Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) coupled to activation of Gs, such as the PTH1 receptor (PTH1R), have long been known to regulate skeletal function and homeostasis. However, the role of GPCRs coupled to other G proteins such as Gi is not well established. We used the tet-off system to regulate the expression of an activated Gi-coupled GPCR (Ro1) in osteoblasts in vivo. Skeletal phenotypes were assessed in mice expressing Ro1 from conception, from late stages of embryogenesis, and after weaning. Long bones were assessed histologically and by microcomputed tomography. Expression of Ro1 from conception resulted in neonatal lethality that was associated with reduced bone mineralization. Expression of Ro1 starting at late embryogenesis resulted in a severe trabecular bone deficit at 12 wk of age (>51% reduction in trabecular bone volume fraction in the proximal tibia compared with sex-matched control littermates; n = 11; P < 0.01). Ro1 expression for 8 wk beginning at 4 wk of age resulted in a more than 20% reduction in trabecular bone volume fraction compared with sex-matched control littermates (n = 16; P < 0.01). Bone histomorphometry revealed that Ro1 expression is associated with reduced rates of bone formation and mineral apposition without a significant change in osteoblast or osteoclast surface. Our results indicate that signaling by a Gi-coupled GPCR in osteoblasts leads to osteopenia resulting from a reduction in trabecular bone formation. The severity of the phenotype is related to the timing and duration of Ro1 expression during growth and development. The skeletal phenotype in Ro1 mice bears some similarity to that produced by knockout of Gs-α expression in osteoblasts and thus may be due at least in part to Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase.

SIGNALING BY G PROTEIN-coupled receptors (GPCRs) plays a crucial role in regulating the functional activity of osteoblasts, but the precise actions of specific G protein signaling pathways are incompletely understood. The best studied osteoblast GPCR, the PTH1 receptor (PTH1R), responds to PTH or PTHrP by activating two G proteins: Gs and Gq (1). In mice, osteoblast-specific knockout of functional Gs-α results in neonatal lethality associated with a reduction in trabecular bone formation and reduced endocortical bone resorption (2). This is congruent with reports that the ability to activate adenylyl cyclase (presumably via activation of Gs) is essential for the anabolic action of intermittent PTH in trabecular bone (3) and for the ability of continuous, high levels of PTH to promote osteoclastic bone resorption (4,5).

There is little available information on the role of osteoblast signaling by G proteins of the Gi class. GPCR-mediated activation of these G proteins is inhibited by pertussis toxin, and this agent is therefore frequently used as a tool to identify Gi-mediated effector responses. Interestingly, the in vitro actions of fluoride and strontium to promote proliferation of osteoblastic cells are inhibited by pertussis toxin (6,7). This suggests that the in vivo anabolic actions of these agents could, at least in part, be mediated by stimulation of Gi signaling. Activation of the Gi-coupled apelin receptor also stimulates osteoblast proliferation in vitro (8). Recently, deletion of the gene encoding the Gi-coupled CB2 cannabinoid receptor was shown to lead to high turnover osteoporosis (9). Consistent with these studies, activation of Gi-coupled GPCRs can signal to anabolic pathways such as MAPK in other cellular contexts (10). However, the classical effect of Gi activation is to inhibit the ability of Gs-coupled receptors to increase adenylyl cyclase activity, and this might be expected to oppose anabolic signaling in osteoblasts (3). Clearly, in vivo studies directly assessing the effects of Gi-coupled GPCR signaling in osteoblasts are needed.

Recently, a new approach to ascribing physiological consequences to specific G protein signaling pathways has been developed. In this approach, GPCRs that are specific to a single G protein pathway are mutated to eliminate the response to naturally occurring agonists while retaining responsiveness to synthetic agonists. These mutated GPCRs are termed receptors activated solely by synthetic ligands (RASSL). In principle, targeting expression of the RASSL to a cell type of interest in transgenic mice would allow examination of a specific G protein signal by administration of the synthetic agonist. The prototype RASSL that we used in the present study is a mutated version of the Gi-coupled κ-opioid receptor that responds to the synthetic agonist spiradoline (11). This RASSL (termed Ro1) has been previously used to assess the role of Gi-coupled GPCR signaling in cardiac myocytes by targeted expression under the control of the D α-myosin heavy chain promoter. In those studies, Ro1 signaling was shown to mediate spiradoline-induced bradycardia (12) as well as to produce a constitutive phenotype of lethal cardiomyopathy (13).

In the present study, we have generated mice expressing the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) under control of the mouse 2.3-α type 1 collagen promoter, allowing osteoblast-selective expression of Ro1 that can be readily suppressed by administration of the tetracycline analog doxycycline. This has allowed us to examine the skeletal effects of signaling by a Gi-linked GPCR in osteoblasts.

Materials and Methods

DNA construction and in vitro verification of transgene expression

The Col I-2.3-tTA plasmid was constructed by cloning the 2.3-kb mouse α1-type I collagen promoter (Col I-2.3) (14) (provided by Dr. Gerard Karsenty) in place of the pCMV promoter upstream of the tTA sequence in the plasmid pUHG 15-1 (15). Expression and functional doxycycline regulation was verified in vitro by cotransfecting ROS 17/2.8 rat osteosarcoma cells with the Col I-2.3-tTA plasmid and the plasmid pUHG 16-3 (12), which encodes a tet-off, tTA-driven, LacZ gene. Two days after transfection, cells were treated with or without doxycycline (2 ng/ml) for 48 h and then assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Galacto-Light Kit, catalog item BL300G; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Mice

Mice harboring the tetO-Ro1 transgene have been previously described (12). We have generated the transgenic mouse line that expresses the tTA under regulatory control of the mouse Col I-2.3. A purified Col I-2.3-tTA DNA fragment was prepared and used to microinject FVB/N oocytes. Injections were carried out at the Transgenic Core Facility of the UCSF-affiliated Gladstone Foundation, according to their standard methods. Founders expressing the transgene were identified by PCR from tail genomic DNA. After identification, they were sent to an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved Transgenic Mouse facility at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, and backcrossed with wild-type FVB/N mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained on either standard mouse chow or a diet containing 200 mg/kg doxycycline (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ; catalog item S3888). With the exception of the animals in the 5-d protocol described below, all animals were maintained on doxycycline diet until 4 wk of age, at which time they were switched to the standard mouse diet for 8 wk. All studies were approved by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Five-day protocol

Female tetO-Ro1 mice were maintained on doxycycline for 2 wk and subsequently introduced to male Col I-2.3-tTA(139) mice. Females were then checked daily for the presence of sperm plugs. Five days after the detection of a sperm plug, the females were taken off the doxycycline diet and maintained on regular mouse chow thereafter. Progeny were maintained on regular mouse chow.

Genotyping

Mouse tail genomic DNA was purified using REDExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The Col I-2.3-tTA transgene was identified using the primers 5′-CCA GCC ACA CTC CAG TGA-3′ and 5′-GTC GTA ATA ATG GCG GCA TA-3′, resulting in a 930-bp fragment. The presence of the Ro1 transgene was determined using the primers 5′-TGA TGA TGA TGT CGA CTC CC-3′ and 5′ GGC AAT GTA ACG GTC CAC-3′, producing a 487-bp fragment. Genomic and plasmid DNA positive controls were included with each PCR. PCR was performed with the following cycling profile: 94 C for 5 min; 16 cycles of 94 C for 45 sec, 65 C for 1 min, and 72 C for 1.5 min; 15 cycles of 94 C for 45 sec, 58 C for 1 min, and 72 C for 1.5 min; and 72 C for 7 min.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Tissue samples were isolated and kept frozen in liquid nitrogen until processing. Frozen tissues were pulverized using a bio-pulverizer (Biospec Products Inc., Bartlesville, OK), followed by RNA extraction using Micro-to-Midi Total RNA Purification Kit (catalog no. 12183-018; Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems; part no. N808-0234) and random hexamer primers, according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. SYBR Green-based (Applied Biosystems; part no. 4309155) gene amplification was measured using the ABI Prism 7900HT real-time thermocycler. Analysis was carried out using the SDS 2.0 and 2.1 software supplied with the machine. The sequences of the primer sets are as follows: 18S rRNA, 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ and 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′; Ro1, 5′-GTGGACCGTTACATTGCCGT-3′ and 5′-GATGCCAGTAGCCAAATGCA-3′. All reactions were performed in triplicate, and target gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA.

Microcomputed tomography (micro-CT)

Left tibias from 12-wk-old mice were isolated and cleaned of adherent tissue. Before micro-CT analysis, bones were defatted by sequential extraction in ethanol and diethyl ether using a Soxhlet apparatus and dried overnight at 90 C. The tibias were imaged using a Scanco Medical AG micro-CT apparatus as previously described (16). Imaging of trabecular bone was carried out at the proximal metaphysis of the tibia. Imaging of cortical bone was carried out at the tibio-fibular junction. Data are presented as mean ± sem. Statistical significance was determined using a paired t test between double transgenic animals and sex-matched littermate controls.

β-Galactosidase staining

Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 C until staining. Samples were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 2 h, followed by staining in LacZ staining solution [2 mm MgCl2, 0.01 sodium deoxycholate, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm EGTA, 5 mm K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mm K4Fe(CN)6, 1 mg/ml X-gal in PBS] for 4 h. Samples were then postfixed in PFA/glutaraldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin and sectioned following standard procedure, and counterstained with eosin.

Skeletal staining

Newborn pups were killed and fixed in 99% ethanol overnight after skin and intestines had been removed. Samples were transferred to acetone for 24 h and then stained in a solution of 0.015% Alcian blue/0.005% Alizarin red/5% acetic acid in ethanol at 37 C for 3 d. Samples were cleared with 1% KOH and stored in 80% glycerol in ethanol.

von Kossa staining

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and then stored in 70% ethanol until they were embedded in paraffin and sectioned under standard procedures. Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized and stained with 2% AgNO3 under UV for 45 min. The samples were then treated with 5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 min and counterstained in hematoxylin.

Serum chemistry

Blood samples were obtained from mice at the time of euthanasia, and serum was isolated from each sample by centrifugation for 15 min at 3000 rpm. Serum samples were stored at −20 C. Serum pyridinoline levels were determined using Metra PYD kit (Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Serum osteocalcin was measured using BTI’s Mouse Osteocalcin EIA Kit (Biomedical Tech. Inc., Stoughton, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative bone histomorphometry

Femurs from 12-wk-old mice were isolated at the time of death and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin overnight. After fixation, the femurs were dehydrated in graded ethanol and xylene and embedded in methylmethacrylate. Osteoblast and osteoclast surfaces in the distal femoral metaphysis were measured in von Kossa/tetrachrome-stained sections as previously described (17).

Dynamic histomorphometry

Mice were injected ip with 20 mg/kg calcein 7 d before euthanasia and 0.9 mg/g xylenol orange 2 d before being killed. Tibias were isolated and fixed overnight in 4% PFA followed by 30% sucrose perfusion for 3 d. Bone specimens were frozen in OCT embedding medium and sectioned at 5 μm using a Leica CM 1900 Cryostat (d-69226; Leica, Inc., Nussloch, Germany) with a CryoJane Frozen Sectioning Kit (Instrumedics, Hackensack, NJ) as previously described (18). Images at ×20 magnification were acquired with a Zeiss Axioplan 200 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY). Analyses were blinded and performed using image analysis software (Bioquant Image Analysis Corp., Nashville, TN) in the region 300 μm from the lowest point on the growth plate extending 1 mm down the metaphysis. Statistical significance was determined using a paired t test between double-transgenic animals and sex-matched littermate controls.

Bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) cultures

A previously described procedure (19) was used to isolate and culture BMSCs from 12-wk-old double-transgenic mice that had been maintained continuously on doxycycline to prevent expression of the Ro1 transgene in vivo. Cells were cultured either in the presence of 2 ng/ml doxycycline (sufficient to repress Ro1 expression in vitro) or in the absence of doxycycline to allow Ro1 expression. Osteoblast differentiation and function were assessed as described (19). The presence of doxycycline in the media had no effect on the differentiation or function of wild-type primary osteoblasts.

Results

Generation of mice with osteoblast-specific, tetracycline-regulated expression of the Gi coupled RASSL Ro1

To assess the effects of signaling by a Gi-coupled receptor in osteoblasts, we targeted the Gi-RASSL Ro1 to osteoblasts in transgenic mice. Previously, it was reported that prolonged expression of Ro1 in cardiac myocytes resulted in more than 90% mortality (13), suggesting that Ro1 exhibits basal signaling in the absence of the synthetic agonist. To circumvent possible developmental effects of Ro1 expression in osteoblasts, we used the tetracycline regulatory system to permit controlled expression of the Ro1 gene. In studies of the cardiac effects of Ro1, the tet-off system allowed tight regulation of gene expression in vivo by administration of doxycycline (12,20,21). Additionally, the tet-off system has been used to control transgene expression in osteoblasts, with no observed adverse effects of chronic administration of doxycycline (22). We generated four transgenic mouse lines in which the tTA is expressed under the mouse Col I-2.3 promoter, which has been demonstrated to be expressed selectively in osteoblasts and osteocytes (14,23).

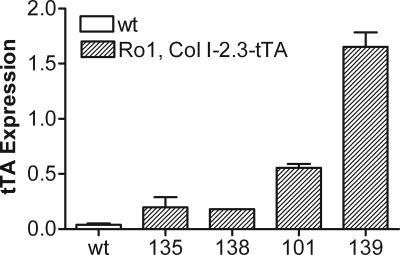

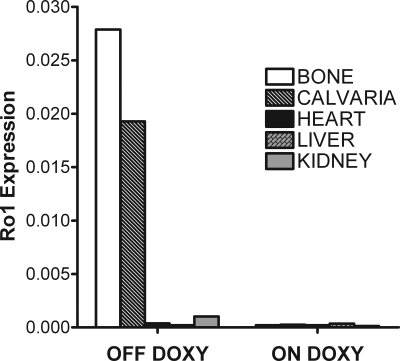

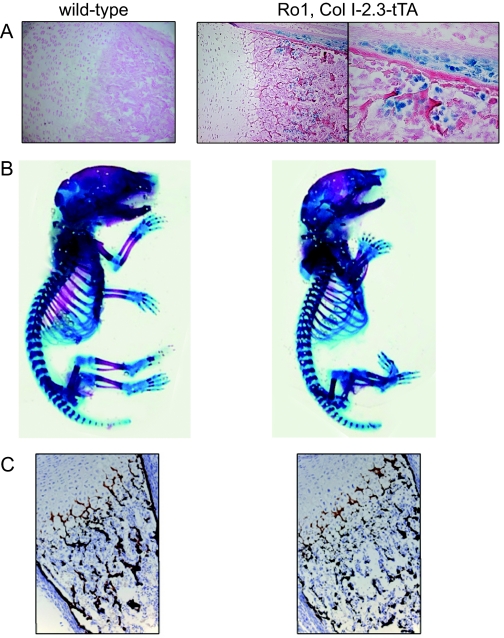

The transgenic mouse lines expressed the tTA gene at various levels, with the highest expression seen in line 139 and the next highest in line 101 (Fig. 1). The lines with the highest tTA expression, 139 and 101, were then crossed with mice harboring a tTA-responsive Ro1 gene. Quantitative PCR analysis of RNA isolated from various tissues from 2-wk-old Ro1, Col I-2.3-tTA(101) reveal that bone-specific expression of Ro1 was achieved as well as successful regulation with doxycycline administration (Fig. 2). In animals maintained off doxycycline, expression of Ro1 is limited to long bones and calvariae, whereas Ro1 expression was almost completely suppressed in mice maintained on a diet that contained doxycycline. The tetO-Ro1 mice harbor a cointegrated tetO-LacZ gene, allowing for enzymatic assay of β-galactosidase in double transgenic mice to determine presumed sites of Ro1 expression (Fig. 3A). As expected, the Col I-2.3 promoter is active selectively in osteoblasts and osteocytes within the tibia in vivo.

Figure 1.

Relative tTA expression in Col I-2.3-tTA founder strains. RNA was isolated from the long bones of 2-wk-old Col I-2.3-tTA mice from each founder strain. The highest levels of tTA expression were observed in lines 139 and 101. Data were obtained by quantitative PCR analysis and are normalized to 18S rRNA. wt, Wild type.

Figure 2.

Tissue specificity of the expression of the Ro1 gene in double-transgenic mice. RNA was isolated from the tissues indicated derived from 2-wk-old Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(101) mice continuously maintained off doxycycline (left) or on doxycycline (right). Data were obtained by quantitative PCR analysis and are normalized to 18S rRNA.

Figure 3.

Skeletal features in Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA mice. A, β-Galactosidase activity in the proximal tibia of a wild-type and Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA mouse maintained in the absence of doxycycline. The latter strain harbors a cointegrated tTA-driven LacZ gene for identification of sites of promoter activity. An additional higher-magnification image is shown of staining in the Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA tibia. B, Alizarin red/alcian blue staining of a newborn Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) mouse (off doxycycline) compared with a wild-type littermate. Note the reduced skeletal mineralization in the double-transgenic mouse, especially evident in the ribs and vertebrae. Newborn double-transgenic mice also display altered craniofacial morphology. C, von Kossa-stained section of the distal femur of a newborn Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) mouse (off doxycycline) compared with that of a wild-type littermate. Newborn double-transgenic mice have reduced trabecular bone mineralization compared with wild-type. The growth plate appears to be grossly normal.

Neonatal lethality

Initial experiments were carried out without the use of doxycycline, allowing expression of the transgene in double-transgenic mice throughout development. The most striking result is the paucity of viable double-transgenic mice at weaning in Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA crosses maintained without doxycycline (Table 1). Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) yielded zero (of 203 total mice) viable double-transgenic mice, whereas Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(101) crosses yielded only nine (of 127 total mice, 7.1%) surviving double-transgenic mice. Surviving double-transgenic mice were runted, with body weights approximately 50% that of their sex-matched littermate controls at weaning (data not shown).

Table 1.

Yield of double-transgenic mice from crosses of Ro1 and two lines of Col I 2.3-tTA

| Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139)

|

Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(101)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off doxy, n = 80 (%) | On doxy, n = 280 (%) | Off doxy, n = 119 (%) | On doxy, n = 100 (%) | |

| Wild-type | 40.0 | 25.9 | 31.9 | 24.0 |

| Ro1 | 26.3 | 24.8 | 30.3 | 34.0 |

| Col I-2.3-tTA | 33.8 | 22.7 | 31.1 | 14.0 |

| Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA | 0.0 | 26.6 | 6.7 | 28.0 |

Ro1 mice were crossed with Col I-.3-tTA lines 139 and 101. The pups and their mothers were either never exposed to doxycycline (doxy) or maintained continuously on doxycycline from time of conception.

We have examined mouse embryos from Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) crosses from embryonic d 11–14. Normal-appearing double-transgenic embryos were present at roughly the expected Mendelian ratio, indicating that the lethality occurs later in embryogenesis or perinatally. Examination of newborn mice revealed that Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) pups appear grossly normal at birth but die within 2 h due to apparent respiratory failure. Alizarin red/Alcian blue staining of newborn Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) mice reveals a moderate reduction in mineralized bone, especially evident in the ribs and vertebrae, as well as subtle alterations in the structure of craniofacial bones (Fig. 3B). Histological studies of the proximal tibia confirm a reduction in trabecular bone (Fig. 3C). No abnormalities were evident in single-transgenic mice harboring only the Col I-2.3-tTA or tetO-Ro1 transgene (data not shown).

Inducibility of Ro1

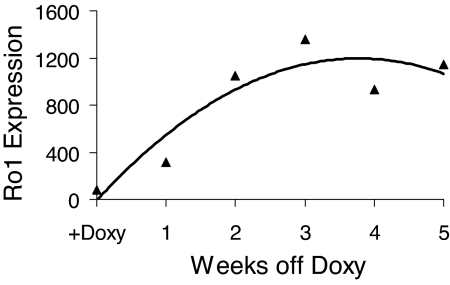

We next assessed the inducibility of Ro1 expression in double-transgenic mice that had been maintained on doxycycline from conception to the time of weaning (4 wk of age). Withdrawal of doxycycline at 4 wk of age resulted in progressive expression of Ro1 in bone. Ro1 expression was readily detected after 1 wk and was maximal after 2 wk after withdrawal from doxycycline (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Induction of Ro1 gene expression upon withdrawal of doxycycline from the diet of Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) double-transgenic mice. Expression of Ro1 was assessed in RNA isolated from the long bones of double-transgenic mice that were maintained continuously on doxycycline until 4 wk of age and then switched to doxycycline-free chow for the times indicated. Data are derived from quantitative PCR analysis and are normalized to 18S rRNA.

Skeletal effects of induced expression of Ro1

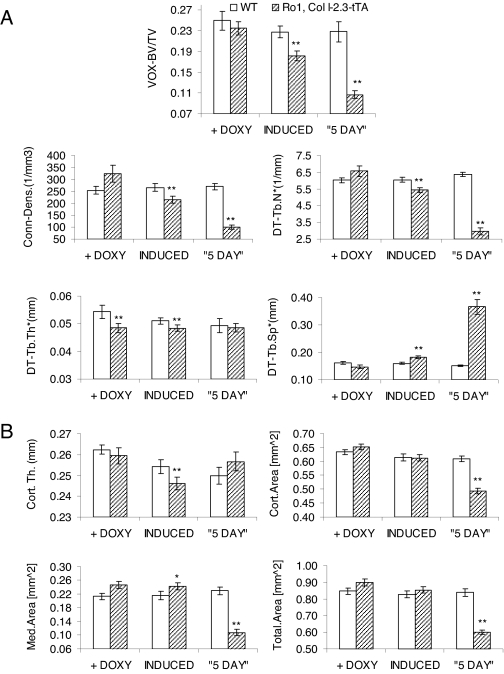

Progeny of Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA(139) mice were maintained on doxycycline from conception until 4 wk of age at which time they were switched to a doxycycline-free diet. Eight weeks later, mice were killed, and micro-CT studies were carried out on the tibias of control and double-transgenic mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, induced expression of Ro1 for 8 wk resulted in a more than 20% reduction in trabecular bone volume compared with sex-matched littermate controls. This was associated with decreased trabecular connectivity, decreased trabecular number, and increased trabecular separation. None of these changes were evident in double-transgenic mice maintained continuously on doxycycline. A small decrease in trabecular thickness was also evident, but this was also seen in double-transgenic mice maintained continuously on doxycycline, and its significance is therefore uncertain. A small reduction in the thickness of cortical bone in the tibial diaphysis was also seen (Fig. 5B). None of these effects was seen in double-transgenic mice maintained continuously on doxycycline. The results indicate that 8 wk of induced expression of Ro1 produces a significant decrease in the amount and quality of trabecular bone.

Figure 5.

Effect of osteoblast expression of Ro1 on the skeleton, assessed by micro-CT of the tibia. Three groups of Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA mice were studied. The first group was maintained continuously on doxycycline (+ DOXY, n = 16). The second group was maintained on doxycycline until 4 wk of age and then withdrawn from doxycycline (INDUCED, n = 16). The third group had osteoblast expression of Ro1 continuously from birth using the 5-d protocol described in Materials and Methods (“5 DAY”, n = 11). All mice were killed at 12 wk of age and the tibias harvested for micro-CT analysis. In each case, the results with double-transgenic mice are compared with results obtained with sex-matched wild-type (WT) littermates maintained on the same regimen of doxycycline. Asterisks indicate a significant increase or decrease in the parameter relative to the value in the corresponding wild-type group: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. A, The proximal tibias were used for assessment of the following parameters of trabecular bone: bone volume fraction (VOX-BV/TV); connectivity density (Conn-Dens.); trabecular number (DT-Tb.N*); trabecular spacing (DT-Tb.Sp*); and trabecular thickness (DT-Tb.Th*); B, parameters of cortical bone were assessed from the tibial diaphysis: cortical thickness (Cort.Th.) and cross-sectional area analyses (Cort. Area, Med.Area, and Total.Area).

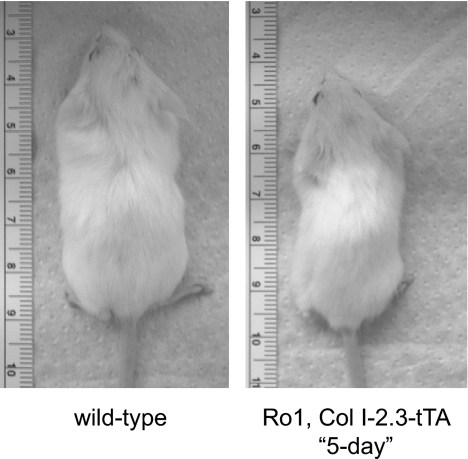

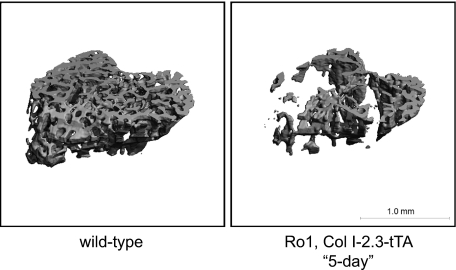

To assess the phenotype of mice in which Ro1 expression was initiated earlier in the course of development, we established an approach to rescue the Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA mice from neonatal lethality. In this approach, we administered the doxycycline-containing diet to the pregnant mother for the first 5 d of pregnancy and then removed doxycycline from the diet. Due to the time required to clear doxycycline from the system, we would expect this method to result in the suppression of Ro1 for most of gestation. The pups were then maintained on a doxycycline-free diet until the time of euthanasia. Under this protocol (5-d protocol), the double-transgenic mice were viable although consistently runted, with body weights less than half those of their sex-matched wild-type littermates at weaning, similar to the double-transgenic mice of the 101 line (Fig. 6). Mice that were allowed to express Ro1 throughout development via the 5-d protocol showed osteopenia of greater severity than double transgenic mice maintained on doxycycline until weaning, with a 51% reduction in trabecular bone volume. These mice displayed a dramatic decrease in trabecular connectivity and number and increased trabecular spacing (Fig. 5A). Reconstruction of the micro-CT images highlights the striking loss of trabecular number and connectivity in mice expressing the Ro1 gene throughout postnatal life (Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

Effects of continuous Ro1 expression on body size. Animals allowed to express Ro1 from birth, 5-d protocol, were consistently runted with body weights at only half of their wild-type littermates.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional micro-CT renderings of tibias from control vs. Ro1 × Col I-2.3tTA(139) mice on the 5-d protocol. Representative images were selected from animals whose micro-CT parameters were closest to the mean for their representative group.

Dynamic and static histomorphometric measurements were taken on the bones of double-transgenic animals to assess the effects of induced Ro1 expression on parameters of bone function. Dynamic histomorphometric measurements were taken at the metaphysis of the proximal tibias of double-transgenic mice at 8 wk of age, 4 wk after withdrawal of doxycycline (Table 2). Both male and female mice expressing Ro1 displayed a significant reduction in bone formation rate and mineral apposition rate compared with sex-matched littermate controls. Static histomorphometric measurements were taken at the metaphysis of the distal femurs and revealed no significant differences in osteoblast and osteoclast surfaces between double-transgenic mice and sex-matched littermate controls.

Table 2.

Bone histomorphometric measurements in Ro1-expressing mice and littermate controls

| Mice | Ob.S/BS (%) | Oc.S/BS (%) | MS/BS (%) | MAR (mcm/d) | BFR (mcm/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Littermate controls, male | 4.60 ± 0.96 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 73.77 ± 3.43 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 36.46 ± 1.44 |

| Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA, male | 4.49 ± 0.71 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 67.08 ± 6.28 | 0.35 ± 0.04a | 23.98 ± 3.83a |

| Littermate controls, female | 18.68 ± 2.15 | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 82.65 ± 2.41 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 44.32 ± 4.57 |

| Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA, female | 15.37 ± 1.54 | 0.89 ± 0.18 | 75.27 ± 2.47a | 0.426 ± 0.04a | 31.88 ± 2.47a |

Ro1 expression was induced by doxycycline withdrawal at 4 wk of age. Analyses of osteoblast surface (Ob.S/BS) and osteoclast surface (Oc.S/BS) were performed in the distal femur of 12-wk-old mice, male (n = 13) and female (n = 14). Measurements of percent mineralizing surface (MS/BS), mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bone formation rate (BFR) were performed on tibias of 8-wk-old mice, male (n = 4) and female (n = 8). Mice were withdrawn from doxycycline at 4 wk of age.

Significant increase or decrease in the parameter relative to the value in the corresponding littermate control group (P < 0.05).

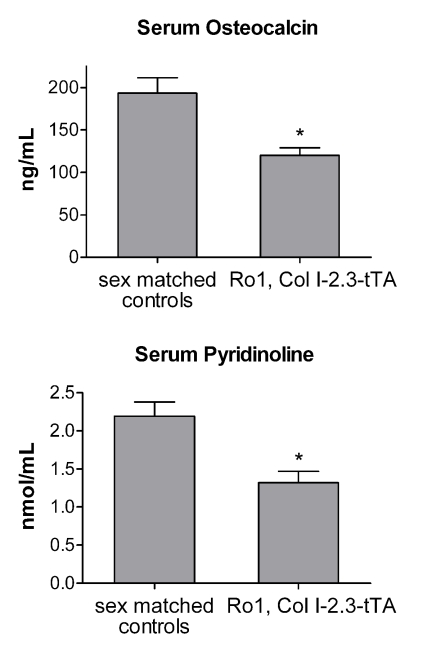

Serum markers of bone formation and resorption were also examined in 8-wk-old double-transgenic animals expressing Ro1 (Fig. 8). Serum osteocalcin, a marker of bone formation, was significantly reduced in Ro1-expressing animals compared with sex-matched littermate controls. Expression of Ro1 also resulted in a decrease in serum pyridinoline, a marker of bone resorption.

Figure 8.

Effects of Ro1 on serum markers of bone formation and resorption. Serum osteocalcin, a marker for bone formation, was significantly reduced in 8-wk-old Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA mice allowed to express Ro1 for 4 wk (n = 12; P < 0.05). Serum pyridinoline, a marker for bone resorption, was also reduced in these mice (n = 12; P < 0.05). Results from double-transgenic animals were compared with results from sex-matched wild-type littermates and significance determined using a paired t test.

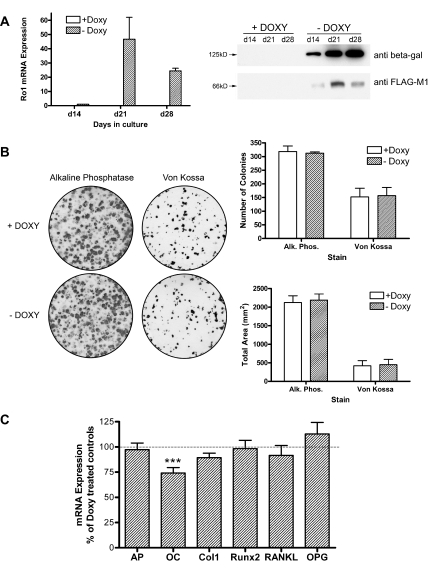

To determine whether the inhibitory effect of Ro1 on osteoblast function was demonstrable outside of the bone microenvironment, we cultured BMSCs from double-transgenic mice that had been maintained continuously on doxycycline to prevent the expression of Ro1. BMSCs were cultured for up to 28 d in either the presence or absence of 2 ng/ml doxycycline. The results in Fig. 9 demonstrate that cells grown in the absence of doxycycline expressed readily detectable amounts of Ro1 at the mRNA and protein level, whereas little or no Ro1 was detected in cells grown in the presence of doxycycline. Expression of Ro1 in osteoblasts had no effect on the size or number of osteogenic colonies, assessed either by alkaline phosphatase or by von Kossa staining. A variety of osteoblast marker genes in 21-d cultures were likewise unaffected by expression of Ro1, with the exception of the osteocalcin gene, which was modestly suppressed.

Figure 9.

Effects of Ro1 expression on primary bone marrow stromal cell cultures. Stromal cells harvested from transgenic animals maintained on a doxycycline diet were cultured in vitro with (+) and without (−) doxycline (Doxy). A, Ro1 mRNA and protein expression were examined in 14-, 21-, and 28-d-old cultures. In the absence of doxycycline, Ro1 RNA and FLAG-tagged Ro1 protein expression was evident at d 14 and greatly increased at the latter time points. β-Galactosidase protein expression was similarly doxycycline regulatable. Quantitative PCR data were normalized to GAPDH and referenced to d-14 expression levels (n = 4). A typical Western blot, for which protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining, is shown. B, Cultures were stained for alkaline phosphatase (Alk. Phos.) activity at d 14 or the extent of mineralization assessed by von Kossa staining at d 21. Quantification confirmed that the absence of doxycycline did not alter the number of stain-positive colonies or the total stained area for either alkaline phosphatase (n = 4) or von Kossa (n = 8). C, The gene expression profile of markers of osteoblast identity and function was determined in 21-d-old cultures. The absence of doxycycline resulted in a 25% decrease in the expression of osteocalcin (OC; P < 0.001; n = 7), without significant changes in expression of alkaline phosphatase (AP; n = 7), collagen type I (Col1; n = 7), Runx2 (n = 4), RANKL (n = 4), or osteoprotegerin (OPG; n = 4). Data were obtained by quantitative PCR analysis and normalized to GAPDH before calculating marker gene expression in the absence of doxycycline as a percentage of doxycycline-treated controls.

Discussion

The overall goal of the present study was to gain insight into the biological effects of Gi-coupled GPCR signaling in osteoblasts. We targeted expression of the Gi-activating RASSL, Ro1, to osteoblasts using the tet-off system under the control of mouse 2.3-kb Col I promoter. quantitative PCR analysis of Ro1 expression demonstrated skeletal expression that was efficiently suppressed by the administration of doxycycline in the diet. Because the tetO-Ro1 mice possess a cointegrated tetO-LacZ gene, staining for β-galactosidase activity was used to confirm an osteoblast-specific pattern of expression in the bones of the double-transgenic mice. Our results indicate that the tet-off system is very well suited for the control of transgene expression in osteoblasts in vivo.

Unregulated expression of Ro1 in osteoblasts during embryogenesis produced deficient bone mineralization and early postnatal lethality. Unregulated expression of Ro1 driven by very high levels of tTA (mouse line 139) always produced lethality, whereas unregulated expression of Ro1 driven by lower levels of tTA (mouse line 101) occasionally resulted in surviving double-transgenic mice presumably due to a lower level of expression of the Ro1 transgene. Double-transgenic pups appeared to die of respiratory failure within 2 h of birth, but the precise cause of postnatal death is uncertain. The mice displayed a generalized reduction in bone mineralization, and this was confirmed by von Kossa staining of the tibias. Under-mineralization of the rib cage may have contributed to lethal respiratory failure.

As expected, lethality in Ro1 × Col I-2.3-tTA double-transgenic pups was rescued by administration of doxycycline to the mother throughout gestation. If the expression of Ro1 was delayed until after weaning, the double-transgenic mice expressing Ro1 for 8 wk exhibited osteopenia, with a considerable reduction in trabecular bone volume. Micro-CT analysis of tibias from animals expressing Ro1 in osteoblasts from birth (5-d protocol) revealed a similar effect of Ro1 on trabecular bone, but the osteopenia was much more severe. Dynamic histomorphometric analysis of Ro1-expressing mice revealed a significant reduction in parameters of trabecular bone formation, suggesting that the reduction in their trabecular bone volume can be attributed to a decrease in bone formation. Lower levels of serum osteocalcin in these mice confirm the finding that Ro1 expression results in a decrease in bone formation. Osteoclast surfaces were not affected by Ro1 expression, whereas bone resorption was decreased as assessed by serum pyridinoline levels. These results demonstrate that the primary cause of trabecular osteopenia produced by Gi-linked GPCR signaling in osteoblasts is decreased bone formation. Interestingly, expression of Ro1 produced little apparent effect on cortical bone. Cortical area was unaffected in mice with induced expression of Ro1, whereas cortical area was reduced in double-transgenic mice on the 5-d protocol presumably due to the generalized growth defect that was present.

We were surprised to find that expression of Ro1 in cultured BMSCs had little or no effect on the expression of osteoblast differentiation markers or the ability of the cells to produce a mineralized matrix. One possible explanation could be a requirement for something in the skeletal milieu in vivo to enhance the expression or signaling by Ro1. However, Ro1 appears to be well expressed in differentiated BMSCs in vitro. Moreover, Ro1 is not known to respond to any endogenous ligands, and thus it is not clear how the in vivo milieu could enhance signaling by Ro1. It is conceivable that the functional activity of Ro1 is manifest only in osteoblasts with activated Gs signaling. Such activation might be occurring in vivo but not in BMSCs in vitro. Another possible explanation is that the effects of Ro1 expression in maturing osteoblasts in vivo might be indirect. Differentiated cells in the osteoblast lineage are known to express paracrine factors that can influence the differentiation of early osteoblasts. Two examples are dickkopf-1 and sclerostin, both secreted inhibitors of canonical wnt signaling. It is possible that Ro1 signaling promotes the expression of these (or other) antiosteogenic factors, resulting in suppression of early osteoblast differentiation. It would be difficult to document such an antiosteogenic effect in culture in our in vitro studies because Ro1 expression does not occur until the BMSCs have undergone substantial maturation (allowing the 2.3-kb Col I promoter to become active) at which time few early osteoblasts are present.

The classical effect of Gi signaling is to antagonize adenylyl cyclase activation produced by Gs-coupled GPCRs (24). Indeed, the skeletal phenotype of Ro1-expressing mice in the present study resembles in some respects the phenotype of mice with osteoblast-specific ablation of expression of the Gs-α gene (2). Thus, mice lacking Gs-α in osteoblasts displayed marked osteopenia that was restricted to the trabecular compartment. Cortical thickness was increased, presumably due to the loss of the osteoclastogenic action of Gs/adenylyl cyclase signaling in osteoblasts. In the present study, mice expressing Ro1 also displayed significant loss of trabecular bone. In addition, bone resorption was suppressed as evidenced by reduced serum levels of pyridinoline, although little change in cortical bone was evident. It is possible that effects on cortical bone require a more severe dampening of Gs/adenylyl cyclase than that resulting from Ro1 expression. Indeed, constitutive Gi signaling by Ro1 appears to be weak, because we were unable to detect significant inhibition of Gs-dependent adenylyl cyclase by Ro1 either in BMSCs or in 293 cells transfected with Ro1 (data not shown). This was not surprising, because it is often difficult to document weak constitutive signaling by Gi-coupled receptors. Taken together, the results suggest that the phenotypic effects of Ro1 do not require strong inhibition of the adenylyl cyclase pathway in osteoblasts. Whether signaling pathways other than Gi contribute to the phenotypic effects of Ro1 remains an open and important question.

Previous results have suggested that endogenous Gs/adenylyl cyclase signaling in cells of the osteoblast lineage can serve to promote skeletal anabolism. The upstream components of this putative endogenous anabolic pathway are uncertain but may involve PTHrP-dependent activation of the PTHR. This is supported by the observation that the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH is at least in part due to PTHR-mediated activation of Gs/adenylyl cyclase (25). Moreover, ablation of PTHrP expression by osteoblasts results in trabecular osteopenia (26). Finally, constitutively active PTHRs targeted to osteoblasts produce an increase in trabecular bone and a decrease in cortical bone (27), whereas generalized deletion of the PTHR produces neonatal lethality and a reduction in trabecular bone formation (28). The present results indicate that Gi-GPCR signaling in osteoblasts can produce inhibitory effects on bone formation. The balance between Gs and Gi signaling in cells of the osteoblast lineage appears to be one important determinant of skeletal anabolism in vivo.

In summary, the present results demonstrate the utility of RASSL technology for investigating the effects of Gi-coupled GPCR signaling in osteoblasts. The recent development of RASSLs for Gs and Gq will permit studies on the skeletal effects of additional G protein signaling pathways in osteoblasts (29,30,31).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. David Rowe and his laboratory staff for their technical assistance in this work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK072071 (to R.A.N.) and HL60664 (to B.R.C.); by VA Merit Review awards (to R.A.N. and B.H.); and by a VA REAP Award (Dr. D. Bikle, PI). R.A.N. and B.H. are recipients of Senior Research Scientist Awards from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 29, 2007

Abbreviations: BMSC, Bone marrow stromal cell; Col I-2.3, 2.3-kb mouse α1-type I collagen promoter; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; micro-CT, microcomputed tomography; PFA, paraformaldehyde; PTH1R, PTH1 receptor; RASSL, receptors activated solely by synthetic ligands; tTA, tetracycline transactivator.

References

- Gensure RC, Gardella TJ, Juppner H 2005 Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide, and their receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328:666–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto A, Chen M, Nakamura T, Xie T, Karsenty G, Weinstein LS 2005 Deficiency of the G-protein α-subunit Gsα in osteoblasts leads to differential effects on trabecular and cortical bone. J Biol Chem 280:21369–21375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley P, Whitfield JF, Willick GE 1999 Design and applications of parathyroid hormone analogues. Curr Med Chem 6:1095–1106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljunggren O, Ljunghall S 1993 The cyclic-AMP antagonist adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphosphorothioate, RP-isomer inhibits parathyroid hormone induced bone resorption, in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 193:821–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji H, Sugimoto T, Fukase M, Chihara K 1993 Role of dual signal transduction systems in the stimulation of bone resorption by parathyroid hormone-related peptide. The direct involvement of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Horm Metab Res 25:421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau KH, Baylink DJ 1998 Molecular mechanism of action of fluoride on bone cells. J Bone Miner Res 13:1660–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi M, Faber P, Ekema G, Jackson PD, Ting A, Wang N, Fontilla-Poole M, Mays RW, Brunden KR, Harrington JJ, Quarles LD 2005 Identification of a novel extracellular cation-sensing G-protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem 280:40201–40209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Tang SY, Cui RR, Huang J, Ren XH, Yuan LQ, Lu Y, Yang M, Zhou HD, Wu XP, Luo XH, Liao EY 2006 Apelin and its receptor are expressed in human osteoblasts. Regul Pept 134:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek O, Karsak M, Leclerc N, Fogel M, Frenkel B, Wright K, Tam J, Attar-Namdar M, Kram V, Shohami E, Mechoulam R, Zimmer A, Bab I 2006 Peripheral cannabinoid receptor, CB2, regulates bone mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:696–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS 2001 G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:368–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward P, Wada HG, Falk MS, Chan SD, Meng F, Akil H, Conklin BR 1998 Controlling signaling with a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:352–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern CH, Coward P, Degtyarev MY, Lee EK, Kwa AT, Hennighausen L, Bujard H, Fishman GI, Conklin BR 1999 Conditional expression and signaling of a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 17:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern CH, Degtyarev MY, Kwa AT, Salomonis N, Cotte N, Nanevicz T, Fidelman N, Desai K, Vranizan K, Lee EK, Coward P, Shah N, Warrington JA, Fishman GI, Bernstein D, Baker AJ, Conklin BR 2000 Conditional expression of a Gi-coupled receptor causes ventricular conduction delay and a lethal cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4826–4831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G 2002 Mouse α1(I)-collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Dev Dyn 224:245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furth PA, St Onge L, Boger H, Gruss P, Gossen M, Kistner A, Bujard H, Hennighausen L 1994 Temporal control of gene expression in transgenic mice by a tetracycline-responsive promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:9302–9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD, Sakata T, Leary C, Elalieh H, Ginzinger D, Rosen CJ, Beamer W, Majumdar S, Halloran BP 2002 Insulin-like growth factor I is required for the anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on mouse bone. J Bone Miner Res 17:1570–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec UT, Yuan D, Power RA, Wronski TJ 2006 Strain-dependent variations in the response of cancellous bone to ovariectomy in mice. J Bone Miner Res 21:1068–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Kalajzic Z, Maye P, Braut A, Bellizzi J, Mina M, Rowe DW 2005 Histological analysis of GFP expression in murine bone. J Histochem Cytochem 53:593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JC, Sakata T, Pfleger LL, Bencsik M, Halloran BP, Bikle DD, Nissenson RA 2004 PTH differentially regulates expression of RANKL and OPG. J Bone Miner Res 19:235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scearce-Levie K, Lieberman MD, Elliott HH, Conklin BR 2005 Engineered G protein coupled receptors reveal independent regulation of internalization, desensitization and acute signaling. BMC Biol 3:3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJ, Redfern CH, Harwood MD, Simpson PC, Conklin BR 2001 Abnormal contraction caused by expression of Gi-coupled receptor in transgenic model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280:H1653–H1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NA, Sabatakos G, Chen JS, Kelz MB, Nestler EJ, Baron R 2002 Regulating ΔFosB expression in adult Tet-Off-ΔFosB transgenic mice alters bone formation and bone mass. Bone 30:32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossert J, Eberspaecher H, de Crombrugghe B 1995 Separate cis-acting DNA elements of the mouse pro-α1(I) collagen promoter direct expression of reporter genes to different type I collagen-producing cells in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol 129:1421–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitzki A, Bar-Sinai A 1991 The regulation of adenylyl cyclase by receptor-operated G proteins. Pharmacol Ther 50:271–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield JF, Morley P, Willick GE, MacLean S, Ross V, Barbier J, Isaacs RJ 1999 Stimulation of femoral trabecular bone growth in ovariectomized rats by human parathyroid hormone (hPTH)-(1–30)NH2. Calcif Tissue Int 65:143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao D, He B, Jiang Y, Kobayashi T, Soroceanu MA, Zhao J, Su H, Tong X, Amizuka N, Gupta A, Genant HK, Kronenberg HM, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC 2005 Osteoblast-derived PTHrP is a potent endogenous bone anabolic agent that modifies the therapeutic efficacy of administered PTH 1–34. J Clin Invest 115:2402–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Sims NA, Hunzelman JL, Knight MC, Giovannetti A, Saxton JM, Kronenberg HM, Baron R, Schipani E 2001 Activated parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor in osteoblastic cells differentially affects cortical and trabecular bone. J Clin Invest 107:277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanske B, Amling M, Neff L, Guiducci J, Baron R, Kronenberg HM 1999 Ablation of the PTHrP gene or the PTH/PTHrP receptor gene leads to distinct abnormalities in bone development. J Clin Invest 104:399–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeysen S, Joubert L, Sebben M, Bockaert J, Dumuis A 2003 A single mutation in the 5-HT4 receptor (5-HT4-R D100(3.32)A) generates a Gs-coupled receptor activated exclusively by synthetic ligands (RASSL). J Biol Chem 278:699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Vaisse C, Conklin BR 2003 Engineering the melanocortin-4 receptor to control Gs signaling in vivo. Ann NY Acad Sci 994:225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruysters M, Jongejan A, Akdemir A, Bakker RA, Leurs R 2005 A Gq/11-coupled mutant histamine H1 receptor F435A activated solely by synthetic ligands (RASSL). J Biol Chem 280:34741–34746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]