Abstract

Objectives

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is a chronic tic disorder associated with comorbid psychopathology, including obsessionality, affective instability and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Evidence linking GTS with schizophrenia-like symptoms is limited and equivocal, despite a common putative substrate involving dopaminergic dysfunction within frontostriatal circuits. The aim of this study was to quantify the prevalence of schizotypal traits in GTS and to detail the relationship between schizotypy and comorbid psychopathology.

Materials and methods

A total of 102 subjects with GTS were evaluated using the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire and standardized neurological and psychiatric rating scales. The predictive interrelation between schizotypy, tic-related symptoms and psychiatric comorbidities was investigated using correlation and multiple regression analyses.

Results

In our clinical population, 15% of the subjects were diagnosed with the schizotypal personality disorder according to the DSM-IV criteria. The strongest predictors of schizotypy were obsessionality and anxiety ratings. The presence of multiple psychiatric comorbidities correlated positively with schizotypy scores.

Conclusions

Schizotypal traits are relatively common in patients with GTS, and reflect the presence of comorbid psychopathology, related to the anxiety spectrum. In particular, our preliminary results are consistent with a shared neurochemical substrate for the mechanisms underpinning tic expression, obsessionality and specific schizotypal traits.

Keywords: Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, tics, schizotypy, obsessive–compulsive disorder

Introduction

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is a childhood-onset neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by multiple motor tics and one or more phonic tics that usually remain throughout life following a waxing and waning course, but tend to reduce in severity after the age of 18 (1). Tics typically refer to repetitive, involuntary, sudden jerky movements, such as blinking or head-nodding or noises, such as sniffing or throat-clearing. GTS is also often associated with complex behaviours (including forced touching, self-injurious behaviour, copro-, echo- and paliphenomena) and affective, obsessional and/or attentional psychopathology (1, 2). In the largest investigation to date (a multicentre study of 3500 individuals from 22 countries), Freeman et al. (3) reported that only 12% of the patients had GTS with no psychiatric comorbidity (‘pure GTS’). Among the most commonly reported problems are obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and other anxiety disorders, affective disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and substance abuse (1-3). Although neurodevelopmental frontostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction is implicated in the aetiopathology of both GTS and schizophrenia (4), GTS is diagnostically and prognostically distinct from schizophrenia, with only a chance association (1).

However, it has been observed that a proportion of GTS patients reports mild ‘schizophrenia-like’ symptoms, including paranoid ideation, feelings of presence or persecution and control phenomena (4-6). In a series of 95 GTS patients from North Dakota, 12% were identified as having such schizophrenia-like symptoms (7). Notably, none of the patients fully met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. A virtually identical prevalence (11%) is reported by Comings and Comings (8). In their study, the most common feature displayed by GTS patients was a sense that people were observing or spying on them. These authors suggest a relationship with self-conscious feelings about expressing motor and vocal tics, although the degree of the misperception was often out of proportion to tic-severity, and the feeling of being watched often persisted in those for whom medication produced a complete cessation of tics. They also found significantly higher prevalence of related paranoid and persecutory ideation (8).

With respect to personality traits, a controlled study of 29 subjects with GTS showed that GTS patients score significantly higher on the schizophrenia scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory than matched controls (9). The authors concluded that GTS patients ‘entertain occasional bizarre perceptions’. In another controlled study by Robertson et al. (10) on 39 GTS patients and 34 healthy volunteers, schizotypal or schizoid personality disorders were diagnosed in five cases (13%) and in no controls (0%), according to the SCID interview (11) and the Dowson Self Report Scale (12).

Taken together, these preliminary findings suggest a possible, yet under-recognized, expression of schizotypal symptoms in patients with GTS. We therefore quantified and characterized schizotypal symptomatology in 102 adult subjects with GTS, examining associations between schizotypy expression and severity of tics/GTS-related comorbid psychopathology. The exploration of the relationship between GTS and schizotypy clearly sheds further light on the multifaceted clinical phenomenology of GTS, as recent quantitative analyses of symptoms and comorbidities, using techniques such as the principal component factor analysis, endorse clinical suspicions that there is more than one GTS phenotype, rather than the unitary one as suggested by psychiatric nosography (13, 14). Furthermore, a better understanding of the relationship between GTS and schizotypal symptoms could be relevant to the choice of using antipsychotic drugs as first-line treatment options in selected cases.

Methods

Patients

A total of 102 patients attending the Tourette clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London, were recruited over a 10-month period. All patients fulfilled the DSM-IV-TR criteria for GTS. Exclusion criteria included English as a second language and age below 16 years. Informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to enrolment in the study, for which ethics approval was granted by the local committee, via the Central Office for Research Ethics Committees protocol.

Quantification of symptom phenomenology

Each subject underwent a comprehensive clinical interview using the National Hospital Interview Schedule (NHIS) for GTS, a psychometric instrument with established inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity (15). The NHIS is a detailed semi-structured interview schedule, which includes personal and family histories and demographic details. For the diagnosis of various GTS-associated behavioural disorders, such as OCD and ADHD, the NHIS was originally developed by incorporating the relevant questions and items from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule to yield a diagnosis as per DSM-III-R, and was then updated based on the DSM-IV criteria. Moreover, it replicates the Family Psychiatric History Interview, where the subject is asked about the medical and psychiatric history of each and every First Degree Relative by name. One of the advantages of NHIS is that GTS-associated behaviours are assessed as to whether or not they have ever been present, rather than existing currently.

The severity of core symptoms of GTS in each patient was assessed using the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) (16). Depressive, anxiety and obsessional symptoms were indexed in each subject using the following standardized psychiatric rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (17), the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y1 and Y2) (18), and the questionnaire form of the Leyton Obsessional Inventory (LOI), respectively (19).

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (20) was used to diagnose schizotypal personality disorder, whilst the presence of schizotypal symptoms was investigated using the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) (21). The SPQ is a 74-item self-report scale modelled on the DSM-III-R criteria for schizotypal personality disorder and containing subscales for the nine schizotypal traits: ideas of reference; excessive social anxiety; odd beliefs/magical thinking; unusual perceptual experiences; odd or eccentric behaviour; no close friends; odd speech; constricted affect; and suspiciousness/paranoia (22). Converging evidence suggests that schizotypy scores, when subjected to principal component analysis, show a three-factor structure that mirrors the three clinical syndromes found in schizophrenia (23). Therefore, in this paper we analysed the SPQ total score and the subscores for these three schizotypal dimensions, namely:

a Cognitive-Perceptual factor, which includes the traits of odd beliefs/magical thinking, ideas of reference, unusual perceptual experiences, and suspiciousness/paranoia, and is analogous to the clinical reality distortion syndrome;

a Disorganized factor, which includes the traits of odd or eccentric behaviour and odd speech, and is analogous to the clinical disorganized syndrome; and,

an Interpersonal factor, which includes the traits of excessive social anxiety, no close friends, constricted affect, and suspiciousness/paranoia, and mirrors aspects of the clinical negative syndrome.

The psychometric scales were administered in the same sequence to all subjects.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 12.0 for Windows; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2000. First, we parametrized the relationship between schizotypy scores and clinical variables, including tic severity (YGTSS scores), and psychopathology ratings (BDI score for depression; LOI score for obsessionality; STAI Y1 and Y2 scores for state and trait anxiety, respectively). The association of each variable with schizotypy scores has been analysed using the linear regression analysis, which allows adjustment for general confounders (age, age at onset of GTS, gender, family history of GTS, duration of disease, and antipsychotic medication); the variables which correlated significantly to SPQ scores after adjustment for general confounding entered a multiple variable regression model.

Second, based on the observation that patients with ‘pure GTS’ have less behavioural problems than those with psychiatric comorbidity (1, 24), we split our clinical population into ‘pure GTS’ (tics only) vs ‘GTS-plus’ (i.e. GTS in addition to comorbid psychopathology). The two subgroups were compared with respect to the SPQ scorings by using two-tailed t-tests for independent samples with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

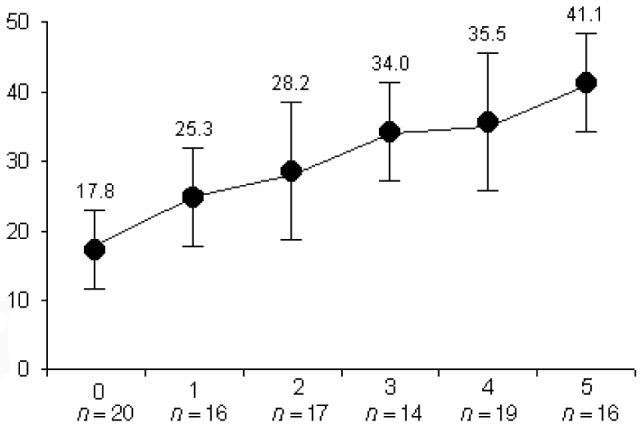

Finally, subjects included within the ‘GTS-plus’ group were given a comorbidity score according to the number of associated clinical psychopathologies: OCD, other anxiety disorders, affective disorders, ADHD and substance abuse, each scored one point. Patients with ‘GTS only’ were given a comorbidity score of 0. Such comorbidity scores were plotted against total SPQ scores to investigate the overall influence of GTS-associated behavioural disorders on schizotypy expression.

Results

A total of 102 patients with GTS, aged 18–54 years (mean = 28.7; SD = 12.2) participated in this study. Seventy-nine patients (77%) were male, and 85 (83%) were right-handed. The mean age at the tic onset was 9 years (SD = 6) and the mean number of motor and vocal tics ever was 23 (SD = 14) and 6 (SD = 5), respectively. The mean total YGTSS score was 31.2 (range 13–49), indicative of moderate-to-marked severity. The main clinical characteristics, tic-related symptoms and comorbid psychopathologies (according to the DSM-IV criteria incorporated in the NHIS) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and psychiatric comorbidities of the GTS sample (n = 102).

| Family history of tics (n, %) | 71 (70) |

| Pre-/perinatal problems (n, %) | 22 (21) |

| YGTSS total score (m, SD) | 31.2 (9.1) |

| YGTSS motor tic score (m, SD) | 17.4 (11.3) |

| YGTSS vocal tic score (m, SD) | 7.2 (5.1) |

| Coprolalia (n, %) | 29 (28) |

| Copropraxia (n, %) | 18 (17) |

| Palilalia (n, %) | 38 (37) |

| Palipraxia (n, %) | 25 (24) |

| Echolalia (n, %) | 41 (40) |

| Echopraxia (n, %) | 44 (43) |

| SIB (n, %) | 37 (36) |

| Stuttering (n, %) | 29 (28) |

| Anxiety disorder (n, %) | 45 (44) |

| STAI-Y1 score (m, SD) | 48.5 (14.6) |

| STAI-Y2 score (m, SD) | 46.6 (13.2) |

| OCD (n, %) | 34 (33) |

| LOI score (m, SD) | 29.4 (12.9) |

| Affective disorder (n, %) | 31 (30) |

| BDI score (m, SD) | 10.2 (7.8) |

| ADHD (n, %) | 43 (42) |

| Substance abuse (n, %) | 16 (15) |

GTS, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome; YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; SIB, self-injurious behaviours; STAI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; LOI, Leyton Obsessional Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Fifteen subjects (15%) met the DSM-IV criteria for the schizotypal personality disorder. The total SPQ scores for the study sample ranged from 3 to 62 (mean = 30.64; SD = 14.8). SPQ subscale scores, expressed as mean (SD), were as follows: Disorganized 6.86 (4.3) (range 1–15); Cognitive-Perceptual 9.94 (7.64) (range 0–34); Interpersonal 15.14 (6.9) (range 1–29). The total SPQ scores were significantly higher (P < 0.01) than those reported in the largest representative samples available in the literature [data in Ref. (25)]. These authors tested the three-factor solution of the SPQ instrument in a community sample of 1201 male and female 23-year-old subjects, using the confirmatory factor analysis and model-fitting indices with psychopathology ratings, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, and the Antisocial Personality Disorder section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders). We found that both Disorganized and Interpersonal subscales scored significantly higher in GTS patients (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively), while the Cognitive-Perceptual factor showed no significant differences compared with normative healthy subjects.

According to the multiple regression analysis, the strongest predictor of schizotypy was obsessionality (P < 0.01), followed by state-and-trait anxiety (P < 0.05). Table 2 shows the best fit final multiple variable model.

Table 2. Best fit multiple variable regression model predicting SPQ scores.

| SPQ total | SPQ-CP | SPQ-I | SPQ-D | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (β) | P | 95% CI | t (β) | P | 95% CI | t (β) | P | 95% CI | t (β) | P | 95% CI | |

| YGTSS total | 2.20 | 0.037* | 0.04–0.66 | 1.49 | 0.088 | −0.04–0.16 | 1.91 | 0.061 | −0.02–0.33 | 7.83 | 0.002** | 0.59–0.97 |

| YGTSS motor tic | 2.16 | 0.030* | 0.03–0.59 | 1.69 | 0.064 | −0.03–0.12 | 1.62 | 0.073 | −0.04–0.21 | 5.54 | 0.004** | 0.38–0.85 |

| YGTSS vocal tic | 2.09 | 0.046* | 0.01–0.52 | 1.44 | 0.094 | −0.05–0.23 | 1.88 | 0.060 | −0.02–0.18 | 6.11 | 0.003** | 0.47–1.21 |

| STAI-Y1 | 4.61 | 0.007** | 0.20–0.88 | 1.92 | 0.058 | −0.01–0.08 | 5.47 | 0.004** | 0.41–1.20 | 2.14 | 0.026* | 0.03–0.54 |

| STAI-Y2 | 4.24 | 0.008** | 0.18–1.04 | 1.62 | 0.072 | −0.04–0.19 | 5.82 | 0.005** | 0.39–0.92 | 2.03 | 0.021* | 0.02–0.49 |

| LOI | 4.66 | 0.007** | 0.23–0.86 | 2.18 | 0.034* | 0.04–0.79 | 6.38 | 0.003** | 0.45–1.01 | 2.23 | 0.036* | 0.04–0.85 |

| BDI | 1.45 | 0.091 | −0.02–0.16 | 0.98 | 0.337 | −0.02–0.11 | 2.06 | 0.047* | 0.02–0.68 | 1.54 | 0.132 | −0.02–0.44 |

SPQ, Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire; CP, Cognitive-Perceptual dimension; I, Interpersonal dimension; D, Disorganized dimension; YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; STAI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; LOI, Leyton Obsessional Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

Significant differences (P < 0.01) were observed when comparing SPQ scores in patients with GTS only (n = 20) and patients with GTS and at least one psychiatric comorbidity according to the DSM-IV criteria, i.e. ‘GTS plus’ (n = 82). On an average, patients with ‘GTS plus’ scored higher than patients with uncomplicated GTS on total SPQ, and all three SPQ factors, in particular the Interpersonal dimension (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of SPQ scores in patients with uncomplicated GTS (‘GTS only’, n = 20) and patients with GTS and associated psychopathology (‘GTS plus’, n = 82).

| SPQ | GTS only (mean, SD) |

GTS plus (mean, SD) |

t | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 17.8 (6.3) | 32.1 (14.3) | 3.98 | 0.007** | 4.37–20.14 |

| CP | 6.8 (4.5) | 10.8 (4.8) | 2.83 | 0.026* | 1.74–9.72 |

| I | 9.1 (5.8) | 18.5 (7.1) | 4.35 | 0.003** | 5.33–11.82 |

| D | 4.9 (3.2) | 7.3 (4.7) | 2.11 | 0.048* | 0.02–4.37 |

GTS, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome; SPQ, Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire; CP, Cognitive-Perceptual dimension; I, Interpersonal dimension; D, Disorganized dimension.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

The comorbidity scores obtained by summating the associated psychiatric diagnoses were plotted against the total SPQ scores in Fig. 1, and demonstrated a clear positive correlation with schizotypy (R2 = 0.97).

Figure 1. Total SPQ scores (y axis) by number of psychiatric comorbidities (x axis) in the GTS sample (n = 102).

Discussion

The aim of this study was twofold: (i) to assess the prevalence of schizotypal traits; and (ii) to explore the relationship between schizotypal symptoms and GTS-related psychopathology in a large sample of adult patients with GTS. The first investigation of schizotypy dimensions in GTS patients demonstrates a relatively high prevalence of schizotypal experiences within this population, and highlights a close association between these symptoms and the presence of multiple comorbidities. Moreover, at a phenomenological level, our findings emphasize a proximal relationship between schizotypal symptoms and anxiety spectrum disorders, most strongly OCD.

Several studies report an association, present in a majority of the patients, between GTS and comorbid psychiatric disorders, including OCD, anxiety disorders, depression, ADHD and substance abuse [for a comprehensive review see Ref. (1)]. Surprisingly, despite a degree of overlap in the clinical features (e.g. echolalia, certain motor and obsessive–compulsive symptoms and responsiveness to pharmacological treatment with antidopaminergic agents), the general rates of comorbid psychotic illnesses appear to be low in GTS patients (26). In fact, much of the existing literature is based on isolated case reports of individuals with GTS and schizophrenia, and a paucity of comparisons of the clinical patterns of the two disorders. The established view is that schizophrenia in GTS is rare and likely to be associated by chance (1). To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first one to investigate associations between GTS and schizotypal traits using a validated psychometric instrument such as the SPQ (21).

Our results suggest that, among GTS patients attending our tertiary clinic, SPQ-derived schizotypal symptoms are common, particularly when compared with the normative samples of healthy subjects. Specifically, GTS seems to be associated with higher subscores on the Interpersonal and Disorganized schizotypy dimensions. Our finding that as a group, GTS patients did not score higher than normative samples on the more traditional psychotic symptoms included in the Cognitive-Perceptual schizotypal dimension, seems to corroborate this view. This is noteworthy, as the Cognitive-Perceptual factor most closely parallels Jaspers' concept of psychosis (27).

The vast majority of our sample (82%) presented with ‘GTS plus’, i.e. with a diagnosis of GTS and at least one comorbid psychiatric or behavioural disorder: this high prevalence of associated psychopathology replicates findings of previous studies (1, 3). Additionally, we demonstrate that GTS patients with anxious and obsessive–compulsive symptomatology are more likely to exhibit schizotypal personality traits. The higher prevalence of schizotypy in the ‘GTS plus’ subgroup compared to patients with GTS only is suggestive of an interplay between schizotypy and GTS-associated psychopathology, especially with respect to the Interpersonal dimension. The latter includes symptoms of social anxiety, isolation and negative self-referential ideation, which may also characterize patients with affective and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (28). On the other hand, the ‘ticcy’ component of schizotypy in GTS appears to be confined to the Disorganized dimension (bizarre behaviour and odd speech).

This study provides detailed insights into the phenomenological and possibly pathophysiological relationships between GTS and schizotypy. The magnitude of comorbidity with the presence of obsessional and anxiety symptoms is highlighted as the key predicting factor underlying this relationship (rather than tics per se). From a clinical perspective, the high correlation between the SPQ and the obsessionality scores may reflect a dependent interplay between GTS, OCD and schizotypy. Increased rates of obsessive–compulsive symptoms are reported in individuals with schizotypal personality traits (29, 30). OCD symptoms have been described in up to 30% of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (31) and in up to 80% of patients with GTS, depending on different categorization of obsessive–compulsive symptom severity (1). Conversely, studies have demonstrated schizotypal personality features among OCD patients in 28–50% of patients (29, 32). Moreover, patients suffering from both OCD and schizotypy exhibit a more deteriorative course and poorer prognosis than those with OCD alone. This subgroup of patients often requires different treatments, such as a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antipsychotic agents (29). Not surprisingly, the presence of schizotypal personality symptoms has been identified as a predictor of poor OCD treatment response in patients with GTS (33).

This study has its limitations: the role of the clinic as a tertiary referral centre may be relevant. It is possible that an individual with both GTS and schizotypal features is more likely to be referred to the clinic than an individual with GTS alone, and correspondingly GTS patients in our clinic may represent individuals with more severe GTS, anxiety and behavioural symptoms than non-referred GTS patients. In other words, our clinic population may be subject to substantial ascertainment or referral bias, a problem which is almost always present when highly selected populations are studied. Furthermore, psychosocial problems that arise from living with, and adapting to, the often stigmatizing tic disorder contribute to the severity of associated psychopathology (24, 26).

At a theoretical level it is plausible that GTS and schizotypy may share a common pathoaetiology, most likely in a dysregulation of striatal dopaminergic activity (34, 35). Quite recently, intriguing parallels in neuroanatomical abnormalities have been disclosed in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder and GTS. For example, a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study observed significantly smaller caudate volume in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder compared with control subjects (36). Similarly, Peterson et al. reported a 5% reduction in caudate volume in 154 GTS patients compared with healthy controls (37). These findings suggest common involvement of striatal or frontobasal circuits shared by schizotypy and GTS, and the same regions are implicated in OCD (38). However, it should not be underestimated that the interpretation of these findings needs special caution, as the results of imaging studies aimed at shedding light on the pathogenetic mechanisms of GTS and psychiatric comorbidities have been frequently contradictory and remain inconclusive [for a review see Ref. (35)].

In summary, our findings, which are robustly expressed within the population of GTS patients (as well as in comparisons with normative data), suggest that the expression of schizotypal symptoms in patients with GTS correlates with the presence of comorbid conditions (mainly obsessionality and anxiety), predicting more complex management issues. In particular, those treating GTS need to recognize and understand the significance of schizotypal symptoms in the context of associated behavioural problems such as OCD. Finally, putative common pathoaetiological substrates between GTS-related psychopathology and specific dimensions of schizotypy are proposed. Further research, including functional imaging studies, is needed to provide direct neurobiological validation to these insights into the complexity of the GTS phenotype.

Acknowledgements

A.E.C. is funded by Amedeo Avogadro University, Novara, Italy. H.D.C. is funded by the Wellcome Trust. The authors thank Dr Hilary Watt for statistical support.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

None.

References

- 1.Robertson MM. Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain. 2000;123:425–62. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eapen V, Fox-Hiley P, Banerjee S, et al. Clinical features and associated psychopathology in a Tourette syndrome cohort. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:255–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, et al. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:436–47. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller N, Riedel M, Zawta P, et al. Comorbidity of Tourette's syndrome and schizophrenia: biological and physiological parallels. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1245–52. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comings DE. Tourette syndrome and human behavior. Duarte, CA: Hope Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurlan R, Como PG, Miller B, et al. The behavioral spectrum of tic disorders: a community-based study. Neurology. 2002;59:414–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerbeshian J, Burd L. Are schizophreniform symptoms present in attenuated form in children with Tourette disorder and other developmental disorders? Can J Psychiatry. 1987;32:123–35. doi: 10.1177/070674378703200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comings DE, Comings BG. A controlled study of Tourette syndrome. IV. Obsessions, compulsions, and schizoid behaviors. Am J Hum Gen. 1987;41:782–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman HY, Mostofsky DI, Harrison RH. Psychological aspects of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:228–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198603)42:2<228::aid-jclp2270420202>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson MM, Banerjee S, Fox Hiley PJ, et al. Personality disorder and psychopathology in Tourette's syndrome: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:283–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R – Patient version. New York: Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowson JH. Assessment of DSM-III-R personality disorders, by self report questionnaire: the role of informants and a screening test for co-morbid personality disorders (STCPD) Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:344–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson MM, Cavanna AE. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a principal component factor analytic study of a large pedigree. Psychiatr Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328015b937. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathews CA, Jang KL, Herrera LD, et al. Tic symptom profiles in subjects with Tourette Syndrome from two genetically isolated populations. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson MM, Eapen V. The National Hospital Interview Schedule for the assessment of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and related behaviours. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res. 1996;6:203–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, et al. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–73. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“Self-evaluation Questionnaire”) Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snowdon JA. A comparison of written and postbox forms of the Leyton Obsessional Inventory. Psychol Med. 1980;10:165–70. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700039714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–64. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3th edn, revised) (DSM-III-R) Washington, DC: APA; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raine A, Reynolds C, Lencz T, et al. Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:191–201. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Packer LE. Social and educational resources for patients with Tourette syndrome. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:457–73. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds CA, Raine A, Mellingen K, et al. Three factor model of schizotypal personality: invariance across culture, gender, religious affiliation, family adversity, and psychopathology. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:603–18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coey BJ, Park KS. Behavioral and emotional aspects of Tourette syndrome. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:277–89. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaspers K. Allgemeine Psychopathologie [General Psychopathology] Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobin C, Blundell ML, Weiller F, Gavigan C, Haiman C, Karayiorgou M. Evidence of a schizotypy subtype in OCD. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poyurovsky M, Koran LM. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with schizotypy vs. schizophrenia with OCD: diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic implications. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suhr JA, Spitznagel MB, Gunstad J. An obsessive-compulsive subtype of schizotypy: evidence from a nonclinical sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:884–6. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243929.45895.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, et al. Occurrence and clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:60–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanley MA, Turner SM, Borden JW. Schizotypal features in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:511–8. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(90)90065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miguel EC, Gedanke Shavitt R, Ferrão YA, et al. How to treat OCD in patients with Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siever LJ, Davis KL. The pathophysiology of schizophrenia disorders: perspectives from the spectrum. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:398–413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer HS. Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:149–59. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitt JJ, McCarley RW, Dickey CC, et al. MRI study of caudate nucleus volume and its cognitive correlates in neuroleptic-naïve patients with schizotypal personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1190–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson BS, Thomas P, Kane MJ, et al. Basal ganglia volume in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:415–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saxena S, Brody AL, Schwartz JM, et al. Neuroimaging and frontal-subcortical circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173(suppl. 35):26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]