Abstract

Survey research in the field of intimate partner violence is notably lacking in its attention to contextual factors. Early measures of intimate partner violence focused on simple counts of behaviors, yet attention to broader contextual factors remains limited. Contextual factors not only shape what behaviors are defined as intimate partner violence but also influence the ways women respond to victimization, the resources available to them, and the environments in which they cope with abuse. This article advances methods for reconceptualizing and operationalizing contextual factors salient to the measurement of intimate partner violence. The analytic focus of the discussion is on five dimensions of the social context: the situational context, the social construction of meaning by the survivor, cultural and historical contexts, and the context of systemic oppression. The authors consider how each dimension matters in the measurement of intimate partner violence and offer recommendations for systematically assessing these contextual factors in future research.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, contextual factors, survey research, measurement

In the past 30 years, research has documented high levels of intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization among women (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Within the field of research on IPV, scholars have used qualitative and quantitative methods to study the epidemiology of IPV and abuse-related fatalities, the pervasive economic and physical and mental health consequences of victimization for women, and the effects of differing policies for the identification and response to IPV and have developed interventions to prevent violence and its sequelae. This body of research has fostered a growing awareness that IPV plays a significant role in social processes as diverse as parent–child attachment, youth delinquency, and HIV risk prevention. For example, studies have demonstrated an association between IPV and HIV risk factors such as engaging in unprotected sex (Gilbert et al., 2000; Maman, Campbell, Sweat, & Gielen, 2000) and having a sexually transmitted illness (El-Bassel, Gilbert, Wu, Go, & Hill, 2005; Wu, El-Bassel, Witte, Gilbert, & Chang, 2003). Thus, IPV has been both a focus of research attention in determining prevalence and sequelae and one factor among many in survey research projects studying diverse social phenomena. Although incorporating IPV as a factor in survey research designs represents a step forward in our recognition of the interconnections between IPV and other social processes of interest, problems arise when the conceptualization and measurement of IPV are strictly reduced to the behavioral level (e.g., capturing only whether or not hitting or other violent behaviors occur) without awareness of the contextual factors that are important to assess in research on IPV.

A rich body of literature has evolved in the study of IPV that critiques the decontextualized, behaviorally focused measurement of IPV (for a summary of these arguments, see DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 1999). For instance, feminist researchers have objected to the lack of identification of situational context, so that behaviors such as hitting are evaluated as equivalent events, despite the fact that some hitting occurs as self-defense, whereas other hitting is used for purposes of control and coercion (Dobash & Dobash, 1998; Kurz, 1993). Postmodern scholars further complicate a purely behavioral focus through their work on the social construction of meaning and how individual understanding and responses to events are shaped by social forces that both support and constrain the meaning violence has in women’s lives (McHugh, Livingston, & Ford, 2005). Critical theorists have also contributed to this critique by identifying social-structural contexts related to culture, oppression, and history that affect women’s risk of IPV victimization and the outcomes associated with its occurrence. As an example, Crenshaw (1995) noted that women of color have a qualitatively different experience of battering than do White women, in part because women of color are more likely to be struggling with issues of poverty and racial discrimination. Each of these theoretical perspectives shares a common concern for considering women’s experience of IPV in a larger ecological context, meaning the social influences surrounding any particular event. Despite the emergence of these rich theoretical frames for conceptualizing context in IPV research, the operationalization and measurement of context are rarely holistically or systematically considered in survey research.

There are multiple dimensions to the conceptualization of IPV, including behaviors such as hitting, power dynamics in the relationship, intent of the behavior, consequences (e.g., those relating to health and everyday functioning), perceptions of normativeness of violence in women’s lives, and severity. Various qualitative studies have shown the importance of understanding contextual factors related to IPV (e.g., Beth Richie’s [1996] study of gender entrapment among African American women). Here, however, our explicit focus is on improving the quality of survey research that is done both within the field and by other researchers who are relatively unfamiliar with the arguments about the conceptualization of IPV. To inform survey research, whether IPV is the key construct or a variable of secondary interest, an expanded research paradigm that defines the construct of IPV as encompassing measures of behavior and situational or relational and social-cultural contexts is needed.

We begin with an assumption that behavioral measures (e.g., throwing something, hitting someone or using a weapon) are essential to the valid (or accurate) measurement of IPV. We consider as valid an instrument that measures all dimensions of the concept. According to Royce (2004), instruments have content validity when they “contain a representative sampling of the universe of behaviors, attitudes, or characteristics that are believed to be associated with the concept” (p. 129). However, the validity of behavioral measures of IPV needs to be strengthened by more systematically assessing other contextual factors. Just knowing that one partner has hit another does not necessarily mean that IPV has occurred. If IPV is conceptualized as encompassing (a) a pattern of behaviors that (b) yields adverse effects perceived by the victim (e.g., injury, harm, fear, intimidation, etc.) and that is (c) motivated by the perpetrator’s need for power, then measuring the physical act alone is insufficient to accurately measuring the construct. The context surrounding behaviors associated with IPV matters from a theoretical basis for a number of reasons. As we note later, prevalence rates for IPV change when contextual measures are used. In addition, context has been implicated as a cause for the variation in responses of battered women to the violence they experience (Dutton, 1996), it is fundamental to understanding the motivation for violence (Kimmel, 2002), and the social significance of IPV, such as the response of others such as the police, is often dependent on its social contexts (Crenshaw, 1995; Yoshihama, 2001).

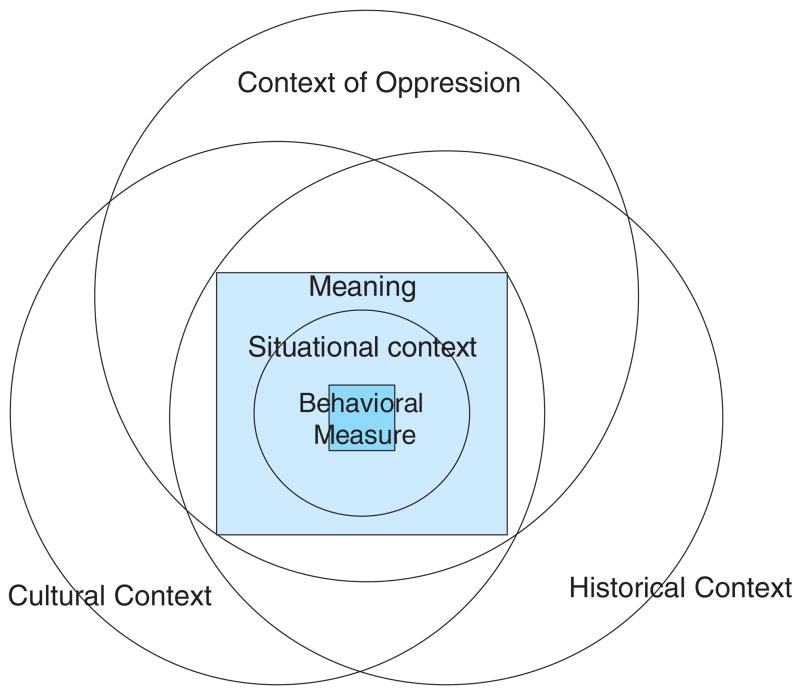

In this article, we review the theoretical and empirical literature to argue for the systematic assessment of five contextual dimensions that have the potential to lead to more valid understandings of the nature, dynamics, meaning, and consequences of IPV (see Figure 1). These dimensions are the situational or relational context, the individualized social construction of meaning, the cultural and historical contexts, and the context of oppression. We believe that all IPV-related research needs to consider each of these contextual dimensions, and all should be operationalized when IPV is the primary focus of study (i.e., the prevalence, consequences, etc.). When IPV is a factor among others being included in a survey, then the three shaded areas should be measured and interpreted within a framework that includes the larger contextual dimensions related to culture, history, and oppression. Below, we expand on each dimension and its relevance to the conceptualization of IPV, offer examples of items to strengthen the assessment of contextual factors in the measurement of IPV in survey research, and briefly discuss pragmatic issues involved in taking this approach.

Figure 1.

Holistic Model of Context Domains Relevant to Intimate Partner Violence Research

The Situational Context: Acts, Motivation, and Adverse Effects

We argue that to accurately measure IPV, it is necessary to assess not only whether given acts occurred but also the extent of any adverse effects and the motivations surrounding the behaviors. Below, we offer examples of survey instruments and items to enhance the assessment of these dimensions of the situational context.

Survey researchers have at their disposal a wide array of instruments to operationalize behavioral acts of IPV. Although many studies of IPV solely focus on physical or sexual violence between intimate partners, researchers are increasingly attempting to measure a more comprehensive range of injurious acts (DeKeseredy, 2000). Instruments have been developed to measure a broad range of behaviors, including physical violence, sexual victimization, psychological or emotional abuse, and stalking. Instruments such as the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) (Hegarty, Sheehan, & Schonfeld, 1999) assess a comprehensive range of acts, including physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking victimization. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) measures physical and psychological assault and sexual coercion. The Women’s Experiences with Battering instrument focuses on assessing psychological or emotional victimization. The National Violence Against Women Survey includes sub-scales to measure sexual victimization and stalking behaviors (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1999). The National Crime Victims Survey (NCVS) has been used for three decades by the U.S. Department of Justice to assess violent crime victimization, including violence between intimate partners (for a compendium of IPV assessment tools, see Thompson, Basile, Hertz, & Sitterle, 2006). DeKeseredy’s (2000) review of IPV research indicated that broader definitions yield larger and more accurate prevalence rates compared to narrower, legalistic definitions.

The assessment of motivation for violence may be achieved in different ways. Some instruments, such as the Safe Dates Scale (Foshee et al., 1998), include a lead-in statement that asks respondents to report only on experienced violence that was not done in self-defense. Fergusson, Horwood, and Ridder (2005) supplemented their assessment of IPV (using a modified version of the CTS-2) with questions related to who initiated the assault and whether an assault was in self-defense to distinguish between aggressive and defensive behaviors. They also included questions to assess the degree of fearfulness a partner experienced in response to violence (needing to hide from partner for fear of being seriously harmed, being seriously afraid of partner and the partner’s tendency to violence, and feeling seriously threatened or intimidated by partner). DeKeseredy and Schwartz (1999) also created items that evaluate motives for violent acts and who was the primary aggressor in the relationship overall (i.e., beyond just “who threw the first punch” in a particular fight). For example, one item asks about the extent to which respondents were “primarily motivated by acting in self-defense” (see Table 1 for a listing of these and other example items measuring relevant aspects of situational and other contexts). The relational context and history of power dynamics between intimate partners may be captured through items such as those found in the CAS (Hegarty et al., 1999). In addition to measuring the frequency of given acts of victimization, the CAS asks respondents whether they (a) are currently afraid of their partner and (b) have ever been afraid of any partner.

Table 1.

Examples of Items and Measures that Operationalize Aspects of Context

| Context Domain | Author | Construct and Example of Item or Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Situational | DeKeseredy and Schwartz (1999) | Primary aggressor, self-defense

“On [the following] items, what percentage of these times overall do you estimate that … you were primarily motivated by acting in self-defense, that is, protecting yourself from immediate physical harm?” or “What percentage of these times overall do you estimate that you used these actions on your dating partners before they actually attacked you or threatened to attack you?” (p. 4). |

| Fergusson, Horwood, and Ridder (2005) | Fear and intimidation

Questions related to “needing to hide from partner for fear of being seriously harmed, being seriously afraid of partner and their tendency to violence, and feeling seriously threatened or intimidated by partner” (p. 1106). |

|

| Rodenburg and Fantuzzo (1993) Measure of wife abuse | Injury, harm

“Please circle one answer for how hurt or upset you were by each action: 1) This never hurt or upset me; 2) This rarely hurt or upset me; 3) This sometimes hurt or upset me; 4) This often hurt or upset me.” |

|

|

Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, and Sugarman (1996)

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale Injury subscale |

Physical injury

“Was cut or bleeding; went to doctor; needed to see doctor but didn’t; felt pain the next day; had sprain or bruise could see; private parts were bleeding.” |

|

| Construction of meaning | Yoshihama (2001) | Perceived severity of abuse

Ask the respondent to rate her experience of the abusiveness of the partner’s behavior on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from1 (not at all abusive) to 4 (very abusive) (p. 311). |

| Hamby and Gray-Little (2000) | Personal meaning, self-identity

“Do you believe this event to be an instance of abuse?” “Do you think of yourself as a victim of violence?” “Do you think of yourself as a battered woman?” |

|

| Cultural context | For example, Choi and Harachi (2002) and Suinn, Rickard-Figueroa, Lew, and Vigil (1987) | Acculturation

Items measure preferences in the domains of language, food, music, movies, and association, such as: “If you could pick, whom would you prefer to associate with in the community?” Response options: 1 = almost exclusively Asians or Asian Americans, 2 = mostly Asians or Asian Americans, 3 = about equal Asian and non-Asian groups, 4 = mostly non-Asian ethnic groups, and 5 = almost exclusively non-Asian ethnic groups. or “Do you speak”: 1 = only (Vietnamese/Khmer) language, 2 = (Vietnamese/Khmer) language better than English, 3 = both(Vietnamese/Khmer) and English equally well, 4 = English better than (Vietnamese/Khmer), and 5 = only English. |

| For example, see Yoshihama (2001) | Culturally defined intimate partner violence (IPV)

Identify and measure culturally specific behaviors associated with IPV |

|

| Oppression | Atkinson, Greenstein, and Lang (2005) | Gender inequality

Example questions on gender traditionalism from the National Survey of Families and Households. Respondents were asked how much they approved of “mothers who work full-time when their youngest child is under age five.” Respondents were asked how much they agreed with statements such as “If a husband and wife both work full-time, they should share housework tasks equally” (p. 1141). |

| Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams (1999) | Day-to-day perceived discrimination From the Midlife Development in the US survey. “In your day-to-day life, how often are you treated with less courtesy than other people because you are (fill in race or other identity grouping)?”

“Do you receive poorer service than other people at restaurants and stores because you are _____” “Do people act as if they think you are dishonest because you are _____” “Are you threatened or harassed because you are _____” “Are you called names or insulted because you are _____” |

|

| Historical context | Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, and Chen (2004) | Historical trauma, historical loss

Loss of our family ties because of boarding schools. Loss of families from the reservation to government relocation. Loss of self-respect from poor treatment by government officials. Loss of trust in Whites from broken treaties. Loss of respect from our children and grandchildren for elders. Loss of our people through early death. |

Survey researchers have also developed various instruments to assess the adverse effects associated with IPV. For instance, the NCVS routinely assesses the extent of crime victimization and its consequences by measuring the victim’s injuries, medical care sought, other help-seeking activities, and the victim’s reasons for not reporting the incident to police. The Measure of Wife Abuse Scale (Rodenburg & Fantuzzo, 1993) asks respondents to indicate the number of times each act occurred (in the past 6 months) and also to report how hurt or upset they were by each action. The creators of the CTS recognized limitations of the original scale and revised it to measure the extent of physical injuries sustained (Straus et al., 1996). Straus et al. (1996) suggested further augmenting the CTS-2 with measures of power dynamics and victim perceptions of fear. The CTS-2 Physical Injury subscale includes items such as whether the respondent were “cut or bleeding, went to a doctors, or needed to see a doctor but didn’t.” Molidor, Tolman, and Kober (2000) adapted the CTS to measure heterosexual dating violence, supplementing the scale with items related to the situational context. Specifically, respondents were asked about the physical effects of the worst incident of violence. In more than 90% of the incidents, boys indicated that the physically violent behavior “did not hurt at all” (56.2%) or “hurt a little” (34.3%). In contrast, only 8.7% of girls said the incident “did not hurt at all.” Nearly half of the girls reported that the incident “hurt a lot,” and 33.6% of the girls reported being bruised or needing medical attention. If adverse effects are conceptualized as being central to the construct of IPV, then the operationalization of measures of injuries and consequences is an important dimension and may help researchers interpret and contextualize research findings.

Each of these strategies can enhance the measurement of a key facet of situational or relational context; systematic measurement of IPV in context can deepen our understanding of the nature and consequences of the violence. We suggest that such contextual dimensions (and others discussed below) are critical to the conceptualization of IPV and that their operationalization is essential to the valid measurement of IPV in survey research.

Social Construction of the Meaning of Violence

Historically, behavioral measures were developed as a response to the shortcomings of criminal victimization surveys that narrowly defined violence exposure to encompass only those behaviors that met legal definitions of crimes (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 1999). Although behavioral measures have been used to identify experiences thought to be associated with IPV (e.g., having been “pushed, grabbed, or shoved”), these measures are at best rudimentary representations of complex processes related to women’s interpretations of their situations. Although some researchers may narrowly define the focus of their study as measuring whether a crime occurred or not, regardless of its significance for the victim, we urge greater attention to the context and the victim’s interpretation to better understand and interpret the social meaning of the act. Women’s decision-making processes and their responses to IPV are determined in part by the appraisals, or interpretations, they make of their situation (Lindhorst, Nurius, & Macy, 2005; Pape & Arias, 2000). As our theoretical and empirical understandings of IPV as a social construction have evolved, it has become apparent that operationalizations of IPV should include some sense of the women’s construction and interpretation of the experiences under study.

Postmodern theorists suggest that to understand the parameters of violence (what is considered violent, the inter- and intrapersonal effects of violence, the responses of “helping” organizations), one needs to understand the meaning attributed to these events, as persons from varying standpoints will interpret the same events differently (Weis, 2001). The postmodern critique proposes that meaning, including the meaning of violence to the woman experiencing it, is socially constructed, that meaning is created (consciously or not) through the interactions among people that are proscribed by the actors’ particular social locations. As a consequence, the meaning of an event cannot be taken for granted as a “truth” associated with a particular set of events—although a woman is physically hurt by her partner, she may or may not construe this to mean that she has been a victim of abuse. Postmodern theorists posit that rather than producing “truth” as an objective, independently knowable fact, the design and methods of research actually construct knowledge, and power relations determine which perspectives are privileged over others (Smith, 1987). In particular, both feminist and postmodern theorists share a focus on the importance of context as both an epistemological and methodological issue, noting that lack of attention to context “frequently supports the status quo and potentially defends oppressive conditions” (McHugh et al., 2005, p. 323).

Methodologically, this suggests the need to incorporate questions related to how women perceive violence in their relationships and its consequences. Yoshihama (2001) proposes that researchers directly inquire about the woman’s perception of the abusiveness of various acts, diverging from the usual practice in the field that equates an act as abusive if it involves some degree of physicality, regardless of the woman’s perception (see Table 1 for example questions). This methodological strategy allows a researcher to determine the relative importance of acts and the meanings that the acts evoke for victims (Waltermaurer, 2005). Another example of an effort to measure the meaning attached to violent events is the work of Hamby and Gray-Little (2000; see Table 1). These authors asked women who reported experiencing physical force in their current relationship to identify the meanings they assigned to these behaviors in terms of whether they believed (a) that it was abuse, (b) that they were a victim of violence, and (c) that they were battered. This work illustrates the gap between behaviors and their meaning in that fewer than half of the women in this study described the experience of physical force in their relationship as abuse or even as an act of violence, and only 25% defined themselves as battered women. Little research has yet been undertaken to determine how or whether the meaning women attach to violence relates to the consequences they experience. For instance, we do not yet know if women who perceive themselves as victims of violence are more, less, or equally likely than women who do not hold this perception to have negative mental health consequences from the violence. The congruence between experiencing a behavior and perceiving it as a negative event is an empirical question that can be answered only if women’s perceptions are assessed.

Directly inquiring about the perceived degree of threat or abuse involved in a particular behavior incorporates the respondent’s own sense of the meaningfulness of an event rather than relying on the researcher’s assumption that an event is a priori abusive. For example, Molidor et al. (2000) measured heterosexual adolescent dating violence using a modified version of the CTS. Survey responses indicated that 34.9% of the girls experienced some physical or sexual violence in their current or most recent dating relationship and 38.1% of the boys reported experiencing such violence. Thus, without measuring the context or meaning of the experiences for those victimized, rates of victimization appear comparable across girls and boys, with boys actually reporting higher rates than girls. However, the study also assessed the situational context (as described in our earlier section) and the meaning of the incidents by asking respondents about their reaction to the worst incident of violence. Significant gender differences were found. Boys were significantly more likely to say their reaction to the event was to “laugh” (53.8%) or “ignore it” (30.8%), viewing these events as relatively meaningless; few girls responded in that way (10.2% and 14.5%, respectively). Instead, 40.2% of girls reacted by “crying,” and 35.9% reported “fighting back.” Boys were more likely than were girls to be identified as the initiators of the violence (70.0% vs. 27.0%), with girls’ violence more likely to be in self-defense, often in response to the boys’ sexual advances. Thus, to conclude that boys and girls in the study were equally likely to be victims of IPV would be inaccurate because the experiences and their meaning were significantly different for boys and girls. In fact, assessing these contextual factors that measure perceptions of the meaning the event had (i.e., whether it was something to laugh at or something that caused intense feelings) and aspects of the situational context previously discussed (i.e., extent of injury) revealed that what many of the boys described was not IPV at all. These findings indicate that without paying attention to the meaning people ascribe to the behaviors they experience, inaccurate interpretations of these behaviors will occur.

Cultural Context

Culture is a complex construct with no single definition (Cousineau & Rondeau, 2004). Almeida and Dolan-Delvecchio (1999) suggested that “any group that arguably has a common history and heritage can be identified as a cultural entity” (p. 658). Yet the boundaries defining such social groups are sociopolitically constructed. Warrier et al. (2002) emphasized that culture is not static, defining it as “shared experiences and commonalities that evolve under changing social and political landscapes” (p. 662). The conceptualization of cultural context in IPV research matters because the distribution of “material and rhetorical resources” is contingent on how problems and cultural contexts are defined (Crenshaw, 1995). Cultural context is germane to the study of IPV in that it shapes the level of support and the social consequences victims experience (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). Of particular relevance for the conceptualization of IPV is that cultures shape community norms, traditions, values, and family patterns (Almeida & Dolan-Delvecchio, 1999). For example, Yoshioka, DiNoia, and Ullah’s (2001) study of attitudes toward wife abuse within and among four Asian American ethnic groups found differential support for victims of IPV across the different subgroups. When asked whether they believed that some women seem to ask for beatings from their husbands, fully 57% of Vietnamese Americans endorsed this belief, compared to only 6% of Korean Americans, 23% of Chinese Americans, and 25% of Cambodian Americans. More than 40% of both Vietnamese and Cambodian American respondents disagreed with the statement that wife beating is grounds for divorce, compared to 14% among Korean Americans and 11% among Chinese. These findings demonstrate considerable variability in norms and attitudes regarding IPV across different Asian American cultural contexts. Furthermore, we adopt an intersectionality framework that emphasizes multiple identity groupings that interact differentially with systems of power and oppression. Individuals have multiple “axes of identification” (Warrier et al., 2002), and victims of IPV may (and often do) identify with more than one culture.

Culture matters to the conceptualization of IPV in that it plays a role in defining what behaviors are deemed abusive and in what particular situational contexts, and it shapes the personal meaning that victims attach to their experiences. Researchers studying IPV among particular racial, ethnic, or identity groups or those intending to make comparisons among groups can benefit from preliminary studies to determine whether culturally linked forms of abuse (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005; Yoshihama, 2001) should be operationalized and which dimensions of the cultural context are relevant to measure. For example, Yoshihama (2001) reported that pilot tests with Japanese women identified unique “socioculturally rooted” forms of IPV that were then included in future measurement instruments with Japanese and Japanese American respondents. Culturally rooted forms of abuse included overturning a dining table, which “represents the locus of family activities and, by extension, is a symbol of a woman’s legitimate role and place in the Japanese home,” and a measure of sexual coercion, namely “being forced to have sex when concerned about family members or others around,” which was perceived as particularly harmful in this cultural context in which sleeping arrangements typically offer little privacy (p. 310). Importantly, Yoshihama reported that including these two socioculturally based items increased the rate of reported physical abuse by 5% and increased reported sexual abuse by 11%. As Sokoloff and Dupont (2005) noted, attention to culturally linked forms of abuse “does not mean that domestic violence is relative so much as that women must be able to voice their concerns about how violated they feel within a cultural framework that is meaningful to them” (p. 42).

Despite the relevance of cultural context to theoretical understandings of IPV, survey research in the United States on violence against women of differing racial and ethnic backgrounds rarely directly examines the cultural context including shared values or beliefs; it instead typically relies on measures of categorical membership to infer cultural differences (Kasturirangan, Krishan, & Riger, 2004). That is, rather than directly assessing cultural values or beliefs (e.g., norms regarding IPV, patriarchal beliefs, etc.), researchers often use unidimensional measures such as race to infer cultural traits. In doing so, they risk drawing conclusions that are inaccurate and may perpetuate negative perceptions of populations by wrongly attributing to race differences explained by other factors, such as socioeconomic status (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). Aggregated categories such as African American, Native American, Asian American, or Latina are, at best, superficial measures of ethnic identity and culture (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998). Even disaggregated measures of ethnicity may obscure significant within-culture differences, such as differences in social class, levels of cultural attachment, or ethnic identity. For example, among immigrants and refugees, cultural factors such as generational status of immigration may influence definitions of what constitutes IPV and may shape responses of immigrant victims (Menjivar & Salcido, 2002; Yoshihama, 2001). Indeed, Yoshihama (2001) found significant differences across generations of Japanese American immigrant women, including differences in the types of violence reported and in perceived abusiveness of the acts. Specifically, the study found that Japanese American women who were more recent immigrants (e.g., “first generation”) reported higher rates of the “socioculturally rooted” forms of IPV (e.g., overturning a table, dousing with liquid) than did Japanese American women who were born in the United States (i.e., second-, third-, or fourth-generation status). The former also tended to report these culturally linked forms of IPV as more serious than did victims who were born in the United States. Yet Yoshihama also cautions that it is incorrect to assume that immigrants’ generational status is always inversely related to their attachment to their culture of origin. Individuals who have lived in the United States longer are not necessarily more acculturated to dominant U.S. norms regarding IPV. Thus, immigrants’ generational status and their levels of acculturation or enculturation are best directly and separately measured. Furthermore, as discussed in more detail below, cultural context factors such as generational status may intersect with the context of oppression and should be viewed in historical context. In the face of limited knowledge, Yoshihama’s example points to intragroup variation in the influence of ethnic and cultural factors on survivors’ experiences and perceptions. More routine use of multidimensional measures of cultural context in IPV research, such as those items presented in Table 1, could help develop this body of knowledge.

Discussions of culture and domestic violence have become entangled to such an extent that violence against women may be ascribed as a cultural trait, with an outcome that “other” cultures (i.e., non-American, non-White) are portrayed as pathologically violent (Crenshaw, 1995). Culture should not be confused with patriarchy; as Almeida and Dolan-Delvecchio (1999) note, “Wife battering is not culture” (p. 667). As Dasgupta (1998) points out, “Every culture has tenets that disenfranchise women, as well as empower them” (p. 217). Patriarchy, or the control by men of a disproportionately large share of power and resources (Webster’s Dictionary, 1999), may be a nearly universal ideology, but its local expression will vary (Menjivar & Salcido, 2002; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). For instance, the United Nations Development Program has created the Gender Development Index and the Gender Empowerment Measure to identify variations in the degree of gender inequality as a result of patriarchal ideology in each nation (Fukuda-Parr, 2004). These measures indicate that it is possible to evaluate the level of patriarchy at national and community levels, allowing for the empirical evaluation of the amount and impact of patriarchal systems within IPV research.

Frequently, culture is viewed in terms of how it creates risk. The conflation of culture and patriarchy contributes to a focus on those cultural beliefs, traditions, and practices that place women at risk of abuse. Yet cultural practices can also prevent victimization and ameliorate its effects once it occurs. In this way, the study of cultural context may include the study of cultural narratives and coping strategies that may be sources of strength and perseverance across generations. Women draw strength from cultural practices such as kinship networks and through a culture’s values, spiritual beliefs, and practices (Kasturirangan et al., 2004). Cultural factors such as ethnic identity, ethnic pride, and attachment to one’s culture of origin may influence responses of IPV victims or may moderate the effects of IPV. Social networks offer support and serve to establish social norms that may be protective of adverse effects (Beeman, 2001). Cultures characterized by strong social connections may therefore be a source of support for victims and may also offer a foundation for effective intervention to address IPV. Community may be an immigrant woman’s “lifeline” of personal, spiritual, and economic support, yet for some women, cultural norms may dictate that leaving an abusive relationship is unacceptable, and doing so may mean social ostracism from that very community and its resources (Dasgupta, 1998).

Measuring IPV in specific cultural contexts is at an early stage of development. Although researchers have interpreted findings from IPV research from a contextual perspective, that is, they have linked discussion of results to broader ecological factors, actual measures of cultural and historical context are rare (see Table 1). Although the field heavily relies on the use of the CTS to document family violence, this measure has limited ability to identify behaviors consistent with patterns of coercive control that are defined differently in nondominant U.S. cultures (Dasgupta, 2002). Analysis that includes variables related to the cultural context may yield more accurate estimates of prevalence, uncover important relationships, and enable researchers to test hypotheses derived from theoretical approaches that emphasize context. Absent measures of cultural factors in studies of IPV, researchers miss the opportunity to examine culture as a mechanism for IPV prevention and as a source of resilience for survivors. As depicted in Figure 1, we argue that the cultural context itself is better understood in historical context and as potentially overlapping with the context of social oppression. Below, we elaborate on the interconnections between the cultural and historical contexts and the context of systemic oppression and the relevance of these domains for the measurement of IPV.

Context of Systemic Oppression

Often, issues of culture and oppression overlap to such an extent that it is difficult to disaggregate the two concepts because, particularly in the American context, cultural differences have often been associated with oppression (i.e., Jim Crow laws, immigration restrictions, etc.). Here, we view these as separate, but intersecting, constructs that should each be evaluated. Although we have previously defined culture as sharing experiences and a common history, a definition of oppression, in contrast, incorporates issues of power, domination, and the institutionalized power to harm. Prilleltensky and Gonick (1996) define oppression as

a state of asymmetric power relations characterized by domination, subordination, and resistance, where the dominating persons or groups exercise their power by restricting access to material resources and by implanting in the subordinated persons or groups fear or self-deprecating views about themselves. (pp. 129–130)

Conceptually, we differentiate the context of oppression from the historical context by focusing in this section on the assessment of current-day perceptions of various forms of oppression experienced by victims of IPV.

Viewing domestic violence as the same experience for all women conceals the systemic subjugation some women face, which fosters a deep sense of mistrust in dominant cultural systems such as the criminal justice and social service systems (Donnelly, Cook, Van Ausdale, & Foley, 2005; Kasturirangan et al., 2004). Intersectionality theory proposes that differences in social location lead to differences in experience and in interpretation of the same experiences resulting in varying patterns of risk for women (Renzetti, 1998). Therefore, violence against women must be understood in the context of the power for some generated by White supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, heterosexism, ableism, ageism, classism, and economic exploitation, as these systems of oppression exacerbate the consequences of IPV for victims (Renzetti, 1998; Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). We offer three specific examples of the intersection of oppression with cultural context to illustrate the role oppression plays in shaping the experiences of violence for women because of their poverty, immigration status, and sexual orientation.

Although domestic violence is found in all strata of society, “poor women of color are ‘most likely to be in both dangerous intimate relationships and dangerous social positions’” (Richie, 2000, p. 1136). African American, Latina, and American Indian women have increased rates of both poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003a, 2003b) and violence (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000) relative to their White counterparts. Poverty is implicated as a factor in women’s continuation of abusive relationships because economic hardship is one of the most important reasons for remaining with a violent partner (Strube & Barbour, 1983, 1984). Recent research on the interrelationship between low income status and IPV demonstrates that IPV is associated with longer use of welfare for women with children (Seefeldt & Orzol, 2005). Low-income women without children are at equally high risk of exposure to IPV as women on welfare (Lown, Schmidt, & Wiley, 2006). Complicating the picture for poor women further is the fact that agencies identified to address issues of poverty are ill equipped to respond to domestic violence among their clientele. For instance, welfare offices across the country have provided little support to domestic violence victims who are unable to meet welfare work requirements because of the abuse (Levin, 2001; Lindhorst & Padgett, 2005; Postmus, 2004). In this way, the economic context of victims’ lives and the structure of the social welfare system’s response also affect the impact of IPV and the options available to victims.

The experience of IPV for immigrant women in the United States must also be understood in the context of their immigration status and the context of oppressive anti-immigrant policies (Chang, 2000; Narayan, 1995; Shetty & Kaguyutan, 2002). Immigration status varies across and within cultural groups (Yoshihama, 2001), with significant implications for victims of IPV. For example, women with vulnerable immigration status may hesitate to disclose IPV or to leave a batterer for fear of deportation (Dasgupta, 1998) or for fear of jeopardizing their chances of gaining legal permanent resident or citizen status (Shetty & Kaguyutan, 2002). Gender oppression inherent in many immigration policies shapes the power dynamics in relationships, reinforcing inequalities and giving abusive partners additional tools for controlling and abusing their partners (Chang, 2000; Narayan, 1995). In the context of existing immigration policy, actions such as taking a victim’s passport or destroying her identification documents may be perceived by victims as serious forms of abuse (Yoshihama, 2001). As Dasgupta (1998) observed,

The chronicle of peoples’ immigration to the United States in neither benign nor fair. The policies that historically have regulated migration, especially from nations of color, were hardly based on generosity and a sense of justice. … Although INS policies have been universally prohibitive regardless of gender, women have had to bear the brunt of its inherent misogyny, racism, and xenophobia. (p. 213)

Although certain legal protections for battered immigrant women have been achieved, policies leave many women vulnerable. For example, federal welfare reform policy (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity and Reconciliation Act of 1996) targeted immigrant groups for cuts in social assistance, leaving immigrant women fewer options for economic self-sufficiency. Policies regarding child custody may leave immigrant victims of IPV in fear of losing their children should they seek to end an abusive relationship (Dasgupta, 1998; Shettty & Kaguyutan, 2002).

Our third example draws on the experiences of lesbian and bisexual women who experience abuse from other women. The struggle for validation of the relationships of lesbian and bisexual women in the United States has a long historical context, in which sodomy laws have been used to criminalize lesbian, gay, and bisexual relationships (Barret & Logan, 2002). Currently, only Massachusetts legally recognizes lesbian marriages, and, in fact, several jurisdictions have passed laws prohibiting legal recognition of gay and lesbian relationships (Rosenberg & Breslau, 2005). As members of a stigmatized group, lesbian and bisexual women must cope with the social context of oppression that is manifested through institutionalized discrimination, personal prejudice encountered within families, and stresses unique to sexual minorities, such as those surrounding the coming-out process or decisions to conceal one’s identity (Balsam, 2003; Balsam & Szymanksi, 2005). Abusive partners within lesbian or bisexual relationships also employ tactics that rely on heterosexism to enforce control, such as threatening to disclose their partner’s sexual orientation to employers or family members when this information could have severe negative consequences (Renzetti, 1998). Women who experience IPV in a lesbian or bisexual relationship often encounter heteronormative assumptions about violence from legal and domestic violence service providers, affecting access to and the quality of help they can receive (Ristock, 1994). Although many lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered women share similar experiences related to the effects of living in a heterosexist society, these consequences are further shaped by other systems of oppression. Without understanding the contextual factors surrounding violence experienced by lesbian or bisexual women, researchers may not be able to identify key dimensions of the abuse or factors associated with the consequences of the violence.

As our theoretical understanding of oppression has increased in the past decades, so too has our ability to measure aspects of oppression at the individual level. We next offer two examples of survey research that is incorporating measurement of gender oppression and perceived discrimination based on race/ethnicity.

One method for assessing gender oppression has been developed by the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) and applied to IPV research (Atkinson, Greenstein, & Lang, 2005). The NSFH has developed an index that measures aspects of gender inequality that are embedded in traditional views related to women’s work, care of children, and division of household tasks (see Table 1 for examples). Using this measure of traditionalism, the authors were able to demonstrate that husbands with higher levels of traditionalism and lower relative earnings had higher predicted probabilities of abusing their wives than did men who held more egalitarian views about appropriate roles for women.

Feminist research by women of color has demonstrated that gender is but one aspect of oppression experienced by some women (Kanuha, 1994). Gender oppression differs depending on its co-occurrence within other systems of power and oppression based on race, class, sexuality, age, and disability (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). The impact of these inequalities may be considered in survey research by inclusion of measures of perceived “microaggressions,” or the daily hassles associated with oppressive structures, such as racism, sexism, classism, or heterosexism. For instance, national epidemiological surveys on mental health (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999) have incorporated measures of perceived day-to-day discrimination that can be used to measure microaggressions related to race, ethnicity, sexual or gender orientation, age, disability, or other identity grouping (see Table 1 for example questions). Various researchers are also working on group-specific indices measuring aspects of oppression, such as the African American Adolescent Respect Scale, which incorporates measures of perception of social value and interactions with social institutions (Leary, Brennan, & Briggs, 2005). These scales show that measures that are sensitive to the experiences of oppression and that can differentiate these experiences among respondents are available.

Historical Context

To assess IPV without understanding the historical context within which each person’s identity and interpretation of events is formed is to obscure historical institutionalized inequities. Historical context may be particularly relevant to understanding patterns of and responses to IPV among groups that have been historically marginalized or oppressed. While recognizing that not all who are exposed to historical trauma and oppression will be adversely affected, below we argue the salience of historical context and offer examples of measures that enhance assessment of historical factors.

Earlier, we offered the example of generational status as a factor of relevance in the measurement of the cultural context of immigrants and refugees. Of importance, measurement of a cultural context factor such as generational status should be considered in historical context. For instance, Vietnamese immigrants and refugees first arrived in the United States in 1975, as U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War drew to a close (Nguyen, Messe, & Stollak, 1999). This first wave of refugees from Vietnam was highly educated, was often politically connected, and usually migrated as intact families (Rice, 1996). These families received a fairly supportive social reception in the United States and have been relatively economically secure. However, around 1978, a second wave of Vietnamese refugees began arriving in the United States after surviving oftentimes traumatic escapes from their war-ravaged country. These individuals were less educated, were often ethnic minority Vietnamese, and had limited resources (Lee, 1990). The latter group remains considerably more economically vulnerable. Thus, among Vietnamese refugees and immigrants, a measure of generational status alone would not adequately capture the variation in individuals’ migration experience, an experience that may have implications for IPV patterns and effects. Surveys involving Vietnamese participants should therefore measure the historical time period of the migration experience, as was done in the recent Cross Cultural Families Study, a longitudinal study involving Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant and refugee families in the United States (Choi & Harachi, 2002).

The growing literature on the intergenerational transmission of historical trauma (e.g., Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Evans-Campbell, 2008 [this issue]; Leary, 2005; Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004) demonstrates that traumatic experiences of prior generations may exert ongoing influences on later generations. Describing the conceptualization of historical trauma among Native Americans, Whitbeck et al. (2004) pointed to a historical context marked by genocidal federal policy, systematic ethnic cleansing efforts, and policies of forced assimilation that spanned generations. Of importance, they observe that

American Indian people are faced with daily reminders of loss: reservation living, encroachment of Europeans on even their reservation lands, loss of language, loss and confusion regarding traditional religious practices, loss of traditional family systems, and loss of traditional healing practices. We believe that these daily reminders of ethnic cleansing coupled with persistent discrimination are the keys to understanding historical trauma among American Indian people. The losses are not “historical” in the sense that they are in the past and a new life has begun in a new land. Rather, the losses are ever present, represented by the economic conditions of reservation life, discrimination, and a sense of cultural loss. (p. 121)

Whitbeck et al. used a measure of historical trauma that measures an individual’s perception of the emotional impact of various losses, such as the “loss of our family ties because of boarding schools” and “the loss of respect from our children and grandchildren for elders” (see Table 1). The study found substantial prevalence rates of historical trauma and grief among younger generations of Native Americans, showing that awareness of loss was not unique to elders. Furthermore, their findings demonstrated that perceptions of historical losses were significantly related to emotional distress in their sample. Measures of historical trauma or loss in studies involving historically oppressed populations such as Native Americans and African Americans can deepen our understanding of whether and how historical trauma compounds the effects of IPV on victims. Including measures of historical trauma among IPV perpetrators also offers the opportunity to empirically examine its role in the etiology of violence in the home.

Summary of Recommendations for Conceptualizing Context in IPV Survey Research

As can be seen from the previous discussion, IPV is conceptualized as multidimensional, with factors representing multiple, intersecting contexts, and our measurement of this experience should be similarly multidimensional. The need for greater complexity in this research is not without cost, and the constraints of survey research, including interviewing costs, recruitment challenges, respondent fatigue, participant attrition, and translation costs, impose limits on what information can be obtained in surveys. However, if researchers are aware of aspects of context that they are not including in their research studies, they will also be more informed about the limitations of their own data and the conclusions that can be drawn from it. As our theoretical understanding of IPV grows, additional contexts such as those related to age or generational cohort (Moon, 2000) may need to be included in the operationalization of context.

As we note in Figure 1, although behavioral measurement of physical acts is an important element in the conceptualization of IPV, measurement of situational or relational, cultural, and historical contexts, the context of oppression, and how the acts are socially constructed by survivors is also critical in developing a more valid assessment of IPV and its consequences. Below, we summarize the specific strategies we have suggested for sharpening the contextualized conceptualization and operationalization of IPV in survey research:

Assess the situational context, specifically the motivations for (e.g., self-defense, control, coercion) and adverse effects of (injury, emotional impact, responses) violence and relationship power dynamics (history of power and control, history of battering).

Incorporate questions that directly measure women’s perceptions of the degree of abusiveness of each act (perceived severity, perceived impact).

Identify culturally specific acts that are considered abusive to women within the culture under study (e.g., via consultation, focus groups, or pretesting).

Separate patriarchy from culture; directly measure levels of gender oppression.

Identify relevant aspects of culture for each group or subgroup and assess these, including (but not limited to) acculturation or enculturation, ethnic identity, attachment to culture, migration experiences, generational status, and cultural beliefs, norms, attitudes, and traditions.

Assess experiences of institutionalized oppression such as daily hassles or microaggressions and discriminatory treatment.

Assess experiences of factors such as poverty or classism, heterosexism, ageism, and ableism.

Assess historical trauma and losses.

Conclusion

In this article, we have called attention to the benefits of broadening the contextual operationalization of IPV in survey research. We urge researchers to utilize their expertise regarding participant populations to formulate measures that capture these key dimensions of situation, culture, oppression, historical context, and socially constructed meaning. To accomplish the goal of understanding the rich contexts of women’s lived experiences, we have to release the comfort of a “one-size-fits-all” definition of domestic violence. Some argue that quantitative methods will never do justice to the complexity of IPV (DeKeseredy, & Schwartz, 1999). Although we acknowledge limitations of quantitative measures of IPV, we have argued that they may be designed to more effectively foreground contextual factors. We believe that by adopting a more complex conceptualization and operationalization of IPV in survey research, we will reap the benefits in increased validity, closer alignment with theory, and the opportunity to test explanations for the patterns we observe.

Biographies

Taryn Lindhorst, PhD, LCSW, is an associate professor of social work at the University of Washington. Her work is informed by 16 years of social work practice experience. Her research focuses on the intersections between individuals and social institutions, particularly as this relates to issues of violence and poverty for women. Her work on the effects of welfare reform for battered women has won two national awards, and her research has been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Justice. Her current projects include a longitudinal analysis of the long-term impact of domestic violence on economic and mental health outcomes among adolescent mothers, and a qualitative study with battered women who have been prosecuted for child abduction under the international Hague Convention treaty.

Emiko Tajima is associate professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work, where she teaches social welfare policy, child and family policy and services, domestic violence intervention, and research methods. Her scholarly research focuses on the impact of domestic violence on children, parenting practices, immigrant and refugee populations, and methodological issues in the field of interpersonal violence research.

References

- Almeida RV, Dolan-Delvecchio K. Addressing culture in batterers intervention: The Asian Indian community as an illustrative example. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:654–683. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson MP, Greenstein TN, Lang MM. For women, breadwinning can be dangerous: Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF. Traumatic victimization in the lives of lesbian and bisexual women: A contextual approach. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7:1–14. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Szymanksi DM. Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Barret B, Logan C. Counseling gay men and lesbians. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beeman SK. Critical issues in research on social networks and social supports of children exposed to domestic violence. In: Graham-Bermann SA, Edleson JL, editors. Domestic violence in the lives of children: The future of research, intervention, and social policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MY, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8:60–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Coronado N, Watson J. Conceptual, methodological and statistical issues in culturally competent research. In: Hernandez M, Isaacs R, editors. Promoting cultural competence in children’s mental health services. Baltimore: Brookes; 1998. pp. 305–331. [Google Scholar]

- Chang G. Disposable domestics: Immigrant women workers in the global economy. Boston: South End; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Harachi TW. The cross cultural equivalence of the Suinn-Lew Asia Self-Identity Scale with Vietnamese and Cambodian Americans. Journal of Social Work Research. 2002;3:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau M, Rondeau G. Toward a transnational and cross-cultural analysis of family violence. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:935–949. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In: Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K, editors. Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New York: New Press; 1995. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. Women’s realities: Defining violence against women by immigration, race, and class. In: Bergen RK, editor. Issues in intimate violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. A framework for understanding women’s use of nonlethal violence in intimate heterosexual relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1364–1389. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy WS. Current controversies on defining nonlethal violence against women in intimate heterosexual relationships. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:728–746. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy WS, Schwartz MD. Measuring the extent of woman abuse in intimate heterosexual relationships: A critique of the Conflict Tactics Scales. 1999 Retrieved December 2, 2005, from http://www.vawnet.org/DomesticViolence/Research/VAWnetDocs/AR_ctscrit.pdf.

- Dobash RE, Dobash RP, editors. Rethinking violence against women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DA, Cook K, Van Ausdale D, Foley L. White privilege, color blindness and services to battered women. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:6–37. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA. Battered women’s strategic response to violence: The role of context. In: Edleson JL, Eisikovits ZC, editors. Future interventions with battered women and their families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. HIV and intimate partner violence among methadone-maintained women in New York City. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native American communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood JL, Ridder EM. Partner violence and mental health outcomes in a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1103–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence program. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:45–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda-Parr S. Human development report 2004. 2004 Available from United Nations Development Programme Web site, http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2004/pdf/hdr04_HDI.pdf.

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Rajah V, Foleno A, Fontdevila J, Frye V, et al. The converging epidemics of mood-altering drug use, HIV, HCV, and partner violence: A conundrum for methadone maintenance treatment. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2000;67:452–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL, Gray-Little B. Labeling partner violence: When do victims differentiate among acts? Violence and Victims. 2000;15(2):173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kanuha V. Women of color in battering relationships. In: Comas-Diaz L, Greene B, editors. Women of color: Integrating ethnic and gender identities in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford; 1994. pp. 428–454. [Google Scholar]

- Kasturirangan A, Krishan S, Riger S. The impact of culture and minority status on women’s experience of domestic violence. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2004;5:318–332. doi: 10.1177/1524838004269487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS. “Gender symmetry” in domestic violence: A substantive and methodological review. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1332–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz D. Physical assaults by husbands: A major social problem. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DR, editors. Current controversies on family violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Leary JD. Post-traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Milwaukie, OR: Uptone Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leary JD, Brennan EM, Briggs HE. The African American Adolescent Respect Scale: A measure of a prosocial attitude. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15(6):462–469. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. Family therapy with Southeast Asian families. In: Mirkin MP, editor. The social and political contexts of family therapy. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1990. pp. 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- Levin R. Less than ideal: The reality of implementing a welfare-to-work program for domestic violence victims and survivors in collaboration with the TANF department. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Nurius P, Macy R. Contextualized assessment with battered women: Strategic safety planning to cope with multiple harms. Journal of Social Work Education. 2005;4:371–393. doi: 10.5175/jswe.2005.200200261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Padgett J. Disjunctures for women and frontline workers: Implementation of the family violence option. Social Service Review. 2005;79(3):405–429. doi: 10.1086/430891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown AE, Schmidt LA, Wiley J. Interpersonal violence among women seeking welfare: Unraveling lives. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1409–1415. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh MC, Livingston NA, Ford A. A postmodern approach to women’s use of violence: Developing multiple and complex conceptualizations. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar C, Salcido O. Immigrant women and domestic violence: Common experiences in different countries. Gender & Society. 2002;16:898–920. [Google Scholar]

- Molidor C, Tolman RM, Kober J. Gender and contextual factors in adolescent dating violence. Prevention Researcher. 2000;7(1):1–4. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon A. Perceptions of elder abuse among various cultural groups: Similarities and differences. Generations. 2000;24:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan U. “Male-order” brides: Immigrant women, domestic violence and immigration law. Hypatia. 1995;10(1):104–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Messe LA, Stollak GE. Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment: Cultural involvements and psychosocial functioning in Vietnamese youth. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999;30:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pape KT, Arias I. The role of perceptions and attributions in battered women’s intensions to permanently end their violent relationships. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL. Battered and on welfare: The experiences of women with the family violence option. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2004;31:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I, Gonick L. Polities change, oppression remains: On the psychology and politics of oppression. Political Psychology. 1996;17:127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Renzetti CM. Violence and abuse in lesbian relationships: Theoretical and empirical issues. In: Bergen RK, editor. Issues in intimate violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rice FP. The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture. 8. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Richie BE. Compelled to crime: The gender entrapment of battered Black women. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Richie B. A Black feminist reflection on the antiviolence movement. Signs. 2000;25:1133–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Ristock JL. “And justice for all?” … The social context of legal responses to abuse in lesbian relationships. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law. 1994;7:415–430. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg FA, Fantuzzo JW. The measure of wife abuse: Steps toward the development of a comprehensive assessment technique. Journal of Family Violence. 1993;8:203–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg D, Breslau K. Culture wars: Wining the “values” vote. Newsweek. 2005 Retrieved December 7, 2005, from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6401635/site/newsweek/

- Royce D. Research methods in social work. 4. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Thomson Brooks-Cole; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt KS, Orzol SM. Watching the clock tick: Factors associated with TANF accumulation. Social Work Research. 2005;29:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S, Kaguyutan J. Immigrant victims of domestic violence: Cultural challenges and available legal protections. 2002 Available from Violence Against Women Online Resources Web site, http://www.vaw.umn.edu.

- Smith DE. The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff NJ, Dupont I. Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: Challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:38–64. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK. Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. Garden City, NY: Anchor/Doubleday; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Strube MJ, Barbour LS. The decision to leave an abusive relationship: Economic dependence and psychological commitment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Strube MJ, Barbour LS. Factors related to the decision to leave an abusive relationship. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46:837–844. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: An initial report. Educational & Psychological Measurement. 1987;47:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Basile KC, Hertz MF, Sitterle D. CDC measuring intimate partner victimization and perpetration: A compendium of assessment tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NCJ 169592) Washington, DC: Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NCJ 181867) Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey (CPS)—Definitions and explanations. 2003a Retrieved December 2, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/cps/cpsdef.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty in the United States: 2002. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Waltermaurer E. Measuring intimate partner violence (IPV): You may only get what you ask for. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:501–506. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrier S, Williams-Wilkins B, Pitt E, Reece RM, Groves BM, Lieberman AF, et al. Culturally competent responses and children: Hidden victims: Excerpts from Day 2 Plenary Sessions. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:661–686. [Google Scholar]

- Webster’s dictionary. Classic. New York: Random House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weis L. Race, gender and critique: African-American women, White women and domestic violence in the 1980s and 1990s. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2001;27:139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian People. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Chang M. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk among urban minority women in primary health care settings. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:291–301. doi: 10.1023/a:1025447820399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M. Immigrants-in-context framework: Understanding the interactive influence of socio-cultural contexts. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2001;24:307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka MR, DiNoia J, Ullah K. Attitudes toward marital violence: An examination of four Asian communities. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:900–926. [Google Scholar]