Abstract

It has been shown that small interfering RNA (siRNA) partial knockdown of the α2δ1 dihydropyridine receptor subunits cause a significant increase in the rate of activation of the L-type Ca2+ current in myotubes but have little or no effect on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling. This study used permanent siRNA knockdown of α2δ1 to address two important unaddressed questions. First, does the α2δ1 subunit contribute to the size and/or spacing of tetradic particles? Second, is the α2δ1 subunit important for excitation-coupled calcium entry? We found that the size and spacing of tetradic particles is unaffected by siRNA knockdown of α2δ1, indicating that the visible particle represents the α1s subunit. Strikingly, >97% knockdown of α2δ1 leads to a complete loss of excitation-coupled calcium entry during KCl depolarization and a more rapid decay of Ca2+ transients during bouts of repetitive electrical stimulation like those occurring during normal muscle activation in vivo. Thus, we conclude that the α2δ1 dihydropyridine receptor subunit is physiologically necessary for sustaining Ca2+ transients in response to prolonged depolarization or repeated trains of action potentials.

INTRODUCTION

The dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) complex in the plasma membrane/transverse tubular system of skeletal muscle is composed of five subunits (α1, α2, β, δ, and γ) and serves at least three distinct functions. One of these functions is as a high-voltage-activated, L-type Ca2+ channel. As for other voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, the structures underlying voltage sensing and ion permeation reside in the α1 subunit (termed α1s, CaV1.1 in skeletal muscle). In addition to this function as a calcium channel, the CaV1.1 serves to link depolarization of the plasma membrane to Ca2+ release from the type 1 ryanodine receptor (RyR1) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which in turn causes contraction. This excitation-contraction (EC) coupling in skeletal muscle does not depend on the L-type Ca2+ current and is thought instead to reflect conformational coupling between the CaV1.1 and RyR1. Strong support for such conformational coupling is provided by the discovery of the retrograde interaction between the two molecules (1,2) and freeze fracture electron microscopy. The latter technique reveals that DHPR complexes are arranged in groups of four (termed “tetrads”) such that each tetradic particle, resulting from the fracture of a single complex, is aligned with one of the four identical subunits of an underlying RyR1 (3).

A third function of the DHPR complex is in the recently elucidated process termed “excitation-coupled calcium entry” (ECCE). In ECCE, depolarization causes the entry of extracellular Ca2+ via a pathway with pharmacological similarities to the pathway involved in store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) (4,5). However, ECCE differs from SOCE in that it does not require the emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores and it requires the presence of both the CaV1.1 and RyR1. Until our recent discovery (4,5), evidence for depolarization associated Ca2+ entry had only been indirectly demonstrated (6–8), but the mechanism for this entry remained elusive. In addition, the fact that muscle twitches (9) could be sustained in Ca2+-free external buffer focused attention away from seeking mechanisms for this entry, even though it had been known for a long time that prolonged contractions could not be sustained for long periods of time in the absence of external Ca2+ (10,11). Discrimination between depolarization induced SR Ca2+ release and sarcolemmal Ca2+ entry is technically difficult and therefore has limited investigations of ECCE in adult skeletal muscle fibers. However, recent results from studies using the Mn2+ quench technique on single dissociated flexor digitorum brevis fibers have recapitulated the existence of our ECCE results from myotube experiments; ECCE is seen in adult skeletal muscle fibers, and its rate is enhanced by ryanodine pretreatment (12).

An important tool for analyzing how the functions of the DHPR complex depend on its various subunits has been provided by animals bearing null mutations. Clearly important is CaV1.1, which consists of four repeat sequences, each having six transmembrane helices. EC coupling is absent in skeletal muscle of dysgenic mice, which are homozygous null for CaV1.1 (13–19), and there is an absence of large particles in the sarcolemma of these animals when subjected to freeze fracture studies (3). EC coupling is also absent in skeletal muscle of mice or zebrafish null for the cytoplasmic β1 subunit (16–20). In both mice and zebrafish, the absence of the β1 subunit results in an impaired trafficking of α1S to the plasma membrane. Additionally, the work on zebrafish has shown that those α1S subunits that do reach the plasma membrane lack a well-defined association with RyR1 in β1-null fish (20). Genetic deletion of the γ subunit, which contains four transmembrane helices, does not markedly affect muscle function (13,21).

The α2 and δ subunits contribute almost half of the total mass of the DHPR and arise by cleavage of a common precursor. The α2 subunit is positioned on the extracellular side of the plasma membrane and is disulfide bonded to the δ subunit, which has a single transmembrane span (22). Mice null for the α2δ isoform that is expressed in skeletal muscle (α2δ1) appear to have an embryonic or birth lethal phenotype (J. Offord, Pfizer, Groton, CT, personal communication, 2007). Thus small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown represents a useful alternative for examining the roles of α2δ1 in skeletal muscle. Previously, it was shown that siRNA partial knockdown of α2δ1 caused a significant increase in the rate of activation of the L-type Ca2+ current in myotubes but had little or no effect on skeletal EC coupling (23). The goal here was to use siRNA knockdown to address two important questions not examined in these previous studies. We chose the myotube system rather than adult fibers because only with myotubes is it possible to study a defined population of cells with the identical amount of gene silencing in each cell and because we previously demonstrated that the two systems recapitulate each other in areas we wished to study.

The first question posed was, is the α2δ1 DHPR subunit important for ECCE (4,5)? The second question was, does the α2δ1 subunit contribute to the size and/or spacing of tetradic particles? With respect to the latter question, we found that the size and spacing of tetradic particles is unaffected by siRNA knockdown of α2δ1, which may indicate that the α2δ1 protein does not affect the fracturing process and that the visible particle represents the α1s subunit. Strikingly, in response to the first question we found that knockdown of α2δ1 leads to a nearly complete loss of physiologically stimulated ECCE, which results in a rapid decrement in the size of myoplasmic Ca2+ transients during bouts of repetitive stimulation like those occurring during normal muscle activation in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and siRNA transduction

Primary murine myoblasts were cultured on collagen-coated 10 cm plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) for propagation and on Matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) coated plates (96-well plates (Opticlear Costar 3614) for imaging, and 10 cm dishes for membrane preparations) in Ham's F10 20% fetal bovine serum, 5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 100 units/ml penicillin-G in 5% CO2. Myoblasts were transduced three times with one of two different pSiREN retrovirus constructs (Fig. 1 A) containing α2δ1 complementary sequences connected by a central hairpin loop SIR1: 5′… G TGT GAG CGG ATT GAC TCT … 3′, and SIR2: 5′… G GCA CGC TTT GTG GTG ACA …3′ (Fig. 1 A) and selected for puromycin resistance conferred by the vector. Resistant cells were then plated at clonal density and 20 individual clones screened for α2δ1 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression by TaqMan real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to select for cells expressing <2% of control. A previously created TRPC3 siRNA knockdown cell line was used as a control for possible off-site nonspecific effects of siRNA (24). For Ca2+ imaging, electrophysiology, freeze fracture, or biochemistry transduced cells were allowed to reach 60%–70% confluence and were induced to differentiate into myotubes for 5 days by changing the growth medium to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 2% heat-inactivated horse serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 100 μg/ml penicillin-G in 20% CO2.

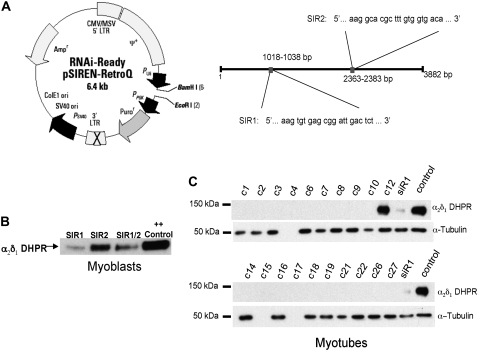

FIGURE 1.

siRNA vector construction and effects of α2δ1 siRNA knockdown on expression of α2δ1 protein in primary myoblasts and myotubes. (A) Sequences of siR1 and siR2 and vector map of retroviral construct used to transduce primary muscle cells. (B) Western blot showing expression of α2δ1 in pools of primary myoblasts after transduction three times with retrovirus expressing constructs for siR1 and siR2. (Note siR2 did not significantly lower α2δ1 expression.) (C) Western blots showing expression of α2δ1 in myotubes derived from 27 individual myoblast clones that had been transduced three times with retrovirus expressing siR1. α-tubulin (lower band) used as the loading control. All clones with the exception of C12 showed negligible expression compared to control. At the right extracts from siR1 pooled myoblasts and control myoblasts are shown as controls.

Membrane preparation and immunoblotting

Crude membrane preparations were made from myotubes after 5 days in differentiation media. Myotubes were harvested in harvest buffer (137 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, and 0.6 mM EDTA, pH 7.2) from 10–15 10 cm plates and centrifuged for 10 min at 250 × g. The pellet was resuspended in buffer consisting of 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, supplemented with 1 mM EDTA, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.7 μg/ml pepstatin A, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and then homogenized using a Polytron cell disrupter (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY). The whole cell homogenates were centrifuged for 20 min at 1500 × g max, and the supernatants were collected and recentrifuged for 60 min at 100,000 × g max at 4°C. The membrane pellets were finally resuspended in 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Western blot analysis was done on a heavy SR fraction from control and α2δ1 DHPR knockdown myotubes using a method published previously (25). The membrane fractions were solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate and size fractionated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The polyacrylamide gels were then blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and, after blocking, hybridized with the appropriate primary antibody. They were then probed with a horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody and level of expression determined with chemilumenescence. The samples were probed for RyR1, CaV1.1, α2δ1, skeletal calsequestrin (CSQ), FK506-binding protein 12 kDa (FKBP12), SR/ER Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1), and skeletal triadin (25). Anti-β-tubulin (26) was used as a loading control.

Quantitative PCR

TaqMan Real Time PCR analysis was performed on total RNA extracted from two 10 cm plates of differentiated myotubes using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). α2δ1 mRNA levels relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels were determined by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction using predeveloped commercial TaqMan Gene Expression Assays from Applied Biosystems (Assay ID: Mm00486607_m1; Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions in an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System for 50 cycles. α2δ1/GAPDH mRNA ratios were obtained from the equation 2−ΔCT, where ΔCT is the difference in threshold cycles between α2δ1 and GAPDH.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Cells were fixed in cold methanol (27,28). After blocking, fixed cells were hybridized with an anti-α2δ1 primary mouse monoclonal antibody (20A, Hybridoma Studies Bank, University of Iowa) and then hybridized with a goat anti-mouse Cy3 labeled secondary antibody and observed with a 100× oil immersion lens on an Olympus IX70 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Whole-cell measurements of Ca2+ currents

Ca2+ currents were measured (29,30) using whole-cell patch-clamping with a Warner PC501 patch amplifier (Hamden, CT). Cells were patched with pipettes that were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries to a resistance of 1.7–3.0 MΩ. Pipettes were filled with internal solution containing (in mM) 140 CsAsp, 5 MgCl2, 10 Cs2 EGTA, and 10 HEPES, with the pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH. After a seal was formed, the bath was perfused with an additional ∼10 ml of the external solution containing (in mM) 145 tetraethylammonium (TEA), 10 CaCl2, 0.003 tetrodotoxin, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with CsOH. Control currents, elicited by 20–40 ms voltage steps from −80 mV to −110 mV, were used to determine linear capacitance (cells >800 pF were excluded from further analysis). The voltage clamp command sequence was to sequentially step from: a holding potential of −80 mV, to −20 mV (200 ms), to −50 mV (75 ms), to the test potential (20 ms), to −50 mV (125 ms), and back to −80 mV. Test potentials ranged in 10 mV increments from voltages from −20 to +60 mV/+80 mV. Test currents were corrected for linear components of leak and capacitive currents by digital scaling and subtraction of the average of 10 control currents, which were elicited with the pulse protocol just described, with a 200 ms test potential of −80 mV.

Peak current density-voltage relationships of individual cells were fitted with the equation

|

where I is the peak current density at test potential V, Gmax the maximum Ca2+ conductance, Vrev the reversal potential, V1/2 the potential for half-maximal activation of conductance, and k the slope factor. Time constants of current activation were determined by fitting individual current records with a single (α2δ1 knockdown) or double (normal) exponential function.

All data are presented as mean ± SE.

Freeze fracture and measurements of intratetrad distance

The cells were washed twice in phosphate buffer saline at 37°C, fixed in 3.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, stored in fixative for 1–4 weeks, and briefly infiltrated in 30% glycerol. A small piece of the coverslip was mounted with the cells facing a droplet of 30% glycerol, 20% polyvinyl alcohol on a gold holder, and then frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled propane. The coverslip was flipped off to produce a fracture that followed the cell surface originally facing it. The fractured surfaces were shadowed with platinum at 25° while rotating and then replicated with carbon in a Balzers freeze fracture machine (model BFA 400; Balzers Spa, Milan, Italy). Replicas were photographed in a Philips 410 Electron Microscope 410 (Philips Electron Optics, Mahwah, NJ). The specimen holder was positioned in the eccentric position to minimize variations in electron optical magnification. Parallel culture dishes were immunolabeled (see Immunohistochemistry analysis above).

Measurements of intratetrad distance

The distances between the pale center of each black ring of platinum (representing a DHPR complex) and the centers of its nearest neighbors in a tetrad were measured using the NIH Image software on micrographs taken at a magnification of 33,900 and scanned at a resolution of 1200 dpi. Measurements on α2δ1 knockdown cells were done on clones C12 and C14. To minimize variations due to distortion of the proteins during fracturing, measurements were taken only from portions of tetrads in which the angle subtending the lines connecting three adjacent particles was 90° or close to it. Incomplete tetrads with one particle missing as well as complete four-particle tetrads were used for the measurements. Blind data collection was insured by randomly mixing images from control and knockdown cells.

Myotube Ca2+ imaging

Stock concentrations of caffeine solutions were prepared in imaging buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 6 mM glucose, and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). In KCl-containing solutions the concentration of NaCl was adjusted as necessary to maintain the total ionic strength (KCl + NaCl) equal to 130 mM.

Differentiated myotubes were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 37°C for 20 min in imaging buffer as described previously (31). The cells were then washed three times with imaging buffer and transferred to a Nikon TE2000 microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Fluo-4 was excited at 494 nm, and fluorescence emission was measured at 516 nm using a Nikon 40× FluorApo oil 1.3 numerical aperture (na) objective. Data were collected with an intensified 12-bit digital intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD; Stanford Photonics, Stanford, CA) from regions consisting of 10–20 individual cells and analyzed using QED software (QED, Pittsburgh, PA). Test agents were delivered using the Multivalve Perfusion System (Automate Scientific, Oakland, CA). A dose response curve for a single agent was performed by adding an ascending concentration of that agent in any given well to compare the response to any given agent of the cells expressing the α2δ1 siRNA to that of cells expressing wild-type-type (wt) α2δ1 protein.

To compare different experiments, individual response amplitudes were normalized to the maximum fluorescence obtained in the same cell depolarized with 60 mM KCl. To test for differences in Ca2+ stores, a group of both wt and α2δ1 knockdown cells were exposed to 200 nM thapsigargin (TG) in the presence of nominal Ca2+-free media and the Ca2+ release response recorded. To test that a deficiency in Ca2+ entry during depolarization might be responsible for the observed responses of α2δ1 knockdown cells to depolarization, cells were pretreated with nominal Ca2+-free buffer for 1 min before depolarization in the same nominal Ca2+-free buffer with 60 mM KCl. Where indicated, nonlinear regression with sigmoidal dose-response analysis was performed using Prism version 4.0. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Additional experiments were performed to measure cell responses to electrical pulse trains. Myotubes were loaded with Fluo-4 as described above and fluorescence emission (516 nm) acquired with an IC-300 ICCD camera (Photon Technology International, Lawrenceville, NJ). Data were captured, digitized, and stored on computer using ImageMaster software (Photon Technology International). Bipolar electrical field stimuli were applied using two platinum electrodes fixed to opposite sides of the well and connected to an AMPI Master 8 stimulator set at 3 V, 25 ms pulse duration, over a range of frequencies (0.05–20 Hz). In these experiments, data were acquired at 200 ms intervals. In separate experiments, a fatigue stimulus protocol was applied. Electrical pulses (7 V, 1 ms duration) were applied at 100 Hz for 500 ms interspersed with 500 ms rest for a total duration of 5 min. The frequency-transient amplitude relationship was studied using 3 s pulse trains in a range of 1–120 Hz.

Mn2+ quench and electrical field stimulation

Mn2+ influx was measured as previously described (32,33). Briefly, differentiated primary wt or α2δ1 knockdown myotubes were loaded with fura-2, the cells were imaged using an ICCD camera with an Olympus 40× oil 1.2 na objective, and data were collected from 3–10 individual cells at five frames per second. The isosbestic wavelength for fura-2 was calibrated at the beginning of each experiment. A final concentration of 500 μM MnCl2 (in the presence of 1.2 mM external Mg2+) was used, and emission was monitored at 510 nm. Cells loaded with fura-2 (5 μM) were stimulated with either local application of K+ or by electrical field stimulation as described above. To compare the effects of α2δ1 DHPR knockdown on both traditional store depletion induced entry (SOCE) and ECCE, myotubes were pretreated for 10 min with 200 nM TG followed by confirmation that the stores were empty with a challenge with 20 mM caffeine. Mn2+ quench experiments were only performed on cells that did not respond to the caffeine challenge (>99%).

RESULTS

Construction of siRNA vectors that efficiently knock down expression of the α2δ1 DHPR subunit

We used the following general design guidelines to construct our two siRNA vectors: 1), find 21 nt sequences in the target mRNA that begins with an adenine dinucleotide, 2), select several target sequences with 30%–60% GC content and no stretches of >4 Ts or As at different positions along the length of the gene sequence, and 3), compare the potential target sites to the appropriate genome database to eliminate from consideration any target sequences with more than 16–17 contiguous basepairs of homology to other coding sequences.

Fig. 1 A shows a map of the location of the two selected siRNA sequences in the α2δ1 complementary DNA (cDNA). Because myoblasts are difficult to transfect at high efficiency and because of the need to have multiple copies of the vector permanently integrated in the cell to reduce expression of the target mRNA to <2% of control, a pSiREN retrovirus was used to transduce the cells at moiety of infection = 5 on three separate occasions (34,35). Between transductions, cells were selected with puromycin to eliminate any cells that were not transduced with at least one copy of the vector from the cell population. Western blot analysis of pooled cells after the third round of infection with the siRNA retrovirus demonstrated that although both siR1 and 2 reduced the expression of α2δ1 in myoblasts, siR1 was much more efficient at this task (Fig. 1 B). Cells from pool 1 were plated at clonal density and the clones expanded. As can be seen in Fig. 1 C, myotubes derived from most of the clones from this pool did not produce sufficient α2δ1 protein to be detected by Western blot analysis.

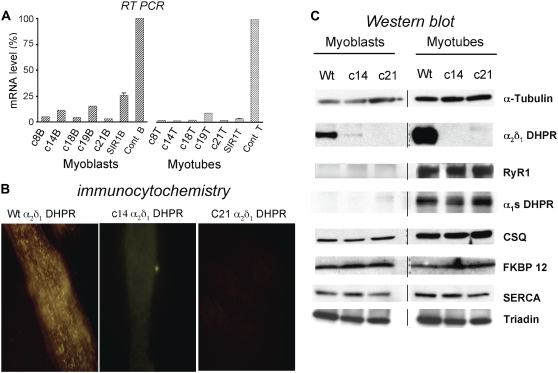

In Fig. 2 A, TaqMan analysis of representative clones demonstrated that transcription of α2δ1 mRNA could be reduced to <5% of control in myoblasts and <2% of control in myotubes transduced with siR1. Two myoblast clones, C14 and C21, were chosen for further analysis, and the results of all of the studies done were identical in both. When only one cell line is presented, we present the data from clone C14 as the representative value. Immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2 B) confirms that in wt cells α2δ1 DHPR has a punctate pattern of expression (23,36), which is dictated by the positioning of CaV1.1 (36) and RyR1 (27). In α2δ1 DHPR siRNA knockdown myotubes, there is no α2δ1 DHPR detectable (Fig. 2 B), but the absence of the α2δ1 DHPR does not affect the targeting of CaV1.1 or RyR1 (data not shown). Cells transduced with the “control” TRPC3 siRNA, to ascertain possible nonspecific consequences on protein expression, have a wt pattern of α2δ1 DHPR expression (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of α2δ1 knockdown on α2δ1 mRNA levels, α2δ1 protein expression and targeting, and expression of muscle triad proteins. (A) Transcription of α2δ1 mRNA is significantly knocked down in myoblasts and myotubes of both clones that were selected for further study. (B) Immunohistochemistry with anti-α2δ1 antibody demonstrates that in control myotubes, α2δ1 DHPR is targeted appropriately with the characteristic punctate appearance near the cell surface, similar to the staining pattern for α1S DHPR or RyR1 (27). Myotubes from α2δ1 knockdown clones 14 and 21 have no visible α2δ1 subunit expression. (C) Western blot analysis of myoblasts (left) and myotubes (right) from wt and α2δ1 knockdown clones 14 and 21. Note that α2δ1 is expressed at high levels in wt myoblasts and myotubes, whereas α1S DHPR is expressed only in myotubes. The expression of α2δ1 protein in knockdown clones 14 and 21 appears to correlate with the α2δ1 mRNA levels: traces of protein and transcript were seen in clone 14 myoblasts, but protein and transcript were essentially not expressed in clone 21 myoblasts or clones 14 and 21 myotubes. The lack of expression of α2δ1 appears to have no effect on the expression of any other triadic protein probed.

Western blot analysis of heavy SR fractions from control and α2δ1 DHPR knockdown myotubes probed for RyR1, α1S DHPR subunit, CSQ, FKBP12, SERCA1, and skeletal triadin (β-tubulin was used as a loading control) demonstrates that there is no detectable α2δ1 DHPR protein in either of the two clones used in this study but that the absence of the α2δ1 subunits was not associated with any differences in the expression of any other triadic protein tested in either myoblasts or myotubes (Fig. 2 C). Cells transduced with the “control” TRPC3 siRNA have wt amounts of α2δ1 DHPR protein as well as RyR1, CaV1.1, CSQ, FKBP12, SERCA1, and skeletal triadin on Western blot analysis (data not shown), showing that the phenotype of the α2δ1 knockdown is not simply the result of a nonspecific “off target” artifact caused by siRNA expression.

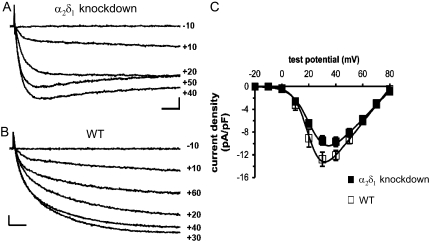

The effects of α2δ1 knockdown on L-type Ca2+ current

To determine the effects of α2δ1 knockdown on the function of the DHPR complex as Ca2+ channel, the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration was used to measure membrane Ca2+ currents (Fig. 3, A–C). Comparison of representative records demonstrates that, as reported previously (23), currents from α2δ1 knockdown myotubes (Fig. 3 A) activate more rapidly than those from normal myotubes (Fig. 3 B). Activation of currents from normal myotubes was best fitted with the sum of two exponential functions, with a dominant contribution by the slower of these two. The average time constants for these two exponential functions (7.6 ± 0.9 ms and 71.0 ± 3.8 ms; Table 1) were similar to those found previously for normal myotubes (8.5 ± 1.2 ms and 79.5 ± 10.5 ms) by Avila and Dirksen (37). Activation of currents from α2δ1 knockdown myotubes could be well fitted with a single exponential function having a time constant (6.4 ± 0.3 ms) similar to that of the faster component for wt myotubes (Table 1). At the potential evoking maximal inward current, α2δ1 knockdown currents inactivated on average by 25% ± 4% at the end of a 200-ms test pulse, whereas no inactivation was observed for wt myotubes (Table 1). Peak current-voltage relationships were similar for α2δ1 knockdown and normal myotubes, although Gmax was somewhat lower for α2δ1 knockdown myotubes (Fig. 3 C; Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of Ca2+ currents in α2δ1 knockdown and normal myotubes. Representative currents elicited by 200 ms test pulses to the indicated potentials are shown from α2δ1 knockdown (A) and normal (B) myotubes. Scale bars are 2 pA/pF (vertical) and 20 ms (horizontal). (C) Average voltage dependence of peak current densities for α2δ1 knockdown (closed symbols, n = 18) and normal myotubes (open symbols, n = 9). Smooth curves represent the Boltzmann equation (see Materials and Methods) with average parameters (Table 1) obtained from best fits of the same equation to current-voltage relationships of individual cells.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of whole cell Ca2+ currents in wt and primary α2δ1 knockdown myotubes

| Gmax (pS/pF) | V1/2 (mV) | Vr (mV) | k | Inactivation at 200 ms | τslow (ms) | τfast (ms) | Aslow (pA/pF) | Afast (pA/pF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt (n = 9) | 307 ± 24 | 28.0 ± 1.5 | 81.1 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | NA | 71.0 ± 3.8 | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.2 |

| α2δ1 k.d. (n = 18) | 248 ± 18* | 22.5 ± 1.3 | 83.1 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 0.3* | (25 ± 4)% | NA | 6.4 ± 0.3 | NA | 9.2 ± 0.8 |

Current time courses of α2δ1 knockdown cells were fitted with a single exponential function, and current time courses of wt myotubes were fitted with a double exponential function.

p < 0.05 vs. wt.

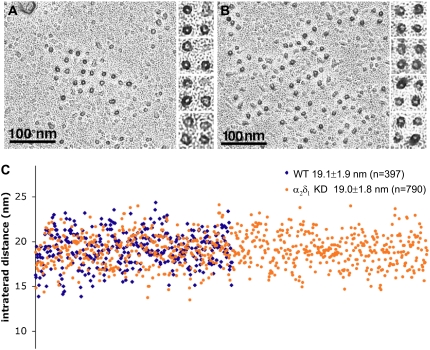

α2δ1 knockdown does not affect DHPR complex tetrad formation and intratetrad spacing

Clusters of DHPR-complex tetrads are equally visible in control and α2δ1 DHPR knockdown cells (Fig. 4). Indeed in this particular set of experiments the clusters in the controls (Fig. 4 A) tended to contain fewer and less complete tetrads than those in the treated cells (Fig. 4 B). Since formation of DHPR-complex tetrads requires an interaction with RyR1, it is clear that α2δ1-null DHPR complexes are appropriately targeted to the calcium release units (CRUs) and appropriately positioned relative to RyRs.

FIGURE 4.

Tetrads are unaffected by α2δ1 knockdown. (A and B) A dark ringlet of platinum surrounds the freeze fracture particles, each marking the position of the DHPR. Particles and their disposition into tetrads appear identical in the control (left) and α2δ1 knockdown cells, indicating that the α2δ1 subunit is not part of the DHPR particle seen using this technique. (C) The center-to-center distance between particles constituting tetrads (intertetrad distance) was measured in electron micrographs at a magnification of ∼85,000×. The tetrads to be measured were selected because they all show a minimum of distortion as a result of fracturing. The images from experimental and control cells were mixed during the analysis so that measurements were performed by a “blind” operator. The data are presented in a scattergram in which each dot represents a single measurement and the x axis is the dot number from 1 to 790. There were no differences in intratetrad distance between the two groups (p > 0.7). All myotubes were fixed in glutaraldehyde, cryoprotected in glycerol, freeze fractured, and rotary shadowed at 45°.

The apparent size of the particles, as indicated by the ring of platinum deposited around them, is not different in the two sets of cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Most importantly, the center-to-center distance between adjacent particles in the tetrads, or intratetrad distance, is also not altered by the absence of α2δ1. Fig. 4 C shows a scattergram of the measured intratetrad distances, each represented by one dot, blue for controls and orange for treated cells. The x axis of this scattergram is the tetrad number, ranging from 1 to 790. Despite the scatter in the data, due to the distortion that can occur during fracturing, the two average intratetrad distances are the same (19.1 ± 1.9 nm for control and 19.0 ± 1.8 nm for α2δ1 DHPR-null cells), and Student's t-test indicates that the two populations are indistinguishable (p = 0.25). This would strongly suggest that 1), the CaV1.1 and not the α2δ1 subunit is the protein which is observed as the large intramembrane particle when the sarcolemma is fractured; and 2), the α2δ1 subunit, which is proposed to be a largely extracellular protein, plays no role in the appearance of this particle, in tetrad formation, or in the position of the complexes, as indicated by the intratetrad distance.

α2δ1 is not essential for EC coupling but is important for maintaining Ca2+ transients during sustained depolarization

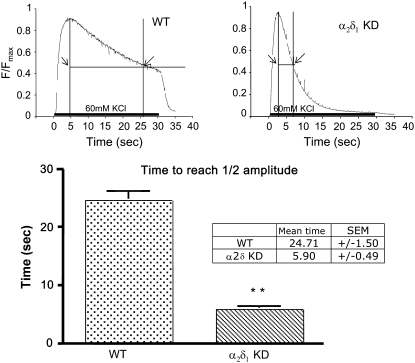

α2δ1 knockdown cells, in which the mRNA levels were reduced to <2% of control, produced Ca2+ transients in response to caffeine which were not significantly different from wt in terms of the peak amplitude (0.75 ± 0.02 Fmax for wt and 0.76 ± 0.3 Fmax for α2δ1 knockdown), rate of decay (data not shown), and concentration for half-maximal activation (EC50 = 4.6 mM in α2δ1 knockdown vs. 4.6 mM for wt). Moreover, α2δ1 knockdown had no significant effect on the amplitude and rate of rise of the Ca2+ transient after depolarization with 60 mM KCl (Fig. 5). However, the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient during maintained depolarization was significantly more rapid in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes than in wt. The half-decay time measured as the time (x) axis width of the transient at half-maximum tension fell from 24.7 ± 1.5 s in wt to 5.9 ± 0.5 s in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes (Fig. 5). With this exception the responses from myotubes permanently transduced with the control siRNA were indistinguishable from those seen in controls, demonstrating that the cause of the decrease in the duration of the Ca2+ transient and by inference all the other findings were not due to nonspecific “off target” siRNA effects.

FIGURE 5.

Compared to wt myotubes, α2δ1 knockdown myotubes have abbreviated Ca2+ transients during KCl depolarization. Representative, raw Fluo-4 signals during a 30-s 60-mM KCl depolarization of wt (left) and α2δ1 knockdown (right) myotubes. The bar graphs in the bottom panel show that the half-decay time for the Fluo-4 transient in response to a 30-s 60-mM KCl depolarization is significantly shorter in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes than in wt myotubes. Data are shown as mean ± SE. **p < 0.01; n = 130 myotubes for wt and n = 240 for α2δ1 knockdown.

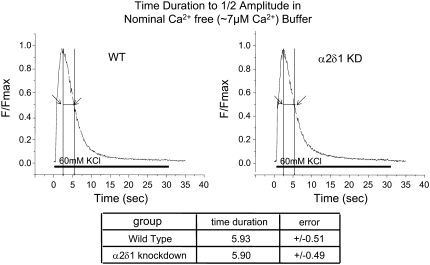

Importantly, the difference in the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient during KCl depolarization between α2δ1 knockdown and wt myotubes could be abolished if extracellular Ca2+ was reduced to 7 μM and extracellular Mg2+ increased to 3 mM to maintain the concentration of external divalent cations. Under these conditions, the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient in both groups of myotubes was similar to that of α2δ1 knockdown myotubes in Ca2+-replete medium (mean ½ decay time of ∼5.9 s) (Fig. 6). This strongly suggests that a loss of external Ca2+ entry during the 30 s depolarizing stimulus contributes to the reduced duration of the Ca2+ transient in the α2δ1 knockdown myotubes.

FIGURE 6.

α2δ1 knockdown and wt myotubes have Ca2+ transients of similar duration in low Ca2+ buffer. Representative average raw Fluo-4 signals during 30-s 60-mM KCl depolarization of n = 65 wt (left) and n = 72 α2δ1 knockdown (right) myotubes when the depolarization is done in a buffer containing ∼7 μM Ca2+ and 3 mM Mg2+. The summary below shows the average time to ½ amplitude ± mean ± SE. There is no significant difference between the two genotypes under these conditions. p > 0.8.

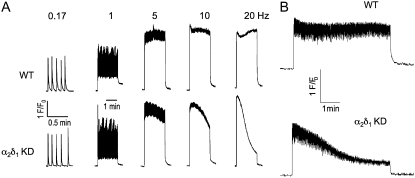

The relationship between stimulation frequency and Ca2+ transient amplitude was studied with pulse trains ranging from 1 to 120 Hz (3 ms duration) and was not found to differ between wt and α2δ1 knockdown myotubes at any these frequencies (data not shown). Fig. 7 A shows that the amplitudes of Ca2+ transients produced by short electrical stimuli are not significantly different between wt and α2δ1 knockdown myotubes. However, unlike wt myotubes, α2δ1 knockdown myotubes failed to maintain the peak amplitude of their Ca2+ transients for a prolonged, full 120 s, pulse train when the stimulus frequency was increased above 1 Hz. The rate of decay was directly related to the stimulus frequency (Fig. 7 A). Cells were also tested for the rate of fall in their peak Ca2+ transient in response to a stimulus protocol similar to those used on adult skeletal muscle cells to produce fatigue. Fig. 7 B shows that the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was unaffected during a long (5 min) pulse train composed of bursts lasting 500 ms interspersed by a 500 ms rest period as described in Materials and Methods in wt cells. By contrast, α2δ1 knockdown cells subjected to the same stimulus protocol had a steady decline in the amplitude of their Ca2+ transient. Thus we conclude that the α2δ1 DHPR subunit is physiologically necessary for sustaining Ca2+ transients in response to prolonged depolarization or repeated trains of action potentials.

FIGURE 7.

α2δ1 knockdown myotubes fail to maintain their Ca2+ transient amplitude with electrical pulse trains >1 Hz. (A) Cells were stimulated by sequential bipolar electrical pulse trains lasting 120 s at frequencies ranging from 0.17 to 20 Hz with a 1 min rest period between each frequency tested. The rate of decline of the peak Ca2+ transient amplitude was proportional to the stimulus frequency. These data are representative of measurements acquired from n = 3 wt and n = 8 α2δ1 knockdown myotubes using the indicated stimulus sequence protocol. (B) Ca2+ transient amplitudes were resistant to rundown in wt, but not α2δ1 knockdown, myotubes stimulated with electrical pulse trains similar to those commonly used to elicit fatigue in adult fibers, as described in Materials and Methods. The data are representative of n = 20 wt and n = 36 knockdown cells.

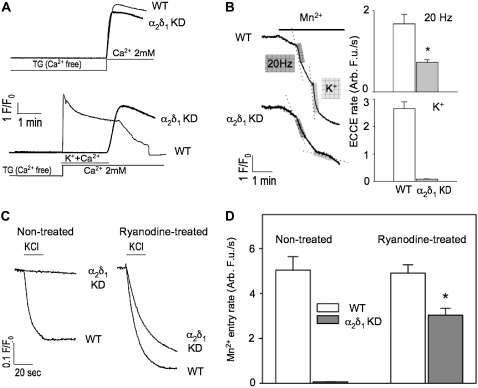

α2δ1 knockdown inhibits ECCE

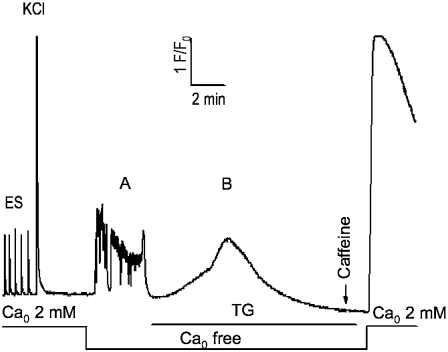

We next tested the hypothesis that the mechanism for the more rapid decay of Ca2+ transient amplitude in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes was that α2δ1 is needed to maintain ECCE, SOCE, or both. To test the effects of α2δ1 knockdown on SOCE, we depleted SR Ca2+ stores completely with TG while exposing the cells to nominally Ca2+-free external medium. After store depletion was confirmed with the absence of any Ca2+ response to exposure to 20 mM caffeine, addition of 2 mM Ca2+ to the external medium clearly showed the presence of SOCE (as measured by the Ca2+ transient that accompanied the return to Ca2+-replete medium) (Fig. 8). Using this depletion protocol, the same rate and amplitude of SOCE was measured in both wt and α2δ1 knockdown myotubes (Fig. 9 A, upper traces). In a separate set of experiments, Ca2+-depleted myotubes were perfused with an external medium containing 40 mM K+ and 2 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 9 A, lower traces). K+ depolarization elicited rapid Ca2+ entry in wt cells via ECCE, whereas α2δ1 knockdown myotubes failed to show any detectable Ca2+ entry while the cells were depolarized. When K+ was removed from the Ca2+-replete external medium, a rapid Ca2+ entry was observed in the α2δ1 knockdown myotubes similar to their previous response with no depolarization (Fig. 9 A, lower traces). Thus the abolition of ECCE during KCl depolarization in the α2δ1 knockdown myotubes allowed the direct demonstration that SOCE is completely inhibited by sarcolemmal depolarization.

FIGURE 8.

Complete SR Ca depletion protocol for α2δ1 knockdown myotubes. Cells were loaded with Fluo-4 as described in Materials and Methods and tested for responses to electrical pulses and K+ (40 mM) application in Ca-replete medium ( 2 mM). The extracellular solution was exchanged with one lacking added Ca2+ (

2 mM). The extracellular solution was exchanged with one lacking added Ca2+ ( free); it elicited spontaneous activity in most cells. TG (200 nM) was then perfused onto the cells in the

free); it elicited spontaneous activity in most cells. TG (200 nM) was then perfused onto the cells in the  -free medium until the new baseline was established (typically <10 min) and depletion of SR Ca tested with a 20 mM caffeine challenge. The presence of SOCE was then tested by perfusion of 2 mM Ca2+ medium. This protocol completely depleted SR Ca in >95% of all myotubes exhibiting EC coupling. Wt myotubes were indistinguishable from the α2δ1 knockdown myotubes shown here.

-free medium until the new baseline was established (typically <10 min) and depletion of SR Ca tested with a 20 mM caffeine challenge. The presence of SOCE was then tested by perfusion of 2 mM Ca2+ medium. This protocol completely depleted SR Ca in >95% of all myotubes exhibiting EC coupling. Wt myotubes were indistinguishable from the α2δ1 knockdown myotubes shown here.

FIGURE 9.

α2δ1 knockdown selectively inhibits ECCE but not SOCE. (A) (Upper traces) α2δ1 knockdown had no effect on initial rate and amplitude of SOCE under condition of severe store depletion elicited by TG (200 nM). (Lower traces) ECCE is completely abolished in K+-depolarized α2δ1 knockdown myotubes. Note that K+ depolarization in the presence of external Ca2+ reveals the complete inhibition of SOCE even under conditions of severe depletion. (B) Representative traces showing Mn2+ quench of fura-2 fluorescence in α2δ1 knockdown cells was significantly reduced when a 20 Hz electrical pulse train was applied or completely abolished when the cells were exposed to 60 mM KCl. (C) Representative traces of KCl depolarization induced Mn2+ influx pre- and posttreatment with ryanodine. Although there is a brisk Mn2+ influx in wt cells when they are exposed to 60 mM KCl, there is no Mn2+ influx in α2δ1 knockdown cells under normal conditions. However, when the cells are pretreated with high concentrations of ryanodine (500 μM) for 30 min ECCE can be partially rescued (∼40% of wt) by the change in the conformation of RyR1 caused by ryanodine exposure. (D) Even in the presence of ryanodine, the amount of Mn2+ entry in α2δ1 knockdown cells is significantly reduced compared to wt. N > 20 for each group.

We also examined Mn2+ quench of fura-2 fluorescence during electrical (20 Hz trains) and 40 mM K+ depolarization. Fig. 9 B shows that the rate of Mn2+ entry is significantly reduced (p < 0.0003) in response to either KCl or electrical depolarization in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes. The rate of Mn2+ entry is reduced by more than twofold in response to electrical stimulation, and it is abolished in response to K+ depolarization.

ECCE requires the presence of RyR1 and CaV1.1 and is very dependent on the conformation of RyR1. We have shown that ECCE can be enhanced by two conformational mutations of RyR1 that do not support normal EC coupling (4) or by pretreatment of murine myotubes (4,5) or muscle fibers (12) with 250–500 μM ryanodine. This apparent enhancement of ECCE elicited by changes in the conformation of RyR1 caused by mutations or ryanodine binding is primarily a result of delayed inactivation/deactivation of entry during depolarization and not increased activation. To test the hypothesis that the α2δ1 subunit was key to the interaction of the three Ca2+ channels participating in ECCE, we pretreated α2δ1 knockdown myotubes with either 500 μM ryanodine or solvent (control) for 30 min and performed Mn2+ quench experiments similar to those described above. In Fig. 9, C and D, it can be seen that, unlike wt myotubes, 40 mM K+ depolarization of α2δ1 knockdown myotubes in the absence of ryanodine pretreatment failed to permit Mn2+ entry. However α2δ1 knockdown myotubes pretreated with ryanodine regained a robust long-lived K+-triggered Mn2+ entry response, although the initial rate was much (∼60%) smaller than the rate seen in wt (Fig. 9 D). This would indicate that although the α2δ1 subunit is required for physiologic ECCE, its absence can be partially overcome when RyR1 is put into a conformation that enhances this depolarization-induced Ca2+ entry.

DISCUSSION

α2δ1 is not necessary for myotube growth or differentiation

Despite the almost complete absence (<2%) of the α2δ1 DHPR subunit, there appears to be no change in the ability of the myoblasts to form myotubes or in the expression levels or targeting of CaV1.1 to the CRU (28,38). This is similar to the report of Obermair et al. (23), who studied transiently siRNA transfected cells with a reduction in α2δ1 mRNA to 6%–25% of control. In addition, the absence of the α2δ1 DHPR subunit did not affect the expression of several other components of the triad (RyR1, FKBP12, CaV1.1, CSQ, Triadin, SERCA), suggesting that the α2δ1 subunit is not important for the expression or normal targeting of these CRU proteins.

Unlike CaV1.1, the α2δ1 subunit is expressed in both myoblasts and myotubes, and α2δ1-null mice have an embryonic or birth lethal phenotype (J. Offord, Pfizer, Groton, CT, personal communication, 2007), suggesting that the α2δ1 may play a role in embryonic development of components other than muscle. Our data show that whatever the early function of α2δ1 in myoblasts, it is not necessary for myoblast division, their differentiation into myotubes, or basic EC coupling.

The effects of the absence of the α2δ1 subunit on slow voltage-gated Ca2+ current

Overall, our results on Ca2+ currents in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes are in good agreement with those reported previously showing that the fundamental functions of the DHPR complex as Ca2+ channel do not depend on the presence of the α2δ1 subunit (23). In particular, α2δ1 knockdown had little effect on the amplitude or voltage dependence of L-type Ca2+ currents but did result in accelerated activation kinetics. Additionally, in response to 200-ms depolarizations, the L-type currents displayed greater inactivation in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes, perhaps because inactivation in wt myotubes was obscured by the slower activation kinetics.

Lack of the α2δ1 subunit reveals the position of CaV1.1 in DHPR complex tetrads

Freeze fracture reveals the position of intramembranous proteins, but it cannot be reliably used to define the size and shape of the proteins that are fractured in the frozen state. For example, the very large ryanodine receptor of the SR produces a barely visible shallow hump when fractured (39). Nevertheless, we are surprised to find that even though the α2δ1 is a very large subunit, the DHPR complex particles are neither absent nor grossly distorted in its absence. The importance of this result lies in the fact that we can, albeit at a low level of resolution, predict the position of the α1s DHPR mass relative to the four RyR subunits (40). The channel would be located somewhat peripherally relative to the RyR outline in such a manner that some portion of it could extend over the side of RyR1.

α2δ1 is not essential for EC coupling, but its absence alters properties of the Ca2+ transient

In agreement with Obermair et al. (1), we find that the α2δ1 DHPR subunit is not needed for skeletal-type EC coupling since there was no difference between α2δ1-deficient and wt myotubes in either the magnitude or the activation kinetics of the Ca2+ transient elicited by electrical or KCl depolarization in nominally Ca2+-free buffer (7 μM). However, during sustained depolarization in Ca2+-containing (2 mM) medium, the duration of Ca2+ transients in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes was reduced ∼5-fold compared to wt myotubes, despite similar sized SR Ca2+ stores, as indicated by caffeine responses. Two observations support the idea that this reduced duration in α2δ1 knockdown cells is a consequence of a loss of Ca2+ entry via ECCE. First, measurements of Mn2+ quench indicate that ECCE is greatly reduced in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes. Second, the duration of Ca2+ transients in wt myotubes is decreased fivefold when the external medium is made nominally Ca2+-free (Mg2+ increased to 3 mM), whereas this manipulation has no effect on the duration of the Ca2+ transient in α2δ1 knockdown cells. Although these results point to the importance of Ca2+ entry via ECCE for maintaining Ca2+ transients during prolonged depolarization, two limitations should be mentioned. First, removal of external Ca2+ would eliminate all sources of Ca2+ entry (not just that via ECCE). Second, removal of external Ca2+ might be expected to cause the voltage sensor for EC coupling to inactivate more rapidly (41,42). However, if either of these represented major mechanisms whereby Ca2+ removal caused a reduced duration of the Ca2+ transient in wt myotubes, it would not explain why Ca2+ removal had essentially no effect on α2δ1 knockdown cells.

α2δ1 is essential for physiologically engaging ECCE but not SOCE

In cells treated with TG, there was no difference in the kinetics or magnitude of the refilling response between α2δ1 DHPR knockdown and wt myotubes, showing that the absence of the α2δ1 subunit has no detectable effect on SOCE. Interestingly, when another set of myotubes from the same myoblast clones were depolarized with 40 mM KCl concurrently with the addition of 2 mM Ca2+ in the external medium, there was a striking difference between the two cell types. As expected (5), wt cells had a rapid Ca2+ transient with an even faster rise time than was seen with the addition of Ca2+ alone (5,43–45). α2δ1-deficient cells, on the other hand, showed no Ca2+ entry response at all during the KCl depolarization but did show a rate of cation entry similar to the rate of the SOCE transient when the KCl was removed. This result suggests that the mechanism behind the rapid decline in the Ca2+ transient during a 30 s KCl exposure or trains of 20 Hz electrical stimuli in α2δ1 knockdown myotubes was either a marked reduction or a complete absence of ECCE. In addition these data directly demonstrate and confirm the suggestions by others that SOCE is significantly inhibited by depolarization (46–48).

The results of our studies using Mn2+ quench of fura-2 fluorescence clearly confirm that that α2δ1 is an essential regulator of physiologic ECCE in skeletal myotubes and the degree of the dysfunction depends on 1), the nature of the depolarizing trigger (electrical trains versus [K+]), and, importantly, 2), the conformation of RyR1. From our results, it appears that if the RyR1 Ca2+ release channel is in or is placed into a conformational state different from the state found at rest in the cell (e.g., with the conformational state induced by certain RyR1 mutations or ryanodine), the effect of the absence of α2δ1 on ECCE can be partially overcome. This observation makes it unlikely that the absence of α2δ1 has either negatively influenced the expression or targeting of the ECCE channel to the surface membrane. Presumably the reason that ECCE is not completely abolished in α2δ1-deficient myotubes during electrical stimulation is that at a fairly low frequency of stimulation the voltage sensor has the opportunity to reset itself between individual stimuli. It is possible that if the stimulus frequency were raised higher than 20 Hz the reduction in the rate of Mn2+ entry would be more profound. This would suggest that the physiological engagement of ECCE may be most significant under conditions of extreme activity and that changes in the efficiency of Ca2+ entry during depolarization may be a factor in the processes leading to muscle fatigue.

In conclusion, the evidence gained from these studies confirms the previously defined role of the α2δ1 DHPR subunit as the particle needed to stabilize the CaV1.1 channel in the slowly activating state. Further it provides conclusive evidence that the α2δ1 subunit is not the particle that forms tetrads in freeze fracture studies of DHPRs in the surface membrane. Most importantly, it demonstrates that in addition to its previously defined role, the α2δ1 subunit also plays an important role in the three-way interaction of the DHPR complex, RyR1, and ECCE channels during normal EC coupling. However, unlike the CaV1.1, the role of the α2δ1 subunit in coordinating ECCE is important but not essential, as the absence of α2δ1 can be partially overcome by repriming the voltage sensor and almost completely overcome when the RyR1 assumes a conformation that enhances ECCE.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of Dr. Claudio F. Perez and James Fessenden (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston; Dr. Fessenden's current address is Boston Biomedical Research Institute, Watertown, MA) for their technical assistance in the initial troubleshooting of the Ca2+ imaging studies.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health P01-AR17605 to P.D.A., I.N.P., K.G.B., and C.F.A. and R01-NS24444 to K.G.B.

M. P. Gach's present address is Dept. of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Institute of Pediatrics, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland.

Editor: Jian Yang.

References

- 1.Nakai, J., R. T. Dirksen, H. T. Nguyen, I. N. Pessah, K. G. Beam, and P. D. Allen. 1996. Enhanced dihydropyridine receptor channel activity in the presence of ryanodine receptor. Nature. 380:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabner, M., R. T. Dirksen, N. Suda, and K. G. Beam. 1999. The II–III loop of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor is responsible for the bi-directional coupling with the ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21913–21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takekura, H., L. Bennett, T. Tanabe, K. G. Beam, and C. Franzini-Armstrong. 1994. Restoration of junctional tetrads in dysgenic myotubes by dihydropyridine receptor cDNA. Biophys. J. 67:793–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurne, A. M., J. J. O'Brien, D. Wingrove, G. Cherednichenko, P. D. Allen, K. G. Beam, and I. N. Pessah. 2005. Ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1) mutations C4958S and C4961S reveal excitation-coupled calcium entry (ECCE) is independent of sarcoplasmic reticulum store depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 280:36994–37004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherednichenko, G., A. M. Hurne, J. D. Fessenden, E. H. Lee, P. D. Allen, K. G. Beam, and I. N. Pessah. 2004. Conformational activation of Ca2+ entry by depolarization of skeletal myotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:15793–15798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandow, A. 1952. Excitation-contraction coupling in muscular response. Yale J. Biol. Med. 25:176–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi, C. P., and A. M. Shanes. 1959. Calcium influx in skeletal muscle at rest, during activity, and during potassium contracture. J. Gen. Physiol. 42:803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank, G. B. 1958. Inward movement of calcium as a link between electrical and mechanical events in contraction. Nature. 182:1800–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong, C. M., F. M. Bezanilla, and P. Horowicz. 1972. Twitches in the presence of ethylene glycol bis(-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetracetic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 267:605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorkovic, H. 1962. Potassium contracture and calcium influx in frog's skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 202:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank, G. B. 1960. Effects of changes in extracellular calcium concentration on the potassium-induced contracture of frog's skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 151:518–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherednichenko, G., C. W. Ward, W. Feng, E. Cabrales, L. Michaelson, M. Samso, J. R. Lopez, P. D. Allen, and I. N. Pessah. 2008. Enhanced excitation-coupled calcium entry (ECCE) in myotubes expressing malignant hyperthermia mutation R163C is attenuated by dantrolene. Mol. Pharmacol. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Arikkath, J., C. C. Chen, C. Ahern, V. Allamand, J. D. Flanagan, R. Coronado, R. G. Gregg, and K. P. Campbell. 2003. Gamma 1 subunit interactions within the skeletal muscle L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beurg, M., M. Sukhareva, C. A. Ahern, M. W. Conklin, E. Perez-Reyes, P. A. Powers, R. G. Gregg, and R. Coronado. 1999. Differential regulation of skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ current and excitation-contraction coupling by the dihydropyridine receptor beta subunit. Biophys. J. 76:1744–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beurg, M., M. Sukhareva, C. Strube, P. A. Powers, R. G. Gregg, and R. Coronado. 1997. Recovery of Ca2+ current, charge movements, and Ca2+ transients in myotubes deficient in dihydropyridine receptor beta 1 subunit transfected with beta 1 cDNA. Biophys. J. 73:807–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregg, R. G., A. Messing, C. Strube, M. Beurg, R. Moss, M. Behan, M. Sukhareva, S. Haynes, J. A. Powell, R. Coronado, and P. A. Powers. 1996. Absence of the beta subunit (cchb1) of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor alters expression of the alpha 1 subunit and eliminates excitation-contraction coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:13961–13966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knudson, C. M., N. Chaudhari, A. H. Sharp, J. A. Powell, K. G. Beam, and K. P. Campbell. 1989. Specific absence of the alpha 1 subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor in mice with muscular dysgenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1345–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell, J. A., and D. M. Fambrough. 1973. Electrical properties of normal and dysgenic mouse skeletal muscle in culture. J. Cell. Physiol. 82:21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanabe, T., K. G. Beam, J. A. Powell, and S. Numa. 1988. Restoration of excitation-contraction coupling and slow calcium current in dysgenic muscle by dihydropyridine receptor complementary DNA. Nature. 336:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schredelseker, J., V. Di Biase, G. J. Obermair, E. T. Felder, B. E. Flucher, C. Franzini-Armstrong, and M. Grabner. 2005. The beta 1a subunit is essential for the assembly of dihydropyridine-receptor arrays in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:17219–17224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freise, D., B. Held, U. Wissenbach, A. Pfeifer, C. Trost, N. Himmerkus, U. Schweig, M. Freichel, M. Biel, F. Hofmann, M. Hoth, and V. Flockerzi. 2000. Absence of the gamma subunit of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor increases L-type Ca2+ currents and alters channel inactivation properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14476–14481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catterall, W. A. 1995. Structure and function of voltage-gated ion channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:493–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obermair, G. J., G. Kugler, S. Baumgartner, P. Tuluc, M. Grabner, and B. E. Flucher. 2005. The Ca2+ channel alpha2delta-1 subunit determines Ca2+ current kinetics in skeletal muscle but not targeting of alpha1S or excitation-contraction coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 280:2229–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, E. H., G. Cherednichenko, I. N. Pessah, and P. D. Allen. 2006. Functional coupling between TRPC3 and RyR1 regulates the expressions of key triadic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 281:10042–10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore, R. A., H. Nguyen, J. Galceran, I. N. Pessah, and P. D. Allen. 1998. A transgenic myogenic cell line lacking ryanodine receptor protein for homologous expression studies: reconstitution of Ry1R protein and function. J. Cell Biol. 140:843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plouffe, D. A., and M. Belosevic. 2006. Antibodies that recognize alpha- and beta-tubulin inhibit in vitro growth of the fish parasite Trypanosoma danilewskyi, Laveran and Mesnil, 1904. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 30:685–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Protasi, F., C. Franzini-Armstrong, and P. D. Allen. 1998. Role of ryanodine receptors in the assembly of calcium release units in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 140:831–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Protasi, F., H. Takekura, Y. Wang, S. R. Chen, G. Meissner, P. D. Allen, and C. Franzini-Armstrong. 2000. RYR1 and RYR3 have different roles in the assembly of calcium release units of skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 79:2494–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia, D. E., A. Cavalie, and H. D. Lux. 1994. Enhancement of voltage-gated Ca2+ currents induced by daily stimulation of hippocampal neurons with glutamate. J. Neurosci. 14:545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia, J., and K. G. Beam. 1994. Measurement of calcium transients and slow calcium current in myotubes. J. Gen. Physiol. 103:107–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, T., T. A. Ta, I. N. Pessah, and P. D. Allen. 2003. Functional defects in six ryanodine receptor isoform-1 (RyR1) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and their impact on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25722–25730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clementi, E., H. Scheer, D. Zacchetti, C. Fasolato, T. Pozzan, and J. Meldolesi. 1992. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx. Two independently regulated mechanisms of influx stimulation coexist in neurosecretory PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267:2164–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fessenden, J. D., Y. Wang, R. A. Moore, S. R. Chen, P. D. Allen, and I. N. Pessah. 2000. Divergent functional properties of ryanodine receptor types 1 and 3 expressed in a myogenic cell line. Biophys. J. 79:2509–2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton, G. M., and R. Medzhitov. 2002. Retroviral delivery of small interfering RNA into primary cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:14943–14945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuck, S., A. Manninen, M. Honsho, J. Fullekrug, and K. Simons. 2004. Generation of single and double knockdowns in polarized epithelial cells by retrovirus-mediated RNA interference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:4912–4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flucher, B. E., J. L. Phillips, and J. A. Powell. 1991. Dihydropyridine receptor alpha subunits in normal and dysgenic muscle in vitro: expression of alpha 1 is required for proper targeting and distribution of alpha 2. J. Cell Biol. 115:1345–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avila, G., and R. T. Dirksen. 2000. Functional impact of the ryanodine receptor on the skeletal muscle L-type Ca(2+) channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franzini-Armstrong, C. 2004. Functional implications of RyR-DHPR relationships in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biol. Res. 37:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Block, B. A., T. Imagawa, K. P. Campbell, and C. Franzini-Armstrong. 1988. Structural evidence for direct interaction between the molecular components of the transverse tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum junction in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 107:2587–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paolini, C., F. Protasi, and C. Franzini-Armstrong. 2004. The relative position of RyR feet and DHPR tetrads in skeletal muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 342:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brum, G., R. Fitts, G. Pizarro, and E. Rios. 1988. Voltage sensors of the frog skeletal muscle membrane require calcium to function in excitation-contraction coupling. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 398:475–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizarro, G., R. Fitts, I. Uribe, and E. Rios. 1989. The voltage sensor of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Ion dependence and selectivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 94:405–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutierrez-Martin, Y., F. J. Martin-Romero, and F. Henao. 2005. Store-operated calcium entry in differentiated C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1711:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurebayashi, N., and Y. Ogawa. 2001. Depletion of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum stimulates Ca2+ entry into mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 533:185–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weigl, L., A. Zidar, R. Gscheidlinger, A. Karel, and M. Hohenegger. 2003. Store operated Ca2+ influx by selective depletion of ryanodine sensitive Ca2+ pools in primary human skeletal muscle cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 367:353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong, Z., F. Hong, A. Olschewski, J. A. Cabrera, A. Varghese, D. P. Nelson, and E. K. Weir. 2006. Role of store-operated calcium channels and calcium sensitization in normoxic contraction of the ductus arteriosus. Circulation. 114:1372–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khoo, C., J. Helm, H. B. Choi, S. U. Kim, and J. G. McLarnon. 2001. Inhibition of store-operated Ca(2+) influx by acidic extracellular pH in cultured human microglia. Glia. 36:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu, Y. J., E. Vieira, and E. Gylfe. 2004. A store-operated mechanism determines the activity of the electrically excitable glucagon-secreting pancreatic alpha-cell. Cell Calcium. 35:357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]