Abstract

The human DNA repair protein O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (hAGT) is an important source of resistance to some therapeutic alkylating agents and attempts to circumvent this resistance by the use of hAGT inhibitors have reached clinical trials. Several human polymorphisms in the MGMT gene that encodes hAGT have been described including L84F and the linked double alteration I143V/K178R. We have investigated the inactivation of these variants and the much rarer variant W65C by O6-benzylguanine, which is currently in clinical trials, and a number of other second generation hAGT inhibitors that contain folate derivatives (O4-benzylfolic acid, the 3' and 5' folate esters of O6-benzyl-2'-deoxyguanosine and the folic acid γ ester of O6-(p-hydroxymethyl)benzylguanine). The I143V/K178R variant was resistant to all of these compounds. The resistance was due solely to the I143V change. These results suggest that the frequency of the I143V/K178R variant among patients in the clinical trials with hAGT inhibitors and the correlation with response should be considered.

Keywords: Alkyltransferase, O6-benzylgunaine, polymorphisms, cancer chemotherapy, O4-benzylfolate, DNA repair

1. Introduction

DNA adducts at the O6-position of guanine are important for the antitumor action of a number of drugs including the methylating agents, temozolomide, procarbazine and dacarbazine, and the chloroethylating agents, BCNU and CCNU [1-4]. These adducts are repaired rapidly by the action of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (hAGT). This protein is therefore an important source of resistance to these agents. Compounds that inactivate hAGT and overcome this resistance in cultured cells and xenografts are currently in clinical trials.

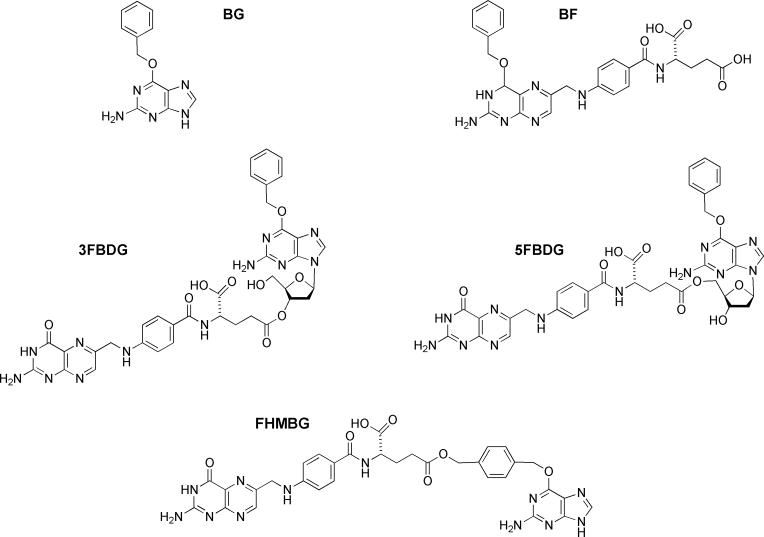

The inhibitors currently undergoing trials are O6-benzylguanine (BG) [4-6] and O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine (PaTrin2) [7, 8]. Despite some responses in the trials with BG, the lack of selectivity of the drug towards the tumor hAGT is likely to limit its effectiveness. Another concern is that alterations in hAGT causing resistance to BG (and presumably PaTrin2) arise very readily in laboratory studies [9-12]. These results have led to efforts to synthesize second-generation hAGT inhibitors that would be more potent, tumor specific and able to inactivate BG-resistant variants at doses achievable in the clinic. One promising approach has been to make folate derivatives of BG that would selectively be taken up into tumors by the folate carrier, a transport system known to be more active in many tumors than in normal cells. These efforts have led to the synthesis of O4-benzylfolic acid (BF), the 3' and 5' folate esters of O6-benzyl-2'-deoxyguanosine (3FBDG and 5FBDG, respectively) and the folic acid γ ester of O6-(p-hydroxymethyl)benzylguanine (FHMBG) [13, 14]. The structures of these compounds are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structures of inhibitors used

Several variants in the MGMT gene that encodes the hAGT protein, which affect the primary sequence of the protein, have been described. Variants W65C [15, 16], L84F [15-28], I143V/K178R [17-24, 27, 29-31] and G160R [29, 32] have been reported by multiple laboratories. These reports raise the possibility that there may be individual variation in response to hAGT inactivators. This possibility was strongly supported by the finding that a G160R variant was substantially resistant to BG [33]. However, subsequent studies have shown that the frequency of the G160R variant is very low ( >1%) [17, 29, 30, 34, 35]. Recently, it was reported that the I143V/K178R variant, which is much more common with a frequency of c. 24%, may be resistant to PaTrin-2 [24].

We therefore examined variants W65C, L84F and I143V/K178R for inactivation by BG and its folate derivatives described above.

2. Materials and Methods

2. 1. Materials

Primers were synthesized and purified by the Macromolecular Core Facility, Hershey Medical Center. E. coli XL1-blue bacterial strain, Pfu Turbo hot-start DNA polymerase, Pfu polymerase enzyme and Quick Change Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). DNA isolation kits and the pQE-30 plasmid were obtained from Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA). Restriction enzymes BamHI and KpnI were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Ampicillin, isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), hemocyanin, calf thymus DNA, and most other biochemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Talon Metal Affinity IMAC Resin was obtained from BD Bioscience Clontech (Palo Alto, CA), the Rapid DNA Ligation Kit and urea were purchased from Roche Diagnostic Corporation (Indianapolis, IN). Nitrocellulose filters (0.45μm) were obtained from Millipore (USA). Tobacco etch virus (Tev) protease was provided by Dr. J. M. Flanagan (Dept. of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine). BG [36], BF [13] and 3FBDG, 5FBDG and FHMBG [14] were synthesized as previously described.

2.2. Construction of pQE plasmids for expression of different hAGT variants

Plasmids for the production of C-terminal His6-tagged hAGT [37] and for the production of N-terminal His6-tagged hAGT [38], and the mutants L84F, I143V and I143V/K178R were prepared as described previously [39, 40]. Plasmids for the production of N-terminal His6-tagged W65C and K178R of hAGT were constructed from the template plasmids of pQE30-hAGT [38] with Quick Change Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers W65C-P1: 5'-d(CAGTGCACAGCCTGCCTGAATGCCTATTTC)-3' and W65C-P2: 5'-d(GAAATAGGCATTCAGGCAGGCTGTGCACTG)-3' and primers K178R-P1: 5'-d(CACCGGTTGGGGAGGCCAGGCTTGGGAGGG)-3' and K178R-P2: 5'-d(CCCTCCCAAGCCTGGCCTCCCCAACCGGTG)-3' were used to construct the W65C and K178R variants with N-terminal His6-tags. The mutated sites are shown in bold and underlined. All of the N-terminal His6-tagged hAGT proteins differ from the wild type by the addition of a terminal MRGS(H)6GS- to the protein [38]. The C-terminal His6-tagged hAGT have a (His)6 sequence replacing residues 202−207 [37].

Plasmids for the expression of wild type and I143V/K178R hAGT with a cleavable N-terminal His6-tagged hAGT in the PQE30 vector were constructed as follows by PCR using the pQE30-hAGT and pQE30-I143V/K178R as templates. The hAGT sequence was modified to form a tobacco etch virus (Tev) protease recognition site [41] using primer- 1 5'-d(GCACAGATGGATCCGAGAACCTGTACTTCCAATCCATGGACAAGGATTGTG)-3' as the sense primer and primer 2: 5'-d(GGATCTATCAACAGGAGTCC)-3' as anti-sense primer. The BamHI restriction site in primer 1 is underlined and Tev protease recognition site is shown in bold and italic. The PCR was carried out using Pfu polymerase under the conditions described previously [42]. The PCR product and plasmid vector were digested with BamHI and KpnI enzymes, the digested products were purified with Eppendorf Perfectprep Gel Cleanup kit of Brinkmann company (Westbury, NY), and the fragments containing the desired sequences were ligated into a pQE30 vector plasmid digested with the same enzymes to form pQE30-TevhAGT and pQE30-TevI143V/K178R. All constructed plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing carried out by the Macromolecular Core Facility, Hershey Medical Center. The resulting verified plasmids were used for protein expression and purification after transformation of XL-1 blue cells. The hAGT proteins produced from this vector after cleavage with Tev protease differ from the wild type by the addition of an N-terminal Ser residue.

2.3. Protein purification

The XL-1 blue cells containing pQE30-hAGT and variants or pQE30-TevhAGT and variants were cultured for protein expression and purification using Talon IMAC resin as previously described [42]. For pQE30-TevhAGT and pQE30-TevI143V/K178R, after the protein was dialyzed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT and 0.1 mM EDTA, the solution containing hAGT was concentrated with Centrion Ultracel YM-10 of Millipore corporation (Bedford, MA). His6-tagged Tev protease was then added (1:20 ratio) and digestion was carried out at 4°C for 12−16h. The digested protein mixture was then loaded into Talon IMAC resin and the flow-through collected [41]. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels.

2. 4. Inactivation of alkyltransferase activity by BG and other compounds

Appropriate amounts of hAGT and variants with or without His6-tag were incubated with different concentrations of hAGT inhibitors in 0.5 ml hAGT assay buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.6, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA and 50 μg hemocyanin for 30 min at 37°C. For assay in the presence of DNA, 10 μg calf thymus DNA was added to the buffer in place of the hemocyanin. The residual hAGT activity was then determined by method described previously [13]. A graph of the percentage of the hAGT activity remaining against inhibitor concentration was then plotted and the ED50 value representing the amount of inhibitor needed to produce a 50% loss of activity was calculated from the equation fitting the best fit curve using an exponential curve fitting program (KaleidaGraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA 19606].

3. Results

The effects of known polymorphic changes in hAGT sequence on the inactivation by BG and BF were initially studied using hAGT with an N-terminal His6-tag since the variants had previously been prepared using this construct. All of these proteins were purified to homogeneity and all of the variants had similar activity to wild type hAGT in the repair of methylated DNA in vitro (results not shown). As previously reported by others [43], the W65C protein was relatively unstable and was obtained in a lower yield.

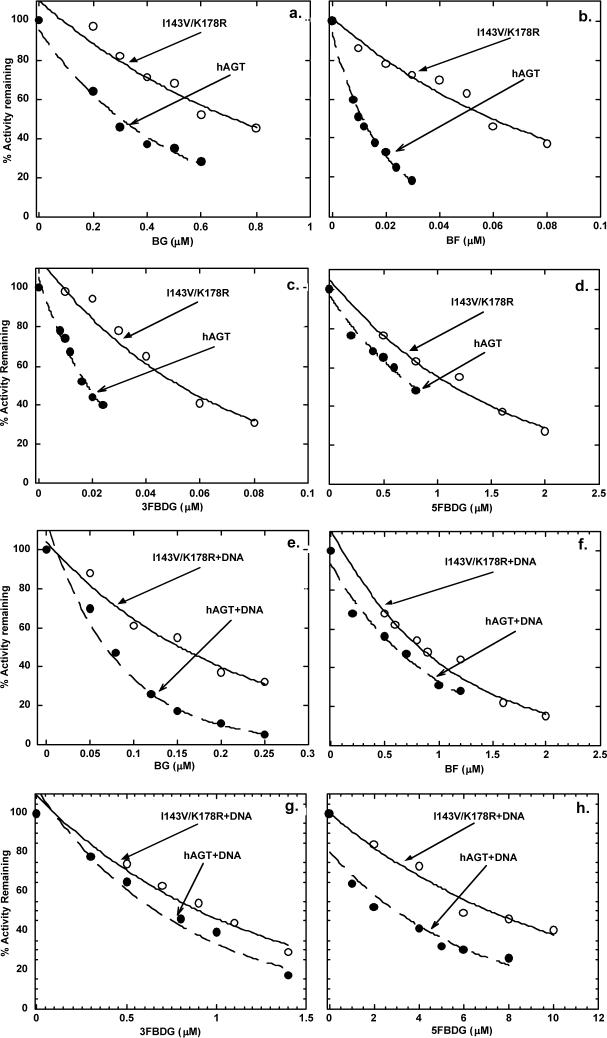

As shown in Fig. 2a and 2e, and summarized in Table 1, there was a small increase in the ED50 for BG with W65C and I143V/K178R but no change from wild type and L84F. This was seen in assays conducted in the absence (Fig. 2a) and presence of DNA (Fig. 2e) when, as previously reported [44], BG was a more potent inactivator.

Fig. 2.

Inactivation of N-(His)6-tagged hAGT and variants in the presence or absence of calf thymus DNA. The upper panels show the inhibition graphs in the absence of DNA. Results are shown for hAGT (filled circles), L84F (open circles), I143V/K178R (filled squares), and W65C (open squares) inactivated by: a, BG; b, BF; c, 3FBDG d, 5FBDG. The lower panels show the inhibition graphs in the presence of DNA. Results are shown for hAGT + DNA (filled circles), L84F + DNA (open circles), I143V/K178R + DNA (filled squares), and W65C+DNA (open squares) inactivated by: e, BG; f, BZ; g, 3FBDG; h, 5FBDG.

Table 1.

Inactivation of wild type hAGT and variants by BG and BF

| AGT used | ED50 (μM) for inhibitor shown | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BG | BF | |||

| +DNA | −DNA | +DNA | −DNA | |

| N-tag-hAGT | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.012 ± 0.002 |

| N-tag-I143V/K178R | 0.18 ± 0.01a | 0.55 ± 0.04b | 3.5 ± 0.2a | 0.034 ± 0.002a |

| N-tag-L84F | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.018 ± 0.003 |

| N-tag-W65C | 0.27 | 0.74 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 0.020 ± 0.004 |

| hAGT | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.012 ± 0.002 |

| I143V/K178R | 0.17 ± 0.02a | 0.68 ± 0.03a | 0.94 ± 0.03a | 0.053 ± 0.07a |

| C-tag-hAGT | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.40± 0.06 | 0.75±0.08 | 0.008± 0.006 |

ED50 values were calculated from graphs of the percentage of remaining hAGT activity against inhibitor concentration shown in Figs. 1 and 3. Experiments where an S. D. is shown were repeated 3−5 times and the mean shown. Other values are the mean of two experiments.

Significantly different from wild type hAGT, p<0.001

Significantly different from wild type hAGT, p<0.01

The I143V/K178R variant was clearly more resistant to inactivation by BF than wild type (Fig. 2b and 2f). This difference was also seen in the both the presence and the absence of DNA but BF, as previously reported [13], was much less active in the presence of DNA. The L84F and W65C variants were also slightly more resistant to BF but this difference was not statistically significant.

The ability of 3FBDG, 5FBDG and FHMBG to inactivate the polymorphic forms of hAGT was also studied (Fig. 2c, d, g and h) and Table 2. The I143V/K178R variant was significantly more resistant to inactivation by all of these compounds. The inactivation by 3FBDG and 5FBDG was less when DNA was present (Fig. 2g and 2h) but the difference between wild type and I143V/K178R was still highly significant.

Table 2.

Inactivation of wild type hAGT and variants by 3FBDG, 5FBDG and FHMBG

| AGT used | ED50 (μM) for inhibitor shown | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3FBDG | 5FBDG | FHMBG | ||||

| +DNA | −DNA | +DNA | −DNA | +DNA | −DNA | |

| N-tag-hAGT | 2.90 ± 0.05 | 0.009 ± 0.004 | 5.35 ± 0.13 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.54 |

| N-tag-I143V/K178R | 3.82 ± 0.22b | 0.032 ± 0.008a | 8.62 ± 0.94a | 1.19 ± 0.06a | 0.48 ± 0.01a | 1.10 |

| N-tag-L84F | 3.35 | 0.011 | 5.44 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.45 |

| N-tag-W65C | 2.77 | 0.008 | 8.42 | 1.24 | 0.46 | 0.94 |

| hAGT | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.016 ± 0.002 | 3.06 ± 0.18 | 0.64 ± 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| I143V/K178R | 0.95 ± 0.02a | 0.048 ± 0.008a | 7.34 ± 0.62a | 1.25 ± 0.12a | 0.56 | 1.30 |

ED50 values were calculated as described in Table 1. Experiments where an S. D. is shown were repeated 3−5 times and the mean shown. Other values are the mean of two experiments.

Significantly different from wild type hAGT, p<0.001

Significantly different from wild type hAGT, p<0.01.

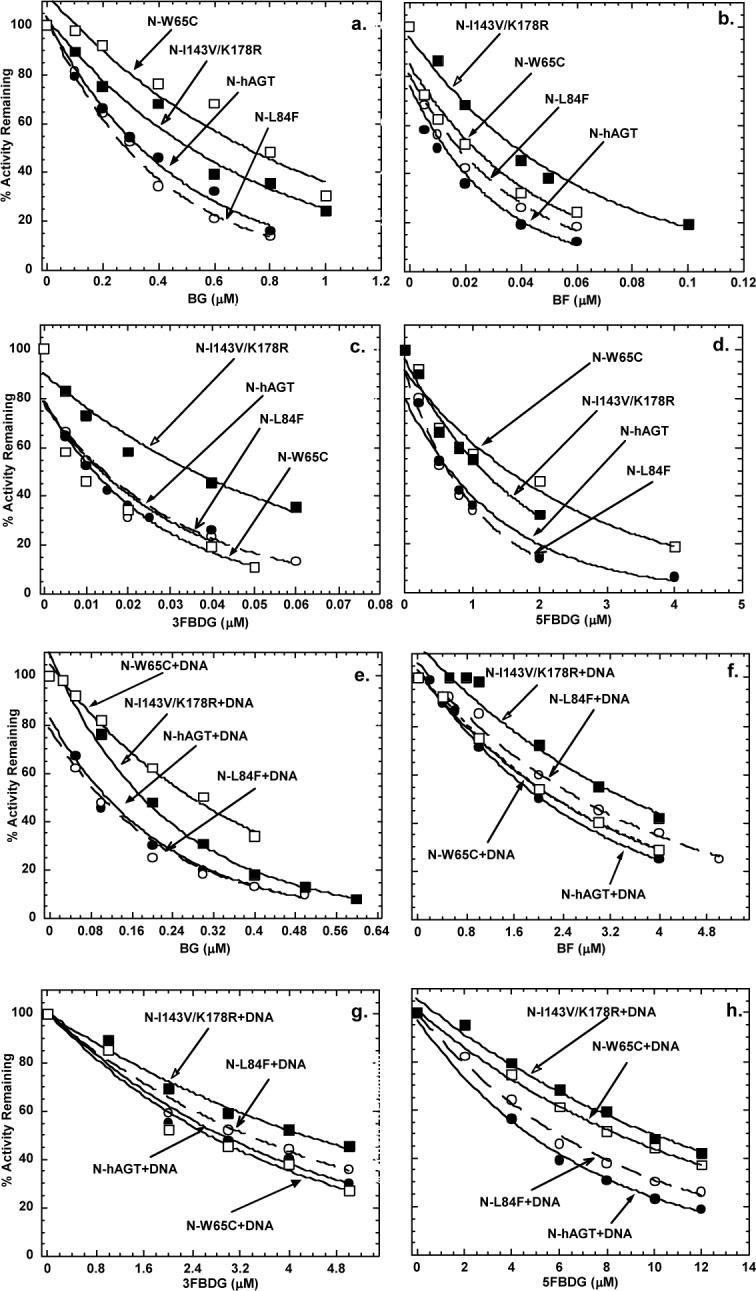

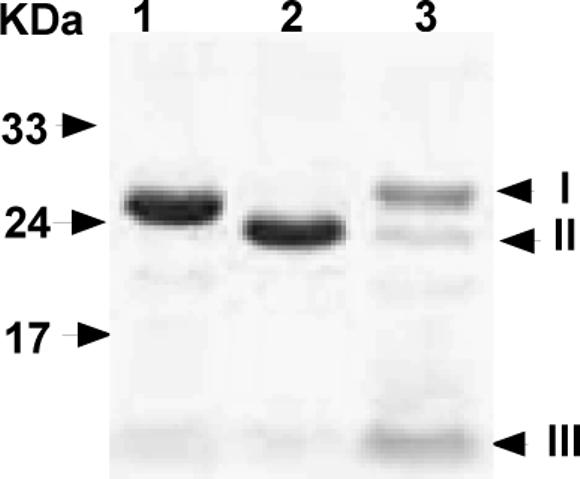

The ED50 value of 2.0 μM for the inactivation of N-terminal His6-tag wild type hAGT by BF in the presence of DNA found in this study was higher than that previously reported (ED50 of 0.47 μM) [13] but the previous study was carried out using hAGT with a C-terminal His6-tag. We therefore prepared both the wild type and the I143V/K178R variant, which showed the most extensive change in inactivation by BF, using a construct that contained a cleavable His6-tag and removed the additional sequence using Tev protease. The purity of resulting proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 3). There was no difference between the wild type and the I143V/K178R variant in activity for the repair of methylated DNA when the protein with either N- or C-terminal His6-tag or no tag was tested (results not shown). The difference in the inactivation by BG, BF, 3FBDG and 5FBDG was still seen with the protein from which the tag had been removed (Fig. 4 and Tables 1 and 2). The only major alteration in the results was that the ED50 values for BF, 3FBDG and 5FBDG in the presence of DNA were lower for both wild type and the I143V/K178R variant when the tag was removed. Thus, it appears that the addition of the amino terminal His6-tag alters the ability of hAGT to interact with folate derivatives in the presence of DNA but does not influence the ability of the I143V/K178R variant to reduce the sensitivity to inhibition. We re-examined the wild type hAGT with a C-terminal His6-tag and observed that the inactivation by BF resembled that seen with the protein with no tag (Table 1 bottom line).

Fig. 3.

Purity of hAGT. N-Tev-hAGT and hAGT were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described under Experimental procedures, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1: N-Tev-hAGT (with N-His6-tag and Tev recognition site). lane 2: hAGT (after removal of N-His6-Tag). Lane 3: Eluted proteins with elution buffer. The positions of pure proteins are indicated on the right side (I, Tev protease; II, hAGT; III, cut N-Tev His6-tag). Molecular markers shown on left side.

Fig. 4.

Inactivation of hAGT and I143V/K178R variant in the presence or absence of calf thymus DNA. The upper panels show the inhibition graphs in the absence of DNA. Results are shown for hAGT (filled circles), and I143V/K178R (open circles) inactivated by: a, BG; b, BF; c, 3FBDG; d, 5FBDG. The lower panels show the inhibition graphs in the presence of DNA. Results are shown for hAGT + DNA (filled circles) and I143V/K178R+DNA (open circles) inactivated by e: BG; f, BF, g; 3FBDG; h, 5FBDG.

The SNPS leading to the I143V and K178R changes are in almost perfect disequilibrium [17, 18, 24, 30] and it is highly likely that both changes occur in the protein derived from this gene. In order to examine the extent to which two linked alterations contribute to the resistance to inhibitors observed, N-terminal His6-tagged hAGT proteins with the individual mutations were produced separately and tested (Table 3). With all of the compounds examined, the ED50 value for the I143V mutant was higher than for the K178R mutant and the latter resembled wild type whereas the I143V gave result similar to the I143V/K178R variant. Thus, it appears that the resistance to these compounds is due to the presence of the Val residue replacing Ile.

Table 3.

Inactivation of I143V and K178R hAGT mutants

| Drugs | ED50(μM) | |||

| +DNA | −DNA | |||

| N-tag-I143V | N-tag-K178R | N-tag-I143V | N-tag-K178R | |

| BG | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.28 |

| BF | 3.20 | 1.80 | 0.038 | 0.013 |

| 3FBDG | 4.18 | 2.98 | 0.028 | 0.009 |

| 5FBDG | 8.86 | 6.04 | 1.08 | 0.42 |

| FHMBG | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.46 |

The I143V and K178R mutant proteins were prepared with an N-terminal His6-tag from the pQE30 vector. The ED50 value was calculated as described in Table 1. Each experiment was repeated twice.

4. Discussion

Polymorphisms in human DNA repair genes may have important implications in individual sensitivity to carcinogens and response to antitumor agents. Since hAGT activity is well established as a major factor in the response to alkylating agents, which are widely distributed environmental carcinogens and also common antitumor drugs, it is highly conceivable that variants of hAGT may have important effects. However, at present, these are not clearly established. There are a substantial number of epidemiological and biochemical reports on the properties of these variants (reviewed in [48]) but these do not provide a consistent picture with some studies showing increased risk of tumor development and others not [19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 31, 45-47]. This may be a consequence of the small sample size in most of these studies. Also, the W65C alteration is very rare and there are even fewer reports of G160R alteration. The two common alterations are L84F and I143V/K178R. Neither of these alterations appears to affect the ability of hAGT to repair O6-methylguanine adducts in DNA.

The purified L84F recombinant protein does not differ in activity from wild type hAGT in the repair of O6-methylguanine in vivo or in vitro or in the relative repair in vitro of O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine, an adduct formed by the tobacco specific nitrosamines [40, 43]. The lack of alteration in DNA repair ability for L84F is consistent with the fact that this is a conservative change of one hydrophobic amino acid side-chain for another at a position in the N-domain of hAGT, a significant distance away from the active site. The findings reported here that the L84F variant had little if any effect on the interaction with inhibitors is also consistent with the lack of change in the active site pocket.

The I143V/K178R form of hAGT appears to be potentially the most interesting polymorphic variant. The Ile143 is located in the active site pocket and is very close to the Cys145 acceptor site. However, this protein appears not to differ from wild type in the repair of methylated DNA [19, 24, 39]. This is not surprising since the position equivalent to Ile143 in hAGT is variable when sequences from a wide range of organisms are compared with the most common alteration being the presence of Val rather than Ile. This alteration occurs in the S. cerevisiae and B. subtilis AGTs that are known to be active. However, it is well established that there are striking species differences in the ability of AGTs to repair more bulky adducts [2, 49, 50]. The I143V/K178R hAGT was active in the repair of O6-n-butylguanine, O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine or BG when these were contained in oligodeoxynucleotides [39]. However, the repair of O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by this variant was less sensitive to sequence context than wild type or the L84F form [40]. These results indicate that the I143V substitution alters the geometry of the hAGT substrate-binding pocket to permit efficient repair of bulky O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine even when it is in conformations that may be poorly repaired by wild type hAGT.

Our results showing that the I143V/K178R form of hAGT is more resistant to inactivation by BG and benzyl folate derivatives can also be explained by steric alterations in the active site pocket region where these inhibitors must bind. The extent to which the alteration changes the sensitivity is greatest with the more potent inhibitors (3−4 fold). Models based on the crystal structure of hAGT and the S-benzyl form of the protein formed by reaction with BG show that the binding of BG is strongly influenced by a stacking interaction with Pro140 and forms hydrogen bonds with residues Tyr144, Val148 and Ser159 [51, 52]. The greater potency of BF and 3FBDG is likely to be due to additional interactions via the folate moiety. The alteration of Val for Ile143 in the binding pocket may cause subtle changes that affect these interactions. Our results are in agreement with a recent report that there was a small difference in the sensitivity to inactivation by PaTrin-2 when I143V/K178R and I143V variants were compared to wild type [24]. Although the increase in ED50 values were not calculated in these experiments there was 76% loss of activity with wild type and only 67% loss with the I143V alteration with 10 μM Patrin-2 suggesting that the alteration is similar in magnitude to that seen with BG.

Our results show that all of the alterations in response to inhibitors of the I143V/K178R variant was due to the I143V change which affects the binding pocket. This is consistent with the report of resistance of I143V to PaTrin-2 and with known structural data. hAGT can be truncated to end at position Leu176 without loss of activity [53] and the position of the K178R change is not in a conserved part of the protein and has no interaction with the active site in the crystal structure [51].

Our studies with the very rare W65C mutant suggest that this protein may also be slightly resistant to some of the inhibitors tested but not to 3FBDG or to BF. A more critical issue with this variant is likely to be the instability of the protein. The purified recombinant W65C protein was obtained in a much lower yield and was less stable when incubated in vitro. Previous studies have also observed a lowered activity and ability to protect from methylation damage compared to wild type when W65C was expressed in either bacteria or a mammalian cell line [43]. Thus, it is unlikely that W65C would provide resistance to therapeutic alkylating agents similar to that imparted by wild type hAGT. In contrast, previous studies with mutant G160R have shown that this alteration provides substantial resistance to BG in vitro (ED50 of 9 μM without DNA and 4 μM with DNA) and to the killing of cells by BCNU plus BG in culture [54]. However, numerous follow up studies have failed to confirm the frequency of about 15% that was reported for this G160R variant [32], and many studies failed to find any cases [17, 29, 30, 34, 35]. Thus, it is unlikely that either W65C or G160R will prove to be important in response to therapy in clinical trials.

In contrast, the I143V/K178R variant is quite common with a frequency of c. 24% (11−28%) in various studies [17-24, 27, 29-31], and it is active in protecting cells from alkylation damage. Even in individuals with one allele, the very strong selection pressure that is provided under conditions involving treatment with temozolomide or BCNU plus a hAGT inhibitor would select for cells in which a hAGT form resistant to an inhibitor was present. Therefore, determination of the frequency of the I143V/K178R variant and correlation with response in patient populations treated with such drugs would be advisable. It may also prove useful to design and examine potential new hAGT inactivators for improved ability to react with this hAGT variant.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Work in AEP's laboratory was supported by grants CA-018137 and CA-071976 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Abbreviations

- AGT

O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase

- hAGT

human AGT

- BG

O6-benzylguanine

- PaTrin-2

O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine

- BF

O4-benzylfolic acid

- 3FBDG

O6-benzyl-3'-O-(γ-folyl)-2'-deoxyguanosine

- 5FBDG

O6-benzyl-5'-O-(γ-folyl)-2'-deoxyguanosine

- FHMBG

O6-[4-[(γ-folyl)-oxymethyl]benzyl]guanine

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- Tev

tobacco etch virus.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dolan ME, Pegg AE. O6-Benzylguanine and its role in chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Res. 1997;3:837–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pegg AE. Repair of O6-alkylguanine by alkyltransferases. Mutation Res. 2000;462:83–100. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margison GP, Santibáñez-Koref MF. O6-Alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: role in carcinogenesis and chemotherapy. BioEssays. 2002;24:255–66. doi: 10.1002/bies.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerson SL. MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:296–307. doi: 10.1038/nrc1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinn JA, Desjardins A, Weingart J, Brem H, Dolan ME, Delaney SM, et al. Phase I trial of temozolomide plus O6-benzylguanine for patients with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7178–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren KE, Aikin AA, Libucha M, Widemann BC, Fox E, Packer RJ, et al. Phase I study of O6-benzylguanine and temozolomide administered daily for 5 days to pediatric patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7646–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middleton MR, Margison GP. Improvement of chemotherapy efficacy by inactivation of a DNA-repair pathway. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)00959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranson M, Middleton MR, Bridgewater J, Lee SM, Dawson M, Jowle D, et al. Lomeguatrib, a potent inhibitor of O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase: phase I safety, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic trial and evaluation in combination with temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1577–84. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacolod MD, Johnson SP, Pegg AE, Dolan ME, Moschel RC, Bullock NS, et al. Brain tumor cell lines resistant to O6-benzylguanine/1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosoure chemotherapy have O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase mutations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1127–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu-Welliver M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Isolation of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase mutants highly resistant to inactivation by O6-benzylguanine. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1936–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu-Welliver M, Pegg AE. Point mutations at multiple sites including highly conserved amino acids maintain activity but render O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase insensitive to O6-benzylguanine. Biochem J. 2000;347:519–26. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3470519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontes AM, Davis B, Encell L, Lingas K, Comas DT, Zago MA, et al. Differential competitive resistance to methylating versus chloroethylating agents among five O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferases in human hematopoietic cells. . Mol Cancer Therap. 2006;6:121–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson ME, Loktionova NA, Pegg AE, Moschel RC. 2-Amino-O4-benzylpteridine derivatives: potent inactivators of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3887–91. doi: 10.1021/jm049758+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savanmard S, Loktionova NA, Fang Q, Pauly GT, Pegg AE, Moschel RC. Inactivation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase by folate esters of O6-benzyl-2'-deoxyguanosine and of O6-[4-(hydroxymethyl)benzyl]guanine. J Med Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1021/jm0705859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otsuka M, Abe M, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Suzuki T. Polymorphism in the human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene detected by PCR-SSCP analysis. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:361–3. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abe M, Inoue R, Suzuki T. A convenient method for genotyping of human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase polymorphism. Jpn J Human Genet. 1997;42:425–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02766943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng C, Capasso H, Zhao Y, Wang L-D, Hong J-Y. Genetic polymorphism of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: identification of a missense variation in the active site region. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:81–7. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199902000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egyházi S, Platz A, Smoczynski K, Ringborg U. Novel O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase SNPs: a frequency comparison of pateients with familial melanoma and healthy individuals. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:408–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.9078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma S, Egyhazi S, Ueno T, Lindholm C, Kreklau EL, Stierner U, et al. O6-Methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase expression and gene polymorphisms in relation to chemotherapeutic response in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1517–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzesniak M, Butkiewicz D, Samojedny A, Chorazy M, Rusin M. Polymorphisms in TDG and MGMT genes - epidemiological and functional study in lung cancer patients from Poland. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:300–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WY, Olshan AF, Schwartz SM, Berndt SI, Chen C, Llaca V, et al. Selected genetic polymorphisms in MGMT, XRCC1, XPD, and XRCC3 and risk of head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1747–53. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchey JD, Huang WY, Chokkalingam AP, Gao YT, Deng J, Levine P, et al. Genetic variants of DNA repair genes and prostate cancer: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1703–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen J, Terry MB, Gammon MD, Gaudet MM, Teitelbaum SL, Eng SM, et al. MGMT genotype modulates the associations between cigarette smoking, dietary antioxidants and breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2131–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margison GP, Heighway J, Pearson S, McGown G, Thorncroft MR, Watson AJ, et al. Quantitative trait locus analysis reveals two intragenic sites that influence O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1473–80. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiencke JK, Aldape K, McMillan A, Wiemels J, Moghadassi M, Miike R, et al. Molecular features of adult glioma associated with patient race/ethnicity, age, and a polymorphism in O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1774–83. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Liu J, Li A, Qian L, Wang X, Wei Q, et al. Exon 3 polymorphisms and haplotypes of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and risk of bladder cancer in southern China: a case-control analysis. Cancer Lett. 2005;227:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill CE, Wickliffe JK, Wolfe KJ, Kinslow CJ, Lopez MS, Abdel-Rahman SZ. The L84F and the I143V polymorphisms in the O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) gene increase human sensitivity to the genotoxic effects of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine carcinogen NNK. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:571–8. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000167332.38528.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chae MH, Jang JS, Kang HG, Park JH, Park JM, Lee WK, et al. O6-Alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase gene polymorphisms and the risk of primary lung cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:239–49. doi: 10.1002/mc.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur TB, Travaline JM, Gaughan JP, Richie JP, Stellman SD, Lazarus P. Role of polymorphisms in codons 143 and 160 of the O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase gene in lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers & Prevention. 2000;9:339–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boffetta P, Nyberg F, Mukeria A, Benhamou S, Constantinescu V, Batura-Gabryel H, et al. O6-Alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase activity in peripheral leukocytes, smoking and risk of lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;180:33–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M, Coles BF, Caporaso NE, Choi Y, Lang NP, Kadlubar FF. Lack of association between Caucasian lung cancer risk and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase-codon 178 genetic polymorphism. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imai Y, Oda H, Nakatsuru Y, Ishikawa T. A polymorphism at codon 160 of human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene in young patients with adult type cancers and functional assay. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2441–5. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.10.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu-Welliver M, Leitao J, Kanugula S, Meehan WJ, Pegg AE. The role of codon 160 in sensitivity of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase to O6-benzylguanine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1279–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerson SL, Schupp J, Liu L, Pegg AE, Srinivasan S. Leukocyte O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase from human donors is uniformly sensitive to O6-benzylguanine. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:521–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu MH, Lohrbach KE, Olopade OI, Kokkinakis DM, Friedman HS, Dolan ME. Lack of evidence for a polymorphism at codon 160 of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase gene in normal tissue and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;55:209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolan ME, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. Depletion of mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity by O6-benzylguanine provides a means to evaluate the role of this protein in protection against carcinogenic and therapeutic alkylating agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5368–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Xu-Welliver M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Inactivation and degradation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase after reaction with nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3037–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edara S, Kanugula S, Goodtzova K, Pegg AE. Resistance of the human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase containing arginine at codon 160 to inactivation by O6-benzylguanine. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5571–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mijal RS, Thomson NM, Moschel RC, Kanugula S, Fang Q, Pegg AE, et al. The repair of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine derived adduct, O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase variants. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:424–34. doi: 10.1021/tx0342417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mijal RS, Kanugula S, Vu CC, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. DNA sequence context affects repair of the tobacco-specific adduct O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4968–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nallamsetty S, Kapust RB, Tozser J, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Copeland TD, et al. Efficient site-specific processing of fusion proteins by tobacco vein mottling virus protease in vivo and in vitro. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;38:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang Q, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Function of domains of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15396–405. doi: 10.1021/bi051460d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue R, Abe M, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Mori T, Suzuki T. Characterization of human polymorphic DNA repair methyltransferases. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pegg AE, Chung L, Moschel RC. Effect of DNA on the inactivation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase by 9-substituted O6-benzylguanine derivatives. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:1559–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoue R, Isono M, Abe M, Abe T, Kobayashi H. A genotype of the polymorphic DNA repair gene MGMT is associated with de novo glioblastoma. Neurol Res. 2003;25:875–9. doi: 10.1179/016164103771954005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang WY, Chow WH, Rothman N, Lissowska J, Llaca V, Yeager M, et al. Selected DNA repair polymorphisms and gastric cancer in Poland. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1354–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohet C, Borel S, Nyberg F, Mukeria A, Bruske-Hohlfeld I, Constantinescu V, et al. Exon 5 polymorphisms in the O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase gene and lung cancer risk in non-smokers exposed to second-hand smoke. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:320–3. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pegg AE, Fang Q, Loktionova NA. Human variants of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. DNA Repair. 2007;6:1071–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodtzova K, Kanugula S, Edara S, Pauly GT, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. Repair of O6-benzylguanine by the Escherichia coli Ada and Ogt and the human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8332–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanugula S, Pauly GT, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. A bifunctional DNA repair protein from Ferroplasma acidarmanus exhibits O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and endonuclease V activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci US,A. 2005;102:3617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniels DS, Mol CD, Arvai AS, Kanugula S, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. Active and alkylated human AGT structures: a novel zinc site, inhibitor and extrahelical binding. DNA damage reversal revealed by mutants and structures of active and alkylated human AGT. EMBO J. 2000;19:1719–30. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daniels DS, Woo TT, Luu KX, Noll DM, Clarke ND, Pegg AE, et al. Novel modes of DNA binding and nucleotide flipping by the human DNA repair protein AGT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:714–20. doi: 10.1038/nsmb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hazra TK, Roy R, Biswas T, Grabowski DT, Pegg AE, Mitra S. Specific recognition of O6-methylguanine in DNA by active site mutants of human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5769–76. doi: 10.1021/bi963085i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loktionova NA, Xu-Welliver M, Crone T, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Mutant forms of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase protect CHO cells from killing by BCNU plus O6-benzylguanine or O6-8-oxo-benzylguanine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]