therapy to inhibit xenoantibody production using lentiviral vectors in non-human primates. Gene Ther. 2007;14:49–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara T, Shimizu I, Ohdan H, Zhao G, Sykes M. Differing mechanisms of early and late B cell hyporesponsiveness induced by mixed chimerism. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2821–2829. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu I, Kawahara T, Haspot F, Bardwell PD, Carroll MC, Sykes M. B-cell extrinsic CR1/CR2 promotes natural antibody production and tolerance induction of anti-αGal-producing B-1 cells. Blood. 2007;109:1773–1781. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach FH, Ferran C, Candinas D, Miyatake T, Koyamada N, Mark W, Hechenleitner P, Hancock WW. Accommodation of xenografts: expression of "protective genes" in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:56–58. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(96)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrichani AZ, Stroka DM, Bilbao G, Curiel DT, Bach FH, Ferran C. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL serve an anti-inflammatory function in endothelial cells through inhibition of NK-κB. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:543–553. doi: 10.1172/JCI2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferran C, Stroka DM, Badrichani AZ, Cooper JT, Wrighton CJ, Soares M, Grey ST, Bach FH. A20 inhibits NF-κB activation in endothelial cells without sensitizing to tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 1998;91:2249–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter T, Risch K, Schroder G, Kolls J, Siegling A, Graser E, Reinke P, Brock J, Lehmann M, Volk HD. Intragraft overexpression of interleukin-4 is neither sufficient nor essential for tolerance induction to cardiac allografts in a high-responder strain combination. Transplantation. 1999;68:1427–1431. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csizmadia V, Gao W, Hancock SA, Rottman JB, Wu Z, Turka LA, Siebenlist U, Hancock WW. Differential NF-κB and IκB gene expression during development of cardiac allograft rejection versus CD154 monoclonal antibody-induced tolerance. Transplantation. 2001;71:835–840. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriewald BM, Billing JS, Ensminger SM, Morris PJ, Wood KJ. Linked unresponsiveness: early cytokine gene expression profiles in cardiac allografts following pretreatment of recipients with bone marrow cells expressing donor MHC alloantigen. Cytokine. 2002;19:6–13. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T, Giulietti A, Van Damme B, Overbergh L, Rutgeerts O, Kitade H, Waer M, Mathieu C, Pirenne J. Paradoxical early upregulation of intragraft Th1 cytokines is associated with graft acceptance following donor-specific blood transfusion. Transpl Int. 2003;16:179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2003.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli G, Simeoni E, Li JP, Fleury S. Lentiviral gene transfer of the chemokine antagonist RANTES 9–68 prolongs heart graft survival. Transplantation. 2006;81:240–246. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000194859.98504.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Saiura A, Sugwara Y, Sata M, Naruse K, Yagita H, Kohro T, Mataki C, Izumi A, Yamaguchi T, Minami T, Sakihama T, Ihara S, Aburatani H, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Makuuchi M. Identification of gene expression profile in tolerizing murine cardiac allograft by costimulatory blockade. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15:199–208. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00086.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Shen XD, Fang Z, Gao F, Semiletova N, Cao MJ, Busuttil RW, JW Kupiec-Weglinski, Ghobrial RM. Identification of early tolerance regulator genes induced by allochimeric therapy using microarray-based genomewide scan. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1942–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JM, Doki T, Fischer-Lougheed J, Davicioni E, Kearns-Jonker M. Expression changes in tolerant murine cardiac allografts after gene therapy with a lentiviral vector expressing α1,3 galactosyltransferase. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3172–3180. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor Sivozhelezov, Christophe Braud, Luca Giacomelli, Eugenia Pechkova, Magali Giral, Jean-Paul Soulillou, Sophie Brouard, Claudio Nicolini. Immunosuppressive drug-free operational immune tolerance in human kidney transplants recipients. II: Non-statistical gene microarray analysis. J Cellular Biochem. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21557. 2007, Nov 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiura A, Sugawara Y, Harihara Y, Sata M, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Makuuchi M. Gene expression profile during acute rejection in rat-to-mouse concordant cardiac xenograft by means of DNA microarray. Transpl Int. 2002;15:535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2002.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller TF, Ma C, Lederer JA, Perkins DL. Differentiation of stress, metabolism, communication, and defense responses following transplantation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:379–390. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0102052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher K, Mueller TF, DeFina R, Liang Y, Zhang J, Gentleman R, Perkins DL. The graft response to transplantation: a gene expression profile analysis. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15:52–64. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00139.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WD, Grande JP, Ninova D, Nath KA, Platt JL, Gloor JM, Stegall MD. Accommodation in ABO-incompatible kidney allografts, a novel mechanism of self-protection against antibody-mediated injury. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:952–960. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa Y, Brett J, Fukatsu A, Matsuo S, Caldwell PRB, Niesen N, Milgrom F, Godman G, Stern D, Andres G. Interaction of antibody with Forssman antigen in guinea pigs. A mechanism of adaptation to antibody- and complement-mediated injury. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1260–1272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gock H, Salvaris E, Han W, Murray-Segal L, Moltram P, Cowan P, Goodman DJ, d'Apice AJF. Anti-α1,3-Galactose-Mediated Hyperacute Rejection of Vascularized Transplants in a Small Animal Model. Transplantation Proceedings. 2000;32:2075. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)01574-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaris EJ, Gock H, Han W, Murray-Segal L, Barlow H, Mottram P, Pearse MJ, Cowan PJ, Goodman DJ, d'Apice AJF. Naturally-acquired anti-α-Gal antibodies in a murine allograft model similar to delayed xenograft rejection. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:42–47. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz J, Wekerle T, Sykes M. Tolerance in mixed chimerism – a role for regulatory cells? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin MM, Ogawa H, Yin DP, Shen J, Galili U. Antibody-mediated accommodation of heart grafts expressing an incompatible carbohydrate antigen. Transplantation. 2003;75:258–262. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000053616.61907.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza A, Felkin L, McCormack A, Holder A, Barton P, Banner N, Rose M. Sequential expression of three known protective genes in cardiac biopsies after transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:584–590. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000153154.37616.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avihingsanon Y, Ma N, Csizmadia E, Wang C, Pavlakis M, Giraldo M, Strom TB, Soares MP, Ferran C. Expression of protective genes in human renal allografts: a regulatory response to injury associated with graft rejection. Transplantation. 2002;73:1079–1085. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnell M, Visner G, Zander D, Mandalapu S, Kazemfar K, Spears L, Beaver T. Heme-oxygenase-1 expression correlates with severity of acute cellular rejection in lung transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MP, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1 in organ transplantation. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4932–4945. doi: 10.2741/2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke B, Shen XD, Lassman CR, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Cytoprotective and antiapoptotic effects of IL-13 in hepatic cold ischemia/reperfusion injury are heme-oxygenase-1 dependent. Am J Transplant. 2003;9:1076–1082. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunber U, Floege J, von Jurgensonn AS, Stijanovic T, Merkel S, Grone HJ, Ferran C. Expression of A20 in the vessel wall of rat-kidney allografts correlates with protection from transplant arteriosclerosis. Transplantation. 2003;75:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200301150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen D, Mouhtouris E, Milland J, Zingoni A, Santoni A, Sandrin MS. Recognition of a carbohydrate xenoepitope by human NKRP1A (CD161) Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, Zeng H, Ma L, Shen J, Xu H, Byrne GW, Chong AS. Cutting edge: NK cells mediate IgG1-dependent hyperacute rejection of xenografts. J Immunol. 2004;172:7235–7238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslan JM, Renaudin K, Thebault P, Josien R, Cuturi MC, Chiffoleau E. New evidence for a role of allograft accommodation in long-term tolerance. Transplantation. 2006;82:1185–1193. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000236573.01428.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg T, Wu T, Levay-Young B, Heuss N, Pan Y, Kirchhof N, Sutherland DE, Hering BJ, Guo Z. Comparison of tolerated and rejected islet grafts: a gene expression study. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:619–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba S, Wang C, Williams R, Li J, Smit L, Sharland A, Allen R, McCaughan G, Bishop A. Gene array analysis of a rat model of liver transplant tolerance identifies increased complement C3 and the STAT-1/IRF-1 pathway during tolerance induction. Liver Transplantation. 2006;12:636–643. doi: 10.1002/lt.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino M, Kitazawa Y, Kawasaki M, Funeshima N, Kimura J, Nakajima T, Saito H, Li X. Differences in lymphocyte gene expression between tolerant and syngeneic liver grafted rats. Liver Transplantation. 2004;10:379–391. doi: 10.1002/lt.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Debatin K. IFN gamma sensitizes for apoptosis by upregulating caspase 8 expression through the Stat-1 pathway. Oncogene. 2004;21:2295–2308. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano A, Watanabe Y, Takeda N, Alzawa S, Alkaike T. Analysis of IFN gamma induced cell cycle arrest and cell death in hepatocytes. J Biochem Tokyo. 1997;121:677–683. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affymetrix http://www.Affymetrix.com

- Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: Expression index computation and outlier detection. PNAS. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L2L database http://depts.Washington.edu/l2l

- Gene Ontology Consortium http://www.geneontology.org

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo