Abstract

Study Objectives:

Inadequate sleep and sleep disordered breathing (SDB) can impair learning skills. Questionnaires used to evaluate sleepiness in adults are usually inadequate for adolescents. We conducted a study to evaluate the performance of a Spanish version of the Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS) and to assess the impact of sleepiness and SDB on academic performance.

Design:

A cross-sectional survey of students from 7 schools in 4 cities of Argentina.

Measurements:

A questionnaire with a Spanish version of the PDSS was used. Questions on the occurrence of snoring and witnessed apneas were answered by the parents. Mathematics and language grades were used as indicators of academic performance.

Participants:

The sample included 2,884 students (50% males; age: 13.3 ± 1.5 years)

Results:

Response rate was 85%; 678 cases were excluded due to missing data. Half the students slept <9 h per night on weekdays. The mean PDSS value was 15.74 ± 5.93. Parental reporting of snoring occurred in 511 subjects (23%); snoring was occasional in 14% and frequent in 9%. Apneas were witnessed in 237 cases (11%), being frequent in 4% and occasional in 7%. Frequent snorers had higher mean PDSS scores than occasional or nonsnorers (18 ± 5, 15.7 ± 6 and 15.5 ± 6, respectively; P < 0.001). Reported snoring or apneas and the PDSS were significant univariate predictors of failure and remained significant in multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, specific school attended, and sleep habits.

Conclusions:

Insufficient hours of sleep were prevalent in this population. The Spanish version of the PDSS was a reliable tool in middle–school-aged children. Reports of snoring or witnessed apneas and daytime sleepiness as measured by PDSS were independent predictors of poor academic performance.

Citation:

Perez-Chada D; Perez-Lloret S; Videla AJ; Cardinali D; Bergna MA; Fernández-Acquier M; Larrateguy L; Zabert GE; Drake C. Sleep disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness are associated with poor academic performance in teenagers. A study using the pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS). SLEEP 2007;30(12):1698-1703.

Keywords: Sleepiness, pediatric daytime sleepiness scale, snoring, school outcome

INTRODUCTION

SEVERAL REPORTS SUGGESTS THAT ADOLESCENTS NEED MORE THAN 8 HOURS OF SLEEP PER NIGHT.1,2 HOWEVER, ADOLESCENTS OBTAIN LESS SLEEP THAN required. Some studies have shown that social activities and other behavioral patterns often shape adolescents' lifestyles toward predominantly nighttime behavior, while school schedules require them to be fully awake early in the morning. This interaction leads to reduced weekday sleep time and a persistent sleep debt. In a nationwide study in New Zealand, 21% of respondents felt they were not getting enough sleep.3

Reduction of nighttime sleep due to reduced or altered sleep schedules has been associated with excessive sleepiness and impaired school performance.4–6 For example, it is known that during adolescence, circadian phase delays are often out of phase with academic schedules producing an increased risk for sleepiness, reduced academic performance, and other significant morbidity. Physiological studies have also shown that adequate sleep may be important for the consolidation of memory which could have important implications for school success in adolescence.7,8 Wagner et al reported that a night of adequate sleep after being exposed to complex mathematical problems more than doubles the likelihood that the student will come up with a novel solution to the problems posed in class, compared with students with reduced sleep.9 In poor sleepers, the risk of failing one or more years at school is double that of normal controls.10 Similarly, in a study on sleep patterns and daytime functioning in 3,000 children, students with lower grades reported later bedtimes on school nights and increased weekend delays of sleep onset.11 Thus, there is increasing evidence that sleep loss and resulting excessive sleepiness due to reduced time in bed, poor sleep quality, or variable sleep schedules is associated with impaired academic performance.12,13 However, this association can potentially be bidirectional as poor academic performance may adversely affect sleep through concomitant stress or other mechanisms.

In addition to insufficient sleep, sleep disordered breathing (SDB) ranging from primary snoring to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, affects 10% to 25% of children between 3 and 12 years and may also contribute to poor academic performance.12,14–18 For example, SDB is associated with behavioral dysfunctions including aggression, impulsiveness and decreased attention.19–21 Additionally, children with SDB display lower IQ scores and lower scores on tests of memory and other executive functions.22 Both reduced sleep and frequent oxygen desaturations likely contribute to these negative outcomes.23

Given the high prevalence and important consequences of sleep loss and sleep disorders in adolescents, there is a clear need for readily available and sensitive measures of sleepiness for use with adolescents. Specifically, the ability to easily assess the relative degree of sleepiness in this age group may improve the identification of at-risk individuals and help track treatment progress over time. In adolescent research settings, subjective measure of sleepiness may complement objective methods and can provide valuable information when time consuming objective assessment may not be feasible, However, questionnaires used to evaluate excessive sleepiness associated with sleep disorders and insufficient sleep in adults may be inadequate for younger populations.

Recently, a validated measure for sleepiness in children was introduced: the Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS). Using this scale, daytime sleepiness was found to be related to lower school grades and other negative school-related outcomes.13 The present study was conducted to evaluate sleep habits and the value of the PDSS in a Spanish-speaking population of different cities in Argentina. To our knowledge no previous studies have tested foreign languages versions of this scale, and there were no studies exploring SDB and its impact on sleepiness as measured by the PDSS. We set out to investigate if self-reported sleepiness as measured as the PDSS is related to academic performance. The association between SDB and academic performance was also examined.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sample Population

The survey was conducted between May and November of 2004. Seven schools from four cities in Argentina participated in the study. This comprised a sample of adolescents from urban areas in Argentina predominantly between 10 and 15 years old. All the schools had similar socioeconomic status, representing a middle class background. We enrolled males and females students in their last grades of primary school and first 2 years of secondary school (between 9 and 17 years old).

Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Austral University. A questionnaire including the PDSS (see below) was administered to all participants in each of the seven schools. The questionnaire was presented to the students in a classroom setting after consent had been obtained from the parents and the school authorities. The students were free to answer the questionnaire or not at their own discretion. Every child participating in the survey was provided with a questionnaire to be completed by their parents. With parental consent, the school provided actual grades for language and mathematics achieved by each student for the current trimester. Academic failure was defined as a grade below 70% (7/10), which is considered insufficient for promotion to the next grade level.

Measures

The PDSS is an 8-item questionnaire developed to measure excessive sleepiness in younger school age populations,13 which was translated into Spanish and tested for comprehension (Appendix). Scores ranged from 0 to 32. Mean score values in the original study were 15.3 ± 6.2. Higher scores indicate greater sleepiness.

Sleep hours during the week and weekend were evaluated using Likert-scale specific questions (response options: >10 h, 8–10 h, 6–8 h, 4–6 h and <4 h). Nap time during the week and weekend was also assessed (response options: no nap, 15–30 min, 30–45 min, 45–60 min, and >60 min).

The parental questionnaire included questions on the presence and frequency of snoring and witnessed apneas in the child. Snoring was ascertained by the questions “Does your children snore?” (Yes, no or don't know), and “If yes, how many times per week?” One or two times per week, three to four, five to six, and every night were the possible answers. Apneas were evaluated through the questions “Have you ever seen that breathing during sleep is irregular or interrupted?” (Yes, no or don't know). The same categories used for snoring were used for apnea frequency. Reported snoring or apneas more than three nights per week were considered as frequent.24 Gender, height and weight data were also collected. Overweight and obesity were defined according to the international normality ranges proposed by Cole for Body Mass Index (BMI).25

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented using frequencies, means and medians according to the distribution of the data. χ2 and ANOVA tests were used for univariate comparisons and logistic regression modeling for multivariate analysis. Cronbach's α was used for correlation between items of the PDSS scale. For the outcome of failure in mathematics and literature, all other collected variables were treated as predictors in logistic regression analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13 software (Chicago, Il, USA)

RESULTS

The target population comprised 3,393 students. Of these, 509 (15%) were absent from school on the day of the survey and 2,884 students agreed to participate in the study. In 674 cases (23%) information on key variables was missing (including 281 cases of parents who answered “don't know” in the question about apneas) and they were excluded from analysis. The final study sample included 2,210 subjects. Population features are shown in Table 1. Excluded subjects were older, had higher BMIs and had poorer mathematics grades (P < 0.05 for all). On the contrary, no differences were found regarding to the PDSS, academic failure rates, week and weekend sleep hours and snoring and witnessed apnea rates.

Table 1.

Study Population

| Demographics | |

| Age (mean and SD, range) | 13.3 ± 1.4 (9–17) |

| Males (n, %) | 1,105 (50) |

| Body mass index (mean, SD, range) | 19.8 ± 3.2 (11.08–35.15) |

| Overweight (n, %) | 327 (15) |

| Obese (n, %) | 58 (3) |

| Sleep disordered breathing | |

| Frequent snoring (n, %) | 210 (9) |

| Occasional snoring (n, %) | 301 (14) |

| Occasional apneas (n, %) | 150 (7) |

| Frequent apneas (n, %) | 87 (4) |

| Outcomes | |

| Math grade (mean, SD) | 6.7 ± 1.6 |

| Language grade (mean, SD) | 6.9 ± 1.4 |

| Math failure (n, %) | 882 (40) |

| Language failure (n, %) | 745 (34) |

| Sleep and sleepiness data | |

| PDSS (mean, SD) | 15.74 ± 5.93 |

| Naps | |

| Week (n, %) | 672 (30) |

| Weekend (n, %) | 328 (15) |

Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) and inter-item correlation of the PDSS scale in the full sample were 0.74 and 0.26, respectively. When the samples from each school were evaluated individually, Cronbach's α values ranged from 0.72 to 0.81. Values for the original publication were 0.813

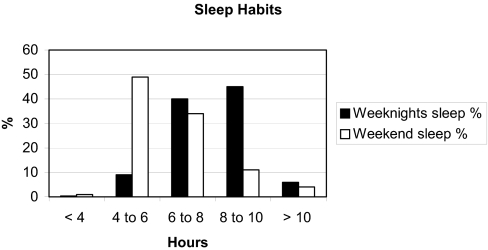

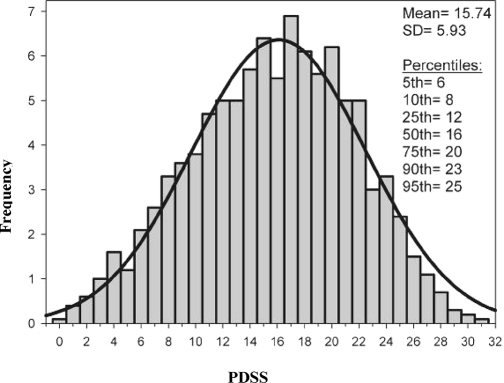

Information on sleep habits is shown in Figure 1. Forty-nine percent of subjects reported sleeping less than 8 h on weeknights while 83% slept less than 8 h per night during weekends. Snoring was reported by 511 subjects (23%). Witnessed apneas were reported in 237 cases (11%) (Table 1). Figure 2 depicts the distribution of PDSS values.

Figure 1.

Sleep hours during weekdays and weekends, excluding daytime naps. (*)Excludes weekend and weeknight naps. Pearson's χ2 P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Relative frequency histogram of PDSS. The estimated Gaussian distribution curve has been superimposed.

Mean PDSS scores were higher for snorers than nonsnorers (16.6 ± 5.9 vs.15.5 ± 5.9; P< 0.001) indicating more sleepiness in this group. PDSS was also higher in older subjects (9–12 y: 14.7±6.1, 12–15 y: 15.7±5.9 and 12–17 y: 16.6±5.7, P<0.003, Table 2). On the contrary, no significant differences were found regarding the severity of snoring or witnessed apneas (Table 2)

Table 2.

Subject Features by Snoring Frequency

| No Snoring (n=1699) | Occasional (n=301) | Frequent (n=210) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (mean, SD) | 19.7 ± 3.1 | 20.0 ± 3.3 | 20.8 ± 3.4 | P<0.001 |

| Normal (n, %) | 1,430 (84) | 237 (79) | 157 (75) | P<0.001 |

| Overweight (n, %) | 234 (14) | 54 (18) | 39 (19) | P<0.001 |

| Obese (n, %) | 34 (2) | 10 (3) | 14 (7) | P<0.001 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 13.3 ± 1.4 | NS |

| PDSS (mean, SD) | 15.5 ± 5.9 | 15.7 ± 5.9 | 18.0 ± 5.4 | P<0.001 |

| Sex (males n, %) | 814 (48) | 171 (57) | 120 (57) | NS |

| Mathematics grade (mean, SD) | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | P<0.001 |

| Mathematics failure (n, %) | 646 (38) | 131 (43) | 105 (50) | P<0.001 |

| Language grade (mean, SD) | 7.0 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | P<0.001 |

| Language failure (n, %) | 535 (31) | 120 (40) | 90 (43) | P<0.001 |

| Week nap (n, %) | 498 (29) | 98 (32) | 76 (36) | NS |

| Weekend nap (n, %) | 232 (14) | 51 (17) | 45 (21) | NS |

Table 3.

Subjects Characteristics by Age-Groups

| 9–11 years (n=280) | 12–14 years (n=1491) | 15–18 years (n=435) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (mean, SD) | 18.6 ± 3.2 | 19.8 ± 3.2 | 20.8 ± 2.9 | P<0.001 |

| Normal (n, %) | 214 (77) | 1,233 (83) | 377 (86) | P<0.01 |

| Overweight (n, %) | 54 (19) | 218 (15) | 55 (13) | P<0.01 |

| Obese (n, %) | 12 (4) | 40 (2) | 6 (1) | P<0.01 |

| BMI z-score (mean, SD) | 0.51 ± 1.24 | 0.32 ± 1.07 | 0.24 ± 0.91 | P<0.003 |

| PDSS (mean, SD) | 14.7 ± 6.1 | 15.7 ± 5.9 | 16.6 ± 5.7 | P<0.001 |

| Sex (males n, %) | 154 (55) | 749 (50) | 202 (46) | NS |

| Mathematics grade (mean, SD) | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 1.8 | P<0.001 |

| Mathematics failure (n, %) | 86 (31) | 560 (38) | 236 (54) | P<0.001 |

| Language grade (mean, SD) | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 6.8 ± 1.5 | P<0.001 |

| Language failure (n, %) | 67 (24) | 510 (34) | 168 (39) | P<0.001 |

| Snoring frequency | NS | |||

| No snoring (n, %) | 207 (74) | 1,157 (78) | 335 (76) | NS |

| Occasional (n, %) | 46 (16) | 195 (13) | 60 (14) | NS |

| Frequently (n, %) | 28 (10) | 139 (9) | 43 (10) | NS |

| Witnessed apneas frequency | ||||

| No apneas (n, %) | 250 (89) | 1,329 (89) | 394 (90) | NS |

| Occasional (n, %) | 19 (7) | 105 (7) | 26 (6) | NS |

| Frequently (n, %) | 12 (4) | 57 (4) | 18 (4) | NS |

| Week nap (n, %) | 35 (12) | 439 (30) | 198 (45) | P<0.001 |

| Weekend nap (n, %) | 55 (20) | 199 (13) | 74 (17) | P<0.01 |

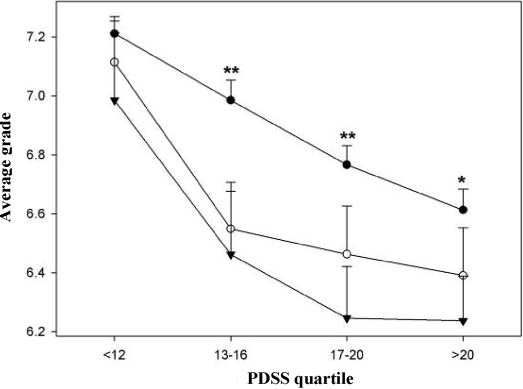

BMI, BMI z-score and frequency of overweight and obesity were significantly different among snoring categories. Snorers had lower mean grades in mathematics (6.4 ± 1.6 vs. 6.8 ± 1.6, P <0.001) and language (6.7 ± 1.5 vs. 7.0 ± 1.4; P< 0.001). PDSS, mathematics and language grades, as well as the proportion of failures of frequent snorers were also significantly different from occasional snorers (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average mathematic and literature grades (means ± SD) according to the PDSS in non-snorers (•), occasional snorers (○) and frequent snorers (▾). Two-way ANOVA found significant main effects of the PDSS (P< 0.001) and snoring (P<0.001). For each quartile, average grade was compared between snorers, occasional and frequent snorers (One-way ANOVA, * P<0.05, ** P<0.01).

To explore the relationship between sleepiness and academic results we segregated the sample into quartiles of PDSS values (1st quartile: <12, n = 661; 2nd quartile: 13–16, n = 500, 3rd quartile: 17–20, n = 548 and 4th quartile: ≥ 21, n = 501). Average grades for mathematics and language showed significant differences among groups (nonsnorers, occasional and frequent snorers) in each quartile, especially at the highest ones (Figure 3).

In the univariate analyses, the presence of snoring and apneas was associated with failure in mathematics and language. PDSS was associated with academic failure in both mathematics and language, i.e. each point of increase in the scale was associated with a 5% increase in risk for failure. (Table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression Models of Failure in Mathematics and Literature

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted Model OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | ||

| Snoring | 1.39 (1.14–1.70) | 1.33 (1.08–1.65) |

| Apneas | 1.63 (1.24–2.14) | 1.42 (1.06–1.89) |

| PDSS | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) |

| Language | ||

| Snoring | 1.51 (1.24–1.86) | 1.38 (1.11–1.72) |

| Apneas | 1.66 (1.26–2.12) | 1.48 (1.09–1.99) |

| PDSS | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) |

Model includes PDSS or “snoring or apnea variables” as criterion variables and BMI z- score, age, gender, attending a specific school, and sleep hours during the week as predictors. OR = odds ratio. The significance of the PDSS score here indicates that for each point increase in sleepiness on the PDSS there was a 5% increase in the risk for academic failure in the respective course area.

The association between snoring and apneas with academic failure in mathematics and language remained significant regardless of the specific school considered, PDSS, BMI z-score, age, gender, and sleep hours during the week. The association between PDSS values and academic failure in mathematics and language remained significant after adjusting for the presence of snoring or apneas as well as BMI z- score age, gender, attending a specific school, and sleep hours on weekdays (Table 4). Weekend sleep was excluded from the model because it showed no statistical significance in univariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were: adolescents suffered from insufficient sleep; the Spanish version of the PDSS scale was a reliable tool in middle–school-aged children; and report of snoring or witnessed apneas, on one hand, and daytime sleepiness on the other, were independent predictors of poor academic performance.

Lack of adequate sleep time was prevalent in our results as found in other studies2. In fact, 49% and 83% of the sample reported getting less than 8 hours of sleep per night on weekdays and weekends, respectively. Insufficent sleep, especially on weekends was common in this population. Thus a substantial portion of the relationship between sleepiness and academic performance in this sample is likely to be due to self-imposed lack of sleep. Studies on U.S. adolescents show that sleep debt comes from loss of sleep on weeknights, with compensation on weekends.2,4,11,19 In our sample, sleep debt was mainly produced on the weekends, probably reflecting a more active nighttime lifestyle in this population and possibly a lower priority for sleep. In this setting, sleep debt is likely to be produced by leisure activities, and the direction of causality is likely unidirectional. Whether weekday insufficient sleep is also caused by leisure activities remains to be further examined.

The Spanish version of the PDSS scale was comparable to the original version, as the mean values were similar to those in the original work. Further, its internal consistency was also similar to the value initially reported.13 No reference values have been described for this scale, and it has not been previously applied to a sleep disordered population, so these results can be considered a first step in that direction. However, children with higher PDSS scores had lower average mathematics and language grades, suggesting sensitivity to an important real-world outcome. Indeed, the PDSS was a powerful predictor of failure, as each point of increase of the scale was associated with a 5% increase of risk for failure. This association remained significant after adjusting for potential confounding factors such as age, sex, school, and BMI. Results also remained significant after adjusting for the amount of sleep during weekdays.

In the present study, a small number (3%) of adolescents were obese, while 15% were overweight. These results are similar to the 4.6% obesity prevalence reported in previous studies among Latin American children26 and are also in agreement with a survey conducted in Argentine adolescents, which found that 10.9% of students were overweight and 2.2% were obese.27 We found that parents reported hearing their child snore in 23% of cases and witnessed apneas in 10%, a finding in line with previous published observations.14 In a recent community-based sample Johnson et al found that more than 20% of adolescents snored at least a few nights per month, and 6% snored every night or nearly every night. Apnea-like symptoms affected 2.5% to 6.1% of the sample.28 Although reporting of apneas was slightly higher in our study than other studies of younger populations, the present results are consistent with the 10%-23% of prevalence of an apnea/hypopnea index >5 reported in young adults.24 It must be noted that there are no epidemiological studies of the prevalence of apnea using objective measurements in adolescents.

Though frequent snoring was associated with poor academic performance, the presence of witnessed apneas had the highest correlation with academic failure, similar to other studies.29,30

Our study has several limitations. Our design does not allow temporal inference, thus limiting discussions of causality. In any study dealing with prevalence data, selection bias is also a concern. However the demographics results are similar to previous studies.27 The study was done in urban schools of middle class socioeconomic status. Sleep habits can be different in a rural setting as farm-related chores early in the morning can affect bedtime schedules or in other settings with markedly different socioeconomic status. Recall bias can affect reports of snoring and apnea by parents. However, it is interesting to note that even assuming that most of our subjects slept in a different room from their parents, the proportion of reported snoring and apneas was close to the findings of other studies.10,13,31 Other possible limitations include the broad age range of the sample, lack of data on pubertal status, recall bias on adolescent perception of sleep time, and the potential effect of sample size that might lead to spurious results. The PDSS scale has not yet been validated using objective methods (e.g., the multiple sleep latency test) and we were not able to obtain objective evaluation of sleep in our sample. School outcomes were limited to grades in language and mathematics which can be affected by a number of factors. Despite this however, results remained significant even after controlling for potential confounds. Cognitive performance was not evaluated using standardized tests, as it was not feasible for a large multicenter sample. Indeed, grades used as proxies for cognitive function should eventually be complemented by cognitive testing. Nevertheless, our results suggest that academic achievements are negatively affected by sleepiness and SDB.

Finally, a possible unmeasured confounding factor is the possibility that there could be more students with poor economic background and /or low cognitive capabilities (unrelated to sleep) among those students with unhealthy sleeping habits than in the groups with regular sleeping habits. IQ evaluations are difficult to run in large samples and socioeconomic data was not available, so we were unable to assess this possibility.

While students in other populations attempt to catch up on sleep debt during weekends, youngsters in our sample seemed to aggravate their sleep debt by further reducing sleep time on weekends. Thus, this population appears to be at a strikingly high risk for chronic sleep debt. Further studies should be carried out to identify the full impact of this in the Argentine population as well as other Latin American countries. This and other sleep problems need to be confronted through education and enhanced diagnosis of SDB as well as changing poor sleep habits among adolescents.

In summary, the Spanish PDSS showed similar internal consistency and relationship to academic performance as compared to the English original version. Children at high risk for SBD showed lower academic performance. Daytime sleepiness as measured by the PDSS was robustly and significantly associated with academic failure. Taking into account the ease of administration of this scale, the PDSS has a potential role as a clinical tool in the practitioner's office to evaluate sleepiness and predict academic failure. Parents' recall of snoring and apneas in their children can be easily collected during medical evaluation and used as an indicator of risk of disease and poor academic performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Marina Khoury for her statistical advice in the early phase of this study. We are indebted also to Drs. Enriqueta Prieto-Mazzucco and Martina Marchesotti, and to the medical students from Facultad de Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Austral who were involved in the field work. Finally, we thank all the teachers, students and parents who helped make this research possible.

APPENDIX

Spanish version of the Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Score

Possible answers: Siempre, frecuentemente, a veces, casi nunca, nunca

¿Con que frecuencia te quedás dormido/a o te da sueño durante las horas de clase?

¿Con que frecuencia te quedás dormido/a o te da sueño mientras haces la tarea?

¿Estas atento/a o alerta la mayor parte del día?

¿Con que frecuencia te sentís cansado y de mal humor durante el día?

¿Con que frecuencia te cuesta levantarte de la cama a la mañana?

¿Con que frecuencia te volvés a quedar dormido después de que te despertaron a la mañana?

¿Con que frecuencia necesitás que alguien te despierte por la mañana?

¿Con que frecuencia sentís que necesitás dormir más tiempo?

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carskadon MA, Harvey K, Duke P, Anders TF, Litt IF, Dement WC. Pubertal changes in daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 1980;2:453–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/2.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carskadon MA. Patterns of sleep and sleepiness in adolescents. Pediatrician. 1990;17:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorofaeff TF, Denny S. Sleep and adolescence. Do New Zealand teenagers get enough? J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:515–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carskadon MA, Harvey K, Dement WC. Sleep loss in young adolescents. Sleep. 1981;4:299–312. doi: 10.1093/sleep/4.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randazzo AC, Muehlbach MJ, Schweitzer PK, Walsh JK. Cognitive function following acute sleep restriction in children ages 10–14. Sleep. 1998;21:861–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson ES, Powles AC, Thabane L, et al. “Sleepiness” is serious in adolescence: two surveys of 3235 Canadian students. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:276–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature. 2005;437:1272–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner U, Gais S, Haider H, Verleger R, Born J. Sleep inspires insight. Nature. 2004;427:352–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn A, Van de Merckt C, Rebuffat E, et al. Sleep problems in healthy preadolescents. Pediatrics. 1989;84:542–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake C, Nickel C, Burduvali E, Roth T, Jefferson C, Pietro B. The pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS): sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep. 2003;26:455–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell RB, Pereira KD, Friedman NR. Sleep-disordered breathing in children: survey of current practice. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:956–8. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000216413.22408.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samkoff JS, Jacques CH. A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallone G, Seifer R, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. How well do school-aged children comply with imposed sleep schedules at home? Sleep. 2002;25:739–45. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallone G, Owens JA, Deane J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:287–306. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Understanding adolescents' sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:491–506. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(03)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens J, Opipari L, Nobile C, Spirito A. Sleep and daytime behavior in children with obstructive sleep apnea and behavioral sleep disorders. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1178–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Archbold KH, Pituch KJ, Panahi P, Chervin RD. Symptoms of sleep disturbances among children at two general pediatric clinics. J Pediatr. 2002;140:97–102. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.119990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein NA, Fatima M, Campbell TF, Rosenfeld RM. Child behavior and quality of life before and after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:770–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb DJ, Chase C, Vezina RM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms are associated with poorer cognitive function in 5-year-old children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:458–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. Br Med J. 2000;320:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amigo H. [Obesity in Latin American children: situation, diagnostic criteria and challenges] Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19(Suppl 1):S163–70. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000700017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez CA, Ibanez JO, Paterno CA, et al. [Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents of Corrients city. Relationship with cardiovascular risk factors] Medicina (B Aires) 2001;61:308–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson EO, Roth T. An epidemiologic study of sleep-disordered breathing symptoms among adolescents. Sleep. 2006;29:1135–42. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owens J, Spirito A, Marcotte A, McGuinn M, Berkelhammer L. Neuropsychological and behavioral correlates of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: a preliminary study. Sleep Breath. 2000;4:67–78. doi: 10.1007/BF03045026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin JL, Kaemingk KL, Fregosi RF, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with sleep-disordered breathing in Caucasian and Hispanic children—the Tucson Children's Assessment of Sleep Apnea study (TuCASA) Sleep. 2003;26:587–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eliasson A, King J, Gould B. Association of sleep and academic performance. Sleep Breath. 2002;6:45–8. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]