Abstract

Despite a high prevalence of domestic violence among welfare clients, most studies of the implementation of the Family Violence Option (FVO) under welfare reform find that women rarely receive domestic violence services in welfare offices. This study reviews findings from current research on the factors that improve the likelihood that women will reveal their domestic violence experiences to service personnel, and uses the guidelines drawn from this review to evaluate domestic violence screening practices in welfare offices using 782 transcribed interviews between welfare workers and clients from 11 sites in four states. The analysis found that only 9.3% of case encounters involved screening for domestic violence. Screening rates differed by state, interview type, and length of worker employment. Qualitative analysis of the interviews showed that the majority of screening by workers was routinized or consisted of informing clients of the domestic violence policy without asking about abuse. Only 1.2% of the interviews incorporated at least two of the procedures that increase the likelihood of disclosure among domestic violence survivors, suggesting deeply inadequate approaches to screening for abuse within the context of welfare offices, and a need for improved training, protocol, and monitoring of FVO implementation.

Keywords: domestic violence, Family Violence Option (FVO), frontline Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), welfare

The public welfare office is a critical location for securing resources for impoverished battered women with children. Women report that obtaining independent financial support is an essential step in the process of ending abuse (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999), and the welfare office is a location to which poor women turn for this support (Brandwein, 1999). With the passage of the Family Violence Option (FVO) amendment, 42 U.S.C. 602 (a) [7], to the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA; 1996), Congress emphasized that battered women should be able to obtain services through the welfare system, even if they were unable to comply with new welfare reform regulations as a result of the abuse. States could voluntarily elect to implement the FVO, and by 1999, 28 states certified that they had done so (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 1999). By adopting the FVO, states agreed to “screen and identify individuals receiving assistance … [for] a history of domestic violence while maintaining the confidentiality of such individuals” (42 U.S.C. 602 [a] [7], paragraph i). Women so identified are to be referred to counseling and supportive services, and are eligible for good cause waivers from program rules if these requirements would make it harder to escape the abuse or would unfairly penalize the abused woman.

Domestic violence is common among welfare recipients (Tolman & Raphael, 2000) and affects women’s employability in complex ways (Lindhorst, Oxford, & Gillmore, 2007; Riger & Staggs, 2004). A survey of female California Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) recipients found that 54% of respondents may have needed domestic violence–related services at some point during a 3-year period (Meisel, Chandler, & Rienzi, 2003). In a study of Michigan TANF recipients, Tolman and Rosen (2001) found that nearly 25% of welfare clients had experienced threats or physical violence from a partner within the past year, and that 15% had experienced severe physical violence. Research in Texas found an even higher number of women reporting current violence from a partner, ranging from 67.3% to 69.2% (Honeycutt, Marshall, & Weston, 2001). Honeycutt et al. go on to report that past victimization is associated with unemployment for white women, whereas current partner abuse decreases employment for Latina women. However, for African American women, neither past nor current victimization is associated with employment.

Despite these high rates of reported violence among welfare research subjects, exploratory studies with welfare clients indicate that women are rarely receiving assistance through the FVO (Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Postmus, 2003). For instance, studies in Texas (Lein, Jacquet, Lewis, Cole, & Williams, 2001), Chicago (Levin, 2001), Maryland (Hetling & Born, 2005), and Georgia (Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2005) report between .5% and 3% of clients received domestic violence services or work requirement waivers in these welfare systems. Although policymakers have indicated an intent to identify and respond to domestic violence in the TANF program, these studies suggest that the welfare system identifies and responds to very few victims. One of the puzzles related to implementation of the FVO is why so few victims are being recognized and offered services when potentially one fifth (and maybe more) of the caseload should be eligible for assistance because of current domestic violence. This situation raises the question of whether and how workers in welfare systems are implementing the FVO.

The foundation for the delivery of services through the FVO is the identification of domestic violence among welfare recipients. Screening is the practice of asking women about their safety, risk for, and history of domestic violence to identify women who have potentially been victims (Hamberger & Phelan, 2004). The purpose of screening for abuse is to accurately and efficiently identify abused women with the ultimate goal being safety and injury prevention for survivors (Leconte, Bland, Zaichkin, & Hofheimer, 2004). Research in health, mental health, and other settings indicates that survivors usually do not voluntarily disclose information about abuse to service providers (Ellsberg, Heise, Pena, Agurto, & Winkvist, 2001; Hamberger & Phelan, 2004), so identifying abused women requires that frontline workers learn strategies for asking about this experience. Frontline workers in welfare offices play a pivotal role in the detection and response to domestic violence, and their screening procedures are a critical factor in identifying survivors and connecting women to appropriate services. Research and practice indicate that screening should be universal to be effective (American Medical Association, 2003; McCloskey & Grigsby, 2005; Taket et al., 2005). Even if screening is universal, victims may not be identified if the procedures used fail to create the necessary trust between client and worker, or do not provide information that allows a woman to judge the risks and benefits of disclosure. The FVO legislation also indicates that screening should be universal, but whether this is happening and how these practices have been implemented are largely unknown.

Previous research on the FVO implementation practices of welfare staff has been hampered by two significant methodological constraints. First, earlier studies on implementation of the FVO (Lein et al., 2001; Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Postmus, 2003) have relied on post hoc reports of events from battered women and welfare workers rather than on observations of interactions to determine whether appropriate services have been offered. Second, with the exception of a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services within the first year of the implementation of the FVO (Burt, Zweig, & Schlicter, 2000), other research on the FVO has focused on single states, and sometimes on single counties or jurisdictions within the state. To date, no studies have evaluated screening practices across multiple sites. The purpose of this article is to: (a) synthesize findings from current research on the factors that improve the likelihood that women will reveal their domestic violence experiences to service personnel, and (b) use the guidelines drawn from this review to evaluate domestic violence screening practices occurring in interviews between workers and clients in 11 welfare offices in four states.

Background

Identification of domestic violence is the necessary first step in providing women with appropriate services through the FVO, but disclosure of abuse is not easy or automatic for several reasons. First, many women conceal the experience of abuse because they fear retaliation from the batterer (Gerbert et al., 1996; Gondolf, 1998; Smith, 1994). In other cases, women are engaged in a cognitive process to interpret their partner’s behavior as abusive (Lindhorst, Nurius, & Macy, 2005), and at points in this process, they may deny or minimize their own experience (Gondolf, 1998; Smith, 1994). Finally, women have to cope with distressing feelings generated by the abuse (Ellsberg et al., 2001; McCloskey & Grigsby, 2005; Smith, 1994), including embarrassment and shame (McNutt, Carlson, Gagen, & Winterbauer, 1999) that make evoking the topic painful. Evaluating whether to disclose abuse has been likened to a “dance” (Gerbert et al., 1996) in which women actively negotiate the risks and benefits of revealing this information to others. But it is a dance that is facilitated by certain skills and behaviors on the part of frontline workers, which we describe next.

Promoting Disclosure of Domestic Violence Through Effective Screening Practices

Through a review of professional guidelines and empirical research related to domestic violence screening from a variety of disciplines, we have identified eight general practices that support disclosure of domestic violence (see Table 1). These practices are applicable to screening and connecting victims to assistance in any service setting and are relevant to screening for domestic violence in public welfare offices.

Table 1.

Summary of Professional Screening Practices That Support Disclosure of Abuse

|

To create an environment that supports disclosure of abuse, the service provider needs to build rapport through the use of active listening and empathetic reflection skills (Davies, 2000). Given women’s legitimate safety concerns, trust in the professional who is soliciting the disclosure becomes a crucial issue for many women (Ellsberg et al., 2001; Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Postmus, 2003). When professionals appear uninterested or uncaring, abused women perceive them as untrustworthy and are unlikely to disclose their situation to them (Ambuel, Hamberger, & Lahti, 1997; Gerbert et al., 1996). Rapport is a necessary foundation to encourage voluntary disclosure of abuse. Rapport is characterized in human services as the capacity to listen attentively to another and to provide accurate empathetic understanding of the person’s situation (Shebib, 2003). In a recent evaluation of worker training in domestic violence (Saunders, Holter, Pahl, Tolman, & Kenna, 2005), clients reported that helpful workers were “understanding and empathetic … kind and compassionate … very caring and supportive” (p. 249), whereas unhelpful workers were insulting, didn’t remember what the client had said, and were unresponsive. For these women, rapport building is clearly important to establishing a relationship that supports discussion of domestic violence.

For battered women, ensuring that any discussion about abuse is confidential is necessary to prevent the possibility of additional harm occurring as a result of the disclosure (Hamberger & Phelan, 2004). Domestic violence advocates recommend that direct service providers talk with women privately about confidentiality and its limits prior to asking women about abuse (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2004). Battered women who have chosen not to disclose their abuse to welfare workers have reported concerns about confidentiality as a primary deterrent to disclosure (Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Postmus, 2003; Raphael, 2000). Without assurances that information regarding abuse will be kept confidential, many women will have little incentive to honestly answer questions about victimization.

In addition to assurances about confidentiality, women also need an explanation about how disclosure of domestic violence could affect the services they are receiving and how this could be beneficial. Some battered women report that they fear any disclosure of abuse will result in their children being taken away or in further institutional hassles (Postmus, 2003). Clients need specific information about how they will benefit from disclosing information about abuse to professionals. Through the FVO, women who report abuse are eligible for waivers from stringent new regulations implemented under welfare reform such as time limits, work requirements, and child support enforcement. For women struggling with physical injury, mental health sequelae, or whose batterer continues to endanger them, the services offered through the FVO can be of direct benefit. Women need information about benefits to weigh against their perceptions of the risk of disclosure as they evaluate whether to discuss abuse with a worker.

Research contrasting methods for uncovering abuse in professional encounters indicates that women are more likely to divulge this concern if asked directly during the interview (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2004; Morrison, Allan, & Grunfeld, 2000; Saunders et al., 2005; Taket et al., 2005). Asking directly also results in greater numbers of women disclosing domestic violence than using written formats such as check-off forms (Campbell, 2000; McClosky & Grigsby, 2005). The majority of battered women report that they would provide information about the abuse only when directly asked (Caralis & Musialowski, 1997; Hayden, Barton, & Hayden, 1997). Women are comfortable with healthcare professionals asking about abuse as part of a routine examination (Friedman, Samet, Roberts, Hudlin, & Hans, 1992; O’Leary, Vivian, & Malone, 1992), but similar information is not available about public welfare settings.

Methodological studies also indicate that women are more likely to report domestic violence when abuse is defined broadly to include sexual assault (Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002) and tactics of intimidation, humiliation, and isolation that produce feelings of fear (Smith, Smith, & Earp, 1999) in addition to physical violence. In many battering relationships, physical assaults happen episodically with the batterer enforcing control through the more frequent use of intimidation and threats (Gondolf, 1998). Discussions that define abuse as a pattern of behavior broader than physical assault alone help women to identify whether their relationship is characterized by behaviors consistent with domestic violence (Bonomi, Allen, & Holt, 2005). Others also suggest asking women specifically about the ways that their partners may interfere in their work activities (Brush, 2002; Riger, Ahrens, & Blickenstaff, 2000), an assessment that would be particularly appropriate in welfare offices.

When women are asked if they self-identify as a victim of violence, they are less likely to disclose abuse. For instance, Hamby and Gray-Little (2000) found that among women who reported that physical force was used in their current relationship, only one quarter labeled themselves as battered, and 37% thought they were a victim of violence. These findings are consistent with other research that indicates women will not endorse labels such as “battered woman” because they are associated with a stigmatized status (Hamberger & Phelan, 2004; World Health Organization, 2001). Because women who are abused may not identify themselves as victims, most researchers and practitioners suggest using behaviorally anchored questions that are concrete and easy to understand to screen for domestic violence (Ellsberg et al., 2001; Gondolf, 1998; Krug et al., 2002). For example, the widely used Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) asks about a list of physically abusive behaviors such as being slapped, beaten up, or having a weapon used against oneself. Although behaviorally oriented questions may be more effective at eliciting disclosure than those that ask women to label themselves as a victim, they may preclude a woman from disclosing domestic violence if the abusive behavior her partner uses is not in the inventory (Bonomi et al., 2005). These findings suggest that the most effective strategy to promote disclosure of abuse is to combine both open-ended questions regarding threat and safety with behaviorally anchored questions regarding specific forms of abuse (Feldhaus et al., 1997).

Finally, asking about abuse should not be a one-time event in an interview (Allard, Abelda, Colten, & Cosenza, 1997), nor should it happen only once during the course of a professional relationship (Ellsberg et al., 2001; Gondolf, 1998; McCloskey & Grigsby, 2005). For women engaged in the “dance of disclosure” (Gerbert et al., 1996) related to domestic violence, it may take several screening attempts on the part of the professional before a woman is able to discuss her situation openly. When organizational practices limit discussion of domestic violence to intake interviews, or to single questions within those interviews, many women who are in need of services are likely to be missed.

Research Questions

In passing the FVO, policymakers explicitly recognized the special circumstances and needs of domestic violence victims, and the potential of the welfare system to serve as a point of identification and service referral. Despite the availability of the FVO, initial reports suggest that few clients take advantage of these services. This study addresses gaps in knowledge about whether and how frontline workers in welfare offices are implementing basic screening procedures to identify domestic violence. We analyze detailed information on interactions in light of what is known about effective screening practices through which social agencies and workers help survivors disclose sensitive and potentially stigmatizing information and seek appropriate help. Given the importance of knowing both whether and how these practices occur, this research uses a simultaneous mixed-methods approach (Newman, Ridenour, Newman, & DeMarco, 2003) to address the following questions:

How frequently are frontline workers screening for and identifying domestic violence among TANF applicants and recipients?

What organizational, staff, and client characteristics are associated with the probability of screening?

To what extent do frontline workers conduct these screenings using techniques that have been found to encourage disclosure?

Method

Study Sample

The sample for this study consists of 782 transcribed observations of interviews between welfare and employment services workers and female clients originally collected as part of the Frontline Management and Practice Study conducted by the Rockefeller Institute of Government for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (for further description of the study, see Meyers & Lurie, 2005; Meyers, Riccucci, & Lurie, 2001).1 The present research is a subanalysis of the larger study which was designed to assess the implementation of welfare reform policies in welfare offices that varied on a range of policies following PRWORA. The research design for the study maximized organizational variation by drawing samples in three stages.

The first stage used a purposive sampling approach to select four states for inclusion in the study based on variation in location, political culture, and TANF agency structures. The second stage used a purposive sampling approach to select 11 sites (2 to 3 per state) that represented urban and either rural or suburban locations in each state.

The states chosen were Georgia, Michigan, New York, and Texas. States’ monthly benefits under the TANF program varied from $201 per month for a family of three in Texas to $577 in New York. States also differed in their organization of welfare and employment services. Each state had adopted a “work first” approach for TANF intake that encouraged or required individuals to seek employment before their TANF application could be approved. The extent and duration of these application requirements varied. New applicants were required to attend a Work First orientation in all states and to participate in more intensive job-readiness assessments and supervised job searches in some. States also varied in the division of responsibility between welfare and employment services agencies. In all states, welfare agency staff determined eligibility for TANF, along with Medicaid and Food Stamps, and monitored compliance with various TANF eligibility requirements. In Georgia, these staff also conducted initial employment assessments, provided job readiness activities, managed child care subsidies, and referred TANF applicants and clients to the public employment agency for more specialized assistance. In Texas, welfare agency staff referred new applicants to local employment agencies (including public, nonprofit, and for-profit contractors) for employment assessments, job preparation activities, employment referrals, and child care subsidies. Each site selected in the second stage of sampling included the public welfare agency providing both TANF cash benefits and the associated public, nonprofit, or for-profit employment service agencies.

Although states varied on some dimensions of TANF and Work First policies, all had adopted FVO policies. Georgia, New York, and Texas formally adopted the FVO by 1998 and certified that they had implemented the policy (DHHS, 1999), and Michigan adopted policies that were similar to the FVO (Saunders et al., 2005). Each state implemented the FVO at least 1 year prior to the beginning of data collection for this study. All four states agreed to provide the core components of the FVO, namely, to screen applicants for domestic violence, refer identified victims to counseling and community services, and offer waivers to TANF program requirements if these would improve the woman’s safety (DHHS, 1999).

In the third stage of sampling, a stratified quota sample was constructed for direct observation of interactions between a random sample of frontline workers and TANF applicants or clients in each site. As described below, the goal of data collection was to collect detailed information about the content of face-to-face encounters between welfare staff and individuals who were applying for or receiving TANF assistance. The direct-observation sample was designed to collect this information for a representative sample of encounters, based on the usual amount of time per week that workers in both the welfare agencies and associated employment agencies spent in face-to-face contact with TANF applicants or clients. The sample was designed to be representative of both the allocation of staff across positions and the allocation of direct client contact time across various activities (e.g., intake interviews, screening and assessment, employment services, and client monitoring). To construct the observation sample, data from a time-use survey (completed by all frontline staff) were used to calculate the total hours that all frontline workers (in welfare and employment services agencies) typically spent in direct contact with TANF applicants or clients at the site level. A stratified quota sample for hours of direct observation, generally 60 hours per site, was calculated to allocate hours of observation in proportion to hours that frontline staff in each position with each agency (e.g., case manager, eligibility specialist) contributed to total worker-client contact hours during a typical week at the site level. To balance observation time across positions that varied in number of staff and usual client contact hours, the quota sample was adjusted by the square root of the time that staff in each position contributed to the site-level total. Individuals within each position were then randomly selected for observation at each location. Selected individuals were observed for a minimum of 3 hours and a maximum of 6 hours, until the quota of observation hours for the position was reached. Data collected during these observations were weighted at the time of analysis to adjust for sample stratification at the site and staff position levels using the inverse of the factors used to stratify the initial quota samples (e.g., number of staff in each position and their contribution to total worker-client contact time at the site level). When weighted, the observation data are representative of the transactions between frontline workers in welfare and employment services agencies and TANF applicants and recipients in the four states. Observations took place from November 1999 to August 2000. A total of 969 encounters were observed and their content transcribed. For this analysis, 744 encounters were analyzed that involved interviews with women in these offices.

Data Collection

Observational data were originally collected for other purposes and were reanalyzed for this article. Encounters between clients and workers were observed in both welfare and employment services offices and included a range of purposes, such as application for TANF, arranging child care services, development of employment plans, and discussion of sanctions. During the observation periods, research assistants sat in on all meetings between the target worker and TANF applicants and clients. Prior to each encounter, informed consent was obtained for observation from the client who would be observed; refusals by either staff or clients were minimal. Research assistants tape-recorded and transcribed data from the encounters in Texas, Michigan, and one New York agency. In Georgia and the remaining agencies in New York, we were unable to obtain permission to tape-record encounters. In these sites, research assistants were instructed to record verbatim 25 topics of conversation and activities that were of particular interest, including domestic violence. Analysis of transcripts suggests some underrecording by the observers taking handwritten notes, thus introducing the possibility of bias in the data.2

Research assistants observed worker-client interactions in the usual settings for these encounters in each agency, including waiting rooms and interactions with receptionists and other intake staff, individual meetings between frontline workers and applicants or clients, and group meetings or orientations conducted by welfare or employment services staff. In this analysis, 758 of the 782 transactions were between individual frontline workers and their clients; the remaining 24 were group orientations or reception-desk encounters. Meetings between workers and clients were typically conducted at the workers’ desks in cubicles separated by dividers. Workers sat at their desks and used desktop computers to enter data collected during the interview and to print out forms for the applicants. On occasion, workers placed or received phone calls and left the cubicle to get or copy printed documents. Applicants were generally alone, but occasionally were accompanied by their children and, in rare cases, by another adult family member, translator, or other individual. After obtaining permission to observe and record (or transcribe) the encounter, the research assistant sat to the side of the cubicle and refrained from interacting with either the worker or the applicant.

In addition to the transcribed interviews, data were also collected on the client’s ethnicity and gender, and the worker’s ethnicity, gender, and length of employment with the agency. Data on gender and ethnicity were missing in 15.6% of cases, so in those analyses, the sample is restricted to the 660 observations in which these variables were coded. The research assistant also identified the primary purpose of the encounter: application or recertification for TANF; employment services activity such as job search, assessment, or orientation; or other visit types, namely child care applications or sanction/compliance hearings.

Data Analysis

Each client-worker interaction was transcribed and coded using the qualitative software program ATLAS.ti (Muhr, 2005). Discussions related to domestic violence were coded in the following fashion. First, all transactions were read and coded as “domestic violence screening” if the worker asked the applicant about safety at home, history of abuse, or domestic violence. A transaction was coded as “domestic violence identified” if the client indicated that she had been abused or sought services for domestic violence from the worker.

For the first two quantitative research questions that assess the frequency of and factors associated with screening, coded cases were imported into SPSS for statistical analysis. The small amount of screening for and identification of domestic violence required that we use analysis strategies appropriate for smaller cell sizes. For tests of association, we employed Exacon (Bergman & El-Kouri, 1998), a procedure that uses a Fisher’s exact test based on a hypergeometric distribution for calculating chi-square values for cells having fewer than five observations. Where appropriate, we use t tests to evaluate differences in means, and logistic regression to estimate the odds for screening activities.

To evaluate our third research question regarding the extent to which welfare workers conduct screenings using techniques that encourage disclosure of abuse, we undertook further qualitative analysis of the 73 cases in which the worker screened for domestic violence. Two of the authors read and coded each of these transcripts for processes occurring within the transaction that would affect client disclosure of domestic violence. Each case was coded for whether it utilized the strategies that promote disclosure of domestic violence identified in Table 1. Those cases that did not use at least two of the supportive screening practices identified in Table 1 were further analyzed for the types of behaviors associated with statements related to domestic violence. From this we categorized interviews as helpful, routinized, or informing without screening based on the statements and process of the interview.

Results

Results of Quantitative Analysis

Of all client contacts, only 1.2% screened for and identified domestic violence. Only 9.3% of all case encounters involved screening by the frontline worker for domestic violence, and clients reported being a victim of domestic violence in 13.7% of these transactions. Although screening happened infrequently, its presence increased the odds that domestic violence would be identified during a client interaction (OR = 6.60, 95% CI, 2.87–15.16, p < .001). Based on the most conservative prevalence estimate that 25% of welfare clients experienced physical violence in the preceding year (Tolman & Rosen, 2001), 86% of women who were likely abused were not identified through welfare office screenings.

Rates of screening varied with organizational and worker characteristics. Screening differed significantly between states (x2 = 77.93, df = 3, p < .001), with Georgia reporting the highest level of screening at 28.8%; Michigan, 7.5%; New York, 4.9%; and Texas, 2.9%. Although some states have assigned portions of the TANF application process to employment services offices, these offices are not implementing domestic violence screening (x2 = 18.61, df = 1, p < .001). Further analysis shows that screening was more likely to occur in initial application or recertification visits, and job search activities rather than child care, sanction, or compliance visits (x2 = 14.14, df = 2, p < .001). Workers who screened for domestic violence reported an average length of employment with the agency of 5.07 years compared to 7.29 years for those workers who did not screen (t = 2.478, p < .01). Screening was not associated with either the worker’s or client’s ethnicity or gender, nor with the urban or rural/suburban location of the welfare office (results not shown). Sample characteristics and associations between screening and organizational and caseworker variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Association Between State, Organization, and Worker Characteristics and Domestic Violence (DV) Screening (n = 782)

| Sample Total (%) | DV Screen by Caseworker

|

Test Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No (%) | Yes (%) | ||

| State | 77.93**

(X2 df = 3) |

|||

| Georgia | 17.8 | 71.2 | 28.8 | |

| Michigan | 27.3 | 92.5 | 7.5 | |

| New York | 28.8 | 95.1 | 4.9 | |

| Texas | 26.1 | 97.1 | 2.9 | |

| Office type | 18.61**

(X2 df = 1) |

|||

| TANF office | 81.2 | 88.5 | 11.5 | |

| Employment services | 18.8 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |

| Encounter type | 14.14**

(X2 df = 2) |

|||

| Initial application or recertification | 64.9 | 88.4 | 11.6 | |

| Job search activity | 12.0 | 87.9 | 12.1 | |

| Other encounter (sanction, child care, etc.) | 23.1 | 97.8 | 2.2 | |

| Worker length of employment | 7.12 (6.93) | 7.29 (7.05) | 5.07 (5.00) | 2.47* a |

Note: Cases weighted to be representative of direct service contact; TANF = Temporary Assistance to Needy Families.

. t-test statistic reported.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

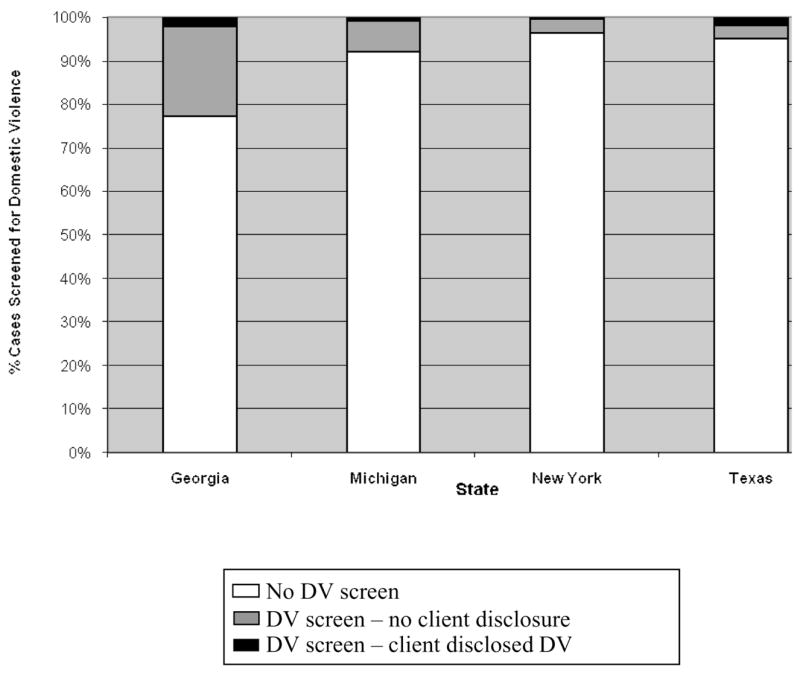

As can be seen in Figure 1, the vast majority of contacts between frontline workers and clients included no screening for domestic violence. Although screening practices differed across states, these differences did not produce appreciable variation in the amount of domestic violence disclosed by TANF recipients (see Figure 1). Although Georgia had the highest rate of screening activity among workers, its identification of domestic violence survivors (2.2%) was similar to Texas (2.0%), which had a much lower screening rate. Michigan and New York identified little domestic violence, at .9% and .4%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Screening and Identification of Domestic Violence in Four States

Note: Cases weighted to be representative of direct service contact.

Results of Qualitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis indicates that domestic violence screening was rare and disclosure even less common. Although domestic violence was more likely to be revealed during an encounter that included screening, overall, rates of screening were not associated with rates of disclosure. This suggests that screening for domestic violence was not only uncommon but also not very effective. To consider why, we turn to in-depth analysis of 73 instances in which workers did screen for domestic violence.

As a context for effective screening for domestic violence, these encounters have some notable characteristics. First, they were often a first encounter between the individual worker and client. They were also highly routinized and scripted by program procedures, for example, collecting information to determine TANF eligibility or providing clients with information about program rules and regulations. Furthermore, these interactions rarely included any discussion of confidentiality, an important precondition for disclosure of sensitive information and a specific requirement under the FVO. Out of 782 interviews, discussions of confidentiality occurred in only 28 (4%) of the encounters. In general, conversations between frontline workers and clients began with eligibility questions (details about the client’s household) or instructions regarding TANF regulations. Interviews did not begin with a discussion of confidentiality.

In-depth analyses of the 73 cases where domestic violence was discussed indicated that the screening practices identified in Table 1 as supporting disclosure were rarely implemented. The most common practice used was to ask directly about abuse; this happened in 42 out of 73 cases (57.5%). However, further analysis of these interviews showed that in the majority of the cases, this was accomplished by asking women if they were “victims of domestic violence,” forcing women to identify themselves with a stigmatized status. Given that supportive screening practices occurred infrequently, we further analyzed the interviews for other processes that might explain why disclosure of domestic violence was not occurring, even in interviews where domestic violence was being mentioned.

Close reading of the interviews identified three different processes occurring in the interactions between clients and frontline workers. First, in 13.9% of the screening transactions (representing 1.2% of the total client-worker transactions), workers asked directly about abuse and employed at least one other strategy identified in Table 1 that may promote disclosure of abuse. We classify this set of interviews as having helpful screening practices, and describe the other screening strategies used by these workers below. The second process we describe as routinization, and this occurred in 43.8% of encounters where screening took place (3.9% of the total transactions). In routinized screening, workers ask directly about domestic violence, but do not use any other strategy that would facilitate disclosure by a battered woman; in fact, workers usually used screening strategies that are ineffective. Finally, we identify a third process occurring in 42.3% of interviews (3.8% of total interviews), which we label as informing without screening. In these encounters, workers mention domestic violence, but employ discrete strategies that restrict the likelihood that a client will disclose information about abuse. A chi-square comparison of differences in rates of disclosure showed that significant differences exist between which screening strategy was used and whether a client disclosed domestic violence (x2= 35.73, df = 2, p < .001). Helpful screening practices were employed in 77.8% of the cases where domestic violence was revealed by clients. Interestingly, routinized screening produced no disclosures from clients, whereas 2 clients revealed abuse whose workers used techniques of informing without screening.

Helpful Screening Practices

In the 10 helpful transactions, workers used a variety of additional strategies to support disclosure of domestic violence by clients, but no worker used all of the strategies. In half the cases, workers explained the reasons why disclosure of abuse might be beneficial to the client. In 3 cases, workers defined abuse broadly, and in 2 cases, they used empathetic reflection to build rapport. In 1 case each, workers ensured that a disclosure of abuse would be confidential, used open-ended probes to ask about abuse, and phrased questions in such a way as to avoid forcing women to identify with a stigmatized status. The worker in the following explanation incorporates four of these strategies into her discussion of domestic violence with the client. First, she defines abuse broadly, focusing on the emotional experience of fear before asking about violence. Then she asks about abuse directly, but in such a way as to avoid forcing the woman to identify with a stigmatized status. Finally, the worker then tells the client how she would benefit from making a disclosure.

W: OK. I have a couple more forms to get you to look at. The first talks about domestic violence and TANF, ways that you can determine if you’re in a domestic violence situation—are you afraid at home? Do you feel threatened? Is he violent? Etc. If you do fit any of these qualifications, we may be able to waive some requirements. (GA080)3

By demonstrating sensitivity to the underlying emotional concerns of fear and threat involved in domestic violence, this worker also signals her capacity to understand difficult feelings, a necessary component of rapport building. The worker does not explain what she means by waiving requirements, but she has indicated that there may be a benefit to the client in reporting if domestic violence is happening.

Other workers also phrased their requests for information in terms that indicated a broader definition of abuse. Some asked questions such as, “Are you and your baby in any sort of danger?” (GA259), or “Was there ever any emotional or sexual abuse or physical abuse going on?” (MI262). In these instances, workers are using questions that avoid having the client identify with a stigmatized status. These techniques define abuse as more than just physical violence. When linked to an expression of concern for the safety of the client from the worker, these screening techniques may create a more favorable environment for disclosing domestic violence.

Routinization of Screening for Domestic Violence

Workers classified as using routinized screening asked directly about abuse, but they often did so in ways that were in conflict with the strategies for promoting disclosure summarized in Table 1. We provide examples in which: (a) the worker asks about domestic violence in a way that forces the client to identify with a stigmatized status, (b) the worker and client do not appear to share an understanding of the term domestic violence, (c) the worker fails to provide a rationale for why the woman should reveal abuse, and (d) the worker fails to build rapport with the client that could facilitate disclosure.

Welfare workers who screened for domestic violence in a routinized way commonly asked clients questions such as, “Is there any domestic violence?” or “Are you a victim of domestic violence?” or “Is domestic violence an issue for you?” In routinized transactions, asking about domestic violence is embedded within a series of closed-ended questions as is seen in the following excerpt from an application interview. Dozens of closed-ended questions preceded and followed this section of the interview. This passage is a typical example of a routinized screening transaction.

W: What about your budgeting? Do you pay your bills timely or is that an issue for you, something you need to work on?

C: I guess I pay the most important ones.

W: Okay. That’s what I do too. How about prayer and attending church?

C: Not too often.

W: OK. And your parenting skills? Setting limits? Are you consistent, or are you lax, or how would you describe your parenting?

C: I wouldn’t say I’m lax.

W: OK.

C: I’d say I’m good; I’m a good parent.

W: OK. Domestic violence, has it even been an issue for you?

C: No.

W: What about substance abuse?

C: No. (MI077)

This interview epitomizes many of the issues with discussions of domestic violence among those interviews classified as routinized. First, abuse is not defined, and instead the worker is asking the client to identify with the label domestic violence. The worker provides no rationale for why she has asked this question, or what the consequences would be for the client if she answered affirmatively. This is the only time and the only strategy the worker uses to ask about domestic violence in this interview. Although screening for domestic violence has technically occurred here, the likelihood that a victim would disclose under these circumstances is remote.

Questions such as, “Is domestic violence an issue for you?” rest on underlying assumptions that the client: (a) defines the term domestic violence in the way intended by the worker and agency, and (b) that if she is a victim, she recognizes this fact and applies this label to herself. The interview transcripts provide evidence that both these assumptions are faulty. For example, the client’s response in the following transaction raises doubt that she actually understands what “domestic violence” means:

W: Fill out these forms. I know you can’t read, so I’ll explain. Any domestic violence?

C: My husband was killed.

W: Were there survivor’s benefits? (NY783)

Although her husband may have been killed in a domestic violence altercation, it is also possible that the client misunderstood the question to ask whether someone in her household had been killed through violence. The caseworker does not clarify with the client whether she understands the intent of the question, but instead continues with screening for financial eligibility. The approach taken in this interview does not address whether the woman and the caseworker share an understanding of what the term domestic violence means. This caseworker is also unable to ascertain whether there are circumstances in the woman’s life that she does not interpret as abusive but which a professional might.

Without understanding the context of why the worker is asking about domestic violence, clients will likely be reluctant to discuss this with their worker. In the following example, the worker has given a form explaining domestic violence waivers to the client and asks the client if she is “in a domestic violence relationship.” The client says no, but at the end of the interview, the following exchange takes place:

W: Do you have any questions for me?

C: No. Yeah. Why is it that people with domestic violence can’t get TANF?

W: It doesn’t say that—why do you say that?

C: It says here if you’re in a domestic violence relationship, TANF rules don’t apply.

W: You’re still eligible, just some rules may not apply. Now read through this starting here and initial. It talks about what happens if you break the rules. (GA080)

The caseworker does not explain to the client what the form means when it says “some rules may not apply.” Although this client has indicated that she did not understand the original rationale underlying the worker’s question, the worker does not clarify whether the client’s new understanding of the policy would change her response to the screening question.

More broadly, these interviews highlight deficits in rapport building. In the preceding examples, workers ask questions, but do not ascertain whether the client understands what is being asked. The questioning process creates a climate of interrogation rather than one of support. In addition, some workers pair questions related to domestic violence with other TANF instructions to create a situation that is not conducive to disclosing a topic that is potentially painful and/or dangerous. For instance, the worker in the following interaction couples discussions of punitive sanctions under TANF with requests for disclosure about domestic violence.

W: [After discussing family cap,4 personal work requirement, and keeping kids in school.] If you fail to do what Ms. P. tells you, I can close your case.

C: [Nods head.] Yes.

W: Are you a victim of domestic violence?

C: No. (GA241)

In this example, the worker pairs a threat (“close your case”) with a request for information about a distressing topic. Clients who feel intimidated by the discussion of punitive sanctions under TANF are unlikely to disclose highly sensitive information immediately following statements such as these.

Informing Without Screening

In interactions in which clients were informed of the FVO without being screened, clients were usually handed a form about domestic violence, but the worker did not explain or ask about safety or violence at home. In addition, workers adopted practices that precluded disclosure of domestic violence. One such practice was the use of double-barrel questions, questions where welfare workers combined multiple screening questions into one, so it became unclear as to which question the client was answering. Workers in these examples did not follow up to clarify which question the client was answering.

W: Any domestic violence or substance abuse? Okay, now I noticed that when we were doing the form you were saying that the girls do such things as coloring and drawing. What do you do outside as far as do you have any hobbies? (MI068)

W: Do you have a disability or are you a victim of domestic violence? Do you feel you need a waiver? (GA254)

In these instances, workers are asking questions in such a way as to create confusion about which question the client is to answer, so in this transaction, clients make minimal responses. Sometimes workers fulfilled the bureaucratic requirements for paperwork to inform the client of their rights related to domestic violence, without actually screening the client, as is shown in the following excerpt:

W: OK. This is a new form for TANF reviews. This first one is on domestic violence. You don’t have to go to any work activity if you are experiencing domestic violence. We will help you relocate and everything. Sign here.

[C signs.]

W: This is also a new form. It says that if you have any disability we cannot make you participate in any work activity and we cannot deny you benefits.

C: OK.

W: OK, this form right here says that I provided you with the domestic violence and disabilities forms. Check here. This one says that you are not requesting any waiver for either one. Sign and date here.

C: OK. (GA415)

In this example, the worker has documented that the client does not have an issue with domestic violence, when in fact, the worker never asked this. The worker has not explained that the client must use this moment in the interview process to request a waiver, but instead has maneuvered the client through the necessary paperwork without investigating whether it applies to the client. In a related process, some workers prescribed a “no” answer to clients in the screening process.

W: This says you cooperated with us and that you have no domestic violence issues. Do you have any domestic violence concerns?

C: No. (NY787)

Here the worker tells the client that she does not have domestic violence issues before asking her if she does, guiding the client to the desired response. Beach, Easter, Good, and Pigeron (2005) term these “no problem” queries, or questions that are designed “not to invite, but restrict the likelihood that [clients] will further elaborate their circumstances” (p. 906). In these examples, workers provide technical information regarding welfare regulations related to domestic violence, but they are managing the conversations to prevent the client’s potential disclosure of domestic violence. This process typifies workers who not only do not implement effective screening strategies but who create situations in which clients are indirectly instructed not to disclose abuse.

Discussion

Overall, these findings indicate that domestic violence screening rarely occurred in four states which had adopted the FVO or similar policies. Some differences related to state, organization, and worker characteristics were associated with screening rates. However, taken as a whole, the absence of screening is notable across a diverse group of workers, geographical settings, and differing political environments. Although this study was not designed to evaluate organizational views on screening or differences in setting or training, the consistent absence of discussion of domestic violence indicates that deeper systemic issues may be at play. Lindhorst and Padgett (2005) identify organizational factors such as the focus on case closure, lack of time to carry out thorough interviews because of high client-to-staff ratios, and inadequate training in responding to abuse as impediments to screening for domestic violence. Workers have also been found to harbor negative judgments of clients that are communicated directly and indirectly, which act as obstacles to disclosing abuse (Hagen & Owens-Manley, 2002; Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Saunders et al., 2005). Similar structural dynamics may be occurring in the settings under investigation here, and may be pervasive in the current welfare system.

By closely analyzing the ways in which workers discussed domestic violence with clients, we found predictable ways in which these transactions went awry. In those instances in which frontline workers asked about domestic violence, the majority employed screening strategies that were not only ineffective but that also restricted the likelihood that women would reveal their abuse. It seems likely that the lack of rapport building between workers and their clients, coupled with the neglect of confidentiality in these encounters and the lack of effective screening procedures, contribute to the discrepancy between the number of clients identified as survivors of domestic violence by welfare offices and the much larger numbers identified by researchers.

The data from the transactions in this study indicate that in addition to the practices identified in Table 1, other processes are also necessary to promote disclosure of domestic violence in welfare offices. First, agency personnel must ascertain whether they share a common understanding with their clients of what constitutes abuse. Without actively engaging in dialogue around how women define and understand their relationships, screening activities are a hollow activity, bereft of the passion for safety that should infuse their use. Furthermore, agency personnel need to be aware of barriers to disclosure, such as fears related to confidentiality, and actively plan to address these potential barriers with clients.

Although this study focuses on transactions between welfare workers and clients, the findings here are strikingly similar to studies of interactions between physicians and patients around domestic violence. Analysis of barriers to screening in medical settings indicates that medical personnel report systemic problems such as the time available for assessment, inadequate education about screening and intervention, and lack of continuity with patients (McCauley, Yurk, Jenckes, & Ford, 1998) that are similar to the constraints faced by welfare workers (Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005). Researchers have also found that physicians routinely miss opportunities to build rapport with patients, opting instead to employ questioning techniques that emphasize expertise and biomedical priorities (Beach et al., 2005). Workers in this study similarly neglected rapport-building processes, focusing instead on technical aspects of eligibility determination. It may be that these practices are indicative of barriers to screening in welfare offices and medical practices, which reflect larger structural problems of overtaxed bureaucratic systems.

Research on domestic violence screening in medical systems provides further evidence that organizations can provide support to ensure that protocols are implemented (Larkin, Rolniak, Human, MacLeod, & Savage, 2000). For example, detection of domestic violence increased from 5% to 30% in an emergency department during the period when the screening protocol was being monitored through quality improvement activities (McLeer, Anwar, Herman, & Maquiling, 1989). Once the protocol was no longer monitored, detection rates fell back below 5%. McLeer et al. (1989) emphasize the role of administrative accountability as a support to the process of implementing screening for domestic violence. At this time, federal legislation requires no accountability for implementation of the FVO, and few states are engaged in any systematic efforts to evaluate worker activities related to the policy. Incorporating standards for screening at the federal level may be a first step to ensuring more uniform adoption of practices that would support domestic violence survivors in welfare settings.

In addition to instituting screening and FVO implementation monitoring standards, additional potential interventions are implied by these findings. The low rate of worker adherence to screening practices that facilitate disclosure suggests the need for domestic violence–specific training for welfare office staff. One published evaluation of a welfare staff training suggests that training programs can increase the likelihood that frontline workers will discuss abusive behavior and help women develop safety plans (Saunders et al., 2005). Our findings indicate that workers need training that builds skills in consistently and directly asking about abuse, avoiding the use of stigmatizing labels, asking behaviorally specific screening questions, and clarifying both the definition of abuse and why disclosures of abuse might benefit victimized clients. Other researchers have worked to refine measures of work-related abuse that offer specific methods of assessing an aspect of domestic violence that has direct relevance to the work occurring between frontline welfare workers and their clients (Brush, 2002; Riger et al., 2000). Both individual workers and welfare offices more generally could enhance the likelihood of disclosure of domestic violence by explicitly communicating confidentiality policies and by providing private spaces for discussion of sensitive topics. Finally, ongoing training for workers in rapport-building skills such as active, empathetic listening and nonjudgmental responses might benefit all client-worker interactions, including those that hold the potential for a disclosure of domestic violence.

Limitations

This research is cross-sectional, providing an initial exploration of the processes surrounding implementation of the FVO at a single point in time. Although this snapshot captures realities of the workplace in the first years of the implementation process, it does not reflect any subsequent evolution of procedures as states refine service delivery efforts. In those states where tape-recording was not allowed, the written transcripts may not capture all relevant dialogue, so we may underestimate the frequency of screening in New York and Georgia. Additionally, the transcripts may not always note important nonverbal communication occurring between worker and client that might provide further insight into these transactions. Although these data provide a compelling picture of implementation activities in 11 welfare offices, the states and offices participating in this study were not randomly chosen, so generalizability of these findings to other states may be limited. The experiences of welfare workers and clients in this study may differ from those in other states, and also in other offices within the states chosen to participate.

Conclusion

Insofar as poor battered women with children have few viable alternatives for seeking financial assistance to escape abusive relationships, they will be seen in welfare offices. Workers in these offices have the opportunity to promote discussions of domestic violence that will assist women to obtain the resources they need to be safe and to become truly self-sufficient. Unfortunately, the findings from this study raise concerns about the capacity of welfare offices to appropriately screen for the safety concerns of battered women. It may not be possible for welfare offices to serve two contradictory missions, that of supporting women in their efforts to end abuse while simultaneously attempting to decrease welfare caseloads. Without stringent mandates to focus on safety and support for battered women coupled with administrative accountability for both these activities, battered women may be safer continuing their own strategies of nondisclosure to welfare workers.

Biographies

Taryn Lindhorst, Ph.D., LCSW is an Associate Professor of Social Work at the University of Washington. Dr. Lindhorst’s work is informed by 16 years of social work practice experience in public health settings. Her research focuses on organizational practices and policy implementation, particularly as this relates to issues of violence and poverty for women. Dr. Lindhorst’s work on the effects of welfare reform for battered women has won two national awards, and her research has been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Justice. Her current projects include a longitudinal analysis of the long-term impact of domestic violence on economic and mental health outcomes among adolescent mothers, and a qualitative study with battered women who have been prosecuted for child abduction under the international Hague Convention treaty.

Marcia K. Meyers is Professor of Social Work and Public Affairs at the University of Washington. She earned an M.P.A. at Harvard University and an M.S.W. and Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Meyers’ research focuses on public policies and programs for vulnerable populations, with a particular focus on issues of poverty, inequality, and policy implementation. Current research projects examine variation in the “package” of social assistance available to low income families in the U.S. and the impact of U.S. state policy regimes on labor force participation and child care arrangements. She has also conducted cross-national comparative research on social and family policy, and is the co-author of Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment—a comparative study of the role of work/family reconciliation policies in promoting gender equality and child well-being in 12 industrialized countries.

Erin Casey, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Social Work at the University of Washington, Tacoma. She received her M.S.W. and Ph.D. in Social Welfare at the University of Washington, Seattle, and has over 10 years of practice experience in the fields of domestic and sexual violence. Erin’s research interests include the etiology of sexual and intimate partner violence perpetration, and examining ecological approaches to violence prevention. She was awarded a 2006 Guggenheim dissertation fellowship for her research on ecological conceptualizations of sexual violence and sexual violence prevention.

Footnotes

This research was originally presented at the 4th Trapped by Poverty/Trapped by Abuse Conference in October 2003 in Austin, TX. The authors would like to thank Irene Lurie for her efforts in the implementation of the research and Sharon Chung for assistance in early analyses of the data.

The term client in this article refers both to applicants for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and to recipients.

To assess for possible under-recording effects, we reproduced the analyses excluding the site in which data were most limited by reliance on observer notes (Albany, NY). The results were the same.

Alphanumeric codes after quotations denote state and interview identification number.

A welfare reform policy that allows states to limit the amount of cash assistance a family can receive when an additional child is born.

References

- Allard MA, Albelda R, Colten ME, Cosenza C. In harm’s way? Domestic violence, AFDC receipt and welfare reform in Massachusetts. Boston: University of Massachusetts, Boston, Center for Survey Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ambuel B, Hamberger LK, Lahti JL. The family peace project: A model for training health care professionals to identify, treat and prevent partner violence. In: Hamberger LK, Burge S, Graham A, Costa A, editors. Violence issues for health care educators and providers. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 1997. pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Policy statement on family and intimate partner violence, H-515.965. Chicago: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Easter DW, Good JS, Pigeron E. Disclosing and responding to cancer “fears” during oncology interviews. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:893–910. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, El-Kouri BM. SLEIPNER. A statistical package for pattern-oriented analyses (Version 2.0) [computer software] Stockholm, UK: Stockholm University, Department of Psychology; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Allen DG, Holt VL. Conversational silence, coercion, equality: The role of language in influencing who gets identified as abused. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.022. Unpublished paper. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandwein R. Family violence and welfare use: Report from the field. In: Brandwein R, editor. Battered women, children and welfare reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brush LD. Work-related abuse: A replication, new items and persistent questions. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:743–757. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.743.33720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR, Zweig JM, Schlicter K. Strategies for addressing the needs of domestic violence victims within the TANF program: The experience of seven counties Report to U.S. DHHS. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Promises and perils of surveillance in addressing violence against women. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:705–727. [Google Scholar]

- Caralis PV, Musialowski R. Women’s experiences with domestic violence and their attitudes and expectations regarding medical care of abuse victims. Southern Medical Journal. 1997;9:1075–1080. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. Recommendations for training TANF and child support enforcement staff about domestic violence. Harrisburg, PA: National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; 2000. Retrieved October 31, 2005, from http://www.vawnet.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: Methodological and ethical considerations. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Violence Prevention Fund. The national consensus guidelines on identifying and responding to domestic violence victimization in health care settings. San Francisco: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus K, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency room. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LS, Samet JH, Roberts MS, Hudlin M, Hans P. Inquiry about victimization experiences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1992;152:1186–1190. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.6.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Johnston K, Caspers N, Bleecker T, Woods A, Rosenbaum A. Experiences of battered women in health care settings: A qualitative study. Women and Health. 1996;24:1–17. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW. Assessing woman battering in mental health services. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. State approaches to screening for domestic violence could benefit from HHS guidance. GAO-05-701. Washington, DC: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen JL, Owens-Manley J. Issues in implementing TANF in New York: The perspective of frontline workers. Social Work. 2002;47:171–182. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger KL, Phelan MB. Domestic violence screening and intervention in medical and mental healthcare settings. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL, Gray-Little B. Labeling partner violence: When do victims differentiate among acts? Violence and Victims. 2000;15:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden SR, Barton ED, Hayden M. Domestic violence in the emergency department: How do women prefer to disclose and discuss the issues? Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1997;15:447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetling A, Born CE. Examining the impact of the Family Violence Option on women’s efforts to leave welfare. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15:143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt TC, Marshall LL, Weston R. Toward ethnically specific models of employment, public assistance and victimization. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. Violence by intimate partners; pp. 87–122. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin GL, Rolniak S, Human KB, MacLeod BA, Savage R. Effect of an administrative intervention on rates of screening for domestic violence in an urban emergency department. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1444–1448. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leconte JM, Bland PM, Zaichkin J, Hofheimer L. Domestic violence and pregnancy: Guidelines for screening and referral. Olympia: Washington State Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lein L, Jacquet SE, Lewis CM, Cole PR, Williams BB. With the best of intention: Family Violence Option and abused women’s needs. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Levin R. Less than ideal: The reality of implementing a welfare to work program for domestic violence victims and survivors in collaboration with the TANF department. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Nurius P, Macy R. Contextualized assessment with battered women: Strategic safety planning to cope with multiple harms. Journal of Social Work Education. 2005;41:371–393. doi: 10.5175/jswe.2005.200200261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Oxford M, Gillmore MR. Longitudinal effects of domestic violence on employment and welfare outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:812–828. doi: 10.1177/0886260507301477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Padgett J. Disjunctures for women and frontline workers: Implementation of the Family Violence Option. Social Service Review. 2005;79:405–429. doi: 10.1086/430891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “Pandora’s box”: Abused women’s experiences with clinicians and health services. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey L, Grigsby N. The ubiquitous clinical problem of adult intimate partner violence: The need for routine assessment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36:264–275. [Google Scholar]

- McLeer SV, Anwar RA, Herman S, Maquiling K. Education is not enough: A systems failure in protecting battered women. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1989;18:651–653. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt L, Carlson BE, Gagen D, Winterbauer N. Reproductive violence screening in primary care: Perspectives and experiences of patients and battered women. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 1999;54:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel J, Chandler D, Rienzi BM. Domestic violence prevalence and effects on employment in two California TANF populations. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1191–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MK, Lurie I. The decline in welfare caseloads: An organizational perspective; Paper presented at Mixed Methods Research on Economic Conditions, Public Policy and Family and Child Well-being; Ann Arbor, MI. 2005. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MK, Riccucci NM, Lurie I. Achieving goal congruence in complex environments: The case of welfare reform. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2001;11:165–201. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LJ, Allan R, Grunfeld A. Improving the emergency department detection rate of domestic violence using direct questioning. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2000;19:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(00)00204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. ATLAS.ti. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Newman I, Ridenour CS, Newman C, DeMarco GMP. A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Vivian D, Malone J. Assessment of physical aggression against women in marriage: The need for multimodal assessment. Behavioral Assessment. 1992;14:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) Public Law 104-193. Congressional Record. 1996:H7796. [Google Scholar]

- Postmus J. Battered and on welfare: The experiences of women with the Family Violence Option. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2003;31:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael J. Saving Bernice: Battered women, welfare and poverty. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Riger S, Ahrens C, Blickenstaff A. Measuring interference with employment and education reported by women with abusive partners: Preliminary data. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riger S, Staggs SL. Welfare reform, domestic violence and employment: What do we know and what do we need to know? Violence Against Women. 2004;10:961–990. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG, Holter MC, Pahl LC, Tolman RM, Kenna CE. TANF workers’ responses to battered women and the impact of brief worker training. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:227–254. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shebib B. Choices: Counseling skills for social workers and other professionals. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MD. Enhancing the quality of survey data on violence against women: A feminist approach. Gender & Society. 1994;8:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Smith JB, Earp JAL. Beyond the measurement trap: A reconstructed conceptualization and measurement of woman battering. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Taket A, et al. Routinely asking about domestic violence in health settings. British Medical Journal. 2005;327:673–676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7416.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Raphael J. A review of research on welfare and domestic violence. Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:655–682. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Rosen D. Domestic violence in the lives of women receiving welfare. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). 2nd annual report to Congress; 1999. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ofa/indexar.htm. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Gender and Women’s Health, World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M. Not going back: Sustaining the separation in the process of leaving abusive relationships. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:110–133. [Google Scholar]