Abstract

The use of antiangiogenic agents represents a promising strategy for the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Objective responses to single-agent thalidomide have been described, and a randomized study showed that bevacizumab (a neutralizing antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor) delayed time to progression of metastatic renal cancer. A pilot study combining these two agents was performed. Sequential cohorts of 10 and 12 patients (crossing over from placebo therapy in the aforementioned randomized bevacizuamab trial) were treated with low-dose bevacizumab alone or bevacizumab plus the maximum tolerated dose of thalidomide as determined by intrapatient escalation. Toxicity, objective responses, and time to progression were the endpoints of this study. Patients tolerated thalidomide and bevacizumab well, with more than 50% of patients escalating to at least 500 mg/d thalidomide. Grades 1 and 2 sensory neuropathy limited thalidomide dose escalation in 3 of 12 patients. The incidence of grades 3 and 4 toxicity was not different between patients treated with bevacizumab alone versus bevacizumab plus thalidomide. There were no objective responses and no difference in progression-free survival between the groups (2.4 months for bevacizumab alone, 3.0 months for bevacizumab plus thalidomide). Combination antiangiogenic therapy with bevacizumab plus thalidomide in patients with renal cell carcinoma is associated with similar toxicity and progression-free survival compared with bevacizumab alone. This study illustrates a clinical trial design for rapidly testing the feasibility and safety of combining antiangiogenic agents, an approach that will be necessary for rapidly evaluating the many potential combinations of antiangiogenic agents.

Keywords: angiogenesis, renal cancer, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), bevacizumab, thalidomide

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has an annual incidence of almost 32,000 cases in the United States and is responsible for approximately 12,000 deaths per year.1 Approximately 30% of patients present with metastatic disease, and once metastatic disease is diagnosed, the 5-year survival rate is poor.2–4 Systemic options for the treatment of metastatic disease are limited as RCC is refractory to chemotherapeutic and hormonal agents. Biologic agents such as intereukin-2 or interferon-alpha have been used, with objective response rates of approximately 16% for each5,6 but with durable complete responses of about 9% achieved only with interleukin-2.7

The use of antiangiogenic agents represents a promising strategy for the treatment of RCC, given the genetic mechanisms underlying this disorder. Both hereditary clear cell RCC (associated with von Hippel Lindau [VHL] syndrome) and most cases of sporadic clear cell RCC are associated with mutations in the VHL gene, leading to overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)8 and increased angiogenesis. Our group has recently completed a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, for the treatment of patients with metastatic RCC, which demonstrated a significant prolongation of time to progression in patients receiving 10 mg/kg bevacizumab every 2 weeks compared with placebo, but few objective responses were seen.9 Eventual tumor escape from VEGF blockade occurred in most patients and could be due in part to alternative proangiogenic pathways used by RCC, or insufficient blockade of VEGF by bevacizumab. Adding other agents with antiangiogenic potential to bevacizumab represents an attractive approach for improving therapy.

Thalidomide is an antiangiogenic agent that in experimental models has been shown to significantly decrease both basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)- and VEGF-induced corneal neovascularization.10,11 In the clinical setting thalidomide has been shown to have utility in the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma, a plasma cell disorder characterized by prominent neovascularization of the bone marrow,12 and has likewise demonstrated sporadic activity in the treatment of patients with RCC. A pilot study by Amato13 first reported the achievement of a partial response to thalidomide in a patient with metastatic RCC to the lungs and liver. Several phase 2 studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of single-agent thalidomide for the treatment of RCC; partial response rates range from 0% to 17%, with stabilization of disease for greater than 3 to 6 months occurring in 12.5% to 64% of patients.14–17 Still, there are no randomized clinical studies of thalidomide showing inhibition of growth of RCC.

Based on these data, data from a previous phase 1 clinical trial of bevacizumab,18 and the extensive toxicity data available for thalidomide, thalidomide was added to low-dose bevacizumab in the crossover arm of our phase 2 trial comparing bevacizumab to placebo to rapidly assess the activity and toxicity of this combination of agents. A cohort of patients was crossed from placebo to low-dose bevacizumab alone prior to treating a second cohort with both agents, and the outcomes of these groups are compared.

Materials and Methods

Patients with histologically confirmed clear cell RCC who had tumor progression on placebo were eligible for entry into this study. Other inclusion/exclusion criteria are detailed in the original phase 2 trial.9 This phase 2 trial enrolled a total of 116 patients: 39 patients were randomly assigned to receive high-dose bevacizumab (10 mg/kg), 37 patients to low-dose bevacizumab (3 mg/kg), and 40 patients to placebo. Twenty-two of the 40 patients who had been randomized to placebo were treated on a crossover arm. These 22 patients are the subjects of this study; 10 patients were treated with low-dose bevacizumab alone and a subsequent 12 patients were treated with low-dose bevacizumab in combination with thalidomide. Accrual to this pilot trial was terminated when the randomized phase 2 comparison of bevacizumab versus placebo was terminated for reaching criteria for early stopping.9

Bevacizumab was provided by Genentech Incorporated and thalidomide was supplied by the NIH Clinical Center Pharmacy. Bevacizumab was administered intravenously over 2 hours starting with a loading dose of 4.5 mg/kg, followed by a treatment dose of 3 mg/kg 1 week later and every 2 weeks thereafter. The starting daily dose of thalidomide was 200 mg orally beginning on the day of bevacizumab loading, followed by escalation in 100-mg increments every 2 weeks to a maximum of 800 mg per day. Dose escalation was stopped for the development of neurologic toxicity. Patients who developed grade 1 neuropathy continued treatment with thalidomide at their current dose level with no further escalation. Thalidomide treatment was held for grade 2 or higher neuropathy; if symptoms resolved, thalidomide was restarted at two dose levels below the level that caused the toxicity. Patients were evaluated 5 weeks after beginning treatment and every 8 weeks thereafter. Evaluation consisted of laboratory testing; computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; magnetic resonance imaging of the brain; physical examination; and assessment of toxicity. Treatment continued until evidence of disease progression or grade 3 or 4 toxicity was encountered.

Standard response criteria were used. Partial responses were defined as a decrease of at least 50% in the sum of the products of maximal perpendicular diameters of metastatic lesions lasting a minimum of 1 month with no progression of any lesion or appearance of new lesions, and complete responses were defined as the resolution of all disease for at least 1 month. Disease progression was defined as the appearance of any new lesion measuring at least 1.5 cm and/or an increase in the product of maximal perpendicular diameters of any measurable lesion by at least 25% compared with baseline, or a tumor-related deterioration in performance status to at least 3 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale. All tumor measurements were performed by an investigator unaware of which crossover cohort patients were treated in.

Time to progression was calculated from the first day of crossover treatment to the date of disease progression. Progression-free survival was analyzed via the Kaplan-Meier method and curves were compared using the log-rank test, with two-tailed P values.

Assessments of total tumor burden were derived from the sum of the products of maximal perpendicular diameters of lesions measured at each follow-up time and were expressed as a percentage of the sum of the products of baseline measurements. Changes in total tumor burden were statistically compared relative to baseline only at 5 weeks and 13 weeks, prior to enrollment declines due to tumor progression. Changes in tumor burden were also compared with similar assessments performed on patients treated in the randomized phase 2 study of bevacizumab versus placebo. Comparisons were made between groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Changes in burden while on crossover therapy were also compared with changes in burden in the same subjects while they were on placebo by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. This study was intended to be exploratory. In cases for which a clear lack of significant differences was found, this would suggest that it is unlikely that a difference would be found in a study with adequate power to rigorously address the issues discussed in this paper. All P values are two-tailed.

Results

Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the 22 patients who were enrolled on the crossover arms of the phase 2 trial after demonstrating progression of disease on placebo. Ten patients were treated with low-dose bevacizumab alone and 12 patients received low-dose bevacizumab in combination with thalidomide. Most patients were male, with a median age of 52 years for patients who received bevacizumab alone and 56 years for patients who received bevacizumab plus thalidomide. Eighty percent of patients who received bevacizumab alone and 67% of patients who received bevacizumab plus thalidomide had an ECOG performance status of 0. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to sex, age, ECOG performance status, or prior therapy. All but one patient had undergone prior nephrectomy, and all patients had previously undergone treatment with interleukin-2.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Bevacizumab | Bevacizumab + Thalidomide | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 10 | 12 |

| Male/female | 7/3 | 9/3 |

| Median age (years, range) | 52 (35–68) | 56 (41–62) |

| ECOG performance status (n, %) | ||

| 0 | 8 (80%) | 8 (67%) |

| 1 or 2 | 2 (20%) | 4 (33%) |

| Prior therapy (n, %) | ||

| Nephrectomy | 9 (90%) | 12 (100%) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (20%) | 4 (33%) |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (20%) | 2 (17%) |

| Interleukin-2 | 10 (100%) | 12 (100%) |

Patients in the bevacizumab plus thalidomide group underwent intrapatient dose escalation of thalidomide beginning at 200 mg/d to a maximum of 800 mg/d (Table 2). More than 50% of patients were escalated to at least 500 mg/d thalidomide. Only two patients achieved the 800-mg/d dose level, and one patient was treated with 700 mg/d. Seven patients demonstrated progression of disease during dose escalation (including the patient at the 700-mg/d dose level). One patient experienced grade 1 sensory neuropathy necessitating holding of his thalidomide dose at 500 mg/d and no further dose escalation. Two patients experienced grade 2 sensory neuropathy; symptoms resolved in both patients after cessation of thalidomide, and treatment was then restarted. Sensory neuropathy was manifested by perioral, hand, and/or foot paresthesia.

TABLE 2.

Highest Dose Thalidomide Achieved and Restrictions on Dose Escalation

| Dose Level (mg/d) | Number of Patients | Restriction on Dose Escalation |

|---|---|---|

| 800 | 2 | NA |

| 700 | 1 | PD |

| 500 | 4 | PD (2 patients), grades 1 and 2 sensory neuropathy |

| 300 | 3 | PD |

| 200 | 2 | PD, grade 2 sensory neuropathy |

NA, not applicable; PD, progression of disease.

Other toxicities related to treatment were few. One of the 10 patients (10%) treated with bevacizumab alone experienced one occurrence of grade 3 to 4 toxicity (hand weakness), compared with 3 of 12 patients (25%) who were treated with bevacizumab plus thalidomide. One patient treated with combination therapy experienced malignant hypertension, one patient experienced dizziness, and one patient demonstrated several abnormal laboratory parameters (elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated total bilirubin, hyponatremia) that were probably tumor-related.

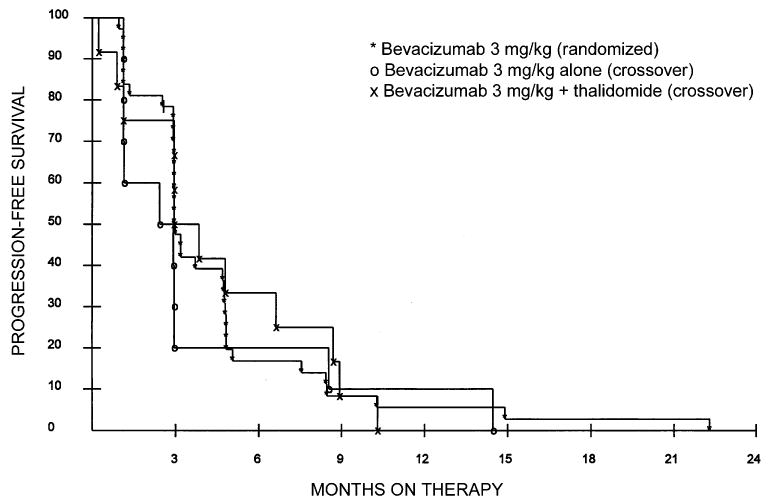

There were no objective responses in either group and no significant difference in progression-free survival between the groups (Fig. 1). Patients who were treated with bevacizumab alone had a median time to progression of 2.4 months compared with 3.0 months for patients who were treated with bevacizumab plus thalidomide (P = 0.63 for overall comparison). Progression-free survival was also not different between these groups of patients and the 37 patients who had been randomized to low-dose bevacizumab on the original phase 2 trial (each P > 0.40). Furthermore, there was no difference in the times to progression for the subset of 12 patients receiving combination therapy versus those same patients when they were receiving placebo (3.0 months vs. 2.5 months, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Progression-free survival of patients treated with bevacizumab alone or bevacizumab plus thalidomide on the crossover arm of a randomized phase 2 trial comparing high-dose bevacizumab, low-dose bevacizumab, and placebo. Each cohort was compared with patients who had been randomly assigned to the low-dose bevacizumab arm of the original phase 2 trial. There was no difference in time to progression between any of the groups (all P > 0.40).

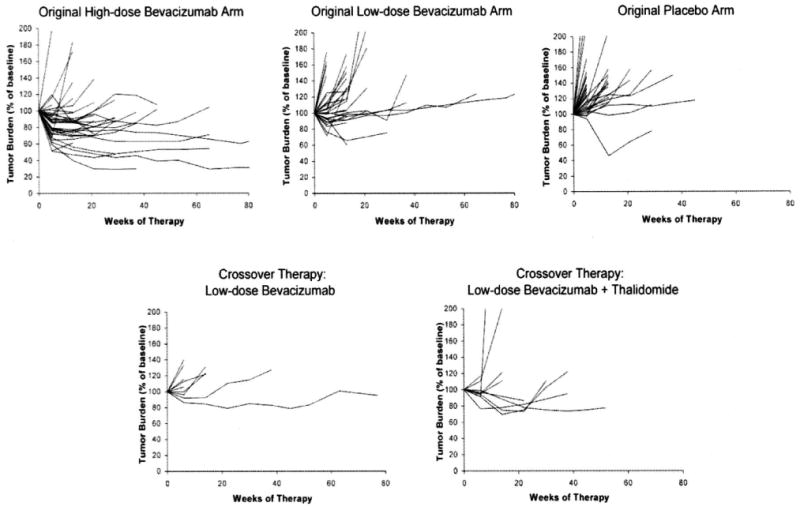

Because changes in tumor burden of patients in the three treatment arms of the randomized phase 2 bevacizumab trial appeared different, suggesting that this might be an important end point in trials of cytostatic and antiangiogenic agents, we also analyzed this parameter in evaluating patients receiving crossover therapy. Confirming the impression that tumor burden was affected by bevacizumab therapy, analysis of the phase 2 randomized trial showed a greater increase in tumor burden in patients receiving placebo compared with either dose of bevacizumab, and the increase in patients receiving low-dose bevacizumab was significantly greater than the increase in tumor in patients receiving high-dose bevacizumab (Fig. 2) (unadjusted P values after 5 weeks of therapy were 0.0003 for placebo vs. low-dose, <0.0001 for placebo vs. high-dose, and 0.0001 for low-dose vs. high-dose; after 13 weeks of therapy, they were 0.018, <0.0001, and <0.0001, respectively). Evaluation of the two crossover therapy cohorts showed that there was no significant difference in the change in tumor burden associated with the addition of thalidomide to low-dose bevacizumab, and the changes in tumor burden of these two cohorts were also not different from that seen in patients receiving 3 mg/kg bevacizumab on the randomized trial (see Fig. 2). There was also no difference between tumor burden changes in either of these groups compared with patients in the low-dose bevacizumab arm on the original randomized trial (all P > 0.30). When compared with the placebo arm of the original randomized trial, there was some tendency for the burden increase on placebo to be greater than the corresponding burden change on the crossover treatments by 5 weeks (P = 0.055 for bevacizumab alone and P = 0.004 for bevacizumab plus thalidomide), but this effect disappeared by the 13-week comparisons (P > 0.60 for both groups). This difference seemed attributable to the effect of low-dose bevacizumab alone.

FIGURE 2.

Changes in total tumor burden (expressed as a percentage of baseline tumor burden) over time in patients treated on the original randomized phase 2 trial9 and those treated with low-dose bevacizumab alone or bevacizumab plus thalidomide on the crossover arm of the trial. High-dose bevacizumab was associated with a statistically significant reduction in change in tumor burden (as assessed at 5 and 13 weeks) compared with either low-dose bevacizumab alone or placebo (P < 0.0001, Jonckheere test for trend). Combination therapy with thalidomide was not significantly different from either group who received low-dose bevacizumab alone.

Discussion

The treatment of metastatic RCC remains a challenging clinical problem. Targeted antiangiogenic strategies for the treatment of this malignancy have potential benefit based on the current understanding of the molecular events that drive the development of clear cell renal cancer. The regimen of bevacizumab plus thalidomide evaluated in this study represents the first attempt at treating metastatic RCC with combination antiangiogenic therapy. Each agent was chosen based on pre-clinical studies and toxicity data. Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, has recently been evaluated by our group in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on the basis of evidence implicating overexpression of VEGF in the pathogenesis of RCC.9 Thalidomide was selected for the crossover arm of this trial for combination with bevacizumab based on experimental evidence demonstrating abrogation of growth factor-induced angiogenesis10,11 and phase 2 studies suggesting efficacy in treating RCC.14–17

Despite the absence of any objective clinical response or difference in progression-free survival between patients who received bevacizumab alone versus bevacizumab plus thalidomide, this study illustrates the feasibility and safety of rapidly evaluating two antiangiogenic agents in combination using a technique of intrapatient dose escalation. Bevacizumab was administered at a predetermined fixed dose and thalidomide was started at a dose of 200 mg/d and escalated in 100-mg increments to a maximum dose of 800 mg/d. We showed that more than 50% of patients could tolerate a dose of at least 500 mg/d thalidomide in combination with 3 mg/kg bevacizumab. Neuropathy, a known side effect of thalidomide, prevented further dose escalation in 3 of 12 patients (25%). The incidence of grades 3 to 4 toxicity was not different between patients treated with bevacizumab plus thalidomide compared with those treated with bevacizumab alone.

The results of our phase 2 study comparing high-dose bevacizumab, low-dose bevacizumab, and placebo were not known at the time of the design of the crossover study.9 Low-dose bevacizumab was selected for the crossover arm based on toxicity and pharmacokinetic data from the original phase 1 study that evaluated this drug at escalating doses.18 Our phase 2 study demonstrated a 10% partial response rate to high-dose bevacizumab and no responses to low-dose bevacizumab, with a significant prolongation of time to progression for the high-dose bevacizumab arm versus placebo (P < 0.001), and an effect of only borderline significance (P = 0.053) seen with low-dose bevacizumab versus placebo. Moreover, assessment of changes in total tumor burden suggests stabilization of tumor burden in patients treated with high-dose bevacizumab compared with either low-dose bevacizumab or placebo (see Fig. 2). Thus, thalidomide may still have a potential clinical benefit in combination with high-dose bevacizumab. Nevertheless, the data from this crossover study may blunt enthusiasm for such a trial and aid in setting priorities for the testing of other candidate antiangiogenic combination therapies.

In conclusion, combination antiangiogenic therapy with low-dose bevacizumab plus thalidomide is associated with similar toxicity and progression-free survival compared with low-dose bevacizumab alone. If cancers use more than one angiogenic mechanism to generate a blood supply (as is likely), then single-agent antiangiogenic therapies will be relatively ineffective, while combinations could have dramatic therapeutic effects. It is logistically daunting, however, to perform clinical trials with agents that cannot demonstrate definitive single-agent activity, mixed in increasingly complex combinations. One strategy is to start with an agent with some evidence of in vivo bioactivity and, using intrapatient dose escalation, aggressively add a second candidate agent for which safety and toxicity data are available. Studies using small cohorts of patients treated in this manner can rapidly screen for major antiangiogenic synergy but may forego the detection of smaller clinical benefits. Expediting the evaluation of efficacy while potentially increasing the exposure of patient volunteers to unexpected toxicities may represent an acceptable trade-off for patients with advanced metastatic disease who are in urgent need of new effective therapies.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–2540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elson PJ, Witte RS, Trump DL. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1988;48:7310–7313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Dorey F, et al. Mathematical model to predict individual survival for patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1368–1374. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher RI, Coltman CA, Jr, Doroshow JH, et al. Metastatic renal cancer treated with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. A phase II clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:518–523. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-4-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quesada JR. Role of interferons in the therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 1989;34:80–83. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(89)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, White DE, et al. Durability of complete responses in patients with metastatic cancer treated with high-dose interleukin-2: identification of the antigens mediating response. Ann Surg. 1998;228:307–319. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnarra JR, Tory K, Weng Y, et al. Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat Genet. 1994;7:85–90. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab (anti-VEGF antibody) demonstrating a delay in tumor progression in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, et al. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4082–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruse FE, Joussen AM, Rohrschneider K, et al. Thalidomide inhibits corneal angiogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:461–466. doi: 10.1007/s004170050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amato R. Thalidomide for recurrent renal-cell cancer in a 40-year-old man. Oncology (Huntingt) 2000;14:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen T, Boshoff C, Mak I, et al. Continuous low-dose thalidomide: a phase II study in advanced melanoma, renal cell, ovarian and breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:812–817. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Berg W, Ginsberg M, et al. Phase II trial of thalidomide for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:302–306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minor DR, Monroe D, Damico LA, et al. A phase II study of thalidomide in advanced metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20:389–393. doi: 10.1023/a:1020669705369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escudier B, Lassau N, Couanet D, et al. Phase II trial of thalidomide in renal-cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1029–1035. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon MS, Margolin K, Talpaz M, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:843–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]