Abstract

Recognition of peptide antigen by T cells involves coordinated movement of T cell receptors (TCRs) along with other costimulatory and signaling molecules. The spatially organized configurations that result are collectively referred to as the immunological synapse. Experimental investigation of the role of spatial organization in TCR signaling has been facilitated by the use of nanopatterned-supported membranes to direct TCR into alternative patterns. Here we study the mechanism by which substrate structures redirect TCR transport. Using a flow-tracking algorithm, the ensemble of TCR clusters within each cell was tracked during synapse formation under various constraint geometries. Shortly after initial cluster formation, a coordinated centripetal flow of ∼20 nm/s develops. Clusters that encounter substrate-imposed constraint are deflected and move parallel to the constraint at speeds that scale with the relative angle of motion to the preferred centripetal direction. TCR transport is driven by actin polymerization, and the distribution of F-actin was imaged at various time points during the synapse formation process. At early time points, there is no significant effect on actin distribution produced by substrate constraints. At later time points, modest differences were observed. These data are consistent with a frictional model of TCR coupling to cytoskeletal flow, which allows slip. Implications of this model regarding spatial sorting of cell-surface molecules are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

In many cellular processes such as migration, mitosis, and synaptogenesis, cell-surface molecules reorganize over micron length scales to form spatial patterns correlated with specific cellular outcomes (1,2). This phenomenon is particularly striking in the recognition of antigenic peptide by T cells, which entails the coordinated movement of T cell receptor (TCR) and other molecules, including the integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) (3–5). During T cell activation, TCRs engage their ligand, major histocompatibility complex II proteins displaying antigenic peptide (pMHC), whereas LFA-1 binds to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (6). TCR/pMHC complexes nucleate the formation of microclusters containing TCR and an entourage of other costimulatory and signaling molecules including ZAP70, SLP76, and LAT (7,8). These kinase and adaptor molecules cotranslocate with TCR for at least some of the journey toward the cell center (8), and are thought to help stabilize microclusters through extensive protein-protein interactions (9,10). The mechanism of TCR translocation is not well understood, but it appears to be an active process dominated by cytoskeletal factors (3,11–14). The periphery of the immunological synapse is characterized by lamellipodial movement driven by actin polymerization (15,16). Retrograde actin flow is characteristic of lamellipodia, and radial lamellipodia are predicted to generate a centripetal flow of actin (17). T cell engagement and spreading, as well as microcluster formation and centripetal motion, require actin polymerization (7,13). The distribution of actin at the synapse is dynamic and actively regulated through a host of proteins downstream of TCR (12,18). Altered spatial organization of synaptic proteins directly affects downstream signaling, implying that spatial reorganization of the TCR and associated signaling molecules serve as an active regulatory mechanism (19–21).

Hybrid interfaces between live cells and engineered substrates facilitate both the manipulation and visualization of receptor movement on the cell surface (22–24). In hybrid experiments, cells interact with synthetic surfaces through cognate ligands that have been incorporated into a supported lipid membrane. Supported membranes are laterally fluid and thus allow these ligands, along with their corresponding receptors on the T cell surface, to move and assemble into active signaling complexes. Solid-state structures on the substrate can restrict this motion, and provide a means to redirect protein movement and assembly inside the living cell. Nonnative configurations impact signaling downstream of surface receptors. Importantly, substrate patterns influence the localization of signaling machinery within the cell solely through their interactions with receptors on the cell surface.

Physically preventing TCR microclusters from localizing to the center of the synapse with nanofabricated constraints alters TCR phosphorylation and intracellular calcium levels (21). Previous studies combining micropatterning and cells have exclusively examined static configurations of cellular machinery (22,25). The mechanism by which structures on the substrate alter the distribution and movement of protein complexes on the engaged living cell is not well understood (see Fig. 1, b and c). Here, we offer what to our knowledge is the first dynamic portrait of cell-surface molecule rearrangement by passive substrate constraint. TCR microclusters translocating toward the cell center move conformally to obstacles on the underlying substrate, despite no direct interaction with the constraints. Cluster formation is unaffected by patterned constraints, and TCR clusters do not stick to barriers. F-actin distributions are somewhat flattened across the cell face, but actin does not accumulate at barriers. This observation confirms the utility of substrate patterning as a technique for investigating dynamic cell-surface molecular reorganizations and suggests a mechanism of TCR transport based on frictional or viscous coupling to a cortical actin flow.

FIGURE 1.

Experimental schematic. (a) Lipid bilayers displaying mobile pMHC and ICAM-1 are formed on substrates patterned with molecular mazes. Mazes comprise 100 nm thick, 5.5nm high chrome features, with 1.5–2 μm long lines separated by 1.5–2 μm gaps; alternating lines are spaced 1.5–2 μm apart. Synapse formation was imaged by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, restricting the illumination to a 100 nm layer above the coverslip. TCR is labeled with a fluorescently tagged antibody fragment. Maze experiments were designed to elucidate the mechanism of synaptic repatterning by nanofabricated constraints such as in b and c. TCR microcluster formation at early time points (b) is not altered by constraints on the substrate, but at late time points TCR microclusters are reorganized and trapped on the side of the constraint nearest the cell center (marked with a red ×). Mazes permit the visualization of TCR-constraint interaction without irreversible trapping of the TCR in grid corners.

METHODS

Cell culture

AND CD4+ T cell blasts were prepared by stimulation of splenocytes from first generation AND × B10.Br transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with 1–2 μM moth cytochrome c (88–103) peptide. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Carlsbald, CA), 100 μM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 100 μM essential amino acids (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD), 50 mM sodium bicarbonate, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 48 and 96 h with 20U/ml IL-2 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and used on days 5–7. Cells were starved of IL-2 for 48 h before experiments.

Lipid-anchored proteins

Glycophosphatidyl inositol (GPI) linked IEk MHC (without peptide) and ICAM-1 were expressed in Chinese hamster ovary and baby hamster kidney cells, purified, and reconstituted into proteoliposomes as described (3). Supported membranes consisted primarily of dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine. GPI-ICAM-1 and GPI-IEk were used at densities of 100/μm2 and 50/μm2, respectively. Peptide was loaded into the empty IEk by incubating supported bilayers overnight with 50 μM total peptide at pH 4.5, followed by blocking for 1 h with a 5% casein solution in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2.

Pattern fabrication

Coverslips patterned with chromium mazes and grids were produced as described (21) in the University of California, Berkeley, Microfabrication facility. Mazes were patterned with 1.5–2 μm lines separated by 1.5–2 μm spaces, with adjacent lines separated by 1.5–2 μm. The line width was 100–200 nm, and patterns were 5.5 nm high. Before deposition of supported membranes, each substrate was etched in piranha solution (3:1 H2SO4/H2O2), rinsed extensively with H2O, and dried under nitrogen.

Imaging

Before imaging, cells were stained at 4°C for 20 min with the nonblocking anti-TCR Fab H57 (10 μg/ml) labeled with AlexaFluor 488 or 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For live-cell experiments, cells were then injected under isotonic conditions in imaging buffer (1× Hepes-buffered saline with 1% human serum albumin, 1 mM Ca2+, and 2 mM Mg2+, pH 7.3) into a temperature-clamped (37°C) flow cell and imaged immediately. For fixed-cell experiments, cells were allowed to interact with the bilayer for the noted time and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% casein (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with 1.5 μM FITC-phalloidin (Invitrogen). Microscopy was performed using a Nikon TE-2000E inverted scope and a 100× 1.45 NA objective. Cells were illuminated in total internal reflection mode using the 488 nm line from an Argon laser and the 568 line from an Ar/Kr mixed gas laser (both SpectraPhysics, Mountain View, CA). Images were obtained using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and a Cascade 512B EMCCD camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ).

Tracking

All particle tracking and data analysis was performed using custom software written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Particles were identified as local maxima from time series of single cells. Images were first convolved with a low pass filter of the same spatial dimension as the point spread function (PSF), then local maxima were identified across PSF-size neighborhoods. Identified objects were compared to the local background; particles not significantly brighter than the local background were discarded (26). Particle positions were then further refined by a least-squares fit of a Gaussian intensity distribution to the pixel values. Objects were linked into tracks using a neural network-based algorithm that exploited local flow information to bias the search for linked particles (27). Particle intensities were calculated by summing pixel intensities over a circular region the size of one PSF centered on the particle location. Radial velocities were calculated by first manually choosing the origin of the polar coordinate system to lie at the cell center, then calculating particle velocities using only the radial component of each particle position.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To determine the mechanism of synapse remodeling by substrate-imposed constraints, cells were imaged during synapse formation using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (see Fig. 1). AND T cell blasts were stained with the nonblocking anti-TCR Fab H57 and injected into a closed flow cell (37°C), where they settled onto supported lipid bilayers displaying mobile pMHC and ICAM-1. The synaptic face was imaged every 4–5 s for 300–600 s using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, ensuring that only membrane-associated structures within ∼100 nm of the glass interface were visible. Bilayers were formed on substrates patterned with molecular mazes composed of alternating dashed lines of 100 nm wide, 5.5 nm high chromium, with gap and line spacing of 1.5–2 μm. These molecular mazes are well suited to study the dynamics of TCR because microclusters are not permanently trapped by maze features, permitting long range movement of cell surface molecules. Conversely, grids and other closed patterns, such as those used for the F-actin experiments described below, are better suited to fixed-cell experiments because they trap microclusters at defined locations.

Representative cells undergoing activation on patterned and plain substrates are shown in Fig. 2 (see also movies S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Material). Nanopatterned chromium constraints on the underlying glass support alter the trajectories of TCR clusters during synapse formation (Fig. 2 b) compared to trajectories on unmodified substrates (Fig. 2 a). From 0 to ∼30 s, the cell spreads on the surface and clusters of TCR nucleate and grow with little inward movement (see Fig. 3). TCR clusters on nanopatterned substrates nucleate at random locations, identically to cells on unpatterned substrates. After ∼30 s, an inward translocation of TCR clusters occurs. The T cell establishes a geometry naturally described by a polar coordinate system with the origin at the synapse center (see Methods). Measurements of cluster movement reveal an average radial speed of 20 ± 8 nm/s, similar to that reported previously (8,13). This transport lasts for 2–3 min, after which the large clusters remain static whereas smaller clusters of TCR continue to stream in from the cell periphery, as has been reported (7,8,13) (see also Fig. 3). TCR microclusters nucleate and grow during the period of contact area expansion and initiate movement only after the spreading process has stopped (see Fig. 3). This suggests that the actin flow that is required for microcluster translocation is only initiated after the spreading process is completed. Individual TCR tracks show the same features as ensemble observations (Fig. S1; see also movie S3).

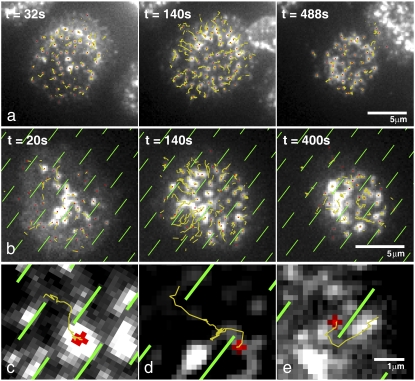

FIGURE 2.

Molecular mazes redirect TCR motion. (a) A T cell forming an immunological synapse on an unpatterned bilayer. Initial contact with the bilayer induces T cell receptor TCR clustering across the face of the cell, which is followed by a contraction phase. After contraction, a relatively stationary phase occurs where large clusters are fixed and subthreshold clusters continue to stream in from the periphery. At the acquisition rate required for particle tracking, cells typically don't form strong central accumulations of TCR because fluorescent tags are bleached during transport. Formation of central TCR accumulations was confirmed by visualizing cells just out of the tracking region of interest. Track lines are truncated at 15 frames previous to the frame shown. (b) Synapse formation on a supported lipid bilayer patterned with chromium fences (fences are outlined in green to aid the eye). The motion of TCR clusters is diverted by underlying chromium features. Clusters can sometimes be trapped by bilayer defects and not make it to the center, such as at 8 o'clock and 2 o'clock in this cell. (c–e)Example tracks show the effect of barriers on TCR translocation. The final position of the object is shown in red. For videos, see the Supplementary Material.

FIGURE 3.

Mean velocity and intensity of microclusters in a typical cell. After the T cell contacts the bilayer, there is an initial period of rapid microcluster nucleation and growth with negligible microcluster movement (light gray). After ∼30s, there is a period of rapid contraction during which TCRs translocate to the cell center (dark gray), followed by a relatively stationary mature phase (medium gray). TCR microcluster radial velocities from ∼50 microclusters in a single cell were averaged across each frame (dashed), then smoothed with a 5 frame windowed average (solid). Mean microcluster intensity in each frame was computed by summing the intensity of the pixels in each microcluster and averaging over clusters. Microclusters initiate movement only after the spreading process has stopped, suggesting that centripetal cortical actin flow begins only after spreading is completed. These observations are recapitulated in analyses of individual tracks (see Fig. S1).

The motion of TCR is redirected by barriers, but TCR microclusters can successfully navigate the molecular maze. Centripetally translating TCR clusters that encounter chromium lines move conformally to the underlying constraint (Fig. 2 b and c–e). Clusters do not stick to barriers but remain mobile, even when confronted with perpendicular lines, and can escape from contact with the barriers (Fig. 2 d). Overall synapse shape was mildly altered by constraint geometry. TCR clusters were not observed to cross the barriers, despite the individual TCR-pMHC half-life of ∼15 s (28). It is clear that some members of each TCR cluster, which contain ∼100 TCR (7), remain bound to their membrane associated ligand at all times, and that interactions between TCRs in the microclusters are sufficient to prevent barrier crossing. Moreover, proximity to barriers evidently does not affect the binding activity of bilayer-associated proteins. T cells plated onto patterned substrates displaying empty MHC or MHC displaying nonactivating peptide did not form microclusters, indicating that maze features do not nonspecifically induce synapse formation (21). In addition, cells plated on patterned bilayers displaying empty MHC displayed no TCR accumulation at barriers, confirming that TCR and other cell surface molecules do not directly interact with constraints (see Fig. S2).

Microcluster speeds are affected by interactions with maze features (Fig. 4). Microclusters interacting with the diffusion barriers were defined as being within 500 nm of the chromium lines, on the side opposite the cell center (Fig. 4 A, in red). The full-length tracks to which these microclusters belonged were selected automatically and microcluster speeds were averaged (Fig. 4 B). Microclusters associated with maze features were slower, on average, than free microclusters (Fig. 4 C and D). The speed change depends on the relative angle of the preferred centripetal (i.e., toward the center of the cell body) TCR direction and the angle of the underlying constraint, as can be seen in the limiting cases in Fig. 4 E. Clusters moving parallel to maze lines are not significantly slowed, whereas clusters encountering perpendicular maze lines are halted except for random, diffusive motion along the constraint. Intermediate angles slow the movement of TCR. Thus the speed of the TCR is not significantly affected by drag along the constraint boundary.

FIGURE 4.

TCR clusters are slowed by maze features. (A) In each frame, TCR microclusters within 500 nm of a fence line opposite the cell center were automatically selected (positions shown in red). Tracks to which these fence-associated clusters belonged were then selected; cluster positions from full-length tracks are shown in green. All TCR microcluster positions from the entire movie are shown in blue. (B) The fence-associated tracks are shown in line form, colored cyan when within 500 nm of a fence line and yellow when outside 500 nm. Red dots indicate the end of a track. (C) Microclusters are slowed by grids. Microcluster speeds for fence-associated and free intervals were calculated for each track and averaged for each cell. Bars show mean and standard deviation of cell means (n = 7, p < .001). (D) The speed distribution of free and maze-associated particles. (E) Speed slow-down is angle dependent. Clusters that encounter perpendicular maze features do not cross over and diffuse along the obstacle. Clusters encountering maze features at an angle to the preferred centripetal flow slow down. This slowing is geometrical, rather than drag-related, as clusters moving parallel to maze features are not significantly slowed. Bars represent mean and standard deviation of at least three tracks (pperpendicular = 0.009, pacute = 0.0003, pparallel = 0.8).

The effect of synapse repatterning on cortical F-actin was examined. In this case, it is advantageous to use grid geometry to define the location of TCR clusters, as this permits controlled examination of the integrated effect of altered TCR mobility on actin. Since maze structures only temporarily redirect TCR clusters, effects on actin in this case would be transient and therefore difficult to visualize in fixed cell experiments. T cells labeled with anti-TCR Fab were allowed to interact with bilayers for 2 or 5 min then fixed and stained with FITC-phalloidin (Fig. 5). Cells were imaged in green (F-actin) and red (TCR) channels using dual-color total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Thus, only structures within ∼200 nm of the synaptic face are illuminated. F-actin distributions were characterized by averaging normalized line scans across the center of the synapse. At early time points on plain substrates(Fig. 5 A), phalloidin intensity is enriched in a distal ring associated with cell spreading (29). At later time points (5 min), the area defined by the central accumulation of TCR lies in the center of a cloud of cortical F-actin surrounded by a lamellipodial ring. The central cloud is similar to the focal accumulation of actin reported in cell-cell conjugates (12,30). On gridded substrates at early and late time points, TCR clusters are trapped at the corners of the grid (Fig. 5, B and D. At 2 min, the distal, ring-shaped distribution of F-actin is similar to that of cells on constraint-free substrates, indicating that F-actin distributions at early time points are dominated by cell spreading. At 5 min, the distribution of F-actin is flattened compared to the unconstrained cell, but line scans retain the major features of a central region of enrichment and a lamellipodial ring. The flattened distribution is likely a secondary effect related to actin polymerization induced downstream of the dispersed microclusters. There is no significant effect on the distribution of F-actin near the grid lines. Inhibition of F-actin polymerization with latrunculin A halts microcluster translocation (Fig. S3 and (13)), but TCR clusters still diffuse slowly (Fig. S4) at a rate similar to clusters that have encountered perpendicular maze features.

FIGURE 5.

Actin localization on gridded substrates. T cells labeled with red anti-TCR antibodies were stimulated with plain and gridded bilayers and fixed at the indicated time points. Grids were used instead of maze substrates because they reveal the integrated effect of altered TCR mobility on actin patterns by fixing the TCR in a defined location. Fixed cells were stained for F-actin with FITC-phalloidin and imaged by dual-color total internal reflection microscopy, restricting the illumination volume to a 200 nm thick layer above the glass-water interface. Ten pixel wide line scans across the synaptic face were averaged across cells to determine the distribution of F-actin. (A and B) On both nongridded and gridded substrates, T cells in the immature synapse phase display a distal ring-shaped accumulation of F-actin associated with cell spreading (29) (A, n = 20; B, n = 17). TCR clusters in the nongridded cell have formed but not yet coalesced into a central accumulation. In the gridded substrate, TCR has not yet fully localized to the centripetal corners of grid squares, and some grid squares have multiple clusters of TCR. (C) T cells that have formed a mature synapse display a central accumulation of F-actin that colocalizes with TCR. This central accumulation is surrounded by a ring of lamellipodial F-actin (n = 36). (D) Cells synapsing on gridded substrates have a flatter distribution of F-actin across the cell face, but on average display a vestige of the central accumulation surrounded by a lamellipodial ring (n = 27) found in cells on ungridded substrates. No significant accumulation of F-actin at grid lines is visible.

These data imply a mechanism of TCR transport where TCR clusters are coupled to centripetal cortical actin flow (see Fig. 6). TCR microclusters nucleate and grow before moving (see Fig. 3), suggesting that translocation depends on exceeding a cluster size threshold that either initiates inward actin flow or regulates the coupling of TCR clusters to that flow. Microclusters were occasionally observed to exhibit diffusive motion during synapse formation, both when constrained by a perpendicular maze feature and when free. These results would seem to reject a model of microcluster translocation based on size exclusion or a long-range attractive interaction (31) because clusters do not coalesce on the side of barriers facing the cell center. Our data is consistent with a frictional model of TCR coupling to actin flow, in which polymerization of cortical actin drives TCR via a linkage that allows slip, like a clutch (32,33). Though we cannot rule out a stick-slip mechanism, in which the TCR cluster is either tightly associated with the actin or fully disconnected from it, this is unlikely. There are hundreds of TCRs per microcluster, and so potentially hundreds of possible links to the cytoskeleton that would all need to be broken simultaneously for the slip phase of a stick-slip process. More reasonable is a model in which many transient links, which form and break out of phase with each other, collectively produce a frictional coupling force between the TCR cluster and the cytoskeleton. Alternatively, TCR clusters could be viscously coupled to other actin-associated membrane proteins or lipids. The cytoskeletal network itself may be able to deform and reassemble (34), giving rise to an effective viscous drag on objects moving against this flow. It is possible that the TCR cluster breaks off small pieces of the cytoskeleton to move against the flow, rather than directly rupturing TCR-actin binding events. If TCR were driven by a stable linkage to a molecular motor, the speed of TCR microclusters would not be significantly altered by interaction with maze constraints because the motor would reorient and move at speed. If TCR were stably linked to actin filaments, then navigating the maze would require large-scale reorganization of the actin mesh leading to buildup at the maze features, which is not seen in the F-actin stain. This model suggests a mechanism for spatially sorting proteins based on the relative strengths of their coupling to a single driving force, actin flow. In this scenario, proteins coupled more strongly to the cytoskeletal flow would be able to displace less strongly coupled proteins, resulting in a radial sorting pattern.

FIGURE 6.

Frictional model of the mechanism of TCR translocation. Clusters of TCR containing hundreds of monomers are propelled by transient linkage to a prevailing centripetal actin flow. Even if the link between individual TCRs and actin is very weak, clusters of TCR are still, on average, linked to the cytoskeleton.

CONCLUSION

The importance of spatial localization in the regulation of signaling molecules is striking in the immunological synapse. Altering the localization of cell-surface molecules affects their activity. In this article, we have presented quantitative single-particle tracking results that provide what to our knowledge is the first dynamic portrait of repatterned immunological synapse formation and demonstrate the mechanism by which constraint of the motion of pMHC alters the localization of TCR. These results imply a mechanism of TCR translocation based on a frictional or viscous coupling to actin flow that allows slip. Significantly, this observation suggests a mechanism for spatially sorting T cell surface molecules that only relies on their relative coupling strength to actin flow. The combination of controlled physical perturbation through nanostructure patterning with quantitative image analysis enables a degree of mechanical study inside living T cell synapses not previously possible.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. B. Forstner, B. Rossenova, Ñ. Hartman, J. P. Hickey, and R. Varma.

A.L.D. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Editor: Arup Chakraborty.

References

- 1.Akins, M. R., and T. Biederer. 2006. Cell-cell interactions in synaptogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krummel, M. F., and I. Macara. 2006. Maintenance and modulation of T cell polarity. Nat. Immunol. 7:1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grakoui, A., S. K. Bromley, C. Sumen, M. M. Davis, A. S. Shaw, P. M. Allen, and M. L. Dustin. 1999. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 285:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss, W. C., D. J. Irvine, M. M. Davis, and M. F. Krummel. 2002. Quantifying signaling-induced reorientation of T cell receptors during immunological synapse formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:15024–15029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krummel, M. F., M. D. Sjaastad, C. Wulfing, and M. M. Davis. 2000. Differential clustering of CD4 and CD3 zeta during T cell recognition. Science. 289:1349–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krogsgaard, M., and M. M. Davis. 2005. How T cells ‘see’ antigen. Nat. Immunol. 6:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campi, G., R. Varma, and M. L. Dustin. 2005. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J. Exp. Med. 202:1031–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokosuka, T., K. Sakata-Sogawa, W. Kobayashi, M. Hiroshima, A. Hashimoto-Tane, M. Tokunaga, M. L. Dustin, and T. Saito. 2005. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat. Immunol. 6:1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunnell, S. C., A. L. Singer, D. I. Hong, B. H. Jacque, M. S. Jordan, M. C. Seminario, V. A. Barr, G. A. Koretzky, and L. E. Samelson. 2006. Persistence of cooperatively stabilized signaling clusters drives T-cell activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:7155–7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglass, A. D., and R. D. Vale. 2005. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 121:937–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wulfing, C., and M. M. Davis. 1998. A receptor/cytoskeletal movement triggered by costimulation during T cell activation. Science. 282:2266–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tskvitaria-Fuller, I., A. L. Rozelle, H. L. Yin, and C. Wulfing. 2003. Regulation of sustained actin dynamics by the TCR and costimulation as a mechanism of receptor localization. J. Immunol. 171:2287–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varma, R., G. Campi, T. Yokosuka, T. Saito, and M. L. Dustin. 2006. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 25:117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wulfing, C., M. D. Sjaastad, and M. M. Davis. 1998. Visualizing the dynamics of T cell activation: Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 migrates rapidly to the T cell/B cell interface and acts to sustain calcium levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:6302–6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Döbereiner, H. G., B. J. Dubin-Thaler, J. M. Hofman, H. S. Xenias, T. N. Sims, G. Giannone, M. L. Dustin, C. H. Wiggins, and M. P. Sheetz. 2006. Lateral membrane waves constitute a universal dynamic pattern of motile cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97:038102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sims, T. N., T. J. Soos, H. S. Xenias, B. Dubin-Thaler, J. M. Hofman, J. C. Waite, T. O. Cameron, V. K. Thomas, R. Varma, C. H. Wiggins, M. P. Sheetz, D. R. Littman, and M. L. Dustin. 2007. Opposing effects of PKC theta and WASp on symmetry breaking and relocation of the immunological synapse. Cell. 129:773–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher, G. W., P. A. Conrad, R. L. Debiasio, and D. L. Taylor. 1988. Centripetal transport of cytoplasm, actin, and the cell-surface in lamellipodia of fibroblasts. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 11:235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billadeau, D. D., J. C. Nolz, and T. S. Gomez. 2007. Regulation of T-cell activation by the cytoskeleton. Nature Rev. Immunol. 7:131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doh, J., and D. J. Irvine. 2006. Immunological synapse arrays: patterned protein surfaces that modulate immunological synapse structure formation in T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:5700–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng, S.-Y., M. Liu, and M. L. Dustin. 2005. CD80 cytoplasmic domain controls localization of CD28, CTLA-4, and protein kinase C{theta} in the immunological synapse. J. Immunol. 175:7829–7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mossman, K. D., G. Campi, J. T. Groves, and M. L. Dustin. 2005. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science. 310:1191–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, C. S., M. Mrksich, S. Huang, G. M. Whitesides, and D. E. Ingber. 1997. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 276:1425–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groves, J. T., and M. L. Dustin. 2003. Supported planar bilayers in studies on immune cell adhesion and communication. J. Immunol. Methods. 278:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, K. B., S. J. Park, C. A. Mirkin, J. C. Smith, and M. Mrksich. 2002. Protein nanoarrays generated by dip-pen nanolithography. Science. 295:1702–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu, M., D. Holowka, H. G. Craighead, and B. Baird. 2004. Visualization of plasma membrane compartmentalization with patterned lipid bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:13798–13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponti, A., P. Vallotton, W. C. Salmon, C. M. Waterman-Storer, and G. Danuser. 2003. Computational analysis of F-actin turnover in cortical actin meshworks using fluorescent speckle microscopy. Biophys. J. 84:3336–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labonte, G. 2000. On a neural network that performs an enhanced nearest-neighbour matching. Pattern Anal. Appl. 3:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis, M. M., J. J. Boniface, Z. Reich, D. Lyons, J. Hampl, B. Arden, and Y. H. Chien. 1998. Ligand recognition by alpha beta T cell receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:523–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunnell, S. C., V. Kapoor, R. P. Trible, W. G. Zhang, and L. E. Samelson. 2001. Dynamic actin polymerization drives T cell receptor-induced spreading: a role for the signal transduction adaptor LAT. Immunity. 14:315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki, J., S. Yamasaki, J. Wu, G. A. Koretzky, and T. Saito. 2007. The actin cloud induced by LFA-1-mediated outside-in signals lowers the threshold for T-cell activation. Blood. 109:168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Figge, M. T., and M. Meyer-Hermann. 2006. Geometrically repatterned immunological synapses uncover formation mechanisms. Plos Computational Biology. 2:e171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown, C. M., B. Hebert, D. L. Kolin, J. Zareno, L. Whitmore, A. R. Horwitz, and P. W. Wiseman. 2006. Probing the integrin-actin linkage using high-resolution protein velocity mapping. J. Cell Sci. 119:5204–5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu, K., L. Ji, K. T. Applegate, G. Danuser, and C. M. Waterman-Stirer. 2007. Differential transmission of actin motion within focal adhesions. Science. 315:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Footer, M. J., J. W. J. Kerssemakers, J. A. Theriot, and M. Dogterom. 2007. Direct measurement of force generation by actin filament polymerization using an optical trap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:2181–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]