Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway of leptin signaling plays an important role in transducing leptin action in the hypothalamus. Obesity is usually associated with resistance to the effect of leptin on food intake and energy homeostasis. Although central leptin resistance is thought to be involved in the development of diet-induced obesity (DIO), the mechanism behind this phenomenon is not clearly understood. To determine whether DIO impairs the effect of leptin on hypothalamic PI3K signaling, we fed 4-wk-old FVB/N mice a high-fat diet (HFD) or low-fat diet (LFD) for 19 wk. HFD-fed mice developed DIO in association with hyperleptinemia, hyperinsulinemia, and impaired glucose and insulin tolerance. Leptin (ip) significantly increased hypothalamic PI3K activity and phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) levels in LFD-fed mice but not in DIO mice. Immunocytochemical study confirmed impaired p-STAT3 activation in various hypothalamic areas, including the arcuate nucleus. We next tested whether both PI3K and STAT3 pathways of leptin signaling were impaired during the early period of DIO. Leptin failed to increase PI3K activity in DIO mice that were on a HFD for 4 wk. However, leptin-induced p-STAT3 activation in the hypothalamus measured by Western blotting and immunocytochemistry remained comparable between LFD- and HFD-fed mice. These results suggest that the PI3K pathway but not the STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling is impaired during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice. Thus, a defective PI3K pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus may be one of the mechanisms of central leptin resistance and DIO.

OBESITY IS ONE of the major health problems throughout the world, particularly in the United States (1). A large body of evidence suggests that leptin, a product of the obese gene (2), signals nutritional status to key regulatory centers in the hypothalamus, and it has emerged as a major signal regulating energy homeostasis by decreasing food intake and increasing energy expenditure (3,4,5,6). Paradoxically, in the majority of cases, human obesity cannot be attributed to defects in leptin or its receptor (7,8,9,10,11,12,13). Serum leptin levels are significantly higher in obese humans relative to nonobese humans (6,14), and leptin administration shows very limited response in obese people (15), suggesting a state of leptin-resistance in obese individuals. Thus, understanding the mechanism of leptin resistance is quite significant in developing a new approach to prevent or treat obesity and associated disorders.

It has been evident that humans or rodents made obese by dietary manipulation have elevated levels of circulating leptin but maintain a normal food intake (6,14,16). Although a defective leptin transport may be one of the many factors behind the development of leptin resistance (17,18,19), available data from diet-induced obese (DIO) rodents, which may represent the form of obesity seen in most humans, strongly suggest that central leptin resistance also contributes to the development of obesity. Thus, anorectic effect of central leptin is reduced in DIO rats (20,21) and DIO mice (22); nutritional regulation of leptin receptor gene expression in the hypothalamus is defective in DIO rats (23), and leptin signaling in the hypothalamus through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is reduced in DIO mice (24). In obesity prone rats, gene expression of the long form of the leptin receptor (Ob-Rb) and leptin-induced STAT3 activation in the hypothalamus is compromised before the development of obesity or exposure to a high-energy diet (25). In addition, DIO in rodents is associated with increased expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), a negative regulator of the leptin signaling pathway (26,27), in the hypothalamus (28). Furthermore, hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway of leptin signaling is also defective in DIO mice (29). Therefore, it is possible that those signaling pathways, which have been implicated to play a significant role in leptin action in the hypothalamus but not yet studied for their role in DIO, could be defective and contribute to the development of DIO.

In this regard, we have demonstrated that leptin signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-phosphodiesterase 3B-cAMP pathway plays a critical role in transducing leptin action in the hypothalamus (30). Other investigators have shown that leptin increases PI3K in the hypothalamus, and PI3K inhibitor reverses the anorectic effect of leptin (31). In addition, PI3K is localized in the hypothalamus (32); leptin induces PI3K in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, and leptin withdrawal activates PI3K in AgRP neurons in hypothalamic slice preparation (33). PI3K inhibitors reverse the effect of leptin on NPY and AgRP gene expression (34). Leptin also increases the activity of K-ATP channels in arcuate nucleus (ARC) neurons in a PI3K-dependent manner in vitro (35). Furthermore, more recently Kim et al. (36) showed PI3K signaling pathway to be upstream of forkhead transcriptional factor subfamily forkhead box O1 (Foxo1) in hypothalamic neurons, and PI3K-Akt-Foxo1 signaling pathway to mediate the effects of leptin and insulin on the transcriptional regulation of NPY/AgRP and POMC neurons. Thus, regulation of Foxo1 by PI3K in the hypothalamus appears to play an important role in food intake and energy homeostasis (36,37). Altogether, these lines of evidence clearly establish an important role of PI3K signaling in transducing leptin action in the hypothalamus. Thus, it is most likely that central leptin resistance seen during the development of DIO is due, at least in part, to an impaired PI3K pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus. The present study tested this hypothesis in FVB/N mice that developed DIO in response to high-fat diet (HFD) feeding. Although many studies have used FVB/N background for developing transgenic mice (38,39,40,41,42), studies related to DIO in FVB/N mice are relatively few with the report of either an increase (40,29) or no change (39,41) in body weight after a HFD feeding. Although these discrepancies may be related to percentage of fat, diet composition, and duration of HFD feeding, hypothalamic mechanisms of leptin signaling during the development of DIO are relatively unknown in these mice (29). Therefore, we examined if the PI3K pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus was altered during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male FVB/N mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) at approximately 3 wk of age, and were maintained in a light (lights on 0500–1900 h) and temperature-controlled (22 C) room with food (pelleted rodent chow) and water available ad libitum. After 4-d acclimatization, mice were subjected to the following experiments, all of which were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

Experiment 1: effects of long-term HFD feeding on food intake, body weight, and metabolic parameters, and on leptin-induced PI3K activity and phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) levels in the hypothalamus

Four-week-old male mice were housed in a group of four per cage and provided with either standard mouse chow [low-fat diet (LFD)] (6% kcal as fat; F6 rodent diet, no. 8664; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) or a HFD (58% kcal as fat; no. D12331; Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ). Body weights were measured twice per week. Food intake was measured at 16-wk dieting in the animals that were individually caged at least 1 wk before the study. Blood glucose levels were measured in tail vein samples by Precision-Xtra Strips (Medisense Products, Bedford, MA) in overnight fasted animals on a HFD or LFD for 16 wk. A glucose tolerance test was performed in overnight fasted animals on a HFD or LFD for 14 wk. Animals were injected with d-glucose (2 g/kg body weight, ip), and blood glucose values were determined from the tail vein samples at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min after injection. An insulin tolerance test (ITT) was done on fasted (1 h) animals on a HFD or LFD for 15 wk. Blood glucose levels were measured from the tail vein samples at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min after injection of porcine insulin (0.75 mIU/g body weight, ip).

To examine the effect of leptin on PI3K and p-STAT3 levels, mice fed with a HFD or LFD for 19 wk were fasted overnight and then injected ip with leptin (5 mg/kg; A. F. Parlow, National Hormone & Peptide Program, Torrance, CA) or saline. Thirty minutes later, mice were killed by decapitation. Brains were removed immediately, and the medial basal hypothalamus (MBH) was dissected out, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80 C until processing for protein extraction. The MBH tissue was bounded rostrally by the posterior border of the optic chiasma, laterally by the lateral sulcus, and caudally by the mammillary bodies, and cut to a depth of approximately 1.5 mm. Trunk blood was collected for insulin and leptin determination. Epididymal (E) fat, retroperitoneal (RP) fat, and brown adipose tissue (BAT) were dissected out and weighed.

To examine whether p-STAT3 activation was altered in specific regions of the hypothalamus, some mice from each group were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused intracardially with 0.9% saline kept at room temperature, followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. The brains were postfixed in the same fixative for overnight and then kept in 20% sucrose solution at 4 C until they sank. Thereafter, brains were frozen on dry ice, and coronal 25-μm free-floating sections were cut in five series through the hypothalamus on a freezing microtome (Leica Sliding Microtome; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), and stored in cryoprotectant at −20 C until use. One series was subjected to immunocytochemistry (ICC).

Experiment 2: effects of short-term HFD feeding on food intake, body weight, and metabolic parameters, and on leptin-induced PI3K activity and p-STAT3 levels in the hypothalamus

This experiment was similar to that described previously except that mice were fed with specific diet for a period of 4 wk. Food intake was measured in individually housed animals at d 18–25 of dieting. Body weight was measured twice weekly. At the end of 4-wk dieting, the animals were fasted overnight, followed by leptin (5 mg/kg, ip) or saline injection. Thirty minutes later, the MBH was dissected out, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and processed for protein extraction. Trunk blood was collected for determination of circulating leptin and insulin levels. E fat, RP fat, and BAT were dissected out and weighed.

To examine p-STAT3 activation by ICC, some animals were perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were postfixed, equilibrated with sucrose solution, frozen on dry ice, and processed for sectioning as described previously (experiment 1).

Measurement of PI3K activity

PI3K activity in the hypothalamus was measured according to a standard protocol as described elsewhere (43), and which we used in a recent study (44). Briefly, MBH protein was extracted with an extraction buffer (50 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Na-pyrophosphate, 20 mm B-glycerophosphate, 10 mm NaF, 2 mm NaVO, 2 mm EDTA, 1% 1GEPAL, 10% glycerol, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin). Two hundred fifty micrograms of MBH protein were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) antibody (Sc-559, polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) for 2 h at 4 C, followed by precipitation of the immunocomplexes with 80 μl protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences Inc., Piscataway, NJ) for 1.5 h at 4 C. The immune complex was then incubated at 22 C with phosphatidylinositol (10 μg; Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., Alabaster, AL) in the presence of 50 μm [γ-32P]ATP (5 μCi; PerkinElmer Life And Analytical Sciences, Inc., Waltham, MA). The reaction was stopped by adding 20 μl 8 N HCl and 160 μl CHCl3:methanol (1:1), followed by centrifugation for 3 min at 14,000 rpm in a Microfuge (Marathon micro A, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The lower organic phase with 32P-containing PI(3)P was separated on a silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate. 32P-containing PI(3)P was quantitated with phosphor-imaging (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Measurement of p-STAT3 levels in the hypothalamus by Western blotting

To measure p-STAT3 levels, aliquots of MBH protein extracts used in the PI3K assay were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer of the resolved polypeptides to polyscreen polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were then blotted with p-STAT3 antibody (p-STAT3: B7, monoclonal, Sc-8059; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by enhanced chemoluminescence as described by the manufacturer (New England Nuclear Life Science Products Life Sciences, Boston MA). The membranes were stripped and then blotted with STAT3 (K-15, polyclonal, Sc-483; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). P-STAT3 levels were first calculated as the ratio of STAT3 protein and then expressed as relative to saline control.

ICC for p-STAT3 localization in the hypothalamus

The ICC localization of p-STAT3 immunoreactive protein in the hypothalamus was done according to the method described previously by Munzberg et al. (28) with slight modifications. Briefly, free floating tissue sections were pretreated with 1% NaOH and 1% H2O2 in H2O for 20 min, 0.3% glycine for 10 min, and 0.03% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 10 min. Sections were then blocked for 1 h with blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in PBS, 1% BSA, 0.4% Triton X-100), followed by incubation with p-STAT3 antibody (1:3000 in blocking solution; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA) for overnight at 4 C. On the next day, the sections were washed, incubated with biotinylated secondary goat antirabbit antibody (1:4000, in blocking solution) for 1 h, and then treated with avidin-biotin-complex solution for 1 h. Finally, the signal was developed by diaminobenzidine solution containing 0.6% nickel sulfate, giving a dark-blue precipitate.

Cell counting and quantification

As stated previously, brain sections (25 μm) were cut in five series through the MBH. One series was subjected to ICC. All sections were organized systematically in a rostral-to-caudal manner according to the mouse brain atlas (45), and then counted under light microscope for p-STAT3 positive cells in specific areas of the MBH, including the ARC, ventromedial nuclei (VMN), and dorsomedial nuclei (DMN). Cells were counted from both sides of the brain in each section. The data are presented as total number of p-STAT3 positive cells in each nucleus in one of five series in each animal.

Leptin, insulin, and glucose determination

Plasma leptin (Crystal Chem, Inc., Downers Grove, IL) and insulin (LINCO Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO) levels were determined with commercial kits. Circulating glucose levels were measured with Precision-Xtra Strips.

Data analysis

All values are expressed as means ± se. Statistical significance of differences in food intake and body weight was analyzed using repeated measures one or two-way ANOVA with post hoc testing using the Student-Newman-Keuls multiple-range test. All other data were analyzed by randomized one-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls multiple-range test. All statistical analyses were done using GB-Stat software for the Macintosh (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). Comparisons with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Changes in food intake, body weight, fat pad weight, and metabolic parameters after long-term HFD feeding in FVB/N mice

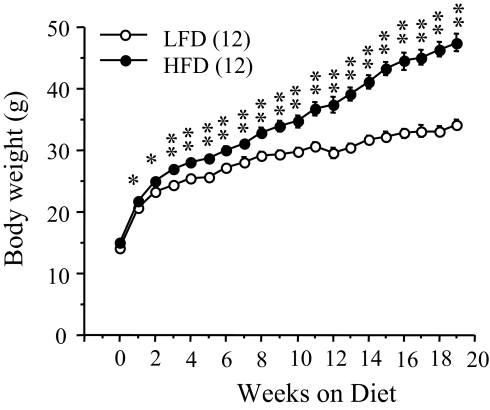

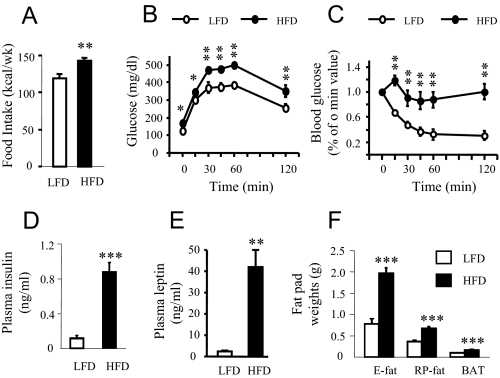

Male FVB/N mice were randomly assigned to either a LFD or HFD at 4 wk of age, when body weight was not different between the groups. The mice achieved significant body weight gain when they were put on a HFD. As shown in Fig. 1, the body weight of HFD-fed mice was significantly (P = 0.016) increased within 1-wk dieting compared with LFD-fed mice. Body weight gain remained significantly higher and continued to diverge throughout 19 wk on the HFD, and at the end, the body weight difference between the groups reached approximately 11.5 g. Cumulative food intake (at 16 wk on the diet) was significantly increased (P = 0.0067) in the HFD group compared with the LFD group (Fig. 2A). The HFD group showed hyperglycemia (tested at 17 wk, LFD: 102.5 ± 6.91 mg/dl; HFD: 164.87 mg/dl; P < 0.0001; n = 8 per group), hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 2D; P = 0.0001), and hyperleptinemia (Fig. 2E; P = 0.003), and reduced insulin sensitivity (assessed by GTT and ITT at 14 and 15 wk, respectively) when compared with the LFD group (Fig. 2, B and C). In addition, fat pad weights (E fat, RP fat, and BAT) were significantly increased (P < 0.001) in the HFD compared with those in the LFD group (Fig. 2F).

Figure 1.

Body weight changes in FVB/N mice fed with a LFD or HFD for 19 wk. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 vs. LFD-fed group. Values represent the mean ± sem for the number of animals indicated in parentheses.

Figure 2.

Changes in food intake, plasma insulin, and leptin levels, and glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and in fat pad weights after long-term dieting with a LFD or HFD. A, Food intake in HFD or LFD-fed mice at 16 wk. **, P < 0.01 (n = 8 per group). B, glucose tolerance tests in overnight fasted mice at 14 wk on the diet. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (n = 6 per group). C, ITTs in 1-h fasted mice at 15 wk on the diet. **, P < 0.01 (n = 7–8 per group). D, Fasted plasma insulin levels at 19 wk. ***, P < 0.001 (n = 5 per group). E, Fasted plasma leptin levels at 19 wk. **, P < 0.01 (n = 5 per group). F, Fat pad weights at 19 wk. ***, P < 0.001 (n = 11–12 per group).Values represent the mean ± sem.

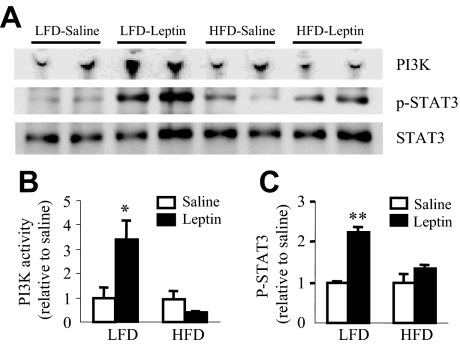

Changes in leptin-induced PI3K activity and P-STAT3 levels in the hypothalamus after long-term HFD feeding in FVB/N mice

The STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling is defective in the hypothalamus of DIO C57BL/6J (C57) mice (24,28). This study examined if hypothalamic PI3K signaling was altered during DIO in FVB/N mice. At 19 wk on the diet, ip leptin injection induced PI3K activity by 2.3-fold (P = 0.01) and p-STAT3 levels by 2.2-fold (P = 0.0002) in the MBH extract of LFD-fed but not in HFD-fed mice (Fig. 3), suggesting alteration of both PI3K and p-STAT3 signaling in DIO mice.

Figure 3.

Changes in leptin-induced IRS-1 associated PI3K activity and in p-STAT3 in the hypothalamus at 19 wk on a LFD or HFD. A, Representative phosphor-images obtained from the TLC plate showing PI(3)P production, an indicator of PI3K activity, are shown. Also shown are p-STAT3 and STAT3 Western blots obtained from the hypothalamic extract used in the PI3K assay. B, Results obtained by phosphor-imaging showing the changes in PI3K activity. The values are expressed as relative to the corresponding saline (control) group. *, P < 0.05 vs. saline group (n = 4 per group). C, Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactive bands for p-STAT3. The values were first calculated as the ratio of STAT3 and then expressed as relative to the corresponding saline (control) group. Values represent the mean ± sem for three to four animals per group. **, P < 0.001 vs. saline control group.

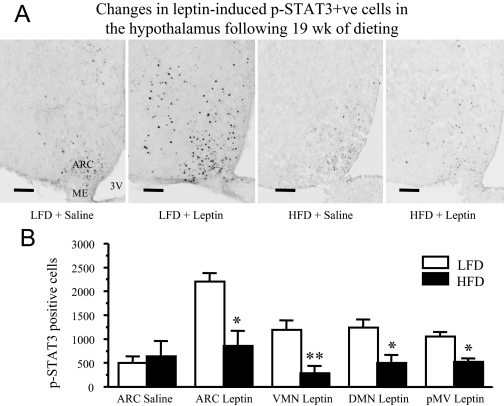

To address if the change in p-STAT3 in response to leptin was confined to specific hypothalamic nuclei, we examined the number of p-STAT3 positive cells in various hypothalamic nuclei by ICC. As expected, leptin significantly increased the number of p-STAT3 positive neurons in the ARC (Fig. 4A), and in VMN, DMN, and ventral premammillary nucleus (pMV) areas (data not shown) in LFD-fed mice compared with that in saline-treated animals (Fig. 4). However, there were very few p-STAT3 positive cells in the lateral hypothalamus after leptin treatment. In HFD-fed mice, leptin failed to induce a significant increase in the number of p-STAT3 positive cells in any of these hypothalamic nuclei; as a result, the number of p-STAT3 positive cells in all of these hypothalamic nuclei was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in HFD-fed compared with that in LFD-fed mice (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Changes in leptin-induced p-STAT3 positive cells in the hypothalamus after 19-wk dieting. A, Representative microphotographs of p-STAT3 ICC of hypothalamic sections from saline or leptin-treated FVB/N mice that were on a LFD or HFD for 19 wk. Mice were fasted overnight and injected with leptin (5 mg/kg, ip) or saline and killed 30 min later. Images are representative sections at approximately bregma −1.9. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, The number of p-STAT3 positive cells in various leptin target sites in the hypothalamus of LFD (n = 2) and HFD (n = 3) fed mice. One of five series from each animal was analyzed. Values represent the mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs. LFD group. ME, Median eminence; 3V, third ventricle.

Changes in food intake, body weight, fat pad weight, and metabolic parameters after short-term HFD feeding in FVB/N mice

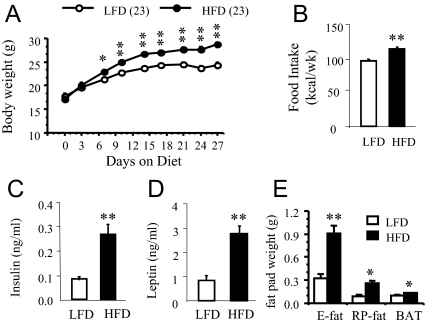

Body weight was significantly increased (P < 0.01) within 1-wk HFD feeding (Fig. 5A). At the end of 4 wk, the body weight difference between the HFD and LFD groups reached approximately 4 g. Cumulative food intake for 7 d (assessed during 18- to 25-d dieting) was significantly increased in the HFD group (LFD: 97.62 ± 2.24 kcal, HFD: 115.29 ± 2.50 kcal; P < 0.0001; Fig. 5B). Weights of E fat (P = 0.0001), RP fat (P = 0.001), and BAT (P = 0.007) were significantly increased in the HFD group compared with that of the LFD group (Fig. 5E). In addition, the HFD group was hyperleptinemic (LFD: 0.84 ± 0.19 ng/ml, HFD: 2.76 ± 0.32 ng/ml; P = 0.0003; Fig. 5D) and hyperinsulinemic (LFD: 0.081 ± 0.011 ng/ml, HFD: 0.262 ± 0.039 ng/ml; P = 0.0006; Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Changes in body weight, food intake, plasma insulin, and leptin levels, and fat pad weights after short-term dieting with a LFD or HFD. A, Body weight change during 4-wk dieting. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (n = 23 per group). B, Food intake in HFD or LFD-fed mice during18- to 15-d dieting. **, P < 0.0001 (n = 13–14 per group). C, Fasted plasma insulin levels at 4 wk. **, P < 0.001 (n = 8 per group). D, Fasted plasma leptin levels at 4 wk. **, P < 0.001 (n = 7 per group). E, Fat pad weights at 4 wk. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (n = 12 per group). Values represent the mean ± sem.

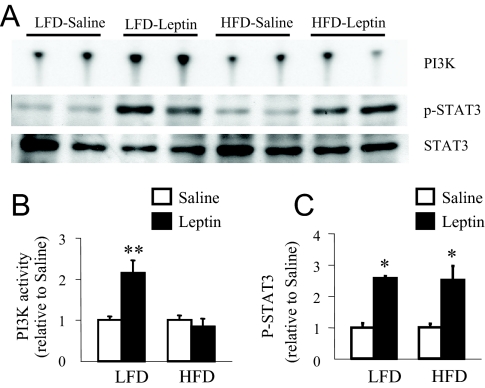

Changes in leptin-induced PI3K activity and P-STAT3 levels in the hypothalamus after 4-wk HFD feeding in FVB/N mice

To address whether the defect in leptin signaling seen after 19-wk HFD feeding occurs during the early period of DIO, we examined the effects of leptin on PI3K and p-STAT3 levels in the MBH of mice on the diet for 4 wk. Leptin significantly increased both PI3K activity (P < 0.01) and p-STAT3 levels (P < 0.05) in the MBH of LFD-fed mice (Fig. 6). Interestingly, whereas leptin also increased p-STAT3 levels (P < 0.01), it failed to increase PI3K activity in the MBH of HFD-fed mice.

Figure 6.

Changes in leptin-induced IRS-1 associated PI3K activity and in p-STAT3 in the hypothalamus at 4 wk on a LFD or HFD. A, Representative phosphor-images obtained from the TLC plate showing PI(3)P production, an indicator of PI3K activity, are shown. Also shown are p-STAT3 and STAT3 Western blots obtained from the hypothalamic extract used in the PI3K assay. B, Results obtained by phosphor-imaging showing the changes in PI3K activity. The values are expressed as relative to the corresponding saline (control) group. **, P < 0.01 (n = 6 per group). C, Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactive bands for p-STAT3. The values were first calculated as the ratio of STAT3 and then expressed as relative to the corresponding saline (control) group. *, P < 0.05 vs. saline control group (n = 5–6 per group).

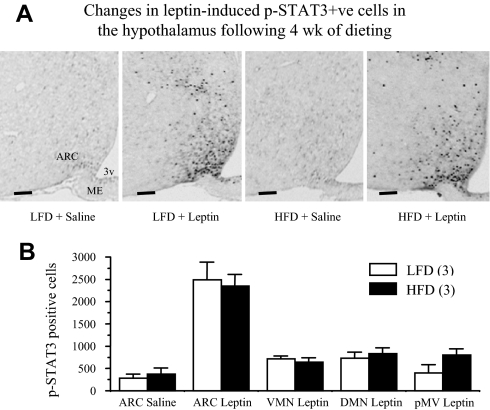

The ICC study showed the presence of some p-STAT3 positive cells in the ARC of vehicle (saline) control animals in both LFD and HFD groups, but these cells were almost absent in other hypothalamic nuclei. After leptin administration the number of p-STAT3 positive cells was significantly increased (P < 0.01) in the ARC of both LFD and HFD groups compared with control saline group (Fig. 7A). Leptin also induced p-STAT3 in the cells of the VMN (P < 0.01), DMN (P < 0.01), and pMV (P < 0.01) regions in both groups. There were no significant differences in the number of p-STAT3 positive cells in any of the nuclei examined between LFD and HFD groups (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that p-STAT3 activation in various hypothalamic nuclei was comparable between lean and DIO animals.

Figure 7.

Changes in leptin-induced p-STAT3 positive cells in the hypothalamus after 4-wk dieting. A, Representative microphotographs of p-STAT3 ICC of hypothalamic sections from saline or leptin treated FVB/N mice on a LFD or HFD for 4 wk. Mice were fasted overnight and injected with leptin (5 mg/kg, ip) or saline and killed 30 min later. Images are representative sections at approximately bregma −1.85. Scale bars, 100 μm; B, The number of p-STAT3 positive cells in various leptin target sites in the hypothalamus of LFD (n = 3) and HFD (n = 3) fed mice. One of five series from each animal was analyzed. Values represent the mean ± sem. ME, Median eminence; 3v, third ventricle.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that: 1) FVB/N mice developed DIO when fed with a HFD for 4 or 19 wk, 2) both PI3K and p-STAT3 pathways of leptin signaling were impaired in the hypothalamus after 19-wk HFD feeding, and 3) PI3K but not the p-STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling was impaired in the hypothalamus at 4-wk HFD feeding. In addition, impairment in p-STAT3 signaling during 19-wk HFD feeding occurred not only in the ARC but also in the VMN, DMN, and pMV regions of the hypothalamus in FVB/N mice.

Rodent models of DIO represent the condition occurring in most obese humans, and, therefore, understanding the mechanisms behind the development of DIO in rodents may shed some light on the possible mechanisms in human obesity. Because leptin signaling in the hypothalamus is obligatory for normal food intake and body weight maintenance (6,46,47,48), and the majority of obese humans and DIO rodents are hyperleptinemic (14,15,16,17,22,23,24,28), leptin resistance is thought to be the reason behind the development of DIO. Whereas a large body of evidence suggests that central leptin resistance contributes to the development of DIO (20,21,22,23,24,25,28,29), the molecular mechanisms behind this phenomenon are not clearly understood. Because signaling through STAT3 plays a critical role in leptin action in the hypothalamus and energy homeostasis (49) and brain-specific STAT3 deficiency results in obese phenotype (50), major focus has been on identifying if STAT3 signaling was impaired during DIO. Accordingly, a defect in STAT3 activation by leptin in the hypothalamus (24), particularly in the ARC (28), has been reported in DIO C57 mice. With regard to the other pathways, an alteration of AMPK pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus and muscle has been reported in FVB/N DIO mice (29). Because cumulative evidence suggests that PI3K signaling plays an important role in transducing leptin action in the hypothalamus (30,31,33,34), the major objective of the present study was to evaluate if the PI3K pathway of leptin signaling was impaired in the hypothalamus of FVB/N DIO mice and to compare it with STAT3 signaling. In agreement with previous studies (28,34), FVB/N mice had significant increase in weight gain within 1-wk HFD feeding and continued to show increased body weight gain throughout 19-wk dieting. This weight gain was associated with increased calorie intake and fat pad weights, and with hyperglycemia, hyperleptinemia, and hyperinsulinemia that are characteristics of DIO.

In the first experiment, we investigated if leptin signaling via PI3K and STAT3 pathways in the hypothalamus was impaired after 19-wk HFD feeding. We demonstrate that leptin-induced increase in hypothalamic PI3K activity and p-STAT3 levels seen in LFD-fed lean mice is absent in HFD-fed DIO mice. To determine if impairment in STAT3 signaling was restricted only to the ARC of the hypothalamus as reported in DIO C57 mice (28), we examined p-STAT3 activation in various hypothalamic sites by ICC. Leptin significantly increased the number of p-STAT3 positive cells in the ARC, VMN, DMN, and pMV of the lean LFD-fed mice, but not in the HFD-fed DIO mice. Our observation in the ARC agrees with the findings of Munzberg et al. (28), but in contrast to their report, we show that leptin also failed to increase p-STAT3 positive cells in the VMN, DMN, and pMV regions of the hypothalamus in HFD-fed DIO mice. Although the reason behind this discrepancy remains unknown, it could be ascribed to strain differences and/or the longer duration of the HFD feeding (19 vs. 16 wk) in the present study. It is possible that leptin resistance in p-STAT3 activation could still be restricted only to the ARC at an earlier period than at 19-wk HFD feeding. Nevertheless, our finding suggests that in FVB/N DIO mice, resistance in the STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling occurs throughout the hypothalamus, including the ARC, VMN, DMN, and pMV in DIO animals after 19 wk on a HFD. These findings suggest impairment in both PI3K and STAT3 pathways of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus after long-term HFD feeding in FVB/N DIO mice.

To address whether defective leptin signaling through these pathways seen after 19-wk DIO could be detected at an earlier period during the development of obesity, we examined leptin signaling in the hypothalamus in mice after a HFD for 4 wk. As reported in C57 mice (28), FVB/N mice showed increased body weight gain with in 1-wk HFD feeding, and became hyperleptinemic and hyperinsulinemic. In addition, fat pad weights were significantly increased, suggesting the development of DIO. Calorie intake and body weight were increased despite hyperleptinemia, suggesting the development of leptin resistance. Comparison of PI3K activity and p-STAT3 levels in the hypothalamus in response to leptin shows that PI3K but not the STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling is impaired in DIO mice at 4 wk on a HFD. The results of leptin-induced p-STAT3 activation in FVB/N DIO mice after 4 wk on a HFD are in contrast to those in C57 mice, in which p-STAT3 activation specifically in the ARC has been impaired (28). To address the possibility that a defect in leptin-induced p-STAT3 levels may still occur in specific hypothalamic nuclei that could be obscured by examination of p-STAT3 levels in whole hypothalamic extract, we examined p-STAT3 activation in hypothalamic nuclei by ICC. We demonstrate that leptin-induced p-STAT3 activation in the ARC, VMN, DMN, and pMV areas of the hypothalamus remains intact after 4-wk HFD feeding. These results suggest that the STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling is not impaired during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice. Our results are in agreement with a recent report showing intact p-STAT3 activation by leptin in various hypothalamic nuclei, including the ARC in FVB/N DIO mice on a HFD for 5 wk (29). Overall, it appears that the PI3K pathway of leptin signaling is impaired before the STAT3 pathway becomes defective during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice.

Because STAT3 signaling in the hypothalamus is critical in transducing leptin action (49,50), the development of DIO despite an intact STAT3 signaling in FVB/N mice at 4-wk HFD feeding is of considerable interest. This finding suggests that impairments in other pathways, such as the PI3K pathway seen in the present study and AMPK pathway reported by Martin et al. (29), could be involved in the development of DIO in FVB/N mice. After the development of DIO, the STAT3 pathway also becomes impaired and contributes to the maintenance of DIO on a HFD. However, it is difficult to assume the relative contribution of the impaired PI3K pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus in the development of DIO in FVB/N mice. In addition, because the whole hypothalamus extract was used for PI3K assay, it is also difficult to predict the site(s) of impairment or the neuropeptidergic systems in which PI3K signaling was impaired during the development of DIO. It has been shown that leptin induces PI3K activity in the POMC neurons and removal of leptin induces PI3K activity in the NPY/AgRP neurons (33), PI3K inhibitor reverses the inhibitory effect of leptin on NPY/AgRP gene expression in the hypothalamus (34), and the PI3K-Foxo1 pathway mediates the effect of leptin and insulin on AgRP/NPY and POMC neurons (36,37). Whereas these findings suggest an important role of PI3K signaling in transducing leptin action in these neurons in regulation of energy homeostasis, whether PI3K activity is impaired in the POMC and/or NPY/AgRP neurons during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice remains to be seen. Nevertheless, impaired PI3K activity in the hypothalamus should alter the responsiveness of these and other unidentified PI3K-dependent leptin target neurons, if any, to leptin and contribute to the development of DIO.

The underlying mechanisms behind the development of selective leptin resistance in the PI3K pathway but not in the STAT3 pathway of signaling at 4-wk HFD feeding are unknown. Although change in leptin receptor expression is a possibility but not examined in this study, there are conflicting results in this area. Some studies have shown no change (23,28,51), but others have shown a decrease (22,53) in Ob-Rb mRNA levels in the hypothalamus of DIO animals. Other possibilities include an increase in the negative regulator of leptin signaling, such as SOCS3 (26,27) and PTP1-B (54,55). Thus, in C57 mice increased SOCS3 expression in the ARC has been reported within 7-d HFD feeding (28). Brain-specific SOCS3 deletion or whole body SOCS3 haploinsufficiency results in resistance to DIO (56,57). It has been proposed that SOCS3 induction is one of the underlying mechanisms of central leptin resistance during DIO (28). In addition, PTP-1B deficiency also protects mice from the development of DIO (54,55,58,59). Thus, it remains to be seen if SOCS3 and/or PTP-1B expression is increased in the hypothalamus at the 4-wk or earlier period of HFD feeding in FVB/N mice, which could be involved in altered PI3K activity. Notably, similar to the present finding, we have recently shown that leptin signaling through the STAT3 pathway remains intact, but the PI3K pathway becomes impaired during the development of resistance to the satiety action of leptin (44,60,61), and the development of leptin resistance in the NPY and POMC neurons in a rat model of chronic central leptin infusion (60,62). Interestingly, SOCS3 mRNA and protein levels are increased, and leptin receptor mRNA levels and receptor phosphorylation remain normal during leptin resistance after chronic central leptin infusion (61). In addition, our recent finding that SOCS3 overexpression in the POMC neuronal cell line completely reverses the effect of leptin on PI3K signaling (52) raises the possibility that increased SOCS3, if it does occur, could be responsible for impaired PI3K signaling in the hypothalamus of FVB/N DIO animals. These possibilities will be tested in future studies. It also remains to be seen if an experimental increase or decrease of PI3K signaling by overexpression or deletion of PI3K subunits in the hypothalamus or in specific neurons, particularly in the NPY/AgRP or POMC neurons, could alter the response to DIO.

In summary, high-fat feeding results in impairment in PI3K but not the STAT3 pathway of leptin signaling during the development of DIO in FVB/N mice, followed by impairment in both PI3K and STAT3 signaling as the animals are exposed to a HFD for a longer period. We conclude that impairment in the PI3K pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus is another mechanism that could be involved in the development of central leptin resistance and DIO. Thus, targeting the PI3K pathway in the hypothalamus could be a viable option for the treatment or prevention of DIO.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Zhao, W. Huang, and R. M. O’Doherty for advice in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase assay. We also thank A. F. Parlow and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Hormone & Pituitary Program (Torrance, CA), for supplying the recombinant murine leptin.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 Grant DK61499 (to A.S.).

A part of the work was presented at the 88th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Boston, MA, 2006.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 29, 2007

Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-Activated protein kinase; ARC, arcuate nucleus; BAT, brown adipose tissue; C57, C57BL/6J; DIO, diet-induced obesity; DMN, dorsomedial nuclei; E, epididymal; Foxo1, forkhead transcriptional factor subfamily forkhead box O1; HFD, high-fat diet; ICC, immunocytochemistry; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; ITT, insulin tolerance test; LFD, low-fat diet; MBH, medial basal hypothalamus; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; pMV, ventral premammillary nucleus; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; p-STAT3, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; RP, retroperitoneal; SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; VMN, ventromedial nuclei.

References

- Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP 2001 The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA 286:1195–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM 1994 Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372:425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P 1995 Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269:546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM 1995 Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 269:543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F 1995 Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 269:540–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL 1998 Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature 395:763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang-Christensen M, Havel PJ, Jacobs RR, Larsen PJ, Cameron JL 1999 Central administration of leptin inhibits food intake and activates the sympathetic nervous system in rhesus macaques. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, Cheetham CH, Earley AR, Barnett AH, Prins JB, O’Rahilly S 1997 Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 387:903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Considine EL, Williams CJ, Nyce MR, Magosin SA, Bauer TL, Rosato EL, Colberg J, Caro JF 1995 Evidence against either a premature stop codon or the absence of obese gene mRNA in human obesity. J Clin Invest 95:2986–2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Considine EL, Williams CJ, Hyde TM, Caro JF 1996 The hypothalamic leptin receptor in humans: identification of incidental sequence polymorphisms and absence of the db/db mouse and fa/fa rat mutations. Diabetes 19:992–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement K, Vaisse C, Lahlou N, Cabrol S, Pelloux V, Cassuto D, Gourmelen M, Dina C, Chambaz J, Lacorte JM, Basdevant A, Bourneres P, Lebouc Y, Froguel P, Guy-Grand B 1998 A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature 392:398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoda T, Manning BS, Goldstone AP, Imrie H, Evans AL, Strosberg AD, McKeigue PM, Scott J, Aitman TJ 1997 Leptin receptor gene variation and obesity: lack of association in a white British male population. Hum Mol Genet 6:869–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka N, Ogawa Y, Hosoda K, Matsuda J, Masuzaki T, Azuma N, Miyawaki T, Natsui K, Nishimura H, Yoshimasa Y, Nishi S, Thompson DB, Nakao K 1997 Human leptin receptor gene in obese Japanese subjects: evidence against either obesity-causing mutations or association of sequence variants with obesity. Diabetologia 40:1204–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, Caro JF 1996 Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 334:292–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymsfield SB, Greenberg AS, Fujioka K, Dixon RM, Kushner R, Hunt T, Lubina JA, Patane J, Self B, Hunt P, McCamish M 1999 Recombinant leptin for weight loss in obese and lean adults: a randomized, controlled, dose-escalation trial. JAMA 282:1568–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heek M, Compton DS, France CF, Tedesco RP, Fawzi AB, Graziano MP, Sybertz EJ, Strader CD, Davis Jr HR 1997 Diet-induced obese mice develop peripheral, but not central, resistance to leptin. J Clin Invest 99: 385–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro JF, Kolaczynski JW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Opentanova I, Goldman WH, Lynn RB, Zhang PL, Sinha MK, Considine RV 1996 Decreased cerebrospinal-fluid/serum leptin ratio in obesity: a possible mechanism for leptin resistance. Lancet 348:159–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Peskind E, Raskind M, Boyko EJ, Porte Jr D 1996 Cerebrospinal fluid leptin levels: relationship to plasma levels and to adiposity in humans. Nat Med 2: 589–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA 2001 Leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier: implications for the cause and treatment of obesity. Curr Pharm Des 7:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson PS, Upton R, Buckingham R, Arch J, Williams G 1997 Inhibition of food response to intracerebroventricular injection of leptin is attenuated in rats with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 46:1782–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell 2002 Reduced central leptin sensitivity in rats with diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283:R941–R948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Thomas TC, Storlien LH, Huang XF 2000 Development of high fat diet-induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57Bl/6J mice. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24:639–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A, Nguyen L, O’Doherty RM 2002 Nutritional regulation of hypothalamic leptin receptor gene expression is defective in diet-induced obesity. J Neuroendocrinol [Erratum (2003) 15:104] 14:887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Haschimi K, Pierroz DD, Hileman SM, Bjorbaek C, Flier JS 2000 Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest 105:1827–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Banks WA 2004 Obesity-prone rats have normal blood-brain barrier transport but defective central leptin signaling before obesity onset. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R143–R150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorbaek C, lavery HJ, Bates SH, Olson RK, Davis SM, Flier JS, Myers Jr MG 2000 SOCS3 mediates feedback inhibition of the leptin receptor via Tyr985. J Biol Chem 275:40649–40657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs DL, Hilton DJ 2000 SOCS: physiological suppressors of cytokine signaling. J Cell Sci 113 (Pt 16):2813–2819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzberg H, Flier JS, Bjorbaek C 2004 Region-specific leptin resistance within the hypothalamus of diet-induced obese mice. Endocrinology 145:4880–4889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TL, Alquier T, Asakura K, Furukawa N, Preitner F, Kahn BB 2006 Diet-induced obesity alters AMP-kinase activity in hypothalamus and skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 281:18933–18941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao AZ, Huan J-N, Gupta S, Pal R, Sahu A 2002 A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase phosphodiesterase 3B-cyclic AMP pathway in hypothalamic action of leptin on feeding. Nat Neurosci 5:727–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender KD, Morton GJ, Stearns WH, Rhodes CJ, Myers Jr MG, Schwartz MW 2001 Intracellular signalling. Key enzyme in leptin-induced anorexia. Nature 413:794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Clegg DJ, Olson R, Baskin DG, Myers Jr MG, Seeley RJ, Schwartz MW 2003 Insulin activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key mediator of insulin-induced anorexia. Diabetes 52:227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Takeda K, Akira S, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS 2005 PI3K integrates the action of insulin and leptin on hypothalamic neurons. J Clin Invest 115:951–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CD, Morton GJ, Niswender KD, Gelling RW, Schwartz MW 2005 Leptin inhibits hypothalamic Npy and Agrp gene expression via a mechanism that requires phosphatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289:E1051–E1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirshamsi S, Laidlaw HA, Ning K, Anderson E, Burgess LA, Gray A, Sutherland C, Ashford ML 2004 Leptin and insulin stimulation of signalling pathways in arcuate nucleus neurones: PI3K dependent actin reorganization and KATP channel activation. BMC Neurosci 5:54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Pak YK, Jang PG, Namkoong C, Choi YS, Won JC, Kim KS, Kim SW, Kim HS, Park JY, Kim YB, Lee KU 2006 Role of hypothalamic Foxo1 in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 9:901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Feng Y, Kitamura YI, Chua Jr SC, Xu AW, Barsh GS, Rossetti L, Accili D 2006 Forkhead protein FoxO1 mediates Agrp-dependent effects of leptin on food intake. Nat Med 12:534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederich RC, Hamann A, Anderson S, Lollmann B, Lowell BB, Flier JS 1995 Leptin levels reflect body lipid content in mice: evidence for diet-induced resistance to leptin action. Nat Med 1:1311–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnudi L, Tozzo E, Shepherd PR, Bliss JL, Kahn BB 1995 High level overexpression of glucose transporter-4 driven by an adipose-specific promoter is maintained in transgenic mice on a high fat diet, but does not prevent impaired glucose tolerance. Endocrinology 136:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen DR, Schlaepfer IR, Morin CL, Pennington DS, Marcell T, Ammon SM, Gutierrez-Hartmann A, Eckel RH 1997 Prevention of diet-induced obesity in transgenic mice overexpressing skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase. Am J Physiol 273(2 Pt 2):R683–R689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Tritos NA, Mastaitis JW, Kulkarni R, Kokkotou E, Elmquist J, Lowell B, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E 2001 Melanin-concentrating hormone overexpression in transgenic mice leads to obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 107:379–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua Jr SC, Elmquist JK 2004 Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42:983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Jr MG, Sun XJ, Cheatham B, Jachna BR, Glasheen EM, Backer JM, White MF 1993 IRS-1 is a common element in insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I signaling to the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Endocrinology 132:1421–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A, Metlakunta AS 2005 Hypothalamic phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-phosphodiesterase 3B-cyclic AMP pathway of leptin signalling is impaired following chronic central leptin infusion. J Neuroendocrinol 17:720–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ 2004 The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte Jr D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG 2000 Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404:661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A 2003 Leptin signaling in the hypothalamus: emphasis on energy homeostasis and leptin resistance. Front Neuroendocrinol 24:225–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A 2004 Minireview: a hypothalamic role in energy balance with special emphasis on leptin. Endocrinology 145:2613–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, Schubert M, Tso AW, Wang Y, Banks AS, Lavery HJ, Haq AK, Maratos-Flier E, Neel BG, Schwartz MW, Myers Jr MG 2003 STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 421:856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Wolfgang MJ, Neschen S, Morino K, Horvath TL, Shulman GI, Fu XY 2004 Disruption of neural signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 causes obesity, diabetes, infertility, and thermal dysregulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4661–4666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriori PJ, Evans AE, Sinnayah P, Jobst EE, Tonelli-Lemos L, Billes SK, Glavas MM, Grayson BE, Perello M, Nillni EA, Grove KL, Cowley MA 2007 Diet-induced obesity causes severe but reversible leptin resistance in arcuate melanocortin neurons. Cell Metab 5:181–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A, Metlakunta AR, Sahu M 2006 Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 interacts with the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus. 36th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, Atlanta, GA, October 14–18, 2006. Program No. 60.10. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience, 2006. Online (www.sfn.org) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Scarpace PJ 2006 The role of leptin in leptin resistance and obesity. Physiol Behav 88:249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabolotny JM, Bence-Hanulec KK, Stricker-Krongrad A, Haj F, Wang Y, Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Elmquist JK, Tartaglia LA, Kahn BB, Neel BG 2002 PTP1B regulates leptin signal transduction in vivo. Dev Cell 2:489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Uetani N, Simoncic PD, Chaubey VP, Lee-Loy A, McGlade CJ, Kennedy BP, Tremblay ML 2002 Attenuation of leptin action and regulation of obesity by protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Dev Cell 2:497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori H, Hanada R, Hanada T, Aki D, Mashima R, Nishinakamura H, Torisu T, Chien KR, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A 2004 Socs3 deficiency in the brain elevates leptin sensitivity and confers resistance to diet-induced obesity. Nat Med 10:739–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JK, Cave BJ, Oksanen LJ, Tzameli I, Bjorbaek C, Flier JS 2004 Enhanced leptin sensitivity and attenuation of diet-induced obesity in mice with haploinsufficiency of Socs3. Nat Med 10:734–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elchebly M, Payette P, Michaliszyn E, Cromlish W, Collins S, Loy AL, Normandin D, Cheng A, Himms-Hagen J, Chan CC, Ramachandran C, Gresser MJ, Tremblay ML, Kennedy BP 1999 Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B gene. Science 283:1544–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaman LD, Boss O, Peroni OD, Kim JK, Martino JL, Zabolotny JM, Moghal N, Lubkin M, Kim YB, Sharpe AH, Stricker-Krongrad A, Shulman GI, Neel BG, Kahn BB 2000 Increased energy expenditure, decreased adiposity, and tissue-specific insulin sensitivity in protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 20:5479–5489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A 2002 Resistance to the satiety action of leptin following chronic central leptin infusion is associated with the development of leptin resistance in neuropeptide Y neurones. J Neuroendocrinol 14:796–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Sahu A 2003 Leptin signaling in the hypothalamus during chronic central leptin infusion. Endocrinology 144:3789–3798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Sahu T A chronic central leptin infusion results in the development of leptin resistance in proopiomelanocortin and neurotensin neurons in the hypothalamus. Program of the 85th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, Philadelphia, PA, 2003 (Abstract P1-255) [Google Scholar]