Abstract

The lens and cornea are transparent and usually avascular. Controlling nutrient supply while maintaining transparency is a physiological challenge for both tissues. During sleep and with contact lens wear the endothelial layer of the cornea may become hypoxic, compromising its ability to maintain corneal transparency. The mechanism responsible for establishing the avascular nature of the corneal stroma is unknown. In several pathological conditions, the stroma can be invaded by abnormal, leaky vessels, leading to opacification. Several molecules that are likely to help maintain the avascular nature of the corneal stroma have been identified, although their relative contributions remain to be demonstrated. The mammalian lens is surrounded by capillaries early in life. After the fetal vasculature regresses, the lens resides in a hypoxic environment. Hypoxia is likely to be required to maintain lens transparency. The vitreous body may help to maintain the low oxygen level around the lens. The hypothesis is presented that many aspects of the aging of the lens, including increased hardening, loss of accommodation (presbyopia), and opacification of the lens nucleus, are caused by exposure to oxygen. Testing this hypothesis may lead to prevention for nuclear cataract and insight into the mechanisms of lens aging. Although they are both transparent, corneal pathology is associated with an insufficient supply of oxygen, while lens pathology may involve excessive exposure to oxygen.

Keywords: hypoxia, neovascularization, cataract, avascular, oxygen

Developmental Physiology

The lens and cornea have physiological similarities and structural differences. In spite of their different anatomical features, for both tissues to maintain transparency, their cells must obtain needed metabolites and be protected from harmful influences from the environment. The manner in which the lens and cornea manage these physiological challenges and the impact of these solutions on their function and pathology are the topic of this review.

A dominant feature of the physiology of the lens and cornea of most mammals is their avascular nature in adult life. The cornea is avascular at all stages of its development. In mammals, the fetal lens is invested with a network of capillaries that regresses late in fetal or early postnatal life.

Maintaining the avascularity of the corneal stroma is an important aspect of corneal pathophysiology. Blood vessels are present in all mesenchymal or connective tissues, except for cartilage and the corneal stroma. The establishment and maintenance of an avascular stroma is an important aspect of corneal development and physiology. Neovascularization of the stroma may occur in response to several types of insults and is a significant cause of blindness or impaired vision [1].

In contrast, once the fetal vasculature around the lens has regressed, it is at minimal risk of neovascularization. However, exposure of the lens to excessive oxygen from the vascular system may underlie nuclear cataracts, the most common type of age-related cataracts. Therefore, maintaining an adequate nutrient supply without excess growth of blood vessels or exposure to oxygen is important for the proper function of both tissues. This review first considers the normal development of the cornea and lens, with emphasis on their developmental physiology, and then addresses the diseases that result from imbalances in the physiology of these tissues.

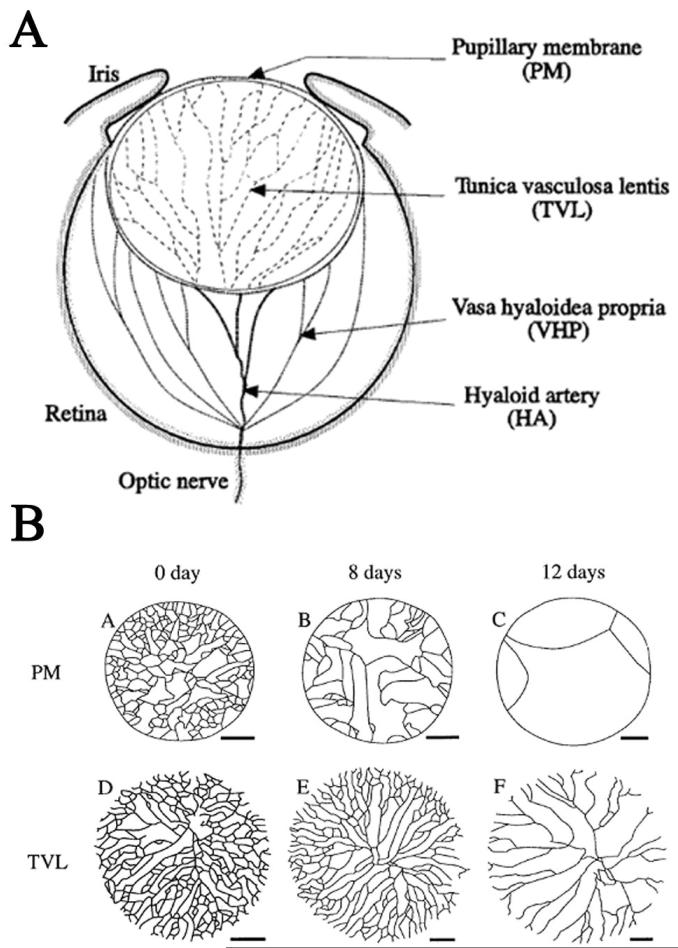

The formation and regression of the fetal vasculature around the lens

Soon after it forms, the mammalian lens becomes invested with a network of capillaries. In the posterior of the eye, the hyaloid artery, which enters at the future optic nerve head, gives rise to a network of hyaloid vessels within the developing vitreous body (Fig. 1A). These ramify near the inner surface of the retina and on the posterior surface of the lens. The capillary network on the posterior of the lens is the tunica vasculosa lentis (TVL). At the same time, another network of capillaries, the anterior pupillary membrane (APM), covers the anterior surface of the lens. The APM lies in the future anterior chamber, between the anterior lens capsule and the corneal endothelium. The capillaries of the APM branch from vessels in the anterior periocular mesenchyme. After the TVL and APM form, their capillaries join at the lens equator near the anterior margin of the optic cup [2].

Figure 1.

A. A diagram showing the hyaloid vasculature and the capillaries of the tunica vasculosa lentis and anterior pupillary membrane. B. Diagram showing the progressive loss of capillaries around the anterior (PM) and posterior (TVL) of the mouse lens in the first two weeks after birth. Figure modified from [2].

Early in its development, the lens expresses vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), a growth factor that is necessary for the formation of new blood vessels [3-5]. This observation led to the hypothesis that VEGF-A from the lens attracts the capillaries of the TVL. Over expression of VEGF-A or splice variants of VEGF-A caused increased formation of capillaries around the lens, indicating that a high level of this mitogen is capable of promoting the proliferation of the endothelial cells of the TVL and the growth of new vessels from the TVL [6-8]. Direct evidence that endogenous VEGF-A from the lens is responsible for the normal development of the TVL is provided by unpublished studies, in which Vegfa is removed from the lens by conditional deletion early in lens formation (Garcia, Kamath, Ferrara and Beebe, unpublished data). Deletion of Vegfa did not prevent early lens formation or the establishment of the hyaloid vasculature, but prevented the formation of the TVL. At birth, lenses lacking Vegfa and the TVL are slightly smaller than normal with a mild nuclear cataract that did not increase in severity during postnatal development. This suggests that the fetal vasculature plays only a minor role in lens development. This observation is consistent with the absence of capillaries around the lenses of most non-mammalian vertebrates. It also raises the question of why the fetal vasculature appeared in mammalian evolution.

The capillaries of the TVL and APM regress late in fetal development in humans and before eye opening in rodents (Fig. 1B). Previous investigators suggested that a decline in VEGF-A secretion from the lens might trigger capillary regression [3]. Instead of decreasing, VEGF-A levels increase during and after the regression of the TVL and APM [4]. VEGF-A mRNA levels in the lens epithelium also increased when the adult lens was made more hypoxic and decreased during ocular hyperoxia. This observation suggests that, as in many other tissues, VEGF-A expression in the lens is regulated by tissue oxygen levels [4]. Therefore, the regression of the fetal vasculature is not regulated by decreased VEGF-A from the lens. An alternative signal for the regression of the TVL and APM is a decrease in VEGF-A levels in the blood [9].

The capillaries of the TVL and APM regress by a process that involves the orderly constriction of their lumens and apopototic death of their endothelial cells [2, 10]. Like programmed vascular regression in many tissues, the dismantling of the fetal vasculature occurs without apparent leakage of lumenal contents or inflammation. Regression of the TVL requires the function of ARF, a protein encoded from an alternative reading frame of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Ink4a locus [11, 12] and the apoptosis-promoting protein, Bak and Bax [13]. ARF acts in a manner that is independent of its normal target, the tumor suppressor, p53 [12]. It is apparent that perivascular macrophages in the eye orchestrate vascular regression [14]. Intraocular macrophages secrete Wnt7b, a morphogen that triggers apoptosis in nearby hyaloid vascular endothelial cells [15]. In addition, signaling through the Wnt receptor, frizzled4 (Fz4) by Norrin, the secreted protein product of the Norrie Disease locus, is also required for the formation of normal retinal vasculature and regression of the TVL [16, 17]. Although intraocular macrophages are required for vascular regression, how the timing of regression is controlled remains uncertain. Bone marrow macrophages activated in vitro and injected on postnatal day 3 into a mouse eye that lacks macrophages mediates vascular regression on schedule [15]. This makes it unlikely that the intrinsic activities of macrophages are responsible for timing capillary regression. If decreasing levels of VEGF-A in the blood are responsible for regression, this might now be tested using one of several VEGF-A antagonists that are available.

Failure of the fetal vasculature to regress completely is a relatively common congenital abnormality of varying severity. Its clinical manifestations have been thoroughly reviewed [18] and will not be considered further.

Formation of the cornea and establishment of corneal avascularity; a role for the lens

The three layers of the cornea are derived from at least three different precursor cell populations in the mammalian embryo. The corneal epithelium forms from the head ectoderm, while the connective tissue stroma and endothelium are derived from a mixture of neural crest and mesodermal mesenchyme cells [19]. Remarkably, the source and nature of the signals that specify the ectoderm to become corneal epithelium, instead of skin, for example, are unknown. Proper differentiation of the stroma and endothelium depends on signals from the lens epithelium [20, 21], although the nature of the responsible molecule or molecules is not known.

At its lateral edges, the corneal stroma is continuous with the scleral connective tissue. Therefore, the cornea is surrounded by the blood vessels underlying the peripheral (limbal) corneal epithelium and the vasculature of the sclera during its development and throughout life. Under normal circumstances, these peripheral vessels do not grow into the corneal stroma. Because most embryonic mesenchyme is well vascularized, this suggests that, from its inception, factors are present in the stroma to prevent or discourage its invasion by blood vessels. As described below, several studies have examined the factors that maintain the avascularity of the adult cornea. It is not known whether these molecules or different anti-angiogenic factors prevent the vascularization of the corneal stroma during its formation.

Surgical or genetic interventions that disrupt normal lens differentiation are accompanied by defects in the differentiation of the corneal stroma [20, 22-24]. In several of these, the stroma becomes vascularized. Comparison of the population of molecules in the prospective stroma from these eyes with the molecules expressed in un-operated or genetically normal controls might identify the molecules responsible for the establishment of corneal avascularity.

Nutrient and oxygen supply to the cornea and lens

Because they are avascular, the lens and cornea obtain most nutrients by diffusion from surrounding fluids; the aqueous humor, the interstitial fluid supplied by the peri-corneal vasculature, or the tear film. Because metabolites must often diffuse over long distances to reach the cells of the lens or cornea, significant limits are placed on their metabolism. This requirement also assures that the environment around lens or corneal cells is different from most other tissues. In some cases, this may protect these tissues from stresses. In other cases, it places them at increased risk.

Oxygen presents a special problem, because it has low solubility in aqueous media. Most of the oxygen that reaches the corneal endothelium diffuses from the air through the epithelium and stroma. The aqueous humor is a poor source of oxygen, because little oxygen is present in freshly-secreted aqueous humor [25]. A small amount of oxygen is derived from the iris vasculature, but much of this is consumed by the lens [25, 26]. This produces a steep oxygen concentration gradient in the anterior chamber, with its highest point at the inner surface of the cornea and lowest near the surface of the lens [25, 27, 28]. For this reason, no amount of stirring of the aqueous humor can increase the oxygen supply to the endothelium.

The cornea is prevented from swelling by the continuous transport activity of the endothelial layer. Sodium and bicarbonate ions accumulate on the aqueous side of the endothelial layer and water follows, moving out of the stroma down its concentration gradient [29]. The endothelial layer also allows aqueous to ‘leak’ into the stroma, delivering metabolites to the stromal cells and increasing the need for endothelial pump activity. Damage to the transport capability of the endothelium, usually caused by loss of endothelial cells from damage [30], hereditary disease [31, 32], or aging [33], leads to swelling of the stroma and loss of transparency.

The cornea swells at night, in part because oxygen from the air is restricted from reaching the endothelium by the closed eyelids, thereby limiting oxidative metabolism [34]. The delivery of nutrients to the corneal endothelium is sufficiently precarious that David Maurice suggested that the function of Rapid Eye Movement sleep may by to stir the aqueous humor, thereby maintaining a sufficient supply of glucose to the corneal endothelium. This would permit glycolytic metabolism and maintain pump function in the absence of adequate oxidative metabolism [34]. Contact lens wear presents a similar problem, reducing the access of oxygen to the inner layers of the cornea. This is partially ameliorated by the use of more oxygen-permeable lenses, but these must, to some degree, reduce the oxygen supply to the endothelium [35, 36].

Low oxygen levels are normally present in the aqueous and vitreous humors around the lens [25-28, 37-39]. In most tissues, oxygen partial pressures below 5% (∼38 mmHg) are considered hypoxic. The oxygen level near the anterior lens epithelium in humans is approximately 2% (∼14 mmHg) [27], while at the posterior of the lens oxygen levels are below 1.5% (8-10 mmHg) [39] In contrast to the need to supply adequate oxygen to the cornea, maintaining low levels of oxygen around the lens appears to be important to preserve its transparency and to regulate its growth. The potential role of oxygen in the formation of nuclear cataracts is described in the section on pathophysiology. The following section summarizes unpublished evidence that that low intraocular oxygen regulates lens growth.

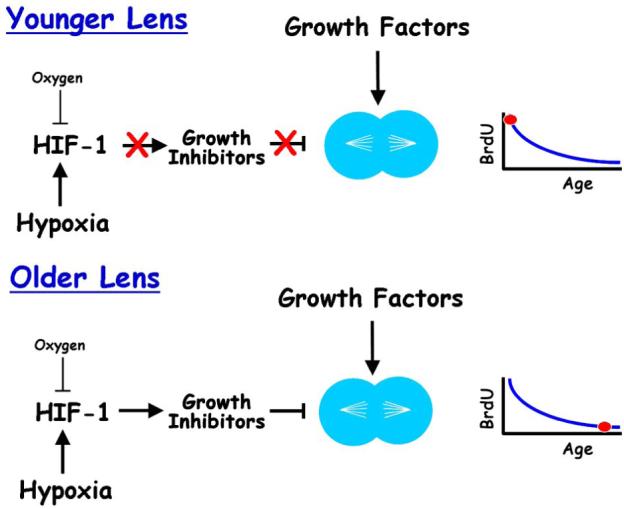

In rodents, the rate of lens growth decreases steadily after one-month of age. Experiments conducted by Dr. Ying-Bo Shui showed that breathing 60% oxygen raised intraocular oxygen levels and increased the BrdU labeling index in older mice and rats, but not in one-month-old animals (Shui, Arbeit, Johnson and Beebe, submitted). At all ages older than one month, increasing intraocular oxygen increased the BrdU labeling index to the level seen at one month. Increased lens epithelial cell proliferation was accompanied by the formation of additional lens fiber cells and an increase in lens wet weight. The normal hypoxic environment within the eye maintained relatively high levels of the hypoxia-regulated transcription factor, HIF-1α in lens epithelial cells. These levels decreased when oxygen levels were increased. Exposure of young or older lenses to increased oxygen decreased the expression of genes, like Vegfa and Car9, which are HIF-1 target genes (Shui, et al., submitted)[4]. The expression in lens epithelial cells of oxygen-insensitive forms of HIF-1α or the pharmacological inhibition of HIF-1α degradation suppressed the ability of oxygen to increase lens cell proliferation in older animals (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the normal, low level of oxygen in the eye maintains high HIF-1 activity and that HIF-1 suppresses lens cell proliferation with increasing effectiveness as the lens ages (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed effects of oxygen on HIF-1 levels and function in young or old mice. In young or older animals, HIF-1 levels and activity are high, due to the hypoxic environment in the eye. Increasing oxygen exposure decreases HIF-1 levels in the lens. However, in young lenses, HIF-1 is not suppressing lens growth. Therefore, decreasing HIF-1 level and activity has no effect on BrdU incorporation, as shown in the graph to the right. In older animals, high HIF-1 levels suppress lens epithelial cell proliferation, as shown by low BrdU incorporation in the graph to the right. Raising intraocular oxygen decreases HIF-1 levels and HIF-1 transcriptional activity. This releases the inhibition of cell proliferation, permitting the growth factors that are normally present in the eye to stimulate lens epithelial cell proliferation, resulting in faster lens growth.

Pathophysiology

Corneal neovascularization - ‘angiogenic privilege’

Maintenance of the avascular state of the cornea has been termed ‘angiogenic privilege’ [1, 40]. This terminology parallels the special protection that the cornea enjoys against the immune rejection of grafted tissues, its ‘immune privilege.’ This designation implies that the absence of blood vessels in the corneal stroma is atypical, just as most parts of the body do not have special protection against immune rejection of foreign antigens. The causes of corneal neovascularization, including persistent hypoxia, chronic inflammation, injury and hereditary stem cell deficiency, have been thoroughly reviewed recently and are not discussed further [1]. The molecules responsible for creating and maintaining ‘angiogenic privilege’ and the pathological consequences of loss of this protection are active topics of research.

Several molecules have been shown to contribute to corneal avascularity. These may work together, each helping to suppress neovascularization. Alternatively, it has been stated that individual molecules are sufficient to prevent corneal vascularization. It seems unlikely, on evolutionary grounds, that a single mechanism or molecule would be sufficient to preserve functional vision. Therefore, the relative importance of each candidate molecule in maintaining corneal avascularity deserves to be carefully evaluated.

One of the first molecules thought to be sufficient to preserve corneal avascularity is pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) [41]. PEDF is abundant in avascular cartilage and higher levels of PEDF have been correlated with inhibition of retinal neovascularization. PEDF is present in the corneal stroma and inhibition of PEDF activity in the cornea by delivery of a function-blocking antibody led to blood vessel invasion. Delivery of excess PEDF to the corneal stroma reduced neovascularization induced by pro-angiogenic factor, fibroblast growth factor [42]. A mouse knockout of PEDF was made several years ago, but no mention was made about whether its cornea was avascular or whether it was susceptible to corneal neovascularization [43]. Meeting reports, not yet published, have questioned the importance of PEDF in creating or maintaining corneal avascularity. The relative importance of PEDF in these processes remains to be evaluated.

A recent study implicated an alternatively spliced version of VEGF receptor-1, sFlt1, as a molecule that is sufficient to maintain corneal avascularity [44]. This is a rational proposal, as sFlt1 is the secreted extracellular domain of the receptor, which binds and sequesters VEGF-A. Reduction of corneal sFlt1 mRNA levels by RNA interference or deletion of the sFlt gene by adenovirus-mediated delivery of Cre-recombinase to genetically susceptible mice caused corneal neovascularization. Restoration of sFlt1 levels in mice that are genetically prone to neovascularization prevented blood vessel growth. Decreased sFlt1 expression in the vascularized corneas of the Florida manatee provided a compelling example from nature in support of this function.

However, questions remain about the sufficiency of sFlt1 for maintaining an avascular cornea. Deletion or knockdown of sFlt1 was accomplished using an adenoviral vector. It remains to be seen to what degree the vessels in the mouse cornea were due to absence of sFlt1 or whether the treatments needed to remove sFlt1, in combination with lower sFlt1 levels, permitted the growth of new vessels. More convincing evidence of the sufficiency of sFlt1 for maintaining avascularity would be provided by corneas lacking sFlt1 from early in development. While manatees have vascularized corneas, these corneas appear to remain transparent [45]. It is not clear whether knockdown or ablation of sFlt1 was accompanied by the invasion of the mouse cornea with pathologic, leaky vessels, which would render the tissue opaque, or by more normal vessels, as in the manatee. If vessels are present in the sFlt-null cornea from birth, it will be important to know whether these vessels are normal or pathologic. Whether or not sFlt1 is sufficient for the establishment and maintenance of corneal avascularity, it is a strong candidate as one of the molecules that preserves the avascular nature of the cornea.

Thrombospondins (TSPs) 1-4 comprise a family of secreted molecules that have been implicated in the suppression of vascularization. One early clue about their possible function was the localization of TSP-1 and TSP-3 in avascular cartilage, but not in hypertrophic cartilage, which becomes vascularized [46]. TSP-1 and -2 are normally present in the cornea and iris [47]. Examination of mice lacking TSP-1 and/or TSP-2 showed that TSP-1 was most effective at reducing inflammation-induced corneal neovascularization, while lack of TSP-2 increased the vascularization of the iris during development [47]. However, these genes were not sufficient to account for corneal avascularity, since mice lacking both TSP isofoms had clear, avascular corneas.

The corneal epithelium is an important source of molecules that mediate ‘angiogenic privilege’ [44, 48]. Inflammation-induced angiogenesis in the cornea is associated with increased expression of VEGF receptor-3 (VEGFR-3) a receptor for the ligands VEGF-C and VEGF-D. Treatment of corneas at risk for inflammation-induced angiogenesis with the ligand-binding domain of VEGFR-3 significantly suppressed angiogenesis, while treatment with an antibody that blocks the activity of VEGFR-3 increased neovascularization. These studies support a role for VEGFR-3 in opposing corneal neovascularization in this setting.

Several other molecules have been suggested as candidates that may help to establish corneal avascularity or prevent pathologic neovascularization. These include the angiopoietin-like molecule, cornea-derived transcript -6 (CDT6, also called AngX) [49] and the inhibitory PAS-domain transcription factor, IPAS, which has been reported to prevent the hypoxic induction of VEGF-A [50].

The relative contributions to corneal avascularity of these and other molecules remain to be tested. No matter what their role in the establishment of corneal avascularity or the maintenance of ‘angiogenic privilege,’ some of these molecules may prove useful for the suppression of pathologic angiogenesis in the clinic.

Oxygen toxicity and the formation of nuclear cataracts

Age-related cataracts are the most common cause of blindness worldwide. As a result of increasing lifespan, surgical removal of cataracts is a major and growing expense to society. Therefore, delaying or preventing the formation of cataracts remains an important goal.

Although epidemiologic studies identified risk factors for age-related cataract, most of these, like sex, heredity or iris color, cannot be modified [51-55]. Of the established risks that are amenable to modification, reducing smoking has been difficult, even when known to be life-threatening, and sunlight exposure appears to contribute only minimally to the overall risk of age-related cataract [56]. Genetic factors are major contributors to age-related cataract, but the genes involved have not been identified [57-60]. Identification of these genes could point to the metabolic alterations that increase or decrease the risk of cataracts. These considerations highlight the importance of understanding the physiologic factors that protect the lens from cataract and the changes that occur with age that make the lens more susceptible to cataract formation.

Increased exposure to oxygen has been identified as a risk factor for nuclear cataract, the most common type of age-related cataract. As mentioned above, the fluids around the lens have very low oxygen partial pressure, as little as 1% to a maximum of 3% oxygen (7 to 25 mmHg) [25-27]. Oxygen levels within the lens are even lower [26, 38]. Chronic exposure of patients to hyperbaric oxygen, as part of a therapeutic regimen, caused increased opacification of the lens nucleus or frank nuclear cataracts in a group of older individuals [61]. Thus, the lens is normally in a hypoxic environment and excess oxygen promotes nuclear cataract formation in a susceptible population.

Recent observations led to the suggestion that the vitreous body, the gelatinous extracellular matrix between the lens and the retina, may protect the lens from exposure to excess oxygen. It is well known that more than 60% of patients in whom the vitreous body is removed during retinal surgery develop nuclear cataracts within two years [62-65]. If retinal surgery can be performed without vitrectomy, cataract formation is prevented [66, 67]. The vitreous body gradually liquefies with age [68, 69], although the extent of liquefaction varies greatly among individuals of similar age [69]. In donor eyes, increased liquefaction of the vitreous body is associated with increased opacification of the lens nucleus, but not with opacification of other parts of the lens, as occurs in cortical or posterior subcapsular cataracts [70]. Oxygen levels near the lens increase acutely during vitrectomy surgery and are chronically elevated in patients who have undergone previous vitrectomy surgery [39]. Oxygen levels are lower in the vitreous body of diabetic patients and diabetics appear to be relatively protected against nuclear cataract formation [71].

These results suggest a model to explain how the vitreous body may protect the lens from oxygen [70]. In the vitreous gel close to the retinal surface, oxygen levels are normally high, especially near the retinal vessels [72]. Oxygen diffusing into the vitreous body from the retinal vessels is used by nearby retinal cells for oxidative metabolism [72]. As long as the gel vitreous is present, this creates a standing oxygen gradient at the surface of the retina. Removal of the vitreous gel, either by vitrectomy or age-related degeneration of the vitreous body, allows fluid to circulate in the vitreous chamber. The flow of liquid vitreous destroys the oxygen gradient near the retina and circulates oxygen throughout the posterior of the eye. The vitreous circulation permits more oxygen to reach the lens, leading to nuclear cataract formation.

Age-related changes in the lens are likely to make it more susceptible to oxygen-induced nuclear cataracts. Nuclear cataracts are caused by excessive oxidation of proteins in the center of the lens, the lens nucleus [73-77]. The cells of the lens nucleus have minimal metabolic capabilities. For their protection from oxidative damage, the proteins in these cells depend on antioxidant compounds that are produced in metabolically active cells near the surface of the lens. These molecules, especially glutathione, diffuse through gap junctions that connect cells on the surface of the lens to the cells of the lens nucleus [78]. If antioxidant compounds in the nucleus become oxidized, they must diffuse to back to the metabolically active cells at the lens surface to be reduced or re-synthesized. With increasing age, the rate of diffusion in the lens cytoplasm is significantly reduced [75, 78-80] and oxidized glutathione levels in the lens nucleus increase [75, 81, 82]. Small increases in oxygen exposure, which might be tolerated by a younger lens, may lead to protein oxidation and nuclear cataract in older individuals.

This view of nuclear cataract formation suggests interventions that could be successful in preventing or delaying this disease. Replacing a gel in the vitreous chamber after vitrectomy should restore the normal distribution of oxygen within the eye, lowering oxygen near the lens. Barriers that protect the lens from exposure to excess oxygen could also protect the lens from oxidative damage. At least 35% of nuclear cataracts can be accounted for by inherited predisposition [58, 83]. Since degeneration of the vitreous body is a risk factor for nuclear cataracts, genetic variants that lead to early vitreous liquefaction could account for some or all of this risk. Understanding and preventing vitreous degeneration could protect the lens from the increase exposure to oxygen that accompanies vitreous liquefaction. Since no other species is known to develop cataracts after vitrectomy or vitreous degeneration, protecting the human lens from exposure to excess oxygen is the only means to definitively test the importance of oxygen in nuclear cataract formation.

Oxygen, lens growth and cataracts

Increasing oxygen levels around the lens increases the rate of lens growth (Shui, Arbeit, Johnson and Beebe, submitted). This raises the possibility that exposure of the lens to increased oxygen following vitrectomy surgery or after degeneration of the vitreous body could result in larger lenses. Therefore, it is worth considering whether differences in lens size might influence the risk of cataract formation.

Epidemiologic evidence and theoretical considerations suggest that increasing lens size increases the risk of nuclear cataract. In a cross sectional study, individuals with larger lenses were significantly more likely to have nuclear cataracts [84]. Longitudinal study of this population showed that those who began the follow up period with larger lenses were more likely to develop nuclear cataracts over five years [85]. Epidemiologic studies in Japan and Singapore showed a similar tendency, with lens thickness positively associated with nuclear cataract in cross sectional and prospective studies (K. Nagai, K. Sasaki and H. Sasaki, Kanazawa Medical University, personal communication). As discussed above, antioxidants must diffuse from cells near the lens surface to protect the lens nucleus from oxidative damage [78]. If the lens is larger, diffusion will be less efficient, perhaps increasing the risk of oxidative damage and nuclear cataract formation. Therefore, increased exposure to oxygen could put the lens at risk of nuclear cataracts in two ways: by directly increasing oxidative damage and by increasing the rate of lens growth, which may indirectly make the lens more susceptible to oxidative damage.

Oxygen and lens aging: a ‘Theory of Everything’

During the human lifetime, the hardness or stiffness of the lens nucleus increases by a factor of 103 to 104 [86, 87]. The increasing stiffness of the lens is thought to account for presbyopia, the loss of accommodative amplitude and the resulting loss of near vision that invariably becomes evident in the fifth decade of life [80, 86]. Many age-related changes in lens biochemistry have been described that may contribute to lens hardening. These include reduction in protein-bound water in the nucleus (syneresis) [88], the progressive insolubilization of α-crystallin [89], protein modification (including oxidative modification) [90], proteolysis of crystallins [91], amino acid racemization [92], and others. However, the effect on hardening of any of these changes has not been evaluated. Therefore, the mechanism(s) responsible for this remarkable physical change remains unclear.

The formation of a nuclear cataract is associated with an even greater increase in lens hardness. For this reason, cataract surgeons refer to nuclear opacities as ‘nuclear sclerotic cataracts.’ The rapidly-progressing nuclear cataracts that occur within one or two years after vitrectomy are also sclerotic. In contrast, the nuclear region of a cortical or posterior subcapsular cataract is typically no harder than would be expected for the age of the lens.

The studies described above suggest that post-vitrectomy nuclear cataracts and, perhaps, age-related nuclear cataracts are caused by excessive exposure of the lens to oxygen. If this view is correct, it is worth asking whether oxygen exposure or oxidative modification accounts for the hardening of the lens that accompanies ‘normal’ aging. The human lens is exposed to a well-controlled, low dose of oxygen throughout most of life. I propose that even this low level of oxygen contributes to, or accounts for, the progressive increase in lens hardness that occurs with age in all individuals.

Nuclear cataract formation: accelerated aging?

Nuclear cataract formation involves an increase in yellowing and light scattering in the lens nucleus. As the lens ages and hardens, the lens nucleus also becomes increasingly yellow and scatters more light. Therefore, the nuclear ‘opacity score,’ a measure of the degree of nuclear cataract, tends to increase steadily in all individuals as they age. One widely-used cataract grading system is the Lens Opacity Classification System III (LOCS III) [93]. The LOCS III scoring system ranks nuclear opacities from 0.1 to 6.9. There are few 50 year olds with a LOCS III nuclear opacity score as low as 1.0 and most are closer to 2.0 [70]. The average LOCS III nuclear opacity score increases steadily in all individuals after age 50. Epidemiologic studies sometimes consider nuclear cataracts to be present in those with a LOCS III score of 2.5 to 3.0 or more [94, 95]. As a result, after age 85 or 90 it becomes difficult to distinguish between ‘normal’ aging and nuclear cataract formation.

No similar gradual increase is seen in a person’s opacity scores for cortical or posterior subcapsular cataracts. The score for these opacities in older individuals is either zero (no cataract) or some positive value (some degree of cataract). While the number of individuals with cortical or posterior subcapsular cataract tends to increase, many individuals, even those much older than 50, will have LOCS III scores of 0.0 [70]. Therefore, the fundamental difference between nuclear opacification and opacification associated with the other types of age-related cataracts is that all older individuals have some degree of nuclear opacity, while most will have no trace of cortical or posterior subcapsular opacity.

The difference between those older individuals who develop nuclear cataracts and individuals of similar age who do not could be the state of the vitreous body. If the vitreous body degenerates or is removed during surgery, the resulting increase in oxygen exposure could cause more rapid hardening of the cytoplasm of the lens nucleus, increased light scattering, increased yellowing and, therefore, opacification. If the vitreous body remains intact, as it does in a substantial number of older individuals [70], the lens continues its slow, steady increase in nuclear color and opacity, only reaching a level that significantly degrades visual function in the ninth or tenth decade of life.

If increased exposure to oxygen accounts for the rapid increase after vitrectomy in the color, opacity and hardness of the lens nucleus, there is reason to suspect that exposure to a lower level of oxygen throughout life could be responsible for the slower progression of these same changes during normal aging. This hypothesis, that oxygen exposure is responsible for the gradual hardening, increasing color and light scattering of the lens that occurs with age, has not been evaluated. However, it is testable. All that is needed is to lower the level of oxygen around the lens. My colleagues and I are developing methods to reduce the exposure of the lens to oxygen after vitrectomy. If the hypothesis presented above is correct, application of these treatments to individuals with early vitreous degeneration or vitrectomy should reduce the rate of increase of lens hardness, nuclear color and light scattering, along with decreasing the risk of developing frank nuclear cataracts.

Summary

Because they must remain transparent, access of the lens and cornea to the vascular supply is limited. The cornea manages adequate metabolic activity as long as it has access to oxygen across the tear film and glucose from the aqueous humor. Due to its anatomical proximity to the sclera, the corneal stroma is continually at risk of vascularization. Several factors have been suggested to preserve the ‘angiogenic privilege’ of the stroma, although the relative importance of each remains to be demonstrated. The lens is surrounded by capillaries early in life. Once these regress, it is isolated from direct contact with the blood supply. The hypoxic environment around the lens appears to regulate the rate of lens growth and may be important to protect it against nuclear cataracts. The possibility that oxygen contributes to age-related changes in the lens may be tested in humans in studies aimed at reducing the risk of post-vitrectomy cataracts.

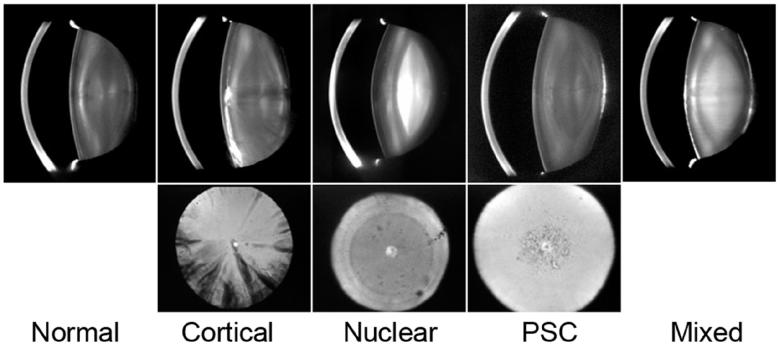

Figure 3.

Examples of the common types of age related cataracts. The upper row of images shows Scheimpflug camera views of the normal lens and four types of age-related cataracts. The lower row of pictures are retroillumination images of the three common types of age-related cataracts (Photos courtesy of Dr. Ying-Bo Shui).

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to his colleagues, Drs. Claudia Garcia, Ying-Bo Shui and Nancy Holekamp for their many productive discussions and for reference to their unpublished studies. Support for the author’s research was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness, the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Core Grant P30 EY 02687 and NIH grants R01 EY04853 and EY015863.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Azar DT. Corneal angiogenic privilege: angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in corneal avascularity, vasculogenesis, and wound healing (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:264–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito M, Yoshioka M. Regression of the hyaloid vessels and pupillary membrane of the mouse. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;200(4):403–11. doi: 10.1007/s004290050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell CA, Risau W, Drexler HC. Regression of vessels in the tunica vasculosa lentis is initiated by coordinated endothelial apoptosis: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor as a survival factor for endothelium. Dev Dyn. 1998;213(3):322–33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199811)213:3<322::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shui Y-B, et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and Signaling in the Lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(9):3911–3919. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber HP, et al. VEGF is required for growth and survival in neonatal mice. Development. 1999;126(6):1149–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ash JD, Overbeek PA. Lens-Specific VEGF-A Expression Induces Angioblast Migration and Proliferation and Stimulates Angiogenic Remodeling. Dev Biol. 2000;223(2):383–398. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutland CS, et al. Microphthalmia, persistent hyperplastic hyaloid vasculature and lens anomalies following overexpression of VEGF-A188 from the alphaA-crystallin promoter. Mol Vis. 2007;13:47–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell CA, et al. Unique vascular phenotypes following over-expression of individual VEGFA isoforms from the developing lens. Angiogenesis. 2006;9(4):209–24. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeson AP, et al. VEGF deprivation-induced apoptosis is a component of programmed capillary regression. Development. 1999;126(7):1407–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latker CH, Kuwabara T. Regression of the tunica vasculosa lentis in the postnatal rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;21(5):689–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin AC, et al. Pathogenesis of Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous in Mice Lacking the Arf Tumor Suppressor Gene. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(10):3387–3396. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKeller RN, et al. The Arf tumor suppressor gene promotes hyaloid vascular regression during mouse eye development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(6):3848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052484199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn P, et al. Persistent Fetal Ocular Vasculature in Mice Deficient in Bax and Bak. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(6):797–802. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang R, et al. Apoptosis during macrophage-dependent ocular tissue remodelling. Development. 1994;120(12):3395–403. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobov IB, et al. WNT7b mediates macrophage-induced programmed cell death in patterning of the vasculature. 2005;437(7057):417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature03928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Q, et al. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear; control by norrin and frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell. 2004;116(6):883–95. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohlmann AV, et al. Norrie Gene Product Is Necessary for Regression of Hyaloid Vessels. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(7):2384–2390. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg MF. Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV): an integrated interpretation of signs and symptoms associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV). LIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(5):587–626. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gage PJ, et al. Fate Maps of Neural Crest and Mesoderm in the Mammalian Eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46(11):4200–4208. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beebe DC, Coats JM. The Lens Organizes the Anterior Segment: Specification of Neural Crest Cell Differentiation in the Avian Eye. Dev Biol. 2000;220(2):424–431. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thut CJ, et al. A large-scale in situ screen provides molecular evidence for the induction of eye anterior segment structures by the developing lens. Dev Biol. 2001;231(1):63–76. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia CM, et al. Signaling through FGF receptor-2 is required for lens cell survival and for withdrawal from the cell cycle during lens fiber cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2005;233(2):516–27. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breitman M, et al. Genetic ablation: targeted expression of a toxin gene causes microphthalmia in transgenic mice. Science. 1987;238(4833):1563–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3685993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Key B, et al. Lens structures exist transiently in development of transgenic mice carrying an alpha-crystallin-diphtheria toxin hybrid gene. Exp Eye Res. 1992;55(2):357–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90200-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shui Y-B, et al. Oxygen Distribution in the Rabbit Eye and Oxygen Consumption by the Lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47(4):1571–1580. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbazetto IA, et al. Oxygen tension in the rabbit lens and vitreous before and after vitrectomy. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78(5):917–24. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helbig H, et al. Oxygen in the anterior chamber of the human eye. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1993;2(3):161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitch CL, Swedberg SH, Livesey JC. Measurement and manipulation of the partial pressure of oxygen in the rat anterior chamber. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20(2):121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonanno JA. Identity and regulation of ion transport mechanisms in the corneal endothelium. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2003;22(1):69–94. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffy RE, et al. An Epidemic of Corneal Destruction Caused by Plasma Gas Sterilization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1167–1176. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.9.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundin OH, et al. Linkage of Late-Onset Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy to a Novel Locus at 13pTel-13q12.13. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47(1):140–145. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biswas S, et al. Missense mutations in COL8A2, the gene encoding the {alpha}2 chain of type VIII collagen, cause two forms of corneal endothelial dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10(21):2415–2423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joyce NC. Cell cycle status in human corneal endothelium. Experimental Eye Research. 2005;81(6):629–638. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurice DM. The Von Sallmann Lecture 1996: an ophthalmological explanation of REM sleep. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66(2):139–45. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMahon TT, Zadnik K. Twenty-five years of contact lenses: the impact on the cornea and ophthalmic practice. Cornea. 2000;19(5):730–40. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200009000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holden BA, Williams L, Zantos SG. The etiology of transient endothelial changes in the human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(10):1354–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaren JW, et al. Measuring oxygen tension in the anterior chamber of rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(10):1899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNulty R, et al. Regulation of tissue oxygen levels in the mammalian lens. J Physiol (Lond) 2004;559(3):883–898. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holekamp NM, Shui YB, Beebe DC. Vitrectomy surgery increases oxygen exposure to the lens: a possible mechanism for nuclear cataract formation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(2):302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang JH, et al. Corneal neovascularization. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12(4):242–9. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tombran-Tink J, Chader G, Johnson L. PEDF: A pigment epithelium-derived factor with potent neuronal differentiative activity. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53(3):411–414. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90248-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dawson DW, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science. 1999;285(5425):245–8. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grayhack JT, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor, a human testis epididymis secretory product, promotes human prostate stromal cell growth in culture. J Urol. 2004;171(1):434–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000088774.80045.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ambati BK, et al. Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1. Nature. 2006;443(7114):993–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harper JY, Samuelson DA, Reep RL. Corneal vascularization in the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and three-dimensional reconstruction of vessels. Vet Ophthalmol. 2005;8(2):89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tucker RP, et al. In situ localization of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-3 transcripts in the avian embryo. Dev Dyn. 1997;208(3):326–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<326::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cursiefen C, et al. Roles of Thrombospondin-1 and -2 in Regulating Corneal and Iris Angiogenesis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(4):1117–1124. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cursiefen C, et al. Nonvascular VEGF receptor 3 expression by corneal epithelium maintains avascularity and vision. PNAS. 2006;103(30):11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peek R, et al. Molecular cloning of a new angiopoietinlike factor from the human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(10):1782–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makino Y, et al. Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature. 2001;414(6863):550–554. doi: 10.1038/35107085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Age-Related Eye Diseases Study Group The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): design implications, AREDS report no. 1. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20(6):573–600. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delcourt C, et al. Risk factors for cortical, nuclear, and posterior subcapsular cataracts: the POLA study. Pathologies Oculaires Liees a l′Age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(5):497–504. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West SK, Valmadrid CT. Epidemiology of risk factors for age-related cataract. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(4):323–34. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Risk factors associated with age-related nuclear and cortical cataract: a case-control study in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, AREDS Report No. 5. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(8):1400–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00626-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group Causes and Prevalence of Visual Impairment Among Adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West SK, et al. Sunlight exposure and risk of lens opacities in a population-based study: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation project. Jama. 1998;280(8):714–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammond CJ, et al. The Heritability of Age-Related Cortical Cataract: The Twin Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(3):601–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hammond CJ, et al. Genetic and environmental factors in age-related nuclear cataracts in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1786–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iyengar SK, et al. Identification of a major locus for age-related cortical cataract on chromosome 6p12-q12 in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. PNAS. 2004;101(40):14485–14490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400778101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klein AP, et al. Polygenic Effects and Cigarette Smoking Account for a Portion of the Familial Aggregation of Nuclear Sclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005;161(8):707–713. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palmquist BM, Philipson B, Barr PO. Nuclear cataract and myopia during hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(2):113–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melberg NS, Thomas MA. Nuclear sclerotic cataract after vitrectomy in patients younger than 50 years of age. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(10):1466–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30844-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cherfan GM, et al. Nuclear sclerotic cataract after vitrectomy for idiopathic epiretinal membranes causing macular pucker. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111(4):434–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson JT, et al. Progression of nuclear sclerosis and long-term visual results of vitrectomy with transforming growth factor beta-2 for macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Effenterre G, et al. Is vitrectomy cataractogenic? Study of changes of the crystalline lens after surgery of retinal detachment. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1992;15(89):449–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawa M, et al. Assessment of nuclear sclerosis after nonvitrectomizing vitreous surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(3):356–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sawa M, et al. Nonvitrectomizing Vitreous Surgery for Epiretinal Membrane: Long-term Follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(8):1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sebag J. Age-related changes in human vitreous structure. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225(2):89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02160337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Malley P. The pattern of vitreous syneresis. A study of 800 autopsy eyes. In: Irvine AR, O’Malley C, editors. Advances in vitreous surgery. Ill. Thomas; Springfield: 1976. pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harocopos GJ, et al. Importance of Vitreous Liquefaction in Age-Related Cataract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(1):77–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holekamp NM, Shui Y-B, Beebe D. Lower Intraocular Oxygen Tension in Diabetic Patients: Possible Contribution to Decreased Incidence of Nuclear Sclerotic Cataract. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;141(6):1027–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alder VA, et al. Vitreal oxygen tension gradients in the isolated perfused cat eye. Curr Eye Res. 1986;5(4):249–56. doi: 10.3109/02713688609020050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lohmann W, Schmehl W, Strobel J. Nuclear cataract: oxidative damage to the lens. Exp Eye Res. 1986;43(5):859–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(86)80015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Truscott RJ, Augusteyn RC. Oxidative changes in human lens proteins during senile nuclear cataract formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;492(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Truscott RJW. Age-related nuclear cataract--oxidation is the key. Experimental Eye Research. 2004;80(5):709–725. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dische Z, Zil HA. Studies on the oxidation of cysteine to cystine in lens proteins during cataract formation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1951;34:104–113. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(51)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spector A. Oxidative stress-induced cataract: mechanism of action. FASEB J. 1995;9(12):1173–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sweeney MH, Truscott RJ. An impediment to glutathione diffusion in older normal human lenses: a possible precondition for nuclear cataract. Exp Eye Res. 1998;67(5):587–95. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moffat BA, Pope JM. Anisotropic Water Transport in the Human Eye Lens Studied by Diffusion Tensor NMR Micro-imaging. Experimental Eye Research. 2002;74(6):677–687. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McGinty SJ, Truscott RJ. Presbyopia: The First Stage of Nuclear Cataract? Ophthalmic Res. 2006;38(3):137–148. doi: 10.1159/000090645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giblin FJ. Glutathione: a vital lens antioxidant. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2000;16(2):121–35. doi: 10.1089/jop.2000.16.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reddy V. Glutathione and its function in the lens--An overview. Exp Eye Res. 1990;50(6):771–778. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90127-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heiba IM, et al. Genetic etiology of nuclear cataract: evidence for a major gene. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47(8):1208–14. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klein B, Klein R, Moss S. Correlates of lens thickness: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39(8):1507–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Lens thickness and five-year cumulative incidence of cataracts: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7(4):243–8. doi: 10.1076/opep.7.4.243.4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heys KR, Cram SL, Truscott RJ. Massive increase in the stiffness of the human lens nucleus with age: the basis for presbyopia? Mol Vis. 2004;10:956–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weeber HA, et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of human lenses. Experimental Eye Research. 2005;80(3):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bettelheim FA, et al. Topographic correspondence between total and non-freezable water content and the appearance of cataract in human lenses. Curr Eye Res. 1986;5(12):925–32. doi: 10.3109/02713688608995173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Horwitz J. The function of alpha-crystallin in vision. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11(1):53–60. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lampi KJ, et al. Lens Proteomics: Analysis of Rat Crystallin Sequences and Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis Map. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43(1):216–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garland DL, et al. The nucleus of the human lens: demonstration of a highly characteristic protein pattern by two-dimensional electrophoresis and introduction of a new method of lens dissection. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62(3):285–91. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim YH, et al. Deamidation, but not truncation, decreases the urea stability of a lens structural protein, betaB1-crystallin. Biochemistry. 2002;41(47):14076–84. doi: 10.1021/bi026288h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chylack LT, Jr., et al. The Longitudinal Study of Cataract Study Group The Lens Opacities Classification System III. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(6):831–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060119035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jacques PF, et al. Weight status, abdominal adiposity, diabetes, and early age-related lens opacities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(3):400–405. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nirmalan PK, et al. Lens Opacities in a Rural Population of Southern India: The Aravind Comprehensive Eye Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44(11):4639–4643. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]